Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. A Review of Machine Learning Techniques for Business Failure Prediction

2.1. Logistic Regression

2.2. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

2.3. Decision Trees

2.4. Support Vector Machine (Linear Kernel)

2.5. Support Vector Machine (Non-Linear Kernel)

2.6. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

2.7 Random Forest

2.8. Gradient Boosting

2.9. XGBoost Classifier

2.10. AdaBoost Classifier

2.11. Catboost Classifier

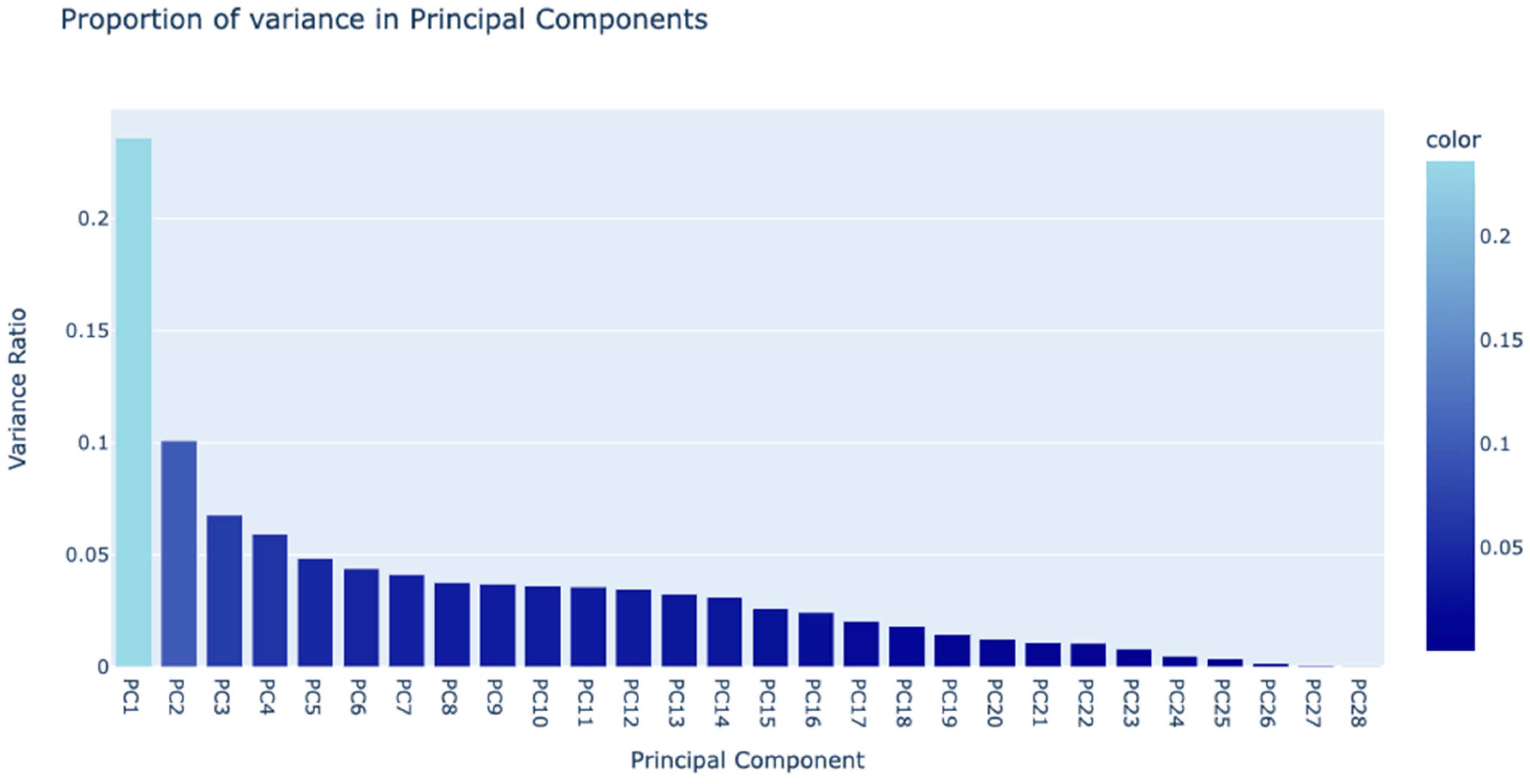

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

3.2. Data Screening Process

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

| Group | Failed Firm | Non-Failed Firm | ||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| ESG | 34.532 | 22.247 | 53.848 | 21.425 |

| P1 | -1692 | 11511 | -2.061 | 173 |

| P7 | -0.447 | 1.604 | 0.102 | 0.535 |

| P8 | -0.190 | 0.990 | 0.109 | 0.419 |

| L2 | -1.700 | 1.946 | -1.588 | 2.783 |

| L3 | 0.500 | 0.883 | 1.209 | 1.220 |

| AC1 | 41.16 | 124.37 | 88.83 | 1466.57 |

3.4. Pooled Within-Groups Correlation

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Application of Machine Learning Models for prediction Business Failure

