Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Carboxylated Graphene Oxide

2.3. Nano Carboxylated Graphene Oxide (nCGO) Particles

2.4. Paclitaxel Loading and Release from nCGO-PEG Particles

2.5. Cellular Evaluation of the nCGO/PEG Particles

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

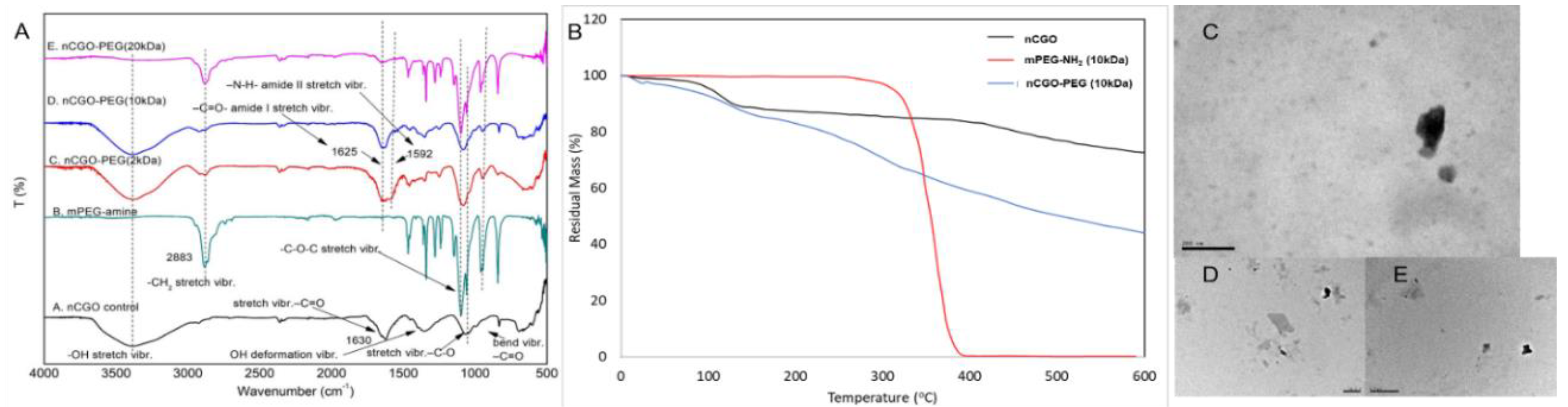

3.1. Characterization

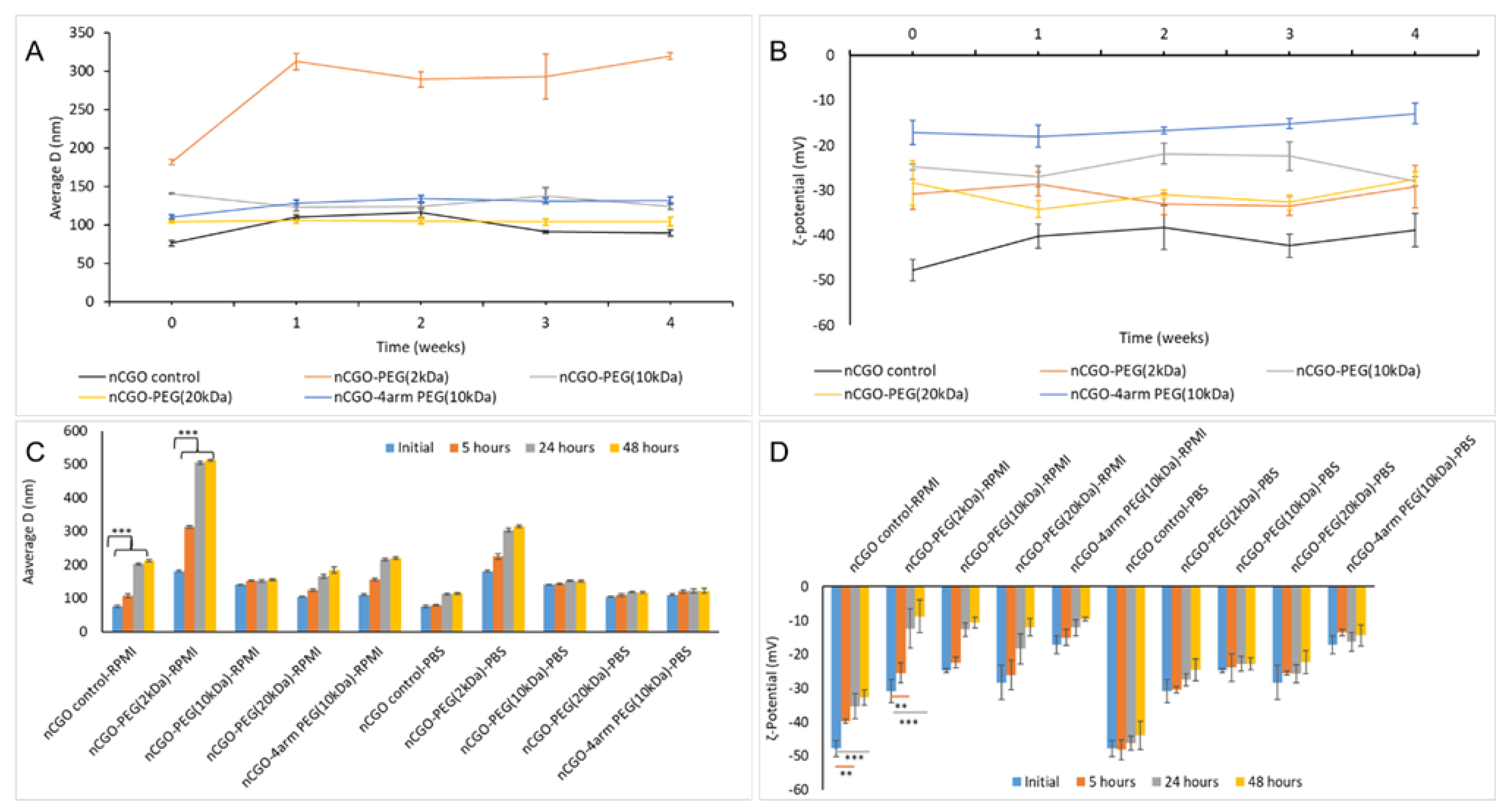

3.2. Colloidal Stability of nCGO-PEG

