1. Introduction

Shannon has developed a historically groundbreaking theory for evaluating cryptographic functionality, utilizing his own entropy theory to analyze whether a cipher is decipherable [

1]. On the other hand, Shannon offers two important cautions for applications to the real world. One is that entropy does not cover all the information that humans deal with, so to discuss indecipherability, one should carefully consider its limits. The other is that a principle always has ancillary conditions, and when one speaks of a principle, one should carefully take into account its ancillary conditions. Massey, on the other hand, offered a cryptographic direction that addresses real-world challenges while respecting the Shannon’s concept [

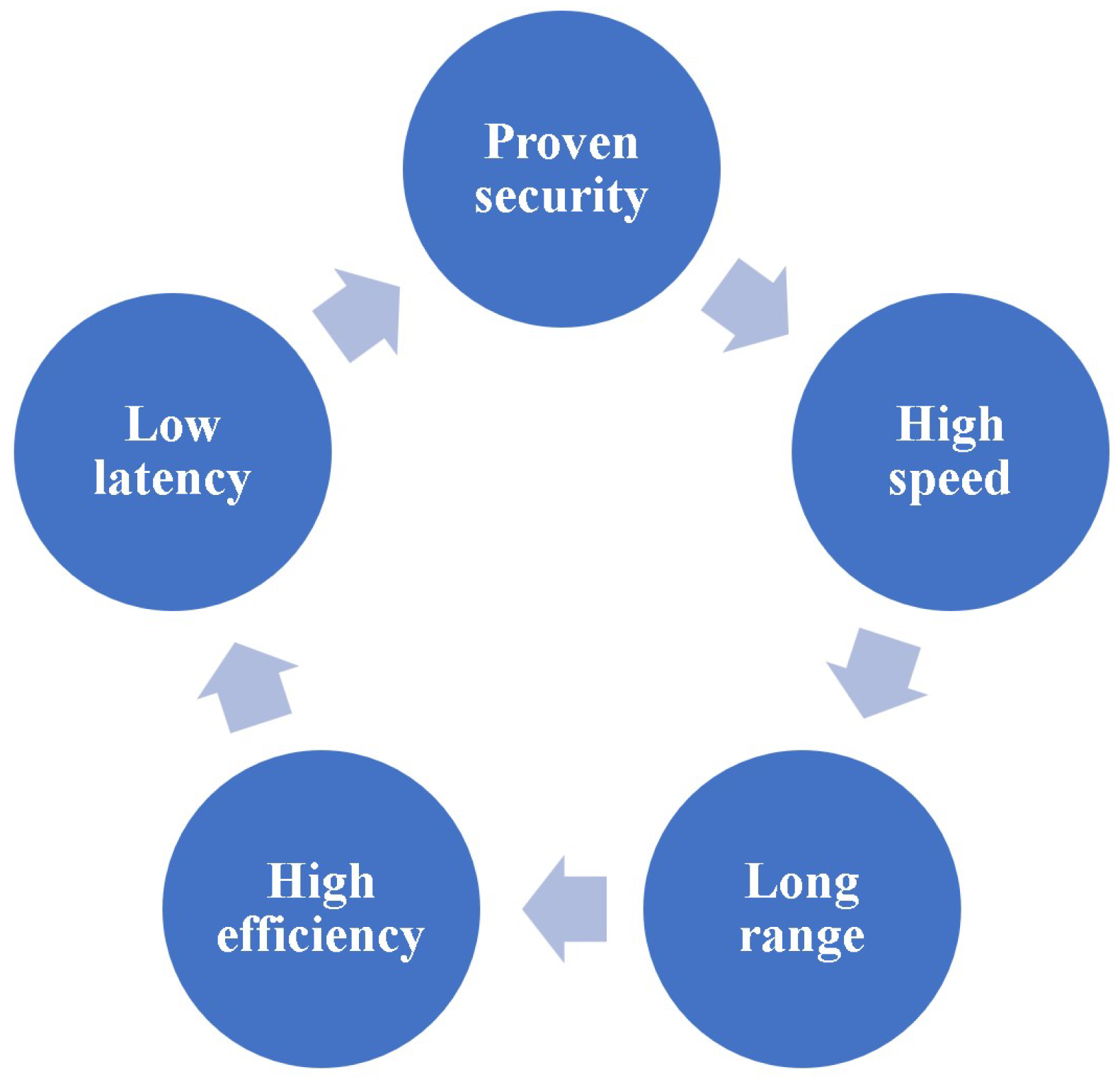

2]. The conditions that a cipher for information theoretic data encryption corresponding to the real world should have are given in the

Figure 1. It is essential that the ciphers actually used satisfy the above in a balanced manner.

Massey suggested a concept to realize the above conditions as a technology as follows:

(1). A short symmetric key is set, and it is mathematically extended.

(2). Private randomization techniques is useful.

(3). Randomization for plaintext is a candidate of private randomization.

Unfortunately, these can only be used for immunity against ciphertext-only attacks, and the theoretical system has only gone so far as to justify inefficient one time pad cipher as its ultimate goal. Modern mathematical cryptography requires at least a guarantee of computational security against known-plaintext attacks. Thus, it was considered a difficult question whether or not information-theoretic cipher can guarantee immunity against known-plaintext attacks.

To solve the above problem, H.P.Yuen established the basic concept of a new cipher under the collaboration of P.Kumar and O.Hirota, and he disclosed a physical example in a white paper of 2000 and an experimental result in the QCMC of 2002 with Kumar group [

3]. It is called quanum stream cipher at present. More detailed name is a quantum noise randomized stream cipher operated by Y-00 protocol.

His idea consiste of the following structure to satisfy Massey’s conditions on utility:

Figure 1

(1). A short symmetric key is set and it is mathematically extended.

(2). Randomization techniques for ciphertext are adopted.).

(3). The randomization is implemented as private randomization.

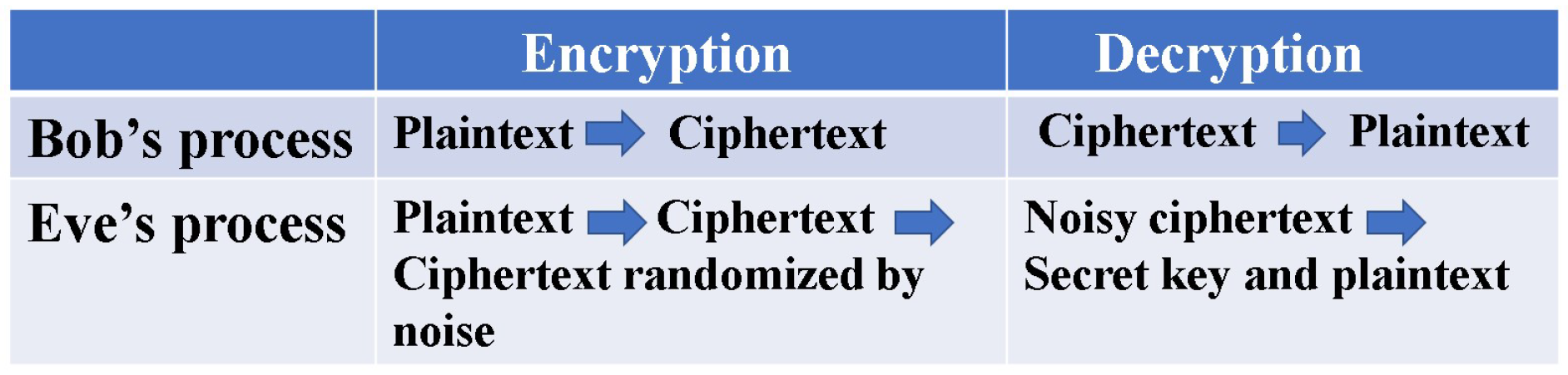

The crucial difference between Massey and Yuen is that the randomisation moves from plaintext to ciphertext (See

Figure 2). To realise these configurations, Yuen proposed a scheme based on communication theory to differentiate between the signal detection capabilities of the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper. This is called advantage creation by secret key. The way to do this is to adopt a communication scheme such that the ciphertext received by the eavesdropper is hidden by quantum noise. Such a principle is called keyed communication in quantum noise (KCQ). This principle leads to a situation where the ciphertexts that can be received by receivers for legitimate communicator and eavesdropper are different (See

