Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

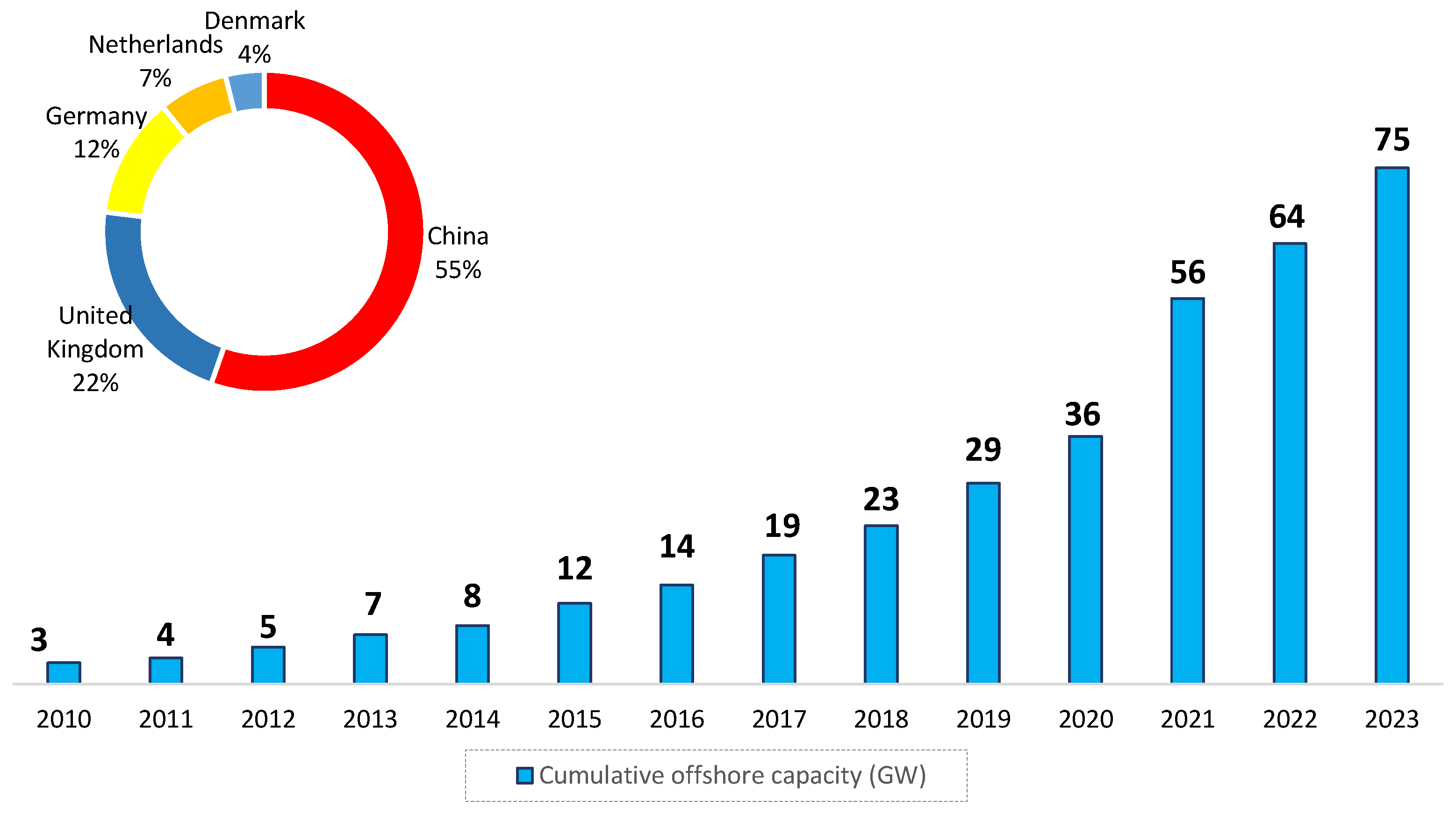

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

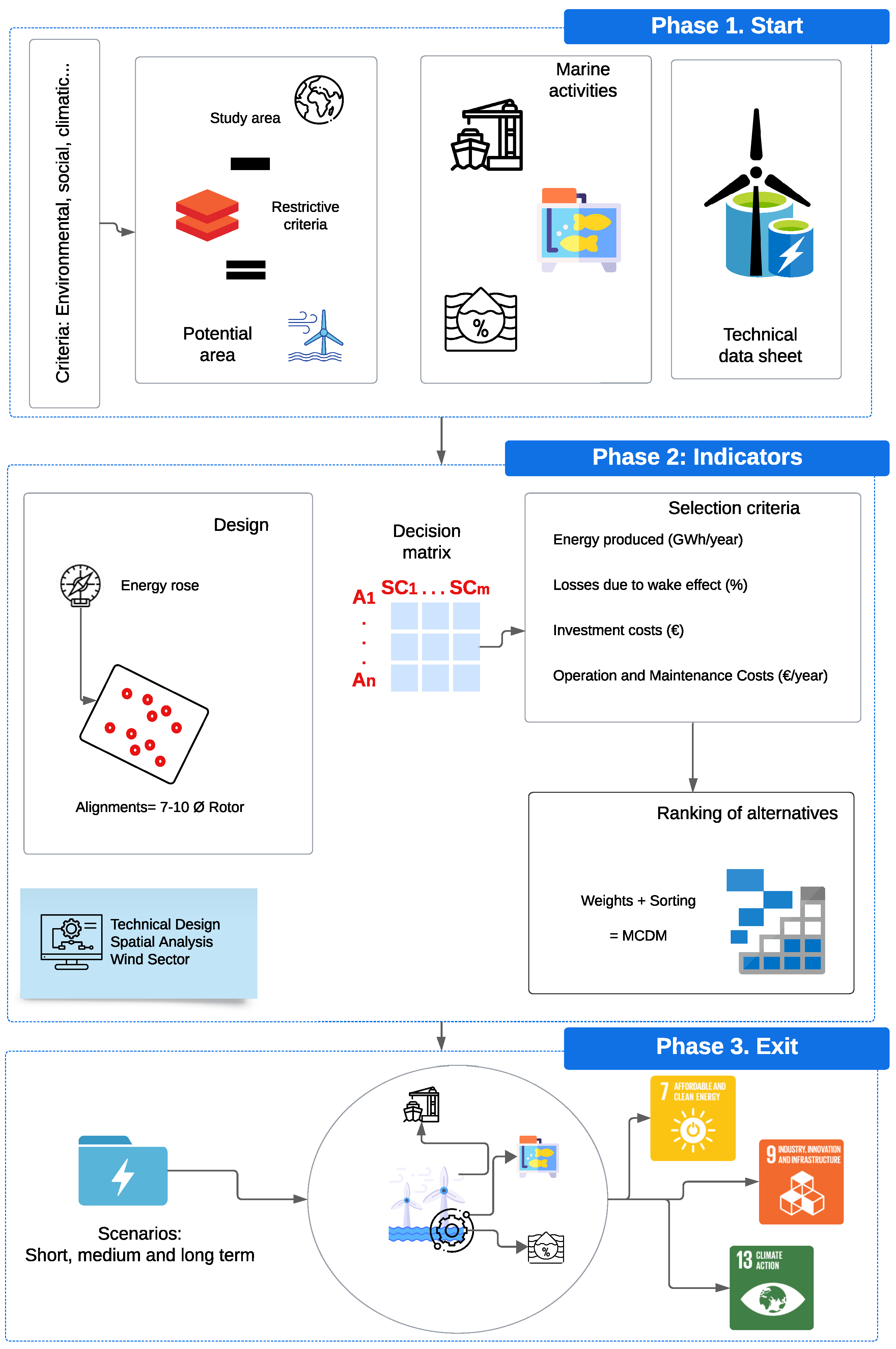

2.1. Stages

2.1.1. Phase 1. Start

-

Identifying areas with potential for offshore wind energy generation: Identifying areas with potential for offshore wind energy involves a highly complex spatial process that encompasses a wide variety of factors. These factors include climatic aspects such as wind speed, bathymetry (sea depth), wave height, and turbulence, as these directly influence the efficiency and safety of offshore wind installations. Environmental considerations must also be taken into account, such as proximity to protected areas and habitat conservation, to minimize ecological impact. Social factors such as the visual impact of wind turbines on communities, noise levels, existing maritime routes, and fishing zones that may be affected by the installation of infrastructure are also assessed [17]. These elements are categorized into exclusion criteria, which serve to eliminate unsuitable areas, and selection criteria, which help identify the most promising areas within the study region [18,19].Depending on the study area, these regions may already be regulated. In Spain, for example, the Maritime Spatial Planning Plans (POEM) are a key tool within the European Union’s Integrated Maritime Policy. These plans are implemented to comply with Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, which establishes a framework for maritime spatial planning [20]. In Spain, this directive has been incorporated through the Marine Environment Protection Law 41/2010 [21] and Royal Decree 363/2017, which establishes a framework for maritime spatial planning [22]. This spatial planning process has required significant coordination among various ministries with maritime competences, coastal Autonomous Communities, and various sectors related to the use of the sea.

