Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

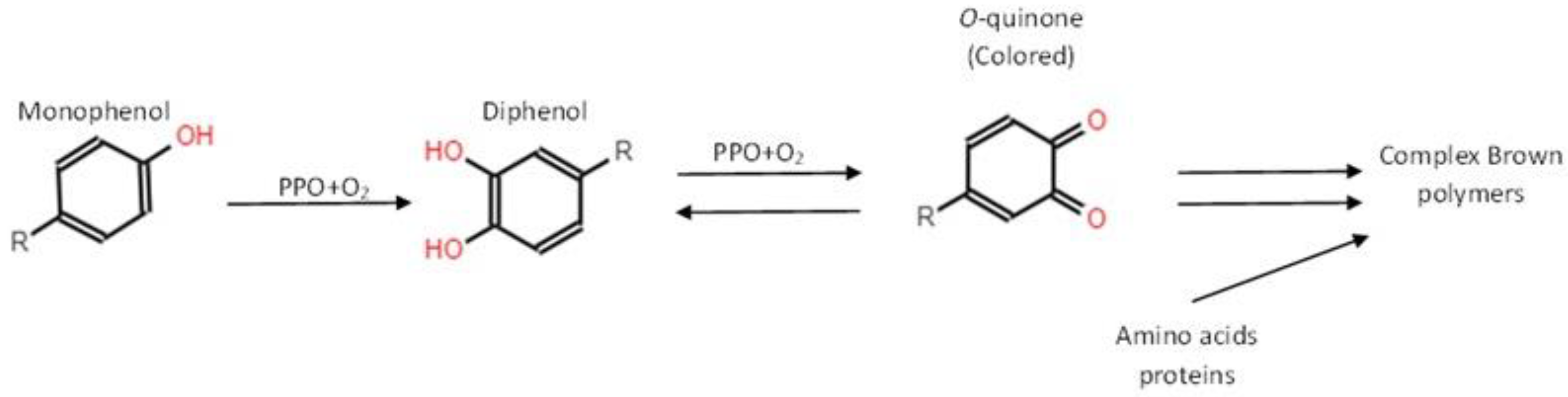

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

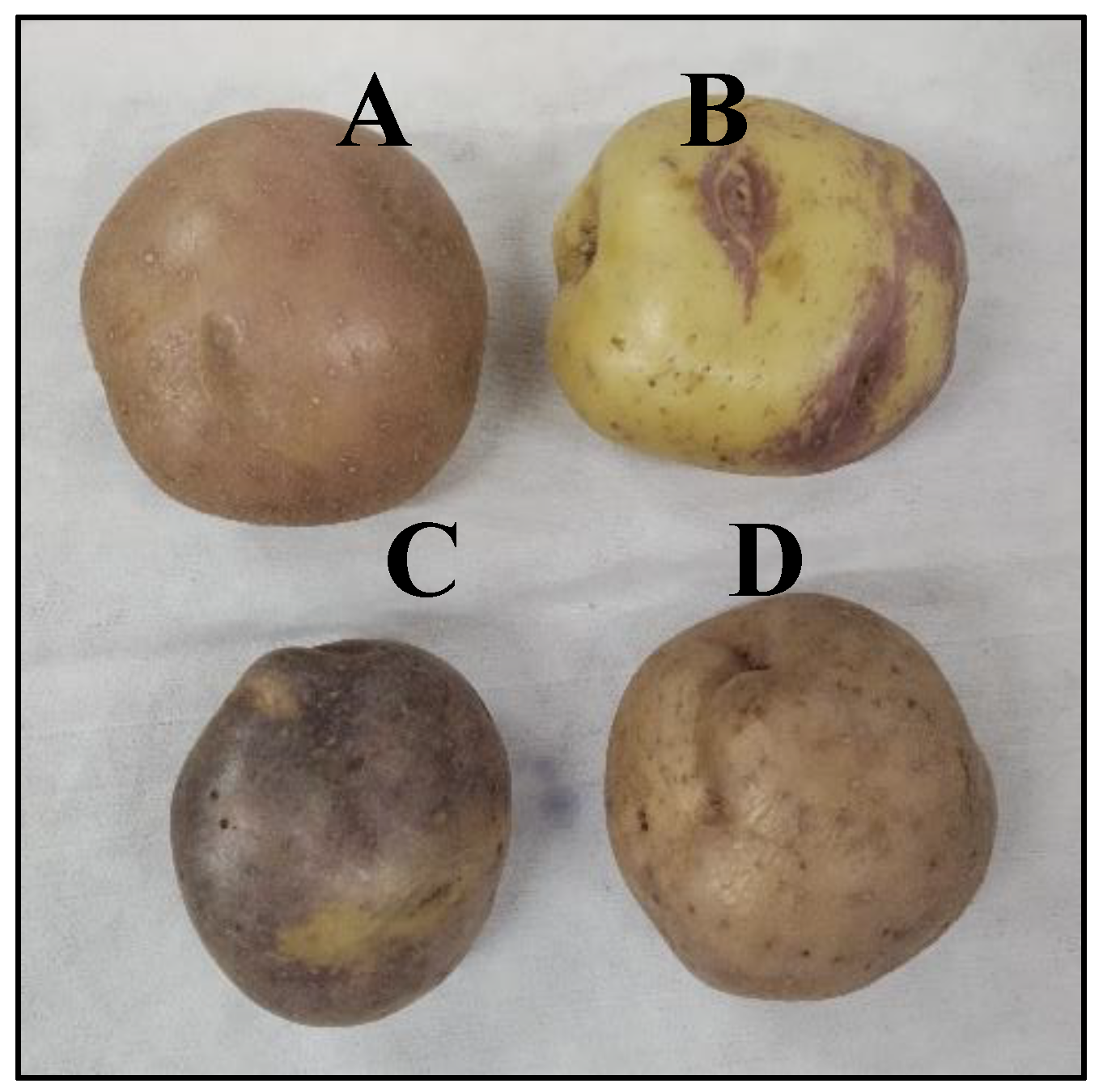

2.2. Variety Characterization

2.2.1. Hysicochemical Characterization

2.2.2. Color Assessment and Browning Index (BI)

2.2.3. Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) Activity, and Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.2.4. Microstructural Characterization

