Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

12 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Remote Sensing Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Unique Publications, Exposures, and Specific Outcomes

3.2. AOD-Air Pollution

| AOD group1 | Outcome total2 |

AOD-Air pollution | PGR2PER | ||

| Mean3-4 | 95% CI3 | Mean3-4 | 95% CI3 | ||

| PM2.5: Both | 74 | 25.6 | 20.8-30.4 | . | . |

| No | 21 | 21.7 | 13.5-29.9 | . | . |

| Yes | 53 | 27.2 | 21.1-33.2 | 81.2 | 79.0-83.3 |

| PM10: Yes | 19 | 48.7 | 35.6-61.8 | 79.4 | 76.1-82.7 |

| NO2: Both | 15 | 10.4 | 6.5-14.2 | . | . |

| No | 1 | 0.8 | . | . | . |

| Yes | 14 | 11.0 | 7.2-14.9 | 73.0 | 66.4-79.7 |

3.3. Risk Factors and Significant Outcome Group

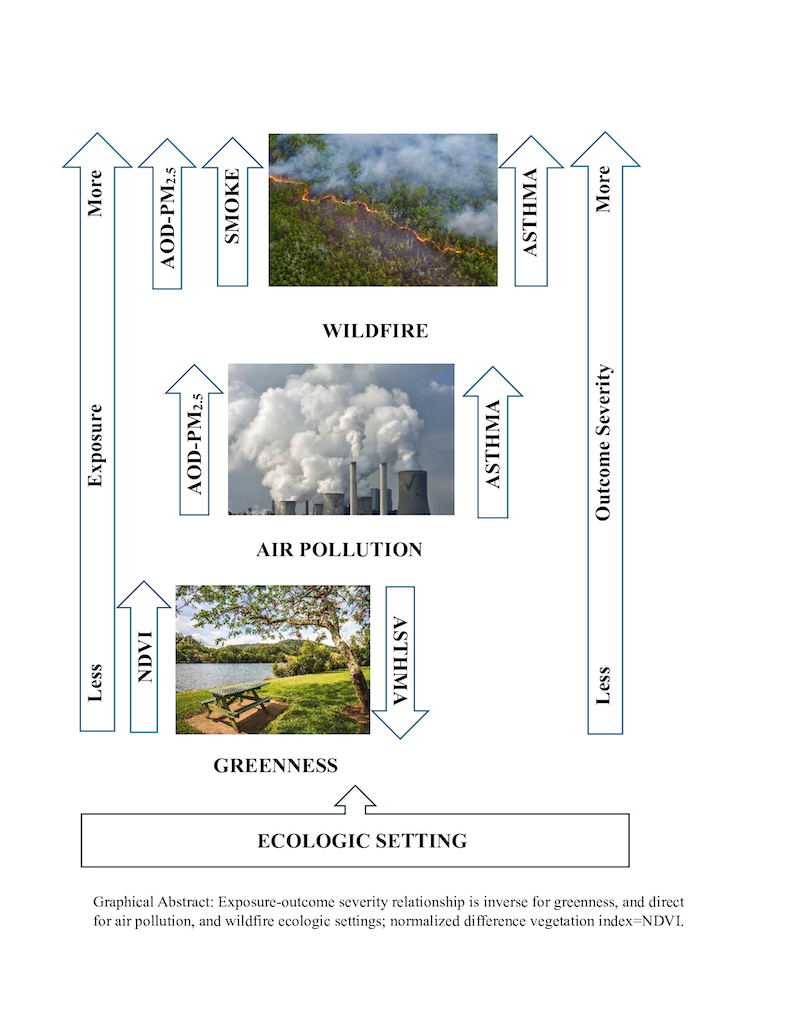

3.4. Exposure-Outcome Severity and Country Differences

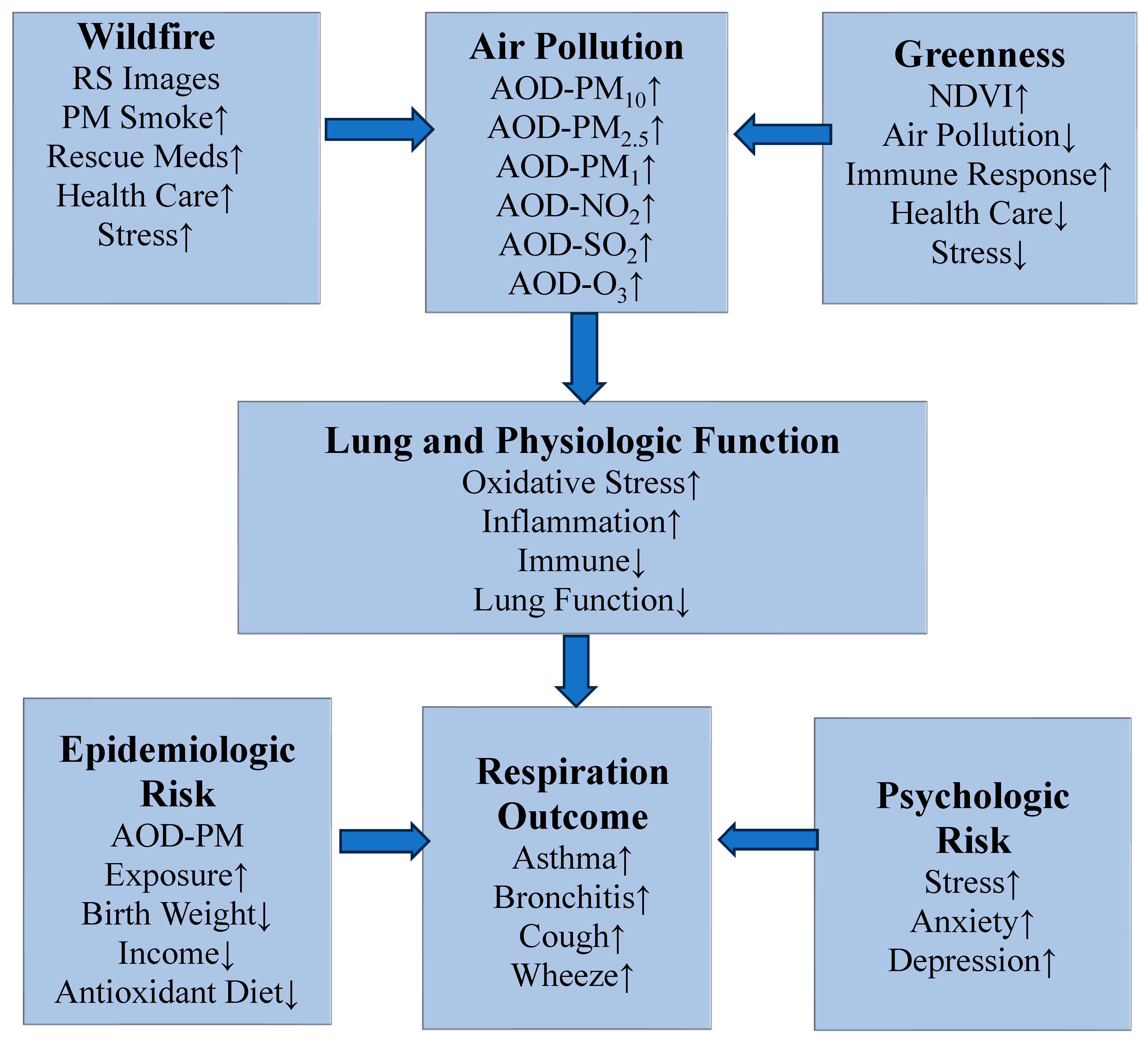

3.5. Risk Factors, Health Outcomes, and Ecologic Settings

3.6. Individual and Total Physiologic Mechanisms

3.7. Ecologic Setting-Specific Asthma, and Physiologic Outcomes

3.7.1. Greenness

- NDVI, Immune, and Inflammation. Results from four published studies that evaluated the contribution of NDVI to asthma outcomes, suggest that, while the relationship is complex, higher NDVI values contribute to improved asthma outcomes [39,68,71,75]. Chen and colleagues [39] found lower FeNO values, indicative of decreased airway inflammation, and more glucocorticoid receptors cells (CD4), suggesting the occurrence of improved immune function, with higher NDVI values within 250 m buffers that included study participants’ residences and improved family relationships between parents and asthma study participants. Another publication by Squillacioti and collaborators [75] found an inverse association between higher NDVI readings and decreased asthma risk, as well as improved lung function in 10-13 year-old children. The Cilluffo and associates [68] publication also found an inverse association between lower NDVI values and higher risk for uncontrolled asthma in 5-16 year-old children. Exposure to passive smoke during the mothers’ pregnancy and higher crowding were aversive risk factors for uncontrolled asthma. The uncontrolled asthma group had lower lung function than the controlled asthma group, i.e., lower FEV1, FEF25%-75%, and FEV1/FVC measurements. Hartley and collaborators [71] completed a prospective study to evaluate the contribution of NDVI to asthma incidence and lung function by age of seven years. Children sensitized to common allergens developed asthma if they were exposed to higher NDVI values compared to children who were not sensitized to common allergens. In all children, however, those with asthma and other children without asthma, the results showed that higher NDVI values contributed to increased lung function, measured as percent of forced expiratory flow in one second (%FEV1, and percent of forced vital capacity (%FVC).

