1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is considered a significant global health threat due to the increasing resistance to multiple antibiotics. Commonly colonizing human skin and nasal passages,

S. aureus strains have developed resistance to methicillin, rendering traditional antibiotic treatments less effective [

1]. MRSA, alongside other antibiotic-resistant pathogens including

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Enterococcus faecium, has contributed to increased morbidity and mortality rates, as well as escalating healthcare costs [

2]. Popovich et al. (2023) reported the prevalence of MRSA as a leading cause of nosocomial infections worldwide, underscoring the critical need for effective infection control measures. Moreover, infections are frequently associated with severe complications, including necrotizing pneumonia, and endocarditis that can lead to sepsis. The limited therapeutic options for MRSA infections have led to prolonged hospitalization and increased mortality rates [

4].

In response to the increasing threat, natural products have been proposed as promising sources of novel anti-MRSA compounds. Species of the

Piper genus, such as

Piper betle and

Piper nigrum, have garnered significant study interest due to the diverse phytochemical constituents and anti-MRSA activity [

5]. Both bacteria are used traditionally in medicinal systems to treat various diseases. The rich phytochemical profile, which includes alkaloids, flavonoids, and terpenoids, contributes to the antimicrobial potential. Key bioactive compounds identified in the

P. betle include eugenol, chavicol, and chavibetol. Eugenol, for instance, is renowned for the potent antiseptic properties and has been extensively studied for antimicrobial activity [

6].

P.

nigrum contains piperine, which imparts the characteristic pungent flavor of black pepper. Piperine has broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria such as

S. aureus [

7].

P. betle and

P. nigrum have significant potential as natural sources for the development of novel antimicrobial agents, particularly against antibiotic resistance. To maximize the anti-MRSA activity of these plants, optimizing the extraction methodologies is crucial for achieving high yields of bioactive compounds [

8]. Factors such as solvent type, solid-to-solvent ratio, extraction time, and temperature can significantly influence the efficiency of extracting target compounds. Previous studies have demonstrated that an appropriate extraction method can substantially enhance the bioactive content of plant extracts [

9]. For instance, polar solvents including methanol or ethanol are often effective for extracting phenolic compounds such as eugenol and flavonoids from

the P. betle and

P. nigrum [

10]. Furthermore, advanced extraction methods, including ultrasound-assisted and microwave-assisted extraction, can improve efficiency and reduce processing time [

11]. This implies that optimization of extraction procedures is a crucial initial step in developing natural products using

P. betle and

P. nigrum as anti-MRSA agents.

Following the acquisition of plant extracts using optimized extraction methods, metabolomic profiling was performed to identify the bioactive compounds responsible for anti-MRSA activity. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy can be used to obtain the chemical profiles of the extracts and provide preliminary information about the major functional groups present [

12]. Cluster analysis (CA) was applied to group samples based on FTIR spectral similarity, facilitating the identification of samples with high potential anti-MRSA activity. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is a powerful method for the identification and quantification of volatile and semivolatile compounds in plant extracts [

13].

Integrating FTIR, CA, and GC-MS is crucial to obtain a comprehensive metabolomic profile of plant extracts and identify key bioactive compounds contributing to anti-MRSA activity. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this multi-technique approach for characterizing plant metabolites and discovering novel bioactive compounds [

14]. FTIR spectroscopy is considered a valuable tool for qualitative and quantitative analysis of major components in plant extracts, while GC-MS is the gold standard for the identification and quantification of volatile compounds. Integrating metabolomic data from

in silico and

in vitro studies is a crucial synergistic method for drug discovery [

15].

Following the identification of potential bioactive compounds from

the P. betle and

P. nigrum through GC-MS,

in silico studies, such as molecular docking, can be used to predict the molecular interactions of compounds with MRSA bacteria protein targets. This

in silico information is crucial to filter candidate compounds validated through

in vitro antibacterial assays using MRSA clinical isolates [

16]. By integrating CA of extract variability profiles,

in silico metabolomics, and

in vitro experimental validation, this study presents an innovative approach for identifying novel bioactive compounds in

the P. betle and

P. nigrum. The multi-disciplinary approach not only enables accurate identification of potential anti-MRSA agents but also provides insights into the chemical diversity within plant extracts and correlation with biological activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Fresh samples of

P. betle (green betel) and

P. nigrum (black pepper) stems, fruits, and leaves were procured from Puty Village, Bua District, Luwu Regency, and South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Botanical authentication of the collected plant materials was rigorously conducted at the Botanical Laboratory, Department of Biology, Mathematics, and Natural Sciences, Universitas Negeri Makassar, Indonesia. This process ensured the accurate identification and verification of plant species used in the study. Following authentication, the plant materials were dried in an oven maintained at a temperature of 40-50 °C for three days [

17]. The dried plant matter was pulverized using a blender and sieved through a 40/60 mesh sieve to obtain fine powder. The powdered material obtained was then securely stored in airtight containers for further analysis.

2.2. Extraction Methods

Ultrasonic-assisted extraction was used to extract bioactive compounds from the plant materials. For each sample, 20 g was extracted using 200 mL of aquadest, methanol, or hexane in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min, maintaining a solvent-to-solid ratio of 1:10 throughout the process. Following extraction, the mixtures were filtered, and the solvents were evaporated using either a rotary evaporator or a freeze-dryer to obtain concentrated or dry extracts, respectively. The extraction yield was determined using a specific formula [

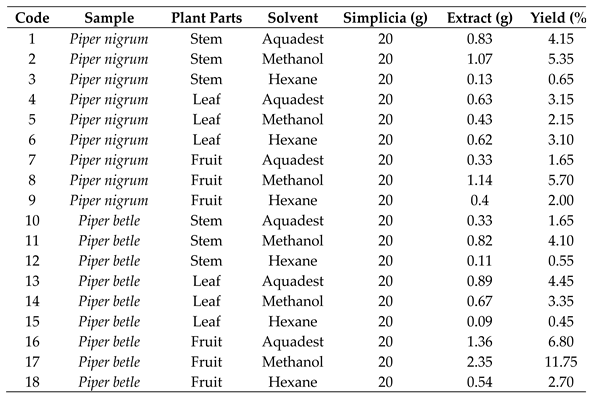

17]. A total of 18 extracts were obtained for subsequent analysis, as listed in

Table 1. These include aquadest (1), methanol (2), and hexane extract of

P. nigrum stem (3), aquadest (4), methanol (5), and hexane extract of

P. nigrum leaves (6), aquadest (7), hexane (8), and methanol extract of

P. nigrum fruits (9), as well as aquadest (10), methanol (11), and hexane extract of

P. betle stem (12), aquadest (13), methanol (14), and hexane extract of

P. betle leaves (15), aquadest (16), methanol (17), and hexane extract of

P. betle fruits (18).

2.3. FTIR Analysis

FTIR Spectroscopyanalysis was conducted on 18 Piper extract varieties. To prepare the samples, 5 mg of each extract was mixed with 0.5 mg of potassium bromide (KBr) and 5 mL of analytical-grade methanol. The mixture was homogenized and dried to form a pellet which was then analyzed using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum GX FTIR spectrometer. Spectra were collected over a wavelength range of 400-4000 cm⁻¹ with 16 scans per sample.

To identify similarities and differences between the extracts, a chemometric analysis using CA was performed with Minitab 18 software. CA was applied to group the 18 extracts based on spectral profiles. Extracts with a similarity above 80% were considered to have similar chemical characteristics [

18]. Based on the CA results, six clusters were identified, cluster 1 consisted of extract (1), cluster 2 included extracts (2, 4, 10, and 13), and cluster 3 contained extracts (7 and 12). Furthermore, cluster 4 comprised extracts (5, 11, and 18), cluster 5 included extracts (3, 6, 9, 14, 15, 16, and 17), and cluster 6 consisted of extract (8). Representatives from each cluster were selected for anti-MRSA activity testing, including extract (1) from cluster 1, extract (4) from cluster 2, extract (7) from cluster 3, extract (11) from cluster 4, extract (16) from cluster 5, and extract (8) from cluster 6.

2.4. Anti-MRSA Activity

The MRSA bacteria used in this study were patient isolates from Hasanuddin University Teaching Hospital with a pronumber code (050402003763271). These isolates have shown significant resistance (p>0.05) against various antimicrobials, including Flomoxef, Latamoxef, Benzylpenicillin, Nafcillin, Amoxicillin, Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid, Ampicillin/Sulbactam, Carbenicillin, Ticarcillin, Ticarcillin/Clavulanic Acid, Azlocillin, Piperacillin, Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Cloxacillin, Dicloxacillin, Flucloxacillin, and Methicillin. Others include Oxacillin MIC, Oxacillin, Cefaclor, Cefadroxil, Cefixime, Cefpodoxime, Ceftibuten, Cefmenoxime, Cefoperazone, Cefotaxime, Cefoxitin, Ceftazidime, Ceftizoxime, Ceftriaxone, Cefepime, Cefpirome, Doripenem, Ertapenem, Faropenem, Imipenem, and Meropenem. Based on the antimicrobial testing conducted on September 27, 2023, the isolates showed sensitivity (p<0.05) to gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and Ofloxacin, with Card number (AST-GP67) and lot number (1322462503).

