1. Introduction

Achondroplasia is the most common form of non-lethal skeletal dysplasia worldwide, occurring in 1 in 25,000–30,000 live births [1-4]. It is characterized by disproportionate short stature, a disproportionately large head (macrocephaly), midface and skull base hypoplasia, shortening of the proximal limbs (rhizomelia), and other skeletal abnormalities, which can lead to medical, functional, and psychosocial problems throughout life [

5]. Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant inherited genetic disorder caused by autosomal dominant gain-of-function pathogenic variants in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene (FGFR3) located on the short arm of chromosome 4 [

6,

7]. Overactivation of FGFR3 affects endochondral ossification and leads to reduced bone growth [

8].

Foramen magnum stenosis (FMS) is one of the most common and serious complications of achondroplasia [

9]. Since some vital structures pass through the foramen magnum, including the medulla oblongata, radix spinalis of the nervus accessorius, and arteria vertebrales and spinales, various problems can develop depending on the severity of the stenosis [

10]. For example, compression of the medulla oblongata can lead to frequent apnea episodes, which greatly increase the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in infancy [

11,

12]. Possible signs of FMS include severe hypotonia, motor delays, feeding and sleep disturbances, and clinical features of myelopathy such as hyperreflexia [

13,

14]. In children with severe FMS, decompression surgery is the accepted treatment modality. In asymptomatic patients, there is no consistent approach to when surgery should or should not be performed [

5].

In 2021, the Achondroplasia Foramen Magnum Score (AFMS) was developed, which is a simple scoring system for categorizing the severity of FMS on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans [

15]. The objective of the score is to detect spinal cord compression in children with achondroplasia as early as possible through routine MRI screening to ensure timely intervention, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality as a consequence of FMS.

Here, changes in anatomical characteristics of cervicomedullary compression on MRI scans were analyzed in children with achondroplasia and compared with a healthy reference group. The children with achondroplasia were further subdivided into those who received decompression surgery for FMS and those who did not. The overall aim of the study was to build upon the AFMS to identify further anatomical characteristics in children with achondroplasia on MRI scans that may allow development of a standard indication for decompression surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

Data collection for this retrospective study took place between October 2020 and April 2023 at Magdeburg University Hospital, Magdeburg, Germany. Children aged ≤ 4 years with confirmed achondroplasia who had received a skull base MRI scan were identified from the Germany-wide CrescNet Registry [

16]. A reference population of children aged ≤ 4 years without achondroplasia who had received a skull base MRI scan were identified from Magdeburg University Hospital records. The reference population could have no evidence of cervicomedullary damage and no diseases that could have influenced associated anatomical structures.

MRI files were made available by the treating physicians, parents or guardians of the children for a second evaluation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the opinion of the Ethics Committee of the Magdeburg University Hospital Medical Faculty, whereby an evaluation of stored data is permitted in accordance with the doctor–patient contract, the General Contractual Conditions (AVB) for the University Hospital Magdeburg, Institution under Public Law (A.ö.R) i. d. a. F., via § 16 (5). Patient consent was waived by the ethics committee due to the anonymized nature of the data.

2.2. Analysis of Anatomical Parameters

MRI images from the achondroplasia and reference groups were analyzed using Dornheim Segmenter software (Dornheim Medical Images GmbH) [

17], which allowed calculation of areas, volumes, lengths, and angles within the images. Only preoperative MRI scans were included in the study; if multiple scans were available, only the first MRI scan of each child was used.