- Remote Sensing Greenness, Asthma, and Psychologic Risk Factors. Ihlebaek and colleagues [74] assessed the contribution of remote sensing greenness to asthma, and self-reported psychologic disorders in adult study participants residing in Oslo, Norway. Results showed no association with asthma, but higher greenness levels were associated with fewer self-reported mental disorders.

3.7.2. Air Pollution

- Preexposure and Asthma Incidence. Nine studies [4,5,6,8,9,22,23,24,86] in the air pollution ecologic setting showed that prenatal and infant exposure to ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings resulted in increased asthma [5,6,9,22,24], wheeze [4,8,9,23,24], and allergic rhinitis [86] incidence in early childhood. Some publications reported minimum ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level reading thresholds, while other studies identified risk factors: Prenatal values were 93 µg/m3 [22], and 64.7 µg/m3 [24], and infant values were 73 µg/m3 [22], and 61.8 µg/m3 [24]. Prenatal exposures to ambient AOD-PM2.5 constituents of black carbon, organic matter, nitrate, ammonium, and sulfate resulted in higher asthma and wheeze incidence [24]. Follow-up results from the initial ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level reading exposure until the subsequent occurrence of increases in asthma, wheeze and allergic rhinitis incidence in early childhood provided the necessary information to investigators to evaluate the contribution of exposure to outcome severity by utilizing distributed lag statistical models [5,6,22]. Critical exposure windows were defined as the occurrence of significant increases in childhood asthma, wheeze, and allergic rhinitis incidence resulting from prior exposure to ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings within a discrete temporal window before and after birth [4,5,6,22,23]. The prenatal and infant lower-upper critical exposure window boundaries were 6-22 weeks [22], 16-25 weeks [5], 19-23 weeks [6], 1st trimester [4], 6-22 weeks prenatally, and 9-46 weeks [22], and 5.5-11 moths [9] in infancy. Additional analyses also identified risk factors. Risk factors included gender [5,6,24], breastfeeding duration less than six months [9], race [8], limited economic resources, less than 12 years of education [8], lower antioxidant dietary intake [8], exposure to environmental tobacco smoke [23], and maternal stress [4,6]. These ambient AOD-air pollution preexposure publications also concluded that inferred changes in the physiologic mechanisms of immune, inflammation, and oxidative stress contributed to delays in lung development, including irreversible anatomical changes to the lungs [4,5,6,9,22,23]. It is possible that persons who developed asthma because of prenatal and infant exposure to higher ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings and exposure to ambient AOD-PM2.5 constituents could manifest a type of asthma in early childhood that is more severe, harder to manage, and treat.

