1. Introduction

Higgins and colleagues have drawn on a growing body of research to contend that “Persons with disabilities remain largely invisible or forgotten in their uprooted communities.” [

1,

2] In turn, Pisani and Grech have encouraged engaging with disability and forced migration to catalyze critical dialogue and fresh thinking across disciplines:

Fields such as disability studies need to urgently engage with migration, to not only inform other areas, but also to challenge its own eurocentrism, and to broaden its epistemological horizons. The same applies to migration studies, looking at transit, at change, at bodies that move and cross borders. [

3] (p.437)

We propose an analytical framework that includes people with diverse physical and intellectual disabilities. This approach suggests the utility of integrating critical disability and trauma approaches to inform the study of the experiences of disabled refugees. Disability studies, with its emancipatory agenda, has long been driven by the social model that argues that such conditions arise from societally imposed barriers that reflect, and are rooted in, oppression and discrimination. By focusing attention on the issues created by structural settings and cultural norms, the social model argues that encouraging disabled people’s expressions of agency can only be achieved by challenging and changing those forces and values [

4,

5,

6]. Critics of this conceptualization have argued that it denies the agency of disabled people by reifying their status as victims [

7,

8].

As one possible way to address this conundrum and advance the development of theorization, we propose a view of disability as a relational process that lies at the interface of oppressive structures and individual and collective agency. We suggest that this conception can lead analysts to a deeper understanding of disabled refugee experiences and realities. The lodestone contention underpinning this perspective is that disabled individuals possess agency and that they can and do act to challenge oppressive structures and practices. Offering them relevant knowledge and support to act encourages them to express their innate agency, thus facilitating engagement in their communities. On the other hand, understanding how trauma affects disabled refugees and their social interactions while also recognizing their capacity for resilience avoids depicting them as a group as passive victims. Emphasizing the trauma story and the negative stereotyping of refugees can profoundly influence their sense of self and ultimately their resilience [

9]. In this respect, it appears to make practical and policy sense persistently to encourage this group’s members to remain conscious of, and to exercise, their agency as they confront trauma, displacement and continuing vulnerability.

Our proposed analytical frame encompasses physical and intellectual disabilities alike. The latter is characterized by limitations in adaptive behavior that may affect everyday social and practical skills, and intellectual functioning that include reasoning, learning and problem-solving [

10]. Although statutes sometimes limit the legal capacity of intellectually disabled people due to mandated guardianship arrangements, the framework we suggest follows Catala’s proposition and highlights their agency, understood as an interactive process between individuals’ capacity to express themselves and environmental factors [

10]. While intellectual disability is typically described on a spectrum ranging from mild to severe, people with profound intellectual disability can still qualify as epistemic agents who may express practical, affective and embodied knowledge [

10]. Moreover, they can be political agents, cultivating legitimacy and participation in the political arena [

11]; social agents who need support to build such connections and relationships [

12] and causal agents who make things happen in their lives [

13].

It is important to clarify the terminology in use here as there are tensions among approaches to disability language in relevant scholarship, advocacy and practice [

14]. Moreover, analysts often offer prescriptive guidance concerning specific disability terminology. For example, while the “people-first” terms, as in “people with disabilities,” remain in widespread use, many disability scholars prefer “identity-first” language as in “disabled person” [

14] to denote the disabling and oppressive tendencies of modern society [

5,

15] or more accurately to represent the process of embodiment, which involves recognizing how power structures, society and culture shape bodily experiences [

7]. This usage also emphasizes that disability is a social construct that intersects with individual lived experiences, technologies and adaptive strategies rather than simply marking a defect [

7,

16]. We have adopted the latter terminology to highlight disabled refugees’ embodied capacity to exercise agency and resilience [

17].

