Introduction

Fitting data to a statistical distribution is essential for understanding the underlying processes that generate the data. Researchers have developed many distributions to describe complex real-world phenomena. Before 1980, the primary techniques for generating distributions included solving systems of differential equations, using transformations, and applying quantile function strategies. Since 1980, the methods have largely focused on either adding new parameters to existing distributions or combining already known distributions. These approaches provide researchers with a wide range of tractable and flexible distributions capable of accommodating various types of asymmetrical data, as well as outliers in data sets. Fitting distributions to data enhances modeling in analyses involving regression, survival analysis, reliability analysis, and time series analysis.

Quantile regression models are utilized by many researchers to model time-to-event response variables that exhibit skewness, long tails, and violations of normality and homogeneity assumptions. These models are robust to outliers, skewness, and heteroscedasticity as they specify the entire conditional distribution of the response variable, rather than merely the conditional mean. Many authors have applied quantile regression to investigate the effects of covariates on time-duration response variables at different quantiles. For instance, Flemming et al. (2017) [

1] studied the association between time to surgery and survival among patients with colon cancer. Faradmal et al. (2016) [2) employed censored quantile regression to examine the overall factors affecting survival in breast cancer. Xue et al. (2018) [

3] conducted an in-depth exploration of the censored quantile regression model for analyzing time-to-event data.

Numerous real-world phenomena can be represented as proportions, ratios, or fractions over the bounded interval (0,1). Various disciplines, such as biology, finance, mortality rates, recovery rates, economics, engineering, hydrology, health, and measurement sciences, have modeled these types of data using continuous distributions. Some of these distributions include: the Johnson SB distribution [

4], Beta distribution [

5], Unit Johnson distribution [

6], Topp-Leone distribution [

7], Unit Gamma distribution [

8,

9,

10,

11], Unit Logistic distribution [

12], Kumaraswamy distribution [

13], Unit Burr-III distribution [

14], Unit Modified Burr-III distribution [

15], Unit Burr-XII distribution [

16], Unit-Gompertz distribution [

17], Unit-Lindley distribution [

18], Unit-Weibull distribution [

19], Unit-Birnbaum-Saunders [

20] and Unit Muth distribution [

21].

The unit distribution is primarily derived through variable transformation, which can take various forms: , , or

Table 1 shows

some of the differences between Beta, Kumaraswamy and MBUR distributions. Jones

(2009) [22] mentioned some of the differences

between Beta and Kumaraswamy.

As shown from the differences, the new MBUR distribution has one parameter but with that single parameter the pdf has shapes that are increasing, decreasing, unimodal and bathtub distributions like the two-parameters Beta and Kumaraswamy distributions. Therefore, the new MBUR is tractable and flexible to accommodate and fit a wide range of data shapes. The new MBUR has explicit closed form of the CDF and subsequently the quantile function enables the distribution to be used in the median based quantile regression models like the Kumaraswamy distribution. The MBUR has simple formula for moments especially the mean which makes it candidate for mean based regression models like the Beta distribution when the data does not show extreme skewness. This is in contrast to Kumaraswamy which does not have that simple formula for the mean hence the distribution is not a candidate for mean-based regression models.

Most of the previously mentioned unit distributions exhibit flexibility to fit wide range of data shapes, especially skewed data, but with more than one parameter and varying tractability. They differ considering the closeness of the CDF and subsequently the lack of special function in the definition of the quantile function. The simpler and the closer formula for the CDF and the quantile function is, the better the distribution is to suit for quantile regression models. The unit Lindley distribution, although it is one parameter unit distribution, the quantile function requires Lambert function evaluation which is a special function. Topp Loene distribution has PDF that does not express the bathtub appearance. The new (MBUR) offers a significant advantage due to its simplicity and parsimony, requiring the estimation of only one parameter. This distribution is versatile, as its probability density function (PDF) can exhibit a variety of shapes, including increasing, decreasing, unimodal, and bathtub configurations. Additionally, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) has a straightforward, closed-form expression, which means that its quantile function does not necessitate the use of complex special functions. This simplicity in modeling enhances usability, making MBUR a valuable contribution to the family of unit distributions. This is particularly important considering the absence of a consensus on the most suitable distribution for datasets that display skewness. This paper is organized into the following sections. Methods are discussed in Section 1, where the author will explain the methodology for obtaining the new distribution, and in Section 2 where the author will elaborate on its probability density function (PDF), cumulative distribution function (CDF), survival function, hazard function, reversed hazard function, and quantile function. Results are evaluated in Section 3 where the author will discuss methods of estimation, accompanied by a simulation study. Discussion is expounded in Section 4 where the author will explore real data analysis along with an elucidation. Matlab 2014R was used in all calculations. Finally, Conclusions are explicated in section 5 with illumination on suggestions for future works.