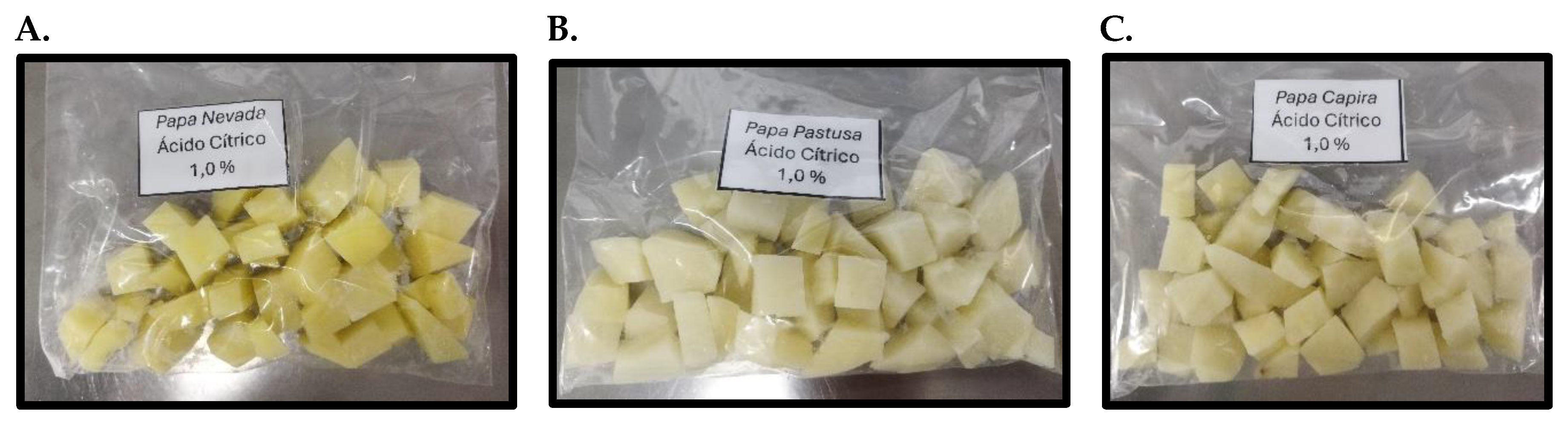

2.3. Anti-Browning Treatments

- -

- CC: Immersion in water as a control. Distilled water was used to submerge the potato pieces as a control treatment, keeping the same ratio, immersion time, and subsequent activities.

- -

- AE: Immersion in Garlic Extract criollo variety at 0.5%. The methodology was based on [28]. Firstly, a preliminary test was made using a national variety and a foreign variety, this is, criollo and chino garlic varieties. Since criollo variety showed better anti-browning capacity, it was used for the study (data not shown). 100 g cloves of garlic was homogenized with distilled water to obtain a solution mixture containing 0.5% (m/m), and the homogenate was filtered. The supernatant was collected to use as a fresh garlic extract [26].

- -

- AA: Immersion in Ascorbic Acid at 1.0%. The methodology was based on [19]. Firstly, a 1% ascorbic acid solution was prepared with distilled water. The solution was assisted in preparation through homogenization using a glass bar.

