Submitted:

07 October 2023

Posted:

08 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Identifying and Filtering the Tools

2.2. Identifying the Tool Features

2.2.1. Project Management

2.2.2. Collaboration

2.2.3. Requirements Specification

2.2.4. Customisation

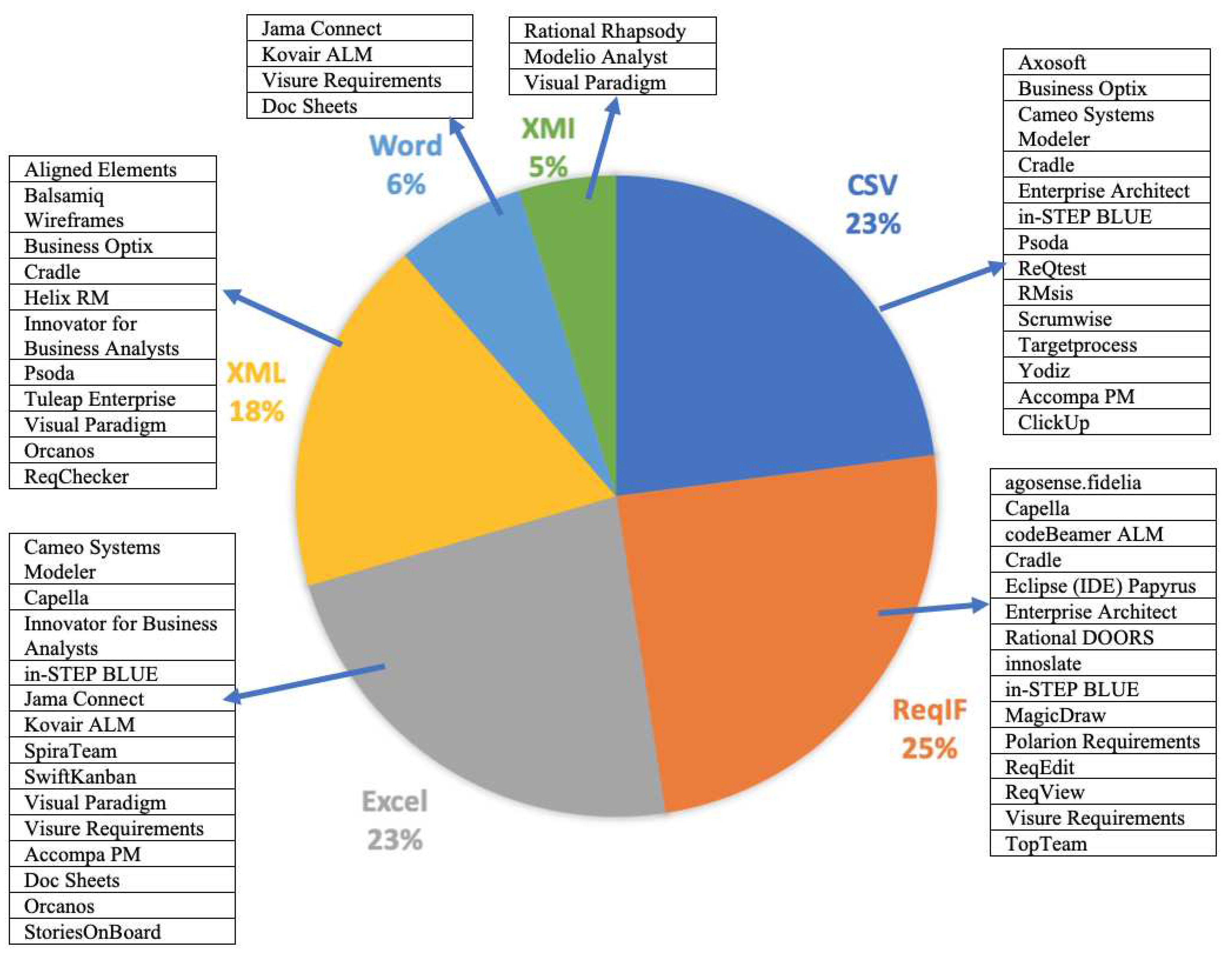

2.2.5. Interoperability

2.2.6. Methodology

2.2.7. Knowledge Management

2.3. Collecting and Analysing the Data

3. The Analysis of the Requirements Engineering Tools

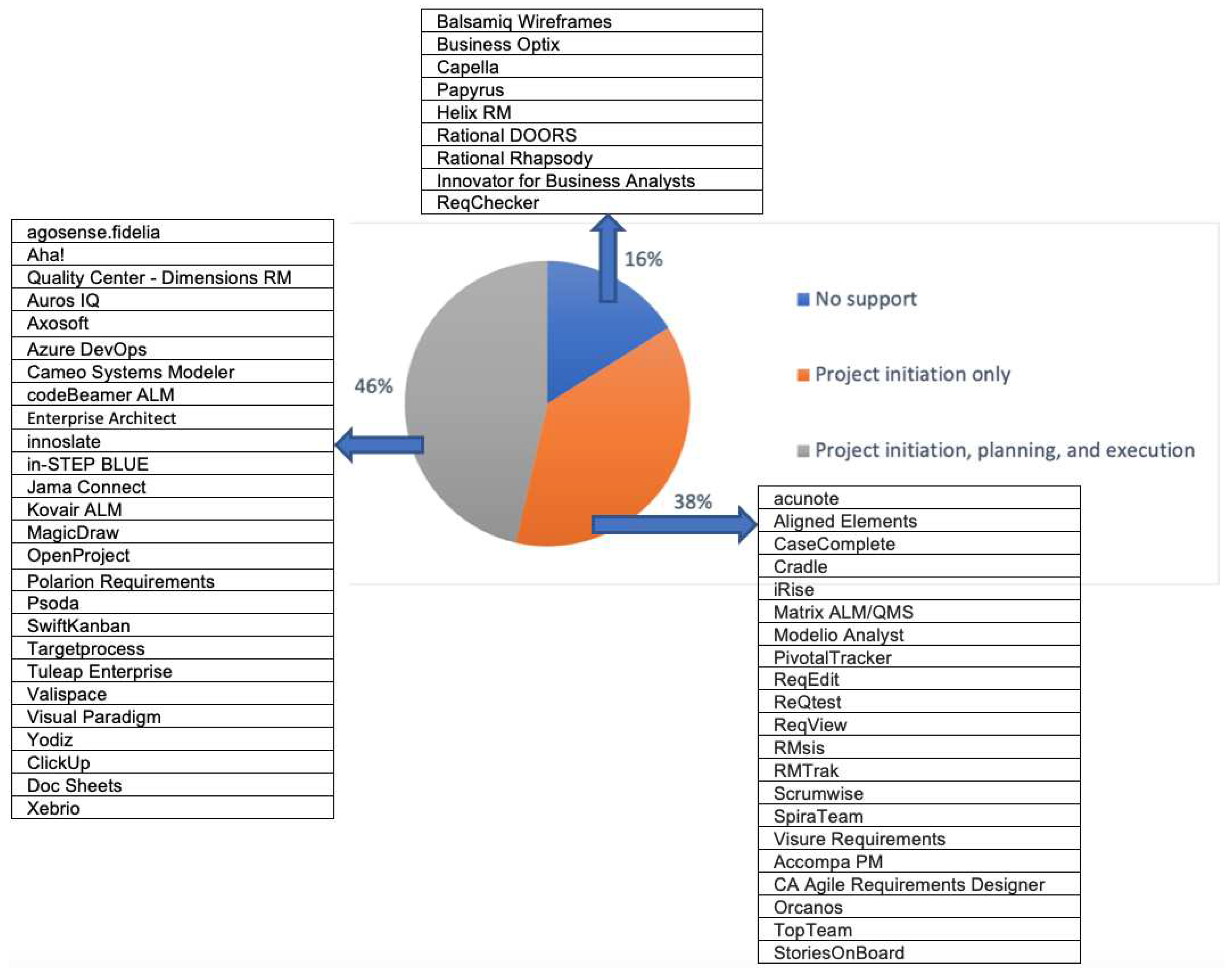

3.1. Project Management

3.2. Collaboration

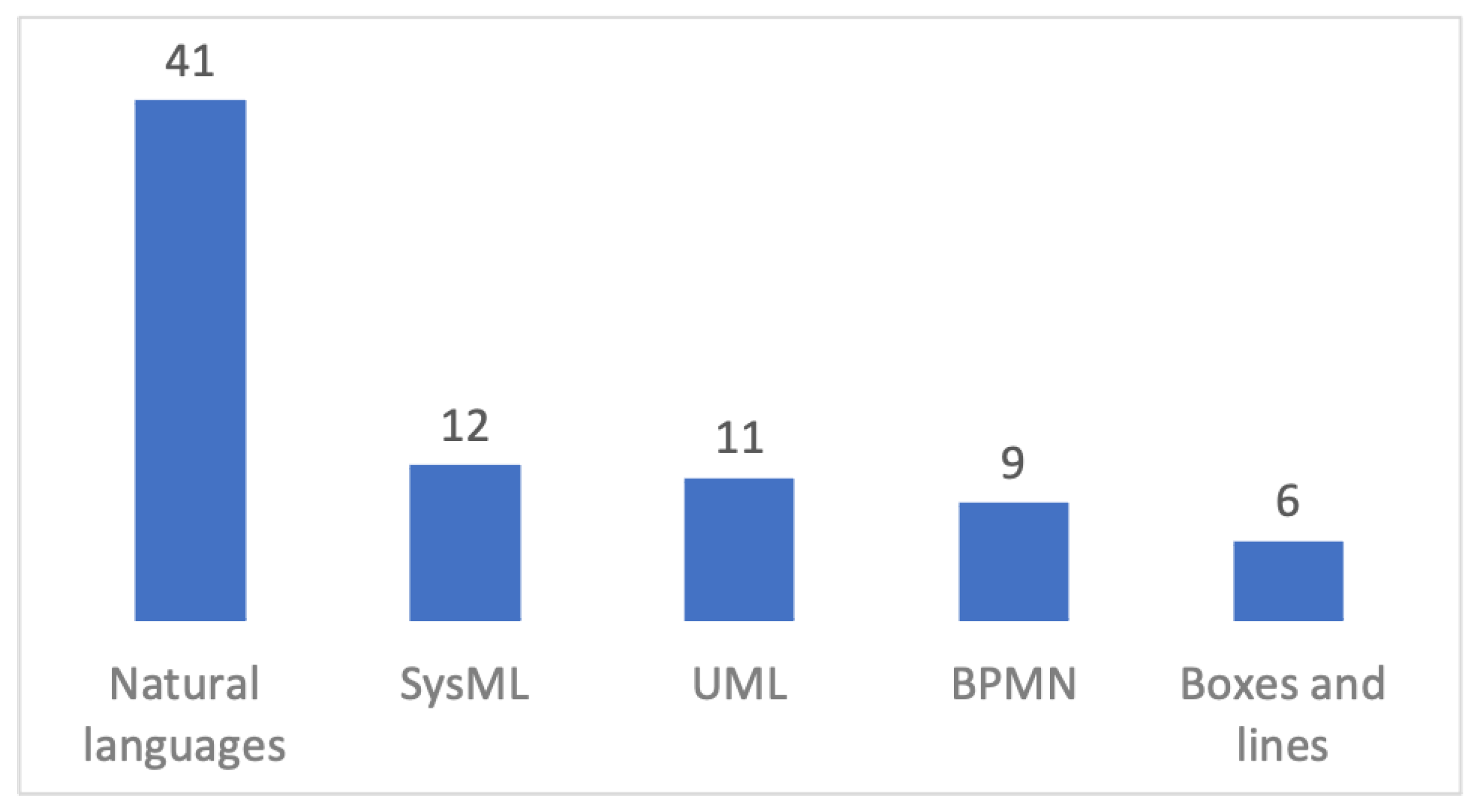

3.3. Requirements Specification

3.4. Customisation

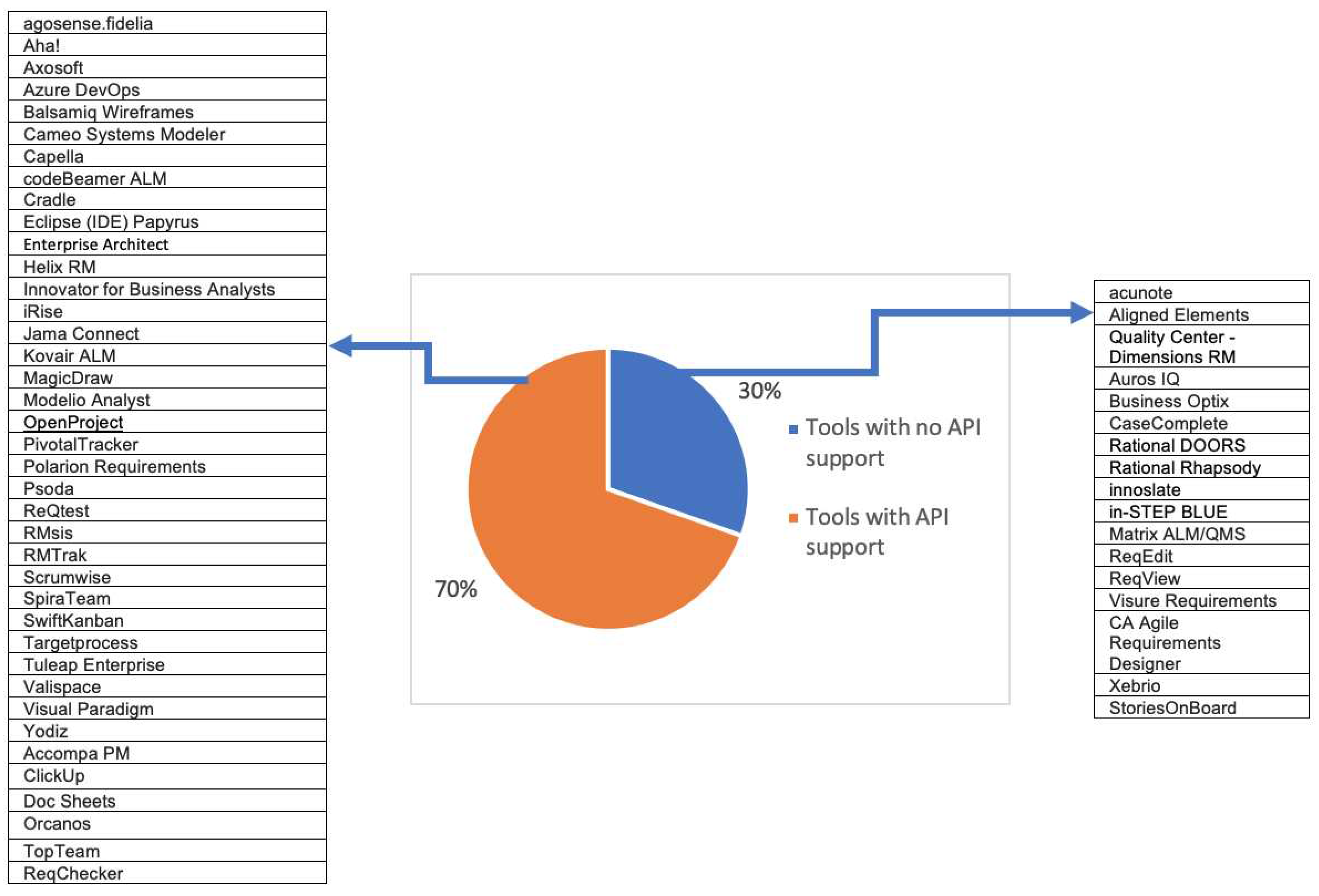

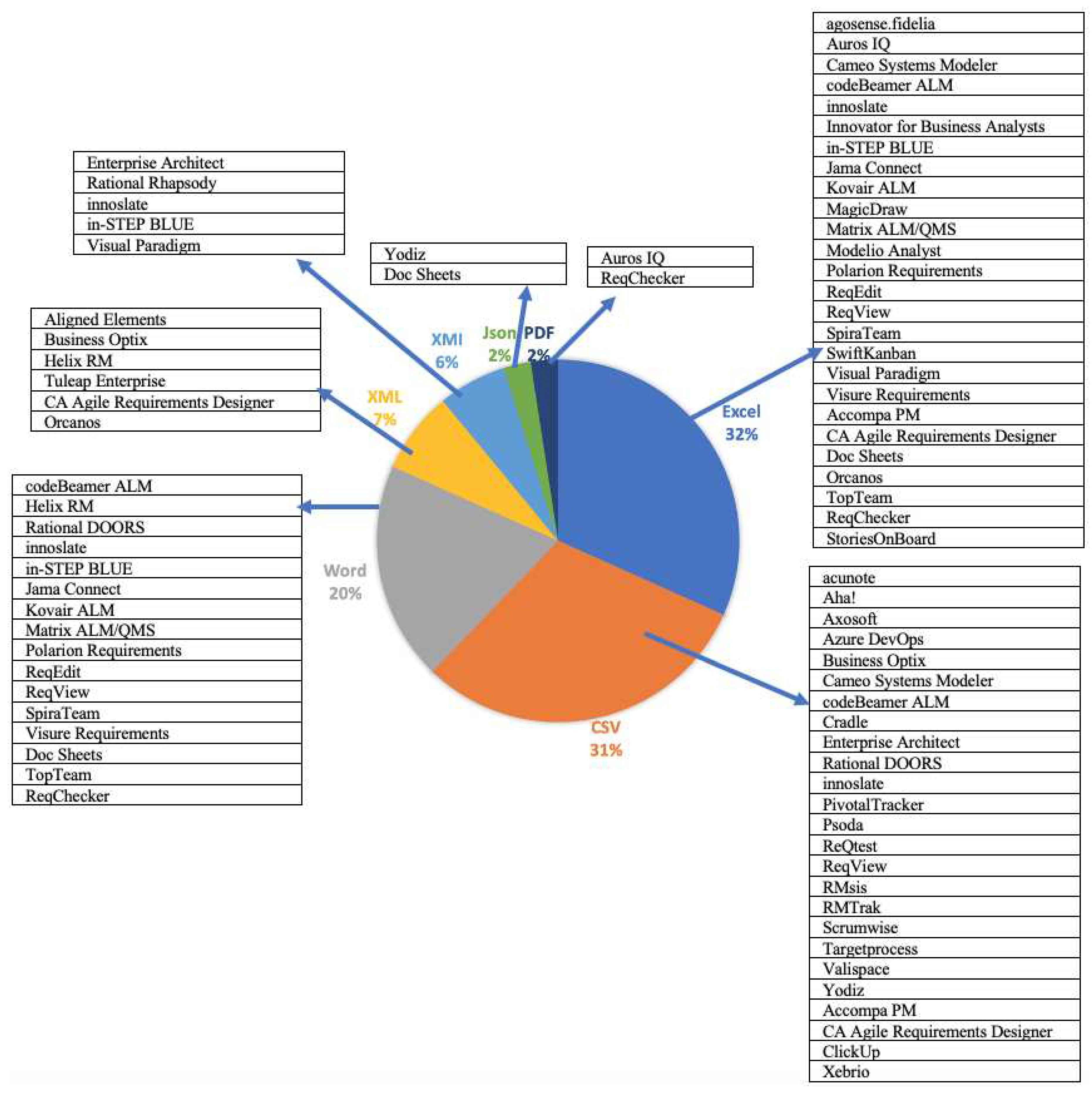

3.5. Interoperability

3.6. Methodology

3.7. Knowledge Management

