Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

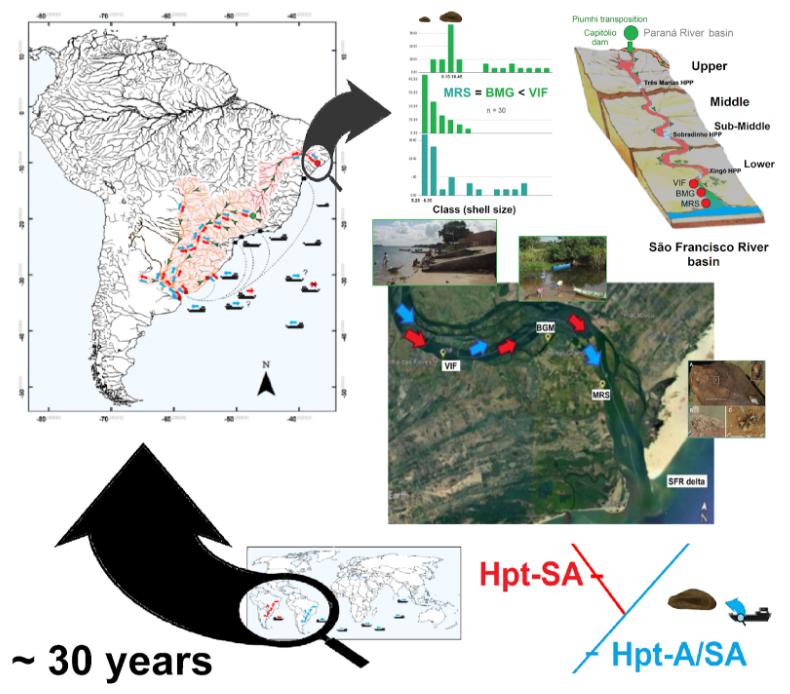

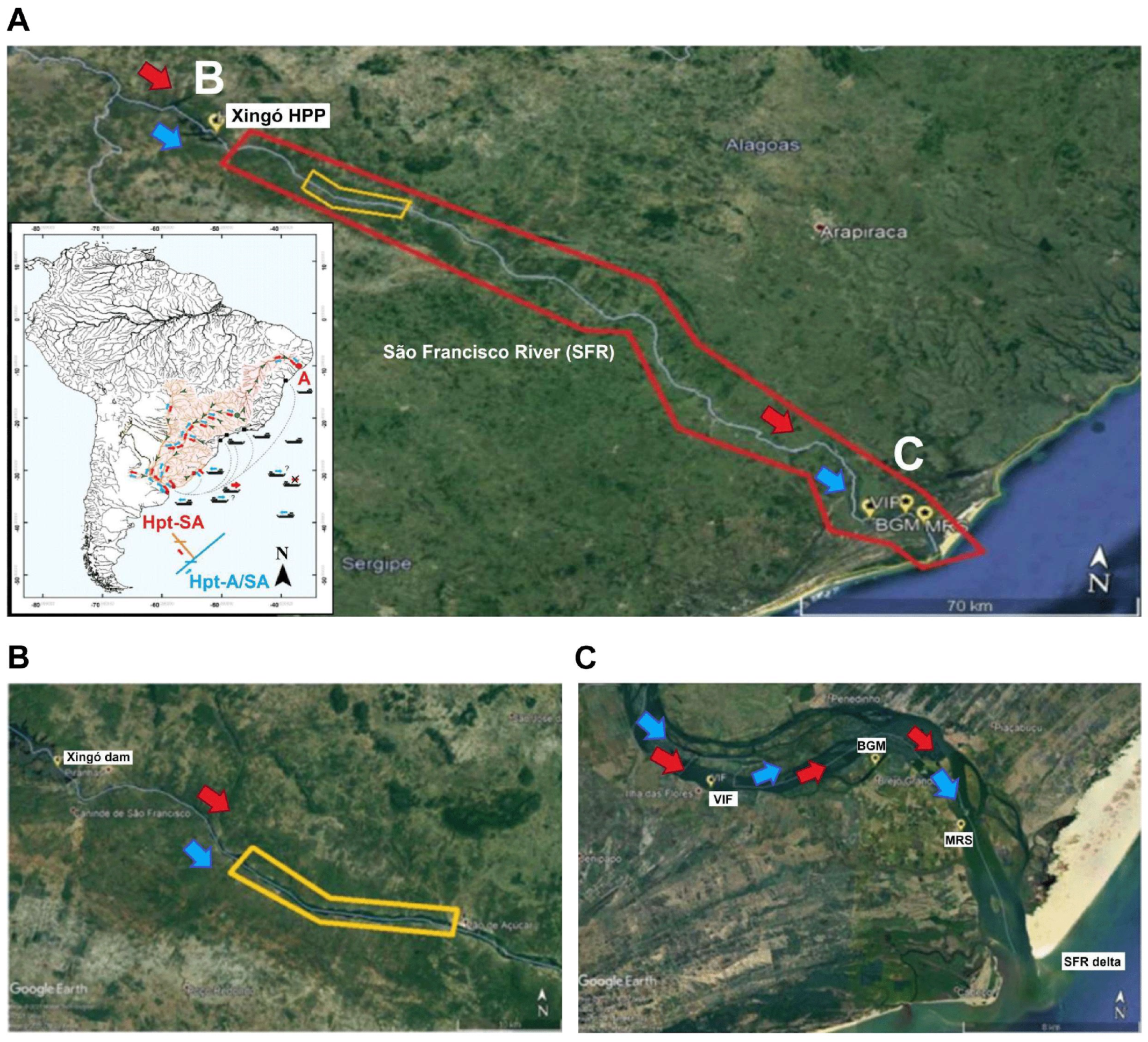

2.1. São Francisco River

2.2. Collected Specimens

2.3. Identification and Biometry

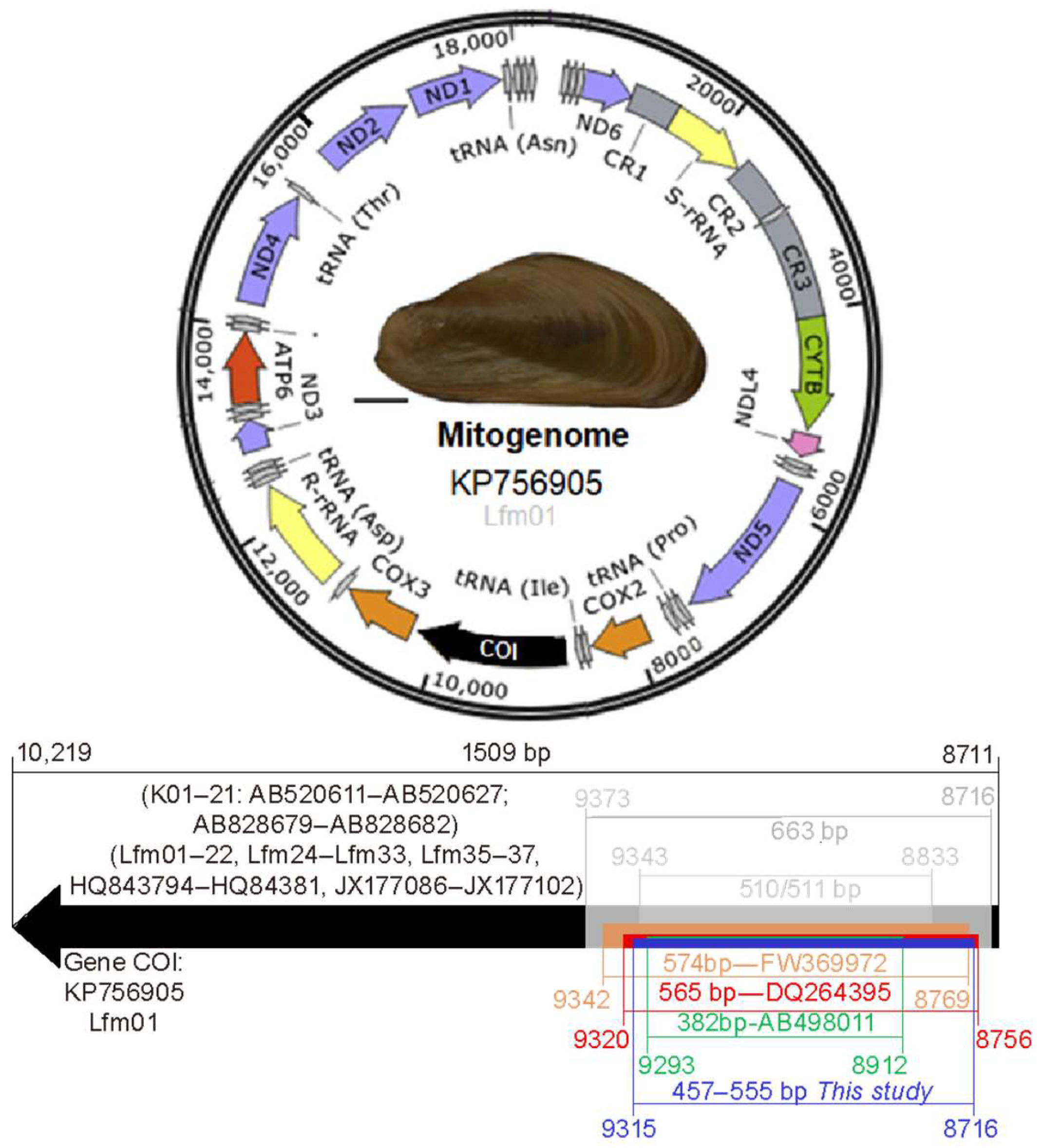

2.4. Identification of DNA Footprints and Dispersal Route

3. Results

3.1. Mussel Occurrence

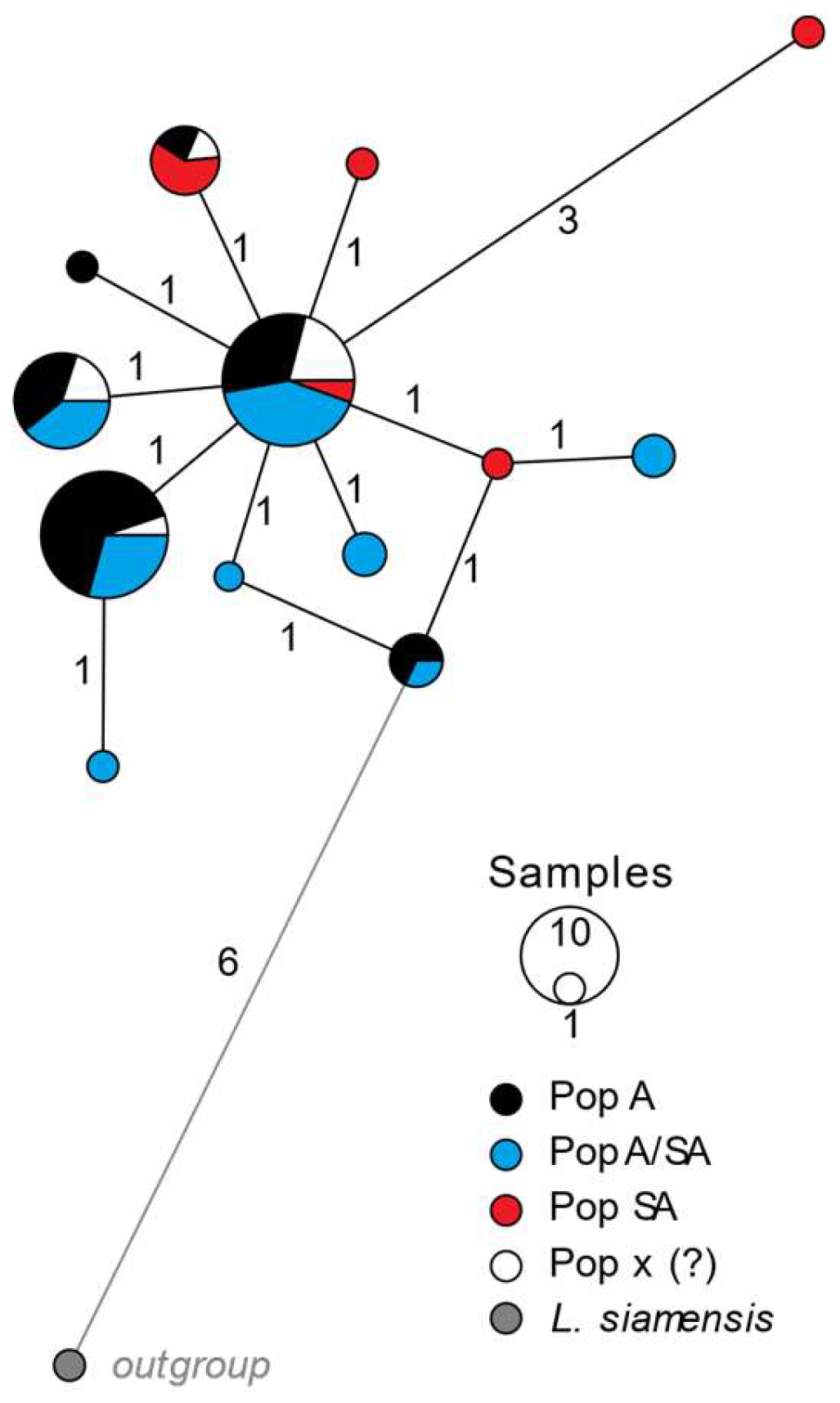

3.2. Mussel Identification and DNA Footprints

4. Discussion

4.1. Cox1 Barcode Annotation and Haplotypes in the Golden Mussel

4.2. Identified Footprints and Possible Origins

4.3. An Intracontinental Route to Northeastern Brazil

4.4. Golden Mussel and Human Activities in Northeastern Brazil

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKindsey, C.W.; Landry, T.; O’Beirn, F.X.; Davies, I.M. Bivalve aquaculture and exotic species: A review of ecological considerations and management issues. J. Shellfish Res. 2007, 26, 281–294. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, P.W.; Kregting, L.; Dick, J.T. Relative impacts of the invasive Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, over the native blue mussel, Mytilus edulis, are mediated by flow velocity and food concentration. NeoBiota 2019, 45, 19–37. