1. Introduction

Advanced biotechnology offers numerous advantages including the ability to engineer organisms for the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and other valuable compounds. It enables simulation-driven predictions for genetic modifications leading to enhanced yields, improved biotechnological traits, and reduced environmental impact. Biotechnology also plays a critical role in the development of sustainable agriculture, environmental remediation, and the development of personalized medicine [

1,

2]. A wide range of microorganisms with different metabolic features are actively used as a microbial chassis in biotechnology: heterotrophic bacteria like classical representatives,

Escherichia coli [

3] and

Corynebacterium glutamicum [

4] or interesting and widely employed in the fermentation industry a microbial group - lactic acid bacteria like

Lactococcus lactis [

5], and

Bacillus megaterium that characterized for general probiotic properties [

6]. Methanotrophic bacteria such as

Methylococcus capsulatus [

7],

Methylotuvimicrobioum alcaliphilum 20Z

R [

8] have an active application in biotechnology. The diversity of industrial microbial chassis and the corresponding increase of high-throughput experimental data for them led to the intensified application of system biology approach, which gives an opportunity to aggregate different omics data and analyze them in the framework of a union modeling system. The widely used constraint-based modeling gives an opportunity to reconstruct metabolic models on the genome scale level (GSM models) providing an analysis of the bacterial metabolism at steady-state [

2,

9]. Moreover, such algorithms as OptKnock [

10] gives an opportunity for in silico analysis of potential genetic modifications which will result in enhancing the level of target compounds production. For example,

iJO1366 GSM model for

Escherichia coli has been used to optimize the production of biofuels and chemicals by predicting and modifying metabolic pathways [

11].

Lactococcus lactis models were applied to enhance lactic acid production in dairy fermentation [

12]. Single-species GSM models remain valuable in silico tool especially when integrated with more advanced systems biology approaches that incorporate multi-species interactions and dynamic environmental factors. These integrated approaches can significantly improve the predictive power of GSM models, making them more relevant for biotechnological applications [

13,

14]. However, co-existence and joint dynamic functioning of several microbes during the fermentation on industrial scale significantly impact and constrain the application of single-species GSM models in order to describe and predict the community behavior. To address this, a modeling of microbial communities has emerged as an essential theoretical basis for industrial biotechnology. Constraint-based metabolic community (CBMc) models integrate the metabolic capabilities of multiple species to predict collective behavior and metabolic interdependencies [

15,

16]. There is a list of widely used tools such as cFBA [

17], MICOM [

18], SteadyCom [

19], PyCoMo [

20], Kbase [

21,

22] but all of them excluding Kbase have no web-application and user friendly-interface in addition [

16].

One of the actively employed groups of microorganisms in biotechnology are methanotrophs which play a critical role in the global effort to mitigate methane, a potent greenhouse gas. These microorganisms utilize methane as their primary carbon and energy source, which has significant implications for environmental management and biotechnological applications, including bioremediation, biofuel production, and the synthesis of high-value products [

23]. One of the widely used methanotrophs is

Methylococcus capsulatus, which is actively harnessed in modern biotechnology for production of single-cell protein. It was shown that it benefits from being part of a microbial consortium in bioreactor conditions, where interactions with other species enhance methane oxidation efficiency, provide additional metabolic pathways, and improve nutrient availability. Co-cultivation can also mitigate the accumulation of toxic by-products, such as formate or acetate, which can inhibit methanotrophic activity if not removed by partner organisms.

Heterotrophic bacteria, such as species from the

Bacillus genus and

Paracoccus denitrificans, play a crucial role in consortia with

M. capsulatus, significantly enhancing the growth, stability, and metabolic efficiency of these communities. These bacteria engage in synergistic interactions with

M. capsulatus, contributing to effective nutrient cycling, detoxification of harmful by-products, and improved production of valuable compounds [

7]. Recent research has explored the potential of engineered

Escherichia coli strains as satellite organisms in synthetic consortia with

Methylococcus capsulatus.

E. coli can be genetically modified to consume by-products of methane oxidation, such as acetate, thereby reducing the metabolic burden imposed on

Methylococcus capsulatus and enhancing overall methane conversion efficiency. Notably, a study by [

24] demonstrated that

E. coli could utilize acetate and other organic acids produced by methanotrophs that promotes methanotroph growth under co-cultivation conditions. Additionally,

E. coli has the capability to produce valuable metabolites, including L-homoserine from acetate, potentially affecting the amino acid metabolism of methanotrophs [

25].

Despite the increasing number of genome-scale metabolic models (GSMs) for methanotrophs [

26,

27] and software for community modeling, applications of CBMc modeling applorach to methanotrophic communities remain sparse. Two recent studies by Islam et al., 2020 [

28] and Badr, He & Wang, 2024 [

29] have investigated microbial community dynamics, but comprehensive CBMc models that describe methanotroph-satellite interactions in bioreactor conditions are still lacking.

