1. Introduction

We live in an age of uncertainty. Before COVID-19, the standing list of complex global issues included: increasing economic disparities, geopolitical instability, diminishing democratic values, wavering social cohesion, and a looming climate crisis [6,66,92,98]. Now we find these issues have become exacerbated and in need of more urgent attention [98]. Complex issues must be addressed, not only for their inherent risks but also because they can hamper essential progress toward achieving societal sustainability [6,66,98]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were developed to urge the world to act on a number of complex issues related to sustainability [87]. The SDGs are a set of 17 global goals adopted by the UN member states in 2015, aiming to address various social, economic, and environmental challenges by the year 2030. However, given the complexity within and across the entire 17 goals, there is a need for capacity building if progress is to be made in a timely manner. Education has a crucial role in all of the SDGs and specifically SDG-4, quality education. Higher Education (HE) is particularly important as this is the stage of life where students are preparing for their future roles in society [17,18] as cited in [78]. Students must be competent in various areas when they graduate so they are prepared to assume roles and responsibilities in their professional lives. Generally, we say someone is competent when they have the ability to do something well. In education, competencies are defined as “a complex combination of knowledge, skills, understanding, values, attitudes, and desire which lead to effective, embodied human action in the world in a particular domain” [15, p. 312]. Core or key competencies are the ones that bring about the essential behaviors expected by a particular organization or in a specific situation [86].

Education is being called upon to adopt key Sustainability Competencies (SCs) that advance one’s capacity to understand and address sustainability and other complex problems in higher education institutions (HEIs) [1]. SCs would be taught alongside traditional competencies that strengthen students’ cognitive/intellectual capacities [1,62].

Blending the traditional competencies with SCs that build personal/emotional strengths for real-life issues and challenges represents a more holistic approach to management education (ME). By mastering both intellectual and emotional competency, graduates are not just better prepared to make sustainability-minded decisions but also are equipped to manage other complex challenges that arise [66,68,92]. SCs also foster an ethical mindset that facilitates a broad understanding of the complexity and interconnectedness of the world today [24,37,43]. The student who is both intellectually and emotionally competent is prepared to solve complex issues that go beyond the sustainability context, making their adoption highly practical for students of all disciplines [66,92].

However, despite their unique position as change agents for sustainability, HEIs have not promoted SCs to any significant degree [4,25]. Multiple international efforts have been launched to coax the education system to move forward with sustainable practices and programs, but rather than transformative change, we see limited progress within single institutions or one faculty or program [1,5,46]. Progress on the SDGs has grown in business schools since the appearance of the Times Higher Education (THE) Impact Rankings [73]. However, the majority of schools are not engaging in the process and there is a notable absence of high-ranking global universities. Furthermore, if the universities involved are not embedding sustainability into core programming or across disciplines, their efforts towards sustainability will tend to be superficial [7,94].

To stimulate policy action that will mandate SCs in HEIs we focus our attention on business students as a subset of all HEIs. We do this for specific reasons. Business is often criticized for its neglect of societal issues and business schools have been held responsible for their part in producing executives whose unethical decisions and unsustainable practices have led to the corporate scandals that have become commonplace [1,5,46]. As a result, business schools are undergoing pressure to develop future managers and leaders who will make responsible decisions and have a positive impact on society [23,78]. We believe the challenge to integrate ESD and adopt SCs in curricula may provide a genuine opportunity for business schools.

While a compelling proposition, there are barriers to moving forward with integration. In business schools, ME continues to reflect the long-standing economic paradigm of shareholder value and the pursuit of profit, often glossing over or even completely neglecting societal issues and impacts [82]. Furthermore, the ESD literature reveals confusion and an ongoing debate about what the SCs should look like and how to integrate them into the curricula, stalling any real progress [4,6,19,31,55,70]. Interestingly, our study will show that not only are there key competencies available, but also recent papers (2019-2023) clearly refer to the competency framework developed by Wiek et al. [96] and the updated version [62] as the leading instrument in the ESD field [2,10,20,22,47,62].

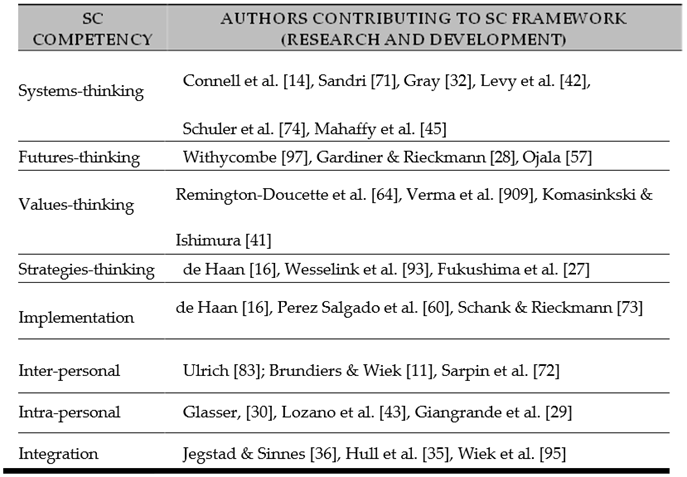

Table 1 shows the eight competencies included in the 2021 version of Redman and Wiek’s SC framework [62]. See Table 2 for the scholars whose work has been incorporated into the overall framework, a clear demonstration of unity among scholars throughout the ESD field.

The purpose of the study was to raise awareness of the impasse in adopting ESD and SCs in education by providing evidence of scholarly consensus around a specific SC model that could be implemented if the appropriate decisions were made to move forward. We also outlined some of the main barriers within institutions that jeopardize progress and then we responded with potential solutions. Given the prominence of business in society and the continued calls for change in business principles and practices, we proposed that business schools become the change agents for other HEIs, leading the integration transformation [1,24,65,79]. The paper highlights SDG-4 (quality education) and the enhancement of ESD, in this case, adopting competencies for sustainability in business programs and other HEIs. Since ESD is recognized as a natural and essential connection to all SDGs, we also described potential gains for other goals should decisive action for integration be taken.

The scoping review process is defined in the following section. The findings are identified in the scoped literature review that follows, and a thematic analysis has been conducted to interpret the literature and provide meaning. The discussion reaffirms the findings and provides essential information for possible action. Throughout the paper, we underline the urgency in equipping students with the competencies to effectively address complex problems like the SDGs and other global issues.

2. Research Methods: Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis

Scoping Reviews (SR) systematically scope out or map the literature available on a topic; the aim is to provide an overview or map of the evidence. On the contrary, systematic reviews follow a formal process of methodological appraisal to determine the quality of that evidence [39,59]. SRs also draw on various research methodologies and may include non-research sources, like policy [55]. There has been a steady increase in scoping reviews since 2012 [81].

