Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

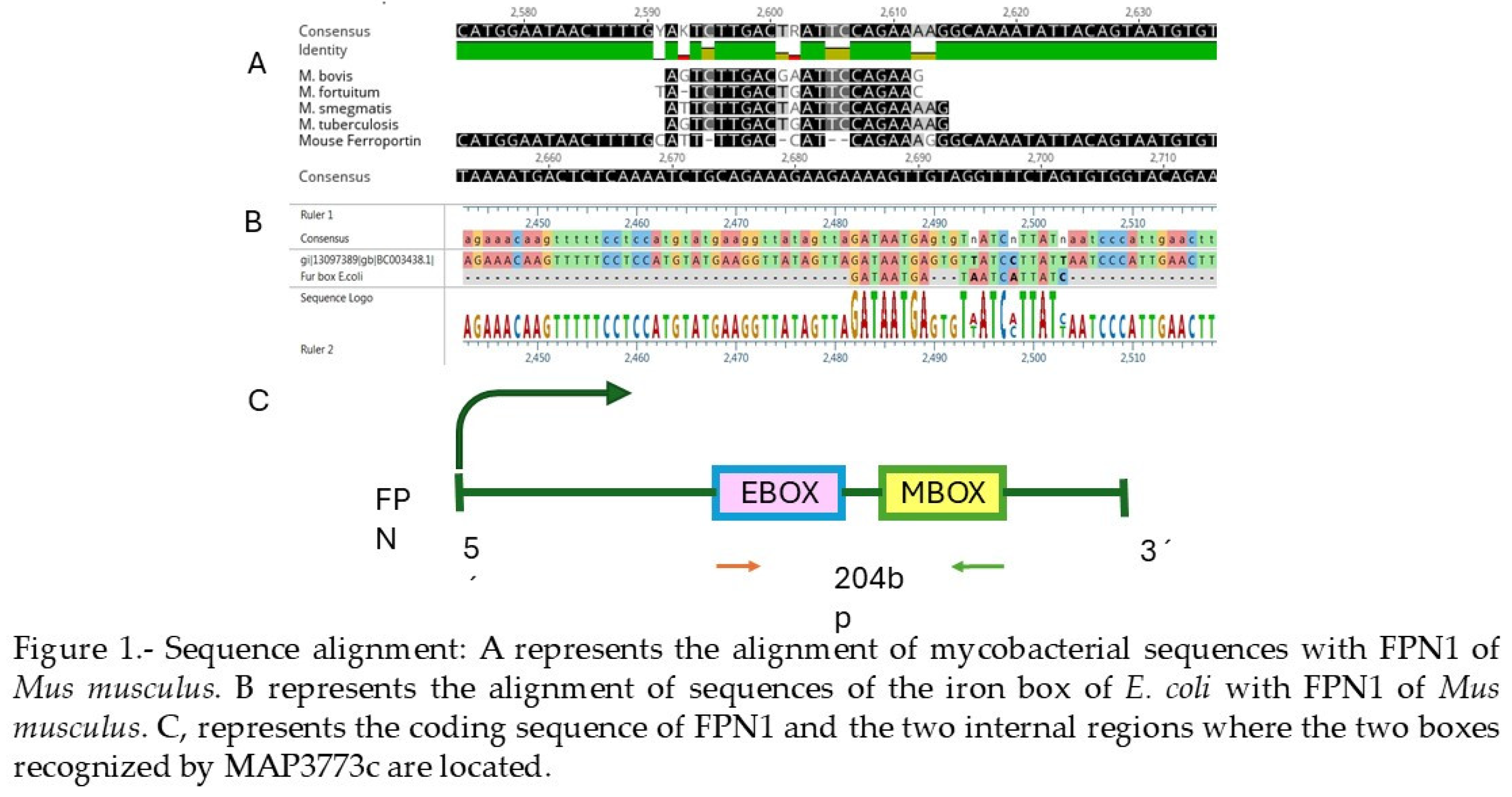

2.1. Alignments

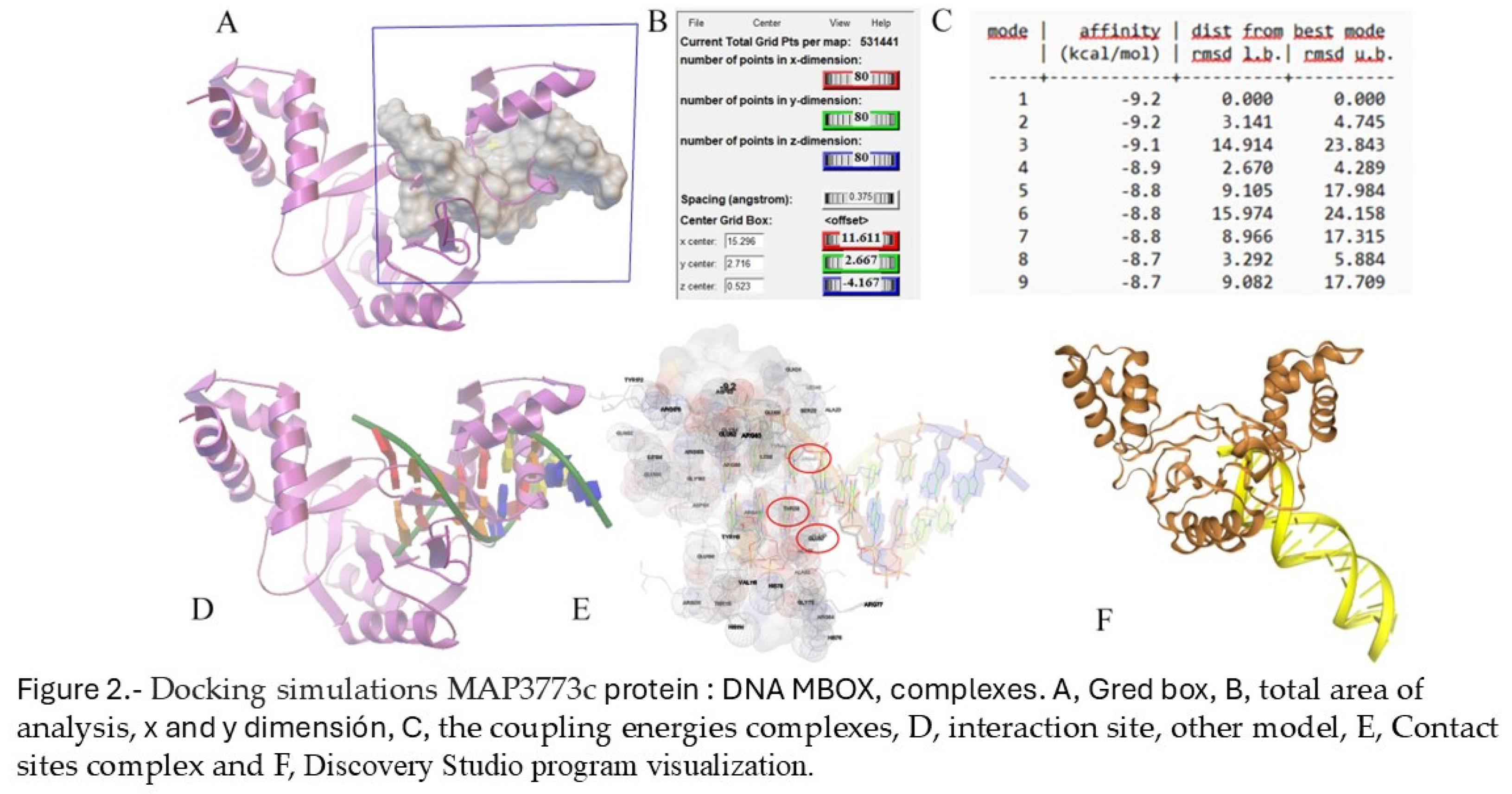

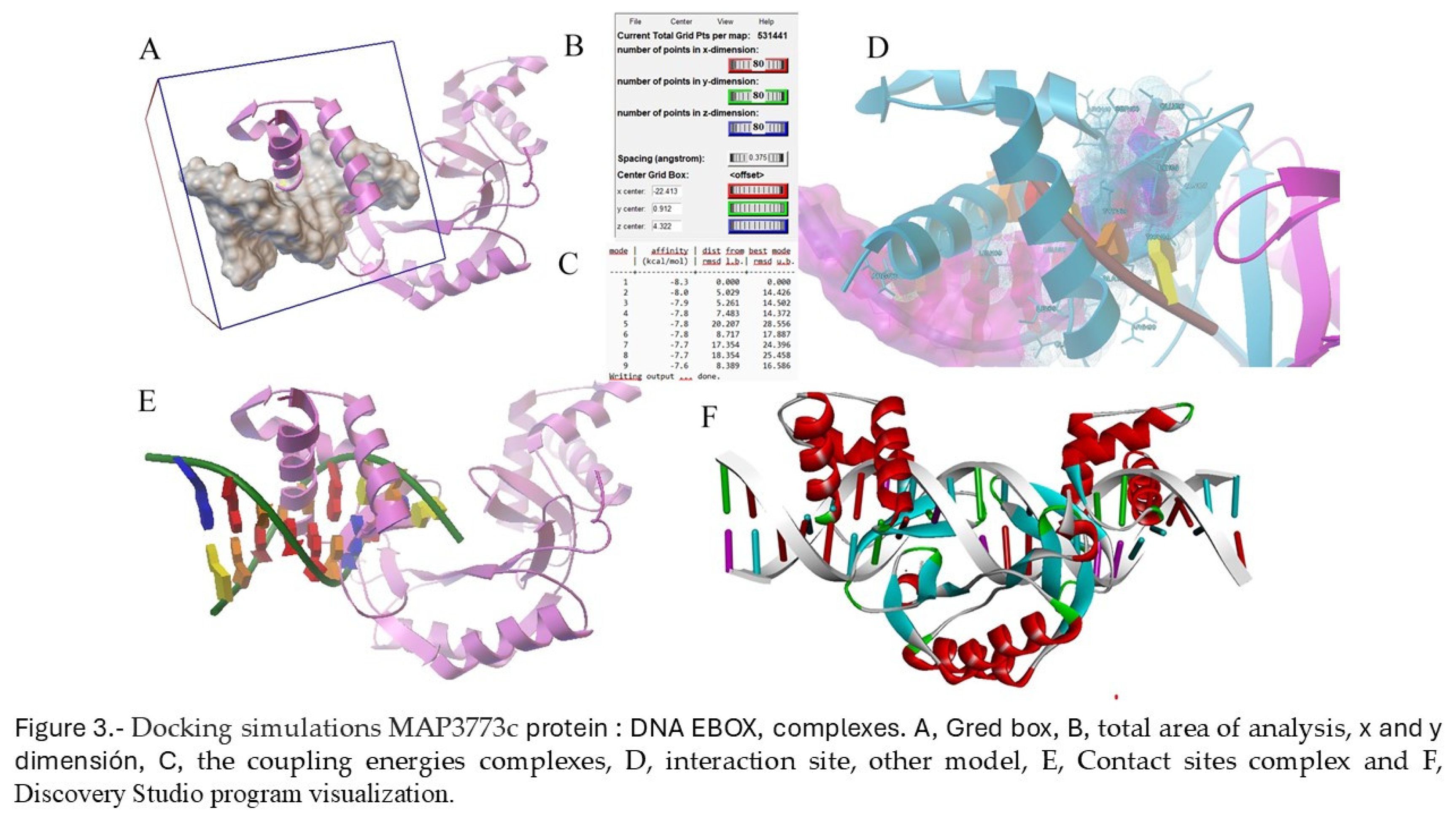

2.2. Docking

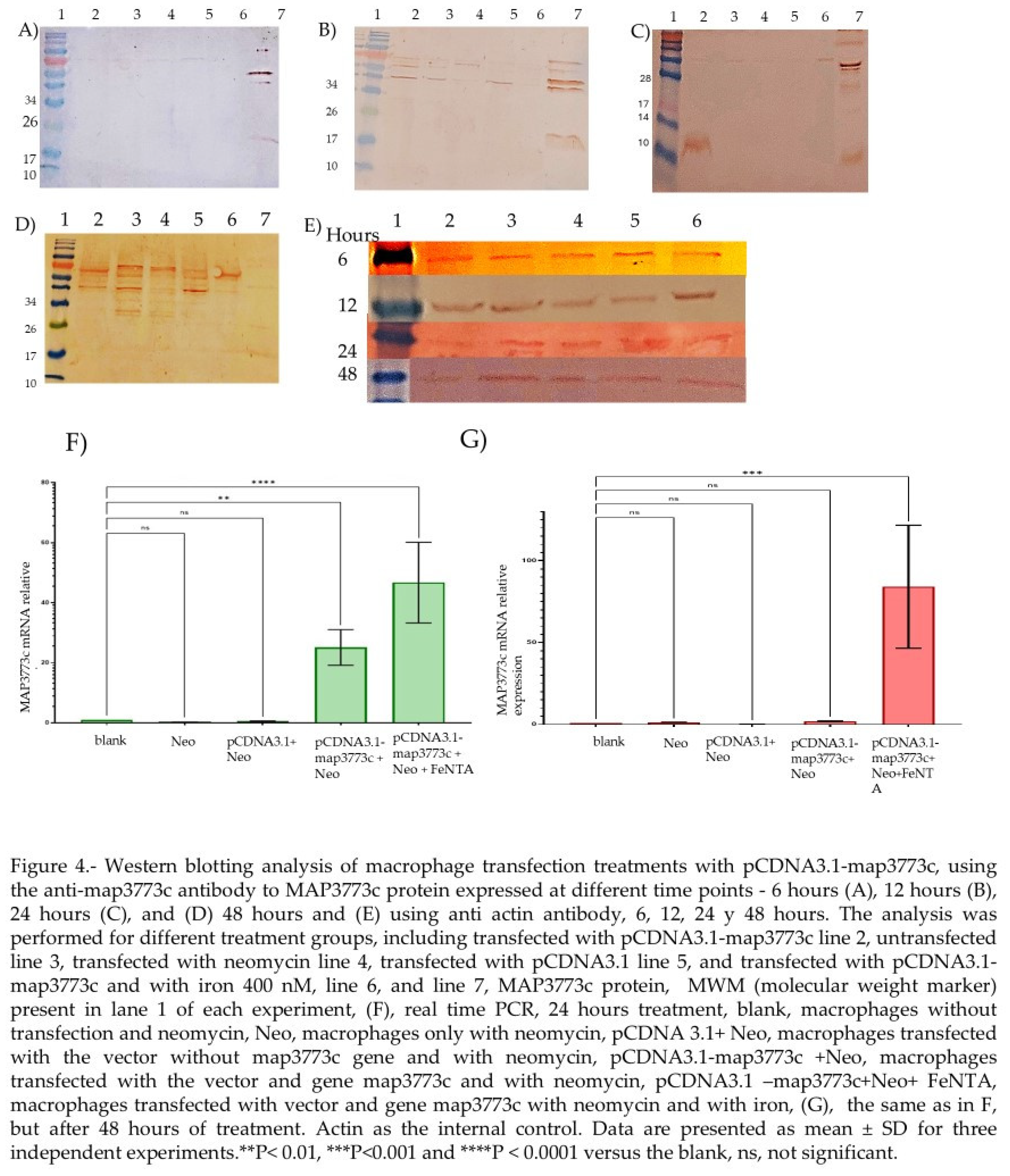

2.3. MAP3773c Purification Protein

