1. Introduction

Noninvasive imaging techniques have been developed for diagnosis and clinical evaluation of cardiovascular diseases [

1,

2,

3]. Positron emission tomography (PET) permits molecular imaging techniques in vivo and quantitative assessment of tracer functions, including myocardial blood flow, energy metabolism, and various receptor functions in vivo [

3,

4,

5].

PET has a great advantage over other noninvasive imaging for performing various molecular imaging.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a radiopharmaceutical and glucose analog in which a hydroxyl group of the normal glucose molecule is replaced by

18F, a radioactive isotope of fluorine. FDG PET has been widely used for oncology studies, but also for cardiovascular diseases [

5].

Recently FDG PET has been applied to identify and assess active cardiovascular inflammation. This review summarizes the unique characteristics of FDG PET in the cardiovascular field among other non-invasive imaging modalities. This includes important patient preparation to apply FDG PET for cardiovascular inflammation. Various clinical applications in this area are fully described.

1.1. Advantages and Disadvantages of PET Compared to Other Non-Invasive Imaging Modalities (Table 1)

Ultrasound imaging is widely available, inexpensive, and repeatable and does not involve the use of ionizing radiation [

1,

2,

3,

6]. Due to high spatial resolution, it permits precise assessment of structural abnormalities in the cardiovascular system. In addition, color doppler ultrasound and contrast enhanced ultrasound are valuable for the assessment of functional and tissue alterations. It is generally performed by an experienced sonographer using high-quality. The main limitation of ultrasound imaging is that it cannot depict structures below bone or air, and therefore, it does not provide reliable information about the thoracic aorta, unless performed via a transesophageal approach. In addition, the acquisition of ultrasound images is operator dependent, although studies of vascular ultrasound have shown high rates of inter-operator agreement.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans are renowned for their speed and high spatial resolution, enabling detailed anatomical visualization that is crucial for the assessment of disease states [

1,

2,

3,

7]. The ability to capture fine structural details quickly makes CT an indispensable tool in acute care settings. However, the use of iodinated contrast media, necessary for enhancing image contrast, poses risks, particularly for patients with renal impairment. These patients may experience further renal damage or other adverse effects from the contrast agent. Additionally, the intrinsic radiation exposure associated with CT scans is a concern, particularly in scenarios requiring repeated imaging.

CT is nicely suited to demonstrate pathological changes in the cardiac wall, as well as large, deep blood vessels [

1,

2,

3,

7]. It is a widely available and reproducible technique with high spatial resolution. CT angiography allows for the simultaneous assessment of the myocardial wall, the lumen, and the affected vessels. It also permits the detection of coronary stenosis. On the other hand, it involves the use of ionizing radiation and carries a risk connected to the use of iodinated contrast material.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers distinct advantages over CT, particularly with its lack of ionizing radiation, making it safer for repeated use over time [

1,

2,

3,

8]. MRI excels in soft tissue contrast, making it ideal for imaging inflammatory changes in soft tissues and organs with superior clarity. However, the presence of loose metallic foreign bodies in a patient is a contraindication for MRI due to safety concerns and potential image distortion. Metal implants can also create significant artifacts, which may obscure diagnostic information and interfere with image interpretation. Despite these limitations, MRI remains a valuable tool for the detailed evaluation of inflammatory diseases without the risks associated with radiation.

PET/CT combines the anatomical detail provided by CT with the functional insight of PET imaging, offering a comprehensive overview of both structural and metabolic aspects of diseases in a single session [

3,

4]. This modality is particularly useful in evaluating inflammatory diseases as it can highlight areas of metabolic activity associated with inflammation. Importantly, PET/CT can be safely used in patients with renal failure, as it does not require iodinated contrast media. Nevertheless, the long acquisition times and exposure to ionizing radiation are significant drawbacks. Additionally, while PET/CT provides crucial functional information, its spatial resolution is less detailed compared to standalone CT, which can be a limitation in resolving fine anatomical details.

Table 1.

Features of non-invasive imaging techniques for assessing cardiovascular field.

Table 1.

Features of non-invasive imaging techniques for assessing cardiovascular field.

