Submitted:

30 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rural Development Projects Based on the Working with People Model

1.2. Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) of the Committee on World Food Security

1.3. Research Questions

- How do the CFS-RAI principles contribute to sustainable rural development in different international contexts?

- How can the CFS-RAI principles be integrated into the Working with People (WWP) model to contribute to sustainable rural development?

- How do university-business relationships influence rural actors' understanding and adoption of the CFS-RAI principles?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Working with People Model

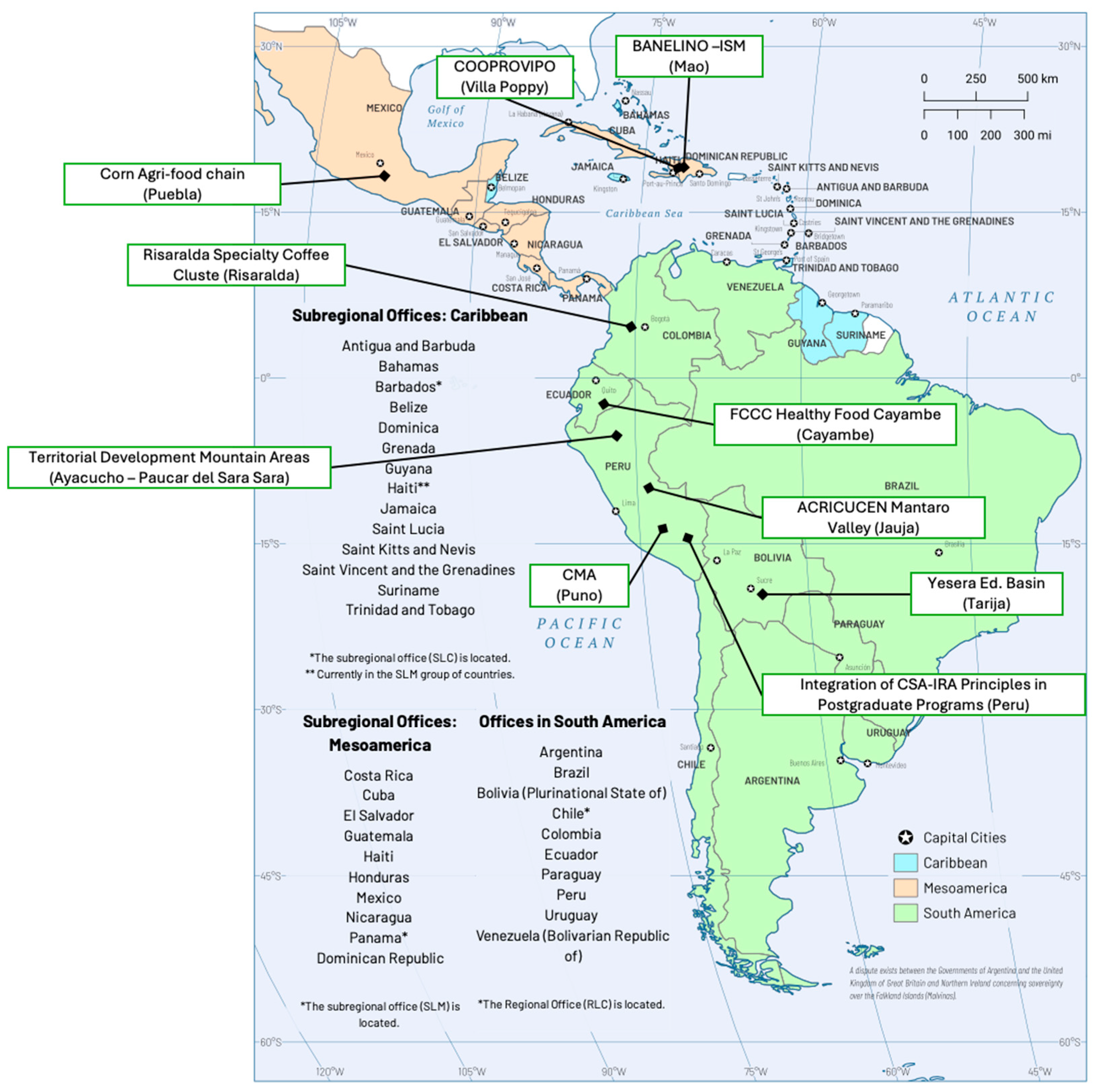

2.2. Case Studies

2.3. Data Collection: Instruments and Processes

2.3.1. Participatory Process: Conferences, Workshops, and Seminars

2.3.2. Survey of Project Leaders

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Contribution of the CFS-RAI Principles to Sustainable Development in the Territories

