1. Introduction

Eukaryotic cells use a tiny cell membrane protrusion called the primary cilium to communicate with environment [

1,

2,

3]. It plays a vital role in cell sensing and signaling and defects in the state of primary cilia have been associated with various diseases, collectively known as ciliopathies [

4,

5]. The primary cilium is a dynamic cellular organelle during cell cycle. It is resorbed before cells enter mitosis and reformed after cells exit mitosis [

6]. Thus, primary cilia are viewed as a structural barrier to mitosis [

7]. Cancer cells have a low ciliation rate which allows them to undergo rapid cell division and replication. It has been postulated that restoring primary cilia in cancer cells may decelerate cilia retraction and cancer cell replication. There has been much interest in finding methods, particularly drugs and small molecule inhibitors, to increase the ciliation frequency and lengthen primary cilia in cancer cells in order to slow their cell cycle and proliferation.

We attempted a comprehensive literature review in the field of cilia biology in order to identify promising candidate drugs that can be further tested on the wet bench. The traditional literature review process consists of multiple steps, beginning from searching scientific literature databases to filtering inclusion criteria to manual confirmation of results [

8]. For us, conducting a traditional literature search would be unfeasible, given the great rise in the volume of articles related to primary cilia. We would have to filter through hundreds of thousands of loosely related articles, nearly guaranteeing that we misread or ignore crucial information. A solution to the issue of a slow, non-thorough manual search is the development of web scrapers, in which computer programs “scrape” websites (in this case, scientific literature databases) to perform a more comprehensive review. Web scrapers gained popularity particularly in the late 1990s alongside the emergence of Python and accompanying packages such as Beautiful Soup to broaden the accessibility of data mining tools [

9]. The user will often provide the search parameters for the program to use, and a certain logic flow of keywords to narrow in on exactly what they want to retrieve. For our scenario, we would want to create a scraper that could parse through a vast, reputable database such as PubMed to retrieve a smaller subgroup of relevant articles. This process can drastically narrow down gigantic databases to relevant search results, but all those articles still must be manually processed for the relevant information, a step which especially for larger scale searches can take several weeks or longer.

Recently, many of the popular Large Language Models, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, have released their APIs, providing the backbone of their model for integration into other applications for a very reasonable price [

10]. As a result, there has been an influx using those models far beyond the original purpose of a chatbot, ranging from educational tools [

11] to programming assistants [

12]. However, the use of these models to accelerate the efficiency of literature searches is one direction that has not yet been explored in depth. One of the primary limitations of a web scraper is that once the articles are returned, a manual review must be conducted, consisting of thorough analysis for each publication. This process is monotonous and time-consuming. We thus proposed an AI-powered solution whereby scraped articles are automatically run through the large language model to be searched for the answers to user-predefined questions. This would make it so a researcher could see exactly what they are searching for, with relevant information automatically extracted and summarized. Afterwards, the researcher would merely have to parse through these shortened and specified results. This approach would automate multiple steps of the literature review process, greatly increasing efficiency of research (

Table 1).

Using this LLM-integrated scraper is in theory a very attractive solution, but many questions remain. Does the time that the large language model takes to process each of the articles and generate responses to each of the questions less than the time it would take for a human to review the articles? Perhaps more importantly, does the quality and accuracy of the automated results show true potential to advance research in biomedical fields? For us specifically, we wanted to test whether the drug(s) parsed via this method would induce a significant increase in ciliogenesis to therefore reduce the replication of cancer cells.

2. Methodology

2.1. LLM-Integrated PubMed Scrapper

The primary package that we used to code the scraper was BeautifulSoup. We fed the program the URL to PubMed, and within that we included the specific search parameters for the retrieval of specific articles. The package also includes functions to query defined aspects of each article, such as their DOI link, abstract, title, and authors. These attributes were each saved to variables. For the large language model portion, we first fed the program our OpenAI API key. Then we call a function to the API which requires a “SystemMessage”, which is the question the user defines, and the “HumanMessage” which is the article text that we feed the model. We finally use the xlsx package to transfer the results for each article stored into the variables to an organized Excel file, which is ultimately returned to the user.

