1. Introduction

Vitex agnus-castus L., commonly known as chaste, is a small tree from the Verbenaceae family, native to the Mediterranean and Western Asia. Nowadays, it is cultivated worldwide. Its fruit, called chasteberry, vitex, monk's pepper, or VAC, extract is a popular herbal treatment, predominantly used for female reproductive conditions in Anglo-American and European practice [

1].

According to Van Die et al. [

1] and Verkaik et al. [

2], who systematically reviewed the treatment of premenstrual syndrome with preparations of chasteberry, studies have revealed that the consumption of this fruit extract might contribute to the well-being of women during premenstrual syndromes by alleviating some symptoms and improving life quality.

Some authors attribute these health benefits to phenolic compounds present in the chasteberry extract [

2,

3]. Others ascribe it mainly to casticin [

4]. In fact, casticin is a chemotaxonomic index for the genus Vitex, and it is also the major phytochemical in chasteberry fruit extract [

5]. However, at the moment, it is not explicit what compounds are presented in chasteberry extract that are responsible for its supposed women's health effect.

Regarding chasteberry consumption is generally restricted to pharmaceutical and health benefits, especially for disorders linked with the female reproductive system [

6]. The lack of functional products containing this chasteberry fruit or its extract, could instigate new searches and the development of other alternatives to consume this product. In fact, El-Nawasany, [

6] developed and evaluate stirred yoghurts containing (0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0% w/v) of Vitex agnus-castus (mainly the fruiting tops and leaves) dried and milled.

Although the production of this kind of product has a few limitations due to intense sensory characteristics, such as bitterness and spicy flavour, a manner to overcome those sensory aspects, which might be a problem, is the microencapsulation of chasteberry fruit extract. Therefore, the microencapsulation would minimise the fruit's and extract’s unpleasant sensory attributes and protect the antioxidant capacity of phenolic compounds from oxidation caused by unfavourable food processing and storage conditions such as high temperature, oxygen or/and light exposure, high pH, and high moisture content, among others.

Microencapsulation techniques produce small "packaging" called microcapsules, microspheres, or microparticles. The microstructure consists of one or more bioactive materials that are involved or immobilised by one polymer or more or a lipid [

7]. These structures have many functionalities, such as offering protection from adverse environmental conditions, masking, or minimising undesirable flavours.

In this way, the use of some encapsulation technologies for minimising undesirable sensory characteristics of food ingredients, such as the bitter taste of protein hydrolysate [

8,

9], astringent sensation, and intense cinnamon aroma of proanthocyanidin-rich cinnamon extract [

10,

11] have been studied already. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that a combination of spray-drying and spray-chilling technologies has been used for this purpose.

Several microencapsulation techniques are available for exploration: spraydrying, spray-chilling, ionic gelation, and complex coacervation. The spray-drying technology is based on the nebulisation of an emulsion, suspension, or solution in contact with hot air, which promotes rapid drying, transforming the droplets into particles. The spray-chilling technique, in its turn, is similar to the spray-drying process, but molten fat is used as an encapsulant. Then, it is atomised inside a cold chamber, promoting the mixture solidification and formation of particles. Both methods produce microparticles instead of microcapsules. The active material is dispersed throughout all the particle volumes rather than surrounded by an encapsulating material. However, with the combination of both techniques, it is expected that all the chasteberry compounds will keep inside the double-shell particles as a microcapsule, where they would be protected and their unwanted sensory effect masked. In addition, the microparticles release of the chasteberry extract occurs mainly in the intestine due to fat digestion, as demonstrated by Silva et al. [

12] performing a simulated digestion assay of phenolic compounds present in guarana seed extract encapsulated by the combination of spray-drying and spray chilling techniques. The authors observed that the release of phenolic compounds increased over time, but achieved the maximum release in the intestinal phase of the assay.

Some studies reported chocolate cravings during peri and premenstrual days [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. According to Michener et al. [

19], the chocolate craving during peri and premenstrual periods is probably justified because of its physiological basis. Chocolate is a dense source of calories and contains some known activating/arousing substances, such as caffeine and theobromine, and sympathomimetic amines, tyramine and phenylethylamine [

20]. In addition, it has anandamide and two analogues,

N-oleoylethanolamine and

N-linoleoylethanolamine, resulting in a calming and anxiolytic effect [

21]. Then, combining the desire to consume chocolate during this period and the benefits of chasteberry extract, free and microencapsulated chasteberry extract were added to dark chocolate.

Therefore, aiming to develop a functional, luxury and comfort food with the potential to minimise PMS symptoms, this study developed dark chocolate bars containing free and encapsulated chasteberry extract. Hence, chasteberry extract was spray-dried, and the particles were coated by spray-chilling. The particles were characterised by many parameters, including the stability of total phenolics and casticin during storage. Chocolates were also evaluated regarding the perception of extract bitterness and sensory acceptance.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ripe and dried fruits were obtained from Chá & Cia - Ervas Medicinais (São Paulo, Brazil). Arabic gum (Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltda., Brazil) and vegetable fat (Triangulo Alimentos, Itapolis, Brazil) with a melting point of around 45 °C, were used as carrier agents at the spray-drying and spray-chilling processes, respectively. For dark chocolate preparation, sugar (União, Brazil), cocoa liquor (Barry Callebaut, Brazil), cocoa butter (Barry Callebaut, Brazil), soy lecithin (Bunge, Brazil) and polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR, Danisco, Brazil) were used.