Herein we demonstrate a workflow using the BioUML platform [

30] for CBMc models reconstruction to analyze the interactions between

Methylococcus capsulatus and an engineered

E. coli strain under oxygen and nitrogen-limited conditions in bioreactors. Our objective is to evaluate the potential of

E. coli to reduce methanotroph by-products, particularly acetate, and assess its impact on the growth and metabolism of

Methylococcus capsulatus using a community metabolic modeling approach.

2. Results

2.1. Modifications of the iMcBath Model

Methylococcus capsulatus strain possesses two isoforms of methane monooxygenase (MMO): particulate (pMMO) and soluble (sMMO), with their activity modulated by copper concentration in the media. sMMO is active under low copper concentrations, whereas pMMO operates under high copper conditions [

31,

32,

33]. Both enzymes catalyze the critical step in methane assimilation which is a methane oxidation to methanol requiring an electron donor. Based on Lieven and coathours results [

34] an uphill electron transfer mode in which the pMMO isoform is active was chosen. Despite the modifications made, the model did not correctly describe the production of by-products under oxygen and nitrate limiting conditions. However, according to the experimental data [

7,

24]

M.capsulatus produces an acetate as a by-product under these limiting conditions. The secreted acetate will lead to the decrease of the pure methanotrophic culture growth. It causes the strain co-cultivation with other satellite bacteria which consume the excreted acetate as a carbon source. To determine the discrepancy cause between the model simulation and experimental data for the strain, we make a comparison of the metaboli map with an alternative model for

M.capsulatus (

iMC535) and a model for

M.alcaliphilum 20Z

R and change the reversibility of reactions in central metabolic pathways. The activity of H

4MPT, RuMP, ED, and EMP pathways was also modified (details: Materials and Methods). In contrast, the original model exhibited a flux of 12.3 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ through the H

4MPT pathway, significantly higher than the 6.1 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ flux through the RuMP pathway. To address this discrepancy, we adjusted the upper and lower bounds of the FAEi reaction (the initial step in the H

4MPT pathway) relative to the FALDtpp reaction. The flux of formaldehyde from FALDtpp into H

4MPT was reduced by a factor of 2.2, resulting in an 8.39 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ flux through H

4MPT, consistent with a total FALDtpp flux of 18.5 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹. The ED pathway is known to be more active than the EMP pathway in

M.capsulatus. However, in the original model, the ED flux was zero. To resolve this, we incrementally redirected flux from the AH6PI reaction to the first reaction in the ED pathway (details: Materials and Methods). The model began producing acetate under the uphill electron transfer mechanism once the ED pathway flux reached 6 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, aligning with previous findings [

34]. Furthermore, by setting fixed constraints on the studied metabolic pathways and reducing nitrogen/oxygen availability, we observed an increase in acetate production (

