1. Introduction

Safety in the design of automotive structures is of utmost importance, especially in the design and manufacturing stages [

1]. Seat structures engineers have faced a wide range of challenges when considering manufacturing and cost savings, which has influenced the improvement of design techniques. A car seat should be designed for the comfort of the passenger and to protect them from situations involving safety issues. The seat structure requires a simple, lightweight design to minimize material and manufacturing process costs. Despite the importance of seating structure design, many organizations are lack of resources to perform in-depth optimization analyses of multiple scenarios [

1].

In the manufacturing processes of automotive seat structures, regulatory requirements must be met regarding the safety and quality of welding processes with metallic components or structural elements manufactured in production facilities. In this sense, [

2] describes the importance of standards such as ISO 3834-1 (Quality requirements for fusion welding of materials), in [

3]; ISO 14731 (Welding coordination. Tasks and responsibilities) in [

4]; and EN 1090-2 (Execution of steel and aluminum structures. Part 2: technical requirements for the execution of steel structures) in [

5], which include requirements for LBW processes.

LBW technology is increasingly being used in industrial applications not only for technical advantages in terms of material and product properties but also for benefits in terms of performance, production, and manufacturing capacity [

6]. The design and manufacturing of small parts take advantage of technical processing innovations and economies of scale; in this type of application, LBW plays an important role in quality and safety aspects. LBW is a high-energy density beam welding process that is considered an alternative to conventional arc welding methods [

7].

Among the advantages offered by this technology is the possibility of achieving welded joints at a high welding speed and with low heat input, which translates into high productivity, contributing to the process optimization and the reduction of manufacturing production costs [

8].

Due to increasingly stringent technical and government requirements, manufacturing companies in the automotive industry face upward challenges in achieving lightweight structures, as well as complying with legal regulations to fulfill customer requirements.

Therefore, adequate welding processes are required, as well as operating with optimal parameters that allow all specifications to be met. That at the same time satisfies the, quality, and productivity to maintain competitiveness in the market [

9].

Primarily, LBW takes advantage of three main factors: non-contact joining, single-sided joining technology, and a high-power beam capable of creating a welded joint in a fraction of a second [

10]. LBW is a welding technology very suitable for the manufacturing of automotive structures. The LBW process requires a laser optical device installed on a robot and a scanning mirror head as the final reflector. An LBW machine can easily produce welded joints at different locations on a product by simply repositioning the robot or redirecting the laser beam via remote instructions.

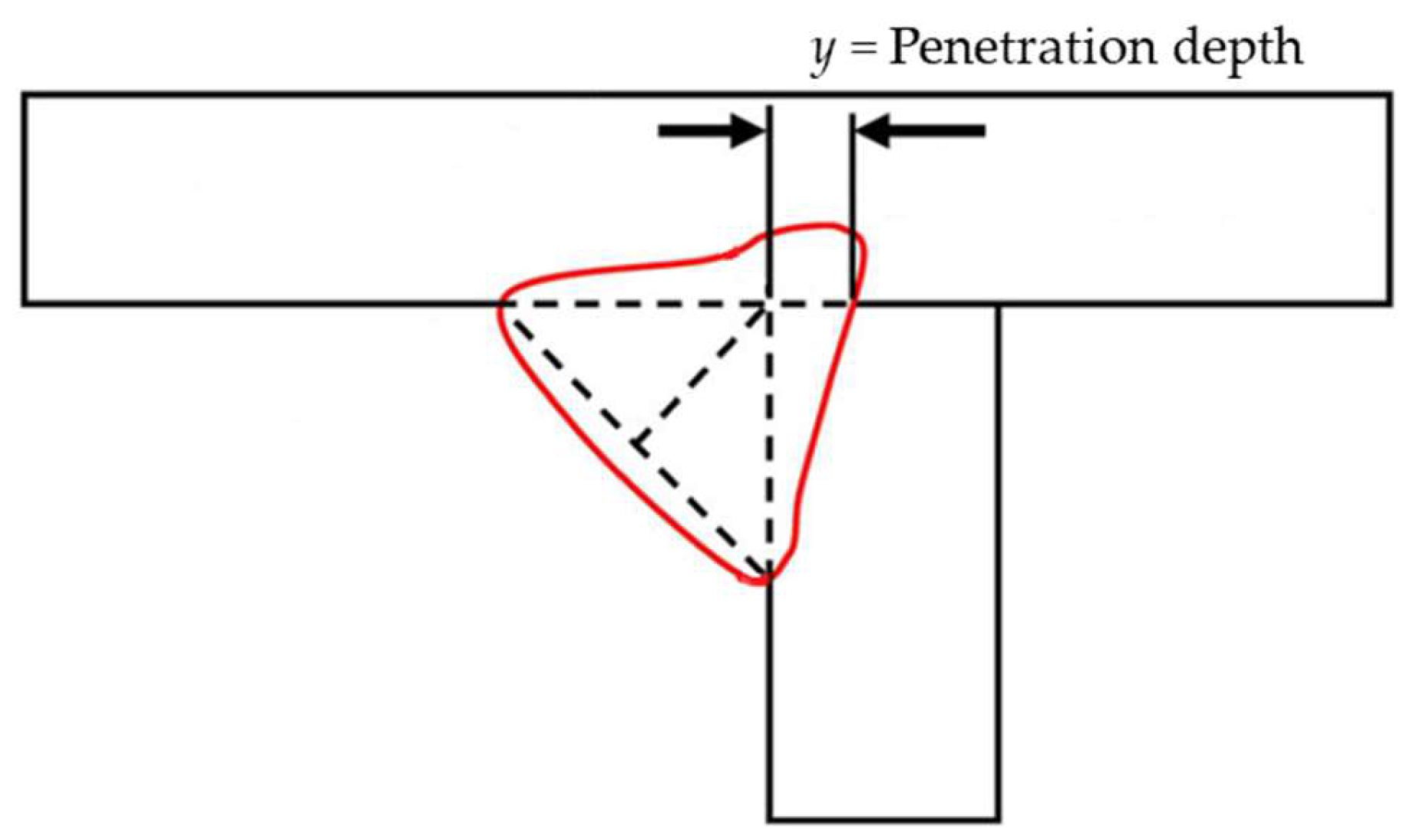

An important aspect of the manufacturing process of automotive seat structures is the weld penetration depth that must be obtained when welding certain joints. The laser energy required for penetration depth using an LBW machine is small, approximately 1 mm/kW. On the other hand, the laser power can be modified during the welding process for application in different geometries. Joints in laser welding applications are heat transfer or keyhole type; likewise, the shape of the molten material depends on the welding speed, laser power, and focal position [

11].