3.2. Actions from the Political–Contextual Dimension: P5, P6 P9 y P10

3.3. Actions from the Ethical-Social Dimension: P1, P3, P4 y P7

3.4. Actions from the Technical-Entrepreneurial Dimension: P2 y P8

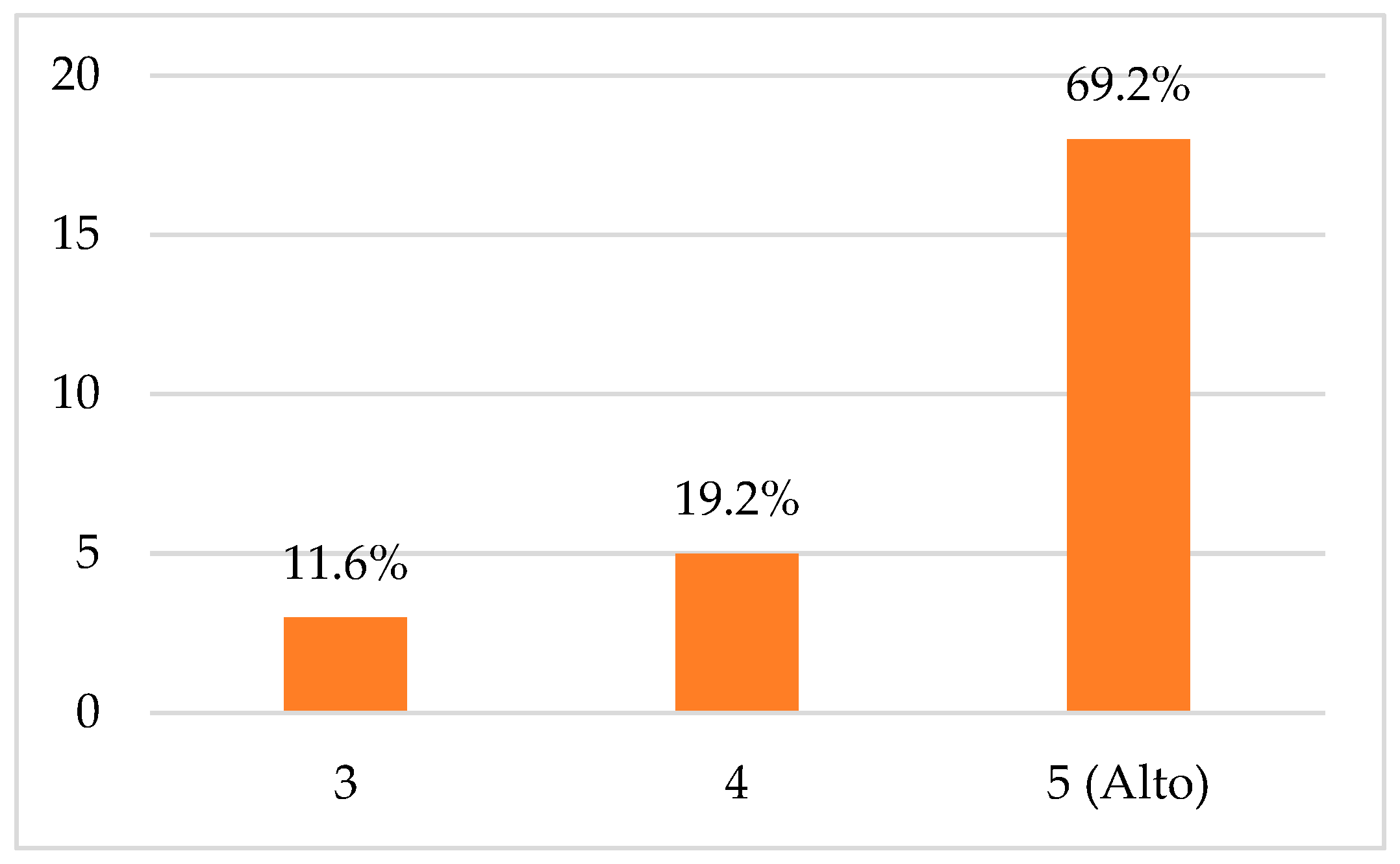

3.5. Social Learning Through University-Business Relationships

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrukh, M.; Meng, F.; Raza, A.; Tahir, M.S. Twenty-Seven Years of Sustainable Development Journal: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1725–1737. [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our common future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Hajian, M.; Kashani, S.J. Evolution of the Concept of Sustainability. From Brundtland Report to Sustainable Development Goals. In Sustainable Resource Management: Modern Approaches and Contexts; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Sustainability and Sustainable Development Research around the World. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2022, 20. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, I.; Ateljević, J.; Stević, R.S. Good governance as a tool of sustainable development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwolinska-Ligaj, M. The “Smart Village” as Away to Achieve Sustainable Development in Rural Areas of Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6503. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Appiah, D.; Zulu, B.; Adu-Poku, K.A. Integrating Rural Development, Education, and Management: Challenges and Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6474. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, C.; Song, W. Bibliometric Analysis in the Field of Rural Revitalization: Current Status, Progress, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 823. [CrossRef]

- Kumareswaran, K.; Jayasinghe, G.Y. Systematic Review on Ensuring the Global Food Security and Covid-19 Pandemic Resilient Food Systems: Towards Accomplishing Sustainable Development Goals Targets. Discov. Sustain. 2022, 3, 29. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.T.; McConnell, K.; Berne Burow, P.; Pofahl, K.; Merdjanoff, A.A.; Farrell, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Rural America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Reflections on China’s Food Security and Land Use Policy under Rapid Urbanization. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105699. [CrossRef]

- Obi, C.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G.; D’Haese, M. How Does International Migration Impact on Rural Areas in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 273–290. [CrossRef]

