Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Methodology

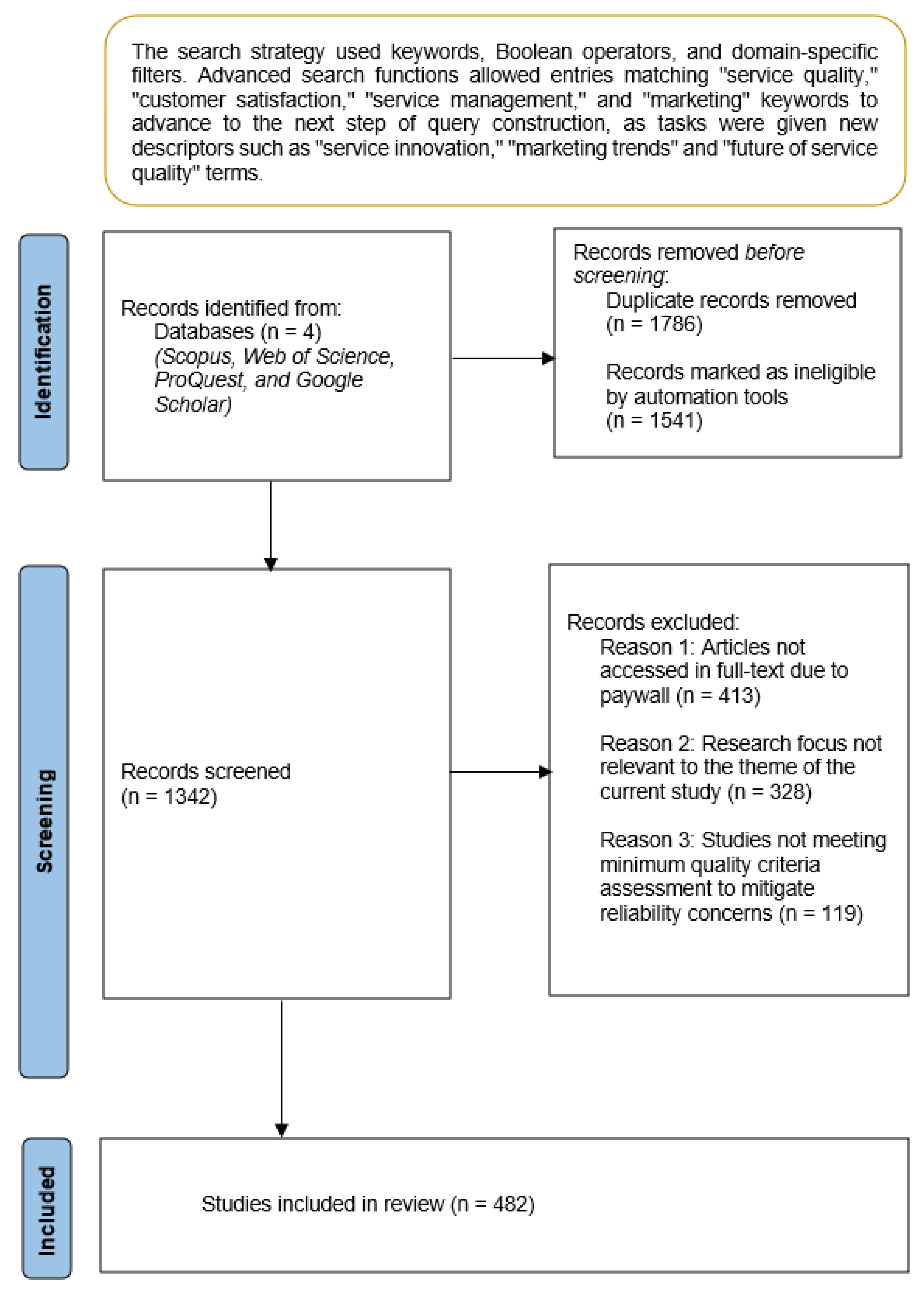

3.1. Literature Search Strategy

3.2. Identification of Due Articles

3.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

4. Results and Discussion

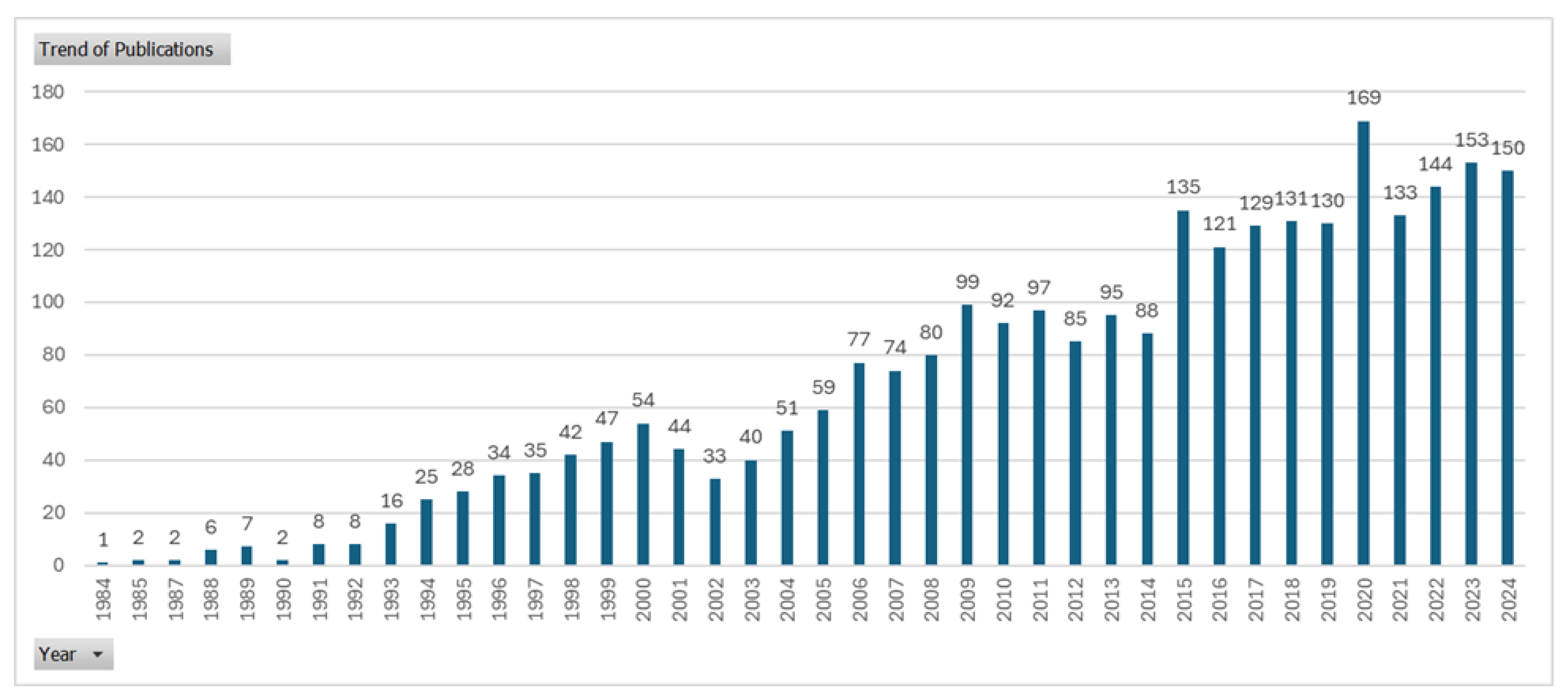

4.1. Bibliometric Corpus Performance

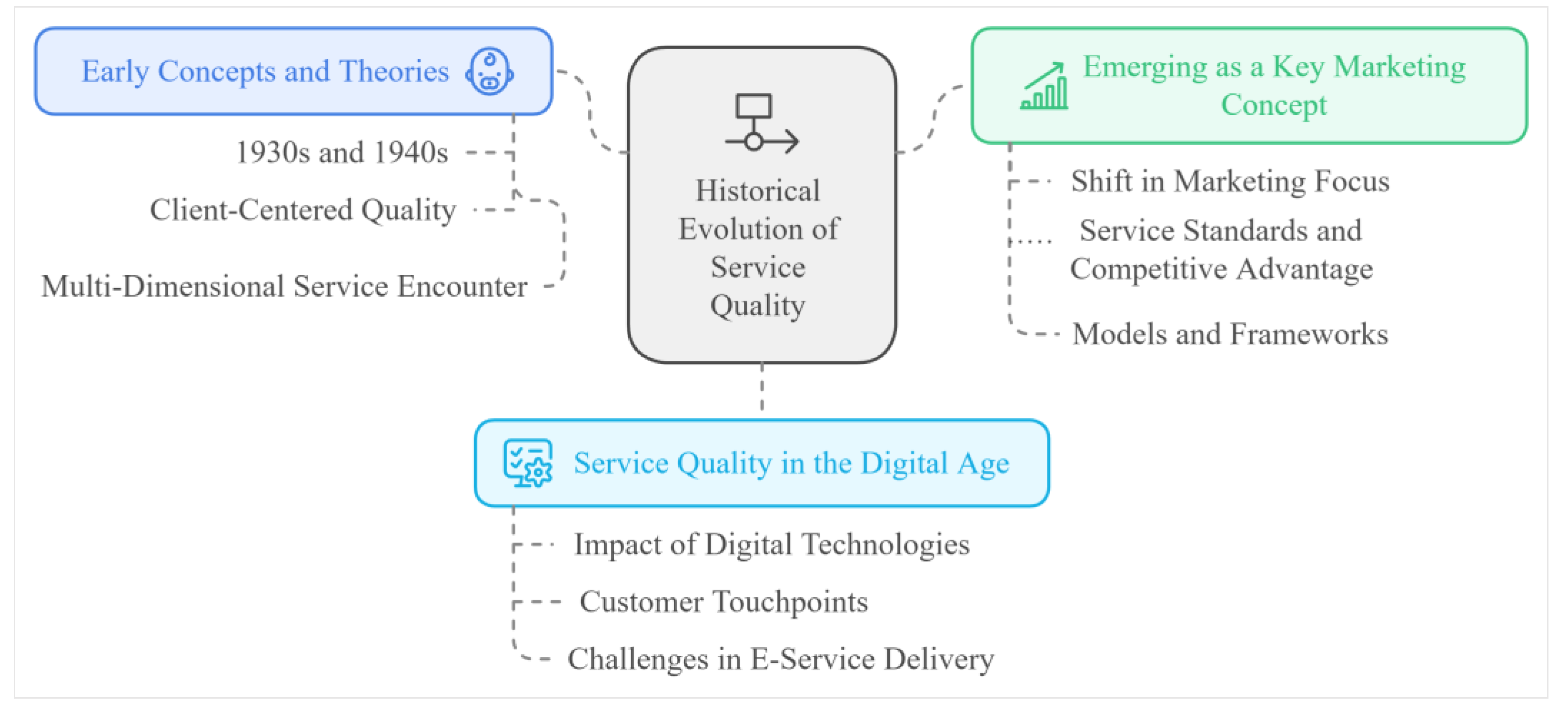

