Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Causes of Meat Allergies in Childhood:

- 1.

- Beef: Beef allergies are relatively common in early childhood and can occur due to specific proteins found in this meat, such as alpha-gal (Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose), a carbohydrate found in animal meats (such as beef, pork, and lamb) and is the cause of a form of allergy known as "allergic reaction to alpha-gal" (Buchanan et al., 2013). Another allergen is Tropomyosin, a protein found in meat and is also a common cause of allergies to seafood and animal meat (Sampson, 2004).

- 2.

- Pork: Pork can also cause allergies, usually due to different proteins found in this meat. Reactions may also occur in response to chemicals used in meat processing (Buchanan et al., 2013).

- 3.

- Chicken: Chicken allergies are less common, but when they occur, they are usually linked to specific proteins in chicken meat, such as Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (Harris et al., 2015).Globally, the prevalence of meat allergies varies, but allergies to beef and pork are more common in childhood, especially in countries where consumption of these meats is widespread. Studies have shown that about 2-5% of children may be sensitive to beef, with a higher prevalence in Western countries (Sampson, 2004).

- In the Balkans, such as Albania, Serbia, and Greece, the prevalence of meat allergies is also present, but data is more limited compared to global statistics. For example, in Albania, studies have shown that allergies to beef and pork are common and often occur in combination with other food allergies (Muca et al., 2019).

- Chicken Meat Allergies: Chicken allergies are less frequent compared to beef and pork allergies. Around 1-2% of children may be sensitive to chicken (Harris et al., 2015).

- Seafood Allergies: Seafood allergies are common and often appear in childhood. They occur due to immune system reactions to specific proteins found in seafood products. Some of these proteins include:

- Tropomyosin: a muscle protein found in all seafood products, including crustaceans (e.g., shrimp, lobster) and mollusks (e.g., shellfish) (Sampson, 2004).

- Parvalbumin: a protein found in fish, such as tuna and hake. It is a common cause of fish allergies (Ebisawa et al., 2005).

- Serum albumin: a protein found in the blood of crustaceans and fish (Teng et al., 2015).

- Chitinase: a protein found in crustaceans and associated with allergies to shrimp and lobster (Sampson, 2004).

- Seafood allergies are quite common in many parts of the world. In some studies, the prevalence of allergies to crustaceans and fish may reach up to 1-3% of the population in certain regions (Kuehn et al., 2013). This is more common in areas where seafood consumption is high.

- In the Balkan region, seafood allergy prevalence is also present, but exact statistics may vary depending on the country and lifestyle. In some local studies, the prevalence of allergies to crustaceans and fish has been reported at varying levels, often influenced by diet and cultural practices (Kastrati et al., 2017).

Materials and Methods

Study Results

| Age Group | Total | Beef (f27) | Chicken (f83) | Pork (f26) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 years | 33 | 17 | 2 | 12 |

| 3-6 years | 22 | 17 | 0 | 14 |

| 6-12 years | 38 | 26 | 2 | 21 |

- Beef meat (f27) appears to be the most common allergen across all age groups, with an increasing prevalence in the 6-12 years group.

- Pork (f26) is also common, with a significant increase in the 6-12 years group.

- Chicken (f83) allergy is less common in all age groups.

- The 6-12 years group shows the highest number of positive cases for all allergens, indicating a higher prevalence of allergies in this age group.

| Age Group | Total | f207 Shellfish/Mollusks | f24 Shrimp | f23 Crab | f40 Tuna | f03 Codfish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 years | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3-6 years | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6-12 years | 38 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

- 0-3 years: No children with positive IgE for any of the tested allergens.

- 3-6 years: No positive cases for any of the tested allergens in this age group.

- In the 6-12 years group, several positive allergy cases were recorded: 1 case for shellfish/mollusks (f207), 2 cases for crab (f23), and 2 cases for tuna (f40), while no positive cases were found for shrimp (f24) and codfish (f03).

|

|

|

Discussion

Prevalence of Meat Allergies:

- Our study results show an increase in the prevalence of beef and pork allergies in children aged 6-12, supported by other studies such as those by Sicherer et al. (2011) for red meat and Mikkelson et al. (2015) for pork. This trend may be linked to continued exposure to these proteins in children's diets, as beef is a common protein source in children's food. Repeated exposure to these proteins may contribute to the development of sensitivity to them (Sicherer et al., 2011; Mikkelson et al., 2015).