Methods: Section 1:

Derivation of the MBUR Distribution:

By utilizing the PDF of the median order statistics for a sample size of n=3, the author derives a new distribution based on a Rayleigh distribution as the parent distribution, as illustrated below. Equation (1.A) defines the PDF of order statistics:

For a sample size n=3, to calculate the median order statistics, replace n=3 and i=2 in equation (1.A) to obtain (1.B):

substitute the PDF and CDF of Rayleigh distribution as a parent distribution in equation (1). Equation (2) defines both the PDF and CDF of the random variable w distributed as Rayleigh distribution. This yields a new distribution called Median-Based Rayleigh (MBR) distribution with PDF shown in equation (3).

Applying the following transformation on equation (3) to obtain the new unit distribution:

take the log on both sides:

take square root of both sides :

take

the Jacobian:

Replace the absolute value of the Jacobian and the above transformation in equation (3) to derive the new Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) Distribution shown in equation (4).

After some algebraic manipulations, the PDF of the MBUR is shown is equation (5).

Discussion: Section 4: Some Real Data Analysis:

The data sets are sourced from the OECD, or Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. It provides information on the economy, social events, education, health, labor, and the environment in the member countries. Matlab 2014 R was used for analysis where the mle function utilizes the derivative free Nelder-Mead algorithm for optimization.

https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI .

First data: (Dwelling Without Basic Facilities), see

Table 7. These observations assess the percentage of homes in the affected countries that lack essential utilities such as indoor plumbing, central heating, and clean drinking water supplies.

Second data: (Quality of Support Network), see

Table 8. This dataset examines the extent to which individuals can rely on sources of support, such as family, friends, or community members, during times of need and distress. It is presented as the percentage of individuals who have found social support in times of crisis.

Third data: (Educational Attainment), see

Table 9. The observations measure the percentage of the OECD population that has completed their high-level education, such as high school or an equivalent degree.

Fourth data: (Flood Data), see

Table 10. These are 20 observations regarding the maximum flood level of the Susquehanna River at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. [

24].

Fifth data: (Time between Failures of Secondary Reactor Pumps), [

21] see

Table 11.

The analysis of the above data sets aims to determine how these sets align with the following distributions: Beta, Topp Leone, Unit Lindely, Kumaraswamy. The fitting of these data sets will be compared to the fitting of the new MBUR distribution. The tools used for this comparison include the following metrics: LL(log-likelihood), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), corrected AIC (CAIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQIC). Additionally, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test will be conducted. The test's results will include its value, along with the outcome of the null hypothesis (H0), which assumes that the data set follows the tested distribution; if this assumption is not met, the null hypothesis will be rejected. The P-value for the test will also be recorded. Furthermore, the Cramér-von Mises test and the Anderson-Darling test will be performed, with their respective values reported. Figures depicting the empirical cumulative distribution function (eCDF) and the theoretical cumulative distribution functions (CDF) of the five distributions will be illustrated, each in its place. Finally, the values of the estimated parameters, along with their estimated variances and standard errors, will be reported. The competitors’ distributions are:

- 2-

Kumaraswamy Distribution:

- 3-

Median Based Unit Rayleigh:

- 4-

Topp-Leone Distribution:

- 5-

Unit-Lindley:

Comparison tools are: (k) is the number of parameter, (n) is the number of observations.

Total time on Test (TTT) can be calculated with the following approaches.

First Approach (Empirical approach):

Second Approach (theoretical approach): scaled TTT transform curve using survival function and the theoretical quantile.

Where the theoretical quantile function is:

Both graphs are provided for each data set.