| |

Ultrasound |

CT |

MRI |

PET/CT |

| Focus |

Sound waves

Structure and flow analysis |

X-way attenuation

Structure and functional analysis |

Proton density and echo time

Edema and necrosis |

Various molecular functions

Glucose metabolism |

| Patient advantage |

Easy to perform even at bedside

No radiation |

Very fast scan

Evaluation of other organs |

No or minimally invasive procedure

No radiation |

Both anatomical and functional information

Safe in renal failure |

| Patient disadvantage |

Relatively long acquisition time

Operator dependent |

Radiation associated with imaging

Side effect by contrast media |

Long acquisition time

Claustrophobia due to smaller patient bore

Contraindicated in patients with loose foreign metals

High cost |

Long acquisition time

Radiation with radiopharmaceuticals

High cost |

| Imaging advantage |

High spatial resolution

Real-time imaging

Simultaneous assessment of cardiac function |

High spatial resolution

Can evaluate calcified plaques |

Superior soft tissue imaging with excellent spatial resolution

True multiplanar capability to image in any oblique plane |

Providing functional and biological information

Several tracers |

| Imaging disadvantage |

Limited use below bone or air

Limited use for cardiac devices |

Sub-optimal soft tissue imaging

Lack of functional and biological information |

MR image distortion

Limited use for cardiac device |

Limited spatial resolution

Variable effect of thresholds or other criteria |

1.2. Patient Preparation in FDG PET Study

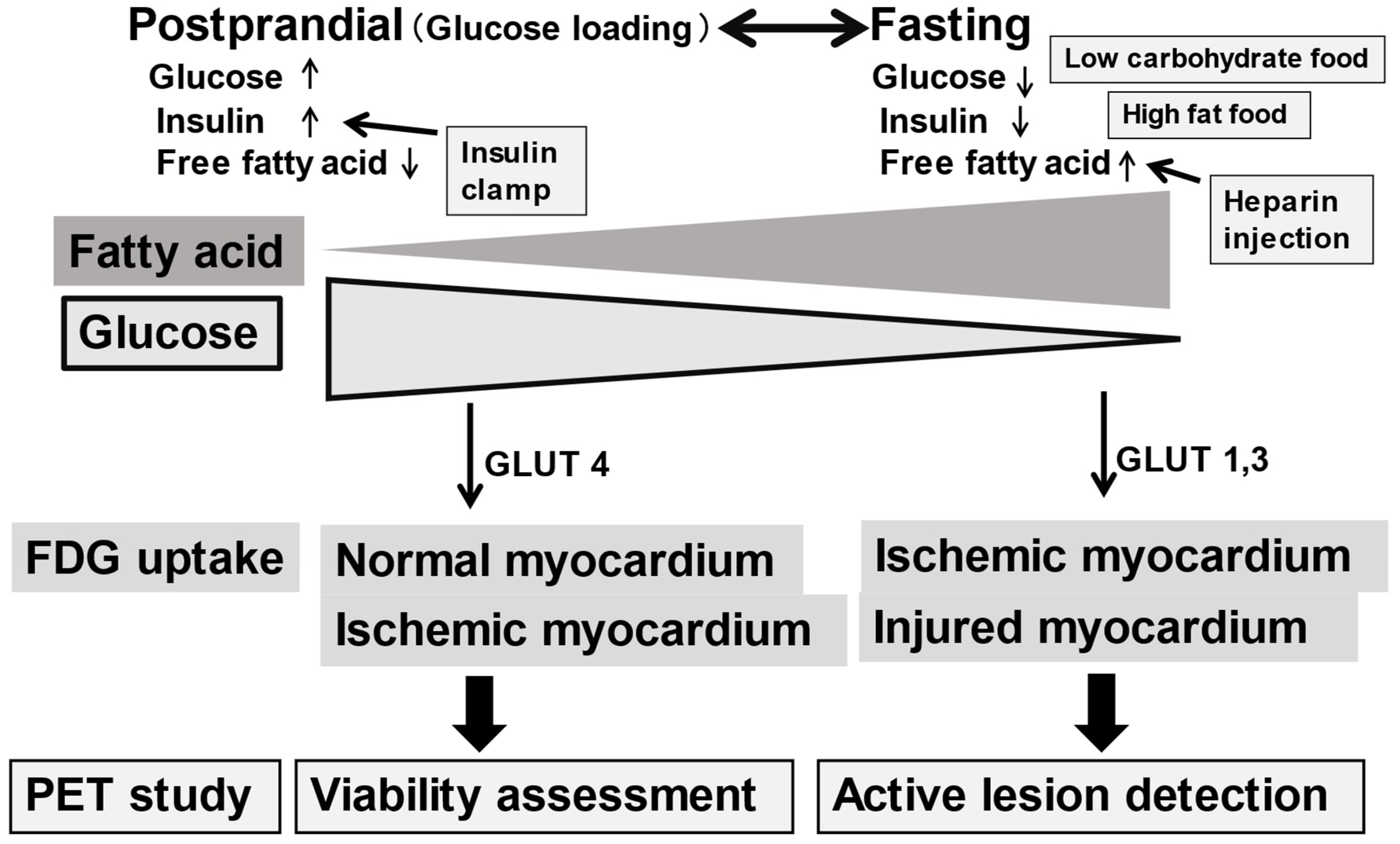

FDG uptake in the myocardium is dependent on cardiac energy substrate, either glucose or fatty acid depending on postprandial or long fasting conditions [

9,

10] (

Figure 1). FDG PET is applicable for any patient. In addition, whole-body imaging is available once FDG is administered. Thus, such whole-body study is commonly used in the studies in oncology and generalized inflammatory diseases. Glucose is the major energy source in the myocardium under postprandial or glucose loading condition. Therefore, FDG uptake is seen in normal and ischemic myocardium in these conditions. In fasting condition, on the contrary, glucose energy metabolism is suppressed, and fatty acids are the major energy source in the normal myocardium. Thus, FDG uptake is observed only in the ischemic and/or injured myocardium. Therefore, patient preparation before FDG administration is quite important since FDG uptake in the myocardium is observed as either physiological uptake or abnormal active uptake depending on the patient nutritional condition [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

One of the classical applications of PET is assessment of myocardial viability. FDG PET identifies glucose metabolism in the heart and thus myocardial viability [

16,

17,

18,

19]. A region with preserved FDG uptake indicates the presence of viable myocardium. For this purpose, glucose administration with oral loading or an insulin-glucose clamp is applied for an increase in FDG uptake both in the normal and ischemic but viable myocardium in comparison with no FDG uptake in infarcted tissue. Myocardial viability study using FDG PET has a great clinical impact on predicting reversible dysfunction after revascularization and prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction [

16,

17,

18,

19].

The activation of granulocytes and macrophages during inflammation enhances the FDG uptake. Thus, FDG PET is useful for detecting active cardiovascular inflammation [

20,

21]. In order to identify active inflammation by FDG PET, physiological uptake in the normal myocardium should be suppressed by appropriate patient preparation.

