1. Introduction

The dairy basin of the Cajamarca region, located in the northern highlands of Peru, ranks first in milk production (401 010 tonnes per year), representing 19% of national production [

1]. In this region, producers base their cattle feed on cultivated pastures such as ryegrass ecotype Cajamarquino

(Lolium multiflorum L.

), white clover

(Trifolium repens L.

), and Kikuyo

(Pennisetum clandestinum, the latter considered by some producers as an alternative pasture and in many places in the highlands an invasive species [

2]. Kikuyu can help recover salinised areas, as it is a plant with phytoremediation capacity [

3,

4,

5]. Kikuyo is highly resilient to adverse environmental conditions, making it a species of interest in the face of new climate variability scenarios, especially in high Andean areas [

6]. Kikuyo is a widespread species throughout the high Andean zone of northern Peru, basically associated with ryegrass-clover pastures [

7], with levels of composition ranging from 2.8% to 39. 78 % in the composition of the forage floor [

8,

9], being considered an excellent alternative to face and be a food base for different species of herbivorous animals, for being a nutritional source of easy access, as it is used in other environmental conditions of South America, due to its nutritional contribution and high digestibility [

10,

11], in addition to the palatability for livestock [

12].

Kikuyu grass produces an average of 15.8% crude protein (CP) in dry matter (DM) and an availability of 3 335 kg DM. ha

-1 per grazing cycle, with a residue of 2 032 kg DM ha

-1 [

13]. The nitrogen fertilisation required by Kikuyu is between 50 and 70 kg of nitrogen per ha/crop, generating a significant impact on soil structure and the content of specific physicochemical characteristics that help better absorption of the chemical supplement, which favours the quality and production of green forage [

14]. In addition, organic fertilisation (poultry manure) and chemical fertilisation at a rate of 200 kg N

2. ha

-1 in Kikuyu positively influence (p<0.05) regeneration at the first cutting frequency, plant height of 47.12 cm and biomass of 6.22 Mg DM. ha

-1, while the ashes produced on average reach CP 19.34 % to 20.04 % [

15] and can reach up to 25 % [

16,

17]. For drought conditions,

Pennisetum clandestinum can achieve 10.07 % ash, 60.82 % carbohydrate, 15.24% CP and 30.42 % crude fibre (CF) [

18]. Meanwhile, in the rainy season in the South American highlands, 14.6 % CP, 11.1 % ash, 48.3 % NDF and 29.7 % CDF are obtained [

19]; in Cajamarca, a contribution of 17.35 % CP, 10.94 % ash and 38.02 % NDF is reported [

7].

Among the most representative exotic species of the highlands, Kikuyo is a perennial C4 grass whose growth form is spreading on the surface or under the ground through stolons or rhizomes, and it can reach heights of approximately 50 to 60 cm. In comparison, the leaves can measure between 4.5 cm to 20 cm long and 6 to 15 mm wide [

20]. It is highly tolerant of acidic and salty soil conditions [

21]. When 150 kg of poultry manure plus 50 kg of nitrogen (N

2). ha

-1 as urea is used, it improves nutrient uptake and increases pasture persistency, yield and nutritional quality, directly affecting milk response and reducing costs per kg of milk [

22]. In addition, Kikuyu has protein levels from 15.04 % to 17.77 % in an open field or with

Alnus acuminata systems in 3 m x 5 m distances, considering that the association between these species has a positive effect on forage quality, thus helping to a better digestibility [

23].

The frequency of defoliation does not modify the yield components (proportion of leaves, sheaths, stems and dead material); the values of neutral detergent fibre (NDF) and acid detergent fibre (ADF) are similar in the frequency of defoliation, considering that their ideal consumption should be between 4.5 to 6 leaves per head, respecting the residue height of 5 cm [

24]. Under the conditions of the northern zone of Cajamarca, the sustainability of

Pennisetum clandestinum for use in livestock farming in the northern zone of Peru under highland conditions was evaluated. The effect of nitrogen levels, use of organic matter, frequency of cutting phenology, and distance to live cypress fences (

Cupressus lusitanica) on biomass production, growth rate (kg and mm) and chemical composition of

Pennisetum clandestinum was determined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

