Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design of the Low-Cost Data Logger

3.2. Sensor Calibration Experiments

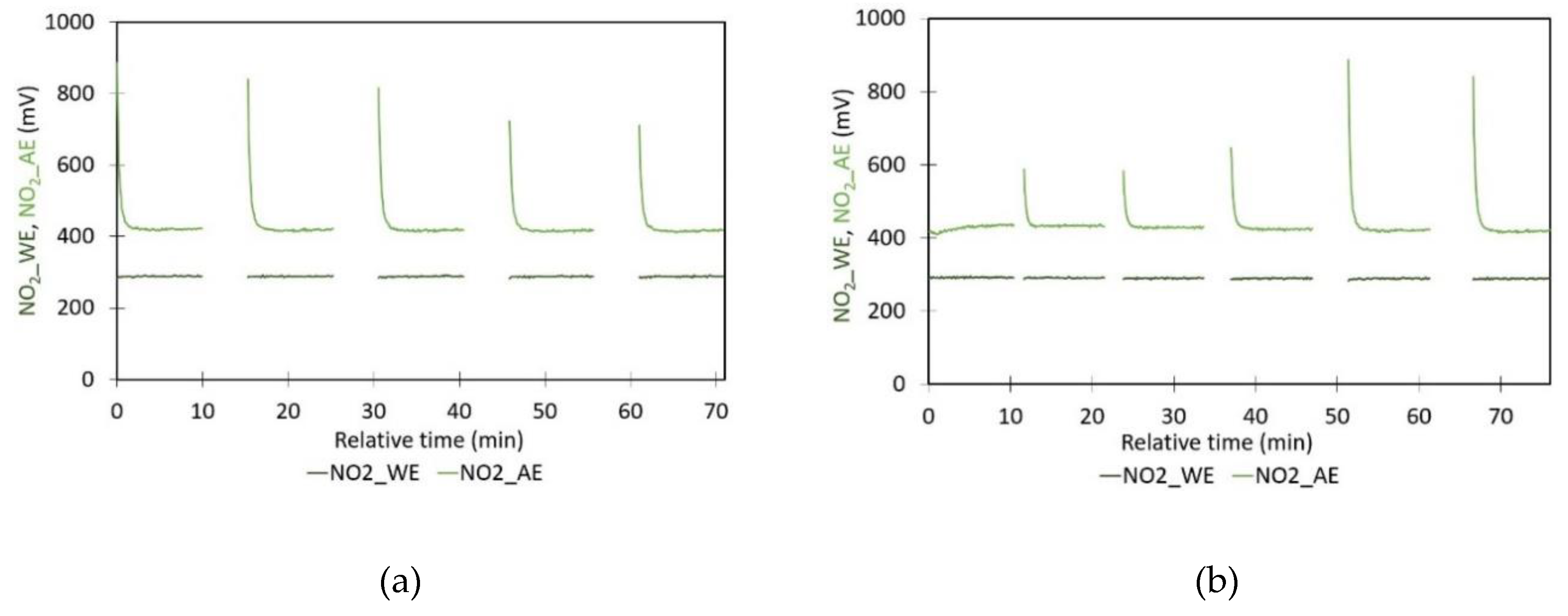

- Stability of the sensor signal during repeated on/off cycles of the system: To evaluate the stability and repeatability of the sensor signal under cyclic operational conditions, measurements were conducted in a closed box, where the system was repeatedly switched on and off. Two tests were performed, each with a 10-minute turn-on period. In the first test, the switch-off intervals were fixed at 5 minutes, whereas in the second test, the switch-off period was gradually increased from 1 to 5 minutes. Each cycle was repeated five times. For every cycle, the average and standard deviation of the signal during the final minute were calculated and compared across cycles.