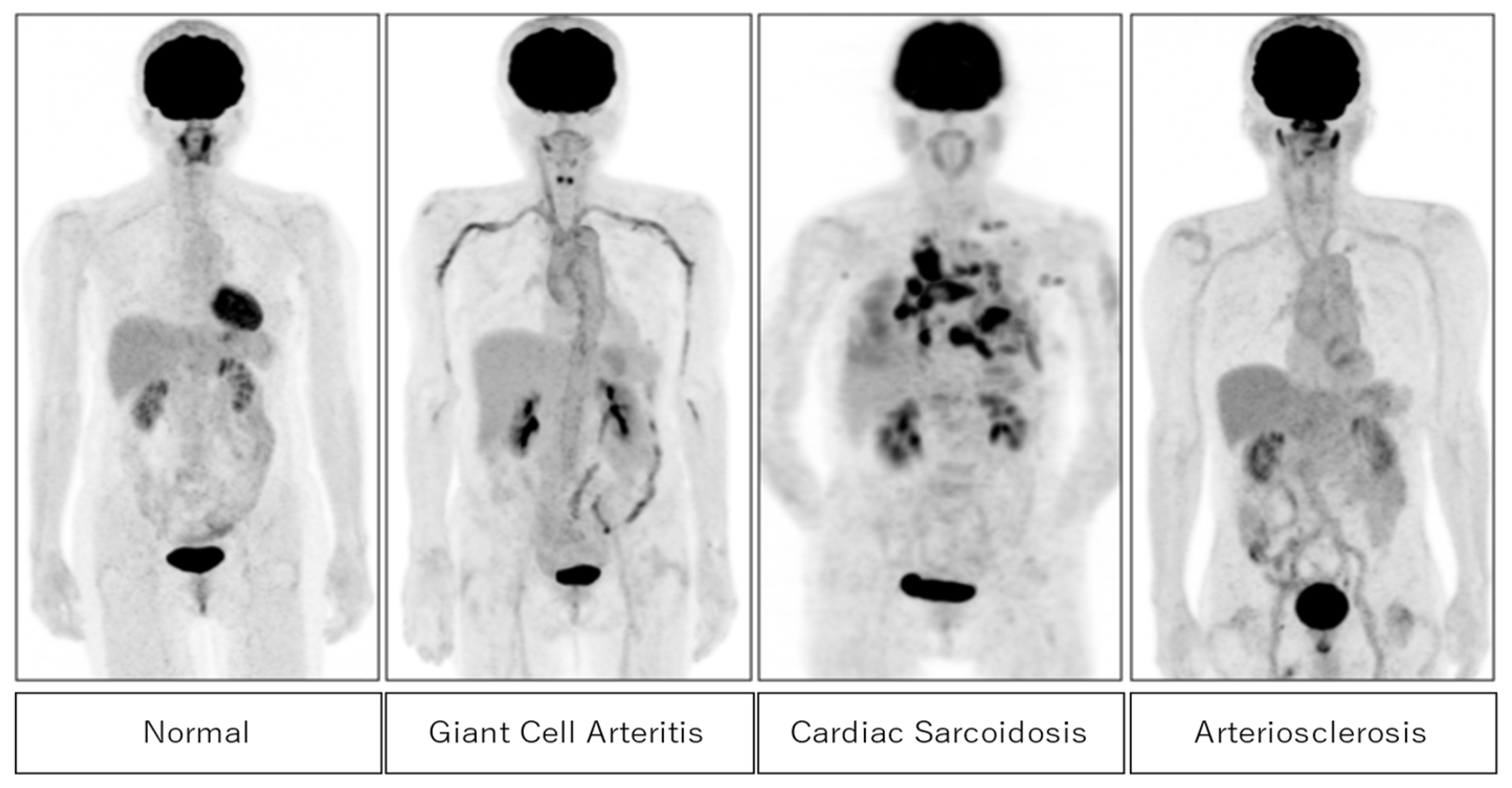

Figure 2 shows typical cases of positive FDG uptake in active inflammatory lesions in giant cell arteritis, cardiac sarcoidosis, and arteriosclerosis. High FDG uptake in large vessels is seen in giant cell arteritis and arteriosclerosis. In cardiac sarcoidosis, high FDG uptake in the myocardium and pulmonary nodules are well observed.

1.3. Roles of FDG-PET in Cardiovascular Inflammation

1.3.1. Assessment of Cardiac Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown cause [

22]. Cardiac involvement has the potential for life-threatening consequences such as atrioventricular block, ventricular arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, and sudden death [

23]. Therefore, accurate diagnosis, suitable treatment, and treatment monitoring are required for those suspected of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Non-invasive cardiac imaging has recently been developed: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and various radionuclide imaging, including FDG PET were added to the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (JMHW) modified diagnostic criteria for cardiac sarcoidosis in 2006 [

24] and 2016 [

25]. The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) also published an expert consensus statement in 2014 [

26]. The diagnostic pathways for cardiac sarcoidosis are divided into histological and clinical branches. Histopathological diagnosis is required to reveal noncaseating granulomas from endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) or surgical resection of the heart. However, the role of biopsy is limited as previously described [

22,

23]. Clinical diagnosis requires concordance among electrocardiography, echocardiography, and cellular and molecular imaging, including late gadolinium enhancement on MRI and FDG PET.

FDG PET is commonly used to assess the infiltration of sarcoidosis in the myocardium. Since FDG uptake is associated with the expression of glucose transporters, increased FDG uptake may reflect active inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and granulocytes. Thus, active sarcoid lesions may be nicely shown as focal FDG uptake in the myocardium as well as other active sarcoid lesions in the body. Patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis require adequate preparation, such as prolonged fasting, a low-carbohydrate diet, and/or a high-fat, high protein diet to suppress the false-positive association with physiological myocardial FDG uptake [

27,

28] as shown in

Figure 1. FDG PET with an adequate preparation protocol is ideal for detecting active lesions. When evaluating cardiac sarcoidosis, it is important to assess not only the extent of FDG uptake but also its location. The involvement of specific myocardial segments, particularly the basal to mid-anterior and mid-septal segments, is associated with higher event rates in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis [

29]. FDG PET is also valuable for assessing the response to anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] (

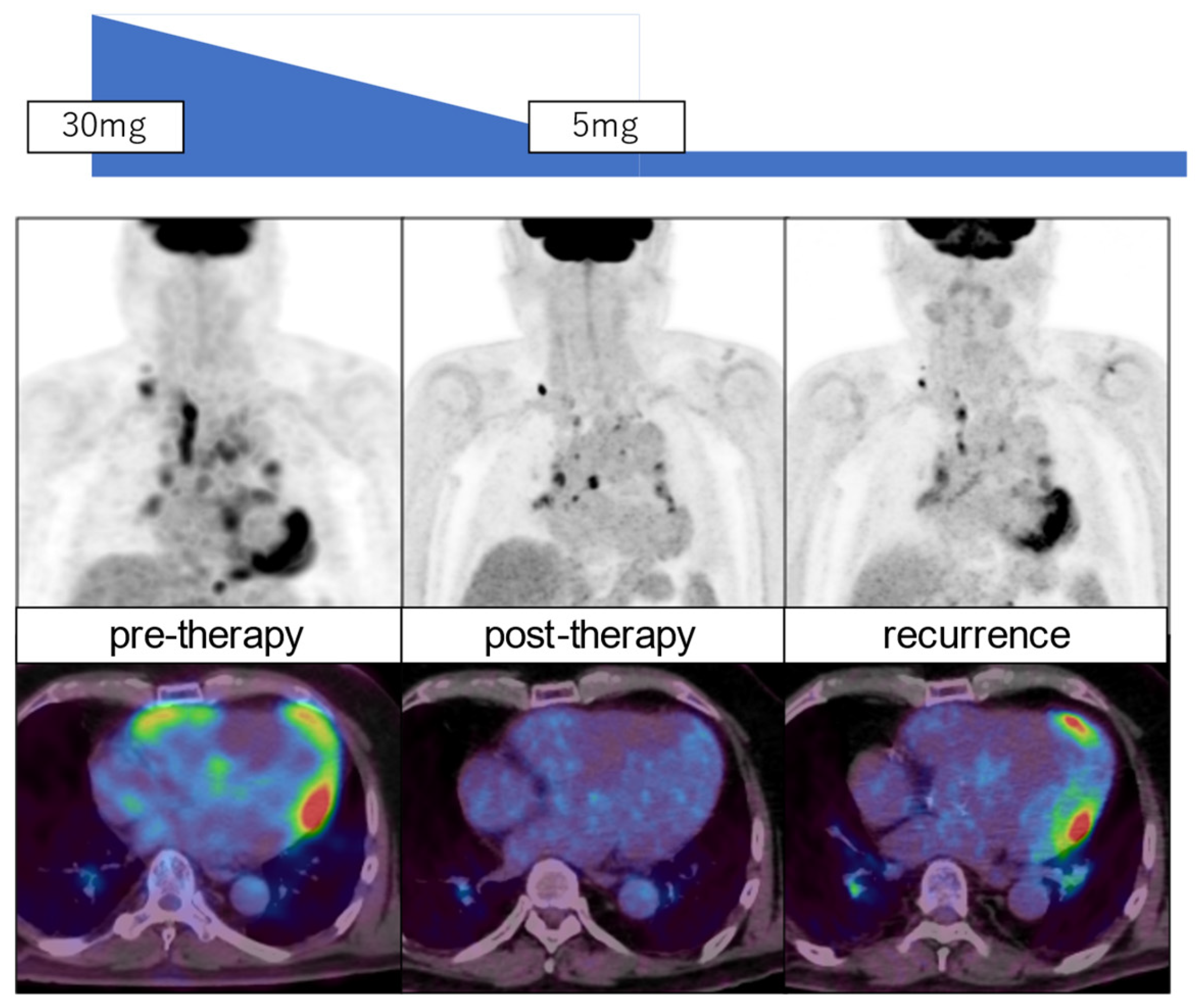

Figure 3). Furthermore, FDG PET has a potential for predicting patient outcomes [

32,

33].