- Air Pollution, Asthma and Lung Function. Knibbs and colleagues [25] evaluated the contribution of ambient AOD-NO2 concentration level readings to asthma prevalence and lung function. Ambient AOD-NO2 concentration level readings were proxies for vehicular traffic volume in 12 Australian cities. Higher ambient AOD-NO2 concentration level readings contributed to higher asthma prevalence risk. Higher ambient AOD-NO2 concentration level readings also contributed to decreased lung function, measured as lower FEV1, FVC, and increased inflammation, evaluated as higher FeNO measurements. Another study undertaken by Rice and colleagues [19] evaluated the contribution of ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings to decreased lung function. Living <100 m from highways contributed to increased asthma risk in adults. Compared to adults living >400 m from highways, those study participants that lived <100 m of highways had decreased lung function, measured as lower FEV1 and FVC values. Study participants who were former smokers showed an annual FEV1 decrease of 4.9 ml. Xing and collaborators [7] evaluated the contribution of ambient AOD-air pollution concentration level readings to asthma prevalence in adults living at higher altitudes in China. Higher ambient AOD-PM2.5 and ambient AOD-PM10 concentration level readings contributed to the occurrence of increased asthma risk. Only higher ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings, but not higher ambient AOD-PM10 concentration level readings, also contributed to decreased lung function, which was measured as a decrease in FEV1, FEV50%, and FEV75%. Older age, defined as persons who were at least 65 years old, and the presence of mold (and by implication higher moisture levels and humidity) in the homes of study participants were risk factors for higher asthma prevalence risk.

- Maternal Depression, Asthma and Wheeze. Alcala and collaborators [78] utilized a longitudinal study design to evaluate the contribution of maternal depression to the occurrence of asthma and wheeze in children. Mothers who had postpartum and recurrent depression had children who developed asthma and current wheeze by their fourth birthday. The contribution of maternal depression to asthma and wheeze was stronger in female children than in male children.

3.7.3. Wildfires

- Ambient AOD-PM2.5 Without and With Wildfire Smoke. The Delfino and associates [55] publication results demonstrated higher ambient AOD-PM2.5+smoke concentration level readings during wildfires compared to ambient AOD-PM2.5 concentration level readings before and after wildfires. The mean ambient AOD-PM2.5+smoke concentration level reading during wildfires was 70 µg/m3 higher than the before wildfire condition. There were also 34% more asthma admissions during the wildfire compared to the before wildfire condition. Persons in the 65-99 age group showed the highest increase in asthma admissions compared to other age groups. Under the wildfire condition there was also an increase in acute bronchitis admissions.

- Wildfire-Smoke, Asthma and Lung Function. Lipner and co-workers [40] evaluated the contribution of wildfire smoke to asthma control and lung function in 4-21 year-old study participants. This study utilized National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System and on-the-ground ambient monitor PM2.5 measurements. In 12-21 year-old children, results showed no association with asthma control, but higher ambient PM2.5 monitor measurements were inversely associated with decreased lung function, which was measured as FEV1 values, on the next day. FEV1 measurements increased on the second day. The improvement in lung function on the second day was due to the use of asthma rescue medication. In 4-11 year-old children there were no significant outcome due to higher ambient monitor PM2.5 measurements. Risk factors were White race, and male gender. There was also worse asthma control in Black children, and among study participants of lower social-economic status.

3.8. Descriptive Physiologic Asthma and Other Respiration Model

3.9. Asthma and Other Respiration Population-Based Intervention Programs

4. Discussion of Review Paper’s Objectives

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC-NCHS. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm.

- CDC-NCHS. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Secondary International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd-10-cm.htm.

- Anderson HR, Butland BK, van Donkelaar A, et al. Satellite-based estimates of ambient air pollution and global variations in childhood asthma prevalence. Environmental health perspectives 2012;120(9):1333-9. [CrossRef]

- Rosa MJ, Just AC, Kloog I, et al. Prenatal particulate matter exposure and wheeze in Mexican children: Effect modification by prenatal psychosocial stress. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;119(3):232-37.e1. [CrossRef]

- Hsu HH, Chiu YH, Coull BA, et al. Prenatal Particulate Air Pollution and Asthma Onset in Urban Children. Identifying Sensitive Windows and Sex Differences. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2015;192(9):1052-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee A, Leon Hsu HH, Mathilda Chiu YH, et al. Prenatal fine particulate exposure and early childhood asthma: Effect of maternal stress and fetal sex. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2018;141(5):1880-86. [CrossRef]

- Xing Z, Yang T, Shi S, et al. Ambient particulate matter associates with asthma in high altitude region: A population-based study. World Allergy Organization Journal 2023;16(5):100774.

- Chiu YM, Carroll KN, Coull BA, Kannan S, Wilson A, Wright RJ. Prenatal Fine Particulate Matter, Maternal Micronutrient Antioxidant Intake, and Early Childhood Repeated Wheeze: Effect Modification by Race/Ethnicity and Sex. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Chen T, Shi S, Li X, et al. Improved ambient air quality is associated with decreased prevalence of childhood asthma and infancy shortly after weaning is a sensitive exposure window. Allergy 2023. [CrossRef]

- Anenberg SC, Mohegh A, Goldberg DL, et al. Long-term trends in urban NO(2) concentrations and associated paediatric asthma incidence: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6(1):e49-e58. [CrossRef]

- Braggio JT, Hall ES, Weber SA, Huff AK. Contribution of Satellite-Derived Aerosol Optical Depth PM(2.5) Bayesian Concentration Surfaces to Respiratory-Cardiovascular Chronic Disease Hospitalizations in Baltimore, Maryland. Atmosphere (Basel) 2020;11(2):209. [CrossRef]

- Boll LM, Khamirchi R, Alonso L, et al. Prenatal greenspace exposure and cord blood cortisol levels: A cross-sectional study in a middle-income country. Environment international 2020;144:106047. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim MF, Hod R, Nawi AM, Sahani M. Association between ambient air pollution and childhood respiratory diseases in low- and middle-income Asian countries: A systematic review. Atmospheric Environment 2021;256:118422.