The choice to use keyhole-type laser welding occurs with power requirements greater than 106 W/cm

2 due to its greater metal vaporization. Intense vaporization distinguishes keyhole laser welding from other welding processes because it causes a significant increase in vapor pressure (back pressure), which creates a narrow cavity or keyhole in the molten material. The laser beam can then penetrate deep into the metal through the cavity, refracting and damping as it travels through the vapor. When the laser beam reaches the surface of the cavity, the beam energy is partially absorbed at the surface and partially reflected to a new interaction point, creating the joint [

12,

13]. In this sense, in [

14] a mathematical simulation approach of the temperature distribution and experimentation in the LBW is used to experimentally and numerically study the effect of each parameter.

An important aspect regarding welding manufacturing processes is the environmental impact, since, due to issues related to the design of the process, the equipment used and in general the manufacturing process itself, the raw materials used are not fully utilized [

15]. In addition, to the generation of gases polluting the environment, especially those processes with high energy content. As with all welding processes, destructive testing is required to ensure the quality and reliability of the welded joint. A destructive test consists of microscopic measurements of a cross-section of a sample (specimen), to evaluate the weld penetration depth and determine whether the lot is accepted or rejected. Since it is not feasible to test 100% of each batch, a probability to reject an entire batch exists.

For welding processes, small production batches minimize the probability cost of rejecting an entire batch of material if a problem is found, but the cost per inspection and lead time for machine release are affected. In contrast, increasing the material lot size minimizes inspection cost and maximizes machine utilization, since the machine cannot begin production until the quality of the welded joints is verified. However, when a problem, such as a lack of weld penetration depth is detected during material inspection, the entire batch must be rejected, making reliable and robust process capability imperative. Therefore, the concept of sustainability has received special attention and support, as it provides a more holistic approach to the development and evaluation of welding processes [

15].

In the literature, it is observed that interest has increased in how environmental improvements can be achieved through operational practices. In [

16] describes the relationship between lean and problem-solving practices with reducing the environmental impact of an organization. The green management approach contributes to cost reduction by using resources such as raw materials more efficiently, which also positively influences the organization’s results [

17].

Therefore, the main challenges for industrial organizations such as the automotive welding industry, in terms of sustainability and competitiveness, are linked to defect-free products, and fast, efficient, flexible, but also environmentally friendly manufacturing processes [

18].

Increased competition in many industries is accompanied by increasing cost pressure. This poses the frequent challenge of identifying and optimizing new and/or improved value-added processes [

19]. Process capability assessment can effectively address the statistical performance of the process with a dimensionless indicator. Potential process capability (C

p) and actual process capability (C

pk) are statistical measures that quantify process variation, equivalent to plus/minus three standard deviations (

σ) from the mean for comparison with the specification tolerance. (Customer requirements) [

20]. These indices are effective tools for both process capability analysis and quality assurance. Understanding process variation and evaluating process performance are essential tasks in quality improvement projects [

20].

As stated in [

20], the actual process capability index C

pk should be considered for the initial evaluation of critical customer characteristics to determine the capability of the process to meet those requirements. During the production process, statistical evaluation of process control is needed to monitor process stability and randomness of process behavior before evaluating process capability [

20]. It is necessary to meet assumptions of normality and stability before making inferences about the capacity of the process [

21,

25].

Capability analysis can help decision-makers better understand the process and thus achieve important quality improvements [

22]. From a quality perspective, the C

pk is expected to be greater than or equal to 1.33. Therefore, a C

pk less than 1.00 is evidence that the process cannot meet specifications [

21,

23,

25,

26].

Table 1 summarizes different approaches for similar performed weld penetration depth studies found in the literature using LBW technology, as well as the contribution of this proposal. These contributions range from destructive testing and theoretical-empirical analysis [

27], to artificial neural networks and finite element analysis [

4,

28]. In [

7,

29,

30,

31,

32], the Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology for analysis was applied.