A recent meta-analysis indicated that FDG-PET had slightly lower sensitivity than MRI but both modalities showed similar specificity for detecting cardiac sarcoidosis [

34]. FDG PET may be valuable for identifying active inflammation as high FDG uptake but not fibrotic cardiac sarcoidosis. Thus, both FDG PET and MRI have important roles in diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis and its tissue characterization. FDG PET and MRI are useful for the early detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. Ohira et al. investigated the prevalence and characteristics of cardiac sarcoidosis in patients with biopsy-proven extracardiac sarcoidosis, comparing those with normal and abnormal 12-lead electrocardiography and transthoracic echocardiography findings [

35]. They found that around 20% of patients with normal results on these tests still had cardiac sarcoidosis, emphasizing the importance of physicians remaining alert to the possibility of cardiac involvement even in the absence of conduction or structural abnormalities.

There are several clinical studies going to clarify the values of semi-quantitative analysis of FDG uptake in active lesions of cardiac sarcoidosis. One recent report showed a value of follow-up by FDG PET in patients with active cardiac sarcoidosis [

36]. After 12 months of prednisolone treatment, 80% of them showed a response with ≥70% metabolic reduction, but the remaining patients indicated either poor response or recurrence. Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term prognostic value using FDG PET and MRI in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.

2. Assessment of Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is another severe cardiac inflammation, where FDG PET plays an important role in its diagnosis and management. In addition to local damage in the myocardium, metastatic infection, embolic phenomenon, or immune-mediated damage may cause considerable morbidity and mortality. In many cases, endocarditis may often be associated with a prosthetic valve [

37]. Infective endocarditis demonstrates a variable clinical presentation, ranging from acute onset to a subacute or chronic course. The diagnosis is based on the modified Duke criteria: the major criteria include either the microbiological evidence of infection by typical microorganisms and/or the documentation of cardiac lesions by imaging techniques. The minor criteria include predisposing conditions, fever, embolic vascular dissemination, immunological phenomena, and microbiological evidence [

37,

38].

Cardiac devices have been accompanied by an even higher increasing rate of device infections. Echocardiography is the first-line imaging test in suspected endocarditis. However, echocardiography is more challenging in patients with prosthetic valves. Cardiac CT and MRI are commonly applied for assessing endocarditis. Such anatomical imaging can be affected by artifacts from the metal device, and abnormalities may not be specific for active infection. Therefore, they have an inherent limitation for accurate image analysis [

37,

38,

39]. FDG PET, on the other hand, plays a powerful tool not only for identifying active myocardial lesions but also for detecting metastatic and embolic lesions throughout the body due to a whole-body PET survey [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The extracardiac infection source findings might change the clinical management and the course of the disease. In patients with prosthetic valve–related endocarditis, FDG PET/CT can identify septic embolism events, which is critical for patient management [

39,

42]. FDG PET/CT may identify active inflammation in endocarditis earlier than structure abnormalities assessed by echocardiography and CT.

The meta-analysis of 13 studies involving 537 patients, PET/CT had moderate sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis [

43]. However, the sensitivity improved when the evaluation of patients with suspected prosthetic valve endocarditis was selected. These data suggest that PET/CT has the potential for use as an adjunctive diagnostic modality in challenging cases of possible infective endocarditis. Recent expert consensus recommendations from many European and American Societies support clinical values of FDG PET for the evaluation of suspected cardiovascular infection by increasing diagnostic accuracy, identifying extracardiac involvement, and assessing cardiac implanted device pockets, leads, and all portions of ventricular assist devices [

44]. This may aid in key medical and surgical considerations.

3. Assessment of Vasculitis

Vasculitis is a group of disorders characterized by inflammation of blood vessels, which can affect arteries, veins, or capillaries of various sizes (

Table 2). The inflammation can lead to vessel wall damage, narrowing, and even occlusion, disrupting blood flow and causing tissue damage. Vasculitis is classified based on the size of the affected vessels: large, medium, small, variable vessel vasculitis, and vasculitis associated with systemic diseases or specific causes [

45].

Large vessel vasculitis affects the largest arteries in the body, such as the aorta and its major branches. The large-vessel vasculitis is characterized by a mononuclear and granulomatous infiltration of the vessel wall. Two key types include giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Giant cell aortitis is more prevalent among Caucasians and occurs in individuals over the age of 50. It commonly affects the temporal arteries, leading to symptoms like headaches, jaw pain, and vision problems, and can lead to serious complications such as vision loss. Takayasu arteritis is mainly observed in female patients under the age of 40, with a predilection for individuals of Asian descent. The affected arteries in Takayasu arteritis are mainly in the mesenteric, renal, and ilio-femoral arteries while sparing the medium-sized cranial arteries. Takayasu arteritis has a greater propensity for causing severe focal stenotic lesions of the affected vessels than giant cell arteritis. In both large-vessel vasculitis, the inflammatory process may deteriorate the aortic wall, resulting in potentially life-threatening vascular complications. Therefore, it is important to establish a diagnosis as early as possible using suitable biomarkers and imaging methods [

46,

47].

Medium vessel vasculitis targets medium-sized arteries, which supply blood to specific organs. Polyarteritis Nodosa affects the main arteries of various organs, leading to organ ischemia (insufficient blood supply) and skin lesions. Kawasaki Disease, which primarily affects children, involves the coronary arteries and can lead to coronary artery aneurysms, along with fever and other systemic symptoms.

Small vessel vasculitis involves the smallest blood vessels, including capillaries, venules, and arterioles. Key examples include Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener’s Granulomatosis) and Microscopic Polyangiitis. These conditions often affect the respiratory tract and kidneys, leading to sinusitis, lung nodules, and kidney disease. Another small vessel vasculitis, Churg-Strauss Syndrome (or Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, EGPA), is marked by asthma, high eosinophil levels, and involvement of the skin, nerves, and heart.

Variable vessel vasculitis can affect vessels of any size. For instance, Behçet’s Disease causes recurrent ulcers on mucous membranes (oral and genital) and uveitis (eye inflammation), while Cogan’s Syndrome affects the eyes and ears, leading to ocular and auditory disturbances.

Some types of vasculitis are associated with systemic diseases. For example, Rheumatoid Vasculitis occurs in severe cases of rheumatoid arthritis, typically involving small and medium vessels. Similarly, Lupus Vasculitis affects multiple organs in individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Vasculitis is characterized by mostly autoimmunologically induced inflammatory processes of vascular structures. They have various clinical and radiologic appearances. Diagnosis and therapy monitoring of vasculitis are often challenging because of the heterogeneity of subgroups and their variable clinical, laboratory, and radiologic manifestations. The choice of an adequate imaging method mainly depends on the size and localization of the affected vessels, as well as on the patient’s individual circumstances and the specific question. For vascular imaging, morphologic changes in the context of the disease can be visualized by radiologic imaging methods in many forms of vasculitis, either directly by visualizing the vessel lesions or indirectly by visualizing the consequences of vessel inflammation in the affected organ. The choice of an adequate imaging modality depends on the size and localization of the affected vessels. Several different imaging techniques are available for visualizing direct and indirect signs of vessel inflammation. Vessel lesions in small vessel vasculitis are usually below the radiologic detection limits. Vascular imaging can also help in the selection of the best biopsy point [

48].