For antimicrobial activity testing, Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) was added to Petri dishes. A 0.5 mL suspension of MRSA bacteria, prepared to match the McFarland standard of 0.5, was evenly spread across the surface of the MHA using a sterile swab [

19]. The Petri dishes were then divided into three sections, one each for negative control, positive control, and test samples. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) at 0.05 mL) was used as the negative control, while ciprofloxacin (15 μ g/disk) represented the positive control. The test samples included the following extracts, aquadest extract of

P. nigrum stem (1) leaves (4), and fruits (7), as well as hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits (8), methanol extract of

P. betle stem (11) and aquadest extract of

P. betle fruits (16). All samples were tested at a concentration of 200 mg/mL using the paper disk method, in which paper disks were soaked in the samples for 5 min before being placed on the surface of MHA inoculated with MRSA. The Petri dishes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the inhibition zones (clear zones) around the paper disks were observed and measured using a caliper in millimeters (mm) [

20]. The samples with the highest antimicrobial activity were further analyzed by GC-MS for the characterization of active metabolites with anti-MRSA activity.

2.5. GC-MS Analysis

GC-MS analysis was conducted at the Chemical Engineering Laboratory, Politeknik Negeri Ujung Pandang (PNUP), Makassar City, Indonesia. The test samples showing the highest anti-MRSA activity, namely the hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits (8) and the aquadest extract of

P. betle fruits (16) (1 g), were dissolved in 5 mL of 96% ethanol (p.a). The homogenization process was carried out in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min at 55 °C. Subsequently, the mixture was filtered using Whatman filter paper (No. 42), and the obtained filtrate was injected into a GC-MS Ultra QP 2010 (Shimadzu) instrument [

21].

The chromatographic conditions include injector temperature of 250 °C with a splitless mode, pressure of 76.9 kPa, carrier gas flow rate of 14 mL/min, and split ratio of 1:10. The ion source and interface temperatures were set to 200 °C and 280 °C, respectively, with a solvent cut-off time of 3 min and mass ranges of 400–700 m/z. Moreover, the column was an SH-Rxi-5Sil MS with a length of 30 m and an inner diameter of 0.25 mm. The initial column temperature was set at 70 °C with a hold time of 2 min and then increased at a rate of 10 °C/min until 200°C was reached. Finally, the temperature was increased further to 280 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min with a hold time of 9 min, resulting in a total analysis time of 36 min. The obtained chromatogram data were analyzed using the NIST 17 and Wiley 9 libraries to identify major compounds in the plant extracts with an area percentage of >1% [

22]. The identified major compounds were then further analyzed using

in silico methods to understand the mechanism of action and interaction of the compounds with MRSA target proteins.

2.6. Molecular Docking Studies

2.6.1. Sample Preparation (Virtual Screening)

The compounds identified through GC-MS analysis of extracts (8) and (16) were subjected to molecular docking. Initially, the structures of these compounds were searched and downloaded from PubChem (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The platform provides detailed information on the compound structures, including SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) data, which can be used to download the 3D structure in PDF format for docking purposes. The target proteins for molecular docking were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (

https://www.rcsb.org) in PDF [

23]. In this study, the MRSA target proteins 4DKI, 6H5O, and 4CJN were prepared for docking.

2.6.2. Molecular Docking

Ligand optimization was performed using Chimera 1.17.3 (UCSF Chimera;

https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/). PyMOL version 2.5 (

https://pymol.org/2) was used to correct protein structures, remove ligands, and eliminate water molecules. The docking process was conducted using PyRx AutoDock Vina (

https://pyrx.sourceforge.io/), which was used to calculate binding affinity, RMSD, amino acid residues, and bond types between the optimized ligands and receptors. Furthermore, the interaction results between the ligand and receptor were visualized using the Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer (

https://www.3dsbiovia.com). The ligand with the lowest binding energy or docking score, along with hydrogen-bonding interactions, was selected as the best candidate [

