Simple equations can be derived to link AC quantities with the DC ones for rectifier and inverter operations. In case CTs are used as DC/DC converters, the same equations can be cascaded to provide valid estimations.

The easiest relationship that can be formalized is based on a dynamic transformation ratio

defined as:

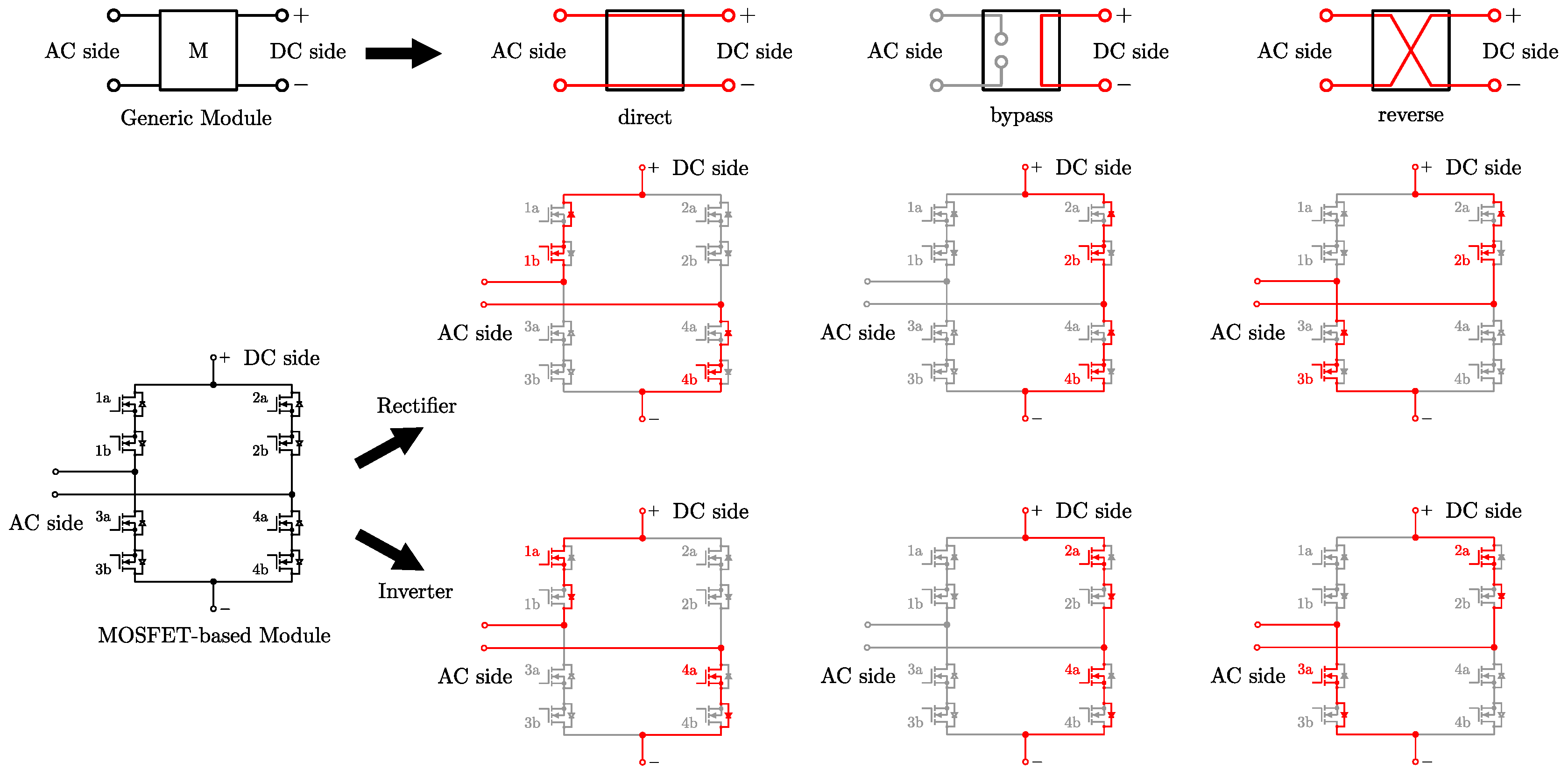

where

is a function of time (typically a combination of square waveforms) that depends on the specific state of the

h-th module. Namely, it can assume the values

for reverse, bypass, direct states, respectively, assumed at the specific time instant

t based on

Table 1.