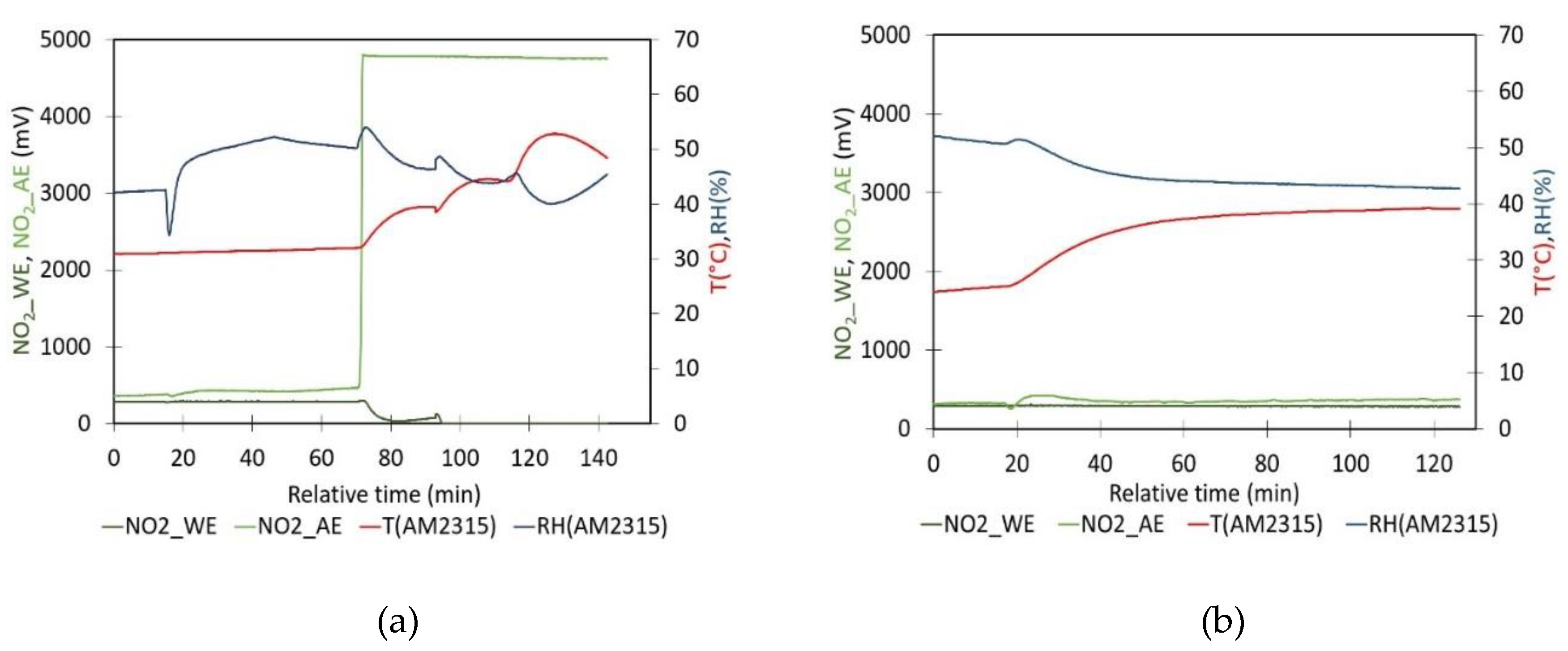

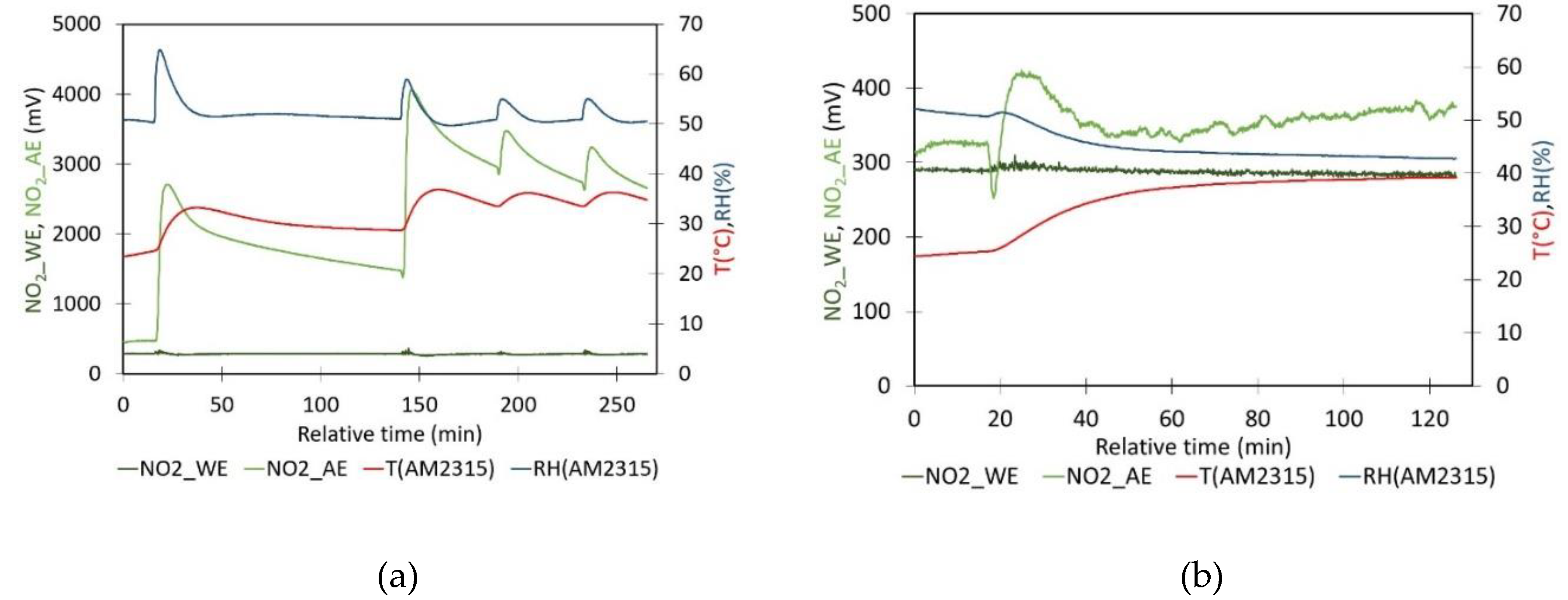

- Sensor shocks caused by temperature: The sensor was subjected to temperature shocks, with sudden temperature increases in the calibration box achieved through two methods: 1) an internal heating element (Mica Heating Pad, 80 W, 230 V AC, RS PRO) controlled externally via a digital regulator (Digital LED Thermostat Temperature Controller with Sensor Probe, MH1210A Mini, 12 VDC, Amazon), and 2) an external hair dryer directed towards the lid of the calibration box.