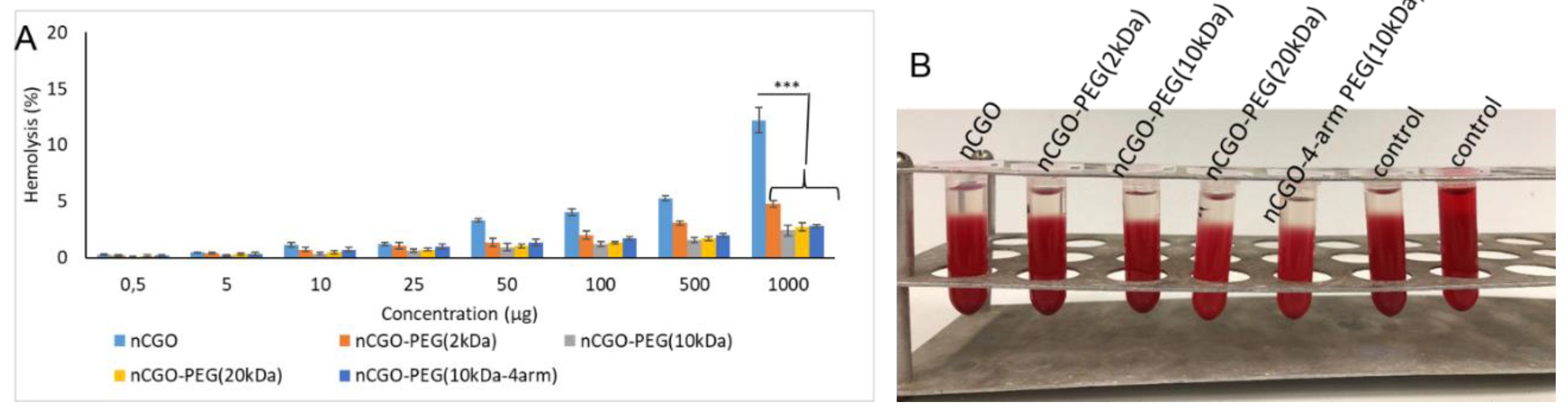

3.3. Hemolysis Assay Results

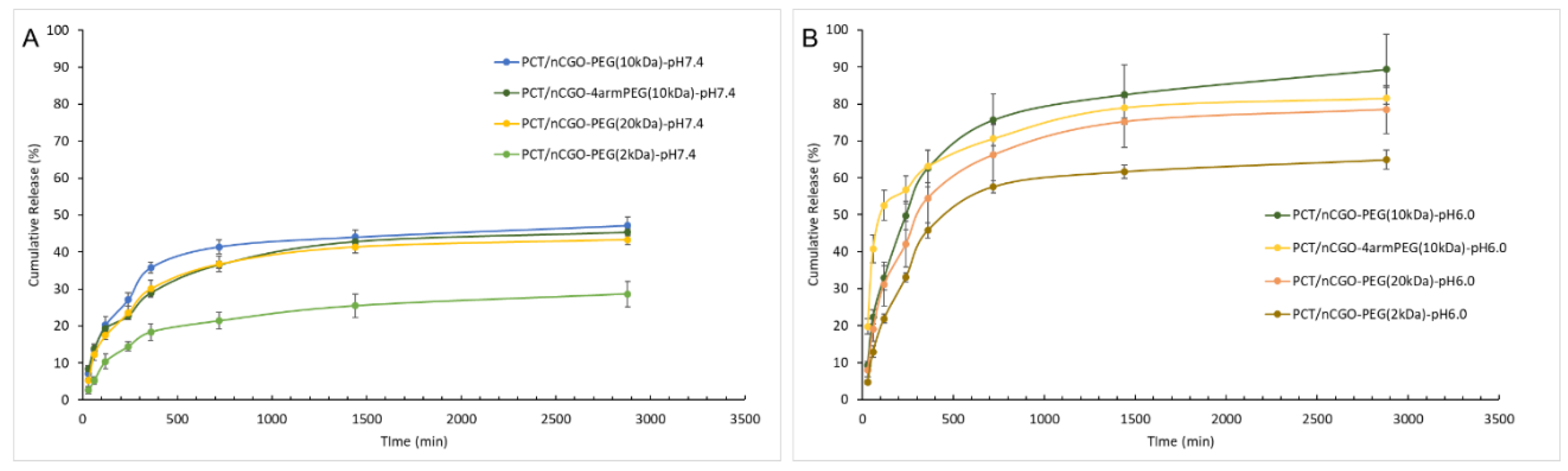

3.4. Loading and Release Profiles from nCGO-PEG/PCT Particles

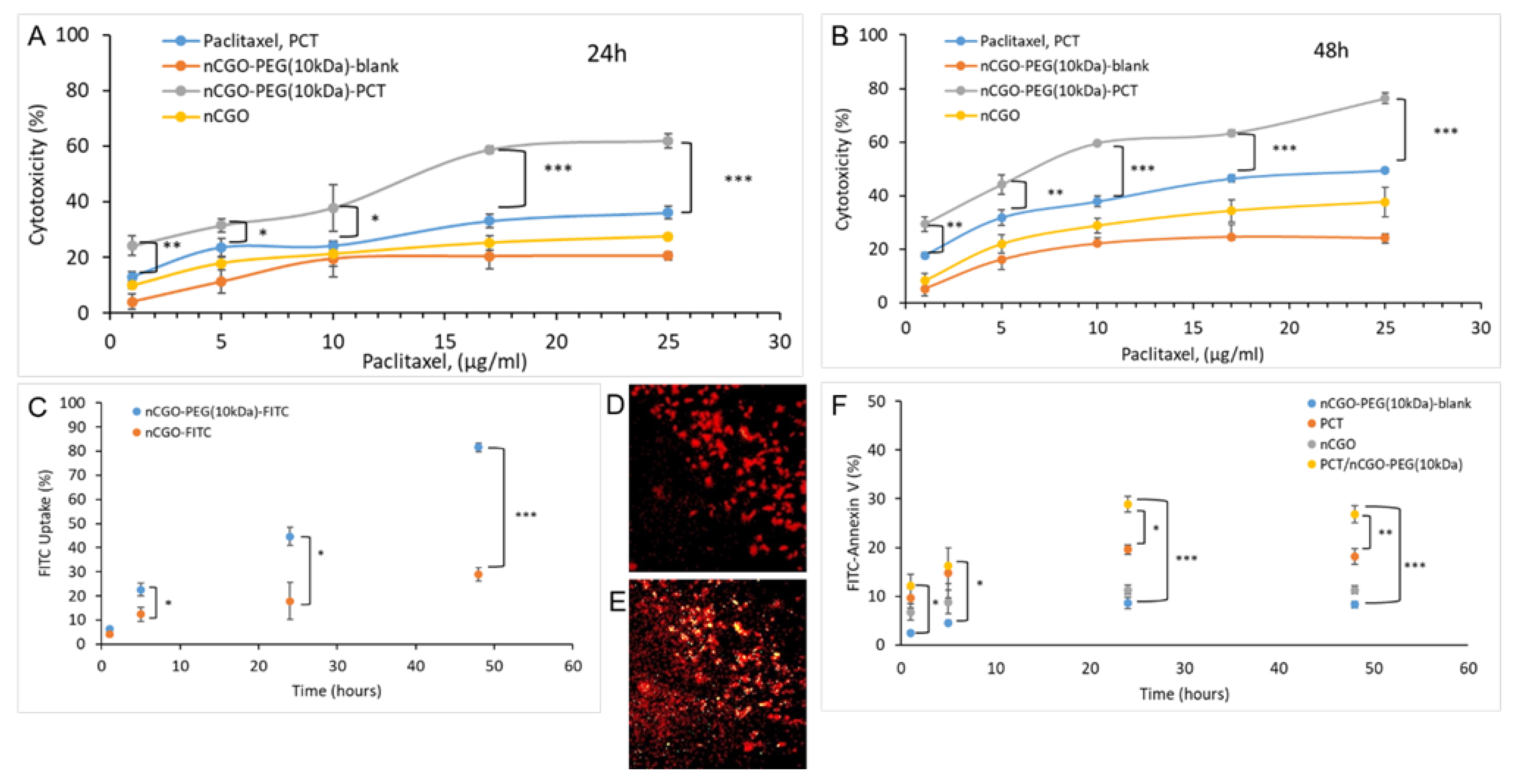

3.5. Results from the Cell Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shafiee, A.; Iravani, S.; Varna, R.S. Graphene and graphene oxide with anticancer applications: Challenges and future perspectives. MedComm. 2022, 3, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Itoo, A.; Lakshmi Vemula, S.; Tejasvni Gupta, M.; Vilasrao Giram, M.; Akhil Kumar, S.; Ghosh, B.; Biswas. S. Multifunctional graphene oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. J. Contr. Rel. 2022, 350, 26. [CrossRef]

- de Melo-Diogo, D.; Lita-Sousa, R.; Alves, C.G.; Costa, E.C.; Louro, R.O.; Correia. I.J. Functionalization of graphene family nanomaterials for application in cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018, 171, 260. [CrossRef]

- Alemi, F.; Zarezadeh, R.; Raei Sadigh, A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Rahimi, M.; Majidinia, M.; Asemi, Z.; Ebrahimi-Kalan, A.; Yousefi, B.; Rashtchizadeh. N. Graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide: Efficient cargo platforms for cancer theranostics. J. Drug Deliev. Sci. & Techn. 2020, 60, 101974. [CrossRef]