2.2. Imaging and Quantification of Primary Cilia

Cancer cell lines DAOY (medulloblastoma) and A549 (lung adenocarcinoma) was maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum. To image primary cilia, cells were grown on gelatin-coated coverslips, fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed in PBS, and then permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. After one hour in blocking buffer (3% goat serum, 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS), cells were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight followed by rinses in PBS and one hour incubation with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies. After multiple rinses, slides were mounted in antifade reagent containing DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for imaging via a confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy 700 from ZEISS (Chester, VA, USA) at the UVA Advanced Microscopy Facility. Arl13B rabbit polyclonal antibody (17711-1-AP) and γ-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody (66320-1-Ig) were from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 488) antibody (ab150081) and goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 594) antibody (ab150120) were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

The Zen 2009 program was used with a confocal Laser Scanning Microscope 700 from ZEISS to collect z stacks at 0.5 μm intervals to incorporate the full axoneme based on immunostaining of cilia marker Arl13b and basal body marker γ-Tubulin. All cilia were then measured in ImageJ [

13] via a standardized method based on the Pythagorean Theorem in which cilia length was based on the equation L2 = z2 + c2, in which “c” is the longest flat length measured of the z slices and “z” is the number of z slices in which the measured cilia were present multiplied by the z stack interval (0.5 μm).

2.3. Drug Treatment and Crystal Violet Assay for Cell Viability

Alvocidib (Cat# S2679) and Alisertib (Cat# S1133) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA) and dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM. Cancer cells plated in 6-well plates were incubated with medium containing Alvocidib and/or Alisertib at a final concentration of 100 nM and 1 µM, respectively. Three days post drug treatment, floating/dead cells were removed with medium and adherent/live cells left on the plates were stained with crystal violet dye (Cat# C6158) from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA, USA). After extensive rinses, cells were lysed and dyes in the lysis buffer were quantified by spectrophotometer [

14].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

ANOVA tests were used to analyze the experimental data, with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered significant. When ANOVA tests deemed data to be significant, post-hoc Tukey HSD tests were conducted to compare group means and determine the significance of all possible experiment group pairings. This analysis was performed with alpha values of both 0.05 and 0.01.

3. Results

Our main objective was to identify drugs via a new LLM-integrated web scraper that could increase rates of ciliogenesis in cancer cells, thus slowing their proliferation. The study was conducted in three primary steps: 1. We used literature review tools to perform a comprehensive sweep of existing related publications to select the top drugs that show the most promise in promoting ciliogenesis; 2. We validated the effects of such drugs on cilia length and ciliation rates in cancer cells; 3. We evaluated the impacts of such drugs, both individually and in combination, on cancer cell viability.

