1. Introduction

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC) increase susceptibility to multiple malignancies in both women and men primarily involving breast and ovarian cancers but also prostate and pancreatic cancers [

1,

2]. Key features of HBOC syndrome are early disease onset (often before age 36), bilateral presentations, and a familial pattern with multiple affected individuals [

3]. HBOC is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and is frequently linked to pathogenic variants (PVs) in the

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 genes, essential for repairing double-stranded DNA breaks via homologous recombination (HR)[

4,

5,

6,

7].

Recently,

PALB2 has been recognized as a third highly penetrant gene [

8].

PALB2 plays a critical role in HR pathway by serving as a scaffold within a large molecular complex that includes both

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 [

9,

10]. It also facilitates the transport of

RAD51 to chromosomal lesions to initiate repair and to form the D-loop (displacement loop), which is essential for meiotic recombination repair [

11,

12]. The

BRCA2-

PALB2 dimer is essential for repair processes, including HR, DNA double-strand break repair, and the regulation of the S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. In addition to its interaction with

BRCA2 through the WD40 domain at the C-terminus,

PALB2 also binds to

BRCA1 via a coiled-coil motif at the N-terminus. Disruption of this complex can significantly reduce the efficiency of the HR repair system [

8,

12,

13,

14].

Germline biallelic PVs in

PALB2 lead to the rare autosomal recessive form of Fanconi Anemia, which is characterized by genomic instability, early bone marrow failure, growth issues, and an increased risk of cancer [

15,

16,

17]. Instead, monoallelic

PALB2 PVs can be found in 0.4% to 3.9% of breast cancer patients and have been linked to a 41–60% risk of breast cancer, a 3–5% risk of ovarian cancer and 2-5% risk of pancreatic cancer [

1,

3,

7,

18]. Carriers of germline PVs in

PALB2 often exhibit aggressive clinical and pathological features, including a triple-negative breast cancer phenotype and an earlier age of diagnosis [

9,

19].

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that women with

PALB2 PVs begin annual mammography and MRI with contrast starting at age 30. Risk-reducing mastectomy may be discussed with the patient, and, although data on risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy are limited, it may be considered starting at 45 to 50 years of age [

1].

In

PALB2 mutational screening, the molecular characterization of PVs has mainly focused on single nucleotide substitutions and small insertions and deletions. However, a smaller proportion of large genomic rearrangements (LGRs), i.e. deletions and duplications, can also significantly influence the mutational landscape [

20,

21,

22]. A few studies reported

PALB2 germline LGRs in patients with breast, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers [

10,

21,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Yang et al. [

32] identified 23 germline

PALB2 LGRs in an international study of 524 families with pathogenic

PALB2 variants: all of them were clustered in the WD40 domain and five of them involved only exon 11 (specifically, four deletions and one duplication). Several other studies confirmed that

PALB2 rearrangements occur mainly in the sequences between exon 7 and exon 13 which encode the WD40 domain, and rearrangements selectively involving exon 11 were reported in additional five cases, four duplications and one deletion [

10,

21,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

We routinely perform genetic screening of PALB2 in patients tested negative for PVs in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Our analysis identified three women carrying a deletion involving exclusively PALB2 exon 11, and one with a duplication of the same exon.

Given the frequent identification of exon 11 rearrangements in PALB2 we aimed to precisely characterize the intronic breakpoints of the rearrangements to elucidate the molecular mechanisms driving these genomic alterations. Additionally, we conducted transcript-level assessments through RNA analysis, providing valuable insights into potential splicing variations and allelic expression patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

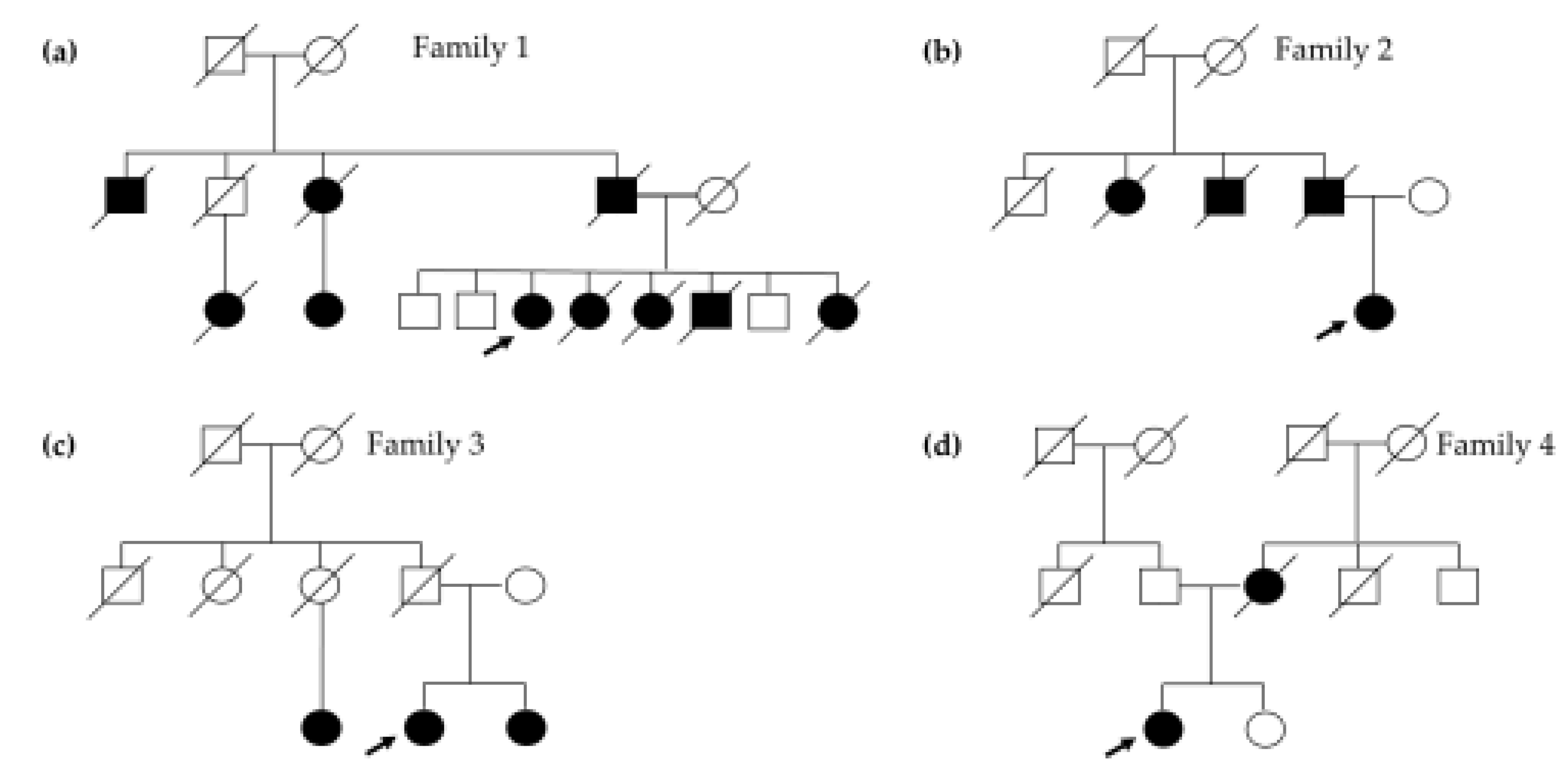

Four women, evaluated due to their medical history of cancer(s), were involved in the study. Since they tested negative for PVs in

BRCA1 and

BRCA2, we investigated a panel of 12 additional genes known to give high to moderate risk for HBOC. Pedigree of the probands is given in

Figure 1.

