1. Introduction

Stimulating sustainable communities is fundamental for the development of a country, since sustainability encompasses the resolution of social, political, cultural, economic and environmental problems [

1]. In this sense, the United Nations (UN) presents, in its 2030 agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2 - Zero Hunger and Sustainable Agriculture and 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities, that aim to make communities safer, resilient, and ensure sustainable food production systems that meet present and future demands [

2].

The term sustainable communities refer to groups of people who live for long periods in an environment that is interconnected with other environments and have access to both endogenous and exogenous resources, such as “time, finance, devices, people, institutional knowledge, networks and the built and physical environment” [

3] (p.04). In this way, the sustainable development of a community permeates to “protect and improve the environment, answer the social needs and promote the economic success” [

4] (p. 01), contributing to the life quality of those who participate in it.

In alignment with development theories, emphasis has been placed on territorial systems, linking geographic concentration and local conditions to the promotion, attraction, and growth of activities that are developed within these contexts. The concentration of activities generates economies of scale, reduces transportation costs, and facilitates access to new knowledge [

5].

Agribusiness is one of the most dynamic and important sectors of the Brazilian economy [

6]. In this way, the development of sustainable communities provides a transformation in rural areas, improving socioeconomic conditions, ensuring environmental preservation and the efficient use of natural resources. In addition, the implementation of digital technologies can be seen as a milestone in this development [

7], since digitalization acts as a catalyst for agricultural development, offering a new path to more sustainable practices [

8].

The adoption of a rural development model that includes the integration of agricultural practices and the adoption of digital technologies can transform rural communities into innovation centres, as in the concept of the Agrotechnological District (ATD). The term 'technological district' refers to a territorial system composed of relational components, infrastructures and cognitive and technological learning processes, requiring qualified labour, a strong network of cooperation between actors and the support of a series of innovation-oriented institutions [

5].

The transformation of a rural community into an ATD aims at its productive efficiency in addition to local sustainability by providing several benefits, such as reducing excessive working hours, saving resources and increasing transparency across value chains, while reducing regional disparities in the development of digital agriculture [

7,

8].

In developing countries, small and medium-scale producers are key to ensuring food security as well as income generation in rural areas. However, they face challenges such as climate change, limited access to credit, poor infrastructure, and policy constraints. While there are numerous digital solutions to serve the agricultural sector and minimize these challenges, many smallholders are out of reach of these solutions, due to the high cost, and gaps in digital literacy and digital skills, beyond the lack of digital infrastructure such as connectivity and mobile network infrastructure [

9].

In this context, the ‘Semear Digital’ project emerges, developed by the Science Center for Development in Digital Agriculture (SCD-DA), a consortium between the institutions: Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation - EMBRAPA, Telecommunications Research and Development Center - CPQD, Institute of Agricultural Economics - IEA, Luiz de Queiroz Agrotechnical School - Esalq/USP, Agronomic Institute of Campinas - IAC, National Institute of Telecommunications - INATEL and Federal University of Lavras - UFLA, and funded by the Foundation for Research Support in the State of São Paulo - FAPESP. The objective of this consortium is to overcome inequalities in the countryside by encouraging the adoption of digital technologies among small and medium-sized rural producers, through the implementation of ATDs in Brazil. The eligibility of the municipalities to be transformed into ATDs was based on a methodology developed by the Institute of Agricultural Economics of the state of São Paulo, which relied on the following indicators: level of technical assistance, economy, education, land structure, infrastructure, social organizations, population and social. Based on these indicators, ten municipalities with the potential to become an ATD were selected, and Ingaí-MG was chosen as the representative of the dairy basin in the state of Minas Gerais (MG). Another nine municipalities, distributed in the main regions of Brazil, make up the scope of the project, namely: Caconde-SP, São Miguel Arcanjo-SP, Alto Alegre-SP, Jacupiranga-SP, Lagoinha-SP, Vacaria-RS, Guia Lopes da Laguna-MS, Breves-PA e Boa Vista do Tupim-BA [

10].

Brazil is one of the main milk producers in the world and dairy farming has great relevance for the local economy [

11], especially in Minas Gerais, an important centre of Brazilian agribusiness. In 2022, the state was the largest milk producer in the country, with 9.4 billion litres, which corresponded to 27.1% of the national production (and 80.6% considering the Southeast region), an amount widely higher than the second place, the state of Paraná, which corresponded to 12.9% of the Brazilian production in the same period [

12].

Despite Brazil being a major world producer of milk, with Minas Gerais leading the supply, Brazilian productivity is still not satisfactory. This limitation could be minimized using information and communication technologies for animal control and other activities, such as the Internet of Things (IOT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), computer vision, robotics, among others, which is called precision dairy farming [

13]. The adoption of digital technologies in milk production has the potential to further develop the activity, as they impact production efficiency, animal welfare and agile management of the property [

11]. These technologies can also improve management processes, increase production efficiency, and enable better decision-making by the producer, as these devices and sensors collect real-time data, such as herd behavior, health, milk production, and food consumption [

13]. In short, this monitoring helps producers to outline preventive actions for early intervention and “enables the promotion of the health and welfare of the entire life cycle of dairy cattle and the creation of better value for producers” [

13] (p.02).

Considering the context of milk production in Brazil and the adoption of digital technologies in dairy farming, this article aims to identify opportunities and difficulties for the transformation of Ingaí-MG into an ATD.