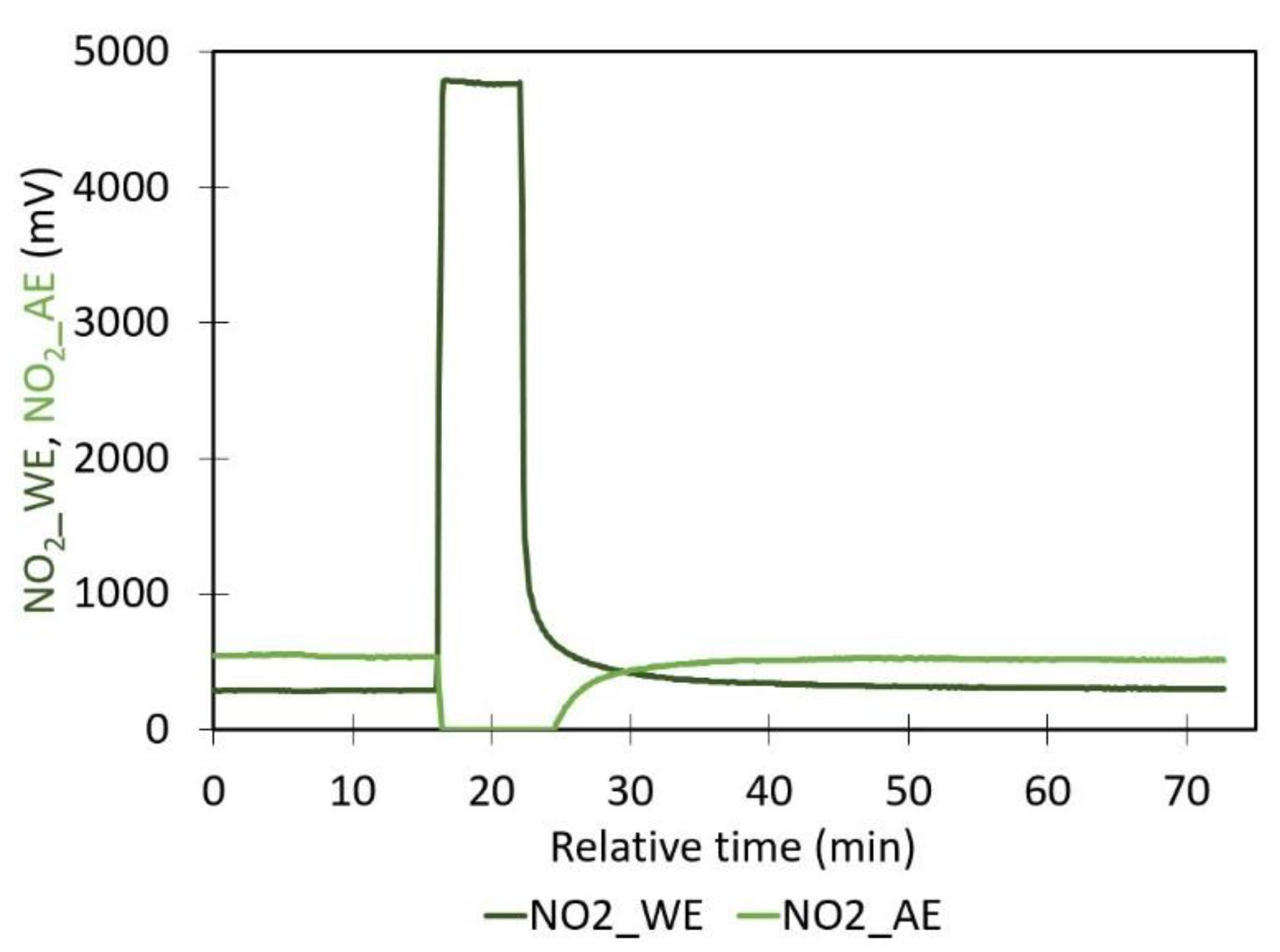

- Sensor shocks caused by concentrations: During the experiment, excess NO₂ gas was injected into the calibration box through a valve mounted on the lid of the calibration box.

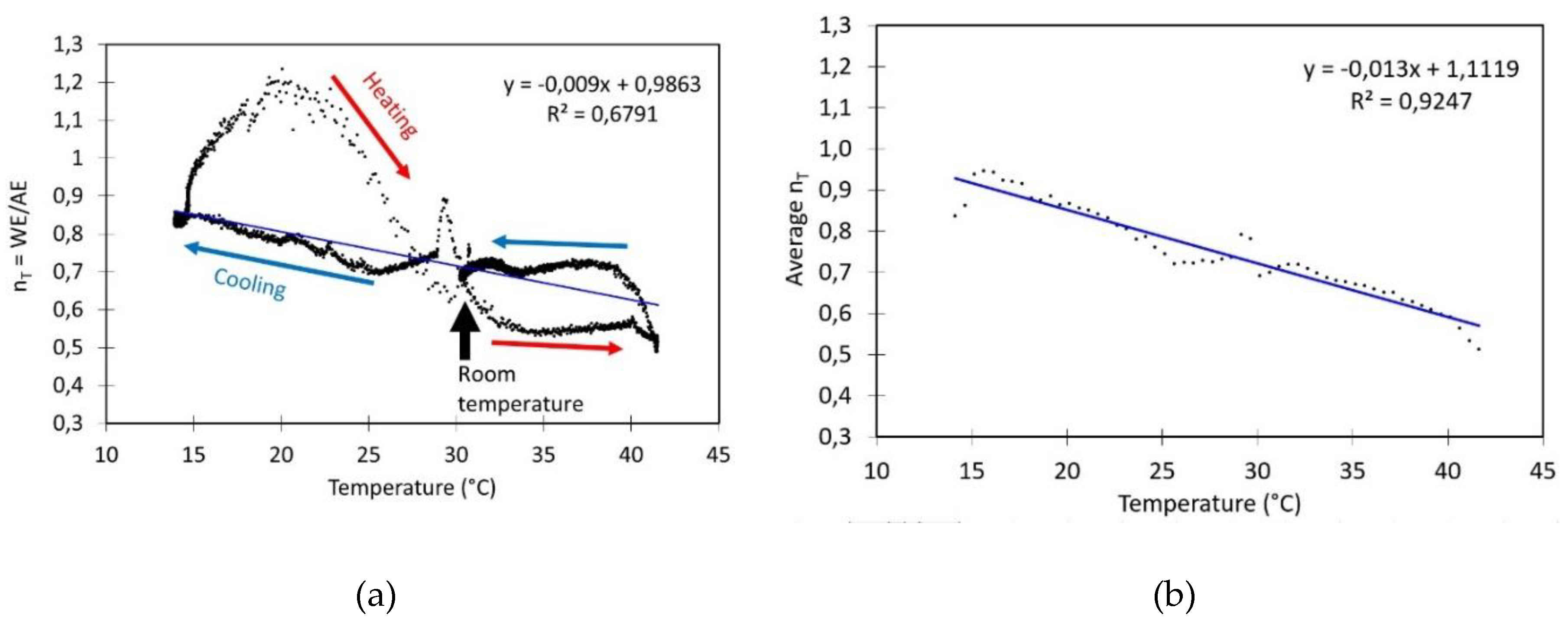

- Evaluation of the impact of T on sensor signal: The impact of temperature on the NO2 sensor calibration has been assessed by analyzing the sensors in zero air. Zero air was generated by pumping the air from the sealed box through a gas wash bottle containing a saturated Ca(OH)₂ solution. This setup is followed by a second bottle designed to capture any small droplets and a tube filled with silica gel to maintain a constant relative humidity within the box. To lower the internal temperature below ambient conditions, cooling packs were applied to the exterior walls of the calibration box. The box and the cooling packs are insulated with bubble wrap. After the temperature stabilizes at approximately 14°C, the cooling packs are removed, allowing the system to gradually return to ambient temperature. Subsequently, a hair dryer is used to externally heat the calibration box lid until the temperature reaches 42°C. The system was then left to cool freely back to ambient temperature. Throughout the experiment, there was no control over relative humidity (RH) within the box to keep it constant. As a result, RH naturally increased during cooling and decreased during heating to some extent. This setup enabled the determination of the factor nT as a function of temperature.

