Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Requirements elicitation from multiple human sources involves information validation and conflicts resolution to deal with uncertainty inherent in the process. Most requirements analysis methods focus on expressing the requirements and ignore the uncertainty inherent in the process of requirements elicitation. This paper build on the work presented by the author in [1,10], where a method for requirements elicitation from multiple sources was presented. This paper gives an overview of the method and presents detailed case studies. The cases studies were designed to illustrate different aspects of the Source Control Method and to determine its feasibility and its practical utility as a problem investigation and information validation technique.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

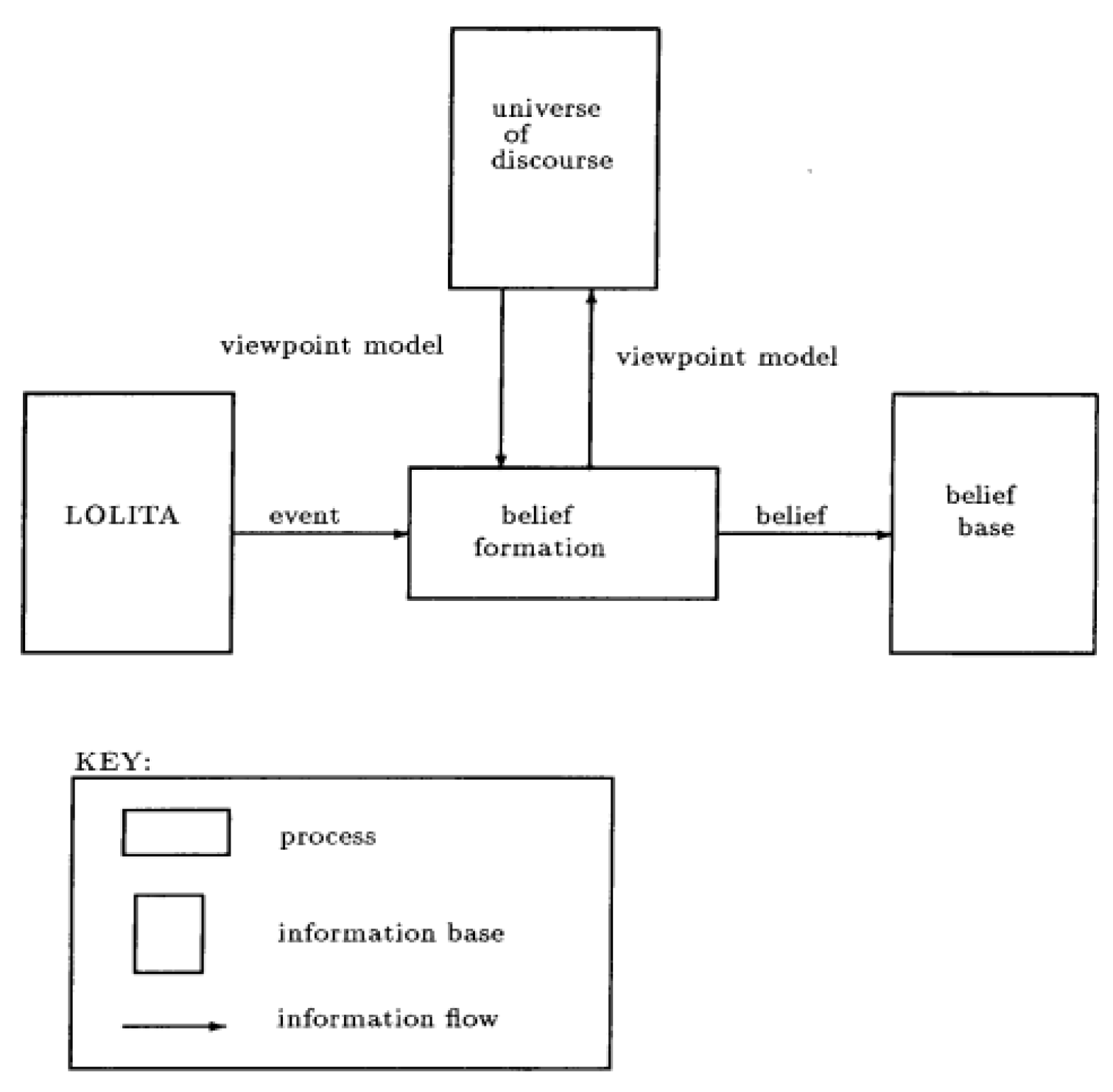

