Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relevance of Language Research

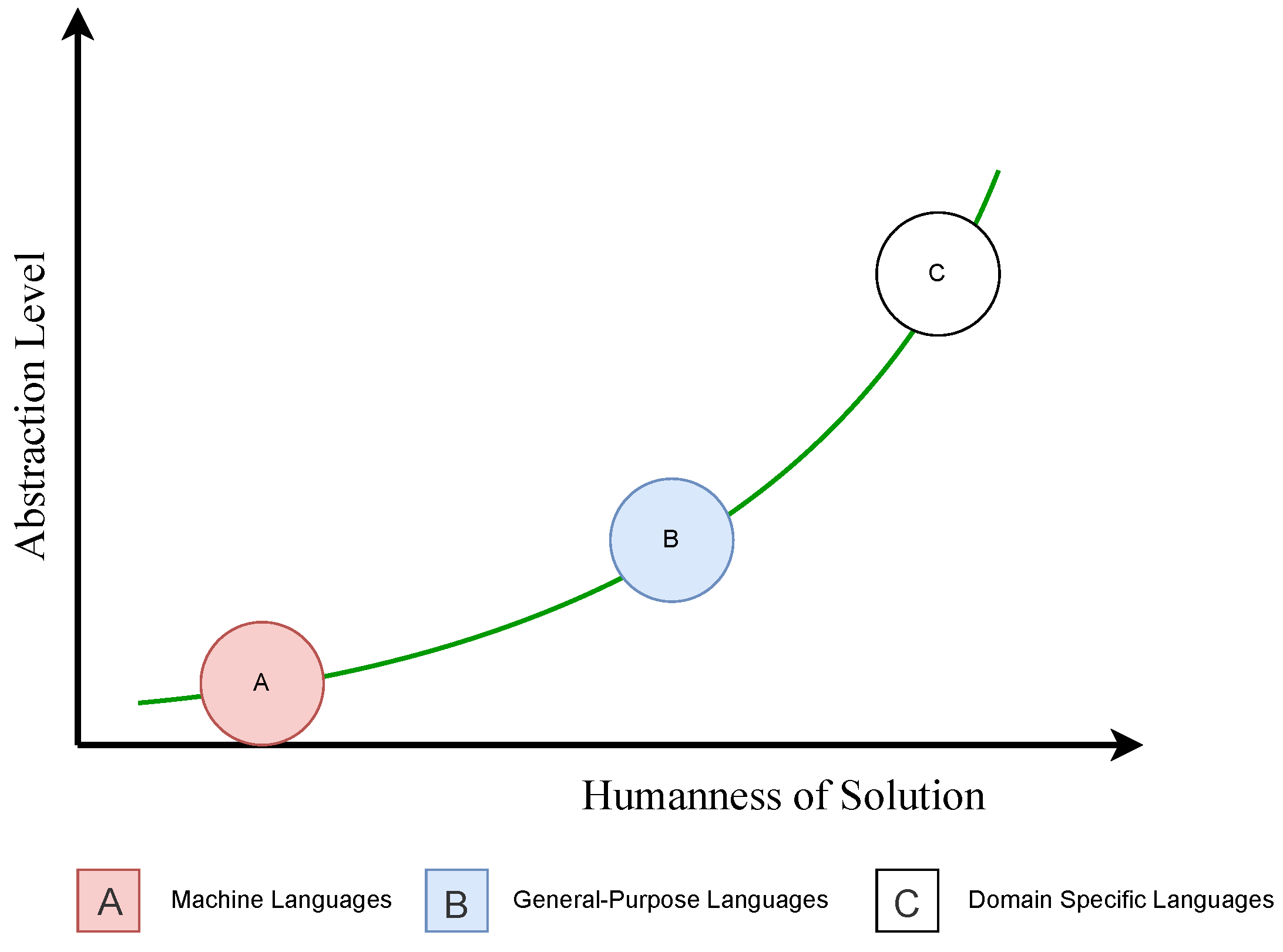

1.2. MLs vs GPLs vs DSLs

-

A: Machine Languages:

- -

- Operate at a very low abstraction level.

- -

- Express solutions in a style not meant for direct-human comprehension.

- -

- Typically are written in a numeric/binary or opcode/mnemonic or assembly-code syntax.

-

B: General-purpose [Programming] Languages:

- -

- Employ a sufficient amount of abstraction above the machine/processor.

- -

- Express solutions in a style meant for easier human comprehension and are great at expressing human logic.

- -

- Typically are written in a humane syntax close to mathematics.

-

C: Domain Specific [Programming] Languages:

- -

- Are typically very high in abstraction and very close to the problem domain in terms of their operation.

- -

- Express solutions in a style close to natural human language.

- -

- Their syntax is also very close to the problem domain.

1.3. Why TPLs?

All forms of text manipulation including word processing [19].