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.S.V.; Fernandes, F.C.; Souza, R.C.C.L.; Larsen, K.T.S.; Danelon, O.M. (Eds.) Água de Lastro e Bioinvasão; Interciência: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004; pp. 33–38.

- Carlton, J.T. Marine Bioinvasions: The alteration of marine ecosystems by non-indigenous species. Oceanography 1996, 9, 36–43.

- Boltovskoy, D.; Correa, N.M.; Burlakova, L.E.; Karatayev, A.Y.; Thuesen, E.V.; Sylvester, F.; Paolucci, E.M. Traits and impacts of introduced species: A quantitative review of meta-analyses. Hydrobiologia 2020, 18, 2225–2258. [CrossRef]

- Stenyakina, A.; Walters, L.J.; Hoffman, E.A.; Calestani, C. Food Availability and Sex Reversal in Mytella charruana, an Introduced Bivalve in the Southeastern United States. Mol. Reprod. Dev. Inc. Gamete Res. 2010, 77, 222–230.

- Calazans, C.S.H.; Walters, L.J.; Fernandes, F.C.; Ferreira, C.E.; Hoffman, E.A. Genetic structure provides insights into the geographic origins and temporal change in the invasive charru mussel (Sururu) in the southeastern United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180619. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Tay, T.S.; Lim, C.S.; Lee, S.S.; Teo, S.M.; Tan, K.S. Mytella strigata (Bivalvia: Mytilidae): An alien mussel recently introduced to Singapore and spreading rapidly. Molluscan Res. 2018, 38, 170–186.

- Giglio, M.L.; Dreher Mansur, M.C.; Damborenea, C.; Penchaszadeh, P.E.; Darrigran, G. Reproductive pattern of the aggressive invader Limnoperna fortunei (Bivalvia, Mytilidae) in South America. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 60, 175–184.

- Adelino, J.R.P.; Heringer, G.; Diagne, C.; Courchamp, F.; Faria, L.D.B.; Zenni, R.D. The economic costs of biological invasions in Brazil: A first assessment. NeoBiota 2021, 67, 349–374. [CrossRef]

- Morton, B. Some aspects of the biology and functional morphology of the organs of feeding and digestion of Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker) (Bivalvia: Mytilacea). Malacologia 1973, 12, 265–281.