- Soto-Martínez ME, Soto-Quiros ME, Custovic A. Childhood Asthma: Low and Middle-Income Countries Perspective. Acta Med Acad 2020;49(2):181-90. [CrossRef]

- Weber SA, Insaf TZ, Hall ES, Talbot TO, Huff AK. Assessing the impact of fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) on respiratory-cardiovascular chronic diseases in the New York City Metropolitan area using Hierarchical Bayesian Model estimates. Environ Res 2016;151:399-409. [CrossRef]

- Kloog I, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, Lee HJ, Schwartz J. Assessing temporally and spatially resolved PM2.5 exposures for epidemiological studies using satellite aerosol optical depth measurements. Atmospheric Environment 2011;45(35):6267-75.

- To T, Zhu J, Stieb D, et al. Early life exposure to air pollution and incidence of childhood asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema. Eur Respir J 2020;55(2). [CrossRef]

- PE, Qian ZM, McMillin SE, et al. Relationships between Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Allergic Rhinitis and Bronchitic Symptoms in Chinese Children. Toxics 2021;9(9). [CrossRef]

- Rice MB, Ljungman PL, Wilker EH, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic emissions and fine particulate matter and lung function decline in the Framingham heart study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2015;191(6):656-64. [CrossRef]

- Last, J. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Khalili R, Bartell SM, Hu X, et al. Early-life exposure to PM(2.5) and risk of acute asthma clinical encounters among children in Massachusetts: a case-crossover analysis. Environmental health : a global access science source 2018;17(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Jung CR, Chen WT, Tang YH, Hwang BF. Fine particulate matter exposure during pregnancy and infancy and incident asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2019;143(6):2254-62.e5. [CrossRef]

- Rivera Rivera NY, Tamayo-Ortiz M, Mercado García A, et al. Prenatal and early life exposure to particulate matter, environmental tobacco smoke and respiratory symptoms in Mexican children. Environ Res 2021;192:110365. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Yin Z, P, et al. Early-life exposure to PM(2.5) constituents and childhood asthma and wheezing: Findings from China, Children, Homes, Health study. Environment international 2022;165:107297. [CrossRef]

- Knibbs LD, Cortés de Waterman AM, Toelle BG, et al. The Australian Child Health and Air Pollution Study (ACHAPS): A national population-based cross-sectional study of long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution, asthma, and lung function. Environment international 2018;120:394-403. [CrossRef]

- Chau K, Franklin M, Gauderman WJ. Satellite-derived PM2. 5 composition and its differential effect on children’s lung function. Remote Sensing 2020;12(6):1028.

- Guo C, Hoek G, Chang L-y, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and lung function in children, adolescents, and young adults: a longitudinal cohort study. Environmental health perspectives 2019;127(12):127008.

- Fuertes E, Markevych I, Thomas R, et al. Residential greenspace and lung function up to 24 years of age: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Environment international 2020;140:105749. [CrossRef]

- Rosa MJ, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Alcala C, et al. Associations between early-life exposure to PM(2.5) and reductions in childhood lung function in two North American longitudinal pregnancy cohort studies. Environ Epidemiol 2023;7(1):e234. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Li S, Fan C, Bai Z, Yang K. The impact of PM2.5 on asthma emergency department visits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental science and pollution research international 2016;23(1):843-50. [CrossRef]

- Zheng XY, Ding H, Jiang LN, et al. Association between Air Pollutants and Asthma Emergency Room Visits and Hospital Admissions in Time Series Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10(9):e0138146. [CrossRef]

- Foppiano F, Schaub B. Childhood asthma phenotypes and endotypes: a glance into the mosaic. Mol Cell Pediatr 2023;10(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Freitas PD, Xavier RF, McDonald VM, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes based on extrapulmonary treatable traits. Eur Respir J 2021;57(1). [CrossRef]

- Pijnenburg MW, Frey U, De Jongste JC, Saglani S. Childhood asthma: pathogenesis and phenotypes. Eur Respir J 2022;59(6). [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin RF, McDonald VM. The Management of Extrapulmonary Comorbidities and Treatable Traits; Obesity, Physical Inactivity, Anxiety, and Depression, in Adults With Asthma. Front Allergy 2021;2:735030. [CrossRef]

- Pavord ID, Barnes PJ, Lemière C, Gibson PG. Diagnosis and Assessment of the Asthmas. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023;11(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Ho YN, Cheng FJ, Tsai MT, Tsai CM, Chuang PC, Cheng CY. Fine particulate matter constituents associated with emergency room visits for pediatric asthma: a time-stratified case-crossover study in an urban area. BMC public health 2021;21(1):1593. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Guo Y, Cai M, et al. Constituents of fine particulate matter and asthma in 6 low- and middle-income countries. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2022;150(1):214-22.e5. [CrossRef]

- Chen E, Miller GE, Shalowitz MU, et al. Difficult Family Relationships, Residential Greenspace, and Childhood Asthma. Pediatrics 2017;139(4). [CrossRef]

- Lipner EM, O'Dell K, Brey SJ, et al. The Associations Between Clinical Respiratory Outcomes and Ambient Wildfire Smoke Exposure Among Pediatric Asthma Patients at National Jewish Health, 2012-Geohealth 2019;3(6):146-59. [CrossRef]

- Exley D, Norman A, Hyland M. Adverse childhood experience and asthma onset: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24(136):299-305. [CrossRef]

- Rosa MJ, Lee AG, Wright RJ. Evidence establishing a link between prenatal and early-life stress and asthma development. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;18(2):148-58. [CrossRef]

- Shankardass K, McConnell R, Jerrett M, Milam J, Richardson J, Berhane K. Parental stress increases the effect of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma incidence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2009;106(30):12406-11. [CrossRef]

- Hahn J, Gold DR, Coull BA, et al. Air pollution, neonatal immune responses, and potential joint effects of maternal depression. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021;18(10):5062.