2.4. The Expression of mRNA and MAP3773c Protein

2.4. EMSA

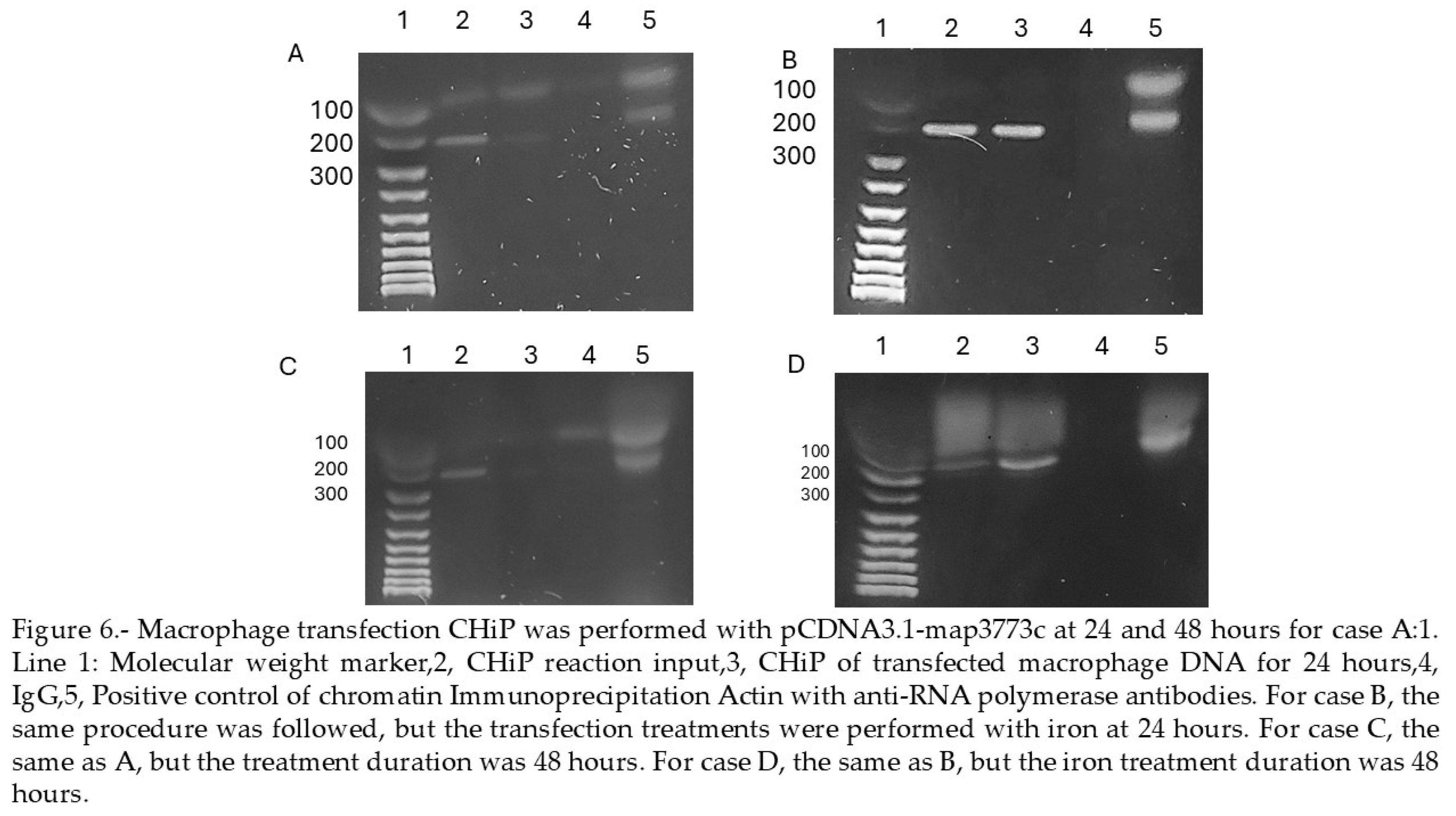

2.5. MAP3773c Binding in the FPN1 Coding Region

3. Discusion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Alignments for the Location of Iron Boxes in the Mouse FPN Gene

4.2. Bacterial Strain

4.3. Docking of the Fur boxes

4.4. EMSA

4.5. Rabbit Immunization

4.6. Cloning pCDNA 3.1 and Map3773c Gene

4.7. Sequencing

4.8. Macrophages Culture J774 A.1

4.9. Transfection of Macrophages J774A.1 with pCDNA-map3773c

4.10. qRT-PCR

4.10.1. Extraccion de RNA

4.10.2. Reverse Transcription

4.10.3. Real-Time PCR.

4.11. Western- Blotting

4.12. CHiP

4.13. PCR Punto Final

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganz, T. Cellular iron: ferroportin is the only way out Cell Metab 2005, 1, 155-157. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Brownlie, A.; Zhou, Y.; Shepard, J.; Pratt, S.J.; Moynihan, J.; Paw, BH.; Drejer, A.; Barut, B.; Zapata, A.; Law, TC.; Brugnara, C.; Lux SE, Pinkus, GS.; Pinkus, JL.; Kingsley, P.D.; Palis, J.; Fleming, MD.; Andrews, NC.; Zon, LI. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 2000, 17,776-81. [CrossRef]