- de Melo-Diogo, D.; Lita-Sousa, R.; Alves, C.G.; Correia, I.J. Graphene family nanomaterials for application in cancer combination photothermal therapy. Biomater. Sci., 2019, 7, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Sun, X.; Lee, S.-T.; Liu, Z. Graphene in mice: ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett., 2010, 10, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, T.; Yang, G.; Liu, Z. Surface coating-dependent cytotoxicity and degradation of graphene derivatives: towards the design of Non-toxic, degradable nano-graphene. Small, 2014, 10, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, K.; Feng, L.; Liu, Z. In vitro and in vivo behaviors of dextran functionalized graphene. Carbon, 2011, 49, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, S.; Nie, S.; Zhao, W.; Yang, H.; Sun, S.; Zhao, C. General and biomimetic approach to biopolymer-functionalized graphene oxide nanosheet through adhesive dopamine. Biomacromolecules, 2012, 13, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.K.; Choi, M.-C.; Kong, J.-Y.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.-H.; Mishra, S.; Singh, R.P.; Ha, C.-S. Synthesis and drug-delivery behavior of chitosan-functionalized graphene oxide hybrid nanosheets. Macromol. Mater. Eng., 2011, 296, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhu, J.; Wang, F.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Weng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Liu, S. Improved in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of graphene oxide through surface modification: poly(acrylic acid)-functionalization is superior to PEGylation. ACS Nano, 2016, 10, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wan, J.; Zhang, S.; Tian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. The influence of surface chemistry and size of nanoscale graphene oxide on photothermal therapy of cancer using ultra-low laser power. Biomaterials, 2012, 33, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Voulgari, E.; Diamanti, E.K.; Gournis, D.; Avgoustakis, K. Graphene oxide stabilized by PLA–PEG copolymers for the controlled delivery of paclitaxel. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibolandi, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Abnous, K. Fabrication of aptamer decorated dextran coated nano-graphene oxide for targeted drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym., 2017, 155, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.J.; Compton, O.C.; An, Z.; Eryazici, I.; Nguyen, S.T. Successful stabilization of graphene oxide in electrolyte solutions: enhancement of biofunctionalization and cellular uptake. ACS Nano, 2012, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo-Diogo, D.; Pais-Silva, C.; Costa, E.C.; Louro, R.O.; Correia, I.J. D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate functionalized nanographene oxide for cancer therapy. Nanomedicine, 2017, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, X.; Duan, A.; Gao, R.; Liu, J;. Li, B. Graphene oxide loaded with tumor-targeted peptide and anti-cancer drugs for cancer target therapy. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 1725. [CrossRef]

- Vinothini, K.; Rajendran, N.K.; Ramu, A.; Elumalai, n.; Rajan, M. Folate receptor targeted delivery of paclitaxel to breast cancer cells via folic acid conjugated graphene oxide grafted methyl acrylate nanocarrier. Biomed. & Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadian, H.; Mohammad-Razaei, R.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Massoumi, B.; Abbasian, M.; Jafarizad, A.; Jaymand, M. A de novo theranostic nanomedicine composed of PEGylated graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles for cancer therapy. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, N.A.; Isiklan, N.; Turk, M. Aptamer-functionalized magnetic graphene oxide nanocarrier for targeted drug delivery of paclitaxel. Mater. Chem. Physic. 2018, 211, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, F.; Morteza Naghib, S.; Hosseini Motlagh, N.S.; Haghiralsadat, F.; Zarei Jaliani, H.; Moradi, A. Multiresponsive carboxylated graphene oxide grafted aptamer as a multifunctional nanocarrier for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics and bioactive compounds in cancer therapy. Nanotech. Rev. 2021, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrzejczak-Silicka, M.; urbas, K.; Mijowska, E.; Rakoczy, R. The covalent and non-covalent conjugation of graphene oxide with hydroxycamptothecin in hyperthermia for its anticancer activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 709, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Mondal, S. Functionalized Graphene Oxide for Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery and Cancer Treatment: A Promising Material in Nanomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y.; Chu, X.; Xie, J.; Zhou, N.; Shen, J. Biomedical application of graphene: From drug delivery, tumor therapy, to theranostics. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020, 185, 110596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Ding, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Qu, L.; Pei, H.; Yildirimer, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W. Graphene-based nanomaterials for drug and/or gene delivery, bioimaging, and tissue engineering. Drug Discov. Today. 2017, 22, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiryaghoubi, N.; Fathi, M.; Barzegari, A.; Barar, J.; Omidian, H.; Omidi, Y. Recent advances in polymeric scaffolds containing carbon nanotube and graphene oxide for cartilage and bone regeneration. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaweil, A.S.; Ahmed, M.S.; El-Subruiti, G.M.; Khalifa, R. E.; Omer, A. M. Efficient loading and delivery of ciprofloxacin by smart alginate/carboxylated graphene oxide/aminated chitosan composite microbeads: In vitro release and kinetic studies. Arab. J. Chem., 2023, 16, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Emadi, F.; Nazem, M.; Aghayi, R.; Khalvati, B.; Amini, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Expression of key apoptotic genes in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line treated with etoposide-loaded graphene oxide. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2020, 57, 101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, K.; Calvaresi, M.; Diamanti, E.K.; Tsoufis, T.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P.; Zerbetto, F. Graphite Oxide and Aromatic Amines: Size Matters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygouri, P.; Spyrou, K.; Papayannis, D.K.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Dounousi, E.; Stamatis, H.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P. Comparative Study of Various Graphene Oxide Structures as Efficient Drug Release Systems for Ibuprofen. Applied. Chem. 2022, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Aziz, H.; Ali, S.; Murtaza, G.; Rizwan, M.; Saleem, M.H.; Mahboob, S.; Al-Ghanim, K.A.; Riaz, M.N.; Murtaza, B. Synthesis of Functionalized Carboxylated Graphene Oxide for the Remediation of Pb and Cr Contaminated Water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Kolokithas-Ntoukas, A.; Papaioannou, L.; Kakazanis, Z.; Khoury, N.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Papatheodorou, S.; Kardamakis, D., Bakandritsos, A.; Hatziantoniou, S.; Avgoustakis. K. Canagliflozin-loaded magnetic nanoparticles as potential treatment of hypoxic tumors in combination with radiotherapy, Nanomedicine. 2018, 13, 1. [CrossRef]

