Calculation of Electric Field of the Photon

Since the photon is an extremely tiny electric dipole. According to electromagnetic theory, the electric field strength

of the electric dipole at the distance of

R is [

7]

In Eq. (2),

is unit distance vector along

R direction.

is electric constant.

is the electric dipole moment of the photon, and

where

is the absolute value of the electric charge of the positron or electron, and

is the unit distance vector along distance

r between the positron and electron.

direction is from electron to positron.

From Eq. (2), we know that when the direction of

changes, the electric field strength

changes too. When the direction of

is the same as or opposite to the direction of

, the electric field strength

becomes

or

The

in Eq. (4) is positive, which expresses a repulsive force away from the dipole to a positive point charge. The

in Eq. (5) is negative, which expresses an attractive force towards the dipole to a positive point charge. And when the direction

of the dipole moment is perpendicular to the direction of

, the electric field strength

becomes

The in Eq. (6) is negative, but it is a deflective force, because the direction of is perpendicular to the direction.

From the Eqs. (4), (5) and (6), we can see that the electric filed strength of the electric dipole is anisotropic. When the direction of is the same as or opposite to the direction of , the electric field strength becomes the strongest (positive maximum) and weakest (minus maximum).

Using Eqs. (4) or (5), the repulsive or attractive electric field strength of the photon can be calculated. As the absolute values of the repulsive and attractive electric field strengths of the photon are the same, only the attractive electric field strength of the photon is calculated below. According to Eq. (5), the attractive electric field strength of the photon depends on the electric charge

and the photon's dipole length

. Thus, it is necessary to know the value of

r. Some researchers have estimated that the photon size is about

(

) [

8]. Here, the author also attempts to provide both an upper bound and a lower bound for the size of the photon.

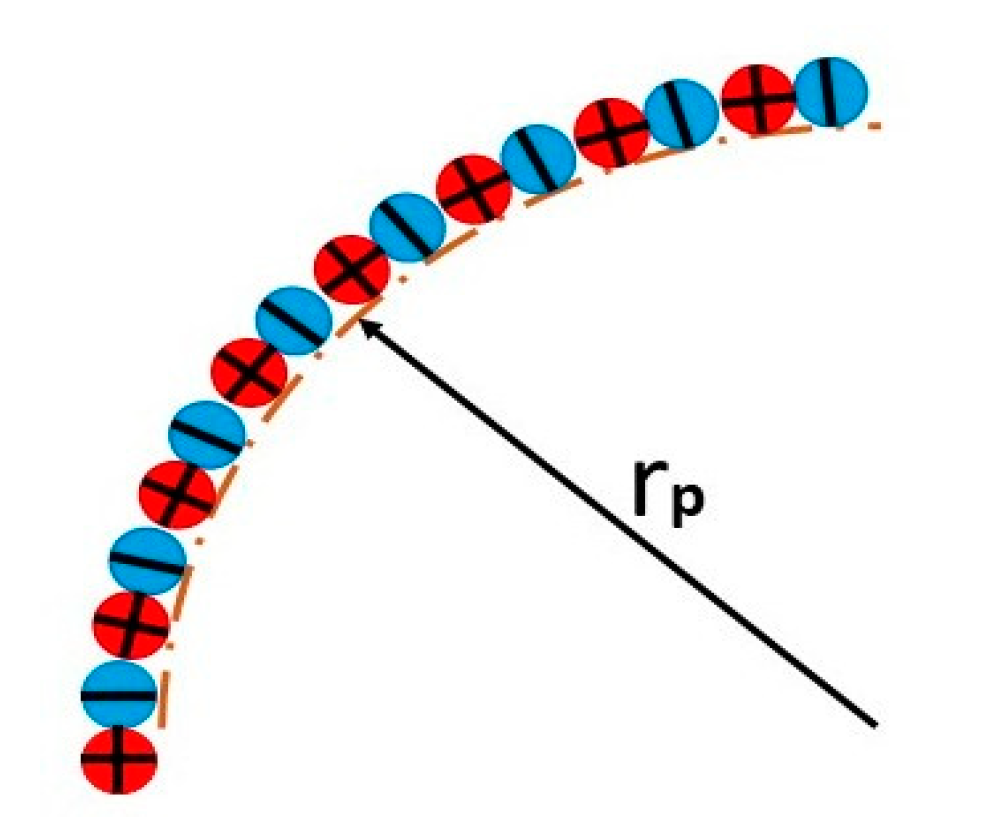

As mentioned above, it has been deduced that atoms are made of photons; that is, protons and neutrons are composed of photons (more detailed explanations will be given below). Thus, there are several ways to roughly estimate the number of photons contained in one proton or neutron.

First, the (point-like charge) diameter of the proton is

(

) [

9,

10], and the proton mass is about 1836 times the mass of an electron [

11]. Considering that the positron and electron have approximately the same mass, thus, it is reasonable to suppose that there are no more than 1,000 photons contained in a proton. If the photons are arranged one by one in three dimensions in the proton, the upper bound of the photon diameter should be no more than

(

) since the proton’s shape should be more like a sphere, not a cube.

Next, when all photons contained in a proton are released out completely, perhaps, the number of the released photons might be calculated from Einstein mass-energy conservation law

and Planck's formula of photon’s energy

where

is Planck constant,

is angular frequency of the photon.

Because the mass

of the proton is

[

12], thus, choosing the values of

from radio wave to Gamma-ray, the number of the photons contained in a proton may be calculated via Eqs. (7) and (8). The calculation results are shown in

Table 1. In

Table 1, the values of

are converted into the corresponding values of wavelength λ according to

(where

C is light speed in vacuum). In

Table 1, the showing photon wavelengths are chosen at the different frequency band upper boundaries.

The frequencies of the photons contained in the proton and neutron should be very high and within the x-ray and gamma-ray bands, because the photons released from the nuclei in nuclear fission and fusion are mainly gamma rays. Thus, according to

Table 1, the number of photons contained in a proton should be no more than 10,000. Also, supposing that the photons are arranged one by one in three dimensions in the proton, the upper bound of the photon diameter should be no more than

, where 2.1544 is the cube root of 10. Thus, the upper bound of the photon diameter should be no more than

.