- Pastorino, G.; Darrigran, G.; Martín, S.M.; Lunaschi, L. Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mytilidae), nuevo bivalvo invasor en aguas del Río de la Plata. Neotropica 1993, 39, 101–102.

- Xu, M. Distribution and spread of Limnoperna fortunei in China. In Limnoperna Fortunei; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 313–320.

- Mansur, M.C.D.; Santos, C.P.; Darrigran, G.; Heydrich, I.; Callil, C.T.; Cardoso, F.R. Primeiros dados quali-quantitativos do mexilhão-dourado, Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker), no Delta do Jacuí, no Lago Guaíba e na Laguna dos Patos, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil e alguns aspectos de sua invasão no novo ambiente. Rev. Bras. Zool. 2003, 20, 75–84.

- Barbosa, F.G.; Melo, A.S. Modelo preditivo de sobrevivência do Mexilhão Dourado (Limnoperna fortunei) em relação a variações de salinidade na Laguna dos Patos, RS, Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2009, 9, 407–412.

- Santos, F.J.M.; Peña, A.P.; Luz, V.L.F. Considerações biogeográficas sobre a herpetofauna do submédio e da foz do rio São Francisco, Brasil. Estudos 2008, 35, 57–78.

- Barbosa, N.P.U.; Silva, F.A.; De Oliveira, M.D.; Neto, M.A.S.; De Carvalho, M.D.; Cardoso, A.V. Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Mytilidae): First record in the São Francisco River basin, Brazil. Check List 2016, 12, 1846.

- Deaton, L.E.; Derby, J.G.; Subhedar, N.; Greenberg, M.J. Osmoregulation and salinity tolerance in two species of bivalve mollusc: Limnoperna fortunei and Mytilopsis leucophaeta. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1989, 133, 67–79. [CrossRef]

- Angonesi, L.G.; Rosa, N.G.; Bemvenuti, C.E. Tolerance to salinities shocks of the invasive mussel Limnoperna fortunei under experimental conditions. Iheringia Série Zool. 2008, 98, 66–69.

- Sylvester, F.; Cataldo, D.H.; Notaro, C.; Boltovskoy, D. Fluctuating salinity improves survival of the invasive freshwater golden mussel at high salinity: Implications for the introduction of aquatic species through estuarine ports. Biol. Invasions 2013, 15, 1355–1366. [CrossRef]

- Lucía, M.; Darrigran, G.; Gutierrez Gregoric, D.E. The most problematic freshwater invasive species in South America, Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857), and its status after 30 years of invasion. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 85, 5. [CrossRef]

- Darrigran, G. Potential impact of filter-feeding invaders on temperate inland freshwater environments. Biol. Invasions 2002, 4, 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Karatayev, A.Y.; Boltovskoy, D.; Burlakova, L.E.; Padilla, D.K. Parallels and contrasts between Limnoperna fortunei and dreissena species. In Limnoperna Fortunei: The Ecology, Distribution and Control of a Swiftly Spreading Invasive Fouling Mussel; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 261–297.

- Darrigran, G.; Penchaszadeh, P.; Damborenea, C. The reproductive cycle of Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mytilidae) from a Neotropical Temperate Locality. J. Shellfish Res. 1999, 18, 361–365.

- Karatayev, A.Y.; Boltovskoy, D.; Padilla, D.K.; Burlakova, L.E. The invasive bivalves dreissena polymorpha and Limnoperna fortunei: Parallels, contrasts, potential spread and invasion impacts. J. Shellfish Res. 2007, 26, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Darrigran, G.; Damborenea, C. A South American bioinvasion case history: Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857), the golden mussel. Amer. Malac. Bull. 2005, 20, 105–112.

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente—MMA. Diagnóstico Sobre a Invasão do Mexilhão-Dourado (Limnoperna fortunei) no Brasil; Ministério do Meio Ambiente—Instituto do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis—IBAMA: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; p. 159.

- Ludwig, S.; Sari, E.H.; Paixão, H.; Montresor, L.C.; Araújo, J.; Brito, C.F.; Martinez, C.B. High connectivity and migration potentiate the invasion of Limnoperna fortunei (Mollusca: Mytilidae) in South America. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 499–513. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.D.; Ayroza, D.M.R.; Castellani, D.; Campos, M.C.S.; Mansur, M.C.D. O mexilhão dourado nos tanques-rede das pisciculturas das Regiões Sudeste e Centro-Oeste. Panor. Aqüicultura 2014, 24, 22–29.

- Darrigran, G.; Agudo-Padrón, I.; Baez, P.; Belz, C.; Cardoso, F.; Carranza, A.; Damborenea, C. Non-native mollusks throughout South America: Emergent patterns in an understudied continent. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 853–871. [CrossRef]

- Mansano, C.F.M.; Pereira, B.C.A.; Gonçalves, G.S.; Nascimento, T.M.T. Sustainable alternative for the use of invasive species of golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) in the feeding of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2023, 51, 692–702. [CrossRef]

- Darrigran, G.; Damborenea, C. Ecosystem Engineering Impact of Limnoperna fortunei in South America. Zool. Sci. 2011, 28, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Hamilton, S.; Jacobi, C. Forecasting the expansion of the invasive golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei in Brazilian and North American rivers based on its occurrence in the Paraguay River and Pantanal wetland of Brazil. Aquat. Invasions 2010, 5, 59–73. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.M.E.; Theodoro Junior, N.; Souza, R.F.M. Ocorrência do mexilhão-dourado (Limnoperna fortunei, Dunker 1857) no Canal do Sertão, Delmiro Gouveia-AL, Brasil. Rev. Gestão Água Am. Lat. 2022, 19, e18. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.D.; Campos, M.C.S.; Paolucci, E.M.; Mansur, M.C.D.; Hamilton, S.K. Colonization and Spread of Limnoperna fortunei in South America. In Limnoperna Fortunei; Boltovskoy, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 333–355. [CrossRef]

- Darrigran, G.; de Drago, I.E. Distribución de Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mytilidae), en La Cuenca Del Plata, Region Neotropical. Medio Ambiente 2000, 13, 75–79.

