1. Introduction

Myelomeningocele (MMC), or Meningomyelocele, is the most common open spinal dysraphism. Spinal dysraphism, also known as neural tube defect (NTD), encompasses a group of congenital malformations of the central nervous system1 , and it is traditionally classified into two categories: open spinal dysraphism (OSD) and closed spinal dysraphism (CSD)2. The abnormal fusion of the midline neural, vertebral, and mesenchymal structure occurs due to disruptions in the normal embryonic development process within a specific timeframe, namely between the 2nd and 6th weeks of gestation. This relevant time period includes gastrulation (weeks 2-3), primary neurulation (week 3-4) and secondary neurulation (week 5-6)4.

The classification of spinal dysraphism provides a structured approach to understand and manage complex clinical conditions. Most of them are based and structured on the relationship with embryological development and can become obsolete as the discoveries of molecular and embryology knowledge rapidly advance. Therefore, few different approaches have been proposed. The classification by Tortori - Donati4 for instance, focuses on clinical and neuroradiological aspects and has been proven particularly useful in everyday practice.

1.1. Aim of the study

Patients diagnosed with myelomeningocele often present with typical comorbidities, including Chiari type 2 malformation, hydrocephalus, spinal cord tethering, and syringomyelia.

While Chiari type 2 malformation, spinal cord tethering, and syringomyelia may be evident on radiological imaging, they may not always manifest clinically, allowing patients to remain asymptomatic for an extended period, sometimes throughout their lifetime.

Focusing on syringomyelia, only a few of the affected patients will present symptoms, which usually improve after treating hydrocephalus. An even smaller minority of symptomatic patients will develop a progressive form of syringomyelia, with worsening symptoms that usually require other treatments, such as posterior fossa decompression for Chiari malformation or syrinx shunting.

In the current literature, syringomyelia in spinal dysraphism is often described in relationship with Chiari malformation and spinal cord tethering6 7 8. Many studies aimed to investigate the existence of a common pathophysiology and the correlation with liquor dynamics9 10. Data on the incidence of syringomyelia in MMC patients, the percentage of individuals showing symptoms, and the development of progressive forms are lacking.

This study aims to provide a comprehensive account of our institution’s experience with myelomeningocele over the past twenty-five years. Additionally, it seeks to analyze the epidemiological background and clinical characteristics of patients, comparing them to existing evidence. Lastly, the study investigates the incidence of syringomyelia and its progressive forms, shedding light on the associated clinical and radiological findings

3. Results

3.1. Myelomeningocele and Associated Anomalies

A total of 39 patients (19:20 male to female ratio) that matched the inclusion criteria were identified through database screening. The location of MMC was lumbosacral in 31 (79.5%) patients, thoracic in 4 (10.3%), sacral in 2 (5.1%), and cervical in 2 (5.1%).

None of the patients presented an associated anterior myelomeningocele.

Additional vertebral anomalies, classified into failure of segmentation (block vertebra, unilateral unsegmented bar), and failure of formation (butterfly vertebra, hemivertebra, wedge vertebra) were investigated. None of the patients presented any additional vertebral anomalies.