4. Discussions

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Lessons Learned

4.3. Threats to Validity

5. Related Work

6. Conclusion

References

- IEEE Standard for Application and Management of the Systems Engineering Process. IEEE Std 1220-2005 (Revision of IEEE Std 1220-1998) 2005, pp. 1–96. [CrossRef]

- (Ed.), R.A. Guide to the Systems Engineering Body of Knowledge (SEBoK), version 1.9, 2017. Online; accessed 01 Apr 2023 13:56:12 UTC.

- Lethbridge, T.C.; Lagamiere, R. Object-oriented software engineering - practical software development using UML and Java; MacGraw-Hill, 2001.

- Curcio, K.; Navarro, T.; Malucelli, A.; Reinehr, S.S. Requirements engineering: A systematic mapping study in agile software development. J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 139, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuseibeh, B.; Easterbrook, S. Requirements Engineering: A Roadmap. Proceedings of the Conference on The Future of Software Engineering; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, P.A. Requirements Engineering for Software and Systems, Third Edition, 3rd ed.; Auerbach Publications: USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, K. Requirements Engineering: Fundamentals, Principles, and Techniques, 1st ed.; Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2010.

- Humphrey, W. Why Big Software Projects Fail: The 12 Key Questions. Software Management 2006, pp. 21–26.

- Charette, R. Why software fails [software failure]. IEEE Spectrum 2005, 42, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Mkpojiogu, E.O.C. Requirements: Towards an understanding on why software projects fail. AIP Conference Proceedings 2016, 1761, 020046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.; Jastram, M. ReqIF: Seamless Requirements Interchange Format between Business Partners. IEEE Softw. 2012, 29, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, M.; Akdur, D.; Toptani, E.C.; Kocak, B.; Kardas, G. Practitioners’ Perspectives towards Requirements Engineering: A Survey. Syst. 2023, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, M. Are the UML modelling tools powerful enough for practitioners? A literature review. IET Software 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J. The Project Management Life Cycle: A Complete Step-By-Step Methodology for Initiating, Planning, Executing & Closing a Project Successfully; Kogan Page, Limited, 2006.