In addition, as mentioned above, both the gravitational mass and the inertial mass of an object are quantitative expressions of the received external electric force strengths on that object. Thus, the real mass of the photon may be less than the estimate above; that is, the real photon mass may be less than 2/1836 of the proton mass. Also, the real equivalent energy of the photon contained in the proton may be less than that of the photons in the x-ray or gamma-ray band. Thus, the number of photons contained in a proton may be close to

or more (see

Table 1). Thus, the lower bound of the photon diameter may be less than

.

The upper bound of the electron diameter has been estimated as about

[

13]. Considering that there are relatively large deviations in the measurements or calculations of electron and photon sizes, the dipole moment length of the photon should be taken with a wide range in the calculations for possible deviations. Thus, the moment length of the photon dipole is taken from

to

. Then, by substituting the electron electric charge of

coulombs into the Eq. (5), the attractive electric field strength of the photon dipole is calculated.

Table 2 shows the calculation results. In

Table 2,

is the distance from the photon center.

is the length of the photon dipole moment. The unit of the electric field strength is V/m (Volt per meter).

From

Table 2, we can see that in the very close vicinity of the photon, the attractive electric field strength of the photon is extremely large. For example, at the site with the distance of

from the photon center, the electric field strength is from

V/m to

V/m for photons with dipole moment lengths of

to

. Such large electric field can bind multiple photons tightly within a small range certainly in the way that the negative end of each photon attracts the positive end of a neighbor photon.

With the increase of the distance , the electric field strength of the photon drops extremely fast. For example, at the site with the distance of from the photon center, the electric field strength of the photon drops to from V/m to V/m for photons with dipole moment lengths of to . Therefore, to measure the electric field strength of the photon is very difficult. It is the reason that the photon is regarded as no electric field.

Because the neutron has approximately the same mass as the proton [

14], the number of the photons contained in a neutron is approximately the same as that in the proton.

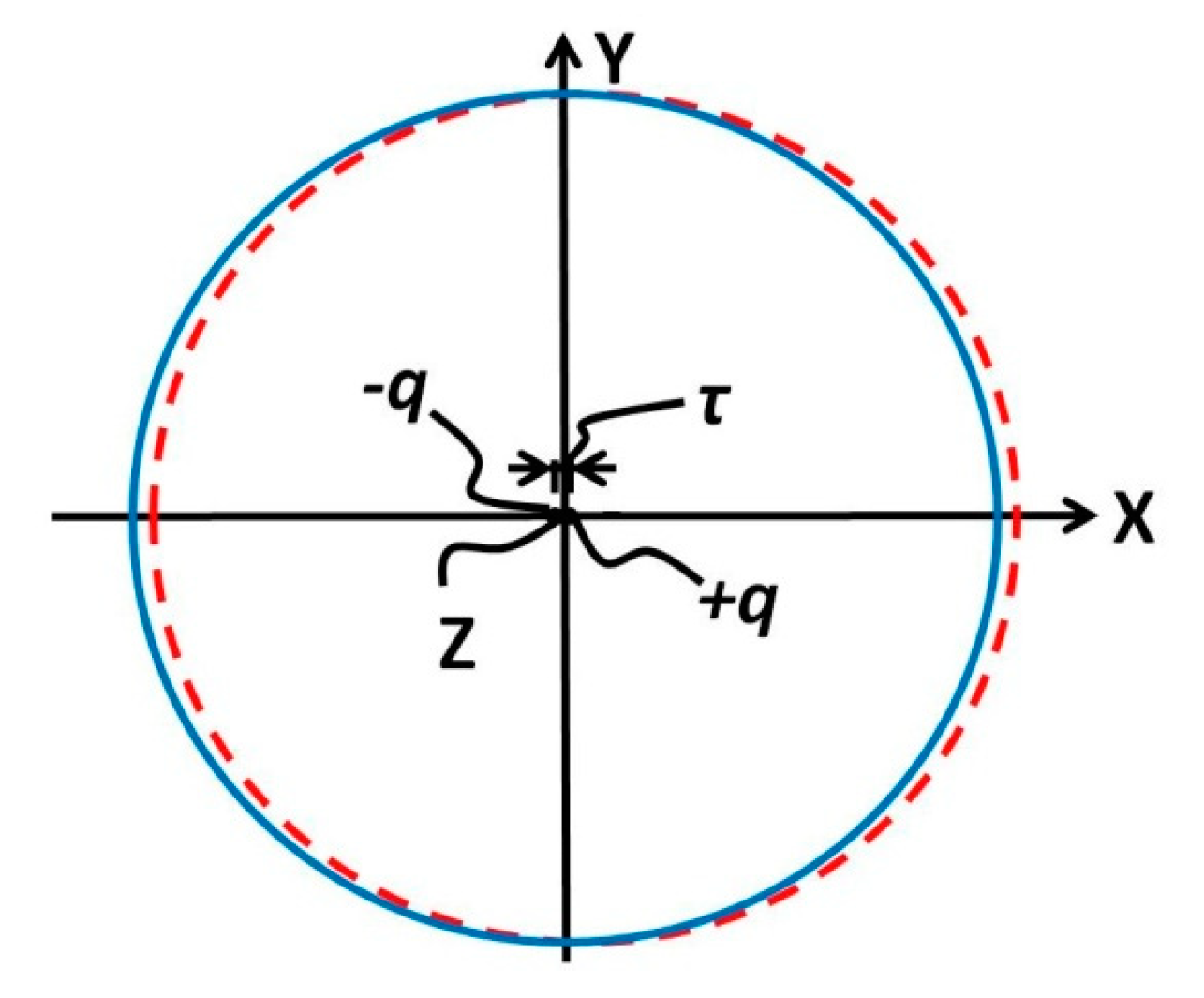

Causes of the Properties and Behaviors of the Light

Both the positron and electron have rotational angular momentums and magnetic moments. Thus, the electric fields of the positron and electron are rotational. When the positron and electron combine to form a photon, due to their magnetic interaction forces, their magnetic moment directions must be reversed. Because the positron and electron are as close as possible due to their strong electrical attractive forces, their magnetic moments are arranged in a parallel and side-by-side manner with opposite directions. This means the central axes of the rotational electrically positive and negative fields of the positron and electron are parallel to each other, and the electric fields of the positron and electron rotate synchronously in the same directions. Therefore, the photon is not only an extremely tiny electric dipole but also a rotational electric dipole.

