1. Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunting remains a cornerstone in the neurosurgical management of pediatric hydrocephalus. The Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt implantation constitutes one of the most commonly performed procedures to alleviate increased intracranial pressure, particularly in cases of obstructive hydrocephalus. Despite substantial advancements in valve technology and an increasingly refined understanding of CSF physiology, overdrainage remains a prevalent and challenging complication, particularly in long-term shunt-dependent patients. CSF overdrainage represents a unique pathophysiological state characterised by sustained intracranial hypovolaemia and hypotension, often associated with the development of slit ventricles, subdural fluid collections, rebound hypertension, and cranial vault deformation. It leads to ventricular collapse and compensatory filling of the intracranial cavity with neural tissue. The result is a nonexpansile, synostotic skull occupied by brain, blood, cerebral vasculature, meninges, and only small amounts of cerebrospinal fluid, allowing no compensatory room for fluctuations in intracranial volume [

1] In children or young adults, the morphology of the skull can be altered by excessive drainage of CSF following placement of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt [

2]. In a subset of patients, chronic overdrainage results in characteristic calvarial remodeling and thickening. The first reports of this phenomenon—hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo—were described by Moseley et al. in 1966 in children treated with shunting procedure for hydrocephalus [

3].

Hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo constitutes a physiological, compensatory response to chronically reduced intracranial pressure. It is characterised by diffuse inward calvarial remodelling, with predominant thickening of the inner table of the skull, leading to a net reduction in intracranial volume and contributing to pressure stabilisation. This entity is pathophysiologically distinct from other causes of secondary calvarial hyperostosis, such as those of metabolic, neoplastic, or haematological origin. It should be systematically considered the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with diffuse thickening of the skull, premature suture closure, and who have previously undergone surgical intervention for hydrocephalus [

4]. This phenomenon is particularly concerning in young children, where premature synostosis and diffuse calvarial thickening may disrupt brain growth and increase the risk of long-term neurodevelopmental outcome. Furthermore, this constellation of changes may severely compromise intracranial compliance and predispose to abrupt neurological deterioration in the event of recurrent cerebrospinal fluid accumulation or shunt dysfunction.

The earliest descriptions of diffuse calvarial thickening in paediatric patients treated with ventricular shunting for hydrocephalus were reported by Moseley [

3]. Emery (1969) and Anderson (1966) documented cases of cranial vault thickening and premature suture fusion occurring as a structural response to CSF shunting procedure. Kaufman et al. (1970) and Anderson et al. (1970) noted occasional reduction of sellar volume following shunting procedure [

5]. Griscom and Oh identified children who presented with marked skull thickening after ventricular shunting. These authors concluded that inward growth of the inner table was “an uncommonly seen but physiologically reasonable accompaniment of relief of childhood hydrocephalus” [

2]. None of the initial investigators established a causal relationship between these osseous changes and sustained intracranial hypotension. Recent literature recognise hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo as a distinct pathophysiological entity, emerging as a delayed calvarial remodelling process in the setting of chronic cerebrospinal fluid overdrainage and prolonged intracranial hypopressure.

The pathogenesis of hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo is increasingly understood as a multifactorial, compensatory response to sustained intracranial hypovolaemia, most often secondary to chronic cerebrospinal fluid overdrainage in long-term shunt-dependent patients. Prolonged intracranial hypotension is thought to exert centripetal vector forces on the calvarial vault– predominantly affecting the inner table, leading to a measurable reduction in intracranial volume and sagittal vault length, a phenomenon substantiated by longitudinal neuroimaging studies [

2]. Mechanotransductive signaling via the dura mater, which serves as the endocranial periosteum and is structurally anchored to the cranial base by fibrous reflections, appears to be pivotal in this process. The release of pathological dural tension following ventricular decompression may initiate osteogenic cascades, resulting in appositional compact bone deposition along the inner table [

6]. These alterations are frequently accompanied by a diffuse, smooth, wave-like pattern of pachymeningeal enhancement on MRI, indicative of dural hyperemia and interstitial oedema secondary to cerebrospinal hypopressure [

7,

8]. Contemporary revisions of the Monro-Kellie doctrine have refuted the notion of a rigid, inelastic calvarium, instead proposing that the skull functions as a dynamic regulatory compartment. Within this framework, hyperostotic remodeling represents an active compensatory mechanism aimed at restoring intracranial pressure homeostasis [

9]. However, such adaptation may prove maladaptive over time, restricting parenchymal re-expansion and predisposing to secondary complications such as rebound intracranial hypertension or premature suture fusion through disrupted cranial mechanobiology [

1].

