Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Evaluate under semi-commercial conditions the efficacy of SMB in maintaining the quality of uninjured and apparently infection-free apple and orange fruit during storage

- -

- Compare the preservative performance of three types of fruit during storage

- -

- Unravel the pathological and physicochemical properties of the three kind of fruit as a function of storage periods, based on eight attributes including weight loss, fungal infection, total phenols and flavonoids

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Samples

2.2. Fruit Treatments

2.3. Assessment of Fruit Quality

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quality of Oranges After Cold Storage and Shelf Life

3.1.1. Weight Loss, Disease Incidence and Disease Severity

3.1.2. Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Quality of Red Apples cv. ‘Richared’ After Cold Storage and Shelf Life

3.2.1. Weight Loss and Disease Incidence

3.2.2. Physicochemical Properties

3.3. Quality of Yellow Apples cv. ‘Golden’ After Cold Storage and Shelf Life

3.3.1. Weight Loss, Disease Incidence and Disease Severity

3.3.2. Physicochemical Properties

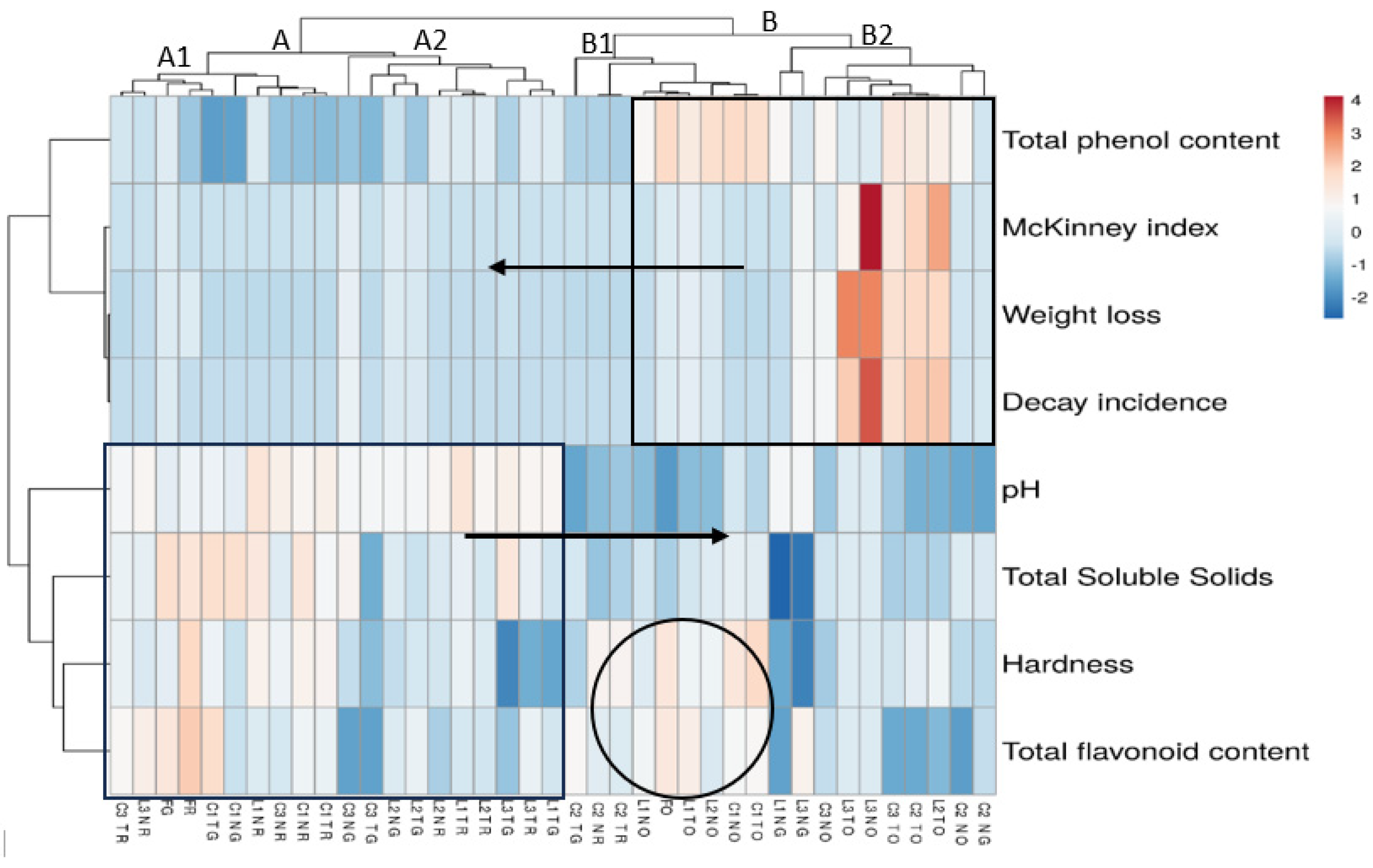

3.4. Heat Map Inference

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Groupement Interprofessionnel des Fruits, Report of 2023. Available online: https://gifruits.com/ (accessed on 11.10.2024).

- FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. SDG Global Food Loss and Waste, 2023. Food Loss and Waste Database | Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- UNEP, Food Waste Index Report 2024. Food Waste Index Report 2024 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme.

- Alaoui, A.; Christ, F.; Silva, V., Vested, A.; Schlünssen, V.; González, N.; … & Geissen, V. Identifying pesticides of high concern for ecosystem, plant, animal, and human health: A comprehensive field study across Europe and Argentina. Sci environ 2024, 948, 174671.

- Triantafyllidis, V.; Kosma, C.; Karabagias, I. K.; Zotos, A.; Pittaras, A.; Kehayias, G. Fungicides in Europe During the Twenty-first Century: a Comparative Assessment Using Agri-environmental Indices of EU27. Water Air Soil Pol 2022, 233, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheilifard, F.; Marzban, A.; Raini, M.G.; Taki, M.; van Zelm, R. Chemical footprint of pesticides used in citrus orchards based on canopy deposition and off-target losses. Sci Environ 2020, 732, 139118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantke, P.; Jolliet, O. Life cycle human health impacts of 875 pesticides. Int J of Life Cycle Assess 2016, 21, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, D.; Bautista-Baños, S. A review on the use of essential oils for postharvest decay control and maintenance of fruit quality during storage. Crop Prot 2014, 64, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Lichter, A.; Gabler, F. M.; Smilanick, J. L. Recent advances on the use of natural and safe alternatives to conventional methods to control postharvest gray mold of table grapes. Postharvest Biol and Technol 2012, 63, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strano, M.C.; Altieri, G.; Allegra, M.; Di Renzo, G.C.; Paterna, G.; Matera, A.; Genovese, F. Postharvest technologies of fresh citrus fruit: Advances and recent developments for the loss reduction during handling and storage. Hortic 2022, 8, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, F.T.; Askarne, L.; Boubaker, H.; Boudyach, E.H.; Aoumar, A.A.B. Control of Gray Mold Disease of Tomato by Postharvest Application of Organic Acids and Salts. Plant Pathol J 2017, 16, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mehyar, G. F.; Al-Qadiri, H. M.; Abu-Blan, H. A.; Swanson, B. G. Antifungal effectiveness of potassium sorbate incorporated in edible coatings against spoilage molds of apples, cucumbers, and tomatoes during refrigerated storage. J Food Sci 2011, 76, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, O.A.; Romanazzi, G.; Smilanick, J. L. Postharvest ethanol and potassium sorbate treatments of table grapes to control gray mold. Postharv Biol Technol 2005, 37, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, F.; Schena, L.; Ligorio, A.; Pentimone, I.; Ippolito, A.; Salerno, M.G. Control of table grape storage rots by pre-harvest applications of salts. Postharvest Biol Technol 2006, 42, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; Roberto, S. R. Applications of salt solutions before and after harvest affect the quality and incidence of postharvest gray mold of ‘Italia’table grapes. Postharvest Biol Technol 2014, 87, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Herrero, C.; Moscoso-Ramírez, P.A.; Palou, L. Evaluation of sodium benzoate and other food additives for the control of citrus postharvest green and blue molds. Postharvest Biol Technol 2016, 115, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Ramírez, P.A.; Palou, L. Preventive and curative activity of postharvest potassium silicate treatments to control green and blue molds on orange fruit. Eur J Plant Pathol 2014, 138, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Ramírez, P.A.; Montesinos-Herrero, C.; Palou, L. Characterization of postharvest treatments with sodium methylparaben to control citrus green and blue molds. Postharvest Biol Technol 2013, 77, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; Ligorio, A.; Nigro, F.; Ippolito, A. Activity of salts incorporated in wax in controlling postharvest diseases of citrus fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol 2012, 65, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palou, L., Ali, A., Fallik, E., Romanazzi, G. GRAS, plant-and animal-derived compounds as alternatives to conventional fungicides for the control of postharvest diseases of fresh horticultural produce. Postharvest Biol Technol 2016, 122, 41-52.