We have organized this article into four parts. We first briefly discuss the emancipatory aims of disability studies scholarship and outline the limitations of the social model in recognizing the innate agency of disabled individuals. Second, we draw on trauma-informed scholarship to capture the broader contextual factors that contribute to the distress experienced by disabled refugees while also emphasizing their potential for growth and development. Third, we sketch an analytical construct that integrates critical disability theory and a trauma-informed framework to point up the vital role of the sense of self, agency and resilience expressed by disabled refugees in their daily lives. We conclude by highlighting the article’s contribution and suggest directions for future research.

2. Disability Theory and Disability Studies

Disability studies scholarship has sought to contribute to the emancipation of individuals with a range of disability conditions. To further this agenda, its developers have based their analyses on a social model, which views disability as arising from societal barriers, leading to oppression and discrimination [

4,

5,

6,

18,

19]. Thomas, for example, has suggested that the social model is revelatory and liberatory because it recognizes that most of the difficulties that disabled people experience in housing, education, employment, transport, cultural and leisure activities, health and welfare services, among others, are socially rooted [

6]. As Oliver has contended, the previously regnant “medical” model individualized disability issues and thus left social, political and economic structures unaffected [

15]. That conception was followed by the implementation of medical social control, in which physicians (and other health professionals) were seen as information providers, gatekeepers and institutional agents who could help secure access to relevant medical support and technologies. Advocates of the social model have made a lasting contribution to disability studies by contesting the pervasive medical frame and offering fresh insights into the implications of living with disability [

5,

19].

However, critics of this approach have nonetheless argued that equating disability with social oppression and exclusion largely ignores individuals’ agency while contending that changes in this population’s circumstances could only occur via structural shifts that lay beyond their reach to effect [

7,

8,

20]. Shildrick has likewise questioned the social model for its assumption of a “pre-given subject waiting to be empowered” [

7] (p.38). She has instead underscored the richness of a sociopolitical approach that recognizes the autonomy and agency of disabled people rather than treating them as passive targets of action by others. Moreover, she has observed that learning from feminism, “disability studies also needs to ask whether demands for recognition within the existing system—as though the problem were no more than one of material exclusion—is an adequate response.” [

7] (p.38)

Barnes has responded to critics of the social model but in doing so did not clearly address the question of agency:

First, a social model perspective is not a denial of the importance or value of appropriate individually based interventions, be they medically, re/habilitative, educational or employment-based. Instead, it draws attention to their limitations in terms of furthering disabled people’s empowerment. Second, the social model is a deliberate attempt to shift attention away from the functional limitations of individuals with impairments onto the problems caused by disabling environments, barriers and cultures. In short, the social model of disability is a tool with which to provide insights into the disabling tendencies of modern society in order to generate policies and practices to facilitate their eradication. For advocates, impairment may be a human constant but “disability” need not and should not be. [

5] (p.20)

Another point of criticism of the social model is the binary it imposes on impairment/disability thinking [

21] and disabled/nondisabled people [

7,

20,

21]. Mercer has explained that proponents of the social model have commonly avoided incorporating the experiences of disabled people into their approach since doing so would require grappling with the intersection of often unique individual impairments and interests [

22]. Moreover, as Thomas has claimed, a focus on the biological character of impairments could endanger the policy gains attained by social model advocates, resulting in a reaffirmation of the “impairment causes disability” position that has long underpinned the medical model of disability [

6]. However, removal of the impaired body from the social model may itself result in validating the medical disability discourse: “The social model—in spite of its critique of the medical model—actually concedes the body to medicine and understands impairment in terms of medical discourse.” [

16] (p.92) Impairment is as much social as it is biological and any framework should encompass the study of both disability and impairment [

6,

16,

23].