- Sheffield PE, Speranza R, Chiu YM, et al. Association between particulate air pollution exposure during pregnancy and postpartum maternal psychological functioning. PLoS One 2018;13(4):e0195267. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W, Zhao Y, Wang P, et al. PM2.5 exposure associated with prenatal anxiety and depression in pregnant women. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2022;248:114284.

- Braggio, J. Inflammation Describes and Explains the Adverse Effects of Aerosol Optical Depth-Particulate Matter on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Literature Review Since Medical Research Archives 2023;11(8). [CrossRef]

- Paciência I, Cavaleiro Rufo J, Moreira A. Environmental inequality: Air pollution and asthma in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2022;33(6). [CrossRef]

- NIH. PubMed. Secondary PubMed 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/.

- Google. Scholar. Secondary Scholar 2024. https://scholar.google.com/intl/en-US/scholar/about.html.

- NASA. Earth Orbiting System (EOS). Secondary Earth Orbiting System (EOS) 2024. https://eospso.nasa.gov/mission-category/3.

- Dadvand P, Villanueva CM, Font-Ribera L, et al. Risks and benefits of green spaces for children: a cross-sectional study of associations with sedentary behavior, obesity, asthma, and allergy. Environmental health perspectives 2014;122(12):1329-35. [CrossRef]

- Elliott CT, Henderson SB, Wan V. Time series analysis of fine particulate matter and asthma reliever dispensations in populations affected by forest fires. Environmental health : a global access science source 2013;12:11. [CrossRef]

- Magzamen S, Gan RW, Liu J, et al. Differential Cardiopulmonary Health Impacts of Local and Long-Range Transport of Wildfire Smoke. Geohealth 2021;5(3):e2020GH000330. [CrossRef]

- Delfino RJ, Brummel S, Wu J, et al. The relationship of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions to the southern California wildfires of 2003. Occup Environ Med 2009;66(3):189-97. [CrossRef]

- Gan RW, Ford B, Lassman W, et al. Comparison of wildfire smoke estimation methods and associations with cardiopulmonary-related hospital admissions. Geohealth 2017;1(3):122-36. [CrossRef]

- Hahn MB, Kuiper G, O'Dell K, Fischer EV, Magzamen S. Wildfire Smoke Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Cardiorespiratory Emergency Department Visits in Alaska. Geohealth 2021;5(5):e2020GH000349. [CrossRef]

- Pennington AF, Vaidyanathan A, Ahmed FS, et al. Large-scale agricultural burning and cardiorespiratory emergency department visits in the U.S. state of Kansas. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stowell JD, Geng G, Saikawa E, et al. Associations of wildfire smoke PM(2.5) exposure with cardiorespiratory events in Colorado 2011-2014. Environment international 2019;133(Pt A):105151. [CrossRef]

- Gan RW, Liu J, Ford B, et al. The association between wildfire smoke exposure and asthma-specific medical care utilization in Oregon during the 2013 wildfire season. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2020;30(4):618-28. [CrossRef]

- Rappold AG, Stone SL, Cascio WE, et al. Peat bog wildfire smoke exposure in rural North Carolina is associated with cardiopulmonary emergency department visits assessed through syndromic surveillance. Environmental health perspectives 2011;119(10):1415-20. [CrossRef]

- NASA. MODIS Vegetation Index Products (NDVI and EVI). Secondary MODIS Vegetation Index Products (NDVI and EVI) 2024. https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/dataprod/mod13.php.

- NASA. MODIS Thermal Anomalies/Fire. Secondary MODIS Thermal Anomalies/Fire 2024. https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/dataprod/mod14.php.

- SAS. SAS Studio 3.8: User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2018.

- SAS. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide, Seventh Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2017.

- SAS. SAS/STAT 15.3 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2023.

- Andrusaityte S, Grazuleviciene R, Kudzyte J, Bernotiene A, Dedele A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Associations between neighbourhood greenness and asthma in preschool children in Kaunas, Lithuania: a case-control study. BMJ Open 2016;6(4):e010341. [CrossRef]

- Cilluffo G, Ferrante G, Fasola S, et al. Association between asthma control and exposure to greenness and other outdoor and indoor environmental factors: a longitudinal study on a cohort of asthmatic children. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022;19(1):512.

- De Roos AJ, Kenyon CC, Yen YT, et al. Does Living near Trees and Other Vegetation Affect the Contemporaneous Odds of Asthma Exacerbation among Pediatric Asthma Patients? J Urban Health 2022;99(3):533-48. [CrossRef]

- Eldeirawi K, Kunzweiler C, Zenk S, et al. Associations of urban greenness with asthma and respiratory symptoms in Mexican American children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019;122(3):289-95. [CrossRef]

- Hartley K, Ryan PH, Gillespie GL, et al. Residential greenness, asthma, and lung function among children at high risk of allergic sensitization: a prospective cohort study. Environmental Health 2022;21(1):1-11.

- Hu Y, Chen Y, Liu S, et al. Higher greenspace exposure is associated with a decreased risk of childhood asthma in Shanghai - A megacity in China. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2023;256:114868. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Chen Y, Liu S, et al. Residential greenspace and childhood asthma: An intra-city study. The Science of the total environment 2023;857(Pt 3):159792. [CrossRef]

- Ihlebæk C, Aamodt G, Aradi R, Claussen B, Thorén KH. Association between urban green space and self-reported lifestyle-related disorders in Oslo, Norway. Scand J Public Health 2018;46(6):589-96. [CrossRef]

- Squillacioti G, Bellisario V, Levra S, Piccioni P, Bono R. Greenness Availability and Respiratory Health in a Population of Urbanised Children in North-Western Italy. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Thien F, Beggs PJ, Csutoros D, et al. The Melbourne epidemic thunderstorm asthma event 2016: an investigation of environmental triggers, effect on health services, and patient risk factors. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2(6):e255-e63. [CrossRef]

- Tischer C, Gascon M, Fernández-Somoano A, et al. Urban green and grey space in relation to respiratory health in children. Eur Respir J 2017;49(6). [CrossRef]

- Alcala CS, Orozco Scott P, Tamayo-Ortiz M, et al. Longitudinal assessment of maternal depression and early childhood asthma and wheeze: Effect modification by child sex. Pediatric Pulmonology 2023;58(1):98-106.

