Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 68T99; 65F55

1. Introduction

2. Discrete Data from AC Equation

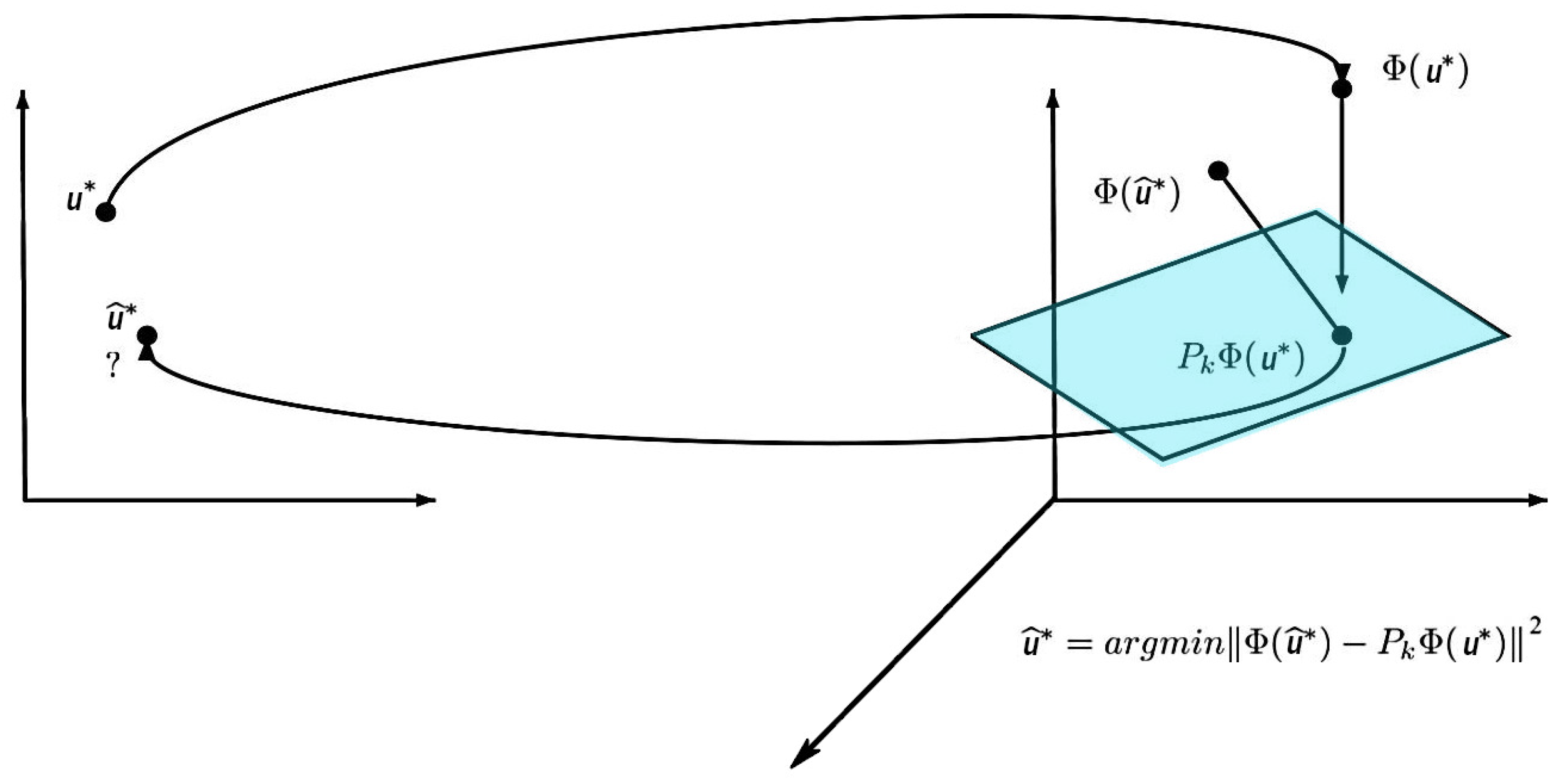

3. Reduced Order Model

3.1. Linear Dimension Reduction (PCA)

3.2. Nonlinear Dimension Reduction (KPCA)

4. Numerical Results

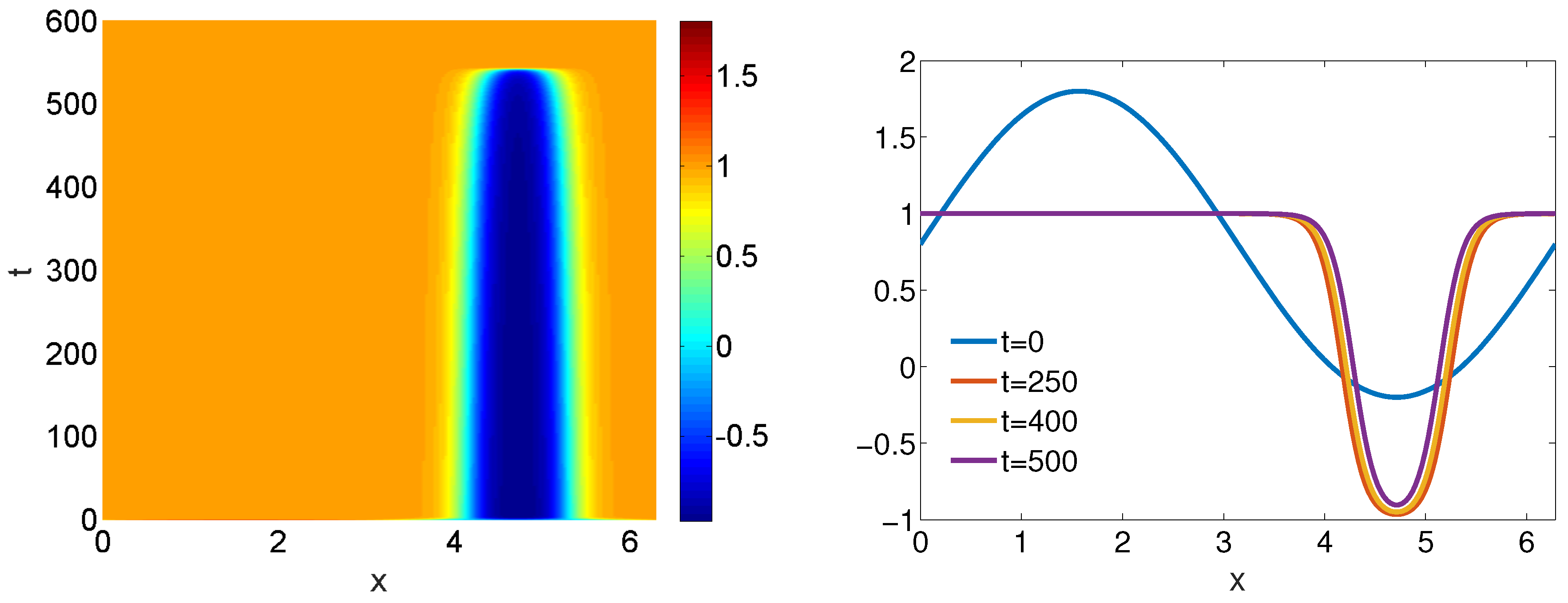

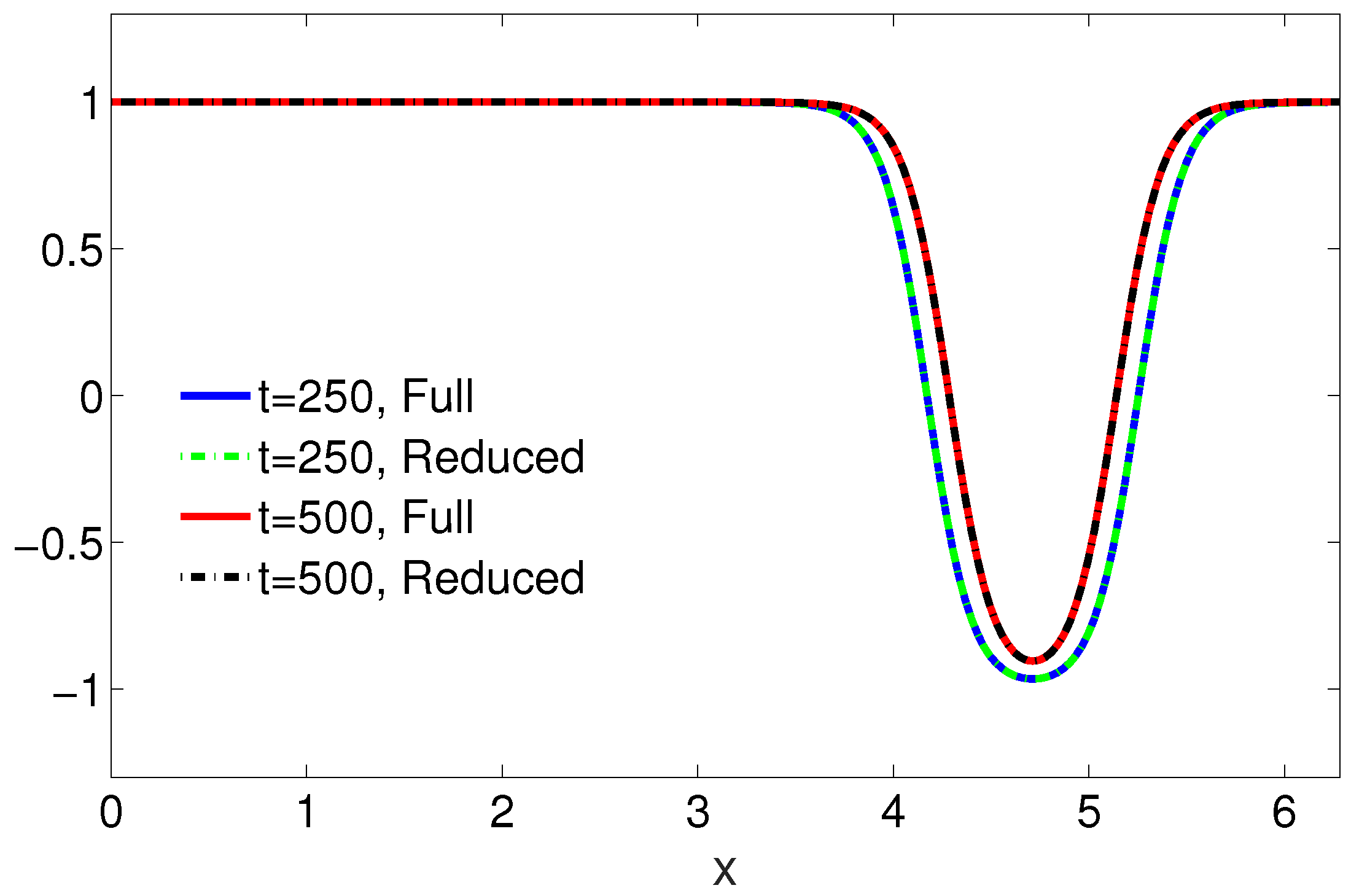

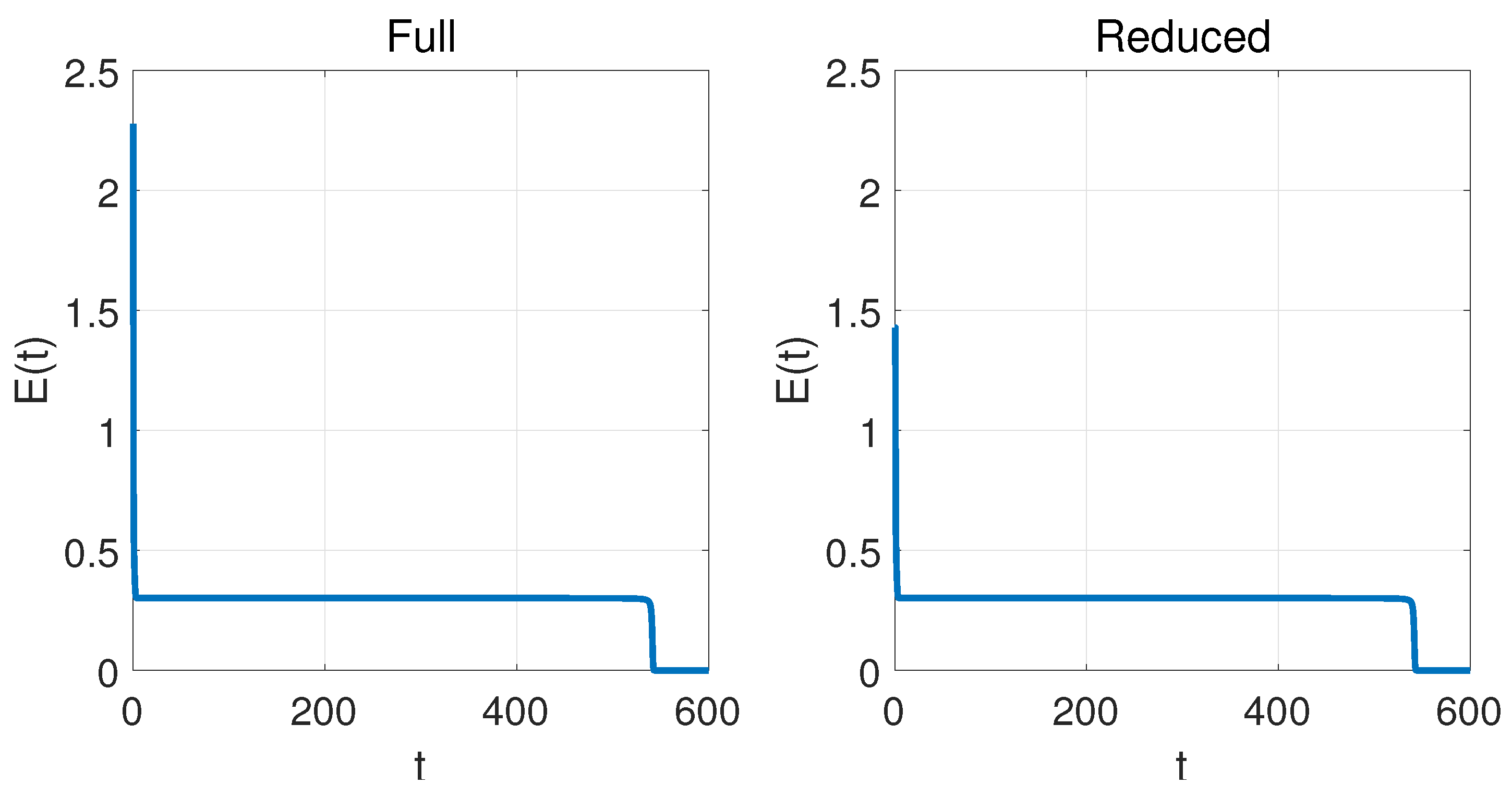

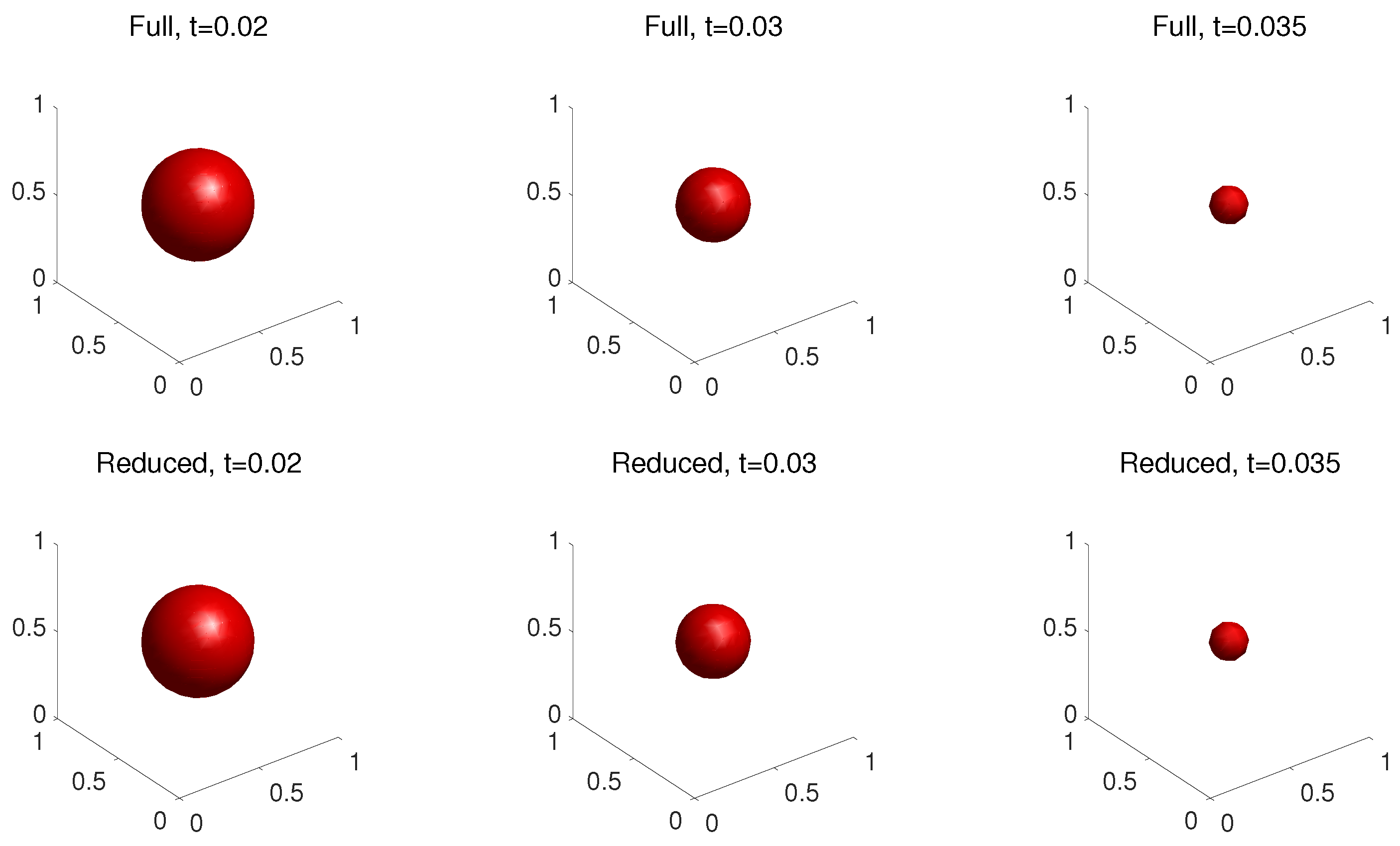

4.1. One-Dimensional Problem