- Fadda, A.; Barberis, A.; D’Aquino, S.; Palma, A.; Angioni, A.; Lai, F.; Schirra, M. Residue levels and performance of potassium sorbate and thiabendazole and their co-application against blue mold of apples when applied as water dip treatments at 20 or 53 C. Postharvest Biol Technol 2015, 106, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbeier, D.T.; Ribeiro, L.T.; Higuchi, M.T.; Khamis, Y.; Junior, O. J. C.; Koyama, R.; Roberto, S. R. SO2-generating pads reduce gray mold in clamshell-packaged ‘Rubi’table grapes grown under a two-cropping per year system. Semina: Ciências Agrárias 2021, 42, 1069-1086.

- Ahmed, S.; Roberto, S.R.; Domingues, A.R.; Shahab, M.; Junior, O.J.C.; Sumida, C. H.; De Souza, R.T. Effects of different sulfur dioxide pads on Botrytis mold in ‘Italia’table grapes under cold storage. Horticulturae 2018, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salur-Can, A.; Türkyılmaz, M.; Özkan, M. Effects of sulfur dioxide concentration on organic acids and β-carotene in dried apricots during storage. Food Chem 2017, 221, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Zoffoli, J. P. Effect of sulfur dioxide and modified atmosphere packaging on blueberry postharvest quality. Postharvest Biol Technol 2016, 117, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F. ; Cui,J.; Wang,C.; Tian,X.; Li, D.; Wang,Y.; Zhang,B.; Feng,L.; Huang, S.; Ma, X. Real-time quantification for sulfite using a turn-on NIR fluorescent probe equipped with a portable fluorescence detector, Chinese Chem Letters 2022, 33, 4219-4222.

- Treesuwan, K.; Jirapakkul, W.; Tongchitpakdee, S.; Chonhenchob, V.; Mahakarnchanakul, W.; Tongkhao, K. Sulfite-free treatment combined with modified atmosphere packaging to extend trimmed young coconut shelf life during cold storage. Food Control 2022, 139, 109099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwah, A.N. Anti-browning methods on fresh-cut fruits and fruit juice: African J Biol Sci 2020, 2, 27-32.

- Allagui, MB.; Ben Amara, M. Effectiveness of Several GRAS Salts against Fungal Rot of Fruit after Harvest and Assessment of the Phytotoxicity of Sodium Metabisufite in Treated Fruit. J Fungi 2024, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanazzi, G.; Feliziani, E.; Santini, M.; Landi, L. Effectiveness of postharvest treatment with chitosan and other resistance inducers in the control of storage decay of strawberry. Postharvest Biol Technol 2013, 75, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, H.H. Influence of soil temperature and moisture on infection of wheat seedlings by Helminthosporium sativum. J Agric Res 1923, 26, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Meth Enzymol 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, A. Zutkhy, Y.; Sonego, O.D.; Kaplunov,T.; Sarig, P.; Ben-Arie, R. Ethanol controls postharvest decay of table grapes.

- Postharvest Biol Technol 2002, 24, 301-308.

- Latifa, A.; Idriss, T.; Hassan, B.; Amine, S. M.; El-Hassane, B.; Abdellah, A. B. A. Effects of organic acids and salts on the development of Penicillium italicum: the causal agent of citrus blue mold. Plant Pathol J 2011, 10, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyousfi, N.; Legrifi, I.; Ennahli, N.; Abdelali, B.; Said, A.; Laasli, S.; Handaq, N.; Belabess, Z.; Ait Barka, E.; Lahlali, R. Evaluating food additives based on organic and inorganic salts as antifungal agents against Monilinia fructigena and maintaining postharvest quality of apple fruit. J of Fungi 2023, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, I.; Rab, A. Influence of storage duration on physico-chemical changes in fruit of apple cultivars. J Animal Plant Sci 2012, 22, 708–714. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, F.; Guillén, F.; Serrano, M.; Valero, D. Physicochemical changes, peel colour, and juice attributes of blood orange cultivars stored at different temperatures. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulao, L. F.; Almeida, D. P.; Oliveira, C. M. Effect of enzymatic reactions on texture of fruits and vegetables. In Enzymes in Fruit and Vegetable Processing, Bayindirli, A. Eds.; CRC Press. Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300, US, 2010, pp. 85-136.