- Taylor, R.N.; Medvidovic, N.; Dashofy, E.M. Software Architecture - Foundations, Theory, and Practice; Wiley, 2010; pp. I–XXIV, 1–712.

- Rumbaugh, J.E.; Jacobson, I.; Booch, G. The unified modeling language reference manual; Addison-Wesley-Longman, 1999; pp. I–XVII, 1–550.

- Balmelli, L. An Overview of the Systems Modeling Language for Products and Systems Development. J. of Obj. Tech. 2007, 6, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völzer, H. An Overview of BPMN 2.0 and Its Potential Use. Business Process Modeling Notation - Second International Workshop, BPMN 2010, Potsdam, Germany, October 13-14, 2010. Proceedings; Mendling, J.; Weidlich, M.; Weske, M., Eds. Springer, 2010, Vol. 67, Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, pp. 14–15. 13 October. [CrossRef]

- Feiler, P.H.; Gluch, D.P.; Hudak, J.J. The Architecture Analysis & Design Language (AADL): An Introduction. Technical report, Software Engineering Institute, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zowghi, D.; Gervasi, V. On the interplay between consistency, completeness, and correctness in requirements evolution. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2003, 45, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Recommended Practice for Architectural Description for Software-Intensive Systems. IEEE Std 1471-2000 2000, pp. 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Selić, B.; Gérard, S. Chapter 2 - An Introduction to UML Profiles. In Modeling and Analysis of Real-Time and Embedded Systems with UML and MARTE; Selić, B., Gérard, S., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: Boston, 2014; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringert, J.O.; Rumpe, B.; Schulze, C.; Wortmann, A. Teaching Agile Model-Driven Engineering for Cyber-Physical Systems. 39th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering Education and Training Track, ICSE-SEET 2017, Buenos Aires, Argentina, May 20-28, 2017. IEEE Computer Society, 2017, pp. 127–136. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Ramesh, B.; Sugumaran, V. Integrating Software Product Line Engineering and Agile Development. IEEE Softw. 2010, 27, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model-Driven and Software Product Line Engineering. In Model-Driven and Software Product Line Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012; chapter 4, pp. 101–138, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781118561379.ch4]. [CrossRef]

- Dingsøyr, T.; Nerur, S.; Balijepally, V.; Moe, N.B. A decade of agile methodologies: Towards explaining agile software development. Journal of Systems and Software 2012, 85, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A.; Pohl, K. Software product line engineering and variability management: achievements and challenges. Proceedings of the on Future of Software Engineering, FOSE 2014, Hyderabad, India, May 31 - June 7, 2014; Herbsleb, J.D.; Dwyer, M.B., Eds. ACM, 2014, pp. 70–84. 31 May. [CrossRef]

- Kent, S. Model Driven Engineering. Integrated Formal Methods, Third International Conference, IFM 2002, Turku, Finland, May 15-18, 2002, Proceedings; Butler, M.J.; Petre, L.; Sere, K., Eds. Springer, 2002, Vol. 2335, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 286–298. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Wasowski, A.; Berger, T. Domain-Specific Languages - Effective Modeling, Automation, and Reuse; Springer, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kosar, T.; Bohra, S.; Mernik, M. Domain-Specific Languages: A Systematic Mapping Study. Information & Software Technology 2016, 71, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblebici, O.; Kardas, G.; Tuglular, T. A Domain-Specific Language for the Document-Based Model-Driven Engineering of Business Applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 104093–104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparelia, N.B. Software development lifecycle models. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2010, 35, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C.; Runeson, P.; Höst, M.; Ohlsson, M.C.; Regnell, B. Experimentation in Software Engineering; Springer, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Challenger, M.; Kardas, G. Applications of model-driven engineering in cyber-physical systems: A systematic mapping study. J. Comput. Lang. 2020, 59, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Ozkaya, M.; Kardas, G. Modeling Languages for Internet of Things (IoT) Applications: A Comparative Analysis Study. Mathematics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gea, J.M.C.; Ebert, C.; Hosni, M.; Vizcaíno, A.; Nicolás, J.; Alemán, J.L.F. Requirements Engineering Tools: An Evaluation. IEEE Softw. 2021, 38, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, S.; Kamalrudin, M.; Sidek, S. A review on tool supports for security requirements engineering. 2013 IEEE Conference on Open Systems (ICOS). IEEE, 2013, pp. 190–194. [CrossRef]

- de Gea, J.M.C.; Nicolás, J.; Alemán, J.L.F.; Álvarez, J.A.T.; Ebert, C.; Vizcaíno, A. Requirements Engineering Tools. IEEE Softw. 2011, 28, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gea, J.M.C.; Nicolás, J.; Alemán, J.L.F.; Toval, A.; Ebert, C.; Vizcaíno, A. Requirements engineering tools: Capabilities, survey and assessment. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 1142–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Alasow, M.A.; Sajjad, F.; Baig, J.J.A. An evaluation of software requirements tools. 2017 Eighth International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 278–283. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Ibrahim, S.; Mahrin, M.N. An Evaluation of Requirements Management and Traceability Tools. International Journal of Computer and Information Engineering 2011, 5, 627–632. [Google Scholar]

- Sud, R.R.; Arthur, J.D. Requirements management tools: A quantitative assessment. Technical Report TR-03-10, Department of Computer Science, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, 2003.