- -

2.4. Anti-Browning Treatment Selection

2.5. Sensory Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Varieties

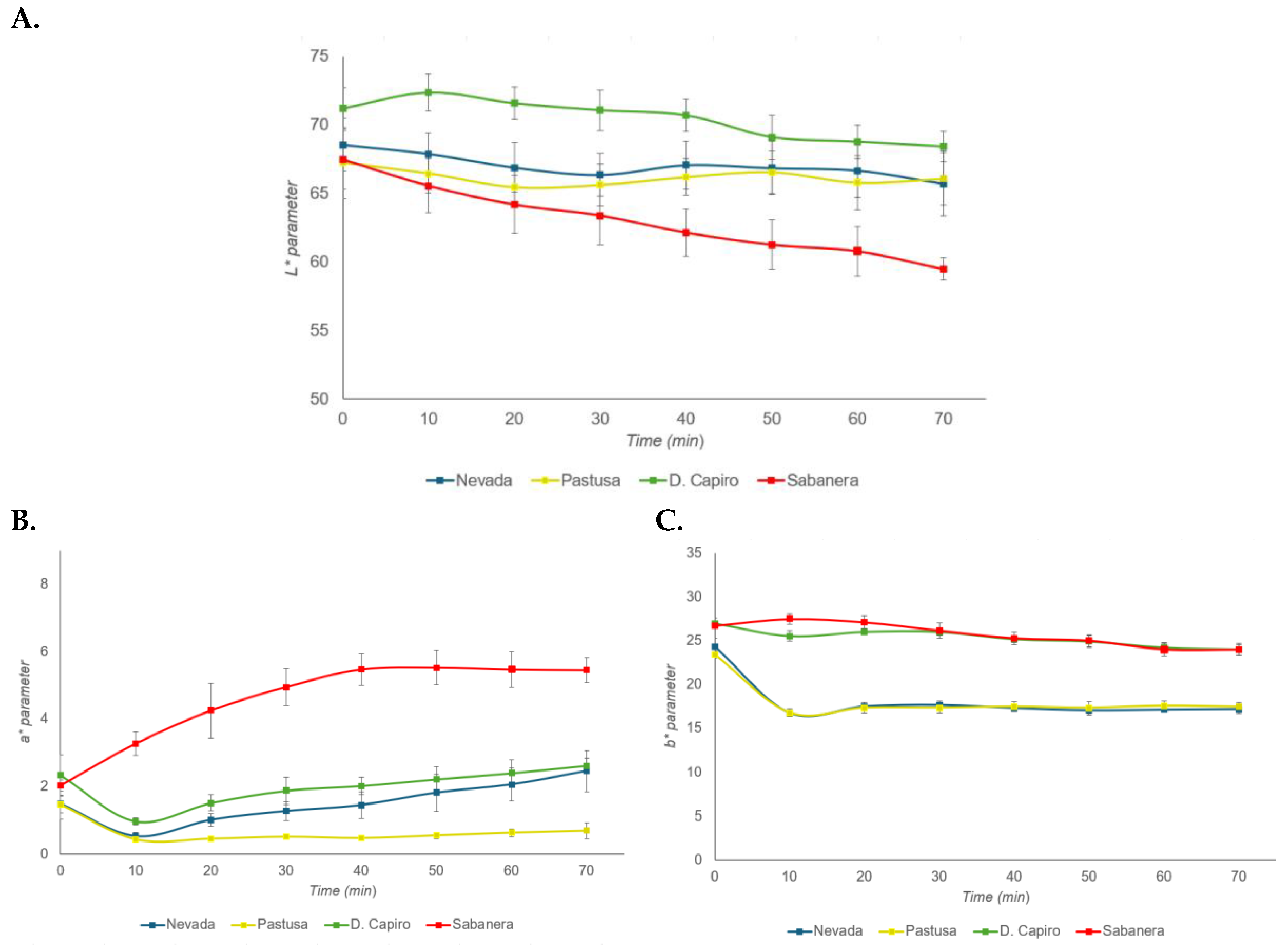

