1. Introduction

Satellites have been extensively used for applications such as mobile communication, radio and television broadcasting, military intelligence, weather forecasting, and navigation. The launch of satellites Sputnik(83 kg) and Explorer1 (14 kg) by Russia and America respectively marked the beginning of the age of satellites [

1,

2,

3]. Although, small satellites(

kg Mass) were initially popular, large satellites started gaining popularity in the 70s and 80s due to their ability to carry more payload and integrate larger solar panels to generate more power. The production and operation cost of large satellites, which is primarily funded by governments and big companies, led the new developers of satellites to look for cost-effective methods to penetrate the market. Thus, the new era of smaller, cheaper, and better satellites began. Such small satellites bring forth cost-effective and time-saving mission possibilities [

1,

3,

4].

Many companies worldwide are investigating the scope of small satellite technologies and are researching on advancement of such satellites. Some initiatives by NASA, ESA, and JAXA are discussed in references [

1,

5]. The applications of small satellites cover various areas like earth observation, disaster management, space science, microgravity research, earthquake forecast, gravitational field measurements to name a few [

1,

3]. For many applications, two or more small satellites work together to form constellations or formation flying, which is based on whether an active control is used to maintain a relative position or not [

1,

4,

6]. A summary of evolution, rise, and current challenges in small satellites are discussed in detail in Ref. [

3] and a review of the future challenges related to constellations of small satellites is provided in Ref. [

7].

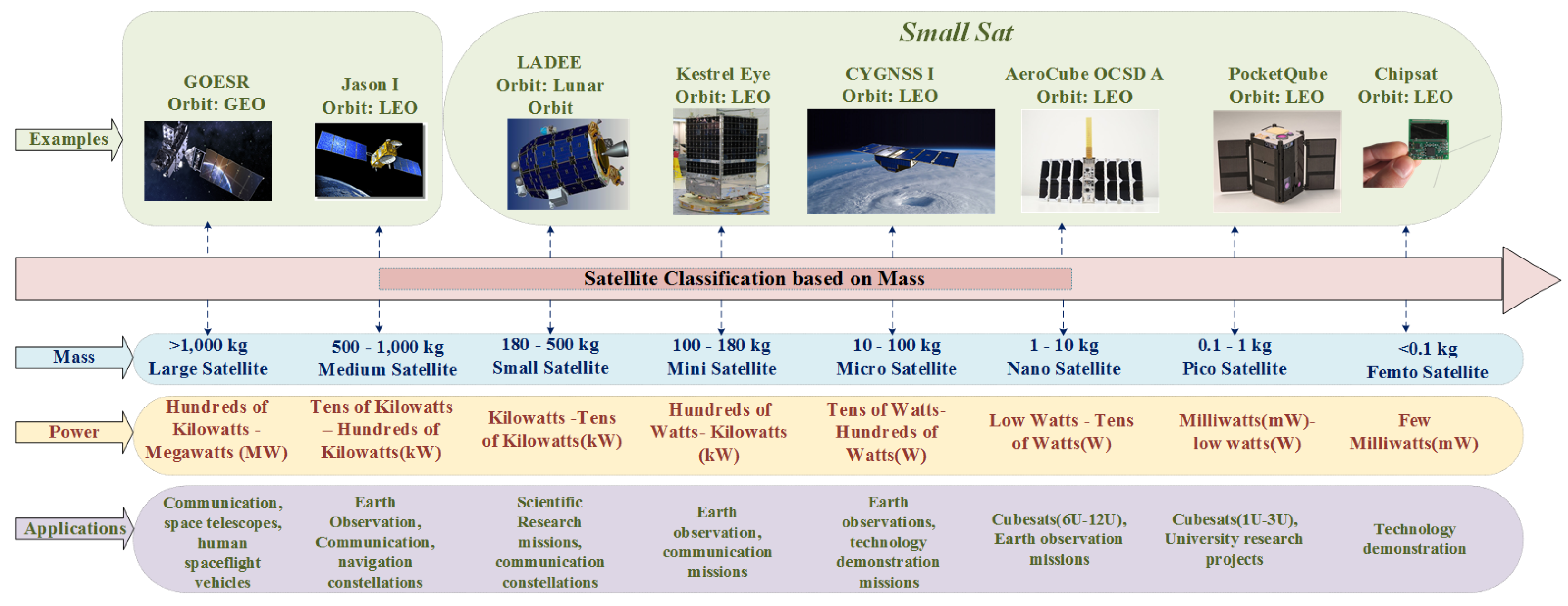

Satellites are classified based on their mass into various categories [

1,

2]. All satellites with a mass

are called small satellites. Large satellites are used for applications with lifetime above 10 years and those which are required to carry large payloads like remote sensing payloads, big antennas for communication, etc. Small satellites use miniature components, hence reducing the mass and size of satellites. Such satellites are competing with the large satellites in many applications and their mission time is comparatively smaller than the large satellites [

1,

8]. The mission’s orbit is another parameter to be considered for satellites. The season and duration of the eclipses experienced by the satellites varies with the type of orbits. The missions can be classified as low earth, Geosynchronous (GEO) earth, Medium earth, or deep space missions.

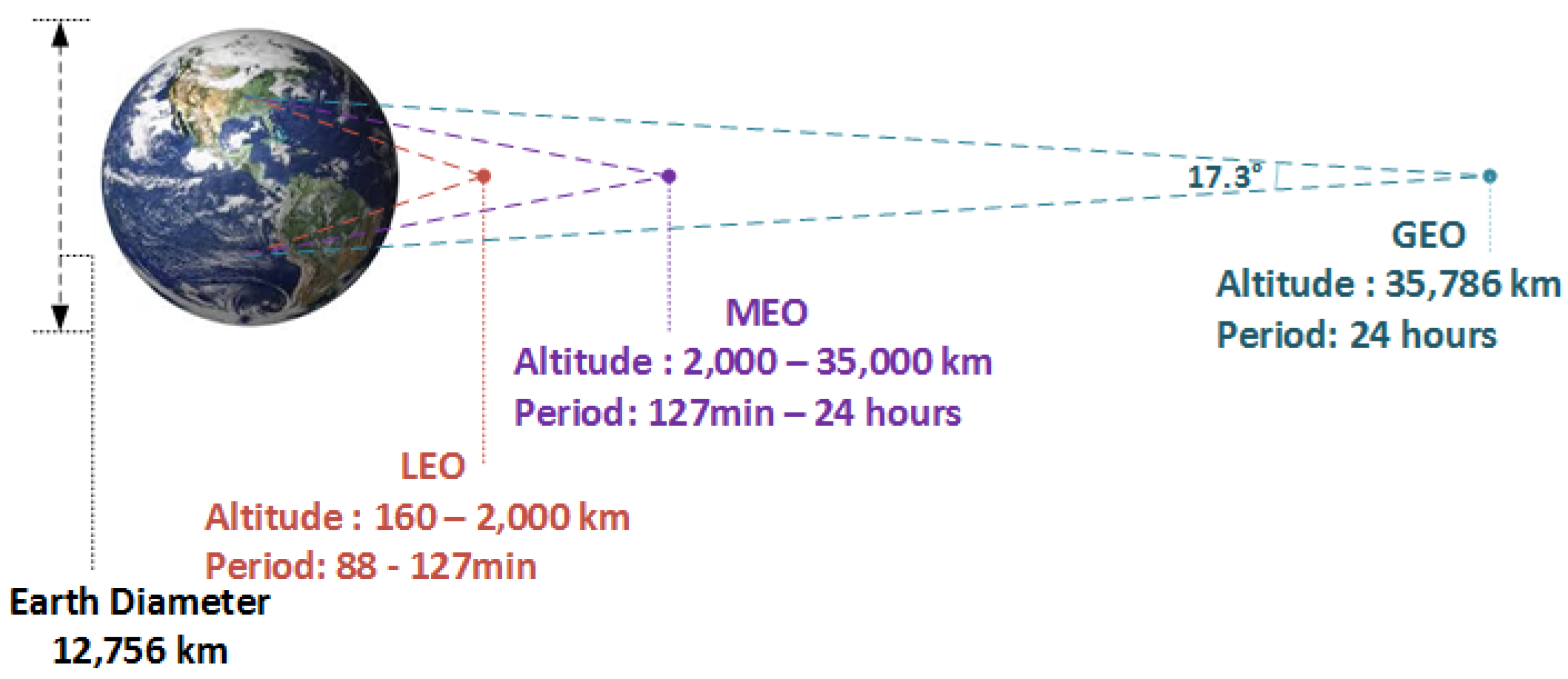

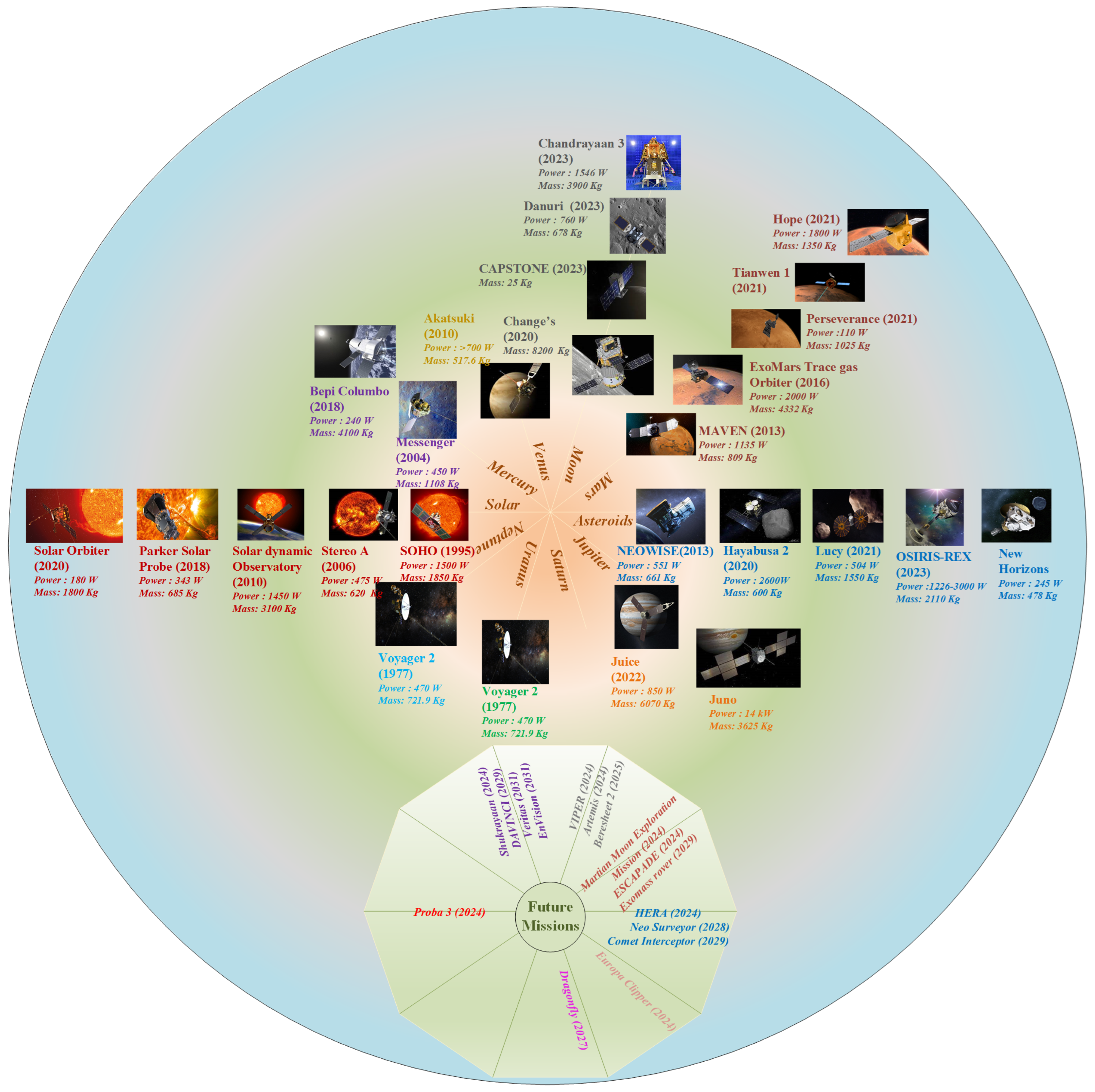

Figure 1 shows these missions and their relative distances from the surface of earth and

Figure 2 shows various types of satellites based on their mass and their corresponding power ratings [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Low earth orbit (LEO) missions finds application in remote sensing, while GEO orbit is mainly used for communications and broadcasting. Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) satellites are used for navigation, communication, and geodetic/space environment science [

9,

16].

Large or small, a bus system and a payload system are the two important components of a satellite. The elementary operations of the satellite are performed by the bus while the payload performs the mission-specific tasks. EPS is one of the main and critical subsystems of the bus [

17]. Around 33% of the overall mass of satellite is contributed by EPS[

18]. The EPS is designed based on the time span of the mission, orbit height from the surface of earth, solar panel sizing requirements, load demand, heaviness of the satellite, radiation effects, efficiency, component count, battery requirement, reliability, redundancy, and fault tolerance level [

19,

20]. Thus, the overall reduction in size of the satellites requires a smaller EPS with high efficiency. Satellites are classified as a non-serviceable remote autonomous vehicle, thus demanding long life-spans and large end-of-life (EOL) performance parameters. Hence, their design is pivotal in providing the best solution for a given mission ensuring high efficiency and reliability of the overall satellite system [

21]. The EPS comprises an energy source in the form of solar array, an energy storage unit mostly, Li-ion battery and a unit for controlling and distributing power, called PCDU [

22].

The predominantly used primary power source in satellites is the photovoltaic (PV) cells arranged in arrays. During eclipses or during instances when the solar arrays are unable to achieve the peak power demand, secondary batteries are used to provide the required power. Specific energy, depth of discharge, safety, cost, voltage, shelf-life, and resistance to shock and vibration are some parameters considered when selecting rechargeable batteries for satellites [

23]. Generally, Lithium-ion batteries are a good choice for battery storage systems in satellites. A detailed review of various energy storage techniques for small satellites is provided in [

5]. The PCDU forms an interface between the PV array and storage systems or loads, by ensuring effective conditioning and transmission of power. The PCDU is designed for specific missions based on the requirements and requires a detailed study to make an optimal choice [

21].

A satellite’s propulsion systems are crucial because they enable formation flying, interplanetary paths, collision avoidance, orbital maneuvering, station holding, and orbit transfers [

24,

25]. Electric Propulsion(EP) has been gaining popularity, especially in small satellites in recent years as they have better fuel efficiency compared to chemical propulsion used in large satellites. Better fuel efficiency is guaranteed by high specific impulse (

), which is essentially a gauge of the propellant’s ability to produce thrust efficiently [

26,

27]. The Space Electric Rocket Test spacecraft equipped with an ion engine, launched in 1964, and the Zond-2 spacecraft used a pulsed plasma thruster, are considered the first illustration of EP [

28]. Ref. [

29] reviews the recent challenges and solutions related to space electric propulsion. Currently, over 1000 small satellites are active in space. These small satellites are mostly confined to the LEO orbits as they do not possess sufficient

for moving past earth orbits. A system that can raise the orbit from LEO to MEO to GEO and beyond would be more cost-effective than directly launching the satellites to orbits farther than LEO. The potential of an EP system to raise orbits is predominantly determined by the duration it can last and the amount of thrust it can provide. Despite its high fuel efficiency, EPs face a variety of challenges. One of the main challenges is the time taken to reach high thrust, which limits their use to certain applications only. One solution is the use of high-power systems improves the time taken to reach high thrust, providing more opportunities for timely orbit changes and interplanetary missions. However, achieving high power without increasing the overall mass or cost is another challenge. Thus, researchers around the world are focusing on enhancing the EP systems to improve the small satellites’ mission ranges [

24]. Ref. [

30] compares various EP systems and Ref. [

31] compares EPs for mini/microsatellites.

High efficiency is necessary for satellite applications, as the weight that can be launched into space is crucial. Transmitting power in satellites at a high voltage (HV) and low current is an excellent way to reduce weight [

34]. In this context, distributing power as DC is a reliable option leading to simpler equipment and improved efficiency [

35]. However, it demands a wide variety of DC-DC converters. Thanks to the recent development in power electronics which provides a variety of DC-DC converter topologies to choose from. Nevertheless, choosing the best topology for a particular application in satellites is a challenging task as it is decided by the type of the satellite and orbit, duration, and power requirement for the mission. Thus, it is important to compare the various topologies and specify their merits and demerits for various types of missions.