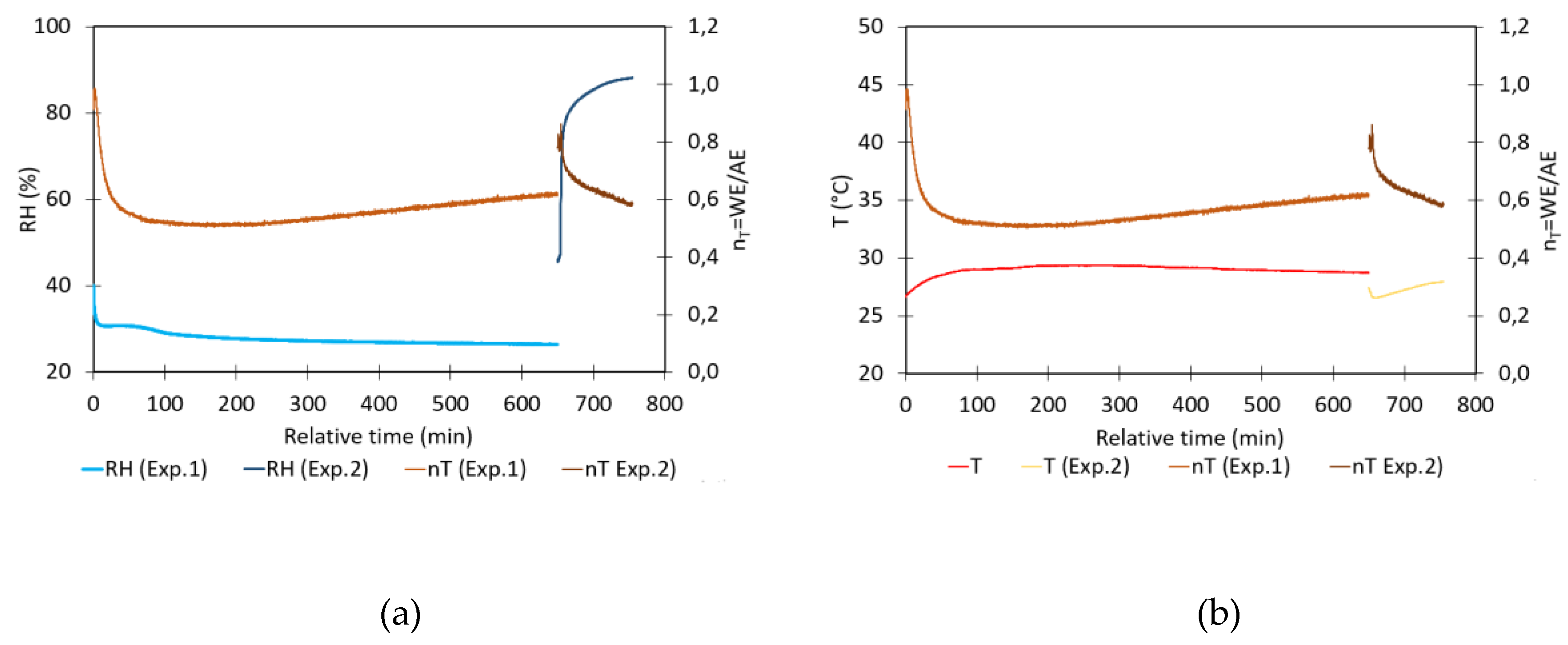

- Evaluation of the impact of RH on sensor signal: The impact of relative humidity on the NO2 sensor signals is analyzed by measuring WE and AE signals over time in clean ambient air at room conditions (approximately 29°C and 30% RH). The experiment was conducted in laboratory ambient air conditions, as these conditions yield, WE_NO2 and AE_NO2 values that are comparable to those obtained when zero air is generated. To adjust the RH, the lid of the box was opened and a Petri dish containing 200 mL of a glycerine solution was introduced into the calibration box. The large-sized Petri dish with a diameter of 15 cm provides a large contact area between the solution and the air enclosed in the container. A fan is used to homogenize the air inside the box, ensuring an even distribution of humidity. During the experiment, the RH inside the closed box gradually adjusts towards the new equilibrium. It is observed that the introduction of the Petri dish caused a sudden temperature drop of about 2°C in all experiments. The setup enabled the determination of the factor nT as a function of relative humidity with minor temperature changes.

