1. Introduction

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) is among the major oil seed crop grown globally due to its short growing season (FAO, 2017). Sunflower is grown for edible oil and seeds consumed by human, domesticated animals, and birds (Konyali, 2017). Sunflower is produced in more than 27 million of hectares worldwide (Muradov et al., 2019). Tanzania is among the top ten sunflower producers in the world, producing about 2.4% of the World production and 34% of African production (Guney et al., 2017; Isinika and Jeckoniah 2021). In Tanzania, sunflower crop is grown in many areas by small-scale farmers (BOT, 2017). The central zone regions which include Singida and Dodoma are the major sunflower producers, contributing about 61% of the country total production (Tibamanya, 2021). Sunflower production improves smallholder farmers income, which in turn contributes to the country’s income generation (Sebyiga, 2020).

Despite of being among top ten sunflower major producers in the World, Tanzania can meet only about 30 to 45% of internal demand for edible oil while importing about 55 to 70% (Balchin et al.,2018). Among the factors contributing to low production of sunflower is unavailability of quality seeds to smallholder farmers.

Seed health is among important factors for successful cultivation and yield exploration of a crop (FAO, 2017). Researches show seed borne fungal infections reported to cause about 9.7% annual yield loss worldwide (Kumar, 2020). Seed borne fungal infection reduces germination, seedling vigour and cause variation in plant morphology after seed deterioration through seed abortion, shrinking, reduced size, seed rot as reported by Niaz and Dawar, (2009) and Sserumaga et al., (2015).

Furthermore, the infection rate of stored seeds depends on some environmental conditions such as high relative humidity, suitable temperature, and high level of moisture content in seed. The study of seed-borne pathogens is necessary to determine seed health and to improve germination potential of seed which finally leads to increase of the crop production (Masomeh et al., 2012). Since small holder farmers store their produced seeds for the next planting season, the seeds become contaminated by seed borne fungi including pathogenic fungi during storage which could reduce seed germination and vigour as described by Gebeyaw, (2020).

Seed health testing to detect seed-borne pathogens is an important step in the management of crop diseases. According to Abd-El-Aziz and El-Satar, (2016), ten (10) fungi were identified from four sunflower seed genotypes. These were as Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, Aspergillus spp. Cladosporium herbarum, Fusarium equiseti, Paecilomyces variotii, Penicillium spp. and Rhizopus arrihizus. However, little is known about the status of fungal pathogens in stored sunflower seeds in Tanzania. This information is necessary for local seed growers as well as smallholder farmers to understand the seed-borne fungal pathogens infecting stored sunflower seeds. The aim of this study, therefore, was to identify seed-borne mycoflora of stored sunflower seeds under ambient conditions in the country and their influence on seed viability and vigour.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Seed Material

The Quality Declared Seeds (QDS), Certified OPV, and Farmer Saved Seeds (FSS) samples of sunflower that were gathered from sunflower QDS producers, Agricultural Seed Agency (ASA), and farmers in the 2022–2023 growing season were utilized. The seeds were stored in three distinct types of packaging: sisal bags, polypropylene bags, and plastic containers. The seeds were allowed to air dry naturally until their moisture content dropped to 9%. A high temperature oven procedure was used to determine the moisture content of the seeds.

2.2. Seed Preservation

The laboratory experiment on storage was conducted at the African Seed Health Lab within the Department of Crop Science and Horticulture at Sokoine University of Agriculture. Each seed class/type weighed 1.5 kg, were packaged individually in sisal bags, polypropylene bags, and plastic containers. The plastic containers were securely closed with their plastic coverings, and the sisal and polypropylene bags were expertly sewn together using strings.

Subsequently, the seeds were placed in the laboratory for ambient preservation, each in its own packaging material for six months, from December 2022 to June 2023. Seed samples were collected every month to evaluate the seed health, seed viability and vigour of stored seeds. In accordance with ISTA, (2022) requirements, the sunflower seeds were tested for fungal infestation and infection, viability and seedling vigour prior to storage in order to determine the seeds' initial quality.

2.3. Experimental Design

The experimental design consisted of three classes of sunflower seeds (QDS, certified seeds, and FSS) as the sub-plot factor, and three types of packaging materials (plastic containers, polypropylene bags, and sisal bags) as the main factor. The storage period was the sub-sub plot factor, with six levels spanning from month-one to month-six. This trial was therefore conducted using a split-split-plot arrangement in a randomized complete block design, with three replicates.

2.4. Collected Data

2.4.1. Seed-Borne Fungal Microbes

Two hundred (200) seeds from each treatment were plated in petri-dishes on a monthly basis, with ten seeds per dish utilizing blotter papers. The blotter paper method was chosen as it had been previously reported by other researchers such as Patil et al., (2018) and Nahar et al. (2005), to be the most effective approach for detecting a variety of seed-borne mycoflora in crops, including sunflower.

Prior to plating, the sunflower seeds were submerged in a 2% NaOCl2 solution for five minutes, followed by three minutes of sterile water rinsing. The cultures were then maintained at room temperature for seven days, with light and dark cycles. On the eighth day, the seeds were examined under a stereomicroscope to monitor the growth of the fungus. A compound microscope was then used to examine the fungal conidia and conidiomata on slides, and different magnifications were employed to look at the spores and mycelia produced by each group of fungi. Fungal species were identified as per Mathur and Kongsdal (2003).

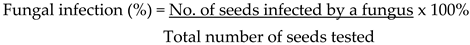

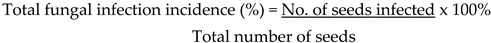

Equations (i-ii) below were used to get fungal infection incidence, Ghiasian et al., (2004):

2.4.2. Germination Test

Two hundred seeds from each respective sample were sown in four replications. The test was assessed by placing the seedlings in germination bowls filled with sterile sand soil. The soil was watered as needed to keep it at the necessary moisture content. Every day for ten days after the seeding date, germination was monitored.