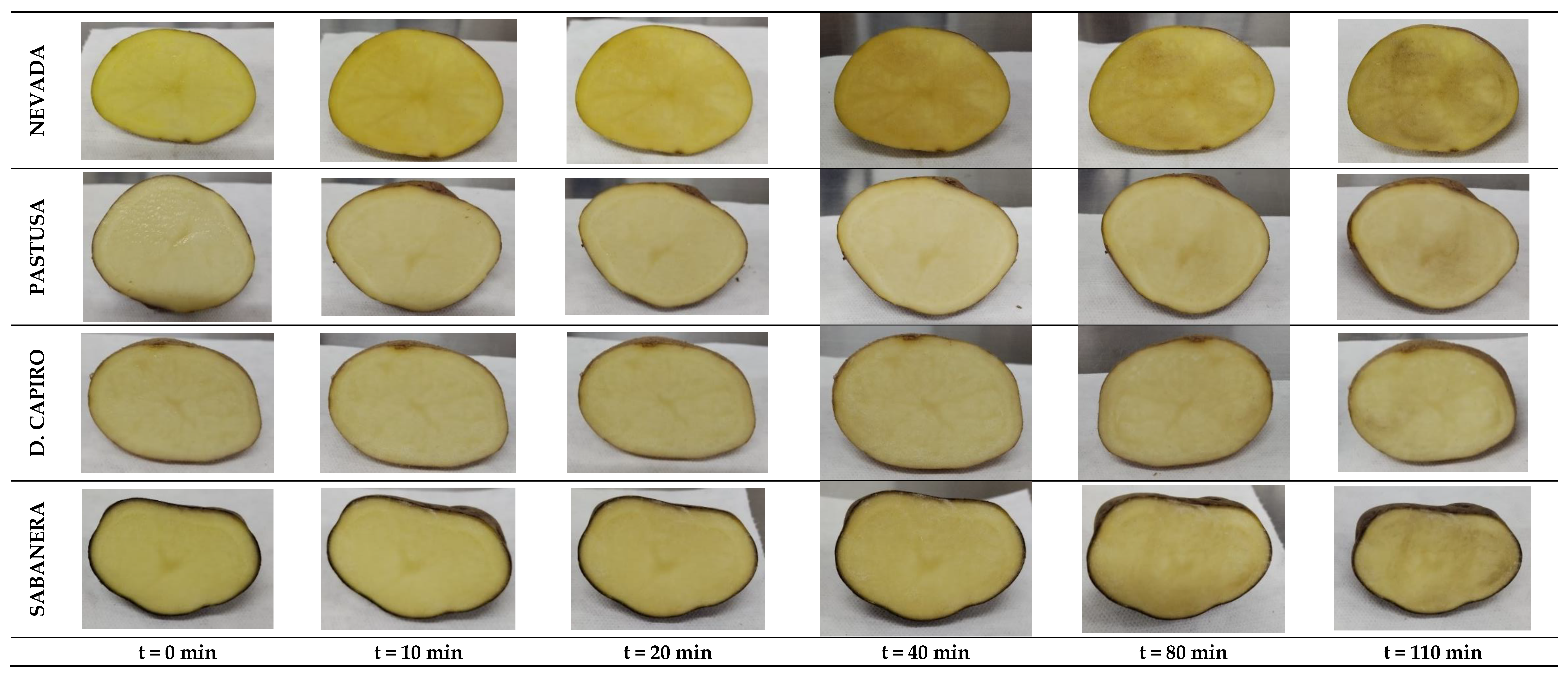

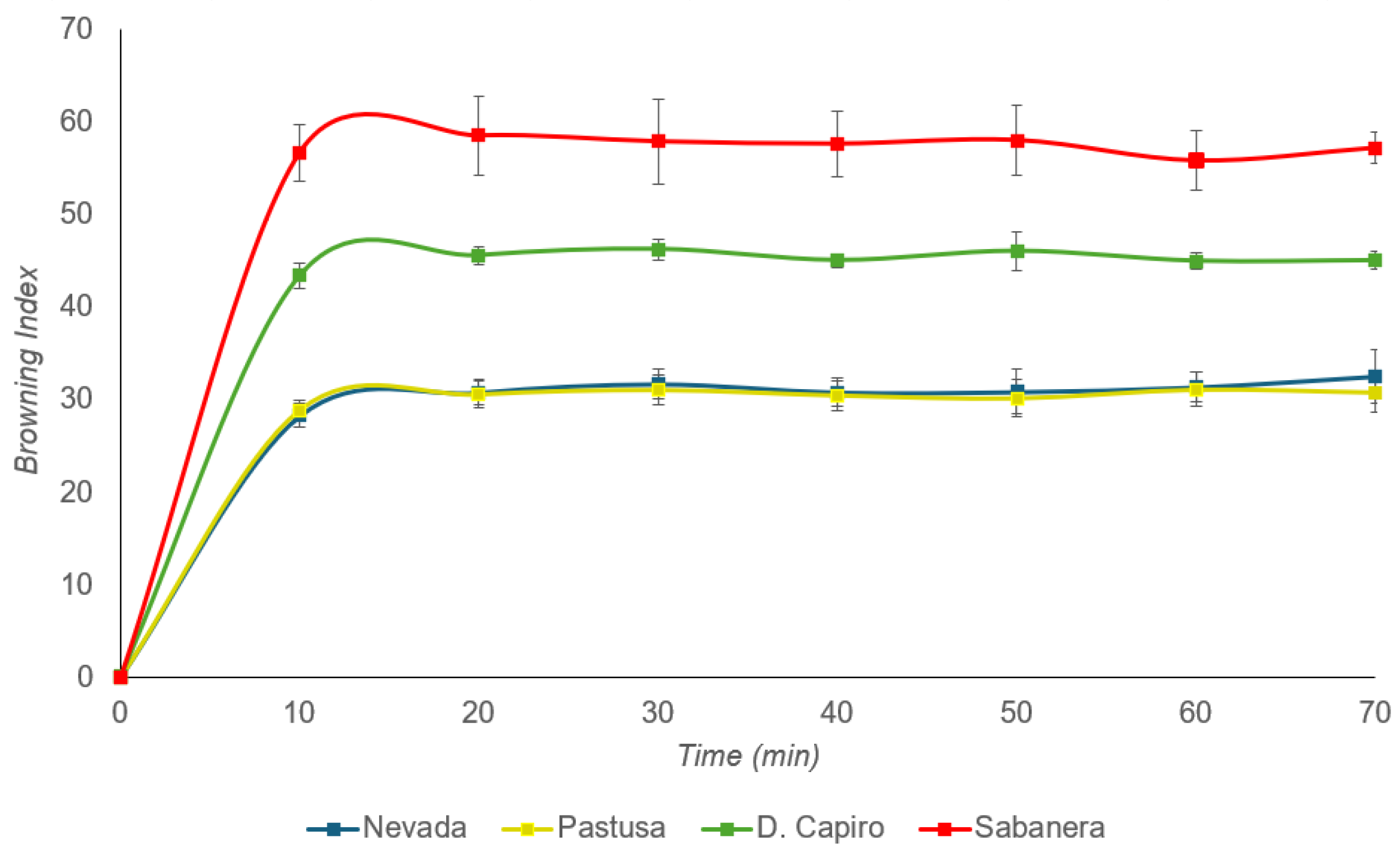

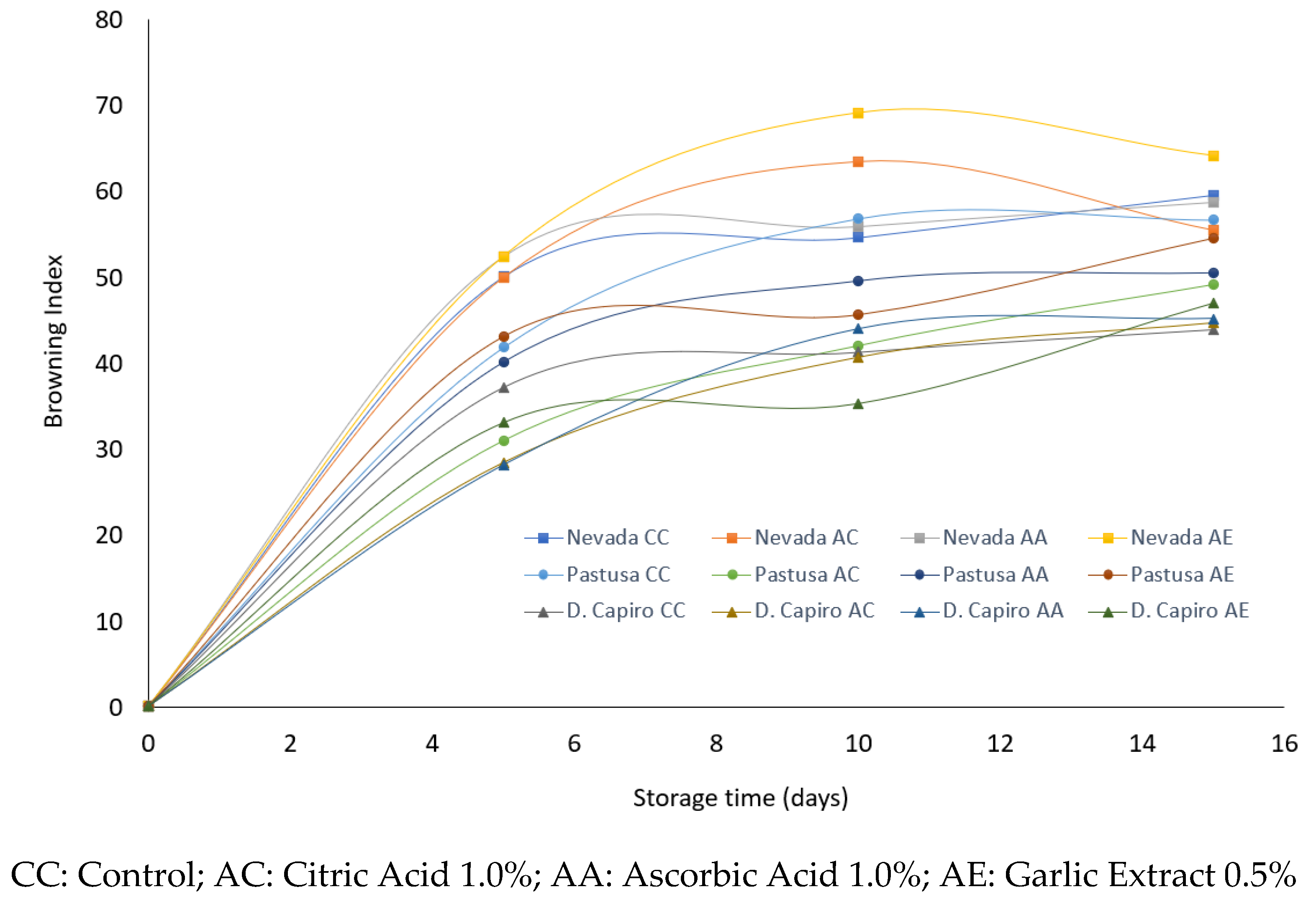

3.2. Color Assessment and Browning Index (BI)

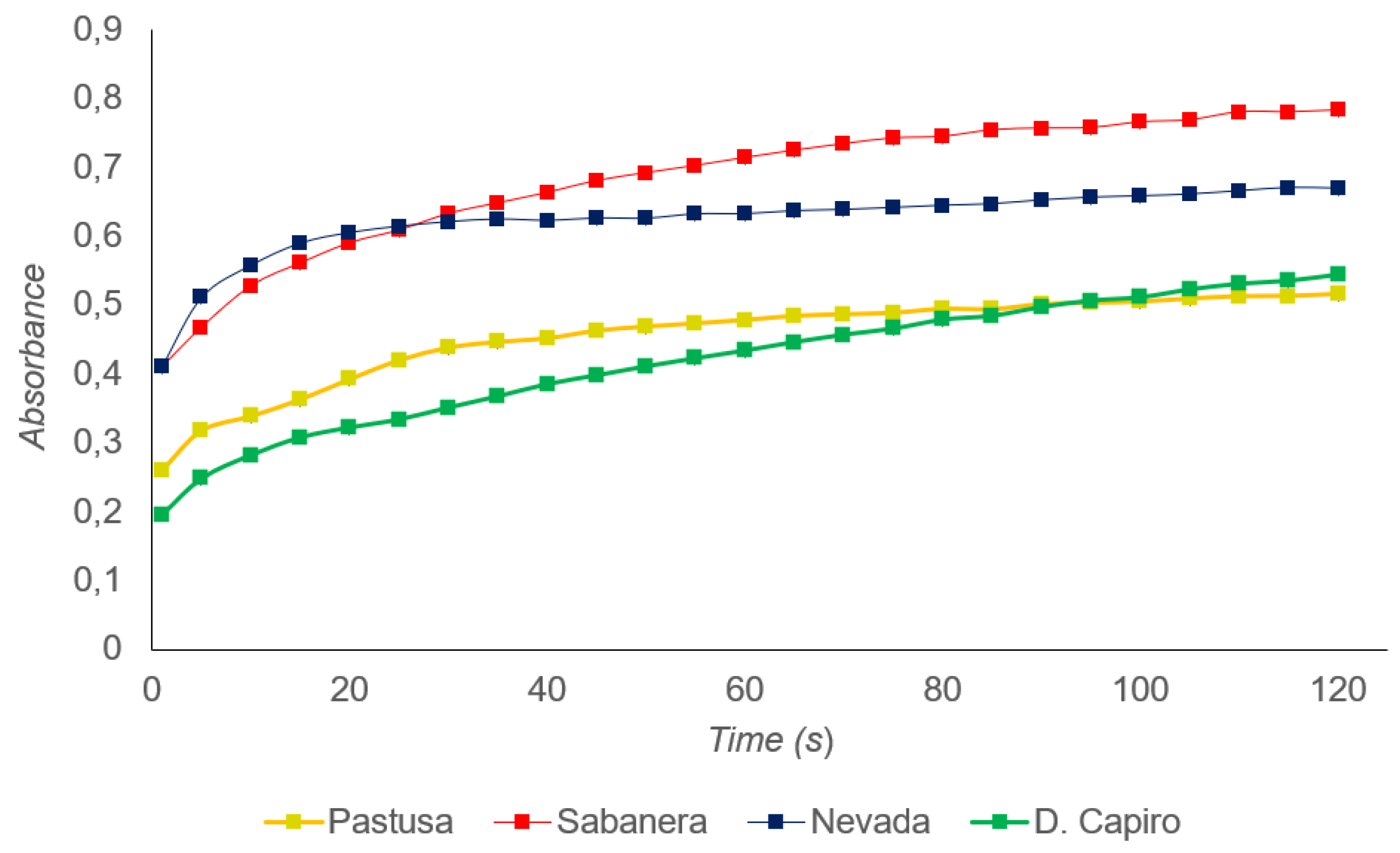