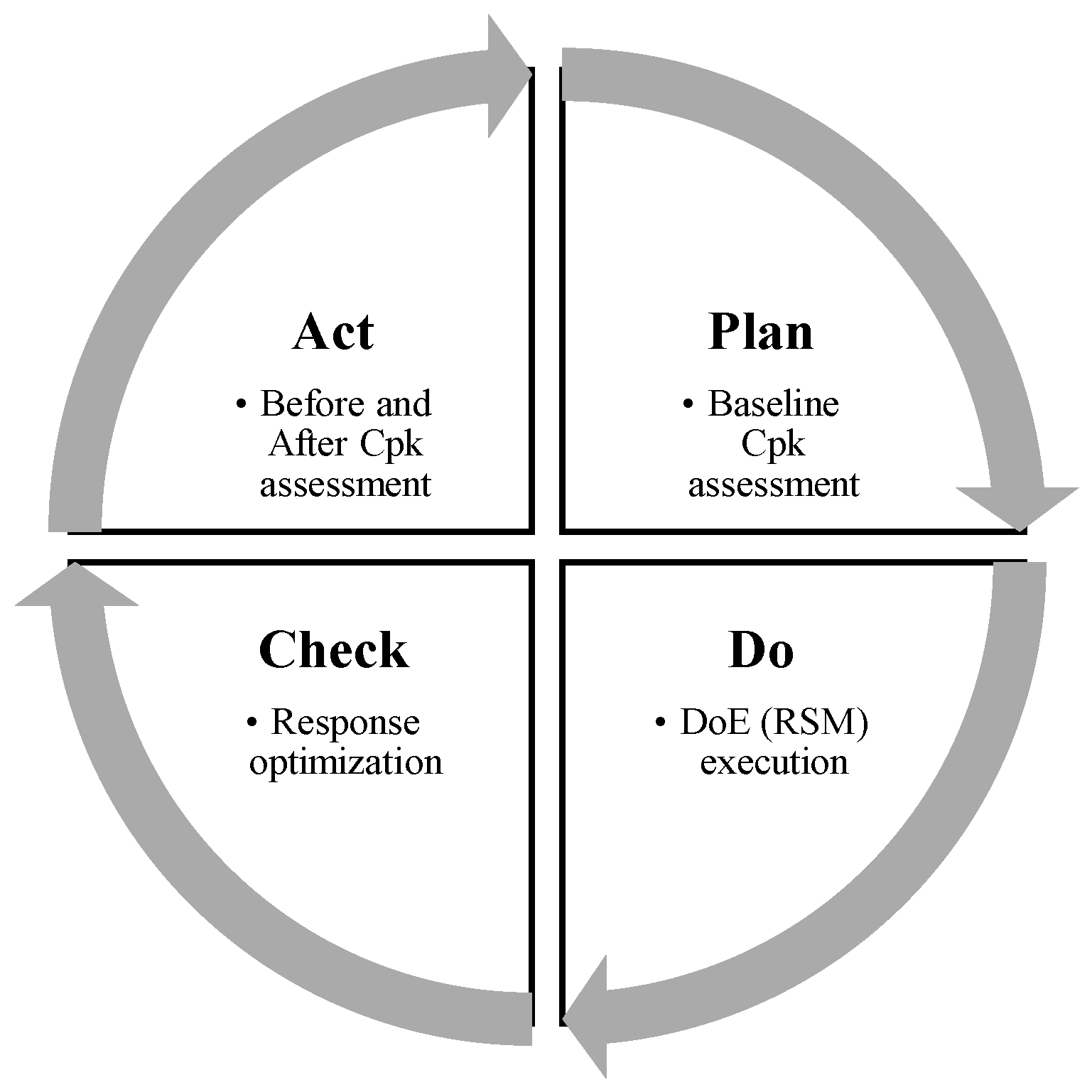

In this paper, the case of a low level of weld penetration depth is addressed, which must be greater than or equal to 1.2 mm for T-type joints between a side panel and the upper rail which are joined to integrate a car seat structure by fusion welding. Through the PDCA (plan-do-check-act) cycle methodology, an evaluation of the capability of the current process is carried out to determine the necessary improvements: change the mean, reduce the process variation, or do both [

21,

33]. Subsequently, the DoE Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is used as a tool to characterizes the factors that influence the output variable (y), to determine the optimal process parameters. Finally, a confirmation test of process capacity is conducted to validate and quantify the improvements achieved.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section II present the case of study, describes the PDCA cycle improvement model and the response surface model (RSM) approach. Section III presents the results of the case study. Section IV discussion about the optimized model. Finally, in section V the conclusions achieved in the long term are presented.

3. Results

Once the factors (A, B, and C) were coded, the orthogonal matrix was defined for a complete factorial design with three factors and two levels, that is, 2

3 DoE, giving eight possible combinations. Additionally, a treatment was added to evaluate the curvature with fixed values at the center point of the experimental window, as detailed in

Table 5. Three repetitions were performed for each treatment (experiment), giving a total of (27-1) degrees of freedom for the analysis.

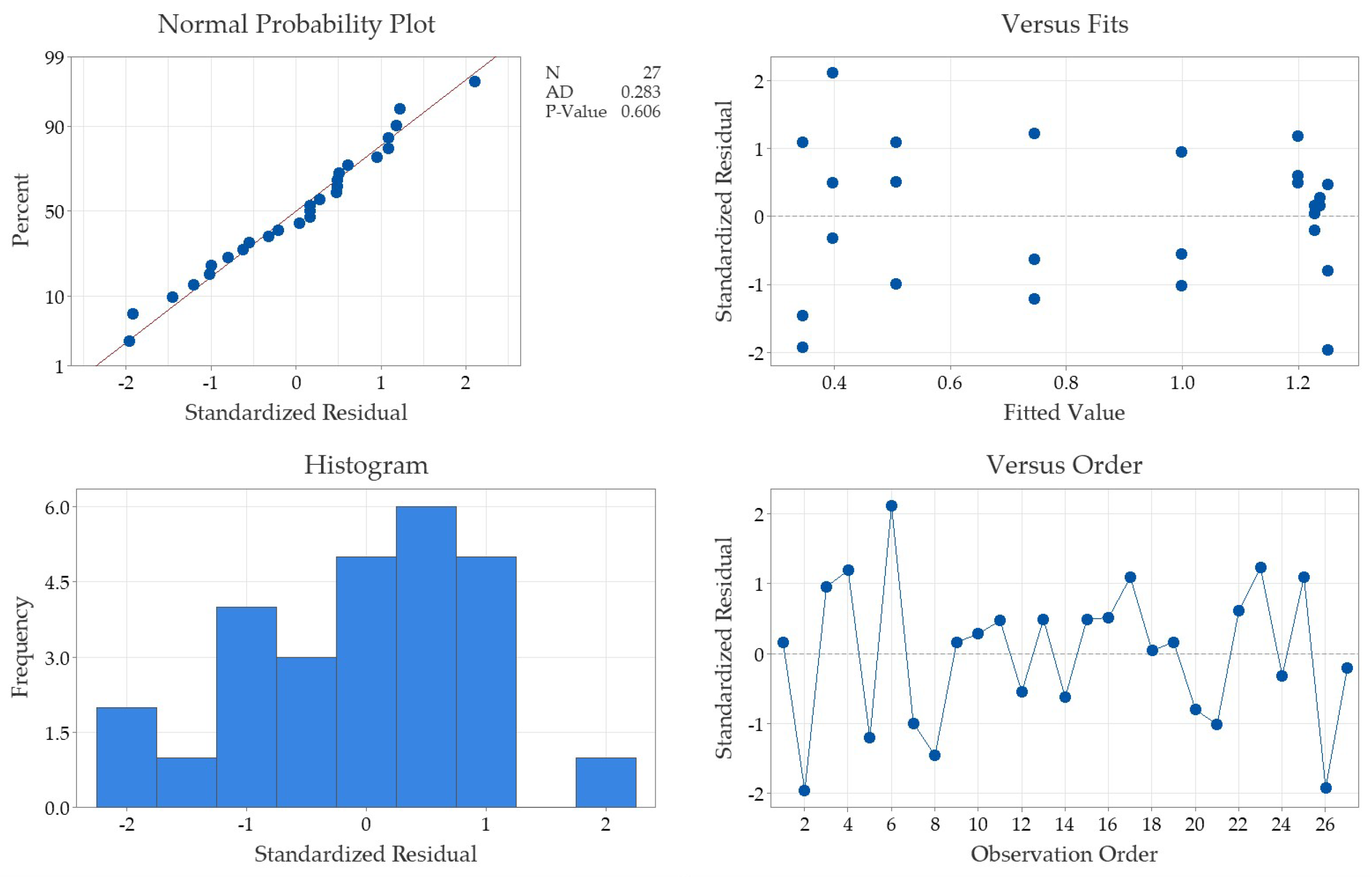

Table 6 describes the analysis of variance, (ANOVA). This estimation of effects, evaluates the significance of one or more factors by comparing the means of the response variable at different levels [