Despite historical recognition of cranial vault remodeling following cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion, hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo remains an insufficiently characterized and unclassified entity within the spectrum of CSF overdrainage-related pathology. Existing taxonomies of overdrainage syndromes predominantly emphasize ventricular collapse, intracranial hypotension, and cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, while failing to account for long-term osseous adaptations involving the calvarium, skull base, and dura mater. The four currently accepted subtypes: slit ventricle syndrome, subdural fluid collections, acquired Chiari malformation, and rebound intracranial hypertension — each represent different expressions of intracranial hypovolaemia or compliance failure. Moreover, the absence of defined radiological criteria has precluded its systematic identification and nosological inclusion.

The present study aims to address this gap by delineating the radiomorphological features and clinical context of hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo in a cohort of pediatric patients with chronic shunt dependence. Through quantitative assessment of calvarial thickening, sella turcica deformation, pachymeningeal enhancement, and premature cranial suture fusion, we investigate whether this phenotype conforms to the pathophysiological hallmarks of CSF overdrainage. We hypothesise that hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo constitutes a distinct, underrecognised subtype of CSF overdrainage syndrome fulfilling the requisite morphological and mechanistic criteria for formal classification as a fifth variant within this clinical construct.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective, observational analysis conducted at the Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, University Children’s Hospital in Kraków, Poland. Clinical, radiological, and procedural data were extracted from institutional electronic medical records spanning the period from years from 2016 to 2025. All imaging was performed and archived according to standardised institutional radiology protocols, utilising computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems calibrated for paediatric neuroimaging.

2.1. Population

The study cohort included nine paediatric patients (aged 7 to 17 years; both sexes) who had been surgically treated for hydrocephalus using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunting systems - either ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or ventriculoatrial (VA) shunts, and who exhibited radiological features consistent with calvarial hyperostosis.

Inclusion criteria were:

- (1)

Age under 18 years;

- (2)

Documented diagnosis of hydrocephalus treated surgically;

- (3)

Radiologically confirmed cranial hyperostosis following shunt implantation;

- (4)

Availability of high-resolution post-shunting CT or MRI scans suitable for morphometric analysis.

Exclusion criteria included:

- (1)

Congenital bone metabolism disorders (e.g., osteogenesis imperfecta, hypophosphatasia),

- (2)

Skeletal dysplasias,

- (3)

Endocrinopathies affecting bone turnover (e.g., hyperparathyroidism, Cushing's disease),

- (4)

Long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy,

due to their potential confounding effects on cranial bone density and morphology.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection was performed by qualified clinicians. Acquisitied variables included patient demographics, age at initial shunt implantation, type of shunt system used (VP or VA), history and number of shunt revisions, presence of external ventricular drainage (EVD) or Rickham reservoir placement, latency period between shunt surgery and radiological detection of hyperostosis, incidence of central nervous system (CNS) infections, and age at diagnosis of overdrainage syndrome and cranial hyperostosis.

Radiological data were reviewed retrospectively, and morphometric assessments were conducted on the most recent cross-sectional neuroimaging studies (CT or MRI) available. Calvarial bone thickness was measured in the axial and coronal planes at three predefined anatomical landmarks: the glabella (frontal bone), the vertex (parietal bone), and the lambda (occipital-parietal suture). The maximum value at each site was recorded, and values were compared against paediatric normative data from the literature [citation].

In cases where contrast-enhanced imaging was available, the presence and degree of dural enhancement were assessed qualitatively.

2.3. Sella Turcica Morphometry

Mid-sagittal CT or MRI images were used to evaluate the morphology of the sella turcica. Reference points were determined on the coronal, sagittal and axial planes to standardize the images. Two lines were determined for the standardization of measurements, a sagittal line passing through the crista galli and anterior nasal spine on the coronal plane, and a sagittal line passing through the internal occipital protuberance and anterior nasal spine on the axial plane.

Measured parameters included: Sella turcica width (STW): the longest anteroposterior dimension between the tuberculum sellae and dorsum sellae; Sella turcica depth (STD): the perpendicular height from the deepest point of the sella floor to a line connecting the tuberculum and dorsum sellae; Sella turcica length (STL): linear distance from the tuberculum to the dorsum sellae. Sagittal sella surface area was approximated using a geometric model: Rectangular estimation: Area=STW×STD. These values were then compared to age-stratified normative reference data [cytowanie źródła].