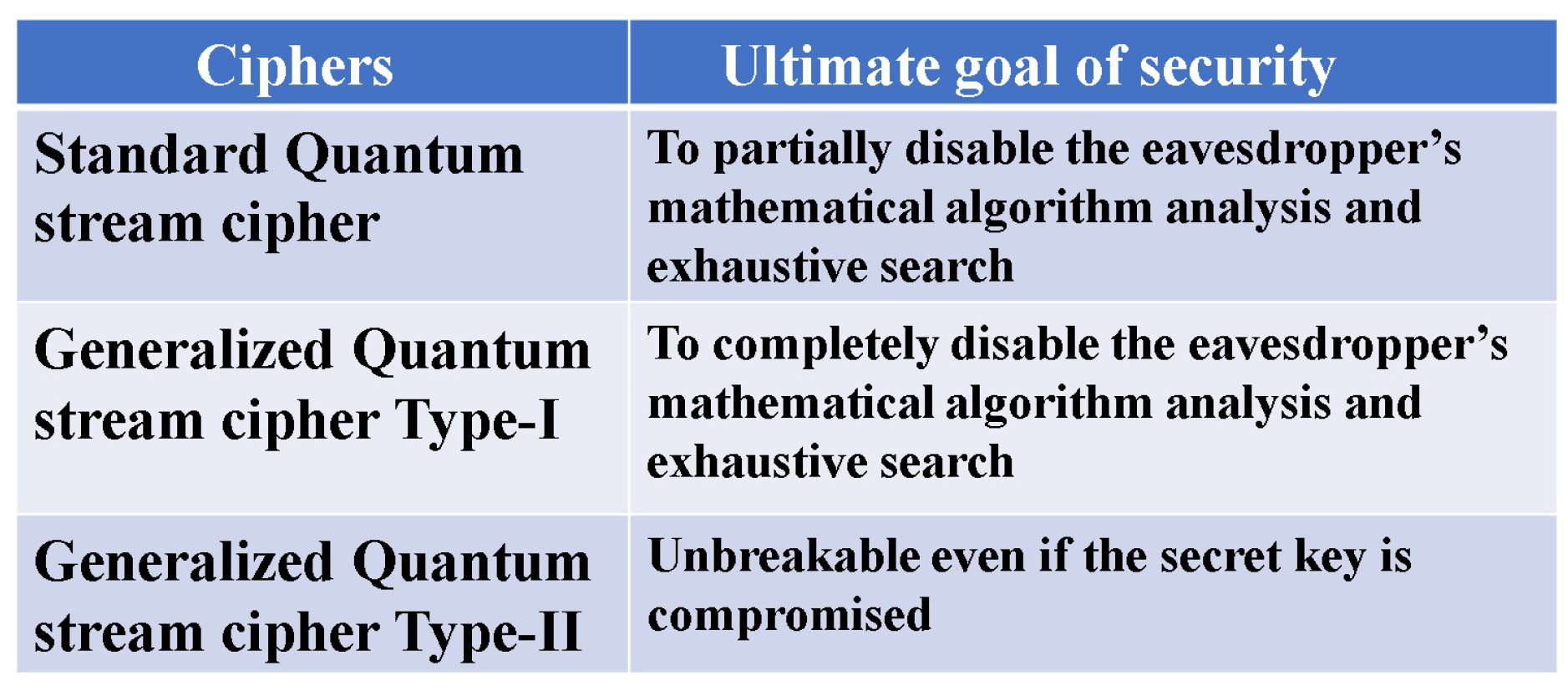

Figure 3).

Applications of such a physical encryption technique appear to be limited, not general communication networks. But to diversify communication functions, quantum stream cipher which utilizes physical phenomena is beginning to be considered for the ultrafast optical backborn network by several industries. However, this cryptographic technique has extremely complicated mechanisms, and some aspects have emerged that are difficult to communicate even among experts in cryptography. The first paper in 2022 with the same title [

4] has explained the position of quantum stream cipher from a broad perspective as a cryptographic technique. In this second paper, we introduce the principles of security guarantees for quantum stream cipher. Then we describe the theoretical structure of security, and explain final target of it as shown in

Figure 4.

Since the main purpose of this paper is to explain how the random cipher based on the KCQ principle differs from the conventional Shannon random cipher, we first summarize Shannon’s concept in the section II, which is based on information theory, and explain a generalized Shannon random cipher in this context as a conceptual model in the section III. Then, we list the theoretical structure and performance of quantum stream ciphers such as Type-I , Type-II, and Type-III as concrete implementation of the conceptual model in the subsequent sections. In such models, we show that there exists quantum stream cipher which is not broken even if the secret key is stolen after communications.

2. Review of Shannon-Massey Theory of Cryptography

2.1. Historical View

It is well known that Shannon published in BSTJ in 1949 his attempt to apply the entropy-based information theory to clarify a fundamental concept of cryptography. Many well-known researchers have explained its purpose [

2,

5,

6], and the authors have nothing to add. However, in view of the development of cryptology after Shannon, it is worthwhile to explain the position of Shannon’s cryptology once again based on Massey’s concept [

2].

Today’s practical cryptography has moved away from Shannon’s information-theoretic viewpoint to mathematical cryptography based on computer science, which has developed into the fundamental technology of the modern information society. One of the reasons for this is that the modern information infrastructure, of which the Internet is the main form of communication, is extremely large and cannot be handled only by Shannon’s cryptosystem. Mathematical cryptography based on computer science can handle large-scale systems and is absolutely indispensable for the ever-expanding communication infrastructure.

On the other hand, in recent years, ultrahigh-speed backbone communication networks have become necessary as communication infrastructure to support huge systems represented by cloud computing, and thanks to the efforts of optical communication researchers, optical backbone communication lines are reaching the point of completion to support huge cloud computing systems. Against this backdrop, an environment has emerged in which information-theoretic cryptography can play an active role as a security technology for backbone communication networks.

Taking this opportunity, we believe it is worthwhile to analyze Shannon-Massey scheme of cryptology again from various point of views. In the following sections, we describe our attempt.

2.2. Conventional Definition of Information Theoretics Security for Symmetric Key Cipher

First, let us set a cipher mechanism to be considered. When a plaintext sequence is

X and a secret key is

K, the ciphertext is given by

where

is a encryption function. The secret key includes running key sequence from PRNG with a short initial key or a true long random sequence.

We begin by stating a basic assumption of Shannon theory. In Shannon theory, when one constructs a cryptographic mechanism, there is an assumption that a ciphertext

is set by the legitimate sender and it can be correctly received by both legitimate receiver and eavesdropper. Namely,

where

and

are ciphertext sequences that can be received by legitimate receiver and eavesdropper. Under this precondition, both the legitimate one and the eavesdropper can decrypt the correct ciphertext with the correct key sequence based on a secret key and PRNG. Such a mechanism can be expressed using the entropy theory developed by Shannon as follows:

Thus the security of Shannon’s cryptology is defined as follows:

:

An eavesdropper who does not know the secret key cannot decrypt the ciphertext

with probability 1. This is equivalent to

This cryptosystem is said to be information-theoretically secure against a ciphertext-only attack (COA).

On the other hand, the following theorem holds for cryptosystems with the conditions of Equation (

2) [

2,

5,

6].

:

When ciphertext consists of plaintext and key sequence, the ambiguity of the plaintext has the following limitations.

This theorem is called the Shannon limit. In the following, we explain specific features of Shannon’s cipher under the conditions of Equation (

2).

2.2.1. Non-Randam Cipher

Prepare a key sequence K to encrypt a plaintext sequence X. Assume that the ciphertext is composed of these two sequences. In this case, a non-random cipher is defined as follows:

:

A cryptosystem whose constructed ciphertext satisfies the following properties is called a non-random cipher:

A typical example of this type of cipher is an additive stream cipher. Let

and

be a plaintext and a key sequence, respectively. Then the ciphertext is as follows.

Here, Shannon gives the following definition of full confidentiality for the above cryptographic mechanism.

:

A cryptosystem is fully confidential (or perfect security in the sense of entropy) if it satisfies the following properties

Based on this definition, the conditions for achieving perfect security in the sense of entropy are as follows

:

For a cipher system to be perfect security in the sense of entropy for any plaintext statistics, the key sequence length must be equal to or greater than the plaintext sequence length, i.e,

where the key sequence must be a sequence of true random numbers.

A cryptographic mechanism that meets the above conditions is called the 0ne Time Pad (or Vernum cipher). It is inefficient and leaves excesses in key management and known plaintext attacks [

7,

8]

2.2.2. Shannon Random Cipher

In Shannon theory, we can consider an information-theoretically secure cipher even if it does not satisfy the full confidentiality condition. It is called a random cipher and is defined as follows:

:

When a cryptosystem constructed under the conditions of Equations (2), (3) and (5) has the following properties

it is called random cipher in the sense of Shannon.