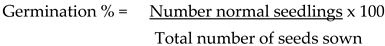

Germination percentages of the seedlings were determined as per ISTA (2022) formula:

2.4.3. Seedling Vigour Index

This was performed simultaneously with standard germination. At the final count (10 days), all seedlings, which had complete morphological parts were selected and regarded as vigorous seedlings and average seedling dry weight of 20 seedlings were determined, which were then taken for determination of seedling vigour index using the formula (iv) as suggested by Abdul-Baki and Anderson (1973).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied in analysing the collected data using ‘The 16th version of GenStat Discovery Statistical Package’. The Tukey Honest Significance Difference test (HSD) was used for means separation at a significance threshold of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Seed-Borne Fungi

3.1.1. Fungal Infection Percentage, Seed Germination Percentage and Seedling Vigour Index as Influenced by Packaging Material, Seed Class/Type and Storage Period on Stored Sunflower Seeds

The study's findings revealed that the prevalence of fungal infection on stored sunflower seeds, as influenced by packaging material, seed type, and storage duration, was found to be significantly different (P < 0.001). The data presented in Table 1 indicated that sisal bags showed the highest fungal infection rate (7.56%) followed by polypropylene bags (6.91%), while plastic containers had the lowest rate (6.63%). Moreover, the results demonstrated that the effect of seed type on fungal infection was also significantly different (P< 0.001). Farmer-saved seeds had the highest infection rate (7.70%) followed by Quality Declared Seeds (6.75%) while certified seeds had the lowest rate (6.64%), (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fungal infection percentage, seed germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by packaging material, seed class/type and storage period on stored sunflower seeds.

Table 1.

Fungal infection percentage, seed germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by packaging material, seed class/type and storage period on stored sunflower seeds.

| Treatment |

Fungal infection (%) |

Germination (%) |

Seedling vigour index |

| Packaging materials (Pm) |

|

|

| Pm1 |

6.63a |

83.97a |

119.8a |

| Pm2 |

6.91b |

81.47b |

107.6b |

| Pm3 |

7.56c |

78.58c |

100.2c |

| Mean |

7.031 |

81.34 |

109.19 |

| SE |

0.0929 |

0.128 |

0.734 |

| P-value |

<.005 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| Seed type (ST) |

|

| ST1 |

6.64a |

88.17a |

123.0a |

| ST2 |

6.75a |

87.28a |

115.8b |

| ST3 |

7.70b |

68.58b |

88.8c |

| SE |

0.085 |

0.292 |

0.699 |

| P-value |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| Mean |

7.031 |

81.34 |

109.19 |

| CV% |

2.3 |

0.3 |

1.2 |

| Storage period |

|

| M0 |

5.45a |

87.00a |

133.7a |

| M2 |

6.52b |

83.93b |

117.2b |

| M4 |

7.58c |

79.93c |

99.7c |

| M6 |

8.58d |

74.52d |

86.1d |

| Mean |

7.031 |

81.34 |

109.19 |

| SE |

0.0186 |

0.263 |

1.001 |

| CV% |

2.3 |

0.3 |

1.2 |

| P-value |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

Besides, the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) revealed that the fungal infection percentage was significantly influenced by the storage period, with a p-value of <0.001. The fungal infection rate increased significantly with the duration of storage, starting from 5.45% at the control (Month 0) to 6.52%, 7.58%, and 8.58% at Month 2, Month 4, and Month 6 of storage, respectively (Table 1).

3.1.2. Fungal Infection Percentage, seed Germination Percentage and Seedling Vigour Index as Influenced by Combination Effect of Packaging Material, Seed Class/Type on Stored Sunflower Seeds

The impact of packaging materials and seed class on fungal seed-borne infection of stored sunflower was not found to be statistically significant different (P=0.386), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fungal infection percentage, seed germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by combination effect of packaging material, seed class/type on stored sunflower seeds.

Table 2.

Fungal infection percentage, seed germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by combination effect of packaging material, seed class/type on stored sunflower seeds.

| Packaging material (Pm) x seed type (ST) |

Fungal infection (%) |

Germination (%) |

Seedling vigour index |

| Pm1 ST2 |

6.20a |

90ab |

123.9b |

| Pm1 ST1 |

6.30a |

90.5a |

138.1a |

| Pm2 ST1 |

6.35a |

88.5bc |

121.5b |

| Pm2 ST2 |

6.79b |

87.5c |

113.5c |

| Pm3 ST2 |

7.25c |

84.33d |

110c |

| Pm3 ST1 |

7.27c |

85.5d |

109.3c |

| Pm1 ST3 |

7.37c |

71.42e |

97.4d |

| Pm2 ST3 |

7.57c |

68.42f |

87.7e |

| Pm3 ST3 |

8.17d |

65.92g |

81.3e |

| Mean |

7.031 |

81.34 |

109.19 |

| SE |

0.1519 |

0.433 |

1.231 |

| CV% |

3.6 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

| P-value |

0.386 |

0.86 |

<.001 |

However, a difference in numerical values was observed among the treatments, where farmer-saved seeds packed in sisal bags had the highest fungal infection percentage (8.17) followed by those packed in polypropylene bags (7.57). In contrast, quality declared seeds and certified seeds recorded the lowest fungal infection percentages with values of 6.20% and 6.30%, respectively.

