Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Bělohlávek J, Dytrych V, Linhart A Pulmonary embolism, part I: Epidemiology, risk factors and risk stratification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2013, 18, 139198.

- Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, Arcelus JI, Bergqvist D, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2007, 98, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendelboe AM, Raskob GE Global Burden of Thrombosis: Epidemiologic Aspects. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 1340–1347. [CrossRef]

- Keller K, Hobohm L, Ebner M, Kresoja KP, Münzel T, et al. Trends in thrombolytic treatment and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism in Germany. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, Buller H, Gallus A, et al. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014, 34, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson FAJ, Spencer FA Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation 2003, 107, I9–I16.

- Wolf SJ, McCubbin TR, Feldhaus KM, Faragher JP, Adcock DM Prospective validation of Wells Criteria in the evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann. Emer Med. 2004, 44, 503–510. [CrossRef]

- Miniati M, Prediletto R, Formichi B, CMarini C, Ricco GD, et al. Accuracy of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999, 159, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty S Pulmonary embolism: An update. Aust Fam Physician. 2017, 46, 816–820.

- Pollack CV, Schreiber D, Goldhaber SZ, Slattery D, Fanikos J, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol.. 2011, 57, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens PMG, Lucassen WAM, Geersing GJ, van Weert HCPM, Kuijs- Augustijn M, et al. Alternative diagnoses in patients in whom the GP considered the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Fam Pract. 2014, 31, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard L Acute pulmonary embolism. Clin Med (Lond). 2019, 19, 243–247.

- Elliott CG, Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, DeRosa M Chest radiographs in acute pulmonary embolism. Results from the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry. Chest. 2000, 118, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ceia F, Fonseca C, Mota T, Morais H, Fernando Matiaset F, et al. Prevalence of chronic heart failure in Southwestern Europe: the EPICA study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002, 4, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosterd A, Hoes AW Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 2007, 93, 1137–1146. [CrossRef]

- Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Cilloniz C, Martin-Loeches I, Garcia-Vidal C, San Jos A,Torres A Microbial Etiology of Pneumonia: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Resistance Patterns. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17, 2120. [CrossRef]

- Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, et al. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. 2016, 21, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raherison C,Girodet P-O Epidemiology of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2009, 18, 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Van Es, Kraaijpoel N, Klok FA, Huisman MV, Exter PLD, et al. The original and simplified Wells rules and age-adjusted D-dimer testing to rule out pulmonary embolism: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2017, 15, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers CEA, Hulle TVD, Gal HL, Kyrle PA, Huisman MV,et al. Towards a tailored diagnostic standard for future diagnostic studies in pulmonary embolism: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2017, 15, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlieg AVH, Middeldorp S Hormone therapies and venous thromboembolism: where are we now? J. Thromb Haemost. 2011, 9, 257–266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Molina A, Rota LL, Micco PD, Brenner B, Trujillo-Santos J, et al. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy, postpartum or during contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2010, 103, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgmehr R, Pishgahi M, Mohaghegh P, Bayat M, Khodadadi P, et al. Relationship between Thrombosis Risk Factors, Clinical Symptoms, and Laboratory Findings with Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis; a Cross-Sectional Study. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019, 7, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Streiff MB, Agnelli G, Connors JM, Crowther M, Eichinger S, et al. Guidance for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016, 41, 32–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells PS, Ginsberg JS, Anderson DR, Kearon C, Gent M, Turpie AG, et al. Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 129, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H Diagnosis of acute Pulmonary Embolism. Hamostaseologie. 2018, 38, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinides S, Meyer G Management of acute pulmonary embolism 2019: what is new in the updated European guidelines? Intern Emerg Med. 2020, 15, 957–966. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Bueno H, Geersing GJ, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Respir J. 2019, 54, 1901647. [Google Scholar]

- Patel H, Sun H, Hussain AN, Vakde T Advances in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: A literature review. Diagnostics. 2020, 10, 1–19.