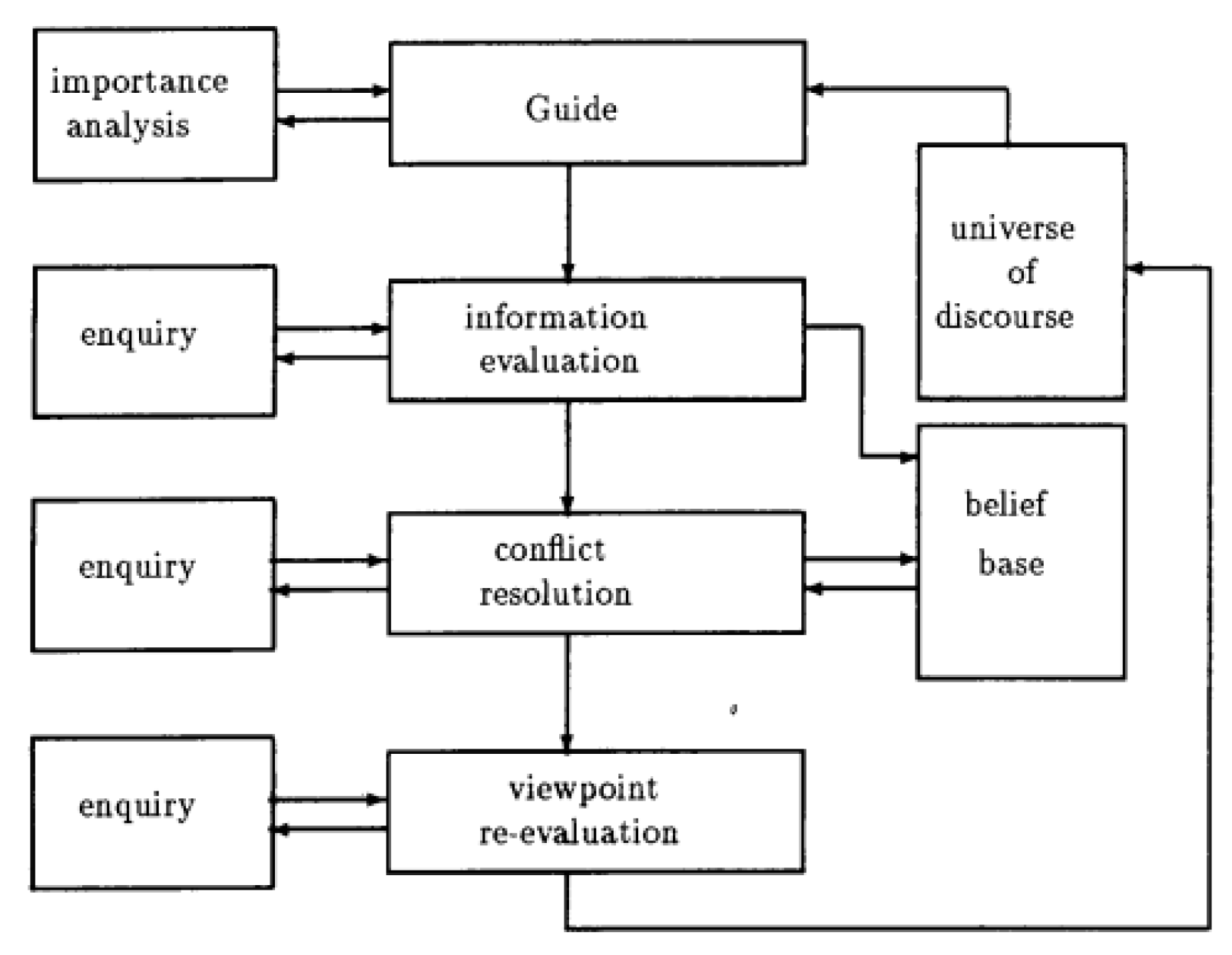

2. An Overview of the Method

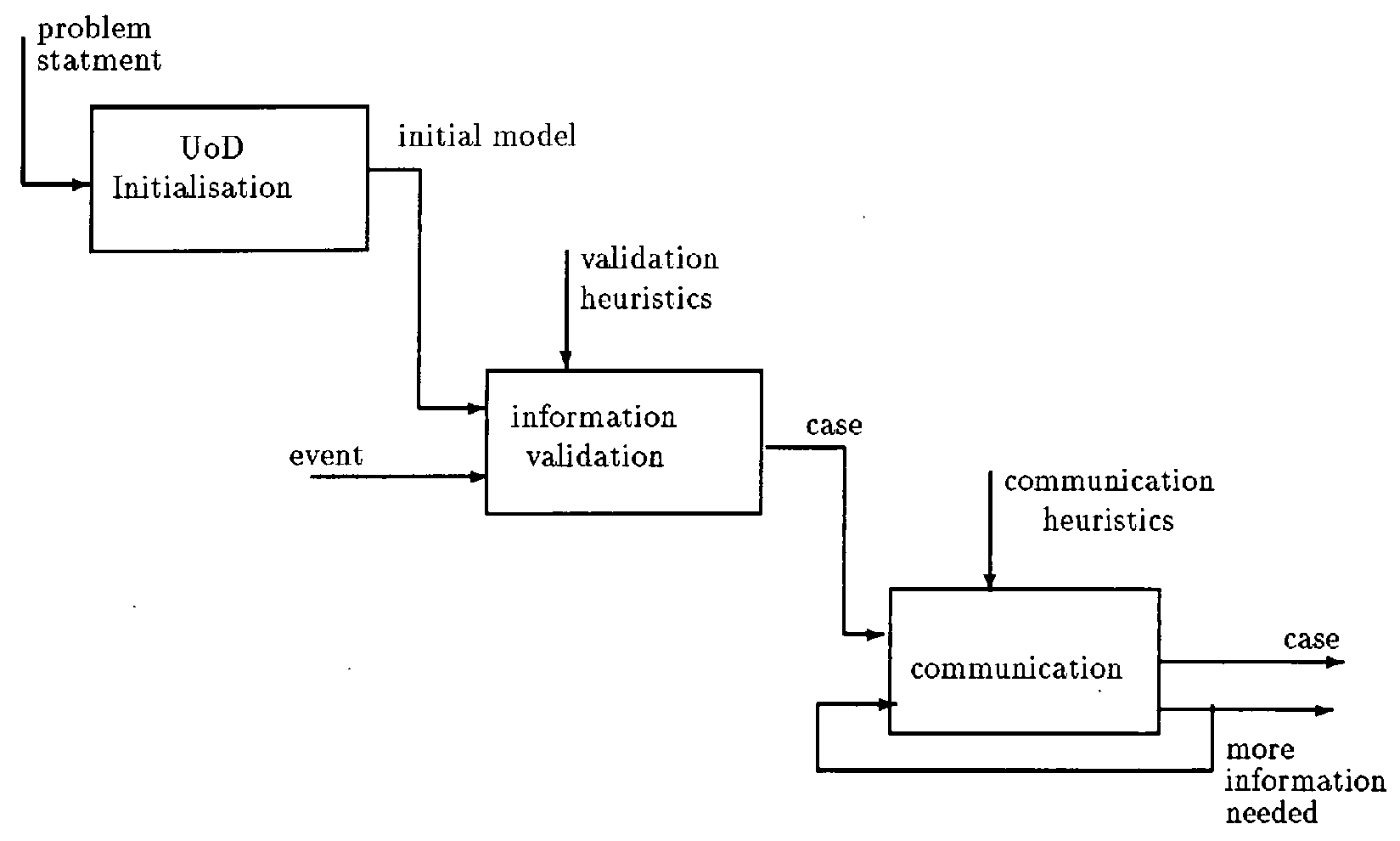

- Universe of Discourse Initialization

- ○

- Information Validation

- ○

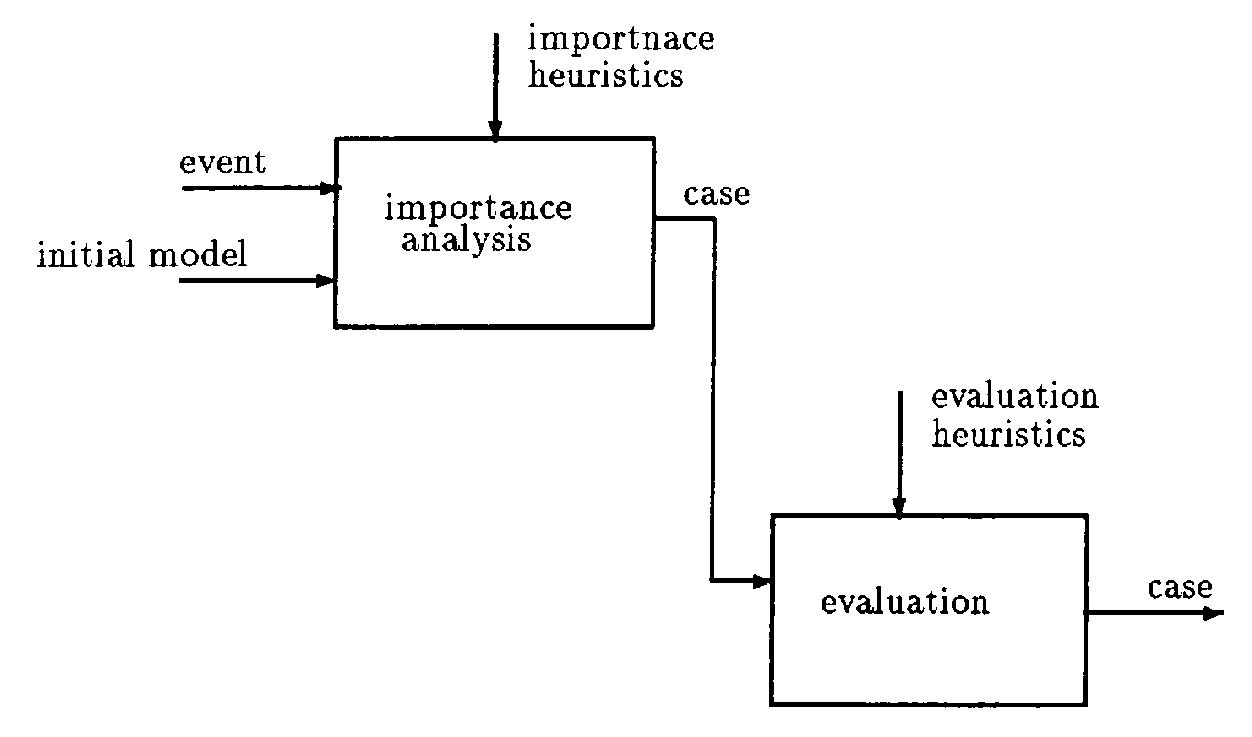

- Importance Analysis

- ○

- Information Evaluation

- Communication

- ○