The rationale for selecting these datasets is the characteristics they exhibit. Descriptive statistics definitively reveal empirical skewness and kurtosis from the data, compelling the author to choose the most appropriate competitor distributions to accommodate these findings.

4.1. Analysis of the First Data Set

See supplementary materials (section 3)

4.2. Analysis of the Second Data Set

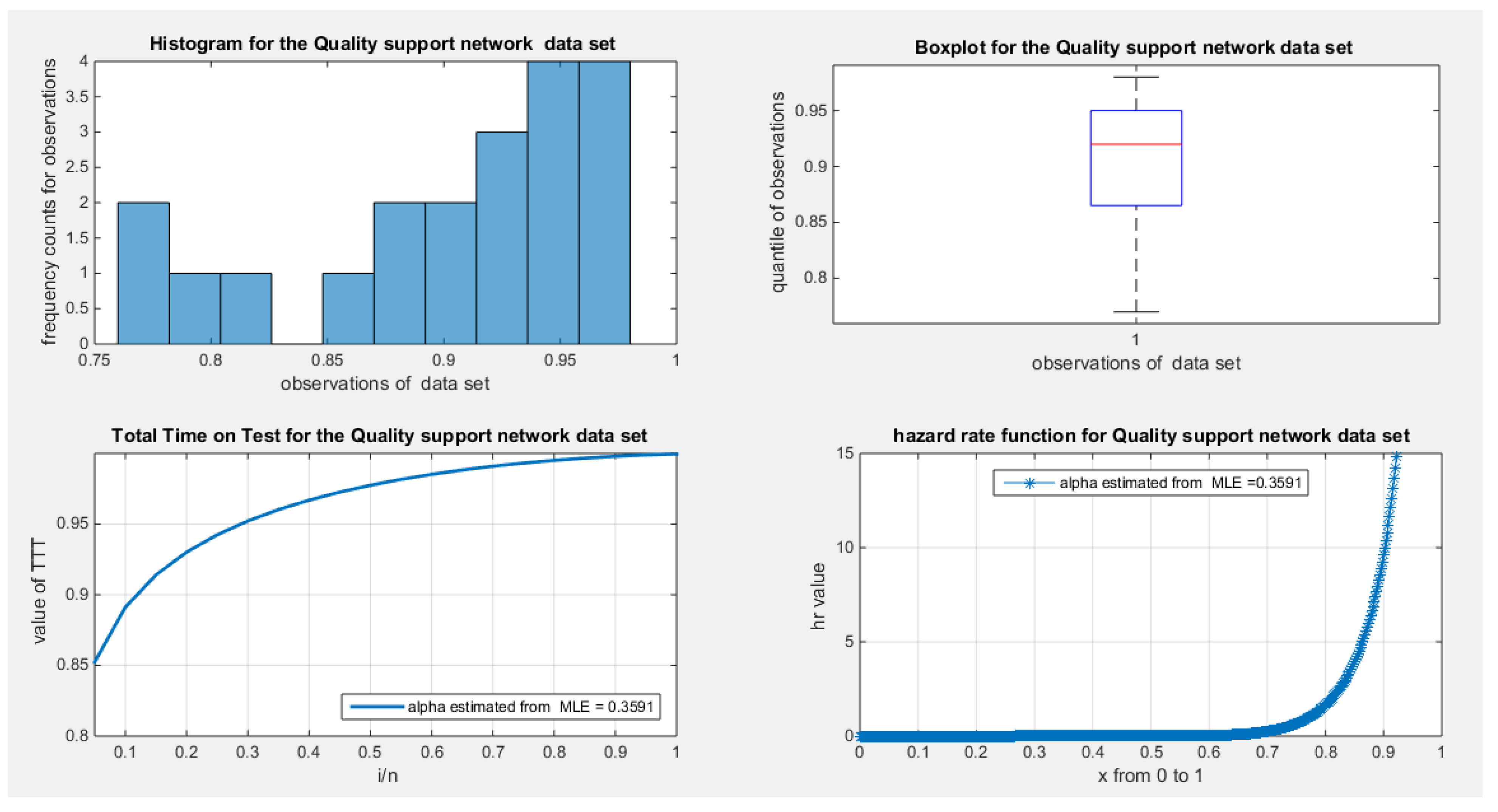

The data demonstrates a left skewness and a negative excess kurtosis, indicating a platykurtic shape. This is supported by the histogram and box plot shown in