-

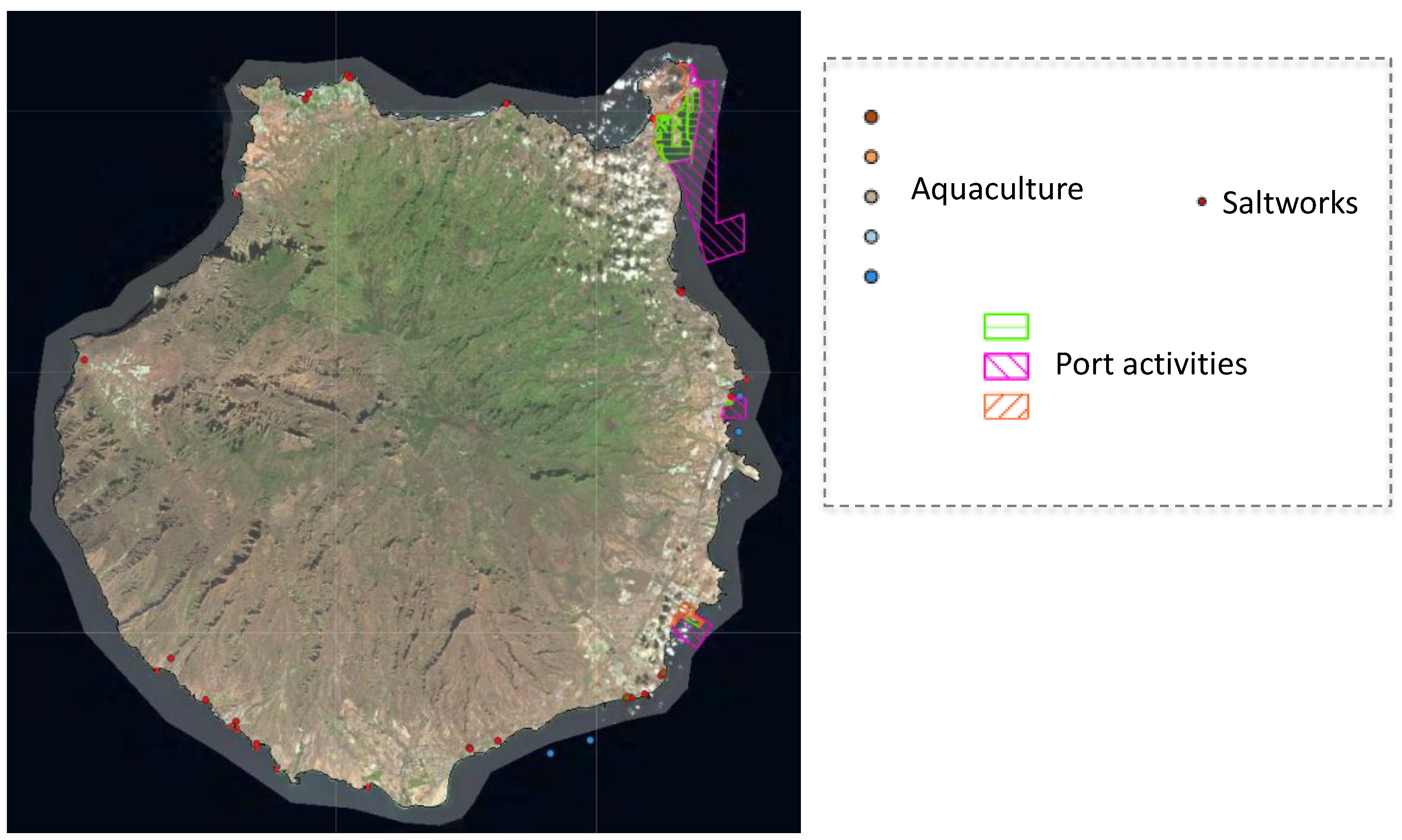

Evaluating which maritime activities could be partially or fully decarbonized through the use of electricity generated from offshore winds: In this stage, a comprehensive analysis is conducted to identify maritime activities that could benefit from the electricity generated by offshore wind turbines, aiming to reduce their reliance on conventional energy sources and promote sustainability. For instance, in aquaculture, wind energy can be used to power water pumping systems, heating and cooling systems, as well as logistics and transportation operations, significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with these activities [23].In salt extraction, energy used for the extraction, pumping, and treatment of seawater, as well as for heating and evaporation systems, could also be replaced with wind energy, contributing to a lower carbon footprint in salt production processes [24]. Additionally, port activities, which require substantial energy for the operation of cranes, machinery, warehouse refrigeration, lighting, and loading and unloading of ships, could be decarbonized with the use of wind energy [25]. Integrating renewable energy into these sectors would not only enhance their sustainability but also reduce operational costs in the long term.

- Selecting the most appropriate wind turbine technology for the project implementation. Once potential areas have been identified and decarbonization opportunities have been assessed, the next step is to select the most suitable wind turbine technology. This process includes considering technical factors such as turbulence, which must be evaluated to comply with standards set by the IEC 61400-1 norm [26], and the bathymetry of the study area, which determines whether a fixed or floating foundation is required for the wind turbines [27]. Fixed foundations are appropriate for shallow waters, while floating foundations allow turbines to be installed in deeper waters where winds tend to be stronger and more consistent. Other aspects, such as the generation capacity of each type of wind turbine, their resistance to adverse weather conditions, and their long-term maintenance requirements, must also be considered. The correct selection of technology not only ensures the technical and economic viability of the project but also minimizes environmental and social impacts, thus guaranteeing the project’s long-term success.

