Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Clinical History

2.3. Skin Tests

2.4. Limpet Extracts

2.5. Serological Analysis

2.6. SDS-PAGE and IgE Western Blot

2.7. Use of AI Assisted Tools

3. Results

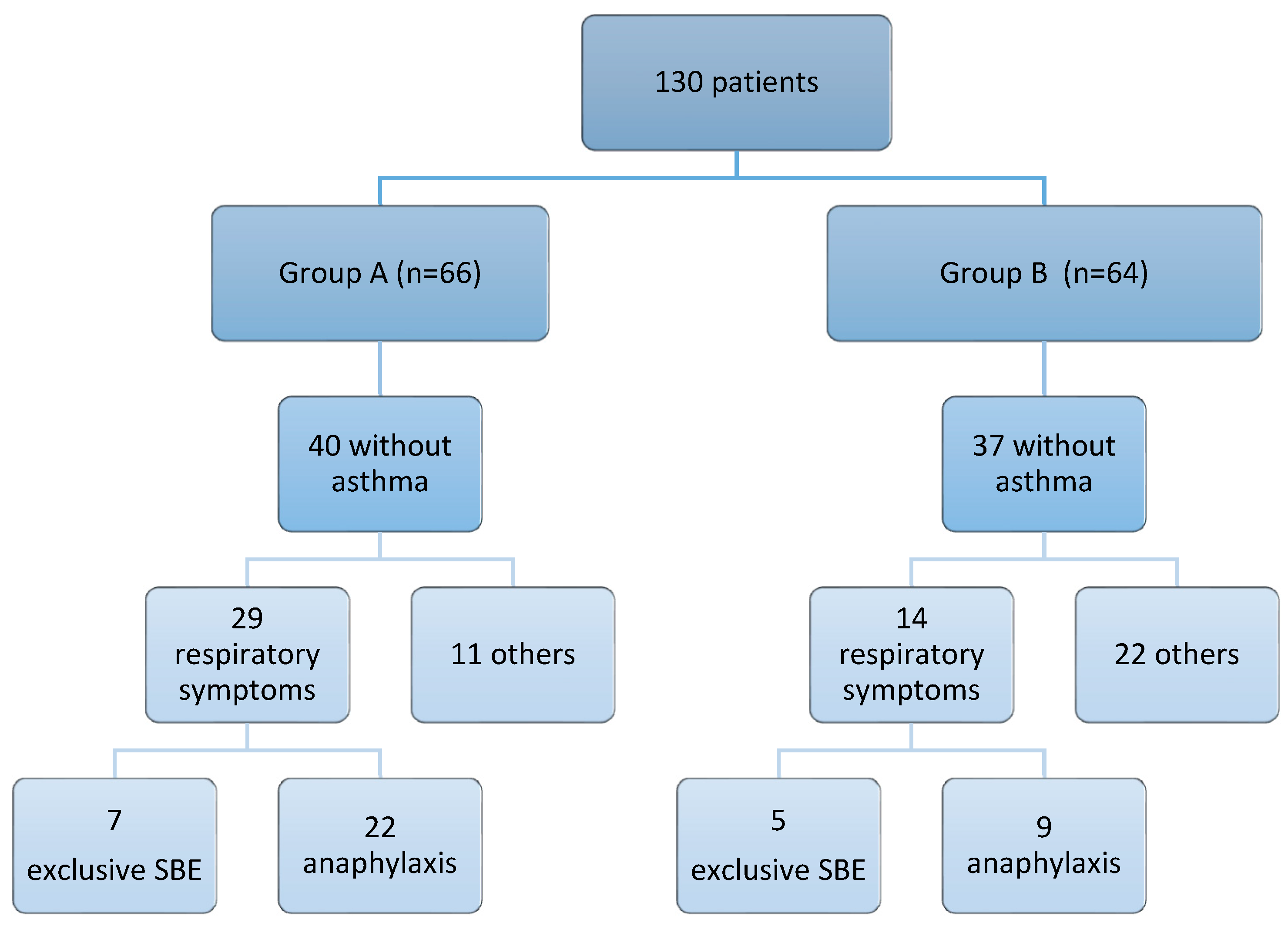

3.1. Classification of the Study Population

3.2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Investigated Patients

3.2.1. Personal History: Respiratory Disease

3.2.2. Food Allergy

3.3. Skin Tests, Total IgE and sIgE Reactivity

3.4. Molecular Profile According to Clinical Phenotypes

| Monosensitized selected patients |

Pen m 1 | Pen m 2 | Pen m 3 | Pen m 4 | Cra c 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 0.6 |