- Busso, M.; Chauvin, J.P.; Herrera L., N. Rural-Urban Migration at High Urbanization Levels. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103658. [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of Rural–Urban Migration on Agricultural Transformation: A Case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [CrossRef]

- Wolford, W.W.; White, B.; Scoones, I.; Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M. Global Land Deals: What Has Been Done, What Has Changed, and What’s Next? J. Peasant Stud. 2024, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Mansilla-Quiñones, P.; Uribe-Sierra, S.E. Rural Shrinkage: Depopulation and Land Grabbing in Chilean Patagonia. Land 2024, 13, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J. Global Land Grabbing: A Critical Review of Case Studies across the World. Land 2021, 10, 324. [CrossRef]

- Burja, V.; Tamas-Szora, A.; Dobra, I.B. Land Concentration, Land Grabbing and Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2137. [CrossRef]

- Yeshanew, S. Rights in the Collaboration between the World Bank and the United Nations in the Areas of Investment in Agriculture, Rural Development and Food Systems. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2023, 27, 1086–1106. [CrossRef]

- Mingst, K.A.; Karns, M.P.; Lyon, A.J. The United Nations in the 21st Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2022.

- Committee on World Food Security (CFS). Principles for responsible investment in agriculture and food systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/au866e/au866e.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the Sustainable Development Goals towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Morioka, S.N.; Sznelwar, L.I. Are We Making Decisions in a Sustainable Way? A Comprehensive Literature Review about Rationalities for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 310–322. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I. Towards a Meta-University for Sustainable Development: Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems; In Proceedings of the XXVIII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Jaén, Spain, 3–4 July 2024; pp. 1959–1973. Available online: https://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/3691 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- GESPLAN. Principios CSA-IRA: Inversión Responsable En Agricultura y Sistemas Alimentarios En La Universidad y La Empresa. Available online: https://ruraldevelopment.es/index.php/es/docencia-lms/principios-iar-universidad (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I. From “Putting the Last First” to “Working with People” in Rural Development Planning: A Bibliometric Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10117. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning as Social Learning; IURD Working Paper Series; Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1981.

- Pieterse, J.N. My Paradigm or Yours? Alternative Development, Post-Development, Reflexive Development. Dev. Change 1998, 29, 343–373. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. The LEADER Community Initiative as Rural Development Model: Application in the Capital Region of Spain. Agrociencia 2005, 39, 697–708.

- De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; María Díaz-Puente, J. Creación de grupos de acción local para el desarrollo rural en México: Enfoque metodológico y lecciones de experiencia. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 815–829. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-31952011000700007 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Dax, T.; Oedl-Wieser, T. Rural Innovation Activities as a Means for Changing Development Perspectives - An Assessment of More than Two Decades of Promoting LEADER Initiatives across the European Union. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Suárez Roldan, C.; Méndez Giraldo, G.A.; López Santana, E. Sustainable Development in Rural Territories within the Last Decade: A Review of the State of the Art. Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W.; Dirix, J.; Sterckx, S. Putting Sustainability into Sustainable Human Development. J. Human Dev. Capab. 2013, 14, 58–76. [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing Nature’s Contributions to People: The IPBES Approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hull, V.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Tilman, D.; Gleick, P.; Hoff, H.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Xu, Z.; Chung, M.G.; Sun, J.; et al. Nexus Approaches to Global Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 466–476. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De Los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in Rural Development Projects: A Proposal from Social Learning. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. Available online: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/desarrolloRural/article/view/6717 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Cazorla, A.; Friedmann, J. Planificación e Ingeniería: Nuevas Tendencias; Taller de ideas, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Spain, 1995.

- Holden, M. Social Learning in Planning: Seattle’s Sustainable Development Codebooks. Prog. Plann. 2008, 69, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N. Paraprojects as New Modes of International Development Assistance. World Dev. 1990, 18, 1401–1411. [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Chambers, R. Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Challenges, Potentials and Paradigm. World Dev. 1994, 22, 1437–1454. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falero, E.; Trueba, I.; Cazorla, A.; Alier, J.L. Optimization of Spatial Allocation of Agricultural Activities. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1998, 69, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme, and Portfolio Management, Version 4.0; International Project Management Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.ipma-greece.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IPMA_ICB_4_0_WEB.pdf (accessed on January 2025).

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Ortuño, M.; Rivera, M. Private–Public Partnership as a Tool to Promote Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development: WWP Torrearte Experience. Sustainability 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E.; Aliaga Balbín, H.; Marroquín Heros, A.M. Competencies and Capabilities for the Management of Sustainable Rural Development Projects in the Value Chain: Perception from Small and Medium-Sized Business Agents in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15580. [CrossRef]

- Stratta Fernández, R.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; López González, M. Developing Competencies for Rural Development Project Management through Local Action Groups: The Punta Indio (Argentina) Experience. In International Development; Appiah-Opoku, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia. [CrossRef]

- Sastre Merino, S.; De los Ríos, I. Capacity Building in Development Projects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 960–967. [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Cazorla, A.; Panta, M. del P. Rural Entrepreneurship Strategies: Empirical Experience in the Northern Sub-Plateau of Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Reyes, A.T.; Carmenado, I. de los R.; Martínez-Almela, J. Project-Based Governance Framework for an Agri-Food Cooperative. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1881. [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; Strauss, A.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Rios, I. des I.; Rivera, M.; Chebach, T.; Ashkenazy, A. Local and Farmers’ Knowledge Matters! How Integrating Informal and Formal Knowledge Enhances Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; Negrillo, X.; Montalvo, V.; De Nicolas, V.L. Institutional Structuralism as a Process to Achieve Social Development: Aymara Women’s Community Project Based on the Working with People Model in Peru. J.Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2018, 45, 55.