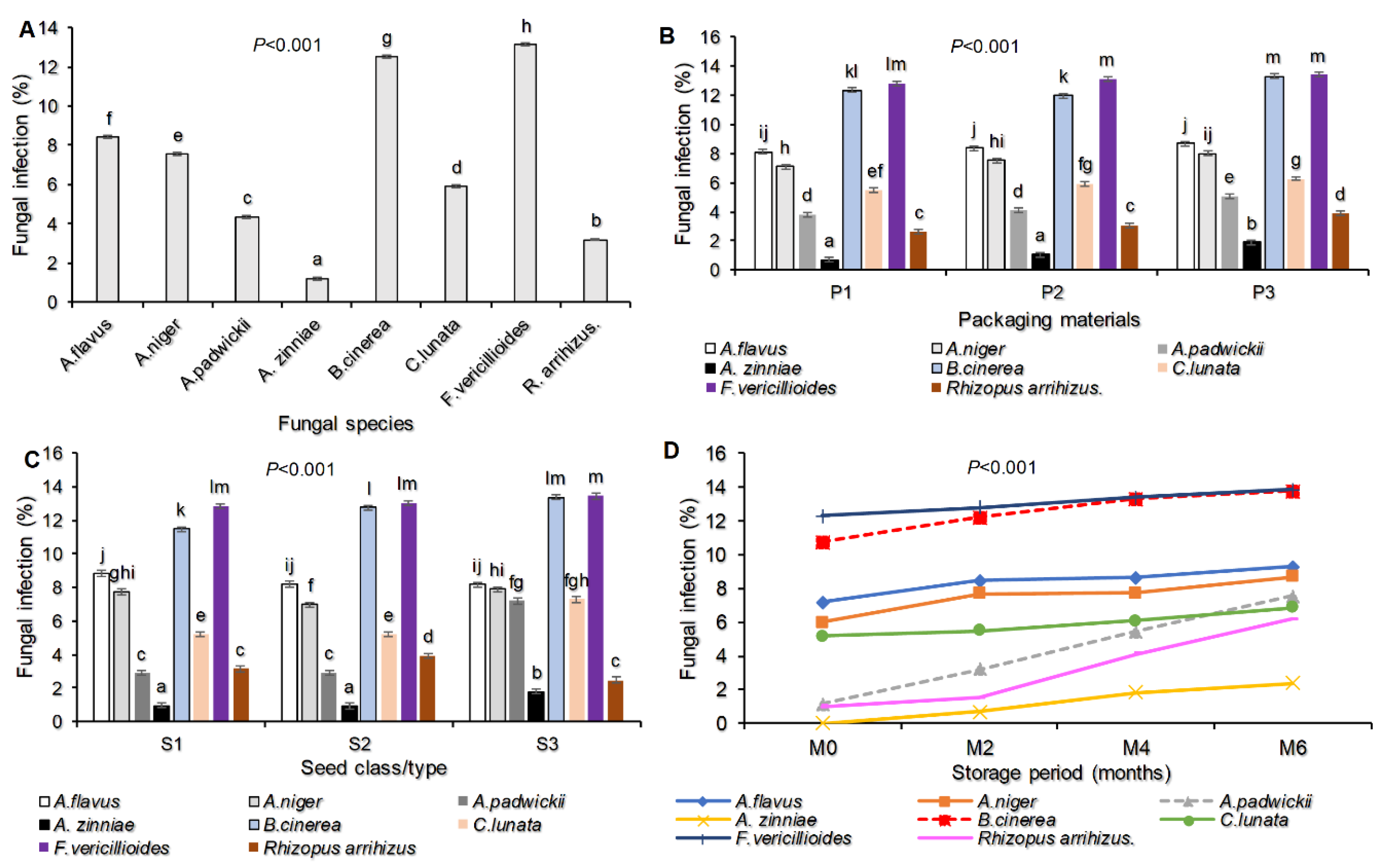

The study findings identified eight fungal species from the three seed classes/types of sunflower seed that were tested. These species were Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Alternaria padwickii, Alternaria zinniae, Botrytis cinerea, Curvularia lunata, Fusarium vericillioides, and Rhizopus arrihizus. Among these fungi, Fusarium vericillioides had the highest percentage of infection at 13.1%, followed by Botrytis cinerea at 12.5%, and the lowest incidence was observed with Alternaria zinniae at 1.2%. This information is presented in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Fungal infection percentage as: identified in stored seeds and their species (A), influenced by interaction of fungal species and packaging material (B); influenced fungal species and seed class/type (C); influenced by fungal species and storage period (D) on stored sunflower seeds. Where P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

Figure 1.

Fungal infection percentage as: identified in stored seeds and their species (A), influenced by interaction of fungal species and packaging material (B); influenced fungal species and seed class/type (C); influenced by fungal species and storage period (D) on stored sunflower seeds. Where P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

Regarding the packaging material and seed class, the fungal infection percentage was highly significantly different (P<0.001) Figure (1B-C). The Fusarium vericillioides was recorded with the greatest fungal infection percentage (13.38) in sisal bags followed by Botrytis cinerea (13.29) recorded in the same packaging materials. The smallest fungal infection percentage was recorded with the Alternaria zinnae (0.71) followed by Rhizopus arrihizus (2.63) in seeds packed in plastic container (Figure 1B). In the seed class, the Fusarium vericillioides was also recorded with the highest infection percentage (13.44) in Farmer saved seeds followed by Botrytis cinerea (13.36) in the same seed type. The smallest fungal infection percentage was recorded with the Alternaria zinnae (0.93) in Quality Declared Seeds (Figure 1C). Still, the fungal infection percentage for seed borne fungal pathogens and saprophytes varied due to storage period, from Figure 1D it shows that at the end of month six Fusarium vericillioides recorded the highest infection percentage of 13.85 followed by Botrytis cinerea (13.78) while Alternaria zinniae (2.41) recorded the smallest infection percentage.

