Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Brain and Mind

3. Measurement of Brain Function

4. Meditation

4.1. Meditation and the Brain

4.2. Meditation as a Tool to Achieve Mystical Experiences

4.3. Focused Research Initiatives on Meditation by Organizations

5. Mantra and Pranayama

6. Religiosity

7. Brain and the Body

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

References

- C. Q. Choi. (February 09, 2016) Mystical Experiences Open a ‘Door of Perception’ in the Brain. Accessed on December 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.livescience.com/53652-brain-origins-of-mysticism-found.html.

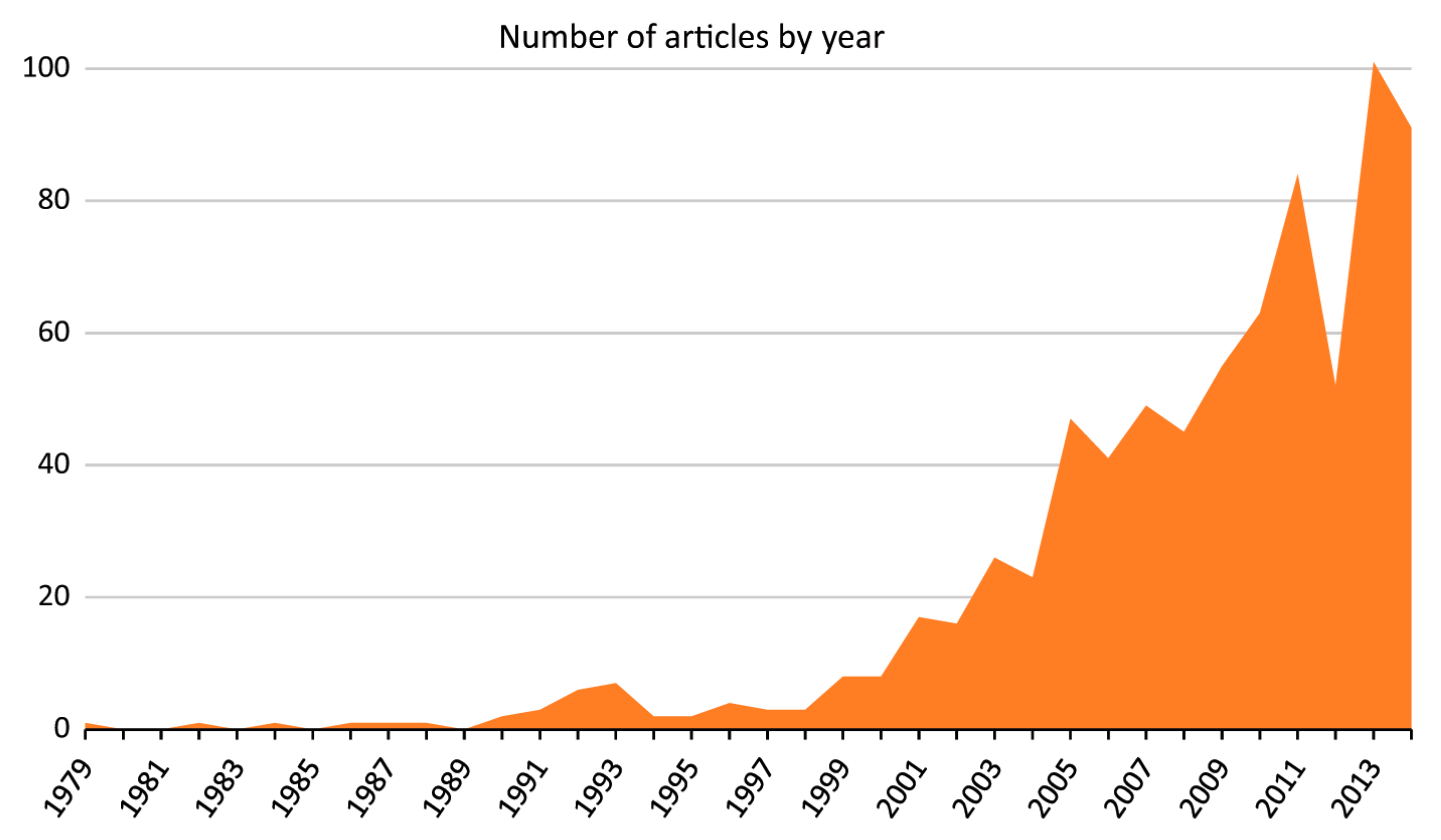

- S. Lauricella, “The ancient-turned-new concept of “spiritual hygiene”: an investigation of media coverage of meditation from 1979 to 2014,” Journal of religion and health, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1748–1762, 2016.

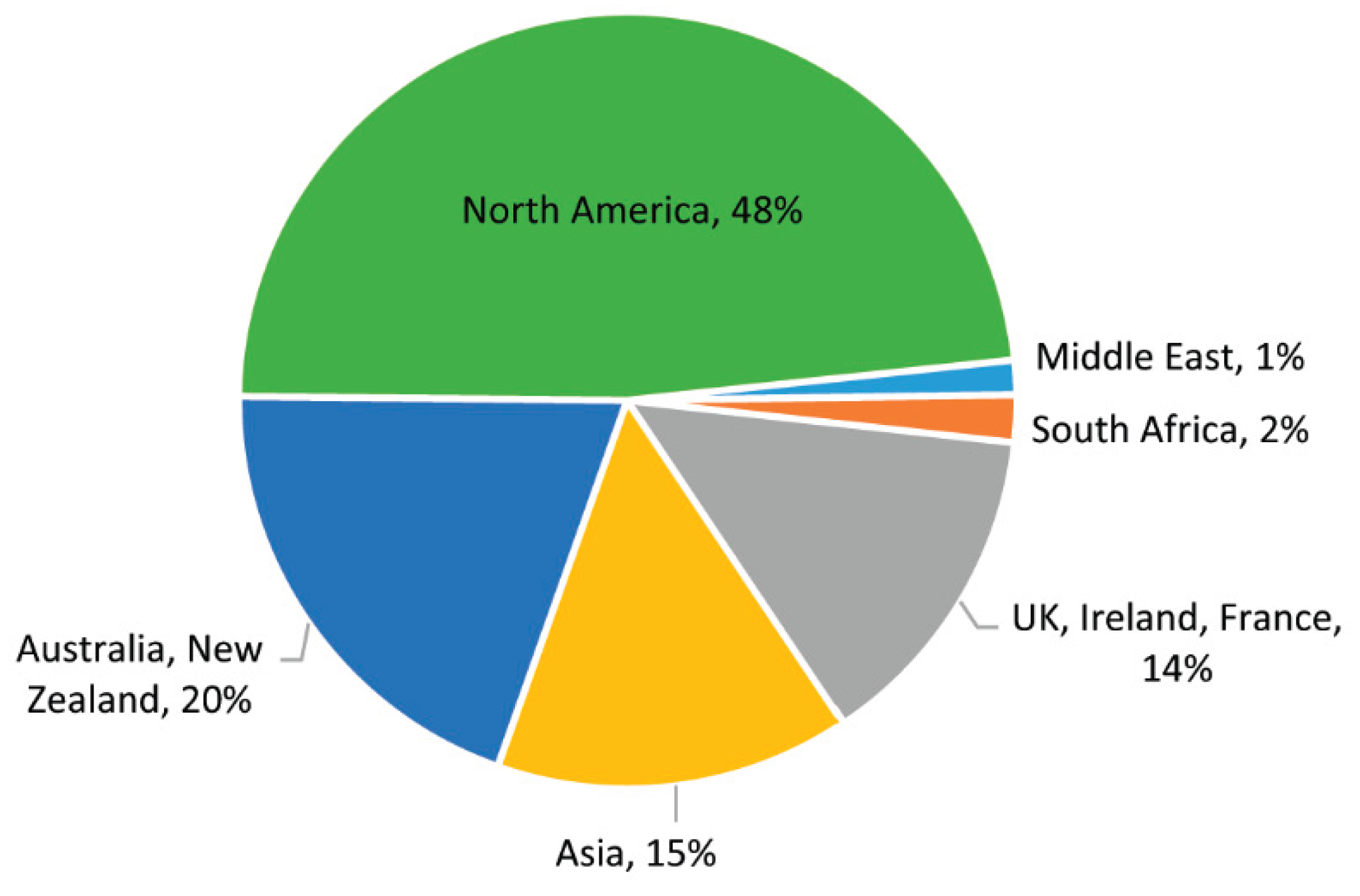

- C. Gururaja, D. Rangaprakash, and G. Deshpande, “Research Trends in the Application of Yoga to Human Health: A Data Science Approach,” International journal of public mental health and neurosciences, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 8, 2020.