- Ben Amara, M.; Abdelli, S.; De Chiara, M.L.V.; Pati, S.; Amodio, M.L.; Colleli, G.; Ben Abda, J. Changes in quality attributes and volatile profile of ready-to-eat “Gabsi” pomegranate arils as affected by storage duration and temperatures. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45, e14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tao, R.; Ju, Y.; Duan, J.; Xie, Q.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Natural active products in fruit postharvest preservation: A review. Food Front 2024, 5, 2043–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotts, R.A.; Cervantes, L.A.; Mielke, E. A. Variability in postharvest decay among apple cultivars. Plant Dis 1999, 83, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billy, L.; Mehinagic, E.; Royer, G.; Renard, C.M.; Arvisenet, G.; Prost, C.; Jourjon, F. Relationship between texture and pectin composition of two apple cultivars during storage. Postharvest Biol Technol 2008, 47, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Blay, V.; Taberner, V.; Pérez-Gago, M. B.; Palou, L. Control of major citrus postharvest diseases by sulfur containing food additives. Int J Food Microbiol 2020, 330, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butkeviciute, A.; Viskelis, J.; Viskelis, P.; Liaudanskas, M.; Janulis, V. Changes in the biochemical composition and physicochemical properties of apples stored in controlled atmosphere conditions. Appl Sci 2021, 11, 6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zuo, W.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Feng, T.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Analysis of the postharvest storage characteristics of the new red-fleshed apple cultivar ‘meihong’. Food Chem 2021, 354, 129470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado, J.; Rodrigo, M. J.; Zacarías, L. Maturity indicators and citrus fruit quality. Stewart Postharvest Review 2014, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Plaza, L.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Quantitative bioactive compounds assessment and their relative contribution to the antioxidant capacity of commercial orange juices. J Sci Food Agric 2003, 83, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturralde-García, R.D.; Cinco-Moroyoqui, F.J.; Martínez-Cruz, O.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Wong-Corral, F.J.; Borboa-Flores, J.; Cornejo-Ramírez, Y.I.; Bernal-Mercado, A.T.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L. Emerging Technologies for Prolonging Fresh-Cut Fruits’ Quality and Safety during Storage. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, P.; Bianco, M.L.; Pannuzzo, P.; Timpanaro, N. Effect of cold storage on vitamin C, phenolics and antioxidant activity of five orange genotypes [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck]. Postharvest Biol Technol 2008, 49, 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Zheng, E.; Lin, Z.; Miao, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Pang, L.; Li, X. Melatonin Rinsing Treatment Associated with Storage in a Controlled Atmosphere Improves the Antioxidant Capacity and Overall Quality of Lemons. Foods 2024, 13, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adyanthaya, I., Kwon, Y. I., Apostolidis, E., & Shetty, K. Apple postharvest preservation is linked to phenolic content and superoxide dismutase activity. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2009, 33(4), 535–556.

- Sun, J.; Janisiewicz, W.J.; Nichols, B.; Jurick II, W.M.; Chen, P. Composition of phenolic compounds in wild apple with multiple resistance mechanisms against postharvest blue mold decay. Postharvest Biol Technol 2017, 127, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, A.; Cascone, A.; Graziani, G.; Ferracane, R.; Scalfi, L.; Di Vaio, C.; Ritieni, A.; Fogliano, V. Influence of variety and storage on the polyphenol composition of apple flesh. J Agric Food chem 2004, 52, 6526–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, K.; Giannin, B. ; Picchi,V.; Lo Scalzo, R.; Cecchini, F. Phenolic composition and free radical scavenging activity of dif ferent apple varieties in relation to the cultivar, tissue type and storage. Food Chem 2011, 127, 493–500.

- Panche, A. N.; Diwan, A. D., Chandra, S. R. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutri Sci 2016, 5, e47.

- Patil, M.; Murumkar, C. The Classes and Biosynthesis of Flavonoids. In Flavonoids as Nutraceuticals 2024 (pp. 233-251). Apple Academic Press.