- Zarabi S, Chan TM, Mercuri M, Kearon C, Turcotte M, et al. Physician choices in pulmonary embolism testing. CMAJ 2021, 193, E38–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, Richman PB, Courtney DM Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004, 2, 1247–1255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund Y, Cachanado M, Aubry A, Orsini C, Raynal PA, et al. Effect of the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria on Subsequent Thromboembolic Events Among Low-Risk Emergency Department Patients: The PROPER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018, 319, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freun Y, Rousseau A, Guyot-Rousseau F, Claessens YE, Hugli O, et al. PERC rule to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in emergency low-risk patients: Study protocol for the PROPER randomized controlled study. Trials. 2015, 16, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dandan O, Hassan A, Alnasr A, Al Gadeeb M, AbuAlola H, et al. The use of clinical decision rules for pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: a retrospective study. Int J Emerg Med. 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlicki J, Penaloza A, Germeau B, Moumneh T, Philippon AL, et al. Safety of the Combination of PERC and YEARS Rules in Patients With Low Clinical Probability of Pulmonary Embolism: A Retrospective Analysis of Two Large European Cohorts. Acad Emerg Med. 2019, 26, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard T, Lombrozo T, Nichols S Bayesian Occam’s Razor Is a Razor of the People. Cogn Sci. 2018, 42, 1345–1359. [CrossRef]

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019, 200, e45–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker AD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Wedzicha JA, Calverley PMA, Albert RK, Anzueto A, Criner GJ, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2017, 49, 160791. [Google Scholar]

- Klok FA, Zidane M, Djurabi RK, Nijkeuter M, Huisman MV The physician’s estimation ‘alternative diagnosis is less likely than pulmonary embolism’ in the Wells rule is dependent on the presence of other required items. Thromb haemost. 2008, 99, 244–245. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo D-J, Zhao C, Zou YD, Huang HH, Hu JM, et al. Values of the Wells and revised Geneva scores combined with D-dimer in diagnosing elderly pulmonary embolism patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015, 128, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penaloza A, Soulié C, Moumneh T, Delmez Q, Ghuysen A, et al. Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule in European patients with low implicit clinical probability (PERCEPIC): a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet Haematol 2017, 4, e615–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydoğdu M, Sinanoğlu NT, N Doğan NO, I Oğuzülgen IK, Demircan A, et al. Wells score and Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria in preventing over investigation of pulmonary embolism in emergency departments. Tuberk Toraks. 2014, 62, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Posadas-Martínez ML, Vázquez FJ, Giunta DH, Waisman GD,Quirós FGBD, et al. Performance of the Wells score in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism during hospitalization: a delayed-type cross sectional study in a community hospital. Thromb Res. 2014, 133, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical Symptoms of Deep Vein Thrombosis | 3 |

| Other Diagnoses Less Likely Than PET | 3 |

| Heart rate greater than 100 bpm | 1.5 |

| Immobilization or surgery within the last 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Deep vein thrombosis or previous pulmonary thromboembolism |

1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| PE: Pulmonary thromboembolism; bpm: Beats per minute | |

| Characteristics |

|---|

| - Under 50 years of age |

| - Pulse < 100 lpm (in tachycardia) |

| - Absence of hypoxia (SatO2 > 95%) |

| - No history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis |

| - No trauma or recent surgery |

| - Absence of hemoptysis |

| - Does not use estrogen therapy |

| - Absence of swelling in the legs |

| PERC: Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria; SatO2: Oxygensaturation; bpm: Beats per minute |

| Pneumonia | Presence of fever. Radiological pattern compatible with respiratory infection and dyspnea or cough. |

|---|---|

| Exacerbation/suspicion of COPD | History of smoking. dyspnea and cough |

| Heart failure | Presence of radiological pattern compatible with heart failure and dyspnea or orthopnea |

| Anticoagulation in non-cancer patients | Previous anticoagulation in non- cancer patients |

| PERC | Those patients who meet the PERC criteria mentioned in Table 2 |

|

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; PERC: Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria | |

| Variable | Total | Risk According to the Wells Scale | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=399 | Low | Intermediaten=150 | High | ||

| n=210 | n=39 | ||||

| Age, years (SD) | 65±16 | 65±16 | 65±16 | 64±16 | 0.731 |

| Women, % | 214 (53.60%) | 118 (56.20%) | 79 (52.70%) | 17 (43.60%) | 0.334 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Patients without comorbidities, % | 46 (11.50%) | 27 (12.90%) | 14 (9.30%) | 5 (12.80%) | 0.567 |