Patient 1 was diagnosed with breast cancer at 36 years old, with a contralateral involvement at 41. At 38 years old, she developed thyroid cancer and ten years later she manifested colorectal cancer. She had gastric cancer at 59 years of age and a third breast cancer at 62. Moreover, she was diagnosed at 62 and 63 with two primary lung cancers and is currently undergoing treatment. Three of her sisters died from various HBOC- and colon-related malignancies between the ages of 54 and 61. Her father, paternal uncles, and cousins also had a history of breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers (

Figure 1a). The patient tested negative for PVs in genes related to Lynch Syndrome and

MUTYH-associated polyposis.

Patient 2 presented with a history of breast cancer at 41 years old, with a relapse at 48 years old. At 56 years old, she was diagnosed with pancreatic neoplasia. Her father passed away at 77 years old due to pancreatic cancer diagnosed 3 years earlier, and her father’s aunt developed breast cancer at the age of 87 and died two years later (

Figure 1b).

Patient 3 was diagnosed with breast cancer and pancreatic cancer at 51 and 60 years old, respectively. In her family, her sister had breast cancer at 50 years old and one paternal cousin developed breast cancer at the age of 70 (

Figure 1c).

Patient 4 had their first breast cancer diagnosis at the age of 38 and contralateral breast cancer at 43 years old. Her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer at 38 years old and she passed away four years later (

Figure 1d).

2.2. DNA Extraction and NGS Analysis

Patient’s samples were collected in tubes containing EDTA. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from peripheral blood samples using the QIAsymphony SP/AS nucleic acid extraction tool (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Next Generation Sequencing was performed using the Devyser BRCA and HBOC kits (Devyser AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with target enrichment probes for BRCA1/BRCA2 and the following 12 genes: ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, NBN, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, TP53. Gene-targeted enrichment was performed following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Massively parallel sequencing was carried out using the MiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA), achieving an average read depth of 500X. FASTQ outcomes analysis was performed using CE-IVD-certified Amplicon Suite bioinformatic analysis software (SmartSeq srl, Novara, Italy).

2.3. Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA)

Verification of predicted LGRs was carried out on genomic DNA (gDNA) patient’s samples using the SALSA MLPA P260 PALB2-RAD50-RAD51C-RAD51D Probe mix (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The amplicons were analyzed on SeqStudio genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystem, Thermo Fisher, Monza, Italy), and data were processed using Coffalyser.Net software (MRC Holland).

2.4. RNA Workflow

RNA was isolated from peripheral blood using PAXgene® blood RNA tubes (BD Biosciences) and extracted using PAXgene® blood RNA Kit Pre Analytix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), with DNase treatment as per manufacturer's instructions. Extracted RNA samples were quantified using NanoDrop® ND-1000 (NanoDrop® Technologies) spectrophotometer, followed by a confirmatory quantification with Qubit High Sensitivity (HS) Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kit from Invitrogen™ containing a genetically modified MMLV SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase to improve its performance. The cDNA was then amplified using primers designed to target exon 11 deletions and duplication (forward on exon 9: 5′ TGGGACCCTTTCTGATCAAC 3′; reverse on exon 12: 5′ TGCCCTGGAGGAAGACAGTA 3′). PCR amplification was performed using the Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase kit (QIAGEN). PCR products were verified on 2% agarose gel, visualized by ethidium bromide staining and sequenced by Sanger Sequencing.

2.5. Sequencing Analysis of Gene Deletion Breakpoints

To amplify expected breakpoints of the gene rearrangements identified by NGS and MLPA analyses, forward and reverse primer pairs were designed, respectively, on the intronic 10 and 11 regions lacking

Alu sequences, which were masked using the online RepeatMasker tool (URL:

https://www.repeatmasker.org/). Primer sequences are given on request.

Long-range PCRs were performed using the Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) and PCR products were sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

Briefly, PCR products were sequenced on SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer sequencer (Applied Biosystems) using BigDye Terminator Chemistry (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. The results were analyzed with the SeqScanner 2 and SeqScape v2.6 software (Applied Biosystems).

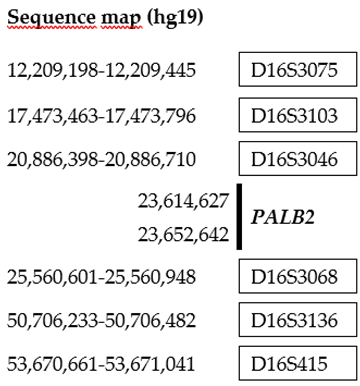

2.6. Microsatellite Analysis and Haplotyping

Microsatellites on chromosome 16, flanking

PALB2, were investigated using microsatellites D16S3075, D16S3103, D16S3046, D16S3068, D16S3136 and D16S415 from the ABI PRISM Linkage Mapping set version 2.5 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (

Table 1). The amplification products were separated by capillary electrophoresis on a SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using the Gene Mapper 6.0 software (Applied Biosystems).

A total of seven individual, carriers of the PALB2 exon 11 deletion, were genotyped. Haplotypes were constructed manually from microsatellite analyses, assuming the least number of possible recombinations.

2.7. Interpretation of Variants

Mutation nomenclature follows the Human Genome Variation Society (

https://hgvs-nomenclature.org/stable/) recommendations [

34]. The DNA mutation numbering is based on the

PALB2 cDNA sequences (NM_024675.3) with the A of the ATG translation-initiation codon numbered as +1. Amino acid numbering starts with the translation initiator methionine as +1.