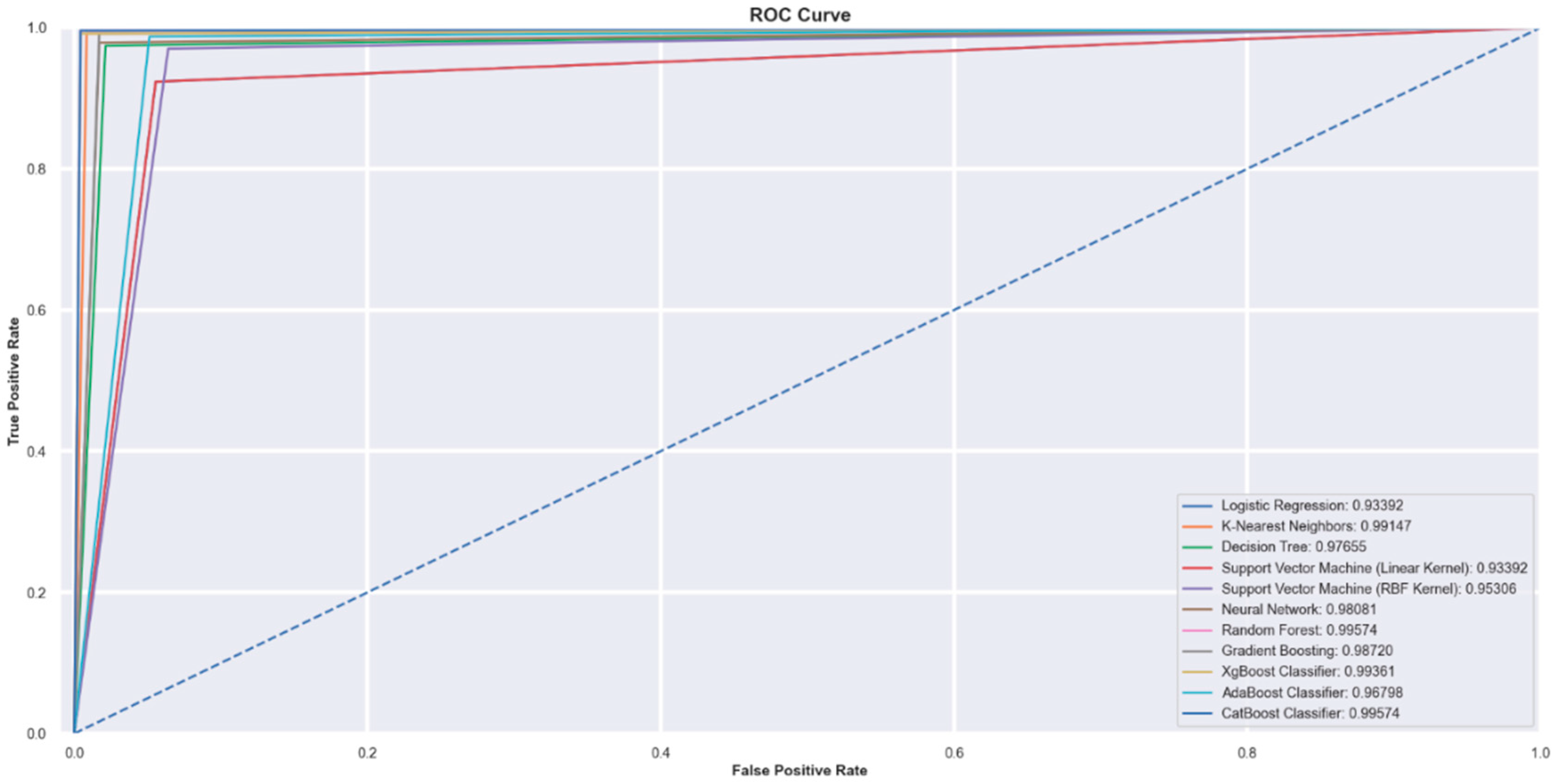

4.2. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves

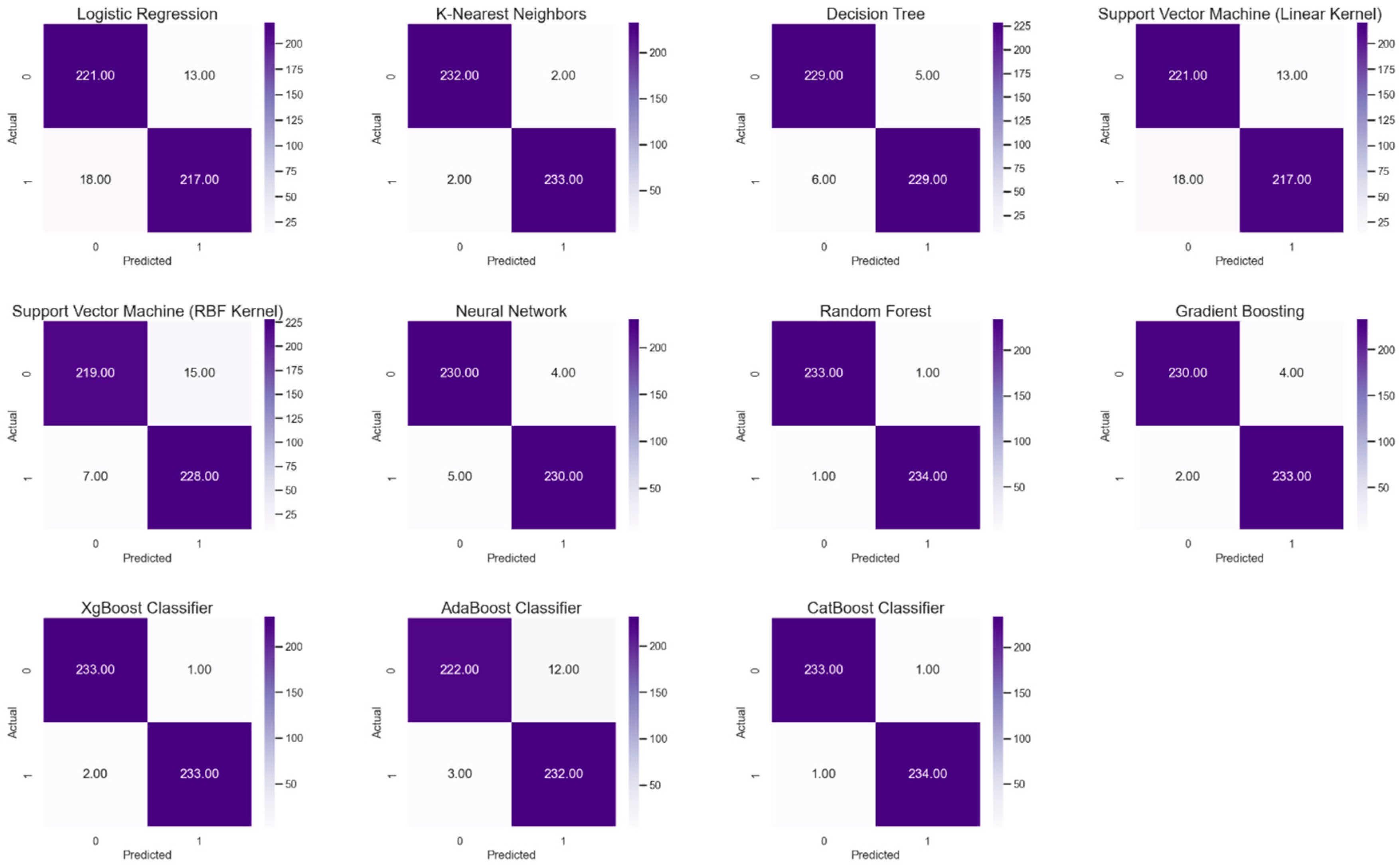

4.3. Confusion Matrices

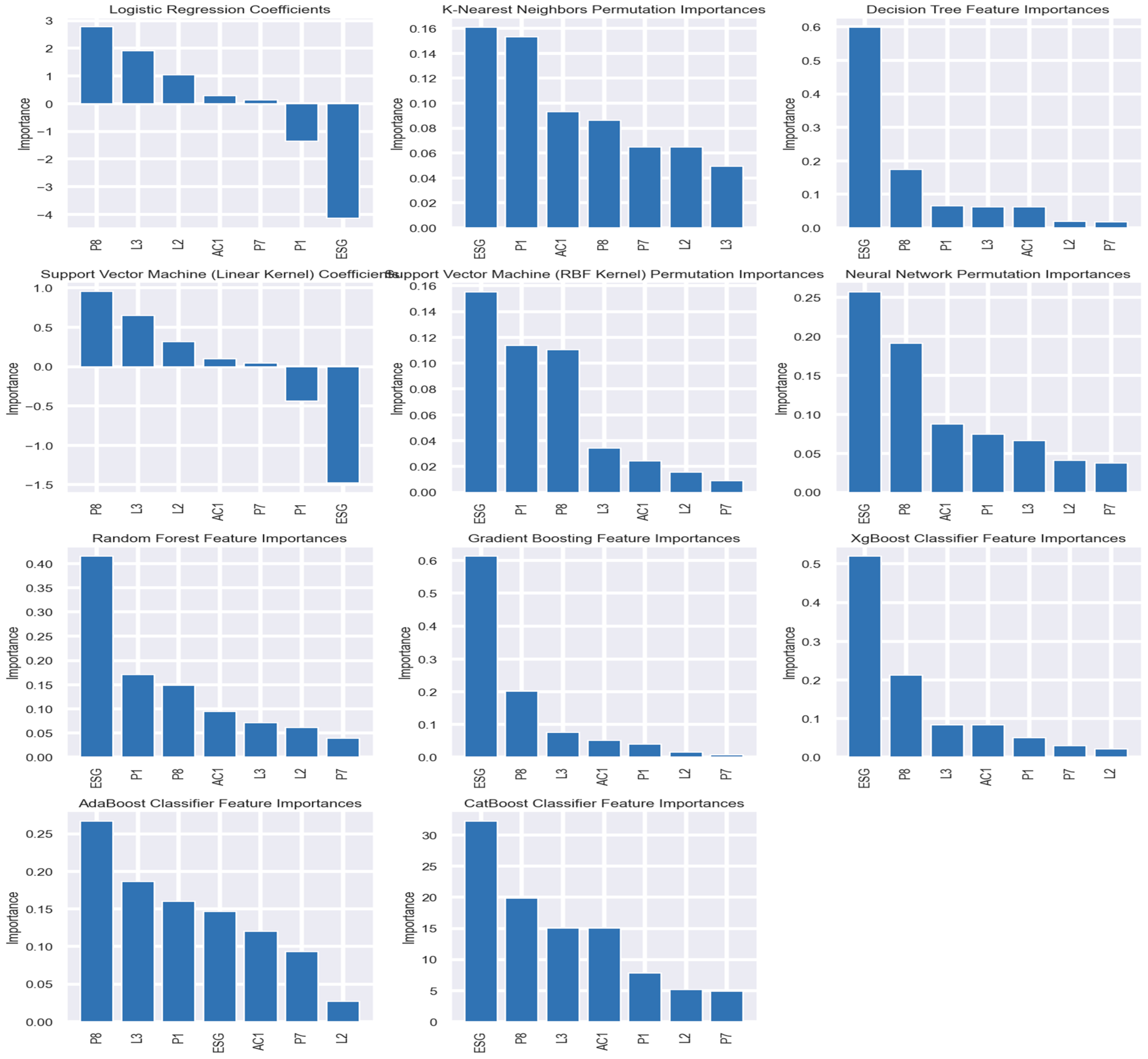

4.4. Feature Importance

Conclusion

References

- Abdi, A. M. (2020). Land cover and land use classification performance of machine learning algorithms in a boreal landscape using Sentinel-2 data. GIScience and Remote Sensing, 57(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Mobarek, A., & Roni, N. N. (2021). Revisiting the impact of ESG on financial performance of FTSE350 UK firms: Static and dynamic panel data analysis. Cogent Business and Management, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M., Anam, A. K., Julian, E., & Jaya, A. I. (2022). Interpretable Predictive Model of Network Intrusion Using Several Machine Learning Algorithms. BAREKENG: Jurnal Ilmu Matematika Dan Terapan, 16(1), 057–064. [CrossRef]