- Furthermore, sensitivity to pork may increase with continued exposure and could be influenced by changes in meat processing, which may affect the structure and sensitivity to its proteins. Genetic factors might also play a significant role in the development of meat allergies, as individuals with a family history of allergies are more likely to develop sensitivity to these allergens (Kamath et al., 2014).

- In this study, we also observed that the prevalence of chicken allergy was low and stable across children's age groups. This result aligns with other studies (Kuehn et al., 2014). This phenomenon may be related to various factors, including early exposure to chicken, as children tend to consume this meat earlier than other types. It may also be linked to the nature of chicken proteins, which are more stable and less sensitive to processing and preservation. This could help maintain the prevalence of chicken allergy at lower levels (Kuehn et al., 2014).

Prevalence of Marine Allergen Allergies:

- Our study results on the prevalence of allergies to marine allergens confirm that these allergies manifest later and are more common in older children. This result aligns with findings by Sicherer et al. (2010). A possible reason for this is the change in children's diets and prolonged exposure to marine allergens as they grow older. Children who begin to consume a more diverse diet with marine products may develop allergies to these foods over time (Sicherer et al., 2010).

Correlations Between Allergens:

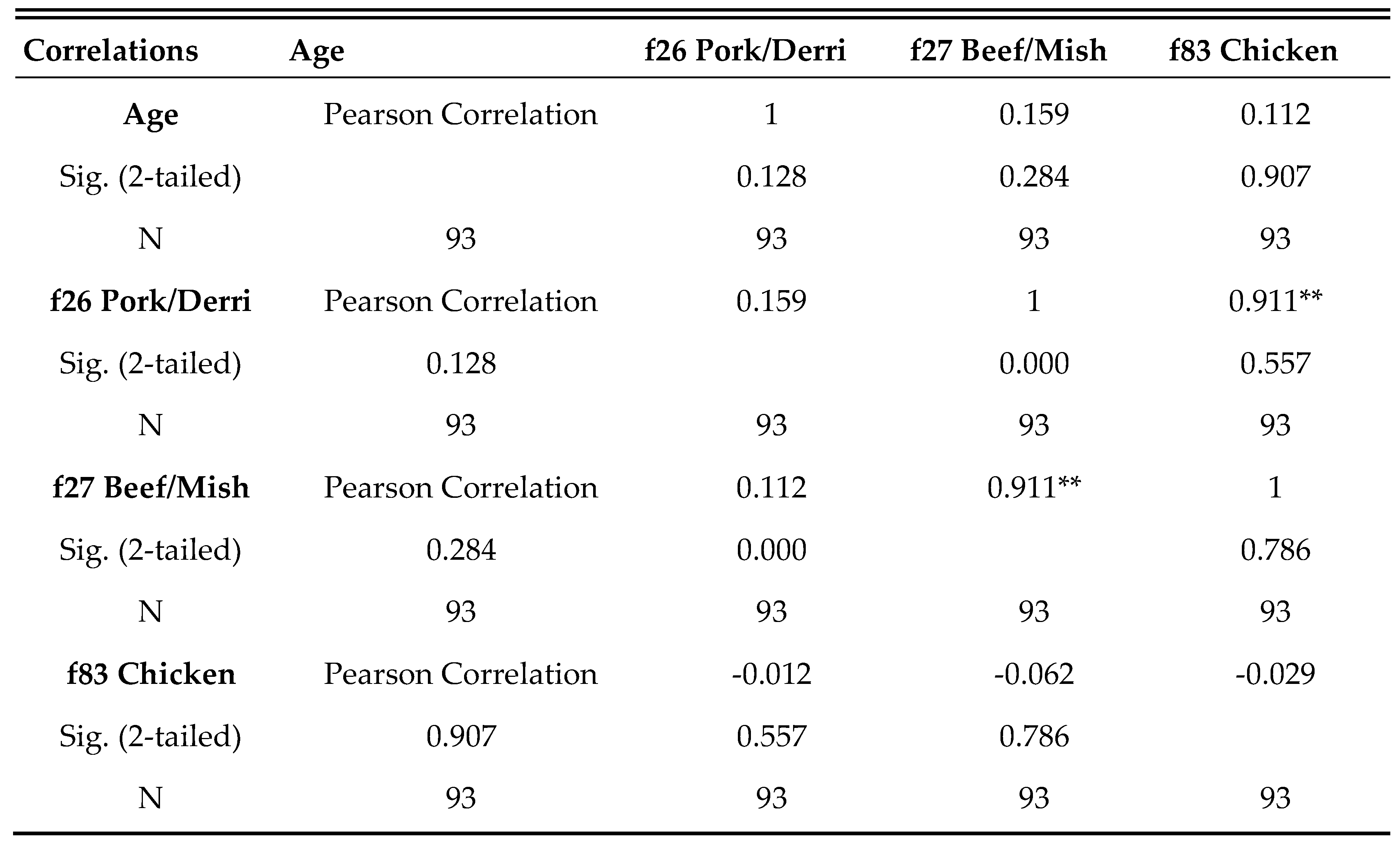

- In our study, strong correlations were observed between beef and pork allergies, with p-values ≤ 0.05. Similar correlations have been reported in other studies, suggesting a strong link between pork and beef allergies (Kalliomäki et al., 2005). This may occur due to the similarity in the protein components of the meats and the immune sensitivity to them, creating a shared immune response in individuals sensitive to these proteins.