| 2 | 0.19 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 0.34 |

| 3 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 1.26 |

| 4 | 39.83 | <0.10 | 17.54 | 4.02 | >50 |

| 5 | 0.10 | 1.53 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 |

| 6 | 4.25 | <0.10 | <010 | <0.10 | 6.52 |

| n=6 | % | Number of molecules | Pen m 1 | Pen m 2 | Pen m 3 | Pen m 4 | Cra c 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 50 | 1 | * | |||||

| 1 | 16.7 | 1 | * | |||||

| 1 | 16.7 | 2 | * | * | ||||

| 1 | 16.7 | 4 | * | * | * | * |

| Patients group B | Pen m 1 | Pen m 2 | Pen m 3 | Pen m 4 | Cra c 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 4.03 | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | - | - | 0.13 | - | 0.67 |

| 4 | 0.67 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | 0.59 |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | 1.94 |

| 7 | 45.17 | - | - | - | 0.17 |

| 8 | 42.12 | - | 0.18 | - | 1.36 |

| 9 | 31.01 | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | 44.99 | 12,95 | 2,23 | - | - |

| 11 | 0.54 | 1.60 | - | - | 0.60 |

| 12 | 37.49 | - | - | - | 10.32 |

| 13 | - | - | - | - | 8.99 |

| 14 | 22.89 | - | - | 0.27 | - |

| 15 | 43.42 | - | - | - | 0.73 |

| 16 | 11.49 | 0.33 | - | - | 3.48 |

| 17 | 0.43 | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | 112 | 3.03 | - | - | - |

| 19 | - | - | - | 10.04 | - |

| 20 | - | 0.87 | - | - | - |

| 21 | 27.21 | - | - | - | 6.95 |

| 22 | 5.92 | - | - | - | - |

| 23 | - | 2.16 | - | - | - |

| 24 | 2.40 | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | 30.31 | - | 0,15 | - | 1.17 |

| 26 | 1.02 | - | - | - | - |

| 27 | 30.37 | - | - | - | - |

| 28 | - | - | - | - | 6.76 |

| 29 | - | 5.57 | - | - | 4.53 |

| 30 | 0.62 | - | - | - | - |

| 31 | 42.04 | - | - | - | 3.79 |

| 32 | 9.08 | 2.43 | - | - | 2.8 |

| 33 | 0.62 | 0.36 | - | - | - |

| 34 | 9.87 | - | - | - | 9.21 |

| 35 | - | 0.86 | - | - | - |

| 36 | 40 | 0.59 | - | - | 1.03 |

| n=36 | % | Number of molecules | Pen m 1 | Pen m 2 | Pen m 3 | Pen m 4 | Cra c 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 30.6 | 1 | * | |||||