- Nadeem, M.A.; Lee, S.U.J.; Younus, M.U. A Comparison of Recent Requirements Gathering and Management Tools in Requirements Engineering for IoT-Enabled Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam-Ul-Haq.; Abbas, W.; Butt, W.H. Systematic Literature Review on Requirement Management Tools. 2022 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Smart Technologies (ICETST). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Agner, L.T.W.; Lethbridge, T.C.; Soares, I.W. Student experience with software modeling tools. Softw. Syst. Model. 2019, 18, 3025–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Name | URL | Access Date |

|---|---|---|

| List of requirements engineering tools |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ List_of_requirements_engineering_tools |

09.04.2023 |

| 7 Requirements engineering tools to make your life easy |

https://www.zumvie.com/7-requirements- engineering-tools-to-make-your-life-easy/ |

09.04.2023 |

| 10 Best Requirements Management Tools & Software Of 2023 |

https://thedigitalprojectmanager.com/tools/ requirements-management-tools/ |

09.04.2023 |

| Top 20+ Best Requirements Management Tools |

https://www.softwaretestinghelp.com/ requirements-management-tools/ |

09.04.2023 |

| 13 BEST Requirements Management Tools & Software (2023) |

https://www.guru99.com/ requirement-management-tools.html |

09.04.2023 |

| Software Requirements Engineering Tools |

https://ecomputernotes.com/software-engineering/ softwarerequirementsengineeringtools |

09.04.2023 |

| Top Requirements Management Tools List |

https://blog.testlodge.com/ requirements-management-tools-list/ |

09.04.2023 |

| Tool | Web-site | Supported platforms |

Open- source |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accompa PM | www.web.accompa.com | Web | No | 2007 |

| acunote | www.acunote.com/ | Web | No | 2006 |

| Agile Requirements Designer |

www.broadcom.com/products/software/ continuous-testing/agile-requirements-designer |

Web and On-premise | No | 1960s |

| agosense.fidelia | www.agosense.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2009 |

| Aha! | www.aha.io/ | Web | No | 2013 |

| Aligned Elements | www.aligned.ch/features/requirement-management | Web and On-premise | No | 2006 |

| Quality Center - Dimensions RM |

www.microfocus.com/en-us/products/ dimensions-rm/overview |

Web | No | 1976 |

| Auros IQ | www.aurosks.com/ | Web | No | 2001 |

| Axosoft | www.axosoft.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2014 |

| Azure DevOps | www.azure.microsoft.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2005 |

| Balsamiq Wireframes | www.balsamiq.com/ | Web and On-premise | Yes | 2008 |

| Business Optix | www.businessoptix.com/ | Web | No | 2010 |

| Cameo Systems Modeler |

www.3ds.com/products-services/catia/ products/no-magic/cameo-systems-modeler/ |

Web and On-premise | No | 1998 |

| Capella | www.eclipse.org/capella/ | On-premise | Yes | 2001 |

| CaseComplete | www.casecomplete.com/ | Web | No | 2012 |

| ClickUp | www.clickup.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2017 |

| CodeBeamer ALM | www.codebeamer.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1998 |

| Cradle | www.threesl.com/cradle/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1987 |

| Doc Sheets | www.docsheets.com | Web and On-premise | No | 2000 |

| Eclipse Papyrus | www.eclipse.org/papyrus | On-premise | Yes | 2019 |

| Enterprise Architect | www.sparxsystems.com/ | On-premise | No | 2000 |

| Helix RM | www.perforce.com/products/helix-alm | Web and On-premise | No | 1995 |

| innoslate | www.innoslate.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1993 |

| Innovator for Business Analysts |

www.innovator.de/en/ | On-premise | No | 1986 |

| in-STEP BLUE | www.microtool.de/en/products/in-step-blue/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1997 |

| iRise | www.irise.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2016 |

| Jama Connect | www.go.jamasoftware.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2007 |

| Kovair ALM | www.kovair.com | Web | No | 2006 |

| MagicDraw |

www.3ds.com/products-services/catia/products/ no-magic/magicdraw/ |

On-premise | No | 1981 |

| Matrix ALM/QMS | www.matrixreq.com/en/product | Web | No | 2013 |

| Modelio Analyst | www.modeliosoft.com/en/modules/analyst.html | Web and On-premise | No | 2009 |

| OpenProject | www.openproject.org/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2012 |

| Orcanos | www.orcanos.com | Web and On-premise | No | 2004 |

| PivotalTracker | www.pivotaltracker.com/ | Web | No | 2006 |

| Polarion Requirements |

www.polarion.plm.automation.siemens.com/ products/polarion-requirements |

Web | No | 2004 |

| Psoda | www.psoda.com/ | Web | No | 2006 |

| Rational DOORS | www.ibm.com/docs/en/ermd/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1993 |

| Rational Rhapsody | www.ibm.com/products/uml-tools | On-premise | No | 2011 |

| ReqEdit | www.reqteam.com/ | On-premise | No | 2014 |

| ReQtest | www.reqtest.com/ | Web | No | 2009 |

| ReqView | www.reqview.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2015 |

| RMsis |

www.marketplace.atlassian.com/apps/30899/ rmsis-requirements-management-for-jira |