2.4. Densitometric Analysis

In patients for whom quantitative densitometric evaluation of the calvaria was available, calvarial bone density was assessed within regions affected by hyperostosis. Measurements were interpreted in relation to reference values from paediatric normative cohorts. Cranial bone densitometry was performed using dual energy X ray absorptiometry (DXA) on a Hologic Horizon W system (S/N 307914M) equipped with software version 13.6.1.3 and calibrated according to the TBAR1209 – NHANES BCA protocol. All scans were acquired as whole body studies, with subsequent semi-automated segmentation of the “Head” region of interest (ROI) following the manufacturer’s pediatric protocol. Within the head ROI, the following parameters were quantified: Projected area (cm²), Bone mineral content, BMC (g), Areal bone mineral density, aBMD (g/cm²), Total mass (g), Lean mass (g), Combined lean + bone mineral content (g). For each parameter, mean ± standard deviation and observed range were recorded. Each ROI was inspected to ensure exclusion of extraneous soft tissue artefact and correct delineation of the cranial vault margins.

2.5. Study Outcomes

Primary outcome was to assess the association between CSF overdrainage syndrome and the development of cranial hyperostosis in paediatric patients following shunt surgery. Secondary outcomes were as follows: quantitative assessment of calvarial bone thickening (glabella, vertex, lambda) in relation to age- and sex-adjusted normative data. Morphological evaluation of sella turcica dimensions and its potential remodeling in the context of intracranial hypotension. Preliminary densitometric analysis of the affected calvarial bone in selected patients.

2.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29). Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), and ranges were reported. Due to the small sample size, no inferential statistical testing was conducted. The analysis was purely quantitative. No formal risk of bias tools were applied due to the retrospective nature of the study and absence of control groups.

2.7. Ethics Approval and Data Protection

This study was conducted in accordance with institutional, national, and international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable data protection regulations. Ethical approval was not required, as the study involved retrospective analysis of fully anonymised clinical and imaging data obtained during routine medical care, with no impact on diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. All patients and/or their legal guardians were informed during the course of treatment about the potential use of anonymised clinical data for scientific and educational purposes. Patient confidentiality was safeguarded throughout the study. All data were anonymised prior to analysis, and no identifiable personal information was used or stored. Data access was restricted to authorised members of the research team.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristic of patients are summarized in

Table 1. The study cohort comprised nine paediatric patients (six males and three females), with a mean age at the time of evaluation of 13.0 years (SD ± 2.87; range: 7-17 years). Obstructive hydrocephalus was diagnosed in eight patients (88.9%), while one case (11.1%) involved communicating hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus was diagnosis at a amean age of 42.8 months (SD ± 59.28), and initial ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt implantation was performed at a mean age of 43.2 months (SD ± 59.28). CSF overdrainage syndrome was recognised at a mean age of 87.0 months (SD ± 51.58), corresponding to a mean interval of 43.8 months after the initial shunt placement. Radiological evidence of calvarial thickening was identified at a mean age of 148.0 months (SD ± 34.59), with a mean latency period of 66.0 months (SD ± 39.47) from the onset of overdrainage to the development of radiological hyperostosis.

Fixed-pressure valves were used in 77.8% of initial shunt placements. Reimplantation of VP or VA shunts was performed in seven patients (77.8%), and in two cases, the fixed-pressure valve was replaced with a programmable one. At the time of data collection, fixed-pressure systems remained in place in 44.4% of the cohort. The most commonly used valve at first implantation was Medtronic (4 patients), set to low or medium pressure. Codman Hakim valves were used in two patients, and Miethke and Spetzler valves in one patient each. Six patients (66.7%) underwent external ventricular drainage or Rickham reservoir placement during the course of treatment. Clinical improvement following the initial shunt implantation—defined as reduction in headache and neurological symptoms—was observed in 8 of 9 patients (88.9%).