2.2. Production of Particles

The alcoholic extract of chasteberry was prepared according to Barrientos et al. [

22] and concentrated until 20 g of solids per 100 g of extract using a rotatory evaporator at 45 °C. Then, the concentrated extract was added to Arabic gum in 5 g/100 g extract concentrations. Finally, this feed material was atomised using spray-dryer equipment (Model MSD 1.0, Labmaq, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil) at operational conditions described by Barrientos et al. [

22]. Subsequently, the spray-dried powder (5, 10 and 15 g) was blended with 50 g of a vegetable fat (previously melted at 60 °C). These blends were atomised using the same operational conditions as spray-drying, except for the inlet air temperature, set at 14 °C. For producing a control, the concentrated extract without any carrier (as Arabic gum) was spray-dried in the same conditions. This material was used for dark-chocolate production and were call free extract (FC).

2.3. Characterisation of Powders and Their Particles

The powders obtained by combining spray-drying and spray-chilling techniques were stored at 25 °C with 38% relative humidity (RH). Analyses of water content, water activity, particle size, X-ray diffraction, the morphology of the particles by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and thermogravimetric were performed, aiming to characterise the powders. In addition, the study of the stability of phenolic compounds and casticin were evaluated during 120 days of storage. All analyses were executed in triplicate.

2.3.1. Moisture and Water Activity (Aw)

The moisture of the powders was determined using a moisture analyser (Ohaus, model MB 35, Ohio, USA). The water activity of the powders was obtained using the AQUALAB equipment (Decagon Devices, Pullman, USA). Both data were collected at day zero, in other words, on the same day as the extract was encapsulated and after 120 days of storage at 25 ºC and 38% RH, with the presence of oxygen but no light.

2.3.2. Particle Sizes

The particle sizes were analysed according to Salvim et al. [

23] by laser diffraction (Sald-201V, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The samples were dispersed in absolute ethanol, and the particle sizes were expressed as the De Brouckere mean diameter (D4,3). The sample analyses were performed on the same day of encapsulation and after 120 days of storage at 25 ºC and 38% RH, with presence of oxygen but no light.

2.3.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Polymorphic forms of the powders were evaluated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using a AXS Analytical X-Ray Systems Siemens D5005 (Germany). The powders were scanned from 5° to 55° of 2θ, at 3°/min, as described by Xiao et al. [

24].

Analyses were performed at day zero and after 120 days of storage at 25 ºC and 38% RH, with the presence of oxygen but no light.

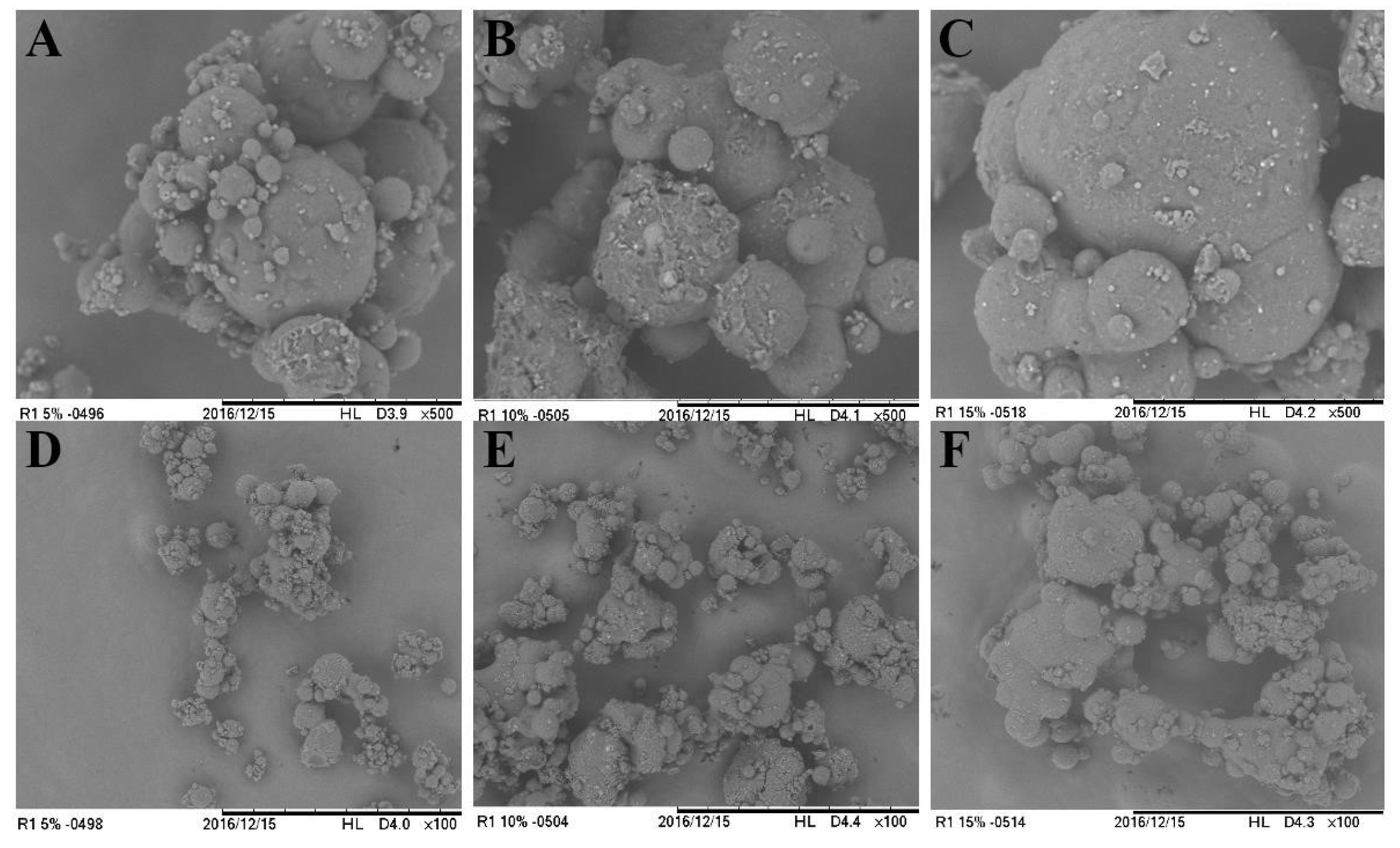

2.3.4. Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of particles was evaluated by scanning electronic microscopy. It was executed by using a TM3000 Tabletop Microscope (Hitachi, Japan) at 500x or 100x magnification, without covering the microparticles with gold.