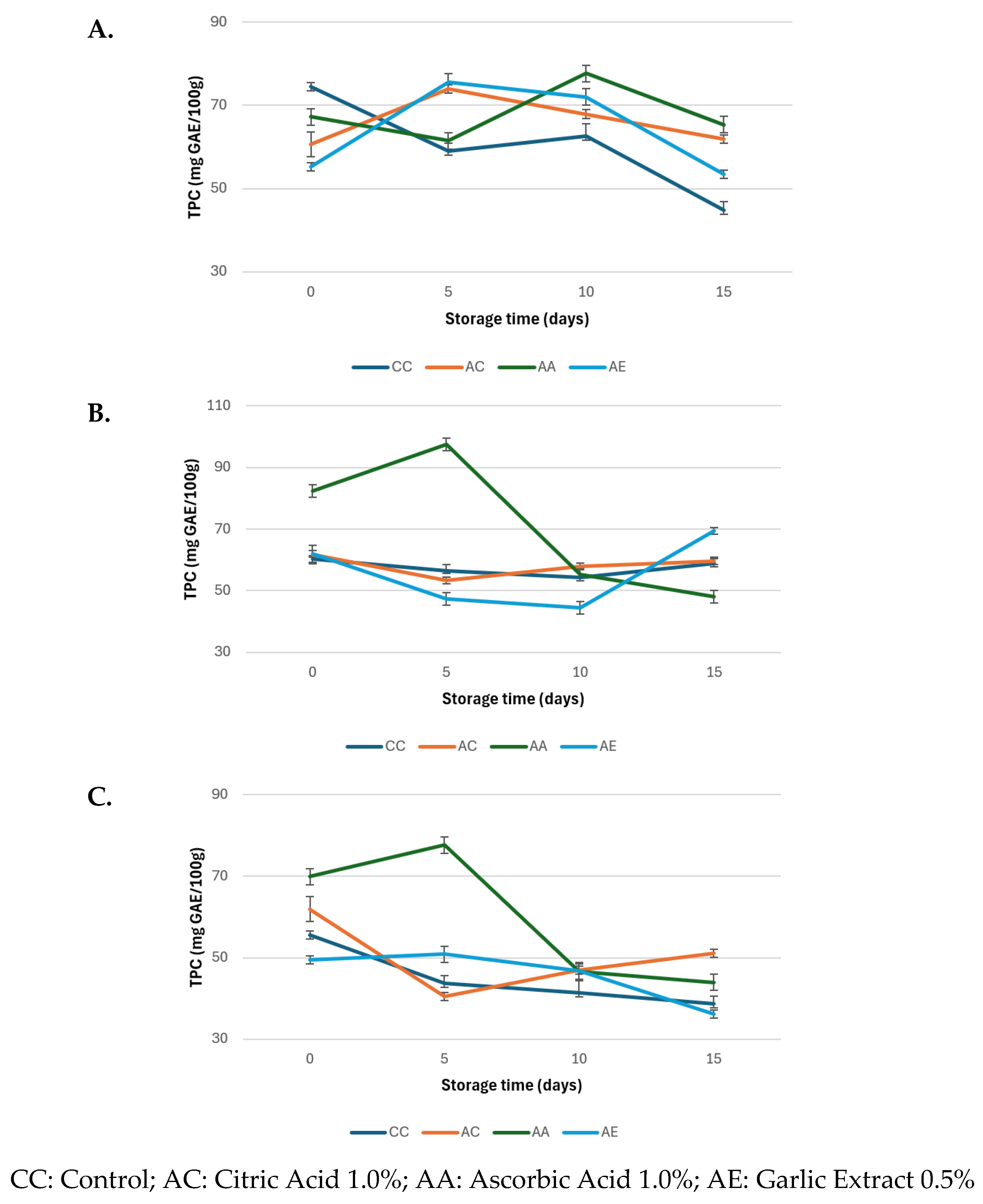

3.3. Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) Activity, and Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