| Smoking, % | 137 (34.30%) | 83 (39.50%) | 49 (32.70%) | 5 (12.80%) | 0.005 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 55 (13.79%) | 34 (16.20%) | 17 (11.30%) | 4 (10.30%) | 0.335 |

| COPD, % | 48 (12.00%) | 34 (16.20%) | 14 (9.30%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.007 |

| Renal insufficiency, % | 17 (4.30%) | 9 (4.30%) | 8 (5.30%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.34 |

| Oncological Pathology, % | 121 (30.30%) | 48 (22.90%) | 56 (37.30%) | 17 (43.60%) | 0.002 |

| Summa of comorbidities, SD | 0.885 ± 0.32 | 0.871 ± 0.34 | 0.907 ± 0.29 | 0.872 ± 0.34 | 0.569 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Disnea, % | 269 (67.40%) | 133 (63.30%) | 108 (72.00%) | 28 (71.80%) | 0.186 |

| Hemoptisis, % | 11 (2.80%) | 5 (2.40%) | 5 (3.30%) | 1 (2.60%) | 0.86 |

| Pleuritic pain, % | 154 (38.60%) | 84 (40.00%) | 57 (38.00%) | 13 (33.30%) | 0.721 |

| Lower limb pain, % | 43 (10.80%) | 5 (2.40%) | 18 (12.00%) | 20 (51.30%) | <0.001 |

| Cough, % | 115 (28.80%) | 76 (36.20%) | 33 (22.00%) | 6 (15.40%) | 0.002 |

| Faint, % | 15 (3.80%) | 5 (2.40%) | 8 (5.30%) | 2 (5.10%) | 0.316 |

| Fever, % | 66 (16.50%) | 39 (18.60%) | 23 (15.30%) | 4 (10.30%) | 0.386 |

| Ortopnea, % | 25 (6.30%) | 12 (5.70%) | 11 (7.30%) | 2 (5.10%) | 0.784 |

| Vital Signs | |||||

| Taquicardia > 100 lpm, % | 105 (26.30%) | 36 (17.10%) | 55 (36.70%) | 14 (35.90%) | <0.001 |

| SBP < 90 mmHg, % | 21 (5.30%) | 9 (4.30%) | 8 (5.30%) | 4 (10.30%) | 0.308 |

| Saturation < 94%, % | 185 (46.40%) | 95 (45.20%) | 71 (47.30%) | 19 (48.70%) | 0.882 |

| Variables with high a priori negative predictive value for PE | |||||

| PERC, % | 13 (3.30%) | 11 (5.20%) | 2 (1.30%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.058 |

| Pneumonia, % | 27 (6.80%) | 18 (8.60%) | 9 (6.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.132 |

| COPD flare-up, % | 40 (10.00%) | 26 (12.40%) | 13 (8.70%) | 1 (2.60%) | 0.135 |

| Heart failure, % | 18 (4.50%) | 11 (5.20%) | 5 (3.30%) | 2 (5.10%) | 0.679 |

| Non-oncology patients on anticoagulation,% | 29 (7.30%) | 18 (8.60%) | 11 (7.30%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.166 |

| CT angiography result | |||||

| Pulmonary thromboembolism, % | 139 (34.80%) | 6 (2.90%) | 95 (63.30%) | 38 (97.40%) | <0.001 |

| Patients with CT angiography performed in the Emergency Department, % | 324 (81.20%) | 166 (79.00%) | 121 (80.70%) | 37 (94.40%) | 0.066 |

| COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; bpm: Beats per minute; PERC: Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria; PE: pulmonary embolism; CT angiography: Computed Tomography Angiography; SD: standard deviation. | |||||

| Variable | PE | Not PE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 66 ± 17 | 64 ± 16 | 0.821 |

| Women, % | 65 (46.80%) | 149 (57.30%) | 0.44 |

| Positive CT CT angiography in the Emergency Department, % | 124 (89.20%) | 200 (76.9%) | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Patients without comorbidities, % | 16 (11.50%) | 30 (11.50%) | 0.993 |