Because the social model disassociates impairment from disability, it leaves open the possibility that even in a perfect world in which disabled persons have full rights and participate in society, disability might be viewed simply as a personal tragedy [

21]. In this sense, the social identity of nondisabled individuals is deeply embedded with the personal tragic perspective of impairment and disability. What is more, not only do nondisabled individuals frequently view disability as a tragedy, that perspective is also often extended, by assumption, to a view that disabled people wish to be other than they are, although that outlook implies a rejection of identity and self on the part of disabled individuals [

21]. Challenging the tragic view and affirming positive identity is therefore both personal and collective in character, which augments the social model’s understanding: “The social model sites ‘the problem’ within society: the affirmative model directly challenges the notion that ‘the problem’ lies within the individual or impairment.” [

21] (p.578)

Swain and French have also argued that sustaining the disabled/nondisabled divide based on impairment and oppression, the cornerstones of the social model, by itself does not address the “tragic” view of disability and does nothing to support the realization of positive identities among those with disabilities [

21]. Although many nondisabled people have impairments, these cannot be equated with disability. Also, nondisabled people may also be oppressed based on poverty, racism, sexism and sexual preference, as indeed are many disabled people; and oppressed individuals themselves can act as oppressors in some circumstances [

21]. Moreover, as Mitchell and Snyder have observed, the concept of disability in the social model is inherently discriminating: “… a foundational concept of disability as prevalent, transhistorical, cross-cultural and not bound to observe the foundational borders of social identity such as race, class, gender or sexuality, produces an arbitrary experience of body difference as stigmatizing.” [

20] (p.53) To address this criticism, Barnes has suggested that the impairment/disability divide in the social model was a pragmatic choice and he has also acknowledged that certain impairments restrict an individual’s capacity for autonomous functioning [

5]. Certainly, the social model’s adherents do not dispute the fact that medical and therapeutic treatment is often required and appropriate for different health conditions [

24].

Advocating for the critical disability studies frame, Shildrick has proposed deconstructing the binary designations among individuals sustained by the social model to offer maximum encouragement to disabled individuals to exercise their agency [

7]. Moreover, she has suggested that disability should be understood to be context-specific: “what qualifies as a disability in any case varies greatly according to the sociohistorical and geopolitical context.” [

7] (p.35) If so, it follows that disabled/nondisabled designations are provisional and do not constitute fixed identities [

7]. Shildrick has contended that critical disability studies scholars have developed this argument to “unsettle entrenched ways of thinking on both sides of the putative divide between disabled and nondisabled, and to offer an analysis of how and why certain definitions are constructed and maintained.” [

7] (p.38) Alternatively, Garland-Thomson has framed the work of critical disability studies as an effort to view disability as a “civil and human rights issue, a minority identity, a sociological formation, a historic community, a diversity group, and a category of critical analysis in culture and the arts.” [

18] (p.12)

In summary, the prevailing frame at the core of disability studies today assumes that most challenges faced by disabled people in different contexts have social origins. However, in equating disability with pervasive oppression and material exclusion, this conception has ignored disabled people’s agency. Moreover, the conceptual divisions within the social model have led to static identities for disabled people, thereby further stigmatizing them. Critical disability studies, as proposed by Shildrick and Garland-Thomson, has emerged to contest the social model and to serve as an alternative conceptualization of disability.

3. Refugees and Trauma

Exposure to traumatic experiences due to forced migration often has a significant effect on refugees’ mental health. However, not all refugees are traumatized, and the mental health experiences of displaced populations are far more complex than either-or trauma-related discourses suggest [

25,

26]. Additionally, some scholars have problematized the term “refugee” due to its association with the trauma that may arise from forced migration [

27,

28]. Defining refugees as helpless, dependent and socially isolated victims can overshadow the fact that they are actors in their life stories who have often shown themselves to be remarkably resilient as individuals and as groups alike [

26].

Recent research has pointed up tensions in the definitions of trauma offered by different actors, e.g., legal and medical professionals, humanitarian organizations and refugees themselves. Further, trauma narratives evidence a hierarchy that places the knowledge of one group above others [

26]. The medicalized narrative of trauma, expressed in the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), replete with its clinical checklists and protocols, for example, enjoys pride of place in such discussions and is accorded superior political power, a fact that has had far-reaching economic and social consequences for refugees [

26,

29]. While some researchers recognize the potential benefits of a PTSD diagnosis for refugees because it may permit them access to psychological interventions, validate their suffering and garner appropriate legal and political support, frequent narrow use of the diagnosis fails to address the extensive and protracted aftereffects of trauma and displacement that many refugees confront [

30].