4.1. Evolution of Service Quality

4.1.1. Early Concepts and Theories

4.1.2. Emerging as a Key Marketing Concept

4.1.3. Service Quality in the Digital Age

- Impact of technology on service delivery

- Online reviews and reputation management

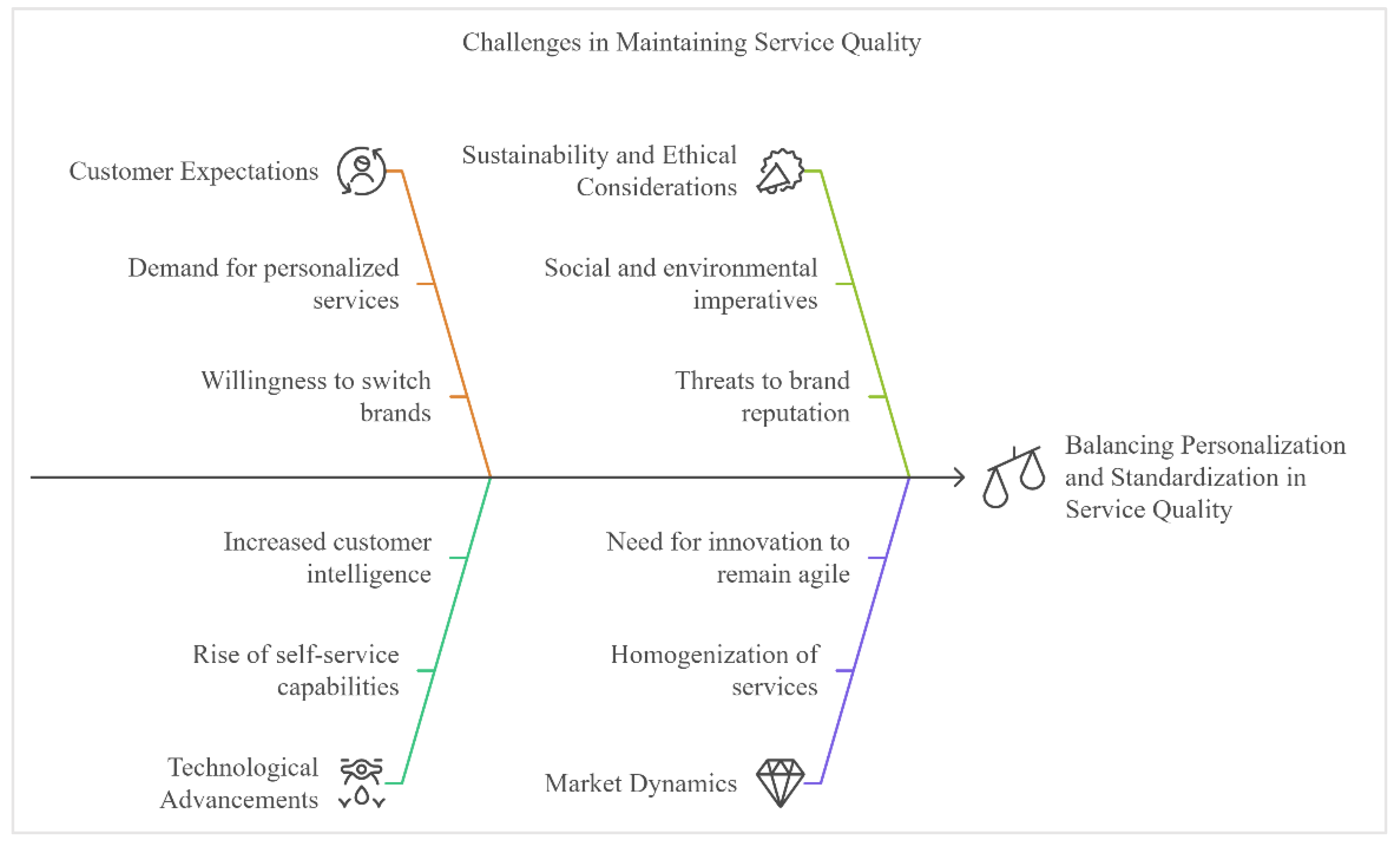

4.2. Current Trends and Challenges in Service Quality

4.2.1. Personalisation and Customisation