3. Results

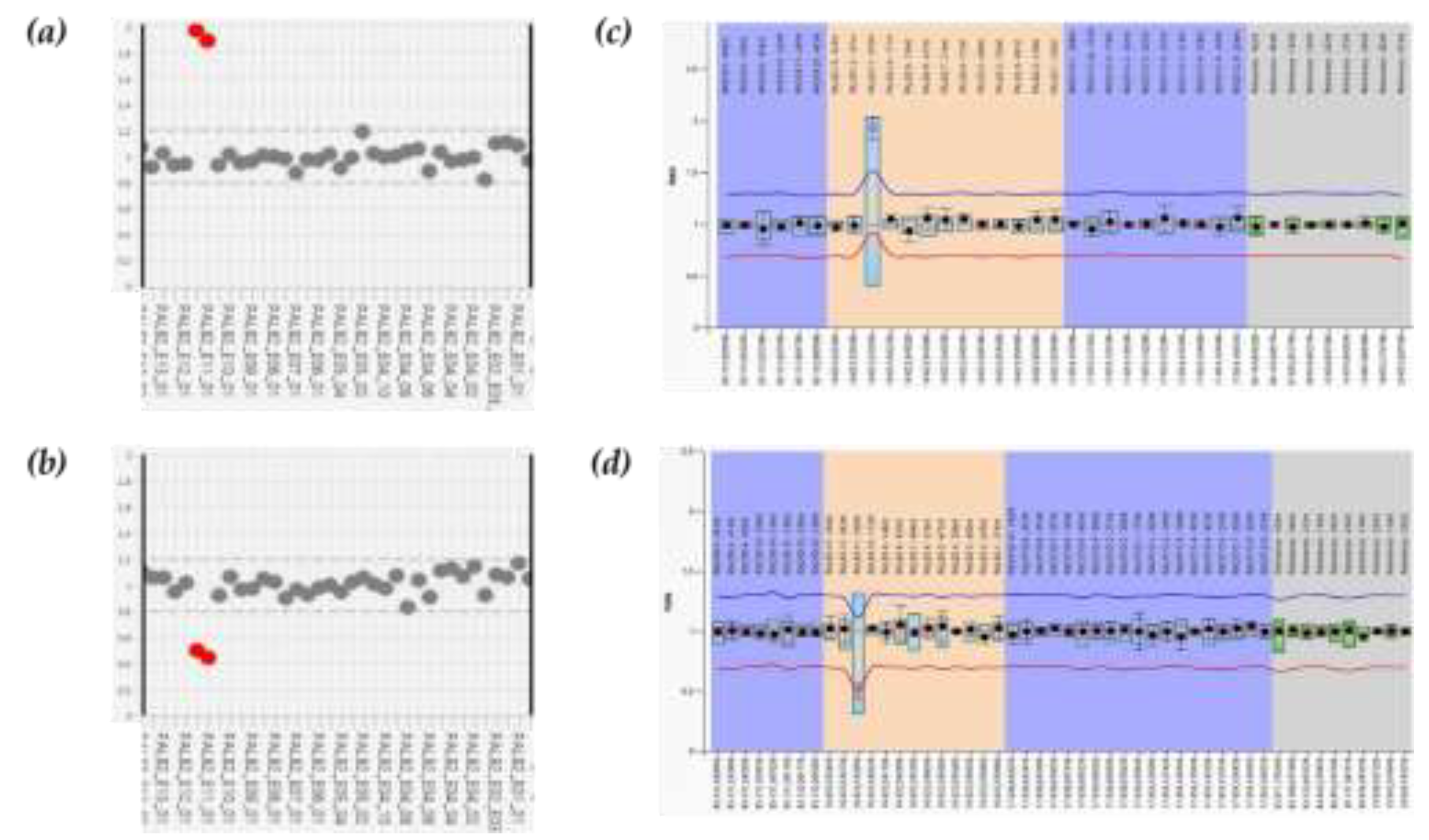

3.1. NGS Analysis and MLPA LGRs Confirmation

Four women were referred to our laboratory due to their medical history, which was noticeable by several HBOC-related cancers also affecting other family members. Initial genetic screening for BRCA1 and BRCA2 did not reveal any mutations in these genes. Thus, to identify the potential presence of PVs in additional syndrome-associated genes that could explain the clinical phenotype, we analyzed the patient’s DNAs using the Devyser HBOC genes panel assay. The results of NGS analysis revealed large rearrangements involving exon 11 of PALB2 gene in all four patients. Patient 1 exhibited a duplication of PALB2 exon 11 (

Figure 2a), while the other three had a deletion of PALB2 exon 11 (

Figure 2b). To validate the identified rearrangements, we performed MLPA that confirmed their presence (

Figure 2c and 2d).