- Castillo MD, Kinney PL, Southerland V, et al. Estimating Intra-Urban Inequities in PM(2.5)-Attributable Health Impacts: A Case Study for Washington, DC. Geohealth 2021;5(11):e2021GH000431. [CrossRef]

- Chang HH, Pan A, Lary DJ, et al. Time-series analysis of satellite-derived fine particulate matter pollution and asthma morbidity in Jackson, MS. Environ Monit Assess 2019;191(Suppl 2):280. [CrossRef]

- Davila Cordova JE, Tapia Aguirre V, Vasquez Apestegui V, et al. Association of PM(2.5) concentration with health center outpatient visits for respiratory diseases of children under 5 years old in Lima, Peru. Environmental health : a global access science source 2020;19(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Fasola S, Maio S, Baldacci S, et al. Effects of particulate matter on the incidence of respiratory diseases in the pisan longitudinal study. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020;17(7):2540.

- Lai VWY, Bowatte G, Knibbs LD, et al. Residential NO(2) exposure is associated with urgent healthcare use in a thunderstorm asthma cohort. Asia Pac Allergy 2018;8(4):e33. [CrossRef]

- Lavigne É, Talarico R, van Donkelaar A, et al. Fine particulate matter concentration and composition and the incidence of childhood asthma. Environment international 2021;152:106486. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wei J, Hu Y, et al. Long-term effect of intermediate particulate matter (PM(1)(-)(2.5)) on incident asthma among middle-aged and elderly adults: A national population-based longitudinal study. The Science of the total environment 2023;859(Pt 1):160204. [CrossRef]

- Lin YT, Shih H, Jung CR, et al. Effect of exposure to fine particulate matter during pregnancy and infancy on paediatric allergic rhinitis. Thorax 2021;76(6):568-74. [CrossRef]

- Maio S, Fasola S, Marcon A, et al. Relationship of long-term air pollution exposure with asthma and rhinitis in Italy: an innovative multipollutant approach. Environmental Research 2023;224:115455.

- Renzi M, Scortichini M, Forastiere F, et al. A nationwide study of air pollution from particulate matter and daily hospitalizations for respiratory diseases in Italy. The Science of the total environment 2022;807(Pt 3):151034. [CrossRef]

- Schreibman A, Xie S, Hubbard RA, Himes BE. Linking Ambient NO2 Pollution Measures with Electronic Health Record Data to Study Asthma Exacerbations. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2023;2023:467-76 [published Online First: 20230616].

- Strickland MJ, Hao H, Hu X, Chang HH, Darrow LA, Liu Y. Pediatric Emergency Visits and Short-Term Changes in PM2.5 Concentrations in the U.S. State of Georgia. Environmental health perspectives 2016;124(5):690-6. [CrossRef]

- Tétreault LF, Doucet M, Gamache P, et al. Severe and Moderate Asthma Exacerbations in Asthmatic Children and Exposure to Ambient Air Pollutants. International journal of environmental research and public health 2016;13(8). [CrossRef]

- Tétreault LF, Doucet M, Gamache P, et al. Childhood Exposure to Ambient Air Pollutants and the Onset of Asthma: An Administrative Cohort Study in Québec. Environmental health perspectives 2016;124(8):1276-82. [CrossRef]

- To T, Zhu J, Villeneuve PJ, et al. Chronic disease prevalence in women and air pollution--A 30-year longitudinal cohort study. Environment international 2015;80:26-32. [CrossRef]

- Vu BN, Tapia V, Ebelt S, Gonzales GF, Liu Y, Steenland K. The association between asthma emergency department visits and satellite-derived PM(2.5) in Lima, Peru. Environ Res 2021;199:111226. [CrossRef]

- Yan M, Ge H, Zhang L, et al. Long-term PM(2.5) exposure in association with chronic respiratory diseases morbidity: A cohort study in Northern China. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2022;244:114025. [CrossRef]

- Hein L, Spadaro JV, Ostro B, et al. The health impacts of Indonesian peatland fires. Environmental health : a global access science source 2022;21(1):62. [CrossRef]

- EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). NAAQS (National Ambient Air Quality Standards) Table. Secondary NAAQS (National Ambient Air Quality Standards) Table 2024. https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants/naaqs-table.

- Wang J, Chen G, Hou J, et al. Associations of residential greenness, ambient air pollution, biological sex, and glucocorticoids levels in rural China. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2022;242:113945.

- Dreher, ML. Whole Fruits and Fruit Fiber Emerging Health Effects. Nutrients 2018;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Michaeloudes C, Abubakar-Waziri H, Lakhdar R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress in asthma. Mol Aspects Med 2022;85:101026. [CrossRef]

| VARIABLES1 | STUDIES2 | SPECIFIC OUTCOMES3 |

ECOLOGIC SETTING | ||

| Greenness | Air Pollution |

Wildfires | |||

| Participants | 2,821,393 | 13,725,971 | 46,089 | 13,237,790 | 442,092 |

| Studiesd,d,b | 61 | 61 | 13 (21.3) | 37 (60.7) | 11 (18.0) |

| Specific Outcomesd,d,b | 61 | 198 | 41 (20.7) | 125 (63.1) | 32 (16.2) |

| Publication Yearb,b,c | |||||

| 2009-2016 | 13 (21.3) | 31 (15.7) | 3 (1.5) | 21 (10.6) | 7 (3.5) |

| 2017-2023 | 48 (78.7) | 167 (84.3) | 38 (19.2) | 104 (52.5) | 25 (12.6) |

| Countryb,b,b | |||||

| 2+ Countries | 3 (4.9) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Australia | 3 (4.9) | 12 (6.1) | 1 (0.5) | 11 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Canada | 6 (9.8) | 21 (10.6) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (10.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| China | 8 (13.1) | 29 (14.6) | 2 (1.0) | 27 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Indonesia | 1 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Italy | 5 (8.2) | 49 (24.8) | 15 (7.6) | 34 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lithuania | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mexico | 3 (4.9) | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Norway | 1 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Peru | 2 (3.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Spain | 2 (3.3) | 6 (3.0) | 6 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Taiwan | 2 (3.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| United States | 24 (39.3) | 63 (31.8) | 14 (7.1) | 20 (10.1) | 29 (14.6) |