4.2.2. Sustainability and Ethical Considerations

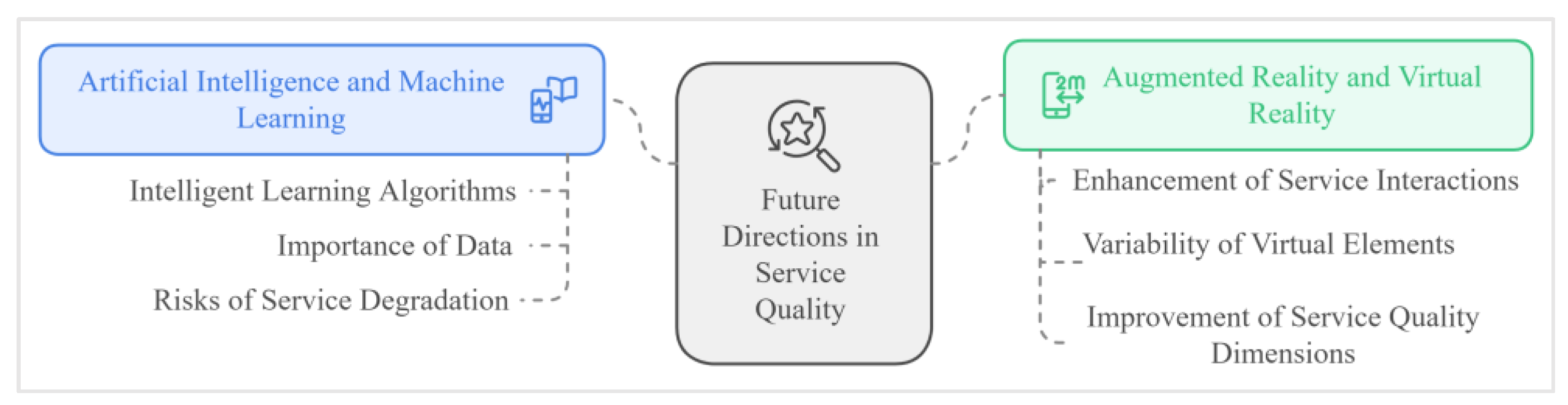

4.3. Future Directions in Service Quality

4.3.1. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

4.3.2. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Service Quality

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Key Findings and Implications for Marketing Practice