- Aljawazneh, huthaifa riyad. (2021). NEW APPROACHES TO IMPROVE THE PERFORMANCE OF MACHINE LEARNING AND DEEP LEARNING ALGOR I THMS IN SOLV ING REAL -WORLD PROBLEMS : COMPANIES FINANCIAL FAILURE FORECASTING.

- Alsayegh, M. F., Rahman, R. A., & Homayoun, S. (2020). Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(9). [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A., Ahmad, I. S., Bakar, A. A., & Yaakub, M. R. (2020). A hybrid metaheuristic method in training artificial neural network for bankruptcy prediction. IEEE Access, 8, 176640–176650. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F., Ribeiro, B., & Pereira, F. (2017). Probabilistic modeling and visualization for bankruptcy prediction. Applied Soft Computing Journal, 60, 831–843. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S., & Hosonuma, Y. (2004). Bankruptcy Prediction Using Decision Tree. The Application of Econophysics, 299–302. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R., Iqbal, S. M., & Omar, N. (2015). Prediction of business failure and fraudulent financial reporting: Evidence from Malaysia. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance, 8(1), 34–53. [CrossRef]

- Asselman, A., Khaldi, M., & Aammou, S. (2023). Enhancing the prediction of student performance based on the machine learning XGBoost algorithm. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(6), 3360–3379. [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M., Gülay, G., & Ergun, K. (2022). Impact of ESG performance on firm value and profitability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22, S119–S127. [CrossRef]

- Ayuni, N. W. D., Lasmini, N. N., & Putrawan, A. A. (2022). Support Vector Machine (SVM) as Financial Distress Model Prediction in Property and Real Estate Companies. Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Social Science 2022 (ICAST-SS 2022), 397–402. [CrossRef]