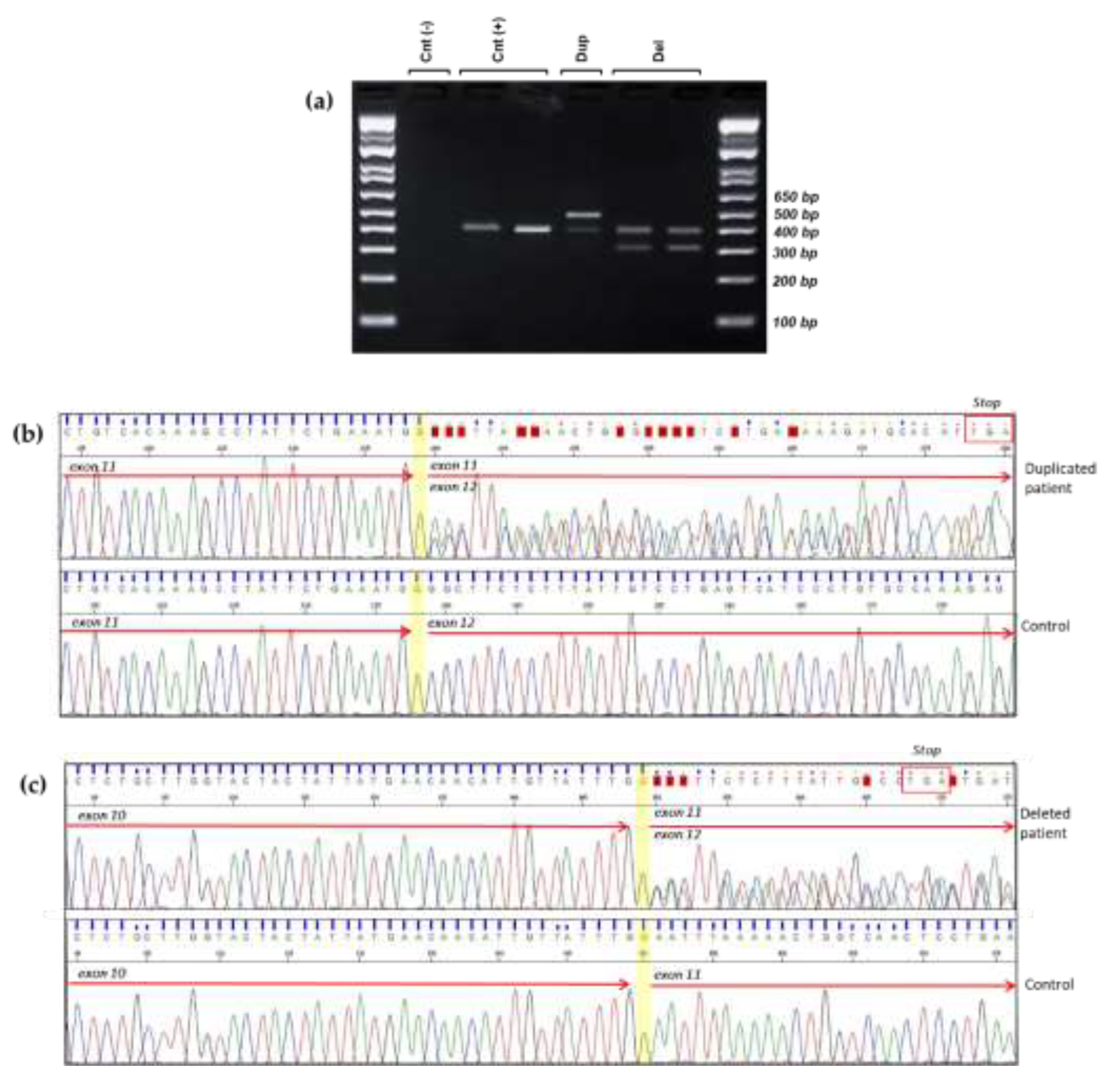

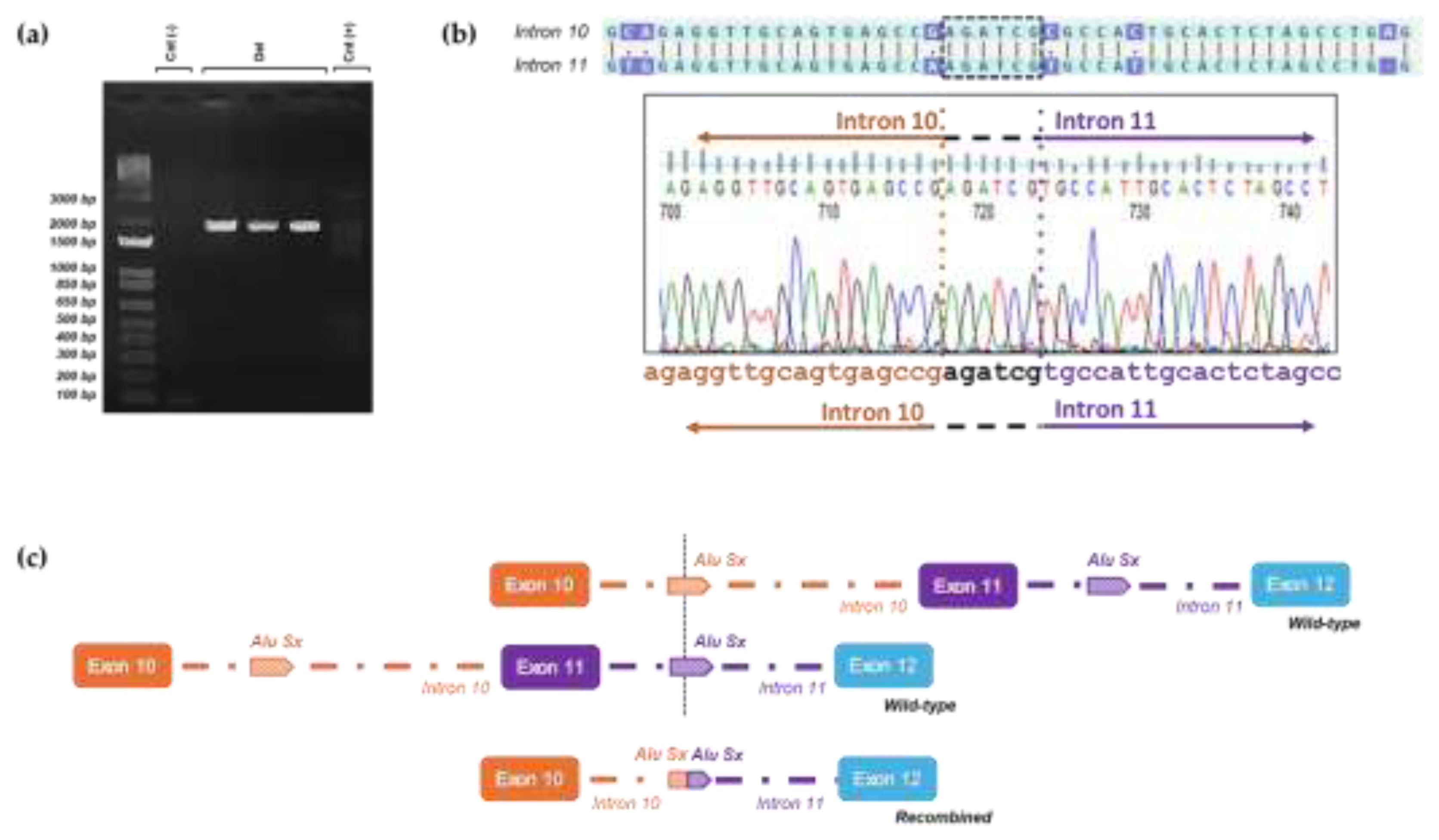

3.2. Transcript Analysis

To evaluate the consequences of the identified LGRs at the transcriptomic level, we designed primers that specifically targeted the region of interest in the cDNA. The forward primer was positioned approximately 30 base pairs from the 3'-end of exon 9, while the reverse primer was situated in the middle of exon 12. A distinct 486 bp PCR amplification was observed in the sample with duplication, whereas 310 bp PCR amplification was evident in the probands' samples with deletion (

Figure 3a). A 398 bp PCR amplification product was detected in the control samples, which matched the wild type allele PCR amplifications of the probands (

Figure 3a).

Sanger sequencing of the duplicated cDNA amplification product confirmed that the duplication was in direct orientation and out-frame. Therefore the variant could be described as follows: c.(3113+1_3114-1)_(3201+1_3202-1)dup, r.3114_3201dup, p.(Gly1068Glufs*14) (

Figure 3b).

Sequencing of the deleted cDNA samples also revealed an aberrant transcript product, showing the complete deletion of exon 11 and resulting in a frameshift: c.(3113+1_3114-1)_(3201+1_3202-1)del, r.3114_3201del, p.(Asn1039Glyfs*7) (

Figure 3c).