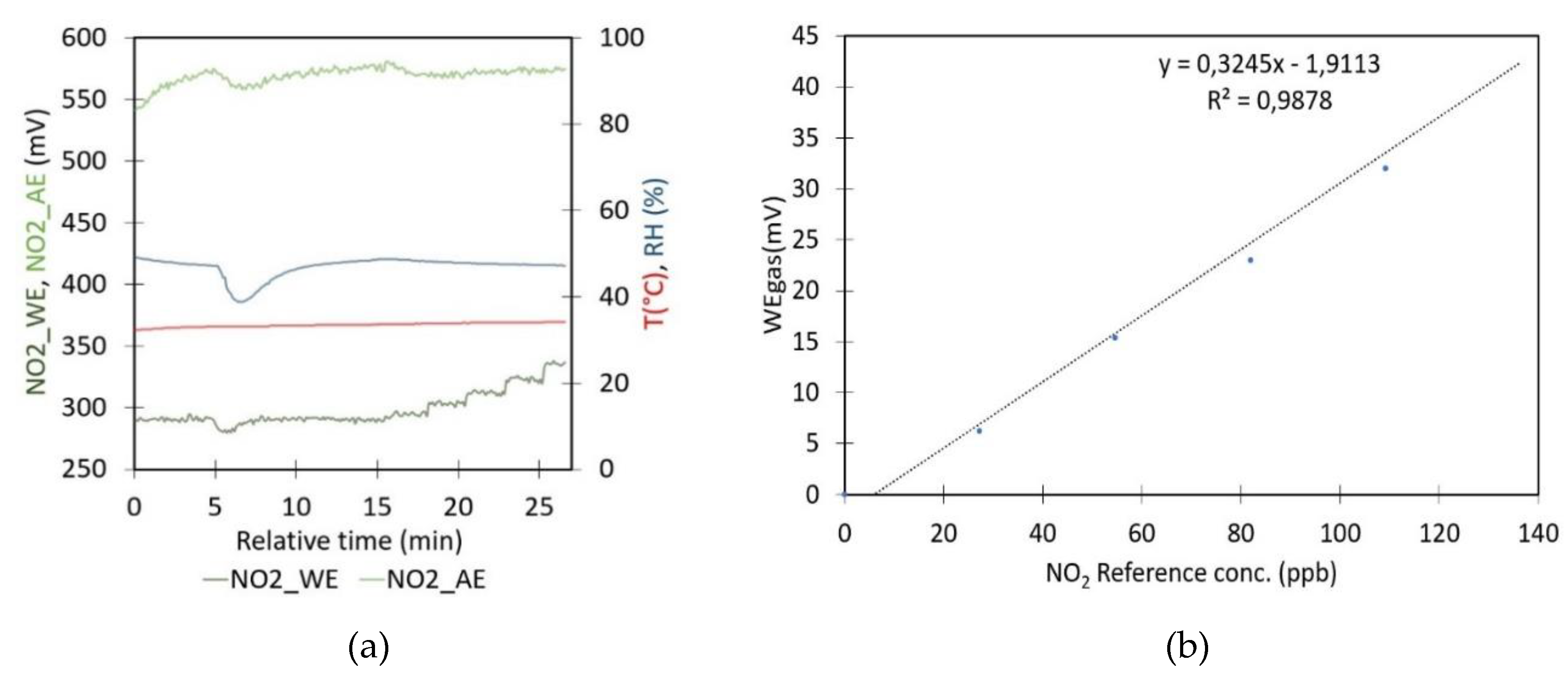

- Sensor response to the target analyte: The effect of the NO2 concentration on the gas sensor has been evaluated by introducing known amounts of NO2 gas inside the closed plastic box containing the NO2 gas sensor. Before the calibration test, the air is first purified using the same method described in the previous experiment. The cleaned air is used to determine WE and AE in zero air. Subsequently, controlled amounts of NO2 are generated as previously stated. The pure NO2 gas, held within a syringe, is first diluted by introducing the gas into a second plastic box for dilution (2 mL in a box of 6.1655 L). After approximately 20 minutes, a sequence of gas volumes (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 mL) is taken from the dilution box and introduced into the calibration box. Each injection results in a calibration point where sensor signal WEgas and corresponding pollutant concentration is known. The sensor’s sensitivity is determined by performing a linear regression on these data points. The refined quantification method was assessed by processing conditions with known NO2 concentrations at different temperatures.

4. Discussion

4.1. Repeated On/Off Cycles of the System

4.2. Impact of Temperature Shocks on the Sensor

4.3. Concentration Shocks

4.4. Impact of Temperature on nT

4.5. Impact of Relative Humidity on nT

4.6. Impact of NO2 Gas on Sensor Signal

4.7. Repeatability of nT Assessments

- Certified values of Alphasense: According to the calibration certificate from Alphasense, the WE and AE readings in zero air at 23 ± 2 °C, 40 ± 15% RH, and 101 kPa are 289 mV and 290 mV, respectively;

- Cycle on/off experiments, Figure 1: When using the linear regression shown in Figure 5b, a temperature of 29°C should result in nT = 0.7349. The WE values obtained during the cycle on/off experiments fall within the range given in Table 3. However, the AE values in Table 1 are systematically higher than the predicted value;

- Temperature experiments, Figure 5: During this experiment, zero air has been obtained at a temperature of 31 °C and an RH of 44 %. The values of WE and AE are 288.0 mV and 385.1 mV, respectively. The value of nT derived from these data is 0.7479. However, when nT is calculated using the linear regression model illustrated in Figure 5, the resulting value is 0.7089. Additionally, the WE is close to the calibration value provided by Alphasense, while the AE value is higher than the value reported by Alphasense;

- RH experiments, Figure 6: The experiments where a Petri dish with glycerine solution has been placed inside the plastic container started with a clean ambient air measurement to determine nT. Table 3 presents the results of experiments conducted with varying glycerol solutions on different days. Additionally, the nT values were calculated using the model illustrated in Figure 5b. The resulting values were 0.7362, 0.7414, 0.7609 and 0.7492, respectively. As can be observed, the values in question exhibit a discrepancy of between 10% and 35% when compared to those presented in Table 3 (nT = WE0/AE0). Moreover, the WE0 values are near the value referenced by Alphasense, whereas the AE values exhibit a divergence from it.

- Concentration experiment, Figure 7: To evaluate the sensor’s response to increasing amounts of NO₂, zero air was initially generated by bubbling it through a Ca(OH)₂ solution. Once the zero air had been obtained and the sensor signal had stabilized, the average values of WE and AE were found to be 290 and 574 mV, respectively, at a temperature of 33°C and a relative humidity of 48%. For these values, the nT was 0.5052. However, if the linear model illustrated in Figure 5 is applied, the value would be 0.6829. Moreover, the WE value is analogous to those presented in Table 3, whereas the AE value is greater than the one referenced by Alphasense.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EPA 2017 National Emissions Inventory: January 2021 Updated Release, Technical Support Document; 2021.

- EPA EPA-456/F-99-006R. Technical Bulletin. Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), Why and How They Are Controlled. 1999.