Authors deciding between the systematic review or scoping review approach must consider the reasons for using a scoping review and identify the research question and purpose of [51]. Here we have sought evidence for an appropriate SC model that could break the SC integration impasse and point to the absence of policy and other key barriers that are preventing progress. This SR is intended to increase awareness and provide guidance for possible future action. In the event that a policy or other comprehensive framework becomes feasible, a systematic review may be necessary for which this SR may serve as a precursor [51].

The scoping method is increasingly used to inform decision-making and research based on a particular topic or issue. To ensure rigor and transparency, a series of systematic steps have been employed; the process is based on the guidelines of the JBI Scoping Review Methodology Group and endorsed by JBI’s International Scientific Committee in 2020 [51,55].

2.1. Steps in the Review

We used the five-stage framework recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [3] as our approach, namely, (1) identify the research question, (2) identify relevant sources, (3) study selection, (4) chart the data, (5) collate, summarize, and report the findings.

Step 1: Research Question(s)

The research question has two parts: What is the essential evidence to support implementing SCs in HEIs? and (2) What are the key barriers that continue to prevent implementation and how can they be overcome?

Step 2: Indices, Databases, and Search Engines

We used the automated citation index Google Scholar to pilot the search strategy and provide some indication of the potential size of the response [3]. The number and expansive nature of the findings directed our focus to high-impact journals that offered more robust search capabilities. Two clear areas of study were highlighted in the initial pilot: education and environment. The library indices selected were Education Source Complete and Environment Source Complete. The Education Source Complete database includes educational research and policy studies. The Environment Direct database was selected to ensure coverage of sustainability-related literature. Each of these library indices provided access to several related databases that added to the comprehensiveness of the search.

2.2. Search Process

The timeframe for the search was 2011-2022 (plus a few papers that emerged in 2023 as the paper was being written). After multiple consultations, we chose the starting date of 2011, given the release of the UN’s Learning for the future: Competences in education for sustainable development [84]. This was followed by another significant publication, Wiek et al.’s [96] paper titled, Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. The SCs recommended in Wiek et al.’s [96] paper are highly regarded in the literature. Furthermore, the paper is the most cited in the sustainability competency segment of the field and has been used as a foundation for numerous research studies (e.g., interviews) [20,22,62].

Researcher #1 was responsible for the search process, maintaining records so that consultations could be held at key points. Researcher #1 ran the first series of searches that were purposefully broad, including ESD (and synonyms) in the search string to ensure the capture of anything relating to learning objectives that might inform the specific area of competency. This resulted in far too many hits but provided us with an understanding of the interest in the subject and the general tenor of the discussions. After consulting with Researcher #2, the next series of searches removed ESD (and synonyms) and focused on SCs. The final search string used was sustainability leadership, sustainability competencies (SCs and synonyms provided by the relevant search engine), higher education institutions (HEIs and synonyms provided), business schools or colleges (and synonyms provided), and reviews of literature (and synonyms provided). The final search yielded 92 hits, a more manageable number and much-improved accuracy. Both researchers were satisfied with the number of hits.

Step 3: Study Selection

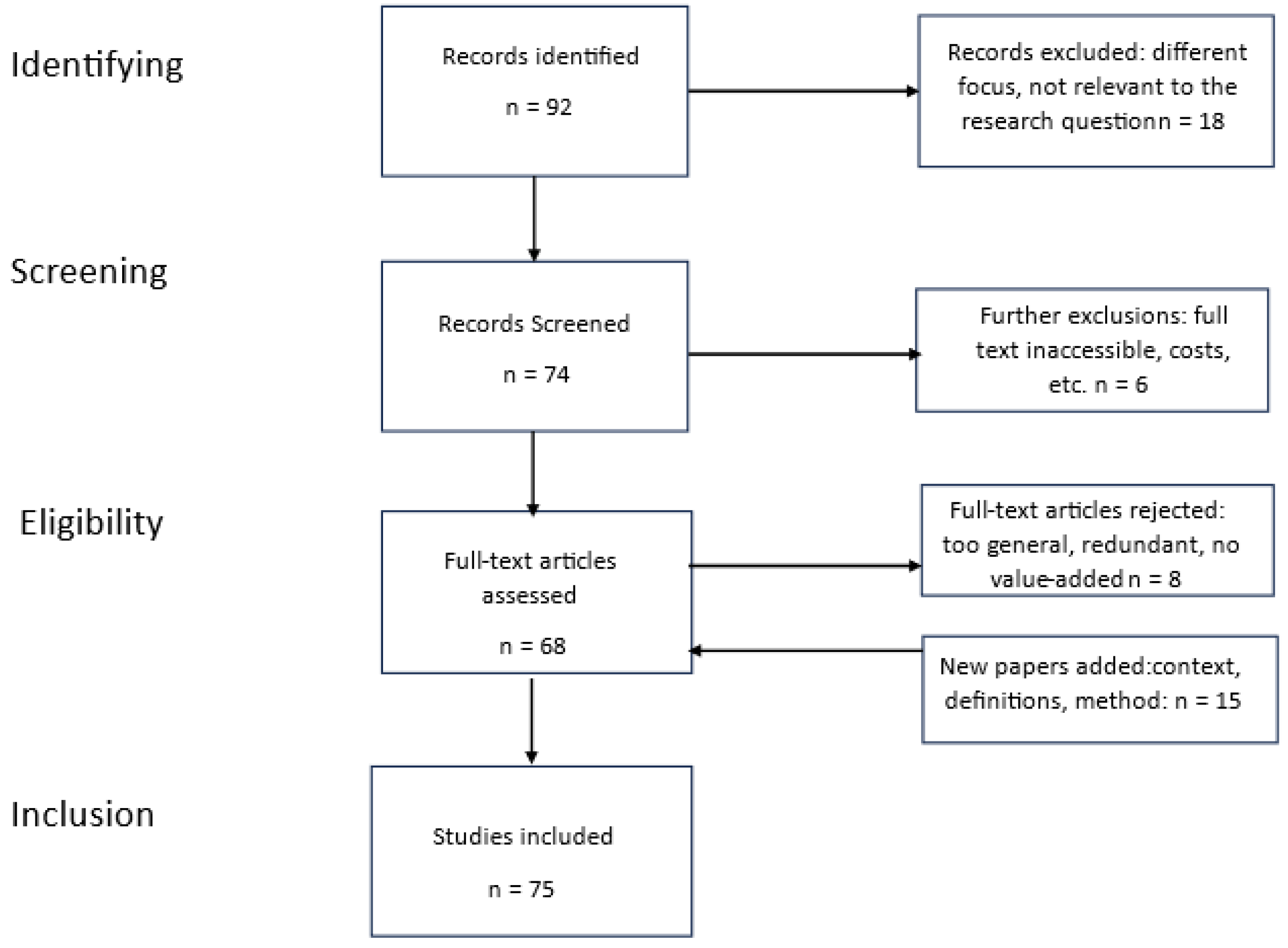

The third step involved several mini steps so that the best papers were included. Both researchers performed the initial screening based on abstracts and noting reasons for excluding each paper. They then consulted to discuss and agree on a common set. The format was restricted to full-text print and open-source peer-reviewed English publications; excluded were duplicate entries, most books, most theses, and obscure references. The number assessed by both researchers was 68 papers.