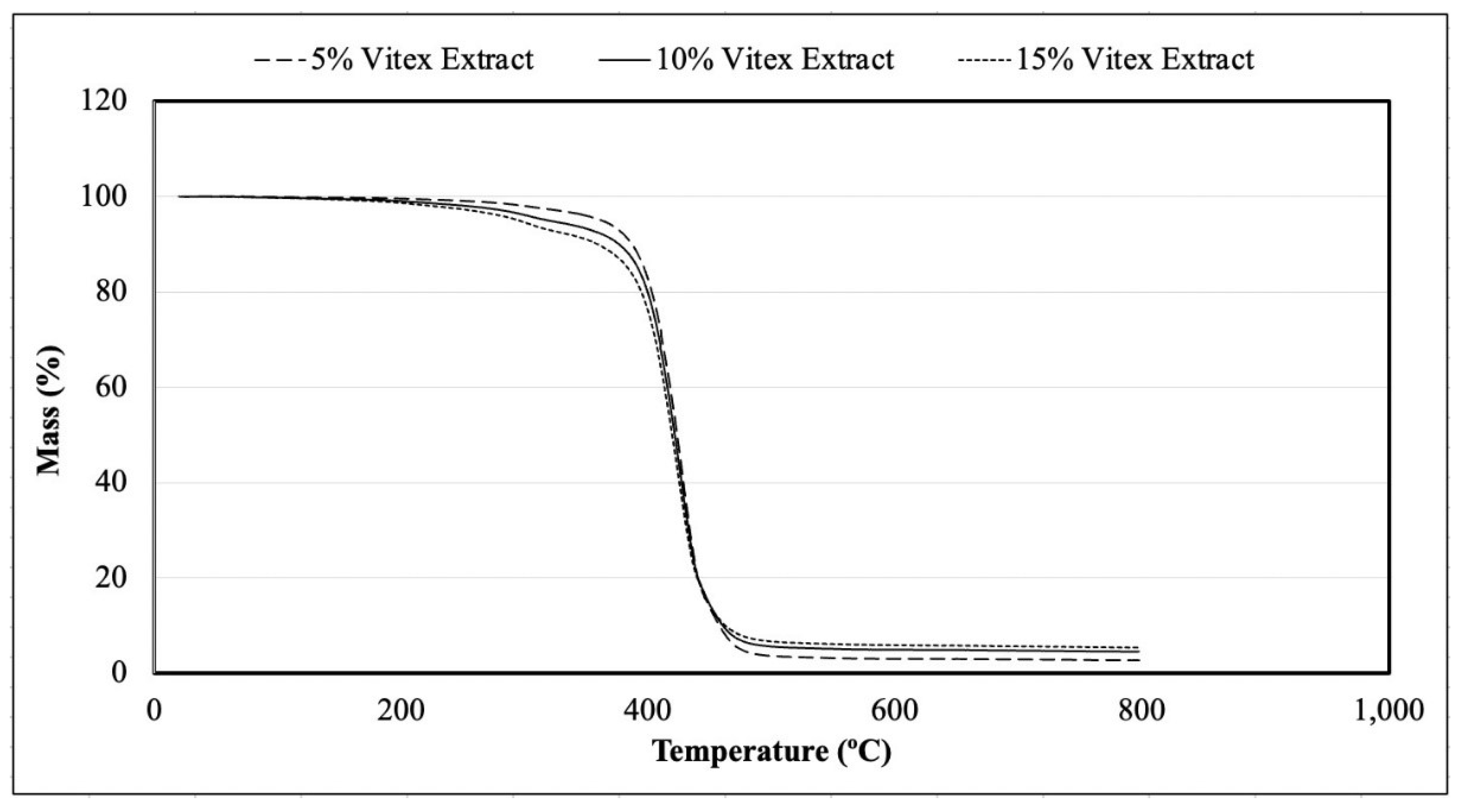

2.3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis of the Powders

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed in the Schimadzu TGA-50 equipment (Japan), calibrated at a heating ratio of 10 °C/min, with high purity calcium oxalate monohydrate.

2.3.6. Total Phenolic Compounds of the Powders

Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used to quantify the phenolic compounds in the powders. They were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry matter of powder, according to Singleton et al. [

25], with modifications. Thus, the reaction mixture was prepared with 0.25 mL of sample, 2 mL of distilled water, and 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After 3 min at room temperature, 0.25 mL of saturated Na

2CO

3 aqueous solution were added to the reaction mixture, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a water bath for 30 min for colour development. The absorbance was measured at 750 nm (Ultrospec 2000, Pharmacia Biotech), and a standard curve of gallic acid was used to determine the total phenolic concentration.

The results were expressed as mg GAE/ g (mg of gallic acid/g of sample) in dry basis.

2.3.7. Casticin Quantification in the Powders by HPLC

The quantification of casticin was performed according to Hoberg et al. [

5] using a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system, model Prominence, with a diode array detector. The column oven was kept at 30 °C, and 10 µL of the sample diluted in methanol was injected into the equipment. Separations were conducted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and the mobile phase was composed of methanol

(A) and 0.5% phosphoric acid solution (B), applied in a gradient as follows (A:B): from 0-13 min (50:50), 13 min (65:35), 13.1-18 min (100:0), 18-23 min (50:50).