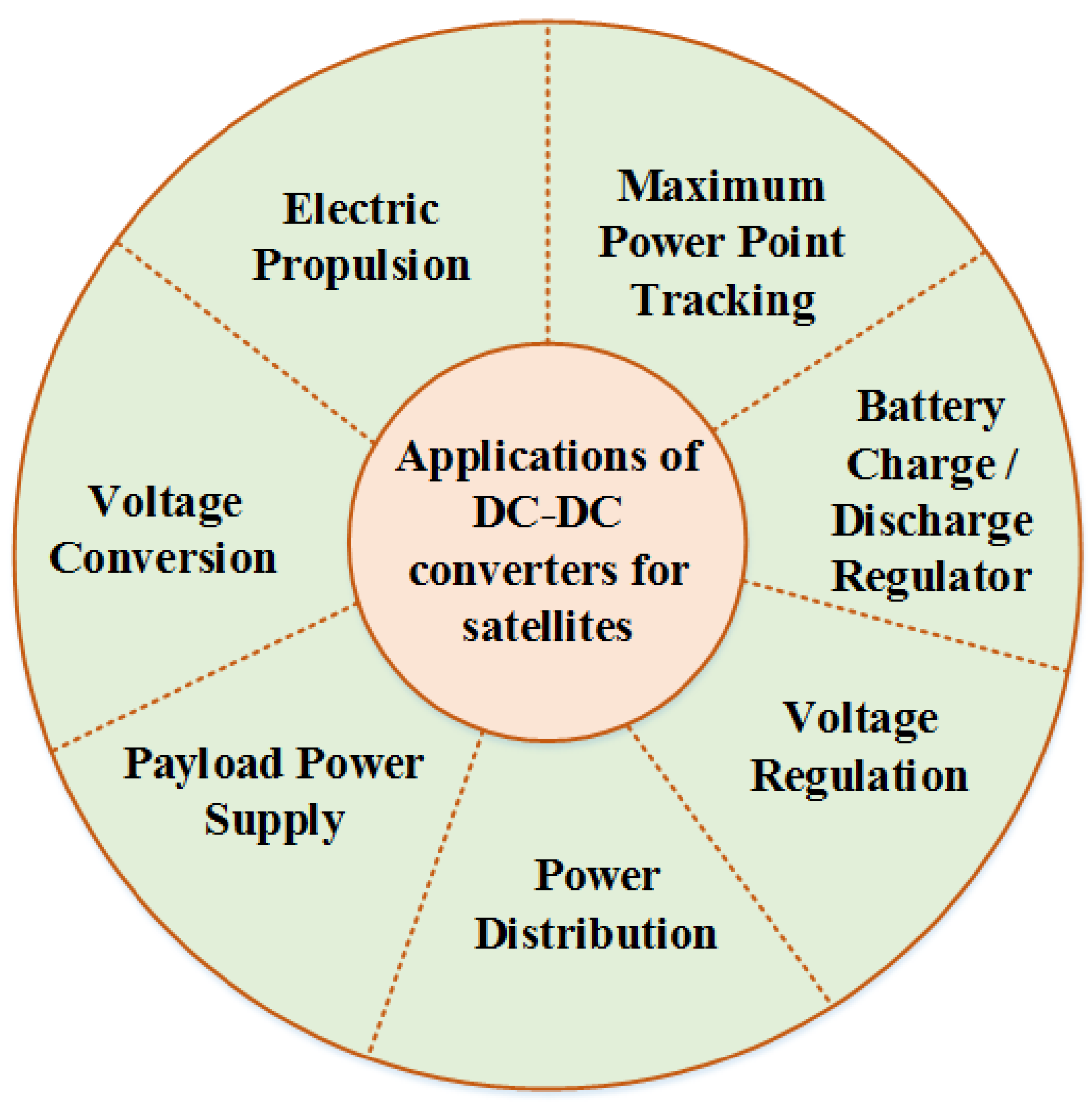

Figure 3 shows the various applications of DC-DC converters in satellites, and

Table 1 compares the major performance indicators for a few applications of DC-DC converters at high-power levels to show their difference with respect to satellite applications. Existing review articles comparing DC-DC converters for satellite applications are provided in

Table 2. Ref. [

32] compares Boost-based non-isolated DC-DC converter topologies for satellite MPPT application. However, the study does not consider other non-isolated or isolated topologies or other applications. M.Yaqoob et.al. [

33] provides a detailed study on small satellite microgrids where the authors review DC-DC converter topologies, solar arrays, and battery technologies for satellites. However, the scope of the study is limited only to small satellites, especially nano-satellites, and does not discuss electric propulsion for satellites. These studies are either limited to certain applications or types of satellite and do not compare the topologies based on the practical performance indicators as stated in

Table 1. Moreover, these articles do not offer any novel ideas for enhancing the current system—rather, they only evaluate the existing literature.

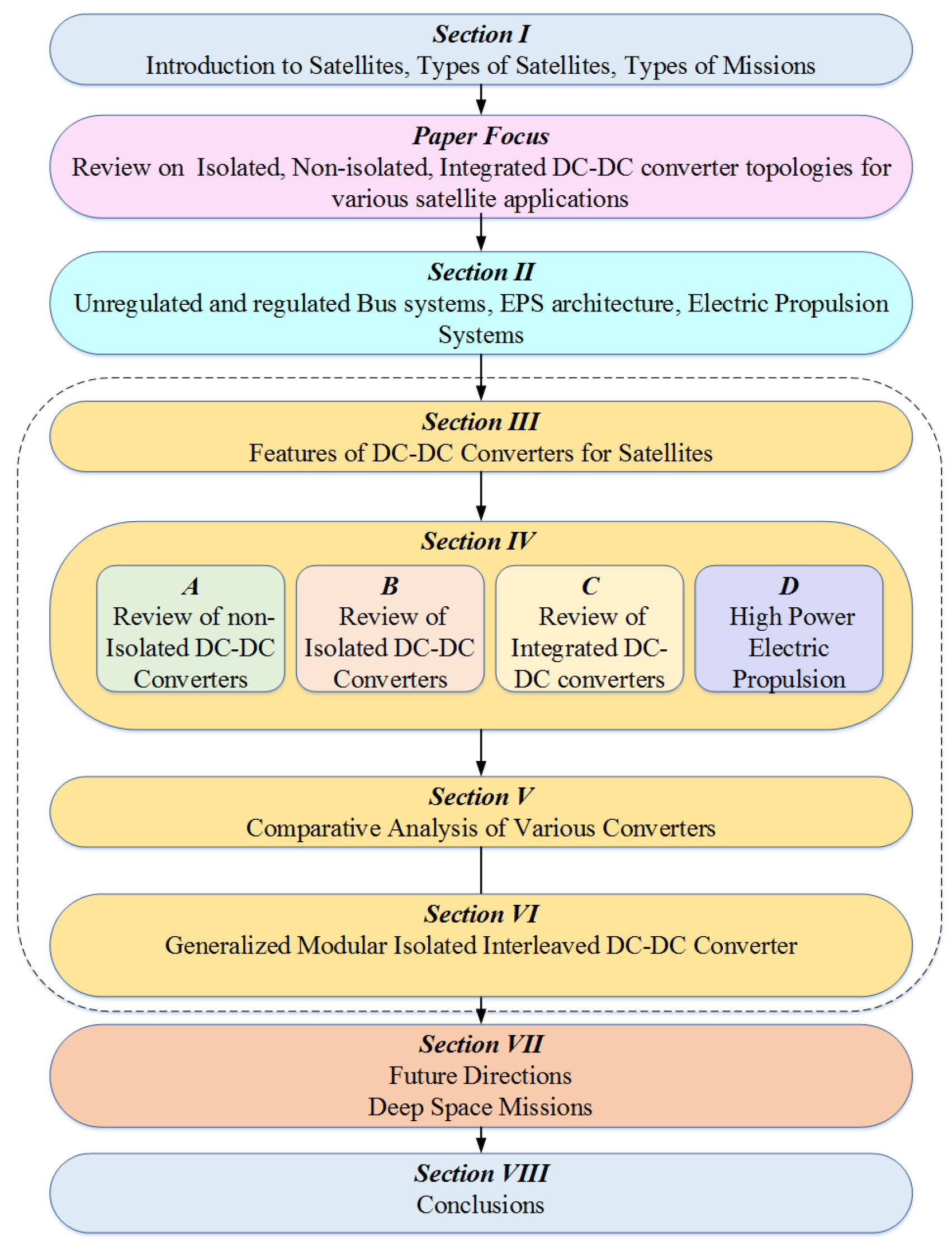

This review article provides an in-depth review of DC-DC topologies for various satellite applications. The scope of the review is not limited to small satellites or earth-orbiting satellites but also considers large satellites, interplanetary, and deep space missions. The article spans a wide range of applications of DC-DC converters for satellites. Different from the existing literature, the topologies are compared using various practical parameters and applications. This paper also makes a distinct contribution by proposing a generalized Modular Isolated Interleaved DC-DC converter topology, which helps improve the reliability, power density, and efficiency of the existing system. The simulation results of the proposed method, taking Cuk converter as an example are presented. The important contributions of the article are mentioned below, and the graphical abstract is provided in

Figure 4.

Identify the design requirements for DC-DC converters and provide an up-to-date review of various isolated and non-isolated topologies for satellite applications.

Analyze the scope of electric propulsion for future manned and deep space missions and review DC-DC converters for electric propulsion applications.

Performance evaluation for the considered topologies in terms of practical parameters (like reliability, power density, size, efficiency, redundancy, modularity, and performance in harsh environmental conditions) and identify the best topology for a considered application in satellites.

Classification of the converters based on various applications and types of satellites.

A novel generalized Modular Isolated Interleaved topology is presented in which each module works at a small fraction of the total rated power. The topology provides improved reliability, efficiency, and reduced weight. The MATLAB simulation results of the converter are provided for a rated power of , taking Cuk converter as an example.

The article is expected to be a guide for researchers and space industries for selecting the best topology, given a satellite application. The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows: section II discusses the various electrical subsystems in satellites, section III focuses on the applications of DC-DC converters in satellites and the design constraints for such converters for satellite applications. Section IV reviews the various isolated, non-isolated, and integrated topologies of DC-DC converters and their comparison is provided in section V. Section VI discusses the generalized Modular Isolated Interleaved topology. Section VII discusses the future directions in the area and provides insight into the current and future deep space missions. Section VIII concludes the paper.

5. Comparative Analysis of Various Topologies

This section provides the performance analysis and comparison of the various DC-DC converter topologies for application in satellites. The converters’ switching frequency can be raised to minimize filter size and boost power density while still meeting design specifications. Nevertheless, a larger switching frequency leads to increased switching losses and demands higher heat dissipation requirements. This also leads to reduced efficiency. Therefore, a trade-off exists between power density, efficiency, and heat dissipation requirement in the converter [

110]. Galvanic isolation is also an important requirement of satellite converters considering safety reasons and to prevent fault propagation within the satellite subsystems [

110]. Regarding efficiency, high-efficiency operation reduces fuel consumption and increases the life of the satellite. Moreover, it leads to lower heat dissipation requirements, lower cost, and improved reliability and power density. Semiconductor switches account for the majority of the losses in power converters. In high-power satellite applications, parallel connection of several modules called modularization is done to improve the voltage and current capacities [

80]. It enhances the performance by increasing the redundancy, ease of maintenance, scalability, and fault ride through capabilities of the converter [

111].

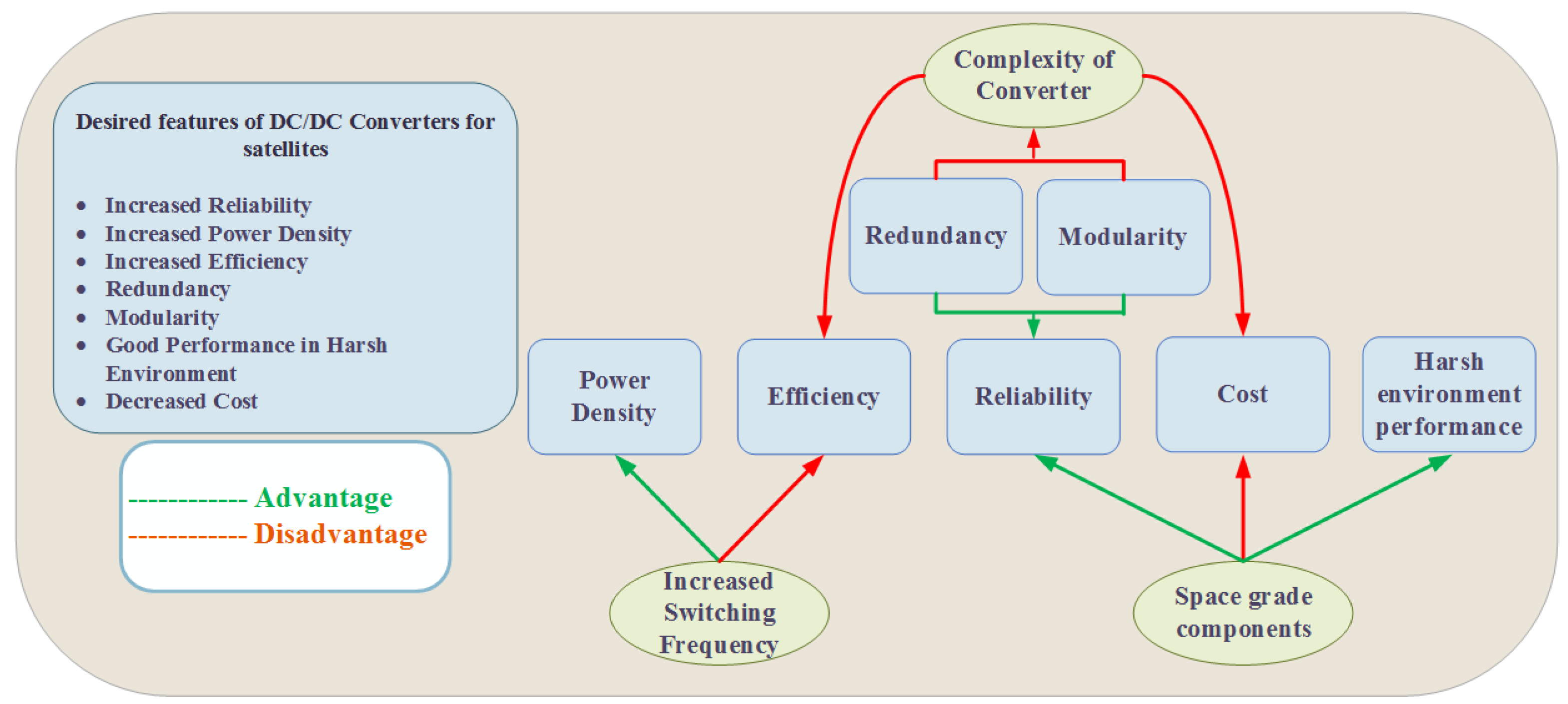

Figure 27 shows the various performance indicators for DC-DC converters for satellite applications.

The most important consideration for satellite applications is reliability, which must be weighed against other considerations like converter cost, efficiency, and power density. The lower the component count, the greater the reliability. Switching devices and their control circuits are considered the parts most prone to failure in a power converter. Capacitors are the next, as they are prone to failure, especially during high temperature applications. Although they are troublesome and seriously question the reliability, they are unavoidable. To improve the performance, space grade components are used, although at an increased cost [

112]. Redundancy and modularity are two important means of improving reliability. The comparison of various non-isolated, isolated, and integrated topologies in terms of the performance parameter mentioned in

Figure 27 is shown in

Table 7,

Table 8, and

Table 9, respectively. The performance comparison of high-power DC-DC converters for EP is shown in

Table 10. A comparison of the topologies based on their application in satellites and the types of satellites that they can be used for is provided in

Table 11.