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. Wilson, V. Zeithaml, M. J. Bitner, and D. Gremler, Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2020.

- C. Grönroos, “A service quality model and its marketing implications,” Eur. J. Mark., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 36–44, 1984. [CrossRef]

- A. Parasuraman, V. A. Zeithaml, and L. L. Berry, “Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality,” J. Retail., vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 12–40, 1988.

- S. Periyasami and A. P. Periyasamy, “Metaverse as future promising platform business model: Case study on fashion value chain,” Businesses, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 527–545, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. J. P. Nautwima and A. R. Asa, “The impact of quality service on customer satisfaction in the banking sector amidst Covid-19 pandemic: A literature review for the state of current knowledge,” Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 31–38, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Asa, J. P. Nautwima, and H. Villet, “An integrated approach to sustainable competitive advantage,” Int. J. Bus. Soc., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 201–222, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. H. Tien and L. T. M. Huong, “Factors affecting customers satisfaction on public internet service quality in Vietnam,” Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 10057939, 2003. [CrossRef]

- U. Ahunjonov, A. R. Asa, and M. Amonboyev, “An empirical analysis of SME innovativeness characteristics in an emerging transition economy: The case of Uzbekistan,” Eur. J. Bus. Manag., vol. 5, no. 32, pp. 129–135, 2013.

- S. A. Raza, A. Umer, M. A. Qureshi, and A. S. Dahri, “Internet banking service quality, e-customer satisfaction and loyalty: The modified e-SERVQUAL model,” TQM J., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1443– 1466, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.U. H. Uzir et al., “The effects of service quality, perceived value and trust in home delivery service personnel on customer satisfaction: Evidence from a developing country,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 63, p. 102721, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Becker and E. Jaakkola, “Customer experience: Fundamental premises and implications for research,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 630–648, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. D. Hoyer, M. Kroschke, B. Schmitt, K. Kraume, and V. Shankar, “Transforming the customer experience through new technologies,” J. Interact. Mark., vol. 51, pp. 57–71, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Kalbach, Mapping experiences: A complete guide to creating value through journeys, blueprints, and diagrams, 2nd ed. O’Reilly Media, 2020.

- J. P. Nautwima and A. R. Asa, “Exploring the Challenges and Factors Impeding Effective Public Service Delivery at a Municipality in Namibia,” Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 15–24, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Ali et al., “Impact of service quality on the customer satisfaction: Case study at online meeting platforms,” J. Appl. Res. High. Educ., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 65–77, 2021.

- H. M. Alzoubi and M. Inairat, “Do perceived service value, quality, price fairness and service recovery shape customer satisfaction and delight? A practical study in the service telecommunication context,” Uncertain Supply Chain Manag., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 579–588, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Dam and T. C. Dam, “Relationships between service quality, brand image, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty,” J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 585–593, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. R. Haddaway, M. J. Page, C. C. Pritchard, and L. A. McGuinness, “PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency,” Campbell Syst. Rev., vol. 18, p. 1230, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M.B. Harari, H. R. Parola, C. J. Hartwell, and A. Riegelman, “Literature searches in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A review, evaluation, and recommendations,” J. Vocat. Behav., vol. 118, p. 103377, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.U. H. Uzir, I. Jerin, H. Al Halbusi, A. B. A. Hamid, and A. S. A. Latiff, “Does quality stimulate customer satisfaction where perceived value mediates and the usage of social media moderates?,” Heliyon, vol. 6, no. 9, p. 04977, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhong and H. C. Moon, “What drives customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in fast-food restaurants in China? Perceived price, service quality, food quality, physical environment quality,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 460, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Hajli, “The role of social support on relationship quality and social commerce,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 87, pp. 17–27, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- I. W. E. Arsawan, V. Koval, I. Rajiani, N. W. Rustiarini, W. G. Supartha, and N. P. S. Suryantini, “Leveraging knowledge sharing and innovation culture into SMEs sustainable competitive advantage,” Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag., vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 405–428, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Azeem, M. Ahmed, S. Haider, and M. Sajjad, “Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation,” Technol. Soc., vol. 65, p. 10 1476, 2021.

- I. Farida and D. Setiawan, “Business strategies and competitive advantage: The role of performance and innovation,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 163, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tu and W. Wu, “How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 28, pp. 775–787, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. T. Howley and D. L. Thompson, Fitness professional’s handbook, 7th ed. Human Kinetics, 2022.

- G. Medberg and C. Grönroos, “Value-in-use and service quality: Do customers see a difference?,” J. Serv. Theory Pract., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 507–529, 2020.