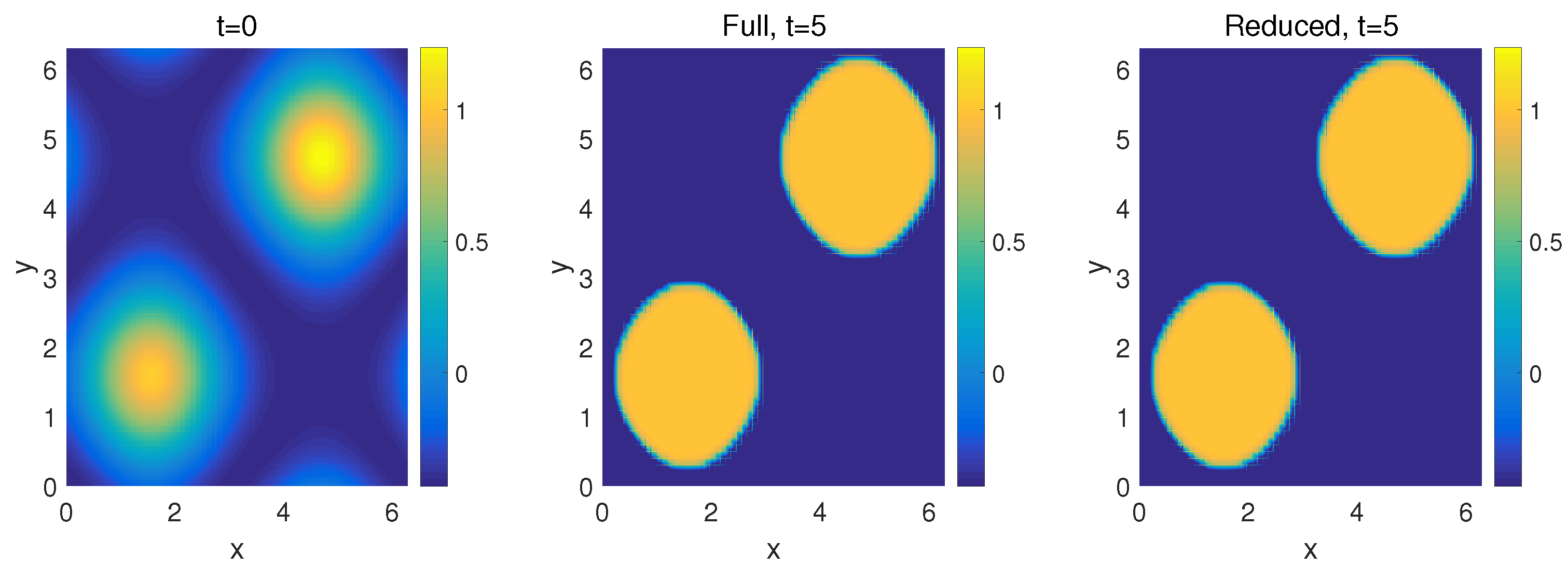

4.2. Two-Dimensional Problem

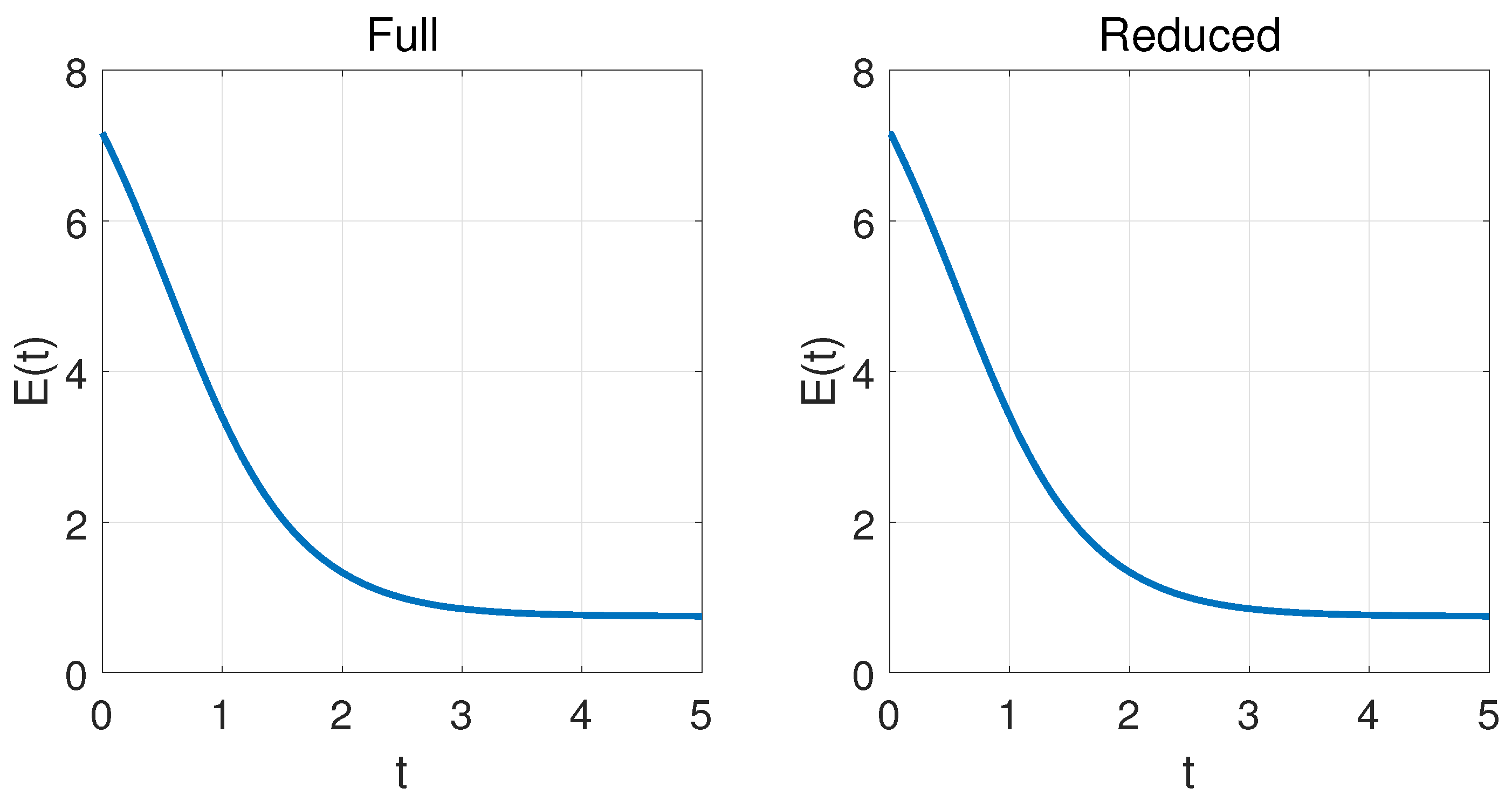

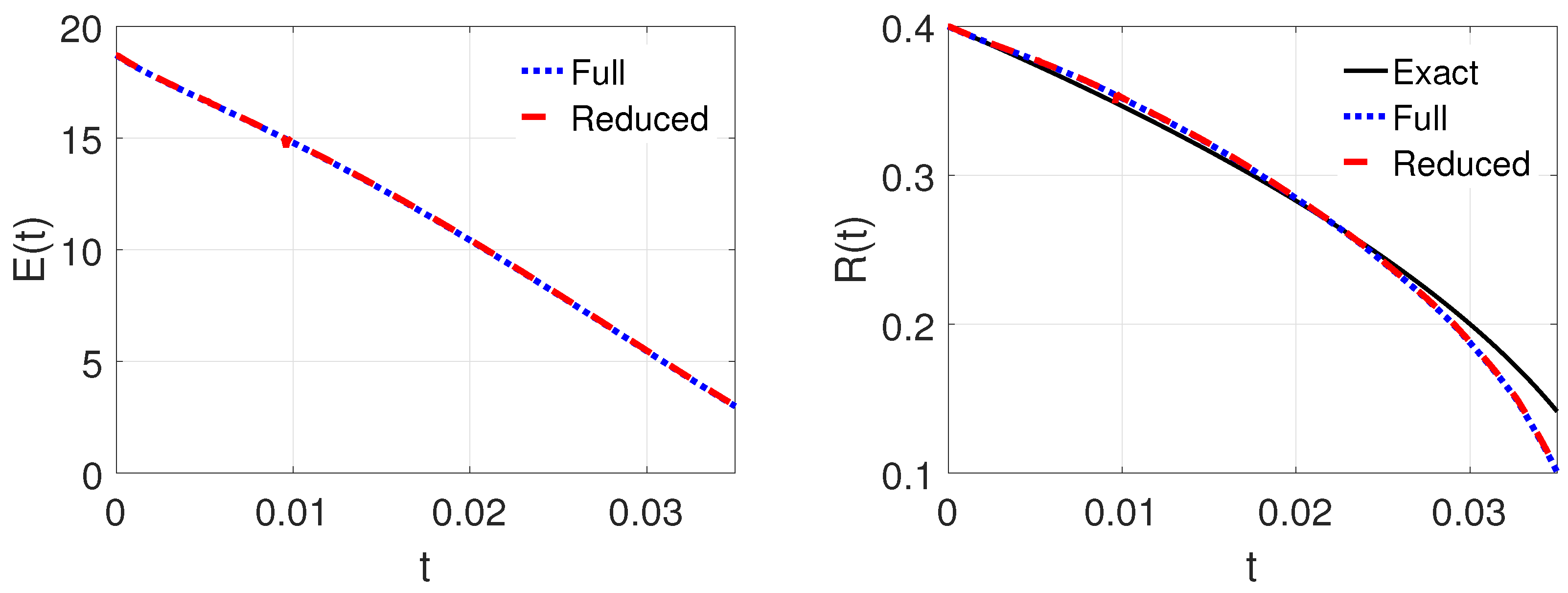

4.3. Three-Dimensional Problem

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, S.M.; Cahn, J.W. A microscopic theory for antiphase boundary motion and its application to antiphase domain coarsening. Acta Metall 1979, 27, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Q. Phase-field models for