| Smoking, % | 31 (22.30%) | 106 (40.80%) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 16 (11.50%) | 39 (15.00%) | 0.335 |

| COPD, % | 9 (6.50%) | 39 (15.00%) | 0.013 |

| Renal insufficiency, % | 3 (2.20%) | 14 (5.40%) | 0.128 |

| Oncological Pathology, % | 45 (32.40%) | 76 (29.20%) | 0.515 |

| Summary of comorbidities (SD) | 0.885 ± 0.320 | 0.885 ± 0.320 | 0.993 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Disnea, % | 101 (72.70%) | 168 (64.60%) | 0.102 |

| Hemoptisis, % | 4 (2.90%) | 7 (2.70%) | 0.914 |

| Pleuritic pain, % | 60 (43.20%) | 94 (36.20%) | 0.17 |

| Lower limb pain, % | 31 (22.30%) | 12 (4.60%) | <0.001 |

| Cough, % | 21 (15.10%) | 94 (36.20%) | <0.001 |

| Faint, % | 6 (4.30%) | 9 (3.50 %) | 0.674 |

| Fever, % | 17 (12.20 %) | 49 (18.80%) | 0.09 |

| Ortopnea, % | 6 (4.30%) | 19 (7.30%) | 0.24 |

| Vital Signs | |||

| Taquicardia > 100 lpm, % | 46 (33.10%) | 59 (22.70 %) | 0.025 |

| SBP < 90 mmHg, % | 8 (5.80%) | 13 (5.00%) | 0.747 |

| SatO2 < 94%, % | 79 (56.80%) | 106 (40.80%) | 0.002 |

| Wells Scale | |||

| Low Risk, % | 6 (4.30%) | 204 (78.50%) | <0.001 |

| Moderate Risk, % | 95 (68.30%) | 55 (21.20%) | |

| High Risk, % | 38 (27.30%) | 1 (0.40%) | |

| Variables with high a priori negative predictive value for PE | |||

| PERC, % | 0 (0.00%) | 13 (5.00%) | 0.007 |

| Pneumonia, % | 5 (3.60%) | 22 (8.50%) | 0.065 |

| COPD flare-up, % | 6 (4.30%) | 34 (13.00%) | 0.006 |

| Heart failure, % | 7 (5.00%) | 11 (4.20%) | 0.712 |

| Non-oncology patients on anticoagulation, % | 5 (3.60%) | 24 (9.20%) | 0.039 |

| COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; SatO2: Oxygen saturation; bpm: Beats per minute; PERC: Pulmonary Embolism Rule Out Criteria; PE: pulmonary embolism; CT angiography: Computed Tomography Angiography; SD: standard deviation. | |||