- A. Rosário and R. Raimundo, “Consumer marketing strategy and E-commerce in the last decade: A literature review,” J Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res., vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 3003–3024, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Sharma, “Consumers’ purchase behaviours and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda,” Int. J. Consum. Stud., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 1095–1119, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Tanrikulu, “Theory of consumption values in consumer behavior research: A review and future research agenda,” Int. J. Consum. Stud., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 695–715, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Zeithaml, K. Verleye, I. Hatak, M. Koller, and A. Zauner, “Three decades of customer value research: Paradigmatic roots and future research avenues,” J. Serv. Res., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 409–432, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Distanont, “The role of innovation in creating a competitive advantage,” Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 150–157, 2020.

- S. M. Lee and D. H. Lee, “Opportunities and challenges for contactless healthcare services in the post-COVID-19 Era,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 167, p. 12 0712, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Li et al., “Quality of primary health care in China: Challenges and recommendations,” The Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10239, pp. 1802– 1812, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li and H. Shang, “Service quality, perceived value, and citizens’ continuous-use intention regarding e-government: Empirical evidence from China,” Inf. Manage., vol. 57, no. 3, p. 103197, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R.Nunkoo, V. Teeroovengadum, C. M. Ringle, and V. Sunnassee, “Service quality and customer satisfaction: The moderating effects of hotel star rating,” Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 91, p. 102414, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S.Shokouhyar, S. Shokoohyar, and S. Safari, “Research on the influence of after-sales service quality factors on customer satisfaction,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 56, p. 102139, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Morrison, Hospitality and travel marketing, 8th ed. Cengage Learning, 2022.

- N. Paley, The manager’s guide to competitive marketing strategies, 5th ed. Routledge, 2021.

- Y. Ren, Y. Choe, and H. Song, “Antecedents and consequences of brand equity: Evidence from Starbucks coffee brand,” Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 108, p. 103351, 2023.

- D. Grewal, J. Hulland, P. K. Kopalle, and E. Karahanna, “The future of technology and marketing: A multidisciplinary perspective,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2020.

- D. L. Hoffman, C. P. Moreau, S. Stremersch, and M. Wedel, “The rise of new technologies in marketing: A framework and outlook,” J. Mark., vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2022.

- R. T. Rust, “The future of marketing,” Int. J. Res. Mark., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 15–26, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. V. M. V. D. Udovita, “Conceptual review on dimensions of digital transformation in the modern era,” Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 520–529, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Chylinski, J. Heller, T. Hilken, D. I. Keeling, D. Mahr, and K. Ruyter, “Augmented reality marketing: A technology-enabled approach to situated customer experience,” Australas. Mark. J., vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 374–384, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Rangaswamy, N. Moch, C. Felten, G. Bruggen, J. E. Wieringa, and J. Wirtz, “The role of marketing in digital business platforms,” J. Interact. Mark., vol. 51, pp. 72–90, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Witell et al., “Characterizing customer experience management in business markets,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 116, pp. 420–430, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Field et al., “Service research priorities: Designing sustainable service ecosystems,” J. Serv. Res., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 462–479, 2021.

- P. K. Kopalle, V. Kumar, and M. Subramaniam, “How legacy firms can embrace the digital ecosystem via digital customer orientation,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 114–131, 2020.

- E. H. Manser Payne, A. J. Dahl, and J. Peltier, “Digital servitization value co-creation framework for AI services: A research agenda for digital transformation in financial service ecosystems,” J. Res. Interact. Mark., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 200–222, 2021.

- R. Y. Du, O. Netzer, D. A. Schweidel, and D. Mitra, “Capturing marketing information to fuel growth,” J. Mark., vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 163–183, 2021.

- H. Nam and P. K. Kannan, “Digital environment in global markets: Cross-cultural implications for evolving customer journeys,” J. Int. Mark., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 28–47, 2020.

- C. Ngarmwongnoi, J. S. Oliveira, M. AbedRabbo, and S. Mousavi, “The implications of eWOM adoption on the customer journey,” J. Consum. Mark., vol. 37, no. 7, pp. 749–759, 2020.

- A. P. Goldstein and G. Y. Michaels, Empathy: Development, training, and consequences. Routledge, 2021.

- L. Osler, Taking empathy online: A study on the impacts of digital interaction. Routledge, 2024.

- A. S. Ranchordas, “Empathy in the digital administrative state,” Duke Law J., vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 53–104, 2021. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol71/iss1/2.

- A. Alkraiji and N. Ameen, “The impact of service quality, trust and satisfaction on young citizen loyalty towards government e-services,” Inf. Technol. People, 2022.

- A. N.Ameen, A. Tarhini, A. Reppel, and A. Anand, “Customer experiences in the age of artificial intelligence,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 58, p. 102308, 2021.

- A. Demir L. Maroof, N. U. Sabbah Khan, and B. J. Ali, “The role of E-service quality in shaping online meeting platforms: A case study from the higher education sector,” J. Appl. Res. High. Educ., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1436–1463, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, Y. C. Lin, W. H. Chen, C. F. Chao, and H. Pandia, “Role of government to enhance digital transformation in small service business,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 1462, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Lee and D. H. Lee, “Untact: A new customer service strategy in the digital age,” Serv. Bus., vol. 14, pp. 1–22, 2020.

- S.J. Barnes, J. Mattsson, F. Sørensen, and J. F. Jensen, “Measuring employee-tourist encounter experience value: A big data analytics approach,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 154, p. 113450, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Filieri, Z. Lin, Y. Li, X. Lu, and X. Yang, “Customer emotions in service robot encounters: A hybrid machine-human intelligence approach,” J. Serv. Res., vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 614–629, 2022.

- C. Prentice and M. Nguyen, “Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service,” J Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 56, p. 102186, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Allam, A. Sharifi, S. E. Bibri, D. S. Jones, and J. Krogstie, “The metaverse as a virtual form of smart cities: Opportunities and challenges for environmental, economic, and social sustainability in urban futures,” Smart Cities, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 144–161, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Grzegorczyk, M. Mariniello, L. Nurski, and T. Schraepen, “Blending the physical and virtual: A hybrid model for the future of work,” Econstor Discuss. Pap., vol. 17, pp. 1–23, 2021.