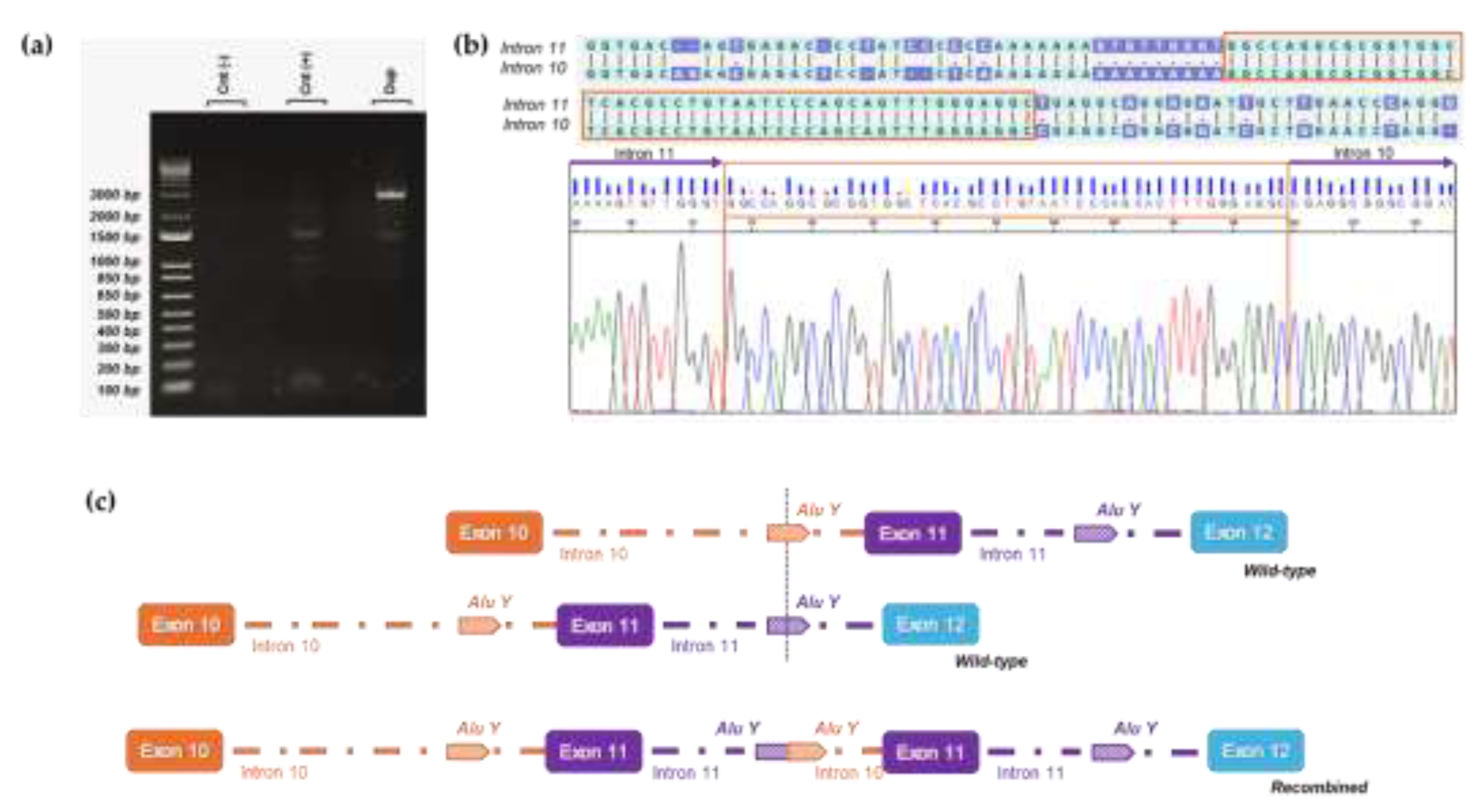

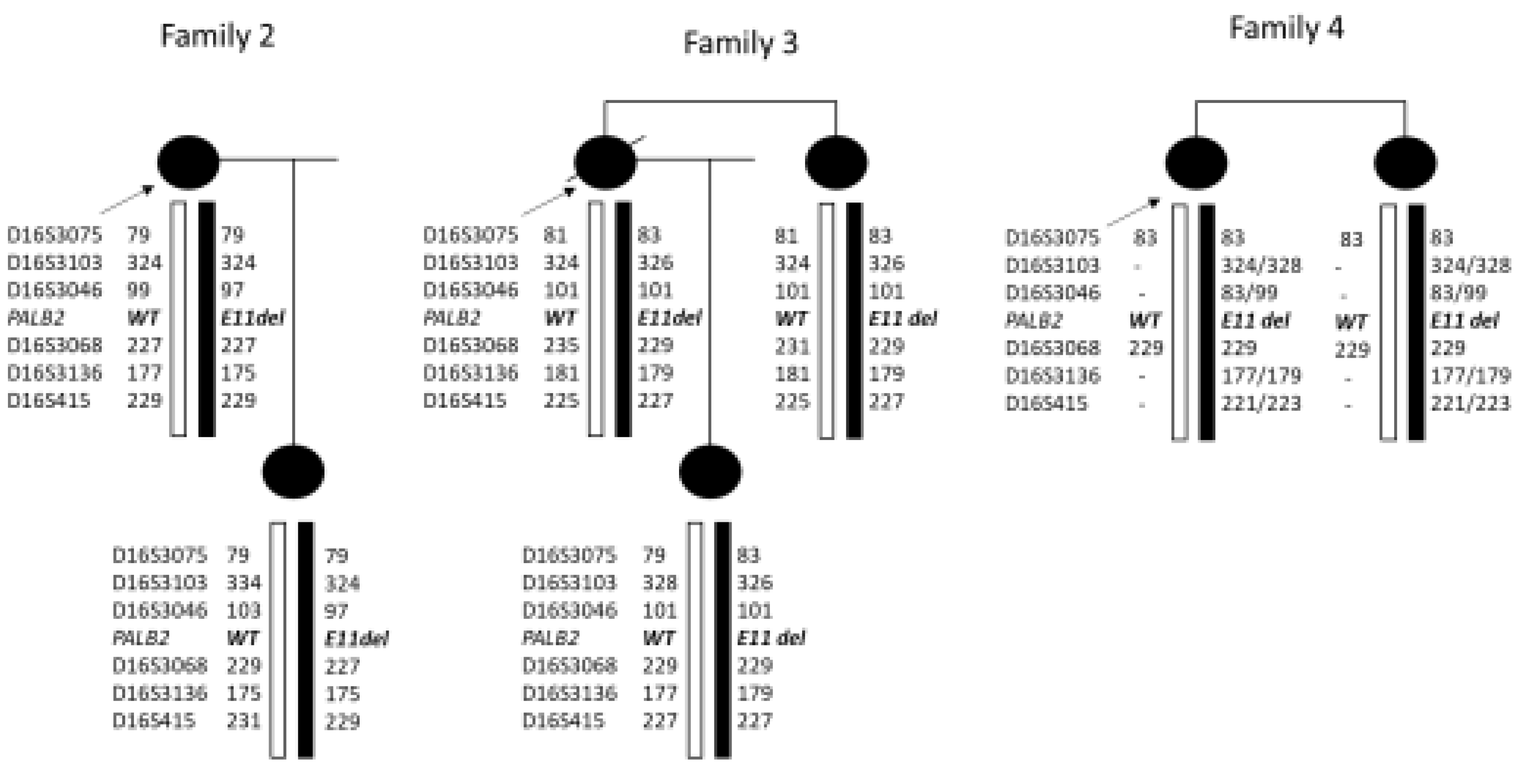

3.3. Breakpoints Identification of Exon 11 LGRs

To comprehend the molecular mechanism underlying the rearrangements identified in our patients, we employed two distinct strategies to accurately determine the intronic breakpoints in our deletion and duplication cases, respectively.

Regarding the duplicated case, we found the same breakpoints described by Bouras et al. [

28]. Using a forward primer on intron 11 and a reverse primer on intron 10 [

28] we obtained a PCR amplicon of about 2500 bp (

Figure 4a). Sanger sequencing identified the proximal breakpoint of the duplication in an AluY element on intron 10 while the distal breakpoint was located in a highly homologous AluY on intron 11, with an overlapping sequence between the two introns of 47 base pairs (

Figure 4b). The rearrangement resulted in a duplicated region of 5134 bp involving exon 11 and allowing the accurate description of the duplication at DNA level c.(3114-811_3202-1756)dup.