2. Concerning the Design of DSLs

2.1. A Preamble to All Language Design

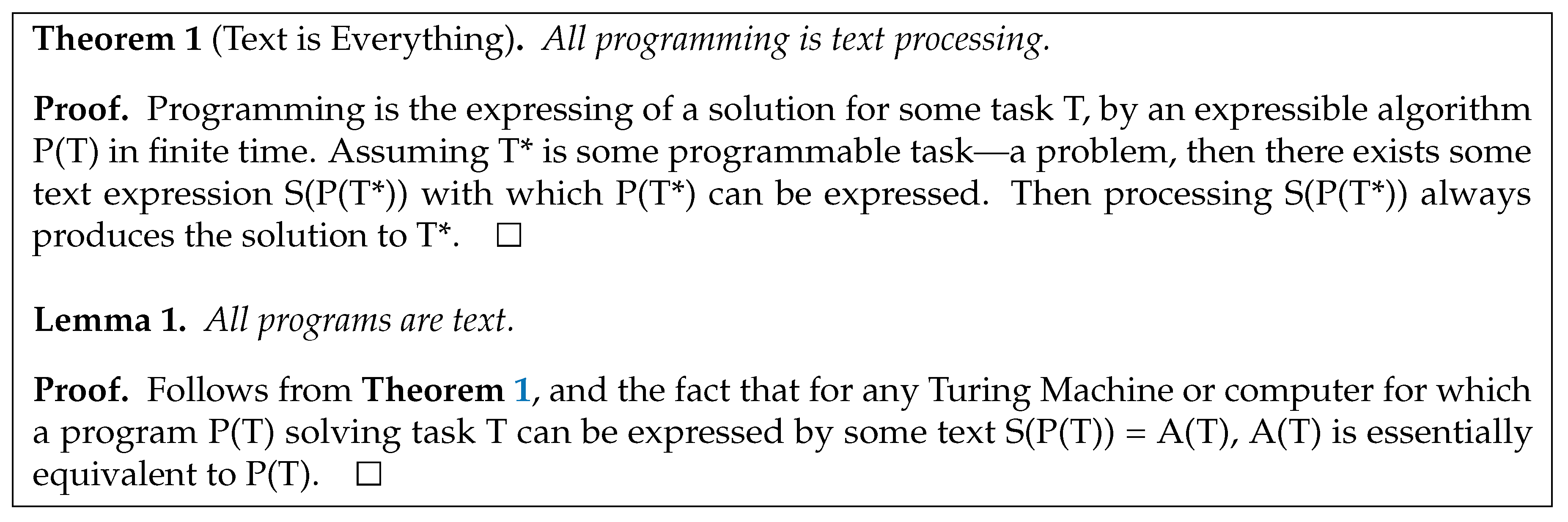

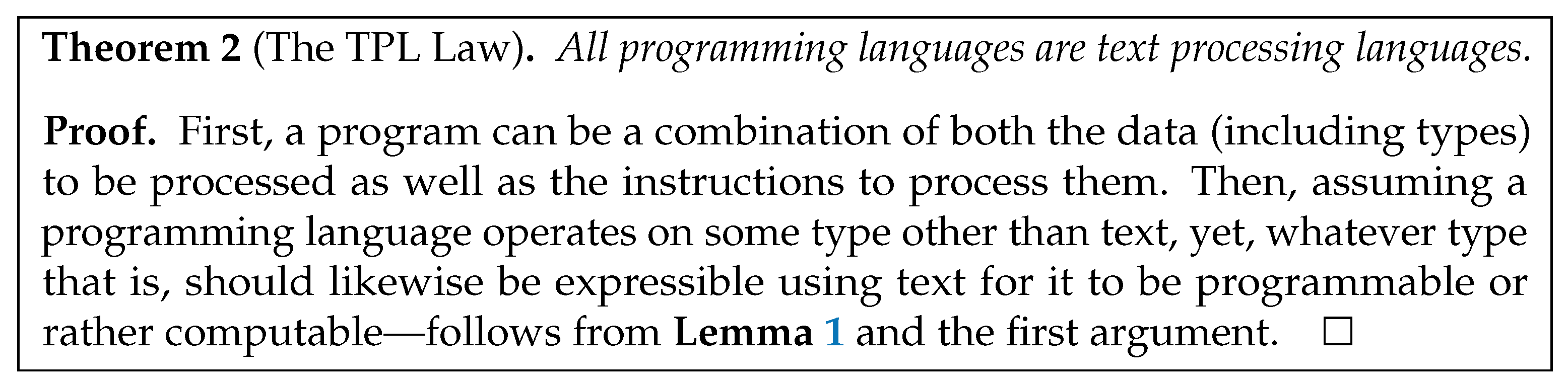

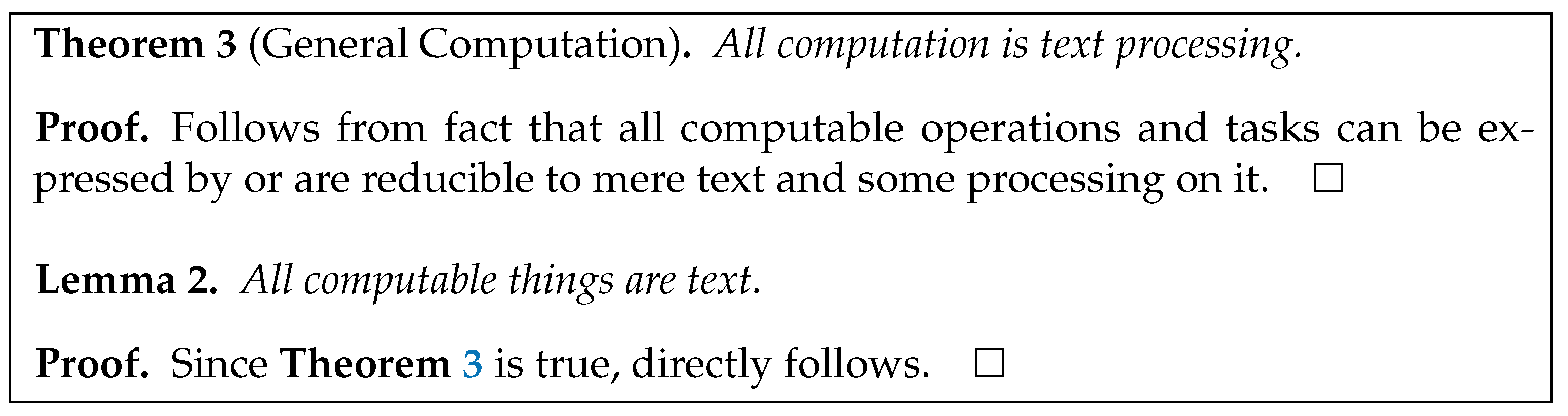

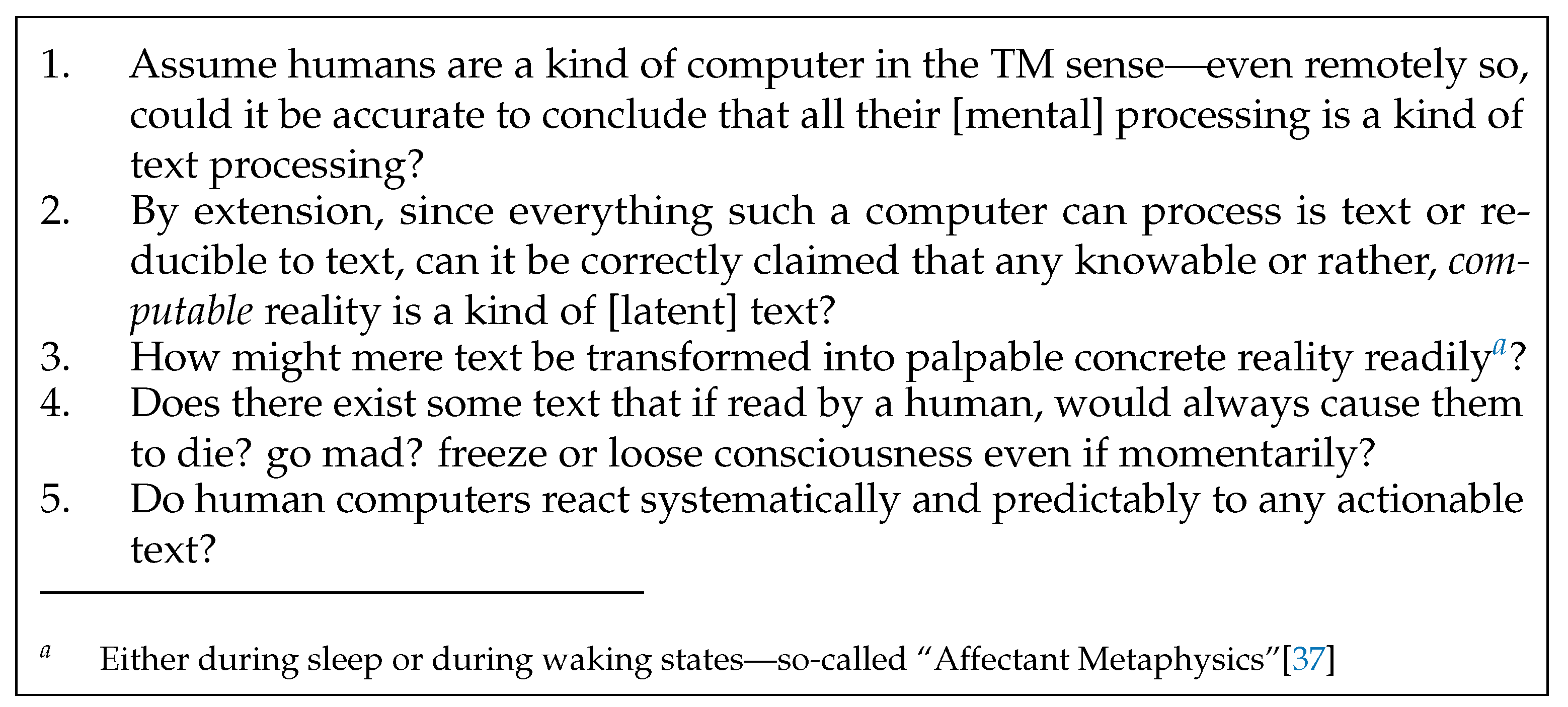

2.1.1. A Unifying Programming Language Theory

A machine with a separate program memory is often called a Harvard Machine, because the first computers built at Harvard in the 1940s used a separate paper tape for their programs; this tape was logically similar to a separate read-tape for their programs; this tape was logically similar to a separate read-only program memory. Machines that intermix programs and data in the same memory are called von Neumann Machines, or Princeton Machines, because the first machine built by von Neumman at Princeton placed the program and the data in the same memory unit. Sharing the same memory has an allocation advantage...