Chromatograms were acquired at 256 nm.

The results were expressed as µg casticin/g of sample (in dry basis).

2.3.8. Evaluation of the Stability Of Total Phenolic Compounds And Casticin

Encapsulated extract of chasteberry was portioned in glass vials with plastic lids. They were stored in a controlled environment (25°C and 38% RH), with the presence of oxygen, but protected from light for 120 days. The total phenolic content and casticin were evaluated according to items 2.3.6 and 2.3.7, respectively, at day zero and after 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 days of storage.

2.4. Production of Dark Chocolate Added of Chasteberry Extract Free and Encapsulated

The production of dark chocolate bars containing free and encapsulated chasteberry extract was performed using the conventional manufacturing system. The samples were prepared at the Ceral Chocotec pilot plant - Instituto de Tecnologia de Alimentos (Campinas, Brazil) using the following composition: 47% sugar (w/w), 40% cocoa liquor (w/w), 10% cocoa butter (w/w), 0.3% soy lecithin (w/w), 0.2% PGPR (w/w) and 2.5% (w/w) of free chasteberry extract (plus Arabic gum and vegetable fat in the same proportion that they were in the encapsulated extract) or encapsulated chasteberry extract.

Before refining, the ingredients were mixed in an agitated jacketed tank (Inco, Germany) with water circulation maintained at 45 °C. After total melting of the lipid phase and complete homogenisation, the mixture was processed in the five vertical roll refiner (JAF Inox, Duyvis Wiener, Brazil), cooled by a chiller (MeCalor, São Paulo, Brazil), and maintained at a temperature of 7 °C ± 1 °C. First, the pressure between the cylinders was adjusted to obtain maximum particle sizes smaller than 28 µm, and measurements were performed using a digital micrometre. Then, the blend was conched at 65 °C in a homogenising conching machine (JAF Inox, Duyvis Wiener, Brazil), set up to carry out the stages of dry conching (4 hours, 60 Hz), plastic conching (19.5 hours, 60 Hz) and liquid conching, with the addition of emulsifiers (30 minutes, 30 Hz). Next, the chocolate was tempered or pre-crystallised in a bench top tempering machine (ACMC, New York, United States), starting at a temperature of 40°C and cooled down to the temperature of 28 °C, at a cooling rate of 2 °C/minute, ideal for obtaining the crystal in the Beta V polymorph. The free and microencapsulated chasteberry extracts were added to the product during the tempering stage when the chocolate temperature reached 35°C aiming to preserve the microparticle integrity. After that, the pre-crystallised chocolate was poured into polycarbonate moulds, and air bubbles were removed by vibration. Finally, chocolate bars were crystallised in a cooling tunnel (SIAHT) operating with a temperature range for the inlet and outlet of 15-17°C and 11-13°C in the middle of the tunnel. These temperature conditions allowed the lipid matrix consolidation in the Beta Form, giving the chocolate the desired physical properties (hardness and melting).

After the cooling process, the samples were unmoulded, wrapped in aluminium foil and stored in a BOD oven (ELETROlab®, São Paulo, Brazil) at a controlled temperature (19 °C ± 1 °C) and protected from light and humidity to allow the complete formation of crystal lattice desirable in chocolates.

It is essential to mention that three treatments were prepared: one containing the encapsulated powder produced according to item 2.2 (15 g of spray-dried extract per 50 g of vegetable fat); the control, in which there was no addition of extract or vegetable fat; and the last treatment was composed by the free extract and carriers agents used to produce the encapsulated extract (Arabic gum and vegetable fat, in the same proportion as particles, but mechanically mixed into a powder).

Note that a previous study obtained the free extract through a spray-drying process without any carrier addition [

22].

The chocolate with encapsulated and free chasteberry extract was named “EC” and “FC”, respectively.

2.4.1. Stability of Casticin and Total Phenolic in Chocolates

The stability of phenolic compounds and casticin in chocolates wrapped with aluminium foil and stored at 22 °C were monitored over 0, 7, 15, 30, 45, and 60 days of storage, using the methods of quantification previously described on items 2.3.6 and 2.3.7, respectively. Nonetheless, for the extraction of phenolic compounds and casticin, the sample was first degreased and then extracted with an 80% (v/v) ethanol solution, as described by Adamson et al. [

26] and Alanón et al. [

27]. Thus, 3 g of ground chocolate sample was mixed with 10 ml of n-hexane, homogenised using a vortex, placed in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min, and centrifuged (2935 x g for 5 min). The procedure was repeated, but adding only 5 mL of n-hexane. Following, the samples were dried to remove residual n-hexane. The extraction was performed twice to maximise the release of total phenolic compounds and casticin. This way, 2.5 mL of alcoholic solution (80% v/v) was added to the chocolate that was previously defatted. The mixture was homogenised by vortexing, and then using an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. Finally, the mixture was centrifuged (2935 x g for 5 min), totalling 5 mL of the final extract. For the quantification of casticin, the extract was filtered, while for phenolic compounds measurements, the chasteberry extract was diluted in a ratio of 0.8:10 in an 80% (v/v) ethanol solution.

2.4.2. Chocolate Sensorial Analyses

Two paired comparison tests (two-tailed) were performed, according to Meilgaard et. al [

28], to evaluate the efficiency of the microencapsulation process in masking or attenuating the bitterness and burning sensation caused by the chasteberry extract. The research ethics committee approved the sensory evaluation study of the institution, the protocol number (CAAE 56690216.2.0000.5422) and all panellists signed the consent form.

In the first test, the panellists were previously selected according to their acuity in the perception of the sensation of spicy (15 participants) and bitterness (17 panellists). They were asked to compare the following samples: i) sample containing the encapsulated extract; ii) sample containing free freeze-dried extract and the encapsulating agents in the same proportion as they appear in the particles, but mechanically mixed into a powder.