- N. Xi, J. Chen, F. Gama, M. Riar, and J. Hamari, “The challenges of entering the metaverse: An experiment on the effect of extended reality on workload,” Inf. Syst. Front., 2023.

- D. Agostino, M. Arnaboldi, and M. D. Lema, “New development: COVID-19 as an accelerator of digital transformation in public service delivery,” Public Money Manag., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 69–72, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. F.Borges, F. J. Laurindo, M. M. Spínola, R. F. Gonçalves, and C. A. Mattos, “The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: Systematic literature review and future research directions,” Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 57, p. 102225, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Haleem, M. Javaid, M. A. Qadri, R. P. Singh, and R. Suman, “Artificial intelligence (AI) applications for marketing: A literature-based study,” Int. J. Intell. Netw., vol. 3, pp. 119–132, 2022.

- J. Ribeiro, R. Lima, T. Eckhardt, and S. Paiva, “Robotic process automation and artificial intelligence in industry 4.0: A literature review,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 181, pp. 51–58, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Tschang and E. Almirall, “Artificial intelligence as augmenting automation: Implications for employment,” Acad. Manag. Perspect., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 586–605, 2021.

- V. Caiati, S. Rasouli, and H. Timmermans, “Bundling, pricing schemes and extra features preferences for mobility as a service: Sequential portfolio choice experiment,” Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract., vol. 131, pp. 123–148, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Gebauer et al., “How to convert digital offerings into revenue enhancement: Conceptualizing business model dynamics through explorative case studies,” Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 91, pp. 429–441, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Guidon, M. Wicki, T. Bernauer, and K. Axhausen, “Transportation service bundling: For whose benefit? Consumer valuation of pure bundling in the passenger transportation market,” Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract., vol. 131, pp. 91–106, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Wassouf, R. Alkhatib, K. Salloum, and S. Balloul, “Predictive analytics using big data for increased customer loyalty: Syriatel Telecom Company case study,” J. Big Data, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 44, 2020.

- S. F. Bernritter, P. E. Ketelaar, and F. Sotgiu, “Behaviorally targeted location-based mobile marketing,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 677–702, 2021.

- G. Cliquet and J. Baray, Location-based marketing: Geomarketing and geolocation. Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- H. Huang, Location-based services. Springer Handbook of Geographic Information, 2022.

- Y. Pan and D. Wu, “A novel recommendation model for online-to-offline service based on the customer network and service location,” J. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 97–123, 2020.

- A. H. Busalim and F. Ghabban, “Customer engagement behaviour on social commerce platforms: An empirical study,” Technol. Soc., vol. 64, p. 101437, 2021.

- A. Siebert, A. Gopaldas, A. Lindridge, and C. Simões, “Customer experience journeys: Loyalty loops versus involvement spirals,” J. Mark., vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 45–66, 2020.

- H. Alzoubi, M. Alshurideh, B. Kurdi, I. Akthis, and R. Aziz, “Does BLE technology contribute towards improving marketing strategies, customers’ satisfaction and loyalty? The role of open innovation,” Int. J. Data Netw. Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 449–460, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, D. Ramachandran, and B. Kumar, “Influence of new-age technologies on marketing: A research agenda,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 125, pp. 864–877, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Hoehle, V. Venkatesh, S. A. Brown, B. J. Tepper, and T. Kude, “Impact of customer compensation strategies on outcomes and the mediating role of justice perceptions: A longitudinal study of Target’s data breach,” MIS Q., vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 473–502, 2022.

- L. I. Labrecque, E. Markos, K. Swani, and P. Peña, “When data security goes wrong: Examining the impact of stress, social contract violation, and data type on consumer coping responses following a data breach,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 126, pp. 284–298, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Huang and R. T. Rust, “Engaged to a robot? The role of AI in service,” J. Serv. Res., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 30–41, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Sandberg, J. Holmström, and K. Lyytinen, “Digitization and phase transitions in platform organizing logics: Evidence from the process automation industry,” MIS Q., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 129–153, 2020.

- L. Wu, A. Fan, Y. Yang, and Z. He, “Tech-touch balance in the service encounter: The impact of supplementary human service on consumer responses,” Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 101, p. 103122, 2022.

- M. Cheng, J. Liu, J. Qi, and F. Wan, “Differential effects of firm generated content on consumer digital engagement and firm performance: An outside-in perspective,” Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 94, pp. 208–220, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Kar, S. Kumar, and P. V. Ilavarasan, “Modelling the service experience encounters using user-generated content: A text mining approach,” Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 267–288, 2021.

- J. Mohammad, F. Quoquab, R. Thurasamy, and M. N. Alolayyan, “The effect of user-generated content quality on brand engagement: The mediating role of functional and emotional values,” J. Electron. Commer. Res., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 39–55, 2020.

- H. Li, H. Liu, H. H. Shin, and H. Ji, “Impacts of user-generated images in online reviews on customer engagement: A panel data analysis,” Tour. Manag., 2024.

- W. M. Lim, S.-F. Yap, and M. Makkar, “Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading?,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 122, pp. 534–566, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Mariani, R. Perez-Vega, and J. Wirtz, “AI in marketing, consumer research and psychology: A systematic literature review and research agenda,” Psychol. Mark., vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Bacile, “Digital customer service and customer-to-customer interactions: Investigating the effect of online incivility on customer perceived service climate,” J. Serv. Manag., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 105–122, 2020.