Sequence Analysis:

The application of sequence analysis determines those genes which encode regulatory sequences or peptides by using the information of sequencing. For sequence analysis, there are many powerful tools and computers which perform the duty of analyzing the genome of various organisms. These computers and tools also see the DNA mutations in an organism and also detect and identify those sequences which are related. Shotgun sequence techniques are also used for sequence analysis of numerous fragments of DNA. Special software is used to see the overlapping of fragments and their assembly.

Protein:

Protein database maintains the text record for individual protein sequences, derived from many different resources such as NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq) project, GenbBank, PDB and UniProtKB/SWISS-Prot. Protein records are present in different formats including FASTA and XML and are linked to other NCBI resources. Protein provides the relevant data to the users such as genes, DNA/RNA sequences, biological pathways, expression and variation data and literature. It also provides the pre-determined sets of similar and identical proteins for each sequence as computed by the BLAST. The Structure database of NCBI contains 3D coordinate sets for experimentally-determined structures in PDB that are imported by NCBI. The Conserved Domain database (CDD) of protein contains sequence profiles that characterize highly conserved domains within protein sequences. It also has records from external resources like SMART and Pfam. There is another database in protein known as Protein Clusters database which contains sets of proteins sequences that are clustered according to the maximum alignments between the individual sequences as calculated by BLAST.

2.2. Designing any DSL

Students work... create and implement a little language of their own design... student-created languages have covered diverse application domains including quantum computation, music synthesis, computer graphics, gaming, matrix operations and many other areas. Students use compiler-component generators such as ANTLR, Lex, and Yacc and the syntax directed translation techniques... to build their compilers.

- Defining the Domain.

- Designing a DSL that accurately captures the domain semantics.

- Building Software Tools or Software Components to support or realize the DSL.

- Developing applications (domain instances) using the newly developed DSL infrastructure so as to verify and evolve the DSL.

- Whether the language is to be used in a stand-alone context.

- Whether the language is to be embedable in other programs of other languages.

- Whether the language is meant to operate in user-space–such as for GUI systems, or is for low-level/system-level programming tasks—such as boot-loaders, system configuration or part of complex automation tasks such as are implemented with tools like Gradle[53] (which uses languages Groovy[54] or Kotlin[55]) or Ansible [56] (which uses YAML).

2.3. The Case of Designing TPLs

- A mechanism to read text into the program—if not during runtime, at least at program initiation or invocation.

- A mechanism to output or write text from the program—this could be merely writing to standard output (such as onto the screen, printer or over the network—e.g. to a networked projector), but also to more generic data-sinks such as files on the local or a remote/network file system.

- A mechanism to search for patterns in a text or generally, a string.

- A mechanism to replace or overwrite sections of or the entirety of a string.

- A mechanism to produce new text from other text—such as by the combination of multiple strings into one.

- A mechanism to fragment or split up strings—with or without explicit patterns.

- A mechanism to quantify strings—essentially, mapping a string to some numerical quantity, a number, such as by computing its length, or some other identifying metric such as a string’s unique hashcode.

- A mechanism to compare or contrast two or more strings—such as the ability to test strings for equivalence based on exact contents or by some regular pattern as is possible with regular expressions.

- A mechanism to reduce a large string to a smaller one—for example, by eliminating trailing white-space (typically known as stripping or trimming), eliminating certain sub-strings such as punctuation, redundancies, or perhaps automatically summarizing a long text etc.

- Performing some standard transform on a string, such as toggling an entire string to uppercase or title-case, etc.

3. Implementation of a DSL

3.1. Theory on DSL Implementation

3.1.1. It Is Generally Complex

3.1.2. The DSL Implementation Method

- Defining the domain

- Specifying the Requirements of the DSL

- Designing the DSL

- Constructing the DSL

- Supporting the DSL—basically, constructing tools to support the DSL

- Applying the DSL—which is about constructing applications or rather solutions in the domain, leveraging the DSL and the DSL’s support tools—the DSL infrastructure, platform or ecosystem—such as the so-called Software Operating Environment (SOE) for the language[65].

- Evaluating the DSL

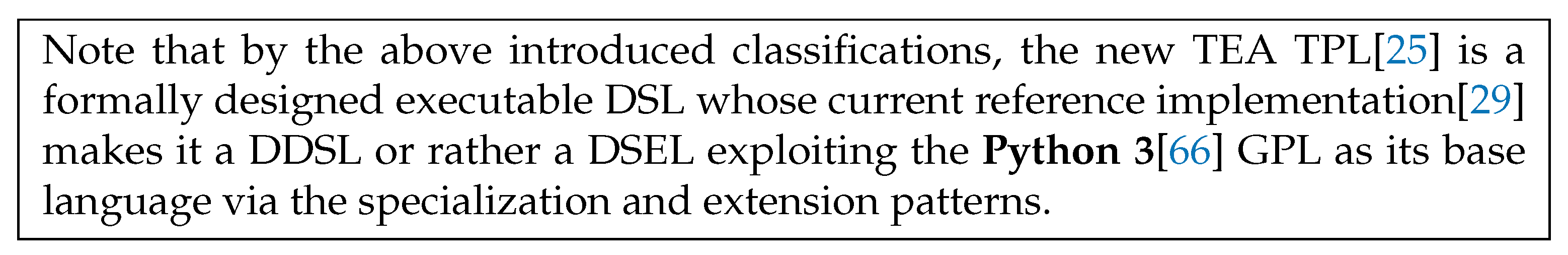

- Language Exploitation—in which the DSL is implemented (partially or wholly) using an existing GPL or another DSL. This pattern is further broken down into; Piggyback: in which an existing language is only partially used, Specialization: in which an existing language is merely restricted or constrained, and finally, Extension: in which an existing language is merely extended.

- Language Invention—this involves the design of the DSL entirely from scratch, with no commonality between the new DSL and any existing languages.

- Informal Design—which refers to cases where the DSL to be implemented is only described or specified informally, such as with natural languages or domain terms, but with no strict or formal/regular structures or properties being explicitly defined.

- Formal Design—in which case, the new DSL is explicitly, and wholly, rigorously specified, typically using an existing syntax and semantics definition method such as attribute grammars, re-write rules or an abstract state machine.