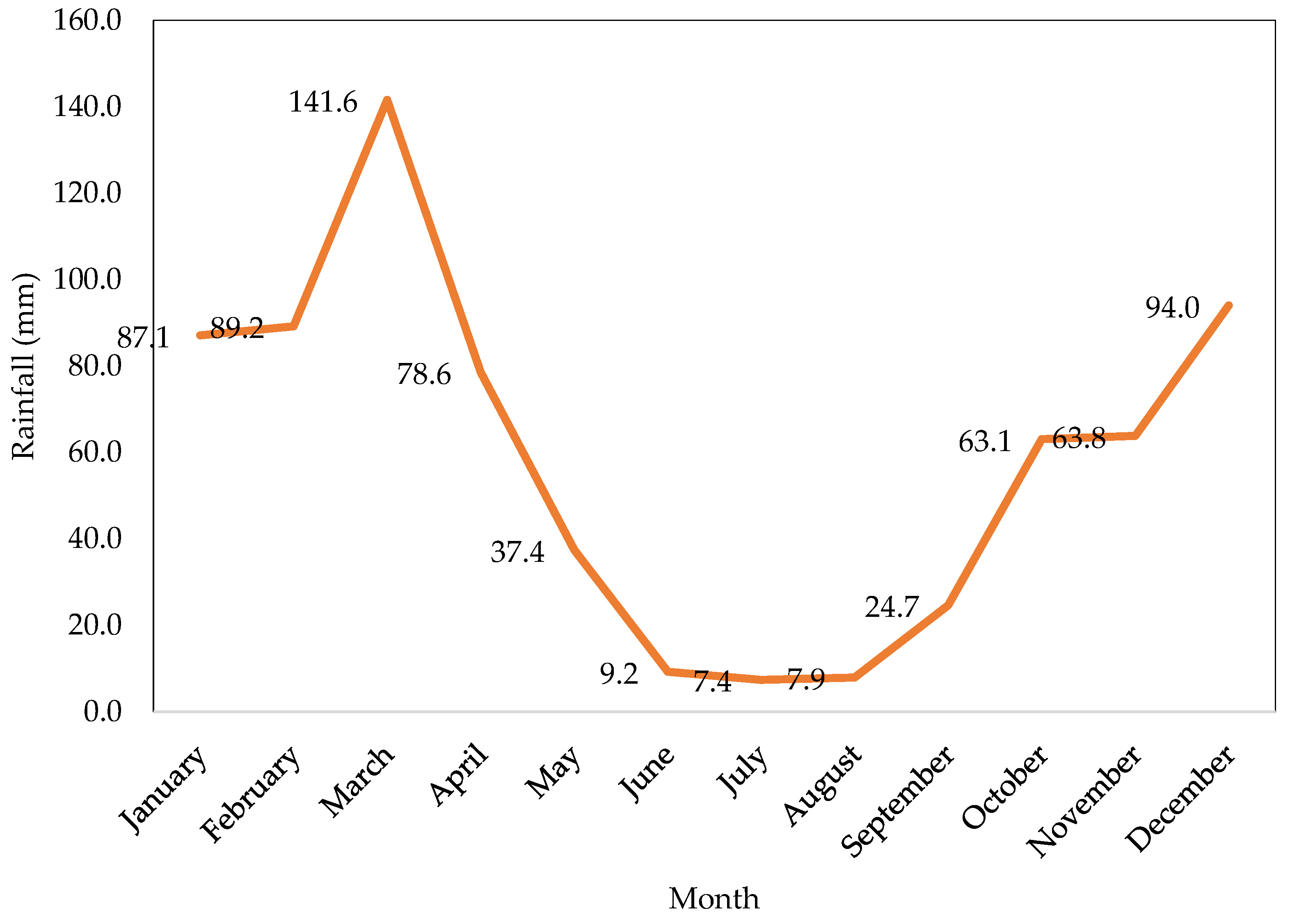

The present work was developed at the Centro de Investigación y Promoción Pecuaria (CIPP) ‘Huayrapongo’ of the Facultad de Ingeniería en Ciencias Pecuarias of the Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, located in Los Baños del Inca district, Cajamarca province, Peru (Latitude 07°09′49″ S, Longitude 78°30′00″ W) located at 2718 masl. The work was carried out between November 2022 and December 2023 in an area of 02 hectares of naturalised Kikuyu pasture. The study area presents a dry, temperate and sunny climate during the day. The nights it is cold, with temperatures fluctuating between 4 °C and 23 °C and rainfall in the last 20 years has been from 493.4 to 908.8 mm with an annual average of 704 mm per year, Source: Senamhi, 2024 [

25] (

Figure 1).