In addition, the medicalization of trauma fixates on very difficult past events while blinding analysts to the ongoing post-migration context that can be equally harrowing for refugees. A 2015 multi-agency study conducted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) network found that past traumatic events may not be the only or even the most important source of psychological distress for refugees [

31]. The entire migration journey and asylum-seeking process as well as post-migration factors (e.g., unemployment, precarious living conditions, insufficient language proficiency, social discrimination and difficulties with integration) can all cause sustained and painful stress. Because the multiple stressors experienced by refugees daily are continuous and interconnected, Theisen-Womersley has questioned the possibility of separating them into neat categories of pre-migration, migration and post-migration [

26]. Rather, individual migrant experiences appear to be more circular than linear in character, and however useful it may be to map the factors affecting refugee mental health, such static representations of their lived realities may not encourage the population to express its individual and collective agency. Accordingly, she has suggested a sociocultural understanding of trauma, in which that phenomenon is understood as “an intersubjective, temporal, dynamic process shaped by culture, among other factors.” [

26] (p.14) Similarly, studies by other scholars have conceived resilience as an interpersonal, communal process that includes the broader social context [

9,

32].

Such an understanding of trauma as both an individual and social phenomenon allows for distinguishing between personal and collective traumatization, which has implications for scholarly understanding of the character of the experience, its multiple impacts and transmission among individuals similarly affected as well as the development of strategies aimed at promoting healing and recovery from its many effects [

26]. In turn, recognizing trauma as a process marked by intensity, long duration and interdependency among social, cultural and psychological dimensions allows for a dynamic and contextualized understanding of resilience as it may occur in different forms, i.e., what counts as resilience for one group may not register similarly for another [

33]. Indeed, the simultaneous experience of resilience and vulnerability challenges the assumptions underpinning the “traumatized refugee” narrative. Refugee experiences of potentially traumatic events are embedded in intricate networks of personal and collective meaning-making processes in which resilience and vulnerability interact [

34]. As such, refugees should be understood as agents capable of, and willing to seek, change by navigating and negotiating resources in culturally meaningful ways. In so doing, they may develop new or renewed psychological resources [

26].

In summary, avoiding reducing refugee experiences to psychiatric diagnoses and recognizing the broader social, political, cultural and economic factors that contribute to their distress across the migration cycle emphasizes their potential for growth and development and innate capacity to make meaning of their experiences and to hope for the future [

26]. This recognition should include encouraging such individuals to exercise their agency as they confront contexts of continuing displacement, trauma and vulnerability [

34].

4. An Integrated Framework Incorporating Critical Disability and Trauma-Informed Frames

Disability can result from the experience of first, becoming, and thereafter, living as a refugee. The dangers associated with armed conflicts and persecution increase the risks of injury and enduring impairment for those affected by them. Such situations can obstruct access to education, rehabilitation or other support and create an impetus for those with disabilities to flee, even when others without such conditions may elect to remain. The risk of acquiring a disability in such scenarios is also heightened since legal and social protections are typically sharply diminished even as financial and physical security is threatened [

35].

Overall, concepts of disability and of trauma have developed amid multiple tensions among a diversity of narratives, dominated foremost by the medical paradigm. Rooted in social, cultural, political and economic structures, these discourses have each had practical implications for disabled refugees. As noted above, the discourse on disability that framed it as “a medical problem needing a medical solution” [

18] (p.11), has been challenged by scholars propounding a social model. However, by excluding the impaired body, that frame risks validating the medical discourse instead [

16]. Moreover, by equating disability with oppression, the social model largely ignored disabled individuals’ agency since positive evolution in their life conditions could only arise from structural changes that they could play no part in attaining. That is, despite its emancipatory aims, this view again presented disabled people as victims, albeit this time because of society rather than as a result of their impairments [

8].