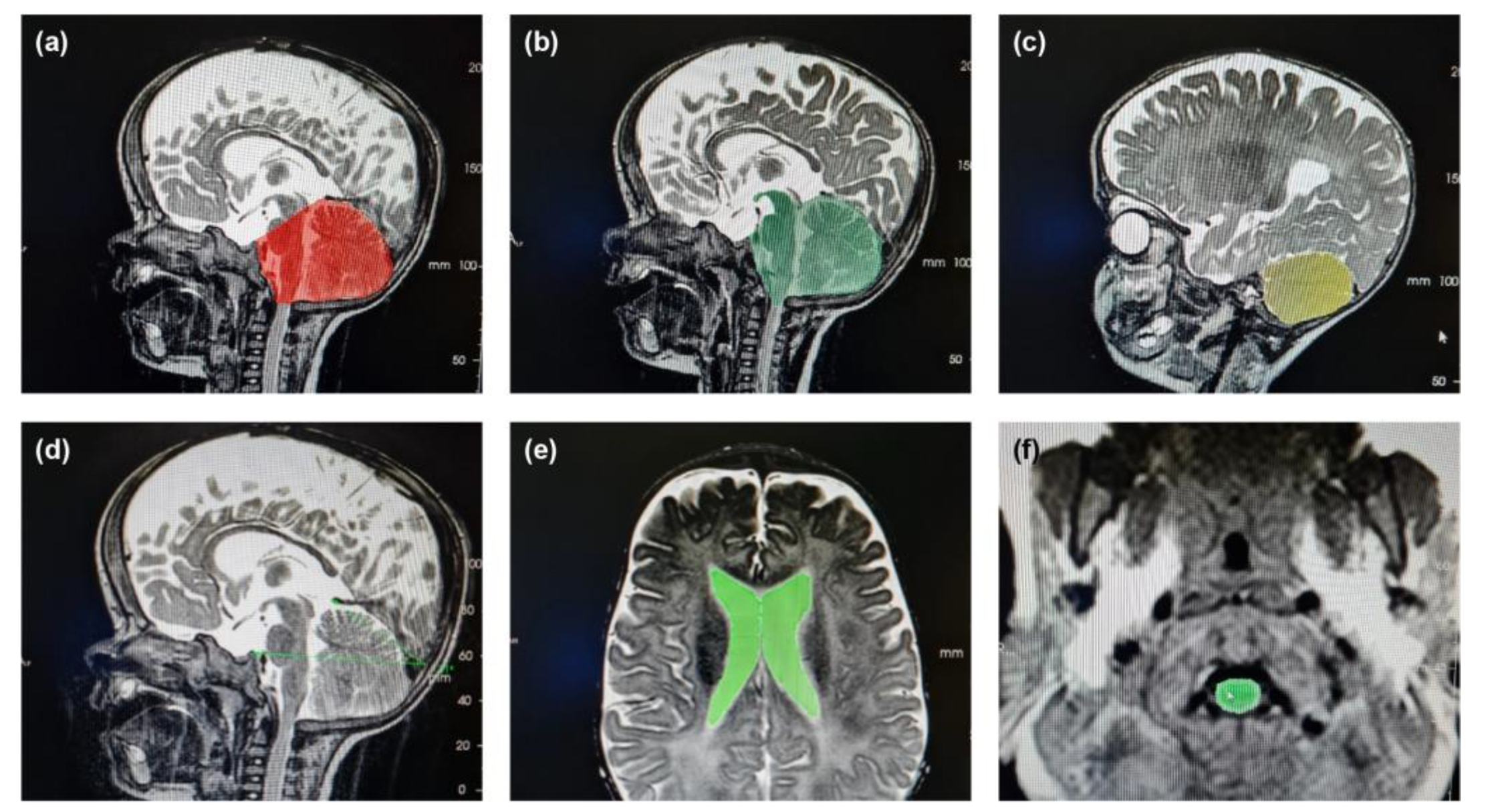

The following 12 parameters were measured using T1- and T2-weighted images in sagittal and transversal planes: diameter of the foramen magnum (T1 sagittal); area of the foramen magnum; area of the myelon (T1 transversal); length of the clivus (from the dorsum sellae to the end of the clivus); tentorium angle (the angle between the highest point of the tentorium, the protuberantia occipitalis interna and the dorsum sellae in the mid-sagittal plane); occipital angle; volume of the posterior fossa; proportion of brainstem volume outside the posterior fossa; volume of the cerebellum (T2 sagittal); volume of the supratentorial ventricular system (including the third ventricle as well as the lateral ventricles); volume of the intracranial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) system (T2 transversal); and volume of the fourth ventricle (T2 sagittal).

Before each measurement, the selected structure and the quality of the MRI image was reviewed; images of insufficient quality and structures that were incomplete were excluded. The brightness and contrast of the image was optimized to better distinguish the structures to be measured and enable more accurate measurement by the software. Each measurement was conducted in duplicate per MRI scan to compensate for any measurement errors.

2.3. Calculation of AFMS

The AFMS was calculated according to the method described previously [

15]. Briefly, sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI images from the achondroplasia group were scored from 0 (no evidence of FMS) to 4 (severe FMS) based on the degree of foramen magnum narrowing and spinal cord changes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Anatomical parameters measured from MRI scans are presented as mean (standard deviation) and median (range). Parameters were compared between the achondroplasia and reference groups using a Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples based on a 0.05 significance level.