2.2. Soil Characteristics and Preparation of the Experiment

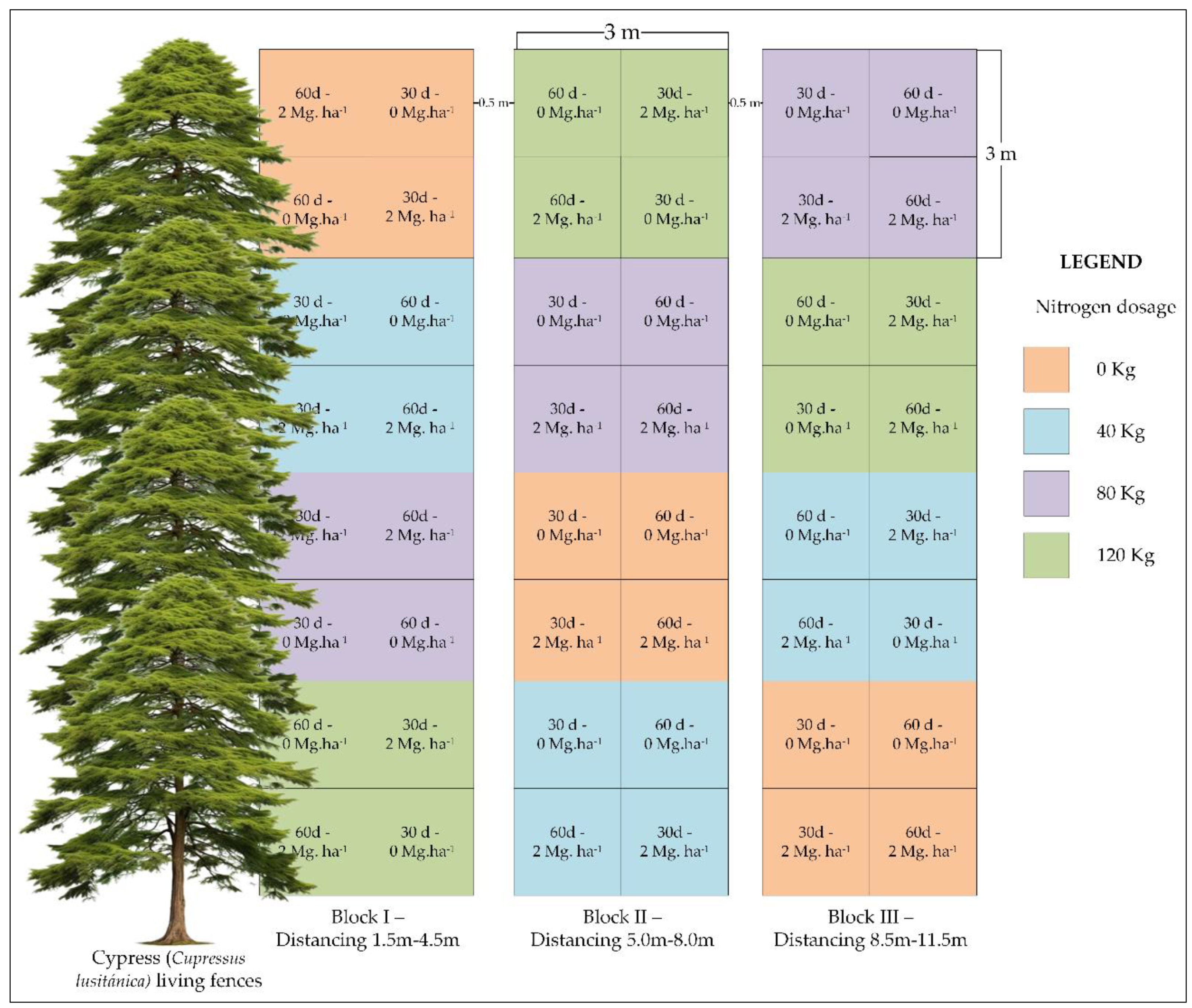

For the development of this research, two experiments were used; the first one (EXP1) was carried out under a split-plot design with a randomised block plot structure to minimise errors and maximise the precision of the results. A total of 12 experimental units were installed (each with a dimension of 3 m x 3 m, area of 9 m

2), distributed in 3 blocks, generating 48 subplots; this distribution ensures the representativeness and comparability of the data collected. The study of the cultivar spacing from the cypress living fence was also considered, considering the blocks as a study factor. Soil analysis was carried out one month before the start of the homogenisation cut and the beginning of evaluations in the experimental area to evaluate its fertility and to know the nutritional conditions. Ten representative soil samples were collected from the experimental area and sent to the Soil, Water and Foliar Laboratory (LABSAF) of the Baños del Inca Agrarian Experimental Station INIA-Cajamarca [

26]. It was determined that the experimental soil obtained pH+ = 7.6; Organic matter (%) = 9.5; Phosphorus (ppm) = 29.02; Potassium (ppm) = 360; Electric conductivity (mS/m) = 32.1

Naturalised and established Pennisetum clandestinum was used as biological material. The cut of homogenisation of the vegetal cover was carried out, then 07 days later, the Organic Matter (OM) was applied - commercial chicken manure with a composition of 3.4 N2 - 3.05 P2O5 - 2.0 K2O, and as chemical fertiliser urea, triple Calcium Superphosphate and Potassium Chloride were used, to cover the demand of 80 N2- 75 P2O5 - 45 K2O which is the recommendation of the Laboratory, according to the results of the soil analysis.

Three doses of Nitrogen (N2) plus a control (T0) were used considering four treatments: 0%, 50%, 100% and 150% of the recommendation (80 N2), in interaction with the application of OM (2 Mg per hectare of poultry manure) and no application and with a cutting frequency of 30 and 60 days; the blocks were considered as distances to the live cypress (Cupressus lusitanica) fences that between the trees had a distance of three metres and perpendicularly Block I, it was located between 1. 5 m and 4.5 m, Block II between 5.0 m and 8.0 m, and Block III between 8.5 m and 11.5 m to the trunk of the trees which measured on average 8 m to the crown with a branch radius of 5.5 m and pruned to 2.5 m from the base.

The second experiment (EXP2) was carried out in randomised complete blocks and was evaluated during 06 months from March to October 2023; in this work, the purpose was to determine the dry matter yield, plant length, stolon density per square meter and the growth ratio per day in dry matter production and plant development. It was to establish the relationship between phenology and productivity of the pasture under highland conditions. Fertilisation of EXP2 was carried out according to the requirements given in the soil analysis, using the level of 80 kg of nitrogen and the application of 2 Mg of poultry manure.

2.3. Conduct the Experiment

After the plots and subplots were separated, each treatment was randomly assigned (

Figure 2). The irrigation system was activated in May 2023, both for EXP1 and EXP2, due to the absence of rainfall, as shown in

Figure 2. Irrigation was carried out with a frequency of 20 days with a variation of 05 days, according to the disposition of all the irrigation canal beneficiaries in the area. As recommended, each subplot was fertilised with organic matter at the beginning of the experiment, as well as triple superphosphate and potassium chloride, while nitrogen was dosed to be applied in each cut.