3.2. What to Consider When Implementing a TPL

- Spend more time working on, studying and understanding the TPL’s design and specification before actually implementing the TPL. Essentially, avoid directly jumping into the coding. Building extensive documentation about the specification and design of the language ahead of its implementation shall help streamline much of the actual implementation/coding phases to follow. Definitely, as with any software, it is wise to not fall into the trap of over-engineering, however, as language engineering isn’t just any kind of software engineering, clear, and careful attention to a Clean-Room Process shall greatly contribute to the robustness, correctness and efficiency of the language implementation.

- Ensure to give some considerable time to trying out the TPL conceptually—say, using pseudo-code or thought-experiments, before actually waiting to implement the language and then test or try it out. This, especially with some realistic problems in the domain the language is expected to solve, so as to identify and fix any conceptual, semantic or syntactic flaws with the planned language or its design before much effort is poured into its actual implementation. This phase can also readily help catch critical omissions in the language design, as well as eliminate unnecessary redundancies early-on. This then gives us a clean and robust language specification and design.

- Once the TPL is well designed—and this need not be done all at once or in one-sitting, then look around for any existing languages—especially those related to the planned language—by domain, grammar or syntax, and spend some time studying them or gleaning useful cues about how they were designed and implemented, and what makes them successful. Then adopt some of this knowledge for the implementation of your own TPL.

- Decide on whether the TPL is to be an interpreted or compiled language, as this will greatly determine how to proceed from its design to the implementation. Initial focus should be on realizing or manifesting a proof-of-concept, a prototype of the TPL and nothing more. For example, if the TPL is to be interpreted, then, merely deciding on which target environment, platform or operating system to build a proof-of-concept for, shall greatly narrow down much of the intimidating aspects of the language implementation—for example, it shall then be clear, what choice of technologies to leverage to implement the language, because, not every available language development tool might lend itself readily for any potential target operating environment.

- Start coding. Construct. Implement the damn language, and all the while, occasionally return to and consult the specification and design documents for the language, and if necessary, either evolve them or evolve the language implementation itself.

- Test! Don’t wait to fully implement the language before beginning to test it. Also, where the language development tools allow you to—important to consider this early on, ensure to have enough insights into what is actually going on inside your language’s run-time—the interpreter or compiler you are building should help with this, so that it is simple to catch implementation problems and tell where they originate from—let’s call it language-debugging—for example, a run-time test might fail, not because the language design or semantics are wrong, but because the implementation has a flaw. But also, it could be that the test itself is the problem and that time shouldn’t be wasted trying to fix the language implementation or design without knowing clearly, unambiguously, what each written test should produce as its result or output with or without the actual language implementation! So, do lots of things in the head! It also helps.

- Iterate!

3.3. Leveraging Design Research in Language Engineering

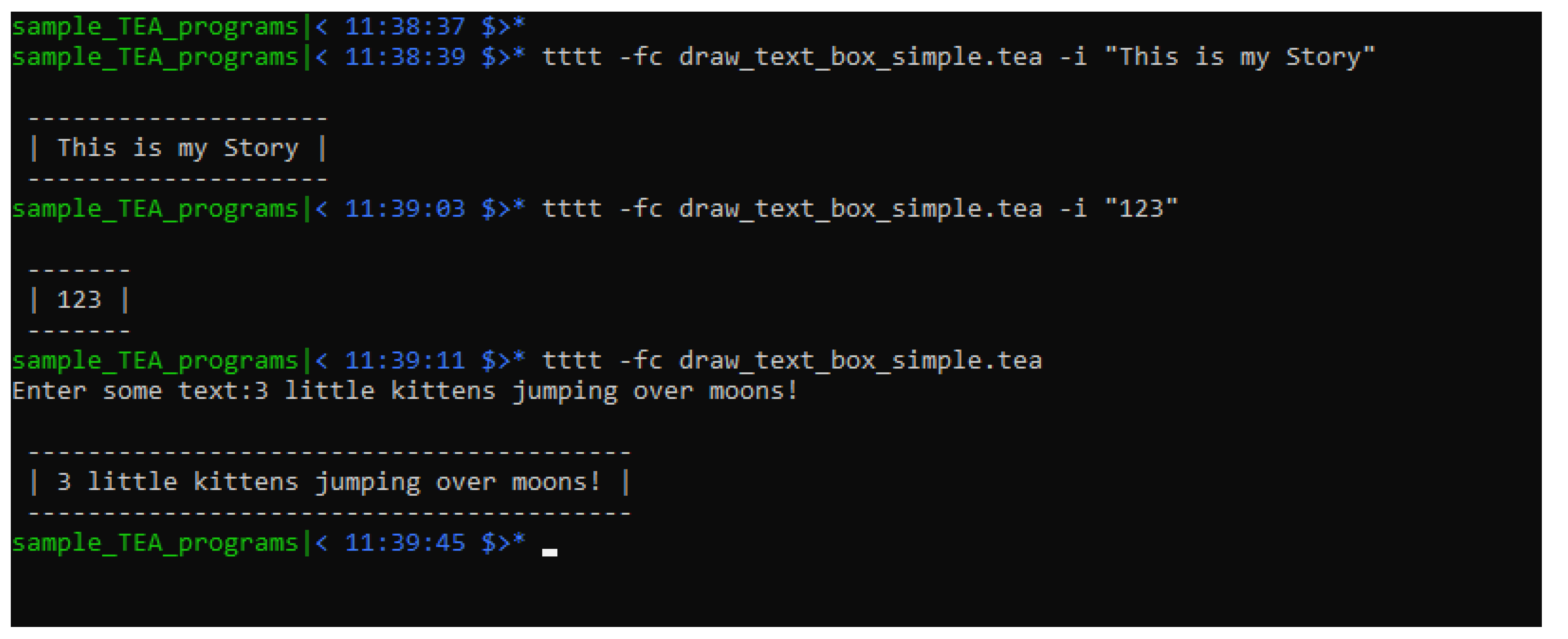

3.3.1. Example Results from TEA DSR Work

- A useful programming language specification and design example depicted in the TEA “TAZ” manuscript[25]

- Useful documentation concerning getting started with how to program in the TEA language—comes with the above mentioned tttt package, as well as more in the language’s official living manual[25]

- New knowledge and ideas such as we’ve come across in this very paper.

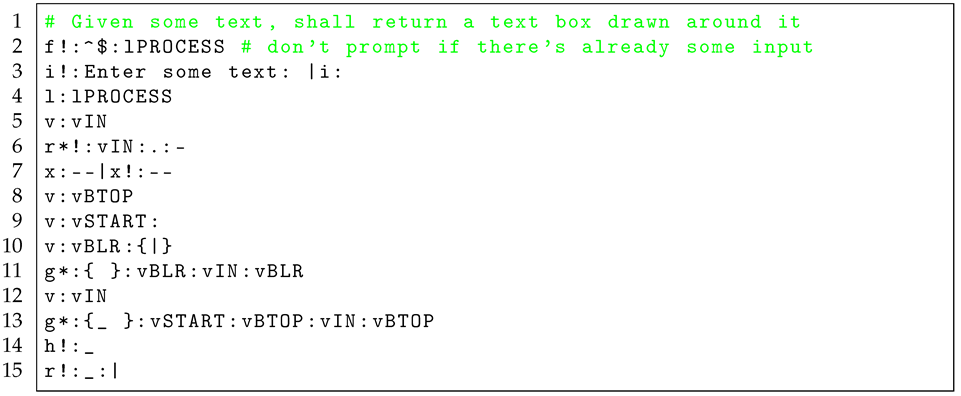

- A collection of example source-code and TEA programs included in the project’s official repository[29]