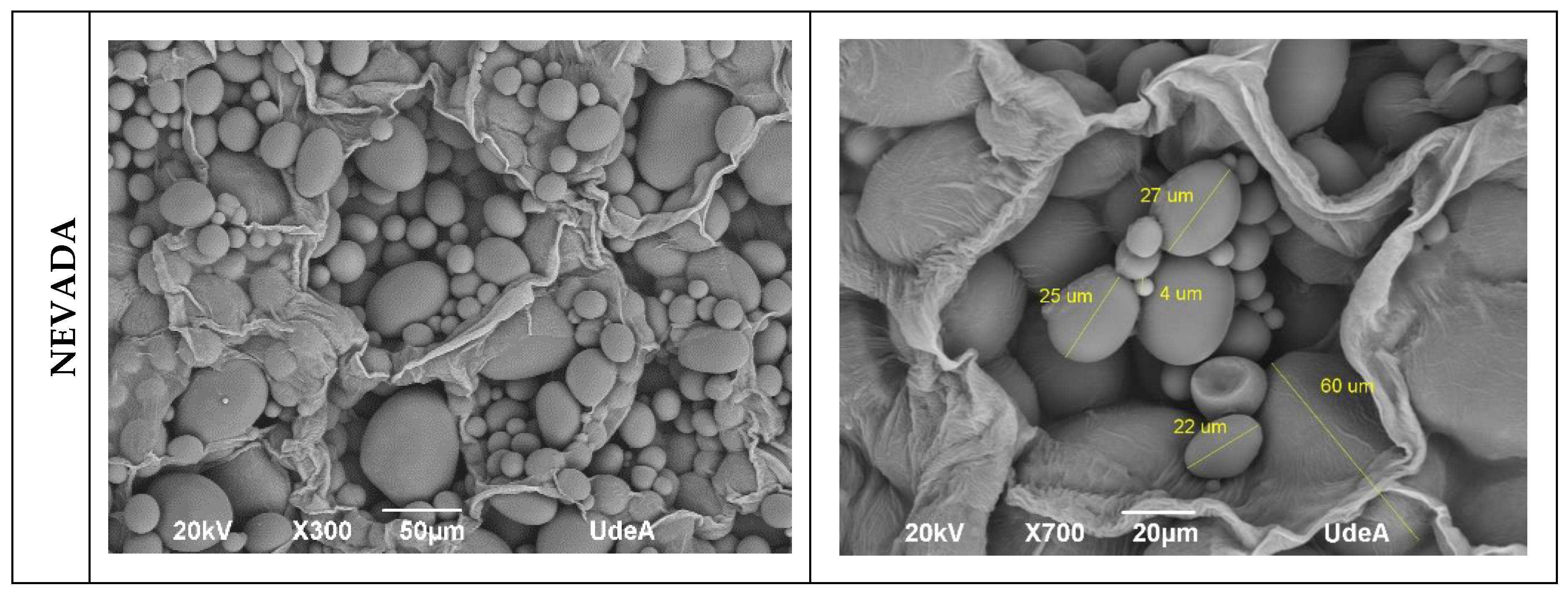

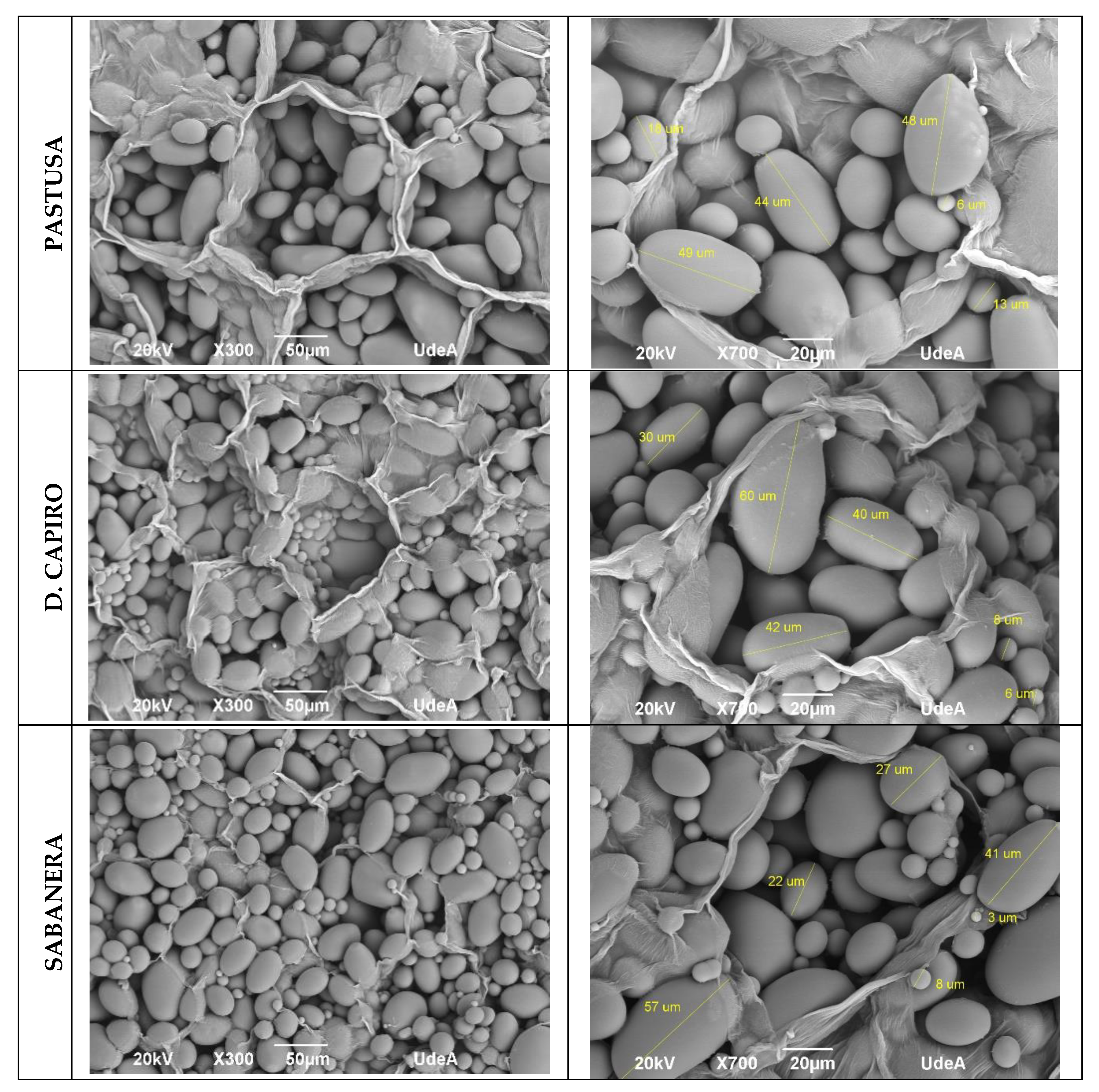

3.4. Microstructural Characterization

3.5. Evaluation of Anti-Browning Treatments

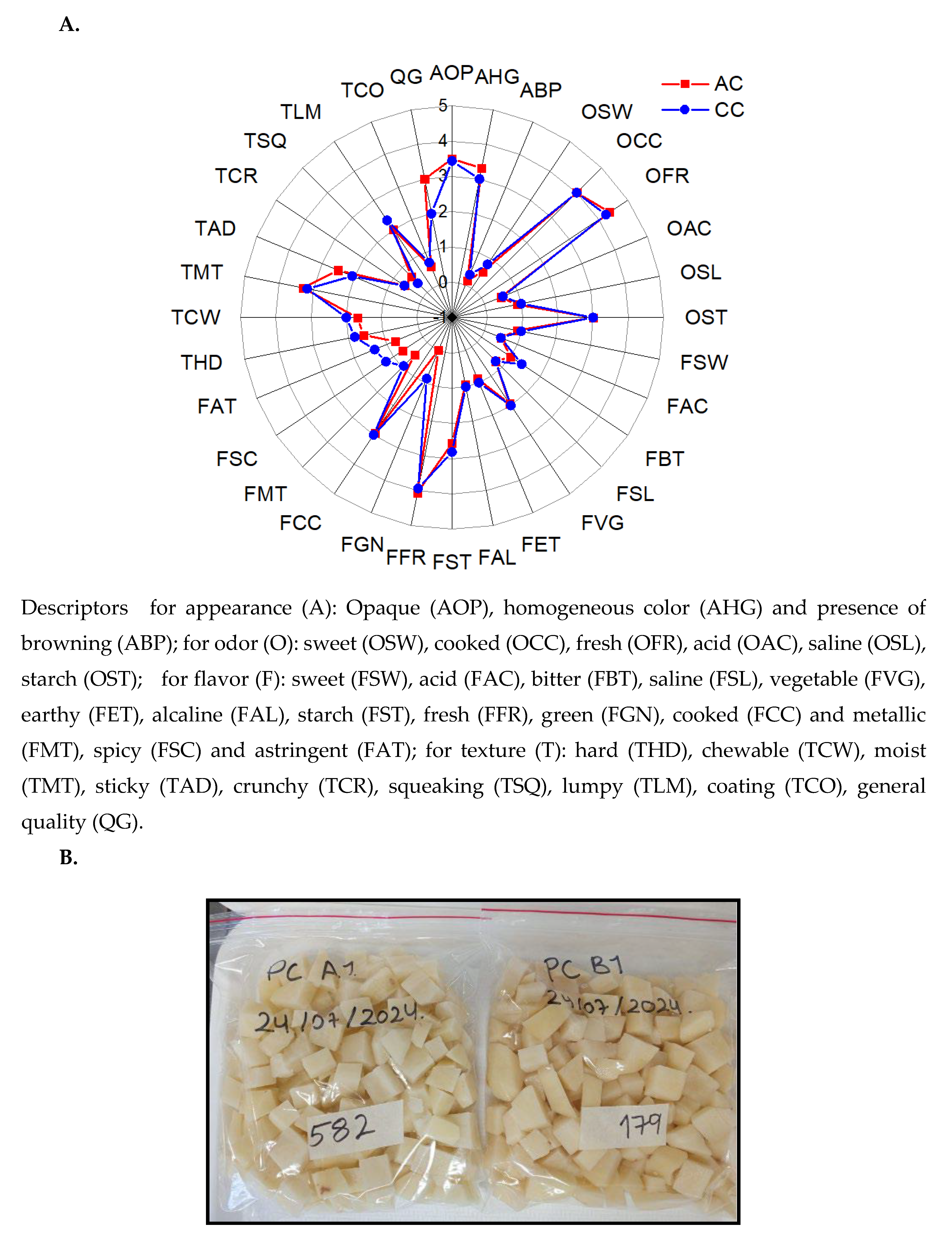

3.6. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, P. Effects of the Combined Treatment of Trans-2-Hexenal, Ascorbic Acid, and Dimethyl Dicarbonate on the Quality in Fresh-Cut Potatoes (Solanum Tuberosum L.) during Storage. Foods 2024, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, B.A.F.; Alexandre, A.C.S.; de Andrade, G.A.V.; Zanzini, A.P.; de Barros, H.E.A.; Ferraz e Silva, L.M. dos S.; Costa, P.A.; Boas, E.V. de B.V. Recent Advances in Processing and Preservation of Minimally Processed Fruits and Vegetables: A Review – Part 2: Physical Methods and Global Market Outlook. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levaj, B.; Pelaić, Z.; Galić, K.; Kurek, M.; Ščetar, M.; Poljak, M.; Dite Hunjek, D.; Pedisić, S.; Balbino, S.; Čošić, Z.; et al. Maintaining the Quality and Safety of Fresh-Cut Potatoes (Solanum Tuberosum): Overview of Recent Findings and Approaches. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Correa, Y.; Vargas-Carmona, M.I.; Vásquez-Restrepo, A.; Ruiz Rosas, I.D.; Pérez Martínez, N. Native Potato (Solanum Phureja) Powder by Refractance Window Drying: A Promising Way for Potato Processing. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kaur, L. Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo-García, G.; Arroqui, C.; Merino, G.; Vírseda, P. Antibrowning Compounds for Minimally Processed Potatoes: A Review. Food Reviews International 2020, 36, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Suri, K.; Shevkani, K.; Kaur, A.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Enzymatic Browning of Fruit and Vegetables: A Review. In Enzymes in Food Technology; Kuddus, M., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 63–78. ISBN 9789811319327. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Bai, J.; Wu, M.; Zhao, M.; Wang, R.; Guo, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, T. Studies on Browning Inhibition Technology and Mechanisms of Fresh-Cut Potato. J Food Process Preserv 2017, 41, e13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Bartolini, S.; Sanmartin, C.; Orlando, M.; Taglieri, I.; Macaluso, M.; Lucchesini, M.; Trivellini, A.; Zinnai, A.; Mensuali, A. Potato Peels as a Source of Novel Green Extracts Suitable as Antioxidant Additives for Fresh-Cut Fruits. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbo, S.; Piergiovanni, L. Shelf Life of Minimally Processed Potatoes: Part 1. Effects of High Oxygen Partial Pressures in Combination with Ascorbic and Citric Acids on Enzymatic Browning. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2006, 39, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; El-Gizawy, A.M.; El-Bassiouny, R.E.I.; Saleh, M.A. Browning Inhibition Mechanisms by Cysteine, Ascorbic Acid and Citric Acid, and Identifying PPO-Catechol-Cysteine Reaction Products. J Food Sci Technol 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, M.; Zhao, M.; Guo, M.; Liu, H. Enzymatic Properties on Browning of Fresh-Cut Potato. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 397, 012116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiapelo, L.; Blasi, F.; Ianni, F.; Barola, C.; Galarini, R.; Abualzulof, G.W.; Sardella, R.; Volpi, C.; Cossignani, L. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Chlorogenic Acid from Potato Sprout Waste and Enhancement of the In Vitro Total Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Lu, S.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, R.; Lu, X.; Pang, L.; Cheng, J.; Wang, L. Tea Polyphenols Inhibit the Occurrence of Enzymatic Browning in Fresh-Cut Potatoes by Regulating Phenylpropanoid and ROS Metabolism. Plants 2024, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijpers, T.F.M.; Van Herk, T.; Vincken, J.P.; Janssen, R.H.; Narh, D.L.; Van Berkel, W.J.H.; Gruppen, H. Potato and Mushroom Polyphenol Oxidase Activities Are Differently Modulated by Natural Plant Extracts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prisacaru, A.E.; Ghinea, C.; Albu, E.; Ursachi, F. Effects of Ginger and Garlic Powders on the Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics of Fruit Juices during Storage. Foods 2023, 12, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, N.; Lee, C.H.; Wong, S.L.; Fauzi, C.E.N.C.A.; Zamri, N.M.A.; Lee, T.H. Prevention of Enzymatic Browning by Natural Extracts and Genome-Editing: A Review on Recent Progress. Molecules 2022, 27, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.Y.; Cheun, C.F.; Wong, C.W. Inhibition