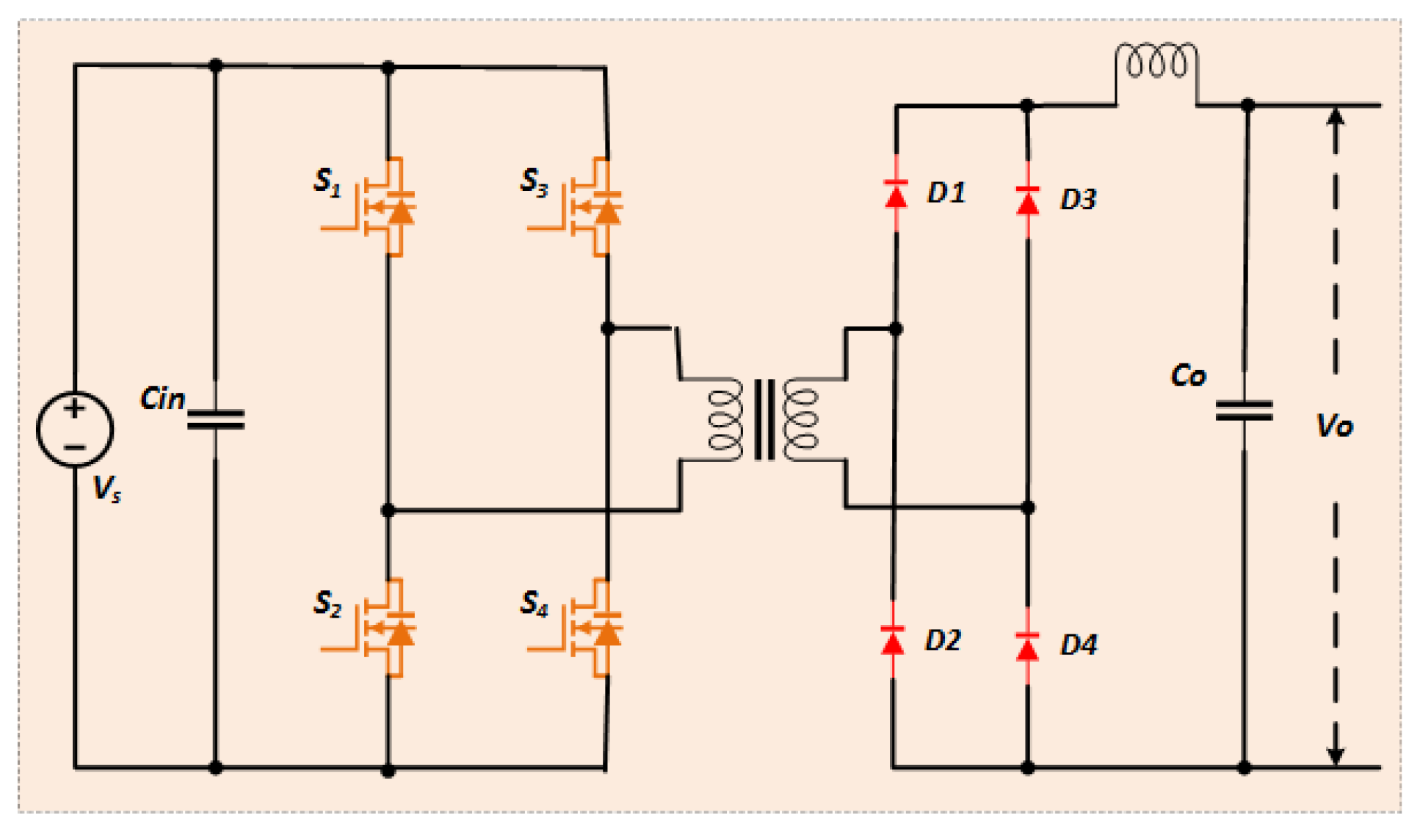

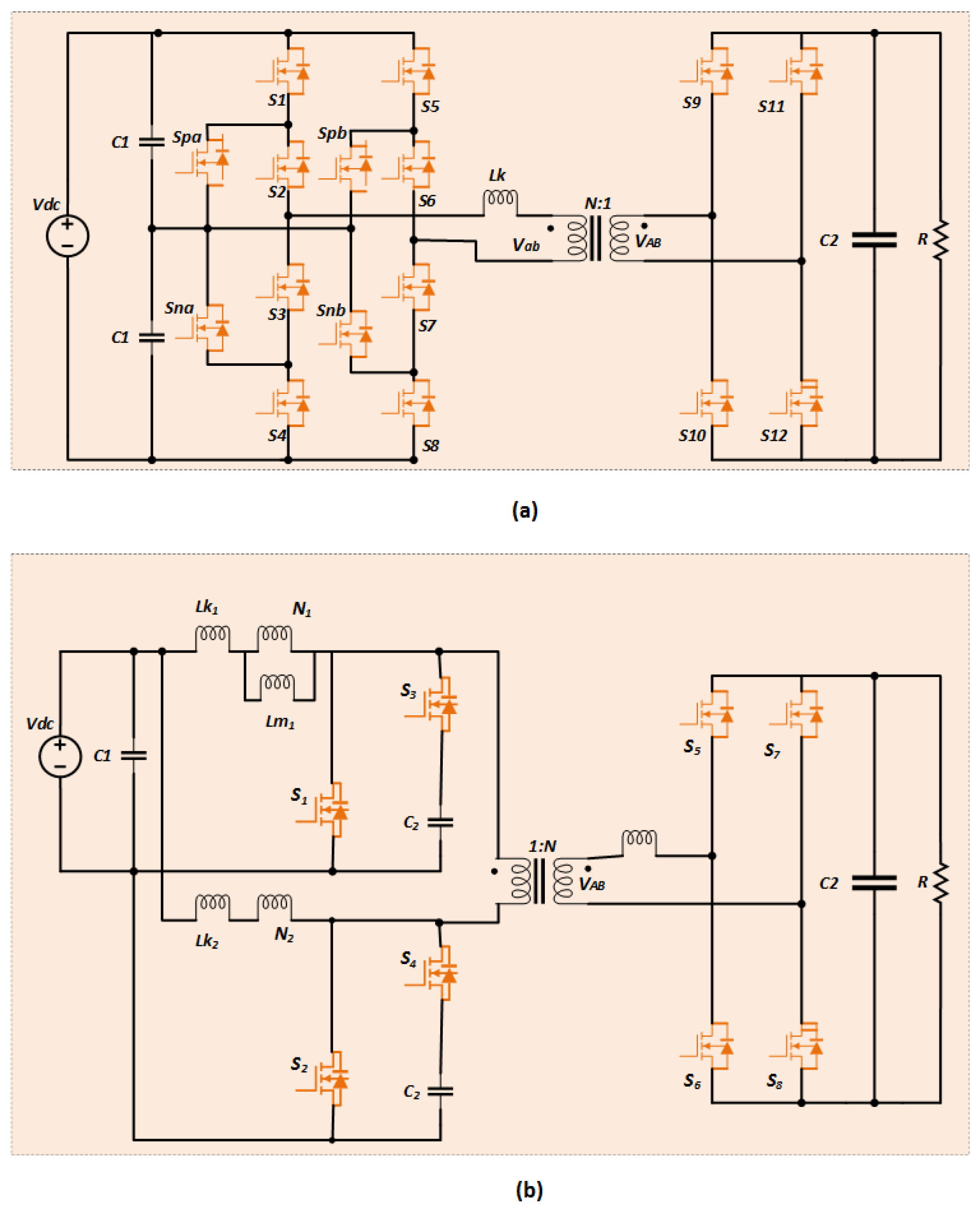

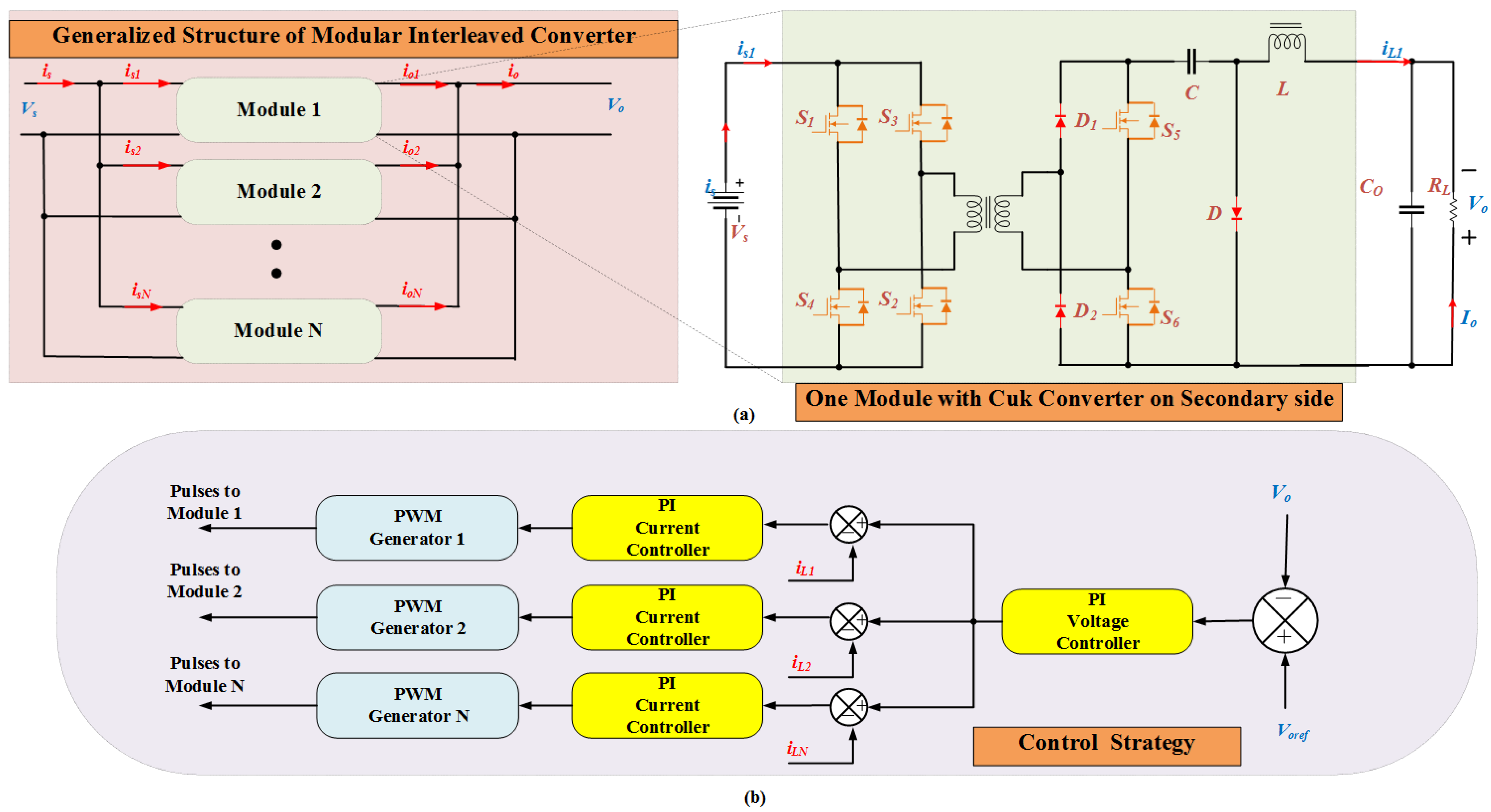

6. Modular Interleaved Cuk Converter

In view of the presented review on DC-DC converter topologies for satellite applications, a generalized Modular Isolated Interleaved topology is presented in this section. Reliability being a critical performance parameter, a modular design where converters are connected in parallel is proposed, which helps improve reliability. Paralleling DC-DC converters provide advantages like low semiconductor stresses, improved reliability, ease of maintenance and repair, and improved thermal management to name a few [

113]. The parallel connected modules are also interleaved, as interleaving provides a reliable converter with a lower value of output current ripple, reduced switch current stress, and improved efficiency [

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119]. In interleaving, multiple module switches are turned ON/OFF with a time delay of

such that,

where n is the number of modules connected in parallel. The input current

and output current

for each module is given by

where

and

are the effective input and output currents, respectively. According to [

115], for an interleaved converter with N modules, the relationship between total output current ripple,

and the output current ripple for each phase,

is given by

where

is the cancellation factor which lies between 0 and 1 and D is the duty ratio. The increased frequency of output current ripple due to interleaving leads to reduced size of the magnetics and lowers the converters’ total dimensions. In parallel connected converters, it is important to ensure equal sharing of power among the modules, and this is achieved in the proposed topology by using appropriate control techniques. The control strategy for IPOP systems as proposed in [

111] is employed for ensuring equal current sharing. Such modular designs can be easily incorporated into satellite applications, especially at high-power. The control strategy and a generalized model of the suggested method are displayed in

Figure 28a,b.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the method, MATLAB simulation is performed. On the primary side, a Full-bridge converter is used due to its inherent advantages as stated in section IV(B). On the secondary side, a totem-pole Cuk converter is used. Cuk converter is quite popular due to its ability to provide continuous current at the input and output side and high efficiency when operated in continuous conduction mode. Although the Cuk converter is used to demonstrate the findings, other Buck-Boost converter types, such as SEPIC, Zeta, Luo, etc., can also be used to apply the suggested method. The major goal of presenting the topology in this work is to illustrate to the readers the benefits of converter interleaving and paralleling for high-power satellite applications to guarantee system reliability. Nevertheless, a comprehensive analysis of theoretical and practical data is necessary to validate the best topology for these kinds of applications. We let the reader make that decision and provide opportunities for more research into different Buck-Boost topologies that can be used for these kinds of systems. For this reason, the in-depth mathematical analysis and modeling of the converter are not covered here. Many scholarly works, including [

120,

121,

122,

123,

124], provides a thorough examination of the Cuk converter. Additional Buck-Boost topologies designed and analyzed are available in [

125,

126,

127,

128,

129]. Also, the detailed mathematical analysis of control strategy for IPOP systems can be found in [

111,

130,

131]. The converter is designed for a total power of

with two modules. The circuit values for simulation model are given in

Table 12 as per the design provided in [

132,

133]. A parameter mismatch is introduced between the modules in terms of the Cuk capacitor and output inductor to show the effectiveness of the controller in ensuring equal current sharing between the modules.

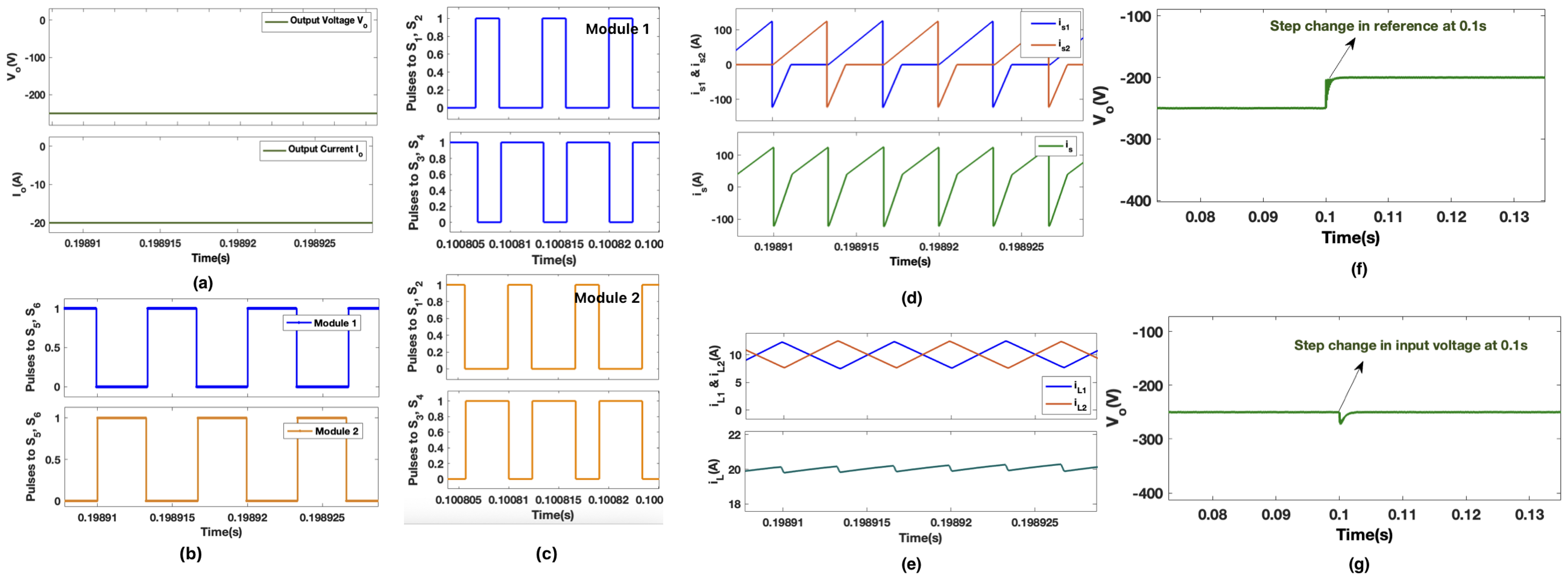

The results of simulation are provided in

Figure 29,

Figure 30, and

Figure 31.

Figure 29 shows the results of the simulation of the converter with two interleaved modules (switching pulses phase shifted by 180 degrees), where each module handles a power of

. As seen from the figure, the input currents and output currents are equally distributed among the modules. Also, interleaving increases the frequency of inductor current ripple by a factor of 2. The robustness of the controller is verified by providing a step change in reference voltage from

to

and a step change in input voltage from

to

at 0.1s. The respective results are shown in

Figure 29f,g.

Figure 30a,b show the inductor currents with a single module where the module power is

for a switching frequency of

and

respectively. The ripple in the inductor current is reduced when the switching frequency is raised.

Figure 30c shows the module Inductor currents and total inductor current at

switching frequency for the converter with three modules, where each module handles

power. Comparing

Figure 30a,c the inductor current ripple significantly reduced with more modules. While the ripple is

with a single module, it is reduced to

with three modules. Additionally, the inductor current ripple frequency becomes thrice of that with a single module, which implies reduced size of magnetics and improved power density.

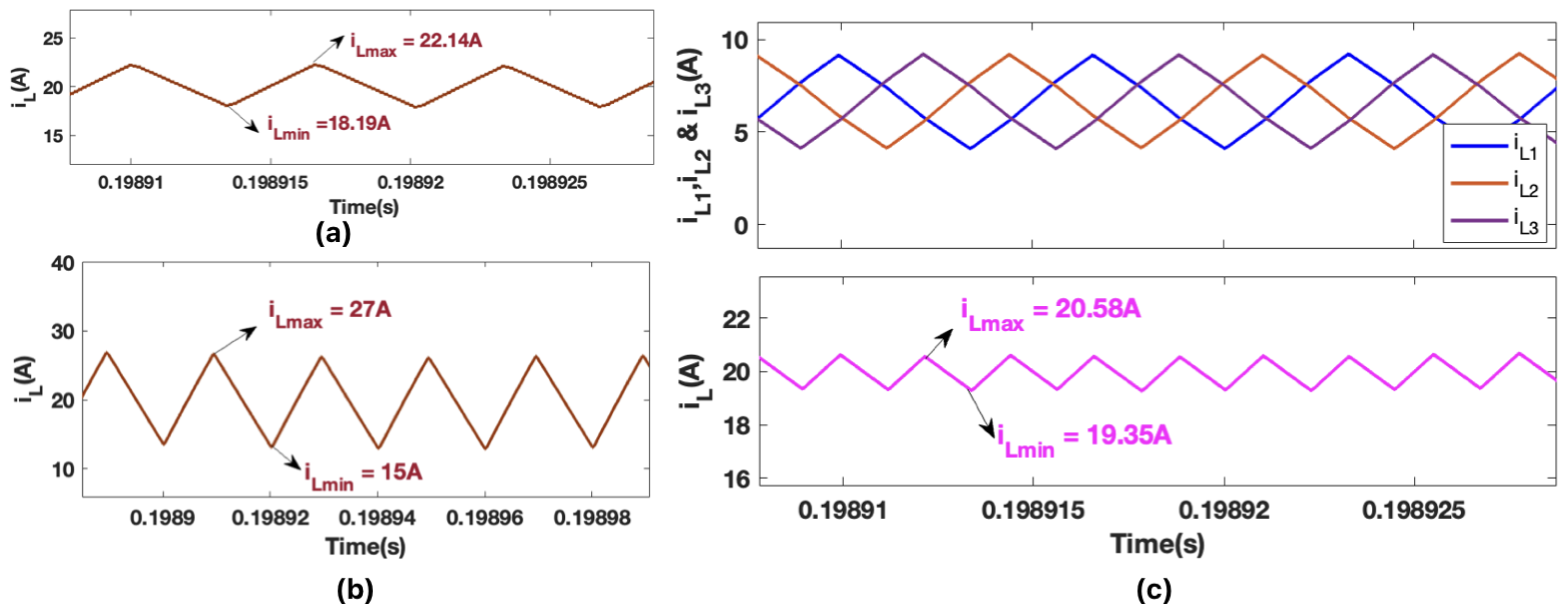

A comparison of switch/diode current stress and efficiency with number of modules is provided in

Figure 31a and

Figure 31b, respectively. Results show that switch current stress is significantly reduced with number of modules. As seen from the figure, the current stress across switches

,

and diode D, reduces by approximately

when the number of modules is increased from 1 to 3. The approximate efficiencies for one, two, and three modules of the converter are measured from simulation results. It demonstrates that adding one module enhanced efficiency by about 2%, and adding two modules increased efficiency by about 2.7%. This is explained by the fact that the switches’ reduced current stresses result in lower conduction losses. The detailed mathematical equations pertaining to power loss analysis of such types of converters are found in [

134,

135]. Moreover, improvement in efficiency can be attained by the use of WBG devices, as they have low switching losses enabling high switching frequency operation [

110,

136,

137,

138]. Reliability and efficiency are the two prime requirements for satellite applications, and lower switch stresses translate into improved converter reliability and efficiency. Consequently, this topology shows promise for use in high-power satellite applications.