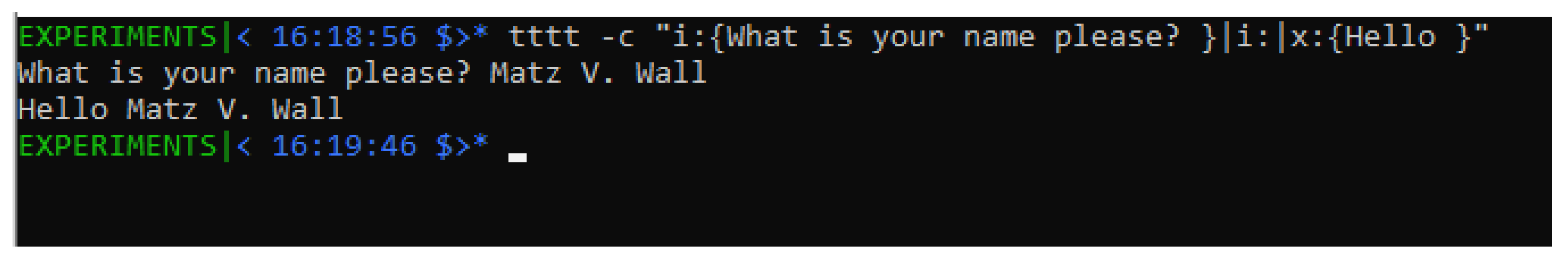

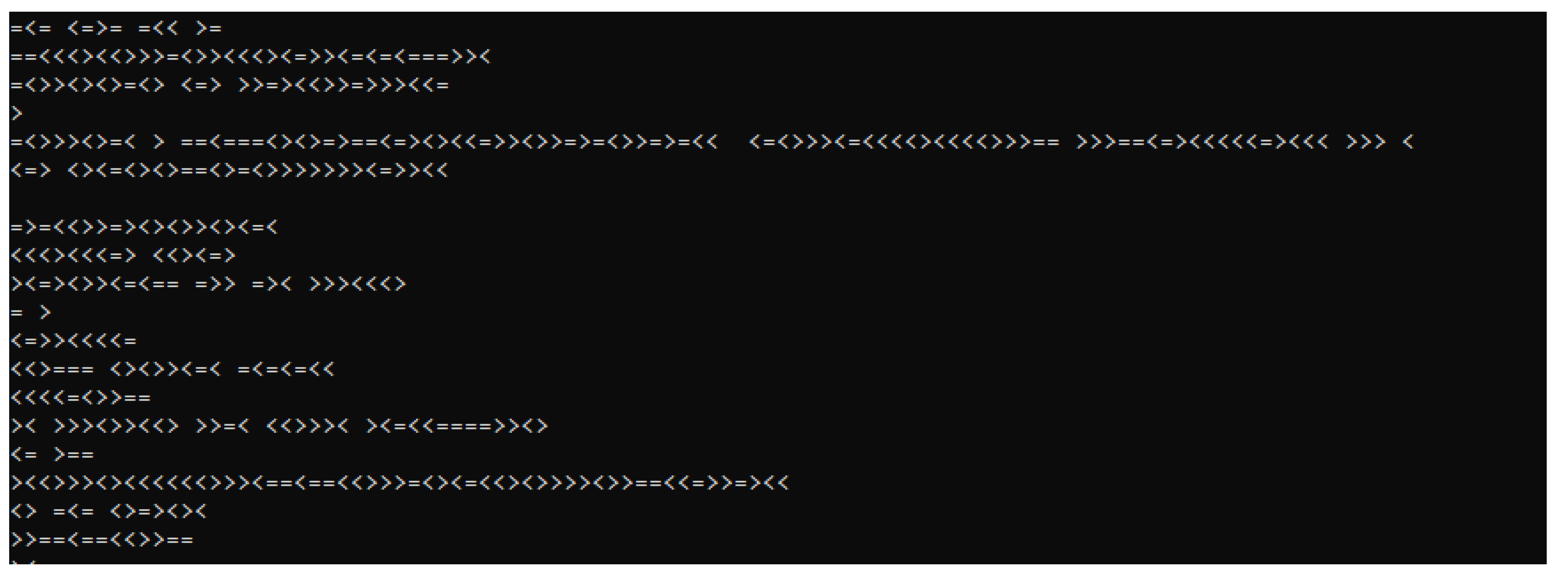

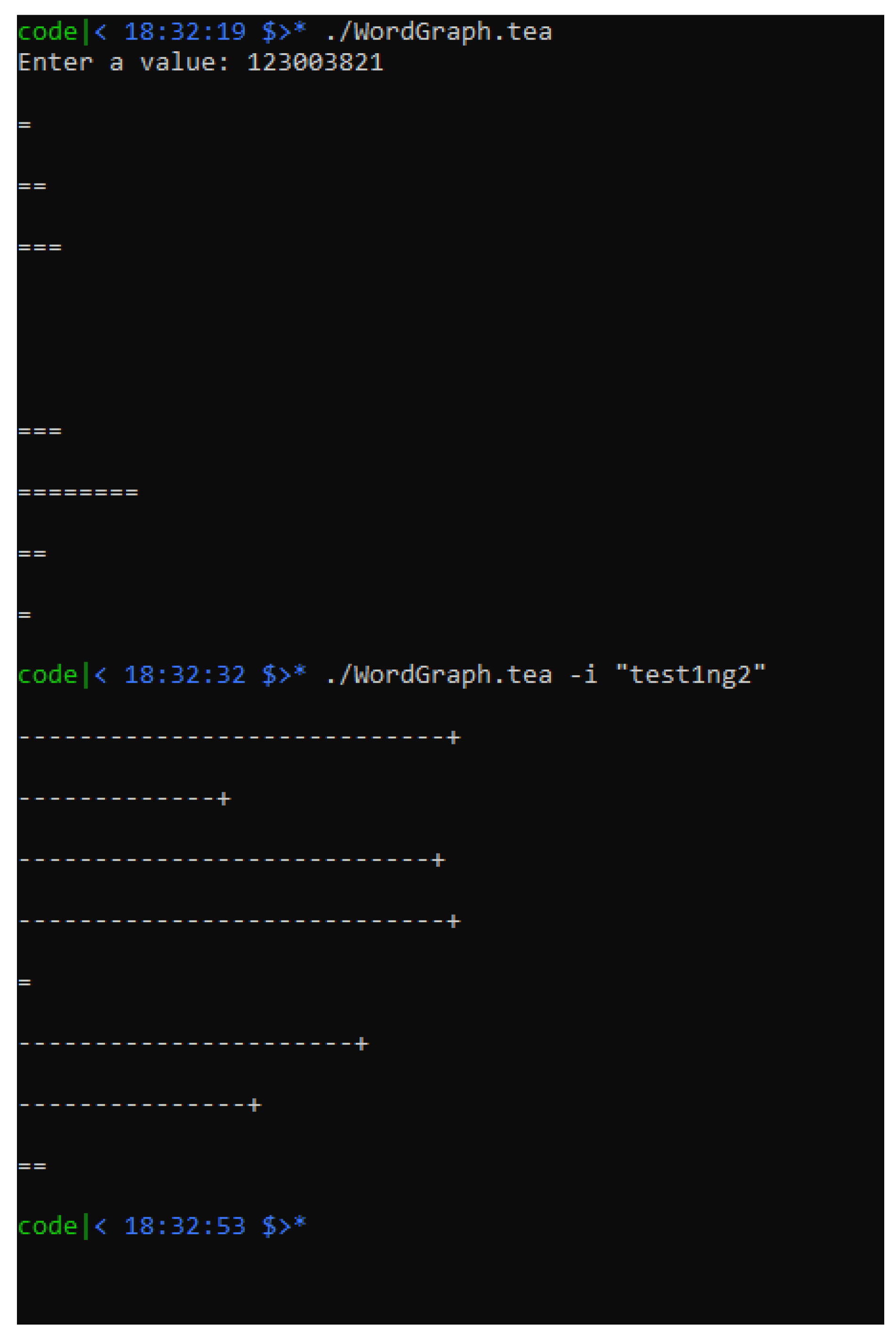

| Listing 1. Basic Text Processing with Graphics in TEA |

|

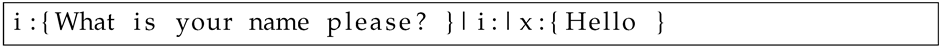

| Listing 2. An Interactive Hello World program in TEA |

|

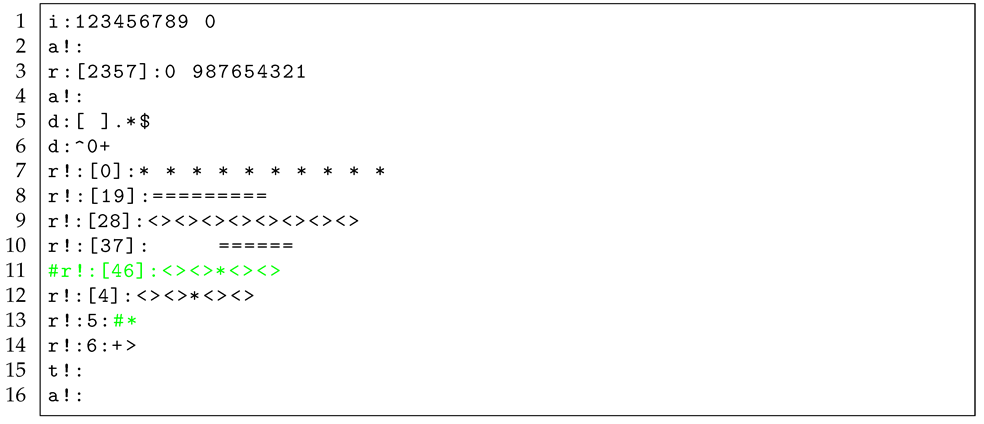

| Listing 3. TEA program Implementing an ART Generator. |

|

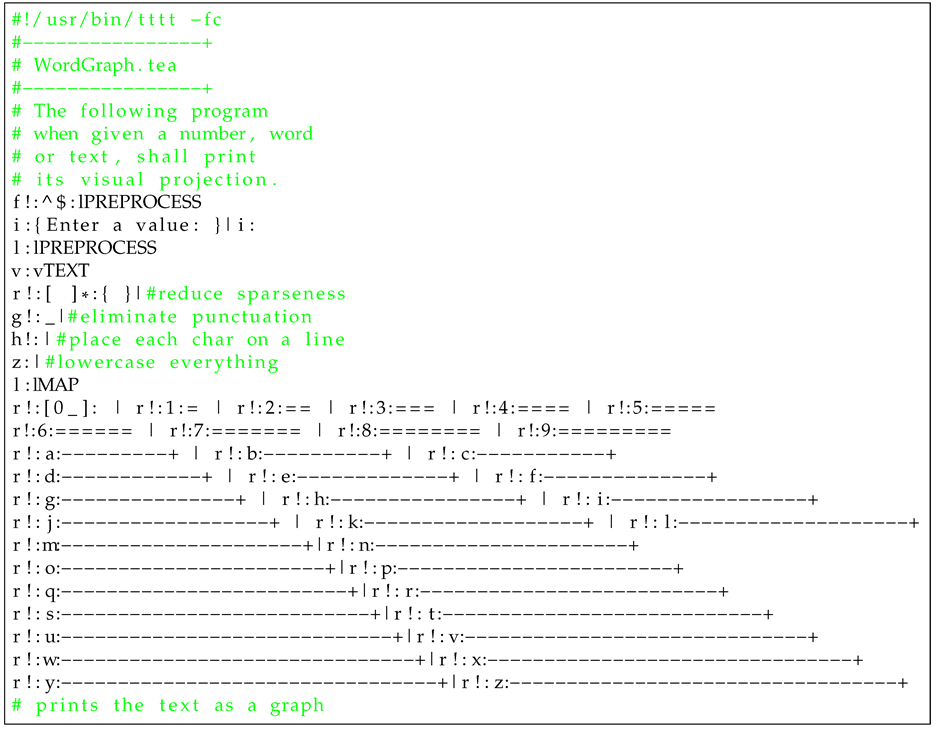

| Listing 4. Interactive Word-to-Graph TEA program |

|

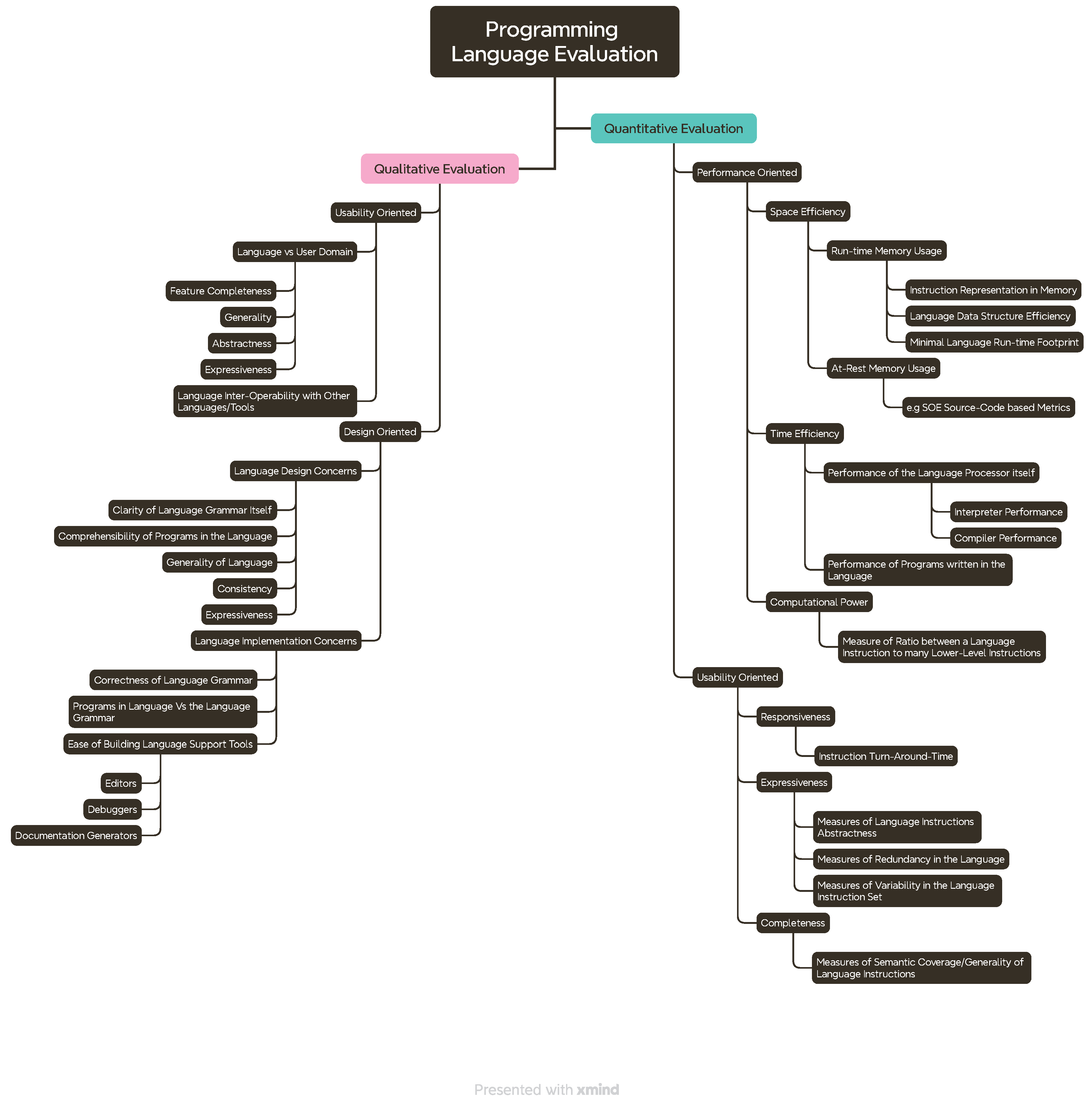

4. Systematic Evaluation of Programming Languages

4.1. DSLs vs GPLs, Humanness Vs Abstractness of Computer Languages

4.2. The SOE framework & Evaluating Any Set of Programming Languages by their Syntax Properties

4.3. The Case of Evaluating TPLs

- Most Basic String Concatenation Program (MBSCP)—a case in which, for example, two small strings such as “Hello” and “World” are combined into one larger string, to form “HelloWorld”.

- Most Basic String Filtering Program (MBSFP)—in which, for example, one string, such as “Hello World” has every instance of another string such as “o”—typically referred to as the search pattern, used to eliminate contents from the first string—producing “HellWrld” in this example.

- Most Basic String Quantification Program (MBSQP)—for example, given “Hello World”, to compute and return its length, 11.

5. Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Addendum

References

- Kain, R. Advanced computer architecture: a system design approach. In Proceedings of the 1996 workshop on Computer architecture education; 1996; pp. 12,116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Field, D. The world’s greatest architecture: Past and present; Chartwell, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nawangwe, B. The evolution of the Kibuga into Kampala’s city centre-analysis of the transformation of an African city. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer, R. Computation: A fundamental physical view. Physica Scripta 1987, 35, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwig, M.; Walkingshaw, E. Semantics first! Rethinking the language design process. In International Conference on Software Language Engineering; Springer, 2011; pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, N.; Pereira, M.J.; Henriques, P.R.; Cruz, D. Domain specific languages: A theoretical survey. INForum’09-Simpósio de Informática, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mernik, M. Domain-specific languages: A systematic mapping study. In International Conference on Current Trends in Theory and Practice of Informatics; Springer, 2017; pp. 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G.D. Github copilot: Copyright, fair use, creativity, transformativity, and algorithms. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J. An Introduction to Microsoft Copilot. In Copilot for Microsoft 365: Harness the Power of Generative AI in the Microsoft Apps You Use Every Day; Springer, 2024; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Idrisov, B.; Schlippe, T. Program Code Generation with Generative AIs. Algorithms 2024, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, I. 1.2 The software process; Addison-Wesley, 1995; pp. 7–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hudak, P. Domain-specific languages. In Handbook of programming languages; 1997; Volume 3, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum, G.; Warsaw, B.; Coghlan, N. PEP 8 – Style Guide for Python Code, 2001. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- (W3C), W.W.W.C. CSS: Cascading Style Sheets, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Team, G.D. DOT Language - Graphviz, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Urban, M. An introduction to LATEX; TEX users group, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lovrencic, A.; Konecki, M.; Orehovački, T. 1957-2007: 50 Years of Higher Order Programming Languages. Journal of Information and Organizational Sciences 2009, 33, 79–150. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, E. Transitions and animations in CSS: adding motion with CSS; “O’Reilly Media, Inc.”, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary of computing, 4 ed.; Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Wienold, G. Some basic aspects of text processing. Poetics Today 1981, 2, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, D. Text processing in Python; Addison-Wesley Professional, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J. Flex & Bison: Text Processing Tools; “O’Reilly Media, Inc.”, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, G.; Mariano, C. String Processing and Information Retrieval, 2005.

- Tucker, A. Text Processing: Algorithms, Languages, and Applications; Bristol-Myers Squibb Cancer Symposia; Academic Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lutalo, J.W. TEA TAZ -Transforming Executable Alphabet A: to Z: COMMAND SPACE SPECIFICATION. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siino, M.; Tinnirello, I.; La Cascia, M. Is text preprocessing still worth the time? A comparative survey on the influence of popular preprocessing methods on Transformers and traditional classifiers. Information Systems 2024, 121, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessenov, K.; Tulsiani, S.; Menon, A.; Miller, R.C.; Gulwani, S.; Lampson, B.; Kalai, A. A colorful approach to text processing by example. In Proceedings of the 26th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology; 2013; pp. 495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.C.; Myers, B.A.; others. Lightweight Structured Text Processing. USENIX Annual Technical Conference, General Track, 1999; 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- mcnemesis. cli_tttt: Command Line Interface for TTTT, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-21.