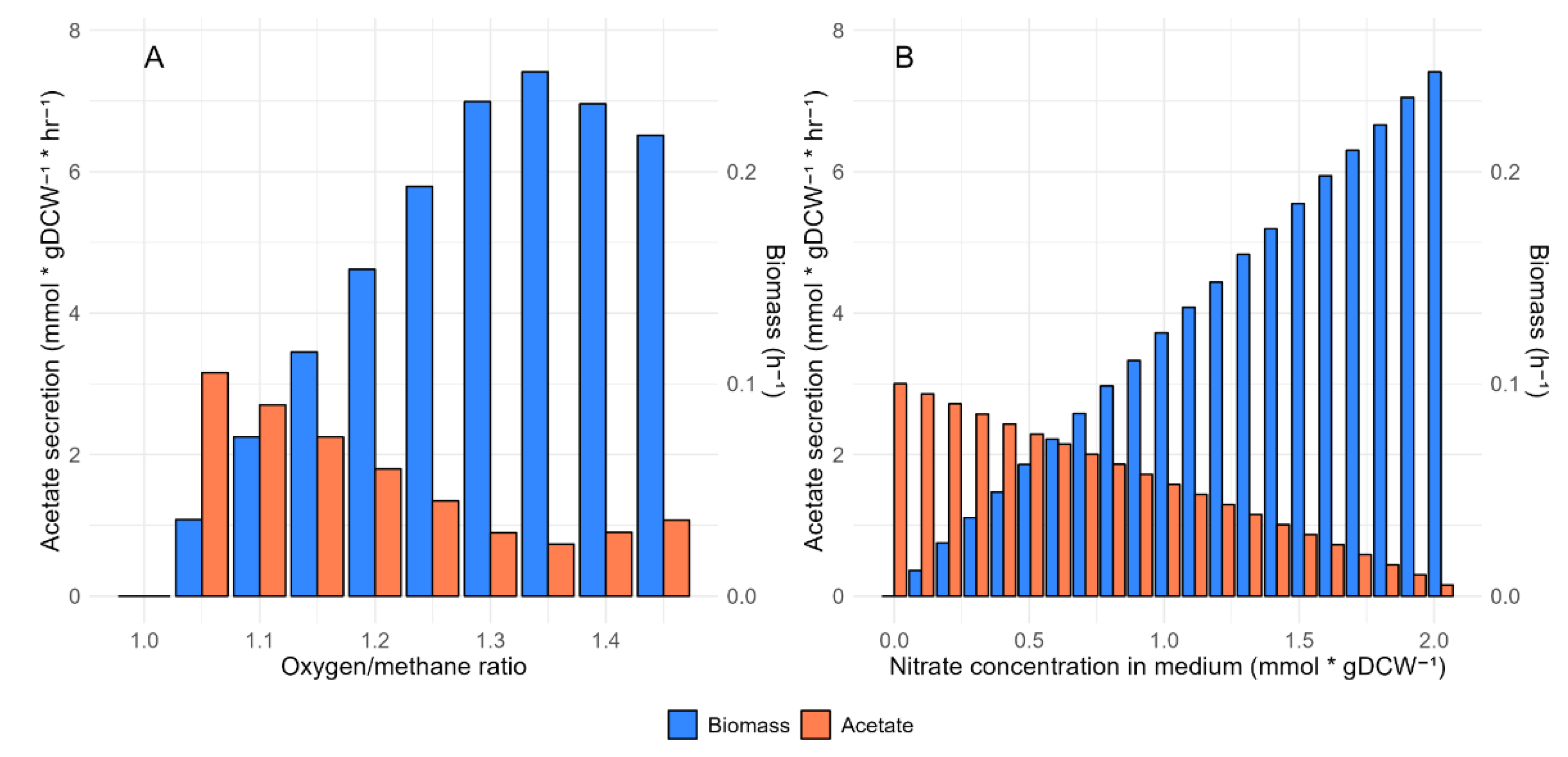

Figure 1).

2.2. Modification of the E.coli GSM Model iEC1372_W3110 for L-Homoserine Production

The recent study by [

25] demonstrated the potential for homoserine production in

Escherichia coli through flux balance analysis of the

iEC1372_W3110 model. To validate and expand upon these findings, we identified a metabolic configuration with maximal homoserine output, characterized by elevated fluxes through L-aspartase and acetyl-CoA synthetase pathways. Under these optimized conditions, the model predicted a homoserine production rate of 10.22 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ (

Table 1).

To explore the genetic interventions necessary to enhance the homoserine synthesis while maintaining non-zero biomass production, the OptFlux tool [

35] was applied. Our analysis revealed that viable in silico modified strains were attainable only when biomass was reduced to 40% of its wild type level. We prioritized a variant exhibiting an eightfold flux increase through the pyrophosphate transport reaction (PItex) for further experimentation (Supplementary

Table 1). The increased flux and active L-aspartase and acetyl-CoA synthetase pathways result in homoserine production at a rate of 5.365 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, with a corresponding growth rate of 0.369 h⁻¹ (

Table 1).