Researcher #1 was responsible for conducting the thematic analysis and regular discussions were held as the themes were developed. The final themes were agreed to by both researchers. Researcher #1 was responsible for the first draft. A number of articles were added as the paper was being developed to respond to background/context, to seek more in-depth information about important concepts, to inform the methods section, and to inform the discussion. Once rejections and new additions were tallied, 75 studies were included (See

Figure 1.)

Steps 4 and 5: Charting the Data and Summarising the Finding.

In the final steps of the process, Researcher #1 mapped the data, and the findings were interpreted applying a themes analysis. Thematic analysis is a method or practice used throughout a variety of disciplines [50]. There are both deductive and inductive approaches to thematic analysis; we used the inductive approach, and each researcher worked their way through the six steps for social science outlined by Braun and Clarke [9]: (1) become familiar with the data, (2) generate codes, (4) review themes, (5) define and name themes, and (6) locate exemplars. Researcher #1 shared a first draft of the analysis with Researcher #2 for review and consensus on a final grouping was reached.

This approach yields a snapshot in time, and we acknowledge that some inconsistency may be present in how keywords are used. The next section reflects the relevant scoped literature (2011–2022). We then discuss the findings to clarify the state of SC implementation and to offer suggestions to overcome deemed barriers to change.

3. Themes Emerging from the Scoping Review

HEIs, including business schools, are responsible for delivering education for sustainable development (ESD) by raising awareness and providing the necessary competencies to manage complex problems such as sustainability [66]. The problem is that progress in adopting SCs in educational programs has been slow and lacking in coordination. There are several reasons for the delay, but the key issues are the ongoing debate among academics regarding what the actual competencies should look like and how to adopt them in educational programs [96]. As we proceeded with the scoping review, other reasons for not proceeding with broad-based implementation of SCs emerged that are detailed in 3.10.

The following are the key themes that emerged from the review. They define and inform the concepts and challenges relevant to implementing a coherent model for integrating SCs in business schools and other HEI programs.

3.1. Complex Real-World Problems and the UN SDGs (2015)

Complex issues lack clear definitions and may not be able to be solved through traditional methods and decision-making [92]. The issues and challenges we face in the 21st century are complex and urgent; many are unprecedented and can even pose an existential threat to our health and well-being as a society [66,98].

A global approach to many of these complex issues is provided by the UN’s framework for the 17 SDGs (2015). Each of these goals either represents a globally complex issue (e.g., climate action) or is interlinked with one or more of the others (e.g., sustainable economic growth). Achieving progress on these goals brings us closer to sustainability.

3.2. Sustainability

As a concept, “sustainability” is based on the understanding of sustainable development established in Our Common Future [12]. Sustainability is a complex issue of mega proportions. Sustainability challenges involve almost every aspect of society and are among the main concerns of the world today [92]. The framework provided for the 17 SDGs is a type of blueprint for achieving sustainability by addressing the complex issues that comprise each goal. Progress is also possible by managing other complex issues that interconnect with sustainability [49,66]. In other words, effectively managing real-world complex issues, like the ones relayed earlier in the paper, is aligned with progress toward sustainability.

Sustainability is at risk given the growing number of complex issues that require urgent attention [6,92]. Business is expected to support efforts to achieve sustainability but has been lagging in this role [66]. Urgent action is needed from corporate managers and leaders who are capable of understanding and accepting broad responsibility for their actions and society. However, this will require values, knowledge, and skills that are different from those typically demonstrated in business, particularly corporations, today [53].

3.3. Why SCs should be implemented: Different Competencies Required for Complex Issues

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated already existing challenges and increased the urgency to find solutions [6,66,98]. There are continued demands from society for business, particularly big business, to be more involved in these issues and to help address them [89]. A heightened demand for a different type of businessperson has emerged, one who is more ethical, responsible, and sustainability-minded [1,51,53].

Business must be more accountable. The financial crisis of 2008-2009 was a prime example of corporate greed and hubris [1,5]. Corporate scandals and other misbehavior began well before 2008; what is noteworthy is that they continue to this day, supporting the need for change in how business operates [5]. Corporate executives in power today were taught the principles and practices of the dominant economic model in business programs, shareholder capitalism [77,79]. However, business students can be educated to be different and to have values, knowledge, and skills that lead them to accept greater responsibility for societal problems to which their corporations often contribute.

3.4. Competencies for Sustainability and Other Complex Issues

Competencies in education became popular more than two decades ago through efforts such as the OECD-led initiative on the Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) [69]. Today incorporating SCs in HE has become more urgent as societal issues have grown and intensified [6,62]. SCs emphasize personal/emotional factors relating to human elements like judgment, ethics, and morality [5,82]. Such competencies help students to self-regulate their emotions and engage in interpersonal relationships, enabling them to be more considerate of the needs of others [31]. SCs are intended to complement the traditional competencies that are already compulsory for business and other professions and programs, such as critical thinking and basic communication skills. The increased emotional intelligence helps students who enter the business world to become more adept at solving complex problems that involve many systems, structures, and stakeholders [49].

3.5. Effectiveness of SCs

Businesses are being challenged to respond to the many complex issues in the world today and corporate managers and leaders are expected to build sustainability into the solutions they put forward [21,54]. There is ample evidence for expanding management programs to integrate sustainability and SCs into curricula. For example, Griswold [33] found that students who engage in sustainability education continue to demonstrate sustainability in their professional careers. Wang et al. [91] examined the delivery process for sustainability courses and found that, depending on how the courses were taught, students’ beliefs in sustainability practices were affected and this helped in forming sustainability mindsets. Their findings further indicate that systematically linking pedagogies to teaching practices enhances students’ success in developing a sustainability mindset along with appropriate competencies for sustainability management. Caldana et al. [13] demonstrated how a hybrid learning approach that involves formal and informal learning is an effective way to educate future responsible leaders while maximizing the development of SCs.

In contrast, empirical research clearly shows the inadequacies of current business management programs regarding sustainability awareness and real-world preparedness. Studies in various university business programs found that the current curriculum supports and builds competency in the so-called generic or “hard” skills (e.g., assessing, analyzing, and evaluating) and reduces students’ responsiveness to “softer” skills and behaviors that are needed for a sustainability-minded manager/leader (e.g., general empathy, self-reflection, collaboration) [1,47]. For example, Marathe et al. [46] conducted a study of a current two-year, full-time MBA program—when students entered and again when they graduated—that indicated the impact of ME on cognitive and affective empathy. The authors reported a positive impact on cognitive empathy, but a reduction in affective and general empathy when the students graduated from the program.

Next, we scoped out the state of the literature regarding the ongoing debate and the evidence to support a specific framework or model for implementing the SCs across HEIs.