- Knutson, M.D.; Vafa, M.R.; Haile, D.J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron loading and erythrophagocytosis increase ferroportin 1 (FPN1) expression in J774 macrophages. Blood 2003, 102,4191-7. [CrossRef]

- Park, B. Y., & Chung, J. 2008. Effects of various metal ions on the gene expression of iron exporter ferroportin-1 in J774 macrophages. Nutrition research and practice 2008, 2, 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Prescott, R.; Cherayil, B. J. The commensal bacterium Bacteroides fragilis down-regulates ferroportin expression and alters iron homeostasis in macrophages. Journal of leukocyte biology 2019, 106, 1079–1088. [CrossRef]

- Van Zandt, K. E.; Sow, F. B.; Florence, W. C.; Zwilling, B. S.; Satoskar, A. R.; Schlesinger, L. S.; & Lafuse, W. P. The iron export protein ferroportin 1 is differentially expressed in mouse macrophage populations and is present in the mycobacterial-containing phagosome. Journal of leukocyte biology 2008, 84, 689–700. [CrossRef]

- Landeros-Sanchez, B.; Gutiérrez-Pabello.J.A.; Medina - Basulto G. E.; Rentería E. T.; Díaz- Aparicio, E.; Oshima, S. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis down-regulates mRNA expression of iron-induced macrophage Ferroportin 1. Veterinaria México OA 2016. 3, 1. [CrossRef]

- Jończy, A.; Mazgaj, R.; Smuda, E.; Żelazowska, B.; Kopeć, Z.; Starzyński, R. R.; & Lipinski, P. The Role of Copper in the Regulation of Ferroportin Expression in Macrophages Cells, 2021, 10(9), 2259. [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Zhao, R.; Wu, R. An overview of the prediction of protein DNA-binding sites. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 5194-215. [CrossRef]

- Shoyama, F.M.; Janetanakit, T.; Bannantine, J.P.; Barletta, R.G.; Sreevatsan, S. Elucidating the Regulon of a Fur-like Protein in Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP). Front. Microbiol 2020, 11, 598. [CrossRef]

- Eckelt, E.; Jarek, M.; Frömke, C.; Meens, J.; Goethe, R. Identification of a lineage specific zinc responsive genomic island in Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. BMC Genomics 2014, 15,1076. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Guevara, E.; Gutiérrez-Pabello, J. A.; Quintero-Chávez, K.; Brito-Perea, M. D. C., Hurtado-Ayala, L. A.; Ibarra-Molina, G.; Cortez-Hernández, O., Dueñas-Mena, D. L.; Fernández-Otal, Á.; Fillat, M. F., & Landeros-Sánchez, B. In Silico and In Vitro Analysis of MAP3773c Protein from Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Biology 2022, 11(8), 1183. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Rathnaiah, G.; Zinniel, D. K.; Barletta, R. G.; Bannantine, J. P.; Huebner, M. & Sreevatsan, S. The Fur-like regulatory protein MAP3773c modulates key metabolic pathways in Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis under in-vitro iron starvation. Scientific reports, 2024 14(1), 8941. [CrossRef]

- Escolar, L.; Pérez, M.J.; de Lorenzo, V. Opening the Iron Box: Transcriptional Metalloregulation by the Fur Protein. J. Bacteriol 1999, 181, 6223–6229. [CrossRef]

- Sala, C.; Forti, F.; Di Florio, E.; Canneva, F.; Milano, A.; Riccardi, G.; Ghisotti, D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FurA autoregulates its own expression. Journal of bacteriology. 2003, 185, 5357–5362. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004, 25(13):1605-12. [CrossRef]

- Michel, F. S. Python: A Programming Language for Software Integration and Development. J. Mol. Graphics Mod 1999, 17, 57-61.