- Y. Bhattacharjee, “Neuroscientists welcome Dalai Lama with mostly open arms,” Science, vol. 310, no. 5751, pp. 1104–1104, 2005.

- P. Mergenthaler, U. Lindauer, G. A. Dienel, and A. Meisel, “Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function,” Trends in neurosciences, vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 587–597, 2013.

- M. S. Goyal and M. E. Raichle, “Glucose requirements of the developing human brain,” Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, vol. 66, no. Suppl 3, p. S46, 2018.

- K. Rehni and K. R. Dave, “Impact of hypoglycemia on brain metabolism during diabetes,” Molecular neurobiology, vol. 55, no. 12, pp. 9075–9088, 2018.

- J. M. Rosenthal, S. A. Amiel, L. Yaguez, E. Bullmore, D. Hopkins, M. Evans, A. Pernet, H. Reid, V. Giampietro, C. M. Andrew et al., “The effect of acute hypoglycemia on brain function and activation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study,” Diabetes, vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 1618–1626, 2001.

- G. N. Cantor, J. R. Christie, M. J. S. Hodge, and R. C. Olby, Companion to the history of modern science. Routledge, 2006.

- J. Shaffer, “Neuroplasticity and clinical practice: building brain power for health,” Frontiers in psychology, vol. 7, p. 1118, 2016.

- H. S. Mayberg, A. M. Lozano, V. Voon, H. E. McNeely, D. Seminowicz, C. Hamani, J. M. Schwalb, and S. H. Kennedy, “Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression,” Neuron, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 651–660, 2005.

- K. W. Scangos, A. N. Khambhati, P. M. Daly, G. S. Makhoul, L. P. Sugrue, H. Zamanian, T. X. Liu, V. R. Rao, K. K. Sellers, H. E. Dawes et al., “Closed-loop neuromodulation in an individual with treatment-resistant depression,” Nature Medicine, vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 1696–1700, 2021.

- V. R. Rao, K. K. Sellers, D. L. Wallace, M. B. Lee, M. Bijanzadeh, O. G. Sani, Y. Yang, M. M. Shanechi, H. E. Dawes, and E. F. Chang, “Direct electrical stimulation of lateral orbitofrontal cortex acutely improves mood in individuals with symptoms of depression,” Current Biology, vol. 28, no. 24, pp. 3893–3902, 2018.

- N. Phillips. (April 04, 2018) Brain-stimulation trials get personal to lift depression. Accessed on December 14, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-03864-4.

- J. Kingsland. (January 21, 2021) Personalized brain stimulation lifts a patient’s depression. Accessed on December 20, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/personalized-brain-stimulation-lifts-a-patients-depression.

- D. N. Phillips, K. S. Bonat, N. F. Olumide, and S. Medavarapu, “Importance and effectiveness of brain stimulation in the treatment of depression and insomnia,” Archives of Medicine, vol. 9, no. 1:4, 2017.

- B. Greenberg, L. Gabriels, D. Malone, A. Rezai, G. Friehs, M. Okun, N. Shapira, K. Foote, P. Cosyns, C. Kubu et al., “Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience,” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 64–79, 2010.

- G. Deuschl, C. Schade-Brittinger, P. Krack, J. Volkmann, H. Schafer, K. Botzel, C. Daniels, A. Deutschlander, U. Dillmann, W. Eisner et al., “A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 355, no. 9, pp. 896–908, 2006.

- D.-B. S. for Parkinson’s Disease Study Group, “Deep-brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus or the pars interna of the globus pallidus in Parkinson’s disease,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 345, no. 13, pp. 956–963, 2001.

- R. Fisher, V. Salanova, T. Witt, R. Worth, T. Henry, R. Gross, K. Oommen, I. Osorio, J. Nazzaro, D. Labar et al., “Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy,” Epilepsia, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 899–908, 2010.

- P. R. Schuurman, D. A. Bosch, P. M. Bossuyt, G. J. Bonsel, E. J. Van Someren, R. M. De Bie, M. P. Merkus, and J. D. Speelman, “A comparison of continuous thalamic stimulation and thalamotomy for suppression of severe tremor,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 342, no. 7, pp. 461–468, 2000.

- M. Vidailhet, L. Vercueil, J.-L. Houeto, P. Krystkowiak, A.-L. Benabid, P. Cornu, C. Lagrange, S. Tezenas du Montcel, D. Dormont, S. Grand et al., “Bilateral deep-brain stimulation of the globus pallidus in primary generalized dystonia,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 352, no. 5, pp. 459–467, 2005.

- Kupsch, S. Klaffke, A. Ku¨hn, W. Meissner, G. Arnold, G. Schneider, K. Maier-Hauff, and T. Trottenberg, “The effects of frequency in pallidal deep brain stimulation for primary dystonia,” Journal of Neurology, vol. 250, pp. 1201–1205, 2003.

- M. J. Nelson, I. El Karoui, K. Giber, X. Yang, L. Cohen, H. Koopman, S. S. Cash, L. Naccache, J. T. Hale, C. Pallier et al., “Neurophysiological dynamics of phrase-structure building during sentence processing,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 18, pp. E3669–E3678, 2017.