3.2. Calvarial Thickening and Morphometry

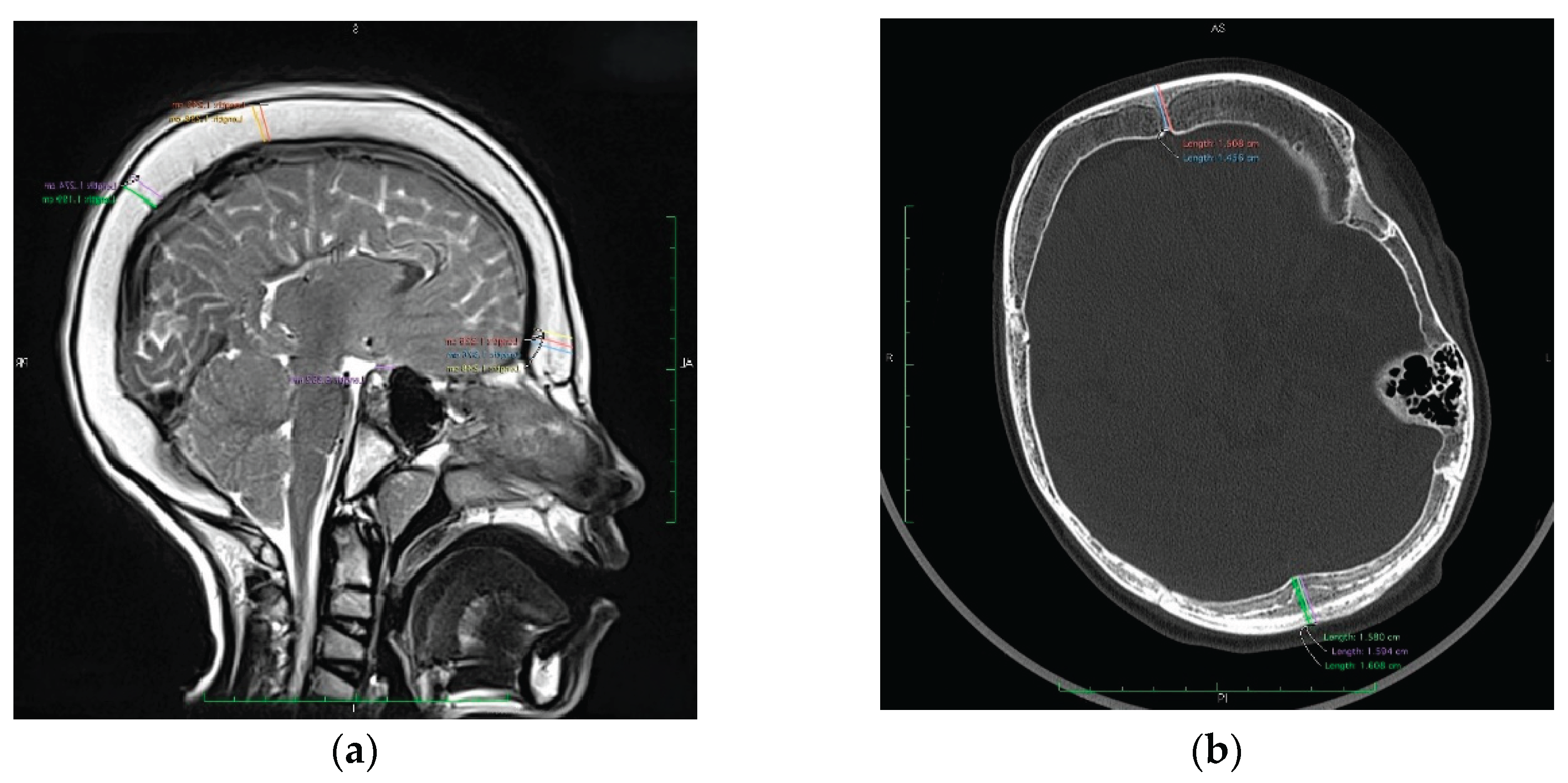

Quantitative morphometric analysis demonstrated generalised calvarial hyperostosis in all patients (

Table 2). Mean frontal bone thickness at the glabellar region was 12.77 mm (SD ± 3.07), representing a 2.1-fold increase relative to age-matched paediatric norms. Parietal bone thickness at the vertex was 11.13 mm (SD ± 2.68), corresponding to a 1.85-fold increase, and occipital bone thickness at the lambda measured 12.21 mm (SD ± 2.36), equating to a 2.02-fold age-adjusted thickening . The overall mean calvarial thickness across all measured regions was 12.04 mm (SD ± 2.70), confirming a diffuse and significant increase in cranial vault thickness (

Figure 1).

Premature cranial suture fusion was observed in 33.3% of patients, most commonly affecting the sagittal suture (3 patients). Premature fusion of the coronal and lambdoid sutures was each noted in two cases. These findings suggest that prolonged intracranial hypopressure due to CSF overdrainage may contribute to secondary craniosynostosis.

3.3. Sella Turcica Deformation and Dural Changes

Morphometric measurements of the sella turcica(

Table 3) revealed shortening of the anteroposterior dimension in five patients (55.6%). The overall mean length of the sella was 7.04 mm (SD ± 0.67), while in patients with confirmed shortening, the mean length was reduced to 6.72 mm (SD ± 0.54), reflecting an average 11% decrease. The estimated surface area of the sella turcica was reduced in eight patients (88.9%), with a mean value of 41 mm², representing approximately 82% of the expected norm. These findings indicate parasellar volume loss, likely secondary to chronic CSF depletion and associated intracranial hypopressure.