After EXP 1 was established, the crop was cleaned with mechanical weeding to remove weeds, mainly the presence of cow's tongue (Rumex crispus), and the same action was carried out in EXP 2 before the first evaluation.

2.4. Sample Collection and Parameter Evaluation

The green forage yield was determined with the methodology of the quadrant of a square meter to evaluate the yield, and then the totality of each subplot was cut (

Figure 3), then it was weighed in a digital balance; two samples were taken, the first one to determine the dry matter that was carried out in the Laboratory of pastures and forages of the Faculty of Engineering in Livestock Sciences of the National University of Cajamarca and the second one 200 grams were taken for the proximal analysis in the LABSAF. The cut was carried out, leaving a 5 cm high remnant from the base of the soil. The evaluation was conducted during six consecutive cuts to minimise the experimental error and achieve a one-year evaluation.

In EXP2, samples were taken at 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 days. Where plant height was measured, a one-metre quadrat was used to measure plant density and height in cm. The cuttings were then replicated at least twice for 75 and 90 days to have more replicates.

Once evaluated in each subplot, green forage and dry matter production were estimated as yield per hectare; also, with the values of dry matter and protein percentage, the annual yield was estimated.

2.5. Chemical Composition

At the same time as obtaining the dry matter percentage, each 200 g sample was dehydrated at 65°C for 24 hours and then sent to LABSAF. The methodology used for protein analysis was AOAC 984.13. [

27], for ethereal extract, AOAC 920.39 [

28], AOAC 962.09 for crude fibre, and AOAC 942.05 for ash [

29].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data acquired from the field sheets were digitised and stored in an orderly manner in the field book, then transferred to an Excel workbook (Office 365, Microsoft, personal licence). Tests for compliance with assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were then performed using Levene's test (p<0.05) and Shapiro Wilks test (p<0.05), respectively, for each response variable. To compare the differences between the levels of nitrogen doses, cutting frequency, organic matter application and distance to the living fence, simple (ANOVA) and multiple (MANOVA) analyses of variance were carried out for the productive yield, nutritional value and growth rate variables. Statistical analyses were performed with Infostat Version 2020e software [

30]. The Duncan test (p<0.05) was used to compare the means of the different factors.

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Phenological Development

In the high Andean region of Cajamarca, Peru, some studies of the floristic composition have been carried out, considering the 24.2 % proportion of

Pennisetum clandestinum [

31]. Therefore, the overall sustainability of livestock farming in the region needs study.

Table 1 shows the parameters of green forage yield per cut and year and dry matter yield per cut and year; additionally, the estimated annual protein production was compared; for this purpose, multiple variance analysis was performed for the grouping in each factor evaluated. Significant differences were found between groups for the level of nitrogen used in fertilisation on yield. It has been established that the application of 120 kg N

2 ha

-1 increases protein production significantly to 3 454.53 kg ha

-1. yr

-1, this generates a significant contribution of nitrogen to the soil, increasing soil quality [

14], protein, a dispensable requirement in livestock nutrition for milk production, improves the productivity response [

32]. As one of the main dairy production basins in the northern macro-region of Peru, cattle feeding is based on grazing [

33]. Moreover, it is a source of income for the local economy. Therefore, with this study, the beginning of improving the management conditions of Kikuyu grass under conditions similar to the present study is being considered since it is known that the species adapt to drought, frost, and soil conditions [

33]. [

34]. A significant effect (p<0.0001) of Kikuyu grass spacing to the base of Cypress

(Cupressus lusitanica) trees under live fences was determined. It was identified that each spacing range influences the annual biomass yield. This could be due to shade, which affected productivity in the first Block [

35], due to the density of the 3 m living fence.

The application of organic matter did not influence the yield parameters, but an effect associated with the levels of green forage per year was found (

Table 1); this considers that with MANOVA, two different groups were located, which leads to consider that the application of organic matter will always positively affect Kikuyu crops [

15] especially in the provision of green fodder. On the other hand, when evaluating the cutting frequency, it has been established that there are differences between 30 and 60 days, and the age of cutting or grazing influences the quality as it is known in the area [

7]. However, protein values are not taken into account when deciding the time of use by farmers; our results show that there are no differences in biomass yield per year, but there is an impact on the quality of the forage or pasture provided to the animals [

23]. As a monoculture or in association with silvopastoral systems, Kikuyu is more resistant to the conditions of the highlands in the northern zone, considering that the growth rate is influenced by its morphological nature of being stoloniferous [

12].