- D. A. Georgakellos Evaluation of the Environmental Damages Caused by Nitrogen Oxides Formed in Power Plants Using Lignite as Energy Carrier. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering S 2010, 17, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Miech, J.A.; Stanton, L.; Gao, M.; Micalizzi, P.; Uebelherr, J.; Herckes, P.; Fraser, M.P. Toxics Calibration of Low-Cost NO 2 Sensors through Environmental Factor Correction. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, S.F.; Kerr, G.H.; Anenberg, S.C.; Horton, D.E. All-Cause NO 2-Attributable Mortality Burden and Associated Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the United States. Cite This: Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 2023, 10, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Qi, L.; Li, S.; Duan, X. Long-Term NO2 Exposure and Mortality: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Environmental Pollution 2024, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eum, K. Do; Honda, T.J.; Wang, B.; Kazemiparkouhi, F.; Manjourides, J.; Pun, V.C.; Pavlu, V.; Suh, H. Long-Term Nitrogen Dioxide Exposure and Cause-Specific Mortality in the U.S. Medicare Population. Environ Res 2022, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Qian, Y.; Steenland, K.; Caudle, W.M.; Liu, Y.; Sarnat, J.; Papatheodorou, S.; Shi, L. Long-Term Exposure to Nitrogen Dioxide and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarehie, B.; Ghaderpoori, M.; Jafari, A.; Karami, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Azarshab, K.; Ghaderpoury, A.; Alinejad, A.; Noorizadeh, N. Quantification of Health Effects Related to SO2 and NO2 Pollutants Using Air Quality Model. J Adv. Environ Health Res 2017, 5, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidema, C.; Schumacher, C.S.; Austin, E.; Carvlin, G.; Larson, T. V.; Spalt, E.W.; Zusman, M.; Gassett, A.J.; Seto, E.; Kaufman, J.D.; et al. Deployment, Calibration, and Cross-Validation of Low-Cost Electrochemical Sensors for Carbon Monoxide, Nitrogen Oxides, and Ozone for an Epidemiological Study. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanobetti, A.; Ryan, P.H.; Coull, B.A.; Luttmann-Gibson, H.; Datta, S.; Blossom, J.; Brokamp, C.; Lothrop, N.; Miller, R.L.; Beamer, P.I.; et al. Early-Life Exposure to Air Pollution and Childhood Asthma Cumulative Incidence in the ECHO CREW Consortium. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Mohajer, N.; Zuidema, C.; Sousan, S.; Hallett, L.; Tatum, M.; Rule, A.M.; Thomas, G.; Peters, T.M.; Koehler, K. Evaluation of Low-Cost Electro-Chemical Sensors for Environmental Monitoring of Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, and Carbon Monoxide. J Occup Environ Hyg 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, D.; Bourbeau, J.; De Hoogh, K.; Hansell, A.L. Ambient Air Pollution Exposure and Chronic Bronchitis in the Lifelines Cohort. Thorax 2021, 76, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, N.; Lai, K. Association of Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution with Emergency Visits for Respiratory Diseases in Children. iScience 2022, 25, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, M.; Skrzypek, M.; Kowalski, M.; Cyrys, J. Effect of NOx and NO2 Concentration Increase in Ambient Air to Daily Bronchitis and Asthma Exacerbation, Silesian Voivodeship in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anenberg, S.C.; Mohegh, A.; Goldberg, D.L.; Kerr, G.H.; Brauer, M.; Burkart, K.; Hystad, P.; Larkin, A.; Wozniak, S.; Lamsal, L. Long-Term Trends in Urban NO2 Concentrations and Associated Paediatric Asthma Incidence: Estimates from Global Datasets. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e49–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gent, J.F.; Holford, T.R.; Bracken, M.B.; Plano, J.M.; McKay, L.A.; Sorrentinoa, K.M.; Koutrakis, P.; Leaderer, B. Childhood Asthma and Household Exposures to Nitrogen Dioxide and Fine Particles: A Triple Crossover Randomized Intervention Trial. Pediatrics 2023, 152, S48–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauderman, W.J.; Avol, E.; Lurmann, F.; Kuenzli, N.; Gilliland, F.; Peters, J.; McConnell, R. Childhood Asthma and Exposure to Traffic and Nitrogen Dioxide. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achakulwisut, P.; Brauer, M.; Hystad, P.; Anenberg, S.C. Global, National, and Urban Burdens of Paediatric Asthma Incidence Attributable to Ambient NO 2 Pollution: Estimates from Global Datasets. Lancet Planet Health 2019, 3, e166–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standarization ISO 7996:1985 Ambient Air — Determination of the Mass Concentration of Nitrogen Oxides — Chemiluminescence Method. 1985.

- International Organization for Standarization ISO 6768:1998 Ambient Air — Determination of Mass Concentration of Nitrogen Dioxide — Modified Griess-Saltzman Method. 1998.

- Krupa, S. V.; Legge, A.H. Passive Sampling of Ambient, Gaseous Air Pollutants: An Assessment from an Ecological Perspective. Environmental Pollution 2000, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Cabañas, B.; Villanueva, F.; Gallego, M.P.; Colmenar, I.; Salgado, S. Ozone and Nitrogen Dioxide Levels Monitored in an Urban Area (Ciudad Real) in Central-Southern Spain. Water Air Soil Pollut 2010, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, V.P.; Cruz, L.P.S.; Godoi, R.H.M.; Flávia, A.; Godoi, L.; Tavares, T.M. Development and Validation of Passive Samplers for Atmospheric Monitoring of SO 2, NO 2, O 3 and H 2 S in Tropical Areas. Microchemical Journal 2010, 96, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adon, M.; Yoboué, V.; Galy-Lacaux, C.; Liousse, C.; Diop, B.; Doumbia, E.H.T.; Gardrat, E.; Ndiaye, S.A.; Jarnot, C. Measurements of NO2, SO2, NH3, HNO3 and O3 in West African Urban Environments. Atmos Environ 2016, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Saborit, J.M.; Esteve Cano, V.J. Field Comparison of Passive Samplers versus UV-Photometric Analyser to Measure Surface Ozone in a Mediterranean Area. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 2007, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, T.; Ali, Z.; Noor, N.; Sidra, S.; Nasir, Z.A.; Colbeck, I. Measurement of NO2 Indoor and Outdoor Concentrations in Selected Public Schools of Lahore Using Passive Sampler. J Anim Plant Sci 2015, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Voina, A.; Pantelimon, B.; Alecu, G. Methods for Measurement, Monitoring and Control of Nox Emissions. Incd Ecoind – International Symposium – Simi 2011 “the Environment and the Industry”, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alejo Sánchez, D. Quantification of Nitrogen Dioxide and Tropospheric Ozone and Their Human Health Risk in the Zone of Major Incidence in Santa Clara City, Cuba Daniellys Alejo Sánchez, University of Antwerp, 2012.