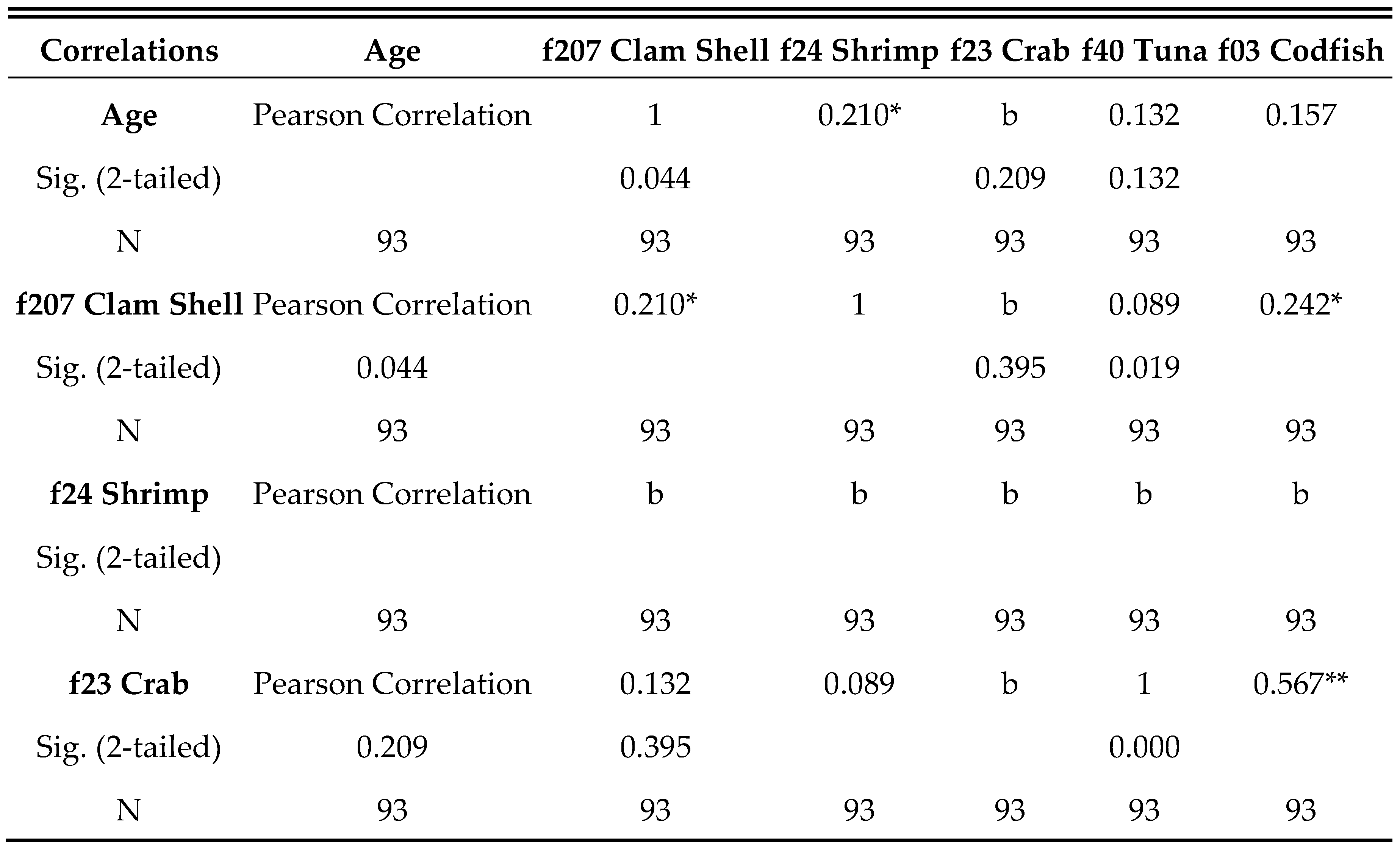

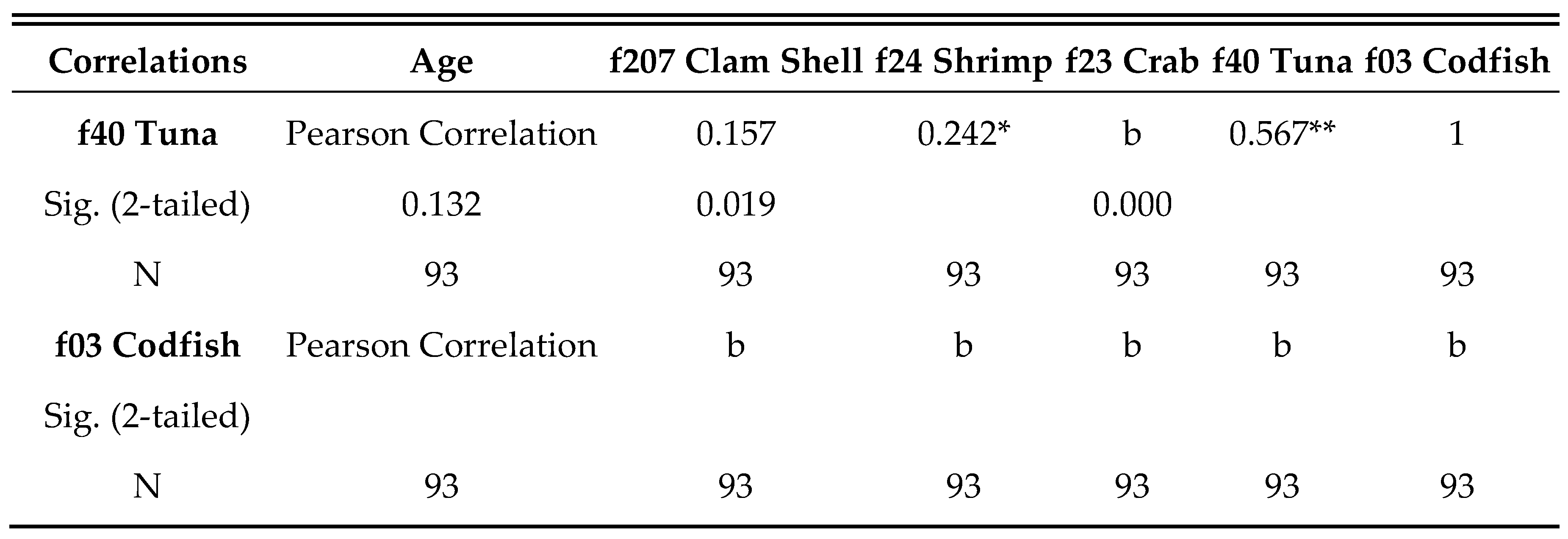

- Additionally, the relationship between positive IgE for tuna and other seafood allergens, such as shrimp and clam shell, suggests a possible cross-reactivity. This correlation aligns with studies indicating that there is a structural similarity among proteins in these seafood products, leading to a shared immune response to similar allergens (Aas et al., 2018). This result has important implications for allergy management, as individuals sensitive to one allergen may need to avoid all similar seafood products to prevent potential allergic reactions.