3. Results

A total of 37 MRI images from 20 males and 17 females with confirmed achondroplasia were analyzed and compared with 37 MRI scans from 23 males and 14 females without achondroplasia. Within the achondroplasia group, 13 patients (6 females and 7 males) had received decompression surgery of the foramen magnum.

The mean age of the children with achondroplasia at the time of MRI was 1.1 years (1.1 years in those who had received decompression surgery and 0.9 years in those who had not received decompression surgery), while the mean age of the reference group was 1.7 years (

Table 1). The oldest patient at the time of MRI across both groups was 3.9 years.

Illustrative examples of key anatomical structures on MRI scans from children with achondroplasia are shown in

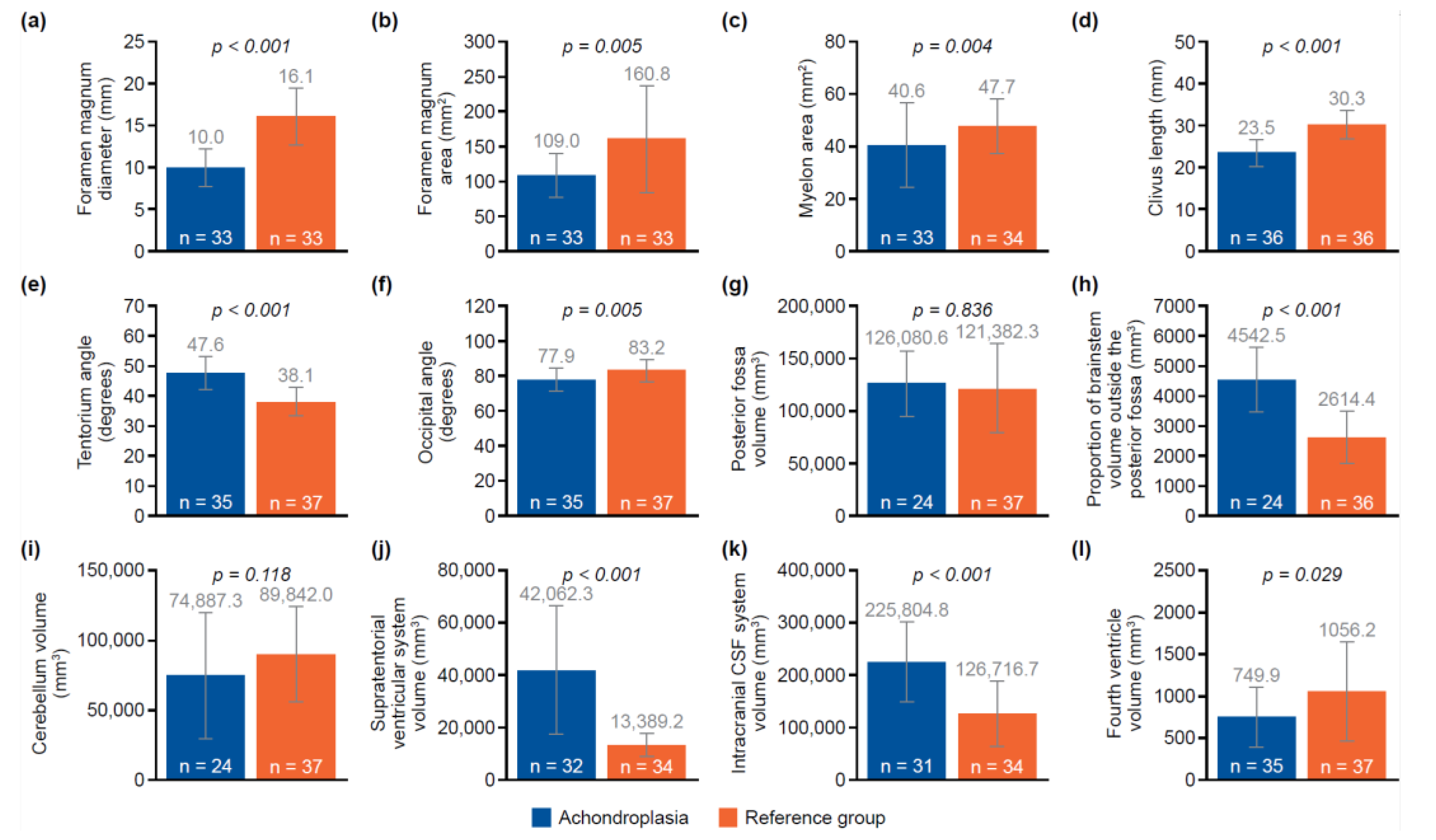

Figure 1. Of the 12 parameters measured and analyzed from the MRI scans, 10 showed significant differences between the achondroplasia and reference groups (