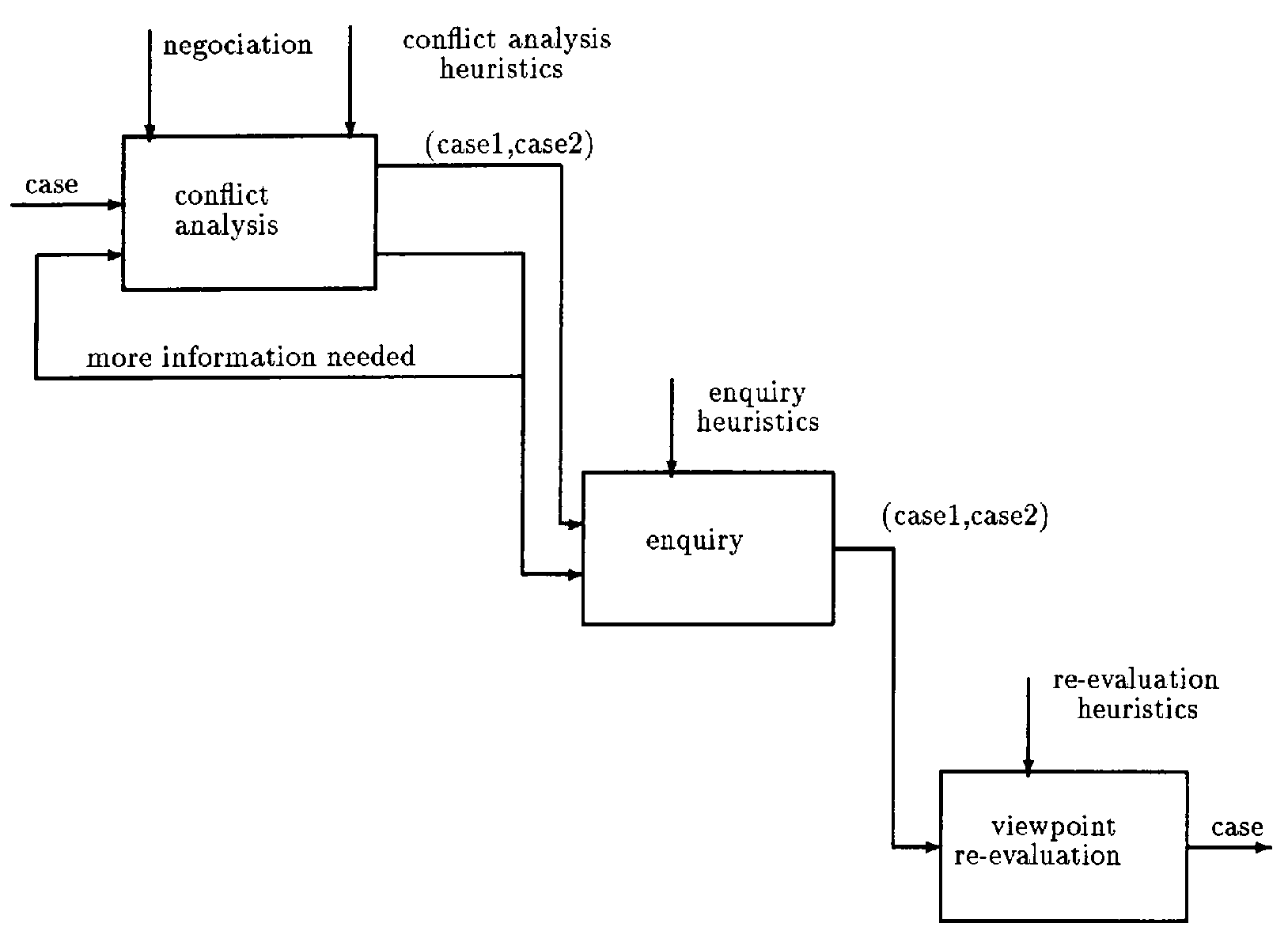

- Conflict analysis

- ○

- Enquiry

- ○

- Universe of Discourse Update

3. The Case Studies

- a changing environment/context,

- different people (different skills, goals, commitments),

- many sources of information, and

- various constraints, such as time, money, etc.