3.1. An Intelligent Literature Search by LLM-Integrated Scraper

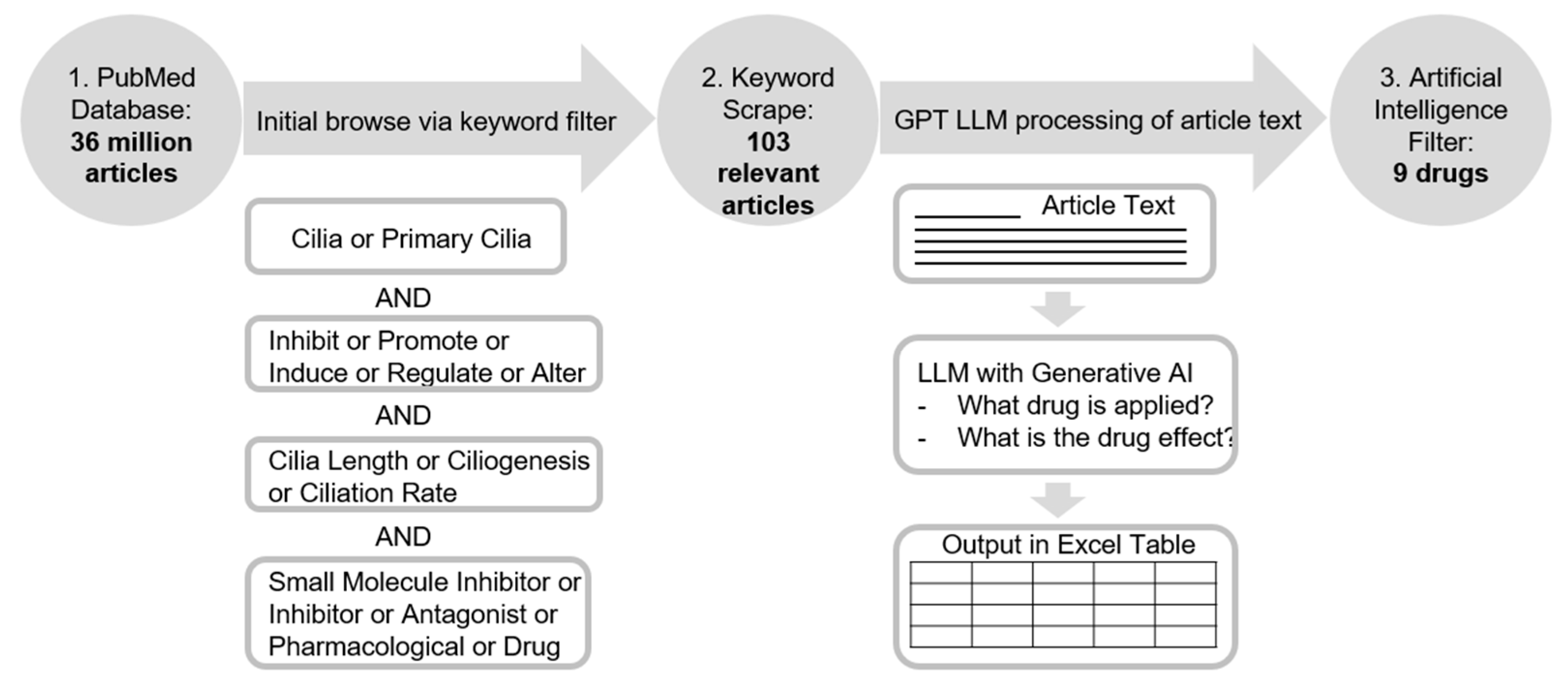

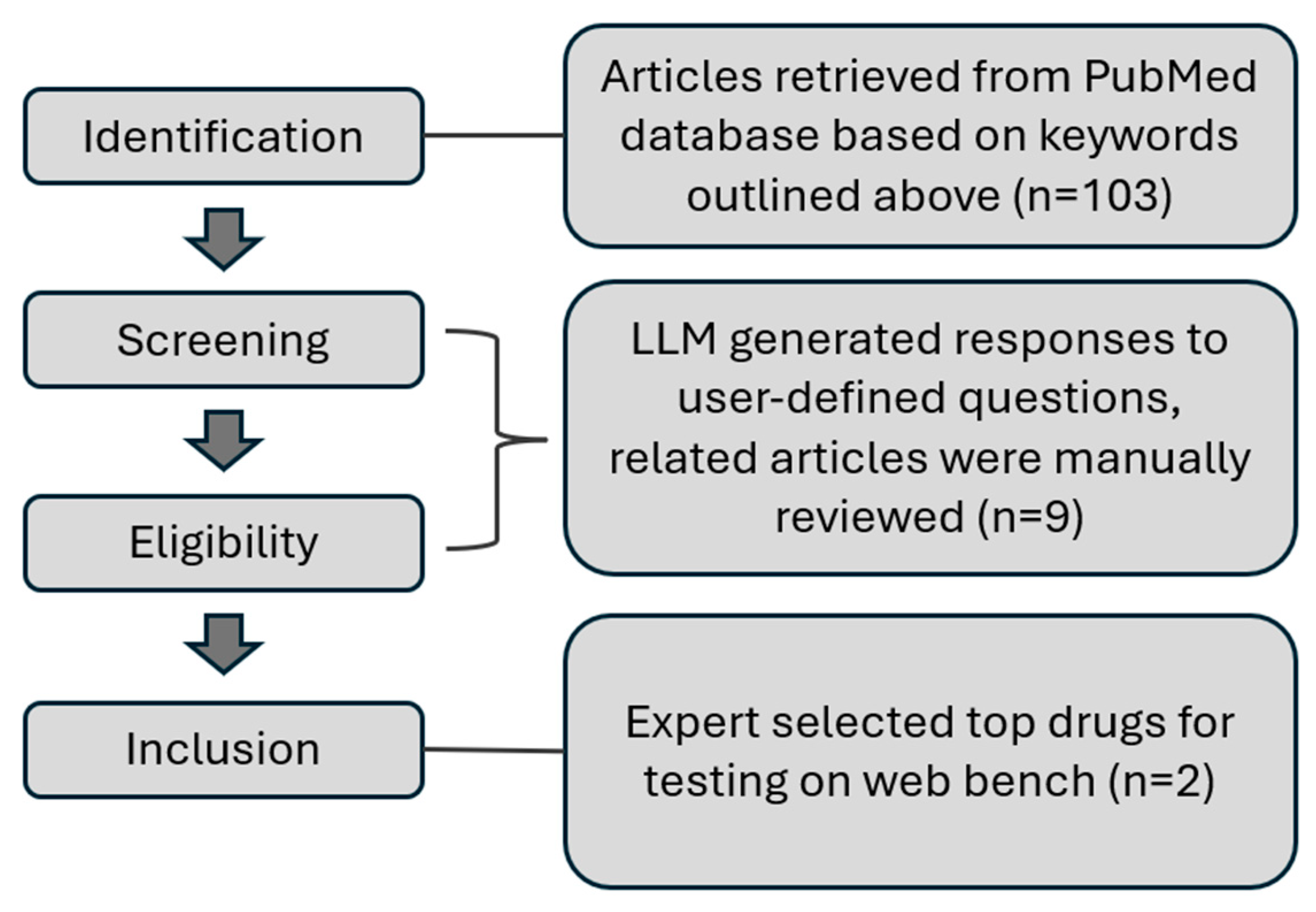

Due to the extensive literature on scientific databases, it is challenging to execute a wide search that can encompass all the potential articles related to promoting ciliogenesis manually. Parsing through articles by hand is draining, incomprehensive, and slow, and severely limits the scope of the drugs that can be discovered. To combat such an issue, we utilized a PubMed scraper we built around the Beautiful Soup package in Python and integrated within the GPT-3.5 API to query specific articles. The scraper operated in two distinct phases: 1. Find all relevant articles on the PubMed database using the user-provided keyword parameters; 2. Answer predefined questions using an integrated Large Language model (

Figure 1).

The first step involved optimizing the keyword search which was achieved by testing different combinations of related terms such as “ciliogenesis” “drug” or “lengthen”. The flexibility of adjusting the keywords as well as where they had shown up, such as the Abstract, Title, or MeSH Terms gave us multiple combinations to test, after each of which we analyzed the relatedness of the resulting articles to narrow or broaden our search as necessary. We opted for generally broader search terms as we would much rather have unrelated articles that we can manually process after the scraper runs than have related articles that are never returned due to the specificity of terms. After experimentation, the keyword logic below was decided as the finalized version (

Figure 1). Articles had to contain at least one keyword from each column. Variations of each word were also considered (i.e., inhibits, inhibited). This initial step of extracting articles via keyword search served as a preliminary filter to create a smaller subgroup of related articles, since running the Large Language Model on the entire PubMed database would be unfeasible and a waste of resources due to the majority of articles on the website being unrelated to what we wanted to study. Additionally, during this step, the scraper extracted the basic information for each article, such as the publication date, authors, and abstract.