The second test was performed with the same group of panellists but using the chocolates obtained according to item 2.4. The selected participants tasted the samples EC and FC. The chocolates were served on trays, inside coded 50 mL plastic cups, along with a glass of water and a biscuit. Then, the panellists could clean their palates between each trial.

The sensory acceptance of the chocolates was also carried out, according to Meilgaard et al. [

28], with a group of 122 untrained women aged between 18 and 60 years. The samples (control, EC, and FC) were presented in the same conditions as the previous test, and the product acceptance was assessed using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 - "Dislike extremely" and 9 - "Like extremely") for the attributes of flavour, texture, colour, aroma, and overall acceptability. In addition, to evaluate the product's purchase intention, a 5-point scale, where 1 represented "Definitely do not buy" and 5 meant "Definitely buy", was used.

The acceptance index (AI) was calculated using the average score obtained considering all the averages of the analysed attributes divided by the maximum score of the hedonic scale (9) multiplied by 100 [

29].

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, considering significant differences when p<0.05 (SAS software, version 9.2).

4. Conclusions

The microencapsulation techniques applied to chasteberry extract proved to be efficient for protecting casticin, one of the compounds related to relieving PMS symptoms; however, it was inefficient to protect the total phenolic content. In addition, the microencapsulation proved to be effective in attenuating the extract burning sensation and bitterness even though the chocolates with the encapsulated material had lower acceptance in texture parameters than the chocolate containing the free-form extract. Therefore, a solution to improve the texture parameter could be the addition of solid aggregates, such as nuts and crispy rice, or other compounds like dried fruits, after the tempering process to give a different texture to the product and minimise this problem. Furthermore, as the general acceptance and purchase intention of chocolates produced with chasteberry in free form were close to the chocolate containing microparticles loaded with chasteberry extract, it would be recommended to produce this functional chocolate without the further step of encapsulation through spray-chilling. Although, this encapsulation process is useful for preserving the extract bioactive compounds and could be convenient for applying this material in a product less naturally bitter than dark chocolate, such as yoghurt, fermented milk, and cereal bars. In short, prioritising the addition of the chasteberry extract obtained only by spray-drying would result in a cheaper and faster process. In addition, the product would still offer phytotherapeutic benefits from casticin to women during their premenstrual syndrome or menopause period.