3.1. Case Study 1

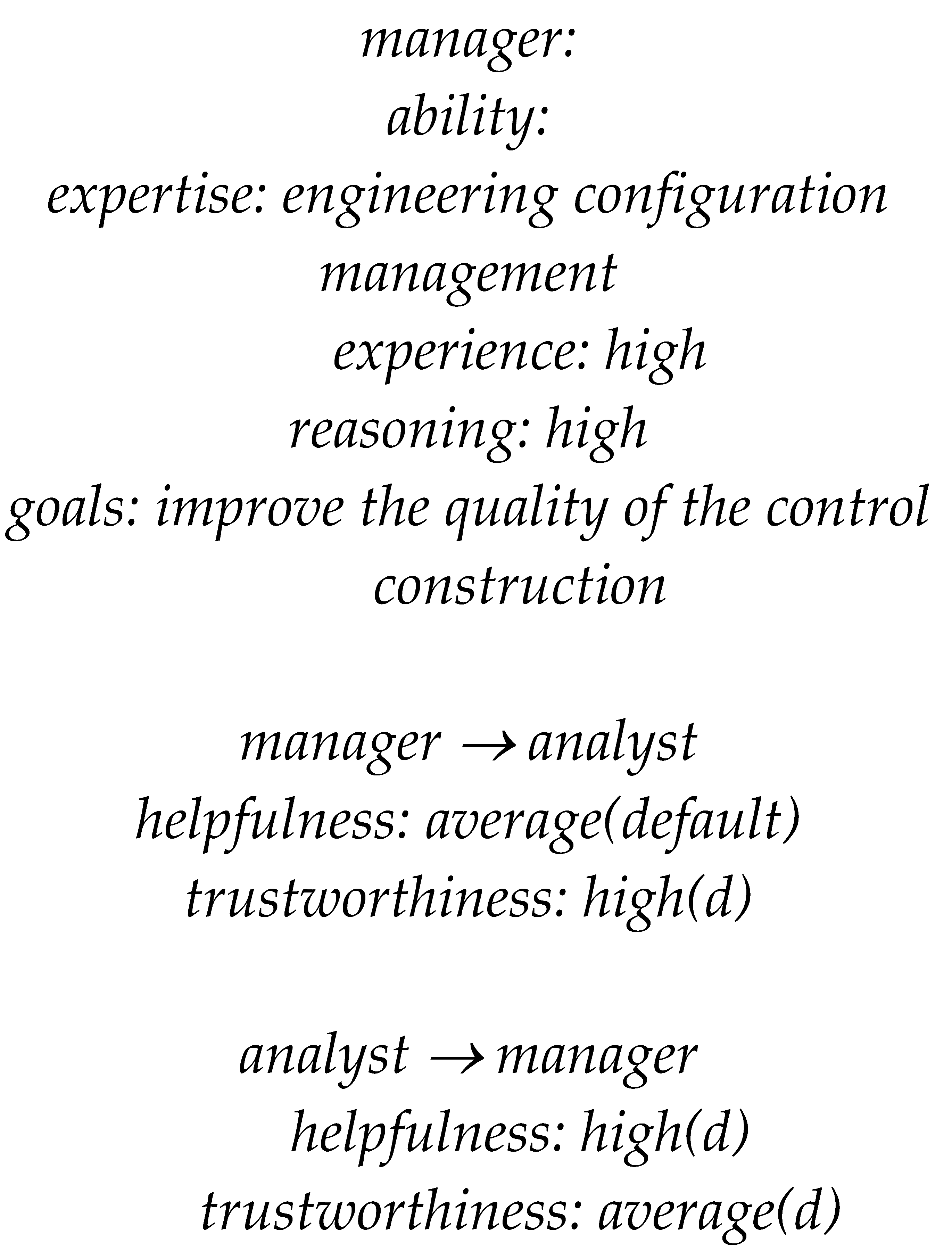

3.1.1. Has the Manager a Business Case?

3.1.2. Initial Universe of Discourse

3.1.3. Importance Analysis

3.1.4. Information Evaluation

3.1.5. Enquiry

3.1.6. Conflict Resolution

3.1.7. Universe of Discourse Update

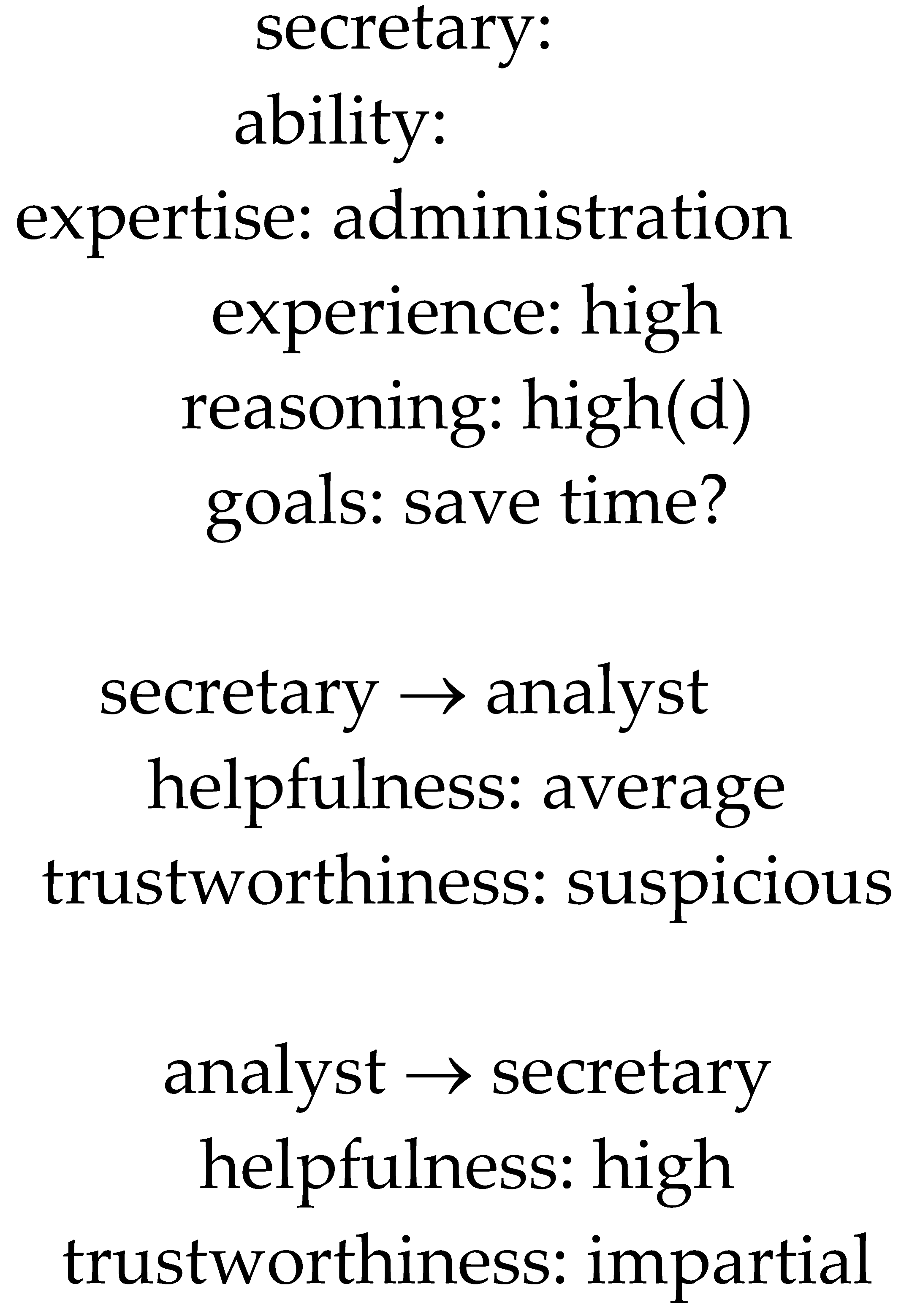

3.2. Case Study 2

3.2.1. Route Generation and Selection

3.2.2. Universe of Discourse Initialization

3.2.3. Importance Analysis

- similar structure and similar goals

- similar structure and different goals

- different structure and similar goals

3.2.4. Information Evaluation

3.2.5. Universe of Discourse Update

3.2.6. Group Decision

- Each member of SET is asked to give their evaluation of the proposed solutions with respect to each criterion (i.e. with respect to the satisfaction of their private goal). The results of this phase of consultation is expressed in a matrix form. The elements of the matrix represent the 'linguistic performance' that the group have attributed to each solution with respect to each criterion, (that is, choosing a linguistic label represented by 'fuzzy numbers' in a term set V, the range of which is pre-defined. For example: V = (very low, low, medium, high, very tight),

- Taking into account the weights of the viewpoints, recorded in the viewpoint models, a consensus strategy is identified using a 'cost for changing opinion' (some form of commitment). There are two stages:

- identify candidate solutions for the discussion (eliminate those whose total value - as judged by the viewpoints - does not pass a fixed threshold),

- evaluate the remaining solutions again after a discussion based on the advice of the consensus strategy, which in turn is based on the 'cost for changing opinion': this process may be repeated a number of times depending on various elements. The weights assigned to the viewpoints can also be changed as a result.