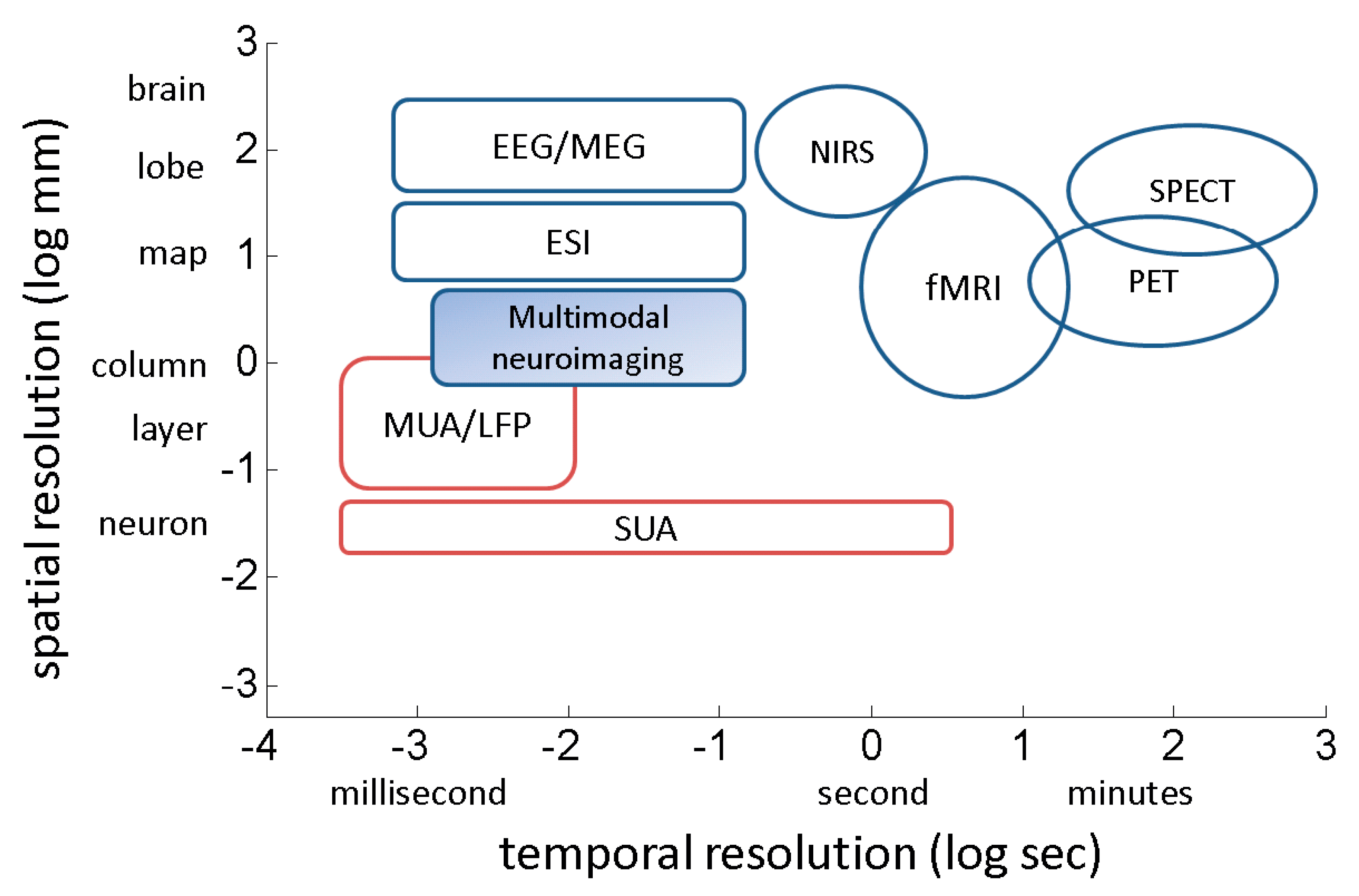

- B. He and Z. Liu, “Multimodal functional neuroimaging: integrating functional MRI and EEG/MEG,” IEEE reviews in biomedical engineering, vol. 1, pp. 23–40, 2008.

- M. A. Shampo and R. A. Kyle, “Felix Bloch—developer of magnetic resonance imaging,” in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 70, no. 9. Elsevier, 1995, p. 889.

- M. A. Shampo and R. A. Kyle, “Edward M. Purcell—Nobel Prize for Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 72, no. 6. Elsevier, 1997, p. 585.

- J. Gore, “Out of the shadows—MRI and the Nobel Prize,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 349, no. 24, pp. 2290–2292, 2003.

- S. Ogawa, T.-M. Lee, A. R. Kay, and D. W. Tank, “Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 87, no. 24, pp. 9868–9872, 1990.

- S. Ogawa, T.-M. Lee, A. S. Nayak, and P. Glynn, “Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 68–78, 1990.

- K. K. Kwong, J. W. Belliveau, D. A. Chesler, I. E. Goldberg, R. M. Weisskoff, B. P. Poncelet, D. N. Kennedy, B. E. Hoppel, M. S. Cohen, R. Turner, and et al., “Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 89, no. 12, p. 5675–5679, 1992.

- P. A. Bandettini, E. C. Wong, R. S. Hinks, R. S. Tikofsky, and J. S. Hyde, “Time course EPI of human brain function during task activation,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 390–397, 1992.

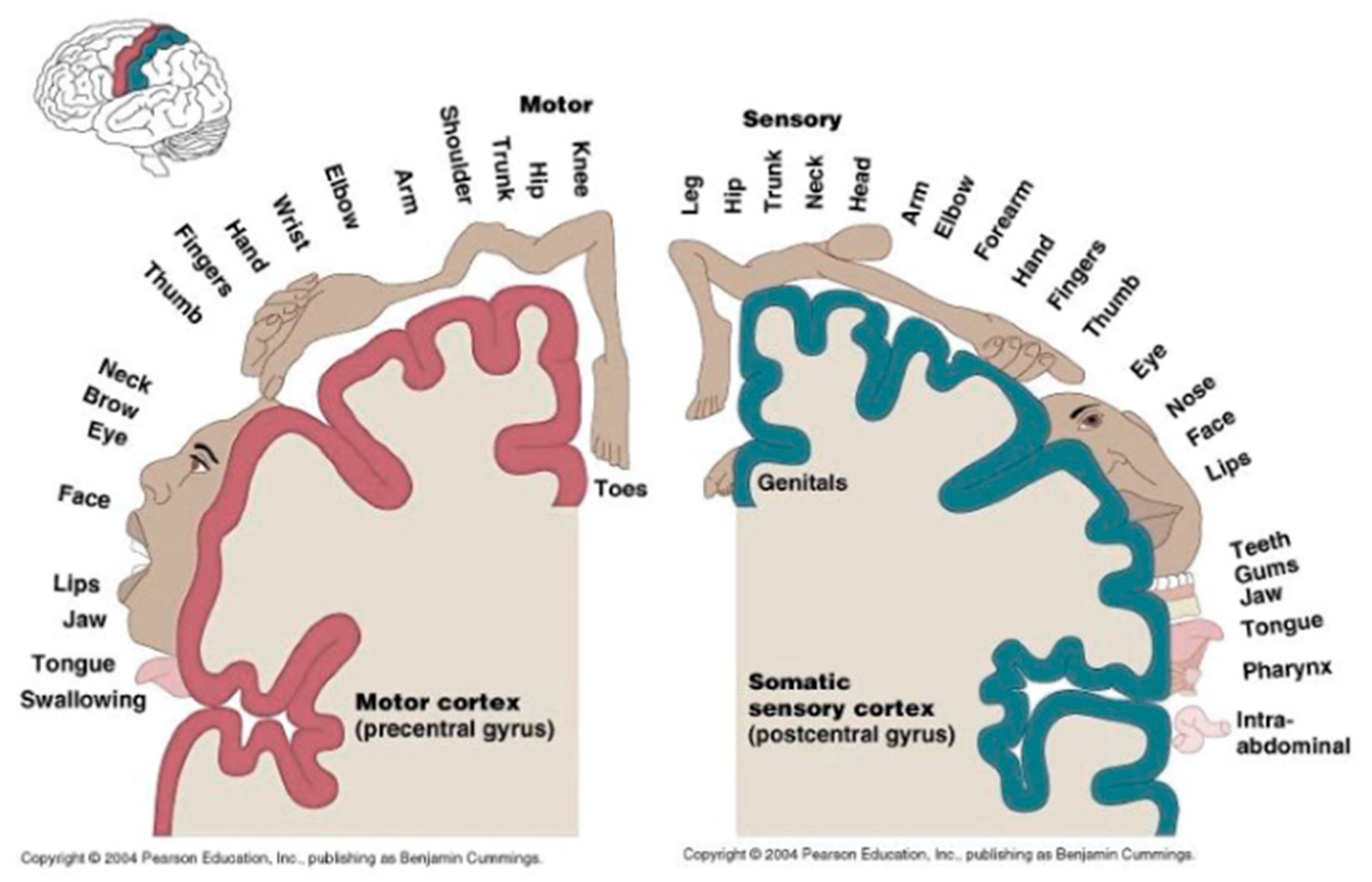

- B. Cummings, “Chapter 12: Functional Areas of the Cerebral Cortex,” Austin Peay State University [Online]. Available: http://www.apsu.edu/ [Accessed 10 January 2013].