When the photon moves in space, the angular momentums of the positron and electron must be conserved. Thus, the photon can only move forward along the direction that is perpendicular to the directions of the angular momentums of the positron and electron.

The photon is an extremely tiny electric dipole with both linear and rotational motions. Many such photons compose the light wave. This physical model can effectively explain various puzzles about the photon and light wave.

In the following, the causes of unique properties and peculiar behaviors of the light are explained in detail, separately. They include:

Light electromagnetic wave property,

Light frequency,

Light wavelength,

Light polarization,

Light coherent length,

Light wavelength redshift,

Cosmic microwave background radiation,

Light bending,

Wave-particle duality of the photon and other microscopic particles,

Photoelectric effect,

Compton effect,

Light pressure,

Difference between the light and electromagnetic wave and key for photosynthesis,

Truth of the light speed.

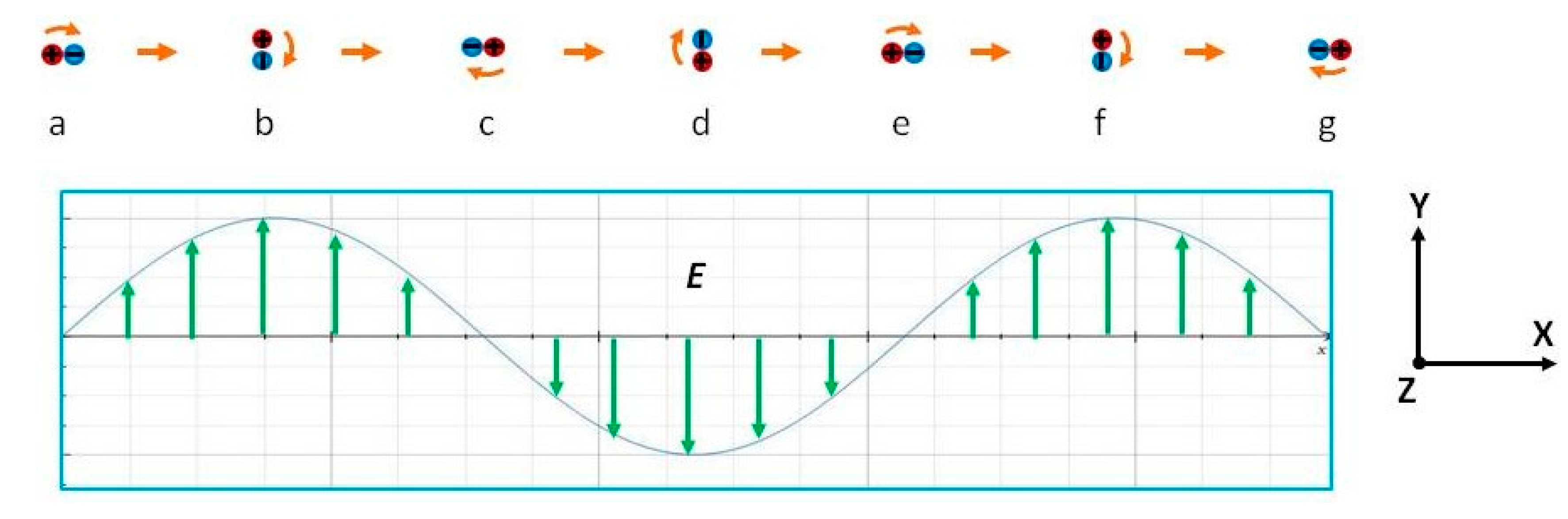

Suppose a photon is moving along the x-axis; this photon also rotates around its central axis, which is parallel to the z-axis. The top section of

Figure 3 shows photon movement in the x-direction with rotation in the xy-plane.

induced by the photon motion and rotation with a change rate of sine shape.

In

Figure 3, the photon is represented by an electric dipole consisting of a positron (small red circle) and an electron (small blue circle). When the photon goes to the spot a, the direction of the dipole moment is perpendicular to the y-axis, so the electric field

of the dipole is zero in the y-direction at the spot a. When the photon goes to the spot b, the direction of the dipole moment points to the positive y-axis, and so the electric field

of the dipole is positive and the maximum in the y-direction at the spot b. When the photon goes to the spot c, the direction of the dipole moment is perpendicular to the y-axis again, so the electric field

is zero again in the y-direction at the spot c. When the photon goes to spot d, the direction of the dipole moment points to the negative y-axis, and so the electric field

of the dipole is negative and the minus maximum in the y-direction at the spot c.

From the spot a to the spot b, the strength of the electric field increases from zero to the positive maximum gradually. Then, from the spot b to the spot c, the strength of the electric field decreases from the positive maximum to zero gradually. From the spot c to the spot d, the strength of the electric field decreases from zero to the minus maximum gradually. Then, from the spot d to the spot e, the strength of the electric field increases from the minus maximum to zero gradually.

When the photon moves forward continually from the spot e to the spots f and g, the changes of the electric field are the same as those happened in the paths from the spot a to the sports b and c, that is, the electric field of the photon will repeat previous changes. These periodical strength changes of the photon electric field in the y-direction will be repeated again and again with photon movement along the x-direction.

Of course, the change of the photon electric field in the x-direction is also periodically repetitive with photon motion and rotation along the x-direction. For example, when the photon is at the sport a, its electric field is negative maximum in the x-direction. When the photon is at the sport c, its electric field is the positive maximum in the x-direction. However, the change of its electric field in the x-direction is different from the change of its electric field in the y-direction. Because the photon moves along the x-axis, so in the positive x-direction, the photon negative electric field distribution at a previous sport (for example, at the sport a) will be cancelled by the photon positive electric field at a latter sport (for example, at the sport c). Please note, both of the sport a and the sport c are on the x-axis. Due to extremely tiny size and very fast rotational speed, the photon electric field in the x-direction is almost zero.