- Bapat, V., & Nagale, A. (2014). Comparison of Bankruptcy Prediction Models: Evidence from India. Accounting and Finance Research, 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, A., Faragó, C., Fekete, C., & Szeles, Z. (2018). The Bankruptcy Forecasting Model of Hungarian Enterprises. Advances in Economics and Business, 6(3), 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Barboza, F. L. D. M., Duarte, D. L., & Cunha, M. A. (2022). Anticipating corporate’s distresses. Exacta, 20(2), 470–496. [CrossRef]

- Bateni, L., & Asghari, F. (2016). Bankruptcy Prediction Using Logit and Genetic Algorithm Models: A Comparative Analysis. Computational Economics, 55(1), 335–348. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T., Ghosh, B., & Pakrashi, V. (2023). A Feature Extraction & Selection Benchmark for Structural Health Monitoring. Structural Health Monitoring, 22(3), 2082–2127. [CrossRef]

- Byvatov, E., Fechner, U., Sadowski, J., & Schneider, G. (2003). Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Artificial Neural Network Systems for Drug/Nondrug Classification. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences, 43(6), 1882–1889. [CrossRef]

- Capelli, P., Ielasi, F., & Russo, A. (2021). Forecasting volatility by integrating financial risk with environmental, social, and governance risk. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(5), 1483–1495. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A., & De, K. (2011). Fuzzy Support Vector Machine for bankruptcy prediction. Applied Soft Computing Journal, 11(2), 2472–2486. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 13-17-Augu, 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Sung, H., Cho, H., Lee, S., Son, H., & Kim, C. (2017). Comparison of single classifier models for predicting long-term business failure of construction companies using finance-based definition of the failure. ISARC 2017 - Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Isarc, 282–287. [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S., Rossi, M., Siggia, D., & Chouaibi, J. (2022). Exploring the moderating role of social and ethical practices in the relationship between environmental disclosure and financial performance: evidence from esg companies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Chui, K. T., & Lytras, M. D. (2019). A novel MOGA-SVM multinomial classification for organ inflammation detection. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 9(11). [CrossRef]

- Condon, M. (2022). Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Market Myopia ’ s Climate Bubble.

- Dellepiane, U., Di Marcantonio, M., Laghi, E., & Renzi, S. (2015). Bankruptcy Prediction Using Support Vector Machines and Feature Selection During the Recent Financial Crisis. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(8), 182–195. [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, G., & Mohri, M. (2016). Random composite forests. 30th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2016, 1540–1546. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Song, X., & Zen, Y. (2008). Forecasting financial condition of Chinese listed companies based on support vector machine. Expert Systems with Applications, 34(4), 3081–3089. [CrossRef]

- Elklawy, M. (2024). Is ESG a Determinant of Banks ’ resilience and Growth Everywhere ? A Response from an AI-Aided Approach Is ESG a determinant of banks ’ resilience and growth everywhere ? A response from an AI-aided approach.

- Faris, H., Abukhurma, R., Almanaseer, W., Saadeh, M., Mora, A. M., Castillo, P. A., & Aljarah, I. (2020). Improving financial bankruptcy prediction in a highly imbalanced class distribution using oversampling and ensemble learning: a case from the Spanish market. Progress in Artificial Intelligence, 9(1), 31–53. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Xu, Y.-X., Jiang, Y., & Zhou, Z.-H. (2020). Soft Gradient Boosting Machine. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. J., & Figueiredo, A. T. (2012). Ensemble Machine Learning. In Ensemble Machine Learning. [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [CrossRef]

- Furman, J., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1998). Economic crises: Evidence and insights from East Asia. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1998(2), 1–135. [CrossRef]

- Gaber, T., Tharwat, A., Hassanien, A. E., & Snasel, V. (2016). Biometric cattle identification approach based on Weber’s Local Descriptor and AdaBoost classifier. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 122, 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Ganatra, A. P., & Kosta, Y. P. (2010). Comprehensive Evolution and Evaluation of Boosting. International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering, January 2010, 931–936. [CrossRef]

- Gaytan, J. C. T., Ateeq, K., Rafiuddin, A., Alzoubi, H. M., Ghazal, T. M., Ahanger, T. A., Chaudhary, S., & Viju, G. K. (2022). AI-Based Prediction of Capital Structure: Performance Comparison of ANN SVM and LR Models. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Georganos, S., Grippa, T., Vanhuysse, S., Lennert, M., Shimoni, M., & Wolff, E. (2018). Very High Resolution Object-Based Land Use-Land Cover Urban Classification Using Extreme Gradient Boosting. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 15(4), 607–611. [CrossRef]

- Habib, A. M. (2023). Do business strategies and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance mitigate the likelihood of financial distress? A multiple mediation model. Heliyon, 9(7), e17847. [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, D. A., Kalambe, A. A., Goklas, L. S., & Alkhayyat, N. G. (2021). 613-Article Text-3028-1-10-20210930.