While simulation results utilizing a Cuk converter on the secondary side are used to illustrate the suggested topology results, further research is necessary to see the applicability of other types of Buck-Boost converters. To further demonstrate the efficacy of the converter, a thorough theoretical investigation involving mathematical modeling, a mathematical analysis of the control strategy, a power loss analysis, conditions for the converter’s soft-switching, and practical validation must be carried out. In the future, this will be studied independently.

Figure 1.

Types of missions and their distances from earth.

Figure 1.

Types of missions and their distances from earth.

Figure 2.

Classification of satellites based on their mass and approximate power levels.

Figure 2.

Classification of satellites based on their mass and approximate power levels.

Figure 3.

Applications of DC-DC converters for satellites.

Figure 3.

Applications of DC-DC converters for satellites.

Figure 4.

Graphical abstract of the Paper.

Figure 4.

Graphical abstract of the Paper.

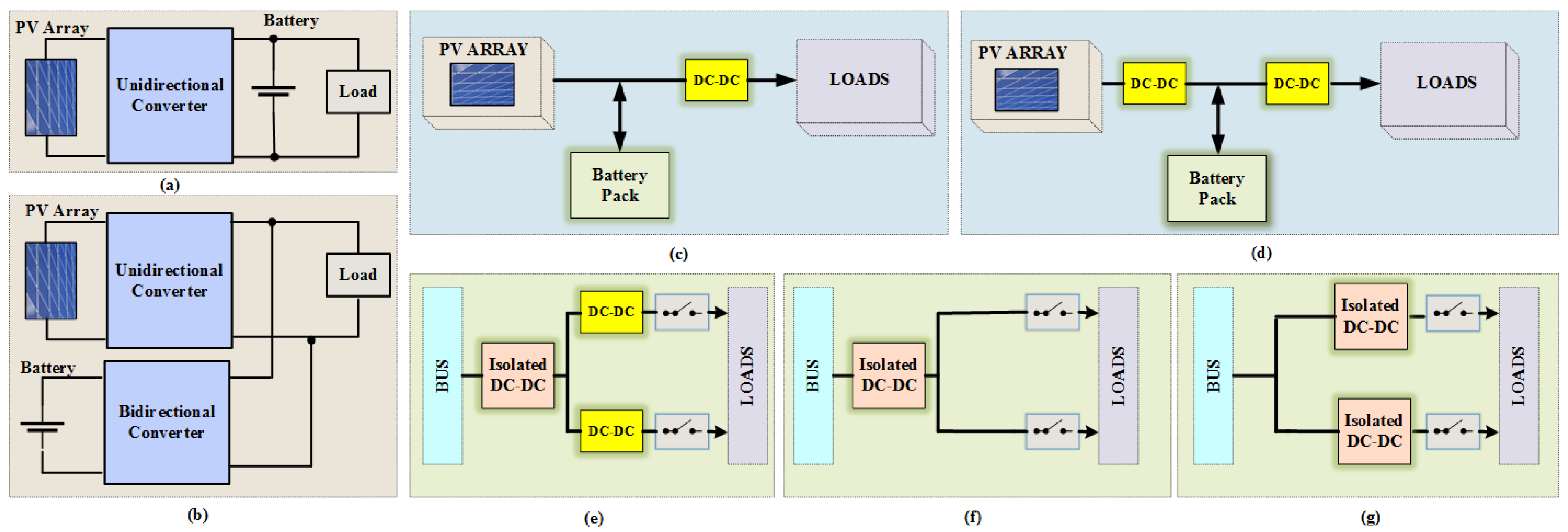

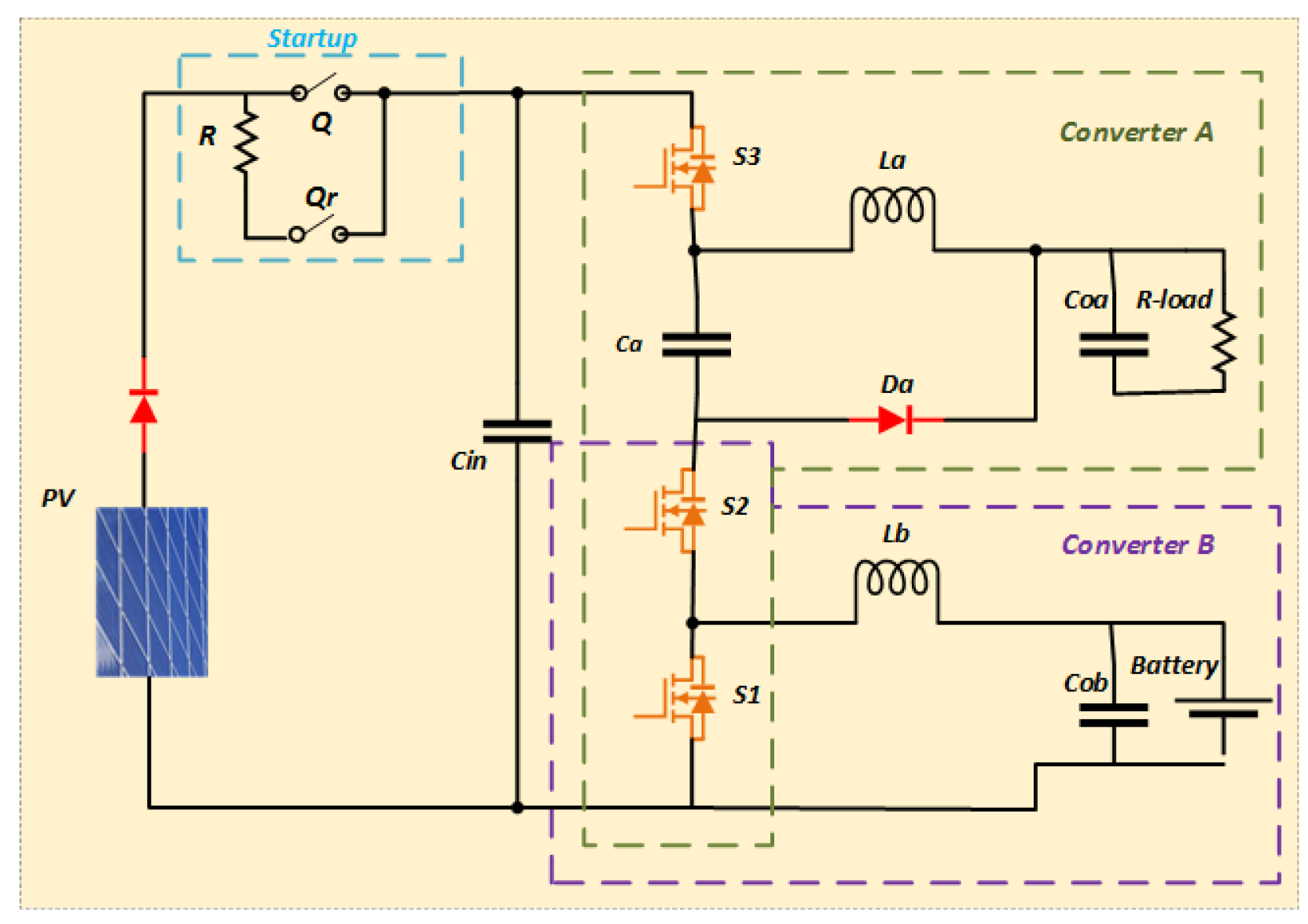

Figure 5.

EPS Bus System (a) Unregulated (b) Regulated and EPS Architecture for Power Distribution (c) DET and (d) MPPT. (e) Distributed Architecture (f) Decentralized Architecture with One Input and Many Outputs (g) Decentralized Architecture with Multiple Isolated Converters.

Figure 5.

EPS Bus System (a) Unregulated (b) Regulated and EPS Architecture for Power Distribution (c) DET and (d) MPPT. (e) Distributed Architecture (f) Decentralized Architecture with One Input and Many Outputs (g) Decentralized Architecture with Multiple Isolated Converters.

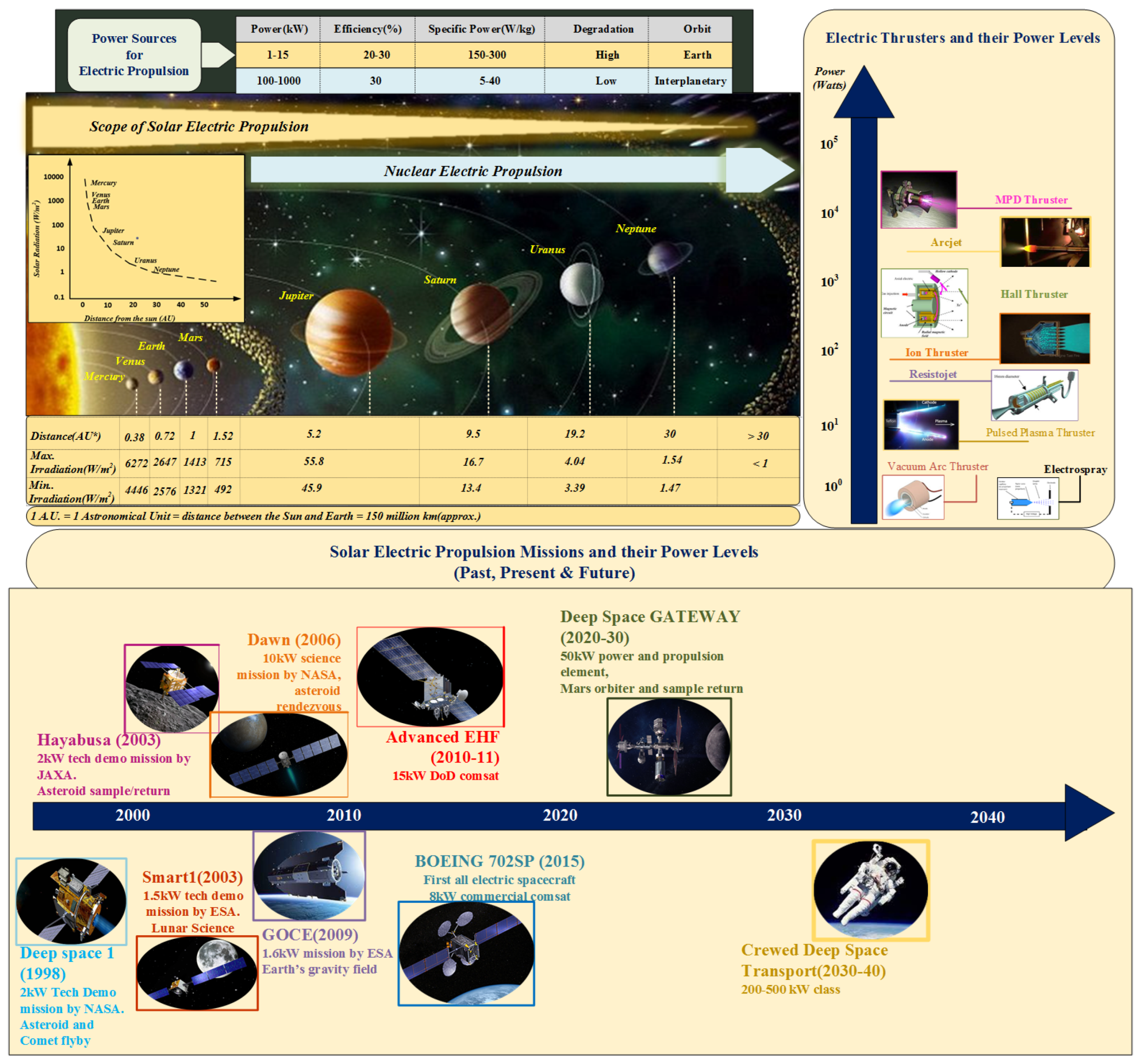

Figure 6.

Summary of various aspects of EP (Power sources for EP, Electric thrusters and their power levels, Evolution of Solar EP).

Figure 6.

Summary of various aspects of EP (Power sources for EP, Electric thrusters and their power levels, Evolution of Solar EP).

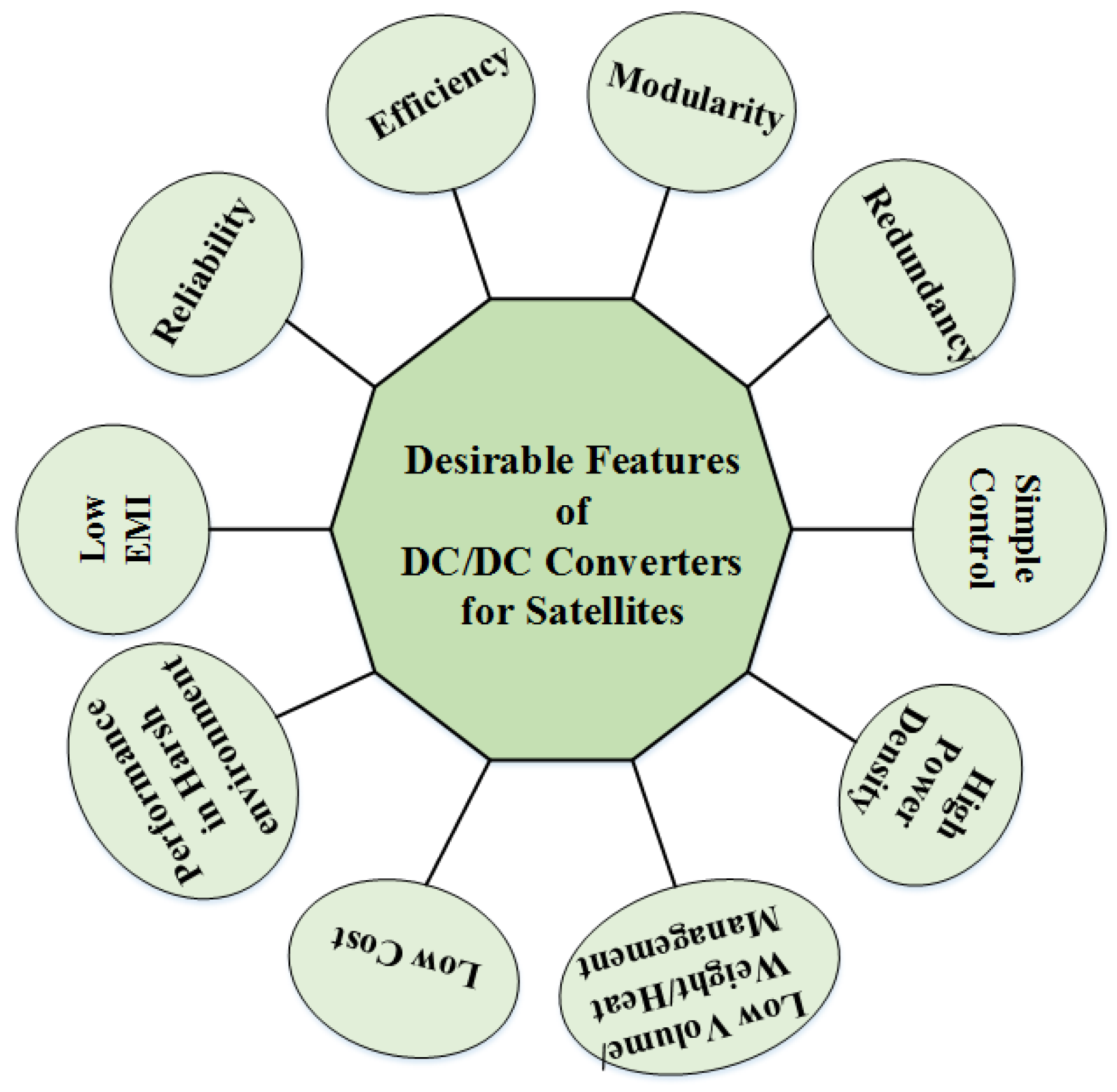

Figure 7.

Desirable Features of DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

Figure 7.