The second step was to use the integrated GPT-4 Large Language Model to answer questions about each of the articles chosen by the initial keyword search. The specific questions we asked were, “What is the name of the drug?”, “What is the target of the drug?”, and “What effect(s) does the drug have on the target and primary cilia?”. Through such inquiries and the text of each of the selected publications, the scraper was able to automatically generate accurate answers, thus reducing the need for an in-depth manual analysis of each paper to only a confirmation of scraper results. Each article from the initial keyword-selected group, along with its basic information and answers to the questions as provided by the LLM, was automatically converted to an organized Excel table format accessible immediately after the scraper finished running (

Figure 1). Every row was a different article, and the columns denoted everything from the basic information about each paper to their LLM-generated answers.

3.2. Alvocidib and Alisertib Identified as Promising Cilia-Promoting Drugs

After optimizing the search terms, our ultimate scraper run returned an initial group of 106 articles and took just under an hour to process those articles and return the Excel file. While conducting the search, we ensured that all privacy policies were adhered to. Excluded from the search were preprints and retracted articles, leaving only open access publications accessible on PubMed. We manually parsed through the Excel document, ensuring that all articles were related to primary cilia and marking the ones that were not. We then browsed through the answers provided by the LLM to the previously listed questions and looked specifically for drugs that targeted different pathways controlling ciliogenesis. For the drugs that showed the most promise (

Table 2), we manually processed the article to ensure that all summarization information was accurate. The entire article was read to get the best idea of the mechanisms of the drug and anything else noteworthy that we did not explicitly ask for. Due to the limited time and scope for this project, we only selected the top two drugs on the basis of their reputation FDA-approval status (

Figure 2). We chose Alvocidib, a cancer drug known to target cyclin-dependent kinases that regulate the cell cycle at high µM concentrations [

23]. Such a high concentration of Alvocidib was toxic and caused strong side effects in clinical trials. However, according to literature search results, Alvocidib instead targets a protein kinase called CILK1 (ciliogenesis associated kinase 1) at lower nM concentrations to elongate primary cilia [

15]. We also picked Alisertib, a cancer drug that targets AURKA [

24] (Aurora Kinase A) and has been shown to induce an increase in the ciliation rate.