Figure 2;

Table S1). The diameter (mean 10.0 mm vs. 16.1 mm;

p < 0.001) and area (mean 109.0 mm

2 vs. 160.8 mm

2;

p = 0.005) of the foramen magnum were significantly smaller in children with achondroplasia compared with the reference group. Furthermore, the myelon area was significantly smaller (mean 40.6 mm

2 vs. 47.7 mm

2;

p = 0.004) and the clivus significantly shorter (mean 23.5 mm vs. 30.3 mm;

p < 0.001) in children with achondroplasia. The tentorium angle was significantly steeper in children with achondroplasia (mean 47.6 degrees vs. 38.1 degrees;

p < 0.001) and was accompanied by a larger volume of “overhang” of the brainstem from the posterior cranial fossa (mean 4542.5 mm

3 vs. 2614.4 mm

3;

p < 0.001). A significantly smaller volume of the fourth ventricle (mean 749.9 mm

3 vs. 1056.2 mm

3;

p = 0.029) and corresponding significantly larger volume of the supratentorial ventricular system (mean 42,062.3 mm

3 vs. 13,389.2 mm

3;

p < 0.001) was also observed. No significant differences between the achondroplasia and reference groups were observed in posterior fossa or cerebellum volume.

When comparing children with achondroplasia who had received decompression surgery with those who had not, the diameter of the foramen magnum showed a significant difference between groups (

Table 2;

p < 0.05).