- G. Queiros, “Computational methods for fMRI image processing and analysis,” Master’s thesis, University of Porto, 2013.

- J. R. Polimeni, B. Fischl, D. N. Greve, and L. L. Wald, “Laminar analysis of 7 T BOLD using an imposed spatial activation pattern in human V1,” Neuroimage, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 1334–1346, 2010.

- U. Hasson, Y. Nir, I. Levy, G. Fuhrmann, and R. Malach, “Intersubject synchronization of cortical activity during natural vision,” Science, vol. 303, no. 5664, pp. 1634–1640, 2004.

- D. Orenstein. (May 16, 2012) People with paralysis control robotic arms using brain-computer interface. Accessed on February 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://news.brown.edu/articles/2012/05/braingate2.

- Saini. (May 27, 2009) The brain police: judging murder with an MRI. Accessed on December 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/guilty.

- E. De Filippi, A. Escrichs, E. Camara, C. Garrido, T. Marins, M. Sanchez-Fibla, M. Gilson, and G. Deco, “Meditation-induced effects on whole-brain structural and effective connectivity,” Brain Structure and Function, vol. 227, no. 6, pp. 2087–2102, 2022.

- R. F. Afonso, I. Kraft, M. A. Aratanha, and E. H. Kozasa, “Neural correlates of meditation: a review of structural and functional MRI studies,” Frontiers in Bioscience-Scholar, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 92–115, 2020.

- B. R. Cahn and J. Polich, “Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies.” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 132, no. 2, p. 180, 2006.

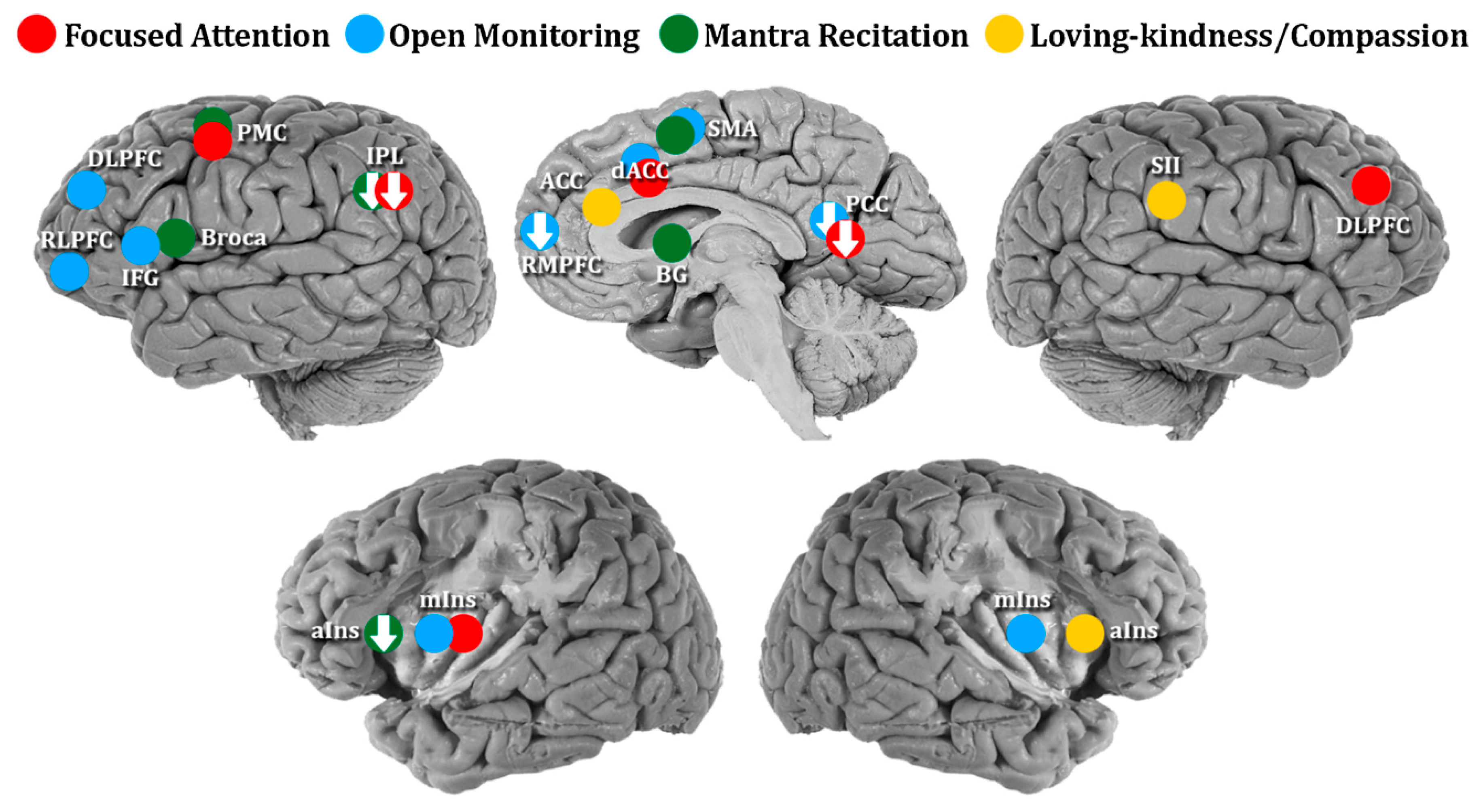

- K. C. Fox, M. L. Dixon, S. Nijeboer, M. Girn, J. L. Floman, M. Lifshitz, M. Ellamil, P. Sedlmeier, and K. Christoff, “Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 65, pp. 208–228, 2016.

- C. J. Dahl, A. Lutz, and R. J. Davidson, “Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice,” Trends in cognitive sciences, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 515–523, 2015.

- Lutz, H. A. Slagter, J. D. Dunne, and R. J. Davidson, “Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation,” Trends in cognitive sciences, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 163–169, 2008.

- Y.-Y. Tang, B. K. Holzel, and M. I. Posner, “The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 213–225, 2015.

- C. Conversano, R. Ciacchini, G. Orru`, M. Di Giuseppe, A. Gemignani, and A. Poli, “Mindfulness, compassion, and self-compassion among health care professionals: what’s new? A systematic review,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, p. 1683, 2020.

- S. Karama, M. E. Bastin, C. Murray, N. A. Royle, L. Penke, S. Munoz Maniega, A. J. Gow, J. Corley, M. Valdes Hernandez, J. D. Lewis et al., “Childhood cognitive ability accounts for associations between cognitive ability and brain cortical thickness in old age,” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 555–559, 2014.

- S. R. Cox, S. J. Ritchie, C. Fawns-Ritchie, E. M. Tucker-Drob, and I. J. Deary, “Structural brain imaging correlates of general intelligence in UK Biobank,” Intelligence, vol. 76, p. 101376, 2019.

- S. J. Ritchie, T. Booth, M. d. C. V. Hernandez, J. Corley, S. M. Maniega, A. J. Gow, N. A. Royle, A. Pattie, S. Karama, J. M. Starr et al., “Beyond a bigger brain: Multivariable structural brain imaging and intelligence,” Intelligence, vol. 51, pp. 47–56, 2015.

- K. L. Narr, R. P. Woods, P. M. Thompson, P. Szeszko, D. Robinson, T. Dimtcheva, M. Gurbani, A. W. Toga, and R. M. Bilder, “Relationships between IQ and regional cortical gray matter thickness in healthy adults,” Cerebral cortex, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 2163–2171, 2007.