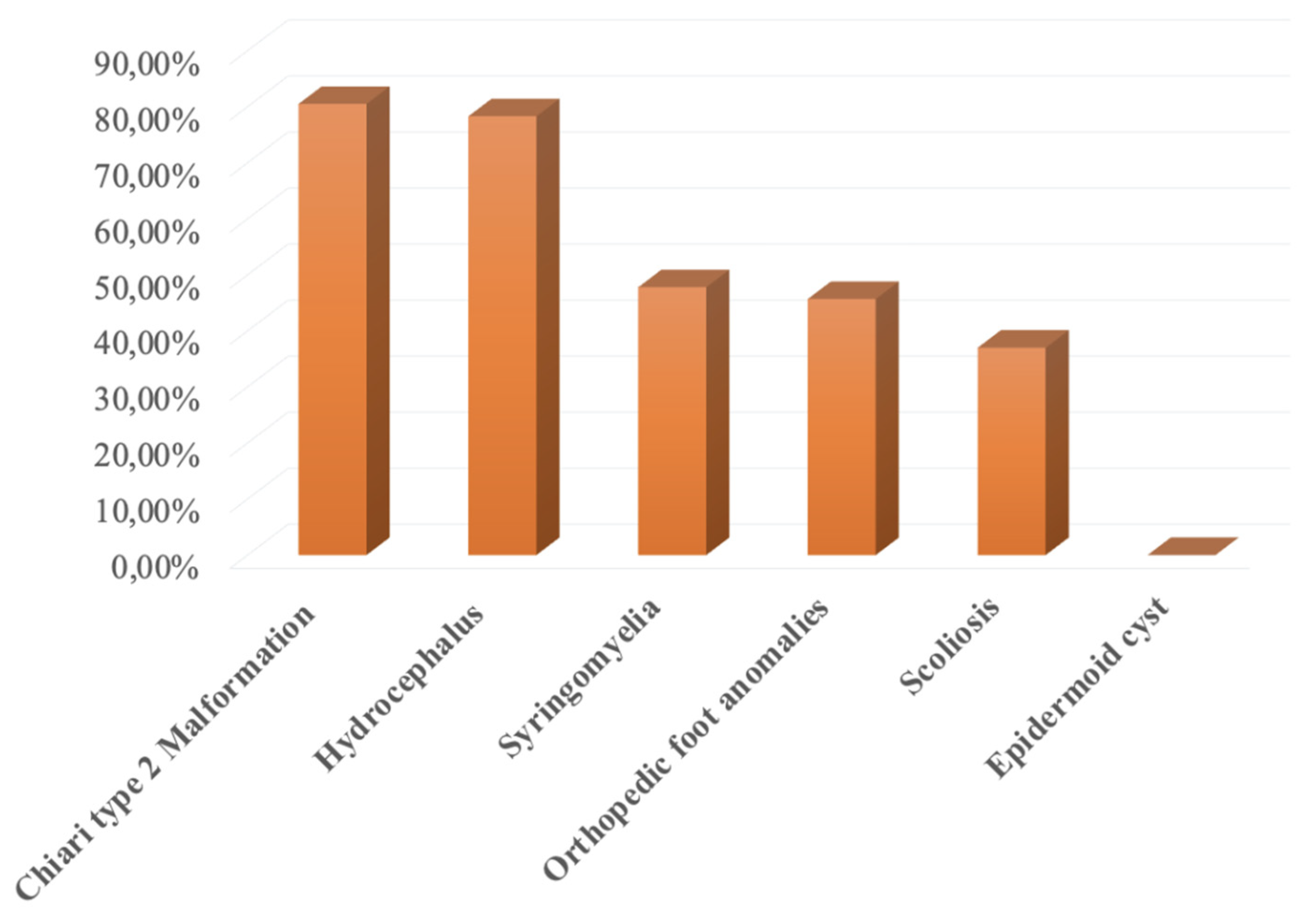

Thirty-seven patients (94.9%) presented with “other MMC associated anomalies,” classified as Hydrocephalus, Chiari type 2 Malformation (CM-II), Syringomyelia, Orthopedic foot anomalies, Scoliosis, Epidermoid cyst.

31 (79.5%) patients had Chiari Type 2 malformation, 30 (76.9%) had hydrocephalus, 21 (53.8%) syringomyelia, 20 (51.3%) orthopedic foot anomalies, 16 (41%) scoliosis, and 0 had an epidermoid cyst.

Figure 1.

MMC associated anomalies.

Figure 1.

MMC associated anomalies.

Regarding other CNS anomalies, 3 (7.7%) patients presented corpus callosum hypoplasia. Other system anomalies that were investigated included the following systems: urinary tract 39 (100%) patients, hip dysplasia 10 (25.6%) patients, ocular 3 (7.7%) patients, heart 1 (2.6%) patient, anorectal 1 (2.6%) patient. No tracheoesophageal malformation was recorded (0%).