40] of the experiment using RSM for the assessment. A stepwise technique was applied, adding terms to make the model hierarchical [

39]; see

Table A1 of the

Appendix A for details. According to

Table 6, the model is statistically significant with a probability value (P-value) of 0.000; furthermore, the ANOVA table shows the significant quadratic effect for speed and double interactions, all with (P-values) less than 0.05. The lack of fit test was also satisfactory, with a (P-value) greater than 0.05; a residual analysis confirmed the model’s predictability with no multicollinearity issues. See

Figure A1 of the

Appendix B.

As shown in the ANOVA table, the linear effects of laser power and focal position affect welding penetration [

7,

27,

30,

31] in the automotive seat structure seam weld under study with a significance level of 0.05, so the null hypothesis is rejected [

39,

40]. With a total of 26 degrees of freedom, the model meets the sample size needed to perform an analysis of the quadratic effects and the double interaction effects from the DoE main factors, as summarized in the ANOVA table:

• Quadratic effect of Speed (AA),

• Double interactions of Speed-Power (AB) and Speed-Focal Position (AC)

Thanks to the stepwise technique, the remaining double interactions and non-significant quadratic effects are discarded with a confidence level of 95%.

Based on

Table 6, the calculated F-value, which indicates the magnitude of the effect, for the focal position is 271.29, which shows the most significant impact on weld penetration [

7], as shown in

Figure 5.

Table 7 shows the coefficients of the regression equation; variance inflation analysis (VIF) was also performed, with no collinearity problems observed, VIF = 1.00 [

39]. The coefficient of determination R-sq = 94.64% and R-sq

(pred) = 90.46% were obtained, indicating that the model is highly accurate for prediction. Furthermore, the laser speed coefficient has a (P-Value) of 0.087, which implies that this factor is not statistically significant at the 95.0% confidence level.

The regression equation obtained by the DoE stepwise experimentation technique using the RSM methodology is described as:

where

y represents the response variable.

4. Discussion

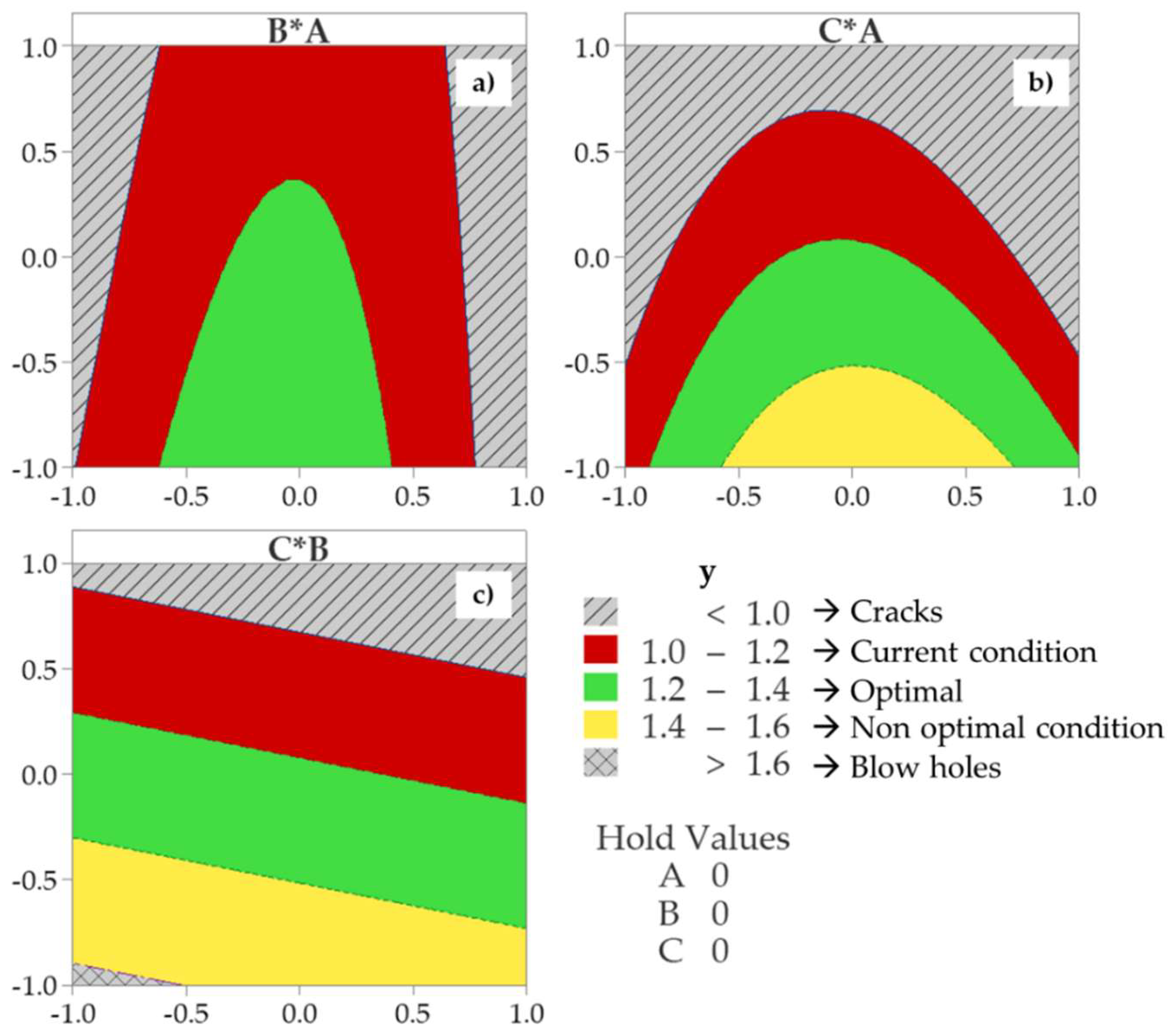

Figure 6 shows the graphic analysis of the behavior of the response variable (

y) using (2). The red outline indicates a weld penetration depth for

y < 1.20 mm. Areas with gray lines are below 1.00 mm, indicating "crack" regions; the light gray dashed area indicates a weld penetration depth greater than 1.60 mm, which causes a blow hole condition due to the material thickness of 1.60 mm; the yellow region is acceptable; and the green zone indicates an optimal and desirable region for weld penetration depth [

32].