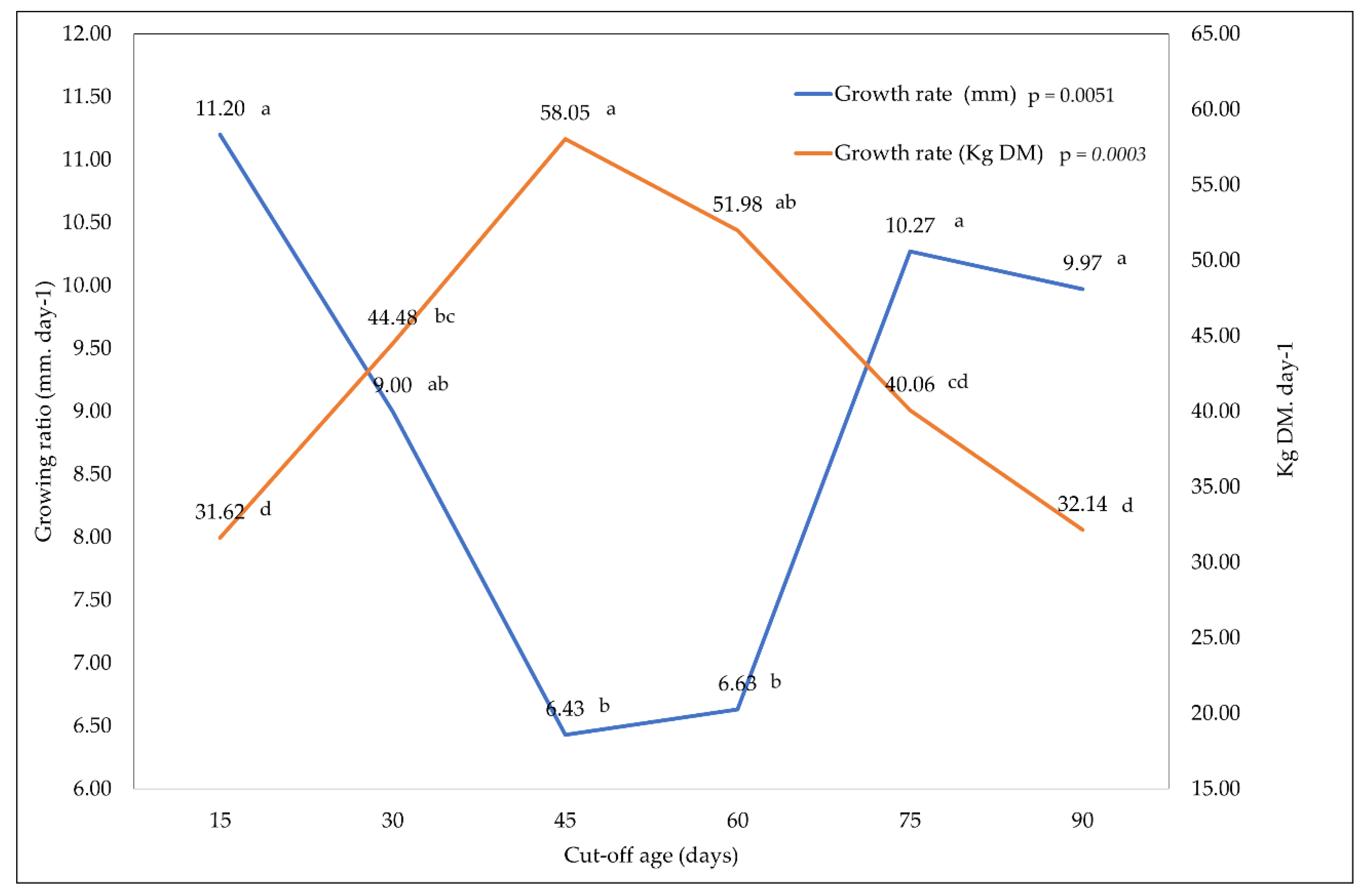

Table 2 shows the phenological growth of Pennisetum clandestinum according to the frequency of cutting; it was found that its dry matter yield per year in EXP2 at 30 days was 16 236 kg DM ha

-1. yr

-1 with similar values to EXP1, which was 14 591.95 kg DM ha

-1. yr

-1. Comparing that it is on the same farm, very similar yields are found. Meanwhile, the length of the plant does have a continuous growth in the Kikuyu evaluated, reaching 89.5 cm after 90 days, with each of the frequencies being statistically different (p<0.0001).

Yield per cut was found to be similar for cut-off ages of 45, 60, 75 and 90 days, which shows that crop development stabilises at 45 days as seen in the daily dry matter accumulation per hectare of 58.05 kg ha

-1. day

-1 (

Figure 4).

3.2. Chemical Composition

Table 3 details the values of crude protein (CP), ash, ether extract, crude fibre (CF) and nitrogen-free extract (NIFEX) for the factors of nitrogen dose, cutting frequency and organic matter application. The nitrogen fertiliser dose influences the chemical composition. [

15]. The cutting frequency affects the chemical composition of

Pennisetum clandestinum; this can affect digestibility [

36]. The organic matter influences the levels or percentages of CP, ash, FC, Ether and NIFEX

The values found in the experiment for CP when no nitrogen or 50% (40 kg. ha

-1) of the recommendation is used are similar to the 17.25% obtained at 30 days reported by Vallejos-Cacho et al. (2024) [

7].

3.3. Diagnosis

Livestock farming in Peru is a significant activity, according to CENAGRO 2012 [

37], there are 2.3 million agricultural units in Peru, 68% of which are in the highlands and 19% in the jungle. [

38]. We know that the current national situation points to a total reform of production systems due to the lack of sustainability of intensive systems. Therefore, to satisfy the national demand for meat and milk and achieve global competitiveness, pasture production processes per hectare must be optimised [

39].