FDG PET imaging has recently been used for accurate detection of vascular inflammation in the aortic wall [

46,

49,

50,

51]. Functional FDG PET combined with anatomical CT angiography may be of synergistic value for optimal diagnosis, monitoring of disease activity, and evaluating damage progression in large vessel vasculitis. There is a joint paper showing international recommendations and statements, based on the available evidence in the literature and the consensus of experts on FDG PET study, including patient preparation under FDG PET/CT study, interpretation for the diagnosis, and follow-up of patients with suspected or diagnosed large vessel vasculitis [

50]. FDG PET is considered a valuable tool for monitoring the treatment effects of this disease. Based on the review of systematic literature, FDG PET showed sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 71% for detecting relapsing/refractory disease in patients with large vasculitis [

51]. In addition, a new recommendation for the use of imaging modalities including FDG PET has recently been reported in the diagnosis and management of patients with primary large vessel vasculitis [

52]. FDG PET may hold an important role in distinguishing between large vessel aortitis subtypes, evaluating disease distribution, and detecting extracranial involvement in patients with cranial giant cell arteritis or polymyalgia phenotypes [

53]. It also has a promising utility in predicting clinical outcomes and assessing treatment response, based on the correlation between reductions in FDG uptake and improved disease control. Future research should focus on further refining PET/CT techniques, exploring their utility in monitoring treatment response, and investigating novel imaging modalities.

4. Assessment of Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic condition characterized by arterial stiffening due to the buildup of cholesterol plaques on vessel walls. Progressive enlargement of these plaques may lead to a spectrum of debilitating cardiovascular conditions, such as peripheral artery disease, ischemic stroke, coronary artery disease, and acute myocardial infarctions. These conditions represent a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Therefore, a suitable diagnosis to identify unstable atherosclerotic disease is valuable [

54,

55].

Hypercholesterolemia with deposition and oxidation of low-density lipoproteins in the arterial vessel wall may be responsible for the initiation and progression of atherogenesis. The migration, infiltration, and death of inflammatory monocytes/macrophages in the arterial wall ultimately lead to the formation of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques at high risk for causing fatal cardiovascular events [

54,

55]. In addition, systemic inflammation, such as inflammatory or autoimmune diseases may also accelerate the development of atherosclerosis, independent of lipid levels.

Non-invasive imaging is becoming more essential to investigate the role of inflammation in cardiovascular diseases. Conventional imaging modalities, including ultrasonography, CT, and MRI angiography, are widely used clinically to visualize large symptomatic plaques but are limited in their ability to assess the early stages of atherosclerosis [

56,

57]. Atherosclerotic plaque is another target for PET to identify microscopic inflammation. Molecular imaging using FDG and/or

18F-sodium fluoride (NAF) targeting microcalcification is clinically used in combination with high resolution CT or MRI [

58,

59]. The most used diagnostic signs are halo sign in ultrasound study and visual positive uptake on FDG PET which are often seen not only in large vessel vasculitis but also in atherosclerosis. When visually scoring FDG uptake intensity and pattern, FDG PET/CT attained 95% specificity for diagnosing LVV against an atherosclerotic control group [

60].

These imaging are applied for assessing carotid plaque and even coronary plaque. A whole-body PET may identify unpredictable atherosclerotic plaque and even embolic lesions after endocarditis [

61,

62]. FDG vascular uptake is reflective of functional changes in the arterial vessel wall which may predict structural changes related to the progression of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, this study suggests that early targeting of vascular inflammation with appropriate therapeutic regimens may slow down the formation of high-risk, vulnerable plaques [

54,

55].

5. Assessment in Cardio-Oncology

Cancer and cardiovascular disease are the leading causes of death in most developed countries. Cancer and cardiovascular disease are closely related from both scientific and clinical perspectives. Advances in cancer treatment have improved in patient survival rate of cancer. On the other hand, management of cardiovascular complications has been increasingly required in cancer patients. Both cardiologists and oncologists should pay caution in this new field called “cardio-oncology” [

63,

64,

65,

66]. More recently, radiologists have played important roles in suitable image selection and interpretations for assessing cardiovascular complications. In addition, radiology specialists may provide appropriate radiotherapy planning with reduced radiation dose to the cardiovascular system. Radiotherapy is well known to have significant cardiovascular complications, such as pericarditis, and long-term complications, such as restrictive or constrictive pericarditis. Cardiovascular imaging has played a key role for the non-invasive assessment of cardiovascular alterations complimentary to biomarkers and clinical assessment. Cardiovascular imaging should also play an important role for suitable radiation planning [

67].

Secondary large vessel vasculitis should also be considered. Extensive chemotherapy for cancer treatment, particularly human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor, may cause severe cardiotoxic effects [

63,

64]. In addition, radiation therapy for the esophageal cancer or breast cancer may possibly cause cardiovascular dysfunction [

65,

66]. Novel therapeutic therapies have significantly improved survival and long-term outcomes in many cancer entities. Unfortunately, this improvement in outcome is often accompanied by increasingly relevant therapy-related cardiovascular toxicity. Molecular imaging using MRI and nuclear imaging are used for assessing tissue function before and after cancer therapy from molecular perspectives. Since FDG PET is often applied for the detection, and extension of cancers, and cancer treatment monitoring. FDG PET is valuable for detecting active cardiovascular inflammation, particularly in the early stage of cancer therapy, and monitoring toxic effects [

67]. Cardiovascular toxicity may carry a risk of arterial thrombosis, including myocardial infarction. FDG serves as a sensitive indicator of the metabolic shift in the myocardium, which occurs in the early stages of coronary artery disease [

67].

Active cardiovascular inflammation may often be observed on abnormal FDG uptake after cancer treatment, which may possibly cause fatal cardiovascular dysfunction. Suitable imaging modalities in combination with suitable biomarkers should play an important role in detecting and monitoring cardiotoxic effects after cancer treatment [

68,

69]. Particularly, FDG PET is considered an elegant approach for the simultaneous assessment of tumor response to cancer therapy and early detection of possible cardiovascular involvement as well [

69,

70,

71,

72].

6. Conclusions

Among various imaging methods for assessing cardiovascular dysfunction, FDG PET is useful for detecting active cardiovascular inflammation mainly due to enhanced glucose utilization by the activation of granulocytes and macrophages. To identify active inflammation by FDG PET, physiological uptake in the normal myocardium should be suppressed by appropriate patient preparation. FDG PET has been used to detect active lesions and assess the response to anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. FDG PET has also been used to identify other active cardiovascular inflammation, such as endocarditis, aortitis, and unstable atherosclerosis. Furthermore, FDG PET may be applied not only to assess response to cancer therapy but also to detect possible cardiovascular involvement. More clinical experiences are expected to confirm the value of FDG PET for assessing and monitoring active cardiovascular inflammation.