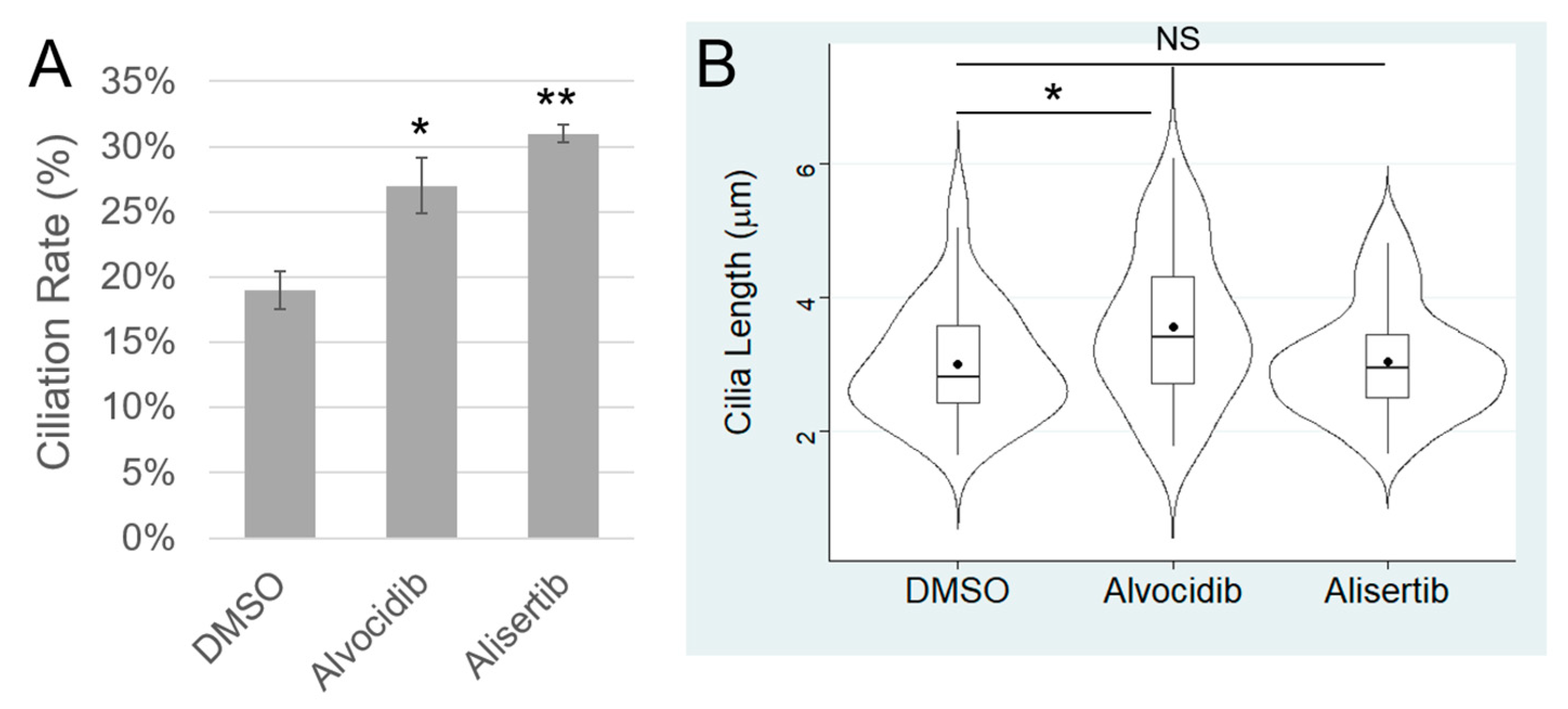

3.3. Impact of Alvocidib and Alisertib on Primary Cilia in Medulloblastoma Cells

The papers that were associated with each drug (Alvocidib and Alisertib) showed that they each statistically significantly increased ciliogenesis. However, such studies were performed on non-cancerous cells, so we needed to validate those effects on primary cilia in cancer cells. CILK1 and AURKA are both negative regulators of ciliogenesis and can be fully inhibited by Alvocidib (100 nM) and Alisertib (1 µM), respectively. We treated DAOY medulloblastoma cells with either Alvocidib, Alisertib, or DMSO (solvent control) for 16 hours and then fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained cells with the Arl13b primary cilia marker and the ϒ-tubulin basal body marker (Fig. S1). We acquired z-stack images using a confocal immunofluorescence microscope and measured cilia length and ciliation rate using ImageJ. Compared to DMSO control, Alvocidib induced a statistically significant increase in ciliation rate and cilia length, and Alisertib induced a statistically significant increase in cilia length (

Figure 3). We conclude that both Alvocidib and Alisertib can promote ciliogenesis in medulloblastoma cancer cells.