3.6. Ongoing Debate Among Academics

The scoped literature includes many studies in which scholars continue to study and publish papers that present SCs for education, many of which are variations on existing competencies. They also have a variety of thoughts on how to adopt SCs in educational programs. However, contrary to this commonly expressed theme, the scoping review pointed to consensus among scholars, as well.

3.7. Convergence

While a continuous stream of SCs—mostly reinvented—appears in the literature, there is also substantial convergence on an existing framework [10,20,26,62], namely, Wiek et al.’s 2011 paper titled, Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development [96].

3.8. SC Framework, Version 1.0

The 2011 framework is a synthesis of the literature up to 2011 and recommends five key competencies: systems-thinking, anticipatory, normative, strategic, and interpersonal competence. This framework has received the most citations by far of any similarly focused research and has been recognized as “the most influential paper” in a bibliometric review of ESD research from 1992 to 2018 [34]. The framework has also been applied in research interviews [20] and as a guide for students working with the 2015 SDGs [77]. Its status as a leading work continues with the updated and even more comprehensive version of the framework released by Redman and Wiek in 2021 [62], Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. We refer to this newer framework as Version 2.0.

3.9. SC Framework, Version 2.0

In 2021, two of the authors of the first SC framework (Version 1.0) updated and expanded the 2011 paper. Redman and Wiek [62] conducted a systematic review relevant to ESD and sustainability and found a high level of convergence in the SCs put forward by various scholars over the previous decades (1997-2021). Therefore, even though a number of scholars continue to focus on inventing and reinventing competencies, there is evidence of a cooperative effort among scholars as early as the 2011 paper.

In the new version, the authors expand on the five key competencies presented in 2011, adding three new competencies based on their synthesis of studies done since 2011: intra-personal, implementation, and integration competence. The 2021 competencies are displayed in

Table 1.

3.10. From Convergence to Agreement

Scholars have demonstrated their unity in various ways: contributing to each of the competencies (see

Table 2), making statements in support of the work of Wiek and colleagues in the literature, and applying both frameworks in academic and practitioner environments [2,10,20,22].

Convergence tends to approximate agreement in the narratives of recent scholarly papers, specifically Annelin & Boström [2], Brundiers et al. [10], Eberz et al. [20] and Evans [22]. Each of these authors selected the framework of Wiek et al. [96] or the more recent framework of Redman and Wiek [62] as foundational for their studies. These studies demonstrate the broad application of the framework, as authors have applied it successfully in sustainability program development [10], in the pairing of pedagogies to specific competencies [22], as an application with decision-makers in a variety of fields [20], and with the development of assessment tools to measure students’ sustainability competence.

3.11. Institutional Barriers Preventing Implementation of SCs

Even if academics agreed on one SC model, there may not be sufficient interest or resources to effect the necessary changes in HEIs, including business schools. The following categories include the main barriers within institutions that stand in the way of broad integration of SCs in HEIs and are the most often reflected in the literature. Invariably there are more, and the lines between the categories may blur, however, the aim is to provide sufficient evidence to respond to the research question and purpose of the study.

3.11a. Ill-Prepared Organizational Structure. Sekhar [75] noted that organizational barriers are the most frequently mentioned barriers in the literature. Although HEIs have been vested with the responsibility to teach sustainability internally and to share their knowledge with businesses and the community, progress has been limited [38,70]. Sanchez-Carrillo et al. [70] reported that HEIs have tended to focus their sustainability efforts on environmental concerns at the loss of other more meaningful sustainability-minded improvements that include reaching out to businesses and communities to discuss changing needs.

Mader et al. [44] identified the absence of policy and practical frameworks focused on integrating ESD into HEIs as a major challenge and vitally important to ensuring ESD is successfully implemented and sustained within the institution. In many institutions, senior leaders are reticent to support new initiatives without proper direction and the means to secure resources [8,23,88]. As a result, the sustainability concept is more likely to be included on a piece-meal basis, within specific disciplines and based on individual educators who have little or no connections to the other disciplines or the institution as a whole. Moreover, obtaining funding for sustainability courses can be challenging for individual educators when the concept is not a priority in education [23,88].

Business Schools, as other HEIs, have been slow to make changes to the curriculum, and the systems and structures that are needed to support sustainability [1,5,79]. Current accounts of ESD in business schools show that some schools have included sustainability and/or ethics courses in management programs, but there is a lack of coordination and courses tend to be unique or standalone instead of integrated across the discipline [76]. Bates et al. [6] noted that an issue as simple as understanding concepts, like competence and sustainability, may be slowing progress within and across disciplines.

Some progress has been noted regarding an increasing number of universities that have begun to participate in THE Impact Rankings (2023). While this is encouraging, there are many universities, especially high-ranking schools, that have yet to become involved. Furthermore, some controversy has risen regarding how effectively the university results address the SDGs as the same schools continue to be slow to adopt sustainability principles and practices in any profound way [7,94].

3.11. b. Need for Sustainability Training and Other Supports for Educators

A lack of knowledge about sustainability persists in HEIs, along with no consensus on what to teach and how [44]. Confusion reigns with regard to terminology for sustainability, as well. Both the terms sustainable development and sustainability share a lack of clarity of meaning, and this adds to the confusion [75]. Verhulst and Lambrechts [76,89] say that the lack of resources (human, financial and material) needed to develop transdisciplinary initiatives and experiential learning presents another challenge to integration. Teaching tools, such as business games, consist of an alternative to develop critical and reflective thinking in students, not requiring additional financial resources such as those required for experiential learning.

From a business perspective, teaching sustainability and building a culture that values and rewards sustainability has great merit, but also presents problems for educators. Managing to balance the environment, economy, and society poses additional challenges as shareholder capitalism has dominated the principles and practices for decades [77,79].

3.11. c. Restructuring Curricula

Should a university decide to change the curriculum to add new competencies for sustainability, the same teaching methods may not be appropriate. Pedagogical approaches require change so that students are more involved in the teaching processes and more emphasis is placed on practical opportunities for them to learn. Furthermore, ethical principles are foundational for learning and honing new competencies for sustainable decision making [99].

3.11. d. Additional Barriers

The need to enhance sustainability courses and measuring performance and effectiveness were also listed as barriers. They will be addressed in the Discussion.

4. Why Focus on Business Schools?

Business schools and educators used to prepare students for challenges related to business AND society but by the mid-1980s, they narrowed their focus to maximizing profits for shareholders. As delivering shareholder value became the singular purpose of business, business schools adapted to the change [5,48]. Currently, even when business programs include courses that discuss stakeholder theory as an alternative paradigm, the lack of integration across the discipline tends to be more confusing than enlightening to students. If the behavior of corporate managers and leaders is to change, the process must begin in the educational system [5].