- TutorialsPoint. C Standard Library - , 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Foundation, P.S. Python Standard Library - string, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Zelle, J.M. Python Programming: An Introduction to Computer Science, 2nd ed.; Franklin, Beedle & Associates Inc., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Corporation, O. Java Platform SE 8 - String Class, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Baker, S. String::Util - String processing utility functions, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Lutalo, J.W. Numbers from Arbitrary Text: Mapping Human Readable Text to Numbers in Base-36. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, J. Kabbalah: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lutalo, J.W. Explorations in Probabilistic Metaphysics. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- contributors, W. Branches of Science, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- contributors, W. Computational Science, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- Tiwary, B.K. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology: A Primer for Biologists. SpringerLink, Accessed: 2024-09-25. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath, J.R.; Harvey, S.S.; Oldroyd, N.J. Automated fluorescent DNA sequencing on the ABI PRISM 377. In DNA sequencing protocols; 2001; pp. 119–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kugonza, D.R.; Kiwuwa, G.; Mpairwe, D.; Jianlin, H.; Nabasirye, M.; Okeyo, A.; Hanotte, O. Accuracy of pastoralists’ memory-based kinship assignment of Ankole cattle: a microsatellite DNA analysis. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 2012, 129, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- of Science, S.I.; Technology. Course Material: SBB1609, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- (OMG), O.M.G. Unified Modeling Language (UML) Specification Version 2.5.1, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Schmidt, E.; Lesk, M. Lex - A Lexical Analyzer Generator, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Johnson, S.C. Yacc - Yet Another Compiler Compiler, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Stallman, R.M.; McGrath, R.; Smith, P.D. GNU Make: A Program for Directing Recompilation, Accessed: 2024-09-25, 4.3 ed.; Free Software Foundation, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, J.; Naur, P.; others. Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 60; Introduced the BNF notation; Springer, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Aho, A.V.; Sethi, R.; Ullman, J.D. Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC. SQL: Structured Query Language, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Ben-Kiki, O.; Evans, C.; döt Net, I. YAML Ain’t Markup Language (YAML) Version 1.2, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Microsoft. F# Language Reference, 2024. Accessed: September 21, 2024.