In the deleted samples, we applied a primer-walking strategy on intron 10 and intron 11. One of the primer pairs used, respectively positioned near the 5' end of exon 10 and the 3' end of exon 11, resulted in a 2000-base pairs amplification product exclusively in the three deleted samples (

Figure 5a). Sanger sequencing of the 2000-base pairs amplicons was used to delineate the deletion breakpoints (

Figure 5b). The three patients carried the same deletion that can be described as c.(3114-5317_3202-3194)del at DNA level. Both breakpoints were located in highly homologous AluSx repeat regions positioned in intron 10 and intron 11, and the rearrangement caused a deletion of about 8050 base pairs leading to the complete loss of exon 11.

3.4. Haplotype Analysis

Haplotype analysis for chromosome 16 markers in the families clearly indicates that Family 2 and 3 do not share the same haplotype on the deleted chromosome. In family 4, was not possible to clearly define the affected haplotype, but some of the alleles were not compatible with a haplotype shared with the two other families (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

Our comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analyses clarified the crucial role of Alu sequences to determine pathogenic large genomic rearrangements involving PALB2 exon 11 in patients from Tuscany (Italy). In particular, we discovered a recurrent deletion [c.(3114-5317_3202-3194)del] in three different HBOC families and a duplication of the same exon in a fourth family [c.(3114-811_3202-1756)dup]. These out-frame deletions and duplication create a premature stop codon predicted to cause nonsense-mediated-decay.

In the present study, the breakpoints of the two large rearrangements within the

PALB2 gene were also characterized. Sequence analysis of the three families carrying the exon 11 deletion was performed and the probands shared identical breakpoint positions and sequences. Furthermore, the breakpoints of the duplication were the same of the one described by Bouras et al. in a patient from France [

28].

There are two possible reasons why the breakpoints were identical in all families with the same rearrangement: it could be the result of either a founder mutation in the population of Tuscany or a recurrent rearrangement mediated by the same microhomology region within the similar pair of Alu repeats in each family.

In the deletion cases, we excluded a founder effect since the microsatellite analysis performed in the deleted families suggested that they did not share the same haplotype associated with the rearrangement.

Germline rearrangements of

PALB2 represent a minor proportion of all genetic alterations associated with HBOC disorder, however their identification provides important data for genetic counselling. The predilection for rearrangements involving exon 11 is intrinsically linked to the increased presence of

Alu repeats within the region of the

PALB2 gene. Indeed, the

PALB2 gene lies on the short arm of human chromosome 16 and presents a high percentage of repeat elements.

Alu repeats account for 64% of the

PALB2 intronic region, reaching 73% of the genomic sequence outside the exon–intron junctions. Essentially, these sequences offer many opportunities for homologous recombination, and nonallelic homologous recombination represents a common disease-causing mechanism associated with genome rearrangements [

35]. We identified two Alu sequences located around the breakpoint junctions: 1) an

AluSx within intron 10 and another one in intron 11 in the deleted patients and 2)

AluY repeats respectively in intron 10 and 11 of the

PALB2 gene involved in the duplication. Therefore, our findings support the hypothesis that homologous recombination events underlie the identified rearrangements. Given its frequency, the deletion of exon 11 might represent a mutational “hotspot” of

PALB2 at least in the population of Tuscany; it might be particularly interesting to test the breakpoints in the other deletion cases described in the literature [

29,

32] to check if they involve the same pair of

AluSx repeats. Likewise, the breakpoints identified in the exon 11 duplication were the same of those already reported in the literature [

28,

31] highlighting the possibility of another rearrangement hot-spot involving

AluY. Although all

Alu repeats have an average of 85% homology [

36], the two

AluY repeats involved in the duplication are extremely homologous, having 92.17% identity, suggesting that recombination involving this pair may be particularly favorable.

In summary, this study highlights the noteworthy instability of intronic regions flanking exon 11 of PALB2 and identifies a previously unreported hotspot involving Alu repeats with very high sequence homology in introns 10 and 11 of the gene.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study showed that the method routinely adopted in our laboratory for the molecular diagnosis of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer, led to the identification of recurrent rearrangements involving exon 11 of PALB2 in Italian families, therefore contributing to extend the mutational PALB2 landscape in our population.