4.1. Business Schools Need Transformative Change Now

Business schools continue to use a teaching model for ME that dates back to the late 1950s [82]. As the demands for businesses to be more involved with complex societal issues continue to grow, business schools are becoming dated [5,67,82]. Consider for example, that in 2019 the Business Roundtable changed its long-standing commitment to maximizing shareholder value to stakeholder capitalism [67]. The competencies that align with the shareholder approach are cognitive/intellectual, not personal/emotional. Students become experts at analyzing, evaluating, and assessing, but lack inter-/intra-personal qualities that generate empathy and collaboration [70]. The slow pace of change in curricula and pedagogy means that students are increasingly ill-prepared for sustainability and other complex challenges they will face in the real world [4,25].

4.2. Urgency Continues to Grow

The state of the world has greatly changed, with an increasing number of societal issues that need solutions [82]. The pressure on business schools to change has been increasing as well, given the need for new knowledge and skills to solve complex issues [40,46,67,82]. Annual global surveys of trust and credibility in institutions have continued to indicate that people want more engagement from businesses, particularly around societal issues like climate change and economic inequality [21].

Students are changing, too. Younger generations of students are demanding new systems and programs that emphasize different mindsets and competencies, especially competencies relevant to sustainability values and social responsibility [79]. Educators and administrators must understand the urgency of being competent in multiple areas that typically have not been emphasized in business school programs to date [76,82].

4.3. Societal Feedback

Annual global surveys of trust and credibility in institutions have continued to indicate that people want more engagement from businesses, particularly around societal issues like climate change and economic inequality [21]. Business schools can kickstart the change in curricula for all HEIs by offering new competencies to students who will become the corporate leaders of tomorrow and integrating sustainability concepts across the discipline.

5. Discussion

The research question for this study focussed firstly on identifying the evidence that debunks the ongoing perspective in the literature that there is not an appropriate model for SC implementation in existence, and secondly, on an overview of the barriers to implementation and how they can be overcome. The reasoning behind the study has been to raise awareness and present guidance for future action.

5.1. An Appropriate Model for SC Implementation Exists

While an impasse still exists in the literature regarding advancing SCs in HE curricula [4,6,19,31,55,70], the scoping review provided clear evidence that a substantial number of scholars and practitioners have converged around a particular framework, using it as a foundation and guide for their work [2,10,20,22,47,62]. We point to this unity as a deciding factor in moving towards broader implementation of the SCs.

Next, we provide some guidance, based on the literature and the authors’ academic experience in sustainability coursework, to help researchers and practitioners to take the next step in advancing the integration of SCs in business schools, the second objective of the RQ. At this stage, barriers must be overcome that involve academics, practitioners, as well as business.

5.2. Main Barriers to Implementing SCs.

A number of scholars believe sustainability adoption has had sufficient time to be researched and understood and should be broadly integrated into educational programs now [4,11,20,58,62]. As no high-level policy has been announced to date [48] and no guidance is included in SDG-4 (4.7) which calls for global ESD [62], we lay out the key barriers to action previously indicated in the scoping themes and offer some actionable steps to overcome them. This section addresses all HEIs, with some specific notations for business schools.

5.3. Response to HEIs’ Ill-Prepared Organizational Structures

As organizational barriers are the most frequently mentioned in the literature, they should receive immediate attention if integration were to proceed in the future. If change is to occur, the institutions that deliver the educational programs must support and demonstrate commitment to integration.

Mader et al. [40] noted the importance of policy and frameworks as important resources for administrators. Figueiró and Raufflet [23], Velazquez et al., 2005 [88], and Blanco-Portela et al., 2017 [8] all noted that without policy direction from an appropriate body, we will continue to see a lack of support for SCs from senior leaders within HEIs. Furthermore, without policy direction and standards for implementing and sustaining the transformation, the sustainability concept is likely to continue to be included on a piece-meal basis, in specific disciplines and based on individual educators with no connection to the other disciplines or the institution as a whole.

Administrators are also responsible for securing resources and for setting the change management parameters within the faculty that insures continuous involvement in the change efforts. Managing the many diverse interests of different disciplines and groups within the institution is also necessary [73]. Moreover, obtaining funding for sustainability courses can be challenging for individual educators when the concept is not a priority in education [23,88] in [76]. Once support and resources have been awarded, faculty must be involved in the change efforts, and the many diverse interests of different disciplines and groups within the institution must be managed.

5.4. Response to the Need for Sustainability Training for Educators.

A lack of knowledge about sustainability persists in HEIs, along with no consensus on what to teach and how [44]. Confusion reigns with regard to terminology for sustainability, as well. Both the terms sustainable development and sustainability share a lack of clarity of meaning. and this adds to the confusion [75]. The existence of appropriate models for implementation of SCs must be promoted so that there is an appropriate level of awareness among educators and their senior leaders

From a business perspective, teaching sustainability and building a culture that values and rewards sustainability and SCs has great merit, but also presents problems. Managing to balance the environment, economy, and society poses additional challenges for future leaders. The SCs provide a mechanism for students to understand and practice how the balancing act can be managed in an ethical and responsible manner.

5.5. Response to Providing Ongoing Educational Supports.

It is imperative that we continue to build educators’ capacity to be successful in teaching students about sustainability [58]. There is growing acceptance of the competencies that educators should possess and the pedagogies to employ, but a deficit can still be observed in terms of educators’ capacity to teach students about sustainability [4,57,85]. Bates et al. [6] included the potential lack of understanding of the concept of sustainability and how to teach it as a major stumbling block for integrating ESD. Verhulst and Lambrechts [89 in 76] reinforced the need for supports, noting that human, financial, and material supports are required to develop transdisciplinary initiatives and experiential learning.

5.6. Response to Restructuring Curricula.

Should a university decide to change the curriculum to add new competencies for sustainability, the same teaching methods are not necessarily appropriate for sustainability programs. Pedagogical approaches should involve students in the teaching processes and more emphasis is to be placed on practical opportunities for students to learn and practice the SCs. Furthermore, ethical principles are foundational for learning and honing new competencies for sustainable decision making [98].

In business schools, this barrier can be particularly difficult due to the continued reliance on shareholder management as the theme in ME [77,82]. As noted earlier in the paper, business schools and educators must work to achieve greater alignment with a different theory of management, that of stakeholder management [77,82]. The changes must be applied across the discipline as well as throughout the curricula of other disciplines so that students see and understand that stakeholders must be valued and engaged as future managers and leaders.

5.7. Response to the Need to Enhance Sustainability Courses.

More sustainability courses should be added to ME and an integrated approach must be advanced across the disciplines. The more visible sustainability is throughout the institution, the more it will be seen as legitimate. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that students are better prepared when sustainability is embedded in their everyday coursework and in a way that is useful and relevant to them [94]. The urgency for change is even more relevant in business schools, where ME is criticized for producing managers and future leaders who have been involved in unsustainable and unethical business decisions and practices that have led to an ongoing list of corporate scandals [1].