| Study Designb,b b | |||||

| Case Control | 11 (18.0) | 28 (14.1) | 4 (2.0) | 7 (3.5) | 17 (8.6) |

| Cross Sectional | 23 (37.7) | 100 (50.5) | 24 (12.1) | 64 (32.3) | 12 (6.1) |

| Panel | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prospective Cohort | 11 (18.0) | 37 (18.7) | 13 (6.6) | 24 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Retrospective Cohort | 9 (14.8) | 21 (10.6) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (10.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Time Series | 6 (9.8) | 11 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| Surveillanceb,b,b | |||||

| Incidence | 18 (29.5) | 53 (26.8) | 9 (4.6) | 44 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prevalence | 43 (70.5) | 144 (72.7) | 31 (15.7) | 81 (40.9) | 32 (16.2) |

| Other | . | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ICD-CMb,b,b | |||||

| 9 | 21 (34.4) | 51 (25.8) | 10 (5.1) | 22 (11.1) | 19 (9.6) |

| 10 | 10 (16.4) | 27 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (10.6) | 6 (3.0) |

| Other | 30 (49.2) | 120 (60.6) | 31 (15.7) | 82 (41.4) | 7 (3.5) |

| Questionnaire Dxb,b,b | |||||

| No | 34 (55.7) | 97 (49.0) | 20 (10.1) | 46 (23.2) | 31 (15.7) |

| Yes | 26 (42.6) | 100 (50.5) | 21 (10.6) | 78 (39.4) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Medical Dxb,b,b | |||||

| No | 27 (44.3) | 106 (53.5) | 31 (15.7) | 68 (34.3) | 7 (3.5) |

| Yes | 31 (50.8) | 78 (39.4) | 10 (5.1) | 43 (21.7) | 25 (12.6) |

| Other | 3 (4.9) | 14 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Health Outcome b,b,c | |||||

| Asthma | 54 (88.5) | 124 (62.6) | 31 (15.7) | 75 (37.9) | 18 (9.1) |

| Other Respiration | 7 (11.5) | 74 (37.4) | 10 (5.1) | 50 (25.2) | 14 (7.1) |

| Specific Outcomeb,b,b | |||||

| Allergic Rhinitis | 2 (3.3) | 15 (7.6) | 2 (1.0) | 13 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asthma | 46 (75.4) | 69 (34.8) | 11 (5.6) | 46 (23.2) | 12 (6.1) |

| Asthma Attacks | 4 (6.6) | 14 (7.1) | 4 (2.0) | 9 (4.6) | 1 (0.5) |

| Bronchitis | . | 10 (5.1) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (3.0) |

| Cough | . | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Eczema | . | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEF25% | . | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEF25%-75% | . | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEF50% | . | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEF75% | . | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| FeNO | . | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEV1 | 2 (3.3) | 8 (4.0) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| FEV1/FVC | . | 8 (4.0) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| FVC | . | 8 (4.0) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | . | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Phlegm | . | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Psychologic | 1 (1.6) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Rescue Medication | 1 (1.6) | 11 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.6) | 2 (1.0) |

| Respiration | . | 11 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4.0) |

| Wheeze | 5 (8.2) | 16 (8.1) | 3 (1.5) | 13 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Preexposure Studiesb,b,b | |||||

| No | 52 (85.2) | 183 (92.4) | 41 (20.7) | 110 (55.6) | 32 (16.2) |

| Yes | 9 (14.8) | 15 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lung Studiesb,b,b | |||||

| No | 59 (96.7) | 165 (83.3) | 28 (14.1) | 108 (54.6) | 29 (14.6) |

| Yes | 2 (3.3) | 33 (16.7) | 13 (6.6) | 17 (8.6) | 3 (1.5) |

| Psychologic Studiesb,b,c | |||||

| No | 57 (93.4) | 191 (96.5) | 38 (19.2) | 121 (61.1) | 32 (16.2) |

| Yes | 4 (6.6) | 7 (3.5) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Monitorsb, b, b | |||||

| No | 12 (19.7) | 43 (21.7) | 40 (20.2) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Yes | 49 (80.3) | 155 (78.3) | 1 (0.5) | 122 (61.6) | 32 (16.2) |

| AODd,b,b | |||||

| No | . | 23 (11.6) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (11.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Yes | 61 (100.0) | 175 (88.4) | 41 (20.7) | 102 (51.5) | 32 (16.2) |

| AODVALb,b,b | |||||

| No AOD | . | 23 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 13 (28.9) | 22 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (10.2) | 7 (4.8) |

| Yes | 29 (64.4) | 93 (63.3) | 1 (0.7) | 84 (57.1) | 8 (5.4) |

| Other | 3 (6.7) | 9 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (6.1) |

| AOD-Air Pollution | |||||

| NO2 | 7.4 | 10.4 | . | 10.4 | . |

| O3 | 89.2 | 89.2 | . | 89.2 | . |

| PM1 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | . | . |

| PM1-2.5 | 16.6 | 16.6 | . | 16.6 | . |

| PM2.5 | 23.6 | 25.6 | . | 23.5 | 34.0 |

| PM2.5-10 | . | 51.7 | . | 51.7 | . |

| PM10 | 30.1 | 48.7 | . | 48.7 | . |

| Variables | SIGNIFICANT OUTCOME GROUP1 | COMMENTS | ||

| NS | SL | SH | ||

| Respiration Groupc | Respiration group was not significant. | |||

| Asthma | 39 (19.7) | 18 (9.1) | 67 (33.8) | |

| Other Respiration | 31 (15.7) | 9 (4.6) | 34 (17.2) | |

| Ecologic Settingb | Ecologic setting was significant, with more greenness specific outcomes (n=18) in the SL group. | |||