| 4 | 11.1 | 1 | * | |||||

| 1 | 2.8 | 1 | * | |||||

| 5 | 13.9 | 1 | * | |||||

| 8 | 22.2 | 2 | * | * | ||||

| 2 | 5.6 | 2 | * | * | ||||

| 1 | 2.8 | 2 | * | * | ||||

| 1 | 2.8 | 3 | * | * | * | |||

| 3 | 8.3 | 3 | * | * | * |

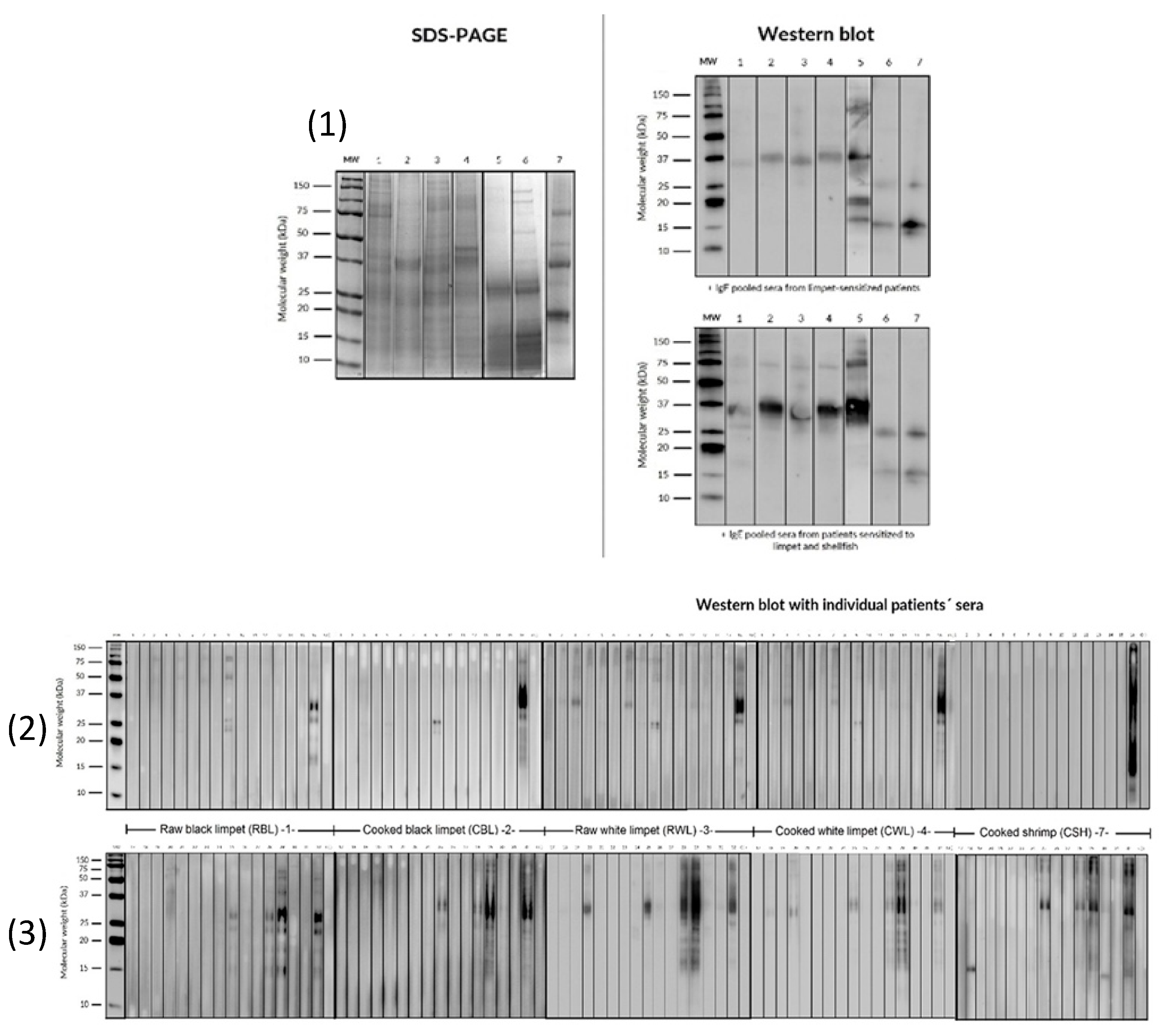

3.5. SDS PAGE and IgE Western Blot

4. Limitations

5. Discussion

6. Unmet Needs and Future Direction

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giovannini, M.; Beken, B.; Buyuktiryaki, B.; Barni, S.; Liccioli, G.; Sarti, L.; Lodi, L.; Pontone, M.; Bartha, I.; Mori, F.; et al. IgE-Mediated Shellfish Allergy in Children. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Cai, J.; Gao, T.; Ma, A. Shellfish consumption and health: a comprehensive review of human studies and recommendations for enhanced public policy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 4656–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khora, S.S. Seafood-Associated Shellfish Allergy: A Comprehensive Review. Immunol Invest. 2016, 45, 504–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.L. Molluscan Shellfish Allergy. Advances in food and nutrition research. 2008, 54, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.F.; Riggioni, C.; Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Álvarez-Perea, A.; Alvaro-Lozano, M.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; et al. EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgEmediated food allergy. Allergy First Published, 10 October. [CrossRef]

- Alergológica 2015, SEAIC. Available online: https://www.seaic.org/inicio/noticias-general/alergologica-2015.