Figure 6a shows the relationship between welding speed and laser power when the focal position is set to 224.15 mm;

Figure 6b shows the relationship between welding speed and focal position when the laser power is set to 2500 kW;

Figure 6c shows the relationship between focal position and laser power when the welding speed is set to 30 mm/s. The desirable zone for measurable weld penetration depth (

y), is between 1.20 and 1.40 mm, which is highlighted in green. The contour analysis allows the evaluation of different behavior of the response variable depending on how the process parameters are adjusted.

Figure 6a and 6b show a quadratic relationship between the adjustment factors and the depth of penetration of the weld, while

Figure 6c indicates a linear relationship between laser power and focal position versus weld penetration depth, justifying the use of RSM for the optimization of (

y) [

39].

After the first step in RSM, as shown in

Figure 6, the weld penetration depth is sought to be set to y ≈ 1.35 mm. To optimize the response variable,

Table 8 summarizes the proposed optimal process parameters. The welding speed was set to a nominal value of 30 mm/s, the laser power was set to a nominal value of 2500 kW, and the focal position was set to 224.02 mm to achieve the desirable weld penetration depth of 1.35 mm, which is optimal to avoid cracks or blow holes, as indicated in

Figure 6.

The RSM using the stepwise technique shows significant statistical evidence of the main contributors that influence the weld penetration depth for automotive seat rails, which are: focal position (Z axis) and the quadratic effect of welding speed. This information indicates that the process parameters need to be adjusted the focal position from 224.15 to 224.02 mm. Furthermore, the welding speed range sett was reduced due to its quadratic effect on the output variable: from 28–38 to 28–32 mm/s, as shown in

Figure 6. Finally, the DoE demonstrated that the Laser power should operate at the average level of 2500 kW, which contributes in the long term to optimizing energy consumption.