Contrast-enhanced MRI, available in seven patients, demonstrated diffuse pachymeningeal enhancement (DPE) in all cases. The observed enhancement followed a smooth, bilateral, wave-like pattern along the dura, consistent with dural hyperaemia and interstitial oedema associated with prolonged intracranial hypopressure. These imaging findings support the mechanistic association between low CSF pressure and compensatory dura–calvaria interactions.

3.4. Neurological Features and CNS Comorbidities

Focal neurological deficits were present in the majority of patients (8 out of 9; 88.9%)(

Table 4). Limb paresis was noted in five patients (55.6%), including two with spastic tetraparesis. Epilepsy was diagnosed in six patients (66.7%). Additionally, radiological features of Arnold–Chiari malformation were identified in two patients (22.2%), possibly reflecting downward brain displacement secondary to chronic CSF overdrainage.

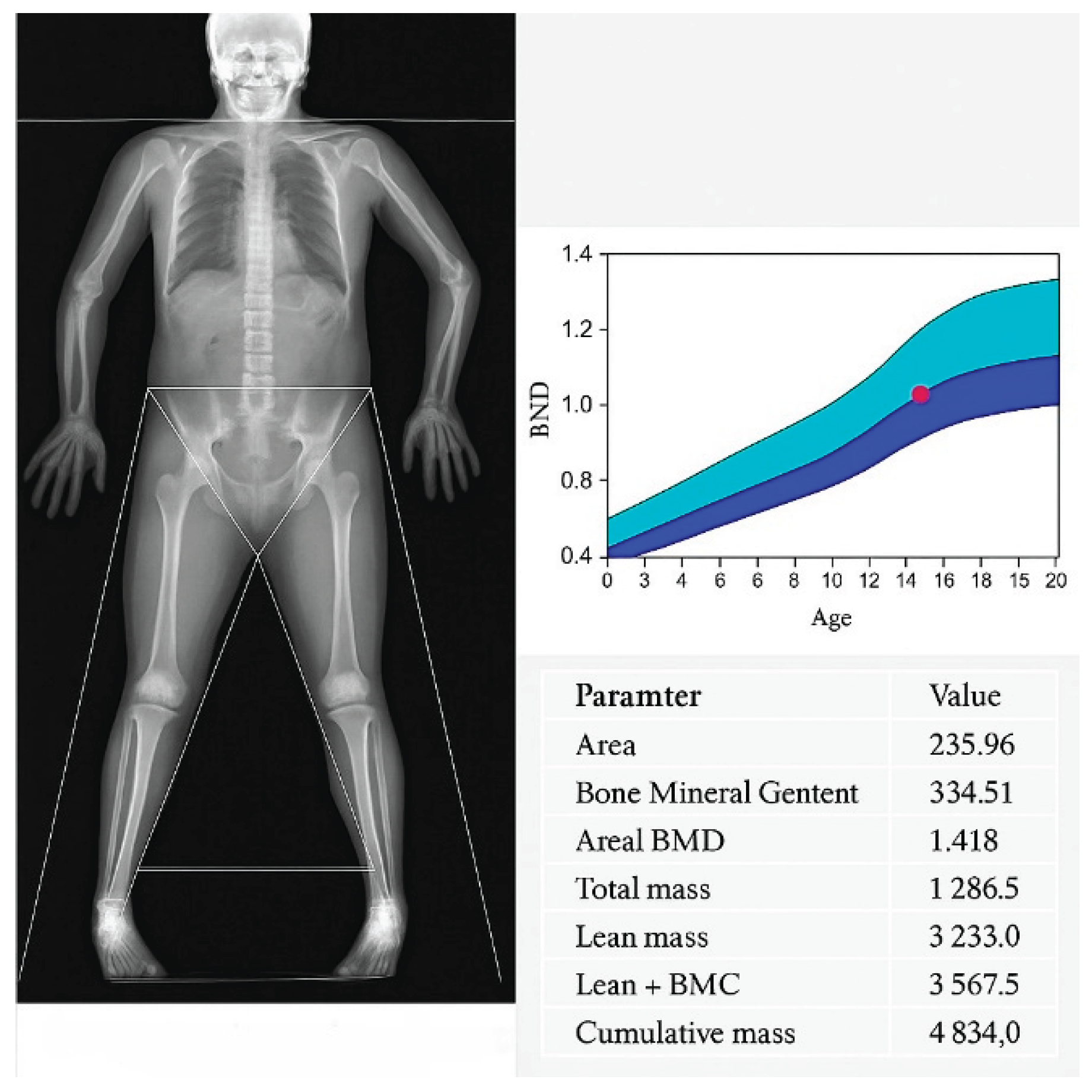

3.5. Cranial Vault Densitometric Assessment via DXA

Quantitative DXA analysis of the cranial vault ROI was performed (

Table 5,

Figure 2). The mean projected area was 213.75 ± 16.73 cm² (195.59–235.96 cm²). Bone mineral content (BMC) demonstrated a mean of 345.45 ± 46.83 g (294.35-407.45 g), whilst areal bone mineral density (aBMD) averaged 1.635 ± 0.32 g/cm² (1.404-2.083 g/cm²), consistent with estab-lished paediatric reference standards. Within the defined ROI, total mass (comprising osseous and soft tissue components) was 1 079.67 ± 154.09 g (916.7-1 286.5 g). Lean soft tissue mass alone measured 2 717.40 ± 393.49 g (2 278.3-3 233 g), and the aggregate metric of lean mass plus BMC was 3 062.83 ± 371.09 g (2 685.8-3 567.5 g). Coefficients of variation for BMC and aBMD were below 1.5%, attesting to the robustness of ROI de-lineation and instrument stability.

In conclusion, the observed densitometric parame-ters exhibited low inter subject variability and aligned favourably with normative pae-diatric datasets, thereby confirming that the cranial vault thickening is physiological in nature with no evidence of underlying pathology.

4. Discussion

Our series of nine paediatric patients with long term CSF shunting demonstrated a consistent pattern of diffuse calvarial thickening, premature craniosynostosis, dural enhancement on contrast enhanced imaging, sella turcica shrinkage and preserved physiological bone mineralisation. Eight of nine patients met the diagnostic criteria for CSF overdrainage syndrome. One patient lacked radiological signs of active ventricular narrowing at the time of imaging, although medical history revision suggests the process had occurred previously. All patients exhibited generalized thickening of the cranial bones developed secondary to overdrainage diagnosis at a mean interval of 66 months (range 12-138 months). These findings concur with available research, in which the earliest documented increase in calvarial thickness beyond the normal range was seen on skull radiographs obtained 12 months after ventriculoatrial shunt placement [