- D. Herhausen, O. Emrich, D. Grewal, P. Kipfelsberger, and M. Schoegel, “Face forward: How employees’ digital presence on service websites affects customer perceptions of website and employee service quality,” J. Mark. Res., vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 917–936, 2020.

- A. L. Ostrom et al., “Service research priorities: Managing and delivering service in turbulent times,” J. Serv. Res., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 329–353, 2021.

- P. Aula and S. Mantere, Strategic reputation management: Towards a company of good. Springer, 2020.

- T. Islam et al., “The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 25, pp. 123–135, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Javed, M. A. Rashid, G. Hussain, and H. Y. Ali, “The effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and firm financial performance: Moderating role of responsible leadership,” Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 1395–1409, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. U. Khan, Y. Salamzadeh, Q. Iqbal, and S. Yang, “The impact of customer relationship management and company reputation on customer loyalty: The mediating role of customer satisfaction,” J. Relatsh. Mark., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 2022.

- J. Bundy, F. Iqbal, and M. D. Pfarrer, “Reputations in flux: How a firm defends its multiple reputations in response to different violations,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 132–156, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Nasiri and S. Shokouhyar, “Actual consumers’ response to purchase refurbished smartphones: Exploring perceived value from product reviews in online retailing,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 61, p. 102569, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Joshi and P. Garg, “Role of brand experience in shaping brand love,” Int. J. Consum. Stud., vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 259–272, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Keiningham et al., “Customer experience-driven business model innovation,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 116, pp. 431–440, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Bag, G. Srivastava, M. M. A. Bashir, S. Kumari, M. Giannakis, and A. H. Chowdhury, “Journey of customers in this digital era: Understanding the role of artificial intelligence technologies in user engagement and conversion,” Benchmarking Int. J., vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 2140–2162, 2022.

- J. P. Bharadiya, “A comparative study of business intelligence and artificial intelligence with big data analytics,” Am. J. Artif. Intell., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 24–36, 2023.

- D. Chandler, Strategic corporate social responsibility: Sustainable value creation. Sage Publications, 2022.

- G. Halkos and S. Nomikos, “Corporate social responsibility: Trends in global reporting initiative standards,” Econ. Anal. Policy, vol. 69, pp. 106–117, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. He and L. Harris, “The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 116, pp. 176–182, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Okaily, A. Lutfi, A. Alsaad, A. Taamneh, and A. Alsyouf, “The determinants of digital payment systems’ acceptance under cultural orientation differences: The case of uncertainty avoidance,” Technol. Soc., vol. 63, p. 101367, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kashef A. Visvizi, and O. Troisi, “Smart city as a smart service system: Human-computer interaction and smart city surveillance systems,” Comput. Hum. Behav., vol. 124, p. 106923, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Suchek C. I. Fernandes, S. Kraus, M. Filser, and H. Sjögrén, “Innovation and the circular economy: A systematic literature review,” Bus. Strategy Environ., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 3686–3702, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Aheleroff, N. Mostashiri, X. Xu, and R. Y. Zhong, “Mass personalisation as a service in industry 4.0: A resilient response case study,” Adv. Eng. Inform., vol. 50, p. 101438, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Chandra, S. Verma, W. M. Lim, S. Kumar, and N. Donthu, “Personalization in personalized marketing: Trends and ways forward,” Psychol. Mark., vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 1529– 1562, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Pallant, S. Sands, and I. Karpen, “Product customization: A profile of consumer demand,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 54, p. 102030, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V.Sima, I. G. Gheorghe, J. Subić, and D. Nancu, “Influences of the industry 4.0 revolution on the human capital development and consumer behavior: A systematic review,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 10, p.4035, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim and K. Lee, “The paradigm shift of mass customisation research,” Int. J. Prod. Res., vol. 61, no. 10, pp. 3350–3376, 2023.

- M. Zhang, L. Sun, F. Qin, and G. A. Wang, “E-service quality on live streaming platforms: Swift guanxi perspective,” J. Serv. Mark., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 312–324, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Aaker and C. Moorman, Strategic market management, 11th ed. Wiley & Sons, 2023.

- P. Fader, Customer centricity: Focus on the right customers for strategic advantage. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

- J. N. Sheth and A. Parvatiyar, “Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven,” J. Macromarketing, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 150–165, 2021.

- X. Islami, N. Mustafa, and M. Topuzovska Latkovikj, “Linking Porter’s generic strategies to firm performance,” Future Bus. J., vol. 6, pp. 1–15, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Stonig, T. Schmid, and G. Müller-Stewens, “From product system to ecosystem: How firms adapt to provide an integrated value proposition,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 43, no. 9, pp. 1707–1729, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Taeuscher, E. Y. Zhao, and M. Lounsbury, “Categories and narratives as sources of distinctiveness: Cultural entrepreneurship within and across categories,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 2101–2134, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Ferrarini, “Redefining corporate purpose: Sustainability as a game changer,” in Sustainable finance in Europe: Corporate governance, financial stability and financial markets, Springer, 2021, pp. 85–150.

- A.M. Suartika and A. Cuthbert, “The sustainable imperative—Smart cities, technology and development,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 21, p.8892, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Alam and K. Z. Islam, “Examining the role of environmental corporate social responsibility in building green corporate image and green competitive advantage,” Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 8, 2021.

- I. Ruiz-Mallén and M. Heras, “What sustainability? Higher education institutions’ pathways to reach the agenda 2030 goals,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 4, p.1290, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Shayan, N. Mohabbati-Kalejahi, S. Alavi, and M. A. Zahed, “Sustainable development goals (SDGs) as a framework for corporate social responsibility (CSR,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 3, p.1222, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. K. F. Wong, S. S. Kim, S. Lee, and S. Elliot, “An application of Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process in understanding hotel corporate social responsibility performance scale,” in Sustainable Consumer Behaviour and the Environment, T. Oates and D. Starks, Eds., Springer, 2021, pp. 133–159.