In addition, because the point charge centers of the positron and electron are always located on the xy-plane, there are no changes in the electric fields of the positron and electron in the z-direction.

When the photon moves with rotation along the x-direction, the changes in the photon's electric field in the y-direction can't be canceled. This is different from the changes in the photon's electric field in the x-direction. For example, at a previous moment, the photon produces a positive electric field in the y-direction at point b, and then, at a later moment, the photon produces a negative electric field in the y-direction at point d. Because points b and d are located at different positions on the x-axis, the positive electric field in the y-direction at point b can't be canceled by the negative electric field in the y-direction at point d.

Thus, the straight-line motion along the x-direction and the rotation in the xy-plane of the photon create the periodic vibration of its electric field

in the xy-plane, as shown in the bottom section of

Figure 3. This periodic vibration is caused by the electric field, so the light wave is the periodic vibration of the electric field strength. This periodic vibration is also caused by the rotation of the electric field, so the light wave is also the periodic vibration of the magnetic field strength in the xz-plane. Additionally, this periodic vibration is caused by the circular rotation of the photon's electromagnetic fields, so the photon electromagnetic field change rate curves have sine shapes.

- 2.

Origin of the Light Frequency

As shown in

Figure 3, the photon electric fields rotate continually, and the photon electric field strength in the y-direction repeats periodically. The change rate of the photon electric field over time determines the frequency of the photon or light wave. The origin of the light frequency is the rotational angular velocity of the photon.

There is a problem that needs further discussion. The angular momentum value of the photon's rotation should be related to the values of the positron and electron magnetic moments. The values of the positron and electron magnetic moments are quantized in observations; that is, they are discontinuously discrete. However, the light frequency distribution is continual.

The key to resolve this contradiction is that the photon actually has a zero net magnetic moment. Because the values of the positron and electron magnetic moments are equal but in opposite directions, the net magnetic moment of the photon is zero. Thus, as a microscopic particle, since the photon's net magnetic moment is zero, the quantized requirement for the magnetic moment is not applicable to the photon. In other words, the requirement for the values of the positron and electron magnetic moments to be discrete is removed, or the circumstances causing the positron and electron magnetic moment values to be discrete no longer exist.

The photon can rotate at any angular speed, meaning it can have any frequency. However, the photon frequency can't be too high or too low. The frequency can't be too high because the photon's rotational energy can't be infinite. The frequency can't be too low because the temperature of any substance in the universe can't be absolute zero.

- 3.

Origin of the Light Wavelength

Supposing the speed of the photon moving along the x-axis is

, and the photon frequency is

, the photon wavelength is

, then

In vacuum, the light speed becomes .

- 4.

Origin of the Light Polarization

As described above, the photon's electric field vibrates periodically only in a two-dimensional plane, such as the xy-plane shown in

Figure 3, and the electric field strength changes only in one direction, such as the y-direction. There are no changes in electric field strength in the other two directions, such as the x-direction and z-direction. Therefore, the photon's electric field is a linearly polarized electromagnetic field. Thus, the light wave is a polarized electromagnetic wave.

- 5.