10]. Available publications report that hyperostosis develops over a period ranging from 3 years and 2 months to 8 years and 6 months [

10]. Quantitative morphometry revealed an approximate two fold increase in calvarial thickness across frontal, parietal and occipital regions compared with age matched norms, and 33 % of patients exhibited premature fusion of at least one cranial suture. Previous studies have reported mean skull thickness at midfrontal, vertex, and lambda regions averaged 2.5 times normal values for age and sex. The discrepancies between our data and those reports may reflect differences in patient age, measurement techniques or normative reference cohorts. All patients with available post contrast imaging (7/9) demonstrated smooth, wave like pachymeningeal enhancement, reflecting dural hyperaemia secondary to chronic intracranial hypotension. Radiomorphometric assessment of the sella turcica revealed an average 11 % reduction in anteroposterior length and an 18 % decrease in estimated surface area in eight out of nine patients. Neurological symptoms were present in nearly 90% of the cohort, including epilepsy, focal deficits, and features of Chiari malformation, suggesting a clinically significant impact of the underlying hypotensive state. Finally, densitometric analysis via paediatric DXA confirmed preservation of normal cranial bone mineral parameters, corroborating that calvarial hypertrophy represents appositional lamellar bone growth within standard BMC and aBMD ranges, attributable to CSF overdrainage rather than intrinsic bone pathology.

These findings of this study align with, and extend, prior isolated reports of radiographic calvarial thickening in chronically shunted patients. The co-occurrence of clinical signs of hypotensive signs, premature cranial suture closure, reduced parasellar volume, and dural enhancement provides convergent evidence for chronic CSF volume depletion as the primary mechanism. Unlike previous accounts that lacked a unifying pathophysiological framework, our data demonstrates that the observed features fulfill the core diagnostic and mechanistic criteria of CSF overdrainage syndromes. Traditionally classified entities — encompassing slit ventricle syndrome, low pressure headaches, subdural hygromas or haematomas, and craniosynostosis with cranial deformity [

6,

11,

12]. In this context, hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo emerges as an additional, structurally distinct manifestation of the same pressure compliance disturbance. The mean latency of 66 months between shunt implantation and hyperostosis onset further supports a causal relationship.