- Fontana, A.; Sastre-Merino, S.; Baca, M. The Territorial Dimension: The Component of Business Strategy That Prevents the Generation of Social Conflicts. J. of Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 367–380. [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.P.; De los Ríos, I.; López, M. Management of Innovative and Entrepreneurship Projects from Project-Based Learning: A Case Study on the UPS University in Ecuador. In Case Study of Innovative Projects.Successful Real Cases; Llamas, B., Mazadiego, F., Storch, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ávila Cerón, C.A.; De los Rios-Carmenado, I.; Martín Fernández, S. Illicit Crops Substitution and Rural Prosperity in Armed Conflict Areas: A Conceptual Proposal Based on the Working with People Model in Colombia. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Bugueño, F.; De, I.; Ríos, L.; Castañeda, R. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues Responsible Land Governance and Project Management Competences for Sustainable Social Development. The Chilean-Mapuche Conflict. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 202–211.

- Fontana, A.; Velasquez-Fernandez, A.; Rodriguez-Vasquez, M.I.; Cuervo-Guerrero, G. Territorial Analysis Through the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles and the Working with People Model: An Application in the Andean Highlands of Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1380. [CrossRef]

- Acosta Mereles, M.L.; Mur Nuño, C.; Stratta Fernández, R.R.; Chenet, M.E. Good Practices of Food Banks in Spain: Contribution to Sustainable Development from the CFS-RAI Principles. Sustainability 2025, 17, 912. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín Howard, F.; Calle Espinoza, S.; Huamán Cristóbal, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [CrossRef]

- Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. [CrossRef]

- Negrillo Deza, X. Los Proyectos de Desarrollo Rural Como Proceso a Través de Sus Protagonistas: El Caso de La Coordinadora de Mujeres Aymaras (Puno, Perú). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2018. Available online: (accessed on 26 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kutsenko, M. Application of the Project Approach as Part of the Territory Development Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computer Sciences and Information Technologies (CSIT);, Zakharkiv, Ukraine, September 2021; Volume. 2, pp. 375–378. [CrossRef]

- Musawir, A. ul; Abd-Karim, S.B.; Mohd-Danuri, M.S. Project Governance and Its Role in Enabling Organizational Strategy Implementation: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2020, 38, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Chen, W.; Quazi, A.; Parry, W.; Wong, A.; Poon, S.K. The Relationship between Project Governance Mechanisms and Project Success: An International Data Set. Int. J. Manag. Proj.Bus. 2020, 13, 1496–1521. [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L.G.; Kanemasu, Y. Sustainable Development and Policies in Rural Regions; Insights from the Shetland Islands. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 310–321. [CrossRef]

- Ávila Cerón, C.A.; Castañeda, R.; De Los Ríos, I. Development of a Family Agriculture Model Aligned with the Principles of Responsible Investment: Integration Tourism Chain in the Dominican Republic. In Proceedings of the XXVIII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering (AEIPRO 2024), Jaén, Spain, 3–4 July 2024; pp. 1974–1987. Available online: 2024; http://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/3692 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J. La iniciativa LEADER como modelo de desarrollo rural: aplicación a algunos territorios de México. Agrociencia 2011, 45 (5), 609–624.

- Olvera Hernández, J.I.; Cazorla Montero, A.; Ramírez Valverde, B. La Política de Desarrollo Rural En La Unión Europea y La Iniciativa LEADER, Una Experiencia de Éxito. Región y sociedad 2009, 21, 03–25.

- Navarro Valverde, F.A.; Cejudo García, E.; Cañete Pérez, J.A. A long-run analysis of neoendogenous rural development policies: the persistence of businesses created with the support of LEADER and PRODER in three districts of Andalusia (Spain) in the 1990s. AGER. Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 2018, 25, 189–219.

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Afonso, A. Principles for a Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land: Links with University; Working Paper; GESPLAN Group, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/50898/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Morris, L.; Salazar, O.; Garmendia, J. Characterization of the Technical Operations to Strengthen the Logistics Processes of the Cluster of Specialty Coffees of Risaralda. In Proceedings of the XXVII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, San Sebastián, Spain, 10–13 July 2023; pp. 2382–2392. Available online: https://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/3532 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Cachipuendo, C.; Requelme, N.; Sandoval, C.; Afonso, A. Sustainable Rural Development Based on CFS-RAI Principles in the Production of Healthy Food: The Case of the Kayambi People (Ecuador). Sustainable Rural Development Based on CFS-RAI Principles in the Production of Healthy Food: The Case of the Kayambi People (Ecuador). Sustainability 2025, 17, 2958. [CrossRef]

- Regalado-López, J.; Maimone-Celorio, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, N. Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5442. [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Merino, S.; Negrillo, X.; Hernández-Castellano, D. Sustainability of Rural Development Projects within the Working with People Model: Application to Aymara Women Communities in the Puno Region, Peru. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2013, 10 (70), 219–244. [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Cazorla, A.; Gandini, G.; Eberth, E. Los Principios CSA-IRA para una Integración Universidad-Empresa en las Provincias de Santiago Rodríguez, Valverde (Mao), Dajabón y en República Dominicana; Working Paper; GESPLAN Group, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017.