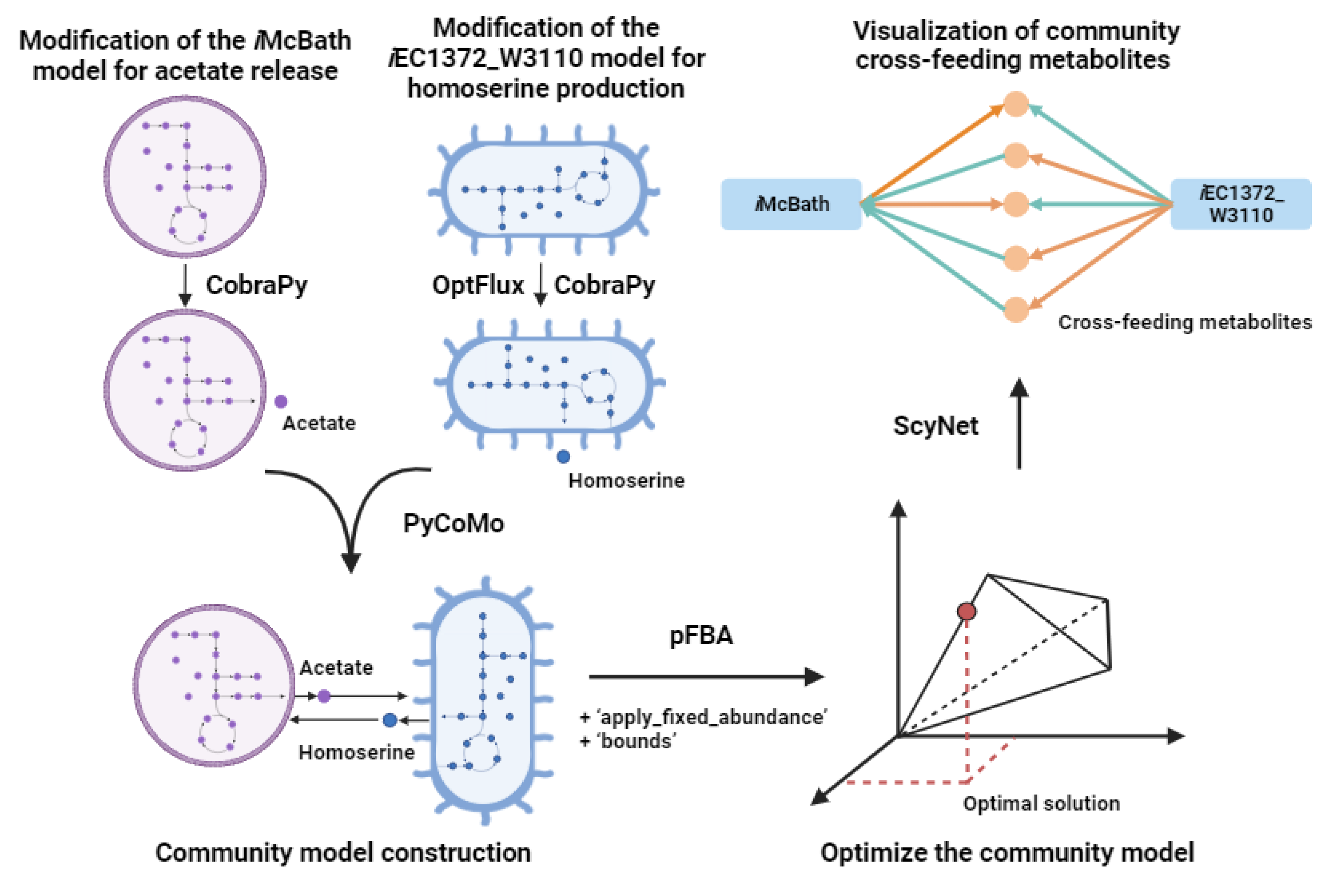

2.3. Reconstruction of the Community Model for M.capsulatus and E.coli

To build a workflow for the community modeling, Jupyter Notebook [

36,

37] was employed. The computational platform includes Python-based tools such as COBRApy [

38], MewPy [

39] and PyCoMo [

20] to give an opportunity for reconstruction of the community GSM models. Four community models comprising modified models for

M.capsulatus and

E. coli were constructed based on PyCoMo built-in the BioUML platform (

Figure 2). These models describe the

iMcBath model under oxygen-limited and nitrate-limited conditions, where acetate produced as a by-product is utilized by

E. coli as a carbon source. It is worth to note that two variants of

E. coli models were used: the unmodified

iEC1372_W3110 and the modified version for homoserine production. These alternatives were considered to investigate the potential influence of homoserine (details: Materials and Methods).

To achieve the oxygen and nitrogen limitation conditions, we reduced their concentrations in the bacterial growth medium. To simulate the oxygen limitation, its concentration was restricted to 22.152 mmol·gDCW⁻¹ (based on an oxygen/methane ratio of 1.2). Additionally, to establish oxygen-limited conditions in the community, a strict boundary was set on methane consumption for iMcBath (18.46 mmol·gDCW⁻¹) to maintain the necessary oxygen/methane ratio. To limit the nitrogen content, the concentration was reduced to 1.838 mmol·gDCW⁻¹ (60% of the total required for normal growth in the iMcBath and iEC1372_W3110 models).

2.4. Analysis of the Interactions between M.capsulatus and E.coli in the Microbial Community

Oxygen-limited conditions result in distinct growth rates for the unmodified

iEC1372_W3110 (0.225 h⁻¹) and the homoserine-producing

iEC1372_W3110 (0.186 h⁻¹;

Table 2). In contrast, the community models with both the unmodified and modified

E. coli exhibited identical growth rates of 0.217 h⁻¹ under nitrate-limited conditions (

Table 2). To identify differences in metabolites and reaction fluxes distribution in different version of the community model the cross-feeding metabolites and corresponding fluxes were visualized using ScyNet [

40].