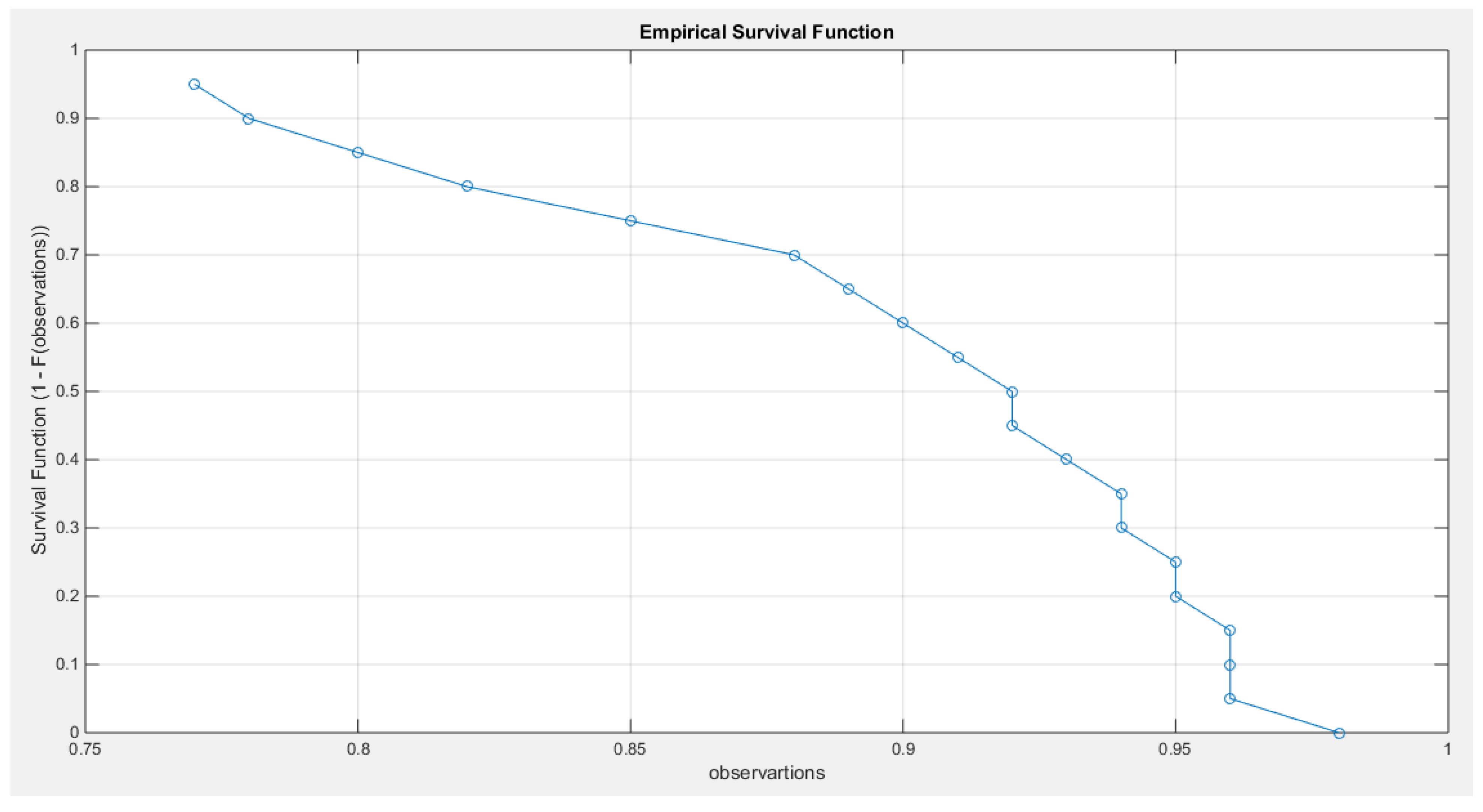

Figure 18. Plotting the empirical survival function reveals a rapid decay, suggesting a light tail, as illustrated in