By bringing the impaired body back into the analytic frame, critical disability theory has helped to conceptualize an “embodied” agency of disabled refugees. The psychological impact of refugees’ identity erosion due to forced migration particularly, places them in a situation in which they need essentially to imagine a new sense of self [

36]. Understanding resilience as “bouncing back” to their “original” state or persona is simply not appropriate in this reality. Their physical and psychological relationship with adversity implies instead ongoing efforts to mobilize internal and external resources to “bounce forward,” i.e., choosing new possibilities in their current life circumstances [

17].

Many analysts have argued that agency is important to the realization of resilience. In addition, although no consensus exists on defining or measuring resilience, many scholars agree that a narrow focus on a structural ability to access critical assets does not convincingly describe the phenomenon [

37]. Posch and colleagues have argued for considering resilience as an evolving relational process rather than a property, in which individual and collective resilience stems from the dynamic exercise of people’s agency [

37]. Outside support can encourage and facilitate disabled refugees’ agential expression and therefore enhance resilience—individuals’ ability and willingness to address the structural conditions that affect their capacity to act. In this view, resilience can be conceptualized in terms of refugees’ “adaptive capacities, the ability for reorganization and renewal, and the potential for self-organization and learning” [

38] (p.8).

This conception of agency and resilience allows scholars to view trauma and disability as dynamic and contextual while avoiding assigning “fixed” identities to disabled refugees and rejecting a simplified “traumatized refugee” narrative. Mirza and Hammel have called for recognition and support of heterogeneous disability experiences and diverse community participation paths enacted in individually, contextually and culturally preferred ways [

39]. However, emphasizing the agency of disabled refugees to adapt in a post-migration context also risks some leaders and citizens declaring that because some of them can respond, the entire group should be expected to do so and to do so alone. Such reasoning risks undermining disabled refugee efforts even as it may permit those unsympathetic to their situations, for whatever reasons, to blame them wrongly for their perceived inaction.