5.8. Response to Measuring Performance.

Students’ readiness to understand and master the new competencies and their success in acquiring the competencies is an area of sustainability education that continues to develop [62]. However, Singh and Segatto [76] noted that there is a lack of standardization and coordination. The process must be reliably measured to ensure that positive results are being achieved. Once a singular model for SCs has been approved for integration, scholars can focus their evaluation efforts on the standardized measures and ensure effectiveness and continuous improvement.

The systematic review by Redman et al. [62] (and the model around which consensus has formed) provides guidance for educators interested in knowing more about assessing students’ competencies in sustainability. The authors provide an overview of over 120 assessment tools currently in use and organize them into eight categories: scaled self-assessment, reflective writing, scenario/case test, focus group/interview, performance observation, concept mapping, conventional test, and regular coursework. Researchers and scholars can help by generating more evidence about what works best in practice so assessment tools can continue to improve.

6. Implications and Limitations

Business schools have been selected to lead the transformation process for all HEIs. This is a strategic decision, on our part, to kickstart changes within one discipline for which there has been increasing demand for change in the educational curricula [4,25]. Eventually, all HEIs should proceed with a full transformation.

We recognize that extensive engagement and collaboration will be required to bring forward a policy and implementation process to integrate SCs into business schools and other HEIs. The scoping review serves to increase awareness of what is currently available in terms of a model for implementing SCs and offers guidance on the next steps that can be taken to assist with barriers that are impeding forward movement. A systematic review may be required to inform the policy and the requisite standards. We recognize the challenges this poses yet ask readers to consider the positive results that can be achieved for generations.

Integrating SCs into mainstream ME makes it possible to foster management behavior that is more ethical, responsible, and sustainability minded [1]. Business and other graduates will be better equipped to work effectively with stakeholders and more open to sharing responsibility for sustainability and other complex societal issues. We believe establishing the programs that will facilitate a different, more sustainability-minded leader will more than compensate for the efforts expended. Furthermore, business schools as change agents are in a position to set the bar high for the remaining HEIs while responding to societal demands for greater responsibility.

7. Conclusion

We live in uncertain times, with numerous complex issues needing urgent attention and a changing world order that threatens our sustainability on multiple levels [6,66,92,98]. As we continue to recover from a deadly pandemic, we must make the time and space to consider how we educate future managers and leaders.

In this paper, we explored the state of the ESD literature regarding SCs and whether a credible model existed—one that has been sufficiently developed, refined, and tested—and that could be implemented broadly across HEIs, starting with business schools. Currently, no policy decision or action plan to integrate SCs into HEIs has been forthcoming, even though SDG-4 (quality education) is an important goal within the 2015 SDGs. Much of the impasse is related to a persistent theme in the literature that points to a lack of agreement around the competencies to be selected. Despite this interpretation, our scoping review provided evidence of substantial scholarly convergence around the SC framework first developed by Wiek et al. [96] and updated in 2021 [62]. Our review also identified key barriers that tended to stall integration in the institutions, prompting us to explore possible solutions and approaches that could overcome these issues.

We hope we have raised awareness of the work that has been accomplished by key scholars in developing a model for implementing SCs in HEIs. The paper may contribute to further action needed to coordinate policy and implementation planning. The scoping review may then serve as a precursor for a systematic review that will inform future policy and establish standards for comprehensive adoption of SCs in business schools and all HEIs.

SCs impart the core values, knowledge, and skills needed for the complex world we live in now [54]. Integrating them into ME fosters a new breed of business graduates who are more likely to support and promote sustainability and be better prepared to address other complex real-world issues that they will face. On a strategic level, taking the lead on integrating SCs in ME provides business schools with an opportunity to honor a long-standing but discounted commitment to deliver graduates whose responsibility is to both business and society. They could also contribute to significant SDG progress and kickstart the much-needed ESD transformation in HEIs around the world.

References

- Abdelgaffar, H. A. A review of responsible management education: practices, outcomes and challenges. J. Manag. Dev., 2020, 40 (9–10), 613–638. [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A., & Boström, G.-O. An assessment of key sustainability competencies: a review of scales and propositions for validation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2023, 24(9), 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol.: Theory Pract., 2005, 8(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Aung, P. N., & Hallinger, P. Research on sustainability leadership in higher education: a scoping review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2022, 24(3), 517–534.

- Bagley, C. E., Sulkowski, A. J., Nelson, J. S., Waddock, S., & Shrivastava, P. A path to developing more insightful business school graduates: A systems-based, experimental approach to integrating law, strategy, and sustainability. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ., 2020, 19(4), 541–568.

- Bates, R., Brenner, B., Schmid, E., Steiner, G., & Vogel, S. Towards meta–competences in higher education for tackling complex real–world problems—a cross disciplinary review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2022, 23 (8), 290–308.

- Bautista-Puig, N., Orduña-Malea, E., & Perez-Esparrells, C. Enhancing sustainable development goals or promoting universities? An analysis of the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2022, 23(8), 211–231. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Portela, N., Javier Benayas, J., Pertierra, L. R., & Lozano, R. Towards the integration of sustainability in Higher Education Institutions: A review of drivers of and barriers to organisational change and their comparison against those found of companies, J. Clean. Prod., 2017, 166(10), 563-578.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol., 2006, 3, 77–101.

- Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G., Cohen, M., Diaz, L., Doucette-Remington, S., Dripps, W., Habron, G., Harré, N., Jarchow, M., Losch, K., Michel, J., Mochizuki, Y., Rieckmann, M., Parnell, R., Walker, P., & Zint, M. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci., 2021, 16(1), 13–29.

- Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. Beyond Interpersonal Competence: Teaching and Learning Professional Skills in Sustainability. Edu. Sci., 2017, 7(1), 39. [CrossRef]

- Brundtland Commission. Our common future. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Caldana, A. C. F., Eustachio, J. H. P. P., Lespinasse Sampaio, B., Gianotto, M. L., Talarico, A. C., & Batalhão, A. C. da S. A hybrid approach to sustainable development competencies: the role of formal, informal and non-formal learning experiences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2023, 24(2), 235-258.

- Connell, K. H., Remington, S., and Armstrong, C. Assessing Systems Thinking Skills in Two Undergraduate Sustainability Courses: A Comparison of Teaching Strategies. J. Sustain. Educ., 2012, 3.

- Crick, R. Key Competencies for Education in a European Context: narratives of accountability or care. Eur. Educ. Res. J., 2008, 7. [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. The BLK ’21’ Programme in Germany: a ’Design Competence’-based Model for Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Edu. Res., 2006, 12, 19–32.

- de Lange, D. E. How do universities make progress? Stakeholder-related mechanisms affecting adoption of sustainability in university curricula. J. Bus. Ethics., 2013, 118, 103-116.

- Disterheft, A., Caeiro, S., Azeiteiro, U. M., & Leal Filho, W. Sustainability science and education for sustainable development in universities: a way for transition. In Sustainability assessment tools in higher education institutions: Mapping trends and good practices around the world, Caeiro, S., Filho, W., Jabbour, C., Azeiteiro, U. Eds; Springer International Publication, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 3-27.