The innovative character of this study lies in the analysis of the transformation of Ingaí-MG into an Agrotechnological District (ATD), promoting the sustainable development of the dairy basin of Minas Gerais through the promotion of the adoption of technologies, especially the digital ones. The study stands out for addressing the digitalization of production as a catalyst for greater efficiency, better animal welfare, and more agile and accurate management. In addition, by focusing on a representative municipality of the milk production chain in Brazil, the study offers a regional perspective on how these technologies can reduce socioeconomic disparities, foster innovation in rural areas, and contribute to food security and sustainability.

To Prosperi et. al., the transformation of a region into an ATD involves a process of socio-technical transition, which means that in addition to the adoption of technologies by producers, it includes changes in institutional and cultural practices and structures, which results in the conceptualization of new products, services, business models, among others, reshaping the market in which the actors are inserted. Some factors that influence the formation of an ATD are: the characteristics of the district (infrastructure and institutional, political and technological environment), chain relationships and support networks (consortia, production associations, other organizations, informal contracts) and the features of the companies themselves – in the specific case of this study, of producers (gender, age group, propensity to risk and adoption of technologies) and rural properties (size, establishment age, governance and management, availability of resources and capital) [

14].

Gumbi et al. affirm that the successful adoption of digital agriculture by smallholder farmers depends on the existence of a functioning digital agriculture ecosystem within their context and environment [

9]. They also state that the development of a digital agriculture ecosystem depends on elements such as: the availability of digital platforms to access agricultural information, markets, finance, agricultural inputs, supply chain management, consulting and business intelligence services, innovations in business models, digital literacy, digital infrastructure, 4IR (Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Internet of Things, smart and remote sensors) and accessibility.

Meng et al. point out that the level of development of digital agriculture in a region can be measured through five indicators [

8]: (1) Digital Agriculture Infrastructure (rural delivery routes, total reservoir capacity, road mileage, rural electricity consumption, length of optical fiber cables); (2) Digital Agriculture talent resources (average years of education in rural areas, education expenditure; science and technology expenditure, average number of students enrolled in higher education); (3) Agricultural informatization level (the density of cell phone base stations, the number of internet domain names, rural broad band access users); (4) Digitalization of agricultural production process (the effective irrigated area, the total power of agricultural machinery, large and medium-sized tractors for agricultural use); and (5) Agricultural production efficiency (e-commerce sales, per capita disposable income of rural households, total input value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries). The authors point out that promoting the digitalization of agriculture aims to achieve high-quality and sustainable agricultural development, with the benefits reflected in production efficiency.

Silva et al. argues that there are gaps in the literature on the digital transformation of livestock in Brazil, making it difficult to obtain a national overview of this sector [