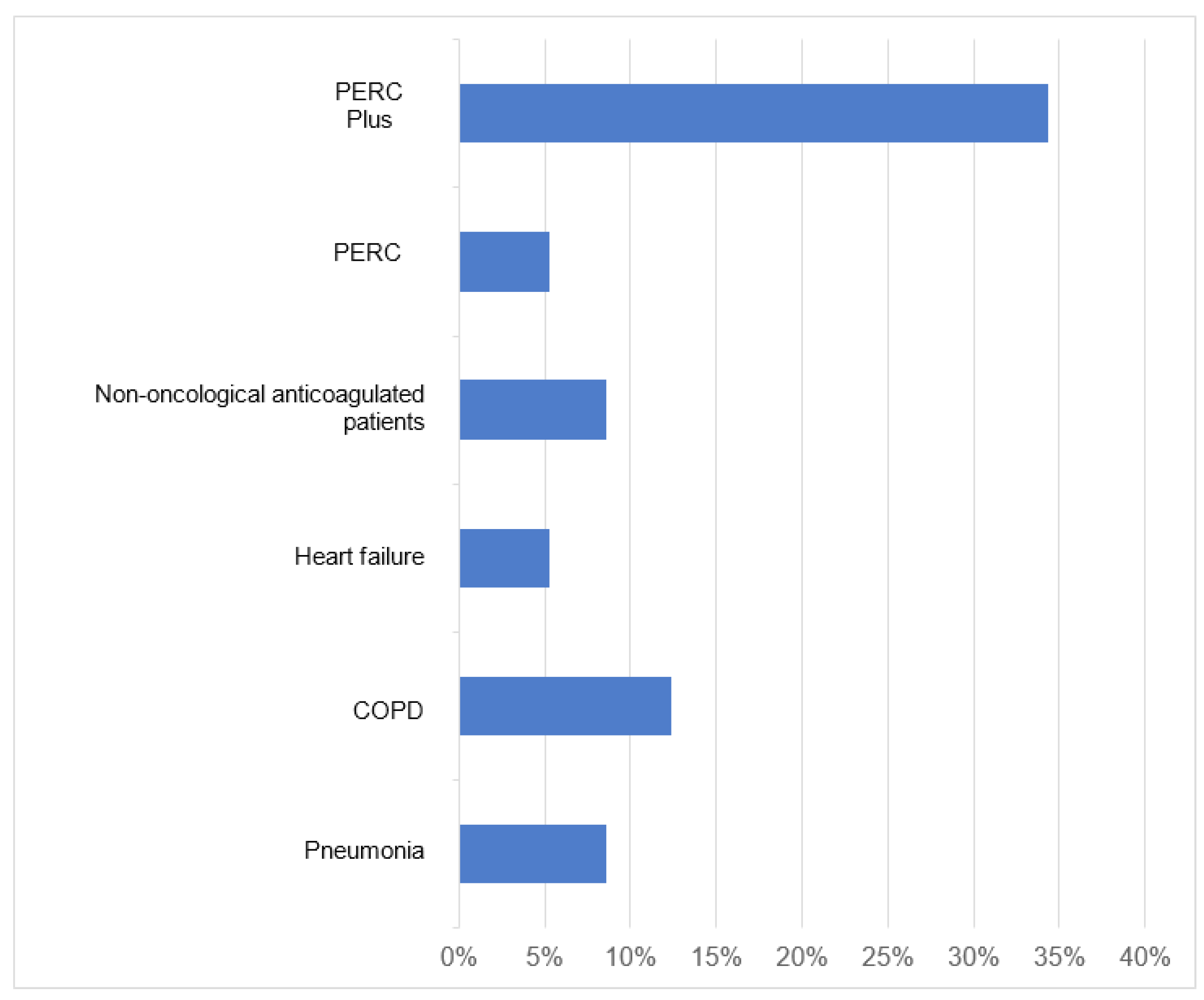

| Risk | Sensitivity | Specificity | VPP | VPN | % CT Angiography Reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | Low | 100.00% | 8.82% | 3.13% | 100.00% | 8.57% |

| Middle | 94.74% | 7.27% | 63.83% | 44.44% | 2.67% | |

| High | 100.00% | 0.00% | 97.44% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| COPD | Low | 100.00% | 12.75%% | 3.26% | 100.00% | 12.38% |

| Middle | 94.74% | 14.55% | 65.69% | 61.54% | 5.33% | |

| High | 97.37% | 0.00% | 97.37% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Heart failure | Low | 100.00% | 5.40% | 3.02% | 100.00% | 5.24% |

| Middle | 94.74% | 0.00% | 62.07% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| High | 94.74% | 0.00% | 97.30% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Non-oncologicalanticoagulatedpatients | Low | 100.00% | 8.82% | 3.13% | 100.00% | 8.57% |

| Middle | 94.74% | 10.90% | 64.75% | 54.55% | 4.00% | |

| High | 100.00% | 0.00% | 97.44% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| PERC | Low | 100.00% | 5.39% | 3.02% | 100.00% | 5.24% |

| Middle | 100.00% | 3.64% | 64.19% | 100.00% | 1.33% | |

| High | 100.00% | 0.00% | 97.44% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| PERC plus | Low | 100.00% | 34.31% | 4.29% | 100.00% | 34.30% |

| Middle | 83.16% | 25.45% | 65.83% | 46.67% | 25.50% | |

| High | 92.11% | 0.00% | 97.22% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PERC: Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value; CT angiography: Computed Tomography Angiography | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).