2.1.2. Phase 2. Indicators

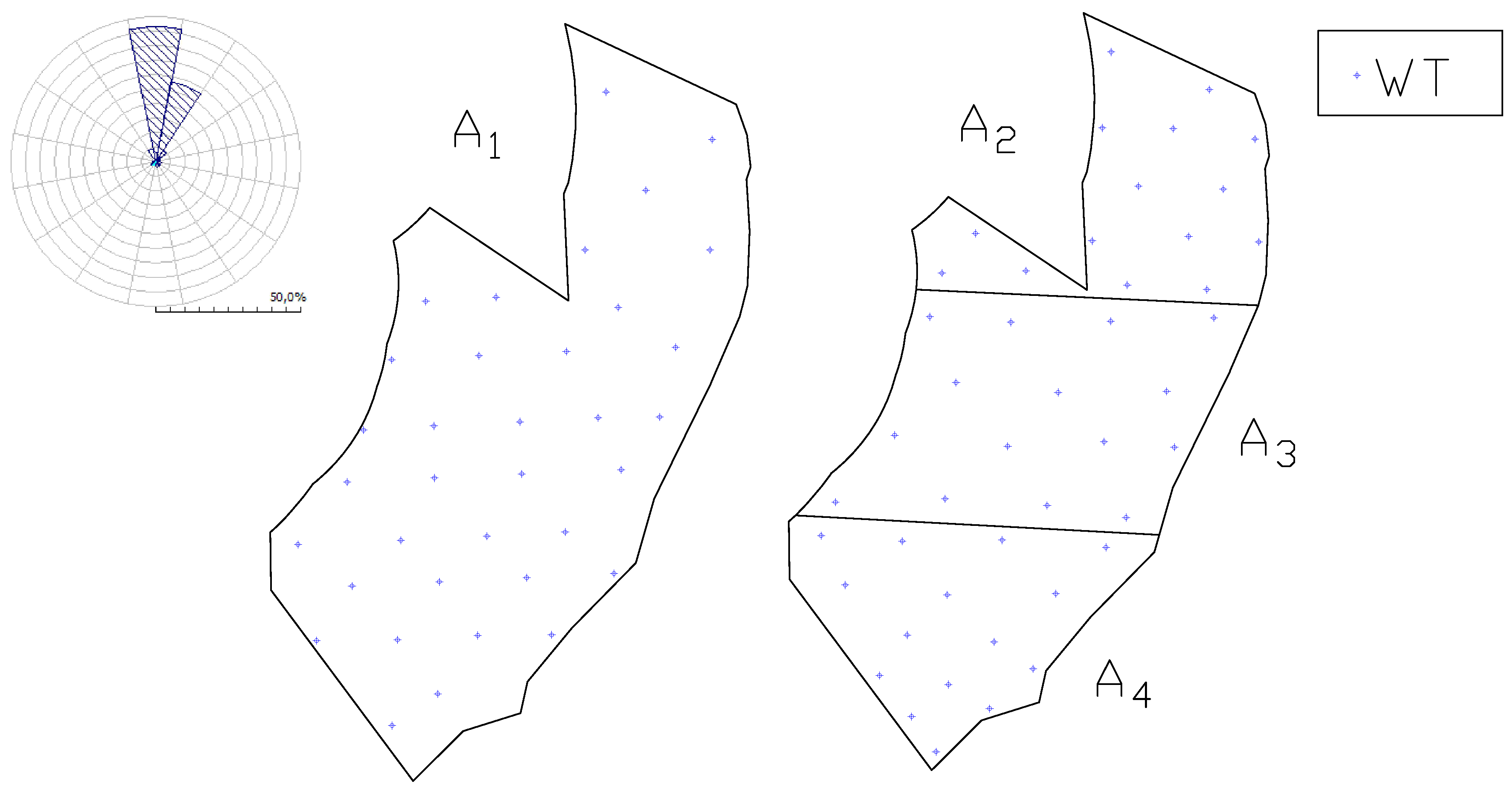

- The establishment of the design of an offshore wind farm is a multifaceted process that requires careful consideration of several factors. Initially, the nominal capacity of the plant is determined, followed by a thorough analysis of the wind direction to ensure that the alignments of the wind turbines are optimal in relation to the predominant energy rose [28]. The distances between the wind turbines are determined based on the rotor diameter (D) selected during the initial phase of the project. It is established that between the alignments of wind turbines the distance should be in the range of 7 to 10 times D, while between the wind turbines in the same row it is recommended to maintain a distance of 3 to 5 times D [28]. This specific arrangement helps to minimize the wake effect, thus optimizing the overall performance of the park. It is essential to use specialized tools, such as technical design programs, to accurately perform this distribution. Using spatial layers in these programs, the three-dimensional arrangement of the wind turbines can be visualized and analyzed, facilitating decision-making and optimization of the offshore wind farm design. A polygon mesh is created that comprehensively covers the potential area, ensuring complete and detailed coverage for subsequent analysis. This approach allows all possible locations within the study area to be explored and facilitates comparative evaluation of the different alternatives.