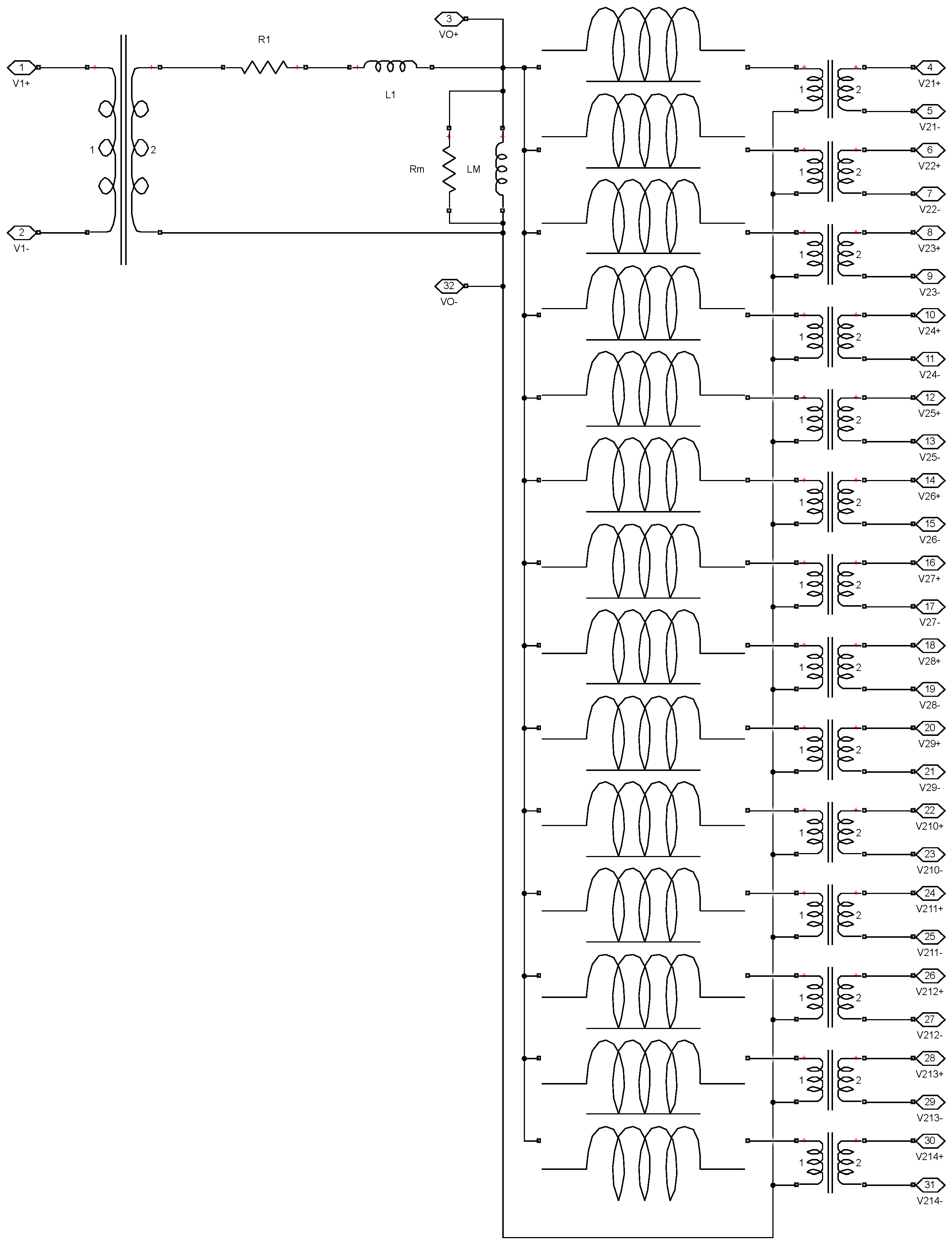

N is the number of turns of each secondary winding (assuming all of them are equal) connected to the

h-th module while

is the total number of primary turns. Hence, the primary voltage

and the DC voltage

on each phase

i can be linked as follows

In three phase systems, the waveform of the overall DC voltage

can be computed as:

Namely, the combination of equations (

2), (

3) and (

4) provides an indication of the harmonic content in the involved quantities, assuming that 1) the supply side is a pure sine-wave or a perfect constant, 2) the switching operations are ideal and 3) all the reactive elements in the system are negligible. It can be noted that this approach has many limitations. The most important one is that

is a piece-wise function and it may not be easy to manage when the number of modules is very large. From this observation, a simpler relationship between AC rms voltage and DC mean value can be formalized. To this aim, a rectifier operation of the CTs is assumed; thus, the starting point is the expression of the DC voltage

associated to phase 1 (i.e.,

) through a piece-wise function dependent on the threshold levels

,

and

:

where

with

f the fundamental frequency of

(i.e., 50 or 60

),

is the rms value of the secondary voltage of the multi-winding transformer, which can be computed from the rms value of the primary voltage

and the constant turn ratio:

Focusing on

(which are the voltages applied on the terminals of the primary windings), they can be shifted and amplified with respect to the AC grid voltages

depending on the connection adopted at the primary terminals of the transformer (i.e., star, delta or zig-zag). Hence, no relationship involving

are investigated for simplicity in this paper. Considering the same system of equations, it is possible to write a relationship between

and the mean value of DC voltage on each module, each phase and the whole DC bus as well. Indeed, starting from a piece-wise integration like the following one:

it follows that:

Reminding the expression that links AC and DC voltages in ideal single-phase thyristor bridges [

25]:

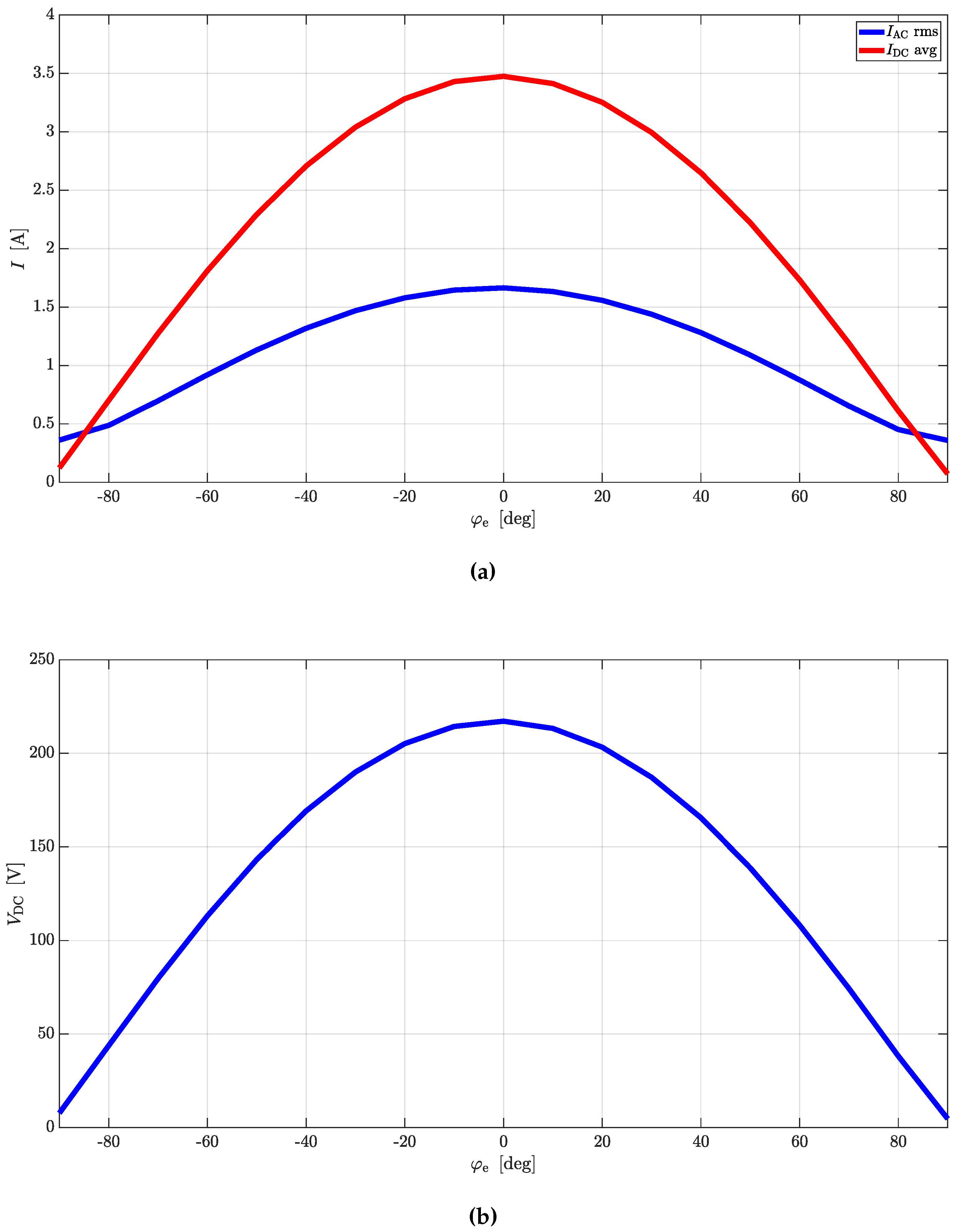

It can be noted that every module in the CT works exactly in the same way:

can be interpreted as the firing angle of an equivalent thyristor bridge, whereas the DC voltage is regulated through

. Coming back to equation (

8), the overall mean DC voltage of the device can be written as:

with:

Equation (

10) can be reversed to find

as a function of

,

,

and the

values. This relationship holds in absence of any loss:

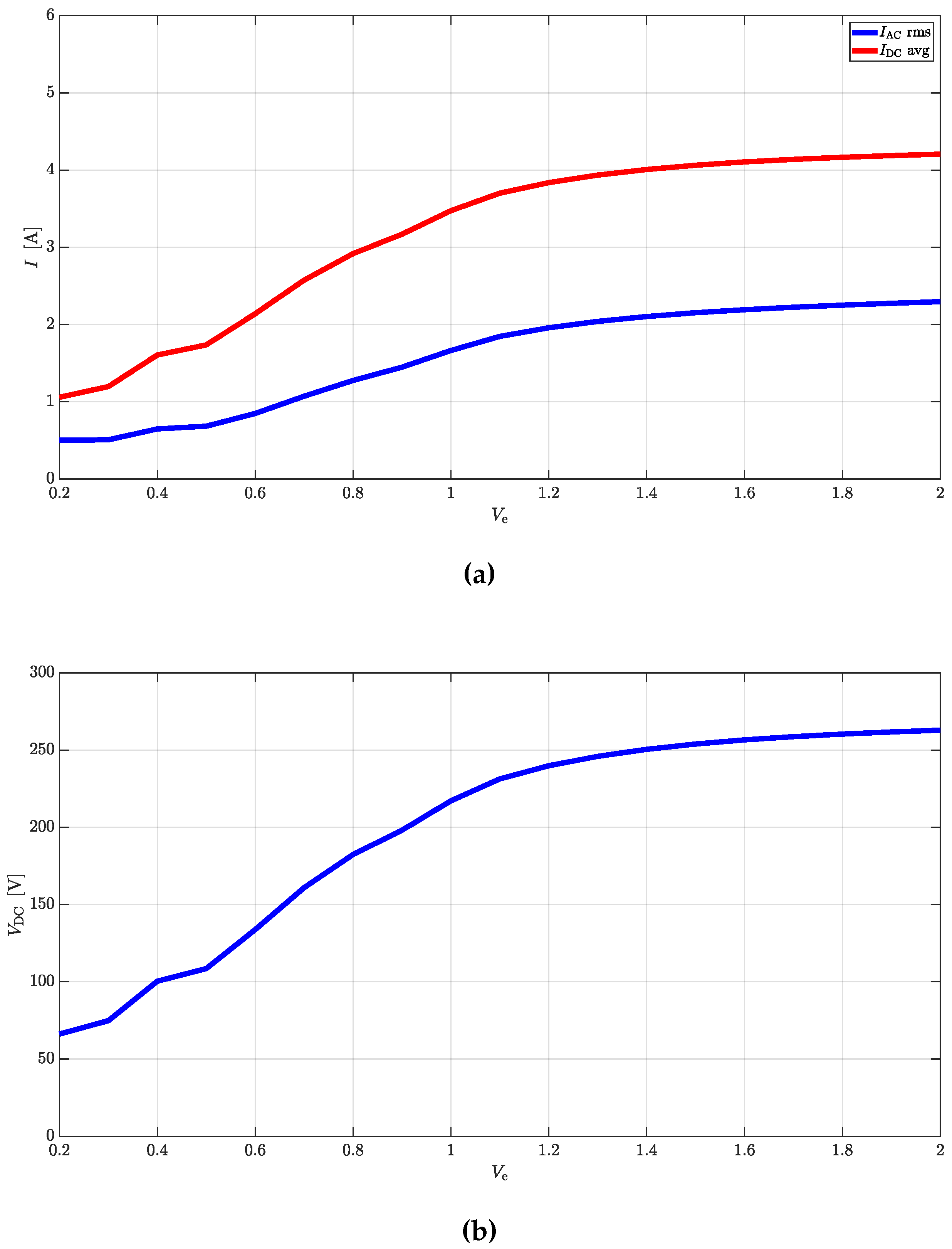

Voltage drops on the adopted switches can be included as well to provide more realistic estimations of

and

. For example, assuming that MOSFETs are used:

where

is the on resistance of the mosfets,

is the forward voltage of the diodes and

is the average value of the DC current. The values of

and

can be extrapolated from the datasheet of the selected switches. Similarly, the relationship linking

to

becomes:

It must be said that more accurate evaluations can be performed if the time dependent current is considered instead of its mean value. In that case,

and

should be updated based on the current flowing on each switch and its corresponding temperature. Instead, equations (

13) and (

14) exploit an average approach: at least two MOSFETs and two freewheeling diodes are always conducting in the whole period of AC quantities. However, the results are satisfactory and very simple to compute. In principle, losses related to the transformer can be included in the equation as well. The authors preferred to manage them separately and to deal with expressions involving power electronic components only.