- Mederos-Luis, E.; Poza-Guedes, P.; Pineda, F.; Sánchez-Machín, I.; González-Pérez, R. Gastropod Allergy: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5950–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, C.Y.; Leung, N.Y.; Leung, A.S.; Wong, G.W.; Leung, T.F. Seafood allergy in Asia: geographical specificity and beyond. Frontiers in Allergy 2021, 2, 676903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofra, J.; Echechipia, S.; Irazábal, B.; Muñoz, D.; Bernedo, N.; Gacía, B.E.; Gastaminza, G.; Goikoetxea, M.J.; Joral, A.; Lasa, E.; Gamboa, P.; Díaz, C.; Beristain, A.; Quiñones, D.; Bernaloa, G.; Echenagusia, M.A.; Liarte, I.; García, E.; Cuesta, J.; Martínez, M.D.; Velasco, M.; Longo, N.; Pastro-Vargas, C. Heterogenecity in allergy to mollusks: a clinicalimmunological study in a population from the north of Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2017, 27, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelis, S.; Rueda, M.; Valero, A.; Fernández, E.A.; Moran, M.; Fernández-Caldas, E. Shellfish allergy: unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2020, 30, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, R. Update on diagnosis and treatment of shellfish allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011, 11, 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, M.; Boyano-Martínez, T.; García-Ara, C.; Quirce, S. Shellfish Allergy: a comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015, 49, 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasi, S.; Nurmatov, U.; Dunn-Galvin, A.; Daher, S. ; Roberts, G.; Turner, P.J.; Shinder, S.B.; Gupta, R.; Eigenmann, P.; et al. Consensus on Definition of food allergy severity (DEFASE) an integrated mixed methods systematic review. World Allergy Organization Journal 2021, 14, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzerling, L.; Mari, A.; Bergmann, K.C.; Bresciani, M.; Burbach, G.; Darsow, U.; Durham, S.; Fokkens, W.; Gjomarkaj, M.; Haahtela, T.; et al. The skin prick test-European standards. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2013, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojcukova, J.; Vlas, T.; Forstenlechner, P.; Panzner, P. Comparison of two multiplex arrays in the diagnostics of allergy. Clin. Transl Allergy 2019, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, K.; Bartuzi, Z. Selected Technical Aspects of Molecular Allergy Diagnostics. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023, 45, 5481–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the Assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, R.; Poza-Guedes, P.; Pineda, F.; Galán, T.; Mederos-Luis, E.; Abel-Fernández, E.; Martínez, M.J.; Sánchez-Machín, I. Molecular Mapping of allergen exposome among different atopic phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, T.; De Castro, F.R.; Cuevas, M.; Caminero, J.; Cabrera, P. Allergy to limpet. Allergy 1991, 46, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, T.; Rodríguez de Castro, F.; Blanco, C.; Castillo, R.; Quiralte, J.; Cuevas, M. Anaphylaxis due to limpet ingestión. Ann Allergy 1994, 73, 504–8. [Google Scholar]

- Azofra, J.; Lombardero, M. Limpet Anaphylaxis: cross-reactivity between limpet and house-dust mite Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Allergy 2003, 58, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Fernández, D.; Fuentes-Vallejo, M.S.; Bartolomé-Zavala, B.; Foncubierta-Fernández, A.; Lucas-Velarde, J.; León-Jiménez, A. Urticaria-angioedema due to limpet ingestión. J Allergol Clin Immunol 2009, 19, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mederos-Luis, E.; Poza-Guedes, P.; Martínez, M.J.; González-Pérez, R.; Galán, T.; Sánchez-Machín, I. Limpet molecular profile: tropomyosin or not tropomyosin, that is the question. Thematic poster session (TPS). Allergy 2023, 78, 283–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Martins, L.M.; Peltre, G.; Fialho da Costa-Faro, C.J.; Vieira-Pires, E.M.; Da Cruz-Inacio, F.F. The Helix aspersa (brown garden snail) allergens repertoire. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2005, 136, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopata, A.L.; Zinn, C.; Potter, P.C. Characteristics of hypersensitivity reactions and identification of a unique 49 kd IgE-binding protein (Hal-m-1) in abalone (Haliotis midae). J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997, 100, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.H.; Mirakhur, B.; Chan, E.; Le, Q.-T.; Berlin, J.; Morse, M.; Murphy, B.A.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mauro, D.; et al. Cetuximab induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-a-1,3-galactose. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mozena, J.; Borish, L.; Lewis, B.; Woodfolk, J.A.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-a-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homann, A.; Schramm, G.; Jappe, U. Glycans andglycan-specific IgE in clinical and molecular allergology: Sensitization, diagnostics and clinical symptoms. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ree, R.; Antonicelli, L.; Akkerdaas, J.H.; Pajno, G.B.; Barberio, G.; Corbetta, L.; Ferro, G.; Zambito, M.; Garritani, M.S.; Aalberse, R.C.; Bonifazi, F. Asthma after consumption of snails in house-dust-mite-allergic patients: a case of IgE cross-reactivity. Allergy 1996, 51, 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, C.; Bartolome, B.; Rodríguez, V.; Armisén, M.; Linneberg, A.; González-Quintela, A. Sensitization pattern of crustacea-allergic individuals can indicate allergy to mollusks. Allergy 2015, 70, 1493–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misnan, R.; Abd Aziz, N.S.; Yadzir, Z.H.M.; Bakhtiar, F.; Abdullah, N.; Murad, S. Impact of thermal treatments on major and minor allergens of sea snail, Cerithidea obtuse (obtuse horn shell). Ira J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 15, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Klaewsongkram. High prevalence of shellfish and house dust mite allergies in Asia-Pacific: probably not just a coincidence. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2012, 30, 247–248. [Google Scholar]