- Muschko, B. Gradle in Action; Manning Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Champeau, C.; Koenig, D.; D’Arcy, H.; King, P.; Laforge, G.; Pragt, E.; Skeet, J. Groovy in Action; Manning Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akhin, M.; Belyaev, M.; others. Kotlin language specification: Kotlin/Core. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, P.; Pujar, S.; Nalawade, G.; Gebhardt, R.; Mandel, L.; Buratti, L. Ansible Lightspeed: A Code Generation Service for IT Automation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.17442. [Google Scholar]

- contributors, R. LearnPython: Discussion on Python Programming, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- Salton, G. Automatic text processing: The transformation, analysis, and retrieval of. Reading: Addison-Wesley 1989, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, S.; Narayanan, S. AN EMPIRICAL TEXT TRANFORMATION METHOD FOR SPONTANEOUS SPEECH SYNTHESIZERS.

- Kathuria, A.; Gupta, A.; Singla, R. A review of tools and techniques for preprocessing of textual data. In Computational Methods and Data Engineering: Proceedings of ICMDE 2020, Volume 1; 2021; pp. 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, A. Sed and awk Pocket Reference: Text Processing with Regular Expressions; “O’Reilly Media, Inc.”, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, T.; Wall, L.; Orwant, J.; others. Programming Perl: Unmatched power for text processing and scripting; “O’Reilly Media, Inc.”, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lutalo, J.W. Combined Latest Resume — JWL. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuchwezi. Nuchwezi: Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Society, 2024.

- Lutalo, J.W.; Eyobu, O.S.; Kanagwa, B. DNAP: Dynamic Nuchwezi Architecture Platform-A New Software Extension and Construction Technology. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Team, P.C. Python: A dynamic, open source programming language, Python version 3.x; Python Software Foundation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lutalo, J.W.; Oyana, T. VOSA: A Reusable and Reconfigurable Voice Operated Support Assistant Chatbot Platform. Available at SSRN 4810799 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson, P.; Perjons, E. An introduction to design science; Springer, 2014; Vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lutalo, J.W. VOSA: A Reusable and Reconfigurable Voice Operated Support Assistant Chatbot Platform, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Iivari, J. Twelve Theses on Design Science Research in Information Systems. In Design research in information systems: Theory and practice; 2010; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- HTML: HyperText Markup Language - The Official Standard, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

- Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) - The Official Standard, 2024. Accessed: 2024-09-25.

| 1 | The Reference Implementation & TEA documentation at https://github.com/mcnemesis/cli_tttt

|

| 2 | Defines a computer program! |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Concept of a “mini-language” might be likened to Mernik’s concept of little languages[7] which are essentially small DSLs that do not include many features found in GPLs |

| 5 | Not to be confused with the later, shorter and related VOSA paper[67], the VOSA technical report is accesisble via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25138541

|

| 6 | |

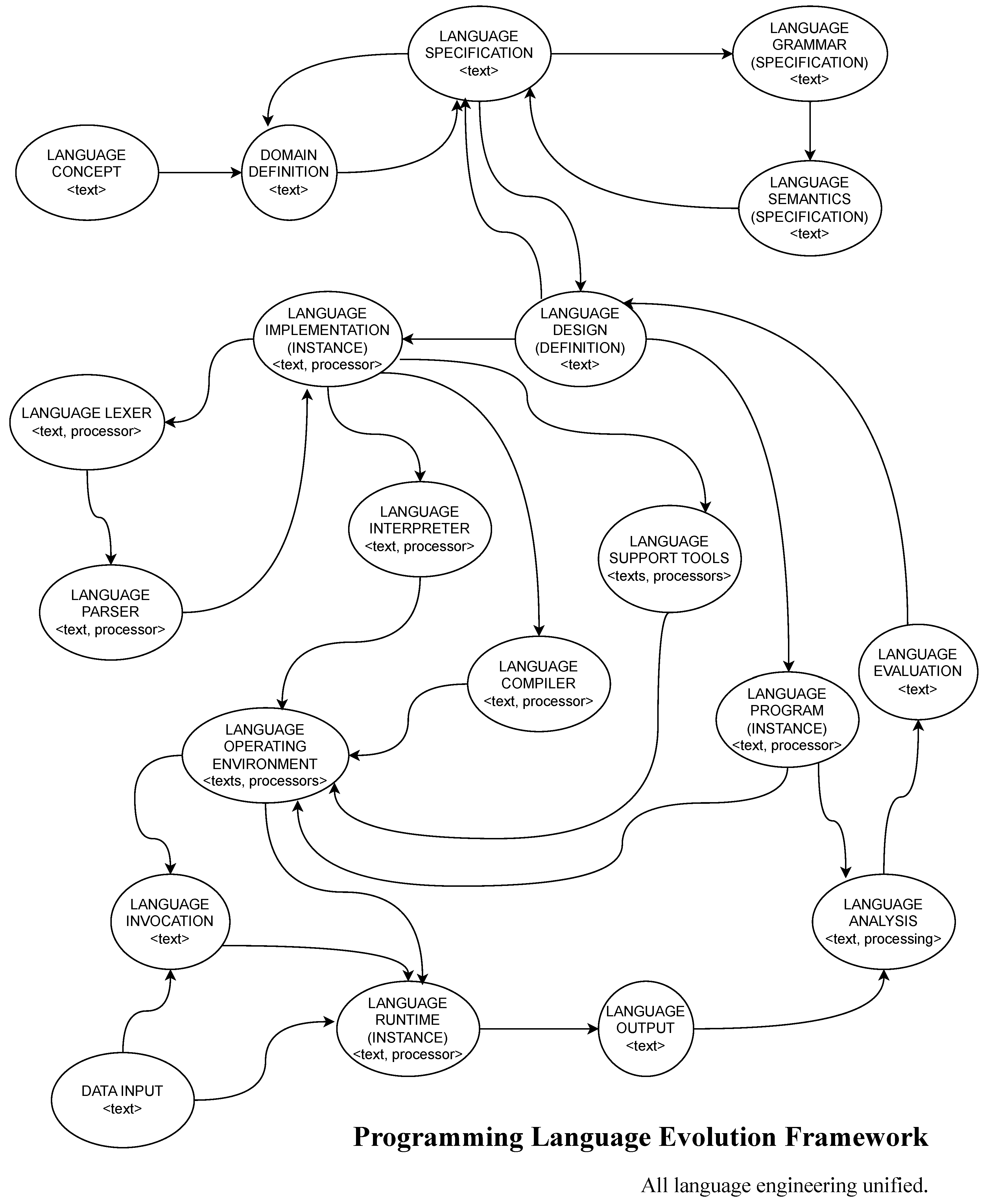

| 7 | The special acronym PLEf chosen so as to differentiate it from PLEF—the Programming Language Evolution Framework first defined in Figure 6

|

| 8 | Note that there might seem to be some circularity here... a kind of Chicken-Egg problem concerning whether a GPL or a DSL brings to life a TPL—which itself might in some contexts be considered a GPL! This confusion is the motivation for developing the UPLT in Section 2.1, and should motivate further research into this fundamental problem |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).