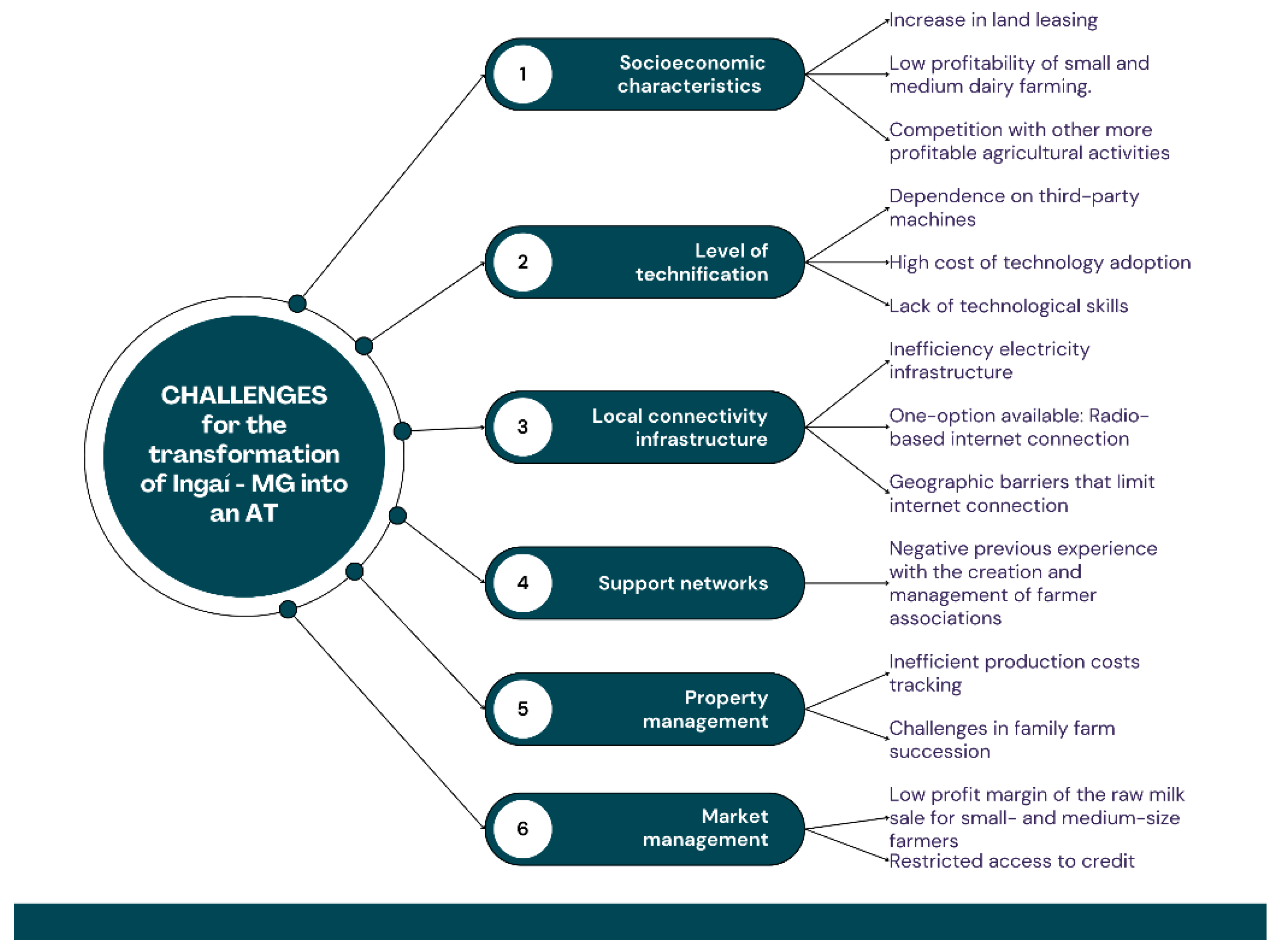

11]. Thus, the realization of a diagnosis of the municipality in question allows the identification of its potentialities and challenges for the transition to an agrotechnological district. Based on the studies of Prosperi, Sisto, Lopolito & Materia, Gumbi, Gumbi & Twinomurinzi and Meng, Zhao, Song & Lin, this diagnosis includes the Socioeconomic characteristics of the municipality; the producers' level of technification; the local connectivity infrastructure; the existing support networks, the characteristics of property, and the property and market management [

8,

9,

14] (described in

Figure 1). From this diagnosis, it is possible to propose strategies for the implementation of solutions that promote digital inclusion, improve infrastructure and strengthen support networks for small and medium-scale farmers, promoting sustainable development that not only respects the principles of the SDGs, but also contributes to a more prosperous and sustainable future for rural communities in Ingaí-MG, Brazil. In addition, the adoption of these initiatives can stimulate the economic and social development of the municipality, generate multiplier effects in its region of influence, as well as establish a benchmarking for other initiatives in the state of Minas Gerais, the main dairy hub in the country, and one of the main driving states of Brazilian agribusiness.

3. Results

This section aims to present the main results of this study, focusing on six analytical categories, which are: Socioeconomic characteristics of the municipality; Level of technification of producers; local connectivity infrastructure; existing support networks; property management; and market management.

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Municipality of Ingaí – MG, Brazil

Ingaí is a Brazilian municipality belonging to the state of Minas Gerais, mesoregion of Campo das Vertentes and whose region of influence is the municipality of Lavras – MG, with which it borders (

Figure 2). According to the IBGE Cities portal, the municipality of 305,591 km2 has a resident population of 2,580 inhabitants, indicating a region with low population density [

12]. As for the labour market, the municipality has 23.2% of the employed population with an average salary of 1.8 minimum wages, suggesting a low participation of the population in the formal labour market, which may be related to its rural and informal characteristics. In economic aspects, the GDP per capita of the municipality was R

$41,544.77 in 2021, which, despite seeming high for a small municipality, when analysed alone, the GDP per capita does not reflect the distribution of income, which can be concentrated. The HDI of 0.697 places the municipality in the "medium human development" range, according to the classification of the United Nations Development Program [

17]. Although it is not one of the lowest, there are still challenges in terms of quality of life, education, health, economic development, job opportunities and social inclusion.

Agribusiness is the main economic activity of the municipality, with 236 agricultural establishments, with an area of 21,908 hectares [

19]. Of the total number of producers, 88.55% are male, 79.66% are over 45 years old and 57.2% have schooling up to Elementary School. At the time, 960 people were employed in these establishments, and 49.68% were related to the producer [

19].

Regarding livestock, 191 establishments had herds, of which 145 were milk producers. The herd number was 16,331 heads, of which 4,382 were milked cows, that produced 20,647 thousand litres of milk, and a production value of R

$23,710,067, being this activity of great representativeness for the municipality [

19].

The main agricultural products of Ingaí-MG are described in

Table 2.

The first technical visit to the municipality of Ingaí - MG allowed an initial understanding of the socioeconomic profile of the region. According to data collected in the study, Ingaí has a total of 33 rural communities, the main ones being: Bocaina, Vargem Grande, Ajudante, Jaguara, Soca, Campestre, Barra, Ribeirão, Córrego Fundo and Cachoeirinha. The rural communities with the largest number of representatives of small and medium-scale agriculture are: Bocaina, Jaguara, Soca, Campestre e Cachoeirinha. According to the interviewees, the southwest region of the municipality "is more agribusiness", that is, in their perception, it is a larger-scale agriculture.

Ingaí - MG reveals a community predominantly composed of family farmers, in which the production of milk, coffee and grains plays a central role. According to the interview with the technicians and extension workers, the typical producer in the municipality consists of small milk producers who are also farmers, planting for their own consumption and selling the surplus or using it for animal consumption (corn). The meeting with representatives of a company that supplies inputs pointed out that the socioeconomic profile of milk producers in Ingaí - MG reflects a heterogeneous reality, in which small producers, a group predominantly composed of men over 45 years of age, constitute the majority (keeping in line with the data of the Agricultural Census [

19]), with an average production of 200 to 300 litres per day.

As pointed out by Bánkuti, Bánkuti & Souza Filho, the milk market in Brazil has undergone intense transformations, related to public policies and changes in the market, such as the need to intensify production, increase in the consumption of dairy products and greater competition from imported products [

20]. For the authors, producers need a larger scale of production, greater regularity of supply and a higher standard of quality, which can be achieved through the adoption of productive technologies. The authors add that these transformations have resulted in overflows, such as:

“the expansion of competition to a more systemic level; greater dispersion (differences) of prices paid to the producer, mainly due to volume; quality and bargaining power; stricter selection of market participants and expulsion of producers from the activity or to informality; severer negotiations between suppliers and customers; and changes in the relationships between agents” [

20] (p.45).