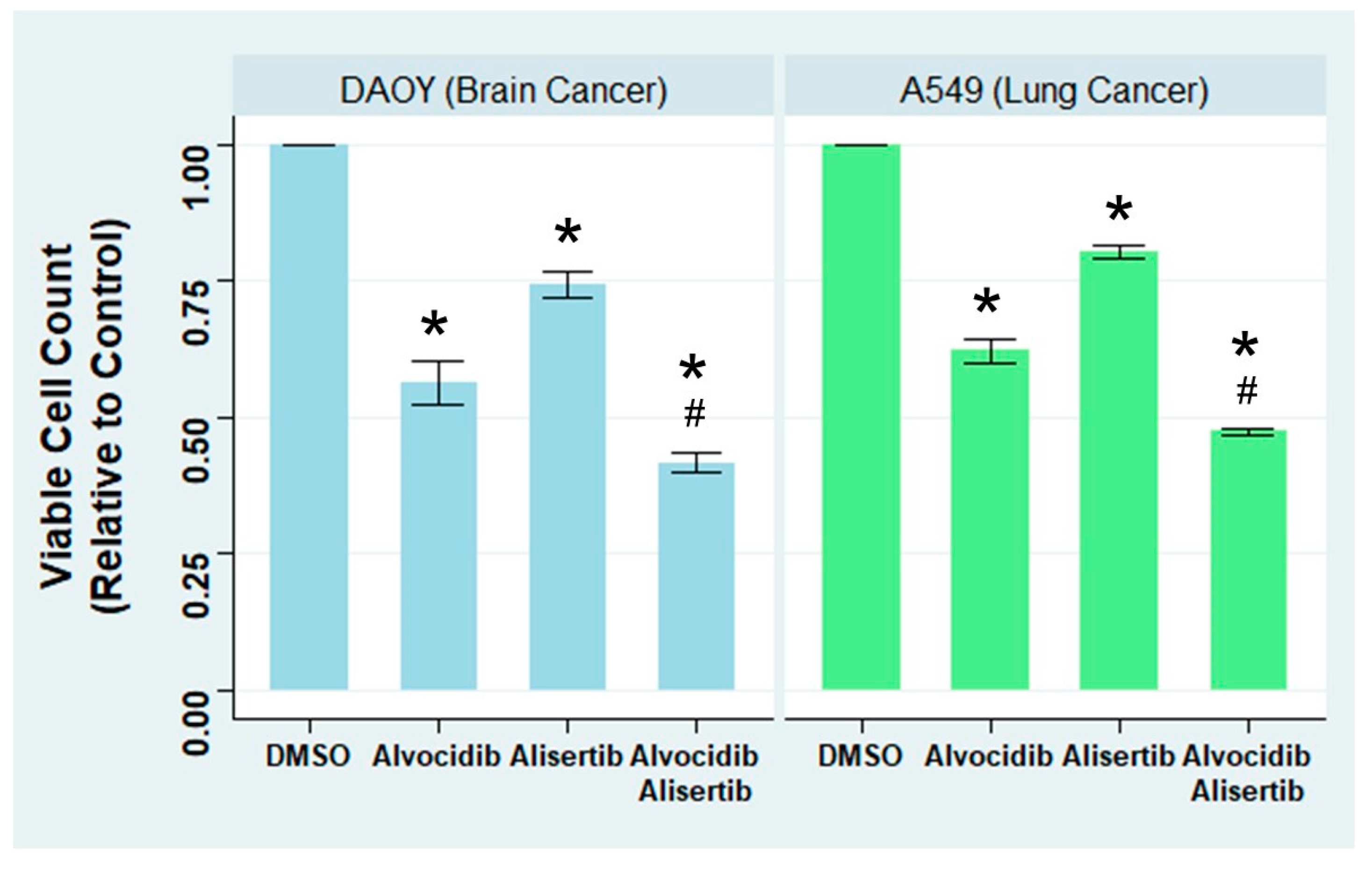

3.4. Alvocidib and Alisertib Significantly Reduce Replication of Cancer Cells

To evaluate the effect of Alvocidib and Alisertib on the number of viable cancer cells, we applied DMSO (solvent control), Alvocidib, or Alisertib to the medulloblastoma cell line DAOY. We also included an additional treatment, a combination of Alvocidib and Alisertib to test for potential additive or synergistic effects. After 3 days of treatment, we performed a crystal violet dye-based cell viability assay to determine the drug effects. Our findings indicate that relative to the DMSO control, Alvocidib induced a 40% decrease in the number of viable cancer cells, Alisertib a 20% decrease, and their combination a 60% decrease (

Figure 4, left). Similar results were replicated on the lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 (

Figure 4, right). These data indicates that Alvocidib and Alisertib can significantly decrease the number of viable cancer cells, supporting the hypothesis that cilia-promoting drugs decelerate cancer cell replication.