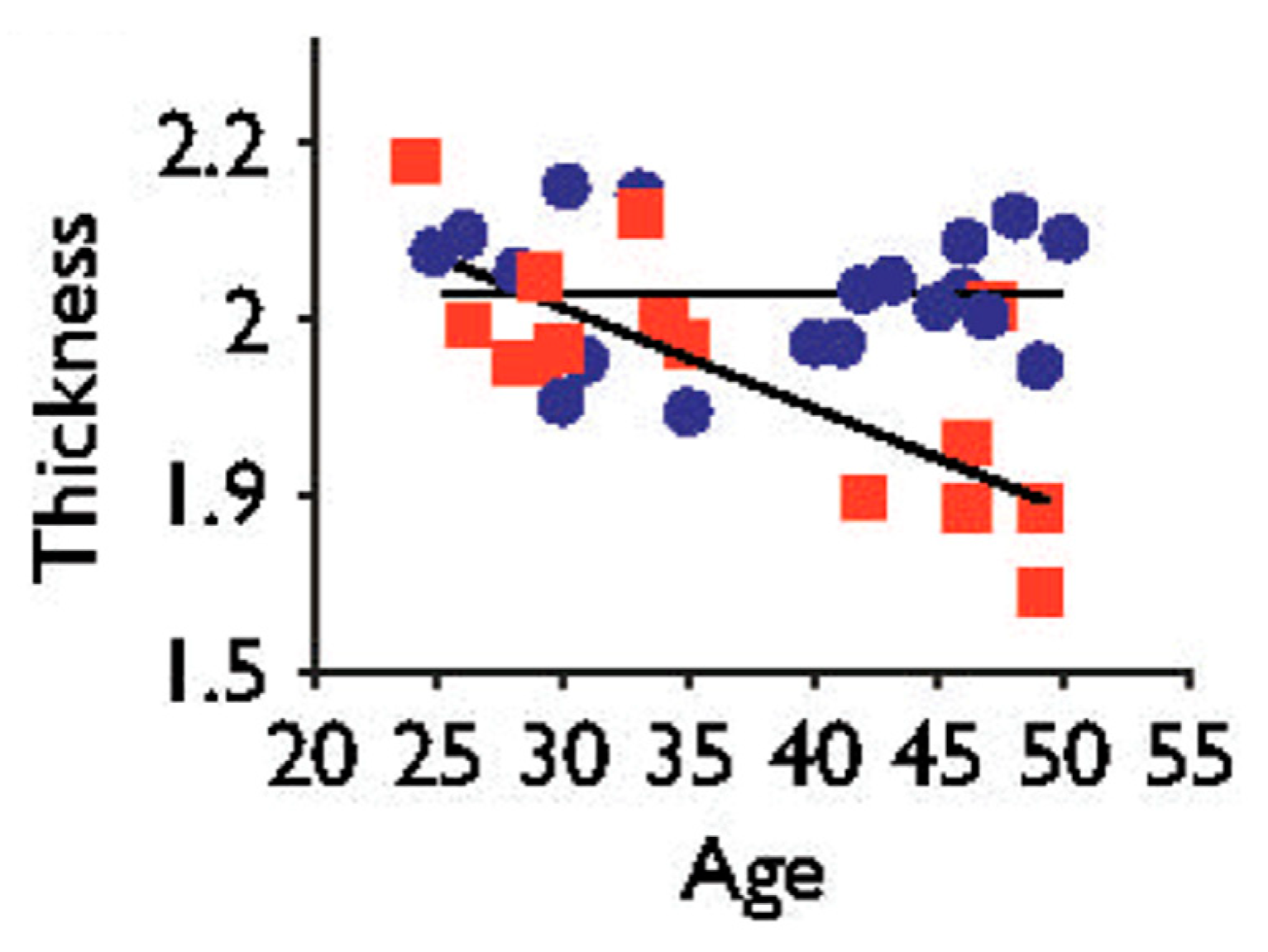

- M. Thambisetty, J. Wan, A. Carass, Y. An, J. L. Prince, and S. M. Resnick, “Longitudinal changes in cortical thickness associated with normal aging,” Neuroimage, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 1215–1223, 2010.

- S. Ramanoe l, E. Hoyau, L. Kauffmann, F. Renard, C. Pichat, N. Boudiaf, A. Krainik, A. Jaillard, and M. Baciu, “Gray matter volume and cognitive performance during normal aging. A voxel-based morphometry study,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 10, p. 235, 2018.

- S. W. Lazar, C. E. Kerr, R. H. Wasserman, J. R. Gray, D. N. Greve, M. T. Treadway, M. McGarvey, B. T. Quinn, J. A. Dusek, H. Benson et al., “Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness,” Neuroreport, vol. 16, no. 17, p. 1893, 2005.

- E. A. Zimmermann, E. Schaible, H. Bale, H. D. Barth, S. Y. Tang, P. Reichert, B. Busse, T. Alliston, J. W. Ager III, and R. O. Ritchie, “Age-related changes in the plasticity and toughness of human cortical bone at multiple length scales,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, no. 35, pp. 14416–14421, 2011.

- R. Tang, K. J. Friston, and Y.-Y. Tang, “Brief mindfulness meditation induces gray matter changes in a brain hub,” Neural plasticity, vol. 2020, pp. 8830005. 2020.

- R. Kakigi, H. Nakata, K. Inui, N. Hiroe, O. Nagata, M. Honda, S. Tanaka, N. Sadato, and M. Kawakami, “Intracerebral pain processing in a Yoga Master who claims not to feel pain during meditation,” European Journal of Pain, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 581–589, 2005.

- F. Zeidan and D. R. Vago, “Mindfulness meditation–based pain relief: a mechanistic account,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1373, no. 1, pp. 114–127, 2016.

- G. Riegner, G. Posey, V. Oliva, Y. Jung, W. Mobley, and F. Zeidan, “Disentangling self from pain: mindfulness meditation-induced pain relief is driven by thalamic-default mode network decoupling,” Pain, vol. 164, no. 2, pp. 280–291, 2023.

- D. Zhou, Y. Kang, D. Cosme, M. Jovanova, X. He, A. Mahadevan, J. Ahn, O. Stanoi, J. K. Brynildsen, N. Cooper et al., “Mindful attention promotes control of brain network dynamics for self-regulation and discontinues the past from the present,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 2, p. e2201074119, 2023.

- R. C. DeCharms, F. Maeda, G. H. Glover, D. Ludlow, J. M. Pauly, D. Soneji, J. D. Gabrieli, and S. C. Mackey, “Control over brain activation and pain learned by using real-time functional MRI,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 102, no. 51, pp. 18626–18631, 2005.

- E. J. Modestino, “Neurophenomenology of an altered state of consciousness: An fMRI case study,” Explore, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 128–135, 2016.

- E. Koechlin, G. Corrado, P. Pietrini, and J. Grafman, “Dissociating the role of the medial and lateral anterior prefrontal cortex in human planning,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 97, no. 13, pp. 7651–7656, 2000.

- C. K. Kovach, N. D. Daw, D. Rudrauf, D. Tranel, J. P. O’Doherty, and R. Adolphs, “Anterior prefrontal cortex contributes to action selection through tracking of recent reward trends,” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 32, no. 25, pp. 8434–8442, 2012.

- P. Arambula, E. Peper, M. Kawakami, and K. H. Gibney, “The physiological correlates of Kundalini Yoga meditation: a study of a yoga master,” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 26, pp. 147–153, 2001.

- G. Venkatasubramanian, P. N. Jayakumar, H. R. Nagendra, D. Nagaraja, R. Deeptha, and B. N. Gangadhar, “Investigating paranormal phenomena: Functional brain imaging of telepathy,” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 66, 2008.

- B. Anand, G. Chhina, and B. Singh, “Studies on Shri Ramanand Yogi during his stay in an air-tight box. 1961,” The Indian journal of medical research, vol. 136, no. 4, pp. 691–698, 2012.