24].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction Optimization

Table 1 shows the extraction yields of various extracts from different parts of

P. nigrum and

P. betle using different solvents.

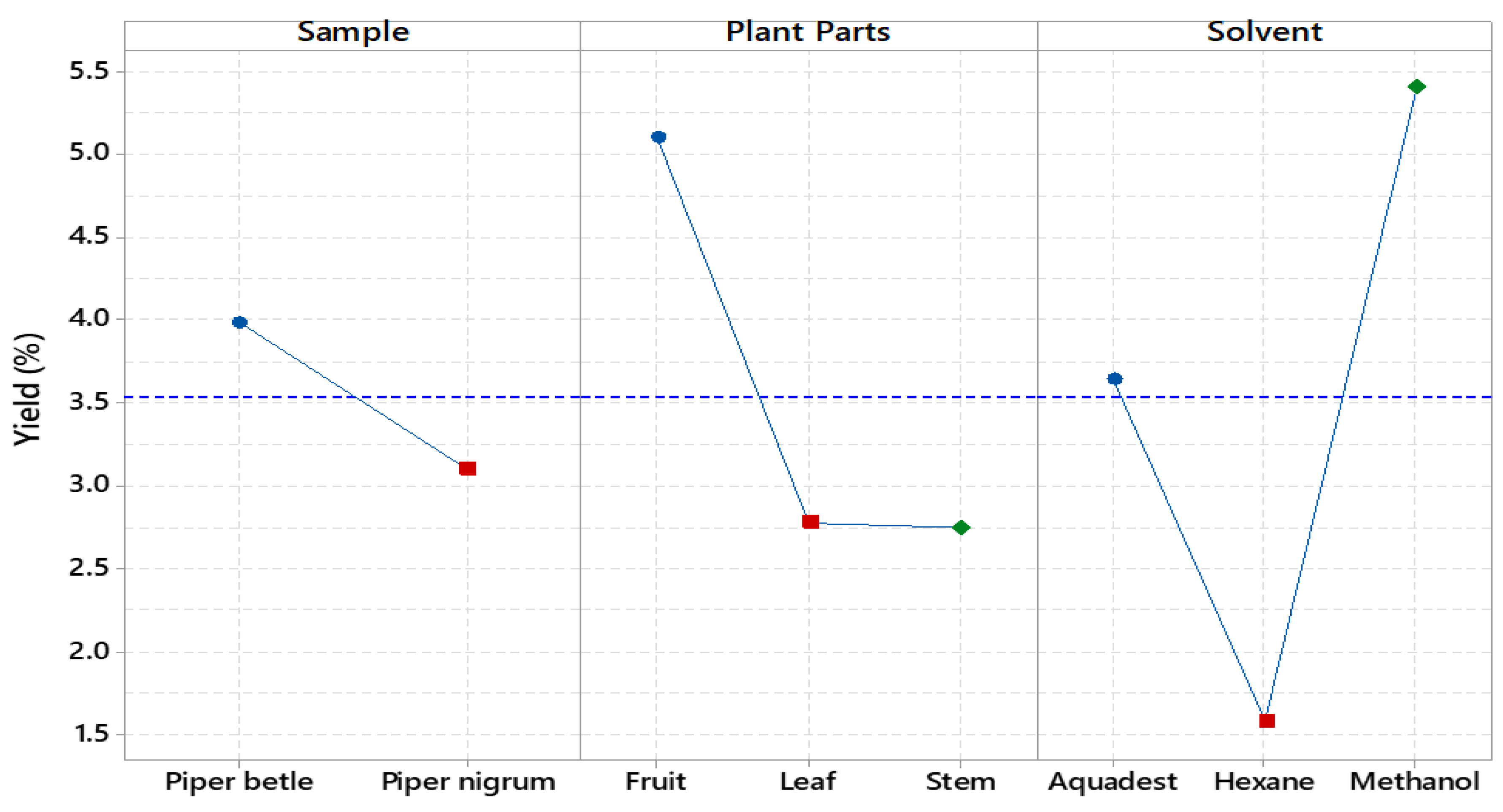

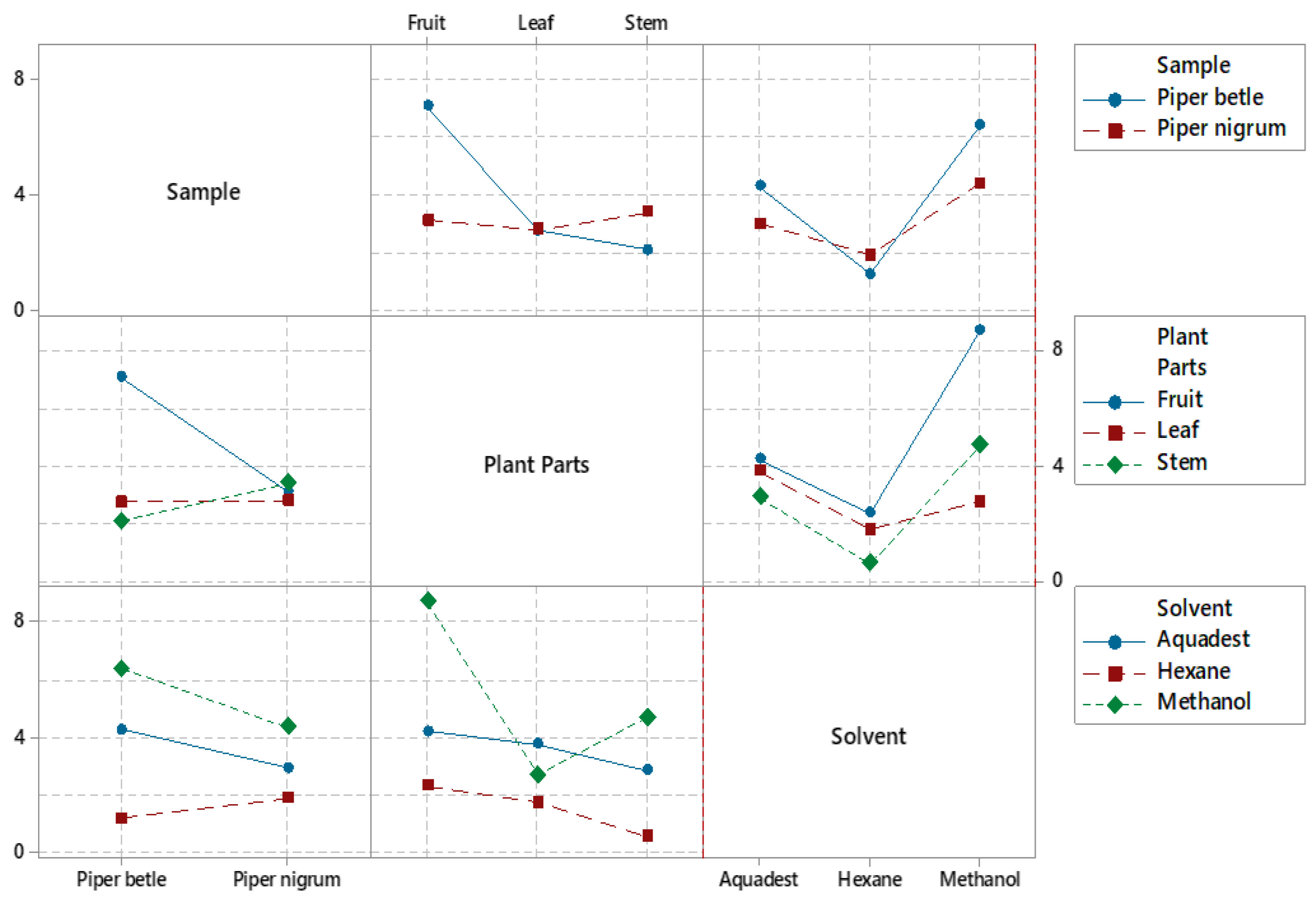

Based on the results, the influence of the solvent on the extraction yield followed the order methanol > aquadest > hexane, with the plant parts yielding in the order fruit > leaves > stems (

Figure 1). For

P. nigrum stem, methanol produced the highest yield of 5.35%, while hexane produced the lowest at 0.65%. For the leaves, methanol and hexane yields were 2.15% and 3.10%, respectively, with aquadest having a slightly higher yield at 3.15%. In terms of fruit, methanol provided the highest yield at 5.70%, and aquadest produced the lowest at 1.65%. For

P. betle, methanol had the highest stem yield of 4.10%, with hexane producing the lowest at 0.55% (

Figure 2). The methanol extract was found to contain the highest amounts of hydroxychavicol, eugenol, and gallic acid. All three compounds were present at low levels in the

P. betle leaf hexane extract [

25].

The aquadest extract had the highest yield of 4.45%, while hexane had the lowest at 0.45%. Regarding fruit, methanol achieved the highest yield at 11.75%, followed by aquadest at 6.80%, while hexane provided the lowest at 2.70%. In general, methanol generally resulted in higher extraction yields across different plant parts for both species, especially for fruits. In a study by Rajopadhye et al. (2012), black pepper roots were used for Soxhlet extraction with methanol producing a Peperine concentration of 9.56 ± 0.83 mg/g [

26]. Hexane generally produced lower yields, while aquadest treatment was moderately effective, particularly for leaves and fruits. This information is crucial for selecting the most efficient solvent based on the desired yield and plant characteristics.

3.2. FTIR Profiling Analysis

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectral profiles of various active compounds isolated from

Piper spp., including

P. nigrum and

P. betle.

The peaks at 3383.14 cm⁻¹ and 3404 cm⁻¹ represent OH stretching bonds, commonly associated with compounds such as Piperanine from

Piper retrofractum [

27]

. Furthermore, the peak at 3291.31 cm⁻¹ corresponded to phenolic O–H stretching in hydroxychavicol from

P. betle [

28]

. The peak at 3469 cm⁻¹ was related to the stretching bonds of OH groups in piperine from

P. nigrum [

29]. The range of 2927.94 cm⁻¹ to 2936 cm⁻¹ suggested aliphatic C–H stretching bands associated with compounds such as Hydroxychavicol [

28] and β-caryophyllene oxide [

30]. Moreover, the peak at 2856.58 cm⁻¹ signified aliphatic C–H stretching in Piperine and Pellitorine [

31]. Peaks at 1637.56 cm⁻¹ and 1647.45 cm⁻¹ indicated C=C symmetric aromatic stretching in Hydroxychavicol [

28] and Piperanine [

31], while peaks at 1658 cm⁻¹ and 1636 cm⁻¹ represent conjugated diene symmetric stretching in Piperanine [

27] and Piperine [

29]. Furthermore, peaks at 1600.92 cm⁻¹ and 1613 cm⁻¹ imply conjugated asymmetric diene stretching associated with Piperine [

32] and Chavibetol [

33,

34]. The profile also included aromatic C=C stretching at 1582 cm⁻¹ and 1598 cm⁻¹, CH

2 bending at 1446.61 cm⁻¹, and C–O stretching at 1197.79 cm⁻¹, representing various active compounds such as Chavibetol [

33,

34], Piperine [

29], β-caryophyllene oxide [

30], and Hydroxychavicol [

28].