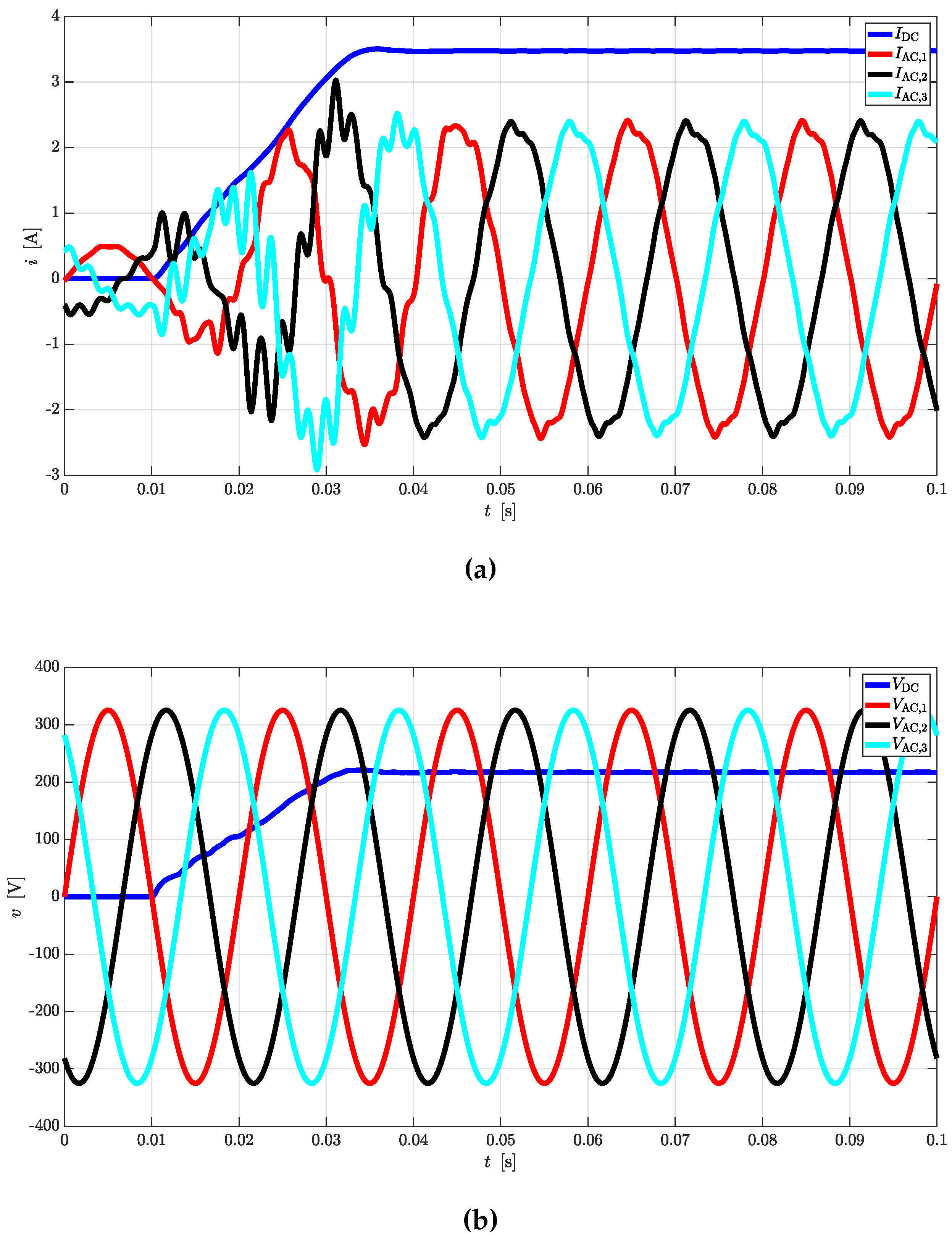

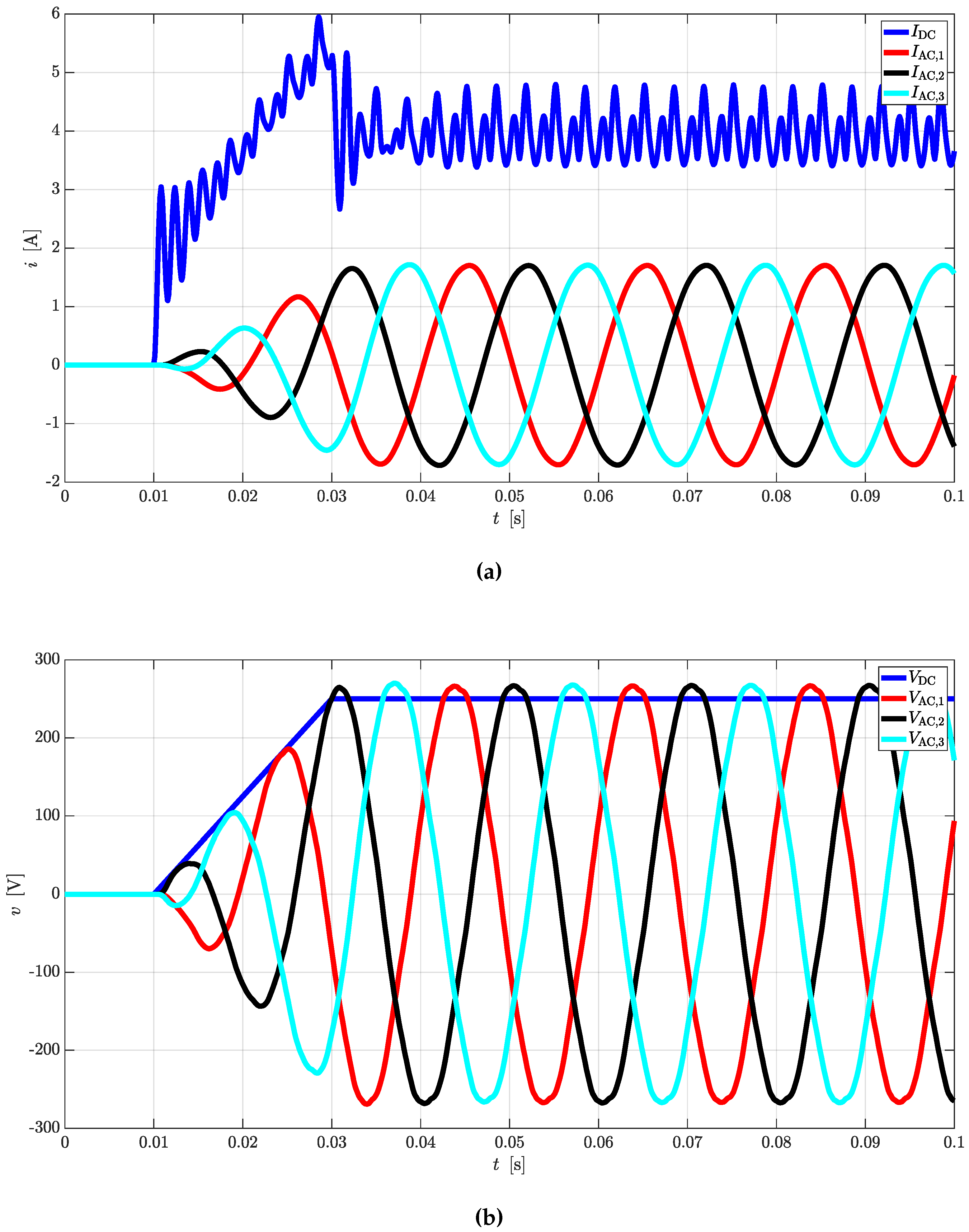

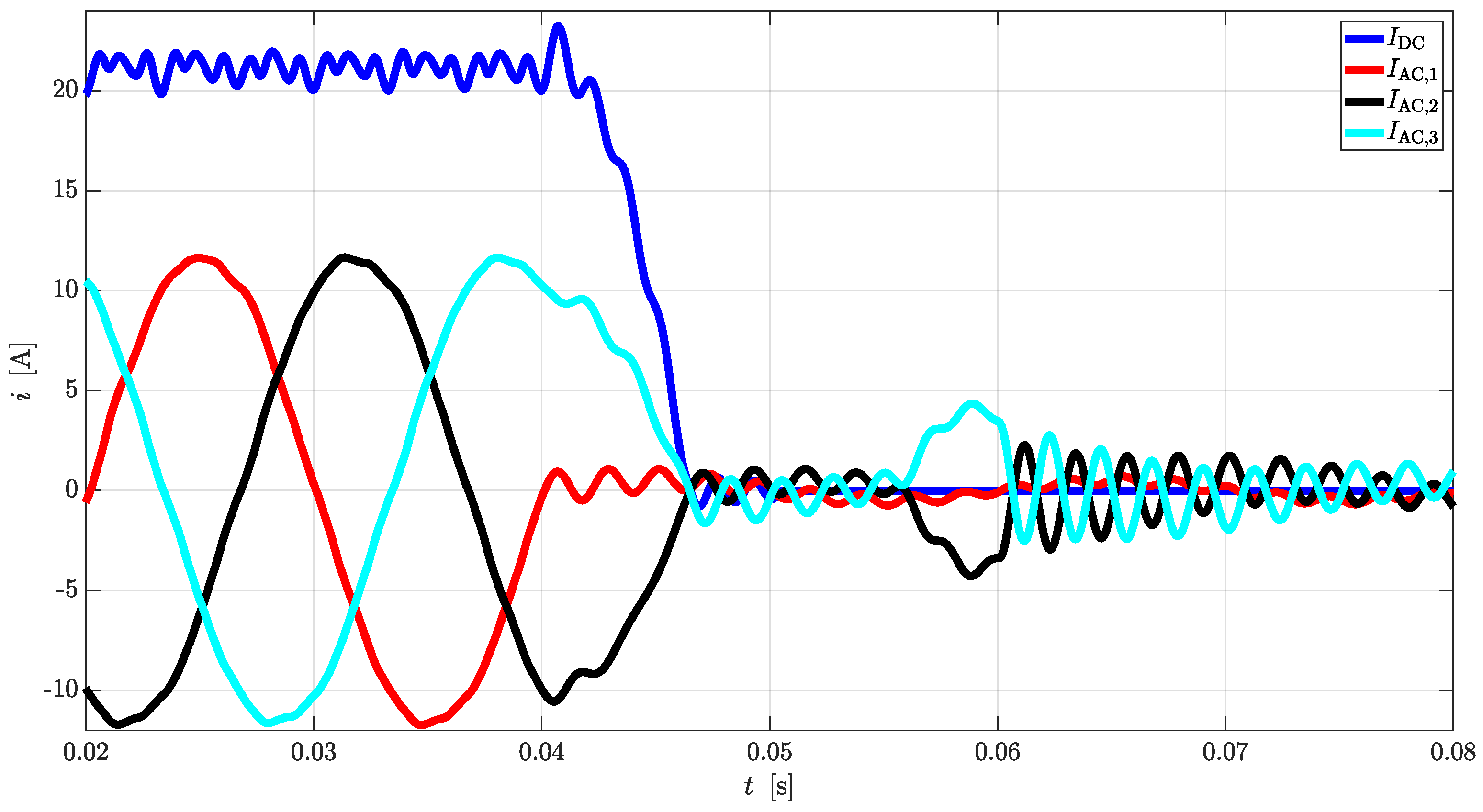

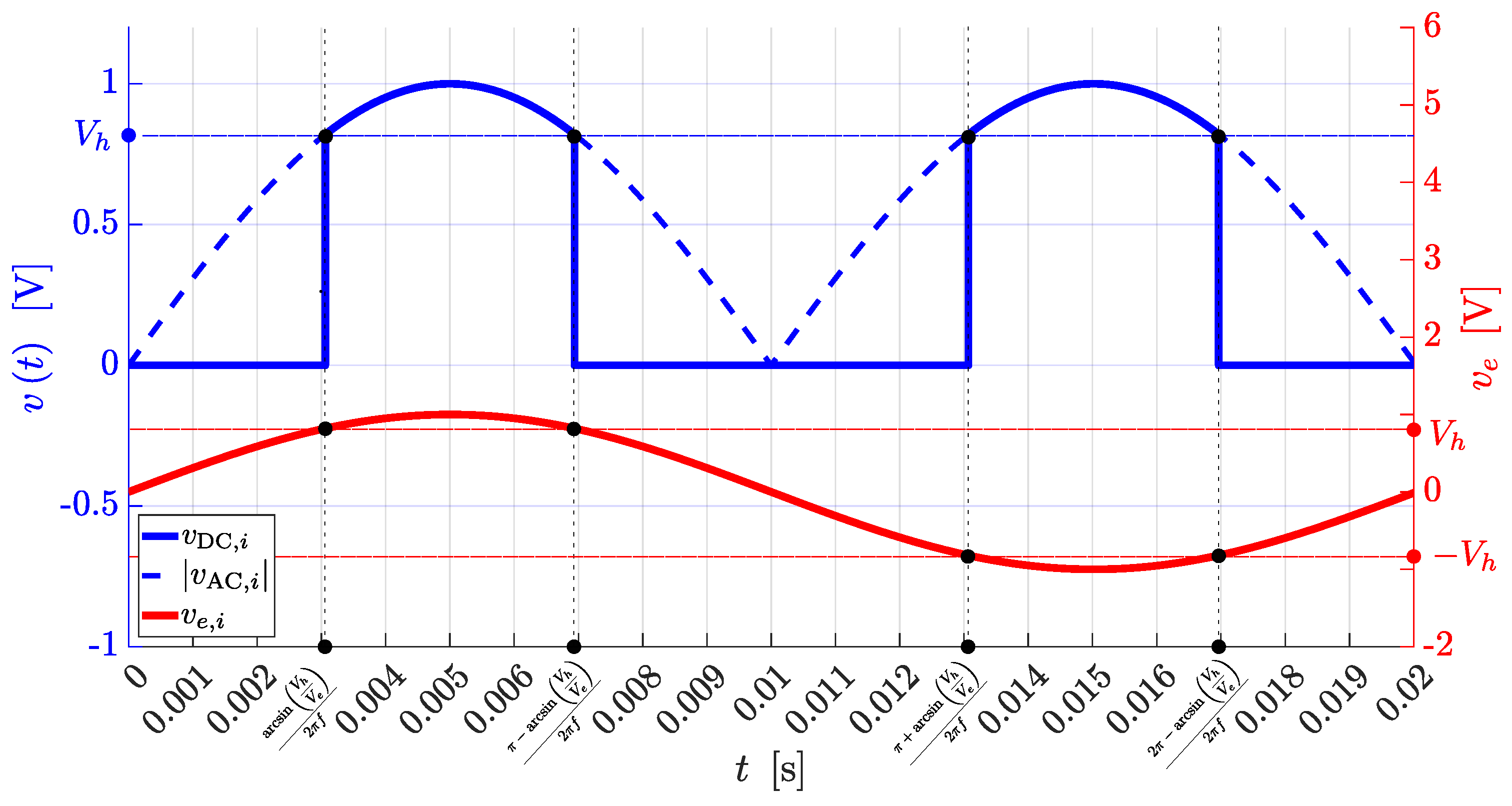

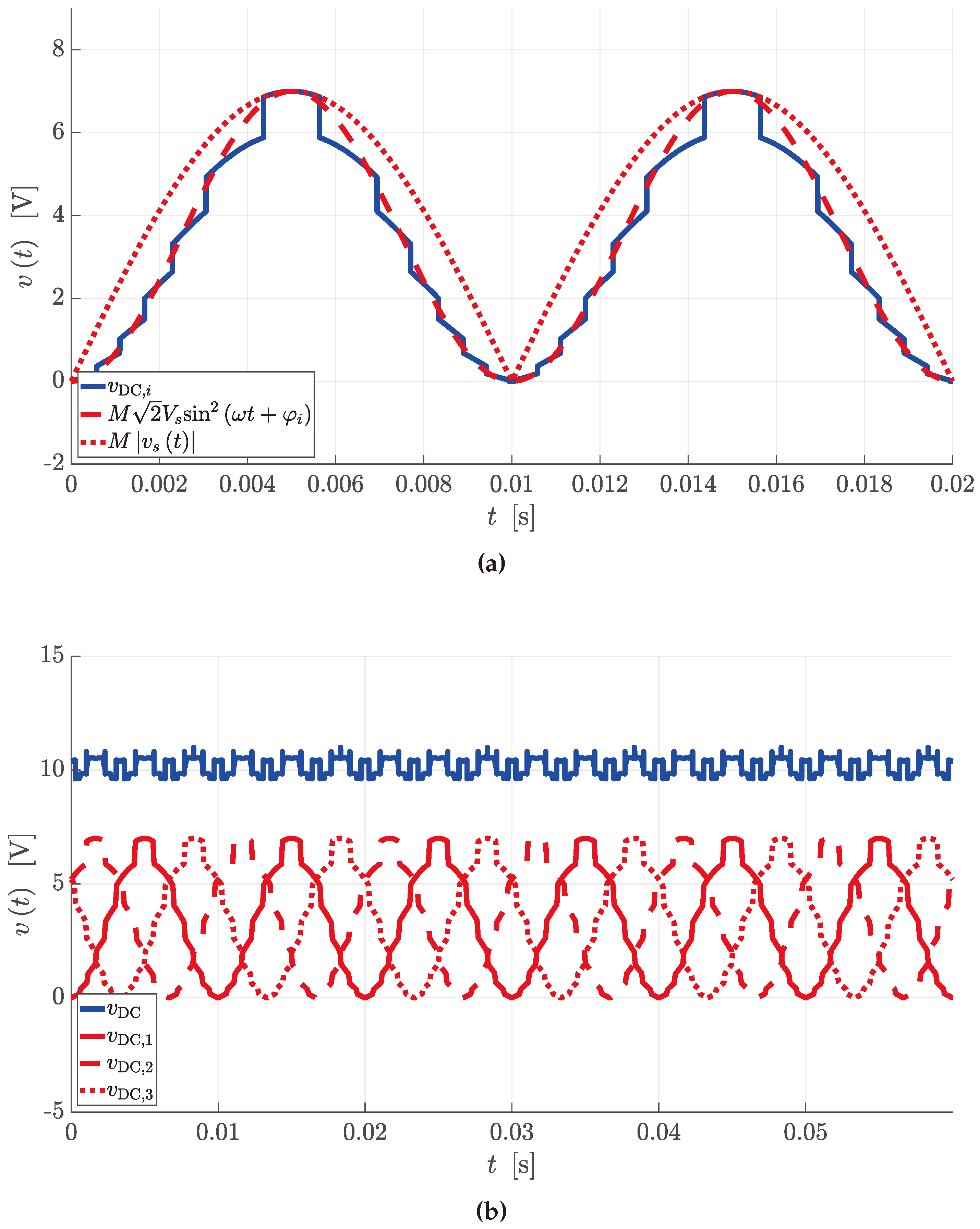

Figure 5 shows an example of ideal waveform for