Oxygen-Limited Conditions

To simulate oxygen-limited conditions, the methane transport was restricted in the iMcBath model (details: Materials and Methods), while oxygen consumption rate from the medium was set to 22.152 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹. The flux balance analysis indicated that both modified and unmodified E. coli variants experienced microaerobic conditions, likely attributable to M. capsulatus dominating oxygen consumption. Additionally, nitrate reductase activity was observed in both community models, though notable differences in nitrogen sources utilized by each bacterium were found out. In the model with the modified E. coli, both bacteria utilized NO₃⁻ as their primary nitrogen source. M. capsulatus and E. coli consume NO₃⁻ at rates of 8.467 and 2.879 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, respectively, leading to NO₂⁻ production in the medium by both organisms. Furthermore, M. capsulatus produced NH₄⁺ at a rate of 0.8473 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, which was subsequently consumed by E. coli at a rate of 0.7755 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹. In contrast, in the community model with unmodified E. coli, nitrate reductase activity was only observed in the M. capsulatus model, where NO₃⁻ was reduced to NO₂⁻. This NO₂⁻ was utilized by E. coli as a nitrogen source using nitrite reductase (0.0589 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹). Despite the availability of NO₂⁻, ammonium produced by M. capsulatus remained the primary nitrogen source for E. coli at a flux of 0.9811 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹. The increased production of ammonium by M. capsulatus could be contributing to the observed rise in the growth rate of the community (Supplementary Figures 1-2).