- Georgitsopoulou, S.; Angelopoulou, A.; Papaioannou, L.; Georgakilas, V.; Avgoustakis, K. Self-assembled Janus graphene nanostructures with high camptothecin loading for increased cytotoxicity to cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 6, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fuan, J.; Wu, P.; Wei, C.; Chen, Q.; Ming, Z.; Yan, J.; Yang, L. Chronic chemotherapy with paclitaxel nanoparticles induced apoptosis in lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezel, M.; Ebrahimi, F.; Koch, M.; Dehghani, F. Propidium iodide staining: a new application in fluorescence microscopy for analysis of cytoarchitecture in adult and developing rodent brain, Micron. 2012, 43 1031. [CrossRef]

- Ambrozio, A.R.; Lopes, T.R.; Cipriano, D.F.; de Souza, F.A.L.; Scopel, W.L.; Freitas, J.C.C. Combined experimental and computational 1H NMR study of water adsorption onto graphenic materials. JMRO. 2023, 14, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichenkova, E.V.; Raju, A.P.A.; Burusco, K.K.; Kinloch, I.A.; Novoselov, K.S.; Clarke, D.J. NMR detects molecular interactions of graphene with aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons in water. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobin, M.; Huda; Shoeb, M.; Aslam, R.; Banerjee, P. Synthesis, characterisation and corrosion inhibition assessment of a novel ionic liquid-graphene oxide nanohybrid. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1262, 133027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depan, D.; Shah, J.; Misra, R.D.K. Controlled release of drug from folate-decorated and graphene mediated drug delivery system: Synthesis, loading efficiency, and drug release response. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2011, 31, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, S.; Touahir, L.; Salvador Andresa, J.; Allongue, P.; Chazalviel, J.-N.; Gouget-Laemmel, A.C.; de Villeneuve, C.H.; Moraillon, A.; Ozanam, F.; Gabouze, N.; Djebbar, S. Semiquantitative Study of the EDC/NHS Activation of Acid Terminal Groups at Modified Porous Silicon Surfaces, Langmuir. 2010, 26, 809. [CrossRef]

- Shariare, M.H.; Masum, A.-A.; Alshehri, S.; Alanazi, F.K.; Uddin, J.; Kazi, M. Preparation and Optimization of PEGylated Nano Graphene Oxide-Based Delivery System for Drugs with Different Molecular Structures Using Design of Experiment (DoE). Molecules. 2021, 26, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Farani, M.; Khadiv-Parsi, P.; Hossein Riazi, G.; Shafiee Ardestani, M.; Saligheh Rad, H. PEGylation of graphene/iron oxide nanocomposite: assessment of release of doxorubicin, magnetically targeted drug delivery and photothermal therapy. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenska, T.; Abrashev, M.; Georgieva, M.; Krasteva, N. Impact of Polyethylene Glycol Functionalization of Graphene Oxide on Anticoagulation and Haemolytic Properties of Human Blood. Materials 2021, 14, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, H.; Raissi, H. Understanding loading, diffusion and releasing of Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel dual delivery in graphene and graphene oxide carriers as highly efficient drug delivery systems. Applied Surf. Sci. 2020, 500, 144220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; He, L.; Wang, K.; Ma, B.; Ge, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ying, H. Combined Adsorption and Covalent Linking of Paclitaxel on Functionalized Nano-Graphene Oxide for Inhibiting Cancer Cells. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, P.; Huang, X. Covalent Functionalization of Graphene Oxide with Biocompatible Poly(ethylene glycol) for Delivery of Paclitaxel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014, 6, 19, 17268. [CrossRef]