Pennisetum clandestinum has the potential to ensure livestock productivity, as we have visualised the results. In addition, in livestock farming in the highlands, especially in the hillside and countryside conditions, the forage floor is associated with silvopastoral systems under different silvopastoral arrangements, with different species and modalities. [

2,

40]. In another approach, using organic fertilisation in pastures is a sustainable option in the biological, economic and environmental sense, so its application should be massified due to its biological benefits [

41,

42,

43]. This is the response to evaluating the application of poultry manure in Kikuyo pastures with grazing cows [

22].

Resistance to salinity and adaptation to acid soils make

Pennisetum clandestinum a candidate for soil utilisation and reclamation. Because it can germinate and grow in a variety of areas. [

21]. The next step in this work is the selection of accessions to make a morphological and productive characterisation of the different zones of the northern macro-region of Peru, as well as the evaluation of the level of animal consumption and milk productivity because no evidence of local studies has been found, as well as the morphological, phylogenetic and phylogenetic differentiation [

44]. Moreover, molecular or genomic [

45] in conditions of the agro-productive zone and livestock interest were exposed in the present study.

4. Conclusions

It was determined that nitrogen fertilisation at 150% (120 kg N2. ha-1) of the recommended laboratory dose influences the annual protein production at 3 454.53 Kg CP. ha-1. yr-1, being statistically similar to the application of 80 kg N2. ha-1; In the same treatments, 23.54 % and 20.11 % of CP were achieved, and the contribution of ashes ranges between 10.32 % and 12.15 %. The distance from the forage floor to the live fences influences biomass production, and 19 176.23 kg DM. ha-1. yr-1 at an interval of 8.5 to 11.5 meters distance to the base of the cypress tree (Cupressus lusitanica), and by the effect of the shade was achieved 7 424.31 kg DM. ha-1. yr-1 at a distance of 1.5 to 4.5 meters. Organic matter favours the biomass yield of Kikuyu, although there is no evidence of statistical differences in dry matter production between 30 and 60 days of cutting (p=0.1036), the annual CP production is higher at 30 days of cutting (values of 2 808.84 Kg CP. ha-1. yr-1). The highest DM production per day is obtained at 45 days, generating a higher biomass accumulation of 21 186.9 kg DM. ha-1. yr-1 with a growth rate of 58.05 kg DM ha-1. day-1. The consideration of Pennisetum clandestinum for dairy cattle is viable, taking into account that it opens the possibility of implementing a plant improvement programme in this species, aimed at increasing the composition of the diet in high-production cows due to its high yield and good chemical composition in highland conditions.

Author Contributions

A short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided for research articles with several authors. The following statements should be used "Conceptualization, AD and YB; methodology, WC, L.V-F. and WAG; software, W.A-G., L.V-F. and MC; validation, MC and WC, formal analysis, W.A-G. and L.V-F; investigation, AD, YB, Y.M-V, L.V-F. and RF; resources, AD, YB and CQ; data curation, WAG and MC; writing-original draft preparation, RF, L.V-F. and W.A-G.; writing- review and editing, L.V-F., W.A-G, and Y.M-V.; visualisation, W.A-G; supervision, L.V-F. and CQ; project administration, L.V-F. and RF; funding acquisition, L.V-F, Y.M-V and, CQ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript".

Funding

This work was financed with resources from Project CUI 2432072: 'Mejoramiento de la disponibilidad de material genético de ganado bovino con alto valor a nivel nacional. 7 departamentos' of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation - Peru

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

To the Faculty of Livestock Science Engineering of the National University of Cajamarca-Peru authorities for providing the facilities to execute the research. To Cristian Portal Mendo for the Laboratory analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- GRC, G.R. de C. Producción Lechera En Cajamarca Supera 361 000 000 Litros Anuales Available online: https://www.regioncajamarca.gob.pe/portal/noticias/det/3381.

- Villar Cabeza, M.A.; Cuellar Bautista, J.E.; Valentin Castañeda, S.L. Valoración técnica, económica y ambiental de tres sistemas de silvopasturas, en la región Cajamarca; Primera.; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria: Lima, 2014; ISBN 2014 - 11293. [Google Scholar]