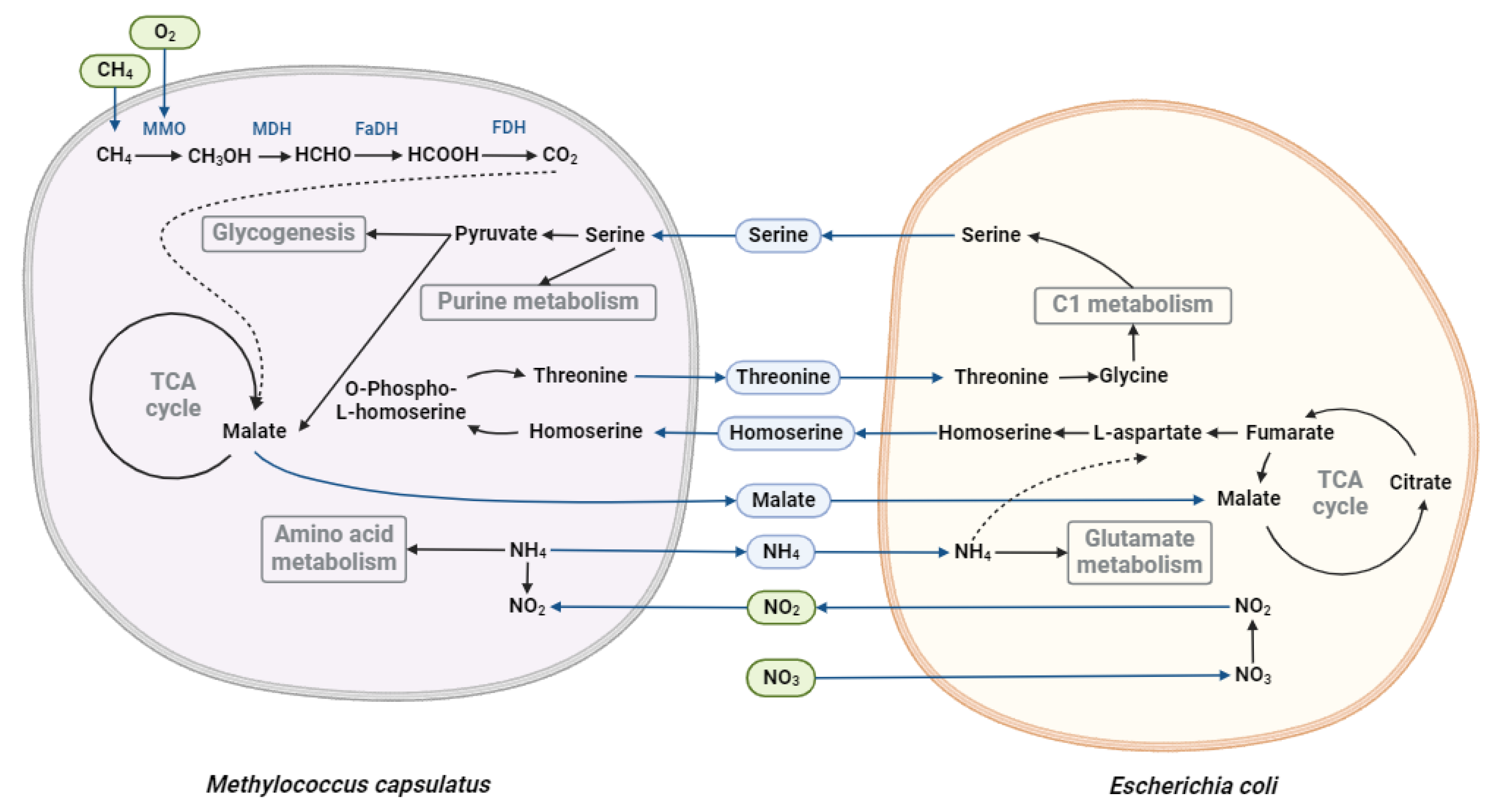

The primary carbon source for E. coli in the community model incorporating the unmodified iEC1372_W3110 is acetate produced by M. capsulatus, which is converted into acetyl-CoA and subsequently to pyruvate. Meanwhile, methane remains the main carbon source for M. capsulatus. Notably, E. coli also produces glycerol (0.908 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹), which M. capsulatus metabolizes through the GLYCDx (glycerol dehydrogenase) reaction, resulting in the formation of dihydroxyacetone. This intermediate enters to the DHAK (dihydroxyacetone kinase) reaction, producing dihydroxyacetone phosphate. This compound is processed in the TPI (triose-phosphate isomerase) reaction generating glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, which goes to EMP further. E. coli in the model version also produces minor amounts of succinate, which serves as another carbon source within the community. In addition to classical carbon sources like sugars and C1 metabolites, amino acids can also serve as both carbon and nitrogen sources simultaneously. A range of cross-feeding amino acids between modeling strains in the analyzed community is observed. M. capsulatus produces threonine, while E. coli contributes aspartate, serine, and homoserine to the shared metabolic pool. Threonine produced by M. capsulatus is utilized by E. coli via the THRD_L (L-threonine deaminase) reaction, yielding 2-oxobutanoate and ammonia. Whereas aspartate produced by E. coli is employed by M. capsulatus in the ASPTA (aspartate transaminase) reaction to synthesize L-glutamate and oxaloacetate, the latter being an intermediate in the TCA cycle. Serine from E. coli is used by M. capsulatus in the GHMT2r (glycine hydroxymethyltransferase) reaction for the production of methylenetetrahydrofolate, which is involved in purine metabolism. Interestingly, despite the absence of genetic modifications for L-homoserine production, the community model predicted that E. coli would produce homoserine at a flux of 0.282 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹. This homoserine is entirely absorbed by M. capsulatus and predominantly used in the HSK_GAPFILLING (homoserine kinase) reaction. The resulting O-phospho-L-homoserine is completely directed into the THRS (threonine synthase) reaction, leading to the production of phosphate and threonine, which is then consumed by E. coli as described above (details: Supplementary Figures 3). Additionally, the model predicts the exchange of water and phosphates between the community members, highlighting the intricate metabolic interdependencies within the community.

Despite identical environmental conditions, analysis of the community model with the modified iEC1372_W3110 revealed cross-feeding differences compared to the unmodified model. The carbon sources for E. coli in this community include acetate, malate, and glycerol, where malate serves as the primary source (1.144 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*h⁻¹), which E. coli utilized in the TCA cycle via the MDH (malate dehydrogenase) reaction. It should be noted that acetate production decreased by 16.3 times in the modified community (from 3.343 to 0.205 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) compared to the unmodified model version, which could explain the decreased growth rate of the community. Additionally, a small amount of glycerol (5.3 × 10⁻⁴ mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) produced by M. capsulatus is metabolized to dihydroxyacetone, which subsequently leads to the formation of fructose-6-phosphate feeding into the pentose phosphate pathway. Similar to the community with the unmodified E. coli, minor amounts of succinate are produced by E. coli and consumed by M. capsulatus.

As in the above described model version, E. coli produces serine, which M. capsulatus utilizes in the GHMT2r (glycine hydroxymethyltransferase) reaction for methylenetetrahydrofolate production. However, part of the serine is also metabolized via the SERD (serine deaminase) reaction, resulting in the formation of pyruvate and ammonia. This metabolic shift is primarily associated with the increased production of homoserine by E. coli, which nearly doubled (from 0.282 to 0.575 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) comparing to the unmodified model. M. capsulatus almost entirely consumes this homoserine via the HSK_GAPFILLING reaction, leading to the formation of O-phospho-L-homoserine. This intermediate is a substrate to the THRS (threonine synthase) reaction for threonine synthesis, which is incorporated into the community. The increased homoserine production results in higher threonine production by M. capsulatus. E. coli utilizes this threonine in the THRA (threonine aldolase) reaction to synthesize glycine, which is subsequently used in the GHMT2r reaction to regenerate serine (Supplementary Figures 4). This exchange mechanism provides an alternative pool of pyruvate for M. capsulatus and contributes to the observed decrease in acetate production. However, this shift also correlates with the decreased growth rate of the cells. Additionally, sodium ions produced by E. coli were identified as another cross-fed metabolite in this community.