Along these lines, Martins et al. pointed out that one of the changes that occurred in the structure of milk production in Brazil over the last two decades was the reduction in the number of producers and the intensification of production systems [

21]. Although the municipality of Ingaí - MG has a tradition in dairy activity, the interviews indicated that, over the last few years, the activity has faced a decline due to the increasingly challenging economic viability of the sector, with many producers migrating to more profitable crops, such as grains (corn, soybeans, beans) and eucalyptus.

According to the interview with members of the producers' association, milk production has declined in recent years in the municipality, since "milk has stopped being profitable". For them, the cost of production is very high, labour is difficult to find, in addition to being an activity that requires great dedication from the producer. The representatives of the local agribusiness add that "rural work is difficult, heavy. The workload is difficult, you need to work on the weekend and holidays. The cow does not stop giving milk; It's 24 hours, 365 days a year.” In addition, the interviewees point out that the new generation is no longer interested in staying in the countryside, corroborating the literature that states that dairy farming, especially in family systems, does not offer attractive and desirable working conditions, as it is hard work, which can be exhausting, oppressive and unprofitable, depending on its management [6, 22]. Therefore, in some cases, family members choose to work outside the property. It was identified that the main employers in the region are City Hall, the local agroindustry and some companies in the municipality of Lavras - MG.

Considering all these challenges, many producers have opted for land lease to obtain income. According to one of the producers, "nothing pays the producer better than renting the land", especially in those properties that are not technified. This result is in line with Novo, Jansen & Slingerland, who stated that dairy production in the context of family farming still survives in the Southeast of Brazil, although land leasing has become a more profitable alternative [

23]. In Ingaí, the land is leased to produce eucalyptus, grains, tomatoes, coffee, soybeans and corn. Although leasing is an option, it was pointed out that leasing is only viable for larger properties. It is valid to say that, although milk production is declining, the interview with members of the local agribusiness points out that there is still potential for the dairy in the region.

3.2. Producers' Level of Technification

“The level of agricultural informatization is a critical dimension that mirrors the state of digital agriculture development” [

8] (p.04). In the context of Ingaí - MG, this development faces challenges, since the adoption of technologies is restricted among small producers due to high implementation costs and cultural resistance. This scenario is in line with the observations of Bánkuti, Bánkuti & Souza Filho, which highlight that the adoption of information technologies is considered low due to economic issues, the lack of knowledge of the farmer about these technologies and the data they generate [

20]. Gumbi, Gumbi & Twinomurinzi complete by stating that the challenges related to digital literacy by small and medium-sized producers include inadequate information about digital solutions, lack of perceived value, language barriers and lack of knowledge about digital solutions [

9].

Resistance to change is observed among producers in Ingaí - MG, influenced by distrust and attachment to traditions. According to one of the interviewees: “The resident of Minas Gerais is suspicious, but the small producer from Minas Gerais is even more [suspicious]”. Thus, it is necessary to create approach strategies that are sensitive to the needs and interests of producers, especially through practical examples and references.

According to technicians and extension workers, small-scale farmers are very dependent on third-party machines or machines from the city hall. This shows a scenario of limited capitalization in which few producers have machinery to meet their own activity. However, they are "simpler" machinery, mostly tractors, silage harvesters and trailers for transporting material and preparing the soil.

In the case of milk production, most have some level of technology, since without it, the producer cannot remain in the activity. In Ingaí - MG, milking is all mechanized and expansion tanks are used. The dairy itself, at times, requires the producer to use technology, for example, providing producers with management and financing applications and sending the analysis of milk quality through digital platforms.

The restriction on the use of technologies by small and medium-sized producers in Ingaí-MG can be noted when compared to contexts, such as, for example, in the production chain in Santa Catarina, as presented by Bonamigo, Ferenhof, & Forcellini [

24]. According to the authors, low technification is due to the supply of technology itself (lack of incentives, lack of interest from developers and manufacturers) and is related to the producer's profile (income limitation, lack of cooperation with other producers and low education). In addition, the complexity of agroecosystems is a complicating factor for the use of digital technologies [

7].

For members of the agribusiness, there is a tendency for young people to show more willingness to adopt technologies. It was reported that many times these young people are the ones who follow up, request the password to check the analysis of the quality of the milk and control the herd, while the most experienced producers, on several occasions, do not even consult the digital reports sent by the industry. It was also pointed out that the active participation of women has been effective in promoting the adoption of technologies in the field. Thus, an opportunity for the digitalization of livestock in Ingaí - MG is to promote specific training aimed at young people and women, encouraging their role as agents of digital transformation on properties. By fostering this participation, the digitalization of livestock can be accelerated, taking advantage of young people's interest in new technologies and the growing leadership of women in the management of rural activities, ensuring greater productive efficiency and modernization of the sector.

Despite the presence of young producers seeking to modernize the activity, the high costs of digital technologies impose barriers to their adoption, relegating most farmers to low complexity technification devices usage. It was pointed out in the various interviews that the internet is used for: GPS, meteorology (weather forecast), monitoring the property, reading veterinary medicine leaflets and taking their dosage, making quotes and purchases ("looking for a cheaper product"), sales ("taking a picture of a cow to sell to the neighbor”), communication via social networks ("talk", "say hi to the group", "look at TikTok”) and entertainment ("watching movies"). These results corroborate the study by Gumbi, Gumbi & Twinomurinzi, that identified that small farmers use digital solutions to access agricultural information, monitoring and tracking, marketing of products (purchase and sale), production, fertilization, communication, purchase of inputs, banking/economics, control of agricultural equipment, forecasting and credit evaluation [

9]. According to Bassoto et al. “it is possible that internet access contributes to dairy farms improving their technical efficiencies by allowing searches for new information” [

25] (p.4).