- Boltovskoy, D.; Correa, N.; Cataldo, D.; Sylvester, F. Dispersion and Ecological Impact of the Invasive Freshwater Bivalve Limnoperna fortunei in the Río de la Plata Watershed and Beyond. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 947–963. [CrossRef]

- Boltovskoy, D. Limnoperna fortunei: The Ecology, Distribution and Control of a Swiftly Spreading Invasive Fouling Mussel; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; p. 476.

- Morton, B. The Biology and Anatomy of Limnoperna fortunei, a Significant Freshwater Bioinvader: Blueprints for Success. In Limnoperna fortunei; Boltovskoy, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–41. [CrossRef]

- Pie, M.R.; Boeger, W.A.; Patella, L.; Falleiros, R.M. A fast and accurate molecular method for the detection of larvae of the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei (Mollusca: Mytilidae) in plankton samples. J. Molluscan Stud. 2006, 72, 218–219. [CrossRef]

- Mansur, M.C.D. Bivalves invasores límnicos: Morfologia comparada de Limnoperna fortunei e espécies de Corbicula spp. In Moluscos Límnicos Invasores No Brasil: Biologia, Prevencão, Controle; Redes Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012; pp. 61–74.

- Vidigal, T.H.D.A.; Coscarelli, D.; Monstresor, L.C. Molecular studies in Brazilian malacology: Tools, trends and perspectives. Lundiana 2013, 11, 47–63. [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, A.; Goka, K.; Kimura, T.; Ito, K. Genetic structure of Japanese introduced populations of the golden mussel, Limnoperna fortunei, and the estimation of their range expansion process. Biodiversity 2009, 10, 61–66. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, A.; Perepelizin, P.V.; Ghabooli, S.; Paolucci, E.; Sylvester, F.; Sardiña, P.; Cristescu, M.E.; MacIsaac, H.J. Scale-dependent post-establishment spread and genetic diversity in an invading mollusc in South America: Invasion genetics of Limnoperna fortunei. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 18, 1042–1055. [CrossRef]

- Ghabooli, S.; Zhan, A.; Sardiña, P.; Paolucci, E.; Sylvester, F.; Perepelizin, P.V.; Cristescu, M.E. Genetic diversity in introduced golden mussel populations corresponds to vector activity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59328. [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, E.M.; Sardiña, P.; Sylvester, F.; Perepelizin, P.V.; Zhan, A.; Ghabooli, S.; Cristescu, M.E.; Oliveira, M.D.; MacIsaac, H.J. Morphological and genetic variability in an alien invasive mussel across an environmental gradient in South America. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2014, 59, 400–412. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, D.; Baba, T.; Endo, N.; Nagayama, S.; Fujinaga, A.; Uchida, A.; Shiragane, A.; Urabe, M.; Kobayashi, T. Invasion, dispersion, population persistence and ecological impacts of a freshwater mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) in the Honshu Island of Japan. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 743–759. [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.D.; Ludwig, S.; Boeger, W.A. Testing hypotheses on the origin and dispersion of Limnoperna fortunei (Bivalvia, Mytilidae) in the Iguassu River (Paraná, Brazil): Molecular markers in larvae and adults. Limnology 2017, 18, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Ovenden, J. Mitochondrial DNA and marine stock assessment: A review. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1990, 41, 835. [CrossRef]

- Rubinoff, D. Utility of mitochondrial DNA barcodes in species conservation: DNA barcodes and conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1026–1033. [CrossRef]

- Pečnikar, F.Ž.; Buzan, E.V. 20 years since the introduction of DNA barcoding: From theory to application. J. Appl. Genet. 2014, 55, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, R.A.C. Mapeamento Temático de Uso da Terra no Baixo São Francisco. In Projeto de Gerenciamento Integrado das Atividades Desenvolvidas em Terra na Bacia do São Francisco; CODEVASP, Brasilia, DF, Brazil, 2002; pp. 1-35. https://cdn.agenciapeixevivo.org.br/.

- Moreira Filho, O.; Buckup, P.A. A poorly known case of watershed transposition between the São Francisco and upper Paraná river basins. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2005, 3, 449–452. [CrossRef]

- Bot Neto, R.L.; Cattani, A.P.; Spach, H.L.; Contente, R.F.; Cardoso, O.R.; Marion, C.; Schwarz Júnior, R. Patterns in composition and occurrence of the fish fauna in shallow areas of the São Francisco River mouth. Biota Neotrop. 2023, 23, e20221387. [CrossRef]

- Christo, S.W.; Ferreira-Junior, A.L.; Absher, T.M. Aspectos reprodutivos de mexilhões (Bivalvia, Mollusca) no complexo estuarino de Paranaguá, Paraná, Brasil. Bol. Do Inst. Pesca 2016, 42, 924–936. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Fritsch, E.F.; Maniatis, T. Extraction and Purification of Plasmid DNA. In Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 21–152.

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299.

- Alves, F.A.; Beasley, C.R.; Hoeh, W.R.; da Rocha, R.M.; Simone, L.R.; Tagliaro, C.H. Detection of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy suggests a doubly uniparental inheritance pattern in the mussel Mytella charruana. Rev. Bras. Biociências 2012, 10, 176.