- Dzhengiz, T., & Niesten, E. Competences for environmental sustainability: A systematic review on the impact of absorptive capacity and capabilities. J. Bus. Ethics., 2020, 162(4), 881–906.

- Eberz, S., Lang, S., Breitenmoser, P., & Niebert, K. Taking the lead into sustainability: Decision makers’ competencies for a greener future. Sustainability, 2023, 15(6), 4986.

- Edelman Trust Barometer. Global report. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2023/trust-barometer (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Evans, T. Competencies and pedagogies for sustainability education: A roadmap for sustainability studies program development in colleges and universities. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 5526.

- Figueiró, P. S. & Raufflet, E. Sustainability in higher education: a systematic review with focus on management education. J. Clean. Prod., 2015, 106, 22.

- Filho, N. de P. A., Hino, M. C., & Beuter, B. S. P. Including SDGs in the education of globally responsible leaders. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2019, 20(5), 856–870. [CrossRef]

- Filho, W., Eustachio, J. H., Caldana, A. C., Will, M., Lange Salvia, A., Rampasso, I. S., Anholon, R., Platje, J., & Kovaleva, M. Sustainability leadership in higher education Institutions: An overview of challenges. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 9.

- Frank, P. A proposal of personal competencies for sustainable consumption. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2021, 22(6), 1225–1245. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y., Ishimura, G., Komasinski, A. J., Omoto, R., and Managi, S. Education and Capacity Building with Research: a Possible Case for Future Earth. Int. J. Sus. Higher Ed., 2017, 18, 263–276.

- Gardiner, S., and Rieckmann, M. Pedagogies of preparedness: Use of reflective journals in the operationalisation and development of anticipatory competence. Sustainability, 2015, 7, 10554–10575. [CrossRef]

- Giangrande, N., White, R. M., East, M., Jackson, R., Clarke, T., Saloff Coste, M., et al. A Competency Framework to Assess and Activate Education for Sustainable Development: Addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals. [CrossRef]

- 4.7 Challenge. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 2832.

- Glasser, H. Toward the Development of Robust Learning for Sustainability Core Competencies. Sustainability: J. Rec. 2016, 9, 121–134.

- Gómez-Olmedo, A. M., Valor, C., &, & Carrero, I. Mindfulness in education for sustainable development to nurture socioemotional competencies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Educ. Res., 2020, 26(11), 1527–1555.

- Gray, S. Measuring Systems Thinking. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 388–389.

- Griswold, W. “We can’t wait anymore:” Young professionals engaging in education for sustainability. Adult Educ. Q., 2022, 72(2), 197–215.

- Grosseck, G., Țîru, L. G., & Bran, R. A. Education for sustainable development: Evolution and perspectives: A bibliometric review of research, 1992–2018. Sustainability, 2019, 11(21), 6136.

- Hull, R. B., Kimmel, C., Robertson, D. P., and Mortimer, M. International Field Experiences Promote Professional Development for Sustainability Leaders. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2016, 17, 86–104. [CrossRef]

- Jegstad, K. M., and Sinnes, A. T. Chemistry Teaching for the Future: A Model for Secondary Chemistry Education for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sci. Edu. 2015, 37, 655–683. [CrossRef]

- Kassel, K., Rimanoczy, I., & Mitchell, S. The sustainable mindset: Connecting being, thinking, and doing in management education. Acad. Manag. Proc., 2016, 16659.

- Kestin, T. S., Lumbreras, J., & Cortés Puch, M. Mobilizing higher education action on the SDGs: insights from system change approaches. In Higher Education and SDG17: Partnerships for the Goals, 1st ed.; Cabrera, Á. & Cutright D. Eds. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 2023; pp. 27-49.

- Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Mcinerney, P., Soares, C., & Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldv. Evid. Based Nurs.. 2016, 13(2), 118-123.

- Killion, A. K., Ostrow Michel, J., & Hawes, J. K. Toward identifying sustainability leadership competencies: Insights from mapping a graduate sustainability education curriculum. Sustainability, 2022, 14 (10). 5811.

- Komasinkski, A., and Ishimura, G. Critical Thinking and Normative Competencies for Sustainability Science Education. J. High. Educ. Lifelong Learn. 2017, 24, 21–37.

- Levy, M. A., Lubell, M. N., and McRoberts, N. The Structure of Mental Models of Sustainable Agriculture. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R., Barreiro-Gen, M., Pietikäinen, J., Gago-Cortes, C., Favi, C., Jimenez Munguia, M. T., Monus, F., Simão, J., Benayas, J., Desha, C., Bostanci, S., Djekic, I., Moneva, J. M., Sáenz, O., Awuzie, B., & Gladysz, B. Adopting sustainability competence-based education in academic disciplines: Insights from 13 higher education institutions. Sustain. Dev., 2022, 30(4), 620–635.

- Mader, C., Scott, G. & Razak, D. Effective Change Management, Governance & Policy for Sustainability Transformation in Higher Education. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J., 2013, 4, 267-284.

- Mahaffy, P. G., Matlin, S. A., Holme, T. A., and MacKellar, J. Systems Thinking for Education about the Molecular Basis of Sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 362–370. [CrossRef]

- Marathe, G. M., Dutta, T., & Kundu, S. Is management education preparing future leaders for sustainable business?: Opening minds but not hearts. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2020, 21(2), 372–392.

- McCarthy, B., & Eagle, L. Are the sustainability-oriented skills and competencies of business graduates meeting or missing employers’ needs? Perspectives of regional employers. Aust. J. Environ. Educ., 2021, 37(3), 326–343.

- McDonald, D. The golden passport: Harvard Business School, the limits of capitalism, and the moral failure of the MBA elite. Harper Business, New York, US, 2017.

- Metcalf, L., & Benn, S. Leadership for sustainability: An evolution of leadership ability. J. Bus. Ethics., 2013, 112, 369–384. [CrossRef]

- Mihas, P. Qualitative research methods: approaches to qualitative data analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed., Elsevier; 2023. pp. 302–313.

- Miska, C., & Mendenhall, M. E. Responsible leadership: A mapping of extant research and future directions. J. Bus. Ethics., 2018, 148(1), 117–134.

- Mochizuki, Y. Educating for transforming our world: Revisiting international debates surrounding education for sustainable development. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ., 2016, 19(1), 109–125.

- Montiel, I., Gallo, P. J., & Antolin-Lopez, R. What on earth should managers learn about corporate sustainability? A threshold concept approach. J. Bus. Ethics., 2020, 162 (4), 857-880. [CrossRef]

- Muff, K., Liechti, A., & Dyllick, T. How to apply responsible leadership theory in practice: A competency tool to collaborate on the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., 2020, 27(5), 2254–2274. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol., 2018, 18(1). 1-7.