- Konstantinou, S.; Karaoglanidis, G. S.; Bardas, G. A.; Minas, I. S.; Doukas, E.; Markoglou, A. N. Postharvest fruit rots of apple in Greece: Pathogen incidence and relationships between fruit quality parameters, cultivar susceptibility, and patulin production. Plant Dis 2011, 95:666-672.

| STORAGE PERIOD (DAYS) | 0 | 20 | +15 SL | 42 | +6 SL | 59 | +6 SL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

WEIGHT LOSS1 (%) |

Untreated |

0 |

0.29 0.32 |

3.10 | 5.33 | 13.34 | 33.26 | 100 |

|

Treated |

21.45 |

65.81 |

68.76 |

61.24 |

100 |

|||

|

DISEASE INCIDENCE (%) |

Untreated |

0 |

0 0 |

0 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 29.2 | 64.3 |

|

Treated |

18.2 |

64.0 |

66.7 |

52.4 |

100.0 |

|||

|

MCKINNEY’S DISEASE INDEX (%) |

Untreated |

0 |

0 0 |

0 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 25.7 |

|

Treated |

10.9 |

41.6 |

53.3 |

31.4 |

80.0 |

|||

|

TSS (%) |

Untreated | 11.5 ± 0.3ab | 12.7 ± 0.1a | 12 ± 0.15a | 12.5 ± 0.1a | 12.4 ± 0.1a | 12.0 ± 0.0a |

nd |

|

Treated |

12.6 ± 0.2a | 12.1+0.02a | 11.6 + 0.1ab | 11.6 ± 0.1ab | 11.5 ± 0.1ab | |||

| PH | Untreated |

3.0 ± 0.01a |

3.7 ± 0.05a | 3.3 ± 0.02a | 3.3 ± 0.02a | 3.1 ± 0a | 3.4 ± 0.02a |

nd |

| Treated | 3.5 ± 0.02a | 3.3 ± 0a | 3.2 ± 0a | 3.2 ± 0.02a | 3.4 ± 0.01a | |||

|

HARDNESS (N) |

Untreated | 15.3 ± 2.4a | 15.2 ± 0.7a | 12.3 ± 0.5b | 13.4 ± 1.5a | 11.0 ± 1.3b | 10.4 ± 1.7b |

nd |

| Treated | 16.2 ± 0.3a | 13.3 ± 2.7a | 13.3 ± 2.9a | 12.7 ± 3.0b | 11.6 ± 1.7b | |||

|

TOTAL PHENOLS (MG GAE /100 G) |

Untreated |

174.0 ± 7.4a |

174.9± 25.2a | 145.8 ± 2.0b |

149.5 ± 2.9b | 171.9.0 ± 29a | 151.1 ± 13.3b |

nd |

| Treated | 171.3 ± 3.9a | 168.9 ±15.8a | 161.8 ± 6.1b | 158.4 ± 3.2b | 163.0 ± 2.8b | |||

|

TOTAL FLAVONOIDS (MG CATECHIN /100 G) |

Untreated |

132.9± 18.2a |

114.8 ± 5.2b | 111.4 ± 2.7b | 41.2 ± 14.5d | 89.8 ± 1.8c | 76.7 ± 14.7c |

nd |

| Treated | 116.0± 14.9b | 127.9 ± 4.7b | 47.8 ± 22.7c | 64.0 ± 2.4c | 48.6 ± 4.2c |

| Storage period (days) | 0 | 20 | +15 SL | 42 | +15 SL | 61 | +15 SL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (%)1 | Untreated |

0 |

0.28 | 1.29 | 0.59 | 1.85 | 0.97 | 2.62 |

| Treated | 0.24 | 1.69 | 0.45 | 2.12 | 0.62 | 2.88 | ||

|

Disease incidence (%) |

Untreated |

0 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

Hardness (N) |

Untreated | 16.3 ± 1.2a | 14.3 ± 2.5a | 14.5 ± 1.4a | 14.3 ± 2.2a | 11.6 ± 1.4b | 13.3 ± 0.6a | 9.3 ± 1.0b |

| Treated | 14.3 ± 0.7a | 13.1 ± 1.1a |

14.3 ± 2.0a |

12.2 ± 1.8a |

13.0 ± 2. 5a |

12.1 ± 1.5a |

||

| TSS (%) | Untreated | 14.2 ± 1.3a | 14.1 ± 0.1a | 14.0 ± 0.0a | 11.3 ± 0.1b | 12.3 ± 0.1b | 12.5 ± 0.1b | 12.8 ± 0.0b |

|

Treated |

13.2 ± 0.2a | 12.8 ± 0.0b | 11.6 ± 0.0b | 12.2 ± 0.0b | 12.9 ± 0.1a | 12.7 ± 0.1a | ||

| pH | Untreated | 4.0 ± 0.03a | 4.2 ± 0.0a | 4.5 ± 0.0a | 3.3 ± 0.0b | 4.2 ± 0.0a | 4.3 ± 0.0a | 4.2 ± 0.0a |