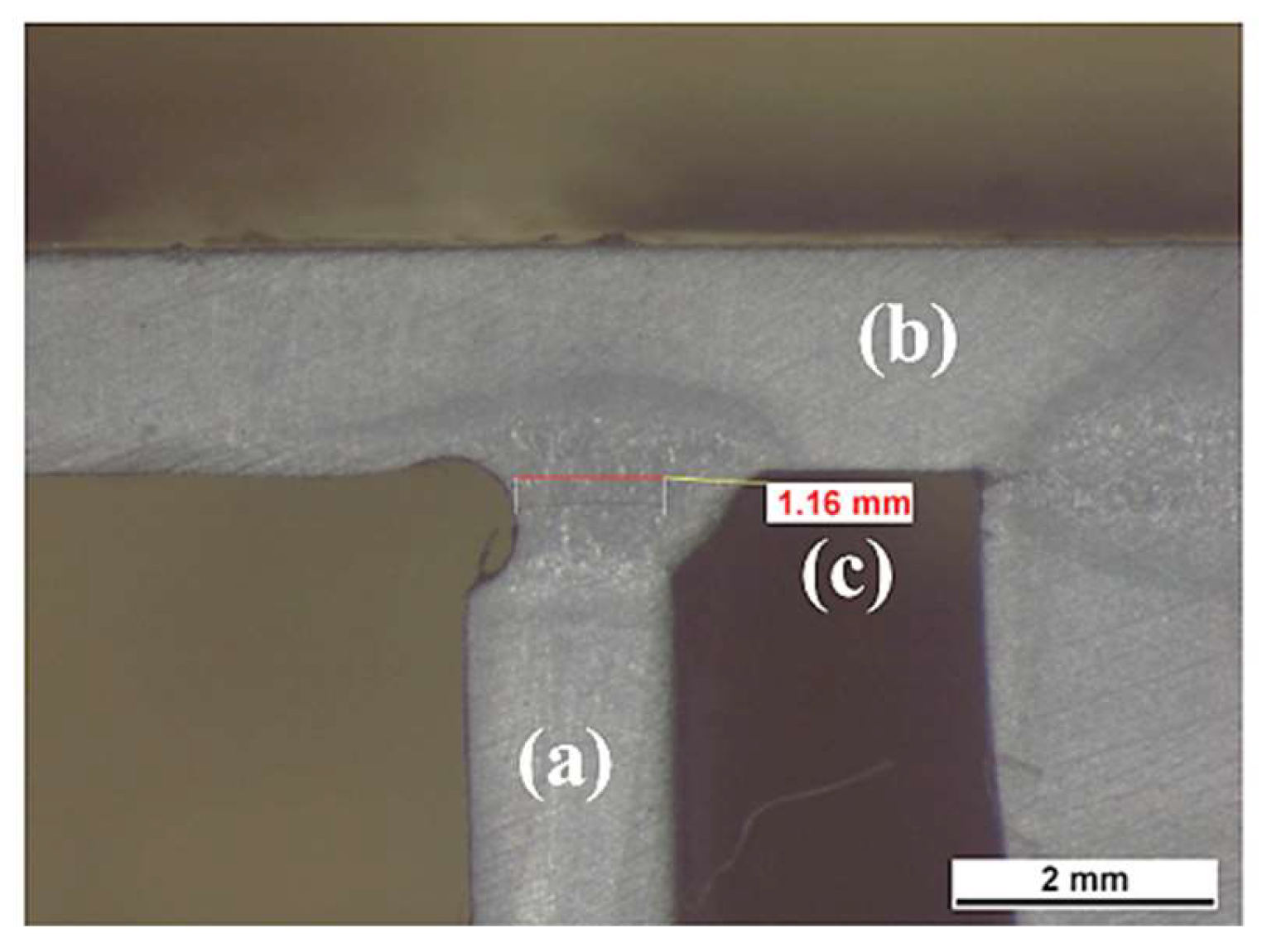

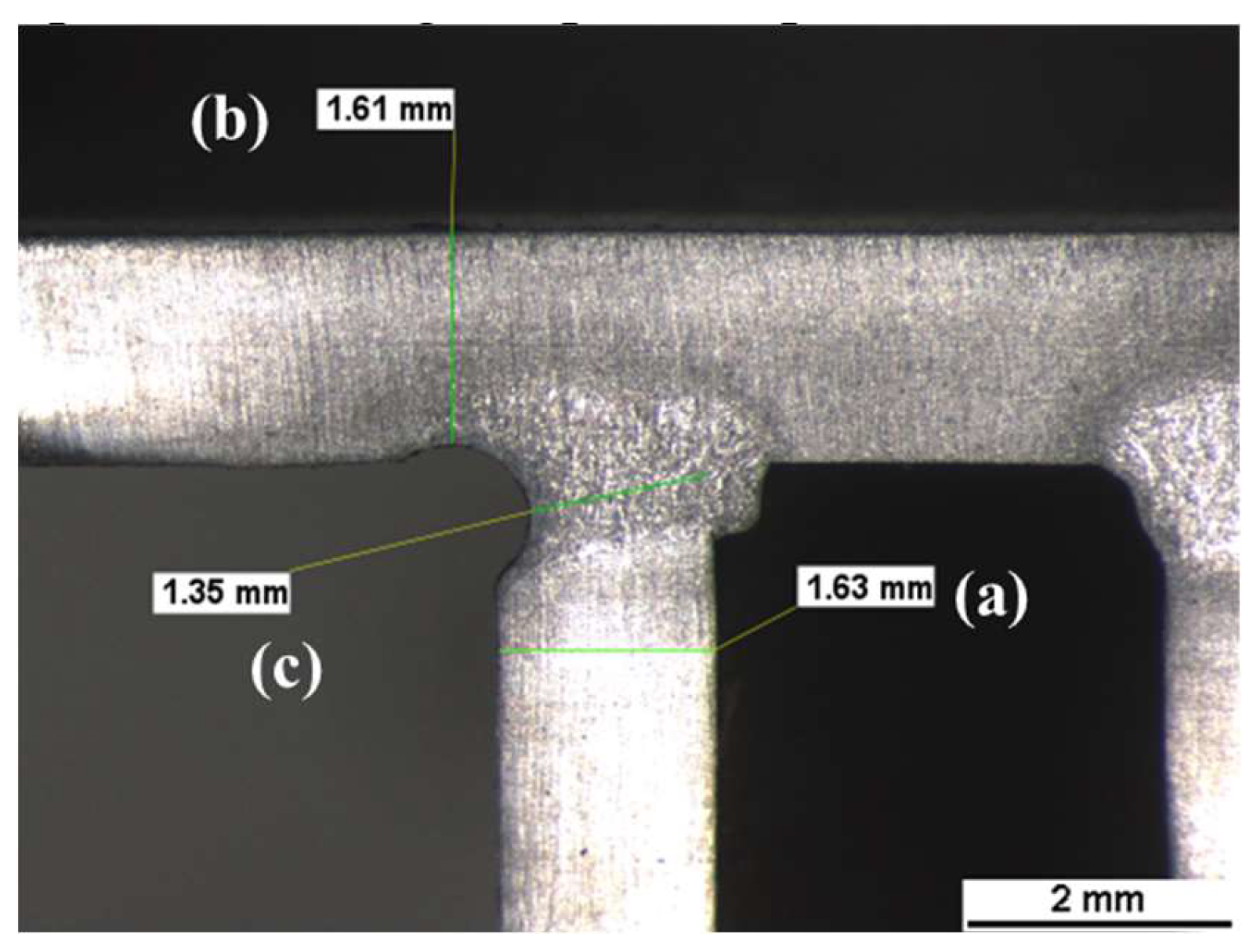

Figure 7 shows a macrograph specimen using the process parameters indicated in

Table 8.

Finally, a validation run was carried out considering the variation due to common causes, that is, different batches of materials and production shifts.

Table 9 indicates the process capability index improved from C

pk = 0.50 to

Cpk = 1.81, this means that the percentage of parts not meeting the required weld penetration depth was reduced from 65,086 parts per million (ppm) to 0 ppm.

Figure 8 graphically depicts the mean change before and after the application of the PDCA framework for waste elimination and process capability improvement. Therefore, the performance optimization of the weld penetration depth process using the LBW machine can be established through RSM.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes the use of the RSM methodology to establish a technical solution to the current problem of adjusting welding parameters in the automotive industry and other industries with similar applications when there is evidence that at least one of the factor analyses affects non-linear the response studied; demonstrating the robustness of this technique to satisfy Cpk requirements, so the following is established:

1. Using the regression equation obtained from DoE, the optimized parameters achieved a Cpk of 1.81 with an R-sq (pred) of 90.46%. Waste generated by failures in weld penetration depth (<1.20 mm) was reduced from 6.51% to 0.00%.

2. The depth of weld penetration in ZE 790 cold-rolled steel joints depends on the focal position of the welding beam, the welding speed, which provides a quadratic effect, and the applied laser power (energy).

3. Using RSM to understand weld penetration depth phenomena before and after response optimization and with a second-order regression (2) is a statistically sound approach to meet customer requirements and current welding standards for light products used in the automotive industry.

4. The methodology discussed in this article is part of a promising efficient and green approach to saving time and money. It involves performing in-depth analysis of multiple scenarios to optimize weld penetration depth, contribute to the sustainability of the welding process, dramatically reduce waste of non-conforming material, and enable more efficient utilization of equipment. As a result, the economic impact of the organization is positively affected.

Figure 1.

Measurable (y) definition of weld penetration depth.

Figure 1.

Measurable (y) definition of weld penetration depth.

Figure 2.

Ground and polished macrograph of ZE 790 steel welded by LBW from a rejected specimen of weld penetration depth not fulfilling the specification (1.20 mm minimum), showing the (a) side panel, (b) upper rail, and (c) weld penetration depth.