-

During the generation of the decision matrix, the selection criteria that characterize each alternative are defined, covering technical, economic and environmental aspects. Among the recommended criteria are:

- Annual electric energy generated: This criterion evaluates the amount of electric energy expected to be produced each year with each alternative. It is a key indicator of the project’s energy generation capacity [29].

- Wake effect losses: This criterion considers the efficiency losses caused by the wake effect between the wind turbines. A lower wake effect indicates a more efficient arrangement of wind turbines and, therefore, less energy loss [30].

- Capex: This refers to the costs associated with the initial investment in the wind farm infrastructure, including the purchase and installation of equipment and the construction of the necessary infrastructure [31].

- Opex: This criterion evaluates the expected operating and maintenance costs over the life of the wind farm, including repairs, regular inspections, and operating costs. The calculation of the electrical energy fed into the grid is a complex process that can be carried out using general equations, although the use of specialized programs in the wind sector is recommended, for example: WasP©[32], FLORIS©[33]. These programs can provide detailed and accurate analyses taking into account a variety of factors, such as wind speed, air density, and specific characteristics of the wind farm desig [34].

- The development of a ranking of alternatives based on the indicators from the previous step is a complex procedure that is usually addressed using multi-criteria evaluation methods (MCDM) [35]. These methods are widely used and have numerous variants for their application. In general terms, the process begins with the definition of the relative weights of the different factors or criteria used in the evaluation [36]. Subsequently, a ranking of the alternatives is established based on these weights and the values obtained for each criterion [37]. For example, the Entropy method is used to determine the relative weights of criteria, allowing decision makers to assign importance to each of them in relation to the others. Once these weights have been established, the TOPSIS technique is used to rank the alternatives based on their proximity to the ideal solution and their distance from the anti-ideal solution, thus considering both the positive and negative aspects of each alternative [38].

2.1.3. Phase 3. Exit

2.2. WAsP Wind Energy Calculation

1. Wind Distribution (Weibull)

- k is the shape parameter (indicates the dispersion of wind speeds).

- c is the scale parameter (a measure of the "characteristic wind speed").

- is the probability of wind speed v.

2. Available Wind Power

- P is the wind power (W).

- is the air density (typically 1.225 kg/m³ at sea level and 15°C).

- A is the swept area of the blades, (m²), where R is the rotor radius.

- v is the wind speed (m/s).

3. Turbine Power Curve

- is the power produced by the turbine at wind speed v.

- is the probability of that wind speed given by the Weibull distribution.

4. Wind Speed Adjustment at the Site (Logarithmic Law)

- is the wind speed at height z (turbine height).

- is the wind speed at reference height .

- is the roughness length of the terrain.

5. Annual Energy Production (AEP) Calculation

- is the power generated at wind speed .

- is the time (in hours) that the wind blows at that speed .

6. Adjustment for Losses and Availability

- is an overall efficiency factor accounting for losses and the operational availability of the turbine.

2.3. Entropy Method for Determining Criteria Weights

1. Normalization of the Decision Matrix

- is the normalized value of criterion j for alternative i.

- m is the number of alternatives.

2. Entropy Calculation for Each Criterion

- is the entropy of criterion j.

- is a normalization constant to ensure that is between 0 and 1.

- If , it is assumed that .

3. Calculation of the Degree of Diversification (Information)

- measures the dispersion of the values of criterion j. If all values are the same, , and if the values are highly varied, will be higher.

4. Calculation of the Criteria Weights

- is the weight of criterion j.

- n is the number of criteria.

- It is an **objective** approach that does not require decision-makers to provide subjective weightings.

- It uses the **dispersion of data** to determine the importance of each criterion, providing a quantitative approach.

2.4. VIKOR Method for Ranking Alternatives

1. Determine the Best and Worst Values for Each Criterion

2. Calculate the Utility and Regret Measures for Each Alternative

3. Compute the VIKOR Index for Each Alternative

- ,

- ,

- v is a weight that represents the importance of the majority rule (usually ).

4. Rank the alternatives based on

- Acceptable advantage:, where and are the top two ranked alternatives, and is a predefined threshold.

- Acceptable stability: The alternative ranked first based on should also be the best-ranked by at least one of or .

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1. Start

3.2. Phase 2. Indicators

- A wind farm with a nominal capacity of 525 MW, covering nearly the entire potential area and resulting in a single alternative () with 35 turbines.

- A wind farm with a nominal capacity of 225 MW, generating three distinct alternatives (-), each with 15 turbines.

- Wind speed (m/s) []: Average wind speed from the data campaign at 150 m height. Source: Vortex [45].