of Enzymatic Browning in Sweet Potato ( Ipomoea Batatas (L.)) with Chemical and Natural Anti-browning Agents. J Food Process Preserv 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Procaccini, L.M.; Capezio, S.B. Utilización de Antioxidantes En Papa (Solanum Tuberosum L) Mínimamente Procesada. Revista latinoamericana de la Papa 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, P.A.; Andreu, A.B.; Colman, S.L.; Clausen, A.M.; Feingold, S.E. Pardeamiento Enzimático: Caracterización Fenotípica, Bioquímica y Molecular En Variedades de Papa Nativas de La Argentina. Revista Latinoamericana de la Papa, ISSN 1019-6609, ISSN-e 1853-4961, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2009, págs. 66-72 2016, 15, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbún, J.; Esquivel, P.; Brenes, A.; Alfaro, I. Propiedades físico-químicas y parámetros de calidad para uso industrial de cuatro variedades de papa. RAC 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.N.; Massa, G.A.; Andersson, M.; Turesson, H.; Olsson, N.; Fält, A.-S.; Storani, L.; Décima Oneto, C.A.; Hofvander, P.; Feingold, S.E. Reduced Enzymatic Browning in Potato Tubers by Specific Editing of a Polyphenol Oxidase Gene via Ribonucleoprotein Complexes Delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Sánchez, S.; Mosquera-Palacios, Y.; David-Úsuga, D.; Cartagena-Montoya, S.; Duarte-Correa, Y. Effect of Processing Methods on the Postharvest Quality of Cape Gooseberry (Physalis Peruviana L.). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Calderón, J.; Calderón-Jaimes, L.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; García-Villanova, B. Antioxidant Capacity, Phenolic Content and Vitamin C in Pulp, Peel and Seed from 24 Exotic Fruits from Colombia. Food Research International 2011, 44, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanine, T.N.; Nidia, V.C.; Daniel, D.O. Characterization of the Polyphenoloxidase in Three Varieties of Potato (Solanum Tuberosum L.) Minimally Processed and Its Color Effect @LIMENTECH CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA ALIMENTARIA CORE View Metadata, Citation and Similar Papers at Core.Ac.Uk. LIMENTECH CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA ALIMENTARIA 2013, 11, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Di̇Ken, M.E. Inhibitiory Effect of Garlic Extracts on Polyphenoloxidase. Balıkesir Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi 2020, 22, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Correa, Y.; Granda-Restrepo, D.; Cortés, M.; Vega-Castro, O. Potato Snacks Added with Active Components: Effects of the Vacuum Impregnation and Drying Processes. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsikrika, K.; Tzima, K.; Rai, D.K. Recent Advances in Anti-Browning Methods in Minimally Processed Potatoes—A Review. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46, e16298–e16298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martínez, B.S.R.-D. J. Evaluación de Dos Combinaciones de Conservantes y Su Efecto Sobre Un Producto Hortícola de IV Gama. 2021.

- Guzmán Valverde, B.; Castañeda, D.; Marino, J.; Chris, D. Efecto de Gelatinización y Retrogradación En Las Características Funcionales y Reológicas de Almidones de Papa (Solanum Tuberosum) Precocidas. Repositorio Institucional - UNS, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, G. Stef De Hann, / Potencial Nutricional de La Papa Composición Nutricional de La Papa. 2019.

- Burgos, G.; Auqui, S.; Amoros, W.; Salas, E.; Bonierbale, M. Ascorbic Acid Concentration of Native Andean Potato Varieties as Affected by Environment, Cooking and Storage. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2009, 22, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingallina, C.; Spano, M.; Sobolev, A.P.; Esposito, C.; Santarcangelo, C.; Baldi, A.; Daglia, M.; Mannina, L. Characterization of Local Products for Their Industrial Use: The Case of Italian Potato Cultivars Analyzed by Untargeted and Targeted Methodologies. Foods 2020, 9, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daas Amiour, S.; Hambaba, L. Effect of pH, Temperature and Some Chemicals on Polyphenoloxidase and Peroxidase Activities in Harvested Deglet Nour and Ghars Dates. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2016, 111, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morante Carriel, J.; Agnieszka Obrebska, A.; Bru-Martínez, R.; Carranza Patiño, M.; Pico-Saltos, R.; Nieto Rodriguez, E. Distribution, Location anD Inhibitors of Polyphenol oxiDases in Fruits anD Vegetables useD as fooD. Ciencia y Tecnología 7.