In the case of ciphertext only attack, a cryptosystem with these properties can be realized by adopting a private randomization mechanism originating from Gauss, and its information-theoretic security is evaluated by the Unicity distance theory. Its concrete stracture is shown below [

2,

5,

6].

2.3. Unicity Distance Theory

2.3.1. Summary

Shannon and his successors have discussed cases where Theorem 2 does not hold but the encription cannot be uniquely decrypted by a ciphertext only attack. To simplify the discussion, we take a stream cipher encrypted by a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) with a short secret key. In order to evaluate the degree of information-theoretic security of such a cipher system, the following unicity distance is defined.

:

Let

be a sequences of ciphertexts for an eavesdropper and

be the minimum number of ciphertexts for which the ambiguity to the secret key is zero. Then it is called unicity distance of a ciphertext only attack. That is,

Here we assume that the statistical structure of the plaintext is known and the entropy per symbol is

, and the entropy of the key sequence is

. Then, the number of key-plaintext pairs per each ciphertext is given by

Since

in the above equation is equivalent to zero key ambiguity, the unicity distance is as follows [

5,

6]

The above equation shows that the unicity distance depends on the statistical structure of the plaintext.

2.3.2. Shannon Random Cipher and Its Unicity Distance

Homophonic substitution is an example of a method to increase the entropy per symbol of plaintext, independent of the key sequence. When this method is introduced, the ciphertext is not uniquely determined by the key-plaintext pair. In this case, Equation (

10) holds. Therefore, this cipher system is a random cipher. In such a random cipher, the larger the entropy of the plaintext, the more difficult it becomes to estimate the key from the ciphertext. In other words, the unicity distance becomes larger. If

, the unicity distance becomes infinite, and the key cannot be uniquely determined even from an infinite number of ciphertexts. This is called an ideal cipher. However, if the eavesdropper obtains the correct key after obtaining the ciphertext, the correct plaintext can be decrypted since

as a precondition. Thus, the Shannon limit holds.

2.4. Known Plaintext Attack against Conventional Cipher

As introduced in the previous section, the cryptography theory of Shannon and his successors ends with a formulation for a ciphertext only attack. In this section, we explain how Shannon’s theory holds when we assume a known plaintext attack (for simplicity, we assume an additive stream cipher).

:

Let

be the ciphertexts of length

n of the eavesdropper, and assume that plaintexts of the same length are known. The minimum number of ciphertexts for which the ambiguity with respect to the key is zero is defined as follows.

The

in the above equation is called the unicity distance of known plaintext attacks.

In the following, we show some properties of the unicity distance for non-ranndom cipher and random cipher in the Shanon theory.

2.4.1. Non-Random Cipher

Since

in a non-random cipher, the following is hold if a ciphertext of length equal to the key length and the corresponding plaintext are known.

where

are the ciphertext equal to the key length and the corresponding known plaintext, respectively. From the above,

This means that non-random ciphers can be decrypted in principle. Thus, the conventional symmetric key cryptography has only the above degree of information-theoretic security, and the rest relies on computational security.

2.4.2. Random Cipher

For a random cipher in Shannon theory, one has

under the condition

. From the theory of entropy, the following holds in general.

Assuming equality in the Shannon limit

, there exists a finite

n, namely

, for which

from the above formula. Therefore, even if

is infinite, a random cipher can be formally deciphered by a known-plaintext attack. From the above, it is expected that conventional random ciphers are not very effective against known-plaintext attacks because they depend on plaintexts, and if the structure of the plaintext is known, the randomization has little effect.

Thus, the conventional cryptographic techniques can provide information-theoretic security against a ciphertext only attack, but these cannot provide information-theoretic security against known-plaintext attack.

3. Conceptual Generalized Random Cipher and Its Fundamental Properties

3.1. Conceptual Mechanism

Even with a cryptographic mechanism that uses a short secret key and PRNG, it is still possible to resist ciphertext only attacks to a practical extent. In order to realize a cryptosystem with information-theoretic security for general attacks, it is necessary to develop a random cipher that goes beyond the existing concept of random ciphers. In this section, we provide an overview on a generalization of Shannon random cipher as conceptual mechanism.

Here we define a generalized Shannon random cipher as a cryptosystem such that the ciphertext of the cryptosystem is hidden by ideal noise, and it has the following features.

where

and

are the ciphertexts of the legitimate communicator,

is the ciphertext received by the eavesdropper. In other words, this is achieved by creating a situation where the ciphertext received by the legitimate receiver and the ciphertext that can be received by the eavesdropper are different. If we describe this in a sequence, it is as follows:

where

denote errors due to true noise. If this situation could be realized, then the following conceptual relations would be held.

Such a random cipher is a completely different form of random cipher than the conventional Shannon random cipher. Why this is possible is explained in a later section.

3.2. Generalized Unicity Distance

First, if the ciphertext received by a legitimate receiver and the ciphertext that can be received by an eavesdropper are different, the following situation is possible in the practical sense.

In other words, the legitimate receiver can obtain the correct plaintext with the correct key, but because the ciphertext of the eavesdropper has errors, the possibility appears such that the correct plaintext is not obtained even with the correct key. We need a generalization of the unicity distance to evaluate a security of system in such cases. The unicity distances for such a cryptographic mechanism are described below [3,9,10].

3.2.1. Ciphertext Only Attack

The unicity distance of a ciphertext only attack is described for the eavesdropper’s ciphertext as follows:

:

Let

be the minimum length of the ciphertext that has zero key ambiguity for the eavesdropper’s ciphertext. Then it is given by

is called the unicity distance of ciphertext only attack for generalized random cipher.

Unlike the conventional type, the above equation does not depend on the statistical structure of the plaintext, but on the randomness of the ciphertext that can be obtained by the eavesdropper. The error sequence in Equation (

20) should be completely random numbers or its equivalent.

To achieve this, it is convenient to use the quantum noise effects of light. As an example, if the signal system consists of non-orthogonal quantum states when the eavesdropper receives the signal, the theory is that an ideal random number error effect will appear in the received signal. This is due to quantum irregularities (Born effect) when quantum superpositions are collapsed by measurement. The detailed discussions will be given in the susequent sections.

3.2.2. Known Plaintext Attack

The conventional random ciphers can achieve a large unicity distance for a ciphertext-only attack, but the technology to achieve this is very complicated. Furthermore, it is difficult to guarantee information-theoretic security more than a key length in the known plaintext attack.

Here, we consider a known-plaintext attack on generalized random cipher. First, the information-theoretic security evaluation for the known-plaintext attack is given as follows.

:

The unicity distance of known plaintext attacks for generalized random cipher is defined as follows:

In the case of generalized random cipher, since it does not depend on the structure of the plaintext, the known plaintexts do not have much effect on the unicity distance. In other words, the following can be expected.

Later sections will discuss specific examples of this.

3.2.3. Secret Key Leakage Attack in COA

In conventional symmetric-key cipher, an eavesdropper can retain the correct ciphertext, and if she can obtain the secret key after the communication, the correct plaintext can be obtained. It is due to

. However, in generalized random cipher, a possibility of Equation (

24) arises because the eavesdropper’s ciphertext will be inaccurate. Therefore, we can define the following evaluation function [

3,

9,

10].

:

When the secret key(initial key for PRNG) is stolen after communication, minimum length of ciphertext needed by the eavesdropper to obtain the correct plaintext is as follows:

The above is called the unicity distance of the secret key leakage attack.

4. Concrete Evaluation Method of Generalized Shannon Random Cipher

In the above section, we defined several unicity distances for several attacks. The main purpose of a generalized Shannon random cipher is to improve a security against known plaintext attack (KPA). In order to perform a quantitative evaluation of security, it is necessary to develop a method for its calculation. We discuss a method in the following.

In the case of KPA for the conventional cipher, an evesdropper can obtain a correct running key sequence which corresponds to the output sequence from the PRNG.

The purpose of the eavesdropper is to estimate the secret key of PRNG from the running key sequence. Assume that a PRNG consists of a linear shift register (LFSR) with a secret key (e.g., 256 bits) and a nonlinear filter. In general, one can adopt information theoretic analysis to an immunity evaluation in the conventional stream ciphers. The technique is called a fast correlation attack.

The efficiency of key estimation is evaluated by considering the following model. Suppose that the LFSR output is regarded as a linear code word of

and the nonlinear filter section is modeled as a noisy communication channel with an error rate of

which depends on the structure of the nonlinear part. So the model corresponds to the decoding problem for linear code word of the length

n and informatin bit

K. The feature of this method is that the computational security of the nonlinear filter section is analyzed by an information-theoretic model. Such a theory was developed by Siegenthaler [

11], Chepyzhov-Smeets [

12], and others, from which the following theorem was derived [

11].