- Vizconde Suárez, J.Y. La Fitorremediación de Suelos Contaminados Por Relaves Mineros a Través de Dactylis Glomerata y Pennisetum Clandestinum. Rev. Inst. Investig. Fac. Minas Metal. Cienc. Geográficas 2023, 26, e25283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Botello, M.T.; Andrade-Canto, S.B.; López-Cortez, M.D.S.; Leyva-Daniel, D.E.; Delgado-Huerta, Z.E.; Garcia-Ochoa, F. Microscopy and Spectroscopy Analyses of Methylene Blue Biosorption on Pennisetum Clandestinum Waste. Int. J. Biol. Nat. Sci. 2022, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang Kee, J.; Gonzales, M.J.; Ponce, O.; Ramírez, L.; León, V.; Torres, A.; Corpus, M.; Loayza-Muro, R. Accumulation of Heavy Metals in Native Andean Plants: Potential Tools for Soil Phytoremediation in Ancash (Peru). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 33957–33966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco Vidal, L.; Delgado, J.; Andrade, G. Vulnerability Factors to Global Climate Change in the High Andean Colombian Wetlands. Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2013, 22, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos-Cacho, R.; Vallejos-Fernández, L.A.; Alvarez-García, W.Y.; Tapia-Acosta, E.A.; Saldanha-Odriozola, S.; Quilcate-Pairazaman, C.E. Sustainability of Lolium Multiflorum L. ‘Cajamarquino Ecotype’, Associated with Trifolium Repens L., at Three Cutting Frequencies in the Northern Highlands of Peru. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.O.; Mejía, F.L.; Vasquez, H.; Bernal, W.; Álvarez, W.Y. Botanical Composition and Nutritional Evaluation of Pastures in Different Silvopastoral Systems in Molinopampa, Amazonas Region, Peru. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo-Uriarte, J.A.; Oliva-Cruz, S.M.; Maicelo-Quintana, J.L.; Meléndez-Mori, J.B.; Collazos-Silva, R. Silvopastoral Arrangements with Alnus Acuminataand Their Effect Onproductive and Nutritional Parameters of the Forage Component. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2022, 13, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Echavarria, D.M.; Granja-Salcedo, Y.T.; Noriega-Marquez, J.G.; Valderrama, L.A.G.; Vargas, J.A.C.; Berchielli, T.T. Crude Glycerol Increases Neutral Detergent Fiber Degradability and Modulates Rumen Fermentative Dynamics of Kikuyu Grass in Non-Lactating Holstein Cows Raised in Tropical Conditions. Dairy 2024, 5, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Gómez, R.; Camelo, M.; Estrada, G.A.; Bonilla, R. Evaluación de Bacterias Rizosfericas Asociadas a Pennisetum Clandestinum Como Promotoras Del Crecimiento Vegetal En Condiciones de Invernadero. 2019.

- Royani, J.I.; Utami, R.N.; Maulana, S.; Agustina, H. ; Herdis; Herry, R. ; Sarmedi; Mansyur Biodiversity of Kikuyu Grass (Pennisetum Clandestinum Hochst. Ex Chiov) in Indonesia as High Protein Forage Based on Morphology and Nutrition Compared. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 902, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmelmann, C.E.N.; Prates, Ê.R.; Gomes, I.P.D.O.; Thaler Neto, A.; Barcellos, J.O.J. Suplementação Energética Ou Energético-Protéica Para Vacas Leiteiras Em Pastagem de Quicuio (Pennisetum Clandestinum) No Planalto Sul de Santa Catarina. Acta Sci. Vet. 2018, 36, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri Zuluaga, J.; Restrepo, L.F.; Parra, J.E. Comparative evaluation of the productive and agronomic parameters of the kikuyo Pennisetum clandestinum grass under two fertilization methods. Rev. Lasallista Investig. 2010, 7, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fokom, W.D.; Tendonkeng, F.; Azangue, G.J.; Miégoué, E.; Djoumessi, F.-G.T.; Kwayep, N.C.; Mouchili, M. Effects of Different Levels of Fertilization with Hen Droppings on the Production and Chemical Composition of Pennisetum Clandestinum (Poaceae). Open J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 11, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastiwi, H.A.; Negara, W.; Martono, S.; Negoro, P.S.; Wahyuni, D.S.; Maulana, S.; Gopar, R.A.; Purba, R.D. Prediction of in Vitro True Digestibility from Fiber Fraction Content in Kikuyu Grass (Pennisetum Clandestinum)-Study Using Horse Fecal Inoculum.; Malang, Indonesia, 2024; p. 070035.

- Lowe, K.F.; Bowdler, T.M.; Holton, T.A.; Skabo, S.J. Phenotypic and Genotypic Variation within Populations of Kikuyu (Pennisetum Clandestinum) in Australia. Trop. Grassl. 2010, 44, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tieubou Tsopgni, L.; Lemoufouet, J.; Meutchieye, F.; Edie Nounamo, L.W.; Nyembo Kondo, C.; Kana, J.R.; Mouchili, M.; Feudjio, B.A. Nutritive Value of Forages Consumed by Ruminants during the Dry Season in the Western Highlands of Cameroon. Grassl. Res. 2023, 2, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Muñoz, E.; Andriamandroso, A.; Beckers, Y.; Ron, L.; Montufar, C.; Da Silva Neto, G.; Borja, J.; Lebeau, F.; Bindelle, J. Analysis of the Nutritional and Productive Behaviour of Dairy Cows under Three Rotation Bands of Pastures, Pichincha, Ecuador. 122. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Martínez, J.D.J.; Sierra Alarcón, A.M.; Mancipe Muñoz, E.A.; Avellaneda Avellaneda, Y. Kikuyu, present grass in ruminant production systems in tropic Colombian highlands. CES Med. Vet. Zootec. 2018, 13, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Panuccio, M.R.; Eshel, A. Ecophysiology of Pennisetum Clandestinum: A Valuable Salt Tolerant Grass. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Alvarez, C.N.; Lascano-Armas, P.J.; Guevara-Viera, R.V.; Guevara-Viera, G.E.; Torres-Inga, C.S.; Aguirre-de-Juana, A.J.; Garzón-Jarrin, R.A.; Molina-Molina, E.J. Milk Production of Grazing Cows in Kikuyo (Pennisetum Clandestinum, Ex Chiov) Fertilized with Poultry Manure. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafur Sanchez, B. Efecto Del Sistema Silvopastoril Con Alnus Acuminata En El Valor Agronómico y Nutricional Del Pennisetum Clandestinum. Rev. Científica UNTRM Cienc. Nat. E Ing. 2021, 3, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Balocchi, O.; Keim, J.P.; Rodríguez, C. Efecto de La Frecuencia de Defoliación En El Rendimiento y Composición Nutricional de Pennisetum Clandestinum Hochst. Ex Chiov. Agro Sur 2016, 44, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú [SENAMHI] Datos Hidrometeorológicos a Nivel Nacional Available online:. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=estaciones (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de la Calidad [INACAL] 92. Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria - INIA - Laboratorio de Suelos, Agua y Foliares (LABSAF) Available online:. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3962013/3309217-21-inia-labsaf-sede-banos-del-inca-ampliacion-exp-00315-2023-da-e-2024-05-02%282%29.pdf?v=1715295019 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- AOAC Official Method 954.01Protein (Crude) in Animal Feed and Pet Food: Kjeldahl Method. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL; Latimer, G.W., Jr., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2023; p. 0 ISBN 978-0-19-761013-8.