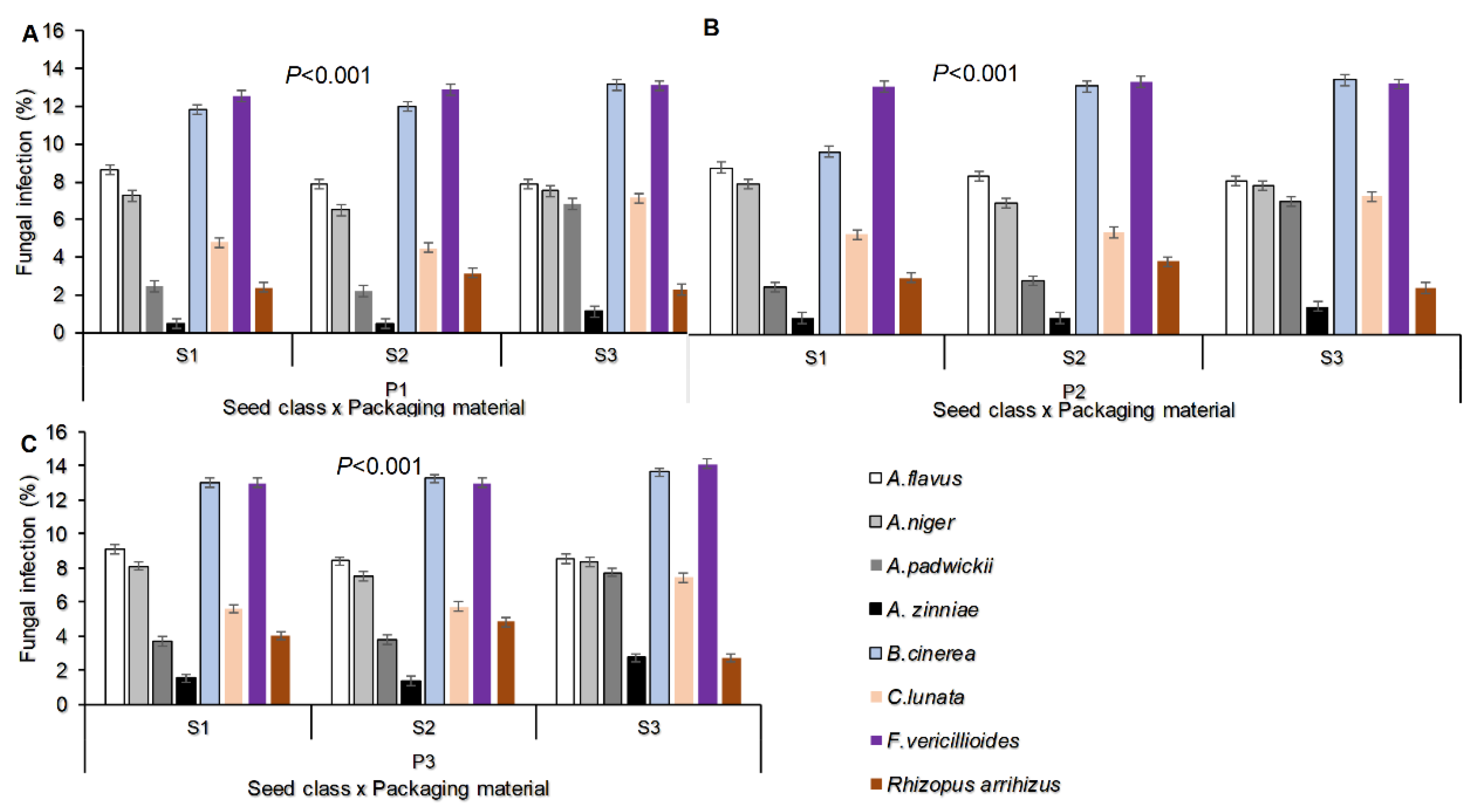

3.1.3. Fungal Infection Percentage as Influenced by Seed Class/Type and Packaging Materials

The infection percentage was also highly significantly affected by interaction of seed class/type and packaging materials and fungal species (P<0.001), (Figure 2A-C). Fusarium vericillioides recorded the highest infection percentage (14.13) in the Farmer saved seeds packed in sisal bags followed by Botrytis cinerea (13.63) observed in the same seed type and packaging materials. The smallest fungal infection percentage was recorded by Alternaria zinniae (0.5) with certified and Quality declared seeds packed in plastic containers (Figure 2A-C).

Figure 2.

Fungal infection percentage as influenced by seed class/type and packaging materials (A-C) Where S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags.

Figure 2.

Fungal infection percentage as influenced by seed class/type and packaging materials (A-C) Where S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags.

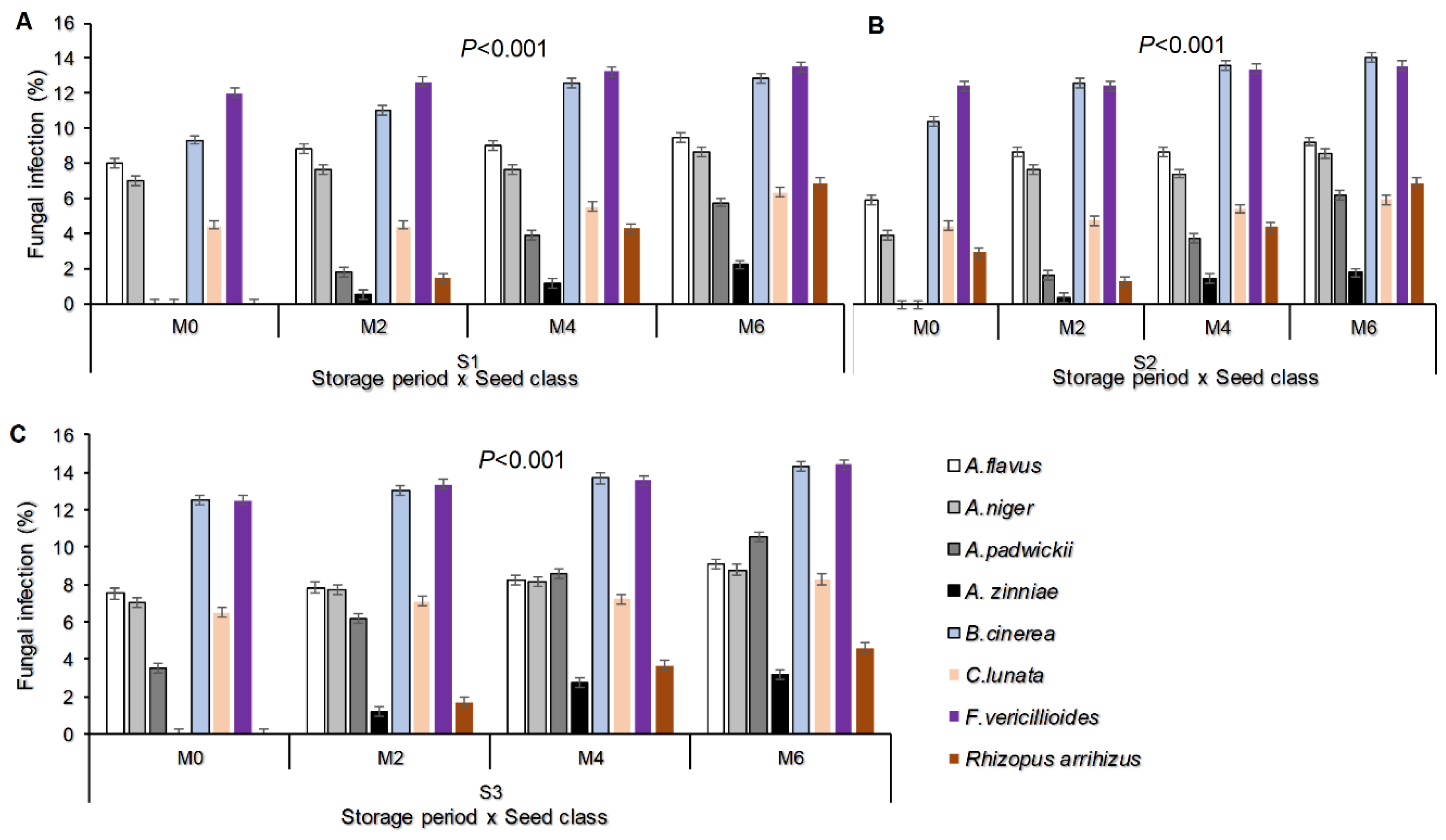

3.1.4. Fungal Infection Percentage as Influenced by Storage Period and Seed Class/Type

The seed borne fungal pathogens incidence was affected by the storage periods whereby significant different was observed among seed classes/types (P<0.001), (Figure 3). Until the end of the storage period of month six, Fusarium vericillioides recorded the maximum infection percentage with Farmer saved seeds (14.39) followed by Botrytis cinerea (14.28) recorded in the same seeds. On the other hand, at the end of month six, the minimum fungal pathogen infection was recorded by Alternaria zinniae (1.83) with Quality Declared Seeds, (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Fungal infection percentage as influenced by storage period and seed class/type (A-C) Where M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farmer saved seeds.

Figure 3.