- E. J. Woo and E. Kang, “Environmental issues as an indispensable aspect of sustainable leadership,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 7014, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. K. N. Gamage, E. M. S. Ekanayake, G. A. K. N. J. Abeyrathne, R. P. I. R. Prasanna, J. M. S. B. Jayasundara, and P. S. K. Rajapakshe, “A review of global challenges and survival strategies of small and medium enterprises (SMEs,” Economies, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 79, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma, T. Y. Leung, R. P. Kingshott, N. S. Davcik, and S. Cardinali, “Managing uncertainty during a global pandemic: An international business perspective,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 116, pp. 188–192, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Singh and M. Misra, “Linking corporate social responsibility (CSR) and organizational performance: The moderating effect of corporate reputation,” Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ., vol. 27, no. 1, p. 10 0139, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Swaminathan, A. Sorescu, J. B. E. Steenkamp, T. C. G. O’Guinn, and B. Schmitt, “Branding in a hyperconnected world: Refocusing theories and rethinking boundaries,” J. Mark., vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 24–46, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Abbas, “Impact of total quality management on corporate sustainability through the mediating effect of knowledge management,” J Clean. Prod., vol. 244, p. 118806, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Chiarini, “Industry 4.0, quality management and TQM world. A systematic literature review and a proposed agenda for further research,” TQM J., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 603–616, 2020.

- J. (David) Xu, I. Benbasat, and R. T. Cenfetelli, “Integrating Service Quality with System and Information Quality: An Empirical Test in the E-Service Context,” MIS Q., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 777–794, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Muharam, H. Chaniago, E. Endraria, and A. B. Harun, “E-service quality, customer trust and satisfaction: Market place consumer loyalty analysis,” J. Minds Manaj. Ide Dan Inspirasi, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 237–254, 2021.

- J. W. Nadeem, M. Juntunen, F. Shirazi, and N. Hajli, “Consumers’ value co-creation in sharing economy: The role of social support, consumers’ ethical perceptions and relationship quality,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 151, p. 119786, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chai Y. Hao, H. Wu, and Y. Yang, “Do constraints created by economic growth targets benefit sustainable development? Evidence from China,” Bus. Strategy Environ., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 4188–4205, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Pfajfar, A. Shoham, A. Małecka, and M. Zalaznik, “Value of corporate social responsibility for multiple stakeholders and social impact–Relationship marketing perspective,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 143, pp. 46–61, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Dey, S. Bhattacharjee, M. Mahmood, M. A. Uddin, and S. R. Biswas, “Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 337, p. 130527, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Farooq, X. Liu, P. Fu, and Y. Hao, “Volunteering sustainability: An advancement in corporate social responsibility conceptualization,” Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 2450–2464, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Jilani, G. Yang, and I. Siddique, “Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior of the individuals from the perspective of protection motivation theory,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 13406, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. H. W. Chuah, D. El-Manstrly, M. L. Tseng, and T. Ramayah, “Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 262, p. 121348, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jian, I. Y. Yu, M. X. Yang, and K. J. Zeng, “The impacts of fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 on environmental concerns, brand trust, and behavioral intentions toward green hotels,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 20, p.8688, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. Iglesias, S. Markovic, M. Bagherzadeh, and J. J. Singh, “Co-creation: A key link between corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and customer loyalty,” J. Bus. Ethics, vol. 163, pp. 151–166, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Dwivedi et al., “Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy,” Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 57, p. 10 1994, 2021.

- S. Lins, K. D. Pandl, H. Teigeler, S. Thiebes, C. Bayer, and A. Sunyaev, “Artificial intelligence as a service: Classification and research directions,” Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng., vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 441–456, 2021.

- G. Santos, C. S. Marques, E. Justino, and L. Mendes, “Understanding social responsibility’s influence on service quality and student satisfaction in higher education,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 256, p. 12 0597, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Tuncer, C. Unusan, and C. Cobanoglu, “Service quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on behavioral intention in restaurants: An integrated structural model,” J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 447–475, 2021.

- D. E. Bock, J. S. Wolter, and O. C. Ferrell, “Artificial intelligence: Disrupting what we know about services,” J. Serv. Mark., vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 861–869, 2020.

- J. T. Davenport, A. Guha, D. Grewal, and T. Bressgott, “How artificial intelligence will change the future of marketing,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 48, pp. 24–42, 2020. [CrossRef]

- 158. P. Wang et al., “AR/MR remote collaboration on physical tasks: A review,” Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf., vol. 72, p. 102071, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Delgado, L. Oyedele, T. Beach, and P. Demian, “Augmented and virtual reality in construction: Drivers and limitations for industry adoption,” J. Constr. Eng. Manag., vol. 146, no. 7, p. 0402 0079, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Pencarelli, “The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry,” Inf. Technol. Tour., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 455–476, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. V. Misischia, F. Poecze, and C. Strauss, “Chatbots in customer service: Their relevance and impact on service quality,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 200, pp. 691–698, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Hilty et al., “A review of telepresence, virtual reality, and augmented reality applied to clinical care,” J. Technol. Behav. Sci., vol. 5, pp. 178–205, 2020,.

- D. H. Jonassen and C. S. Carr, Mindtools: Affording multiple knowledge representations for learning. Springer, 2020.

- J. R. Saura, “Using data sciences in digital marketing: Framework, methods, and performance metrics,” J. Innov. Knowl., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 92–102, 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).