3.2. Diagnosis

Concerning the timing of diagnosis, 15 (38.5%) patients received prenatal diagnosis, 21 (53.8%) patients received the diagnosis at birth, and for 3 (7.7%) patients, the diagnosis was made after birth, within the 1st and 12th month of age. Six (15.4%) patients received prenatal MRI; and the median time for prenatal MRI was the 7th month of pregnancy. All patients (100%) received postnatal MRI, with a median time of 6.34 months after birth. The execution of prenatal tests was not reported by 10 (25.6%) patients, and tests were not done by 10 (25.6%) patients. Prenatal tests were done but without diagnostic results in 10 (25.6%) patients. Echography was done by 8 (20.5%) patients, chorionic villus sampling by 1 (2.6%), and amniocentesis by 2 (5.1%) patients.

3.3. Birth History

Singleton pregnancy was documented for 36 (92.3%) patients, and twin pregnancy for 3 (7.7%). Premature birth was reported for 10 (25.6%) patients. Mean gestational age at birth was calculated at 38.04 ± 1.97 weeks.

3.4. Maternal History

Maternal history was known in 28 (71.8%) cases. Three (7.7%) patients were adopted, while 8 (20.5%) mothers could not be contacted. Mean maternal age at delivery was 30.19 years old, with 5.76 standard deviations. Mean weight gain during pregnancy was established at 11.28 kg with 3.85 standard deviations. Concerning the previous pregnancy, for 15 (53.6%) cases this was the first pregnancy, the second in 10 (35.7%), and the third one in 2 (7.1%) cases. Previous spontaneous abortions were not reported in 20 (71.4%) cases, 5 (17.9%) cases had one previous abortion, and 2 (7.1%) cases had 2.

None of the documented maternal histories indicated prior instances of congenital malformations in their offspring. Two (7.1%) cases reported congenital malformations in the family history, and other two (7.1%) cases reported a history of NTD in the family, affecting the aunt and cousin of the newborn.

Maternal exposure to smoking, substance abuse, and anti-epileptic therapy was evaluated, with none of the mothers declaring exposure. Diabetes was found in one (3.6%) patient.

Regarding the protective impact of folic acid intake, only 2 patients (5.1%) reported a daily folic acid assumption during pregnancy exceeding 0.4 mg. The majority of cases (53.8%) indicated insufficient, irregular, or no folic acid intake during pregnancy, while information was unavailable for the remaining 14 cases (35.9%).

3.5. Clinical Features

Clinical features are summarized in

Table 1.

3.6. Syringomyelia Group

Of the total 39 MMC patients enrolled in the study, 18 (46.2%) presented syringomyelia. The location of syringomyelia was thoracic in 6 (33.3%) patients, thoracolumbar in 5 (27.8%), cervico-thoracic in 2 (11.1%), and cervical in 1 (5.6%). 4 (22.2%) patients had holo-cord syrinx. All 18 syringomyelia patients presented with Chiari type 2 malformation and hydrocephalus, for which they all underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) implantation. Nine (50%) patients underwent secondary endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV), 7 operations out of 9 were successful, and patients were shunt-free at the last follow-up.

15 (83.3%) patients presented radiological signs of spinal cord tethering, 3 (16.7%) patients were symptomatic and underwent surgical detethering. Twelve patients (66.7%) had a diagnosis of scoliosis. Concerning the evolution of syringomyelia, the median time for patients’ follow-up was 109.3 months.

Thirteen (72.2%) patients showed no symptoms that could be related to syringomyelia. At follow-up imaging, eleven (73.3%) patients had a stable MRI, and 2 (13.3%) patients showed an improvement in terms of reduction of syringomyelia extension.