| Greenness | 15 (7.6) | 18 (9.1) | 8 (4.0) | |

| Air Pollution | 45 (22.7) | 8 (4.0) | 72 (36.4) | |

| Wildfire | 10 (5.1) | 1 (0.5) | 21 (10.6) | |

| Publication Yearc | Publication year was not significant. | |||

| 2009-2016 | 12 (6.1) | 2 (1.0) | 17 (8.6) | |

| 2017-2023 | 58 (29.3) | 25 (12.6) | 84 (42.2) | |

| Countryb | Country was significant. Studies completed in Italy and in the United States had the highest number of SL specific outcomes, 21 (10.6%) each; this total was higher than the total for other countries. In descending order of total specific outcomes, the United States (n=33, 16.7%) had the most, Italy (n=19, 9.6%) was second, and China (n=16, 8.1%) third. | |||

| 2+ Countries | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Australia | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.5) | |

| Canada | 7 (3.5) | 2 (1.0) | 7 (3.5) | |

| China | 8 (4.0) | 5 (2.5) | 16 (8.1) | |

| Indonesia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Italy | 21 (10.6) | 9 (4.6) | 19 (9.6) | |

| Lithuania | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Mexico | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | |

| Norway | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Peru | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Spain | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Tiwan | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| United States | 21 (10.6) | 9 (4.6) | 33 (16.7) | |

| PM25GRP3b | PM25GP3 was significant, with 15 specific outcomes in the higher category of both predictors. | |||

| Lower | 13 (17.6) | 5 (6.8) | 27 (36.5) | |

| Within | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Higher | 5 (6.8) | 4 (5.4) | 15 (20.3) | |

| Ageb | Age (yes) risk factor was significant, with most (n=22) in the SH group. | |||

| No | 67 (33.8) | 22 (11.1) | 79 (39.9) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.5) | 22 (11.1) | |

| Education/Incomec | Education/income risk factor was not significant. | |||

| No | 70 (35.4) | 26 (13.1) | 98 (49.5) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | |

| Ethnicity/Racea | Ethnicity/race (yes) risk factor was significant. | |||

| No | 68 (34.3) | 25 (12.6) | 95 (48.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (3.0) | |

| Environmentalb | Environmental risk factor was significant, with 98 specific outcomes in the SH group. | |||

| No | 58 (29.3) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | |

| Yes | 12 (6.1) | 24 (12.1) | 98 (49.5) | |

| Genderb | Gender risk factor was significant, with 22 specific outcomes in the SH group. | |||

| No | 68 (34.3) | 22 (11.1) | 79 (39.9) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.5) | 22 (11.1) | |

| Geographica | Geographic risk factor was significant, with 11 specific outcomes in the SH group. | |||

| No | 69 (34.8) | 23 (11.6) | 90 (45.4) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 11 (5.6) | |

| Psychologicb | Psychologic risk factor was significant, with 5 specific outcomes in the SH group. | |||

| No | 70 (35.4) | 23 (11.6) | 96 (48.5) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Otherb | Other risk factor was significant, with 14 specific outcomes in the SH group. | |||

| No | 67 (33.8) | 20 (10.1) | 87 (43.9) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.5) | 14 (7.1) | |

| Single Mechanismsb | Single physiologic mechanisms variable was significant, with more IN and OT mentions in the SH group, and more IM and OS mentions in the SL group. | |||

| IM | 6 (5.4) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | |

| IN | 6 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (16.4) | |

| OS | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.8) | |

| OT | 28 (25.4) | 9 (8.2) | 33 (30.0) | |

| Multiple Mechanismsb | Multiple physiologic mechanisms variable was also significant, with most mentions in the SH group. | |||

| IMIN | 6 (6.8) | 5 (5.7) | 13 (14.8) | |

| INOS | 6 (6.8) | 3 (3.4) | 8 (9.1) | |

| IMINOS | 16 (18.2) | 5 (5.7) | 26 (29.6) | |

| Risk factors1 | Health outcome | Ecologic setting | Health outcome by Ecologic setting interaction | ||||||||

| Asthma | Respiration | Greenness | Air Pollution | Wildfire | Asthma- Greenness | Asthma- Air Pollution |

Asthma- Wildfire | Respiration-Greenness | Respiration- Air Pollution |

Respiration-Wildfire | |

| Ageb,b,a | 0.38a | 0.19a | 0.06a | 0.08b | 0.72ab | 0.13a | 0.08b | 0.94ab | 0.00c | 0.08d | 0.50bcd |

| Education/ Incomec,c,c |

0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ethnicity/Racec,c,c | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Environmentala,c,c | 1.06a | 0.65a | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.11 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.64 |

| Genderc,b,c | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.06a | 0.10b | 0.68ab | 0.13a | 0.09b | 0.78abc | 0.00cd | 0.10ce | 0.57abde |

| Geographicc,c,c | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Psychologicc,c,c | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.19a | 0.03a | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Othera,a,b | 0.19a | 0.04a | 0.24a | 0.11 | 0.00a | 0.48a | 0.09a | 0.00a | 0.00a | 0.12a | 0.00a |

| Totalb,b,c | 2.24a | 1.25a | 1.36a | 1.38b | 2.49ab | 2.13 | 1.55a | 3.06ab | 0.60b | 1.22b | 1.93 |

| PHYSIOLOGIC MECHANISMS1 | Health outcome | Ecologic setting | Health outcome by Ecologic setting interaction | ||||||||

| Asthma | Respiration | Greenness | Air Pollution | Wildfire | Asthma-Greenness | Asthma-Air Pollution | Asthma-Wildfire | Respiration-Greenness | Respiration-Air Pollution | Respiration-Wildfire | |

| Individualc,b c | 1.46 | 1.72 | 1.43a | 1.85a | 1.50 | 1.36a | 1.76 | 1.28b | 1.50 | 1.94ab | 1.71 |

| Totalc,a,c | 1.79 | 2.22 | 1.85 | 2.37 | 1.79 | 1.71 | 2.21 | 1.44a | 2.00 | 2.52a | 2.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).