The introduction of digital technologies is seen as a possible solution by producers themselves, who recognize that it can help improve productivity. Also, “increasing production volumes leads to better prices per litter and the dilution of fixed costs” [

21] (p.3). But high costs and lack of knowledge pose barriers to their adoption, as can be seen in the subsection Local connectivity infrastructure. The use of technologies becomes attractive to producers because, in addition to improving crop production and productivity, they result in less environmental impact [

21,

24]. For the representatives of the local agribusiness, to remain in the activity, it is necessary to be technified: “No matter what, being small or large, those who are efficient and technified will remain. This is regardless of whether it is in milk, soybeans, oranges, corn, etc. It is a global movement. You must have financial, productive, professional and personal efficiency”. In addition, the same interviewees pointed out that producers feel the need for technification and are looking for it. However, it is necessary to provide support and training for the use of technology to be effective: “When you simplify, facilitate and empower him to do this, to use technology, he uses” (interview with representatives of the agribusiness).

3.3. Local Connectivity Infrastructure

Mellet & Beauvisage describe infrastructure as a series of objects that are invisible to market actors and that are necessary to support human activities, such as collective equipment and materials (bridges, energy and communication networks), as well as protocols and standards that create the terrain in which social life takes place [

26]. The authors argue that, when analyzing market infrastructures, it is important to analyze the activities that these infrastructures support and not only how these infrastructures are built [

26].

In its study, Gumbi, Gumbi & Twinomurinzi identified that research on digital infrastructure focuses on information and communication technology (ICT), mobile phone and broadband connection [

9]. To Meng, Zhao, Song & Lin, the infrastructure needed for the development of digital agriculture covers five aspects: rural delivery routes and road mileage (transport infrastructure, “essential for the movement of agricultural production, materials and products”); total reservoir capacity and rural electricity consumption (“resources for the digitalization of the agricultural production process”); and the length of optical fibre cables (“hardware foundation underpinning the advancement of agricultural informatization and digitization”) [

8] (p.03).

During the interviews, it was possible to identify that the infrastructure in Ingaí - MG faces significant challenges, with most rural communities having single-phase electricity, which is frequently interrupted. These oscillations affect milk production and milk quality, which needs energy for milking (mechanical, in almost all properties) and expansion tanks. According to technicians and extension workers, some larger producers already have photovoltaic energy on their properties and see its benefits, although they still depend on the network of the Energy Company of Minas Gerais (CEMIG) due to the costs of investments in batteries to store the energy generated. According to the interview with members of the local government, about 40 families do not have access to electricity because the land was irregularly established and cannot be registered.

Regarding the transport infrastructure, the roads that connect the region are dirt and their quality worsens in rainy seasons, which hinders the flow of production and access to properties. In addition, in relation to road mileage, it was identified that there are dairy industry 200 kilometres away that look for milk in Ingaí - MG, while the local dairy industry looks for milk within a radius of 150 km from the municipality.

Building connectivity infrastructure and promoting network coverage in rural areas is key to the development of digital agriculture [

8]. In Ingaí - MG, it was found that the connectivity infrastructure is underdeveloped, with internet access being limited and primarily radio-based. The mountainous terrain also contributes to areas with unstable communication signals, exacerbating the challenges of accessing information and technologies. According to representatives of internet service providers, even in regions where fiber-optic internet is available, it is received via radio and then distributed via fiber. It was noted that in some areas, the antenna signal does not reach the property. The region of Mato Sem Pau was identified as the most difficult area for internet access.

According to the same group of interviewees, there is a challenge in bringing fiber-optic internet to rural areas, due to the high costs and low population density that justifies the investment. In addition, the producer's culture is another obstacle, since "if he is already sure to use the radio-based internet access that works, he will not want to change". In this way, producers do not even request a viability analysis to take the fibre to the region. Another point addressed by the representatives was that they often carry out studies to improve radio connectivity in the region and determine strategic points to install the antennas. The cost of these antennas is around 30 to 40 thousand reais and companies are interested in installing them. However, producers do not allow antennas to be installed on their properties, as they take up too much space and are lightning rods, and can kill animals that are around, in case of electrical discharges.

Rural mobile telephony is an important means of communication for rural workers, who often remain away from urban areas [

27]. In Brazil, the main operators of mobile phone services are Vivo, Tim, Claro and Oi. In the region of Ingaí, the connection by cell phone is of variable quality, with a predominance of Vivo and Tim service providers. Starlink technology has been pointed as a solution, but it is still too costly for most producers.

An example reported by representatives of the agroindustry about the need for connectivity in the field is that the clinical laboratory sends the milk quality analyses to the producer by telephone signal, via message. If the producer is outside of the coverage area, he does not receive the message. Thus, the producer must access the system over the internet, which is often unstable on the property.

The interviewees also observed that the lack of connectivity is a problem that hinders not only the work, but the permanence of the producer in the field, especially when family demands arise. Some examples highlighted were the education of children and young people in the pandemic, the difficulty of communication and the lack of entertainment. According to one of the producers, "my boys, if the internet connection goes out, they get in the car and leave."

While there is interest in establishing fiber-optic internet infrastructure by enterprises, high costs and geographic challenges pose significant barriers. The interview with local internet providers indicated that the companies are interested in the project and willing to carry out partnerships and studies in the area in order to improve connectivity in the region. Respondents emphasised that the producer's need for connectivity is increasing, little by little, with the emergence of "smart homes, security cameras and smart farms". So, "the producers themselves will need a better connectivity infrastructure and will demand the availability of this service," add the local internet providers.