4. Discussion

Our study results show that the drugs discovered by this method of LLM-integrated web scraping, Alvocidib and Alisertib, can significantly promote ciliogenesis and reduce the number of viable cancer cells. Under a microscope, we observed a very small number of dead cells, indicating that these drugs served primarily to hinder the cell cycle and cell replication rather than to directly target and kill the cells. Our findings also underscore the strong potential of integrating artificial intelligence-assisted scrapers to literature review and biomedical research, though further studies must be conducted to support more widespread positive LLM performance. In addition to providing accurate answers to the questions posed by the user that enabled identification of the drugs to promote ciliogenesis, the LLM-backed scraper performed those tasks at rapid speeds. The scraper parsed through the 103 articles it located in just over 55 minutes, meaning that essentially every 30 seconds, an article was extracted of its basic information, parsed thoroughly by the LLM to locate answers to user questions, and then that answer was generated and saved to the Excel sheet. Moreover, due to the nature of those specific answers being pre-generated when we opened the Excel sheet, it only took two hours to identify those top drugs. A process that would take days or even weeks was reduced to a few hours, and the findings were equally as significant.

Despite the need for further experimentation, our approach also gives much versatility in terms of applying the method to various other areas of study. This is due to our overarching framework’s flexibility of using a keyword search-centered web scraper to select a subset of research and then ask questions to synthesize article information. Within this process, there are two major places where adjustments can be made to alter the content of the literature search. The first is the set of keywords and logic used to conduct the initial filtration of articles, determining which field the literature search is being performed in. Furthermore, there is much flexibility in this step regarding the specificity of the keywords chosen. Fewer keywords and logic will lend itself to a broader search that encompasses more articles, while more keywords with stricter logic will return fewer and more specific papers. The second place in the process is the selection of questions given to the LLM for the analysis of those keyword-selected articles. Questions can range from summarizing the paper to finding a very specific attribute of the study that the reviewer is looking for.

The scope of our study limited our wet-bench tests to two drugs and two different types of cancer cells. Although our data are promising, more research must be performed to determine the applicability of different cilia drug combinations on many other types of cancers, both in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, it would be valuable to better understand the underlying pathways and mechanisms of action of these cilia-promoting drugs, providing molecular basis to expand on their applications.

The LLM-integrated literature search aspect of our study also has certain limitations. As stated previously, the manual selection of keywords and questions dictates the results that are returned. In our study, professionals in the field validated the keywords used for the initial search and the questions that were used by the LLM for the detailed processing step. Even then, we had to perform several searches and compare the results to judge the best combination of keywords and questions. This manual trial-and-error process for the literature search means that there is no guarantee the keywords and questions are optimized. In future studies we hope to automate this segment of the process with artificial intelligence or machine learning-based solutions, giving us the maximum confidence that the results and answers produced are the best suited for that specific literature search scenario. Also, as with any current automated process, the results of the scraper and LLM are not perfect. It is nearly impossible to find exact keyword logic that can completely encompass all related articles on a massive database or ensure that no unrelated articles are returned. Similarly, minor summarization errors of the LLM were uncovered during the manual check. Thus, a human professional is still crucial to ensuring the validity of the article, and even more so when discussing biomedical sciences. It would also be interesting to see if better results could be produced by other popular large language models.

Despite these areas for further improvement, this method of LLM-integrated literature scrapers presents significant potential for use as an assistive tool for biomedical research. Its speed and accuracy in parsing through comprehensive databases that are only expanding are unmatched and hard to overlook.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Immunofluorescence of primary cilia in DAOY medulloblastoma cells. The scraper code with LLM is available at

https://github.com/uvapharm/cilia_scraper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.F., Y.Z., R.A. and Z.F.; methodology, S.H.F., A.L.; software, S.H.F.; validation, S.H.F., A.L. and C.P.; formal analysis, S.H.F., A.L., C.P., N.S., Y.Z. and Z.F.; investigation, S.H.F., A.L., C.P. and N.S.; resources, R.A. and Z.F.; data curation, S.H.F. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.F.; writing—review and editing, A.L., Y.Z., R.A. and Z.F.; visualization, A.L.; supervision, Y.Z. and Z.F.; project administration, R.A. and Z.F.; funding acquisition, R.A. and Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Neuro-Translational Pilot Grant from University of Virginia Cancer Center to R.A. and Z.F.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Michael Broad at the Focused Ultrasound Foundation, Charlottesville, Virginia, for advice and guidance on coding scraper. We thank the technical support from the Advanced Microscopy Facility at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, which is supported through the University of Virginia Cancer Center National Cancer Institute P30 Center Grant P30CA044579.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. Fry, M. J. Leaper, and R. Bayliss, “The primary cilium,” Organogenesis, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 62–68, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Singla and J. F. Reiter, “The primary cilium as the cell’s antenna: signaling at a sensory organelle,” Science, vol. 313, no. 5787, pp. 629–633, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Malicki and C. A. Johnson, “The Cilium: Cellular Antenna and Central Processing Unit,” Trends Cell Biol, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 126–140, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Reiter and M. R. Leroux, “Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies,” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, vol. 18, no. 9, pp. 533–547, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Badano, N. Mitsuma, P. L. Beales, and N. Katsanis, “The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders,” Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, vol. 7, pp. 125–148, 2006. [CrossRef]