Funding

Nagara Tamaki received Gtants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Grant Number JP23K07078.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ju D, Schoenhagen P, Soman P, Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2019 Appropriate use criteria for multimodality imaging in the assessment of cardiac structure and function in nonvalvular heart disease. J Nucl Cardiol 2019; 26(4): 1392-1413. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati E, Moroni F, Pedrotti P, Scotti I, Magnoni M, Bozzolo EP, Rimoldi OE, Camici PG. Non-Invasive Imaging of Vascular Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2014 Aug 18;5:399. [CrossRef]

- Bax JJ, Di Carli M, Narula J, Delgado V. Multimodality imaging in ischaemic heart failure. Lancet. 2019 Mar 9;393(10175):1056-1070. [CrossRef]

- Bengel FM, Higuchi T, Javadi MS, Lautamaki R. Cardiac positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:1-15.

- Manabe O, Kikuchi T, Scholte AJHA, El Mahdiui M, Nishii R, Zhang MR, Suzuki E, Yoshinaga K. Radiopharmaceutical tracers for cardiac imaging. J Nucl Cardiology. 2018;25(4):1204-36. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt WA, Kraft HE, Vorpahl K, Volker L, Gromnica-Ihle EJ. Color duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. N Engl J Med (1997) 337(19):1336–42. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal N, Kalra N, Garg MK, Kang M, Lal A, Jain S, et al. Multidetector CT angiography in Takayasu arteritis. Eur J Radiol (2011) 77(2):369–74 10.1016. [CrossRef]

- Hartung MP, Grist TM, Francois CJ. Magnetic resonance angiography: current status and future directions. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson (2011) 13:19. 10.1186/1532-429X-13-19. [CrossRef]

- Scholtens AM, Verberne HJ, Budde RP, Lam MG. Additional heparin preadministration improves cardiac glucose metabolism suppression over low-carbohydrate diet alone in ¹⁸F-FDG PET Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2016 Apr;57(4):568-73. [CrossRef]

- Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Ohira H, Masuda A, Sato T, Tsujino I, Yamada A, Oyama-Manabe N, Hirata K, Nishimura M, Tamaki N. The effects of 18-h fasting with low-carbohydrate diet preparation on suppressed physiological myocardial (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and possible minimal effects of unfractionated heparin use in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016 Apr;23(2):244-52. [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga J, Derenoncourt P, Haq A, Bhandiwad A, Laforest R, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Gropler RJ, Schindler TH. 18F-FDG PET in myocardial viability assessment: A practical and time-efficient protocol. J Nucl Med. 2022 Apr;63(4):602-608. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj S, Seidelmann SB, Soni M, Bhattaru A, Margulies KB, Shah SH, Dugyala S, Qian C, Pryma DA, Arany Z, Kelly DP, Chirinos JA, Bravo PE. Comprehensive nutrient consumption estimation and metabolic profiling during ketogenic diet and relationship with myocardial glucose uptake on FDG-PET. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Nov 17;23(12):1690-1697. [CrossRef]

- Hutt E, Goldar G, Jaber WA, Cremer PC. Standardized ketogenic dietary preparation for metabolic PET imaging in suspected and known cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J Imaging Methods Pract. 2024 May 9;2(1):qyae037. [CrossRef]

- Celiker-Guler E, Ruddy TD, Wells RG. Acquisition, processing, and interpretation of PET 18F-FDG viability and inflammation studies. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021 Jul 16;23(9):124. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Jang J, Lim S, Na SJ. Evaluation of clinical variables affecting myocardial glucose uptake in cardiac FDG PET. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Aug 6;14(16):1705. [CrossRef]

- Tillisch J, Brunken R, Marshall R, Schwaiger M, Mandelkern M, Phelps M, Schelbert H. Reversibility of cardiac wall-motion abnormalities predicted by positron tomography. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 884-888. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki N, Kawamoto M, Tadamura E, Magata Y, Yonekura Y, Nohara R, Sasayama S, Nishimura K, Ban T, Konishi J: Prediction of reversible ischemia after revascularization: perfusion and metabolic studies using positron emission tomography. Circulation 1995; 91(6): 1697-1705. [CrossRef]

- Allman KC, Shaw LJ, Hachamovitch R, Udelson JE. Myocardial viability testing and impact of revascularization on prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 1151-1158. [CrossRef]

- Adhaduk M, Paudel B, Liu K, Ashwath M, Gebska MA, Delcour K, Samuelson RJ, Giudici M. Comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the assessment of myocardial viability: meta-analysis and systematic review. J Nucl Cardiol. 2023 Dec;30(6):2514-2524. [CrossRef]

- Juneau D, Erthal F, Alzahrani A, Alenazy A, Nery PB, Beanlands RS, Chow BJ. Systemic and inflammatory disorders involving the heart: the role of PET imaging. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016; 60(4): 383-96.

- Tam MC, Patel VN, Weinberg RL, Hulten EA, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD, Corbett JR, Murthy VL. Diagnostic Accuracy of FDG PET/CT in suspected LVAD infections: A case series, systematic review, and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2019. Jul 17. pii: S1936-878X(19)30568-6.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2153-65.

- Blankstein R, Osborne M, Naya M, Waller A, Kim CK, Murthy VL, Kazemian P, Kwong RY, Tokuda M, Skali H, Padera R, Hainer J, Stevenson WG, Dorbala S, DiCarli MF. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:329-36. [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa M, Yokoyama R, Nishiyama Y, Ogimoto A, Higaki J, Mochizuki T. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography for imaging of inflammatory cardiovascular diseases. Circ J 2014; 78: 1302–1310. [CrossRef]

- Terasaki F, Azuma A, Anzai T, Ishizaka N, Ishida Y, Isobe M, Inomata T, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Eishi Y, Kitakaze M, Kusano K, Sakata Y, Shijubo N, Tsuchida A, Tsutsui H, Nakajima T, Nakatani S, Horii T, Yazaki Y, Yamaguchi E, Yamaguchi T, Ide T, Okamura H, Kato Y, Goya M, Sakakibara M, Soejima K, Nagai T, Nakamura H, Noda T, Hasegawa T, Morita H, Ohe T, Kihara Y, Saito Y, Sugiyama Y, Morimoto SI, Yamashina A; Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS 2016 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ J 2019; 83: 2329-2388. [CrossRef]

- Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CN, Judson MA, Kron J, Mehta D, Nielsen JC, Patel AR, Ohe T, Raatikainen P, Soejima K. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2014, 11, 1305–1323. [CrossRef]

- Kumita S, Yoshinaga K, Miyagawa M, Momose M, Kiso K, Kasai T, Naya M; Committee for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis using 18F-FDG PET, Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology. Recommendations for 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis-2018 update: Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology recommendations. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 Aug;26(4):1414-1433. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Sweiss NJ, Macapinlac HA. What is the optimal method on myocardial suppression in FDG PET/CT evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis? Clin. Nucl. Med. 2021, 46, 904–905. [CrossRef]

- Devesa A, Robson PM, Cangut B, Vazirani R, Vergani V, LaRocca G, Romero-Daza AM, Liao S, Azoulay LD, Pyzik R, Fayad RA, Jacobi A, Abgral R, Morgenthau AS, Miller MA, Fayad ZA, Trivieri MG. Specific locations of myocardial inflammation and fibrosis are associated with higher risk of events in cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2024 Sep 10:S1547-5271(24)03301-0. [CrossRef]