Desirable Features of DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

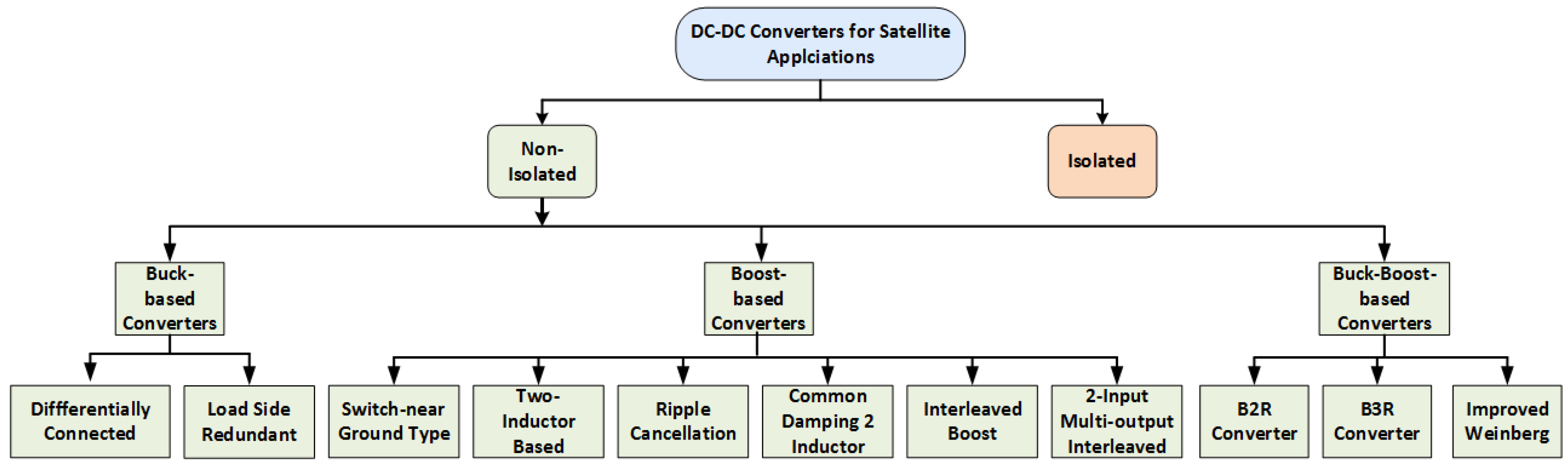

Figure 8.

Classification of non-isolated DC-DC converters for satellite applications.

Figure 8.

Classification of non-isolated DC-DC converters for satellite applications.

Figure 9.

Buck Derived Topologies (a) proposed in [

58] (b) proposed in [

59].

Figure 9.

Buck Derived Topologies (a) proposed in [

58] (b) proposed in [

59].

Figure 10.

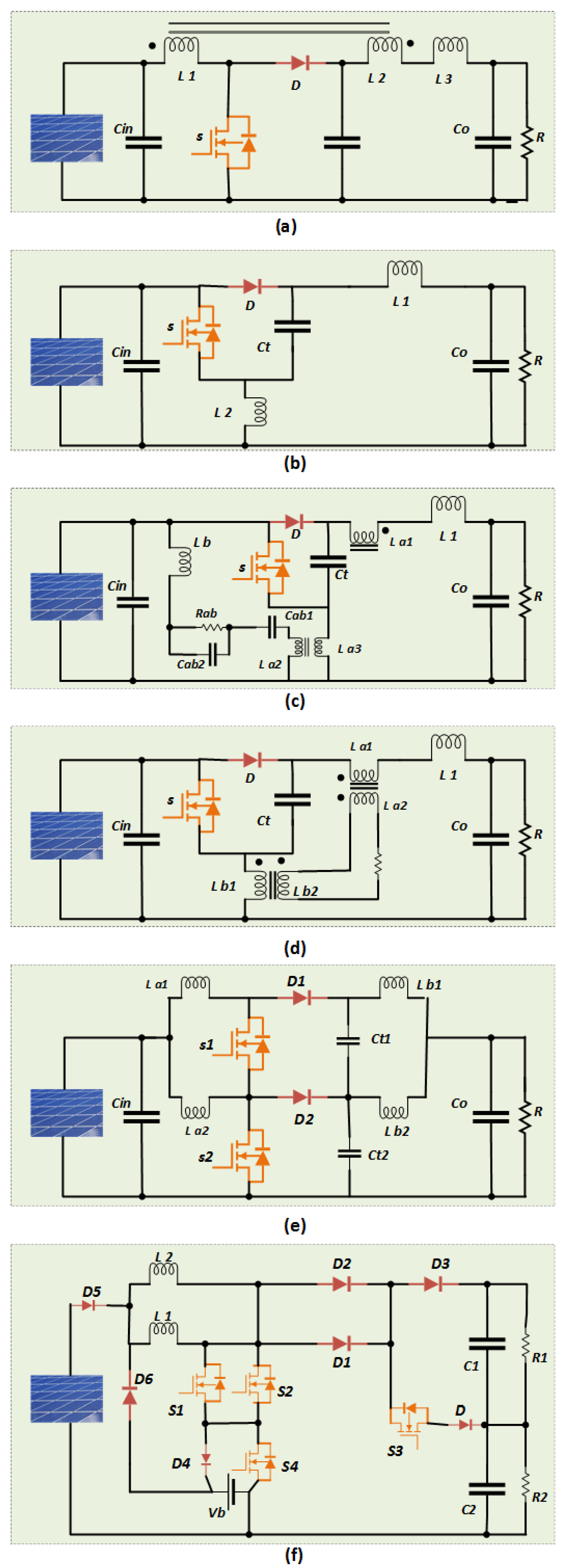

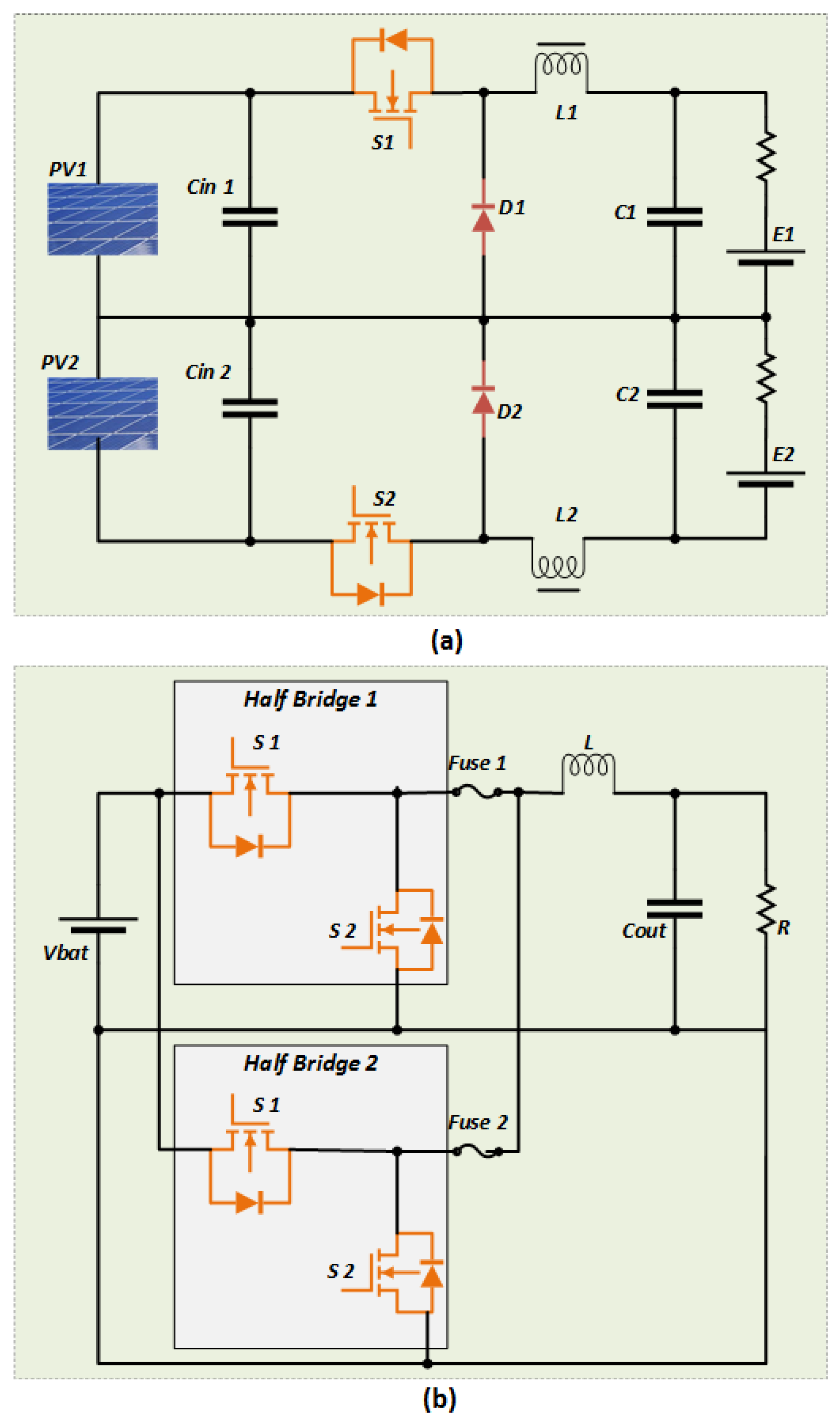

Boost derived topologies (a) boost converter with a near switch ground (b) 2-inductor boost converter (c) ripple cancellation based Boost converter (d) common damping 2-inductor (e) interleaved(f) 2-input multiple output interleaved converter.

Figure 10.

Boost derived topologies (a) boost converter with a near switch ground (b) 2-inductor boost converter (c) ripple cancellation based Boost converter (d) common damping 2-inductor (e) interleaved(f) 2-input multiple output interleaved converter.

Figure 11.

Buck-Boost derived topologies (a) B2R converter(b) B3R converter(c) improved weinberg topology.

Figure 11.

Buck-Boost derived topologies (a) B2R converter(b) B3R converter(c) improved weinberg topology.

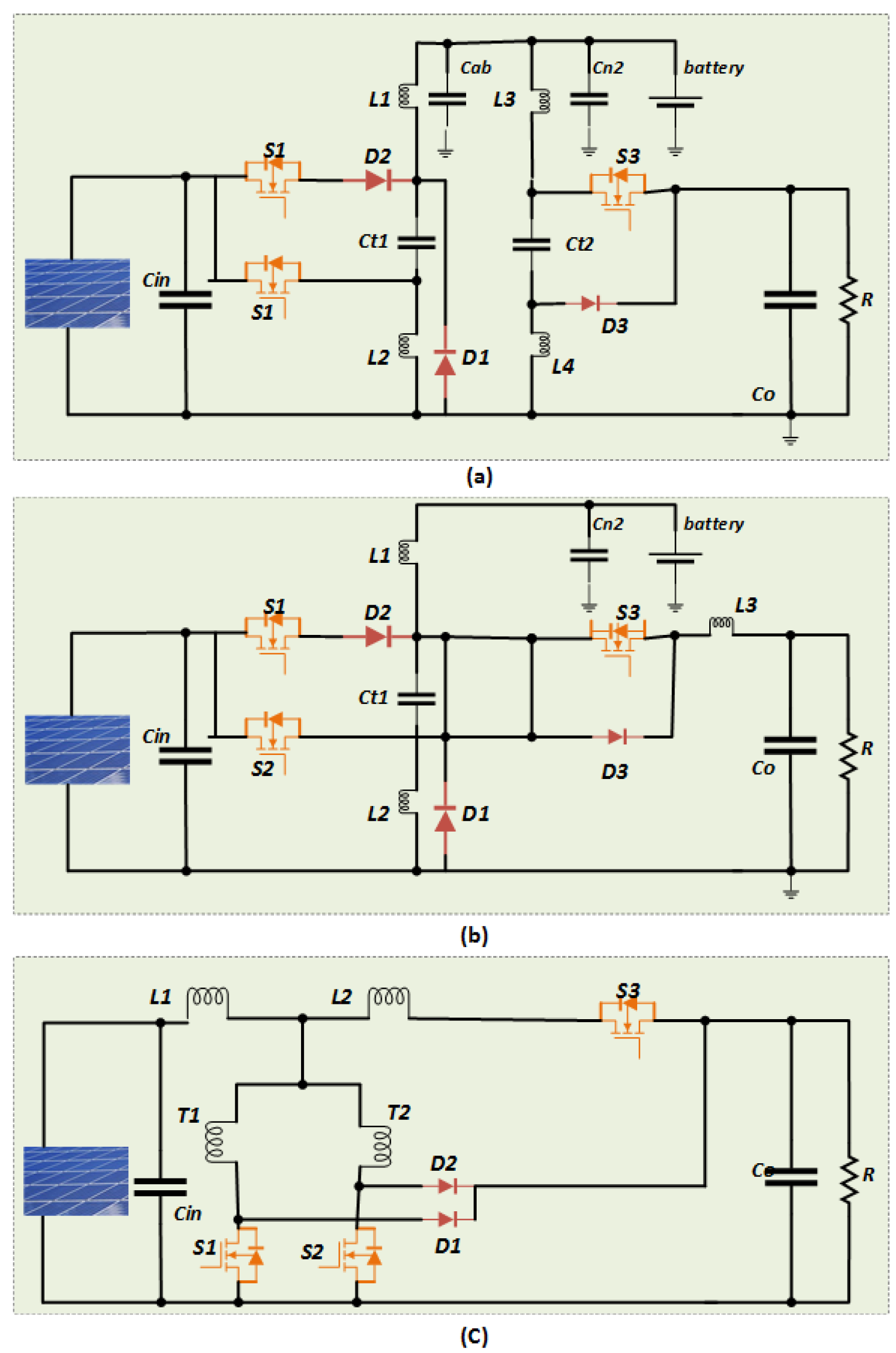

Figure 12.

Classification of Isolated DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

Figure 12.

Classification of Isolated DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