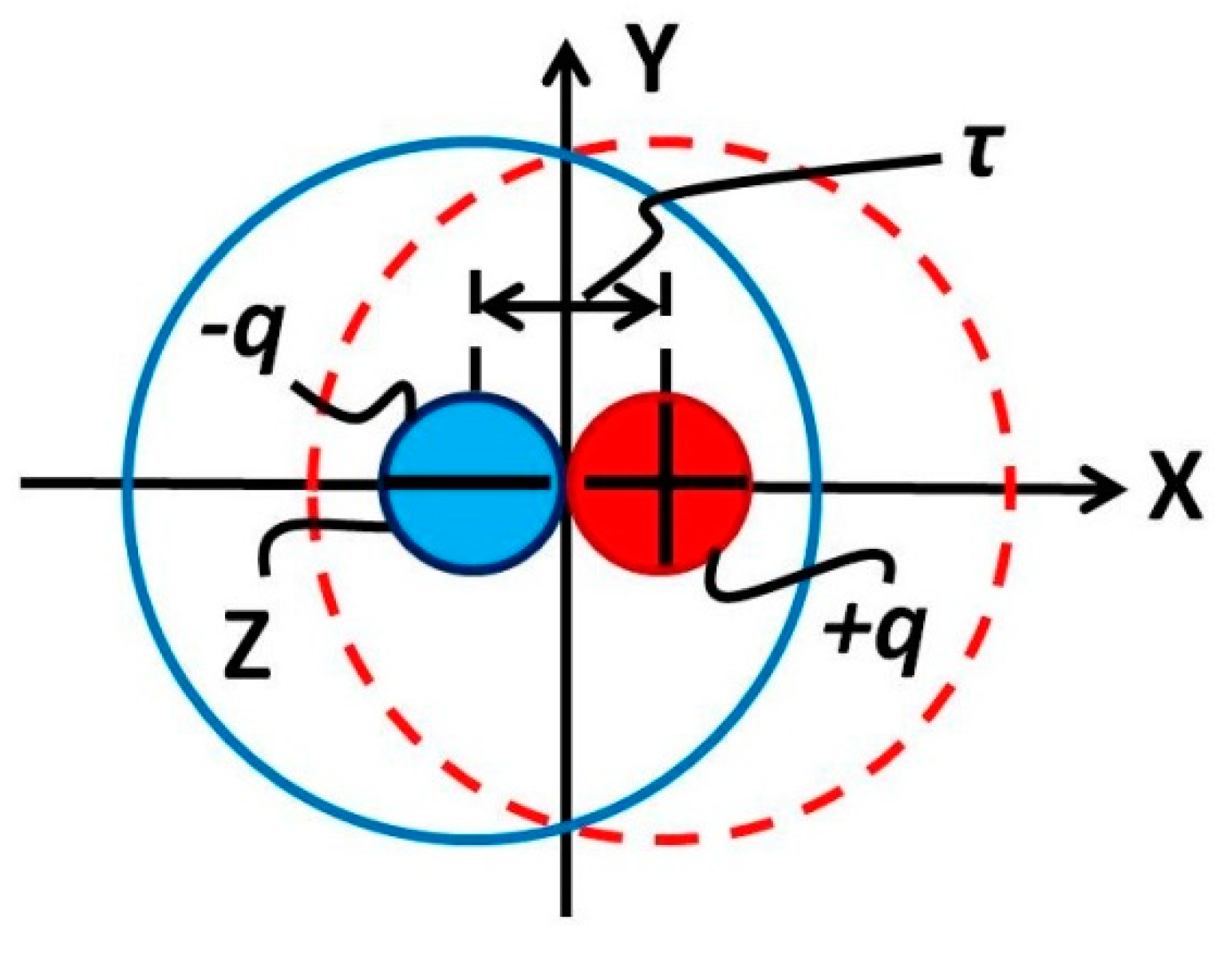

Origin of the Light Coherent Length

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the synthetic non-uniform electric field of the photon dipole has a very short effective interaction distance. Outside a very small disk-like spatial region, the strength of the non-uniform electric field of the photon becomes undetectable. Since the photon moves along one direction, such as the x-direction, this small disk-like spatial region, in which the photon’s net electric field can be detected, moves along this direction as well. This detectable electric field and small disk-like spatial region have a two-dimensional symmetric plane, such as the xy-plane. As the photon moves along one direction, this small disk-like spatial region becomes a long cylindrical spatial region whose cross-section shape is an elongated ellipse. Also, because the photon’s net electric field has a very short effective interaction distance, the length of this elliptically cylindrical spatial region is not long. The limited length of this elliptically cylindrical spatial region, in which the photon’s net electric field can be detected, is the coherence length of the photon. Sometimes, this limited long elliptically cylindrical spatial region is called a “wave packet.” In this case, the length of the “wave packet” along the photon moving direction is the coherence length of the photon. Within this “wave packet,” the frequency of the electric field vibration is the same, meaning the electric field in this “wave packet” is coherent. Outside this “wave packet,” there is no detectable electric field, and thus the light coherence of this photon disappears.

The photons emitted from the laser appear to have much longer coherence lengths than natural photons, but this is not true. This effect is due to the adoption of techniques such as optical resonator and mode-locking. These techniques ensure that the photons emitted from the laser have the same frequencies. Furthermore, the phases of the photons from the laser are synchronized. This means that the vibrating electric field of an earlier-emitted photon can be accurately connected to the vibrating electric field of a later-emitted photon. Thus, laser light seems to have a much longer coherence length.

- 6.

Origin of the Light Wavelength “Redshift”

In space, there are various electric fields since every celestial body has its own electric field (see also the author's paper titled “Origin of the Gravitational Force” [

6]). Compared with the rapid rotation of the photon electric field, most spatial electric fields in space are almost stationary. The directions of these relatively stationary electric fields in space are not the same as the directions of the photon's straight-line motion or rotation. Thus, both the speeds of the photon's straight-line motion and rotation will be reduced, especially the photon rotation.

When the photon's rotation speed decreases, the photon frequency decreases too. Therefore, the wavelength of the photon will increase, resulting in a light wavelength redshift. In addition, for most celestial bodies in space, their moving speeds are much slower than the speed of photon’s straight-line motion. Thus, most of these celestial bodies will exert towing or resisting electric forces on the photon's straight-line motion. Due to the “Doppler Effect,” this will also reduce the photon frequency and cause the light wavelength to redshift.

Because the photon's net electric field is extremely weak and has a very short effective interaction distance, the influences of external electric fields in space on the photon are extremely small. Therefore, only after extremely long-distance traveling from faraway stars, the photon wavelength redshift can be observed obviously.

The light wavelength redshift can be considered a photon fatigue phenomenon, resulting from decreases in the photon's straight-line motion and rotation speeds. The light wavelength redshift cannot be used as key evidence to support the “Big Bang Theory.”

- 7.

Origin of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

Generally speaking, the speeds of the straight-line motions and rotations of most photons traveling in space will be gradually reduced by external electric fields. However, when reaching very slow speeds, the bottom energy of the universe prevents the photon straight-line motion and rotation speeds from decreasing further. Photons with the slowest speeds of straight-line motion and rotation form the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. Due to the relationship between thermal energy and motion energy, the temperature of any substance in the universe cannot be absolute zero, and thus the photon straight-line motion and rotation speeds cannot be zero either.

The heat death of the universe will not occur even if most photons in the universe eventually become cosmic microwave background radiation. This is because gravitational forces will constantly gather gases, dust, and celestial bodies, including the cosmic microwave background radiation photons, to form new stars, galaxies, and so on. These new stars and galaxies will emit a huge number of new photons and various other microscopic particles into space again, such as the “gamma-ray bursts” from black holes. In this way, the evolution of the universe will take place in these constant cycles.

- 8.

Origin of the Light Bending

As described above, both the gravitational mass and inertial mass of an object are quantitative expressions of the strengths of the external electric fields acting on that object. Since any celestial body can be regarded as an electric dipole (please see the author's paper titled “Origin of the Gravitational Force” [

6]), if a celestial body has a huge mass, generally speaking, it can generate an extremely strong electric field. When a photon travels by the side of that celestial body, the photon's dipole is attracted by it. Thus, the traveling route of the photon will be changed by the attractive force from that celestial body, resulting in light bending.

In most cases, as the photon's net electric field is extremely weak and has a very short effective interaction distance, the attractive electric force from the celestial body on the photon can be neglected, so the photon's moving route is straight in space. However, if the mass of a celestial body is extremely large and its electric field is extremely strong, when the photon is close to that celestial body, the attractive force of that celestial body cannot be ignored. Thus, the phenomenon of light bending will be observed.

The phenomenon of light bending doesn’t need puzzling ideas of “Four-Dimensional Spacetime” and “Curved Spacetime” to explain it.

- 9.