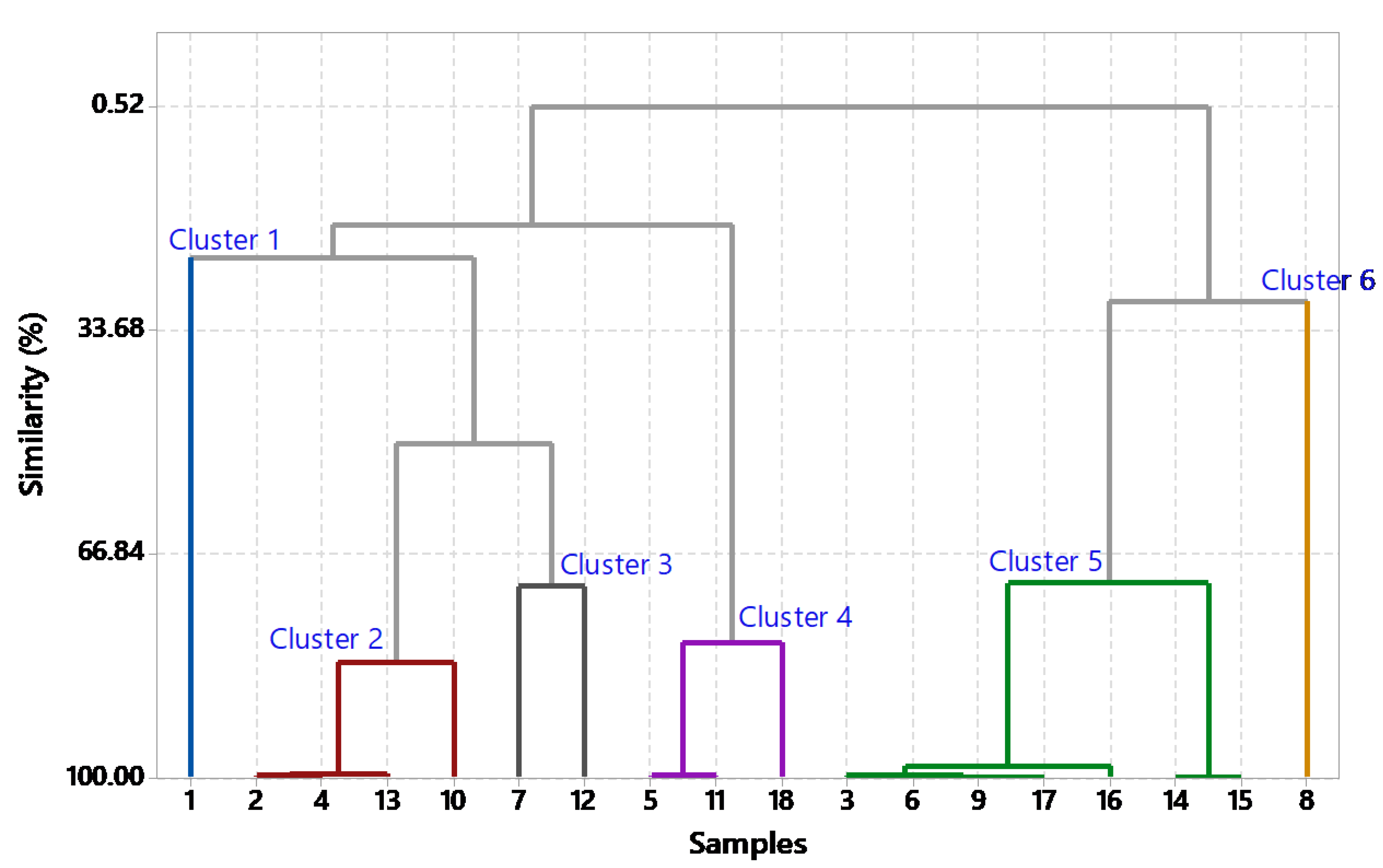

This FTIR profile provides valuable insights into the functional groups and main components in

Piper extracts, which are crucial for chemical characterization and phytochemical studies. CA based on functional groups detailed the hierarchical clustering process, in which observations were sequentially merged into larger clusters according to similarity and distance levels [

18]. The analysis initially started with 18 distinct clusters, each representing individual observations or small groups. In the initial step, clusters 9 and 17 merged to form a new cluster (cluster 9) containing two observations, at a high similarity level of 99.8523%. This merging process continued, with clusters 14 and 15 combining into cluster 14 in subsequent steps, progressively reducing the total number of clusters. By the fifth step, clusters 3 and 6 merged into a larger cluster (cluster 3), now comprising four observations. This pattern further led to the aggregation of more clusters into increasingly larger groups, and each step reduced the number. For example, clusters 2 and 7 combined in the 14th step to form cluster 2, which included six observation groups.

In the final partition of the CA in

Figure 4, six distinct clusters formed with high similarity levels >80%. Cluster 1 includes observations from the initial analysis step. Cluster 2 combines observations from 2, 4, 10, and 13. Cluster 3 aggregates observations from 3, 6, 9, 14, 15, 16, and 17, with Piperine as a significant component, and cluster 4 merged observations from 5, 11, and 18. Cluster 5 consolidates observations from clusters 7 and 12, while cluster 6 represents observations from cluster 8. The final grouping reflects the hierarchical relationships among observations, capturing similarities and distances throughout the clustering process [

35]. Since clusters with similar functional groups based on FTIR data are likely to have the same pharmacological effects [

36], representatives from each cluster were selected for further anti-MRSA activity testing. This novel approach in natural product study simplifies the screening process by focusing on extracts with similar functional group compounds, thereby facilitating the identification of potential candidates without the need to test each extract individually. The extracts selected for anti-MRSA testing included (1) from cluster 1, (4) from cluster 2, (7) from cluster 3, (11) from cluster 4, (16) from cluster 5, and (8) from cluster 6.

3.3. Anti-MRSA Activity

Based on

Table 2, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted to assess the anti-MRSA activity of seven different samples showed significant differences in effectiveness.

The analysis tested the null hypothesis stating that all sample means are equal and the alternative hypothesis stating that at least some sample means differ. With a significance level of 0.05 and assuming equal variances, the ANOVA results showed a highly significant F-value of 122.76 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating that not all samples had the same anti-MRSA activity. The factors in question included six different extracts, namely aquadest extract of

P. betle fruits (16),

P.

nigrum fruits (7), aquadest extract of

P. nigrum leaves (4), aquadest extract of

P. nigrum stem (1), Ciprofloxacin (a standard antibiotic control), hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits (8), and methanol extract of

P. betle stem (11). The ANOVA showed an adjusted squares sum of 736.57 and an adjusted mean square of 122.762. The model summary indicates a high R

2 value of 98.13%, reflecting that differences in anti-MRSA activity among samples account for nearly all variability in the data. The antimicrobial activity of

P. betle against 20 clinical isolates of S.

pseudintermedius (10 MSSP and 10 MRSP) was tested using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method with P.

betle extract disks (250, 2500, and 5000 µg). The MIC against all isolates was 250 µg/mL [

37].

Tukey’s pairwise comparisons further clarified the differences observed. As shown in

Table 2, Ciprofloxacin had the highest mean anti-MRSA activity (26 mm), which was significantly different from all other extracts, with a confidence level of 99.58%. The aquadest extract of

P. betle fruits had mean anti-MRSA activity of 19 mm, which significantly outperformed the hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits (mean = 15 mm) and the aquadest extract of

P. nigrum leaves (mean = 6 mm). The methanol extract of

the P. betle stem, with a mean of 15 mm, differed significantly compared to the lower-performing extracts but not from all other samples. The aquadest extract of

P. nigrum stem (mean = 9 mm) also had significant differences from the lowest-performing extracts. This study accumulatively reports the novel potential utility of the

Curcuma longa L. and

Piper nigrum L. extracts synergistically against MRSA infection by interfering with the mechanism of infectious angiogenesis and bactericidal action [

38].

In summary, the statistical analysis shows the superior anti-MRSA activity of ciprofloxacin compared to plant extracts. Based on the results, the aquadest extract from P. betle fruits (16), hexane extract from P. nigrum fruit (8), and methanol extract from P. betle stem were the most effective, while the aquadest extract from P. nigrum leaves had the least activity. This comprehensive evaluation helps identify promising candidates for further study and therapeutic applications.