microstructure evolution. Annual Review of Materials Research 2002, 32, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes̆, M.; Chalupecký, V.; Mikula, K. Geometrical image segmentation by the Allen-Cahn equation. Applied Numerical Mathematics 2004, 51, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Feng, J.J.; Liu, C.; Shen, J. Numerical simulations of jet pinching-off and drop formation using an energetic variational phase-field method. Journal of Computational Physics 2006, 218, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Prohl, A. Numerical analysis of the Allen-Cahn equation and approximation for mean curvature flows. Numerische Mathematik 2003, 94, 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunca, M.; Karasözen, B. Linearly implicit methods for Allen-Cahn equation. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2023, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, Z. Multi-Reconstruction from Points Cloud by Using a Modified Vector-Valued Allen–Cahn Equation. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.U.; Haq, S.; Ali, I.; Ebadi, M.J. Approximate Solution of PHI-Four and Allen–Cahn Equations Using Non-Polynomial Spline Technique. Mathematics 2024, 12, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.B.; Bund, B. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Introduction; From ThriftBooks-Atlanta (AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A., Richard D. Irwin, 1983.

- Johnson, R.; Wichern, D. Applied multivariate statistical analysis; New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Michael Bell, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hached, M.; Jbilou, K.; Koukouvinos, C.; Mitrouli, M. A Multidimensional Principal Component Analysis via the C-Product Golub–Kahan–SVD for Classification and Face Recognition. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.G.; Huerta, A.; Zlotnik, S.; Díez, P. A kernel Principal Component Analysis (kPCA) digest with a new backward mapping (pre-image reconstruction) strategy. Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya - Barcelona. [CrossRef]

- Mika, S.; Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.; Müller, K.R.; Scholz, M.; Rätsch, G. Kernel PCA and De-Noising in Feature Spaces. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Kearns, M.; Solla, S.; Cohn, D., Eds. MIT Press, 1998, Vol. 11.