| Treated | 4.3 ± 0.0a | 4.5 ± 0.0a | 3.4 ± 0.0b | 4.2 ± 0.0a | 4.1 ± 0.0a | 4.2 ± 0.0a | ||

|

Total phenols (mg GAE /100 g) |

Untreated | 108.7 ± 0.9c | 116.3± 10.7ab | 129.7 ± 3.1a | 113.0 ± 7.1b | 133.1 ± 3.4a | 116.3 ± 1.9b | 131.2 ± 7.3a |

|

Treated |

103.2 ± 6.4ab | 130.6 ± 1.7a | 111.7 ± 7.5b | 131.2 ± 5.1a | 123.3 ± 5.3ab | 121.1 ±10.7a | ||

|

Total flavonoids (mg catechin /100 g) |

Untreated | 156.8±20.7a | 122.2 ±27.9a | 92.5 ± 6.1b | 96.7 ± 1.8c | 68.2 ± 2.0d | 85.2 ± 16.4c | 104.0 ±1.2c |

|

Treated |

103.7 ± 8.7c | 86.3 ± 5.2d | 91.3 ± 11.1d | 81.7 ± 5.8e | 116.4 ± 5.8c | 127.6 ±18.7b |

| Storage period (days) |

0 | 20 | +15 SL | 42 | +15 SL | 61 | +15 SL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (%)1 | Untreated |

0 |

0.47 | 1.96 | 7.94 | 14.67 | 24.19 | 3.50 |

| Treated | 0.21 | 1.98 | 0.54 | 10.96 | 0.75 | 31.59 | ||

| Disease incidence (%) | Untreated Treated |

0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

7.7 0 |

11.1 10.0 |

23.08 0 |

0 30.0 |

|

Mckinney’s disease index (%) |

Untreated | 0 | 0 | 3.08 | 8.9 | 10.8 | 0 | |

|

Treated |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6.0 |

0 |

18.0 |

|

| Hardness (N) | Untreated | 12.6 ± 1.4a | 11.2 ± 0.7b | 9.2 ± 0.9c | 11.0 ± 1.7b | 11.2 ± 2.2b | 11.1 ± 2.0 b | 7.7 ± 1.1c |

|

Treated |

13.2 ± 1.5a |

9.0 ± 0.6c |

10.7 ± 1.4b |

11.7 ± 2.1b |

10.0 ± 2.1b |

7.6 ± 0.8c |

||

| TSS (%) | Untreated | 14.4 ± 0a | 14.4 ± 0a | 9.3 ± 0.01c | 12.3 ± 0.1b | 12.4 ± 0.0b | 13.5± 0.1a | 14.1 ± 0.5a |

|

Treated |

14.4 ± 0.2a |

12.0 ± 0.0b |

12.2 ± 0.0b |

11.9 ± 0.1b |

10.8 ± 0.1c |

9.7 ± 0.1c |

||

| pH | Untreated | 3.9 ± 0.04a | 3.9 ± 0.04a | 4.1 ± 0.02a | 3.1 ± 0.01b | 4.1 ± 0.01a | 4.1 ± 0.01a | 4.3 ± 0.01a |

|

Treated |

4.0 ± 0.005a |

4.2 ± 0.01a |

3.1 ± 0.01b |

4.1 ± 0.01a |

4.1 ± 0.0a |

4.1 ± 0.01a |

||

|

Total phenols (mg GAE /100 g) |

Untreated | 131.9 ± 6.5b | 93.1 ± 29.4c | 149.6 ± 22.7a | 121.2± 13.4b | 119.6 ± 11.5b | 107.5 ± 2.8c | 113.7±4.9c |

|

Treated |

89.9 ±13.5d | 130.6 ± 40.0a | 113.8 ± 6.9c | 108.9 ± 17.4c | 102.0 ± 21.0c | 128.5±7.1b | ||

|

Total flavonoids (mg catechin /100 g) |

Untreated | 136.4±1.2a | 79.0 ± 3.5c | 43.5 ± 5.2d | 77.1 ± 2.9c | 91.7 ± 16.4b | 122.5 ± 6.9a | 43.2 ± 1.8d |

|

Treated |

145.7 ± 3.1a | 82.5 ± 11.6c | 117.5 ±24.5a | 103.7 ± 19.3b | 62.0 ± 4.7d | 44.3±11.6d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).