- M. A. Wenger, B. Bagchi, and B. Anand, “Experiments in India on “voluntary” control of the heart and pulse,” Circulation, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1319–1325, 1961.

- M. A. Wenger and B. Bagchi, “Studies of autonomic functions in practitioners of yoga in India,” Behavioral Science, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 312–323, 1961.

- B. Anand, G. Chhina, and B. Singh, “Some aspects of electroencephalographic studies in yogis,” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 452–456, 1961.

- K. B. Baerentsen, “Patanjali and neuroscientific research on meditation,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 6, p. 915, 2015.

- S. V. Bharati, Yoga sutras of Patanjali. Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 2002.

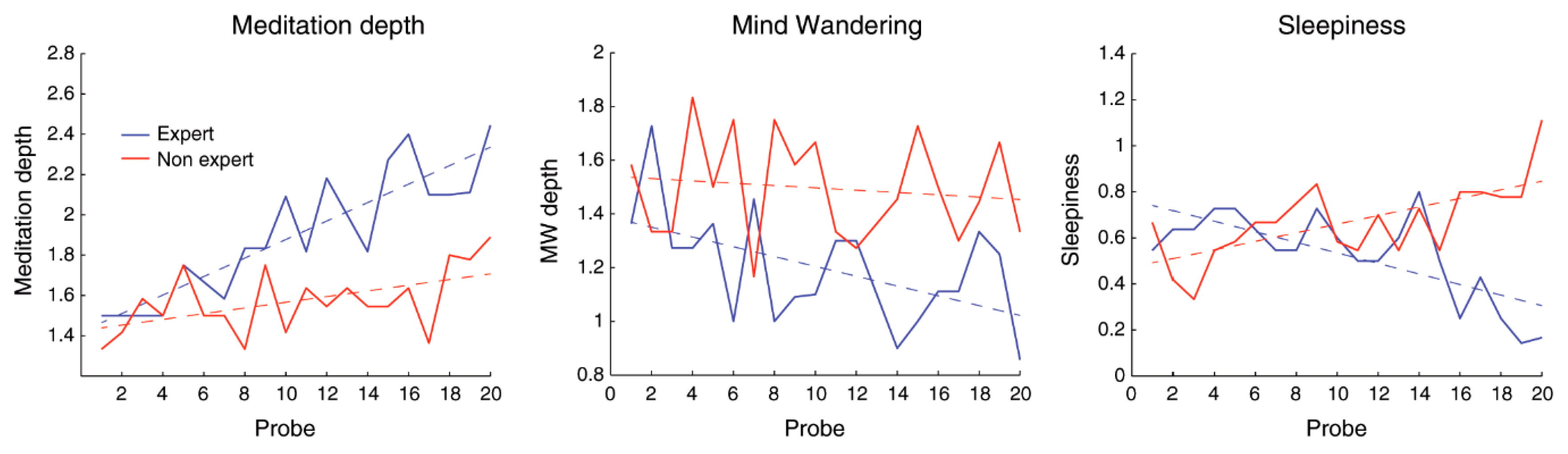

- T. Brandmeyer and A. Delorme, “Reduced mind wandering in experienced meditators and associated EEG correlates,” Experimental brain research, vol. 236, no. 9, pp. 2519–2528, 2018.

- K. Dewhurst and A. Beard, “Sudden religious conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 117, no. 540, pp. 497–507, 1970.

- R. V. Vishnubhotla, R. Radhakrishnan, K. Kveraga, R. Deardorff, C. Ram, D. Pawale, Y.-C. Wu, J. Renschler, B. Subramaniam, and S. Sadhasivam, “Advanced meditation alters resting-state brain network connectivity correlating with improved mindfulness,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, pp. 745344. 2021.

- Doll, B. K. Holzel, C. C. Boucard, A. M. Wohlschlager, and C. Sorg, “Mindfulness is associated with intrinsic functional connectivity between default mode and salience networks,” Frontiers in human neuroscience, vol. 9, p. 461, 2015.

- S. Ganesan, E. Beyer, B. Moffat, N. T. Van Dam, V. Lorenzetti, and A. Zalesky, “Focused attention meditation in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional functional MRI studies,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 141, p. 104846, 2022.

- Barros-Loscertales, S. E. Hernandez, Y. Xiao, J. L. Gonzalez-Mora, and K. Rubia, “Resting state functional connectivity associated with Sahaja Yoga Meditation,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 15, p. 614882, 2021.

- S. E. Hernandez, J. Suero, A. Barros, J. L. Gonzalez-Mora, and K. Rubia, “Increased grey matter associated with long-term Sahaja Yoga meditation: a voxel-based morphometry study,” PloS one, vol. 11, no. 3, p. e0150757, 2016.

- T. Ramsay, L. Manderson, and W. Smith, “Changing a mountain into a mustard seed: Spiritual practices and responses to disaster among New York Brahma Kumaris,” Journal of Contemporary Religion, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 89–105, 2010.

- K. Sharma, S. Chandra, and A. K. Dubey, “Exploration of lower frequency EEG dynamics and cortical alpha asymmetry in long-term Rajyoga meditators,” International journal of yoga, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 30, 2018.

- M. Babu, R. Kadavigere, P. Koteshwara, B. Sathian, and K. S. Rai, “Rajyoga meditation induces grey matter volume changes in regions that process reward and happiness,” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- M. C. Mahone, F. Travis, R. Gevirtz, and D. Hubbard, “fMRI during Transcendental Meditation practice,” Brain and Cognition, vol. 123, pp. 30–33, 2018.

- Manna, A. Raffone, M. G. Perrucci, D. Nardo, A. Ferretti, A. Tartaro, A. Londei, C. Del Gratta, M. O. Belardinelli, and G. L. Romani, “Neural correlates of focused attention and cognitive monitoring in meditation,” Brain Research Bulletin, vol. 82, no. 1-2, pp. 46–56, 2010.

- J. A. Grant, J. Courtemanche, and P. Rainville, “A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators,” Pain, vol. 152, no. 1, pp. 150–156, 2011.

- S. Kwak, S.-Y. Kim, D. Bae, W.-J. Hwang, K. I. K. Cho, K.-O. Lim, H.-Y. Park, T. Y. Lee, and J. S. Kwon, “Enhanced attentional network by short-term intensive meditation,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 10, p. 3073, 2020.

- M. Izzetoglu, P. A. Shewokis, K. Tsai, P. Dantoin, K. Sparango, and K. Min, “Short-term effects of meditation on sustained attention as measured by fNIRS,” Brain Sciences, vol. 10, no. 9, p. 608, 2020.

- S. Chamu, “Sri Ranga Mahaguru” (in Kannada language). Mysore, India: Ashtanga Yoga Vijnana Mandiram, 1972.

- S. Chamu, “Sri Ranga Sadguru: A Short Biography of a Yogi”. Mysore, India: Ashtanga Yoga Vijnana Mandiram, 1992.

- N. Pradhan and D. Narayana Dutt, “An analysis of dimensional complexity of brain electrical activity during meditation,” in Proceedings of the First Regional Conference of IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society and 14th Conference of the Biomedical Engineering Society of India. New Delhi, India, pp. 92-93, 1995.

- B. R. Cahn, M. S. Goodman, C. T. Peterson, R. Maturi, and P. J. Mills, “Yoga, meditation and mind-body health: increased BDNF, cortisol awakening response, and altered inflammatory marker expression after a 3-month yoga and meditation retreat,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 11, p. 315, 2017.

- C. Braboszcz, B. R. Cahn, B. Balakrishnan, R. K. Maturi, R. Grandchamp, and A. Delorme, “Plasticity of visual attention in Isha yoga meditation practitioners before and after a 3-month retreat,” Frontiers in psychology, vol. 4, p. 914, 2013.