with 7 levels compared to the absolute value of the AC voltage with amplitude

and the quadratic sine having the same peak-to-peak value. Equation (

5) holds also for the other two phases and it can be proved that the rectified voltage on the

i-th phase

can be approximated with:

if

.

Figure 5 reports the ideal waveform

obtained during a rectifier operation of the CT through the combination of the 7-level

,

and

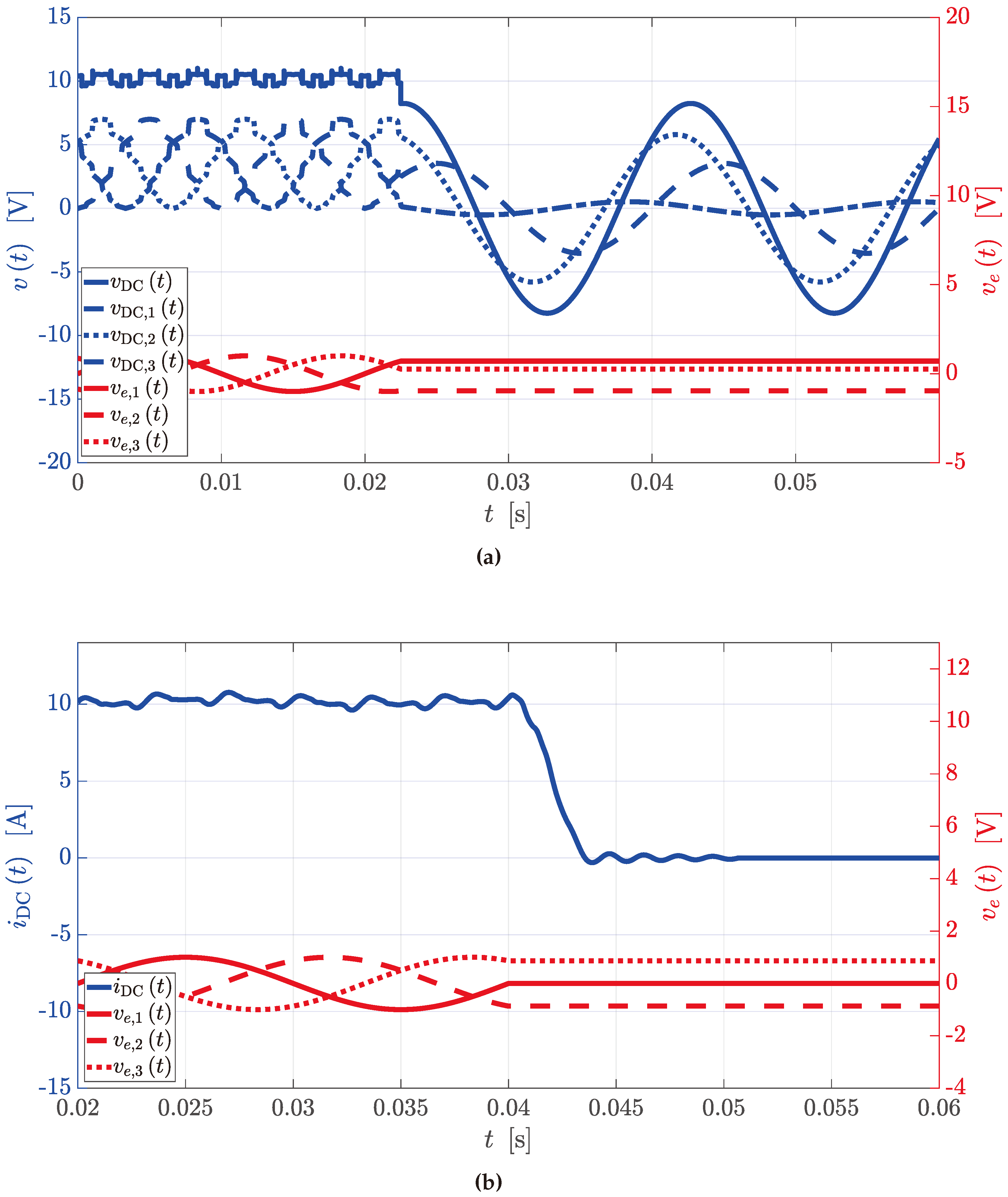

. It can be noted that the ripple is very limited even in absence of any passive filter. Ideal behaviors for inverter operations is such that

,

and

are flipped with respect to the x axis every 10

. Thus, the ideal time evolution of

,

and

are obtained.