Author Contributions

D.S., M.M. and L.P. were responsible for study design and conceptualization; D.S., V.M., D.C., M.M. conducted the experiments, C.B., F.G. and E.F. were responsible for clinical part of the manuscript, D.S. and L.P. were responsible for the writing of the manuscript and finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval was required as the testing was performed according to medical indication, as part of standard care.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Maxwell, K.N.; Churpek, J.; Kohlmann, W.; AlHilli, Z.; Arun, B.; Buys, S.S.; Cheng, H.; Domchek, S.M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2024: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2023, 21, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, A.; Turashvili, G. Pathology of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 531790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barili, V.; Ambrosini, E.; Bortesi, B.; Minari, R.; De Sensi, E.; Cannizzaro, I.R.; Taiani, A.; Michiara, M.; Sikokis, A.; Boggiani, D.; et al. Genetic Basis of Breast and Ovarian Cancer: Approaches and Lessons Learnt from Three Decades of Inherited Predisposition Testing. Genes 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piombino, C.; Cortesi, L.; Lambertini, M.; Punie, K.; Grandi, G.; Toss, A. Secondary Prevention in Hereditary Breast and/or Ovarian Cancer Syndromes Other Than BRCA. J Oncol 2020, 2020, 6384190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Nassiri, M.; Kooshyar, M.M.; Vakili-Azghandi, M.; Avan, A.; Sandry, R.; Pillai, S.; Lam, A.K.-Y.; Gopalan, V. Hereditary Breast Cancer; Genetic Penetrance and Current Status with BRCA. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 5741–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, R. Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC): Review of Its Molecular Characteristics, Screening, Treatment, and Prognosis. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, V.; Bucalo, A.; Conti, G.; Celli, L.; Porzio, V.; Capalbo, C.; Silvestri, V.; Ottini, L. Gender-Specific Genetic Predisposition to Breast Cancer: BRCA Genes and Beyond. Cancers 2024, 16, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, O.; Nowak, K.M. Gene of the Month: PALB2. J Clin Pathol 2023, 76, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischkowitz, M.; Balmaña, J.; Foulkes, W.D.; James, P.; Ngeow, J.; Schmutzler, R.; Voian, N.; Wick, M.J.; Stewart, D.R.; Pal, T.; et al. Management of Individuals with Germline Variants in PALB2: A Clinical Practice Resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 2021, 23, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zethoven, M.; McInerny, S.; Healey, E.; DeSilva, D.; Devereux, L.; Scott, R.J.; James, P.A.; Campbell, I.G. Contribution of Large Genomic Rearrangements in PALB2 to Familial Breast Cancer: Implications for Genetic Testing. J Med Genet 2023, 60, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Sheng, Q.; Nakanishi, K.; Ohashi, A.; Wu, J.; Christ, N.; Liu, X.; Jasin, M.; Couch, F.J.; Livingston, D.M. Control of BRCA2 Cellular and Clinical Functions by a Nuclear Partner, PALB2. Mol Cell 2006, 22, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, N.; Seal, S.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, P.; Renwick, A.; Elliott, A.; Reid, S.; Spanova, K.; Barfoot, R.; Chagtai, T.; et al. PALB2, Which Encodes a BRCA2-Interacting Protein, Is a Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisson, R.; Niraj, J.; Pauty, J.; Maity, R.; Zhao, W.; Coulombe, Y.; Sung, P.; Masson, J.-Y. Breast Cancer Proteins PALB2 and BRCA2 Stimulate Polymerase η in Recombination-Associated DNA Synthesis at Blocked Replication Forks. Cell Rep 2014, 6, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, S.M.H.; Huen, M.S.Y.; Chen, J. PALB2 Is an Integral Component of the BRCA Complex Required for Homologous Recombination Repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 7155–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Dorsman, J.C.; Ameziane, N.; De Vries, Y.; Rooimans, M.A.; Sheng, Q.; Pals, G.; Errami, A.; Gluckman, E.; Llera, J.; et al. Fanconi Anemia Is Associated with a Defect in the BRCA2 Partner PALB2. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Luo, M.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of PALB2 Function and Its Role in Breast Cancer Management. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milletti, G.; Strocchio, L.; Pagliara, D.; Girardi, K.; Carta, R.; Mastronuzzi, A.; Locatelli, F.; Nazio, F. Canonical and Noncanonical Roles of Fanconi Anemia Proteins: Implications in Cancer Predisposition. Cancers 2020, 12, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Kitago, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Hirasawa, A. Hereditary Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2021, 26, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toss, A.; Ponzoni, O.; Riccò, B.; Piombino, C.; Moscetti, L.; Combi, F.; Palma, E.; Papi, S.; Tenedini, E.; Tazzioli, G.; et al. Management of PALB2 -associated Breast Cancer: A Literature Review and Case Report. Clinical Case Reports 2023, 11, e7747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pös, O.; Radvanszky, J.; Buglyó, G.; Pös, Z.; Rusnakova, D.; Nagy, B.; Szemes, T. DNA Copy Number Variation: Main Characteristics, Evolutionary Significance, and Pathological Aspects. Biomed J 2021, 44, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, I.O.; Chabert, A.; Guignard, T.; Puechberty, J.; Cabello-Aguilar, S.; Pujol, P.; Vendrell, J.A.; Solassol, J. Characterizing PALB2 Intragenic Duplication Breakpoints in a Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Case Using Long-Read Sequencing. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1355715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozsik, A.; Pócza, T.; Papp, J.; Vaszkó, T.; Butz, H.; Patócs, A.; Oláh, E. Complex Characterization of Germline Large Genomic Rearrangements of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genes in High-Risk Breast Cancer Patients-Novel Variants from a Large National Center. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, C.; Nardelli, C.; Concolino, P.; Pagliuca, M.; Setaro, M.; De Paolis, E.; De Placido, P.; Forestieri, V.; Scaglione, G.L.; Ranieri, A.; et al. Case Report: Detection of a Novel Germline PALB2 Deletion in a Young Woman With Hereditary Breast Cancer: When the Patient’s Phenotype History Doesn’t Lie. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 602523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, A.; Hoya, M. de la; Balmaña, J.; Cajal, T.R.Y.; Teule, A.; Miramar, M.D.; Esteban, E.M.A.; Infante, M.; Benítez, J.; Torres, A.; et al. Detection of a Large Rearrangement in PALB2 in Spanish Breast Cancer Families with Male Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2012, 132, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Arnold, A.G.; Trottier, M.; Sonoda, Y.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Zivanovic, O.; Robson, M.E.; Stadler, Z.K.; Walsh, M.F.; Hyman, D.M.; et al. Characterization of a Novel Germline PALB2 Duplication in a Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Family. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 160, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischkowitz, M.D.; Sabbaghian, N.; Hamel, N.; Borgida, A.; Rosner, C.; Taherian, N.; Srivastava, A.; Holter, S.; Rothenmund, H.; Ghadirian, P.; et al. Analysis of the Gene Coding for the BRCA2-Interacting Protein PALB2 in Familial and Sporadic Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shi, J.; Cai, Q.; Shu, X.-O.; He, J.; Wen, W.; Allen, J.; Pharoah, P.; Dunning, A.; Hunter, D.J.; et al. Use of Deep Whole-Genome Sequencing Data to Identify Structure Risk Variants in Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, A.; Lafaye, C.; Leone, M.; Kherraf, Z.-E.; Martin-Denavit, T.; Fert-Ferrer, S.; Calender, A.; Boutry-Kryza, N. Identification and Characterization of an Exonic Duplication in PALB2 in a Man with Synchronous Breast and Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, H.; Nagy, P.; Papp, J.; Bozsik, A.; Grolmusz, V.K.; Pócza, T.; Oláh, E.; Patócs, A. PALB2 Variants Extend the Mutational Profile of Hungarian Patients with Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepkes, L.; Kayali, M.; Blümcke, B.; Weber, J.; Suszynska, M.; Schmidt, S.; Borde, J.; Klonowska, K.; Wappenschmidt, B.; Hauke, J.; et al. Performance of In Silico Prediction Tools for the Detection of Germline Copy Number Variations in Cancer Predisposition Genes in 4208 Female Index Patients with Familial Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.E.; Chong, H.; Mu, W.; Conner, B.R.; Hsuan, V.; Willett, S.; Lam, S.; Tsai, P.; Pesaran, T.; Chamberlin, A.C.; et al. DNA Breakpoint Assay Reveals a Majority of Gross Duplications Occur in Tandem Reducing VUS Classifications in Breast Cancer Predisposition Genes. Genet Med 2019, 21, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Leslie, G.; Doroszuk, A.; Schneider, S.; Allen, J.; Decker, B.; Dunning, A.M.; Redman, J.; Scarth, J.; Plaskocinska, I.; et al. Cancer Risks Associated With Germline PALB2 Pathogenic Variants: An International Study of 524 Families. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janatova, M.; Kleibl, Z.; Stribrna, J.; Panczak, A.; Vesela, K.; Zimovjanova, M.; Kleiblova, P.; Dundr, P.; Soukupova, J.; Pohlreich, P. The PALB2 Gene Is a Strong Candidate for Clinical Testing in BRCA1- and BRCA2-Negative Hereditary Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013, 22, 2323–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Dunnen, J.T.; Dalgleish, R.; Maglott, D.R.; Hart, R.K.; Greenblatt, M.S.; McGowan-Jordan, J.; Roux, A.-F.; Smith, T.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Taschner, P.E.M. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum Mutat 2016, 37, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weckselblatt, B.; Rudd, M.K. Human Structural Variation: Mechanisms of Chromosome Rearrangements. Trends Genet 2015, 31, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.R.; Batzer, M.A.; Deininger, P.L. Evolution of the Master Alu Gene(s). J Mol Evol 1991, 33, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of individuals with PALB2 rearrangements. (a) Family of patient 1, carrier of exon 11 duplication. (b), (c), and (d) Pedigrees of the three carriers of exon 11 deletion. The index case is indicated by an arrow.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of individuals with PALB2 rearrangements. (a) Family of patient 1, carrier of exon 11 duplication. (b), (c), and (d) Pedigrees of the three carriers of exon 11 deletion. The index case is indicated by an arrow.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive analysis of the PALB2 gene. (a, b) CNV analysis by Amplicon Suite software for woman carriers of duplication and deletion of PALB2 exon 11. Plot of PALB2 amplicons which show an increase of around 1,8- 2 value of coverage in exon 11 (a), and a reduction of about 0,5 value of coverage in exon 11 (b); amplicon coverage of the others PALB2 exons ranges to normal range (0,8- 1,2), with a homogeneous distribution pattern of each amplicon. (c, d) MLPA assay of PALB2 in carriers of exon 11 duplication (c) and deletion (d). Each dot represents the mean amplification ratio of specific region probes, reflecting the relative amount of the targeted DNA segment compared to a reference sample. Error bars show the standard deviation of the measured ratio. The ratio is calculated for each probe and indicates whether there is a deletion (ratio <0.5), duplication (c) (ratio >1,5) (d), or no change (ratio ≈1).