- AOAC Official Method 920.39Fat (Crude) or Ether Extract in Animal Feed. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL; Latimer, G.W., Jr., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2023; p. 0 ISBN 978-0-19-761013-8.

- Thiex, N.; Novotny, L.; Crawford, A. Determination of Ash in Animal Feed: AOAC Official Method 942. 05 Revisited. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C. InfoStat 2011.

- Carrasco Chilón, W. Determinación del estado actual de la composición florística del piso forrajero en la campiña de Cajamarca. Tesis de maestría, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca: Cajamarca, 2019.

- Lapierre, H.; Martineau, R.; Hanigan, M.D.; Van Lingen, H.J.; Kebreab, E.; Spek, J.W.; Ouellet, D.R. Review: Impact of Protein and Energy Supply on the Fate of Amino Acids from Absorption to Milk Protein in Dairy Cows. Animal 2020, 14, s87–s102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejos-Fernández, L.A.; Alvarez, W.Y.; Paredes-Arana, M.E.; Pinares-Patiño, C.; Bustíos-Valdivia, J.C.; Vásquez, H.; García-Ticllacuri, R. Productive Behavior and Nutritional Value of 22 Genotypes of Ryegrass (Lolium Spp. ) on Three High Andean Floors of Northern Peru. Sci. Agropecu. 2020, 11, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schat, L.; Schubert, M.; Fjellheim, S.; Humphreys, A.M. Drought Tolerance as an Evolutionary Precursor to Frost and Winter Tolerance in Grasses 2024.

- Vásquez, H.; Valqui, L.; Alegre, J.C.; Gómez, C.; Maicelo, J. Analysis of Four Silvopastoral Systems in Peru: Physical and Nutritional Characterization of Pastures, Floristic Composition, Carbon and CO2 Reserves. Sci. Agropecu. 2020, 11, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Echavarria, D.M.; Giraldo Valderrama, L.A.; Marín Gómez, A. In Vitro Fermentation of Pennisetum Clandestinum Hochst. Ex Chiov Increased Methane Production with Ruminal Fluid Adapted to Crude Glycerol. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, R. IV Censo Nacional Agropecuario y El Descubrimiento de La Agricultura. Avances En La Investigación. Otras Investig. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Cevallos, C.E.D.O.C.A.P. La Agricultura Familiar En El Perú: Brechas, Retos y Oportunidades; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura, 2023; ISBN 978-92-5-137732-1.

- López-Vigoa, O.; Sánchez-Santana, T.; Iglesias-Gómez, J.M.; Lamela-López, L.; Soca-Pérez, M.; Arece-García, J.; Milera-Rodríguez, M. de la C. Silvopastoral Systems as Alternative for Sustainable Animal Production in the Current Context of Tropical Livestock Production. Pastos Forrajes 2017, 40, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, H.; Valqui, L.; Alegre, J.C.; Gómez, C.; Maicelo, J. Analysis of Four Silvopastoral Systems in Peru: Physical and Nutritional Characterization of Pastures, Floristic Composition, Carbon and CO2 Reserves. Sci. Agropecu. 2020, 11, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Zhu-Barker, X.; Decock, C. Effects of Organic Fertilizers on the Soil Microorganisms Responsible for N2O Emissions: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Shao, L.; Qin, F.; Yang, J.; Gu, H.; Zhai, P.; Pan, X. Effects of Organic Fertilizers on Yield, Soil Physico-Chemical Property, Soil Microbial Community Diversity and Structure of Brassica Rapa Var. Chinensis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1132853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, N.; Xiu, W.; Zhao, J.; Yang, D. Effects of Organic Fertilizer Incorporation Practices on Crops Yield, Soil Quality, and Soil Fauna Feeding Activity in the Wheat-Maize Rotation System. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1058071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, M. Comparative Analysis of the Chloroplast Genome for Four Pennisetum Species: Molecular Structure and Phylogenetic Relationships. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 687844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawfetrias, W.; Royani, J.I.; Bidara, I.S.; Handayani, D.; Surahman, M. ; Herdis; Herry, R. ; Sarmedi; Mansyur Optimization of DNA Extraction and Amplification of Kikuyu (Pennisetum Clandestinum Hochst. Ex Chiov) for Molecular Identification. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 902, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).