Explanations of Wave-Particle Duality of the Photon and other Microscopic Particles

The electric dipole model of the photon can easily explain the wave-particle duality of the photon. First, the photon electric dipole has rotational electric fields and thus has a set of electromagnetic wave characteristics, including frequency, wavelength, and polarization. Therefore, the light wave composed of the photons can exhibit diffraction, interference, and other typical wave properties, which are the necessary and sufficient conditions for producing wave-like behaviors for the photon.

Second, the core of the photon is an electric dipole consisting of a pair of positron and electron, which are real physical particles. Thus, the photon can cause the events that require real substance particles, such as the photoelectric effect and the Compton effect.

Wave-particle duality is possessed not only by the photon but also by other microscopic particles. The fundamental reason for the wave-particle duality of microscopic particles is that, compared to the particle's mass and volume, the particle's electric field or magnetic field is very large. That is, the influences of the particle's electric field or magnetic field are so significant that the influences of the particle's mass and volume can be ignored or at least almost equal. In other words, in some cases, the particle may be regarded as having no mass and no volume. Thus, only the particle's electric or magnetic field plays a role. In these cases, the particle exhibits its wave property.

However, in some other cases, the non-zero mass or volume of the microscopic particle plays an indispensable role. Thus, microscopic particles exhibit their inherent particle properties because, although the microscopic particle's mass and volume are very small, they are ultimately not zero.

The behavioral characteristics of microscopic particles are significantly different from those of macroscopic objects. Macroscopic objects contain a huge number of microscopic particles. The behavioral characteristics of a macroscopic object are the synthetic result of a large number of microscopic particles. In a macroscopic object, there are numerous microscopic particles, each of them has its electric and magnetic fields. However, most of these electric and magnetic fields offset each other, so the synthetic net electric field and synthetic net magnetic field of the macroscopic object are commonly weak compared with its total mass and volume. Thus, the macroscopic object becomes approximately electrically neutral or magnetically neutral compared with its large mass and volume, meaning that it has almost no net electric or magnetic field and therefore cannot exhibit wave properties.

If a microscopic particle only has an electric field or a magnetic field, it still cannot exhibit its wave property. The particle's electric field or magnetic field must change periodically for the particle to exhibit its wave property.

Apart from the photon, other basic microscopic particles, such as electrons, protons, and neutrons, also have magnetic moments, so their electric fields or net electric fields are rotational. Thus, the electric fields of these particles all have periodic vibrations. The wave property of these particles can be expressed by the De Broglie wavelength formula

where,

is De Broglie wavelength,

is Planck constant,

is the mass of the particle, and

is the velocity of the straight-line motion of the particle. Because the masses of the proton and neutron are much larger than the electron, the De Broglie wavelengths of the proton and neutron are much shorter than the electron.

- 10.

Explanation of the Photoelectric Effect

The observations show that electrons can escape from the metal surface when a light wave irradiates the metal, a phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect or external photoelectric effect. Additionally, when a light wave irradiates certain semiconductors, the conductivity of the semiconductor can be enhanced, and the number of free-moving electrons in the semiconductor can increase. This means that the light wave causes the electrons to leave the atoms in the semiconductor, a phenomenon called the internal photoelectric effect. In the external photoelectric effect, the detached electrons may leave the metal completely and fly into space, whereas in the internal photoelectric effect, the detached electrons merely leave the atoms and travel within the semiconductor.

The observations also show that when the frequency of the light wave is lower than a threshold value, no matter how strong the intensity of the light wave, no electrons fly out from the metal, nor does the conductivity of the semiconductor increase. Furthermore, the observations reveal that the metal has a stopping potential for emitting electrons. When an external electric field produces a potential higher than the stopping potential at the metal surface, no electrons fly out from the metal, regardless of the light wave's intensity. The existence of the threshold frequency and stopping potential in the photoelectric effect cannot be explained by the wave property of light.

The photoelectric effect is easily explained using the electric dipole model of the photon. In this model, the photon has a waved electric field and a real particle core. Because the photon core is composed of a positron and an electron, the photon dipole can collide with the electron of the atom, or even with the nucleus of the atom in the metal or semiconductor. After the collision, the electron in the atom within the metal or semiconductor leaves its atom, or more likely, the photon dipole is split into a positron and an electron. The knocked-out electrons or the split positrons and electrons move to the anode and cathode through space in the external photoelectric effect or through a circuit in the internal photoelectric effect. Thus, the electric current flows from the anode to the cathode via space and circuit or only through the circuit continually.

However, to make the electrons leave their atoms or to successfully split the photon dipole, the photon must have enough energy to collide with the electrons or the nuclei in the atoms of the metal or semiconductor. The photon's energy is composed of straight-line motion and rotation energies. Since the speed of light is constant in most circumstances on Earth (although it is approximately invariant), the photon's straight-line motion energy is fixed. Different photons have different rotational energies. Obviously, the faster the rotation, the higher the photon's total energy. Thus, to make the electron in the atom leave its atom in the collision or to split the photon dipole in the collision, the rotational speed of the photon must be the same as or higher than the threshold value that corresponds to a specific metal or semiconductor. In other words, for the collision to be effective, the rotational speed of the photon must be the same as or higher than that special threshold value. This explains why a photon can eject an electron or be split when the photon's frequency is the same as or higher than the threshold frequency.

The stopping potential arises because the knocked-out or split electrons have certain straight-line motion energy. The external electric field exerts an electric force on the metal surface, producing an electric potential. If the straight-line motion energy of the knocked-out or split electron is less than the stopping potential energy produced by the external electric field, the electron cannot be emitted from the metal. Note that different metals have different surface electric potentials, which affect the electric stopping potential for the knocked-out or split electron to exit the metal.

When split positrons and electrons travel in the metal or semiconductor, their motion energies decrease due to interactions with the electric fields of the electrons and protons in the atoms of the metal or semiconductor. Some of the lost energy becomes potential energy between the anode and cathode. When the split positrons and electrons recombine in the metal or semiconductor, including in the circuit, they form new photons. However, because their motion energies, particularly their rotational energies, have been reduced, these new photons become thermal radiation photons with lower energies. They are the main source of heat in the circuit.

- 11.