- M. Bhatia, A. Kumar, N. Kumar, R. Pandey, and V. Kochupillai, “Electrophysiologic evaluation of Sudarshan Kriya: an EEG, BAER, P300 study.” Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 157–163, 2003.

- E. M. Seppala, J. B. Nitschke, D. L. Tudorascu, A. Hayes, M. R. Goldstein, D. T. Nguyen, D. Perlman, and R. J. Davidson, “Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in US Military veterans: A randomized controlled longitudinal study,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 397–405, 2014.

- P. N. V. Murthy, B. Gangadhar, N. Janakiramaiah, and D. Subbakrishna, “Normalization of P300 amplitude following treatment in dysthymia,” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 740–743, 1997.

- P. N. V. Murthy, N. Janakiramaiah, B. Gangadhar, and D. Subbakrishna, “P300 amplitude and antidepressant response to Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY),” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 45–48, 1998.

- S. Chandra, A. K. Jaiswal, R. Singh, D. Jha, and A. P. Mittal, “Mental stress: Neurophysiology and its regulation by Sudarshan Kriya Yoga,” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 67, 2017.

- S. Telles, N. Singh, K. Naveen, S. Deepeshwar, S. Pailoor, N. Manjunath, L. George, R. Dawn, and A. Balkrishna, “A fMRI study of stages of yoga meditation described in traditional texts,” Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 185, 2015.

- S. Pal, N. Kala, S. Telles, and A. Balkrishna, “Neurophysiological changes determined by the EEG with yoga breathing practices: A mini review,” Psychology, pp. 845–847, 2018.

- R. J. Davidson, J. Kabat-Zinn, J. Schumacher, M. Rosenkranz, D. Muller, S. F. Santorelli, F. Urbanowski, A. Harrington, K. Bonus, and J. F. Sheridan, “Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation,” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 564–570, 2003.

- Schimmel, Mystical dimensions of Islam. University of North Carolina Press, 1975.

- S. S. Yoga. (October 08, 2021) Sounding off on spirituality: Exploring chanting in different cultures. Accessed on January 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.soundoflife.com/blogs/places/sounding-off-on-spirituality-exploring-chanting-different-cultures.

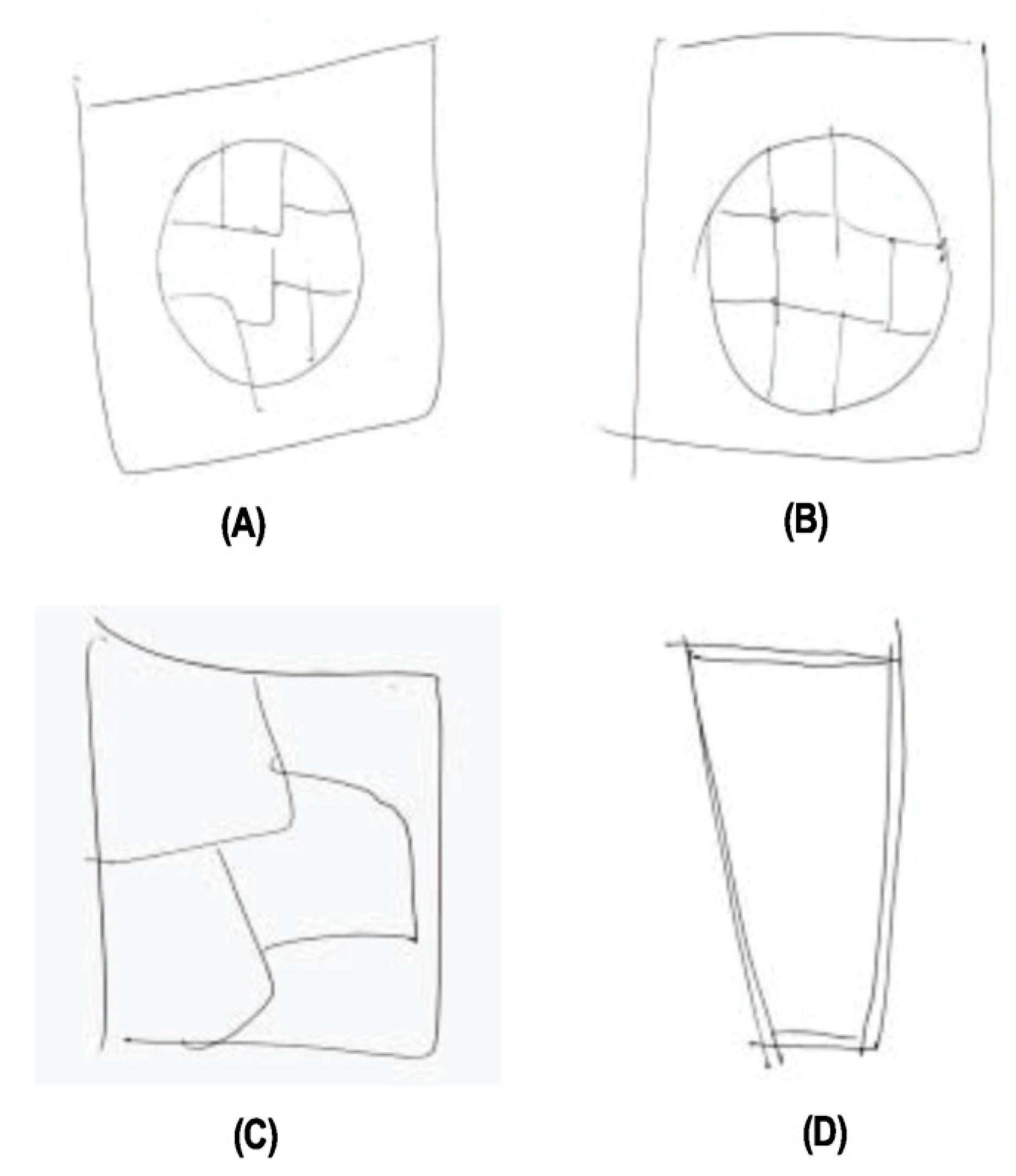

- G. P. Kalamangalam and T. M. Ellmore, “Focal cortical thickness correlates of exceptional memory training in Vedic priests,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 8, p. 833, 2014.

- Berkovich-Ohana, M. Wilf, R. Kahana, A. Arieli, and R. Malach, “Repetitive speech elicits widespread deactivation in the human cortex: the “Mantra” effect?” Brain and Behavior, vol. 5, no. 7, p. e00346, 2015.

- G. Kalyani, G. Venkatasubramanian, R. Arasappa, N. P. Rao, S. V. Kalmady, R. V. Behere, H. Rao, M. K. Vasudev, and B. N. Gangadhar, “Neurohemodynamic correlates of ‘OM’ chanting: a pilot functional magnetic resonance imaging study,” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 3, 2011.

- J. D. Bremner, N. Z. Gurel, M. T. Wittbrodt, M. H. Shandhi, M. H. Rapaport, J. A. Nye, B. D. Pearce, V. Vaccarino, A. J. Shah, J. Park et al., “Application of noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation to stress-related psychiatric disorders,” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 119, 2020.

- N. P. Rao, G. Deshpande, K. B. Gangadhar, R. Arasappa, S. Varambally, G. Venkatasubramanian, and B. N. Ganagadhar, “Directional brain networks underlying OM chanting,” Asian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 37, pp. 20–25, 2018.

- Price and R. Eccles, “Nasal airflow and brain activity: is there a link?” The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, vol. 130, no. 9, pp. 794–799, 2016.

- S. Telles, P. Raghuraj, S. Maharana, and H. Nagendra, “Immediate effect of three yoga breathing techniques on performance on a letter-cancellation task,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, vol. 104, no. 3 suppl, pp. 1289–1296, 2007.