- Vidula MK, Selvaraj S, Rojulpote C, Bhattaru A, Kc W, Hansbury M, Schubert E, Clancy CB, Rossman M, Goldberg LR, Farwell M, Pryma D, Bravo PE. Relationship of ketosis with myocardial glucose uptake among patients undergoing FDG PET/CT for evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Aug;17(8):e016774. [CrossRef]

- Saric P, Bois JP, Giudicessi JR, Rosenbaum AN, Kusmirek JE, Lin G, Chareonthaitawee P. Imaging of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: An update and future aspects. Semin Nucl Med. 2024 Sep;54(5):701-716. [CrossRef]

- Nakajo M, Hirahara D, Jinguji M, Ojima S, Hirahara M, Tani A, Takumi K, Kamimura K, Ohishi M, Yoshiura T. Machine learning approach using 18F-FDG-PET-radiomic features and the visibility of right ventricle 18F-FDG uptake for predicting clinical events in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Jpn J Radiol. 2024 Jul;42(7):744-752. [CrossRef]

- Kafil TS, Shaikh OM, Fanous Y, Benjamen J, Hashmi MM, Jawad A, Dahrouj T, Abazid RM, Swiha M, Romsa J, Beanlands RSB, Ruddy TD, Mielniczuk L, Birnie DH, Tzemos N. Risk stratification in cardiac sarcoidosis with cardiac positron emission tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Sep;17(9):1079-1097.

- Aitken M, Chan MV, Urzua Fresno C, Farrell A, Islam N, McInnes MDF, Iwanochko M, Balter M, Moayedi Y, Thavendiranathan P, Metser U, Veit-Haibach P, Hanneman K. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac MRI versus FDG PET for cardiac sarcoidosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2022 Sep;304(3):566-57. [CrossRef]

- Ohira H, Sato T, Manabe O, Oyama-Manabe N, Hayashishita A, Nakaya T, Nakamura J, Suzuki N, Sugimoto A, Furuya S, Tsuneta S, Watanabe T, Tsujino I, Konno S. Underdiagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis by ECG and echocardiography in cases of extracardiac sarcoidosis. ERJ Open Res. 2022 May 9;8(2):00516-2021. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto R, Unno K, Fujita N, Sakuragi Y, Nishimoto T, Yamashita M, Kuwayama T, Hiraiwa H, Kondo T, Kuwatsuka Y, Okumura T, Ohshima S, Takahashi H, Ando M, Ishii H, Kato K, Murohara T. Prospective analysis of immunosuppressive therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis with fluorodeoxyglucose myocardial accumulation: The PRESTIGE Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Jan;17(1):45-58.

- Habib G, Erba PA, Iung B, Donal E, Cosyns B, Laroche C, Popescu BA, Prendergast B, Tornos P, Sadeghpour A, Oliver L, Vaskelyte JJ, Sow R, Axler O, Maggioni AP, Lancellotti P; EURO-ENDO Investigators. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Oct 14;40(39):3222-3232.

- Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, Bonaros N, Brida M, Burri H, Caselli S, Doenst T, Ederhy S, Erba PA, Foldager D, Fosbøl EL, Kovac J, Mestres CA, Miller OI, Miro JM, Pazdernik M, Pizzi MN, Quintana E, Rasmussen TB, Ristić AD, Rodés-Cabau J, Sionis A, Zühlke LJ, Borger MA; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2023;44:3948–4042. [CrossRef]

- Dilsizian V, Budde RPJ, Chen W, Mankad SV, Lindner JR, Nieman K. Best practices for imaging cardiac device-related infections and endocarditis: A JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging Expert Panel Statement. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 May;15(5):891-911.

- Pizzi MN, Roque A, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Cuéllar-Calabria H, Ferreira-González I, Gonzàlez-Alujas MT, Oristrell G, Gracia-Sánchez L, González JJ, Rodríguez-Palomares J, Galiñanes M, Maisterra-Santos O, Garcia-Dorado D, Castell-Conesa J, Almirante B, Aguadé-Bruix S, Tornos P. Improving the diagnosis of infective endocarditis in prosthetic valves and intracardiac devices with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography angiography: Initial results at an infective endocarditis referral center. Circulation. 2015;132(12):1113–26. [CrossRef]

- Sammartino AM, Bonfioli GB, Dondi F, Riccardi M, Bertagna F, Metra M, Vizzardi E. Contemporary Role of positron emission tomography (PET) in endocarditis: A narrative review. J Clin Med. 2024 Jul 15;13(14):4124. [CrossRef]

- Tanis W, Scholtens A, Habets J, van den Brink RB, van Herwerden LA, Chamuleau SA, Budde RP. CT angiography and 18F-FDG-PET fusion imaging for prosthetic heart valve endocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Sep;6(9):1008-13. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Ajmal S, Farid S, O’Horo JC, Chareonthaitawee P, Baddour LM, Sohail MR. Meta-analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 Jun;26(3):922-935. [CrossRef]

- Bourque JM, Birgersdotter-Green U, Bravo PE, Budde RPJ, Chen W, Chu VH, Dilsizian V, Erba PA, Gallegos Kattan C, Habib G, Hyafil F, Khor YM, Manlucu J, Mason PK, Miller EJ, Moon MR, Parker MW, Pettersson G, Schaller RD, Slart RHJA, Strom JB, Wilkoff BL, Williams A, Woolley AE, Zwischenberger BA, Dorbala S. 18F-FDG PET/CT and Radiolabeled Leukocyte SPECT/CT Imaging for the Evaluation of Cardiovascular Infection in the Multimodality Context: ASNC Imaging Indications (ASNC I2) Series Expert Consensus Recommendations From ASNC, AATS, ACC, AHA, ASE, EANM, HRS, IDSA, SCCT, SNMMI, and STS. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Jun;17(6):669-701. [CrossRef]

- Broncano J, Vargas D, Bhalla S, Cummings KW, Raptis CA, Luna A. CT and MR Imaging of cardiothoracic vasculitis. Radiographics 2018 Jul-Aug;38(4):997-1021. [CrossRef]

- van der Geest KSM, Gheysens O, Gormsen LC, Glaudemans AWJM, Tsoumpas C, Brouwer E, Nienhuis P, van Praagh GD, Slart RHJA. Advances in PET imaging of large vessel vasculitis: An update and future Trends. Semin Nucl Med 2024; 54: 753-760. [CrossRef]

- Maz M, Chung SA, Abril A, Langford CA, Gorelik M, Guyatt G, Archer AM, Conn DL, Full KA, Grayson PC, Ibarra MF, Imundo LF, Kim S, Merkel PA, Rhee RL, Seo P, Stone JH, Sule S, Sundel R, Vitobaldi OI, Warner A, Byram K, Dua AB, Husainat N, James KE, Kalot MA, Lin YC, Springer JM, Turgunbaev M, Villa-Forte A, Turner AS, Mustafa R. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation guideline for the management of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol, 73 (2021), pp. 1349-1365. [CrossRef]

- Guggenberger KV, Bley TA. Imaging vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020 Jun 19;22(8):34. [CrossRef]

- Yabusaki S, Oyama-Manabe N, Manabe O, Hirata K, Kato F, Miyamoto N, Matsuno Y, Kudo K, Tamaki N, Shirato H. Characteristics of immunoglobulin G4-related aortitis/periaortitis and periarteritis on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography co-registered with contrast-enhanced computed tomography. EJNMMI Res. 2017 Dec;7(1):20. [CrossRef]

- van der Valk FM, Verweij SL, Zwinderman KA, Strang AC, Kaiser Y, Marquering HA, Nederveen AJ, Stroes ES, Verberne HJ, Rudd JH. Thresholds for arterial wall inflammation quantified by 18F-FDG PET imaging: Implications for vascular Interventional studies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9(10): 1198-1207.