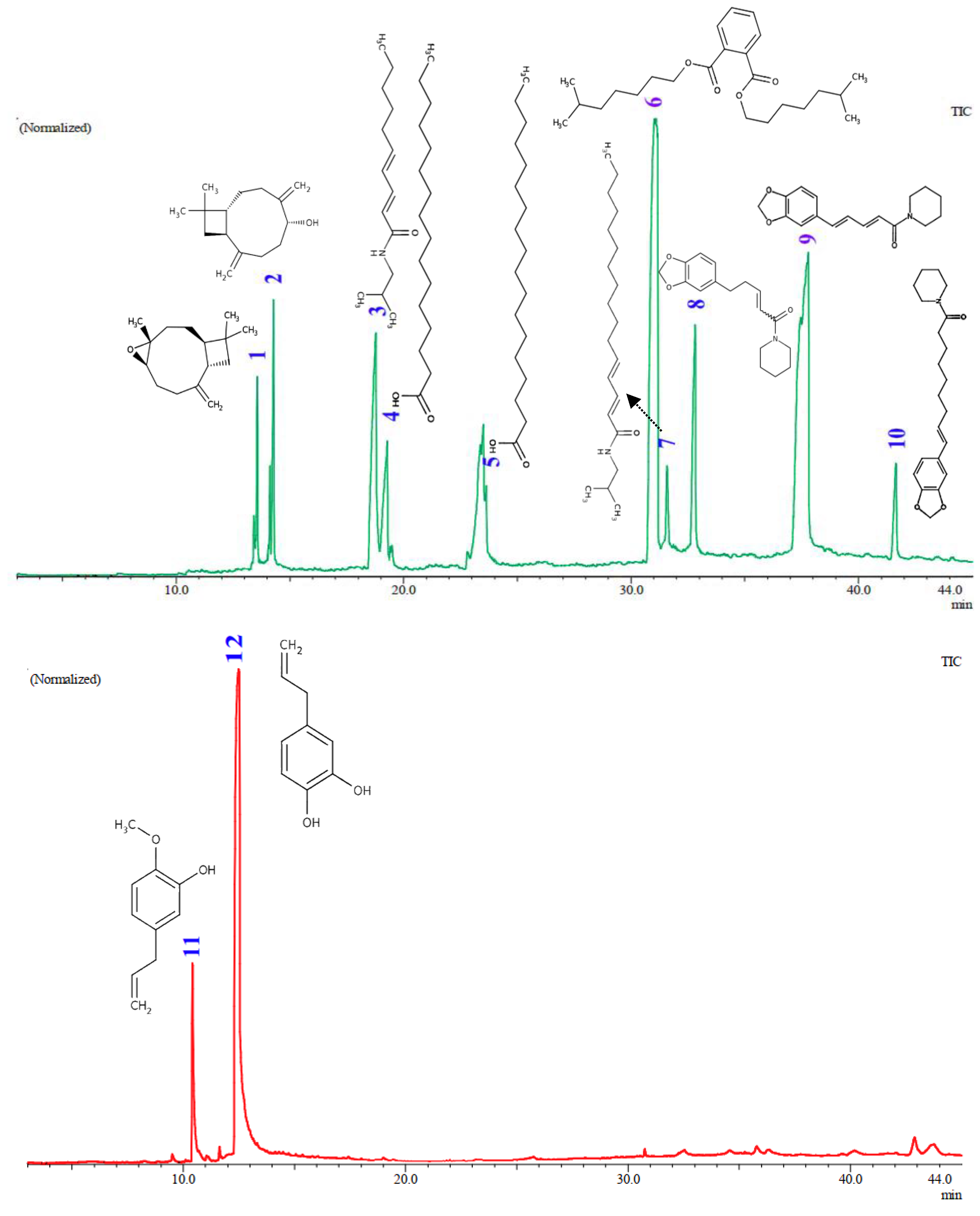

3.4. GC-MS Metabolite Characterization

The GC-MS analysis (

Figure 5 and

Table 3) of

the Piper plant extracts showed important connections between the identified chemical components and anti-MRSA activity. The aquadest extract of

P. betle fruits (16) and the hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruit (8) were subjected to GC profiling to identify the major compounds responsible for anti-MRSA activity. The hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits was found to contain piperine, a major component [

39] with an area of 14.22% and a similarity index (SI) of 93%. This compound has strong antimicrobial properties and is

capable of reducing the secretion of diverse virulence factors

from MRSA. Therefore, piperine could be a potential antibiofilm molecule against MRSA-associated biofilm infections [

40]

. This correlates with the anti-MRSA testing results, where extracts containing piperine showed significant activity against MRSA. Pellitorine, also present in the extract with an area of 5.08% and an SI of 93%, may be able to inhibit bacteria efflux pumps. At 16 µg/mL, pellitorine increased the sensitivity of

S. aureus (RN4220) to erythromycin through inhibition of the efflux pumps [

41], thereby contributing to antimicrobial activity. Other components such as Diisooctyl Phthalate and Piperazine, though present in significant amounts of 14.67% and 4.03%, respectively, require further investigation to understand specific roles in anti-MRSA activity [

42]. For the aquadest extract of

P.

betle fruits (16), Hydroxychavicol was identified as the primary compound, making up 81.89% of the extract with an SI of 93%. This suggests that the suggesting that the compound plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of the extract against MRSA.

The extract leaves of

P.

betle produced the highest percentage of hydroxychavicol content. Almost up to 90% of the final extract was found to contain hydroxychavicol based on HPLC analysis [

43]. This supported the result that extracts from cluster 5, including hydroxychavicol, showed significant anti-MRSA activity.

P. betle hydroxychavicol

(36.02%) was the major constituent that inhibited the growth and biofilm formation of S. pseudointermedius and MRSP isolated from canine pyoderma in a concentration-dependent manner. Therefore,

P. betle is a potential candidate for the treatment of MRSP infection and biofilm formation in veterinary medicine [

44]

. Chavibetol, with an area of 12.01% and SI of 97%, also contributed to the anti-MRSA activity but was less dominant than hydroxychavicol. The leaf extract of

P.

betle (200 g) sliced into small pieces and subjected to hydro-distillation for 270 min was found to contain Chavibetol (63.78 %) [

43]

. The chemical composition of the ethanolic extract also contained chavibetol (12.03 %) [

44]. The anti-MRSA activity was correlated with the GC-MS results, demonstrating that extracts containing high concentrations of Piperine and Hydroxychavicol had stronger antimicrobial effects. This relationship underscores the significance of both compounds in anti-MRSA activity and the potential use in developing effective antimicrobial treatments.

3.5. Molecular Docking Analysis

Table 4 shows the binding free energy values and amino acid residues interacting with the MRSA target proteins 4CJN, 4DKI, and 6H5O [

45] for the various tested compounds. These data provide insights into the molecular interactions between these compounds and MRSA target proteins, as well as how the results correlate with anti-MRSA activity assays and chemical profiles of Piper extracts identified through GC-MS.

The native ligand for the 4DKI target protein (

Figure 6) has a binding free energy of -9.8 kcal/mol and interacts with the amino acid residues LYS 406, SER 462, ASN 464, GLN 521, and THR 600 through hydrogen bonds [

46]. Ciprofloxacin, the positive control, has a binding free energy of -8.3 kcal/mol and interacts with the residues LYS 406, SER 462, and SER 643. The hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruit (8), which contains piperine, has a binding free energy of -7.7 kcal/mol and interacts with the residues GLN 521, THR 444, GLY 402, and SER 400, indicating significant potential anti-MRSA activity. Piperine, as the major component with an area of 14.22% in this extract, significantly contributes to the antimicrobial activity. Additionally, Piperolein B (1.5%) showed a binding free energy of -8.3 kcal/mol, equivalent to that of ciprofloxacin, with interactions at residues LYS 406, SER 462, and ASN 464, further enhancing the potential anti-MRSA activity. Piperanine (4.03%) and Diisooctyl phthalate (14.67%) also demonstrated significant binding free energies of 7.6 and 7.1 kcal/mol, respectively, with interactions at residues LYS406 and SER462. However, β-caryophyllene oxide and Alpha-caryophylladienol did not show any H-bond interactions with this target protein, suggesting limited anti-MRSA activity.

For the 6H5O target protein (

Figure 7), the native ligand has a binding free energy of -9.0 kcal/mol and interacts with the amino acid residues THR 444, SER 598, SER 461, SER 403, LYS 406, and ASN 464 [

47]. Ciprofloxacin, as the positive control, has a binding free energy of -8.1 kcal/mol and interacts with LYS 406, SER 403, SER 462, and SER 643. Furthermore, Piperine and Piperanine from the hexane extract of

P. nigrum have a binding free energy of -7.3 kcal/mol and interact with residues SER 403, GLY 599, SER 598, THR 582, GLU 460, and ARG 445, indicating significant anti-MRSA activity supported by the major component Diisooctyl phthalate. Minor components such as β-caryophyllene oxide, Alpha-caryophylladienol, and Piperolein B also contribute to the anti-MRSA activity of this plant extract, with binding free energies ranging from 6.8 to 7.1 kcal/mol. In the

P. betle extract, the major compounds Hydroxychavicol (81.89%) and Chavibetol (12.01%) show binding free energies of 5.4 and 5.6 kcal/mol, respectively, interacting with the residues LYS 406, SER 403, SER 462, GLY 599, ASN 464, and THR 600. This interaction indicates significant anti-MRSA potential, although lower than that of Piperine.

For the 4CJN target protein (

Figure 8), the native ligand has a binding free energy of -7.2 kcal/mol and interacts with the residues LYS 273, ALA 276, and ASP 295 [

48]. Meanwhile, ciprofloxacin has a binding free energy of -6.2 kcal/mol and interacts with LYS 273, LYS 316, and GLU 294.

Piperine in the

P. nigrum extract has a binding free energy of -6.5 kcal/mol and a stronger interaction at residue 276 than the positive control. Piperanine shows a favorable binding free energy of -6.0 kcal/mol, with interactions at ASP 295, VAL 277, and GLN 292, supporting the anti-MRSA activity, along with β-caryophyllene oxide and Diisooctyl phthalate, although Piperolein B does not show an H-bond interaction with this target protein. Meanwhile, in the

P. betle extract, hydroxyychavicol and chavibetol showed binding free energies of 4.9 and 4.6 kcal/mol, respectively. The extract interacted with residues ASP 275, ASP 295, and GLY 296, indicating a contribution to anti-MRSA activity, although lower compared to

P.

nigrum. The

in vitro assays demonstrated that extracts containing major compounds such as Piperine [

40], Diisooctyl phthalate, and Hydroxychavicol [

44] from Clusters 6 and 5 were significantly effective in inhibiting MRSA growth. These results were consistent with the GC-MS results, which showed high concentrations of Piperine (14.22%) and Diisooctyl phthalate (14.67%) in the hexane extract of

P. nigrum fruits, as well as Hydroxychavicol (81.89%) and Chavibetol (12.01%) in the aquadest extract of

P. betle. Both proteins contribute to significant anti-MRSA activity. Docking analysis showed that these compounds strongly bind to key residues in MRSA target proteins, reinforcing the potential as effective antimicrobial agents.