Three (16.7%) patients showed worsened radiological scenarios and invalidating symptoms that required surgical intervention. Two of them improved after secondary ETV and further interventions were not necessary. The third patient, still symptomatic after a prior surgery of posterior fossa decompression, underwent the placement of syringo-peritoneal shunt. Symptomatology and radiological pictures were declared as stable at last follow-up.

4. Discussion

At our institution the incidence of syringomyelia is 46.2% in pediatric patients with myelomeningocele in the last 25 years. Symptomatic and progressive syringomyelia accounted for 16.7%; two patients improved after the management of hydrocephalus with II ETV, and only one patient required intervention with syrinx-shunting

Syringomyelia is a disease characterized by the development of a fluid-filled cavity known as a syrinx within the spinal cord.

The term “syrinx” can be used to indicate both syringomyelia, defined as the abnormal gliotic-lined fluid-filled cavity located within the spinal cord parenchyma, and hydromyelia11 12, which is a focal dilation of the central canal. In the literature, this terminology has often been used interchangeably and is occasionally combined as syringohydromyelia13.

The most frequent etiology of syringomyelia in both adult and pediatric populations is Chiari I malformation14, representing 48-50% of adult patients and 43.2% of pediatric ones15. In pediatric populations, the next most associated conditions are idiopathic16 (30.6%), spinal dysraphism (7.4%), tumor (5.5%), and tethered cord (4.8%)15.

Presently, the pathophysiology of syringomyelia is still not fully understood. Many different theories have been proposed over time and, as suggested by Blegvad et al.13, can be broadly subdivided into three main classes. The first class of theories centers on altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, encompassing Gardner’s “water hammer” theory (1965), Williams’ “suck and slosh’’ theory (1969), Ball and Dayan’s infiltration theory (1972), Oldfield’s piston theory (1994), Heiss’s theory (2012), Levine’s theory (2004), and Koyanagi and Houkin’s theory (2010)19.

The second class of theories proposes that trauma (20, 21, 22), spinal cord tumors (23), and tethered cord conditions may lead to intramedullary tissue damage, potentially resulting in syrinx formation through hemorrhage or infarction.

Finally, certain instances of spinal cord tumors have revealed syrinx fluid with a higher protein concentration than normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and syrinx fluid associated with other causes. This observation suggests the potential secretory ability of the intramedullary tumor itself.

The relationship between syringomyelia and myelomeningocele, Chiari type 2 malformation, hydrocephalus, and spinal cord tethering (SCT) is complex and multifactorial.

Through the years, many theories have been proposed, frequently offering unique insights into cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and aiming to find unifying hypotheses on the etiology and physiopathology of these conditions10 24 25 26.

This discussion aims to explore the associations between syringomyelia and these conditions, accordingly to the literature and our experience at Meyer Children’s Hospital IRCCS.

The radiological incidence of syringomyelia in patients with myelomeningocele varies from 19% up to 48.5% in the literature27.

In our experience, the incidence of syringomyelia was 46.2%, predominantly in its thoracolumbar (27.8%) and holo-cord (22.2%) forms.

Caldarelli et al. suggested that the incidence of syringomyelia may be underestimated, and that may relying on the radiological images27.

The patients may be asymptomatic until very late, and the clinical symptoms are often overlapping with the possible manifestation of hydrocephalus, VP shunt malfunction, or Chiari malformation, making it difficult to identify the diagnosis relying only on the clinical features.

The same study by Caldarelli et al. also provides valuable insights concerning the treatment of syringomyelia in spina bifida, emphasizing the importance of early surgical intervention to prevent further neurological deterioration27.

In addition, the literature review by Piatt et al. underlines that any treatment algorithms for syringomyelia in MMC patients have not been established by randomized controlled trials so far, and further evidence is required28.

Concerning the treatment plan and relationship of syringomyelia with hydrocephalus, it’s worth mentioning that some authors proposed syringomyelia as an acquired lesion, due to abnormal CSF flow, and not as a congenital condition9. This hypothesis can be tested by clinical practice and common experience, as the proper management of hydrocephalus often improves and solves syringomyelia, even in its symptomatic forms.