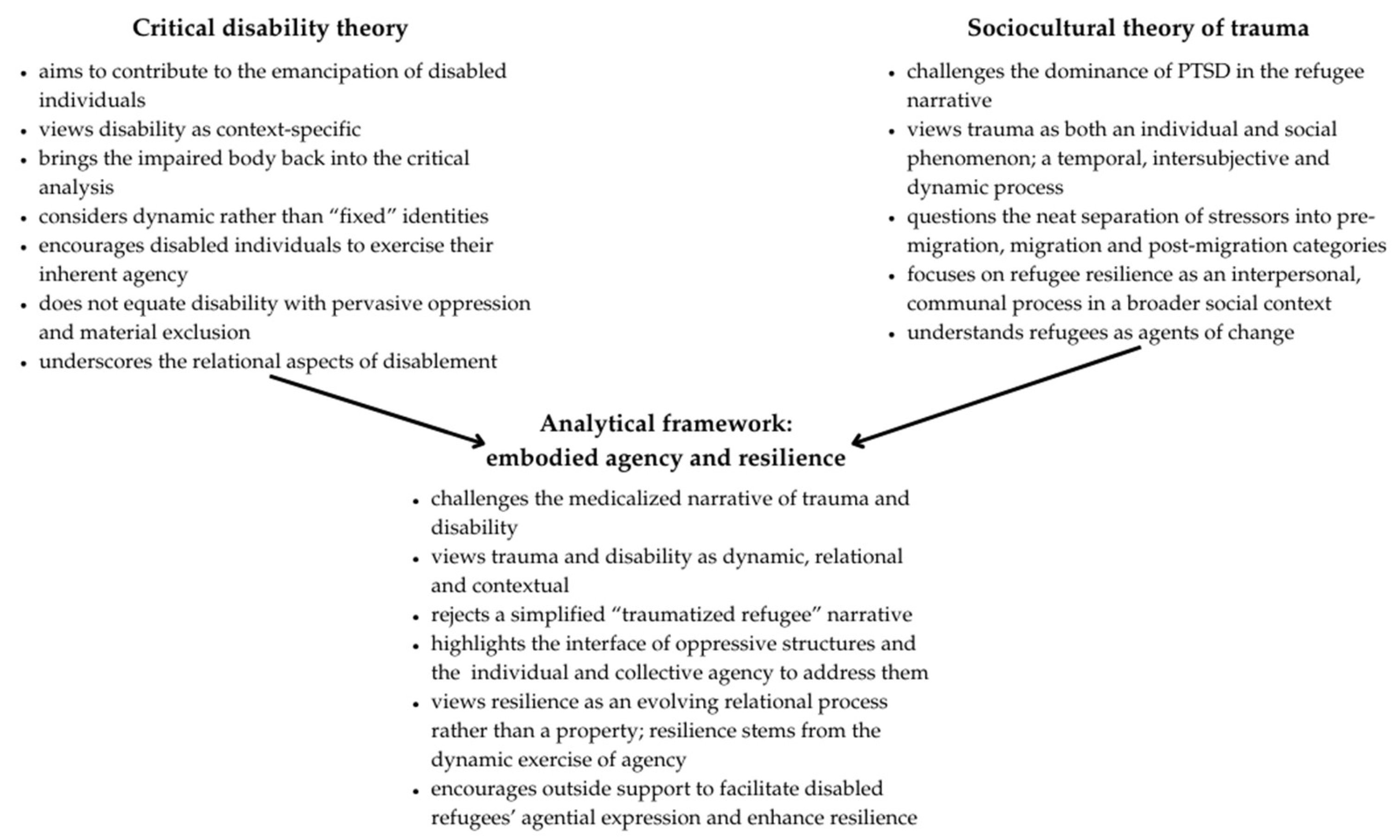

Figure 1 illustrates that integrating central elements of a trauma framework with those drawn from critical disability theory yields a more comprehensive accounting of the individual and shared experiences of disabled refugees. While the trauma framework and critical disability theory are often considered and critiqued separately, when drawn together in this way, they forcefully challenge the medicalized narrative of refugee trauma and disability. Moreover, their integration acknowledges the importance to disabled refugees of specialized treatment as well as of broader social conditions for their lived experiences. Instead of focusing solely on individual or structural dimensions, this conceptualization highlights the significance of the interface of oppressive structures and forces

and the potential of acts of individual and collective agency in efforts to address them. This approach encourages analysts to consider not only how disabled refugees respond to oppressive social structures and the effect of those on their sense of self, agency and efficacy, but also on what elements in society can be mobilized to assist them in their efforts to redress those factors. This retheorization affords disabled refugees a space to assess and work to obtain relevant knowledge and support from others and each other as they express their innate agency in the communities in which they now reside.

5. Conclusions

This brief article has outlined the central elements and rationale for an analytical framework that integrates insights from critical disability studies and trauma theory. We have argued that taking this stance allows scholars to obtain a deeper understanding of the experiences and existential potential of disabled refugees. This frame can also serve as a moral touchstone for efforts to promote this population’s engagement in their new communities and to support their agential efforts to secure needed changes in their environments.

The notion of “embodied” experience from critical disability studies allows scholars to articulate and enact a contextual and dynamic understanding of disabled refugees’ efforts to exercise their individual and collective agency rather than view them simply as traumatized passive victims. In turn, a sociocultural perspective on trauma allows analysts to identify resources and services disabled refugees may require as they address continued psychological distress and physical and emotional vulnerability. Integrating these notions of “embodied” agency and resilience in this way contributes to both critical disability and refugee studies. We hope here to stimulate conversation in both fields concerning how insights into the lives of disabled refugees can be framed to affirm positive ways of their becoming, thereby improving the possibilities for any needed social changes as well.

Future research could expand this framework by systematically incorporating gender, age and other intersectionalities into it. For instance, recent inquiry has demonstrated that trauma manifests differently in men and women, and that women are less likely to obtain refugee status than men due to greater barriers in the asylum-seeking process [

26]. Consequently, these experiences may affect how they make sense of potentially traumatic events, respond to, and recover from, those, and, ultimately, and hopefully, thrive thereafter.