- van der Geest KSM, Treglia G, Glaudemans AWJM, Brouwer E, Sandovici M, Jamar F, Gheysens O, Slart RHJA. Diagnostic value of [18F]FDG-PET/CT for treatment monitoring in large vessel vasculitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 Nov;48(12):3886-3902. [CrossRef]

- Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Bond M, Bosch P, Ponte C, Mackie SL, Bley TA, Blockmans D, Brolin S, Bolek EC, Cassie R, Cid MC, Molina-Collada J, Dasgupta B, Nielsen BD, De Miguel E, Direskeneli H, Duftner C, Hočevar A, Molto A, Schäfer VS, Seitz L, Slart RHJA, Schmidt WA. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 May 15;83(6):741-751.

- Collada-Carrasco J, Gomez-Leon N, Castillo-Morales V, Lumbreras-Fernandez B, Castaneda S, Rodriguez-Laval V. Role and potential of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography in large-vessel vasculitis: a comprehensive review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024. PMID: 39170047. [CrossRef]

- Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:56. [CrossRef]

- Raynor WY, Park PSU, Borja A, Sun Y, Werner T, Ng SJ, Lau HC, Hoilund-Carsen PF, Alavi A, Revheim ME. PET-based imaging with 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF to assess inflammation and microcalcification in atherosclerosis and other vascular and thrombotic disorders. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11,2234. [CrossRef]

- Syed MB, Fletcher A, O Forsythe R, Kaczynski J, E Newby D, Dweck MR, Van Beek EJ. Emerging techniques in atherosclerosis imaging. Br. J. Radiol. 2019;92:20180309. [CrossRef]

- Takx RA, Partovi S, Ghoshhajra BB. Imaging of atherosclerosis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016;32:5–12. [CrossRef]

- Kirienko M, Erba PA, Chiti A, Sollini M. Hybrid PET/MRI in infection and inflammation: An update about the latest available literature evidence. Semin Nucl Med. 2023 Jan;53(1):107-124. [CrossRef]

- Maes L, Versweyveld L, Evans NR, McCabe JJ, Kelly P, Van Laere K, Lemmens R. Novel targets for molecular imaging of inflammatory processes of carotid atherosclerosis: A systematic Review. Semin Nucl Med. 2024 Sep;54(5):658-673. [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis PH, van Praagh GD, Glaudemans AWJM, Brouwer E, Slart RHJA. A review on the value of imaging in differentiating between large vessel vasculitis and atherosclerosis J Pers Med. 2021 Mar 23;11(3):236. [CrossRef]

- Granados U, Fuster D, Pericas JM, Llopis JL, Ninot S, Quintana E, Almela M, Paré C, Tolosana JM, Falces C, Moreno A, Pons F, Lomeña F, Miro JM; Hospital clinic endocarditis study group. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in infective endocarditis and implantable cardiac electronic device infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Nucl Med. 2016 Nov;57(11):1726-1732. [CrossRef]

- Tonutti A, Scarfò I, La Canna G, Selmi C, De Santis M. Diagnostic work-up in patients with nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. J Clin Med. 2023 Sep 7;12(18):5819. [CrossRef]

- Long HD, Lin YE, Zhang JJ, Zhong WZ, Zheng RN. Risk of congestive heart failure in early Breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant treatment with trastuzumab: A meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2016 May;21(5):547-54. [CrossRef]

- Michel L, Helfrich I, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Mincu RI, Korste S, Mrotzek SM, Spomer A, Odersky A, Rischpler C, Herrmann K, Umutlu L, Coman C, Ahrends R, Sickmann A, Löffek S, Livingstone E, Ugurel S, Zimmer L, Gunzer M, Schadendorf D, Totzeck M, Rassaf T. Targeting early stages of cardiotoxicity from anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Eur Heart J. 2022 Jan 31;43(4):316-329. [CrossRef]

- Banfill K, Giuliani M, Aznar M, Franks K, McWilliam A, Schmitt M, Sun F, Vozenin MC, Faivre Finn C; IASLC Advanced radiation technology committee. Cardiac toxicity of thoracic radiotherapy: Existing evidence and future directions. J Thorac Oncol. 2021 Feb;16(2):216-227. [CrossRef]

- Meattini I, Poortmans PM, Aznar MC, Becherini C, Bonzano E, Cardinale D, Lenihan DJ, Marrazzo L, Curigliano G, Livi L. Association of breast cancer irradiation with cardiac toxic effects: A Narrative Review. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Jun 1;7(6):924-932.

- Tamaki N, Manabe O, Hirata K. Cardiovascular imaging in cardio-oncology. Jpn J Radiol. 2024 Aug 29. [CrossRef]

- Berliner D, Beutel G, Bauersachs J. Echocardiography and biomarkers for the diagnosis of cardiotoxicity. Herz. 2020 Nov;45(7):637-644. [CrossRef]

- Battisha A, Mann C, Raval R, Anandaram A, Patel B. Clinical applications and advancements of positron emission tomography/computed tomography in cardio-oncology: A comprehensive literature review and emerging perspectives. Curr Oncol Rep. 2024 Sep 25. [CrossRef]

- Haider A, Bengs S, Schade K, Wijnen WJ, Portmann A, Etter D, Fröhlich S, Warnock GI, Treyer V, Burger IA, Fiechter M, Kudura K, Fuchs TA, Pazhenkottil AP, Buechel RR, Kaufmann PA, Meisel A, Stolzmann P, Gebhard C. Myocardial 18F-FDG uptake pattern for cardiovascular risk stratification in patients undergoing oncologic PET/CT. J Clin Med. 2020 Jul 17;9(7):2279. [CrossRef]

- Tong J, Vogiatzakis N, Andres MS, Senechal I, Badr A, Ramalingam S, Rosen SD, Lyon AR, Nazir MS. Complementary use of cardiac magnetic resonance and 18F-FDG positron emission tomography imaging in suspected immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis. Cardiooncology. 2024 Aug 22;10(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Kersting D, Mavroeidi IA, Settelmeier S, Seifert R, Schuler M, Herrmann K, Rassaf T, Rischpler C. Molecular imaging biomarkers in cardiooncology: A view on established technologies and future perspectives. J Nucl Med. 2023 Nov;64(Suppl 2):29S-38S. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).