- Cazorla A; De los Ríos, I. Towards a Meta-University for Sustainable Development: Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems. In Proceedings of the XXVIII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering (AEIPRO 2024), Jaén, Spain, 3–4 July 2024; pp. 1959–1973. Available online: https://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/3691 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Teucher, M.; Thürkow, D.; Alb, P.; Conrad, C. Digital In Situ Data Collection in Earth Observation, Monitoring and Agriculture—Progress towards Digital Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 393. [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.E.; Ewbank, D. The Focus Group as a Tool for Health Research: Issues in Design and Analysis. Health Transit. Rev. 1994, 4(1), 63–80. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652078 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Rabiee, F. Focus-Group Interview and Data Analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [CrossRef]

- South, L.; Saffo, D.; Vitek, O.; Dunne, C.; Borkin, M.A. Effective Use of Likert Scales in Visualization Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Comput. Graph. Forum 2022, 41, 43–55. [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch.s of Psychol. 1932, 22(140), 1–55.

- Cazorla, A.; Negrillo, X.; Montalvo, V.; De Nicolas, V.L. Institutional Structuralism as a Process to Achieve Social Development: Aymara Women’s Community Project Based on the Working with People Model in Peru. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2018, 45, 55–78.

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Visconti-Lopez, F.J.; Vargas-Fernández, R. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 13 Countries. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3190. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Mendiratta, V.; Savastano, S. Agricultural and Rural Development Interventions and Poverty Reduction: Global Evidence from 16 Impact Assessment Studies. Glob. Food Sec. 2024, 43, 100806. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Shuai, C.; Yin, C.; Qi, H.; Chen, X. Progress toward SDG-2: Assessing Food Security in 93 Countries with a Multidimensional Indicator System. Sustainable Development 2024, 32, 815–862. [CrossRef]

- Woodhill, J.; Kishore, A.; Njuki, J.; Jones, K.; Hasnain, S. Food Systems and Rural Wellbeing: Challenges and Opportunities. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1099–1121. [CrossRef]

- Trivelli, C.; Morel, J. Rural Youth Inclusion, Empowerment, and Participation. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 635–649. [CrossRef]

- Leakey, R.R.B.; Tientcheu Avana, M.-L.; Awazi, N.P.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Hendre, P.S.; Degrande, A.; Hlahla, S.; Manda, L. The Future of Food: Domestication and Commercialization of Indigenous Food Crops in Africa over the Third Decade (2012–2021). Sustainability 2022, 14, 2355. [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Hlahla, S.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Henriksson, R.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Groner, V.P.; Tadele, Z.; Sobratee, N.; Slotow, R.; et al. Diversity and Diversification: Ecosystem Services Derived from Underutilized Crops and Their Co-Benefits for Sustainable Agricultural Landscapes and Resilient Food Systems in Africa. Front. Agron. 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, R.; Cerón, C.A.; los Ríos-Carmenado, I. De; Domínguez, L.; Gomez, S. Implementing the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests from the Working with People Model: Lessons from Colombia and Guatemala. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 1820–1851. [CrossRef]

- Gargano, G. The Bottom-Up Development Model as a Governance Instrument for the Rural Areas. The Cases of Four Local Action Groups (LAGs) in the United Kingdom and in Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9123. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, E.; Fosselle, S.; Rogge, E.; Home, R. An Analytical Framework to Study Multi-Actor Partnerships Engaged in Interactive Innovation Processes in the Agriculture, Forestry, and Rural Development Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6428. [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, T.; Alessio, C.; Chiara, A.; Gigliola, P.; Concetta, F.; Federica, B.; Paolo, P. Civic Universities and Bottom-up Approaches to Boost Local Development of Rural Areas: The Case of the University of Macerata. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 15. [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.P.; Yarime, M.; Kharrazi, A. Co-Creating Sustainability: Cross-Sector University Collaborations for Driving Sustainable Urban Transformations. J. Clean Prod. 2013, 50, 40–55. [CrossRef]

- Atterton, J.; Thompson, N. University Engagement in Rural Development: A Case Study of the Northern Rural Network. J. Rural Community Dev. 2010, 5, 123–132. Available online: https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/338/78 (accessed on July 2025).

- Almeida, F. The Role of Partnerships in Municipal Sustainable Development in Portugal. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2024, 16, 231–244. [CrossRef]

- Midgley, J.O. Social Development : Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; p. 296.

- Ortega, R.; Cazorla, A. The International Cooperation for Development Based on Easterly and Sachs: The Institutional Structuralism as the Pathway to the Future. In Proceedings of the XXIV International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Alcoi, Spain, 7–10 July 2020; pp. 1693–1076. Available online: http://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/2538 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- De los Ríos, I.; García, C.; Herrera, A.T.; Rivera, M. Innovation and Social Learning in Organic Vegetable Production in the Region of Murcia, Camposeven, Spain. RETHINK Case Study Report. GESPLAN, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain 2015.