- M. Joshi and S. Telles, “Short communication immediate effects of right and left nostril breathing on verbal and spatial scores,” Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 197–200, 2008.

- S. Telles, M. Joshi, and P. Somvanshi, “Yoga breathing through a particular nostril is associated with contralateral event-related potential changes,” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 102, 2012.

- D. Werntz, R. Bickford, and D. Shannahoff-Khalsa, “Selective hemispheric stimulation by unilateral forced nostril breathing.” Human Neurobiology, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 165–171, 1987.

- D. S. Shannahoff-Khalsa, M. R. Boyle, and M. E. Buebel, “The effects of unilateral forced nostril breathing on cognition,” International Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 57, no. 3-4, pp. 239–249, 1991.

- K. Singh, H. Bhargav, and T. Srinivasan, “Effect of uninostril yoga breathing on brain hemodynamics: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study,” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 12, 2016.

- Sayadmansour, “Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and religion,” Iranian Journal of Neurology, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 52, 2014.

- U. Schjoedt, “The religious brain: A general introduction to the experimental neuroscience of religion,” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 310–339, 2009.

- D. Kapogiannis, G. Deshpande, F. Krueger, M. P. Thornburg, and J. H. Graf- man, “Brain networks shaping religious belief,” Brain Connectivity, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 70–79, 2014.

- U. Schjødt, H. Stødkilde-Jørgensen, A. W. Geertz, and A. Roepstorff, “Rewarding prayers,” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 443, no. 3, pp. 165–168, 2008.

- P. McGowan, Amanda L, Z. M. Boyd, Y. Kang, L. Bennett, P. Mucha, K. Ochsner, D. S. Bassett, E. B. Falk, and D. M. Lydon-Staley, “Network analysis of within-person temporal associations among physical activity, sleep, and wellbeing in situ,” Apr 2022. [Online]. Available: psyarxiv.com/q4jn3.

- S. J. Schoenthaler, K. Blum, E. R. Braverman, J. Giordano, B. Thompson, M. Oscar-Berman, R. D. Badgaiyan, M. A. Madigan, K. Dushaj, M. Li et al., “NIDA-Drug Addiction Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) relapse as a function of spirituality/religiosity,” Journal of Reward Deficiency Syndrome, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 36, 2015.

- M. Carabotti, A. Scirocco, M. A. Maselli, and C. Severi, “The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems,” Annals of Gastroenterology, vol. 28, no. 2, p. 203, 2015.

- S. H. Rhee, C. Pothoulakis, and E. A. Mayer, “Principles and clinical implications of the brain–gut–enteric microbiota axis,” Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 306–314, 2009.

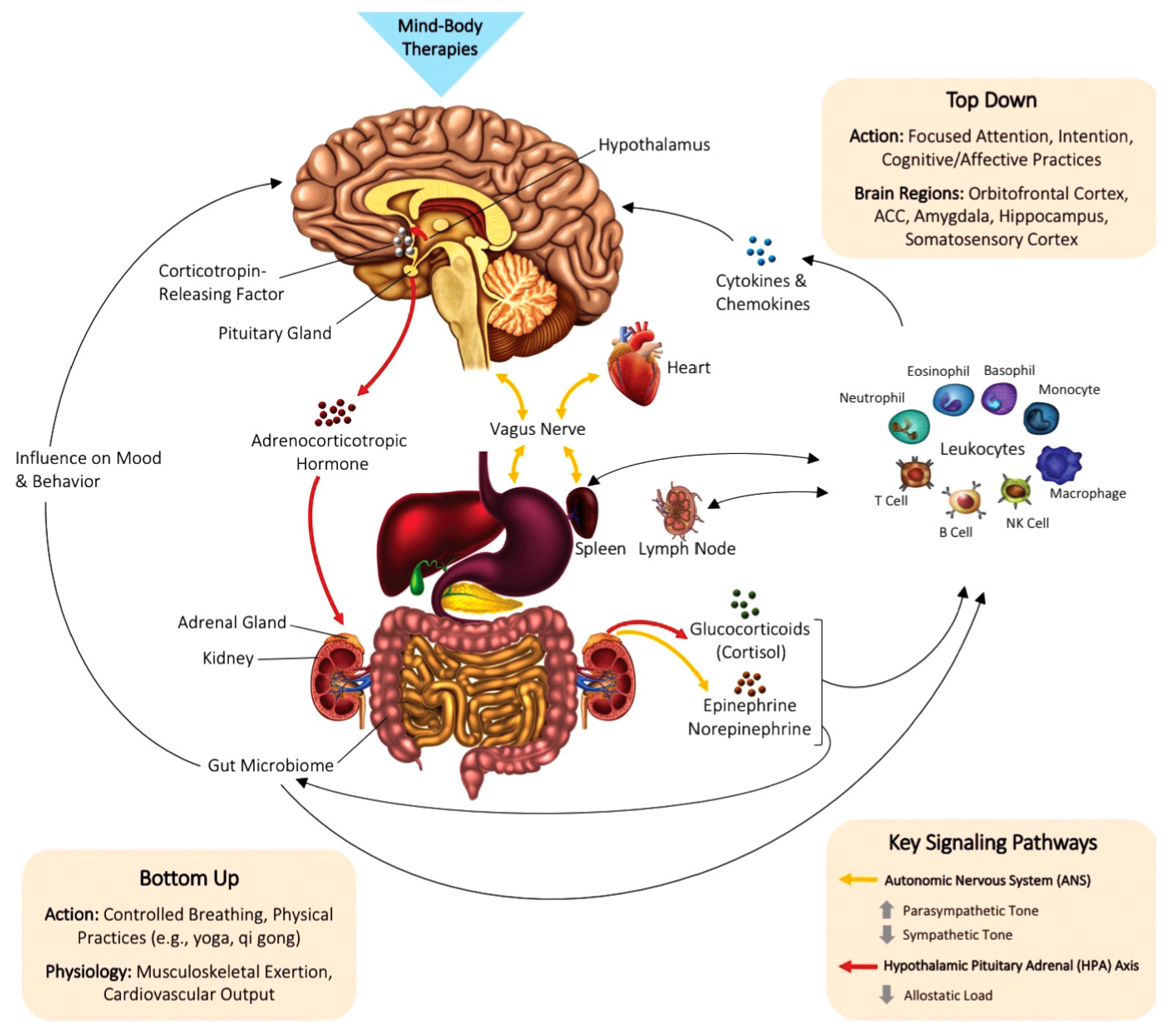

- D. Muehsam, S. Lutgendorf, P. J. Mills, B. Rickhi, G. Chevalier, N. Bat, D. Chopra, and B. Gurfein, “The embodied mind: a review on functional genomic and neurological correlates of mind-body therapies,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 73, pp. 165–181, 2017.

- Bechara, D. Tranel, H. Damasio, and A. R. Damasio, “Failure to respond autonomically to anticipated future outcomes following damage to prefrontal cortex,” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 215–225, 1996.

- Y. M. Ulrich-Lai, S. Fulton, M. Wilson, G. Petrovich, and L. Rinaman, “Stress exposure, food intake and emotional state,” Stress, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 381–399, 2015.

- M. Ravnik-Glavac, S. Hrasovec, J. Bon, J. Dreu, and D. Glavac, “Genome-wide expression changes in a higher state of consciousness,” Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1322–1344, 2012.

- S. Venditti, L. Verdone, A. Reale, V. Vetriani, M. Caserta, and M. Zampieri, “Molecules of silence: Effects of meditation on gene expression and epigenetics,” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, p. 1767, 2020.

- H. Niles, D. H. Mehta, A. A. Corrigan, M. K. Bhasin, and J. W. Denninger, “Functional genomics in the study of mind-body therapies,” Ochsner Journal, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 681–695, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).