3.4. Existing Support Networks

Prosperi et al. express that in the process of transforming a region into a technological district, cohesion among all stakeholders is necessary [

14]. For the authors, support networks influence innovation capacities through the sharing of information and knowledge, thus creating a favorable environment and ensuring learning for the promotion of new technologies among local actors.

Regarding the producer support networks, it was reported that the Association of Rural Producers of Ingaí - MG was created in 2005, with the aim of commercializing production jointly, but has lost its strength in recent years. This information contrasts with Bassoto et al who state that “in Minas Gerais, milk farmers are likely motivated to participate in collective organizations” [

25] (p.4). One of the difficulties pointed out by the producers in relation to participation in the association was due to the milk producer's own routine, as he is unable to leave the farm to participate in meetings and collective decisions. The lack of effective management was also highlighted, with cooperatives and associations unable to deliver tangible benefits to their members. In addition, market prices have become more attractive than collective selling via association, corroborating Prosperi et al., who state that insertion in these support networks can generate lock-in problems, regarding the lack of openness and flexibility [

14]. It was also identified a lack of knowledge about the importance of associative/cooperativism for collective strengthening.

In addition to the producers' association, other actors emerge as a support network for rural producers in Ingaí - MG. The local agribusiness itself assists in the execution of operational and financial processes, in the organization of documents for requesting financing and providing training and qualifications. In addition, partnerships with startups and initiatives such as app development show dairy sector’s potential to help producers modernize and remain competitive.

“Given the diversity and complexity of milk production systems in the country, technical assistance plays a vital role in providing increased production and factor productivity, which enables the growth of the producer's income” [

28] (p.80). The role of Emater-MG technicians, IMA technicians and commercial representatives goes beyond simple marketing, offering technical support and production evaluations to local producers. The presence of Emater-MG and partnerships with financial cooperatives demonstrates a collective effort to overcome barriers to access to rural credit. Also, in relation to the support network, there is veterinarian support on some farms.

3.5. Property Management

Prosperi et al. emphasized the relevance of management in the transition process to a technological configuration [

14]. In Ingaí - MG, some of the elements related to property management mentioned by the interviewees were labor, female leadership, raising of production costs and family succession.

According to Meng, Zhao, Song & Lin, people play an indispensable role in the development of digital agriculture in a region, and the shortage of skilled personnel remains a challenge in this process [

8]. In Ingaí - MG, this scenario is evident, with the workforce being predominantly family-based, and there is difficulty finding people willing to work in the dairy sector. Although "the average salary of a retiree is around R

$4,500.00 per month, they still cannot find people willing to work," as one of the producers points out. In addition, the issue of employee training was addressed as a hindrance, since each property has its specificities, such as "the way to express milk, the place where the cow stays, how to give feed, water, etc". Bánkuti et al. in their study carried out with small producers in Paraná, identified that there is a tacit knowledge in the dairy activity that is irreplaceable, which can both be a source of benefits and better performance, as well as create a situation of imprisonment and dependence for the owners [

6].

According to technicians and extension workers, although there are many women in the field, in most properties they are not paid for production and female leadership is still incipient. Despite this, the commercial representatives pointed out that the growing role that women have assumed in the management of the property is notorious, helping their husbands in the adoption of technologies, execution of payments, purchases, controls and care with cleaning. In this way, the woman is no longer an assistant and is perceived as a producer, being responsible for initiating the decision-making process, while the man will carry out the validation. Thus, an opportunity found in Ingaí - MG is to improve female representation in the countryside, bringing women as a target audience for training and qualifications and creating job opportunities for them, such as the promotion of initiatives such as family agribusiness and rural tourism.

As for the raising of production costs, it was pointed out that most producers do not have these records in a formal way, and this, associated with the difficulties of managing the working capital of the milk producer, becomes a hindering factor. This is because, according to producers, although the costs of the activity remain daily, there are occasions when dairy products delay payment, and others pay less than agreed. "The cow doesn't stop eating because the dairy industry didn't pay me," reports one of the interviewees.

Family succession is a bottleneck in property management. Bánkuti et al. pointed out that the family decision on whether to remain in the dairy activity must consider material and immaterial elements, such as the characteristics of the farm, its structural aspects, its technical characteristics, the socioeconomic characteristics of the family, the degree of experience with the activity, the availability of labour, among others [

6].

In Ingaí, according to the interviewees, the income from agriculture is insufficient and, as a result, young people seek work and study opportunities in larger cities. In addition, young people realize the difficulties their parents face with agricultural activities. According to the producers, 'there is no substitute for the farmer.' The children see their parents' difficulties and say, 'This is not for me!'. Regarding family succession, when a producer has many children, the division of the rural property often leads to even lower profitability. Consequently, farms tend to transform into leisure sites.

According to local commercial representatives, when family succession occurs, some young people continue the activity in the same way their parents did (tradition), while others are more technologically advanced, have more information, and are more open to changes in the production process. More modern places are those with young people. (...) A property that has young people, they are looking to study more, to train, they are graduates in agronomy, animal science, veterinary. This results in more selected cattle, with a better genetic structure, a better-quality feed. (...) And parents accept it when they see that it works", say the commercial representatives.

3.6. Market Management

Small-scale communities need to be connected in networks that contain larger communities and that offer the necessary infrastructure not yet available in the municipality itself [

3], such as (1) transport networks (paths, roads, railways, canals, airways and others and the support networks – refuelling, sustenance, etc.); (2) ICT networks (cable networks, processing centres, software factories, etc); (3) Energy networks (fossil fuel, hydropower stations, solar farms, etc); (4) Finance systems (banks, investment firms, micro-finance networks, accountants, standards & compliance organisations, etc) (5) Protective networks (water, sanitation, drainage, solid waste management, etc.); (6) Societal support networks (healthcare, education, job exchanges, safety nets, etc.); (7) Ecological networks (watersheds, soil reclamation, forestry, grasslands, parks & reserves, etc.); (8) Community support networks (local government networks, police, law, food & provision networks, etc.); (9) Friends & family networks (sporting and interest networks, charity networks, beliefs, intentions, desires, dislikes and disapprovals, habits, ethics and cultures) [

3].