In our series, out of the three patients who presented symptomatic syringomyelia and required intervention, two of them underwent secondary ETV for hydrocephalus achieving symptom resolution and were declared asymptomatic at last follow-up.

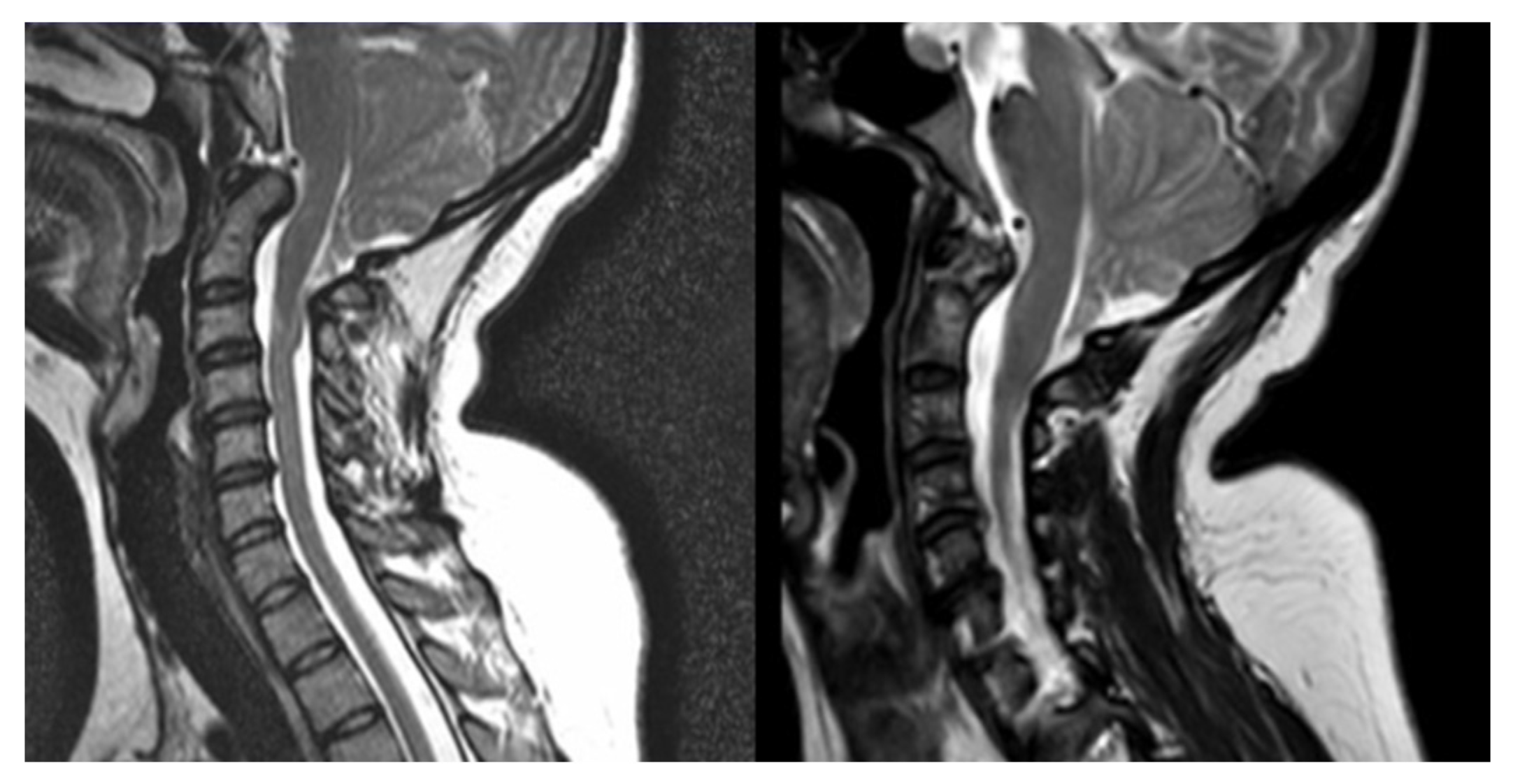

Figure 2.