:

When the length

n of the code word, which corresponds to the length of output sequence obtained by eavesdropper, is satisfied as follow:

Then, the probability of a key being correct is greater than

if the total search complexity of the decryption algorithm is

where

is the maximum mutual information of the communication channel model with error

.

Although this body of theory analyzes computational problems in the context of information theory, it was pointed out by Yuen et al. that these theories are rather appropriate for the ITS analysis of generalized random cipher [

13,

14]. Here we apply this theory to a detailed characterization of generalized random cipher.

The generalized random cipher consists of a PRNG with short key and real noise for randomization of ciphertext or runnning key sequences. The nonlinear filter part of the running key sequence of generalized random cipher does not make sense from an information-theoretic point of view. Therefore, the model is replaced as follows.

A sequence of LFSR with initial key is channel input, and this sequence is perturbed by a true noise and channel model by nonlinear part. But the main issue is a perturbation by real noise. Then, the procedure of the eavesdropper is decoding theory for a code word (LFSR) based on the sequence with errors due to the true noise.

Conventional theories that use communication channel models for computational problems lose the rigor of applying code theory because the noise model is not an independent process, but in generalized random cipher, noise is a true independent process, so the above idea is more valid. From the above, the aforementioned theorem can be read into the problem of information-theoretic cryptography.

As a result, if we consider the meaning of the unicity distance, we can set up the following relation.

is the maximum mutual information of the measurement channel where the eavesdropper receives the running key sequence. is the error probability due to a true noise.

5. Structure of Standard Quantum Stream Cipher

The challenge is how to show that the conceptually presented generalized random ciphers are real. The Y-00 protocol was proposed to solve this problem. Y-00 protocol is a technique that combines cryptographically secure pseudo-random numbers and quantum noise effects, and is characterized by the fact that it can be equivalently regarded as a function to hide the ciphertext of mathematical ciphers with quantum noise. In this section, we show a simple explanation of the original scheme of quantum stream cipher based on Y-00 protocol [

13,

14] which is called basic quantum stream cipher or standard quantum stream cipher.

In order to guarantee ultrahigh speed and long-distance transmission, it is necessary to adopt optical signals with high energy, not single photon or entanglement light. However, in general, high power signals have little quantum effect and it does not adequately hide the ciphertext. Therefore, we introduce a mechanism in which the receiver of Bob (the legitimate receiver) can ignore the quantum effect such as quantum noise and receiver of Eve (the eavesdropper) cannot avoide the quantum effect, even though the light is strong. This scheme is called “Advantage creation by secret key". It is designed as follows:

(a) Let us consider two optical signals with quantum coherent state sending 0 and 1 data. Let us denote the two coherent state signals as follows:

and

with

which is an amplitude of laser light. A pair of two coherent states is called the communication basis

for transmitting a “Binary Signal Data"as a plaintext where

. It means to prepare a set

M of different pair

of two coherent states with different complex amplitude as follows:

The selection can be realized by a unitary transformation controlled by the running key. In the standard quantum stream cipher, the data information

are assigned regularly to one of signal of each basis. Thus, in general there is a correlation between plaintext and running key as the conventional cipher.

(b) Alice and Bob share the same PRNG with the same secret key (for example 256 bits) as the conventional stream cipher. A sequence is generated by the output of PRNG. This is called “running key" sequence in a stream cipher. Alice`s transmitter selects a communication basis in Equation (

32) following the running key of

M values, and then one of binary data is transmitted by using the selected communication basis. Thus, a sequence of

-ary optical signal with coherent state of diferent amplitude or phase is transmitted. It is a quantum ciphertext that must be converted into an electrical signal by quantum measurement for cryptanalysis.

(c) Alice and Bob share the same running key, so Bob can know which basis was selected. That is, he can receive the optical signal as the binary signal after an inverse unitary transformation. So the quantum signals for Bob are as follows:

This is independent of the communication basis.

But Eve has no information on the running key, because she does not know the secret key for PRNG. So Eve has to use a receiver for

valued signals, and has to discriminate

-ary phase shift keying (PSK) signals. In the case of phase shift keying, the set of quantum states is described by

where

m is controlled by binary data and

M-ary running key. Thus the eroor performance of Bob is given by binary quantum detection, and the error performance of Eve is formulated by

-ary quantum detection for cryptanalysis.

(d) Y-00 protocol requires a signal constellation such that the binary detection is error free, but the

-ary signal detection sufferes quantum noise effect based on Helstrom-Holevo-Yuen principle [

15,

16,

17]. That is, a non-orthogolal quantum state signal cannot be discriminated without error. The above structures satisfy this condition, because a binary detection of two coherent states is regarded as nealy orthogonal for

, but

-ary detection for complex amplitude

is regarded as non-orthognal quantum state system. The concrete signal constellation based on phase shift keying (PSK) was given in [

13].

(e) Consequently, Bob can obtain directly a data bit sequence without serious error. However, Eve can only obtain a multi-level signal sequence which corresponds to ciphertext as the measurement result of quantum ciphertext. This electrical sequence of the ciphertext has error. So Eve has to recover data sequence or secret key of PRNG from this sequence with error.

Thus a quantum stream cipher based on Y-00 protocol is a candidate of generalized random cipher in which Eve cannot obtain correct ciphertext. Moreover, this scheme has technical advantages in the real world applications. That is, the noise for randamization is only generated in the measurement process, and it does not disturbe the bandwidth of channel or data speed of the legitimate communicator. Thus it is applicable to the conventional optical communication systems for ultrafast data transmission.

6. Quantum Communication Theory for Cryptanalysis

6.1. Fundamental Formulae

The quantum communication theory was formulated by pioneers such as Helstrom, Holevo, Yuen, and its whole formulation was integrated by Holevo [

18]. Especially, Holevo [

16] and Yuen [

17] clarified optimum conditions of the quantum Bayes detection rule for multi-level signals independently, and Hirota-Ikehara foumulated quantum minimax detection rule with admissibility and completeness [

19] that corresponds to quantum version of Wald-Middleton decision theory [

20].

Let us describe the formulation of quantum detection theory of the core of quantum Shannon theory. When

-ary coherent state signal is received at each slot, the optimizing variable of the quantum measurement channel is described by a compact set of the positive operator valued measure (POVM):

,

. Then these operations are interpreated as the projector acting on the quantum state of each slot, and these provide error or detection probabilities as follows:

The appearance of quantum effects in reception process of signals is characterized by the above foumula. The quantum Bayes rule is formulated as follows:

where a priori probability is

for the admissibility in the decision theory. The necessary and sufficient condition are given as follows [

16,

17]:

:

On the other hand, the quantum minimax rule is formulated as follows [

19]:

The necessary and sufficient condition are given as follows [

19]:

:

In general, it is very difficult to find the solutions of the above two quantum detection rules. However, in the standard quantum stream cipher system, quantum state signals have a property of the covariant as defined below.

:

Let

G be a group with an operation ∘. The set of quantum state signals is called group covarinat if there exist unitary operators

such that

It characterizes quantum states

.

The general properties of quantum Bayes rule for covariant case of multi parameters are given by Ban [

21]. One of the results for coherent state signals is as follows:

If the signal set

is a covariant, the optimum POVM is given by using Gram operator

H as follows:

and the optimum quantum Bayes solution is

where

is the base state.

The error probability for Eve for

covariant signals can be given as follows [

15,

22,

23]:

where

. In addition, Osaki showed that the worst priori probability in the quantum minimax rule for the covariant signals becomes the uniform distribution and the minimax solution is also given by Equation (

41) and Equation (

42) [

24].

6.2. Advantage Creation by Differenciation of Quantum Detection Performance by Secret Key

Bob can control the unitary transformation to convert back to binary optical signals by using a running key from a pseudo-random number for the

optical signals. Then, the quantum detection model becomes the binary quantum states of

:Equation (

33) independent of the communication basis. The average error probability is given by Helstrom formula as follows [

15]:

On the other hand, “in order for Eve to perform the cryptanalysis", she has to obtain the information of running key sequence by her quantum measurement to

-ary quantum ciphertext. The first step in the procedure leading to an attack is to receive a signal flowing through the real communication channel. The average minimum error probability for the adopted quantum state signal scheme (or equivalently maximum detection probability) can be given by the formulae: Equation (

38), Equation (

39), Equation (

41), Equation (

43). For

, it becomes

Thus these formulae provide the theoretical accuracy of the ciphertext that the eavesdropper can obtain.