- Bathymetry (m) []: Source:[46].

- Wave height []: Source: [47].

- Distance to port (km) []

- CAPEX and OPEX [] [] (Mdd): Based on the floating wind farm described by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [49].

4. Discussion

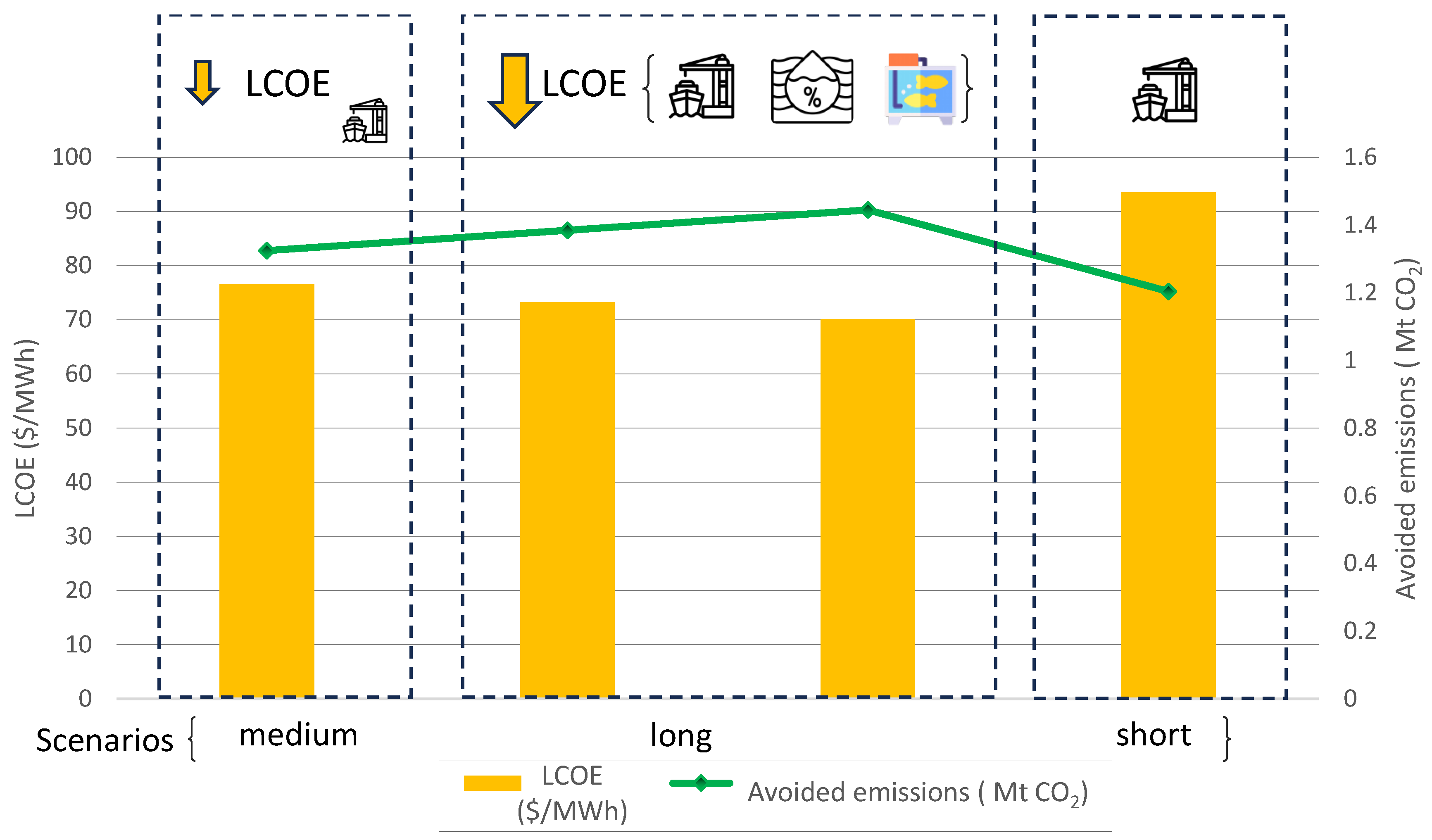

4.1. Scenarios

4.2. SDG and Offshore Wind Energy

5. Conclusions

References

- Nikologianni, A.; Betta, A.; Pianegonda, A.; Favargiotti, S.; Moore, K.; Grayson, N.; Morganti, E.; Berg, M.; Ternell, A.; Ciolli, M.; Angeli, M.; Nilsson, A.M.; Gretter, A. New Integrated Approaches to Climate Emergency Landscape Strategies: The Case of Pan-European SATURN Project. Sustainability 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, C.A. Paris Agreement. International Legal Materials 2016, 55, 740–755. [CrossRef]

- Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 2022, 377. [CrossRef]

- The role of renewable energy and urbanization towards greenhouse gas emission in top Asian countries: Evidence from advance panel estimations. Renewable Energy 2022, 186, 207–216. [CrossRef]

- Salkuti, S.R. Emerging and Advanced Green Energy Technologies for Sustainable and Resilient Future Grid. Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 6667 2022, 15, 6667. [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, Y.; Guan, F.; Wang, N. How to coordinate the relationship between renewable energy consumption and green economic development: from the perspective of technological advancement. Environmental Sciences Europe 2020, 32, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- The Evolution of Energy Efficiency Policy to Support Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis - IEA, 2023.