Fungal infection percentage as influenced by storage period and seed class/type (A-C) Where M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farmer saved seeds.

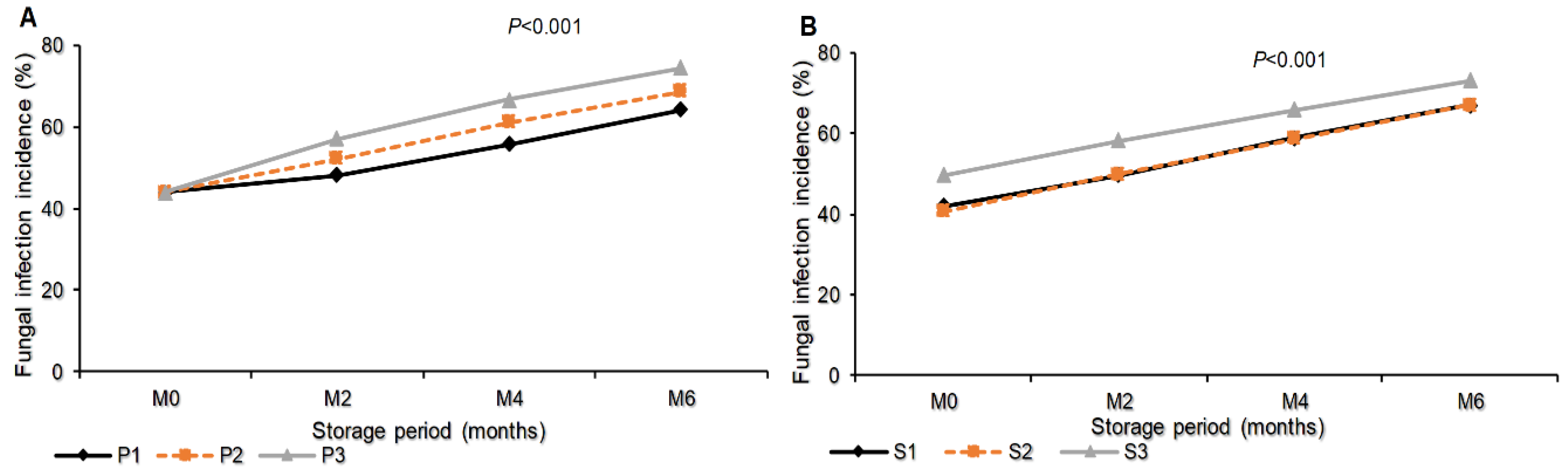

3.1.5. Total Fungal Infection Incidence as Influenced by Interaction of Storage Period and Packaging Materials, Storage Period and Seed Class/Type on Stored Sunflower Seeds

The Figure 4 indicates that, the total fungal pathogens infection incidence was significantly different (P<0.001) due to packaging materials as well as seed class. At the end of storage period, month six, the seed packed in sisal bags recorded the maximum infection incidence (74.33%) followed by seeds packed in polypropylene materials (68.61%). Seeds packed in plastic container recorded the minimum infection incidence (64.17%). Regarding the seed class/type, maximum fungal infection incidence was recorded with Farmer saved seeds (73.11%) and minimum infection incidence was recorded with certified seeds (67.06%) which was not significantly different from the infection incidence recorded with the Quality declared seeds (66.94%), Figure (4A-B).

Figure 4.

Total Fungal infection incidence as influenced by interaction of: Storage period and packaging materials (A) Storage period and seed class/type (B) on stored sunflower seeds. M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

Figure 4.

Total Fungal infection incidence as influenced by interaction of: Storage period and packaging materials (A) Storage period and seed class/type (B) on stored sunflower seeds. M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

3.2. Influence on Germination Percentage (%) and Seedling Vigour Index

From Table 1, the findings show that seed germination percentage and seedling vigour index were influenced by seed borne fungi, packaging material, seed class/type and storage period on stored sunflower seeds, highly significant different (P<0.001). The seeds stored in sisal bags recorded the smallest germination percentage and seedling vigour index, 78.58% and 100.2 respectively. Followed by the seeds stored in polypropylene bags while the plastic container recorded the highest germination percentage and seedling vigour index (83.97% and 119.8 respectively), Table 1.

Additionally, the influence of seed class/types on germination percentage and seedling vigour index of stored sunflower seeds was highly significantly different (P<0.001) (Table 1). Regarding seed class/types of germination percentage and seedling vigour index was recorded smallest in the Farmer saved seeds (68.58% and 88.8 respectively) in seed class with highest fungal infection percentage followed by Quality declared seeds while the maximum germination percentage and seedling vigour index was recorded in certified seeds (88.17% and 123 respectively). In addition, the results show that germination percentage and seedling vigour index was significantly different (P<0.001) due to storage period. As the storage period increased, both germination percentage (%) and seedling vigour index decreased significantly from 87,83.93,79.93 and 74.52 for germination percentage and 133.7,117.2,99.7 and 86.1 for the seedling vigour index (Table 1).