If Eve were to attempt to decode the binary data directly, she would adopt the binary quantum optimal measurement for the following mixed quantum states.

This structure of mixed state is called doubly symmetric mixed state, and Kato gives the quantum Bayes(also minimax) solution for such as mixed states of coherent state [

25]. Then the average error probability for binary data is given as follows:

The difference between Equation (

44) vs Equation (

45) and Equation (

44) vs Equation (

47) is called the advantage creation by a secret key.

6.3. Physical Processes for Cryptanalysis against PRNG

A sequence of length

n of quantum ciphertext from a transmitter of standard quantum stream cipher is described as follows:

is binary data (plaintext),

is running key of

M values from PRNG. Let us denote the physical attack process for cryptanalysis in the following.

6.3.1. Individual Quantum Measurement-Collective Procedure

Let us assume that Eve adopts a quantum optimum mesurement

for each slot. The observed sequence coresponds to a sequence of the decision output for

valued signal at each slot. The randomness of signals is represented by Equation (

38), and its randomness automatically provides a fully independent true random noise. The target for Eve is data (binary plaintext) or secret key of PRNG, and she has to estimate them from a sequence with errors based on a security analysis like correlation attack or other attack. Such a procedure is called “

-

".

6.3.2. Collective Quantum Measurement-Collective Procedure

On the other hand, Eve can adopt a collective quantum measurement. It is a quantum measurement such that one treats some slots of a coherent state sequence of -ary as one block quantum state. Here Eve has to construct a quantum entanglement measurement system of signals, where is the length of the block. Based on such a measured sequence, she analyzes several attacks against the sequence. This scheme is called “- . When is large number, it seems that this physical implimentation is impossible. After such physical manipulations, an eavesdropper would be forced to make some cryptanalytic attempts.

7. Cryptological Attack for Quantum Stream Cipher and Its Performance

7.1. The Main Attack Scheme

Here let us describe the concept on cryptological attacks against the standard and some generalized quantum stream ciphers. Since the receiver of Bob adopts a binary detection scheme by the communication basis synchronized with the same PRNG with the same secret key, there is no mismatch in the communication basis. Then it outputs a binary signal as data without serious error, because the signal power is strong and the signal distance of two signals in a basis is large. However, Eve’s received signals are -ary and contain errors, because the signal distances between several signals are small. The extent of the error is called a noise masking region.

:

Let “ " be the number of signals masked by quantum noise in the several measurement processes.

7.1.1. Legitimate Receiver Simulation Attack

Let us consider the KPA based on the exhaustive search. This attack clarifies the difference between standard symmetric key cipher and quantum stream ciphers. In the standard quantum stream cipher based on Y-00 protocol, the data (plaintext) of the signal of each basis is deterministically set such that data 0 and 1 are regularly mapped to neighboring signals composed of a communication basis [

13]. That is, the data information is mapped to

clockwise of the phase signal in the phase space. This menas that the standard quantum stream ciphers have a correlation between basis and data,

As a result, each signal of valued signals has information for the plaintext(data) and the communication basis simultaneously. The information of the basis corresponds to that of runnning key. Therefore, if the each signal value can be determined by -ary detection, the plaintext and running key sequence information can be obtained directly.

In the above scheme, the information of binary plaintext in neighboring signals is completely masked by noises, but the information of running key of M values has finite ambiguity, because the is small. In such a situation, it is easy for Eve to memorize digital ciphertext sequence of -ary signals containing errors. Eve can try KPA based on exhaustive search for all binary decisions similar to Bob on the stored sequence. This is called a .

Here, let us denote a rough approximate analysis for intuitive understanding. If the length of known plaintext is

which corresponds to the equivalent key length and also equals the length of the ciphertext, then the probability of the correct decision for the running key

of

length is

Equation (

49) means that the following many number of key corresponds to the correct plaintext of

length in the exhaustive search.

This means

In other words, these features correspond to the property of the random cipher based on the degeneracy structure [

13]. On the other hand, if there is no error, the cipher is

The above characteristics indicate the fact that the criticism such that the standard quantum stream is the same as a conventional cipher is incorrect.

7.1.2. Fast Correlation Attack

Let us assume that no restriction is placed on the known plaintext length. At this situation, one can consider the runing key sequence (LFSR output) as a linear code and attempt a fast correlation attack on the received sequence with errors. The -valued running key sequence of the LFSR output is stored with errors. Then the -valued sequence is converted to binary values and a fast correlation attack is performed. The performance is evaluated by the unicity distance. From the definition of unicity distance, it can be evaluated by the channel capacity of Eve’s measurment channel. In general, the standard quantum stream cipher does not have sufficient performance against the fast correlation attack when the is small. The concrete example to overcome it will be shown in the subsequent section.

7.1.3. Secret Key Leakage Attack

Assume that Eve memorizes digital ciphertext sequence of -ary signals containing errors. After communication, we assume that Eve can obtain the secret key of PRNG. Eve will try an attack to estimate plaintext that uses the correct secret key to the measured sequence with errors. That is, Eve can adopt the threshold for binary decision depending on the correct runing key, and she collects the plaintext sequence. The performance against such an attack is the most important in the generalized Shannon random cipher. Unfortunately, the standard quantum stream cipher does not have immunity against this type of attack.

7.2. Role of Additional Randomization Techinique

In generalized random ciphers, the ciphertext or running key sequence obtained by an eavesdropper is perturbed by a true noise (such as quantum noise). If the noise effect is small, it naturally cannot provide sufficient information-theoretic security from the above theory. For realistic applications, it is necessary to develop techniques to reduce the channel capacity in Equation (

31). Since noise must physically appear, such a generalized random cipher can be realized only at the physical layer.

The problem to make increasing noise, as described above, has little precedent in information theory and is the exact opposite of what has been done so far. That is, the technological development is to increase the noise effect of the eavesdropper, but it does not affect the legitimate communicator. In the channel model of receiving process of an eavesdropper, a research to reduce its maximum mutual information is called “Randomization technology", and several examples have already been studied. Specific models will be presented later, but further research is expected.

8. Randomizations Towards Generalized Quantum Stream Cipher

The standard quantum stream cipher introduced in the previous section is highly practical and has affinity with real communication networks. However, it may have weaknesses in terms of the quantitative security evaluation. Randomization techniques are needed to realize a generalized quantum stream cipher with high-performance. This section presents some examples of randomisation methods and gives a rough description of improvements achieved by each method.

8.1. Overlap Selection Keying (OSK)

The OSK is a mechanism to randomize the geometrical relation between data (plaintext) and signal value of communication basis, patented by Tamagawa University (Patent number 4451085, 2003-June 27) [

26]. It is to randomize the relation between data and given basis based on a sequence from a branch of the PRNG. By this method, the correlation of geometrical relation of data and communication basis is broken inside of the region of quantm noise masking

. So we have the following performance instead of Equation (

49):

In addition, the KPA is converted to the ciphertext only attack. So the legitimate receiver simulation attack does not work. Thus, the unicity distance for KPA is guaranteed to have the following performance.

The other effect of OSK is that plaintext is automatically encrypted with pseudo-random numbers, and the plaintext itself becomes a kind of ciphertext called Y-00 plaintext.

8.2. Deliberate Signal Randomization (DSR)

Assume that a communication basis consists of a binary phase shift signal. A basis is randomly selected by the running key sequence from PRNG, and one signal for data is transmitted by the selected basis. Then

M signals are located on the upper plain of the phase space, and other

M signals are located on the lower plain of the phase space [

13]. Here phase space means a space by quadrature amplitude

and

.

Even

, the masking effect

by quantum noise in Eve’s receiver is not enough, because the quantum noise is small. To enhance the error of Eve, the signal for transmission is randomly shifted by a true noise on the upper plain when the signal belongs the upper plain, and is shifted on the lower plain when it belongs the lower plain. This scheme is called Deliberate Signal Randomization (DSR) which corresponds to “

". The strength of DSR is described by

. As a result, the masking region is enhanced by

, where

is the quantum noise effect. This was proposed by Yuen in 2003-Nov 10 [

14]. When we adopt OSK and DSR with

, we may have the ideal performance such as

Thus, this may improve the unicity distance in Equation (

54). The concrete example will be given in the subsequent section.