- Change the weights of the viewpoints.

4. Summary and Conclusions

- the coordination of the different analysis techniques via the viewpoint models and the cases, thus the production of an all-important learning feed-back,

- the flexibility of the technique: the technique can be adapted to different situations in different domains. No order is imposed on performing the analysis tasks, e.g., iteration between conflict resolution and viewpoint re-evaluation, and no specific representation is imposed for expressing the facts,

- the important role human factors play even in technical decisions,

- the ability to detect inconsistencies, wrong information, and incompleteness as the requirements evolve,

- the exploitation of the correlation between inconsistency, incorrectness and incompleteness problems in order to make the maximum use of the information available,

- the utility of the method in supporting group decisions under uncertainty by recording information about the participants, and

- the use of a natural language environment such as LOLITA.

5. The Limitations of the Approach

6. Tool Support

References

- [1] Messaoudi, M. (2022). A Model for Requirements Validation through Viewpoint Control. International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887, Volume 184 – No.4, March 2022.

- [2] Fickas, S. and Nagarajan, P, (1988). Critiquing Software Specification, IEEE Software. 37-46.

- [3] Finkelstein, A. and Potts, C. (1985). Evaluation of Existing Requirements Extraction Strategies, Alvey FOREST project.

- [4] Finkelstein, A. (1988). Reuse of Formatted Requirements Specifications, Software Engineering Journal. 186-197.

- [5] John, S. , Anderson, S. and Fickas, S, (1988). A Proposed Perspective Shift: Viewing Specification Design as a Planning Problem, ACM Sigsoft, Software Engineering Notes, 14(3). 177-184.

- [6] Leite, J. (1988). Viewpoints Resolution in Requirements Elicitation, Ph.D. thesis, Department of Computer Science, University of California, Ivrine.

- [7] Leite, J. and Freeman, P., (1991). Requirements Validation Through Viewpoint Resolution, IEEE transactions on Software Engineering 17(12).

- [8] Lehman, M. (1990). Uncertainty in Computer Applications is Certain - Software Engineering as a Control, Imperial College Research Report DOC 90/2.

- [9] London, K.R. (1976). The People Side of Systems: The Human Aspects of Computer Systems, McGRAW-HlLL Book Company (UK) Limited.

- [10] Messaoudi, M. (1994). Requirements Elicitation Through Viewpoint Control in a Natural Language Environment, Ph.D. thesis, Department of Computer Science, University of Durham, UK.

- [11] Mullery, P. (1985). Acquisition-Environment, in Distributed Systems: Methods and tools for the specification, Spriner-Verlag.

- [12] Mullery, G. (1979). CORE - A method for Controlled Requirements Expression, Proc. of Fourth IEEE Int. Conf. on Soft. Eng., Munich, Germany.

- [13] Garigliano, R. , Morgan, R.G., and LOLITA Group : The LOLITA Project: the First Eight Years, under negotiation with Lawrence Earlbaun, UK, 1993.

- [14] Ross, D.T. and Schoman, K.R. : Structured Analysis for Requirements Definition, IEEE Trans. Software Engineering, Vol. SE-3, No. 1, 1977, pp. 16-34.

- [15] Mich, L. and Garigliano, R. : Negotiation and Conflict Resolution in Production Engineering Through Source Control, Technical report. Department of Computer Science,University of Durham, 1994.

- [16] Brackett, J.W. : Sofware Requirements, in Standards, Guidelines, and examples on System and Software Requirements Engineering, M. Dorfman and R. H. Thayer (ed.), 1990.

- [17] Fedrizzi, M. , Mich, L., and Gaio, L. : A Fuzzy Logic-Based Model for Consensus Reaching in Group Decision Support, in Proc. of International Conference on Software Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems (IPMU'92), Spain, pp 301-304, 1992.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).