- Kronfeld-Goharani, U. Maritime economy: Insights on corporate visions and strategies towards sustainability. Ocean & Coastal Management 2018, 165, 126–140. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.V.; Guanche, R.; Ondiviela, B.; Castellanos, O.F.; Juanes, J. Marine renewable energy potential: A global perspective for offshore wind and wave exploitation. Energy Conversion and Management 2018, 177, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M.D.; Diez, J.J.; López, J.S.; Negro, V. Why offshore wind energy? Renewable Energy 2011, 36, 444–450. [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Report 2023 - Global Wind Energy Council, 2023.

- wind energy council (GWEC), G. Global wind report 2023. https://www.gwec.net, 2023.

- Boyd, C.E.; D’Abramo, L.R.; Glencross, B.D.; Huyben, D.C.; Juarez, L.M.; Lockwood, G.S.; McNevin, A.A.; Tacon, A.G.; Teletchea, F.; Tomasso, J.R.; Tucker, C.S.; Valenti, W.C. Achieving sustainable aquaculture: Historical and current perspectives and future needs and challenges. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 2020, 51, 578–633. [CrossRef]

- Rghif, Y.; Colarossi, D.; Principi, P. Salt gradient solar pond as a thermal energy storage system: A review from current gaps to future prospects. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 61, 106776. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Okeke, A. Towards sustainability in the global oil and gas industry: Identifying where the emphasis lies. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2021, 12, 100145. [CrossRef]

- Better poison is the cure? Critically examining fossil fuel companies, climate change framing, and corporate sustainability reports. Energy Research & Social Science 2022, 85, 102388. [CrossRef]

- Gil-García, I.C.; García-Cascales, M.S.; Fernández-Guillamón, A.; Molina-García, A. Categorization and Analysis of Relevant Factors for Optimal Locations in Onshore and Offshore Wind Power Plants: A Taxonomic Review. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gil-García, I.C.; Ramos-Escudero, A.; García-Cascales, M.; Dagher, H.; Molina-García, A. Fuzzy GIS-based MCDM solution for the optimal offshore wind site selection: The Gulf of Maine case. Renewable Energy 2022, 183, 130–147. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L.; Cui, L.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Cai, Y. Site selection of wind farms using GIS and multi-criteria decision making method in Wafangdian, China. Energy 2020, 207, 118222. doi:. [CrossRef]

- BOE-A-2017-3950 Real Decreto 363/2017, de 8 de abril, por el que se establece un marco para la ordenación del espacio marítimo.

- BOE-A-2010-20050 Ley 41/2010, de 29 de diciembre, de protección del medio marino.

- BOE.es - DOUE-L-2014-81825 Directiva 2014/89/UE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 23 de julio de 2014, por la que se establece un marco para la ordenación del espacio marítimo.

- Scroggins, R.E.; Fry, J.P.; Brown, M.T.; Neff, R.A.; Asche, F.; Anderson, J.L.; Love, D.C. Renewable energy in fisheries and aquaculture: Case studies from the United States. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 376, 134153. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Bostani, M.; Rashidi, S.; Valipour, M.S. Challenges and opportunities of desalination with renewable energy resources in Middle East countries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 184, 113543. [CrossRef]

- Parhamfar, M.; Sadeghkhani, I.; Adeli, A.M. Towards the application of renewable energy technologies in green ports: Technical and economic perspectives. IET Renewable Power Generation 2023, 17, 3120–3132. [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN IEC 61400-1:2020 Sistemas de generación de energía eóli..

- Manzano-Agugliaro, F.; Sánchez-Calero, M.; Alcayde, A.; San-Antonio-gómez, C.; Perea-Moreno, A.J.; Salmeron-Manzano, E. Wind Turbines Offshore Foundations and Connections to Grid. Inventions 2020, Vol. 5, Page 8 2020, 5, 8. [CrossRef]

- García, I.C.G. Energía eólica 2023.

- Gil-García, I.C.; Fernández-Guillamón, A.; García-Cascales, M.S.; Molina-García, A.; Dagher, H. A green electrical matrix-based model for the energy transition: Maine, USA case example. Energy 2024, 290, 130246. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J.; Jesus, B.; Cerveira, A.; Pires, E.J.S. Offshore Wind Farm Layout Optimisation Considering Wake Effect and Power Losses. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Reliability and economy assessment of offshore wind farms. The Journal of Engineering 2019, 2019, 1554–1559. [CrossRef]

- WAsP.