Explanation of the Compton Effect

The Compton Effect describes such a physical phenomenon: when a high-energy light beam, such as X-ray, is scattering by certain materials, some of the scattered light will have lower frequency than the incident light beam. The change of the frequency depends on the scattered angle. If the wavelength of the incident light beam is , and the wavelength of the scattered light beam is λ, then . In addition, the wavelength difference increases with the increase of the scattering angle θ, the intensity of the light beam with wavelength of decreases with the increase of the scattering angle θ.

In fact, the Compton Effect is a proof for electric dipole model of the photon, which indicates that the photon has straight-line motion energy and rotational energy. When a photon collides with the atom in the scattering material, the direction of the photon straight-line motion will change, and so the scattered light beams go along different scattering angles of θ. In addition, in the collisions, the rotational energies of some photons will change too, and the more violent the collision, the larger the photon rotational energy changes. Thus, the wavelength difference of the scattering light beam increases with the increase of the scattering angle θ. In addition, the more violent collision will change the photon straight-line motion direction larger, and because there are less photons participating in the more violent collisions, the intensity of the light beam with wavelength of decreases with the increase of the scattering angle θ. Please note that some photons change their straight-line motion directions but not their rotational speeds during the collisions, so the light beam with wavelength may still be observed at different scattering angles θ. This should be an extremely difficult point to explain for Compton effect.

- 12.

Origin of the Light Pressure

According to current theory, the photon's "gravitational mass" and "inertial mass" are zero, making the phenomenon of light pressure difficult to understand.

However, as described above, the photon dipole model indicates that photon has its net synthetic electric field, which can exert an electric force on another object. Thus, the photon can exert real physical pressure on another object. In other words, light pressure can be produced because the photon's "inertial mass" is not zero.

- 13.

Difference between Light and Electromagnetic Wave and Key for Photosynthesis

Currently, people believe that light is an electromagnetic wave, meaning they are the same thing. However, the author indicates that this understanding is incorrect. A pure electromagnetic wave consists only of periodically vibrating electric and magnetic fields, while light is a "wave packet," which includes the periodically vibrating electric and magnetic fields plus a real substance particle core consisting of a positron and an electron. Therefore, a pure electromagnetic wave only has wave properties, whereas light, that is, photons, has wave-particle duality.

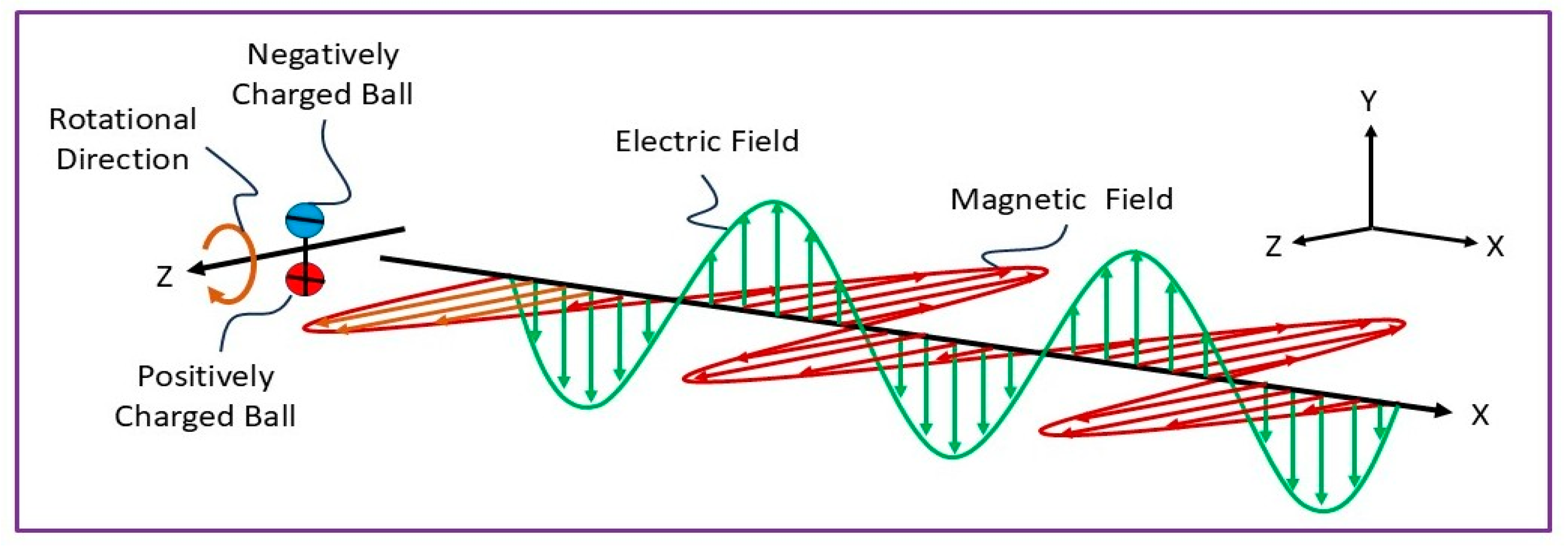

Perhaps this difference can be proven by conducting the following experiment. See the setup of the experiment shown in

Figure 4. Let a pair of two charged balls (the red ball is positively charged and the blue ball is negatively charged) rotate around the z-axis. The rotating charged balls generate a vibrating electromagnetic wave that propagates along the x-axis. The generated electric field vibrates in the xy-plane, while the generated magnetic field vibrates in the xz-plane. If an observer detects in the positive x-axis direction, the observer will only receive the vibrating electromagnetic wave and will never receive any real substance, such as the positron or electron. This is because the electric charges on the two balls do not fly away from the charged balls.

However, if the observer detects a light beam propagating along the x-axis, the situation is completely different. As mentioned above, the observer can receive not only the vibrating electromagnetic waves produced by the rotations of the photon dipoles but also real substances, namely the cores of the photons—the positron and electron pairs.

Because of this key difference between light and electromagnetic waves, some physical processes caused by light will not be caused by pure electromagnetic waves. Photosynthesis should be a typical example.