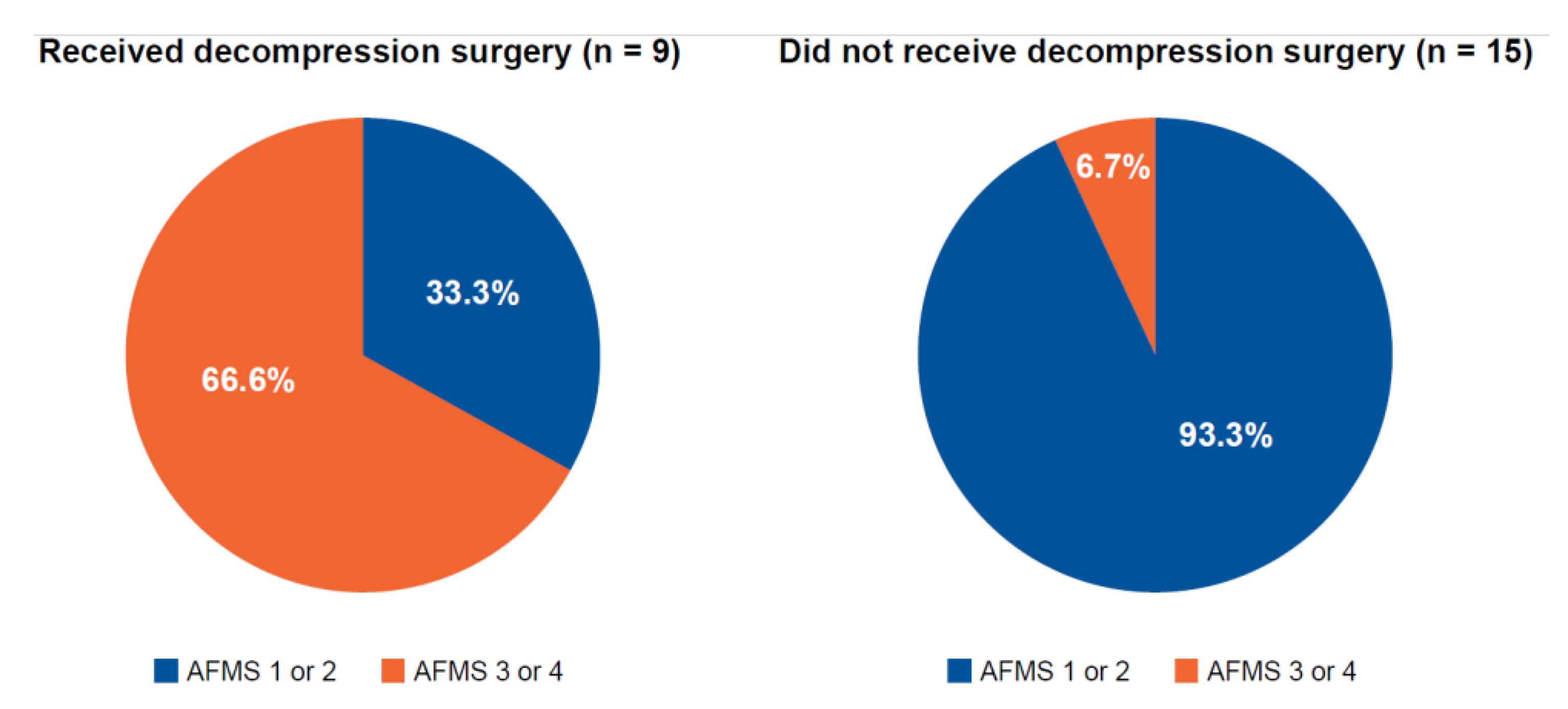

AFMS could be retrospectively determined in 24 of the 37 children with achondroplasia (

Figure 3). Of these, 9 children underwent decompression surgery, of whom, 6 (66.7%) had an AFMS score of 3 or 4. Of the 15 children who did not undergo decompression surgery, 14 had an AFMS score of 1 or 2 (93.3%). Measures of the diameter of the foramen magnum, the clivus length, the tentorial angle, the fourth ventricle volume, the supratentorial CSF system volume, and the area of “overhang” of the brainstem from the posterior cranial fossa were consistent with the AFMS (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Cervicomedullary compression and FMS are well recognized complications of achondroplasia, with infants and younger children at higher risk of these complications than adults and older children [

5,

15]. Certain measures, such as the AFMS, have been developed to aid identification of early spinal cord changes and grade severity of FMS. However, identifying candidates for decompression surgery remains an area of inconsistency.

The present study aimed to identify further anatomical characteristics in children with achondroplasia on MRI scans that may allow a standard indication for decompression surgery. Of 12 parameters defined and measured in MRI images from children with achondroplasia, 10 showed significant differences compared with the reference population. Some of the differences identified were consistent with previous studies in children with achondroplasia. While a reduction in foramen magnum area and diameter is well characterized in children with achondroplasia [

15], the postulated link to a shorter posterior cranial fossa due to underdevelopment of the occipital bone components [

18] was not confirmed in our study. This may have been related to a disparity in the number of children with complete imaging of the posterior fossa (n = 24 in the achondroplasia group vs. n = 37 in the reference group). Our study was also consistent with previous studies showing a shortening of the clivus in achondroplasia [

18]. The underlying reason for clivus shortening might be the early fusion of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis [

19]. A correlation between the length of the clivus and the supratentorial ventricular system, caused by either a CSF flow modeling effect during development or an early closure of spheno-occipital synchondrosis leading to the characteristic concave shape of the shortened clivus has been shown previously [

19]. However, in contrast to previous results [

19], our results also revealed changes in the fourth ventricle and the supratentorial ventricular system. While the fourth ventricle was smaller in children with achondroplasia, the volume of the supratentorial ventricular system was increased.

The alignment of the tentorial angle in children with achondroplasia has been characterized extensively in previous studies [

18,

19]. Accordingly, a significantly steeper angle in children with achondroplasia was observed in our study versus the reference group. It is noteworthy that the tentorial angle represented one of the borderlines in the measurement of the posterior fossa, the volume of which, in turn, determines the “overhang” of the brainstem beyond the posterior fossa. As a result, the increased volume of the overhang coincided with the steeper tentorial angle in children with achondroplasia versus the reference group. An increased tentorial angle caused by vertical orientation of the cerebellar tentorium supports the view that the tentorium is pushed forward and becomes steeper in children with achondroplasia to compensate for the undersized cranial base bone and abnormal growth of the neural structures of the posterior fossa [

19].