- Endo, N.; Sato, K.; Nogata, Y. Molecular based method for the detection and quantification of larvae of the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei using real-time PCR. Plankton Benthos Res. 2009, 4, 125–128. [CrossRef]

- Vermulm Junior, H.; Giamas, M.T.D. Ocorrência do mexilhão-dourado Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mollusca; Bivalvia; Mytilidae), no trato digestivo do “Armal” Pterodoras granulosus (Valenciennes, 1821) (Siluriformes; Doradidae), do Rio Paraná, São Paulo, Brasil. Bol. Do Inst. De Pesca 2008, 34, 175–179.

- Canzi, C.; Fialho, N.S.; Bueno, G.W. Monitoramento e ocorrência do mexilhão dourado (Limnoperna fortunei) na hidrelétrica da Itaipu binacional, Paraná (BR). Rev. Ibero-Am. Ciências Ambient. 2014, 5, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.; Cordeiro, N.I.; Montressor, L.C.; Luz, D.M.; Luz, R.C.; Martinez, C.B.; Vidigal, T.H. Effect of temperature on behavior, glycogen content, and mortality in Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). J. Limnol. 2018, 77, 189–198. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.P.; Lopes, M.N. Size-selective predation of the catfish Pimelodus pintado (Siluriformes: Pimelodidae) on the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). Zoologia 2013, 30, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Vieira, J. Predadores potenciais para o controle do mexilhão-dourado. In Moluscos Límnicos Invasores No Brasil: Biologia, Prevenção, Controle; Redes Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012; pp. 357–363.

- Uliano-Silva, M.; Americo, J.A.; Costa, I.; Schomaker-Bastos, A.; de Freitas Rebelo, M.; Prosdocimi, F. The complete mitochondrial genome of the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei and comparative mitogenomics of Mytilidae. Gene 2016, 577, 202–208. [CrossRef]

- Pessotto, M.A.; Nogueira, M.G. More than two decades after the introduction of Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker 1857) in La Plata Basin. Braz. J. Biol. 2018, 78, 773–784. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.G.; Soares-Souza, G.B.; Americo, J.A.; Dumaresq, A.; Rebelo, M.F. Population structure of the invasive golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) on reservoirs from five Brazilian drainage basins. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Correia, I.O.; da Silva Andrade, A.C.; de Rezende, P.S. Erosão costeira e faixas de proteção no delta do rio São Francisco. Quat. Environ. Geosci. 2023, 14, 26–42.

- Silva, W.F. Determinação da carga de material em suspensão no rio São Francisco: Ano hidrológico 2007. Universidade Federal de Alagoas: Maceió, Brazil, 2009; p. 48.

- de Castro, C.N.; Pereira, C.N. Revitalização da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio São Francisco: Histórico. In Diagnóstico e Desafios; Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; p. 366.

- Darrigran, G.; Pastorino, G. The recent introduction of a freshwater asiatic bivalve Limnoperna fortunei (Mytilidae) into South America. Veliger 1995, 32, 171–175.

- Giraudo, M.E. Dependent development in South America: China and the soybean nexus. J. Agrar. Chang. 2020, 20, 60–78. [CrossRef]

- Costa Fernandes, F.; Mansur, M.C.D.; Pereira, D.; de Godoy Fernandes, L.V.; Campos, S.C.; Danelon, O.M. Abordagem Conceitual dos Moluscos Invasores nos Ecossistemas Límnicos Brasileiros. In Moluscos Límnicos Invasores No Brasil: Biologia, Prevenção, Controle; Redes Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012; pp. 19–23.

- Yuan, W.; Walters, L.J.; Schneider, K.R.; Hoffman, E.A. Exploring the survival threshold: A study of salinity tolerance of the nonnative mussel Mytella charruana. J. Shellfish Res. 2010, 29, 415–422. [CrossRef]

- Peres, W.A.M.; Bertollo, L.A.C.; Buckup, P.A.; Blanco, D.R.; Kantek, D.L.Z.; Moreira-Filho, O. Invasion, dispersion and hybridization of fish associated to river transposition: Karyotypic evidence in “Astyanax bimaculatus group” (Characiformes: Characidae). Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2012, 22, 519–526. [CrossRef]

- de O. Mendes-Neto, E.; Vicari, M.R.; Artoni, R.; Moreira-Filho, O. Description of karyotype in Hypostomus regani (Ihering, 1905) (Teleostei, Loricariidae) from the Piumhi river in Brazil with comments on karyotype variation found in Hypostomus. Comp. Cytogenet. 2011, 5, 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.P.U.; Ferreira, J.A.; Nascimento, C.A.R.; Silva, F.A.; Carvalho, V.A.; Xavier, E.R.S.; Ramon, L.; Almeida, A.C.; Carvalho, M.D.; Cardoso, A.V. Prediction of future risk of invasion by Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Mytilidae) in Brazil with cellular automata. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 92, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.; Fusaro, A.; Sturtevant, R.; Kashian, D. Development of a risk assessment framework to predict invasive species establishment for multiple taxonomic groups and vectors of introduction. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2017, 8, 25–36. [CrossRef]

- Correa, N.; Sardiña, P.; Perepelizin, P.V.; Boltovskoy, D. Limnoperna fortunei colonies: Structure, Distribution and Dynamics. In Limnoperna Fortunei; Boltovskoy, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 119–143.