T2-MRI of patient record n°3, before (left) and after (right) II ETV.

Figure 2.

T2-MRI of patient record n°3, before (left) and after (right) II ETV.

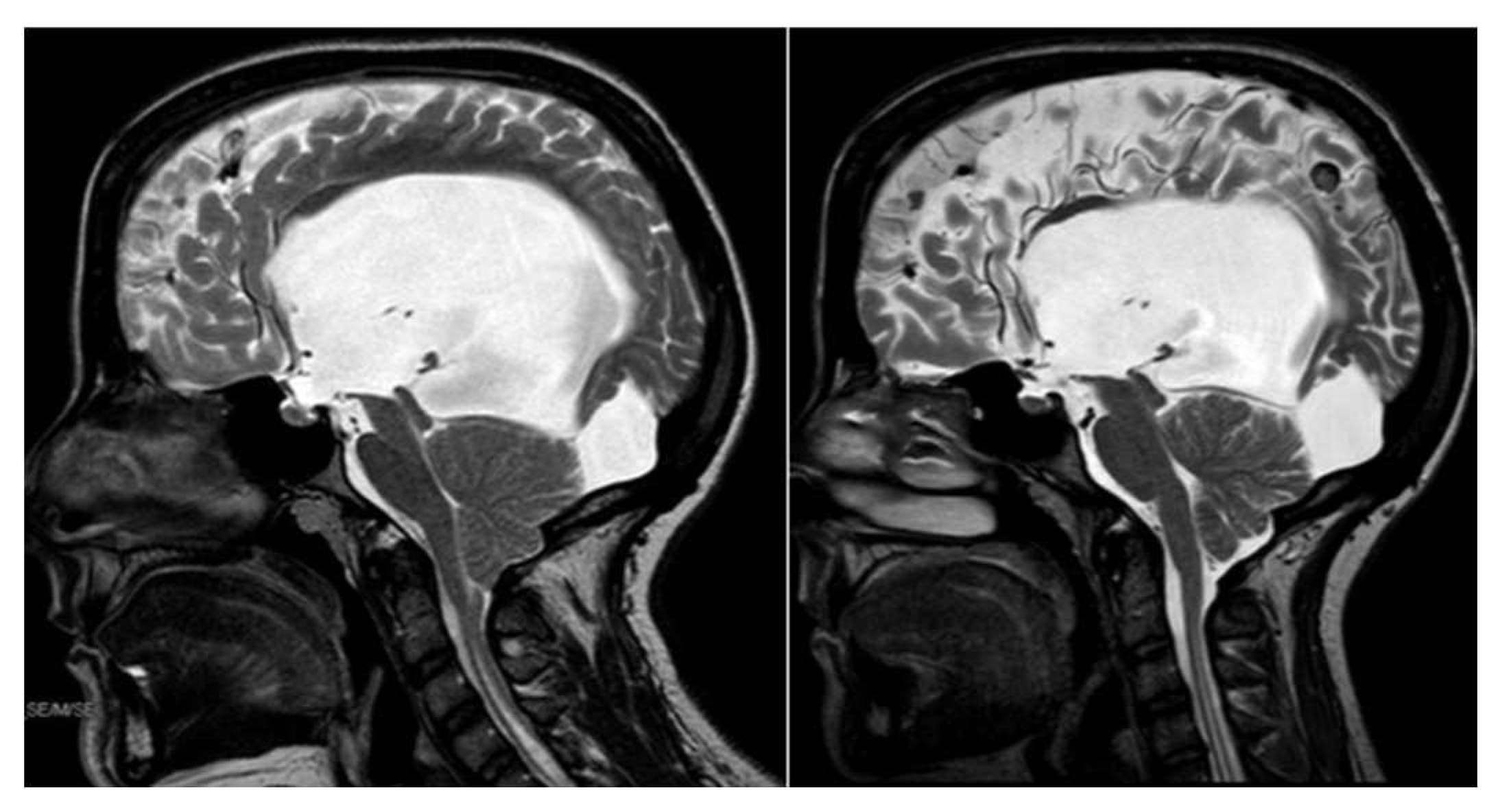

Figure 3.