Ingaí - MG borders the municipality of Lavras - MG, which is its region of influence. The Lavras ecosystem, called Vale dos Ipês, has become a hub of innovation and entrepreneurship. It has a vocation for areas such as agribusiness, food and biotechnology, automation, information and communication technologies [

29]. According to Alvarenga, the scientific, technological, and educational potential is reflected in its four higher education institutions, which together offer 49 undergraduate courses, 31 master's degrees, and 21 doctoral degrees [

29]. The municipality also has a technology park – which hosts an incubator for technology-based companies and a center for innovation and entrepreneurship – and a startup factory focused exclusively on agribusiness [

29]. This support infrastructure is important, since the presence of universities, research centres, industry associations, technology support services and participation in other types of networks brings dynamism to the site and contributes to the innovative behaviour of those involved [

14], being analysed in this work as a potentiality for the transformation of Ingaí - MG into an Agrotechnological District.

Another potential of the municipality refers to the presence of large stakeholders in the milk market, who may be interested in the transfer of technology to producers, with a view to improving productivity and product quality. According to data from the Dairy Industry Union of the State of Minas Gerais, there are 226 associated dairies, of which 65 are within a radius of 200km from the city [

30]. In addition, the municipality is relatively close (275km) to Juiz de Fora, a city that is home to Embrapa Dairy Cattle, an important player in the development of dairy farming in the country.

Figure 3 shows the location of the dairy products in relation to Ingaí - MG.

The commercialization of the production of Ingaí - MG takes place directly with 3 cooperatives and 7 dairy industry factories that operate in the region, of which 3 are large and 2 medium-sized, with commercialization throughout the country. The existence of these major players is understood as an opportunity for the municipality, since they may be interested in assisting in the transfer of technology to the producer, since the improvement in productivity and quality of milk directly impacts the quality of the products offered by them.

A challenge pointed out by producers is related to the sale value of raw milk. The interviewees stated that the sale price of milk is low, and the production costs are high, due to investments in machinery. In addition, the market itself defines the price of milk, due to the quality and productivity premiums. There is a requirement that the dairy industry carry out a periodic analysis of the quality of the milk, which is carried out by sampling and this analysis will determine whether the producer will receive the quality award or not. Due to this quality test, the producer can receive a premium of R

$0.20 to R

$0.50 per liter. Although there is a minimum value for the sale of milk, due to this productivity premium, the producer cannot be sure about the value of the milk that will be received. With these price variations, there is a difficulty in producing and selling profitably, especially by small producers, due to the lower production volumes. Therefore, producers change dairy industry very easily, always going towards those who pay better. These results corroborate the considerations of Bánkuti et al., who pointed out that the volume of milk is an important variable in defining the price paid per liter and that those who produce more tend to have better economic efficiency, due to the economy of scale (dilution of fixed costs and reduction in unit costs of production) and, consequently, generate better income [

6].

In this context, the technification of production becomes an opportunity for producers to improve their production and, thus, achieve better prices for their product, since the adoption of technologies allows the improvement of milk quality.

An example of this application can be found in Rocha, Silva & Silveira, who advocate the implementation of blockchain technology in the milk supply chain in Brazil [

31]. They say that this technology has a positive impact on the quality of the milk, since, among other factors, it can offer support in the management of inputs, such as feed, vaccines and medicines, directly affecting the health and well-being of the animal. The authors complete by stating that this improvement benefits both the industry, since it receives the milk in better conditions, resulting in higher quality products, and for the producers who will receive a higher value for the milk supplied.

The incorporation of technologies in the production process involves investments, but in Ingaí - MG access to credit is still a barrier for milk producers. “Producers of other crops (for example, coffee, which they only receive during the harvest) have learned to work with credit, but the milk producer, he receives every month for production (because he produces every month), so he prefers to work with the resource he already has”. In this way, the producer often works with difficulties, afraid to look for a bank branch and contract a debt that compromises his income. Thus, stability is essential for the producer to decide to make a very large investment in technology.

In the city there are few family agribusinesses, which limits the opportunities to add value to local production and greater profitability. In this way, the promotion of initiatives such as the creation of family agribusinesses and rural ecotourism become opportunities for the more sustainable development of the municipality. These initiatives can make it possible to diversify the sources of family income (reducing dependence on dairy industry), generate income in a more distributed way, keep the rural population economically active, promote social inclusion, especially for women, and boost the local economy with new opportunities, respecting the natural resources present in the region. Additionally, they can help to preserve and enhance the cultural and natural heritage of the region, which can include traditions, typical cuisine, and sustainable farming practices. This appreciation not only attracts visitors but also strengthens the sense of local identity and the pride of belonging to the community.

4. Discussion

The results of this study are in line with the findings of Bonamigo, Ferenhof, & Forcellini, who made a diagnosis of milk production in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil [

24]. The authors identified 19 bottlenecks that are limiting to milk production, within four main constructs: the lack of cooperation between local actors; the deficiency in milk quality; the rural exodus; and productivity limitations [

24]. They indicate that cooperation between local ecosystem actors allow support for the development or financing for the adoption of technologies and/or better agricultural practices [

24]. Regarding the rural exodus, it was pointed out that young people in Santa Catarina go to urban centers in search of better living conditions (study, employment, increase in income) and hardly return to the countryside, in the same way as in Ingaí – MG [

24].