- He, S., & Li, F. (2021). Artificial Neural Network Model in Spatial Analysis of Geographic Information System. Mobile Information Systems, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hegde, G., Hulipalled, V. R., & Simha, J. B. (2023). Data driven algorithm selection to predict agriculture commodities price. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 13(4), 4671–4682. [CrossRef]

- Helminen, N. (2023). ESG MOMENTUM AND STOCK PERFORMANCE IN U.S. DURING 2018-2023 Does market reward companies for improving ESG scores? 6, 142–151.

- Hjaltason, G. R., & Samet, H. (1999). Distance browsing in spatial databases. ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 24(2), 265–318. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Jr, M. (2024). Benchmarking alternative interpretable machine learning models for corporate probability of default. In Data Science in Finance and Economics (Vol. 4, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S., He, H., & Jenkins, K. (2018). Information gain directed genetic algorithm wrapper feature selection for credit rating. Applied Soft Computing Journal, 69, 541–553. [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, H., Eric Gill, F. M. M. M., & Homayouni, S. (2021). Bagging and Boosting Ensemble Classifiers for Classification of Comparative Evaluation. Remote Sensing, MDPI.

- Kadkhodaei, H. R., Moghadam, A. M. E., & Dehghan, M. (2020). HBoost: A heterogeneous ensemble classifier based on the Boosting method and entropy measurement. Expert Systems with Applications, 157, 113482. [CrossRef]

- Kalaiarasi, G., & Maheswari, S. (2021). Deep proximal support vector machine classifiers for hyperspectral images classification. Neural Computing and Applications, 33(20), 13391–13415. [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, B., Pradhan, B., Amir Naghibi, S., Motevalli, A., & Mansor, S. (2018). Assessment of the effects of training data selection on the landslide susceptibility mapping: a comparison between support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression (LR) and artificial neural networks (ANN). Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 9(1), 49–69. [CrossRef]

- Karatzoglou, A., Smola, A., Hornik, K., & Zeileis, A. (2004). A survey on patents of typical robust image watermarking. Advanced Materials Research, 271–273(9), 389–393. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Li, Z. (2021). Understanding the impact of esg practices in corporate finance. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(7), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Klutse, S. K. (2022). PhD DISSERTATION Senanu Kwasi Klutse Szeged, 2022.

- Kovacova, M., & Kliestikova, J. (2017). Modelling bankruptcy prediction models in Slovak companies. SHS Web of Conferences, 39, 01013. [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, F. T., Isynuwardhana, D., & Rahayu, S. (2019). Market concentration, diversification, and financial distress in the Indonesian banking system. Jurnal Keuangan Dan Perbankan, 23(4), 514–524. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L., Yan, H., Zhu, Y., Tu, S., & Fan, X. (2019). Predicting duration of traffic accidents based on cost-sensitive Bayesian network and weighted K-nearest neighbor. Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems: Technology, Planning, and Operations, 23(2), 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., Bajaj, K., Sharma, B., & Narang, S. (2021). A Comparative Performance Assessment of Optimized Multilevel Ensemble Learning Model with Existing Classifier Models. Big Data, 10(5), 371–387. [CrossRef]

- Le, T., Vo, M. T., Vo, B., Lee, M. Y., & Baik, S. W. (2019). A Hybrid Approach Using Oversampling Technique and Cost-Sensitive Learning for Bankruptcy Prediction. Complexity, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. H., & Nam, K. (2006). Artificial Neural Network Modeling in Forecasting a Successful Implementation of ERP Systems. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Research, 2(1), 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Lim, T. (2024). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and artificial intelligence in finance: State-of-the-art and research takeaways. Artificial Intelligence Review, 57(4), 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W., Lu, Y., & Tsai, C. (2018). Feature selection in single and ensemble learning - based bankruptcy prediction models. July, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Lin, M. (2022). Research on The Influence of ESG Information Disclosure on Enterprise Financial Risk. Frontiers in Business, Economics and Management, 5(3), 264–271. [CrossRef]

- Marom, S., & Lussier, R. N. (2014). A Business Success Versus Failure Prediction Model for Small Businesses in Israel. Business and Economic Research, 4(2), 63. [CrossRef]

- Masanobu, M., SHOICHI, K., Hideki, K., & Takaaki, K. (2019). Bankruptcy prediction for Japanese corporations using support vector machine, artificial neural network, and multivariate discriminant analysis. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 01(01), 78–96. [CrossRef]

- Michalkova, L., Valaskova, K., Michalikova, K. F., & Constantin, A. D. (2018). The Holistic View of the Symptoms of Financial Health of Businesses. 56(Febm), 90–94. [CrossRef]

- Michela, P. (2023). The relationship between ESG Performance and Financial Stability : are sustainable companies less likely to fail ?