- OECD. Executive Summary: Definition and selection of competencies (DeSeCo). Available online: https://www.deseco.ch/bfs/deseco/en/index/02.html (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Ojala, M. Hope and Anticipation in Education for a Sustainable Future. Futures, 2017, 94, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Pacis, M., & VanWynsberghe, R. Key sustainability competencies for education for sustainability: Creating a living, learning and adaptive tool for widespread use. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2020, 21(3), 575–592.

- Perez Salgado, F., Abbott, D., and Wilson, G. Dimensions of Professional Competences for Interventions towards Sustainability. Sustain. Sci., 2018, 13, 163–177.

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Khalil, H., Mcinerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc., 2015, 13 (3).

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Baldini Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. Scoping reviews. In JBI Rev. Man., Aromataris, E. & Munn, Z. Eds. 2020.

- Redman, A., & Wiek, A. Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. In Front. Educ., 6, p. 785163). Frontiers Media S.A., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Redman, A., Wiek, A., & Barth, M. Current practice of assessing students’ sustainability competencies: A review of tools. Sustain. Sci., 2021, 16(1), 117–135.

- Remington-Doucette, S. M., Hiller Connell, K. Y., Armstrong, C. M., and Musgrove, S. L. Assessing Sustainability Education in a Transdisciplinary Undergraduate Course Focused on Real-world Problem Solving. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2013, 14 (4), 404–433.

- Rimanoczy, I., & Klingenberg, B. The sustainability mindset indicator: A personal development tool. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain., 2021, 9(1), 43–79.

- Risopoulos-Pichler, F., Daghofer, F., & Steiner, G. Competences for solving complex problems: A cross-sectional survey on higher education for sustainability learning and transdisciplinarity. Sustainability, 2020, 12(15), 6016. [CrossRef]

- Roller, R. H. Finance and business ethics in an era of stakeholder capitalism. J. Educ. Bus., 2022, 97(7), 490–496. [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D. S. Alignment with OECD Definition and Selection of Competencies: Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations (DeSeCo) Project. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/transformative-competencies/Thought_leader_written_statement_Rychen.pdf (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (Eds.). Definition and selection of competencies—Theoretical and conceptual foundations. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Switzerland, 2001.

- Sanchez-Carrillo, J. C., Cadarso, M. A., & Tobarra, M. A. Embracing higher education leadership in sustainability: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod., 2021, 298, 126675.

- Sandri, O. J. (2013). Threshold Concepts, Systems and Learning for Sustainability. Environ. Edu. Res., 2013, 19, 810–822.

- Sarpin, N., Kasim, N., Zainal, R., & Noh, H. M. A guideline for interpersonal capabilities enhancement to support sustainable facility management practice. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Langkawi, Malaysia, 3-5 December 2017. 2018, 40(1), 012116. IOP Publishing.

- Schank, C., and Rieckmann, M. Socio-economically Substantiated Education for Sustainable Development: Development of Competencies and Value Orientations between Individual Responsibility and Structural Transformation. J. Edu. Sust. Dev. 2019, 13 (1), 67–91.

- Schuler, S., Fanta, D., Rosenkraenzer, F., and Riess, W. Systems Thinking within the Scope of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)—a Heuristic Competence Model as a Basis for (Science) Teacher Education. J. Geogr. Higher Edu., 2018, 42(2), 192–204.

- Sekhar, C. (2020). The inclusion of sustainability in management education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2020, 21, 200-227.

- Singh, A. S., & Segatto, A. P. Challenges for education for sustainability in business courses. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2020, 21(2), 264–280. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. M. (2019). Innovative approaches to teaching sustainable development. In Encycl. Sustain. High. Educ. W. Leal Filho (Ed.), Springer International Publishing, Switzerland. 2019. pp. 954–964.

- Stough, T., Ceulemans, K., Lambrechts, W., & Cappuyns, V. Assessing sustainability in higher education curricula: A critical reflection on validity issues. J. Clean. Prod., 2018, 172, 4456–4466.

- Tavanti, M., Sfeir-Younis, A., & Wilp, E. A. Sustainability initiatives for management education: A roadmap for institutional integration. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain., 2022, 10(1), 87–118. [CrossRef]

- Times Higher Education (THE) Impact rankings. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/impactrankings (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Tricco, A.C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W. et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol., 2016, 16, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tufano, P. A Bolder Vision for Business Schools. Harvard Business Review. 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-bolder-vision-for-business-schools (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Ulrich, M. E. Learning Relational Ways of Being: What Globally Engaged Scholars Have Learned about Global Engagement and Sustainable Community Development. Doctoral dissertation, Montana State University, USA. 2016.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Learning for the future: Competences in education for sustainable development. Available online: http://www.unece.org/env/welcome.html (accessed 3.3.2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Education for sustainable development goals: learning objectives. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/education-sustainable-development-goals-learning-objectives (accessed 3.3.2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UNESCO competency framework. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/search/92be328d-7167-4312-8487-d9ee8530ffee (accessed 3.3.2025).

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda/ (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Velazquez, L., Munguia, N. and Sanchez, M. Deterring Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2005, 6, 383-391. [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, E. & Lambrechts, W. Fostering the incorporation of sustainable development in higher education. Lessons learned from a change management perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 106.

- Verma, P., Vaughan, K., Martin, K., Pulitano, E., Garrett, J., and Piirto, D. D. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science into Forestry, Natural Resources, and Environmental Programs. Journal of Forestry. 2016, 114 (6), 648–655.

- Wang, Y., Sommier, M., & Vasques, A. Sustainability education at higher education institutions: pedagogies and students’ competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2022, 23(8), 174–193. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. M., Lindenmeyer, C. P., Liò, P., & Lapkin, A. A. Teaching sustainability as complex systems approach: a sustainable development goals workshop. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ., 2021, 22(8), 25–41.

- Wesselink, R., Blok, V., van Leur, S., Lans, T., and Dentoni, D. Individual Competencies for Managers Engaged in Corporate Sustainable Management Practices. J. Clean. Prod., 2015, 106, 497–506.

- Weybrecht, G. From challenge to opportunity—Management education’s crucial role in sustainability and the sustainable development goals—An overview and framework. Int. J. Manag. Educ., 2017, 15(2, Part B), 84–92. [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A., Bernstein, M. J., Rider, W. F., Cohen, M., Forrest, N., Kuzdas, C., et al. “Operationalising Competencies in Higher Education for Sustainable Development.” In Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development, M. Barth, G. Michelsen, M. Rieckmann, and I. Thomas, (Eds.), Routledge, UK. 2016. Pp. 297–317.

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci., 2011, 6(2), 203–218.

- Withycombe, L. K. Anticipatory Competence as a Key Competence in Sustainability Education. Master Thesis, School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, USA. 2010.

- World Economic Forum. The global risks report 2022 (17 ed). Available online https://wef.ch/risks22 (accessed 3.3.2025).

- Žalėnienė, I., & Pereira, P. Higher education for sustainability: A global perspective. Geogr. Sustain., 2021, 2(2), 99–106.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).