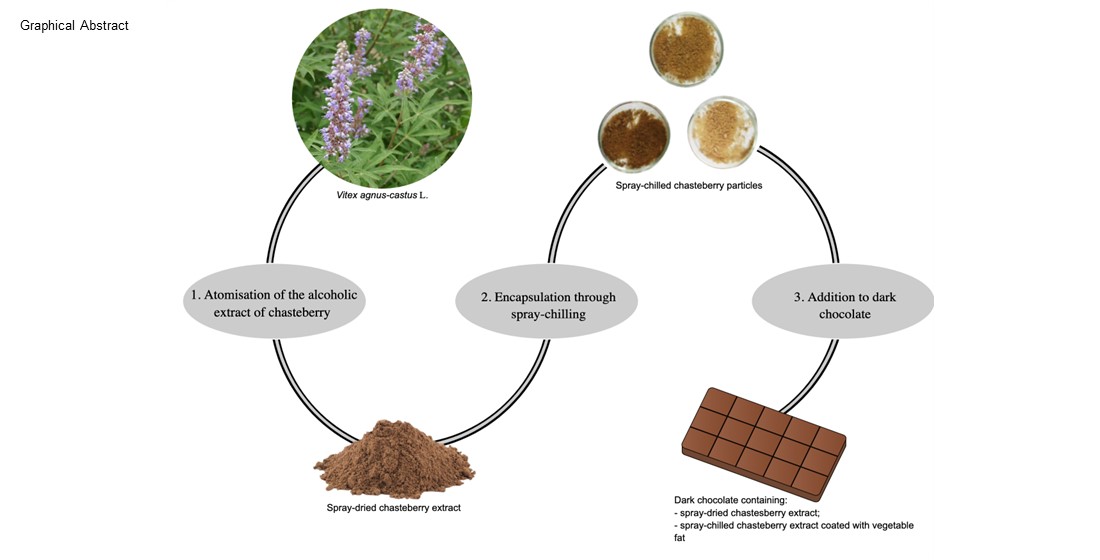

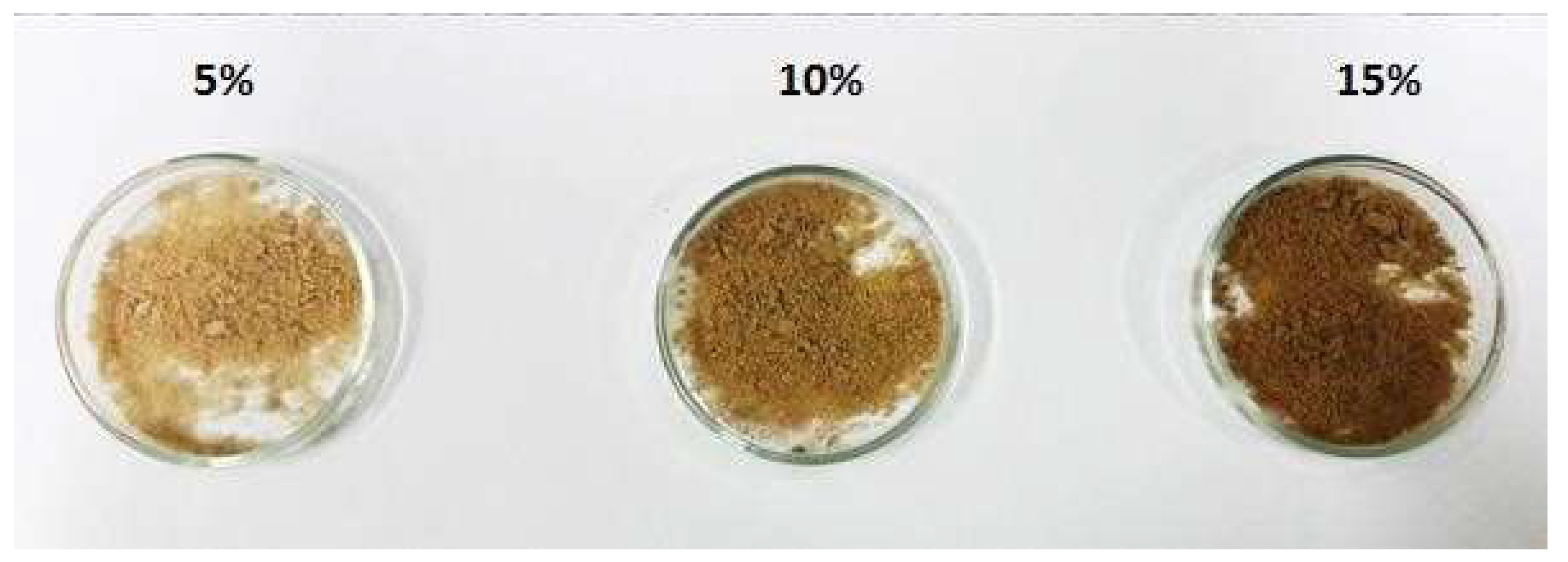

Figure 1.

The appearance of powders produced by spray-drying and coated by spraychilling, using 5, 10 and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Figure 1.

The appearance of powders produced by spray-drying and coated by spraychilling, using 5, 10 and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

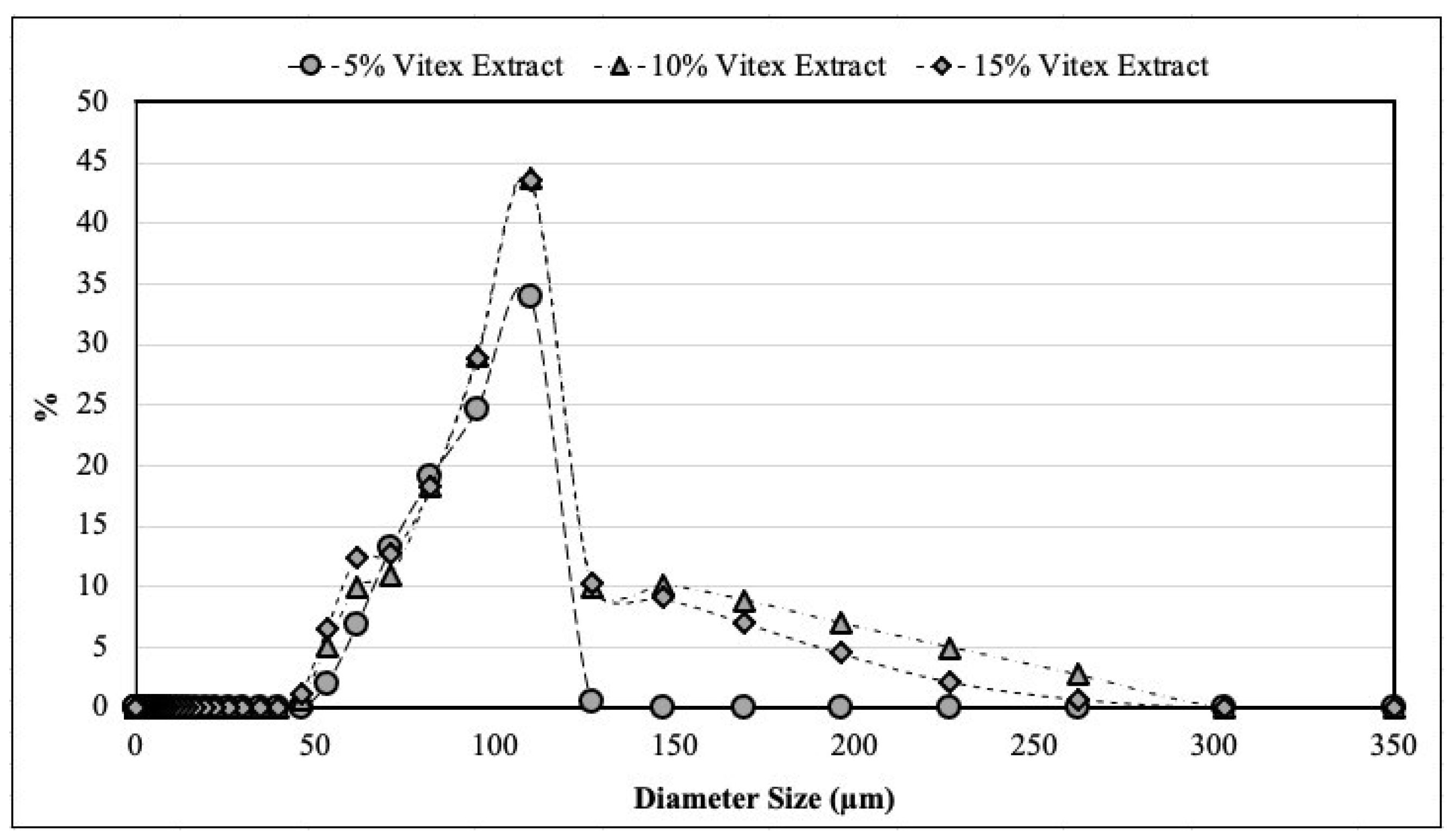

Figure 2.