- Guilloux, L.; Vuitton, D.A.; Delbourg, M.; et al. Cross-reactivity between terrestial snails (Helix species) and house-dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus). II. In vitro study. Allergy 1998, 53, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Prados-Castaño, M.; Cimbollek, S.; Bartolomé, B.; Castillo, M.; Quiralte, J. Snailinduced anaphylaxis in patients with underlying Artemisia vulgaris pollinosis: the role of carbohydrates. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2024, 52, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Matas, M.A.; de Larramendi, C.H.; Moya, R.; Sánchez-Guerrero, I.; Ferrer, A.; Huertas, A.J.; Flores, I.; Navarro, L.A.; García-Abujeta, J.L.; Vicario, S.; Andreu, C.; Peña, M.; Carnés, J. In vivo diagnosis with purified tropomyosin in mite and shellfish allergic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016, 116, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hiraki, Y.; et al. Paramyosin of the disc abalone Haliotis discus discos: identification as a new allergen and cross-reactivity with tropomyosin. Food Chemestry 2011, 124, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group A (n=66) | Group B (n=64) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (% Female) | 57.6 | 48.4 |

| Median age [range] | 27 y.o. [10–53] | 25.23 y.o. [4–62] |

| Personal History | ||

| RC (%) | 92.5 | 84.4 |

| Asthma (%) | 39.4 | 42.2 |

| Clinical Manifestation | ||

| Anaphylaxis (%) | 66.7 | 41.2 |

| Exclusive severe asthma (%) | 21.2 | 38.2 |

| Urticaria, angioedema (%) | 6.1 | 8.8 |

| Median of latency (minutes) | 120 [5–360] | 120 [5–360] |

| Urgent assistance (%) | 77 | 54 |

| Positive SPT | Group A [N(%)] | Group B [N(%)] |

|---|---|---|

|

Mites Dermatophagoides spp. |

66 (100) |

64 (100) |

| Blomia tropicalis | 48 (72.7) | 49 (76.6) |

| Storage mites | 42 (63.6) | 51 (79.7) |

| Pet epithelium (cat and dog) | 41 (62.1) | 33 (51.6) |

| Alternaria alternata | 1 (1.5) | 3 (4.7) |

| Pollen | 14 (21.2) | 8 (12.5) |

| Group A (n=66) | Group B (n=64) | |

|---|---|---|

| Medium total IgE (UI/L) [range] | 491.97 [15.8-4302] | 759.16 [51.2-4557] |

| + P-P raw limpet (%) | 61 | 66 |

| + P-P cooked limpet (%) | 61 | 71 |

| Median sIgE snail (kU/L) [range] | 0.375 [0.11-5.34] | 0,63 [0.10-87.5] |

| sIgE to snail >0,10 KU/L (%) | 51% | 91% |

| Allergen (kU/L) | Group A (n=52/66) | Group B (n=53/64) |

|---|---|---|

| Pen m 1 | 2/52 (3.8%) | 25/53 (47.17%) |

| Pen m 2 | 1/52 (1.9%) | 11/53 (20.75%) |

| Pen m 3 | 1/52 (1.9%) | 1/53 (1.87%) |

| Pen m 4 | 1/52 (1.9%) | 1/53 (1.87%) |

| Cra c 6 | 5/52 (9.6%) | 17/53 (32.08%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).