8.3. Quantum Noise-Diffusion Mapping

The unicity distance of the generalized random cipher may be evaluated by the channel capacity of Eve from Equation (

31). In this theory, it can be regarded such that a linear code with the initial value of LFSR as information propagates through a noisy channel. Thus, the decoding capability as the decryptobility at that time is evaluated by the channel capacity. In other words, as the length of the LFSR increases and the rate decreases, it becomes smaller than the channel capacity and the decoding accuracy increases. To obtain a large unicity distance, it is necessary to reduce the eavesdropper’s channel capacity by additional randamization like DSR. However, there is a trade-off in that it requires sacrificing the communication performance of the legitimate communicator. Therefore, a method to increase the unicity distance while keeping the amount of noise fixed is the subject of research.

Hirota-Kurosawa proposed in 2007 a method to introduce a mapping mechanism from a sequence of PRNG to actual quantum states such that the input to the noisy channel is regarded as a nonlinear code [

27]. This is achieved by re-diffusing the signal masked by a small quantum noise. This mechanism renders the fast correlation attack inoperative. In addition, it provides the immunity against algebra attacks [

28]. The detailed information-theoretic analysis of this method is still incomplete, but we look forward to further research.

8.4. Phase Masking by Symplectic Matrix

A theory for a randomization of code form of coherent states is given by Sohma [

29,

30]. It consists of the unitary operator

associated with a symplectic transformation in which any unitary operator composed of beamsplitters and phase shifters can be described by a symplectic transformation. First, let us consider a general code form of coherent state as follows:

From Stone-von Neumann theorem, the quantum characteristic function for the class of quantum Gaussian state is given as follows:

where

and where

are the canonical conjugate operators. Then

is a symplectic matrix, and it is given by

Here let us denote a vector of complex amplitudes

as follows:

then we have the following relation.

As a result, the unitary transformation for the coherent state sequence is given as follows:

Thus, by scrambling the elements of Equation (

60) with pseudo-random numbers, one can construct codes with any waveform. This technology is useful to realize a coherent PPM scheme proposed by Yuen [

14].

9. Generalized Quantum Stream Cipher of Type-I and Its Performance

A quantum stream cipher that adds randomization techniques like OSK and DSR to the standard quantum stream is called a Type-I generalized quantum stream cipher. In this section, we show the scheme and performance.

9.1. Communication Scheme

Let us describe a communication scheme for phase shift keying (PSK). A running key sequence is generated by PRNG with short secret key. The selection scheme of communication basis by the running key is the same as the standard quantum stream cipher. In addition, several randomizations described above may be installed. Then valued signals are transmitted. Bob can adopt the binary quantum optimum receiver, but in practice he can adopt an optical heterodyne receiver.

In the latter case, the output of the receiver is an analog electrical currents consisting of signal and quantum noise. For decoding, the threshold for binary decision is controlled based on the running key. Using the selected threshold, the binary decision is performed to obtain data. This type of communication scheme can be realized by the current optical communication technology.

9.2. Unicity Distance of Known Plaintext Attack

Here, let us assume a phase shift keying (PSK) quantum stream cipher with DSR and OSK. Eve is forced to adopt a detection of

-ary signals and proceeds the conventional fast correlation attack. Once the eavesdropper’s channel is set, the lower bound of the unicity distance is obtained by its channel capacity. The optimum condition of maximum mutual information for multi-valued quantum state signal is given by Holevo [

18], and the optimum POVM is given by Osaki [

31] based on a prediction of Fuchs-Peres [

32] as follows:

:

The optimum POVM for maximum mutual information is given by the quantum minimax detection operator when the signal set is covariant and linearly independent.

The numerical performance has been verified for the maximum mutual information property based on the above theorem. As a result, when

, it is possible to approximate its properties by heterodyne receiver [

31]. In fact,

means that the signal set is regarded as almost analog signal. To confirm it, we can estimate the optimality for an analog signal by the following theorem [

33].

: The estimation bound for complex amplitudes are given by following formula.

where the right logarithm derivative is defined by

And its solution is as follows:

where

is a photon annihiration operator, and it corresponds to a hetrodyne measurement.

So we can assume that the eavesdropper adopts heterodyne receiver, which is the highest performance for asynchronous quantum state signals. In this case, the eavesdropper receives

original phase signals to obtain

M valued information on the running key. The signal distance between signals is

, where

is the signal strength, and

is the masking effect of the signal by quantum noise. The amount of signal masking is

. When the strength of DSR that spreads quantum noise effect is

, we have

. Here, the range of DSR can be set as follows.

The equivalent quantum noise of the optical heterodyne measurement is

, and the maximum mutual information in the wedge approximation is [

13]

(the exact communication channel capacity will be reported separately). Then the generalized unicity distance for KPA is

This is called Nair-Yuen formula [

13]. If the strength of DSR is

, the generalized unicity distance is

This cannot be achieved using only mathematical cipher. Thus, this scheme has advantages over conventional cryptographic mechanisms in terms of information-theoretic security. Although it is not the ultimate one, this type of system is expected to play a significant role in assuring the security of real optical communication systems.

9.3. Coherent Pulse Position Modulation Method

There is a method to realize Type I quantum stream cipher without using the above randomization technique. It is called a coherent Pulse Position Modulation (CPPM). This mechanism takes information as M-ary and configures it as a transmitted signal system with M-ary PPM. The M-ary PPM signals are then spread like a pseudo-waveform signal into the M- ary slot by unitary transformations driven by pseudo-random numbers generator. We recently proposed a method for implementing this scheme using Sohma’s method (Section VIII-D). Details will be presented in another paper.

10. Generalized Quantum Stream Cipher of Type-Ii and Its Performance

In this section, we discuss a higher-security performance scheme than the Type-I system. When a secret key for the cipher is stolen after communications, the conventional cipher can be decripted correctlly. The most important feature of generalized quantum stream cipher is that the cipher may not be decrypted even the secret key is stolen. We discuss in this section “a conceptual model" to show that there exists secure communication even if the secret key is stolen.

10.1. Communication Scheme

Here we show that there exists a scheme that is resistant to the secret key leakage attack. Let us assume that a channel between Alice and Bob is low-loss.