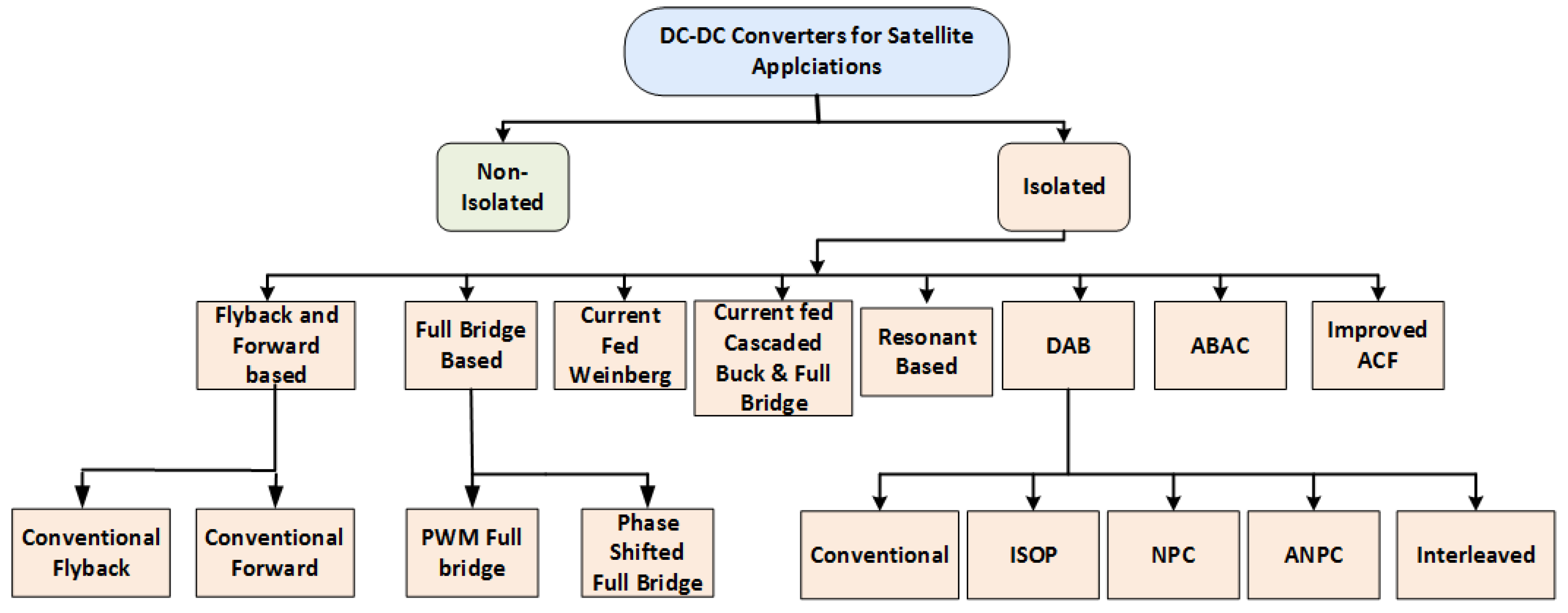

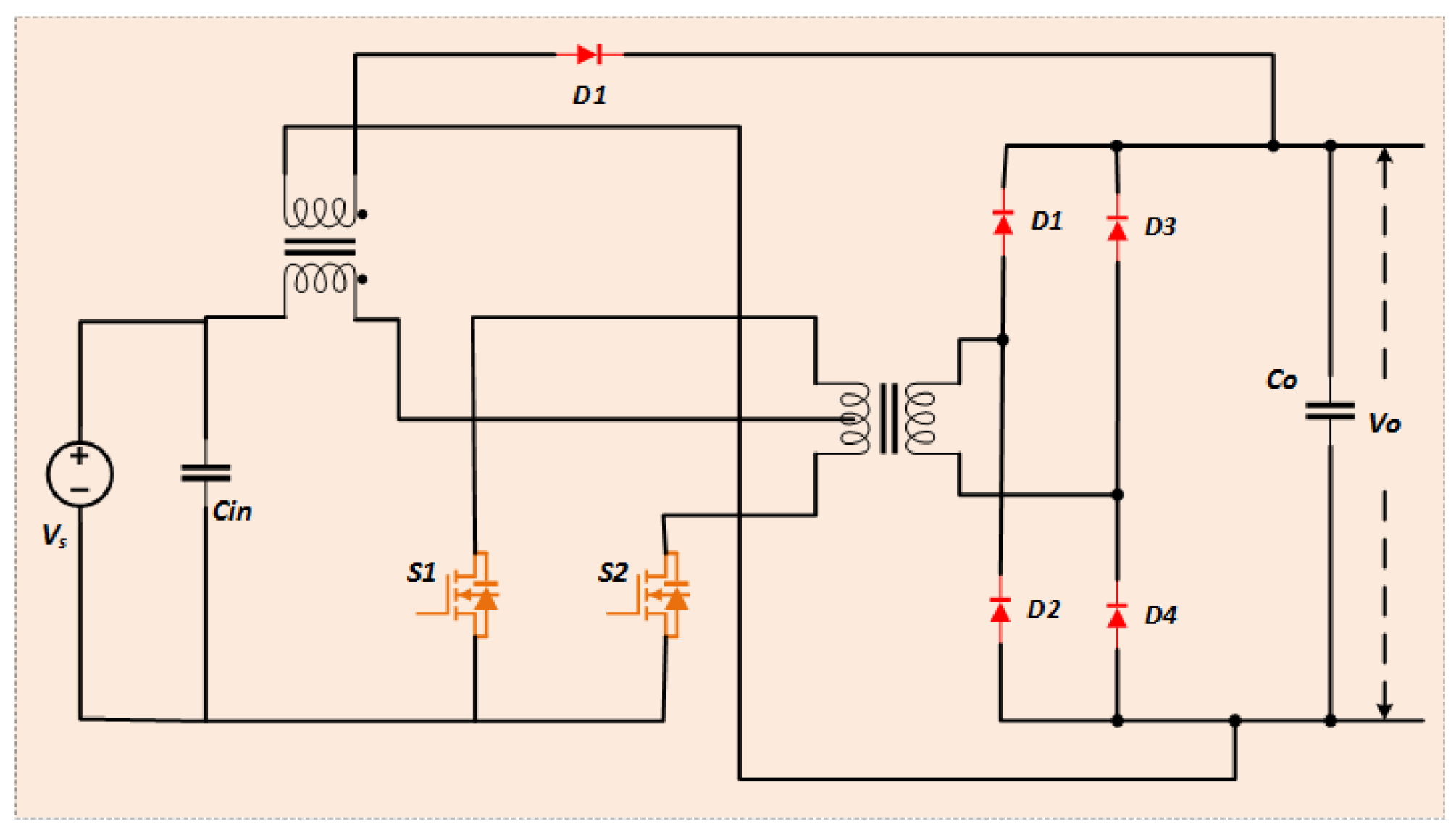

Figure 13.

Full-Bridge Converter.

Figure 13.

Full-Bridge Converter.

Figure 14.

Current-fed Weinberg converter.

Figure 14.

Current-fed Weinberg converter.

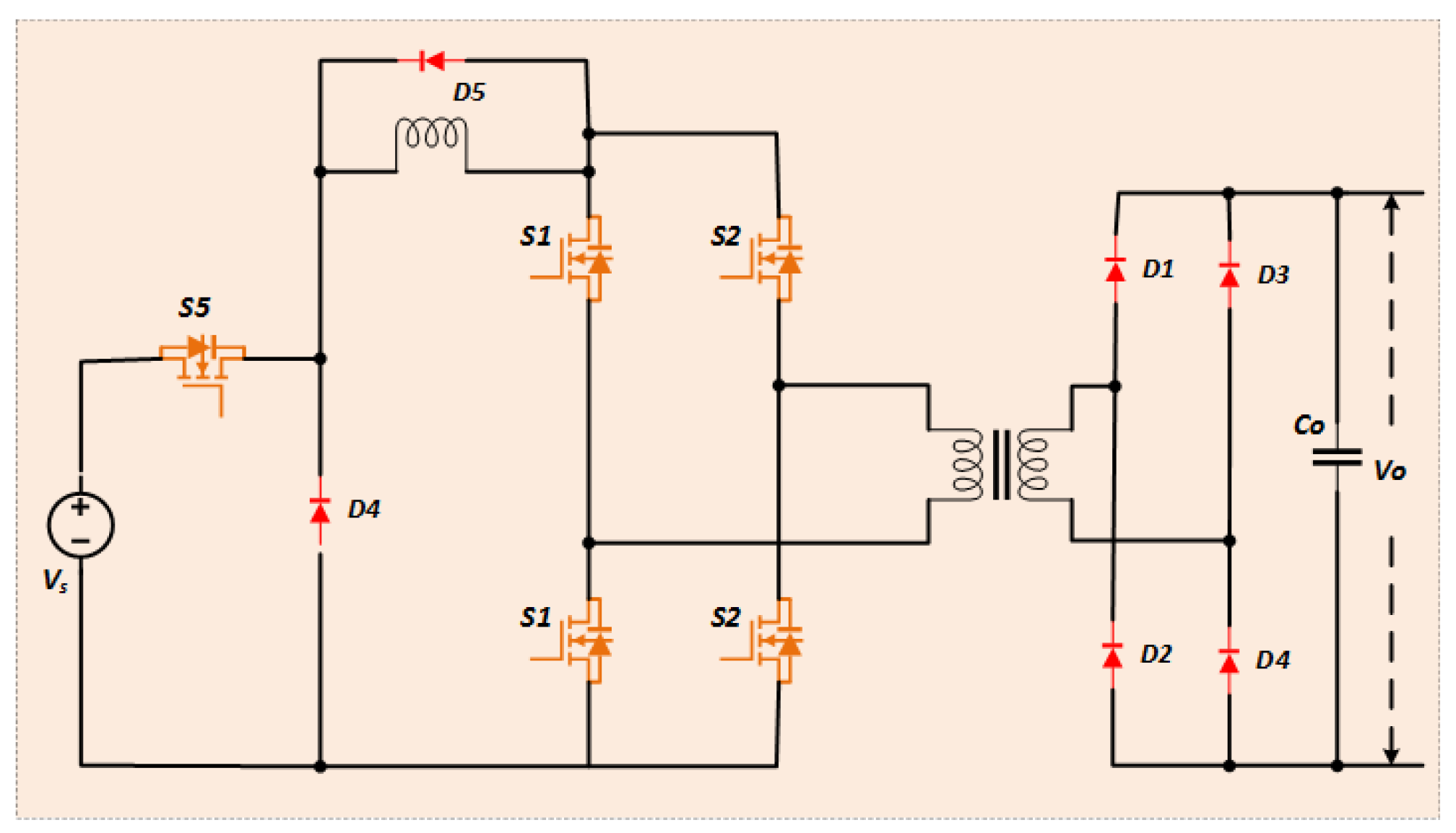

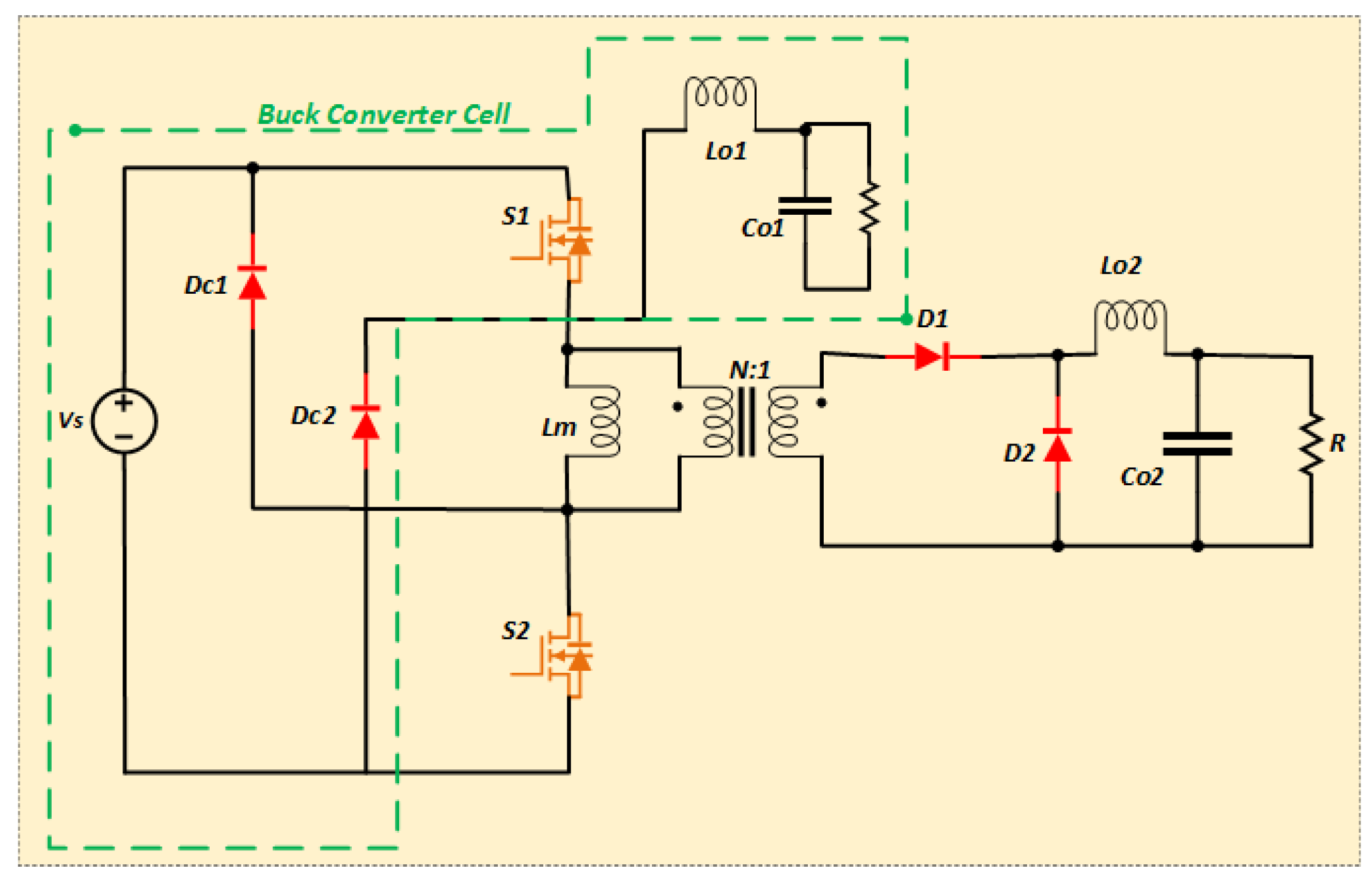

Figure 15.

Current-fed Cascaded Buck and Full Bridge Converter.

Figure 15.

Current-fed Cascaded Buck and Full Bridge Converter.

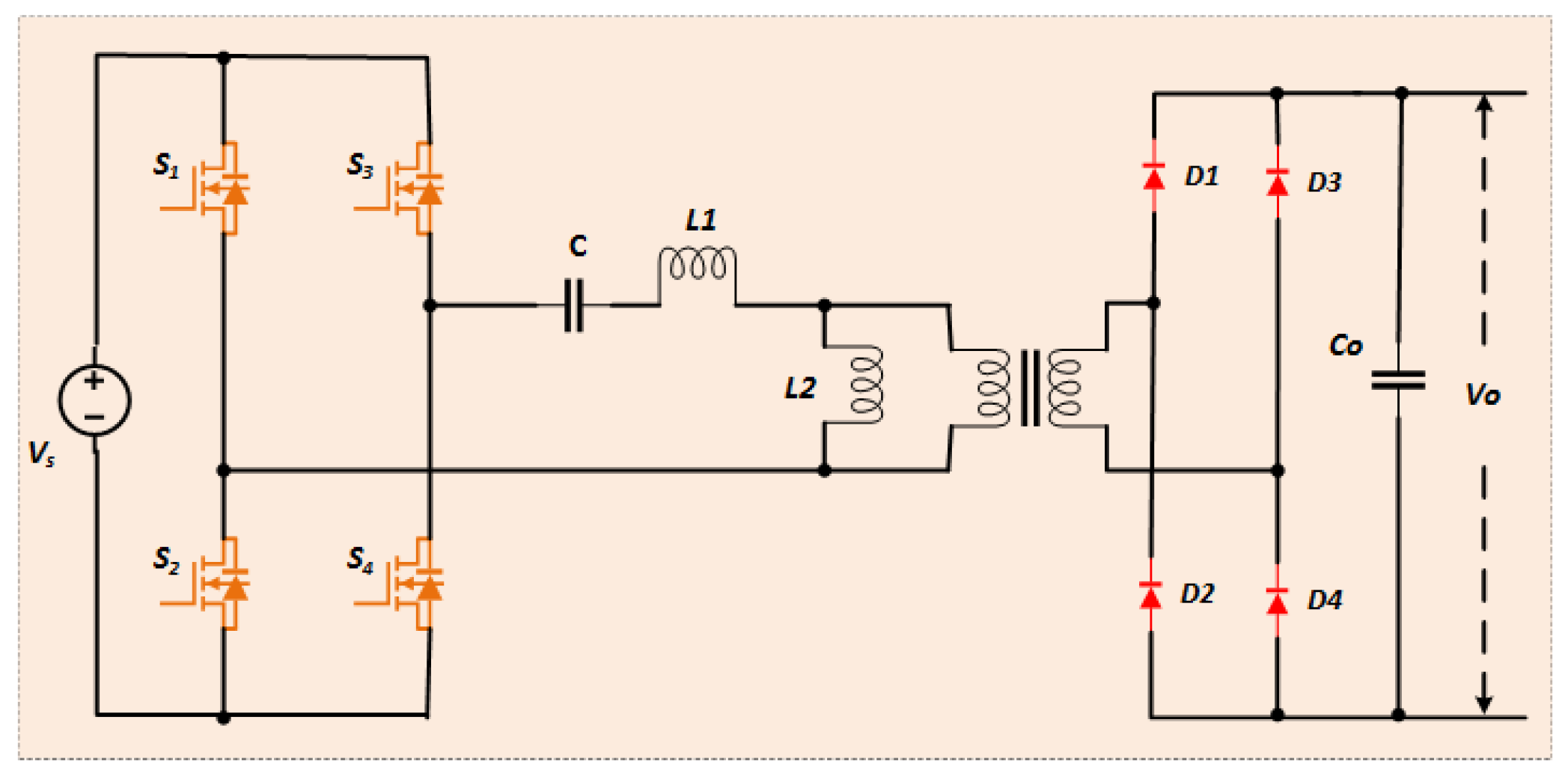

Figure 16.

Resonant LLC Converter.

Figure 16.

Resonant LLC Converter.

Figure 17.

DAB converter topologies (a) conventional (b) ISOP type (c) NPC type.

Figure 17.

DAB converter topologies (a) conventional (b) ISOP type (c) NPC type.

Figure 18.

DAB converter topologies (a) ANPC type (b)Parallel Interleaved type .

Figure 18.

DAB converter topologies (a) ANPC type (b)Parallel Interleaved type .

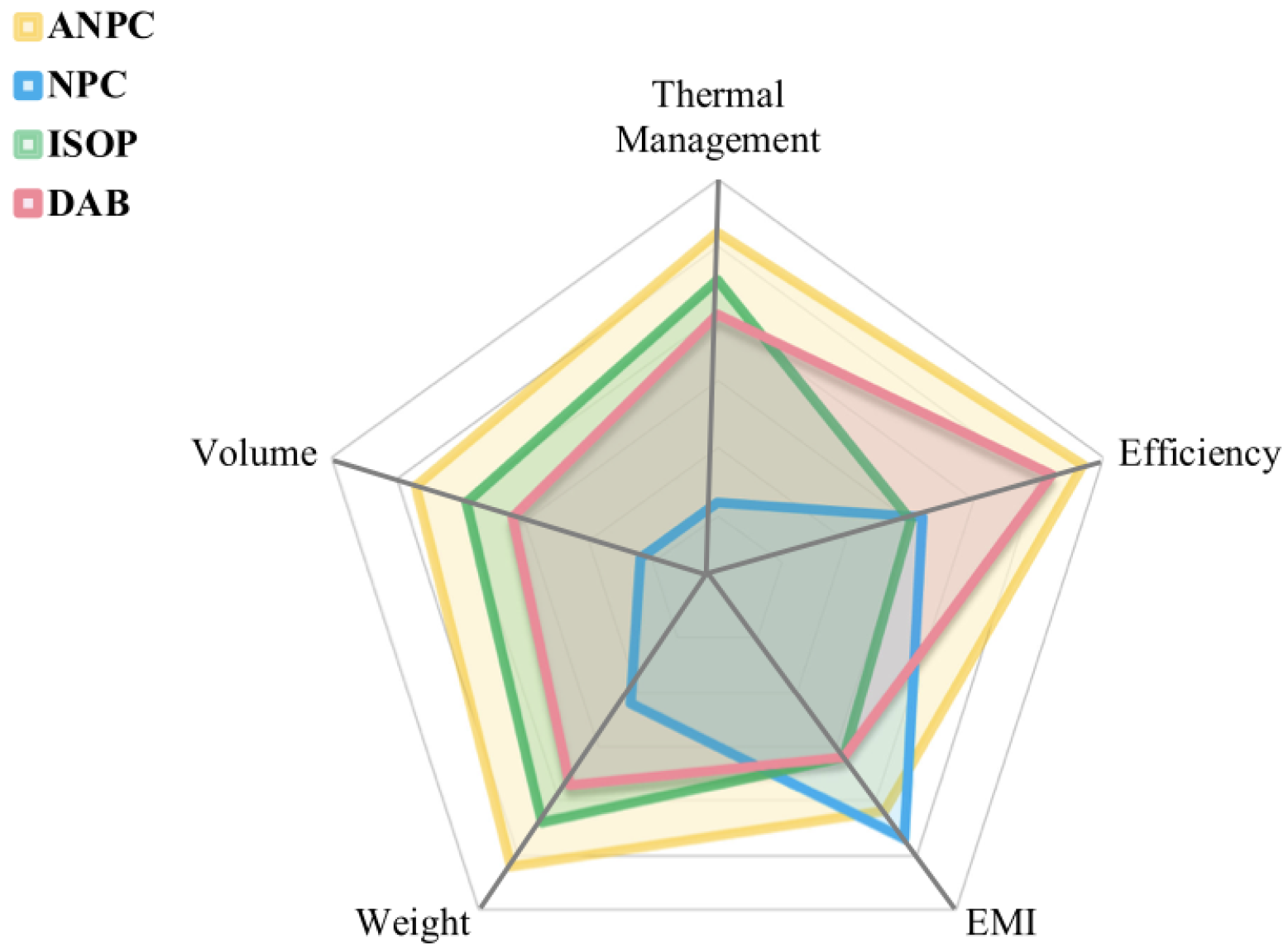

Figure 19.