- Darrigran, G.; Damborenea, C.; Drago, E.C.; Ezcurra de Drago, I.; Paira, A.; Archuby, F. Invasion process of Limnoperna fortunei (Bivalvia: Mytilidae): The case of Uruguay River and emissaries of the Esteros del Iberá Wetland, Argentina. Zoologia 2012, 29, 531–539. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. Distribution and spread of Limnoperna fortunei in Japan. In Limnoperna Fortunei—The Ecology, Distribution and Control of a Swiftly Spreading Invasive Fouling Mussel; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 321–332.

- Furlan-Murari, P.J.; Ruas, C.D.F.; Ruas, E.A.; Benício, L.M.; Urrea-Rojas, A.M.; Poveda-Parra, A.R.; Lopera-Barrero, N.M. Structure and genetic variability of golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) populations from Brazilian reservoirs. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 2706–2714. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Neto, T.F.; Silva, A.H.G.D.; Guimarães, I.M.; Gomes, M.V.T. Piscicultura familiar extensiva no baixo São Francisco, estado de Sergipe, Brasil. Acta Fish. Aquat. Resour. 2016, 4, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- de Farias Costa, E.; Sampaio, Y. Direct and indirect job generation in the farmed shrimp production chain 1. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2004, 8, 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Sá, T.D.; Sousa, R.R.d.; Rocha, Í.R.C.B.; Lima, G.C.D.; Costa, F.H.F. Brackish Shrimp Farming in Northeastern Brazil: The Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts and Sustainability. Nat. Resour. 2013, 4, 538–550. [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.C.S.; Andrade, A.F.A.; Kunzmann, B.; Galvão, D.D.; Silva, F.A.; Cardoso, A.V.; Carvalho, M.D.; Mota, H.R. Modelling of the potential distribution of Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker, 1857) on a global scale. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 253–265.

- CTSSBSF. 2016a. Available online: https://issuu.com/canoadocs/docs/alertamexdou-01-2016 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- CTSSBSF. 2016b. Available online: https://issuu.com/canoadocs/docs/alertamexdou-02-2016 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Fonseca, S.L.; Magalhães, A.A.; Campos V.P.; Medeiros Y.D. Effect of the reduction of the outflow restriction discharge from the Xingó dam in water salinity in the lower stretch of the São Francisco River. Revista Brasileira de Recursos Hídricos Brazilian Journal of Water Resources 2020, 25, e4. [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.C.; Danelon, O.M. Abordagem conceitual dos moluscos invasores nos ecossistemas límnicos brasileiros. In Moluscos Límnicos Invasores No Brasil: Biologia, Prevenção, Controle; Redes Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012; pp. 19–23.

- Pereira, C.N.; Souza, J.A.; Almeida, F.G. Aspectos econômicos da região do São Francisco. In Revitalização da Bacia Hidrográfica do rio São Francisco: Histórico, Diagnóstico e Desafios; Castro, C.N.d., Pereira, C.N., Eds.; Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada: Brasília, Brazil, 2003; pp. 100–120.

- Diegues, A.C. An Inventory of Brazilian Wetlands; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1994; 216p.

- Sato, Y.; Godinho, H.P. Peixes da bacia do São Francisco. In Estudos Ecológicos de Comunidades de Peixes Tropicais; Edusp: São Paulo, Brazil, 1999; pp. 401–413.

- Sato, Y.; Godinho, H.P. Migratory fishes of the São Francisco River. In Migratory Fishes of South America: Biology, Fisheries and Conservation Status; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2004; p. 380.

- Barbosa, L.M.; de Lima, C.C.U.; Santos, R.C.D.L.; de Carvalho, J.B.; Santos, C.F.; Albuquerque, A.L. As variações morfológicas do campo de dunas ativas entre Pontal do Peba e a foz do rio São Francisco (AL). IX Congresso da Associação Brasileira de Estudos do Quaternário / II Congresso do Quaternário de Países de Línguas Ibéricas / II Congresso sobre Planejamento e Gestão da Zona Costeira dos Países de Expressão Portuguesa, 2003, 1, 1-3.

- Bittencourt, A.C.S.P.; Martin, L.; Dominguez, J.M.L.; Ferreira, Y.D.A. Evolução paleogeográfica quaternária da costa do Estado de Sergipe e da costa sul do Estado de Alagoas. Rev. Bras. Geociênc. 1983, 13, 93–97.

- Bittencourt, A.C.D.S.P.; Dominguez, J.M.L.; Fontes, L.C.S.; Sousa, D.L.; Silva, I.R.; Da Silva, F.R. Wave refraction, river damming, and episodes of severe shoreline erosion: The São Francisco river mouth, Northeastern Brazil. J. Coast. Res. 2007, 23, 930–938.

- Medeiros, P.P.; dos Santos, M.M.; Cavalcante, G.H.; De Souza, W.F.L.; da Silva, W.F. Características ambientais do Baixo São Francisco (AL/SE): Efeitos de barragens no transporte de materiais na interface continente-oceano. Geochim. Bras. 2014, 28, 65.

- Fontes, A.L. Processos erosivos na desembocadura do Rio São Francisco. In Boletim de Resumos, VIII Congresso da ABEQUA; ABEQUA: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001; pp. 66–67.

- Vieira, C.L.; Gonçalves, V.; Vieira, R.C.; Beserra, M.L. Plano de Manejo Para Área de Proteção Ambiental de Piaçabuçu; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2010.

- Barreto, S.A.; Rodrigues, T.K. Usos e conflitos na Reserva Biológica de Santa Isabel no trecho da zona costeira do Grupo de Bacias Costeiras 01-Sergipe; Seminários Espaços Costeiros: Salvador-Ba, Brazil, 2016.