- Min, J. H., & Lee, Y. C. (2005). Bankruptcy prediction using support vector machine with optimal choice of kernel function parameters. Expert Systems with Applications, 28(4), 603–614. [CrossRef]

- Mishina, Y., Murata, R., Yamauchi, Y., Yamashita, T., & Fujiyoshi, H. (2015). Boosted random forest. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, E98D(9), 1630–1636. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S. R., Silva, R. G., Ribeiro, M. H. dal M., Fraccanabbia, N., Mariani, V. C., & Coelho, L. dos S. (2020). Very Short-term Wind Energy Forecasting Based on Stacking Ensemble. November, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Mukarramah, R., Atmajaya, D., & Ilmawan, L. B. (2021). Performance comparison of support vector machine (SVM) with linear kernel and polynomial kernel for multiclass sentiment analysis on twitter. ILKOM Jurnal Ilmiah, 13(2), 168–174. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Izquierdo, N., Camacho-Miñano, M. D. M., Segovia-Vargas, M. J., & Pascual-Ezama, D. (2019). Is the external audit report useful for bankruptcy prediction? Evidence using artificial intelligence. International Journal of Financial Studies, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, P. A., & Perri, F. (2005). Business cycles in emerging economies: The role of interest rates. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(2), 345–380. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. T. (2021). Application Machine Learning in Construction Management. TEM Journal, 10(3), 1385–1389. [CrossRef]

- Ogachi, D., Ndege, R., Gaturu, P., & Zoltan, Z. (2020). Corporate Bankruptcy Prediction Model , a Special Focus on Listed Companies in Kenya.

- Olatunji Akinrinola, Wilhelmina Afua Addy, Adeola Olusola Ajayi-Nifise, Olubusola Odeyemi, & Titilola Falaiye. (2024). Application of machine learning in tax prediction: A review with practical approaches. Global Journal of Engineering and Technology Advances, 18(2), 102–117. [CrossRef]

- ÖZPARLAK, G., & ÖZDEMİR DİLİDÜZGÜN, M. (2022). Corporate Bankruptcy Prediction Using Machine Learning Methods: the Case of the Usa. International Journal of Management Economics and Business, 18(4), 1007–1031. [CrossRef]

- Paramita, A. S., Maryati, I., & Tjahjono, L. M. (2022). Implementation of the K-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm for the Classification of Student Thesis Subjects. Journal of Applied Data Sciences, 3(3), 128–136. [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V., & Gulin, A. (2018). Catboost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018-Decem(Section 4), 6638–6648.

- Prusak, B. (2018). Review of Research into Enterprise Bankruptcy Prediction in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(3), 60. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, A. T., Lin, D. B., Adiprabowo, T., & Hendria, W. F. (2021). Non-contact monitoring and classification of breathing pattern for the supervision of people infected by covid-19. Sensors, 21(9), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Rainarli, E. (2019). The Comparison of Machine Learning Model to Predict Bankruptcy: Indonesian Stock Exchange Data. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 662(5), 0–6. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, F., & Furqon, M. T. (2022). The simplicity of XGBoost algorithm versus the complexity of Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Networks algorithms in urban forest classification. F1000Research, 11, 1069. [CrossRef]

- Rokach, L. (2016). Decision forest: Twenty years of research. Information Fusion, 27, 111–125. [CrossRef]

- Saadaari, F. S., Mireku-Gyimah, D. ., & Olaleye, B. M. (2020). Development of a Stope Stability Prediction Model Using Ensemble Learning Techniques - A Case Study. Ghana Mining Journal, 20(2), 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J., Tornell, A., & Velasco, A. (1996). Financial crises in emerging markets in 1995.pdf (p. 16).

- Sahin, E. K. (2020). Assessing the predictive capability of ensemble tree methods for landslide susceptibility mapping using XGBoost, gradient boosting machine, and random forest. SN Applied Sciences, 2(7). [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I. H., Faruque, F., Alqahtani, H., & Kalim, A. (2020). K-Nearest Neighbor Learning based Diabetes Mellitus Prediction and Analysis for eHealth Services. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Scalable Information Systems, 7(26), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Shekar, S., Mohamed, M., & Xavier, B. (2022). Bankruptcy Prediction Using Machine Learning Methods. Information Society, 1, 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K. S., & Lee, K. J. (2004). Neuro-genetic approach for bankruptcy prediction modeling. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3214, 646–652. [CrossRef]

- Smiti, S., & Soui, M. (2020). Bankruptcy Prediction Using Deep Learning Approach Based on Borderline SMOTE. Information Systems Frontiers, 22(5), 1067–1083. [CrossRef]

- Smiti, S., Soui, M., & Ghedira, K. (2022). Tri-XGBoost Model: An Interpretable Semi-supervised Approach for Addressing Bankruptcy Prediction. 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B., Cheng, W., Goswami, P., & Bai, G. (2018). Short-term traffic forecasting using self-adjusting k-nearest neighbours. IET Intelligent Transport Systems, 12(1), 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Li, H., Huang, Q. H., & He, K. Y. (2014). Predicting financial distress and corporate failure: A review from the state-of-the-art definitions, modeling, sampling, and featuring approaches. Knowledge-Based Systems, 57, 41–56. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Ji, J., Zhu, Y., Gao, S., Tang, Z., & Todo, Y. (2019). A Differential Evolution-Oriented Pruning Neural Network Model for Bankruptcy Prediction. Complexity, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tesyon Korjo Hwase, & Abdul Joseph Fofanah. (2021). Machine Learning Model Approaches for Price Prediction in Coffee Market using Linear Regression, XGB, and LSTM Techniques. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, 10–48. [CrossRef]