- Suriano, D.; Cassano, G.; Penza, M. Design and Development of a Flexible, Plug-and-Play, Cost-Effective Tool for on-Field Evaluation of Gas Sensors. J Sens 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidema, C.; Schumacher, C.S.; Austin, E.; Carvlin, G.; Larson, T. V.; Spalt, E.W.; Zusman, M.; Gassett, A.J.; Seto, E.; Kaufman, J.D.; et al. Deployment, Calibration, and Cross-Validation of Low-Cost Electrochemical Sensors for Carbon Monoxide, Nitrogen Oxides, and Ozone for an Epidemiological Study. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carotenuto, F.; Bisignano, A.; Brilli, L.; Gualtieri, G.; Giovannini, L. Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Networks for Long-Term Field Campaigns: A Review. Meteorological Applications 2023, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, T.; Jiang, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mu, J.; Yin, X.; Wu, D.; et al. Evaluation of the Performance of Low-Cost Air Quality Sensors at a High Mountain Station with Complex Meteorological Conditions. Atmosphere 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisignano, A.; Carotenuto, F.; Zaldei, A.; Giovannini, L. Field Calibration of a Low-Cost Sensors Network to Assess Traffic-Related Air Pollution along the Brenner Highway. Atmospheric Environment 2022, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitegger, P.; Schweighofer, B.; Wegleiter, H.; Knoll, M.; Lang, B.; Bergmann, A. Towards Low-Cost QEPAS Sensors for Nitrogen Dioxide Detection. Photoacoustics 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Barbiere, M.; Kotsev, A.; Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Lagler, F.; Redon, N.; Crunaire, S.; Borowiak, A. Review of the Performance of Low-Cost Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring. Atmosphere (Basel) 2019, 10, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Rivero, R.A.; Morera Hernández, L.E.; Schalm, O.; Hernández Rodríguez, E.; Alejo Sánchez, D.; Morales Pérez, M.C.; Nuñez Caraballo, V.; Jacobs, W.; Martinez Laguardia, A. A Low-Cost Calibration Method for Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Carbon Dioxide Sensors Used in Air Quality Monitoring Systems. Atmosphere (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaconstantinou, R.; Demosthenous, M.; Bezantakos, S.; Hadjigeorgiou, N.; Costi, M.; Stylianou, M.; Symeou, E.; Savvides, C.; Biskos, G. Field Evaluation of Low-Cost Electrochemical Air Quality Gas Sensors under Extreme Temperature and Relative Humidity Conditions. Atmos Meas Tech 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, N.; Dauge, F.R.; Schneider, P.; Vogt, M.; Lerner, U.; Fishbain, B.; Broday, D.; Bartonova, A. Can Commercial Low-Cost Sensor Platforms Contribute to Air Quality Monitoring and Exposure Estimates? Environ Int 2017, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Villani, M.G.; Aleixandre, M.; Bonavitacola, F. Field Calibration of a Cluster of Low-Cost Commercially Available Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring. Part B: NO, CO and CO2. Sens Actuators B Chem 2017, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Villani, M.G.; Aleixandre, M.; Bonavitacola, F. Field Calibration of a Cluster of Low-Cost Available Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring. Part A: Ozone and Nitrogen Dioxide. In Proceedings of the Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical; 2015; 215. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, N.; Piedrahita, R.; Hannigan, M. Quantification Method for Electrolytic Sensors in Long-Term Monitoring of Ambient Air Quality. Sensors (Switzerland) 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, A.; Ricardo, D.; Nuñez, O.; Carolina, G.; Castillo, S.; Laquai, B.; Vogt, U. Effect of Relative Humidity and Air Temperature on the Results Obtained from Low-Cost Gas Sensors for Ambient Air Quality Measurements. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Breitegger, P.; Schweighofer, B.; Wegleiter, H.; Knoll, M.; Lang, B.; Bergmann, A. Towards Low-Cost QEPAS Sensors for Nitrogen Dioxide Detection. Photoacoustics 2020, 18, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphasense Technical Specifications Version 1.1. NO2-A43F/NO2-A43F+ Nitrogen Dioxide Sensor.

- Drajic, D.D.; Gligoric, N.R. Reliable Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Using off-the-Shelf Sensors and Statistical Calibration. Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, D.H.; Isaacman-Vanwertz, G.; Franklin, J.P.; Wallace, L.M.M.; Kocar, B.D.; Heald, C.L.; Kroll, J.H. Calibration and Assessment of Electrochemical Air Quality Sensors by Co-Location with Regulatory-Grade Instruments. Atmos Meas Tech 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, S.; Tagle, M.; Vasquez, Y.; Donoso, R.; Lindén, J.; Hallgren, F.; Segura, M.; Oyola, P. Calibration of SO2 and NO2 Electrochemical Sensors via a Training and Testing Method in an Industrial Coastal Environment. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratingen, S. van; Vonk, J.; Blokhuis, C.; Wesseling, J.; Tielemans, E.; Weijers, E. Seasonal Influence on the Performance of Low-Cost NO2 Sensor Calibrations. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A.; Mueller, M.; Grange, S.K.; Ghermandi, G.; Hueglin, C. Performance of NO, NO2 Low Cost Sensors and Three Calibration Approaches within a Real World Application. Atmos Meas Tech 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Su, J. Simultaneous Removal of SO2 and NO by O3 Oxidation Combined with Seawater as Absorbent. Processes 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawrence, R.; Munniks, S.; Valente, J. Calibration of Electrochemical Sensors for Nitrogen Dioxide Gas Detection Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionascu, M.E.; Castell, N.; Boncalo, O.; Schneider, P.; Darie, M.; Marcu, M. Calibration of CO, NO2, and O3 Using Airify: A Low-Cost Sensor Cluster for Air Quality Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowack, P.; Konstantinovskiy, L.; Gardiner, H.; Cant, J. Towards Low-Cost and High-Performance Air Pollution Measurements Using Machine Learning Calibration Techniques. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Discussions 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alphasense APPLICATION NOTE AAN 803-05. Correcting For Background Currents In Four-Electrode Toxic Gas Sensors. 2023.

- Alphasense Alphasense Application Note AAN 803-04. 2017.