Figure 2.

Comprehensive analysis of the PALB2 gene. (a, b) CNV analysis by Amplicon Suite software for woman carriers of duplication and deletion of PALB2 exon 11. Plot of PALB2 amplicons which show an increase of around 1,8- 2 value of coverage in exon 11 (a), and a reduction of about 0,5 value of coverage in exon 11 (b); amplicon coverage of the others PALB2 exons ranges to normal range (0,8- 1,2), with a homogeneous distribution pattern of each amplicon. (c, d) MLPA assay of PALB2 in carriers of exon 11 duplication (c) and deletion (d). Each dot represents the mean amplification ratio of specific region probes, reflecting the relative amount of the targeted DNA segment compared to a reference sample. Error bars show the standard deviation of the measured ratio. The ratio is calculated for each probe and indicates whether there is a deletion (ratio <0.5), duplication (c) (ratio >1,5) (d), or no change (ratio ≈1).

Figure 3.

Large genomic rearrangements disrupt normal splicing, leading to frameshift mutations. (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) conducted on mRNA isolated from patients and non-carrier controls. Cnt (-): No cDNA control; Cnt (+): Wild-type band of 398 bp from healthy cDNA control; Dup: An additional band (486 bp) was observed in cDNA from Patient1, who has an exon 11 duplication; Del: An extra band (310 bp) was detected in cDNA from Patients 2 and 3, both of whom have an exon 11 deletion. (b) Sanger sequencing of the two alleles from the RT-PCR product of Patient1 (duplication): The insertion results in the formation of an early stop codon, as indicated in the red box. (c) Sanger sequencing of the two alleles from the RT-PCR products of the deleted patients: exon 11 deletion leads to a premature stop codon, as highlighted in the red box.

Figure 3.

Large genomic rearrangements disrupt normal splicing, leading to frameshift mutations. (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) conducted on mRNA isolated from patients and non-carrier controls. Cnt (-): No cDNA control; Cnt (+): Wild-type band of 398 bp from healthy cDNA control; Dup: An additional band (486 bp) was observed in cDNA from Patient1, who has an exon 11 duplication; Del: An extra band (310 bp) was detected in cDNA from Patients 2 and 3, both of whom have an exon 11 deletion. (b) Sanger sequencing of the two alleles from the RT-PCR product of Patient1 (duplication): The insertion results in the formation of an early stop codon, as indicated in the red box. (c) Sanger sequencing of the two alleles from the RT-PCR products of the deleted patients: exon 11 deletion leads to a premature stop codon, as highlighted in the red box.

Figure 4.

Breakpoint characterization of exon 11 PALB2 duplication. (a) Long-range PCR shows a specific band of approximately 2.5 kb detected only in the proband’s gDNA (Dup) sample and absent in control gDNA samples [Cnt(-), Cnt(+)]. (b) Electropherogram showing the breakpoint sequence (forward) where a tandem duplication site of 47 base pairs (TDS) is boxed in orange. (c) Schematic representation illustrates how wild-type alleles recombine in an unconventional manner via the AluY sequences located in introns 10 and 11, ultimately resulting in the formation of the deletion allele.

Figure 4.

Breakpoint characterization of exon 11 PALB2 duplication. (a) Long-range PCR shows a specific band of approximately 2.5 kb detected only in the proband’s gDNA (Dup) sample and absent in control gDNA samples [Cnt(-), Cnt(+)]. (b) Electropherogram showing the breakpoint sequence (forward) where a tandem duplication site of 47 base pairs (TDS) is boxed in orange. (c) Schematic representation illustrates how wild-type alleles recombine in an unconventional manner via the AluY sequences located in introns 10 and 11, ultimately resulting in the formation of the deletion allele.

Figure 5.

Breakpoint characterization of exon 11 PALB2 deletion. (a) Long-range PCR analysis revealed a 2 kb deletion product only in the gDNA deleted samples (Del), whereas healthy control samples exhibited no such product [Cnt(-), Cnt(+)]43. (b) Sanger sequencing of the 2 kb PCR product identifies the breakpoints regions of the rearrangement, characterized by a distinctive six-nucleotide element, AGATCG, that overlaps both breakpoints. (c) Schematic representation illustrates how wild-type alleles recombine in an unconventional manner via the AluSx sequences located in introns 10 and 11, ultimately resulting in the formation of the deletion allele.

Figure 5.

Breakpoint characterization of exon 11 PALB2 deletion. (a) Long-range PCR analysis revealed a 2 kb deletion product only in the gDNA deleted samples (Del), whereas healthy control samples exhibited no such product [Cnt(-), Cnt(+)]43. (b) Sanger sequencing of the 2 kb PCR product identifies the breakpoints regions of the rearrangement, characterized by a distinctive six-nucleotide element, AGATCG, that overlaps both breakpoints. (c) Schematic representation illustrates how wild-type alleles recombine in an unconventional manner via the AluSx sequences located in introns 10 and 11, ultimately resulting in the formation of the deletion allele.

Figure 6.

Haplotype analysis for chromosome 16 markers in the families clearly indicates that Family 2 and 3 do not share the same haplotype on the deleted chromosome. In family 4, was not possible to clearly define the affected haplotype, but some of the alleles were not compatible with an haplotype shared with the two other families.

Figure 6.

Haplotype analysis for chromosome 16 markers in the families clearly indicates that Family 2 and 3 do not share the same haplotype on the deleted chromosome. In family 4, was not possible to clearly define the affected haplotype, but some of the alleles were not compatible with an haplotype shared with the two other families.

Table 1.

Position of STS markers and

PALB2 gene on chromosome 16 was established using the UCSC Genome Browser (

http://genome.ucsc.edu).

Table 1.

Position of STS markers and

PALB2 gene on chromosome 16 was established using the UCSC Genome Browser (

http://genome.ucsc.edu).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).