Cranial vault expansion in chronic CSF overdrainage is driven by persistent traction forces transmitted from the hypotensive intracranial compartment via the dura mater, which functions as the endocranial periosteum and conforms to the brain’s morphology [

3]. The dura is firmly anchored to cranial base by fold-like appendages, known as reflections at the crista galli, the cribriform plate, the lesser wings of the sphenoid, and the petrous temporal crests. Facilitating mechanical coupling between the brain and calvarium [

6]. Release of pathological dural tension stretching and mechanical stress, initiating local osteogenic pathways with bone apposition, leading to increased cranial vault thickness. The skull demonstrated marked expansion of the cancellous space within the bone, but otherwise normal trabeculated bone [

7]. They and Dorst’ suggested that the inner table of the skull is very sensitive to the development of the brain beneath it, and if the stimulation of the neural mass becomes static, the bones of the calvaria thicken but do not enlarge in area [

10].

A secondary mechanism implicates long term dampening of cerebral pulse pressure by CSF drainage. Both mean intracranial pressure and pulse pressure contribute to skull growth. Chronic CSF diversion thus deprives the vault of these expanding forces, resulting in reduced head circumference, vault thickening and, in some cases, premature suture fusion [

12]. The simultaneous reduction in dural expansion may promote secondary craniosynostosis through loss of tension across developing sutures, mostly affecting sagittal suture [

1]. Albright and Tyler Kabara postulate that the chronic overdrainage dampens normal cerebral pressure waves, decreasing the stimulation of calvarial growth and leading to suture ossification.

Marked reduction in sella turcica, present in the majority of patients, can be interpreted as a consequence of sustained parasellar hypopressure. This observation mirror those in adult spontaneous intracranial hypotension and suggest that detailed sella morphometry may serve as a sensitive radiological adjunct for chronic low CSF pressure, particularly in paediatric patients without overt clinical manifestations.

Smooth, bilateral, wave-like pachymeningeal enhancement was a consistent feature on contrast-enhanced MRI, distinct from the nodular or leptomeningeal patterns of inflammatory or neoplastic disease [

8,

13]. The pachymeninges comprises two fused membranes derived from the embryonic meninx primativa: the periosteum of the inner table of the skull and a meningeal layer. MR imaging is relatively sensitive and specific in the detection the pachymeninges, resulting in characteristic linear dural staining without sulcal or cortical surface enhancement. Radiological pattern, in conjunction with clinical signs of overdrainage is highly suggestive of benign intracranial hypotension [

8]. Under the Monro-Kellie doctrine, sustained intracranial hypotension causes fluid shifts and increased venous capacitance in the subarachnoid space, eventually resulting in dural venous congestion and interstitial oedema [

8].

Despite substantial osseous hypertrophy, paediatric DXA confirmed age appropriate preservation of bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density This finding excludes primary osteosclerosis or metabolic bone disease and underscores that hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo is an adaptive compensatory phenomenon driven by altered cranial biomechanics rather than systemic pathology. Recognition of this distinction can prevent unnecessary endocrinological investigations and promote multidisciplinary collaboration among neurosurgery, neuroradiology and paediatric neurology.

Hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo is a rarely reported complication of CSF shunting, occurring in only a few patients per 1,000 procedures. Its true incidence remains uncertain due to lack of consensus diagnostic criteria and under recognition. The calvarial thickening, premature closure of the sutures, and evidence of shunting procedures should greatly facilitate diagnosis [

4]. To date, no unequivocal association between this condition and CSF overdrainage syndrome has been demonstrated. The absence of a clear definition of overdrainage is reflected in the literature. There is no consensus on diagnostic criteria, and thus, the incidence remains uncertain which reflects on recommendations for prevention, management, and treatment of the condition [

11]. However, even when consensus is reached, an individual patient evaluation remains highly important.

5. Limitations

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and relatively small sample size, which limit generalisability and prevent inferential statistical analysis. Intracranial pressure was not directly measured, and diagnosis of overdrainage relied on radiological proxies and clinical history. Furthermore, while most patients were managed with fixed low-pressure valves, heterogeneity in shunt hardware may have influenced the observed outcomes. Future studies employing prospective designs and larger cohorts are required to establish definitive diagnostic criteria and explore causal relationships.5.