- Rathi, Y.; Dambreville, S.; Tannenbaum, A. Statistical Shape Analysis using Kernel PCA. School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology 2006, 6064, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A. Learning with kernels: support vector machines, regularization, optimization, and beyond; Adaptive computation and machine learning, MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.; Müller, K.R. Nonlinear Component Analysis as a Kernel Eigenvalue Problem. Neural Computation 1998, 10, 1299–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Kernel Principal Component Analysis and its Applications in Face Recognition and Active Shape Models. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2012, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ying, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, B. Broad Learning Model with a Dual Feature Extraction Strategy for Classification. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.F.; Cox, M.A.A. Multidimensional Scaling; Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, Chapman & Hall: London, U.K., 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.K.I. On a connection between kernel PCA and metric multidimensional scaling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 13; Leen, T., Dietterich, T., Tresp, V., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Jiang, L.; Li, Q. A reduced order method for Allen–Cahn equations. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2016, 292, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikova, I.; Barone, M.F. Efficient non-linear proper orthogonal decomposition/Galerkin reduced order models with stable penalty enforcement of boundary conditions. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2012, 90, 1337–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunca, M.; Karasözen, B. Energy Stable Model Order Reduction for the Allen–Cahn Equation. In Model Reduction of Parametrized Systems; Benner, P., Ohlberger, M., Patera, A., Rozza, G., Urban, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, W.; Li, R.C. Unconventional Schemes for a Class of Ordinary Differential Equations. Journal of Computational Physics 1997, pp. 316–331. [CrossRef]

- Çakır, Y.; Uzunca, M. Nonlinear Reduced Order Modelling for Korteweg-de Vries Equation. International Journal of Informatics and Applied Mathematics 2024, 7, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, H.G.; Jeong, D.; Kim, J. An unconditionally stable hybrid numerical method for solving the Allen-Cahn equation. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 2010, 60, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasözen, B.; Uzunca, M.; Sariaydin-Filibelioğlu, A.; Yücel, H. Energy Stable Discontinuous Galerkin Finite Element Method for the Allen-Cahn Equation. International Journal of Computational Methods 2018, 15, 1850013 (26 pages). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | 3.09e-01 | 1.28e-01 | 1.50e-02 | 1.55e-02 | 2.34e-03 | 2.41e-03 |

| KPCA | 2.56e-04 | 1.71e-05 | 1.88e-05 | 2.28e-04 | 2.71e-04 | 5.14e-04 |

| Cpu Time (Sec.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Iteration | Without Iteration | With Iteration | Without Iteration | |

| 1 | 2.56e-04 | 2.56e-04 | 3.7850 | 0.3690 |

| 2 | 1.71e-05 | 1.28e-04 | 3.9650 | 0.3800 |

| 3 | 1.88e-05 | 2.56e-04 | 4.2110 | 0.4115 |

| 4 | 2.28e-04 | 1.29e-04 | 4.0152 | 0.4025 |

| 5 | 2.71e-04 | 1.09e-03 | 4.6500 | 0.4780 |

| 6 | 5.14e-04 | 4.92e-03 | 4.7968 | 0.4975 |

| k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | 2.80e-01 | 8.22e-02 | 4.78e-02 | 2.13e-02 | 6.53e-03 | 3.54e-03 |

| KPCA | 2.50e-03 | 1.49e-03 | 3.28e-03 | 1.92e-03 | 2.45e-03 | 1.37e-03 |

| Cpu Time (Sec.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Iteration | Without Iteration | With Iteration | Without Iteration | |

| 1 | 2.50e-03 | 3.80e-03 | 12.2090 | 1.4310 |

| 2 | 1.49e-03 | 1.89e-03 | 11.7000 | 1.6470 |

| 3 | 3.28e-03 | 3.77e-03 | 12.2340 | 1.5070 |

| 4 | 1.92e-03 | 1.82e-03 | 12.6700 | 1.7160 |

| 5 | 2.45e-03 | 3.66e-03 | 13.2030 | 1.8110 |

| 6 | 1.37e-03 | 1.68e-03 | 13.5700 | 1.8230 |

| k | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | 7.06e-02 | 8.55e-02 | 1.38e-02 | 1.16e-02 | 2.78e-03 | 4.85e-04 |

| KPCA | 4.57e-03 | 2.25e-03 | 4.83e-03 | 2.03e-03 | 6.68e-03 | 5.37e-03 |

| Cpu Time (Sec.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Iteration | Without Iteration | With Iteration | Without Iteration | |

| 1 | 4.57e-03 | 3.69e-03 | 12.2990 | 2.1780 |

| 2 | 2.25e-03 | 2.47e-03 | 13.4760 | 2.1510 |

| 3 | 4.83e-03 | 4.74e-03 | 14.1110 | 2.0270 |

| 4 | 2.03e-03 | 2.17e-03 | 14.1600 | 2.7510 |

| 5 | 6.68e-03 | 6.55e-03 | 15.2780 | 2.5950 |

| 6 | 5.37e-03 | 5.30e-03 | 15.1340 | 2.9640 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).