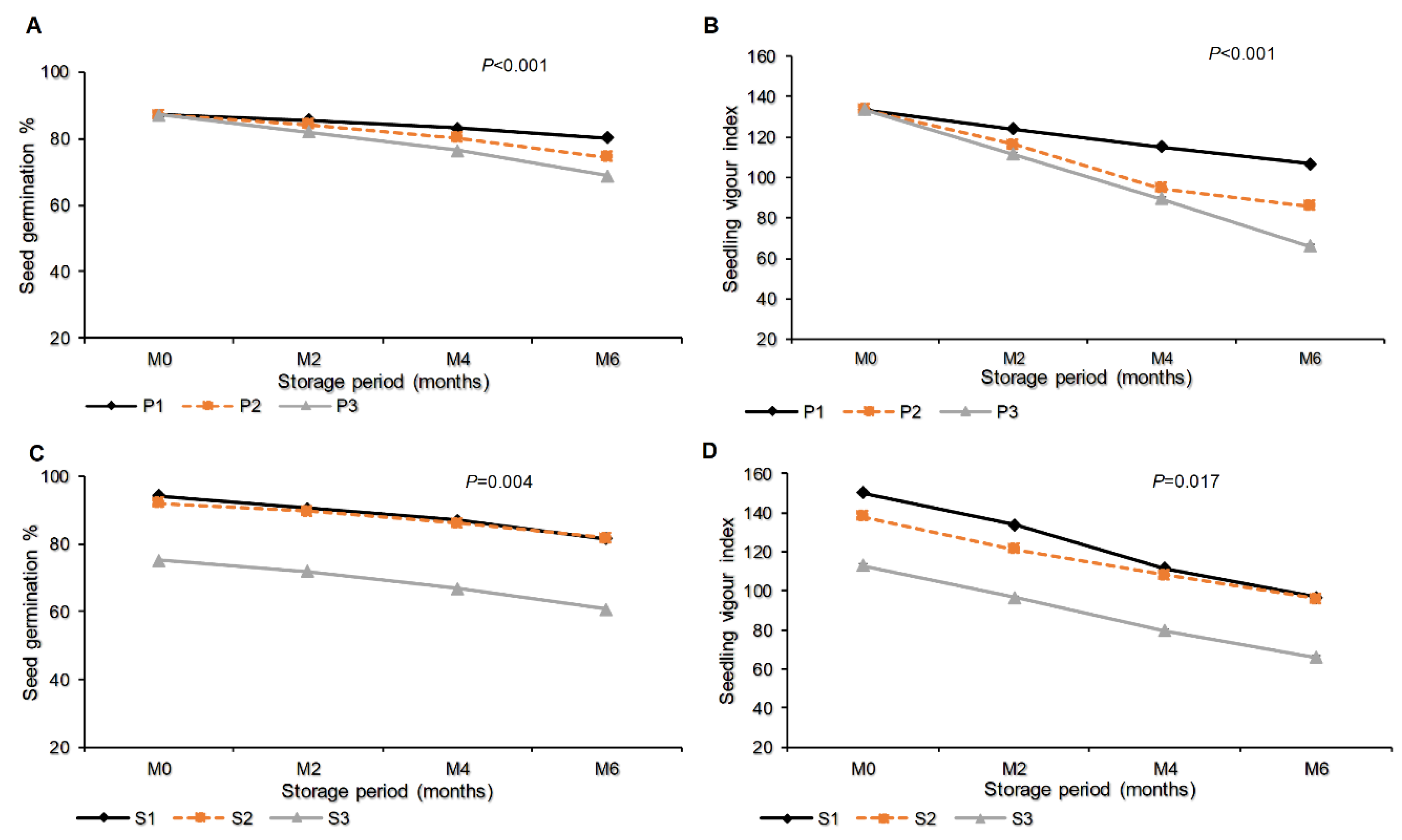

The Table 2 shows that the germination percentage was not significantly differentially influenced by the combination of packaging materials and seed class (P=0.86). However, seedling vigour index was significantly and highly affected by the combination of packaging materials and seed class (P<0.001). The highest seedling vigour index (138.1) was recorded with certified seeds packaged in plastic materials, while the smallest value (81.3) was noted in farmer-saved seeds packed in sisal bags (Table 2). The interaction effect between packaging materials and storage period expressed high significance with a P-value of <0.001 on seed germination percentage (Figure 5A) and seedling vigour index (Figure 5B). Until the end of the storage period (month six), the highest germination percentage (80.22%) and highest seedling vigour index (106.67) were recorded in seeds packed in a plastic container. This was followed by seeds packed in polypropylene bags with a seed germination percentage of 74.44% and a seedling vigour index of 85.76. The least germination percentage (68.89%) and seedling vigour index (66.0) were noted in seeds packed in sisal bags (Figure 5A-B).

Figure 5.

Germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by interaction effect of packaging materials and storage period (A-B), interaction effect of storage period and seed class/type (C-D). Where M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

Figure 5.

Germination percentage and seedling vigour index as influenced by interaction effect of packaging materials and storage period (A-B), interaction effect of storage period and seed class/type (C-D). Where M0, M2, M4 and M6 are Month 0 (Before storage), month 2, month 4 and month 6 respectively; P1=Plastic container, P2=Polypropylene bags and P3=sisal bags, S1=certified seed, S2=QDS and S3=Farm saved seeds.

Moreover, the interaction effect of seed class or seed type and storage period showed that the germination percentage and seedling vigour index were influenced significantly by P=0.004 and P=0.017 respectively. This shows that, the Quality declared seeds were observed to record the highest germination percentage (81.56%) which was not significantly different with 81.33% that recorded in certified seeds, the maximum seedling vigour index (96.76) was observed in certified seeds which did not differ significantly with 95.69 that recorded in Quality declared seeds. The minimum germination percentage (60.67%) and seedling vigour index (65.98) were recorded in Farmer saved seeds (Figure 5C-D).

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed-Borne Fungi

Differences in the incidence of seed-borne fungi infection among treatments in sunflower seeds were clearly observed during storage. Sisal bags, as packaging materials, exhibited the highest infection percentage. This could be attributed by their high permeability to moisture in the storage room, resulting in elevated seed moisture content. Consequently, the rapid multiplication of fungi occurred compared to less permeable packaging materials like plastic containers. The findings align with previous studies conducted by Shabana et al. (2015), Asha (2012), and Martín et al. (2022), who reported that highly permeable materials contribute to increased seed moisture content and thereby enhance the likelihood of fungal growth. Hasan et al. (2017) also found that seed moisture content significantly influences seed viability and contamination by storage fungi.

Variations in infection rates among seed classes/types may be attributed to disparities in initial seed quality among the seed classes/types used in the study. This conclusion aligns with the reports by FAO (2018) and Patharkar et al. (2013), which highlight that seed quality during storage depends on factors such as seed type, initial seed quality, seed moisture content, temperature, and relative humidity. Additionally, other researchers have noted varying percentages of fungal infection in stored seeds as the duration of storage increases, as observed by Wiewióra (2009) in spring barley, Kandhare (2018) in green-gram, Shabana et al. (2015) in maize, and Saeed et al. (2020) in cotton and wheat seeds.

The important fungal species recorded from stored seeds were Fusarium vericillioides, Botrytis cinerea, Aspergillus species, Alternaria spp., Curvularia lunata and Rhizopus species. Among these, the dominant seed-borne pathogenic fungi found were Alternaria padwickii, Alternaria zinniae, Botrytis cinerea, Curvularia lunata and Fusarium vericillioides. Also, three major saprophytic sunflower seed-borne fungi observed were Aspergillus flavus, A. niger and Rhizopus arrihizus. All of these pathogenic as well as saprophytic seed borne fungi were found to affect the seed viability and seedling vigour. These findings were somewhat in harmony with that found by Khalil et al., (2014) and El-Wakil (2014) reported the association of large number of fungi with sunflower seeds and their list including; Alternaria species, Fusarium species, Rhizoctonia species etc. and that these seed mycoflora are of a great importance for seed deterioration and consequently lead to seed losses and this may be as a result of the secretion of mycotoxin and fungal secondary metabolites which reduce seed quality and quantity.