A relative increase in volume of the brainstem may occur in achondroplasia, a disorder in which the skull base bone is primarily affected [

20]. However, this could not be precisely demonstrated in our study as only the bony rim of the posterior fossa and the overload were measured, not the neural structures in the posterior fossa.

MRI measurements of the degree of narrowing of the foramen magnum were also used in development of the AFMS, in conjunction with preservation of the CSF and evidence of spinal cord compression [

15]. Retrospectively applying AFMS criteria to our achondroplasia cohort indicated that the decision to conduct decompression surgery was made correctly in 66.3% of those operated upon, based on those who would have scored 3 or 4 on preoperative MRI scans; 93.3% of patients with an AFMS score of 1 or 2 did not receive surgery. Eligibility for decompression surgery is based on evidence of spinal cord compression in the absence of spinal cord signal changes (AFMS3), or evidence of both spinal cord compression and spinal cord signal changes (AFMS4) [

15]. In the present study, six of the 12 parameters measured on MRI scans aligned with AFMS when the latter scores were considered in their totality. This was not surprising, as these parameters overlapped with those that showed significant differences between children with achondroplasia and the reference population.

The present study had some limitations. Sample sizes were small, with 37 patients in both the achondroplasia and reference groups, and only 14 and 23 patients, respectively, in the operated and non-operated subgroups. Due to the retrospective study design, some MRI sequences were missing or the anatomical structure under investigation was not pictured fully; therefore, not every parameter could be measured in all children. Nevertheless, the rarity of achondroplasia precludes enrollment of a large cohort of infants of the same age with a preoperative MRI. In addition, use of Dornheim Segmenter software [

17] was associated with some limitations during measurement. For example, poor focus in some MRI images may have prevented reliable identification of certain structures.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, MRI analysis of anatomical structures such as the clivus, supratentorial ventricular system, tentorium angle, and brainstem protrusion, in combination with the AFMS, may provide a standard indication for decompression surgery. Further investigation is needed to improve understanding of the correlation between the anatomical structures and clinical presentation of children with achondroplasia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Analysis of anatomical parameters on MRI scans in children with achondroplasia compared with the reference group.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the following: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Medical writing support for preparation of the manuscript was funded by BioMarin.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the opinion of the Ethics Committee of the Magdeburg University Hospital Medical Faculty, whereby an evaluation of stored data is permitted in accordance with the doctor–patient contract, the General Contractual Conditions (AVB) for the University Hospital Magdeburg, Institution under Public Law (A.ö.R) i. d. a. F., via § 16 (5).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived. The study was conducted in accordance with the opinion of the Ethics Committee of the Magdeburg University Hospital Medical Faculty, whereby an evaluation of stored data is permitted in accordance with the doctor–patient contract, the General Con-tractual Conditions (AVB) for the University Hospital Magdeburg, Institution under Public Law (A.ö.R) i. d. a. F., via § 16 (5).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating patients and their families. Medical writing support was provided by Ben Drever, PhD, of AMICULUM Ltd, and was funded by BioMarin.

Conflicts of Interest

IT has received medical writing support, funded by BioMarin. DB has received medical writing support, funded by BioMarin; consulting fees from Phenox, Balt, Acandis and Stryker; and honoraria for speaking engagements from Stryker and Acandis. PK has received medical writing support, funded by BioMarin. JG has received medical writing support, funded by BioMarin. KM has received medical writing support, funded by BioMarin; grants, consulting fees and participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from BioMarin, QED Biobridge, Novo-Nordisk, and Ascendis; honoraria for speaking engagements from BioMarin, Novo-Nordisk and Merck; and support for meeting attendance from BioMarin and Merck.