Comparison of power density, thermal management, volume, efficiency and EMI of various DAB converters[

80].

Figure 19.

Comparison of power density, thermal management, volume, efficiency and EMI of various DAB converters[

80].

Figure 20.

Active bridge active clamp converter.

Figure 20.

Active bridge active clamp converter.

Figure 21.

Improved Active clamp forward converter.

Figure 21.

Improved Active clamp forward converter.

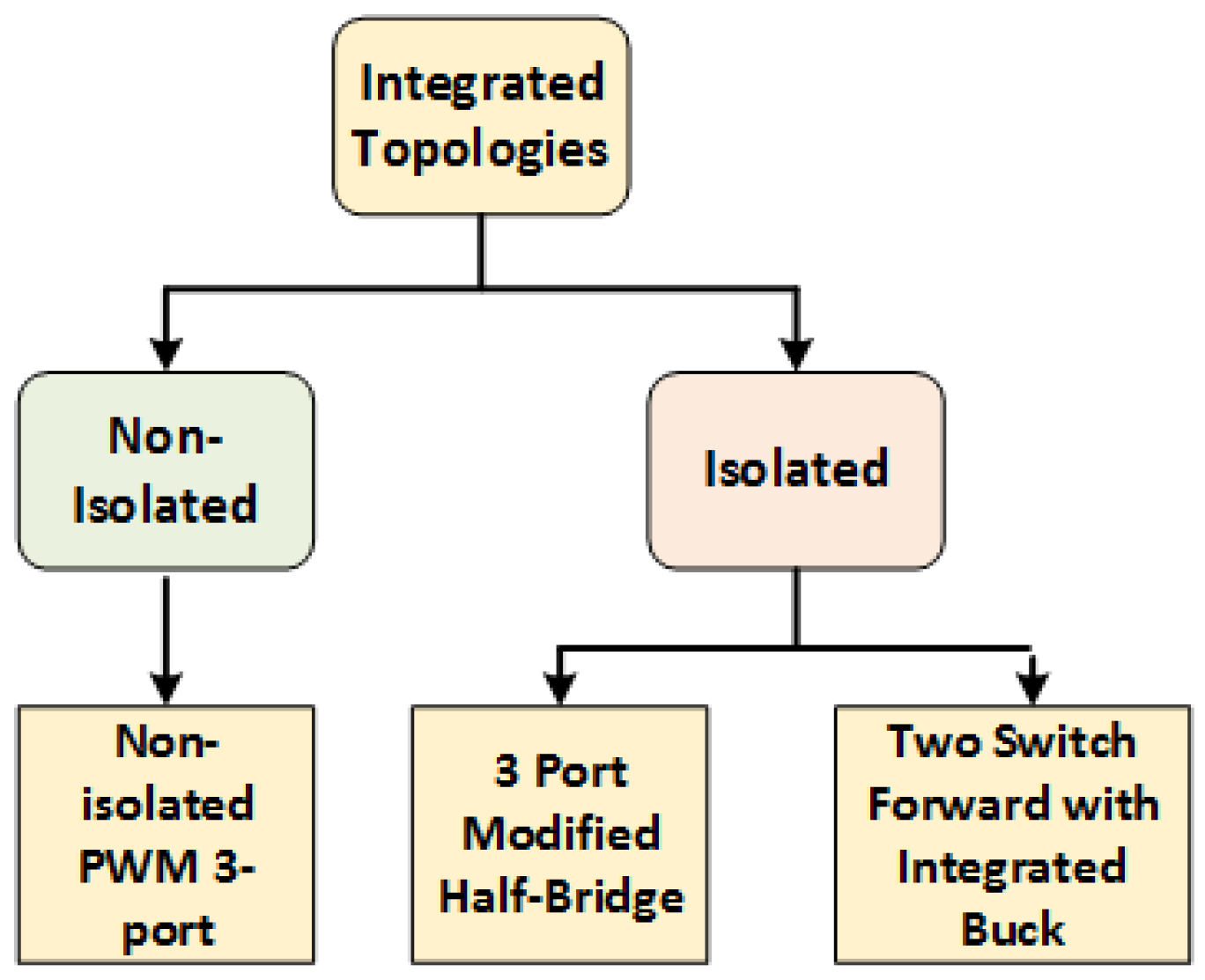

Figure 22.

Classification of Integrated Topologies of DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

Figure 22.

Classification of Integrated Topologies of DC-DC Converters for Satellite Applications.

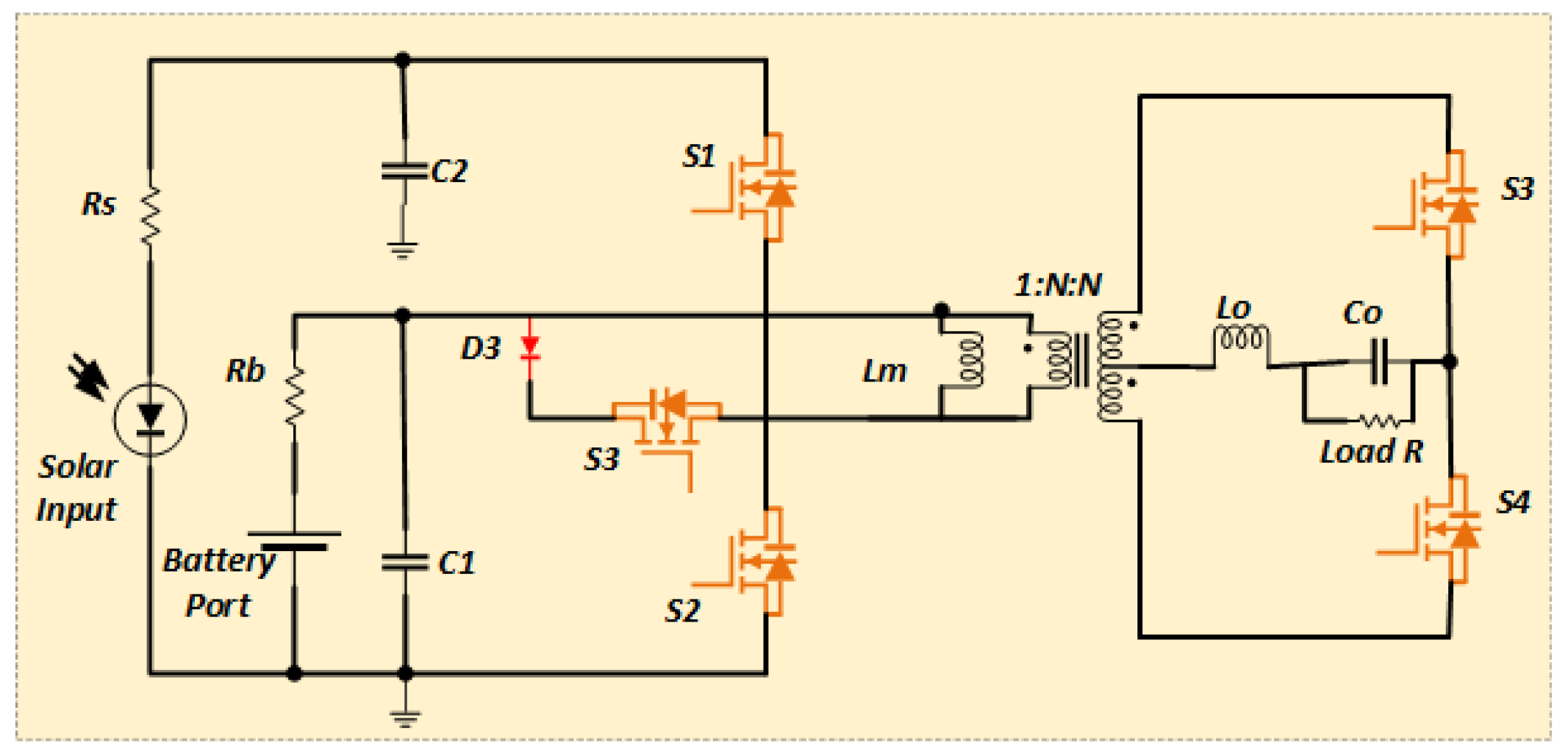

Figure 23.

Three-port modified half bridge converter.

Figure 23.

Three-port modified half bridge converter.

Figure 24.

Non isolated PWM TPC.

Figure 24.

Non isolated PWM TPC.

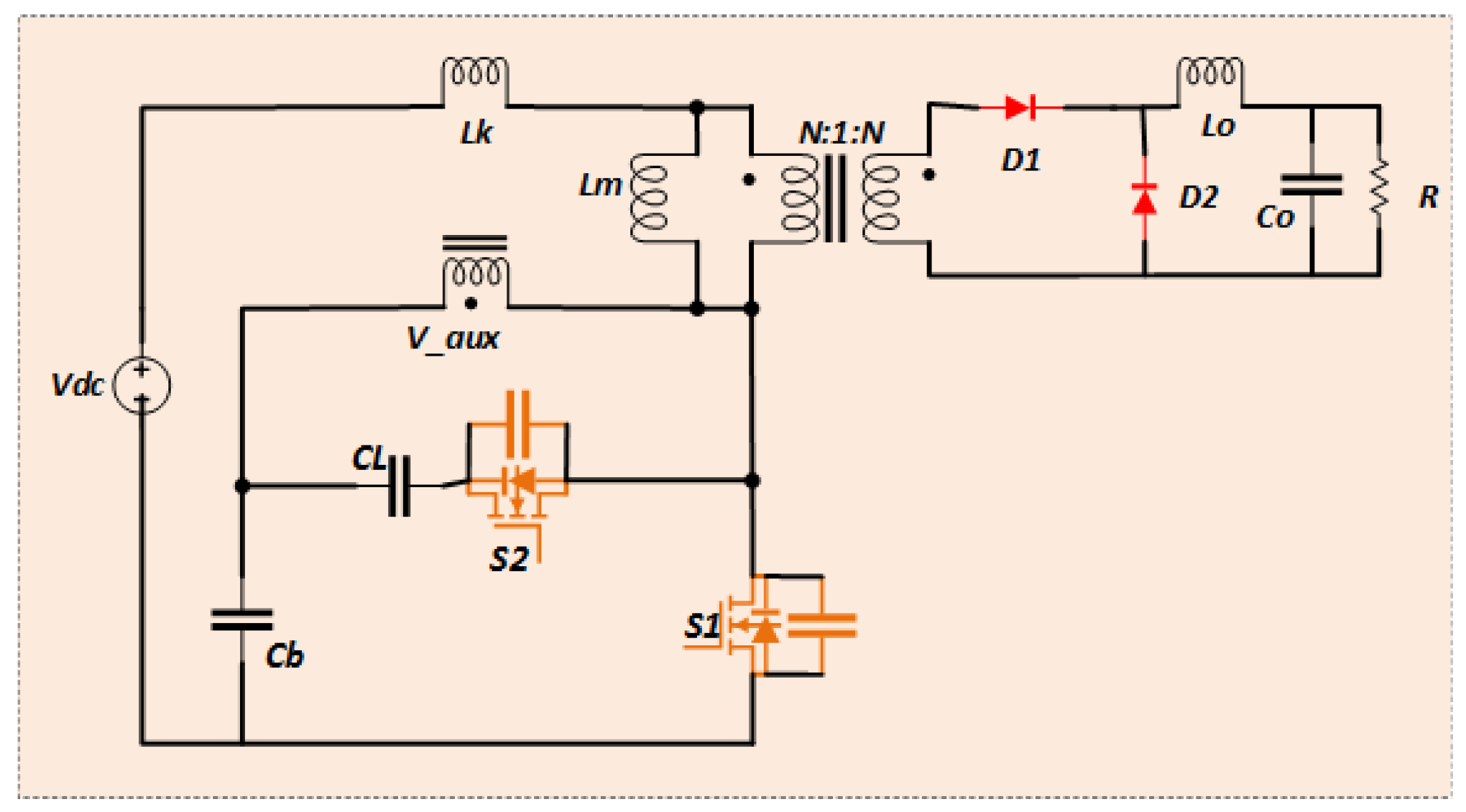

Figure 25.

Two switch forward with integrated Buck converter.

Figure 25.

Two switch forward with integrated Buck converter.

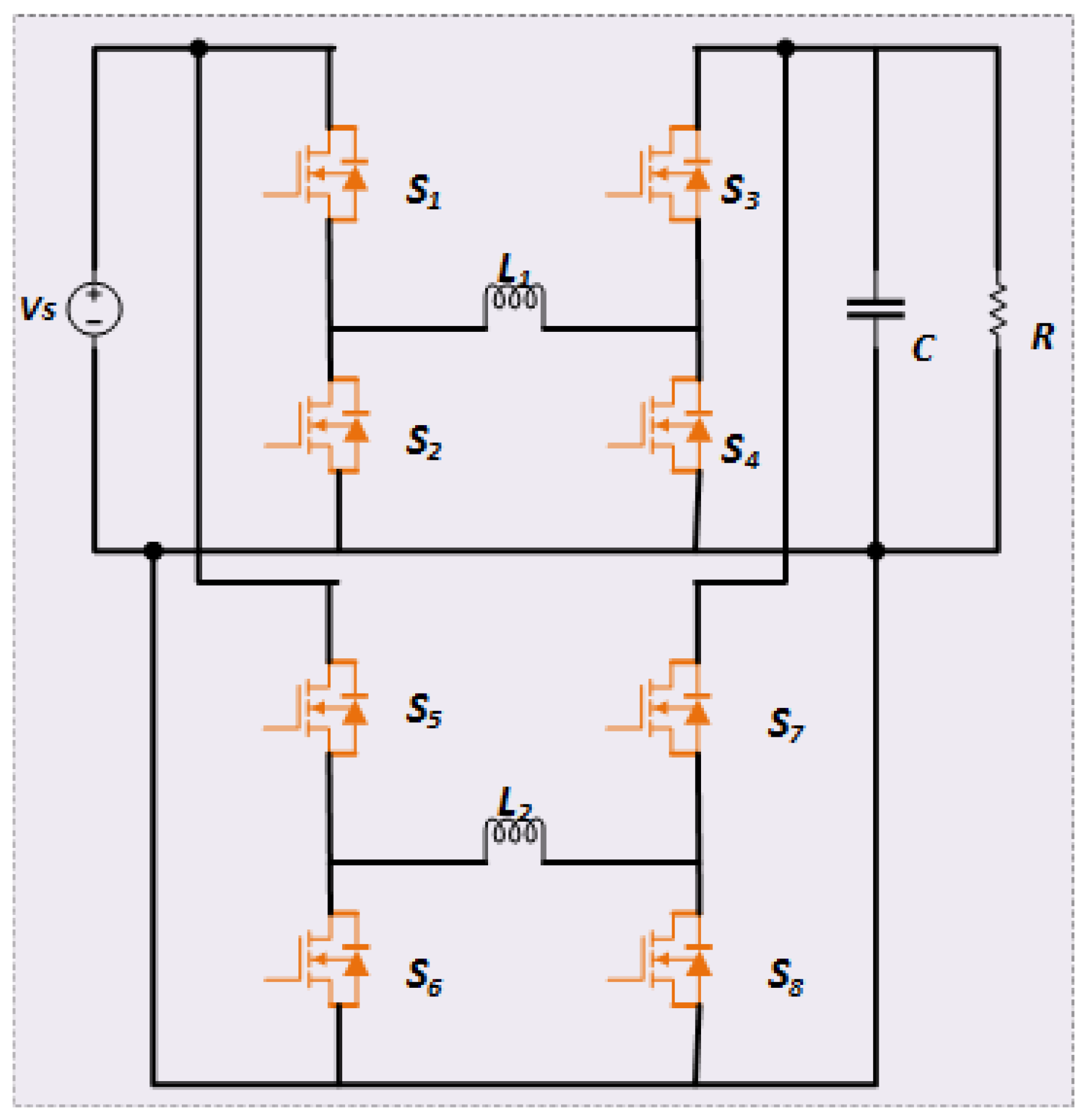

Figure 26.

Four-switch interleaved Buck-Boost converter.