T2-MRI of patient record n°13, before (left) and after (right) II ETV. In the second MRI the flow void through the aqueduct can be appreciated along with the reopening of the cisterna magna.

Figure 3.

T2-MRI of patient record n°13, before (left) and after (right) II ETV. In the second MRI the flow void through the aqueduct can be appreciated along with the reopening of the cisterna magna.

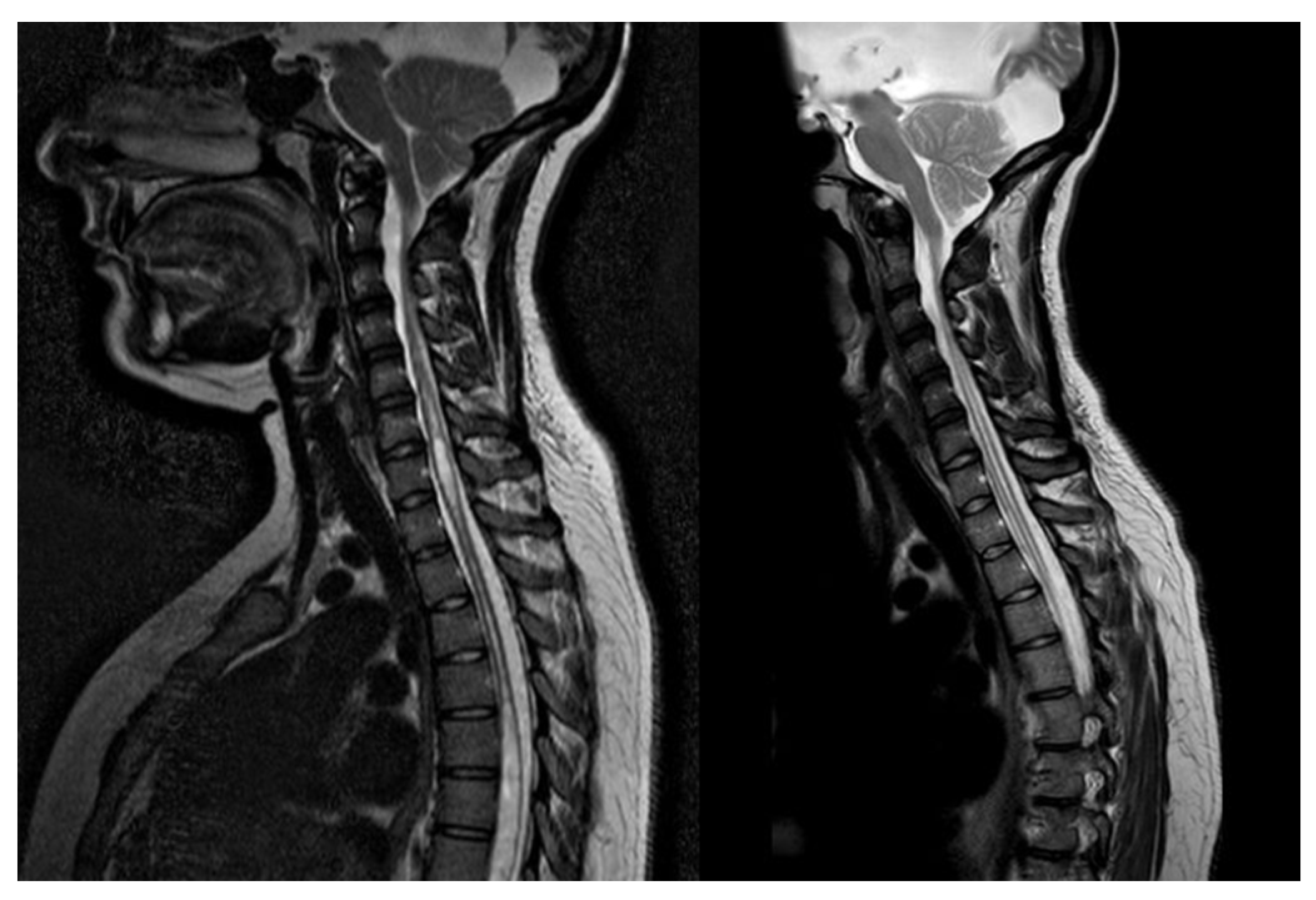

Figure 4.

T2-MRI of patient record n°13, syringomyelia before (left) and after (right) II ETV.

Figure 4.

T2-MRI of patient record n°13, syringomyelia before (left) and after (right) II ETV.

In opposition to past beliefs, CM-II is not always present in MMC and its outcomes improve significantly after MMC repair5.

Beuriat et al. published a series where 77% of patients had CM-II at birth and proved a reversibility rate of 40.4%5. The overall syringomyelia incidence in their center was 37.7%.

Concerning the relationship between CM-II and syringomyelia, they found a significant difference with a large predominance of patients without syringomyelia in the group of patients without CM-II (P < 0.001)5.

In our experience, CM-II was present in 80.5% of the total number of MMC patients, and in all (100%) of MMC patients with syringomyelia. Four (17.4%) of the patients with CM-II and syringomyelia presented symptoms that required posterior fossa decompression (PFD) surgery.

Notably, one of these five patients undergoing PFD surgery presented a progressive form of syringomyelia, and the symptomatology did not improve after the surgery for Chiari29. It was the only case in our series that required a syringo-peritoneal shunt.

Concerning the incidence of spinal cord tethering in myelomeningocele (MMC), a more comprehensive body of evidence is available in the literature.

Al-Holou et al. described secondary tethered cord syndrome (STCS), the constellation of symptoms of tethered cord that may present after an initial untethering or initial repair of primary spinal pathologies6.