Figure 2.

Ground and polished macrograph of ZE 790 steel welded by LBW from a rejected specimen of weld penetration depth not fulfilling the specification (1.20 mm minimum), showing the (a) side panel, (b) upper rail, and (c) weld penetration depth.

Figure 3.

PDCA framework application for the process improvement for the weld penetration depth (y).

Figure 3.

PDCA framework application for the process improvement for the weld penetration depth (y).

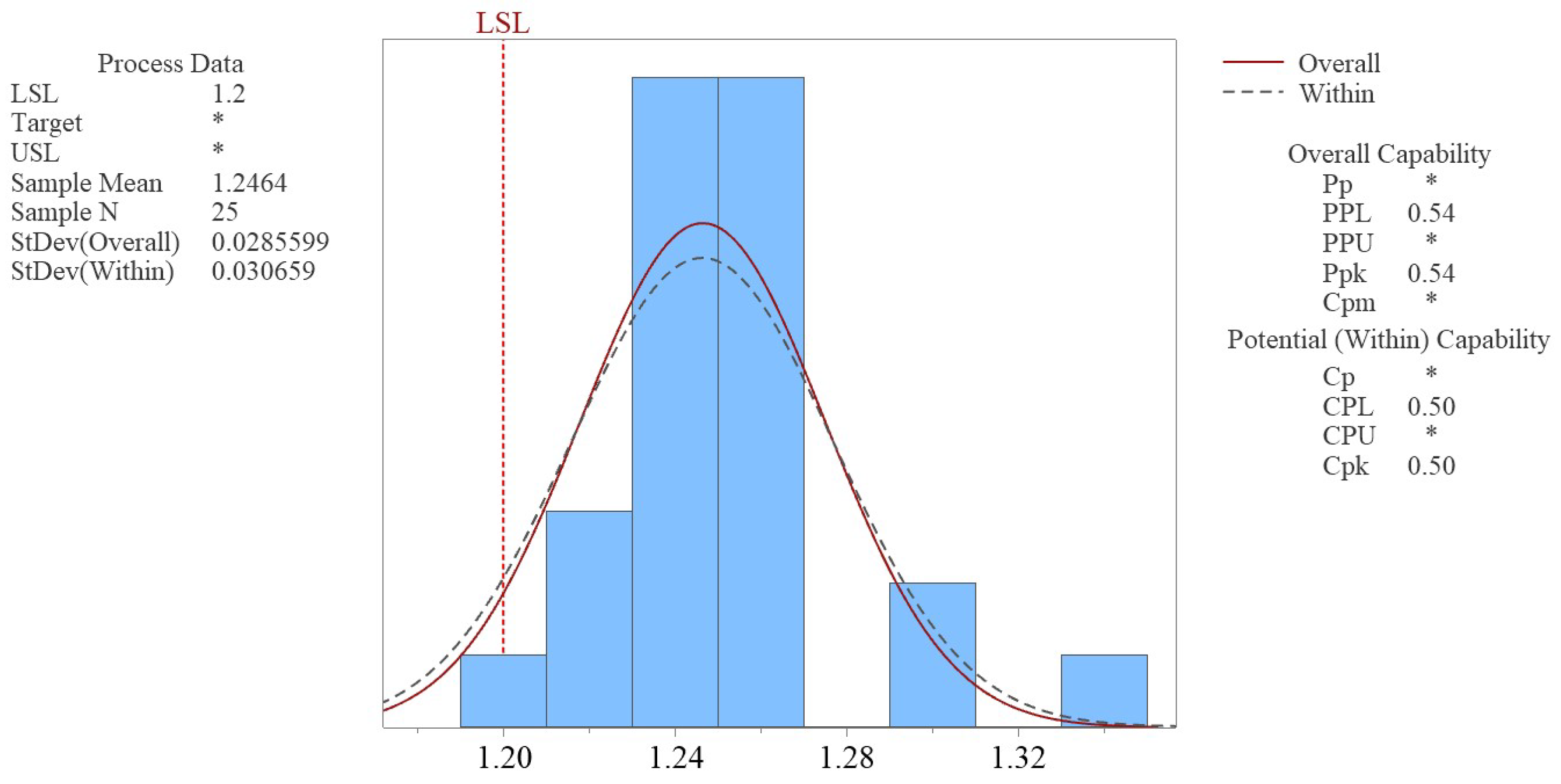

Figure 4.

Baseline process capability assessment for weld depth penetration (mm), where the penetration depth (y) specification is a minimum of 1.20 mm, the average depth is 1.246 mm with a standard deviation of 0.0306 mm, and Cpk = 0.50.

Figure 4.

Baseline process capability assessment for weld depth penetration (mm), where the penetration depth (y) specification is a minimum of 1.20 mm, the average depth is 1.246 mm with a standard deviation of 0.0306 mm, and Cpk = 0.50.

Figure 5.

Half-normal plot of standardized effects on weld penetration depth.

Figure 5.

Half-normal plot of standardized effects on weld penetration depth.

Figure 6.

Contour plots for weld penetration depth (y) in [mm], using Equation (2). a) B–A relationship when C = 0; b) C–A relationship when B = 0; c) C–B relationship when A = 0.

Figure 6.

Contour plots for weld penetration depth (y) in [mm], using Equation (2). a) B–A relationship when C = 0; b) C–A relationship when B = 0; c) C–B relationship when A = 0.

Figure 7.

Ground and polished macrograph of ZE 790 steel welded by LBW after proposed parameters, using RSM: (a) Side panel thickness, (b) upper rail thickness, and (c) weld depth penetration greater than minimum specification (1.2 mm).

Figure 7.

Ground and polished macrograph of ZE 790 steel welded by LBW after proposed parameters, using RSM: (a) Side panel thickness, (b) upper rail thickness, and (c) weld depth penetration greater than minimum specification (1.2 mm).

Figure 8.

Weld depth penetration (mm), process comparison before and after parameters adjustment; considering different batches of raw material and production shifts. *Minimum material thickness.

Figure 8.

Weld depth penetration (mm), process comparison before and after parameters adjustment; considering different batches of raw material and production shifts. *Minimum material thickness.

Table 1.

Comparison of proposed methods to control weld penetration using laser beam welding (LBW) machines.