- Santos, E.A.P.D.; Landim, M.F.; Oliveira, E.V.D.S.; Silva, A.C.C.D.D. Conservação da zona costeira e áreas protegidas: A Reserva Biológica de Santa Isabel (Sergipe) como estudo de caso. Rev. Ambiental 2017,15(3), 41-57.

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791.

- Meyer, C.P.; Paulay, G. DNA barcoding: Error rates based on comprehensive sampling. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e422. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.A.; Boykin, L.M.; Cruickshank, R.H.; Armstrong, K.F. Barcoding’s next top model: An evaluation of nucleotide substitution models for specimen identification. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A. FigTree: Tree Figure Drawing Tool, v1.4.2; Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2012.

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: A computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1657–1659. [CrossRef]

| Location | n | LA ± SD (mm) | LR (mm) a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| São Francisco River ts (−8.54°; −39.456°) | 5 | - - c | 15.00 to 30.00 | [16] |

| Sobradinho reservoir (−9.409; −40.817) | 5 | - - c | 15.00 to 30.00 | [16] |

| Sobradinho hydroelectric (−9.433; −40.828) | 5 | - - c | 15.00 to 30.00 | [16] |

| Ilha da Flores (−10.435°; −36.531°) | 30 | 12.84 ± 4.95 * | 7.44 to 23.79 | T.S. |

| Brejo Grande marine (−10.421°; −36.464°) | 30 | 7.42 ± 1.82 * | 5.36 to 11.75 | T.S. |

| São Francisco River mouth (−10.445°; −36.426°) | 30 | 9.37 ± 4.45 * | 5.25 to 20.14 | T.S. |

| Porto Primavera hydroelectric (−22.474°; −52.474°) | 61 | - - c | 4.00 to 27.00 | [60] b |

| Itaipu reservoir—Paraná river (−24°; −54°) | - - c | - - c | 6.00 to 35.00 | [61] |

| Paraná River (−25.437°; −54.512°) | 800 | - - c | 21.00 to 27.00 | [62] |

| Mirim Lake (−31.799°; −52.382° and −32.116°; −52.582°) | 7789 | - - c | 3.00 to 32.00 | [63] d |

| Mirim Lake (−31.799°; −52.382° and −32.116°;−52.582°) | 147 | - - c | 3.00 to 14.00 | [63] e |

| São Gonçalo channel (−32.148°; −52.625°) | 7776 | - - c | 4.00 to 32.00 | [64] d |

| Distribution | Country | HAPLOTYPES | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | np | Codes $$ | |||||

| A/SA | Taiwan | TW1–TW2 | 2 | Lfm03, Lfm08 | [45] | ||

| A | TW1 | 1 | Lfm19 | ||||

| A/SA | Japan | JP1–JP5; JP7–JP29 | 28 | Lfm03 (=K07,K13 *), Lfm05 (=K09 *), Lfm09 (=K01 *), Lfm11 (=K05, K11, K17, K21 *), Lfm12 (=K12 *), Lfm15, Lfm27 (=K02 *), Lfm28 | [10,11,45,47,59,65] | ||

| A | JP1–JP29 | 29 | Lfm20 * (=K03 *), Lfm21 (=K04, K06 *), Lfm28–Lfm29 (=K10 *), Lfm37(=K08 *), K18 * | ||||

| A/SA | Korea | KR | 1 | Lfm11 | [45] | ||

| A | KR | 1 | Lfm21, Lfm26 | ||||

| A/SA | China | CH1–CH5 | 5 | Lfm02, Lfm03, Lfm06, Lfm11-12, Lfm15, Lfm27, Lfm36, Lfm38, Lfm41-42 | [28,45] | ||

| A | CH1–CH5 | 5 | Lfm21, Lfm24–25, Lfm30-33, Lfm35, Lfm37, Lfm43 | ||||

| SA | Brazil | SOB, VIF, BGM, MRS, CO, COR,VOL,IGA, JUP, POR, BAR, RB, IT1, IT2 *, IRB, MAC, BAL, POA1, SO | 19 | Lfm01, Lfm04, Lfm07, Lfm10, Lfm39 | [28,40] **, [44,45,46,65] *, T.S. |

||

| A/SA | SOB, VIF, BGM, MRS, CO, COR, VOL, IGA, JUP, ROS, POR, BAR, BON, RB, IT1, IT2 *, IT3, CX1 *, CX2, OS *, PQ, MAC, BAL, AMA, DMA, POA2, PEL, SO | 28 | Lfm02, Lfm03, Lfm05, Lfm06, Lfm08-09, Lfm11, Lfm15, Lfm36, Lfm38, Lfm41, Lfm42 | [28,44,45,46], T.S. |

|||

| SA | Uruguay | SG–SL | 2 | Lfm01, Lfm04, Lfm10, | [44,46] | ||

| A/SA | SG–SL | 2 | Lfm03, Lfm05, Lfm09, Lfm11–12, Lfm27 | ||||

| SA | Argentina | YR, YD, PR, FE, CA-1, CA-2, PU, SA, UR, RT, EC, CR, TI, SF, BA, QU, PL, MA | 18 | Lfm01, Lfm04, Lfm07, Lfm13, Lfm16-18 | [44,46] | ||

| A/SA | YR, YD, PR, FE, CA-1, CA-2, PU, SA, UR, RT, EC, CR, TI, SF, BA, QU, PL, PLA, MA | 19 | Lfm02, Lfm03, Lfm05, Lfm06, Lfm08-09, Lfm11, Lfm14, Lfm15 | ||||

| Total populations observed: 88 (37 in Asia and 51 in South America). | |||||||

| Total specimens observed: 2160 (735 in Asia and 1425 in South America). | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).