5. Conclusions

This study showed the successful optimization of extraction processes with methanol generally yielding the highest extracts across different parts of both P. betle and P. nigrum, particularly in the fruits. This underscores the suitability of methanol as an extraction solvent. Hexane produced lower yields, while aquadest was moderately effective, especially for leaves and fruits. This optimization is crucial for selecting the most efficient solvent based on the desired yield and plant characteristics. The results demonstrated the significant potential of P. betle and P. nigrum as promising anti-MRSA agent sources. By using comprehensive FTIR spectroscopy combined with CA and GC-MS, several bioactive compounds were identified, including Piperine, Diisooctyl phthalate, and Hydroxychavicol. These compounds showed strong binding affinities with key MRSA protein targets (4DKI, 6H5O, and 4CJN), as evidenced by molecular docking studies, with a strong correlation between in silico and in vitro results, confirming the effectiveness in inhibiting MRSA growth. The integration of in silico docking studies with in vitro assays provided a robust framework for identifying and validating potential anti-MRSA agents. Piperine, particularly as a major compound in P. nigrum, demonstrated substantial antimicrobial activity, while hydroxychavicol in P. betle showed significant inhibitory effects against MRSA. These results emphasize the importance of using a combined approach in drug discovery for identifying new antimicrobial agents. Further investigations are needed into Piper species as natural sources of novel anti-MRSA compounds with potential for development into effective treatments against resistant bacteria strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y., A.R., and A.J.; methodology, B.Y., A.R., R.T., K.K. and N.A.; software, B.Y. and A.R.; validation, B.Y., A.R. and G.A.; formal analysis, B.Y. and A.R.; investigation, S.M., S.R., R.A. and N.N.; resources, B.Y., R.T., K.K. and N.A.; data curation, B.Y., A.R. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y., A.J. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, B.Y., A.J., and A.R.; visualization, B.Y. and A.J.; supervision, B.Y. and A.R.; project administration, S.M. and S.R.; funding acquisition, B.Y. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, and Teknologi Direktorat Jenderal Pendidikan Tinggi, Riset, and Teknologi, grant number 2383/E2/DT.01.00/2023 and The APC was funded by Prof. Abdul Rohman and Dr. Budiman Yasir.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are included within the article. Additional information or datasets generated and analyzed during the research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were used or generated in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the Almarisah Madani University to providing the essential laboratory facilities. Furthermore, the author is grateful to all collaborators and institutions for the invaluable contributions and technical assistance, which have been instrumental in the successful completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bashabsheh, R.H.; Al-Fawares, O.L.; Natsheh, I.; Bdeir, R.; Al-Khreshieh, R.O.; Bashabsheh, H.H. Staphylococcus aureus Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Application of Nano-Therapeutics as a Promising Approach to Combat Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens Glob. Health 2024, 118, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanayakkara, A.K.; Boucher, H.W.; Fowler, V.G. Jr.; Jezek, A.; Outterson, K.; Greenberg, D.E. Antibiotic Resistance in the Patient with Cancer: Escalating Challenges and Paths Forward. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovich, K.J.; Aureden, K.; Ham, D.C.; Harris, A.D.; Hessels, A.J.; Huang, S.S.; et al. SHEA/IDSA/APIC Practice Recommendation: Strategies to Prevent Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Transmission and Infection in Acute-Care Hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1039–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cortés, L.E.; Gálvez-Acebal, J.; Rodríguez-Baño, J. Therapy of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia: Evidences and Challenges. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubair, N.; Rajagopal, M.; Chinnappan, S.; Abdullah, N.B.; Fatima, A. Review on the Antibacterial Mechanism of Plant-Derived Compounds Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria (MDR). Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021, 3663315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Nguyen, H.C.; Do, N.H.; Le, P.K. Recent Applications of Natural Bioactive Compounds from Piper betle (L.) Leaves in Food Preservation. Food Control 2023, 110026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.S.; Mishra, S. Natural Products as Antiparasitic, Antifungal, and Antibacterial Agents. Drugs from Nature: Targets, Assay Systems and Leads 2024, 367–409.

- Ueda, J.M.; Milho, C.; Heleno, S.A.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Carpena, M.; Alves, M.J.; et al. Emerging Strategies to Combat Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Natural Agents with High Potential. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.A. Review on Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Natural Sources Using Green Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 878–912. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, N.; Gautam, B.S. Piper betle: Deep Insights into the Pharmacognostic and Pharmacological Perspectives. Int. J. Med. Phar. Sci. 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vaquero, M.; Ummat, V.; Tiwari, B.; Rajauria, G. Exploring Ultrasound, Microwave and Ultrasound–Microwave Assisted Extraction Technologies to Increase the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidants from Brown Macroalgae. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakasan, G.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Aguirre-Becerra, H.; García, E.R.; Nieto-Ramírez, M.I. Preliminary Screening on Antibacterial Crude Secondary Metabolites Extracted from Bacterial Symbionts and Identification of Functional Bioactive Compounds by FTIR, HPLC, and Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2024, 29, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, A.; Kamaraj, S.; Bhakti, M.A.; Kumari, C.; Kulshrestha, S.; Pandohee, J.; That, L.F.L.N. Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds in Honey Using Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. In: Advanced Techniques of Honey Analysis; Academic Press: 2024; pp. 287–307.

- Cucinotta, L.; Rotondo, A.; Coppolino, S.; Salerno, T.M. Gas Chromatographic Techniques and Spectroscopic Approaches for a Deep Characterization of Piper gaudichaudianum Kunth Essential Oil from Brazil. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 465208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, A. Metabolomics-and Systems-Biology-Guided Discovery of Metabolite Lead Compounds and Druggable Targets. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taibi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Ou-Yahia, D.; Dalli, M.; Bellaouchi, R.; Tikent, A.; et al. Assessment of the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential of Ptychotis verticillata Duby Essential Oil from Eastern Morocco: An In Vitro and In Silico Analysis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, B.; Astuti, A.D.; Raihan, M.; Natzir, R.; Subehan, S.; Rohman, A.; Alam, G. Optimization of Pagoda (Clerodendrum paniculatum L.) Extraction Based on Analytical Factorial Design Approach, Its Phytochemical Compound, and Cytotoxicity Activity. Egypt J. Chem. 2022, 65, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, B.; Budiman, Alam, G. Chemometrics-Assisted Fingerprinting Profiling of Extract Variation from Pagoda (Clerodendrum paniculatum L.) Using TLC-Densitometric Method. Egypt J. Chem. 2023, 66, 1589–1596. 2023, 66, 1589–1596.