Nitrate-Limited Conditions

In addition to exploring oxygen-limited conditions, the impact of nitrogen limitation on acetate production in

M. capsulatus was investigated. Nitrates were selected as the nitrogen source, and a constraint was applied by limiting the flux value of nitrates in the medium to 1.838 mmol*

gDCW⁻¹. Despite the sufficient oxygen availability both community models predict microaerobic conditions for

E. coli leading to nitrate reduction to nitrites. However, nitrogen exchange between the bacteria differs under these conditions (

Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). In the community with unmodified

iEC1372_W3110 both community members consume nitrates from the medium (1.406 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ by

M. capsulatus and 0.432 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ by

E. coli). In contrast, only

M. capsulatus consumes nitrates under oxygen-limited conditions. Additionally,

E. coli produces ammonium under nitrate-limited conditions, while under oxygen-limited conditions,

E. coli consumes ammonium. But only

E. coli utilizes nitrates as a nitrogen source in the community with the modified

iEC1372_W3110, while

M. capsulatus uses the nitrites produced by

E. coli reducing them to ammonium, which in turn are subsequently consumed by

E. coli. This interaction is likely linked to amino acid exchanges between the bacteria, which we first compared to understand this dynamic better.

Unlike the oxygen-limited conditions, the amino acid composition in this community only consisted of small amount of homoserine secreted by

iEC1372_W3110 (at a flux of 0.126 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹), which was produced regardless of whether the

iEC1372_W3110 was modified. This homoserine is almost entirely utilized by

M. capsulatus in the HSK_GAPFILLING reaction, followed by threonine synthesis via the THRS reaction. However, unlike predictions for oxygen-limited conditions, threonine production is not observed in this scenario. Furthermore,

E. coli produces a small amount of phosphates and sodium ions, which are also consumed by

M. capsulatus. Second, some differences in amino acid exchange between the modeling strains in the community with the modified

E. coli are observed.

E. coli produces homoserine with the flux of 0.572 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, which, is pretty the same as in oxygen-limited conditions. Homoserine is consumed by

M. capsulatus via previously described mechanism and leads to the threonine synthesis. The resulting threonine is incorporated into the community, where it is utilized by

E. coli in C1 metabolism. As in the oxygen-limited community with the modified

E. coli, the serine produced by

E. coli is employed by

M. capsulatus in the GHMT2r reaction and in the SERD reaction for the synthesis of pyruvate and ammonium (

Supplementary Figure S7). The increased production of pyruvate boosts the TCA cycle activity in

M. capsulatus, leading to the formation of malate and fumarate. The consistent mechanism of amino acid exchange observed under both oxygen- and nitrate-limited conditions, particularly with the active production of homoserine, suggests a significant role for homoserine in modulating

M. capsulatus metabolism and influencing the metabolic interactions between the bacteria in the community (

Figure 3).

The primary carbon source for

E. coli in the community model with the unmodified

iEC1372_W3110 is acetate (0.612 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) produced by

M. capsulatus, along with malate (0.126 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) and minor amounts of glycerol (6.2 × 10⁻⁴ mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹) absorbed by

E. coli. The lower availability of these carbon sources compared to oxygen-limited conditions likely accounts for the differences in the observed growth rates. Meanwhile,

M. capsulatus also utilizes methane from the medium as its carbon source at a consistent rate. When analyzing the community with the modified

iEC1372_W3110 under the same nitrogen-limited conditions, additional differences are noted (

Supplementary Figure S8). Firstly, malate is the primary carbon source for

E. coli, with its production tripling (from 0.361 to 1.197 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹), similar to the pattern seen in oxygen-limited conditions. However,

M. capsulatus ceases producing acetate and instead produces fumarate, which is absorbed by

E. coli as an additional carbon source. Malate and fumarate are utilized by

E. coli in the TCA cycle through the MDH (malate dehydrogenase) and FUM (fumarase) reactions, respectively. Interestingly,

M. capsulatus slightly reduces its methane consumption from 18.46 to 17.71 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹, while the growth rates between communities under nitrogen-limited conditions remains unchanged. This suggests that the production of pyruvate from serine under these conditions is more effective than under oxygen-limited conditions.

3. Discussion

Despite published data supporting acetate secretion by

M. capsulatus in a certain limited condition, the original

iMcBath model did not demonstrate this. As a result, we analyzed the model's metabolic pathways and found the absence of acetate transport and exchange reactions. Therefore, we added the corresponding reactions following the example of the

iIA409 model. Additionally, we set the proportions of fluxes through the RuMP and H

4MTP pathways according to the study by [

41]. A key aspect for the correct functioning of the

iMcBath model is the activity of the Entner-Doudoroff (EDD) pathway, which initially has zero flux. The importance of this pathway is also highlighted in [

41], where it is described as one of the key pathways for NADPH and 6-phospho-D-gluconate synthesis, an intermediate product of the EDD pathway. We selected an optimal flux for the reaction based on [

41], but additional experimental data are needed to confirm the activity of both the EDD and EMP pathways in the strain. Due to the modifications introduced, the

iMcBath model predicted the acetate production. However, the rigid constraints on flux bounds artificially narrow the solution space, reducing the model flexibility and limiting its applicability in further studies. Therefore, a more detailed investigation of the metabolism of

M. capsulatus is required to refine and improve the model accuracy.

To enable homoserine production while maintaining non-zero biomass in the

iEC1372_W3110 model, we increased the flux through the pyrophosphate transport reaction (Pitex). OptFlux offered various solutions for homoserine production in

E. coli (see

Supplementary Table S1). However, we opted for the Pitex modification because it involved minimal intervention without altering the internal metabolism of the organism.