Regarding the quality of milk, in Santa Catarina the price of the product is also associated with its quality, with the producer being the most vulnerable link in the chain. Finally, regarding the limitation of productivity, the authors suggest an agenda that encourages the adoption of technologies and best practices that promote the efficiency on the property.

Overcoming these challenges requires an approach not only to technological and structural issues, but also to socioeconomic and cultural aspects. The engagement of producers, government support and partnerships between local institutions can boost the sustainable development of the agricultural sector in Ingaí - MG, encouraging innovation, training and the search for solutions that promote the well-being of the agricultural community.

Meng, Zhao, Song & Lin point out that the development of digital agriculture is a gradual process and influenced by many factors. Thus, they present a series of recommendations to improve the level of development of digital agriculture, considering the real conditions of each location, such as improving public policies related to digital agriculture, improving the development of local infrastructure and developing people so that they can work in digital agriculture (investments in training and qualification) [

8]. Gumbi, Gumbi & Twinomurinzi point out that there is a limitation in research directed to literacy or digital skills, accessibility and innovation of the business model focused on digital agriculture [

9]. Therefore, some opportunities for the digital transformation of Ingaí - MG are the strengthening of support networks, the increase in the technification of producers, training and rural extension and the growth potential of the rural community in the municipality, through the promotion of the creation of family agro-industries and rural tourism.

Finally, as reported by representatives of the local agribusiness, "the dairy basin in Ingaí will not be exhausted. It will change. But the little ones who do not become technified, will be impacted and will be swallowed up.” The creation of an agrotechnological district in Ingaí - MG can be a strategic solution to face the challenges in dairy production. By promoting partnerships between dairy industries, cooperatives and agribusinesses, the ATD strengthens support networks, reducing the vulnerability of smallholders. The technological infrastructure and training programs would facilitate the adoption of more efficient practices, raising the quality and profitability of milk. In addition, by giving women a voice, retaining young people in the countryside, and encouraging innovation, the ATD would contribute to sustainable socioeconomic development, making the local dairy basin more resilient and competitive.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 demonstrate the opportunities and challenges for the transformation of Ingaí into an ATD, related to the categories: Socioeconomic characteristics of the municipality; Producers' level of technification; the local connectivity infrastructure; the existing support networks; property management; and market management.

5. Final Considerations

This study aimed to identify difficulties and opportunities for the transformation of Ingaí-MG into an agro-technological district, using semi-structured group interviews as a source of data collection. The results allowed the identification of information about the municipality and offer insights for decision-making on how the strategy of its transformation into an Agrotechnological District will be.

In Ingaí - MG, socioeconomic development is linked to overcoming the limitations of technification, access to credit, connectivity infrastructure, management and succession of properties and access to support networks. There is a potential for growth in the rural community of the municipality, based on the collaboration between the various actors involved, aiming at the implementation of solutions that promote digital inclusion, improve local infrastructure and strengthen support networks for family farmers. The importance of rural extension actions is highlighted, offering training and qualification aimed at the adoption of technologies, property management, and the creation of new markets. These actions will enable the development of sustainable agriculture in the region, as they promote increased production efficiency, optimization of the use of natural resources, and reduction of waste.

Finally, the transformation of Ingaí into an Agrotechnological District will allow dairy farmers to monitor herd performance, improve milk quality, and reduce operating costs. In addition, digital inclusion will facilitate access to market data and information, opening new opportunities for marketing and adding value to local products. By strengthening support networks and continuous training, it will be possible to increase the competitiveness and resilience of small properties, promoting a cycle of sustainable regional development that will benefit the rural community, especially the new generations of producers.

In this sense, public policies to support agricultural activity are necessary. Municipal and state governments can act to improve connectivity infrastructure, such as financing the installation and maintenance of internet and mobile phone antennas and collaborating in discussions on the most suitable locations for installation. At the federal level, the government could contribute to access to credit for small and medium-sized farmers, via public banks, to boost activity. Universities and development agencies can train farmers to use digital technologies, both in production and in property management, emphasizing financial education, to stimulate the viability of small and medium-sized enterprises.

This exploratory study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the qualitative nature of the group interviews, although rich in details and insights, may not capture all the relevant variables or completely generalize the realities faced by dairy farmers in Ingaí - MG. In addition, the focus on a single municipality limits the applicability of the findings to other regions with different socioeconomic, cultural, and structural contexts. The absence of quantitative data also prevents a more in-depth analysis of the correlations between the identified factors and the socioeconomic performance of producers. Finally, the influence of external factors, such as public policies and changes in the global dairy market, was not fully considered, which may impact the sustainability of the proposed solutions.

An additional limitation of this study is the exclusive focus on milk production, influenced by the scope of the SEMEAR Digital project in the locality of Ingaí - MG. Although milk is a relevant agricultural activity, other activities also play a significant role in the rural economy of the region and have not been explored. This concentration in a single sector may have left aside opportunities and challenges present in other agricultural areas, limiting the scope of the conclusions and recommendations offered by the study.

As a research agenda, future studies can address the limitations mentioned above, such as: considering other production chains in the analysis of the construction of an ATD, seeking a larger sample, via the number of interviews and/or covering other municipalities, in order to test hypotheses with quantitative methods; examine the municipalities that are candidates for ATDs in the institutional context, in order to cover sectoral industrial policies, especially those related to the dairy market, macroeconomic and international, referring to the foreign trade of such products. Such suggestions are proposed for the continuity of future work in the context of the theme addressed here.