Web | No | 2009 |

| ReqChecker | https://reqchecker.eu/ | On-premise | No | 2016 |

| RMTrack | www.rmtrack.com/ | Web | No | 2001 |

| Scrumwise | www.scrumwise.com/ | Web | No | 2009 |

| SpiraTeam | www.inflectra.com/SpiraTeam/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2006 |

| StoriesOnBoard | https://storiesonboard.com/ | Web | No | 2015 |

| SwiftKanban | www.nimblework.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 1998 |

| Targetprocess | www.targetprocess.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2006 |

| TopTeam | www.topteamrequirements.com | Web and On-premise | No | 1995 |

| Tuleap Enterprise | www.tuleap.org | Web and On-premise | No | 2011 |

| Valispace | www.docs.valispace.com/ | Web and On-premise | No | 2016 |

| Visual Paradigm | www.visual-paradigm.com | Web and On-premise | No | 2002 |

| Visure Requirements | www.visuresolutions.com/ | Web | No | 2002 |

| Yodiz | www.yodiz.com | Web | No | 2009 |

| Xebrio | www.xebrio.com | Web and On-premise | No | 2018 |

| Requirements Engineering Tools | Multi-user Access | User Roles | User-access Rights |

|---|---|---|---|

| acunote | Yes | No | Yes |

| agosense.fidelia | Yes | No | No |

| Balsamiq Wireframes | Yes | No | No |

| Business Optix | Yes | No | No |

| CaseComplete | Yes | No | No |

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | Yes | No | Yes |

| Psoda | Yes | Yes | No |

| ReqView | Yes | No | No |

| Valispace | Yes | No | Yes |

| Orcanos | Yes | No | No |

| Xebrio | Yes | No | Yes |

| Requirements Engineering Tools | Built-in Versioning | GIT | SVN | Mercurial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acunote | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| agosense.fidelia | No | Yes | No | No |

| Aligned Elements | Yes | No | No | No |

| Auros IQ | Yes | No | No | No |

| Axosoft | No | Yes | No | No |

| Azure DevOps | No | Yes | No | No |

| Balsamiq Wireframes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Business Optix | Yes | No | No | No |

| Cameo Systems Modeler | Yes | No | No | No |

| Capella | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| CaseComplete | No | No | Yes | No |

| codeBeamer ALM | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cradle | Yes | No | No | No |

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Enterprise Architect | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Helix RM | Yes | No | No | No |

| innoslate | Yes | No | No | No |

| Innovator for Business Analysts | Yes | No | No | No |

| in-STEP BLUE | Yes | No | No | No |

| iRise | Yes | No | No | No |

| Jama Connect | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kovair ALM | Yes | No | No | No |

| MagicDraw | Yes | No | No | No |

| Matrix ALM/QMS | Yes | No | No | No |

| Modelio Analyst | Yes | No | No | No |

| OpenProject | Yes | No | No | No |

| PivotalTracker | Yes | No | No | No |

| Polarion Requirements | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Quality Center - Dimensions RM | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rational DOORS | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rational Rhapsody | Yes | No | No | No |

| ReqChecker | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| ReqEdit | Yes | No | No | No |

| ReQtest | Yes | No | No | No |

| ReqView | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| RMsis | Yes | No | No | No |

| SpiraTeam | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| StoriesOnBoard | No | Yes | No | No |

| SwiftKanban | No | Yes | No | No |

| Targetprocess | No | Yes | No | No |

| Tuleap Enterprise | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Valispace | Yes | No | No | No |

| Visual Paradigm | Yes | No | No | No |

| Visure Requirements | Yes | No | No | No |

| Yodiz | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Accompa | Yes | No | No | No |

| CA Agile Requirements Designer | Yes | No | No | No |

| ClickUp | No | Yes | No | No |

| Doc Sheets | Yes | No | No | No |

| Orcanos | Yes | No | No | No |

| TopTeam | Yes | No | No | No |

| Xebrio | Yes | No | No | No |

| Requirements Engineering Tools | Modeling Languages |

|---|---|

| Business Optix | BPMN |

| Cameo Systems Modeler | SysML |

| Capella | SysML |

| CaseComplete | UML |

| Cradle | SysML |

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | UML, SySML |

| Rational Rhapsody | UML, SySML |

| innoslate | LML, SysML |

| Innovator for Business Analysts | ArchiMate, BPMN, SysML |

| in-STEP BLUE | UML, SySML, and natural languages |

| MagicDraw | UML, SysML, BPMN, OWL, OCL, MARTE, SOAML |

| Visual Paradigm | UML, BPMN, ArchiMate, DFD, ERD, SoaML, SysML, CMMN |

| CA Agile Requirements Designer | Flowchart |

| TopTeam | UML, SysML, BPMN |

| Requirements Engineering Tools |

Pre-defined properties |

User-defined properties |

Simu- lation |

Consis- tency |

Comple- teness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| agosense.fidelia | X | ||||

| Auros IQ | X | X | |||

| Business Optix | X | X | |||

| Cameo Systems Modeler | X | X | X | X | X |

| Capella | X | X | X | X | |

| Cradle | X | X | X | X | |

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | X | ||||

| Enterprise Architect | X | X | X | ||

| Rational DOORS | X | ||||

| Rational Rhapsody | X | X | X | ||

| innoslate | X | X | X | X | |

| Innovator for Business Analysts | X | ||||

| MagicDraw | X | X | X | X | |

| ReqEdit | X | ||||

| ReqView | X | ||||

| SwiftKanban | X | ||||

| Valispace | X | X | |||

| Visual Paradigm | X | ||||

| Visure Requirements | X | X | |||

| ReqChecker | X | X | X |

| Requirements Engineering Tools |

Code Generation |

Test Scenario Generation |

Document Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aligned Elements | X | ||