References

- Waller, D.K.; Correa, A.; Vo, T.M.; Wang, Y.; Hobbs, C.; Langlois, P.H.; Pearson, K.; Romitti, P.A.; Shaw, G.M.; Hecht, J.T. The population-based prevalence of achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia in selected regions of the US. Am J Med Genet A 2008, 146a, 2385–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, K.B.; Abiri, O.O.; Scheuerle, A.E.; Langlois, P.H. Descriptive epidemiology of selected heritable birth defects in Texas. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2011, 91, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Buck, C.O.; Orioli, I.M.; da Graça Dutra, M.; Lopez-Camelo, J.; Castilla, E.E.; Cavalcanti, D.P. Clinical epidemiology of skeletal dysplasias in South America. Am J Med Genet A 2012, 158a, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, D.A.; Carey, J.C.; Byrne, J.L.; Srisukhumbowornchai, S.; Feldkamp, M.L. Analysis of skeletal dysplasias in the Utah population. Am J Med Genet A 2012, 158a, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarirayan, R.; Ireland, P.; Irving, M.; Thompson, D.; Alves, I.; Baratela, W.A.R.; Betts, J.; Bober, M.B.; Boero, S.; Briddell, J.; et al. International Consensus Statement on the diagnosis, multidisciplinary management and lifelong care of individuals with achondroplasia. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellus, G.A.; Hefferon, T.W.; Ortiz de Luna, R.I.; Hecht, J.T.; Horton, W.A.; Machado, M.; Kaitila, I.; McIntosh, I.; Francomano, C.A. Achondroplasia is defined by recurrent G380R mutations of FGFR3. Am J Hum Genet 1995, 56, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, F.; Bonaventure, J.; Legeai-Mallet, L.; Pelet, A.; Rozet, J.M.; Maroteaux, P.; Le Merrer, M.; Munnich, A. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature 1994, 371, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rocco, F.; Biosse Duplan, M.; Heuzé, Y.; Kaci, N.; Komla-Ebri, D.; Munnich, A.; Mugniery, E.; Benoist-Lasselin, C.; Legeai-Mallet, L. FGFR3 mutation causes abnormal membranous ossification in achondroplasia. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 2914–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, M.; AlSayed, M.; Arundel, P.; Baujat, G.; Ben-Omran, T.; Boero, S.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Fredwall, S.; Guillen-Navarro, E.; Hoyer-Kuhn, H.; et al. European Achondroplasia Forum guiding principles for the detection and management of foramen magnum stenosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023, 18, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficke, J.; Varacallo, M. Anatomy, head and neck: Foramen Magnum. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli, R.M.; Scott, C.I.; Wassman, E.R., Jr.; Gilbert, E.F.; Leavitt, L.A.; Ver Hoeve, J.; Hall, J.G.; Partington, M.W.; Jones, K.L.; Sommer, A.; et al. Apnea and sudden unexpected death in infants with achondroplasia. J Pediatr 1984, 104, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, R.M. Achondroplasia: a comprehensive clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, R.M.; Horton, V.K.; Glinski, L.P.; Reiser, C.A. Prospective assessment of risks for cervicomedullary-junction compression in infants with achondroplasia. Am J Hum Genet 1995, 56, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Tovar-Baudin, A.; Del Castillo-Ruiz, V.; Rodriguez, H.P.; Collado, M.A.; Mora, T.M.; Rueda-Franco, F.; Gonzalez-Astiazaran, A. Early detection of neurological manifestations in achondroplasia. Childs Nerv Syst 1997, 13, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, M.S.; Irving, M.; Cocca, A.; Santos, R.; Shaunak, M.; Dougherty, H.; Siddiqui, A.; Gringras, P.; Thompson, D. Achondroplasia Foramen Magnum Score: screening infants for stenosis. Arch Dis Child 2021, 106, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunkel, P.; Al Halak, M.; Bechthold-Dalla Pozza, S.; Grasemann, C.; Keller, A.; Muschol, N.; Nader, S.; Palm, K.; Poetzsch, S.; Rohrer, T.; et al. Multidisciplinary approach in achondroplasia – real world experience after drug approval of vosoritide. In Proceedings of the Poster presented at the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) annual conference, The Hague, Netherlands, 2023, 21-23 September; pp. 1–414.

- Dornheim Medical Images GmbH. Dornheim Segmenter. Available online: https://dornheim.tech/en/segmenter (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Bianchi, F.; Benato, A.; Frassanito, P.; Tamburrini, G.; Massimi, L. Functional and morphological changes in hypoplasic posterior fossa. Childs Nerv Syst 2021, 37, 3093–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calandrelli, R.; Panfili, M.; D'Apolito, G.; Zampino, G.; Pedicelli, A.; Pilato, F.; Colosimo, C. Quantitative approach to the posterior cranial fossa and craniocervical junction in asymptomatic children with achondroplasia. Neuroradiology 2017, 59, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, H.M.; Yang, J.Y.; Chen, J.; Fink, A.M.; Kumbla, S. Macrocerebellum in achondroplasia: a further CNS manifestation of FGFR3 mutations? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020, 41, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).