Photosynthesis plays a critical role in producing and maintaining the green life systems on Earth [

15]. The general equation for photosynthesis, as first proposed by Cornelis van Niel, is [

16]

Since water is used as the electron donor in oxygenic photosynthesis, the equation for this process is

In Eqs. (11) and (12), and are electron donor and oxidized electron donor. , and (an equivalent expression of ) are water, carbon dioxide and glucose molecules.

We can see that, in the photosynthesis process, electrons and hydrogen ions are necessary for the light reactions and carbon reactions. However, there are very few free electrons and hydrogen ions in water and carbon dioxide gas, which are the raw materials involved in photosynthesis. Therefore, light illumination is a key step for completing photosynthesis because the electrons and hydrogen ions can only be produced by the collisions between the photons and water molecules. In other words, many hydrogen atoms in water molecules must be split into electrons and hydrogen ions via hit by photons. More likely, the photons are split into electrons and positrons to participate in the photosynthesis process.

In this way, the light-dependent photosynthesis process is not only a biological process converting light energy, typically from sunlight, into chemical energy, but also a real substance-moving process, combining the electrons and positrons split from photons with other compounds to produce sugar (glucose), dioxygen gas, and water.

Therefore, the photosynthesis process can only be caused by light and not by pure electromagnetic waves.

- 14.

Truth of the Light Speed

The speed of light is one of the most basic parameters describing the universe. The most famous measurement of the speed of light is the Michelson-Morley experiment. Its result is well known worldwide: the speed of light in a vacuum has the same magnitude relative to all inertial reference frames, no matter what their velocity may be relative to each other.

First, the Michelson-Morley experiment shows that there is no "Ether" in the universe or that the Earth is not moving through the "Ether." It shows that there is no medium for light wave propagation. This is different from the propagation of water waves or acoustic waves. The medium transmitting the water wave is water, and the medium transmitting the acoustic wave is air. The propagation speeds of water and acoustic waves depend on the transmission mediums. The water wave speed relative to an observer is the sum of the water wave speed in the water and the speed of water relative to the observer. Similarly, the acoustic wave speed is the sum of the acoustic wave speed in the air and the air speed relative to the observer.

As described above, the propagation of the light wave is simply the movement of the photon itself, which is the actual physical particle moving through space, and no transmission medium is needed. In the Michelson-Morley experiment, since there is no "Ether" medium in space to transmit the light wave, the light speed cannot be changed by the "Ether," and thus the measured light speed is constant.

The real terrible fact revealed by the Michelson-Morley experiment is that the speed of light in a vacuum has the same magnitude relative to all inertial reference frames, regardless of their velocity relative to each other. Many people have tried their best to answer this challenge, but no satisfactory result has been found.

Now, the electric dipole model of the photon can provide a completely unexpected and reasonable answer to this perplexing problem.

As described above, the photon has straight-line and rotational motions, and the change in its straight-line motion speed doesn’t affect its rotational motion speed. In other words, the change in the straight-line motion speed of the photon can’t change its rotational frequency. Of course, if the speed of one reference frame relative to another reference frame reaches an excessive value, the observed photon frequency in the two reference frames may be different due to the "Doppler Effect." Thus, in most cases, the frequency of the photon is almost only determined by its rotational speed. Because the photon frequency has almost no relation to its straight-line motion speed, when the observer is in any of the inertial reference frames, no matter what the velocity of that reference frame is relative to another reference frame, the frequency of the photon observed by that observer is the same.

For example, there are two observers in two inertial reference frames, A and B. Frame A moves at a speed of relative to frame B.

If a photon with a frequency of is observed by the first observer in frame A, and if the straight-line motion speed of the photon is relative to frame A, then, for the second observer in frame B, the straight-line motion speed of the photon becomes , and the photon frequency becomes for the second observer, where is the frequency shift caused by the Doppler effect due to the speed difference of .

Thus, if is not excessively large, because of , we have . The observed frequencies of the photon are the same for the two observers in the two inertial reference frames when the speed difference between the two frames is not excessively large.

In many measurements of the speed of light, the obtained value is deduced from the measured light frequency, as in the Michelson-Morley experiment. Thus, the calculated speed of light appears invariant. Of course, this is also because, in the Michelson-Morley experiment, the Earth's speed is not excessively large compared to the speed of light.

The traditional concept that the speed of light and light frequency are closely related is incorrect, which has thoroughly confused people and prevented them from fully understanding the truth about the speed of light.

In fact, there are many factors that need consideration for light speed measurement. For example, apart from the speed of the light source itself, what are other causes affecting the initial speed of the photon when it leaves its light source? Note that not only in the macroscopic light source, but even in every atom of the light source, the space within each atom is mostly empty, and the different electrons, protons, and neutrons move with different speeds and directions. It is too simplistic to think that the initial speeds of different photons must add the same speed of their macroscopic light source when these photons leave their macroscopic light source.

In fact, one should ask why the initial speeds of different photons emitted from different atoms in the light source are the same or approximately the same. To answer this question, one needs to know more details about the structure and characteristics of atoms. The author also can't give a reasonable answer now.

But it is certain that the speed of light in a vacuum is not a constant. According to the electric dipole model of the photon, when the electric field of the photon interacts with an external attractive or repulsive electric field, the speed of the photon's straight-line motion and rotation will be decelerated or accelerated, thus causing the speed of light to change.

In fact, this inference has been indirectly proved by astronomical observation. As mentioned above, when a light beam passes by the side of a celestial body with a huge mass, the traveling route of the beam, that is, the path of the photons, will be bent. Thus, light bending occurs. This indicates that the photon speed changes in the tangent direction of the straight-line motion. If the photon speed may be changed in the tangent direction of its straight-line motion, then if a celestial body with huge mass is located in the normal direction of the photon's straight-line motion, such as a massive black hole, why can’t the photon speed along the normal direction be changed? The answer should be yes without any doubt. Astronomical observations seem to have seen some signs of the “accelerated collapse” of any object, including photons, towards the center of a massive galaxy.

There are two possible reasons for the so-called “light speed is a constant in a vacuum” until now. One reason is that the photon's synthetic net electric field is very weak and has a very short effective interaction distance, making it difficult to detect a change in light speed. Another reason is that some phenomena showing light speed change have been misunderstood, such as the redshift of light wavelength and light bending.