Figure 26.

Four-switch interleaved Buck-Boost converter.

Figure 27.

Various performance indicators of DC-DC converters for satellite applications.

Figure 27.

Various performance indicators of DC-DC converters for satellite applications.

Figure 28.

(a) Generalized structure of Modular Interleaved converter(left) and one module of the converter with Full bridge on primary and Cuk converter on secondary (right) (b) Generalized control strategy of the proposed topology.

Figure 28.

(a) Generalized structure of Modular Interleaved converter(left) and one module of the converter with Full bridge on primary and Cuk converter on secondary (right) (b) Generalized control strategy of the proposed topology.

Figure 29.

Results of simulation for Modular Interleaved Converter based on Cuk topology with two modules (a) Output voltage and current (b) Switching pulses to secondary side switches to modules 1 and 2 (c) Switching pulses to primary side switches to modules 1 and 2 (d) Module Input currents and total input current (e) Module Inductor currents and total current (f) Output voltage for a step change in reference from to (g) Output voltage for a step change in input voltage from to .

Figure 29.

Results of simulation for Modular Interleaved Converter based on Cuk topology with two modules (a) Output voltage and current (b) Switching pulses to secondary side switches to modules 1 and 2 (c) Switching pulses to primary side switches to modules 1 and 2 (d) Module Input currents and total input current (e) Module Inductor currents and total current (f) Output voltage for a step change in reference from to (g) Output voltage for a step change in input voltage from to .

Figure 30.

Comparison of results for single module and three modules based Modular Interleaved Cuk converter (a) Inductor current for single module at switching frequency of (b)Inductor current for single module at switching frequency of (c) Module Inductor currents and total Inductor current for three modules at switching frequency of .

Figure 30.

Comparison of results for single module and three modules based Modular Interleaved Cuk converter (a) Inductor current for single module at switching frequency of (b)Inductor current for single module at switching frequency of (c) Module Inductor currents and total Inductor current for three modules at switching frequency of .

Figure 31.

(a) Variation of Switch and Diode current stresses with number of modules (b) Efficiency at full load Vs Number of modules.

Figure 31.

(a) Variation of Switch and Diode current stresses with number of modules (b) Efficiency at full load Vs Number of modules.

Figure 32.

Various deep space missions with their power and mass.

Figure 32.

Various deep space missions with their power and mass.

Table 1.

Comparison of various applications of high-power DC-DC converters.

Table 1.

Comparison of various applications of high-power DC-DC converters.

| Features |

Satellites |

HVDC |

Fuel |

Electric |

Photovoltaic |

Electric |

| |

|

|

Cell |

Vehicles |

Array |

Aircraft |

| Reliability |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Redundancy |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Modularity |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

| Power Density |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| EMI |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Performance in Harsh |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Environmental Conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Efficiency |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 2.

Comparison of the present paper with recent review papers for Satellite DC-DC converters.

Table 2.

Comparison of the present paper with recent review papers for Satellite DC-DC converters.

| Ref. |

Type of Satellite |

Converter Type |

Application |

Types of |

Research |

Topology |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

gap |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comparison |

highlighted |

presented |

| |

Large |

Small |

Non-Iso |

Iso |

Integrated |

EP |

|

|

|

|

| [32] |

- |

- |

✓ |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

x |

x |

| [33] |

x |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

x |

Voltage regulation Battery regulation Power distribution |

|

x |

x |

| This paper |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

MPPT Battery regulation Voltage regulation Multi-port conversion Electric Propulsion Power distribution |

In terms of switching frequency, number of components and rated power. In terms of performance indicators like reliability, modularity, redundancy, power density, EMI and efficiency. In terms of applications in satellites. In terms of types satellites. |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 3.

Comparison of various non-isolated DC-DC converters.

Table 3.

Comparison of various non-isolated DC-DC converters.

|

Converter |

Reference |

Switching |

Component Count |

Type of |

Power |

uni/bi- |

Main Features |

| |

|

Frequency |

|

|

|

|

satellite |

(W) |

|

|

| |

|

(kHz) |

S |

D |

L |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

Differentially Connected Buck [Figure 9a] |

[33,58] |

400 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

Nano-sat |

30 |

Uni |

Common Mode Noise rejection to reduce leakage current |

|

Load Side Redundant Buck [Figure 9b] |

[33,59] |

- |

4 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Cube-sat |

- |

Uni |

Redundant module for over-current protection |

|

Switch near ground Boost [Figure 10a] |

[32,33] |

130 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

Small sat |

500 |

Uni |

Simple driving circuit direct energy transfer from input and output, high mass |

| |

[61] |

100 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

Small sat |

5000 |

Bi |

Low mass and volume |

|

Two-Inductor based Boost [Figure 10b] |

[32,33,62] |

130 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Small sat |

500 |

uni |

Continuous input and output currents, poor dynamic response. |

|

Boost with ripple cancellation [Figure 10c] |

[32,33,63] |

130 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

Small sat |

500 |

Uni |

Ripple cancellation, high component count |

|

Common damping 2-inductor boost [Figure 10d] |

[32,33] |

130 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

Small sat |

500 |

- |

High bandwidth, high loss in magnetic components |

|

Interleaved Boost [Figure 10e] |

[32,33] |

130 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

Small sat |

500 |

- |

low output current ripple, good transient response, good transient response |

|

Multi Output interleaved [Figure 10f] |

[32,65] |

100 |

4 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

- |

500 |

- |

|

|

B2R Converter [Figure 11a] |

[32,44] |

100 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

- |

450 |

- |

Good voltage regulation |

|

B3R Converter [Figure 11b] |

[32,67] |

- |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

Good voltage regulation, good transient response. |

|

Improved Weinberg Converter [Figure 11c] |

[32,68] |

50 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

- |

- |

Bi |

simple structure, high efficiency, and power density |

Table 4.

Comparison of various isolated DC-DC converters.

Table 4.

Comparison of various isolated DC-DC converters.

|

Converter |

Reference |

Switching |

Component |

Power |

uni/bi- |

Main Features |

| |

|

Frequency |

Count |

|

|

|

(W) |

directional |

|

| |

|

(kHz) |

S |

D |

L |

C |

|

|

|

|

Full-bridge converter [Figure 13] |

[74] |

50 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1000 |

Bi |

wide output voltage, good efficiency, shoot through problems. |

|

Current Fed Weinberg Converter [Figure 14] |

[74] |

50 |

2 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

500 |

Bi |

Shoot through tolerant, high efficiency, wide output voltage, suitable for LV applications, HV stress across switches. |

| |

[76] |

150 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1500 |

Bi |

Fast dynamic response. |

|

Current-Fed Cascaded Buck and Full Bridge Converter [Figure 15] |

[74] |

50 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1000 |

Bi |

Shoot through tolerant, high component count, limitation in operating frequency, lower efficiency |

|

Resonant LLC converter [Figure 16] |

[74] |

>200 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1000 |

Bi |

High efficiency, Lower weight, high switching frequency, complex control circuitry. |

|

Conventional DAB [Figure 17(a)] |

[80] |

- |

8 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

- |

Bi |

Soft switching, Galvanic isolation, simple structure. |

| |

[54] |

100 |

8 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

8400 |

Bi |

|

|

ISOP-DAB [Figure 17b] |

[80] |

16 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

|

- |

Bi |

Low EMI noise, low efficiency. |

|

NPC-DAB [Figure 17c] |

[80] |

- |

12 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

- |

Bi |

Low volume and weight, low EMI noise, low efficiency. |

|

ANPC-DAB [Figure 18a] |

[80] |

- |

16 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

- |

Bi |

High efficiency, good heat management, high power density. |

|

Parallel interleaved DAB [Figure 18b] |

[80] |

50 |

8 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

250 |

Bi |

|

|

ABAC Converter [Figure 20] |

[54,77] |

100 |

8 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

8400 |

Uni |

High efficiency, high power density. |

|

ACF [Figure 21] |

[86] |

300 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

100 |

Uni |

Reliable, light weight, low EMI noise, high power density. |

Table 5.

Comparison of various integrated DC-DC converters.

Table 5.

Comparison of various integrated DC-DC converters.

|

Converter |

Reference |

Switching |

Component |

Power |

Iso/non-iso |

Main Features |

| |

|

Frequency |

Count |

|

|

|

(W) |

directional |

|

| |

|

(kHz) |

S |

D |

L |

C |

|

|

|

|

Three-Port Modified Half Bridge Converter [Figure 23] |

[37] |

- |

5 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

200 |

Isolated |

Soft switching during turn-on, complex control technique. |

|

Non-isolated PWM-Three-Port Converter [Figure 24] |

[36] |

100 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

240 |

Non-isolated |

Simple circuit, reduced size. |

|

Two Switch Forward with Integrated Buck Converter [Figure 25] |

[17] |

100 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

600 |

Isolated |

Low mass and volume, ZVS switching, improved efficiency. |

Table 6.

Comparison of Various DC-DC Converters for EP in Satellites.

Table 6.

Comparison of Various DC-DC Converters for EP in Satellites.

|

Converter |

Reference |

Switching |

Component |

Power |

Uni/Bi |

Main Features |

| |

|

Frequency |

Count |

|

|

|

(W) |

directional |

|

| |

|

(kHz) |

S |

D |

L |

C |

|

|

|

|

Resonant LLC [Figure 16] |

[104] |

>200 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1000 |

Bi |

High efficiency, Lower weight, high switching frequency, complex control circuitry |

|

4 Parallel Converters [Figure 24] |

[105] |

50 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6000 |

- |

High efficiency over wide output range,low component count, parallel or serial switching of converters to obtain multiple output conditions |

|

DAB [Figure 24] |

[106,107] |

- |

8 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

5000 |

Bi |

Soft switching, Galvanic isolation, simple structure. |

|

DAB with Combined dual modulation [Figure 24] |

[108] |

- |

8 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1000-5000 |

Bi |

Decreased EMI, a large output voltage range, high efficiency, and power density. |

|

4switch interleaved Buck-Boost + LLC resonant [Figure 26] |

[109] |

- |

8 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1200 |

Bi |

Soft switching, low size of Inductor, high power density and efficiency. |

Table 7.

Comparison of various non-isolated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

Table 7.

Comparison of various non-isolated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

|

Converter |

References |

Figure |

Reliability |

Redundancy |

Modularity |

Power Density |

Efficiency |

|

Differentially connected Buck |

[33,58] |

Figure 9a |

Medium |

Yes |

No |

High |

97 |

|

Load side redundant Buck |

[33,59] |

Figure 9b |

High |

Yes |

No |

- |

- |

|

Switch near ground Buck |

[32,33] |

Figure 10a |

High |

No |

No |

- |

96 |

|

Two inductor based Boost |

[32,33,62] |

Figure 10b |

High |

No |

No |

- |

>96 |

|

Boost with ripple cancellation |

[32,33,63] |

Figure 10c |

Medium |

No |

No |

High |

>96 |

|

Common damping 2-inductor Boost |

[32,33] |

Figure 10d |

High |

No |

No |

- |

>96 |

|

Interleaved Boost |

[32,33] |

Figure 10e |

High |

Yes |

yes |

- |

>96 |

|

Multi output interleaved Boost |

[32,65] |

Figure 10f |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

96 |

|

B2R Converter |

[32,44] |

Figure 11a |

Medium |

No |

No |

- |

96 |

|

B3R Converter |

[32,67] |

Figure 11b |

Medium |

No |

No |

- |

High |

|

Improved Weinberg converter |

[32,68] |

Figure 11c |

Medium |

No |

No |

- |

High |

Table 8.

Comparison of various isolated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

Table 8.

Comparison of various isolated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

|

Converter |

References |

Figure |

Reliability |

Redundancy |

Modularity |

Power Density |

Efficiency |

|

Full bridge converter |

[74] |

Figure 13 |

Medium |

No |

No |

Medium |

95 |

|

Current fed Weinberg converter |

[74] |

Figure 14 |

High |

No |

No |

Medium |

95 |

|

Current fed cascaded buck and full bridge converter |

[74] |

Figure 15 |

Medium |

No |

No |

Medium |

90-95 |

|

Resonant LLC converter |

[74] |

Figure 16 |

Medium |

No |

No |

Medium |

95-98 |

|

Conventional DAB |

[80] |

Figure 17a |

High |

No |

No |

Medium |

High |

|

ISOP-DAB |

[80] |

Figure 17b |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

High |

|

NPC-DAB |

[80] |

Figure 17c |

Low |

No |

No |

Low |

Low |

|

ANPC-DAB |

[80] |

Figure 18a |

Low |

No |

No |

High |

High |

|

Parallel interleaved DAB |

[80] |

Figure 18b |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

- |

|

ABAC converter |

[54,77] |

Figure 20 |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

High |

|

ACF converter |

[86] |

Figure 21 |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

90-95 |

Table 9.

Comparison of various integrated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

Table 9.

Comparison of various integrated DC-DC converters in terms of performance indicators.

|

Converter |

References |

Figure |

Reliability |

Redundancy |

Modularity |

Power Density |

Efficiency |

|

Three port modified half bridge converter |

[37] |

Figure 23 |

Low |

No |

No |

Low |

High |

|

Non-isolated PWM three port converter |

[36] |

Figure 24 |

Medium |

No |

No |

Medium |

97.3 |

|

Two switch Forward with integrated Buck converter |

[17] |

Figure 25 |

High |

No |

No |

High |

95 |

Table 10.

Comparison of various high-power DC-DC converters in PPU for EP.

Table 10.

Comparison of various high-power DC-DC converters in PPU for EP.

|

Converter |

Ref. |

Figure |

Type of |

Reliability |

Redundancy |

Modularity |

Power |

Efficiency |

| |

|

|

thruster |

|

|

|

Density |

|

|

Resonant LLC |

[104] |

Figure 16 |

Hall thruster |

Medium |

No |

No |

High |

> 95 |

|

4 parallel converters |

[105] |

- |

Hall thruster |

High |

No |

Yes |

High |

96.1 |

|

DAB |

[106,107] |

Figure 24 |

Ion thruster |

Medium |

No |

No |

High |

High |

|

DAB with combined dual modulation |

[108] |

Figure 24 |

- |

High |

No |

No |

High |

- |

|

4switch interleaved Buck-Boost + LLC resonant |

[109] |

Figure 26 |

Ion thruster |

High |

No |

Yes |

High |

High |

Table 11.

Comparison of the selected topologies based on their application in satellites and type of satellite.

Table 11.

Comparison of the selected topologies based on their application in satellites and type of satellite.

|

Application |

Figure |

Reference |

Large |

Small |

Mini |

Micro |

Nano |

Pico |

Femto |

| MPPT |

Figure 9a |

[33,58] |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Figure 9b |

[33,59] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10a |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10b |

[32,33,62] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10c |

[32,33,63] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10d |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10e |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10f |

[32,65] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11a |

[32,44] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11b |

[32,67] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11c |

[32,68] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Battery Regulator |

Figure 10f |

[32,65] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11a |

[32,44] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11b |

[32,67] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11c |

[32,68] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Voltage Regulation |

Figure 9a |

[33,58] |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Figure 9b |

[33,59] |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Figure 10a |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10b |

[32,33,62] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10c |

[32,33,63] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10d |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10e |

[32,33] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10f |

[32,65] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11a |

[32,44] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11b |

[32,67] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 11c |

[32,68] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Multi-port Conversion |

Figure 23 |

[37] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Figure 24 |

[36] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Figure 25 |

[17] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Electric Propulsion |

Figure 16 |

[74] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 17a |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 26 |

[109] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Power distribution |

Figure 13 |

[74] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 14 |

[74] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 15 |

[74] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 16 |

[74] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 17a |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 17b |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 17c |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 18a |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 18b |

[80] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 20 |

[54,77] |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 21 |

[86] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Table 12.

Design Parameters for Simulation Model.

Table 12.

Design Parameters for Simulation Model.

| Parameter |

Overall |

Module 1 |

Module 2 |

| Rated Power |

|

|

|

| Input Voltage |

|

|

|

| Output Voltage |

|

|

|

| Switching frequency |

|

|

|

| Load resistance |

|

|

|

| Output Capacitor |

|

|

|

| Cuk Capacitor |

|

|

|

| Output Inductor |

|

|

|

Table 13.

Research Gaps in Various Space Applications(Contd.)

Table 13.

Research Gaps in Various Space Applications(Contd.)

|

Area of research |

Gaps |

| Design and development of DC-DC converters |

Improving fault-tolerant capability without increasing size. Avoiding common mode current for fail-safe operation. Improving power density Reducing ripple content of output current to improve battery health Improving reliability by avoiding single element failure Solving unshared ground issues in multi-port converters Increased power level for converters() High output voltage range () High voltage conversion ratio Improving efficiency and power density. Modular converter design Improved design of input and output EMI filters |

| Adoption of Solar EP / Nuclear EP |

Improving specific impulse and durability of high thrust systems. Improving efficiency and reliability of low thrust systems. Increasing power levels(). Better understanding of reliability and lifetime of propulsion systems at higher power levels. Reduced specific mass. |

| Deep Space Exploration |

Developing electronic components capable of withstanding high radiations and temperatures in deep space. Development of high-power propulsion systems. Development of new materials and technologies to enhance efficiency and durability of solar panels in deep space. |

| Electronic Components for space applications |

Development of Silicon Carbide and Gallium Nitride semiconductors. Development of High current/high energy density capacitors. Development of Low loss magnetic materials that can withstand high temperatures. |

| Solar Based Power Satellites |

Development of Low cost solar cells with large lifetime. Research on Perovskite solar cells. Development of large-scale microwave/lased based wireless energy transfer methods. Development of Kilometer-scale space solar power plant. |