The findings also are somewhat similar with the study conducted by Patil et al. (2018), which identified Alternaria alternata, Fusarium oxysporum, as well as three saprophytic fungi (Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, and Rhizopus stolonifer) as the major phytopathogenic fungi present in the sunflower varieties examined. These seed-borne fungi are known to adversely affect seed health and vigour. Previous studies by Ghoneem et al. (2014), Kandhare (2018), and Chandel and Kumar (2017) have documented that, infected seeds serve as a means of disseminating various crop diseases to different regions. Factors such as high relative humidity, suitable temperature, and increased moisture content contribute to the establishment of pests and diseases within seeds. Infestation by these fungi has been observed in all parts of the seeds, leading to external or internal damage, including seed rot, necrosis, and seedling diseases (Deshmukh and Kare, 2010). Numerous researchers have previously reported that these fungi species cause deterioration of seeds, consequently reducing the viability and vigour of stored seeds.

4.2. Influence on Germination and Seedling Vigour Index

The detected seed borne fungi were found to influence the seed germination and seedling vigour index. Concerning seed class/types of germination percentage and seedling vigour index was recorded the smallest in the FSS (68.58% and 88.8 respectively) in seed class with the highest fungal infection percentage followed by QDS while the maximum was recorded in certified seeds (88.17% and 123 respectively), the seed class/type with less fungal infection. Aspergillus species (15.94), Fusarium species (13.11) and Botrytis species (12.53) were found to be higher followed by Curvularia lunata (5.90), Alternaria species (5.57) and least in Rhizopus arrihizus (3.2)

Fusarium species including F. vericillioides were reported to cause wilting and seedling rot as most protuberant symptoms exhibited in sunflower and other crops (Nagaraja & Krishnappa 2009 and Afzal et al., 2010) reported in numerous crops, number of pathogenic and saprophytic seed borne fungi which affected harmfully the seed germination and seedling vigour index. In this situation, the findings of the current research become in harmoniousness with earlier conclusions of other researchers including Afzal et al., 2010 in sunflower and those in other seed crops like Singh et al., 2003 in pearl millet; Ahammed et al., 2006 in soybean; Nagaraja and Krishnappa 2009 in niger crop. It has long been noted that seed-borne fungal pathogens arising from seed storage like Aspergillus species and Alternaria species are responsible for reducing seed quality, protein and carbohydrate contents, reduction of germination capacity and seedling vigour by damaging seedlings causing root collar, seed rot and damping off seedlings, which all together result in the reduction of crop yield qualitatively and quantitatively. This was further reported by Anjorin & Mohammed, (2014); Masomeh et al., (2012) and Lambat et al., (2014)

Field fungi may cause weakening or death of embryos while storage fungi slowly kill the embryos of the seeds they invade. Furthermore, Botrytis cinerea causes grey-mould diseases in sunflower crop as found by Williamson et al., (2007). Seedlings raised from such seeds lack the normal vigour (Gebeyaw, 2020). Seedborne pathogenic fungi can prevent germination, kill seedlings, or reduce plant growth by damaging the roots and vascular system, which prevents the transport of water and nutrients as also reported by Hatim et al., (2022); Marcenaro & Valkonen, (2016) and Aslam et al., (2015) in sunflower, common bean, and peanuts respectively.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

Based on the current research, it can be deduced that, the fungi transmitted through the seeds were discovered to have a detrimental impact on both the viability of the seeds in terms of germination and the vigour index of the resulting seedlings in sunflower crops. As the duration of storage increased, a decrease in the percentage of seed germination and the seedling vigour index was observed. Consequently, it is strongly advised to utilize high-quality seeds including Certified and Quality declared seeds and employ appropriate storage materials in order to effectively preserve seeds for future sowing seasons. Such measures will help ensure optimal crop productivity and success.

Conflict of interests

No any of the authors of this work have conflicting interest.

Contributions by the authors

The experiment was carried out by Siwajali Selemani, who also gathered, processed, and analysed the experimental data as well as wrote the Manuscript. The entire research study implementation process was under the supervision of Richard R. Madege and Yasinta B. Nzogela

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Abd-El-Aziz, S. A., and El-Satar, A. 2016. Effect of Storage Durations on Fungal Infection, Aflatoxin Contamination, Quality and Yield of Sunflower Seeds. Zagazig Journal of Agricultural Research, 43(6), 1965-1975.

- Abdul-Baki, A.A. and Anderson, J.D., 1973 Vigour determination in soybean by multiple criteria. Crop Science, 13: 630-633 (1973).

- Afzal, R., Mughal, S. M., Munir, M., Sultana, K., Qureshi, R., Arshad, M. and Laghari, M. K. 2010. Mycoflora associated with seeds of different sunflower cultivars and its management. Pakistan Journal of Botany 42(1): 435- 445.

- Ahammed, S. K., Anandam, R. J., Prasad Babu, G., Munikrishnaiah, M. and Gopal, K. 2006. Studies on seed mycoflora of soybean and its effect on seed and seedling quality characters. Legume Researches, 29(3): 186-190.

- Anjorin, S. T., & Mohammed, M. 2014. Effect of seed-borne fungi on germination and seedling vigour of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus thumb). African Journal of Plant Science, 8(5), 232-236.

- Asha, A. M. 2012. Effect of plant products and containers on storage potential of maize hybrid. M. Sc. (Agri.) Thesis. University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad. Karnataka, India.

- Aslam MF, Irshad G, Naz F, Aslam MN, Ahmed R. 2015 Effect of seed-borne mycoflora on germination and fatty acid profile of peanuts. Pakistan Journal of Phytopathology, 27(2):131-138.

- Balchin Neil, Josaphat Kweka and Maximiliano Mendez-Parra Honest Mseri, 2018 ANSAF Tarif setting for the development of the edible oil sector in Tanzania 4th Annual Agricultural Policy Conference (AAPC) 14Th -16th, February 2018.Pp 1-12.

- BOT , 2017, “Potentiality of Sunflower Sub-sector in Tanzania”, Working Paper 10, Bank of Tanzania, Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania.

- Chandel, S., & Kumar, V. 2017 Effect of plant extracts as pre-storage seed treatment on storage fungi, germination percentage and seedling vigour of pea (Pisum sativum). Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 87(11), 1476-1481.

- Deshmukh, A. M. and Kare, M. A. 2010. Study of seed mycoflora of some oilseed crops. Bioinfolet, 7(4): 295-297.

- El-Wakil, D.A., 2014. Seed-bome fungi of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and their impact on oil quality. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science. 6(6):38-44.

- FAO, (2017). FAOSTAT Data Production, Trade, Food Balance, Food Security.