Size distribution of microparticles produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling, using 5, 10 and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Figure 2.

Size distribution of microparticles produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling, using 5, 10 and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

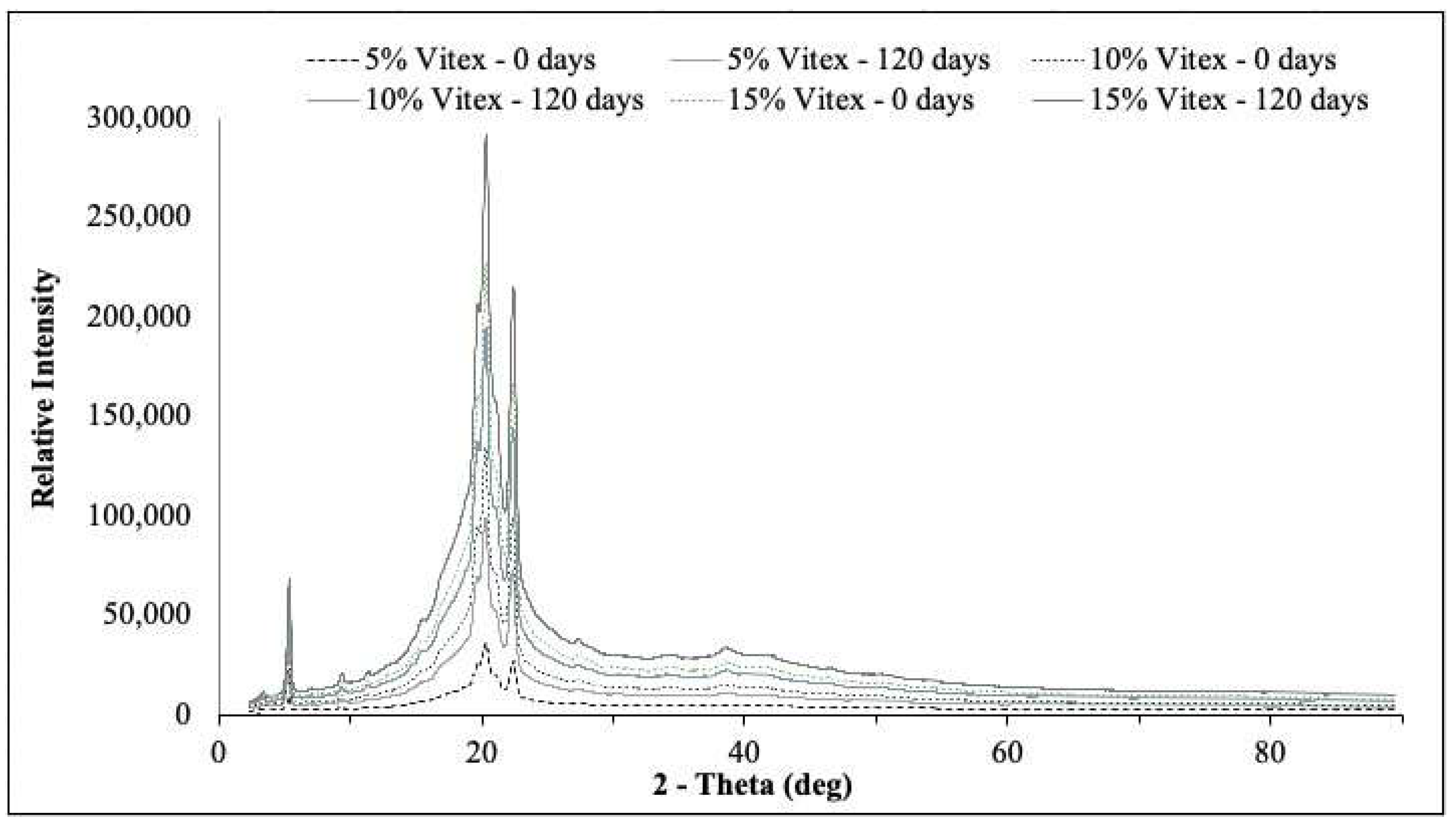

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractograms of powders produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling with 5, 10, and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractograms of powders produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling with 5, 10, and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Figure 4.

Scanning electronic micrographs (500x and 100x magnification) of particles produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling; A) Particles produced with 5 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; B) Particles produced with 10 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; C) Particles produced with 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; D) Particles produced with 5 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat 100x magnification; E) Particles produced with 10 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat 100x magnification; F) Particles produced with 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat – 100x magnification.

Figure 4.

Scanning electronic micrographs (500x and 100x magnification) of particles produced by spray-drying and coated by spray-chilling; A) Particles produced with 5 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; B) Particles produced with 10 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; C) Particles produced with 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat and 500x magnification; D) Particles produced with 5 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat 100x magnification; E) Particles produced with 10 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat 100x magnification; F) Particles produced with 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat – 100x magnification.

Figure 5.

Mass variation according to the temperature applied in samples produced with 5, 10, and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Figure 5.

Mass variation according to the temperature applied in samples produced with 5, 10, and 15 g of spray-dried chasteberry extract per 50 g of vegetable fat.

Table 1.

Content of total phenolics (mg GAE/g) in solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 5, 10 and 15%, for up to 120 days of storage.

Table 1.