Table 1.

Comparison of proposed methods to control weld penetration using laser beam welding (LBW) machines.

| Characteristics evaluated by authors |

Madrid et al. [7] |

Schmoeller et al. [9] |

Dos-Santos-Paes et al. [27] |

Pavlicek et al. [28] |

Khorram et al. [29] |

Yufeng et al. [30] |

Krishna-Kumar et al. [31] |

Khann et al. [32] |

Our Proposed |

| Output variable(s): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weld penetration |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Input variable(s): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Power |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Speed |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Focal position |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Joint thickness |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Proposed methodology for analysis: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Empirical experimentation |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

| Analysis of one factor at a time |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

| Design of experiments |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Finite element analysis |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

| Artificial neural networks |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Solution model: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Linear model |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

| Quadratic model |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☐ |

☒ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Model with interactions |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Model validation |

☒ |

☒ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Calculation of process capability |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Actual implementation: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The improvement is implemented |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of ZE 790 steel (wt. %).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of ZE 790 steel (wt. %).

| Material |

C |

Si |

Mn |

P |

S |

Cr |

Mo |

Ni |

Cu |

Al |

V |

| ZE 790 |

0.060 |

0.030 |

0.540 |

0.007 |

0.000 |

0.070 |

0.020 |

0.050 |

0.140 |

0.037 |

0.008 |

Table 3.

Process parameters of the LBW machine for the DoE.

Table 3.

Process parameters of the LBW machine for the DoE.

| Parameter 1

|

Process Range |

| A – Welding speed (mm/s) |

22–30 |

| B – Laser power (W) |

2000–3000 |

| C – Focal position Z-axis (mm) |

223.80–224.50 |

Table 4.

Codification of input variables and experimental levels definition for the DoE.

Table 4.

Codification of input variables and experimental levels definition for the DoE.

| Code |

Factor |

-1 |

0 |

+1 |

| A |

Welding speed (mm/s) |

22 |

30 |

38 |

| B |

Laser power (W) |

2,000 |

2,500 |

3,000 |

| C |

Focal Position Z-axis (mm) |

223.80 |

224.15 |

224.50 |

Table 5.

Weld penetration depth (y) [mm] tally sheet from DoE.

Table 5.

Weld penetration depth (y) [mm] tally sheet from DoE.

| Treatment |

A |

B |

C |

Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

Sample 3 |

| 1 |

−1 |

−1 |

−1 |

1.25 |

1.26 |

1.25 |

| 2 |

+1 |

−1 |

−1 |

1.08 |

1.29 |

1.18 |

| 3 |

-1 |

+1 |

−1 |

1.08 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

| 4 |

+1 |

+1 |

−1 |

1.30 |

1.24 |

1.25 |

| 5 |

−1 |

−1 |

+1 |

0.64 |

0.69 |

0.85 |

| 6 |

+1 |

−1 |

+1 |

0.58 |

0.44 |

0.37 |

| 7 |

−1 |

+1 |

+1 |

0.42 |

0.55 |

0.60 |

| 8 |

+1 |

+1 |

+1 |

0.22 |

0.44 |

0.18 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.24 |

1.23 |

1.21 |

Table 6.

ANOVA results.

| Source |

DF |

SS |

MS |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Model |

6 |

3.52272 |

0.58712 |

58.84 |

0.000 |

| Linear |

3 |

2.86523 |

0.95508 |

95.72 |

0.000 |

| A |

1 |

0.03227 |

0.03227 |

3.23 |

0.087 |

| B |

1 |

0.12615 |

0.12615 |

12.64 |

0.002 |

| C |

1 |

2.70682 |

2.70682 |

271.29 |

0.000 |

| Square |

1 |

0.41082 |

0.41082 |

41.17 |

0.000 |

| A*A |

1 |

0.41082 |

0.41082 |

41.17 |

0.000 |

| Two-way int. |

2 |

0.24667 |

0.12333 |

12.36 |

0.000 |

| A*B |

1 |

0.05227 |

0.05227 |

5.24 |

0.033 |

| A*C |

1 |

0.19440 |

0.19440 |

19.48 |

0.000 |

| Error |

20 |

0.19955 |

0.00998 |

|

|

| Lack of fit |

2 |

0.05568 |

0.02784 |

3.48 |

0.053 |

| Pure error |

18 |

0.14387 |

0.00799 |

|

|

| Total |

26 |

3.72227 |

|

|

|

Table 7.

Coefficients (coded) of the regression equation2.

Table 7.

Coefficients (coded) of the regression equation2.

| Term |

Coef |

SE Coef |

T-Value |

P-Value |

VIF |

| Constant |

1.2267 |

0.0577 |

21.27 |

0.000 |

|

| A |

−0.0367 |

0.0204 |

−1.80 |

0.087 |

1.00 |

| B |

−0.0725 |

0.0204 |

−3.56 |

0.002 |

1.00 |

| C |

−0.3358 |

0.0204 |

−16.47 |

0.000 |

1.00 |

| A*A |

−0.3925 |

0.0612 |

−6.42 |

0.000 |

1.00 |

| A*B |

0.0467 |

0.0204 |

2.29 |

0.033 |

1.00 |

| A*C |

−0.0900 |

0.0204 |

−4.41 |

0.000 |

1.00 |

Table 8.

Regulatory conditions for the operation of the welding process for y ≈ 1.35 mm3.

Table 8.

Regulatory conditions for the operation of the welding process for y ≈ 1.35 mm3.

| Parameter |

Coded |

Non-Coded |

| A – Welding speed (mm/s) |

0 |

30 |

| B – Laser power (W) |

0 |

2500 |

| C – Focal position Z-axis (mm) |

−0.3672 |

224.02 |

Table 9.

Process capability assessment for the specification of a minimum y of 1.20 mm.

Table 9.

Process capability assessment for the specification of a minimum y of 1.20 mm.

| Process |

N |

Mean (mm) |

StDev (mm) |

Min (mm) |

Max (mm) |

Cpk |

% Out of Spec |

ppm |

| Before* |

25 |

1.2464 |

0.0307 |

1.1600 |

1.3100 |

0.50 |

6.51 |

65,086 |

| After * |

11 |

1.3536 |

0.0284 |

1.2700 |

1.4200 |

1.81 |

0.00 |

0 |