- FLORIS: FLOw Redirection and Induction in Steady State | Wind Research | NREL.

- Argin, M.; Yerci, V. Offshore wind power potential of the Black Sea region in Turkey. International Journal of Green Energy 2017, 14, 811–818. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lozano, J.M.; Ramos-Escudero, A.; Gil-García, I.C.; García-Cascales, M.S.; Molina-García, A. A GIS-based offshore wind site selection model using fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making with application to the case of the Gulf of Maine. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 210, 118371. [CrossRef]

- Caceoğlu, E.; Yildiz, H.K.; Oğuz, E.; Huvaj, N.; Guerrero, J.M. Offshore wind power plant site selection using Analytical Hierarchy Process for Northwest Turkey. Ocean Engineering 2022, 252, 111178. [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, Y.; Ji, L.; Li, Z. Comprehensive Cost-Benefit Assessment of Offshore Wind Power Based on Improved VIKOR Method. 2023 IEEE IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia, I and CPS Asia 2023 2023, pp. 1268–1273. [CrossRef]

- Vagiona, D.G.; Tzekakis, G.; Loukogeorgaki, E.; Karanikolas, N. Site Selection of Offshore Solar Farm Deployment in the Aegean Sea, Greece. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, Vol. 10, Page 224 2022, 10, 224. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, W.; Fan, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. A novel hybrid MCDM model for machine tool selection using fuzzy DEMATEL, entropy weighting and later defuzzification VIKOR. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 91, 106207. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Rogulj, K.; Kilić Pamuković, J.; Ivić, M. Hybrid MCDM Based on VIKOR and Cross Entropy under Rough Neutrosophic Set Theory. Mathematics 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Govindan, K.; Amat Senin, A.; Jusoh, A. VIKOR Technique: A Systematic Review of the State of the Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications. Sustainability 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Low-Carbon Energy Planning: A Hybrid MCDM Method Combining DANP and VIKOR Approach. Energies 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Visor INFOMAR - MITECO, CEDEX, 2023. Accessed on 15 Sept 2024.

- Gaertner, E.; Rinker, J.; Sethuraman, L.; Zahle, F.; Anderson, B.; et. al. Definition of the IEA 15-Megawatt Offshore Reference Wind. Technical Report NREL/TP-5000-75698, https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/75698.pdf, Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2020.

- FDC, V. Wind Resource Data for wind Farm Developments, 2023.

- EMODnet web service documentation | European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet), 2024.

- Puertos de España. Spectral significant wave height grid. Mapa, 2020.

- Autodesk AutoCAD 2025.

- Musial, W.; Spitsen, P.; andPhilipp Beiter, P.D.; Marquis, M.; Hammond, R.; Shields, M. Offshore Wind Market Report: 2022 Edition. Technical report, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), 2022.

- Strong 2023 offshore wind growth as industry sets course for record-breaking decade - Global Wind Energy Council.

- Frades, J.L.; Barba, J.G.; Negro, V.; Martín-Antón, M.; Soriano, J. Blue Economy: Compatibility between the Increasing Offshore Wind Technology and the Achievement of the SDG. Journal of Coastal Research 2020, 95, 1490 – 1494. [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Obaideen, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; AlMallahi, M.N.; Shehata, N.; Alami, A.H.; Mdallal, A.; Hassan, A.A.M.; Sayed, E.T. Wind Energy Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: Case Study on London Array. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, A.; Natarajan, A.; Kitzing, L.; Madsen, B.; Martí, I., Towards sustainable wind energy. In DTU International Energy Report 2021: Perspectives on Wind Energy; Holst Jørgensen, B.; Hauge Madsen, P.; Giebel, G.; Martí, I.; Thomsen, K., Eds.; DTU Wind Energy: Denmark, 2021; pp. 144–150. [CrossRef]

- Velenturf, A.P.M.; Emery, A.R.; Hodgson, D.M.; Barlow, N.L.M.; Mohtaj Khorasani, A.M.; Van Alstine, J.; Peterson, E.L.; Piazolo, S.; Thorp, M. Geoscience Solutions for Sustainable Offshore Wind Development. Earth Science, Systems and Society 2021, 1. [CrossRef]

| (m/s) | 9,78 | 9,78 | 9,83 | 9,20 |

| (m) | -549,98 | -389,48 | -359,60 | -732,43 |

| (m) | 2,50 | 2,60 | 2,60 | 2,60 |

| (km) | 11,63 | 10,53 | 11,14 | 13,75 |

| (GWh) | 2738,20 | 1.194,50 | 1.205,40 | 1.100,80 |

| (Mdd) | 2.927,93 | 1.716,08 | 1.715,15 | 1.714,96 |

| (Mdd) | 65,63 | 27,00 | 27,00 | 27,00 |

| (%) | 3,81 | 1,99 | 1,96 | 1,95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).