- Roshan, M.; Singh, I.; Vats, A.; Behera, M.; Singh, D.P.; Gautam, D.; et al. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Effect of Cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Causing Bovine Mastitis. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 1–14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, M.; Frígols, B.; Serrano-Aroca, A. Antimicrobial Characterization of Advanced Materials for Bioengineering Applications. JoVE 2018, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Alharthi, S.S. Bioactive Extracts of Plant Byproducts as Sustainable Solution of Water Contaminants Reduction. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, D.; Zachariah, T.J. Volatile and Non-Volatile Metabolite Profiling of Under-Explored Crop Piper colubrinum Link: With Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Approach and Its Biochemical Diversity from Medicinally Valued Piper Species. J. Chromatogr. B 2024, 124260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, P. High Throughput Virtual Screening and Validation of Plant-Based EGFR L858R Kinase Inhibitors Against Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: An Integrated Approach Utilizing GC–MS, Network Pharmacology, Docking, and Molecular Dynamics. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrarti, W.; Umar, A.H.; Syahruni, R.; Rafi, M.; Kusuma, W.A. Deciphering the Mechanism of Action Cosmos caudatus Compounds Against Breast Neoplasm: A Combination of Pharmacological Networking and Molecular Docking Approach with Bibliometric Analysis. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 9, 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Bui, Q.T.P. Simultaneous Determination of Active Compounds in Piper betle Linn. Leaf Extract and Effect of Extracting Solvents on Bioactivity. Eng. Rep. 2020, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajopadhye, A.A.; Namjoshi, T.P.; Upadhye, A.S. Rapid Validated HPTLC Method for Estimation of Piperine and Piperlongumine in Root of Piper longum Extract and Its Commercial Formulation. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012, 22, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xiang, J.Y.; Yuan, H.Y.; Wu, J.Q.; Li, H.Z.; Shen, Y.H.; Xu, M. Isolation, Synthesis and Absolute Configuration of 4,5-Dihydroxypiperines Improving Behavioral Disorder in AlCl3-Induced Dementia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 42, 128057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nik, W.W.; Ravindran, K.; Al-Amiery, A.A.; Izionworu, V.O.; Fayomi, O.S.I.; Berdimurodov, E.; Daoudi, W.; Zulkifli, F.; Dhande, D.Y. Piper betle Extract as an Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor for Aluminium Alloy in Hydrochloric Acid Media. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2023, 12, 948–960. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgani, L.; Mohammadi, M.; Najafpour, G.D.; Nikzad, M. Sequential Microwave-Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Isolation of Piperine from Black Pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Qin, X.W.; Hu, R.S.; Hu, L.S.; Wu, B.D.; Hao, C.Y. Studies on the Chemical and Flavour Qualities of White Pepper (Piper nigrum L.) Derived from Grafted and Non-Grafted Plants. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 2601–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, B.; Sarma, V.U.M.; Kumar, K.; Babu, K.S.; Devi, P.S. Simultaneous Determination of Six Marker Compounds in Piper nigrum L. and Species Comparison Study Using High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Planar Chromatogr. 2015, 28, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateesh Reddy, K.; Siva, B.; Divya Reddy, S.; Kumar, K.; Pratap, T.V.; Vidyasagar Reddy, K.; Venkateswara Rao, B.; Suresh Babu, K. Monitoring of Chemical Markers in Extraction of Traditional Medicinal Plants (Piper nigrum, Curcuma longa) Using In Situ ReactIR. J. AOAC Int. 2021, 104, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, T.A.; Sanagi, M.M.; Wan Ibrahim, W.A.; Ahmad, F.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Determination of 4-Allyl Resorcinol and Chavibetol from Piper betle Leaves by Subcritical Water Extraction Combined with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Food Anal. Methods 2014, 7, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, N.L.; Mustapa Kamal, S.M.; Sulaiman, A.; Taip, F.S.; Siajam, S.I. Subcritical Water Extraction of Total Phenolic Compounds from Piper betle L. Leaves: Effect of Process Conditions and Characterization. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5606–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguettaya, A.; Yu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Song, A. Efficient Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, J. Classification and Identification of Rhodobryum roseum Limpr. and Its Adulterants Based on Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Chemometrics. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantorn, P.; Tipmanee, V.; Wanna, W.; Prapasarakul, N.; Visutthi, M.; Sotthibandhu, D.S. Potential Natural Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Properties of Piper betle L. Against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Methicillin-Resistant Strains. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 317, 116820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.J.; Humma, Z.E.; Omer, M.O.; Sattar, A.; Altaf, I.; Chen, Z.; He, N. Effects of Curcuma longa L. and Piper nigrum L. Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Infectious Angiogenesis. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2024, 18, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umapathy, V.R.; Dhanavel, A.; Kesavan, R.; Natarajan, P.M.; Bhuminathan, S.; Vijayalakshmi, P. Anticancer Potential of the Principal Constituent of Piper nigrum, Piperine: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e44287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Malik, M.; Dastidar, D.G.; Roy, R.; Paul, P.; Sarkar, S.; Tribedi, P. Piperine, a Phytochemical, Prevents the Biofilm Formation of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A Biochemical Approach to Understand the Underlying Mechanism. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 189, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirrao, P.; Tambat, R.; Chandal, N.; Mahey, N.; Kamboj, A.; Jain, U.K.; Singh, I.P.; Jachak, S.M.; Nandanwar, H.S. MsrA Efflux Pump Inhibitory Activity of Piper cubeba L.f. and Its Phytoconstituents Against S. aureus RN4220. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driche, E.H.; Belghit, S.; Bijani, C.; Zitouni, A.; Sabaou, N.; Mathieu, F.; Badji, B. A New Streptomyces Strain Isolated from Saharan Soil Produces Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate, a Metabolite Active Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamakshshari, N.; Ahmed, I.A.; Nasharuddin, M.N.; Hashim, N.M.; Mustafa, M.R.; Othman, R.; Noordin, M.I. Effect of Extraction Procedure on the Yield and Biological Activities of Hydroxychavicol from Piper betle L. Leaves. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 24, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leesombun, A.; Sungpradit, S.; Bangphoomi, N.; Thongjuy, O.; Wechusdorn, J.; Riengvirodkij, S.; Boonmasawai, S. Effects of Piper betle Extracts Against Biofilm Formation by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Isolated from Dogs. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, I.; Louis, H.; Ekpen, O.F.; Gber, T.E.; Gideon, M.E.; Ahmad, I.; Ejiofor, E.U. Modeling the Anti-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Activity of (E)-6-Chloro-N2-Phenyl-N4-(4-Phenyl-5-(Phenyl Diazinyl)-2λ3,3λ2-Thiazol-2-yl)-1,3,5-Triazine-2,4-Diamine. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2023, 43, 7942–7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, A.L.; Gretes, M.C.; Safadi, S.S.; Danel, F.; De Castro, L.; Page, M.G.; Strynadka, N.C. Structural Insights into the Anti-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Activity of Ceftobiprole. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32096–32102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janardhanan, J.; Bouley, R.; Martínez-Caballero, S.; Peng, Z.; Batuecas-Mordillo, M.; Meisel, J.E.; Chang, M. The Quinazolinone Allosteric Inhibitor of PBP 2a Synergizes with Piperacillin and Tazobactam Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouley, R.; Kumarasiri, M.; Peng, Z.; Otero, L.H.; Song, W.; Suckow, M.A.; Mobashery, S. Discovery of Antibiotic (E)-3-(3-Carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-Cyanostyryl) Quinazolin-4(3H)-One. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1738–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The main effects plot of the variables are crucial for influencing the % yield of the extract.

Figure 1.

The main effects plot of the variables are crucial for influencing the % yield of the extract.

Figure 2.

The interaction plots display various data models for each factor variable in relation to the % yield of the extracts.

Figure 2.

The interaction plots display various data models for each factor variable in relation to the % yield of the extracts.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of

Piper extracts (stem, leaf, and fruit), extracted using aquadest, methanol, and hexane. For identification of samples 1 to 18, refer to

Table 1.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of

Piper extracts (stem, leaf, and fruit), extracted using aquadest, methanol, and hexane. For identification of samples 1 to 18, refer to

Table 1.

Figure 4.

The dendrogram illustrating the classification of samples through cluster analysis (CA), with samples in clusters 1 to 6 represented by distinct colored lines for each respective cluster.

Figure 4.

The dendrogram illustrating the classification of samples through cluster analysis (CA), with samples in clusters 1 to 6 represented by distinct colored lines for each respective cluster.

Figure 5.

GC-MS Spectra of aquadest extract from

Piper betle fruit (red line) and hexane extract from

Piper nigrum fruit (green line). Compounds 1-12 are major compounds found in the extracts with concentrations >1%, as detailed in

Table 3.

Figure 5.

GC-MS Spectra of aquadest extract from

Piper betle fruit (red line) and hexane extract from

Piper nigrum fruit (green line). Compounds 1-12 are major compounds found in the extracts with concentrations >1%, as detailed in

Table 3.

Figure 6.

Structure of the MRSA protein target (4DKI) (C) along with the native ligand (Ceftobiprole) (B). The re-docking of the native ligand (co-crystal) into the MRSA protein target pocket validates the method, resulting in a root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.991 Å (A). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (4DKI) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Figure 6.

Structure of the MRSA protein target (4DKI) (C) along with the native ligand (Ceftobiprole) (B). The re-docking of the native ligand (co-crystal) into the MRSA protein target pocket validates the method, resulting in a root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.991 Å (A). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (4DKI) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Figure 7.

MRSA protein target (6H5O) structure (F), the native ligand (Piperacillin) (E) and re-docking native ligand (co-crystal) result in MRSA protein target pocket for validate the method with RMSD value of 0.991 Å (D). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (6H5O) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Figure 7.

MRSA protein target (6H5O) structure (F), the native ligand (Piperacillin) (E) and re-docking native ligand (co-crystal) result in MRSA protein target pocket for validate the method with RMSD value of 0.991 Å (D). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (6H5O) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Figure 8.

MRSA protein target (4CJN) Structure (I), the native ligand (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)benzoic acid (H) and re-docking native ligand (co-crystal) result in MRSA protein target pocket for validate the method with RMSD value of 0.751 Å (G). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (4CJN) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Figure 8.

MRSA protein target (4CJN) Structure (I), the native ligand (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)benzoic acid (H) and re-docking native ligand (co-crystal) result in MRSA protein target pocket for validate the method with RMSD value of 0.751 Å (G). Additionally, the interactions of compounds 1-8, the native ligand, and the positive control with the MRSA protein target (4CJN) were illustrated, highlighting their binding affinities and interactions within the target pocket.

Table 1.

Percentage yield of extracts from different solvents and parts of Piper plants.

Table 1.

Percentage yield of extracts from different solvents and parts of Piper plants.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity of Piper extracts against MRSA based on inhibition zone diameter (mm) for different plant parts and solvents.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity of Piper extracts against MRSA based on inhibition zone diameter (mm) for different plant parts and solvents.