- Torlay, L., Perrone-Bertolotti, M., Thomas, E., & Baciu, M. (2017). Machine learning–XGBoost analysis of language networks to classify patients with epilepsy. Brain Informatics, 4(3), 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, M., & Aksoy, H. (2006). Prediction of corporate financial distress in an emerging market: The case of Turkey. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 13(4), 277–295. [CrossRef]

- Vanhaeren, T., Divina, F., García-Torres, M., Gómez-Vela, F., Vanhoof, W., & García, P. M. M. (2020). A comparative study of supervised machine learning algorithms for the prediction of long-range chromatin interactions. Genes, 11(9), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Yuan, G., Guo, C., & Li, Z. (2022). Research on fault diagnosis method of aviation cable based on improved Adaboost. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 14(9), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Chen, H., Li, H., Cai, Z., Zhao, X., Tong, C., Li, J., & Xu, X. (2017). Grey wolf optimization evolving kernel extreme learning machine: Application to bankruptcy prediction. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 63, 54–68. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Li, D., Cui, D., & Ma, X. (2022). governance disclosure and corporate sustainable growth : Evidence from China. October, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wyner, A. J., Olson, M., Bleich, J., & Mease, D. (2017). Explaining the success of adaboost and random forests as interpolating classifiers. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 18, 1–33.

- Xu, Y., Yu, Z., Cao, W., & Chen, C. L. P. (2023). A Novel Classifier Ensemble Method Based on Subspace Enhancement for High-Dimensional Data Classification. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 35(1), 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Yotsawat, W., Phodong, K., Promrat, T., & Wattuya, P. (2023). Bankruptcy prediction model using cost-sensitive extreme gradient boosting in the context of imbalanced datasets. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 13(4), 4683–4691. [CrossRef]

- Yotsawat, W., Wattuya, P., & Srivihok, A. (2021). Improved credit scoring model using XGBoost with Bayesian hyper-parameter optimization. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 11(6), 5477–5487. [CrossRef]

- Youn, H., & Gu, Z. (2010). Predict US Restaurant Firm Failures: The Artificial Neural Network Model versus Logistic Regression Model. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(3), 171–187. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G., Hu, M. Y., Patuwo, B. E., & Indro, D. C. (1999). Artificial neural networks in bankruptcy prediction: general framework and cross-validation analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 116(1), 16–32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Chen, X., Liu, Y., & Xi, Q. (2020). A Distributed Storage and Computation k-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm Based Cloud-Edge Computing for Cyber-Physical-Social Systems. IEEE Access, 8, 50118–50130. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Guo, Y., Yuan, J., Wu, M., Li, D., Zhou, Y., & Kang, J. (2018). ESG and corporate financial performance: Empirical evidence from China’s listed power generation companies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(8), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zizi, Y., Jamali-Alaoui, A., El Goumi, B., Oudgou, M., & El Moudden, A. (2021). An optimal model of financial distress prediction: A comparative study between neural networks and logistic regression. Risks, 9(11). [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., Gao, C., & Gao, H. (2022). Business Failure Prediction Based on a Cost-Sensitive Extreme Gradient Boosting Machine. IEEE Access, 10, 42623–42639. [CrossRef]

| ESG | P1 | P7 | P8 | L2 | L3 | AC1 | |

| ESG | 1 | ||||||

| P1 | 0.046 | 1 | |||||

| P7 | -0.029 | 0.079 | 1 | ||||

| P8 | 0.021 | 0.024 | -0.628 | 1 | |||

| L2 | -0.083 | -0.031 | 0.065 | 0.026 | 1 | ||

| L3 | -0.108 | -0.039 | -0.003 | -0.009 | 0.08 | 1 | |

| AC1 | -0.058 | -0.001 | -0.004 | -0.006 | -0.069 | 0.014 | 1 |

| Model(s) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Overall Accuracy | |||

| Failed | Non-Failed | Failed | Non-Failed | Failed | Non-Failed | ||

| Logistic Regression | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 93.39% |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 99.15% |

| Decision Tree | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 98.51% |

| SVM (Linear Kernel) | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 93.60% |

| SVM (RBF Kernel) | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 95.10% |

| Neural Network | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 97.65% |

| Random Forest | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 99.57% |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 98.93% |

| XgBoost Classifier | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 99.15% |

| AdaBoost Classifier | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 96.38% |

| CatBoost Classifier | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 99.57% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).