- V. Plotnikova, E. N. Pugacheva, and E. A. Golemis, “Primary Cilia and the Cell Cycle,” Methods Cell Biol, vol. 94, pp. 137–160, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Goto, A. Inoko, and M. Inagaki, “Cell cycle progression by the repression of primary cilia formation in proliferating cells,” Cell Mol Life Sci, vol. 70, no. 20, pp. 3893–3905, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Paré and S. Kitsiou, “Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews,” in Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet], University of Victoria, 2017. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481583/.

- Lotfi, S. Srinivasan, M. Ertz, and I. Latrous, “Web Scraping Techniques and Applications: A Literature Review,” 2021, pp. 381–394. [CrossRef]

- S. Kublik and S. Saboo, GPT-3: The Ultimate Guide To Building NLP Products With OpenAI API. Packt Publishing Ltd., 2023.

- C.-Y. Lu and I. Chen, “Leveraging OpenAI API for Developing a Monopoly Game-Inspired Educational Tool Fostering Collaborative Learning and Self-efficacy,” in Innovative Technologies and Learning, Y.-P. Cheng, M. Pedaste, E. Bardone, and Y.-M. Huang, Eds., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 247–255. [CrossRef]

- J. Finnie-Ansley, P. Denny, B. A. Becker, A. Luxton-Reilly, and J. Prather, “The Robots Are Coming: Exploring the Implications of OpenAI Codex on Introductory Programming,” in Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Computing Education Conference, in ACE ’22. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Feb. 2022, pp. 10–19. [CrossRef]

- B. Schroeder, E. T. A. Dobson, C. T. Rueden, P. Tomancak, F. Jug, and K. W. Eliceiri, “The ImageJ ecosystem: Open-source software for image visualization, processing, and analysis,” Protein Sci, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 234–249, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Feoktistova, P. Geserick, and M. Leverkus, “Crystal Violet Assay for Determining Viability of Cultured Cells,” Cold Spring Harb Protoc, vol. 2016, no. 4, p. pdb.prot087379, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. X. Wang, J. S. Turner, D. L. Brautigan, and Z. Fu, “Modulation of Primary Cilia by Alvocidib Inhibition of CILK1,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 15, Art. no. 15, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Jeffries, M. Di Filippo, and F. Galbiati, “Failure to reabsorb the primary cilium induces cellular senescence,” The FASEB Journal, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 4866–4882, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Cloonan, H. C. Lam, S. W. Ryter, and A. M. Choi, “‘Ciliophagy’: The consumption of cilia components by autophagy,” Autophagy, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 532–534, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- W. Alhassen et al., “Regulation of Brain Primary Cilia Length by MCH Signaling: Evidence from Pharmacological, Genetic, Optogenetic, and Chemogenic Manipulations,” Mol Neurobiol, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 245–265, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Zahid, T. N. Feinstein, A. Oro, M. Schwartz, A. D. Lee, and C. W. Lo, “Rapid Ex-Vivo Ciliogenesis and Dose-Dependent Effect of Notch Inhibition on Ciliogenesis of Respiratory Epithelia,” Biomolecules, vol. 10, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kakiuchi et al., “Rho-kinase and PKCα Inhibition Induces Primary Cilia Elongation and Alters the Behavior of Undifferentiated and Differentiated Temperature-sensitive Mouse Cochlear Cells,” J Histochem Cytochem., vol. 67, no. 7, pp. 523–535, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Takahashi, T. Nagai, S. Chiba, K. Nakayama, and K. Mizuno, “Glucose deprivation induces primary cilium formation through mTORC1 inactivation,” J Cell Sci, vol. 131, no. 1, p. jcs208769, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Guo et al., “[Piezo1 Mediates the Regulation of Substrate Stiffness on Primary Cilia in Chondrocytes],” Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 67–73, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Am, “Flavopiridol: the first cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in human clinical trials,” Investigational new drugs, vol. 17, no. 3, 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. Malumbres and I. Pérez de Castro, “Aurora kinase A inhibitors: promising agents in antitumoral therapy,” Expert Opin Ther Targets, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1377–1393, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).