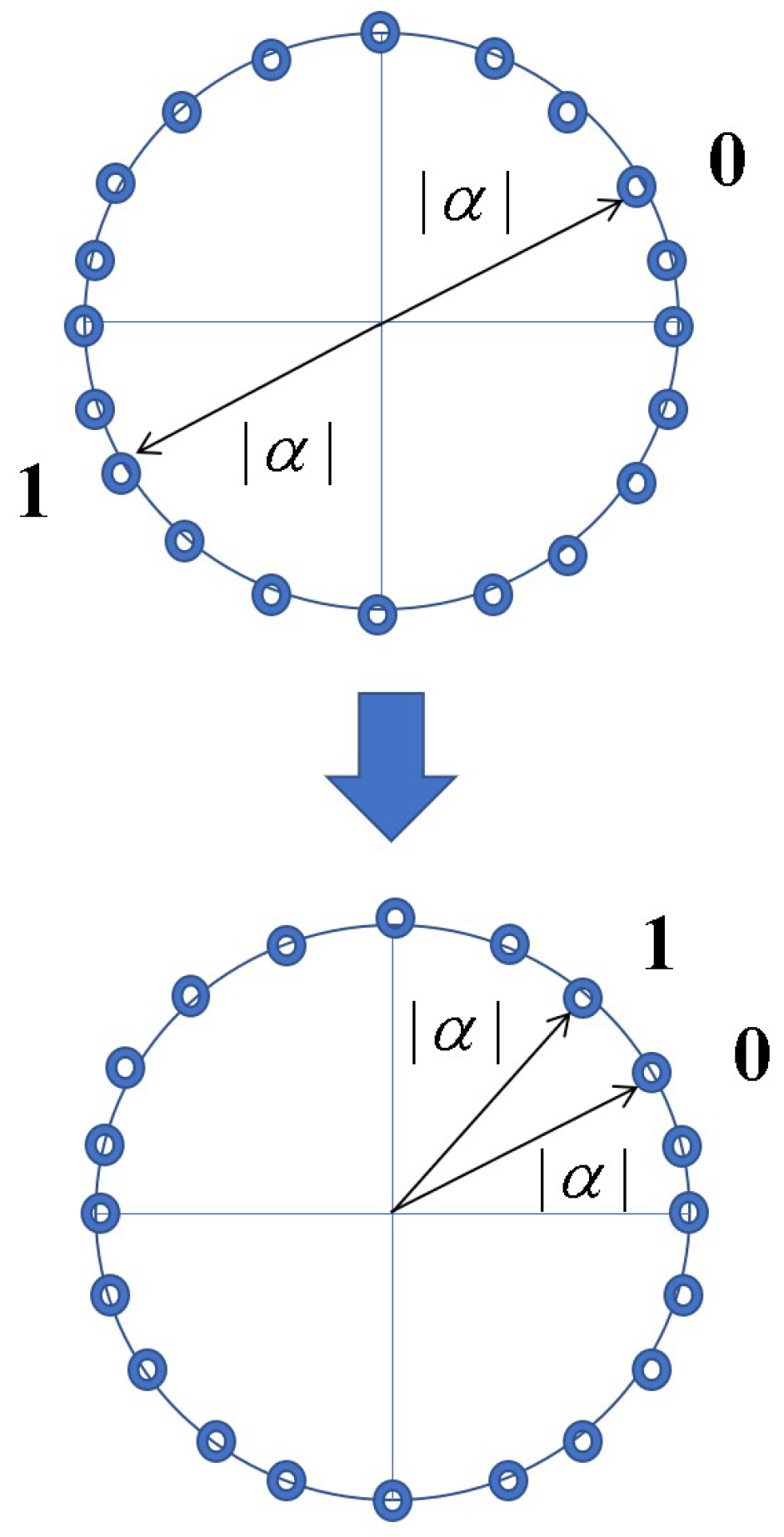

(a) Alice uses PSK (phase shift keying). The set of communication basis consists of two coherent states with small angles as follows (See

Figure 5):

where

. When

, a set of

signals becomes covariant by Equation (

40). These communication basis is selected by a running key sequence. Then plaintext is set to the selected basis as same as the type-I. Or the quantum cipher text is generated by the unitary transform

to coherent states controlled by a running key sequence.

(b) Bob has the same unitary transform , and it inversely transforms the input quantum states depending on the running key sequence. The output quantum states from the inverse unitary transformation can be regarded as binary quantum states.

(c) Bob adopts the quantum optimum receiver with Helstrom limit for these binary quantum states. The concrete system is called Dolinar receiver. The average error for the data

is independent of the basis and it is given by Equation (

44) as follows:

Design the amplitude and phase difference so that the above equation holds sufficiently small.

(d) Eve has to discriminate

valued coherent state signals. Since Eve does not know a priori probability distribution for

valued signals, she has to adopt a quantum minimax rule as follows:

where

is a set of Equation (

71).

10.2. Secret Key Leakage Attack

Here, we show that the system is resistant to the secret key leakage attack. At first, Eve has to store a sequence of -valued signals received by the above quantum minimax receiver to try the crypto analysis. Once Eve has the secret key and the correct running key sequence after the measurement, she can try a classical binary decision scheme to sequences with errors in the 2M values for each slot.

Let us show how it works. When a set of quantum states is a covariant, the solution of the minimax rule is equivalent to quantum Bayes rule with the worst a priori probability distribution:

[

24]. When

, one can aproximate the error performance based on quantum noise by analog version in the quantum decision theory. The solution becomes the heterodyne receiver. Thus, let us assume that Eve adopts heterodyne receiver with an analog to digital converter of the infinite bandwidth. She can store the almost analog signal consisted of signals and quantum Gaussian noise.

When Eve obtains the secret key and the correct running key sequence, she adopts the binary threshold decision based on classical Bayes rule depending on the running key. It corresponds to a model for the binary decision for binary signals with Gaussian quantum noise, because the uncertainty caused by pseudo-random numbers will disappear. The error probability for the binary data (plaintext) is

The relation between Bob’s error:Equation (

72) and Eve’s errors: Equation (

74) with secret key provided after communication for the plaintext (data) is as follows:

Thus, the sequences of plaintexts that Bob and Eve can obtain become as follows:

where

,

. As a result, the sequence of Eve consists of the plaintext

X and the quantum error sequence.

Here we can regard the quantum error as random key:

. The structure of Eve’s sequence of plaintext : Equation (

77) is equivalent to Shannon cipher with key sequence

. So the unicity distance of the final sequence for Eve is as follows.

where

is an entropy of quantum error sequence,

is an entropy per symbol of the plaintext.

Thus, in principle, there exists the generalized Shannon random cipher with following performance:

However, we emphasize that this is intended to provide theoretical evidence and is applicable only to channels with very low losses. Therefore, more careful research is needed for practical application.

11. Generalized Quantum Stream Cipher of Type-Iii and Its Performance

The principle of the previous schemes was to adopt a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) for diffusion of quantum noise effect. Here, we show new schemes such that the quantum ciphertext is constructed by directly mapping the plaintext regularly to the quantum state signal without an encryption mechanism by PRNG and secret key.

11.1. Communication Scheme 1

First, let us consider an encryption as a kind of game based on the strategy of Bob and Eve’s receiving mechanism. This correspoonds to a model based on only error performances between quantum Bayes rule and quantum minimax rule. The communication scheme is as follows:

(a) Plaintext consists of combination of

J bits.

Then we assume that Alice can control a priori probability distribution of M valued signals and the structure of quantum state ensemble . The structure of quantum states is opened. Unknown is only a priori probability disribution.

(b)

M-valued plaintext is mapped regularly to one of

M-valued quantum states as follows:.

For example

M-ary PSK scheme.

(c) Bob has an information for the a priori probability for

M signals and has an information of the structure of the quantum state ensemble

. Then he can adopt the quantum Bayes decision rule. His error probability is given by

Eve knows the structure of quantum state signals, but she does not know a priori probability distribution. So she adopts the quantum minimax decision rule as follows:

Then her error probability is given by the quantum Bayes with the worst a priori probability. We wish to enlarge the absolute quantity of Eve’s error performance. To do it, we can adopt a concept of covariant and noncovariant signals which are descrived as follows [

34]:

:

M-ary signals

are group cavarinat with respect to a group

of order

M if and only if the following relation is hold:

where

and ∘ is the operation of the group

G.

Minimax decision rule gives a solution assuming an a priori probability distribution that gives the maximum value of the Bayes rule solution. Here, when the signal system is not group covariant, the worst a priori probability distribution of minimax is not uniform [

24].

According to the general theory of quantum detection theory [

16,

19], we have the following relation.

That is, when the set of quantum states is not covariant, the error performances for the minimax rules themselves is greatly degraded, depending of signal properties [

24,

35,

36]. Thus we can have the following relation.

Using this property, the system uses a signal set that is not group covariant and transmits with an a priori probability distribution

that maximizes the characteristic difference between Bayes and minimax. The optimization problem is given as follows:

where

is a priori probability distribution that Alice can control, and the relation among a priori probability distributions is

.

is a structure of noncovariant states. Here, the worst a priori probability distribution

for the minimax is determined only by the structure of noncovariant quantum states.

Thus, even if the legitemate communicators do not have secret symmetric key, we can realize the quantum advantage creation. The details of this property require numerical analysis and it will be shown in the subsequent paper.

11.2. Communication Scheme 2

Let us discuss a modification of wire-tap channel scheme in the sense of quantum advantage creation principle.

11.2.1. Secret Capacity

The conventional wire-tap channel model requires a special channel such that the signal to noise ratio of Bob is greater than that of Eve as the system requirement. We replace its condition to the notion of the quantum advantage creation in quantum measurements.

According to quantum Shannon theory established by Holevo and others [

18], the capacity formula for lossy Gaussian noise channel for coherent states is given as follows [

37]:

:

The capacity formula of the quantum lossy Gaussian noise channel for coherent state signals is given as follows:

where

S and

are average photon numbers of received signal and additive noise, respectively.

The above formula is in general greater than the Shannon classical capacity. To achieve this Holevo capacity in the realization stage, Alice and Bob must have prior knowledge of the quantum signal and other various conditions. The capacity can only be achieved by adopting a quantum measurement under those conditions [

18]. Especially, the time synchronisation between Alice and Eve is necessary, but Eve cannot obtain such an information before communication. If these conditions are not known, a heterodyne receiver would be optimal. With this differentiation, it is possible to construct a modified wire-tap channel communication scheme. The secret capacity is defined as follows:

where

and

are POVM for Bob and Eve, respectively. Eve’s POVM is restricted to heterodyne when there is no synchronisation. A conjecture of the concrete formula of secret capacity for this model based on coherent state is as follows [

38,

39].

where

are the average photon number of signal and noise for Bob, and

are those for Eve. When the above formula is positive, one can implement the secure communication system in principle.

11.2.2. Coding Problem

For the practical discussions, we assume that the system is finite and discrete scheme. The problem is to construct a coding theory that creates the advantage of the legitemate communicators. It is equivalent to constract a superadditivity of mutual information (or accessible information) [

40]. The first challenge to clarify the effect of coding was made in Ref. [

41].