- Alphasense Application Note AAN 803-01: Correcting for Backgorund Currents in Four Electrode Toxic Gas Sensors. 2014.

- González Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O.; Alvarez Cruz, A.; Hernández Rodríguez, E.; Morales Pérez, M.C.; Alejo Sánchez, D.; Martinez Laguardia, A.; Jacobs, W.; Hernández Santana, L. Relevance and Reliability of Outdoor SO2 Monitoring in Low-Income Countries Using Low-Cost Sensors. Atmosphere (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Kairúz-Cabrera, D.; Martinez, A.; González-Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O. Low-Cost Portable System for the Estimation of Air Quality. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; 2023; Vol. 464.

- Hernández Rodríguez, E.; Martínez, A.; Schalm, O.; González Rivero, R.A.; Hernández Santana, L.; Hernández Rodríguez, E.; Martínez, A.; Schalm, O.; González Rivero, R.A.; Hernández Santana, L. Diseño de Un Sistema de Medición y Monitoreo de Variables Asociadas a Calidad Del Aire. Ingeniería Electrónica, Automática y Comunicaciones 2023, 44, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, E.; González-Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O.; Martínez, A.; Hernández, L.; Alejo-Sánchez, D.; Janssens, T.; Jacobs, W. Reliability Testing of a Low-Cost, Multi-Purpose Arduino-Based Data Logger Deployed in Several Applications Such as Outdoor Air Quality, Human Activity, Motion, and Exhaust Gas Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Hernandez, L.; Schalm, O.; Gonzalez-Rivero, R.A.; Alejo-Sanchez, D. Design of a Low-Cost System for the Measurement of Variables Associated With Air Quality. IEEE Embed Syst Lett 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, E.; González-Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O.; Martínez, A.; Hernández, L.; Alejo-Sánchez, D.; Janssens, T.; Jacobs, W. Reliability Testing of a Low-Cost, Multi-Purpose Arduino-Based Data Logger Deployed in Several Applications Such as Outdoor Air Quality, Human Activity, Motion, and Exhaust Gas Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Kairúz-Cabrera, D.; Martinez, A.; González-Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O. Low-Cost Portable System for the Estimation of Air Quality. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; 2023; Vol. 464.

- Mattson, B. Microscale Gas Chemistry. Educación Química 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdoski, M. Gas Chemistry: A Microscale Kipp Apparatus. 2011, 16, 12396–12401. [CrossRef]

- Najdoski, M.; Stojkovikj, S. Cost Effective Microscale Gas Generation Apparatus. Chemistry (Easton) 2010, 19. [Google Scholar]

- González Rivero, R.A.; Schalm, O.; Alvarez Cruz, A.; Hernández Rodríguez, E.; Morales Pérez, M.C.; Alejo Sánchez, D.; Martinez Laguardia, A.; Jacobs, W.; Hernández Santana, L. Relevance and Reliability of Outdoor SO2 Monitoring in Low-Income Countries Using Low-Cost Sensors. Atmosphere (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WE0 | The value of the working electrode in air in total absence of the target analyte (i.e., zero air) under fixed conditions, as specified in the calibration certificate provided by Alphasense, which is measured at a pressure of 101 kPa, a temperature of 23 ± 2°C, and a relative humidity of 40 ± 15%. |

| AE0 | The value of the auxiliary electrode in air in total absence of the target analyte (i.e., zero air) under fixed conditions, as specified in the calibration certificate provided by Alphasense, which is measured at a pressure of 101 kPa, a temperature of 23 ± 2°C, and a relative humidity of 40 ± 15%. |

| WEbackground | The value of the working electrode in zero air at any given moment during the monitoring campaign. This value is partially determined by the instantaneous temperature and relative humidity. These conditions may be different from the ones at which WE0 is determined. |

| AE | The measured value of the auxiliary electrode at any given moment. This value depends partly on the instantaneous temperature and relative humidity but is supposed to be independent of the concentration of the target analyte, since the electrode is not in direct contact with the sampled gas. However, the measuring conditions may deviate from those at which AE0 was originally measured. |

| WEgas | A portion of the total measured value WEtot that is linearly dependent on the concentration of the target analyte. |

| WEtot | The total measured value of the working electrode in ambient air reflects the combined contributions from the specific concentration of the target analyte at a given temperature and relative humidity WEgas, and the background interference WEbackground. |

| Cycle nr. | Experiment shown in Figure 1a | Experiment shown in Figure 1b | ||

| WE [mV] | AE [mV] | WE [mV] | AE [mV] | |

| 1 | 288.8 ± 1.2 | 420.5 ± 1.9 | 291.7 ± 1.3 | 432.6 ± 2.7 |

| 2 | 288.4 ± 1.1 | 418.0 ± 2.1 | 290.5 ± 1.0 | 433.2 ± 1.7 |

| 3 | 288.4 ± 1.2 | 417.2 ± 2.2 | 289.6 ± 1.1 | 428.5 ± 1.5 |

| 4 | 288.1 ± 1.4 | 416.2 ± 2.0 | 289.2 ± 1.3 | 423.5 ± 1.9 |

| 5 | 288.1 ± 1.3 | 415.9 ± 2.1 | 288.8 ± 1.2 | 420.3 ± 2.0 |

| 6 | - | - | 288.5 ± 1.1 | 417.8 ± 2.1 |

| Average | 288 ± 1 | 418 ± 3 | 290 ± 2 | 426 ± 6 |

| Drop [mV/h] | 0.38 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 12.7 |

| Experiment | T [°C] | RH [%] | WE [mV] | AE [mV] | nT |

| Temperature | 33 | 48 | 290 | 574 | 0.5065 |

| Cycle on/off | 29 | 50 | 288 | 418 | 0.6890 |

| RH exp. 1 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 276.5 | 472.6 | 0.5851 |

| RH exp.1 | 28.5 | 89.0 | 292.9 | 437.7 | 0.6692 |

| RH exp.2 | 27.0 | 27.1 | 281.8 | 501.78 | 0.5615 |

| RH exp.2 | 27.9 | 88.1 | 294.7 | 505.0 | 0.5835 |

| Alphasense | 23 ± 2 | 40 ± 15 | 289 | 290 | 0.9966 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).