M. capsulatus consumes a greater amount of nitrates, which act as electron acceptors during methane oxidation and are reduced to N₂O under oxygen-limiting conditions. However, the formation of N₂O does not occur due to the incomplete description of its reduction process in the

iMcBath model. Thus, it is likely that the

iMcBath model favors the reduction of nitrates to nitrites [

42] rather than to ammonium, which explains the excess nitrite release into the medium. These nitrites are partially consumed by

E. coli along with ammonium, which is produced by

M. capsulatus in significantly smaller amounts compared to nitrites. Additionally,

E. coli produces aspartate, which is consumed by

M. capsulatus as an additional nitrogen source. The

E. coli strain in oxygen-limited conditions and homoserine present in the medium consumes nitrates from the environment for homoserine synthesis, reducing its reliance on nitrogen sources produced by

M. capsulatus.

M. capsulatus continues to supply ammonia to

E. coli, as it requires less energy for the cell to utilize, while also releasing excess nitrites and ammonia into the medium. Moreover, aspartate ceases to be a metabolite for cross-feeding, and we hypothesize that the reduced growth rate of

M. capsulatus in this community is linked to the loss of aspartate as an additional nitrogen source.

The opposite situation is observed under nitrate-limited conditions:

E. coli becomes the main nitrogen donor reducing nitrates to ammonia [

43] and supplying it to

M. capsulatus for amino acid synthesis. In the case of modified

E. coli, the only nitrogen source for

M. capsulatus in the community is the nitrites produced by

E. coli, which

M. capsulatus reduces to ammonia, subsequently consumed by

E. coli. Based on the fluxes analysis for nitrogen sources in the community we can also indicate that the modified

E. coli requires a larger amount of nitrogen sources, including nitrates from the medium and ammonium ions, which are utilized for amino acid (serine and homoserine) synthesis. Furthermore, we can assume that this nitrogen exchange is feasible, as both models contain all necessary reactions for nitrate reduction to ammonia, while this division of metabolic features helps reduce energy costs associated with nitrogen source reduction.

Amino acid exchange is a common occurrence in microbial communities [

44,

45], and this exchange reduces the metabolic burden on individual strains, helping to maintain optimal growth particularly under limiting conditions [

46,

47]. In the study by Wang et al. (2019) [

45], interactions within a community of

Dehalobacter restrictus and

Bacteroides sp. were analyzed, revealing that

Bacteroides sp. produces malate when growing on lactate. The malate is consumed by

D. restrictus for the synthesis of excess NADH. Additionally,

D. restrictus released amino acids, such as glutamate, into the medium, which further contributed to NADH production. The generated NADH is utilized by

Bacteroides sp. for the production of NADPH. The threonine present in the medium is consumed by

D. restrictus for serine synthesis, illustrating the important role of amino acid cross-feeding. In this microbial community, the production and consumption of malate and amino acids represents a strategy to bypass the impermeability of cell membranes for necessary reducing equivalents (NADH/NADPH) [

45]. However, these experiments were conducted with gram-positive organisms, and further experimental validation is needed to confirm similar amino acid exchange in methanotrophic communities involving

E. coli.

Our hypothesis about serine and threonine exchange in the community is also supported by the fact that

E. coli uses malate and threonine (reaction THRD with flux value 0.434 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ and 0.456 mmol*gDCW⁻¹*hr⁻¹ under nitrigen- and oxygen-limited conditions respectively) provided by

M. capsulatus for NADH synthesis. The serine produced by

E. coli is consumed by

M. capsulatus for pyruvate synthesis via serine-pyruvate aminotransferase activity [

48], which is employed to produce the malate necessary for

E. coli. Serine, in turn, is an important metabolite for

M. capsulatus due to its use in the partial serine cycle. Additionally, mutants lacking serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (SGAT), which in

M. capsulatus also possesses serine-pyruvate aminotransferase activity, did not show reduced growth rates, but they did exhibit a longer lag-phase [

48,

49].

Thus, we hypothesize that it is more advantageous for the community to utilize malate instead of acetate in the microbial community with modified

E. coli, due to its increased NADH demand. Since the acetate negatively affects the growth rate of

M. capsulatus [

7], such interaction in the community may be beneficial by reducing acetate levels in the medium.