12. Conclusion

In this paper, we explained that generalized random cipher, which can improve the shortcomings of one time pad ciphers, can be realized by applying quantum effects. To evaluate such ciphers, we have introduced the generalized unicity distance, and showed some examples. A more detailed theoretical analysis needs to be developed for realization of the ultimate performance such as Type-II, Type-III.

On the other hand, a number of experimental studies for the standard quantum stream cipher have already been initiated on the basis of the the above theory. As a result, promising results for practical application have been obtained by groups of USA, Japan and China [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In addition, the generalized quantum stream cipher with randamizations of Type-I has been implemented by Futami group [

50]. This is the first demonstration for quantum stream cipher with sufficient information theoretic security.

Another possibility of the generalized random ciphers are Shapiro’s scheme so called quantum low probability of intercept [

51], and Lloyd’s scheme [

52]. These will be introduced in the part III.

References

- Shannon, E. Communication theory of secrecy systems. BSTJ 1949, 26, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, J. Contemporary Cryptology-An Introduction-. Edited by G.J.Simmons, IEEE Press, 1992.

- Borbosa, G.A.; Corndolf, E.; Kumar, P.; Yuen,H.P. Secure communication using coherent state. Proceedings of QCMC-2002, Edited by Shapiro.J.H, and Hirota.O, Rinton Press, 2002.

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Quantum stream cipher based on Holevo-Yuen theory. Entropy 2022, 24, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, D. Codes and Cryptography. Oxford U Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Blahut, R.E. Cryptography and Secure Communication. Cambridge University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, H. Theory of information, codes, and Cryptography. Lecture series of IEICE of Japan, Corona Pablising Co. LTD, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, H. A study of attack against Vernum cipher. Report of graduation research at Tamagawa University, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O.; Sohma, M.; Kawanishi, K. Quantum noise randamized stream cipher:Y-00. Jpn. J. Opt. 2010, 39, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Generalized unicity distance and its application to Y-00 quantum stream cipher, IEICE of Japan, Technical Report,2023 March, IT2022-128.

- Siegenthaler, T. Decrypting a class of stream ciphers using ciphertext only. IEEE Trans. Comput., 1985, C-34, 81.

- Chepyzhov, V.V.; Johansson, T.; Smeets, B. A simple algorithm for fast correlation attacks on stream cipher. FSE 2000, LNCS 1978, 2001, 2001, p181. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, R.; Yuen, H.P.; Corndolf, E.; Kumar, P. Quantum noise randomized ciphers. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 052309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen,H.P. Key Generation: Foundations and a New Quantum Approach. IEEE. J. Selected topics in Quantum Electronics, 209, 15, 1630–1645. Yuen, H.P. KCQ : Keyed communication in quantum noise. arXiv 2003, arXiv:0311061.

- Helstrom, C.W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory", Academic Press, 1976.

- Holevo, A.S. Statistical decision theory for quantum systems. J. Multivar. Anal. 1973, 3, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Kennedy, R.S.; Lax, M. Optimum testing of multiple hypotheses in quantum detection theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1975, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S. Quantum systems, channels, information. De Gruyter 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O.; Ikehara, S. Minimax strategy in the quantum detection theory and its application to optical communications. Trans. IEICE Jpn. 1982, 65E, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, D. An introduction to statistical communication theory. McGRAW-HILL, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Momose, R.; Hirota, O. Quantum measurements for discrimination among symmetric quantum states and parameter estimation. International Theoretical Physics, 1997, 36, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Usuda, T.S.; Hirota, O. Group covariant detection for a three phase shift keyed signal. Physics Letters A, 1998, 245, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Osaki, M.; Hirota, O. Quantum detection and mutual information for QAM and PSK signals. IEEE Transactions on communications, 1999, 47, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Ban, M.; Hirota, O. Derivation and physical interpretation of the optimum detection operators For coherent state signals. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 54, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Hirota, O. Square Root Measurement for Quantum Symmetric Mixed State Signals. IEEE, Trans. on Information Theory 2003, 49, 3312–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O.; Kato, K. Japan Patent Number 4451085, 2003,June.

- Hirota, O.; Kurosawa, K. Immunity against correlation attack on quantum stream cipher by Yuen 2000 protocol. Quantum Inf. Process. 2007, 6, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Practical security analysis of quantum stream cipher by Yuen protocol. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 032307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Coherent Pulse Position Modulation Quantum Cipher Supported by Secret Key. Bulletin of Quantum ICT Research Institute, Tamagawa University 2011, 1, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Masking property of quantum random cipher with phase mask encryption. Quantum Info. Process. 2014, 13, 2221–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Ban, M.; Hirota, O. The maximum mutual information without coding for binary quantum state signals. Journal of Modern Optics 1998, 45, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.A.; Peres, A. Quantum-state disturbance versus information gain: Uncertainty relations for quantum information. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 53, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Lax, M. Multiple-parameter quantum estimation and measurement of non-self adjoint observables. IEEE Trans. on Inform Theory, -19.

- Usuda, T.; Takumi, i. Group covariant signals in quantum information theory. Proc. of Quantum Commun. and Measurement 2, Ed by Kumar.P,D’Ariano.Hirota.O, Prenum Press (Kluwer/Plenum), 2000.

- Nakahira, K. Minimum error probability of asymmetric 3PSK coherent state signal. Private communication 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O. Towards Quantum Enigma Cipher -A protocol for G bit/sec encryption based on discrimination property of non-orthogonal quantum states. Bulletin of Quantum ICT Research Institute,Tamagawa University 2015, 5–10.

- Holevo, A.S.; Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Capacity of quantum Gaussian channels. Phys. Rev. 1820; A-59, 1820. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O.; Iwakoshi, T.; Sohma, M.; Futami, F. Quantum stream cipher beyond the Shannon limit of symmetric cipher and the possibility of experimental demonstration. Proceedings of SPIE on Quantum communication and quantum imaging 2010, 7815. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O. Importance and Applications of Infinite Dimensional Non-Orthogonal Quantum State. J Laser Opt Photonics 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Kato, K.; Izutsu, M.; Hirota, O. Quantum channels showing superadditivity in classical capacity. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. A foundation of quantum channels with super additiveness for Shannon information. Applicable Algebra in Eng. Communication and Computing 2000, 10, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbosa, G.A.; Corndorf, E.; Kumar, P.; Yuen, H.P. Secure communication using mesoscopic coherent states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 227901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, G.S.; Reillly, D.; Smith, N. Practical physical layer encryption: The marriage of optical noise with traditional cryptography. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2009, 47, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O.; Sohma, M.; Fuse, M.; Kato, K. Quantum stream cipher by Yuen 2000 protocol: Design and experiment by intensity modulation scheme. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 022335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, M.; Yosida, M.; Hirooka, T.; Kasai, K. QAM quantum stream cipher using digital coherent optical transmission", Opt. Express 2014, 22, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futami, F.; Guan, K.; Gripp, J.; Kato, K.; Tanizawa, K.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Winzer, P.J. Y-00 quantum stream cipher overlay in a coherent 256-Gbit/s polarization multiplexed 16-QAM WDM. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 33338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizawa, K.; Futami, F. Ultra-long-haul digital coherent PSK Y-00 quantum stream cipher transmission system. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 10451–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Song, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Huang, L.; Cheng, M.; Liu, D.; Deng, L. Secure 100 Gb/s IMDD Transmission Over 100 km SSMF Enabled by Quantum Noise Stream Cipher and Sparse RLS-Volterra Equalizer. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 63585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, L.; Zhong, Y.Q.; Deng, L.; Liu, D.; Dai, X.; Gao, X.; Cheng, M. Device-compatible ultra-high-order quantum noise stream cipher based on delta-sigma modulator and optical chaos. Nature, communication engineering 2024, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futami, F.; Tanizawa, K.; Kato, K. Transmission of Y-00 Quantum Noise Stream Cipher with Quantum Deliberate Signal Randomization over Field-Installed Fiber. Bulletin of Quantum ICT Research Institute,Tamagawa University 2023, 23–25. https://www.tamagawa.jp/research/quantum/bulletin/pdf/Tamagawa.Vol.12-3.pdf.

- Shapiro, J.H.; Boroson, D.N.; Dixon, P.B.; Green, M.E.; Hamilton, S.A. Quantum low probability of intercept. JOSA-B Optical Physics 2019, 36, B41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Hayden, P.; Krovi, H.L.; Lloyd, S.; Shapiro, J.H. Quantum enigma machines and the locking capacity of a quantum channel. Phys.Rev 2014, X-4011016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).