- Another significant result of this study was the identification of a similar structural link between seafood allergens. This finding is consistent with other studies (Aas et al., 2018), suggesting that consuming one seafood allergen could lead to the development of sensitivity to others. This may be explained by the structural similarity of proteins found in these seafood products, which can trigger a common immune response. For instance, tropomyosin, a protein found in many seafood products such as shrimp and mollusks, is known to cause similar allergic reactions in individuals sensitive to a seafood allergen. This structural similarity may explain why sensitivity to one allergen can lead to sensitivity to several others in the seafood allergen group. This phenomenon occurs because proteins in different seafood products, such as fish and crustaceans, often share similar structures that make individuals more sensitive to multiple seafood allergens simultaneously (Aas et al., 2018).

Conclusions

Prevalence of Meat Allergies:

- Beef and Pork: Red meat, specifically beef and pork, are the most common allergens in red meat, with increasing prevalence observed in the 6-12 year age group. This trend suggests that sensitivity to red meat increases with age.

- Poultry Allergy: The prevalence of poultry allergy is lower across all age groups and remains relatively constant.

Prevalence of Seafood Allergies:

- Age Group 0-3 years and 3-6 years: No positive cases for allergies to tested seafood allergens were recorded, suggesting that sensitivity to these allergens is relatively low at these ages.

- Age Group 6-12 years: Positive cases for allergies to mollusks (f207), shrimp (f23), and tuna (f40) were recorded. These allergies are only present in this age group, indicating an increase in sensitivity to these allergens as children grow. This trend may be linked to increased exposure to these seafood products, as well as the development of the immune system, which may become more reactive to seafood allergens.

Correlations:

- Correlation Between Pork and Beef: The finding of a strong and statistically significant correlation between positive IgE for pork and beef suggests a shared sensitivity to these two allergens. This correlation may result from the similarity of proteins found in beef and pork, which could trigger a similar immune response in sensitive individuals.

- Correlation Between Age and Seafood Allergen Consumption: A positive and statistically significant correlation was found between age and the consumption of mollusks, suggesting that as children age, they may consume more clam shell. Furthermore, statistically significant positive correlations were observed between the consumption of clam shell and tuna, and between the consumption of shrimp and tuna. This phenomenon suggests that increasing positive IgE values for tuna may lead to an increase in positive IgE for shrimp and clam shell, indicating the potential for shared sensitization to these seafood products. This trend may be linked to the common impact of proteins found in these foods.

References

- Aas, K., et al. (2018). Cross-reactivity between seafood allergens and implications for diagnosis and treatment. International Journal of Allergy and Immunology, 40(2), 114-118.

- Buchanan, R. L., et al. (2013). Allergic reaction to alpha-gal and its relationship to meat allergies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 132(1), 20-25.

- Ebisawa, M., et al. (2005). Parvalbumin in fish allergy and the molecular mechanisms of allergic reactions to fish. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 5(3), 211-217.

- Harris, K. M., et al. (2015). Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein and food allergy to poultry. Journal of Immunology, 194(3), 1334-1341.

- Kamath, S. K., et al. (2014). Genetic factors and the development of food allergies. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 25(7), 621-627.

- Kalliomäki, M., et al. (2005). A potential relationship between meat allergy and childhood food sensitivities. European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 60(9), 2453-2459.

- Kastrati, G., et al. (2017). The impact of diet on food allergies in the Balkans: A comparative study. Balkan Medical Journal, 34(4), 352-358.

- Kuehn, H. S., et al. (2013). Prevalence and symptoms of seafood allergy in different populations. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 131(5), 1376-1383.

- Kuehn, H. S., et al. (2014). The role of poultry proteins in childhood food allergies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 134(6), 1220-1222.

- Mikkelson, A. J., et al. (2015). Red meat allergies and their correlation with other food allergies. Allergy Reviews, 4(3), 208-213.

- Muca, D., et al. (2019). Prevalence of food allergies in Albanian children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 143(4), 1489-1491.

- Sampson, H. A. (2004). Food allergies: A review of epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 113(5), 798-805.

- Sicherer, S. H., et al. (2010). Food allergy: Epidemiology and risk factors. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 125(2), 461-467.

- Teng, Z., et al. (2015). Role of serum albumin in seafood allergy. Allergy Reviews, 5(2), 201-208.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).