Content of total phenolics (mg GAE/g) in solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 5, 10 and 15%, for up to 120 days of storage.

| Days |

5% |

10% |

15% |

| 0 |

5.7 ± 0.7 Ba |

5.6 ± 1.1 Aa |

6.5 ± 0.4 Aa |

| 15 |

2.6 ± 0.1 Cbc |

4.5 ± 0.4 Bb |

6.0 ± 0.3 Aab |

| 30 |

2.6 ± 0.2 Cbc |

4.6 ± 0.1 Bb |

5.7 ± 0.7 Aab |

| 60 |

2.5 ± 0.4 Cbc |

3.4 ± 0.5 Bc |

5.2 ± 0.4 Ab |

| 90 |

2.1 ± 0.5 Cc |

4.2 ± 0.4 Bbc |

5.3 ± 1.0 Ab |

| 120 |

2.7 ± 0.6 Cbc |

4.4 ± 0.6 Bbc |

6.0 ± 0.2 Aab |

Table 2.

Content of casticin (µg casticin/g of sample) in solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 5, 10 and 15%, for up to 120 days of storage.

Table 2.

Content of casticin (µg casticin/g of sample) in solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 5, 10 and 15%, for up to 120 days of storage.

| Days |

5% |

10% |

15% |

| 0 |

21.0 ± 6.0 Ba |

32.5 ± 14.5 Ba |

47.0 ± 5.1 Aa |

| 15 |

19.5 ± 2.5 Bab |

34.7 ± 9.4 Ba |

45.6 ± 11.7 Aa |

| 30 |

14.9 ± 2.4 Cab |

30.4 ± 3.7 Ba |

51.9 ± 3.0 Aa |

| 60 |

13.4 ±3.1 Bbc |

33.0 ± 5.1 Aa |

41.1 ± 12.5 Aa |

| 90 |

11.9 ± 2.9 Cc |

29.6 ± 2.8 Ba |

44.7 ± 5.9 Aa |

| 120 |

14.9 ± 3.3 Bbc |

32.5 ± 3.6 Aa |

39.1 ± 15.6 Aa |

Table 3.

Content of total phenolics (mg GAE/ g) in chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC) for up to 60 days of storage, compared to the control chocolate. Solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 15% were applied to the chocolate (EC).

Table 3.

Content of total phenolics (mg GAE/ g) in chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC) for up to 60 days of storage, compared to the control chocolate. Solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 15% were applied to the chocolate (EC).

| Days |

Control |

EC |

FC |

| 0 |

7.8 ± 0.1 Aa |

7.8 ± 1.2 Aab |

7.4 ± 0.5 Ab |

| 7 |

7.0 ± 0.6 Aa |

6.5 ± 1.0 Ab |

6.0 ± 0.8 Ac |

| 15 |

8.0 ± 0.4 Aa |

8.3 ± 0.6 Aa |

8.5 ± 1.0 Aa |

| 30 |

4.3 ± 0.1 Ab |

3.0 ± 1.0 Bcd |

4.6 ± 0.3 Ad |

| 45 |

3.5 ± 1.8 Abc |

4.4 ± 0.4 Ac |

4.6 ± 0.07 Ad |

| 60 |

2.6 ± 1.1 Ac |

2.2 ± 0.7 Ad |

2.2 ± 0.3 Ae |

Table 4.

Content of casticin (µg casticin/ g) in chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC) for up to 60 days of storage. Solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 15% were applied to the chocolate (EC).

Table 4.

Content of casticin (µg casticin/ g) in chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC) for up to 60 days of storage. Solid lipid microparticles produced by spray chilling and loaded with spray dried chasteberry extract at concentrations of 15% were applied to the chocolate (EC).

| Days |

EC |

FC |

| 0 |

7.6 ±0.6 Aa |

5.6 ± 0.2 Ba |

| 7 |

6.9 ± 0.3 Aab |

5.0 ± 0.2 Ba |

| 15 |

5.5 ± 0.4 Ac |

4.9 ± 0.2 Aa |

| 30 |

6.1 ± 0.6 Abc |

4.6 ± 0.5 Ba |

| 45 |

5.4 ± 0.4 Ac |

5.3 ± 0.8 Aa |

| 60 |

5.7 ± 0.5 Abc |

5.1 ± 0.4 Aa |

Table 5.

Results for sensorial analyses of chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC), as well as powders produced the encapsulated extract (EC) and with the spray-dried extract, vegetable fat and Arabic gum (exactly in the same proportion as these appear in the formulation, but mechanically mixed - FC). The panelists were previously selected according to their acuity in the perception of the sensation of spicy (15 panelists) and bitterness (17 panelists).

Table 5.

Results for sensorial analyses of chocolates with free (FC) and encapsulated chasteberry extract (EC), as well as powders produced the encapsulated extract (EC) and with the spray-dried extract, vegetable fat and Arabic gum (exactly in the same proportion as these appear in the formulation, but mechanically mixed - FC). The panelists were previously selected according to their acuity in the perception of the sensation of spicy (15 panelists) and bitterness (17 panelists).

| |

Powder |

Chocolate |

| |

Bitterness Spicy |

Bitterness Spicy |

| FC |

17 13 |

10 11 |

| EC |

0 2 |

7 4 |

Table 6.

Average grades assigned by panellists to the attributes of flavour, aroma, texture, colour, overall acceptability, overall average, and purchase intentional for the different formulations of chocolate.

Table 6.

Average grades assigned by panellists to the attributes of flavour, aroma, texture, colour, overall acceptability, overall average, and purchase intentional for the different formulations of chocolate.

| Chocolate Overall Acceptance Purchase Flavour Aroma Texture Colour Overall Sample acceptability index (%) intention average |

Control 8 ± 1A 8 ± 1A 8 ± 1A 8 ± 1A 8 ± 1A 8 88,9% 5 ± 1A

EC 7 ± 2B 7 ± 1B 6 ± 1C 8 ± 1B 7 ± 2B 7 78% 3 ± 1C

FC 7 ± 2B 7 ± 1B 7 ± 2B 8 ± 1B 7 ± 2B 7.2 80% 4 ± 1B |