- Khramtsov, P.; Bochkova, M.; Timganova, V.; Nechaev, A.; Uzhviyuk, S.; Shardina, K.; Maslennikova, I.; Rayev, M.; Zamorina, S. Interaction of Graphene Oxide Modified with Linear and Branched PEG with Monocytes Isolated from Human Blood. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Carballares, D.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Stabilization of enzymes via immobilization: Multipoint covalent attachment and other stabilization strategies. Biotech. Adv. 2021, 52, 107821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Ruan, J.; Wang, S. Biosynthesized of reduced graphene oxide nanosheets and its loading with paclitaxel for their anti-cancer effect for treatment of lung cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biology. 2019, 191, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, M.M. Fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated graphene oxide for detection of dopamine, Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, M.; Lopes, A.R.; Escudeiro, M.; Esteves, B.; Monteiro, A.R.; Trindade, T.; Cruz-Lopes, L. Application of Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment: A Concise Review. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Yang, K.; Hong, H.; Valdovinos, H.F.; Nayak, T.R.; Zhang, Y.; Theuer, C.P.; Barnhart, T.E.; Liu, Z.; Cai, W. Tumor vasculature targeting and imaging in living mice with reduced graphene oxide, Biomaterials. 2013, 34, 3002. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, Z.; Feng, X.; Shen, G.; Huang, H.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, G.; Hu, Y. Graphene oxide (GO)-based nanosheets with combined chemo/photothermal/ photodynamic therapy to overcome gastric cancer (GC) paclitaxel resistance by reducing mitochondria-derived adenosine-triphosphate (ATP). J Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. R.; Kim, D. W.; Jones, V. O.; Choi, Y.; Ferry, V. E.; Geller, M. A.; Azarin, S. M. Sonosensitizer-Functionalized Graphene Nanoribbons for Adhesion Blocking and Sonodynamic Ablation of Ovarian Cancer Spheroids. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2021, 10, 2001368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, D.; Yan, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Tang, X.; Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X. Evasion of the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon by branched PEG lipid derivative coating of nanoemulsions, Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 612, 121365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awel Hussien, N.; Işıklan, N.; Türk, M. Aptamer-functionalized magnetic graphene oxide nanocarrier for targeted drug delivery of paclitaxel, Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 211, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Yield (%) | CGO weight ratio (%) | PEG-NH2 weight ratio (%) | PCT Loading (%) | Average size (nm) | PdI | ζ-Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nCGO | 54.89 ± 6.85 | - | - | - | 76.10 ± 3.49 | 0.354 ± 0.036 | -47.82 ± 2.36 |

| CGO-PEG(2kDa)/PCT | 26.85 ± 0.90 | 23.31 | 76.69 | 67.64 ± 1.32 | 181.4 ± 3.40 | 0.431 ± 0.051 | -30.84 ± 3.36 |

| CGO-PEG(10kDa)/PCT | 14.63 ± 2.69 | 60.84 | 39.2 | 52.43 ± 2.38 | 140.5 ± 1.02 | 0.311 ± 0.089 | -24.78 ± 0.61 |

| CGO-PEG(20kDa)/PCT | 32.38 ± 0.85 | 20.40 | 79.6 | 38.88 ± 2.42 | 104.2 ± 1.16 | 0.276 ± 0.012 | -28.35 ± 5.04 |

| CGO-PEG(4arm 10kDa)/PCT | 23.61 ± 1.51 | 21.95 | 78 | 33.66 ± 1.74 | 110.3 ± 2.37 | 0.209 ± 0.023 | -17.14 ± 2.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).