In MMC patients, the prevalence of STCS has been reported between 3% and 32% 6 30. After surgical detethering of the spinal cord, many patients exhibit anatomical and radiographic signs of re-tethering, even if most of these do not experience any noticeable symptoms. Conversely, a subset of patients may develop new symptoms or a decline in functionality due to a recurrence of tethering and are often referred to as “multiple repeat tethered cord syndrome”.

The estimated prevalence of recurrent symptomatic tethering stands at approximately 20%6. Considering SCT and syringomyelia, Lee et al. stated that the underlying pathogenetic mechanism differs between syringomyelia cases associated with spinal dysraphism and those linked to hindbrain herniation50. Distinguishing the symptoms of terminal syringomyelia from those caused by spinal dysraphism can be challenging. However, syringomyelia may hold important clinical significance as it can represent one of the earliest indicators of retethering. In the article published by Tsitouras et al., the epidemiology, embryology, pathophysiology of syringomyelia in tethered cord syndrome, up to diagnosis and treatment, are deeply explored7. It is clearly underlined that the treatment of symptomatic patients should start from the spinal cord and that syringomyelia should be addressed only after the complete untethering if the patient is still symptomatic. In their experience, appropriate untethering is indeed sufficient to address the development of syringomyelia itself7.

In our experience, fifteen (83.3%) patients of the total 18 presenting with syringomyelia showed radiological signs of spinal cord tethering. Only 3 (16.7%) patients were symptomatic and underwent surgical detethering, with symptom relief. However, it is necessary to point out that the syringomyelia in all three patients undergoing spinal untethering was stable also before spine surgery, and we were therefore not able to compare our series in the same terms as the ones proposed by Tsitouras et al.7.