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack A. F. and Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 23, 61(8), 3891-3898. [CrossRef]

- Huang S.Y.; Zou X. A knowledge-based scoring function for protein-RNA interactions derived from a statistical mechanics-based iterative method. Nucleic Acids Res 2014,42-55. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Huang S.Y. HDOCK: a web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(1),365-373. [CrossRef]

- Biovia, D.S. 2019, Discovery Studio Visualizer, San Diego, accesed in december 2023.

- Veres-Székely, A.; Pap, D.; Sziksz, E.; Jávorszky, E.; Rokonay, R.; Lippai, R.; Tory, K.; Fekete, A.; Tulassay, T.; Szabó, A. J.; & Vannay, Á. Selective measurement of α smooth muscle actin: why β-actin can not be used as a housekeeping gene when tissue fibrosis occurs. BMC molecular biology 2017, 18(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Abboud, S.; Haile,D.J. A Novel Mammalian Iron-regulated Protein Involved in Intracellular Iron Metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275 (26), 19906-19912. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Brownlie, A.; Zhou, Y.; Shepard, J.; Pratt, S.J.; Moynihan, J.; Paw, B.H.; Drejer, A.; Barut, B.; Zapata, A.; Law, T.C.; Brugnara, C.; Lux, S.E.; Pinkus, G.S.; Pinkus, J.L.; Kingsley, P.D.; Palis, J.; Fleming, M.D.; Andrews, N.C.; Zon, L.I. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 2000, 17;403(6771),776-81. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, I.H.E.; Gildhorn, C.; Böning, M.A.L.; Kulow V.A.; Steinmetz, I.; Bast, A. Burkholderia pseudomallei modulates host iron homeostasis to facilitate iron availability and intracellular survival. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018,12(1). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G,; Adhikrao, P.A. Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis iron-scavenging tools: a recent update on siderophores inhibitors. RSC Med Chem. 2023, 14(10),1885-1913. [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, E.; Bes, M.T.; Peleato, M.L.; Fillat, M.F. Fur-like proteins: beyond the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) paralog. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2021; 701,108770. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Ch.; Bo, W.; Yuhuan, H.; Weiting W.; Yudi, Z.; Samina, S.; Panting, L.; Yonghua, D.; Mengli, X.; Guoquan, H.; Mingxiong, H. Transcription factor shapes chromosomal conformation and regulates gene expression in bacterial adaptation, Nucleic Acids Research, 2024, 52 (10) 5643–5657. [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhou, C.; Shi, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, R.; & He, X. Nuclear transcription factor Nrf2 suppresses prostate cancer cells growth and migration through upregulating ferroportin. Oncotarget 2016, 7(48), 78804–78812. [CrossRef]

- Jakubec, D.; Skoda, P.; Krivak, R.; Novotny, M.; & Hoksza, D. PrankWeb 3: accelerated ligand-binding site predictions for experimental and modelled protein structures. Nucleic acids research 2022,50 (1), 593–597. [CrossRef]

- Jendele, L.; Krivak, R.; Skoda, P.; Novotny, M.; & Hoksza, D. (2019). PrankWeb: a web server for ligand binding site prediction and visualization. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47(1), 345–349. [CrossRef]

- Krivák, R., Hoksza, D. P2Rank: machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. J Cheminform 2018, 10, 39. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.A.; Lopez-Gomollon, S.; Muro-Pastor, A.; Valladares, A. Bes. MT.; Peleato, M.L.; and Fillat, M.F. Interaction of FurA from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 with DNA: a reducing environment and the presence of Mn(2+) are positive effectors in the binding to isiB and furA promoters. Biometals 2006,19, 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Metaane, S.; Monteil, V.; Ayrault, S.; Bordier, L.; Levi-Meyreuis, C.; & Norel, F. The stress sigma factor σS/RpoS counteracts Fur repression of genes involved in iron and manganese metabolism and modulates the ionome of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PloS one 2022, 17(3). [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Roe, J.H. The zinc-responsive regulator Zur controls a zinc uptake system and some ribosomal proteins in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Bacteriol 2007,189(11):4070-7. [CrossRef]

- Forero, M.E.; Marin M.; Llano, I.; Moreno, H.; Camacho, M. Leishmania amazonensis infection induces changes in the electrophysiological properties of macrophage-like cells. J.Membr Biol. 1999. 170:173-180. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).