- López-García, D.; Carrascosa-García, M. Agroecology-Oriented Farmers’ Groups. A Missing Level in the Construction of Agroecology-Based Local Agri-Food Systems? Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 47, 996–1022. [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Mur Nuño, C. Inclusive and Transparent Governance Structures from IRA Principles. Case FESBAL “Food Bank”. In Proceedings of the XXVII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering (AEIPRO 2023), Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 10–13 July 2023; pp. 1737–1751. Available online: http://dspace.aeipro.com/xmlui/handle/123456789/3486 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Nordberg, K.; Mariussen, Å.; Virkkala, S. Community-Driven Social Innovation and Quadruple Helix Coordination in Rural Development. Case Study on LEADER Group Aktion Österbotten. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- De los Rios-Carmenado, I.; Rahoveanu, A.T.; Salvo, M.; Rodriguez, P. Territorial Competitiveness for Rural Development in Romania: Analysis of Critical Influential Factors from WWP Model. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium “Agrarian Economy and Rural Development—Realities and Perspectives for Romania”, Bucharest, Romania, October 2012; The Research Institute for Agricultural Economy and Rural Development (ICEADR): Bucharest, Romania, 2012; pp. 89–94.

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Acosta Mereles, M.L.; Farías Estrada, I.J.; Nole Correa, P.; Zuluaga Zuluaga, C.L.; Mur Nuño, C.; Peral, C.; García Gutiérrez, J. Los Principios de Inversión Responsable en la agricultura y los sistemas alimentarios desde el Proyecto la Gran Recogida de la Federación Española de Bancos de Alimentos. In Experiencias de Aprendizaje-Servicio en la UPM: 2024; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Oficina de Aprendizaje-Servicio: Madrid, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/88689/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Friedmann, J. Insurgencies: Essays in Planning Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2011.

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder Participation for Environmental Management: A Literature Review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999.

- Leeuwis, C.; Pyburn, R.; Röling, N.G. (Eds.) Wheelbarrows Full of Frogs: Social Learning in Rural Resource Management—International Research and Reflections; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2002.

- del Arco, I.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Zsembinszki, G.; de Gracia, A.; Cabeza, L.F. Implementing SDGs to a Sustainable Rural Village Development from Community Empowerment: Linking Energy, Education, Innovation, and Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12946. [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a Solution to Extreme Poverty: A Review and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Abbas, J.; Ullah, R.; Abbas, A.; Sadiq, I.; Zhang, R. Women’s Entrepreneurial Contribution to Family Income: Innovative Technologies Promote Females’ Entrepreneurship Amid COVID-19 Crisis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; de Coninck, H.; Sagar, A.D. Beyond Technology Transfer: Innovation Cooperation to Advance Sustainable Development in Developing Countries. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Knickel, K.; Brunori, G.; Rand, S.; Proost, J. Towards a Better Conceptual Framework for Innovation Processes in Agriculture and Rural Development: From Linear Models to Systemic Approaches. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2009, 15, 131–146. [CrossRef]

- Mapiye, O.; Makombe, G.; Molotsi, A.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Towards a Revolutionized Agricultural Extension System for the Sustainability of Smallholder Livestock Production in Developing Countries: The Potential Role of Icts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5868. [CrossRef]

| Country | Case Studies / Key Topics | Sources |

| Spain | FESBAL-Food Banks: best practices in reducing food waste and responsible consumption | [59]. |

| Bolivia (Tarija-Cercado) |

Yesera Educational Basin: Sustainable water resource management by local communities, linking research and local knowledge. | [71]. |

| Colombia (Risaralda) |

Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster: Optimizing the cluster's logistics, strengthening business capabilities. | [72]. |

| Ecuador (Pichincha-Cayambe) |

FCCC Healthy Food Cayambe: Cooperation and microcredit for rural women for sustainable food production and marketing. | [73]. |

| Mexico (Puebla) |

Corn Agri-food chain: Comprehensive improvement of the corn agri-food chain in rural communities, strengthening partnerships for the application of CFS-RAI principles. | [74]. |

| Peru (Junín -Jauja) | ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley: Formation of the GAL partnership for sustainable practices, innovation, and improvement of the guinea pig value chain. | [47,60]. |

| Peru (Puno) |

CMA - Aymara Women Artisans: skills development, production, and marketing of sustainable artisanal textiles. | [62,75]. |

| Peru (Ayacucho – Paucar del Sara Sara) | Territorial development in mountain areas: Territorial model for optimizing resource allocation for sustainable development in mountain areas. | [58]. |

| Peru (three ecosystems) |

Integration of CFS-RAI Principles into Postgraduate Programs: in three ecosystems in Peru: the coast, the Andes, and the Amazon rainforest | [71]. |

| Dominican Republic (La Vega-Constanza) | Villa Poppy–Family Farming: Family Farming System in accordance with CFS-RAI Principles: sustainable practices and partnerships with tourism | [67]. |

| Dominican Republic (Santiago Rodríguez, Valverde, Dajabón) | University-Business Alliance UTESA, BANELINO, ISM: for Sustainable Territorial Development through CSA-IRA Principles: family social responsibility program with entrepreneurship. | [76]. |

| Year | Event | Location |

| 2016 | Good Business Practices from the CFS-RAI | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid |

| 2017 | The CFS-RAI Principles as a driver for Sustainable Economic Development: New University-Business Partnerships. | Escuela de Alta Dirección de la Universidad de Piura, Peru. |

| 2018 | I CFS-RAI Network Meeting for the dissemination of CFS-RAI. | Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Peru. |

| 2019 | Consolidation of CFS-RAI commitments in university curriculum. | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid. |

| 2020 | Towards consistent business conduct based on the CFS-RAI Principles. | Virtual 11 countries in the Network. |

| 2021 | I International academic/business program: “The principles of responsible investment in agriculture and food systems.” | Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra, Dominican Republic. |

| 2022 | II Meeting of the Network of Universities Committed to the Dissemination of the IRA Principles, RU-IRA. | Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra, Dominican Republic. |

| 2023 | Seminar of the RU-RAI Network of Universities and Companies. | Universidad Nacional de la Plata (UNLP) La Plata, Argentina. |

| 2024 | III Meeting Towards a meta-university for sustainable development: Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems. | UNICARIBE – Santo Domingo, República Dominicana. |

| 2024 | III International Business Program on CFS-RAI Principles in collaboration with FAO | Virtual |

| 2025 | Meeting: Keys to good governance in agri-food cooperatives in Latin America and the Caribbean: Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems | UNICARIBE – Santo Domingo, República Dominicana |

| CFS-RAI Principles | Dimensions WWP 1 | ||

| P-C | E-S | T-E | |

| P1. Contribute to food security and nutrition | X | ||

| P2. Contribute to economic development and poverty eradication | X | ||

| P3. Promote gender equality and women’s empowerment | X | ||

| P4. Enhance the participation and empowerment of young people | X | ||

| P5. Respect tenure of land, fisheries, forests and access to water | X | ||

| P6. Conserve and sustainably manage natural resources, increase resilience and reduce disaster risks | X | ||

| P7. Respect cultural heritage and traditional knowledge, and support diversity and innovation | X | ||

| P8. Promote safe and healthy agricultural and food systems | X | ||

| P9. Incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes and grievance mechanisms | X | ||

| P10. Evaluate and address impacts and promote accountability | X | ||

| Case Studies | CFS-RAI Principles1 | |||||||||

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | |

| FESBAL-Food Banks(Spain) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Yesera Educational Basin(Bolivia) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster(Colombia) | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Healthy Food: Cayambe (Ecuador) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley (Peru) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| CMAAymara Women Artisans(Peru) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Territorial development in mountain areas (Peru) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Integration of CSA-IRA Principles in Postgraduate Programs (Peru) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Villa Poppy – Family Farming (República Dominicana) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| University–Business Alliance UPM-UTESA–BANELINO–ISM (República Dominicana) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| General total | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