| Quality Center-Dimensions RM | X | ||

| Auros IQ | X | ||

| Axosoft | X | ||

| Azure DevOps | X | ||

| Cameo Systems Modeler | X | ||

| Capella | X | ||

| CaseComplete | X | ||

| codeBeamer ALM | X | ||

| Cradle | X | ||

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | X | X | |

| Enterprise Architect | X | X | |

| Helix RM | X | ||

| Rational DOORS | X | ||

| innoslate | X | ||

| in-STEP BLUE | X | ||

| iRise | X | ||

| Kovair ALM | X | ||

| MagicDraw | X | X | |

| Matrix ALM/QMS | X | ||

| Modelio Analyst | X | X | |

| OpenProject | X | ||

| Polarion Requirements | X | ||

| Psoda | X | ||

| ReqEdit | X | ||

| ReQtest | X | ||

| ReqView | X | ||

| RMsis | X | X | |

| SpiraTeam | X | X | |

| Tuleap Enterprise | X | ||

| Valispace | X | ||

| Visual Paradigm | X | X | |

| Visure Requirements | X | ||

| Yodiz | X | ||

| Accompa PM | X | ||

| CA Agile Requirements Designer | X | X | |

| Doc Sheets | X | ||

| Orcanos | X | ||

| TopTeam | X | X | |

| Xebrio | X | ||

| ReqChecker | X | ||

| StoriesOnBoard | X |

| Requirements Engineering Tools |

Model-driven Engineering | Agile Software Development |

Product-line Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| acunote | No | Yes | No |

| agosense.fidelia | No | Yes | No |

| Aha! | No | Yes | No |

| Quality Center - Dimensions RM | Model-driven testing | Yes | No |

| Auros IQ | No | Yes | No |

| Axosoft | No | Yes | No |

| Azure DevOps | No | Yes | No |

| Business Optix | Model specification and simulation | Yes | No |

| Cameo Systems Modeler | Model specification and validation | No | Yes |

| Capella | Model specification and validation | No | No |

| CaseComplete | Model specification | No | No |

| codeBeamer ALM | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cradle | Model specification and validation | Yes | No |

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | Model specification and simulation | No | No |

| Enterprise Architect | Model specification, validation, and transformation |

Yes | No |

| Rational Rhapsody | Model specification, validation, simulation, and transformation |

No | No |

| innoslate | Model specification and simulation |

No | No |

| Innovator for Business Analysts | Model specification | No | No |

| iRise | Model specification | Yes | No |

| Kovair ALM | Model specification | Yes | No |

| MagicDraw | Model specification, validation, and transformation |

No | Yes |

| Modelio Analyst | Model specification, validation, and transformation |

No | No |

| OpenProject | No | Yes | No |

| PivotalTracker | No | Yes | No |

| Psoda | No | Yes | No |

| ReQtest | No | Yes | No |

| RMsis | No | Yes | No |

| Scrumwise | No | Yes | No |

| SpiraTeam | No | Yes | No |

| SwiftKanban | No | Yes | No |

| Targetprocess | No | Yes | No |

| Tuleap Enterprise | No | Yes | No |

| Visual Paradigm | Model specification, validation, simulation and transformation |

Yes | No |

| Visure Requirements | No | Yes | No |

| Yodiz | No | Yes | No |

| Accompa PM | No | Yes | No |

| CA Agile Requirements Designer | Model-driven testing | No | No |

| ClickUp | No | Yes | No |

| Doc Sheets | No | Yes | No |

| TopTeam | Model-driven testing | No | No |

| Requirements Engineering Tools |

Tel. | E- |

Fo- rum |

Live- chat |

Help Desk |

Guide | Blog | White paper |

M. List |

Case- study |

Videos | Trai- ning |

Coac- hing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acunote | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| agosense.fidelia | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Aha! | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Aligned Elements | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Quality Center - Dimensions RM |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Auros IQ | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Axosoft | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Azure DevOps | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Balsamiq Wireframes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Business Optix | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cameo Systems Modeler |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Capella | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| CaseComplete | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| codeBeamer ALM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cradle | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Eclipse (IDE) Papyrus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Enterprise Architect | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Helix RM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rational DOORS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Rational Rhapsody | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| innoslate | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Innovator for Business Analysts |

X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| in-STEP BLUE | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| iRise | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Jama Connect | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Kovair ALM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| MagicDraw | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Matrix ALM/QMS | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Modelio Analyst | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| OpenProject | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| PivotalTracker | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Polarion Requirements | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Psoda | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| ReqEdit | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| ReQtest | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| ReqView | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| RMsis | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| RMTrak | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Scrumwise | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| SpiraTeam | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| SwiftKanban | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Targetprocess | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Tuleap Enterprise | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Valispace | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Visual Paradigm | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Visure Requirements | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Yodiz | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Accompa | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| CA Agile Requirements Designer |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ClickUp | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Doc Sheets | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Orcanos | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| TopTeam | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Xebrio | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| ReqChecker | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| StoriesOnBoard | X | X | X | X | X |

| Study | Year | Number of tools | Number of features |

|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | 2021 | 13 | 17 |

| [37] | 2013 | 7 | 9 |

| [38,39] | 2012 | 38 | 23 |

| [13] | 2019 | 58 | 9 |

| [40] | 2017 | 21 | 8 |

| [41] | 2011 | 13 | 9 |

| [42] | 2003 | 12 | 13 |

| [43] | 2022 | 10 | 10 |

| [44] | 2022 | 8 | 7 |

| [45] | 2019 | 31 | Student Survey |

| Our Study | 2023 | 56 | 20 |

| Study | Project Man. |

Speci- fication |

Colla- boration |

Custom- isation |

Inter- operability |

Metho- dology |

Knowledge Man. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [37] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| [38,39] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| [40] | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| [41] | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| [42] | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| [43] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| [44] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| [45] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Our Study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).