6. Conclusions

Hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo represents a distinct, compensatory osseous response to chronic CSF overdrainage in paediatric shunt dependent patients, characterised by diffuse inner table thickening, secondary craniosynostosis, sella turcica collapse, pachymeningeal enhacement and preserved bone mineral physiology. Formal recognition of this entity as a fifth subtype of CSF overdrainage subtype may enhance diagnostic precision and guide tailored interventions -such as valve pressure optimisation to prevent irreversible calvarial deformities. Further prospective research with comprehensive imaging and intracranial pressure monitoring is essential to refine management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SK and MZ.; Methodology, MZ.; Software, MZ.; Validation, SK, ŁK; Formal Analysis, SK; Investigation, MZ, SK, ŁK and OM; Resources, SK; Data Curation, MZ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, SK and MZ; Writing – Review & Editing, SK; Visualization, MZ; Supervision, SK; Project Administration, SK.

Funding

No funding was required for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Weinzweig, J. , Bartlett, S. P., Chen, J. C., Losee, J., Sutton, L., Duhaime, A. C., & Whitaker, L. A. (2008). Cranial vault expansion in the management of postshunt craniosynostosis and slit ventricle syndrome. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 122(4), 1171–1180. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M. K. , Parsa, A. T., & Horton, J. C. (2013). Skull thickening, paranasal sinus expansion, and sella turcica shrinkage from chronic intracranial hypotension. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 11(6), 667–672. [CrossRef]

- Moseley, J. E. , Rabinowitz, J. G., & Dziadiw, R. (n.d.). Hyperostosis Cranii ex Vacuo.

- Di Preta JA, Powers JM, Hicks DG. Hyperostosis cranii ex vacuo: a rare complication of shunting for hydrocephalus. Hum Pathol. 1994 May;25(5):545-7. [CrossRef]

- Villani, R. , Giani, S. M., Giovanelli, M., Tomei, G., Za, M. L., Enrfco, V., & Motti, D. F. (n.d.). Skull Changes and Intellectual Status in Hydrocephalic Children Following CSF Shunting.

- Haggare, J. , & Rönnmg, O. (1995). Growth of the cranial vault: Influence of intracranial and extracranial pressures. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 53(3), 192–195. [CrossRef]

- Lucey, B. P. , March, G. P., & Hutchins, G. M. (2003). Marked Calvarial Thickening and Dural Changes Following Chronic Ventricular Shunting for Shaken Baby Syndrome. In Arch Pathol Lab Med (Vol. 127).

- Antony, J. , Hacking, C., & Jeffree, R. L. (2015). Pachymeningeal enhancement—a comprehensive review of literature. In Neurosurgical Review (Vol. 38, Issue 4, pp. 649–659). Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Benson, J. C. , Madhavan, A. A., Cutsforth-Gregory, J. K., Johnson, D. R., & Carr, C. M. (2023). The Monro-Kellie Doctrine: A Review and Call for Revision. In American Journal of Neuroradiology (Vol. 44, Issue 1, pp. 2–6). American Society of Neuroradiology. [CrossRef]

- Anderson R, Kieffer SA, Wolfson JJ, Long D, Peterson HO. Thickening of the skull in surgically treated hydrocephalus. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970 Sep;110(1):96-101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S. H. , Prein, T. H., Ammar, A., Grotenhuis, A., Hamilton, M. G., Hansen, T. S., Kehler, U., Rekate, H., Thomale, U. W., & Juhler, M. (2023). How to define CSF overdrainage: a systematic literature review. Acta Neurochirurgica, 165(2), 429–441. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lage, J. F. , Ruiz-Espejo Vilar, A., Pérez-Espejo, M. A., Almagro, M. J., Ros De San Pedro, J., & Felipe Murcia, M. (2006). Shunt-related craniocerebral disproportion: Treatment with cranial vault expanding procedures. Neurosurgical Review, 29(3), 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Smirniotopoulos, J. G. , Murphy, F. M., Rushing, E. J., Rees, J. H., & Schroeder, J. W. (2007). From the archives of the AFIP: Patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges. In Radiographics (Vol. 27, Issue 2, pp. 525–551). [CrossRef]

- Delye, H. , Clijmans, T., Mommaerts, M. Y., Sloten, J. vander, & Goffin, J. (2015). Creating a normative database of age-specific 3D geometrical data, bone density, and bone thickness of the developing skull: A pilot study. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 16(6), 687–702. [CrossRef]

- Ağolday, Z. , Yıldızoğlu, E. Ö., Özdemir, E., Çetin, R., & Beger, O. (2025). Radiological anatomy of sella turcica in children: a retrospective study with CT. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, 47(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).