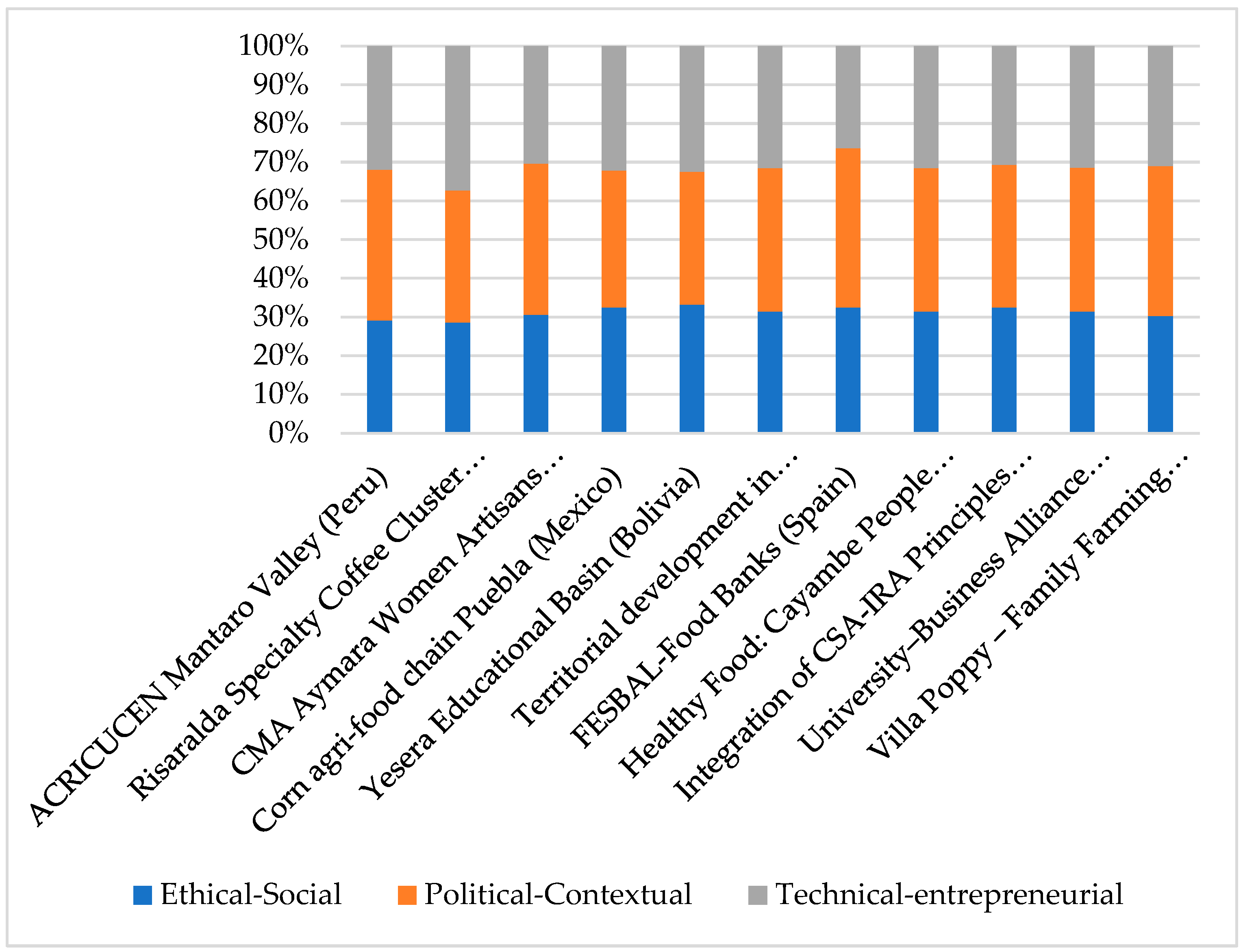

| Dimensions WWP | CFS-RAI | Importance of actions |

| Political-Contextual | P5, P6, P9 y P10 | 34.87% |

| Ethical-Social | P1, P3, P4 y P7 | 32.60% |

| Technical-Entrepreneurial | P2 y P8 | 32.53% |

| Total | 100.00% |

| Political-Contextual | 34.72% |

| University-Business Agreements | 6.41% |

| Partnerships for cooperation between agents | 6.25% |

| Creation of new local-regional governance structures | 6.04% |

| Legal formalization of associations and cooperatives | 5.80% |

| Participation in national and international networks | 5.18% |

| Monitoring, evaluation, and accountability system | 5.03% |

| Case study | Businesses - Associations | University |

| FESBAL-Food Banks (Spain). | Spanish Federation of Food Banks (FESBAL), 54 Food Banks. | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, UPM. |

| Yesera Educational Basin (Bolivia) | Associations of women producers of strawberries, peaches, and fish farming. |

Universidad Autónoma Juan Misael Saracho. |

| Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster (Colombia). | Cluster of 46 companies, 13 farmers' associations. | Universidad Católica de Pereira - Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. |

| Healthy Food Cayambe People (Ecuador). | Cayambe Peasant House Foundation Association of Agroecological Producers. International Cooperation for Development (ICD). |

Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, UPS. |

| Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico). | Guardians of Calpan Knowledge and Flavors Cooperative, Local Action Group. | Colegio de Postgraduados, COLPOS. |

| ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley (Peru). | Local Action Group. Association of producers, agricultural suppliers, and collectors. | Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, UNMSM. |

| CMA Aymara Women Artisans (Peru). | Coordinator of Aymara Women, NGO Design for Development. | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, UPM. |

| Territorial development in mountain areas (Peru). | Producers' associations, mining companies in Ayacucho and Paucar del Sara Sara. | Universidad de Piura. |

| Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Postgraduate Programs (Peru). | APECAM, Association of Organic Coffee Producers of Alto Mayo. Inter-American Development Bank. |

Universidad Católica Sedes Sapientiae, UCSS. |

| Villa Poppy – Family Farming (Dominican Republic). | COOPROVIPO, Neighborhood Council, FAO, ASONAHORES (National Association of Hotels and Restaurants), Grupo Raya, SuperFrech. | Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, UPM. |

| University–Business Alliance UTESA–BANELINO–ISM (Dominican Republic). | Industrias San Miguel (ISM) Northwest Organic Banana Association (BANELINO). |

Universidad Tecnológica de Santiago, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. |

| Ethical-Social | 32.66% |

| Skills and capacity building | 7.05% |

| Awareness-raising and training processes | 6.90% |

| Mechanisms for active and inclusive participation | 6.53% |

| Promotion of cultural identity and traditional knowledge | 6.35% |

| Partnership building / LAG | 5.83% |

| Technical-Entrepreneurial | 32.62% |

| Transformation and innovation to generate value for products | 6.58% |

| Marketing and access to differentiated markets | 6.51% |

| Logistics management and optimization of production systems | 6.46% |

| Standardized production systems and product quality, product certification | 6.54% |

| Digitization and improvement of production processes | 6.53% |

| Case Studies | Number of Beneficiaries |

| FESBAL-Food Banks (Spain) | 1,187,976 |

| Yesera Educational Basin (Bolivia) | 589 |

| Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster (Colombia) | 19,163 |

| Healthy Food Cayambe People (Ecuador) | 129 |

| Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico) | 800 |

| ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley (Peru) | 350 |

| CMA Aymara Women Artisans (Peru) | 327 |

| Territorial development in mountain areas (Peru) | 9,609 |

| CFS-RAI in Postgraduate Programs (Peru) | 1,406 |

| Villa Poppy – Family Farming (Dominican Republic) | 52 |

| University–Business Alliance UTESA–BANELINO–ISM (Dominican Republic) | 279 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).