- FAO. 2018. Seeds toolkit-Module 6: Seed storage.

- Gebeyaw, M. 2020. Review on: Impact of seed-borne pathogens on seed quality. American Journal of Plant Biology, 5, 77-81. [CrossRef]

- Ghiasian, S. A.; Kord-Bacheh, P.; Rezayat, S. M.; Maghsood, A. H. and Taherkhani, H. 2004. Mycoflora of Iranian maize harvested in the main production areas. Mycopathology. 158 (1):113-121. [CrossRef]

- Ghoneem KM, Ezzat SM, El-Dadamony NM. 2014. Seedborne fungi of sunflower in Egypt with reference to pathogenic effects and their transmission. Plant Pathology Journal.; 13(4):278-284. [CrossRef]

- Guney, Y., Kallinterakis, V., & Komba, G. 2017. Herding in frontier markets: Evidence from African stock exchanges. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 47, 152-175. [CrossRef]

- Hasan K., EL Sabagh, A., Celaleddin B., Islam, M.S., 2017 Seed Quality of Lentil (Lens culinaris L.) as Affected by 45 Different Containers and Storage Periods. Scientific Journal of Crop Science 6(1) 146-152.

- Hatim, S. H., Al-Salami, I., and Jabbar, M. K., 2022. Detection of Seed-Borne Fungi Associated with Three Sunflower Cultivars and Their Effect on Seed Germination. International Journal of Agriculture and Statistical Science 18(1), 2041-2045.

- International Seed Testing Association (ISTA), 2022. International Rules for Seed Testing.

- Isinika Aida C. and Jeckoniah John, 2021 The Political Economy of Sunflower in Tanzania: A Case of Singida Region. Pp 1-32.

- Kandhare, A. S. 2018. Effect of Storage Containers on Seed Mycoflora and Seed Health of Green Gram (Vigna radiate L.) and its Cure with Botanicals. Journal of Agricultural Research & Technology:14(2), 555912.

- Khalil, A.A., D.A. Elwak-il and M.I. Ghonim, 2014. Mycoflora association and contamination with aflatoxins in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) seeds. International Journal of Plant Soil science, 3: 685-694. [CrossRef]

- Konyali, S. 2017. Sunflower production and agricultural policies in Turkey. Sosyal Bilimler Araştırma Dergisi, 6(4), 11-19.

- Lambat, A., Patil, S., Charjan, S., Gadewar, R., Babhulkar, V., & Lambat, P. 2014. Effect of Storage on Seed Germination, Seedling Vigour and Mycoflora on Cowpea. International Journal of Research in Bioscience, Agriculture and Technology.

- Marcenaro D, Valkonen JPT, 2016 Seedborne Pathogenic Fungi in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris cv. INTA Rojo) in Nicaragua. PLoS ONE 11(12): e0168662. [CrossRef]

- Martín, I.; Gálvez, L.; Guasch, L.; Palmero, D. 2022 Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State. Plants 2022, 11, 3167. [CrossRef]

- Masomeh Hajihasani, Abolfazl Hajihassani and Shahab Khaghani, 2012 Incidence and distribution of seed-borne fungi associated with wheat in Markazi Province, African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 11(23), 6290-6295.

- Mathur, S. B., and Kongsdal, O. 2003. Common laboratory seed health testing methods for detecting fungi. International Seed Testing Association. Pp.1-425.

- Muradov, A., Hasanli, Y., & Hajiyev, N. 2019. World Market Price of Oil: Impacting Factors and Forecasting (p. 184).

- Nagaraja, O. and Krishnappa, M. 2009. Seedborne mycoflora of niger (Guizotia abyssinica cass.) and its effect on germination. Indian phytopathology. 62(4): 513-517.

- Nahar, S., Mushtaq, M. and Hashmi, M. H. 2005. Seedborne mycoflora of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Pakistan Journal of Botany 37(2): 451-457.

- Niaz I, Dawar S., 2009. Detection of seed borne mycoflora in maize (Zea mays L.). Pakistan Journal of Botany 41(1): 443-451.

- Patharkar, S.P., N.R. Sontakke and G.B. Hedawoo, 2013. Evaluation of seed mycoflora and germination percentage in Helianthus annuus L. International Journal of Innovations in BioScience, 3: 1 – 5.

- Patil, A. C., Surpawanshi, A. P., Anbhule, K. A., Raner, R. B., & Hurule, S. S. 2018. Detection of sunflower seedborne mycoflora and their effect on seed and seedling parameters. International Journal of Current Microbiology & Applied Science, 6, 2509-2514.

- Ramesh, C.H. and K.M. Avitha, 2005. Presence of external and internal seed-mycoflora on sunflower seeds. Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology, 35 (2): 362-364.

- Saeed, M. F., Jamal, A., Ahmad, I., Ali, S., Shah, G. M., Husnain, S. K., ... & Wang, J. 2020 Storage conditions deteriorate cotton and wheat seeds quality: an assessment of farmers’ awareness in Pakistan. Agronomy, 10(9), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Sebyiga, B. 2020. Sunflower Production and its Potential for Improving Income of Smallholder Producers in the Central Agricultural Zone of Tanzania: A Case of Villages in Kongwa and Singida Rural Districts. Local Administration Journal, 13(3), 223-234.

- Shabana, Y. M., Ghazy, N. A., Tolba, S. A., & Fayzalla, E. A. 2015. Effect of Storage Condition and Packaging Material on Incidence of Storage Fungi and Seed Quality of Maize Grains. Journal of Plant Protection and Pathology, 6(7), 987-996. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. D., Swami, S. D. and Rawal, P. 2003. Seed mycoflora of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and its control. Plant Diseases Research 18(2): 115-118.

- Sserumaga, J. P., Makumbi, D., Simyung, L., Njoroge, K., Muthomi, J. W., Chemining’wa, G. N., ... & Bomet, D. K. 2015. Incidence and severity of potentially toxigenic Aspergillus flavus in maize (Zea mays L.) from different major maize growing regions of Uganda.

- Tibamanya, Felister Y.; Milanzi, Mursali A.; Henningsen, Arne, 2021: Drivers of and Barriers to Adoption of Improved Sunflower Varieties Amongst Smallholder Farmers in Singida, Tanzania: The double-hurdle approach, IFRO Working Paper, No. 2021/03.

- Wiewióra, B. 2009 Long-time storage effect on the seed heath of spring barley grain. Plant Breeding Seed Science, 59, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B., Tudzynski, B., Tudzynski, P., & Van Kan, J. A. 2007. Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Molecular plant pathology, 8(5), 561-580. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).