Sample

Code |

Inhibition Zone (mm) |

Tukey Simultaneous Tests for Differences of Means |

| Difference of Levels |

Differenceof Means |

SE ofDifference |

95% CI |

T-Value |

AdjustedP-Value |

| 1 |

8 |

4 - 1 |

-2.667 |

0.797 |

(-5.388, 0.055) |

-3.35 |

0.056 |

| 1 |

10 |

7 - 1 |

4.667 |

0.797 |

(1.945, 7.388) |

5.86 |

0.001 |

| 1 |

9 |

8 - 1 |

5.667 |

0.797 |

(2.945, 8.388) |

7.11 |

0.000 |

| 4 |

6 |

11 - 1 |

5.000 |

0.797 |

(2.279, 7.721) |

6.27 |

0.000 |

| 4 |

6 |

16 - 1 |

10.333 |

0.797 |

(7.612, 13.055) |

12.97 |

0.000 |

| 4 |

7 |

Ciprofloxacin - 1 |

16.667 |

0.797 |

(13.945, 19.388) |

20.92 |

0.000 |

| 7 |

14 |

7 - 4 |

7.333 |

0.797 |

(4.612, 10.055) |

9.20 |

0.000 |

| 7 |

14 |

8 - 4 |

8.333 |

0.797 |

(5.612, 11.055) |

10.46 |

0.000 |

| 7 |

13 |

11 - 4 |

7.667 |

0.797 |

(4.945, 10.388) |

9.62 |

0.000 |

| 8 |

14 |

16 - 4 |

13.000 |

0.797 |

(10.279, 15.721) |

16.31 |

0.000 |

| 8 |

15 |

Ciprofloxacin - 4 |

19.333 |

0.797 |

(16.612, 22.055) |

24.26 |

0.000 |

| 8 |

15 |

8 - 7 |

1.000 |

0.797 |

(-1.721, 3.721) |

1.25 |

0.861 |

| 11 |

14 |

11 - 7 |

0.333 |

0.797 |

(-2.388, 3.055) |

0.42 |

0.999 |

| 11 |

14 |

16 - 7 |

5.667 |

0.797 |

(2.945, 8.388) |

7.11 |

0.000 |

| 11 |

14 |

Ciprofloxacin - 7 |

12.000 |

0.797 |

(9.279, 14.721) |

15.06 |

0.000 |

| 16 |

20 |

11 - 8 |

-0.667 |

0.797 |

(-3.388, 2.055) |

-0.84 |

0.976 |

| 16 |

19 |

16 - 8 |

4.667 |

0.797 |

(1.945, 7.388) |

5.86 |

0.001 |

| 16 |

19 |

Ciprofloxacin - 8 |

11.000 |

0.797 |

(8.279, 13.721) |

13.80 |

0.000 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

24 |

16 - 11 |

5.333 |

0.797 |

(2.612, 8.055) |

6.69 |

0.000 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

28 |

Ciprofloxacin - 11 |

11.667 |

0.797 |

(8.945, 14.388) |

14.64 |

0.000 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

25 |

Ciprofloxacin - 16 |

6.333 |

0.797 |

(3.612, 9.055) |

7.95 |

0.000 |

Table 3.

GC-MS analysis of compounds in hexane extract of Piper nigrum fruit (green line) and aquadest extract of Piper betle fruit (red line).

Table 3.

GC-MS analysis of compounds in hexane extract of Piper nigrum fruit (green line) and aquadest extract of Piper betle fruit (red line).

GC-MS

Peaks |

Compounds |

Molecular Formula |

MW

(g/mol) |

PubChem (CID) |

RT

(min) |

Area (%) |

SI (%) |

| (Green line) Piper nigrum fruit |

| 1 |

Beta-caryophyllene oxide |

C15H24O |

220 |

1742210 |

13.563 |

1.01 |

97 |

| 2 |

Alpha-caryophylladienol |

C15H24O |

220 |

14524923 |

14.276 |

1.69 |

97 |

| 3 |

Pellitorine |

C14H25NO |

223 |

5318516 |

18.772 |

5.08 |

93 |

| 4 |

n-Hexadecanoic acid |

C16H32O2

|

256 |

985 |

19.279 |

2.51 |

96 |

| 5 |

Octadecanoic acid |

C18H36O2

|

284 |

5281 |

23.877 |

1.42 |

93 |

| 6 |

Diisooctyl phthalate |

C24H38O4

|

390 |

33934 |

31.081 |

14.67 |

95 |

| 7 |

(2E,4E)-N-Isobutylhexadeca-2,4-dienamide |

C20H37NO |

307 |

6442402 |

31.595 |

1.78 |

90 |

| 8 |

Piperanine |

C17H21NO3

|

287 |

5320618 |

32.804 |

4.03 |

94 |

| 9 |

Piperine |

C17H19NO3

|

285 |

638024 |

37.762 |

14.22 |

93 |

| 10 |

Piperolein B |

C21H29NO3

|

343 |

21580213 |

41.639 |

1.58 |

93 |

| (Red line) Piper betle fruit |

| 11 |

Chavibetol |

C10H12O2

|

164 |

596375 |

10.420 |

12.01 |

97 |

| 12 |

Hydroxychavicol |

C9H10O2

|

150 |

70775 |

12.496 |

81.89 |

93 |

Table 4.

Bond-free energy values and amino acid residues binding to MRSA protein targets (4DKI, 6H5O, and 4CJN).

Table 4.

Bond-free energy values and amino acid residues binding to MRSA protein targets (4DKI, 6H5O, and 4CJN).

| Peak/ Compounds |

Protein Target |

Compounds |

Bond-free energy (kcal/mol) |

H-bond Interaction |

| Native ligand |

4DKI |

Ceftobiprole |

-9.8 |

LYS 406, SER 462, ASN 464, GLN 521, THR 600 |

| Positive control |

Ciprofloxacin |

-8.3 |

LYS 406, SER 462, SER 643 |

| 1 |

Beta-caryophyllene oxid |

-6.4 |

NI |

| 2 |

Alpha-caryophylladienol |

-6.4 |

NI |

| 3 |

Diisooctyl phthalate |

-7.1 |

SER 462, TYR 446 |

| 4 |

Piperanine |

-7.6 |

LYS 406, SER 462 |

| 5 |

Piperine |

-7.7 |

GLN 521, THR 444, GLY 402, SER 400 |

| 6 |

Piperolein B |

-8.3 |

LYS 406, SER 462, ASN 464 |

| 7 |

Chavibetol |

-5.7 |

THR 600, ASN 464, SER 462, LYS 406 |

| 8 |

Hydroxychavicol |

-5.7 |

SER 462, ASN 464, SER 403 |

| Native ligand |

6H5O |

Piperacillin |

-9.0 |

THR 444, SER 598, SER 461, SER 403, LYS 406, ASN 464 |

| Positive control |

Ciprofloxacin |

-8.1 |

LYS 406, SER 403, SER 462, SER 643 |

| 1 |

Beta-Caryophyllene oxide |

-6.9 |

ASN 464, LYS 406 |

| 2 |

Alpha-Caryophylladienol |

-7.1 |

SER 403, SER 462 |

| 3 |

Diisooctyl phthalate |

-6.3 |

ASN 464, THR 600 |

| 4 |

Piperanine |

-7.3 |

SER 598, THR 582, GLU 460, ARG 445 |

| 5 |

Piperine |

-7.3 |

SER 403, GLY 599 |

| 6 |

Piperolein B |

-6.8 |

ASN 464, SER 598, HIS 583 |

| 7 |

Chavibetol |

-5.4 |

SER 403, ASN 464, SER 462, THR 600 |

| 8 |

Hydroxychavicol |

-5.6 |

LYS 406, SER 403, SER 462, GLY 599 |

| Native ligand |

4CJN |

(E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)benzoic acid |

-7.2 |

LYS 273, ALA 276, ASP 295 |

| Positive control |

Ciprofloxacin |

-6.2 |

LYS 273, LYS 316, GLU 294 |

| 1 |

Beta-caryophyllene oxide |

-5.2 |

ASN 146 |

| 2 |

Alpha-caryophylladienol |

-5.2 |

NI |

| 3 |

Diisooctyl phthalate |

-5.0 |

LYS 273 |

| 4 |

Piperanine |

-6.0 |

ASP 295, VAL 277, GLN 292 |

| 5 |

Piperine |

-6.5 |

ALA 276 |

| 6 |

Piperolein B |

-5.9 |

NI |

| 7 |

Chavibetol |

-4.6 |

ASP 295, GLY 296 |

| 8 |

Hydroxychavicol |

-4.9 |

ASP 275 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).