- Nemś, A.; Pęksa, A. Polyphenols of Coloured-Flesh Potatoes as Native Antioxidants in Stored Fried Snacks. LWT 2018, 97, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, R.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A. Beneficial Phytochemicals in Potato — a Review. Food Research International 2013, 50, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, A.; Bakowska-Barczak, A.; Hamouz, K.; Kułakowska, K.; Lisińska, G. The Effect of Frying on Anthocyanin Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Crisps from Red- and Purple-Fleshed Potatoes (Solanum Tuberosum L.). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2013, 32, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perla, V.; Holm, D.G.; Jayanty, S.S. Effects of Cooking Methods on Polyphenols, Pigments and Antioxidant Activity in Potato Tubers. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2012, 45, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Correa, Y.; Vega-Castro, O.; López-Barón, N.; Singh, J. Fortifying Compounds Reduce Starch Hydrolysis of Potato Chips during Gastro-small Intestinal Digestion in Vitro. Starch Stärke 2021, 73, 2000196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkova, D.; Lachman, J.; Hamouz, K.; Vokal, B. Effect of Cultivar, Location and Year on Total Starch, Amylose, Phosphorus Content and Starch Grain Size of High Starch Potato Cultivars for Food and Industrial Processing. Food Chemistry 2013, 141, 3872–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bilbao-Sainz, C.; Wood, D.; Chiou, B.-S.; Powell-Palm, M.J.; Chen, L.; McHugh, T.; Rubinsky, B. Effects of Isochoric Freezing Conditions on Cut Potato Quality. Foods 2021, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapi, J.C.; Gnangui, S.N.; Dabonné, S.; Kouamé, L.P. Inhibitory Effect of Onions and Garlic Extract on the Enzymatic Browning of an Edible Yam (Dioscorea Cayenensis-Rotundata Cv. Kponan) Cultivated in Côte d Ivoire. International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review 2015, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, M.P.; Prenzler, P.D.; Scollary, G.R. Ascorbic Acid-Induced Browning of (+)-Catechin In a Model Wine System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q. Cysteine Protease Inhibitors Reduce Enzymatic Browning of Potato by Lowering the Accumulation of Free Amino Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2467–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.M.; Kwon, E.-B.; Lee, B.; Kim, C.Y. Recent Trends in Controlling the Enzymatic Browning of Fruit and Vegetable Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouvaltzis, P.; Brecht, J.K. Inhibition of Enzymatic Browning of Fresh-Cut Potato by Immersion in Citric Acid Is Not Solely Due to pH Reduction of the Solution: Immersion of Fresh-Cut Potato in Citric Acid. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2017, 41, e12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.S.; Hunt, I.; Bound, S.A.; Swarts, N.D. Crop Load, Fruit Quality and Mineral Nutrition as Predictors of Fruit Softening and Internal Flesh Browning in Modern Firm Fleshed Apple Cultivars. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 330, 113035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Lai, Y.; Chang, S.K.; Wang, Y.; Qu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, H. Regulation of Browning and Senescence of Litchi Fruit Mediated by Phenolics and Energy Status: A Postharvest Comparison on Three Different Cultivars. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2020, 168, 111280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Correa, Y.; Díaz-Osorio, A.; Osorio-Arias, J.; Sobral, P.J.A.; Vega-Castro, O. Development of Fortified Low-Fat Potato Chips through Vacuum Impregnation and Microwave Vacuum Drying. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2020, 102437–102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variety | Moisture (%) |

pH |

TPC (mg GAE/100g) |

Total acidity (%) |

TSS (°Brix) |

Vitamin C (mg/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nevada | 77.99 ± 1.20b | 6.76 ± 0.05c | 117.27 ± 3.66d | 0.12 ± 0.02a | 4.23 ± 0.12a | 41.83 ± 0.14c |

| Pastusa | 82.43 ± 0.86c | 6.57 ± 0.02a | 43.38 ± 1.89a | 0.10 ± 0.01a | 4.03 ± 0.12a | 37.70 ± 5.66b,c |

| D. Capiro | 80.92 ± 0.98c | 6.66 ± 0.07b | 51.04 ± 1.67b | 0.16 ± 0.01b | 4.10 ± 0.12a | 30.83 ± 0.68b |

| Sabanera | 73.79 ± 1.41a | 6.77 ± 0.03c | 63.79 ± 2.85c | 0.16 ± 0.01b | 4.16 ± 0.12a | 22.92 ± 4.79a |

| Variety | Color parameters CIE L*a*b* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | |

| Nevada | 68.54 ± 1.93a,b | 1.50 ± 0.46 a,b | 23.34 ± 0.89a |

| Pastusa | 67.20 ± 2.57a | 1.48 ± 0.26 a | 24.36 ± 0.43b |

| D. Capiro | 71.20 ± 1.51b | 2.34 ± 0.61c | 26.74 ± 0.60 c |

| Sabanera | 67.46 ± 2.15a | 2.04 ± 0.17b,c | 27.00 ± 0.32c |

| ΔE Nevada |

Storage time (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| CC | 13.53 ± 0.95c | 11.87 ± 1.38c | 11.12 ± 0.93a | 15.79 ± 0.67c |

| AC | 8.57 ± 1.13b | 7.08 ± 1.30a | 11.09 ± 1.33a | 10.21 ± 0.13a |

| AA | 6.17 ± 0.78a | 9.78 ± 1.48b | 11.46 ± 1.25a | 14.45 ± 0.33b |

| AE | 9.22 ± 1.40b | 8.25 ± 1.88a | 10.03 ± 1.84a | 14.24 ± 0.61b |

| ΔE Pastusa |

Storage time (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| CC | 9.96 ± 0.87b | 6.13 ± 1.87a,b | 11.32 ± 0.95b | 14.14 ± 2.54b |

| AC | 3.67 ± 1.74a | 4.03 ± 1.08a | 7.83 ± 2.90a | 12.83 ± 1.22a |

| AA | 2.81 ± 1.05a | 7.56 ± 2.80c | 11.26 ± 1.90b | 14.95 ± 0.94b |

| AE | 3.96 ± 1.30a | 8.23 ± 1.64c | 9.25 ± 1.28a,b | 15.73 ± 0.08c |

| ΔE D. Capiro |

Storage time (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| CC | 12.19 ± 2.36c | 7.88 ± 1.16c | 10.32 ± 1.60b | 11.34 ± 1.10b |

| AC | 4.60 ± 0.59a,b | 4.82 ± 1.95a | 8.92 ± 1.30a | 8.58 ± 1.37a |

| AA | 3.17 ± 1.87a | 5.09 ± 0.97a,b | 13.98 ± 1.75b | 12.26 ± 0.56b |

| AE | 4.85 ± 0.82a,b | 6.41 ± 2.94a,b | 7.08 ± 1.72a | 11.53 ± 0.23b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).