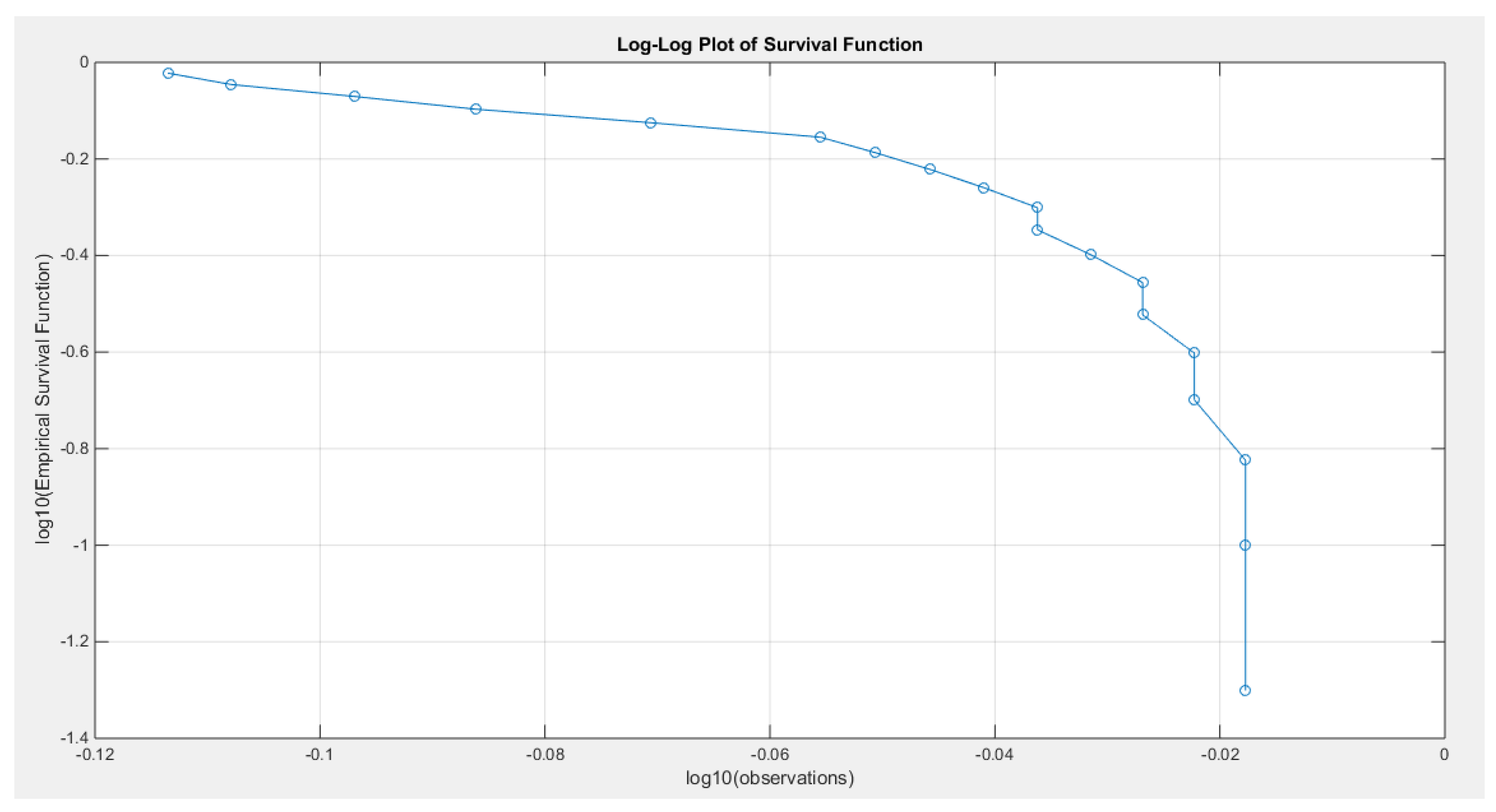

Figure 19. This observation is further reinforced by the log-log plot in

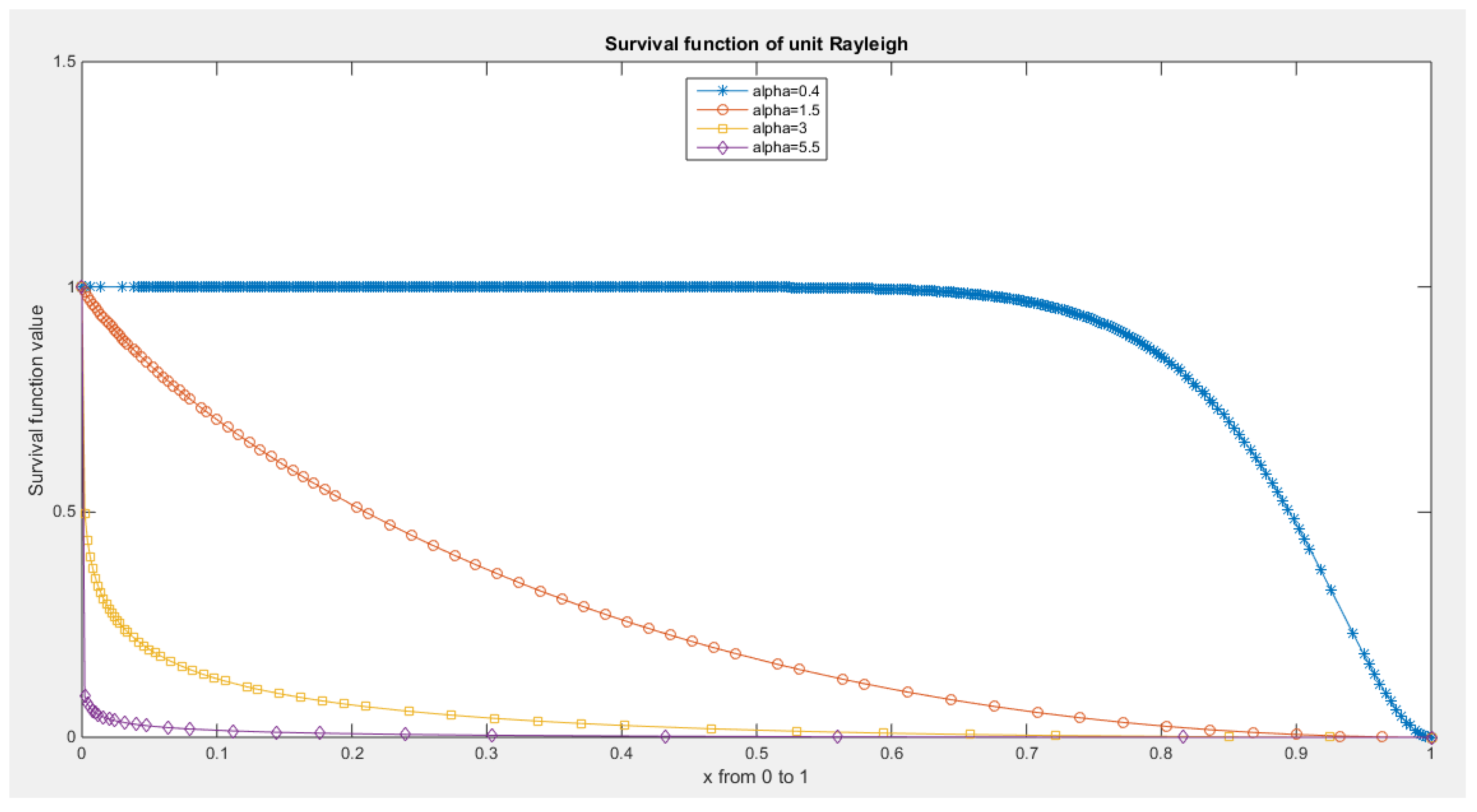

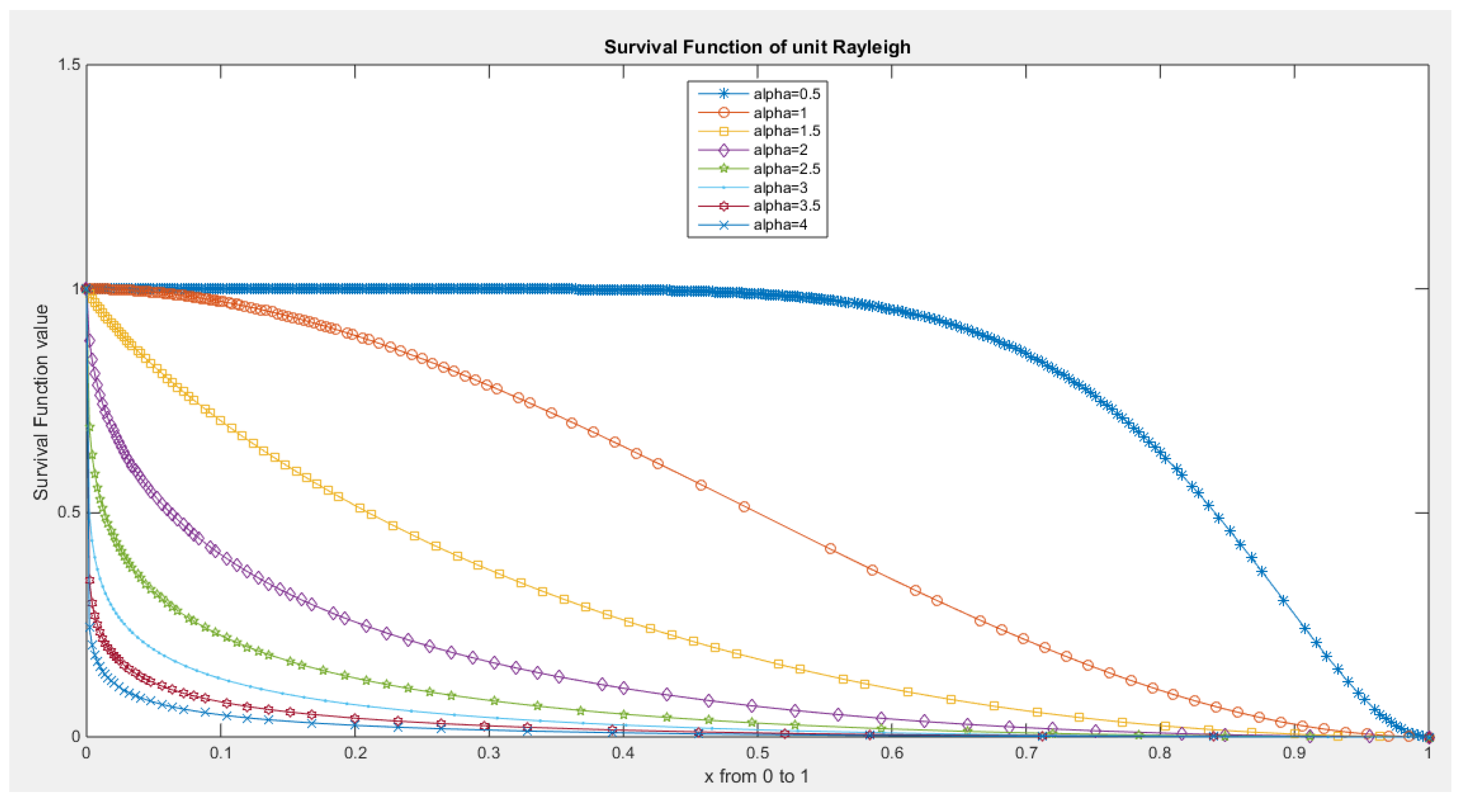

Figure 20. When the author plots the logarithm of the observations against the logarithm of the empirical survival function, the author sees a concave curve, which indicates faster decay and supports the concept of a light tail. Additionally, a quantile analysis was conducted by comparing the empirical 1st, 5th, and 10th quantiles with the corresponding theoretical quantiles from the standard uniform distribution. The findings show a light tail: specifically, (0.7700 < 0.7721), (0.7750 < 0.7805), and (0.7900 < 0.7910). Fitting the MBUR model to the data produced an estimated alpha value of 0.3591, which is less than 1. This is consistent with the empirical survival function depicted in

Figure 19, which bears similarity to the survival function in

Figure 6, where alpha is also less than 1.

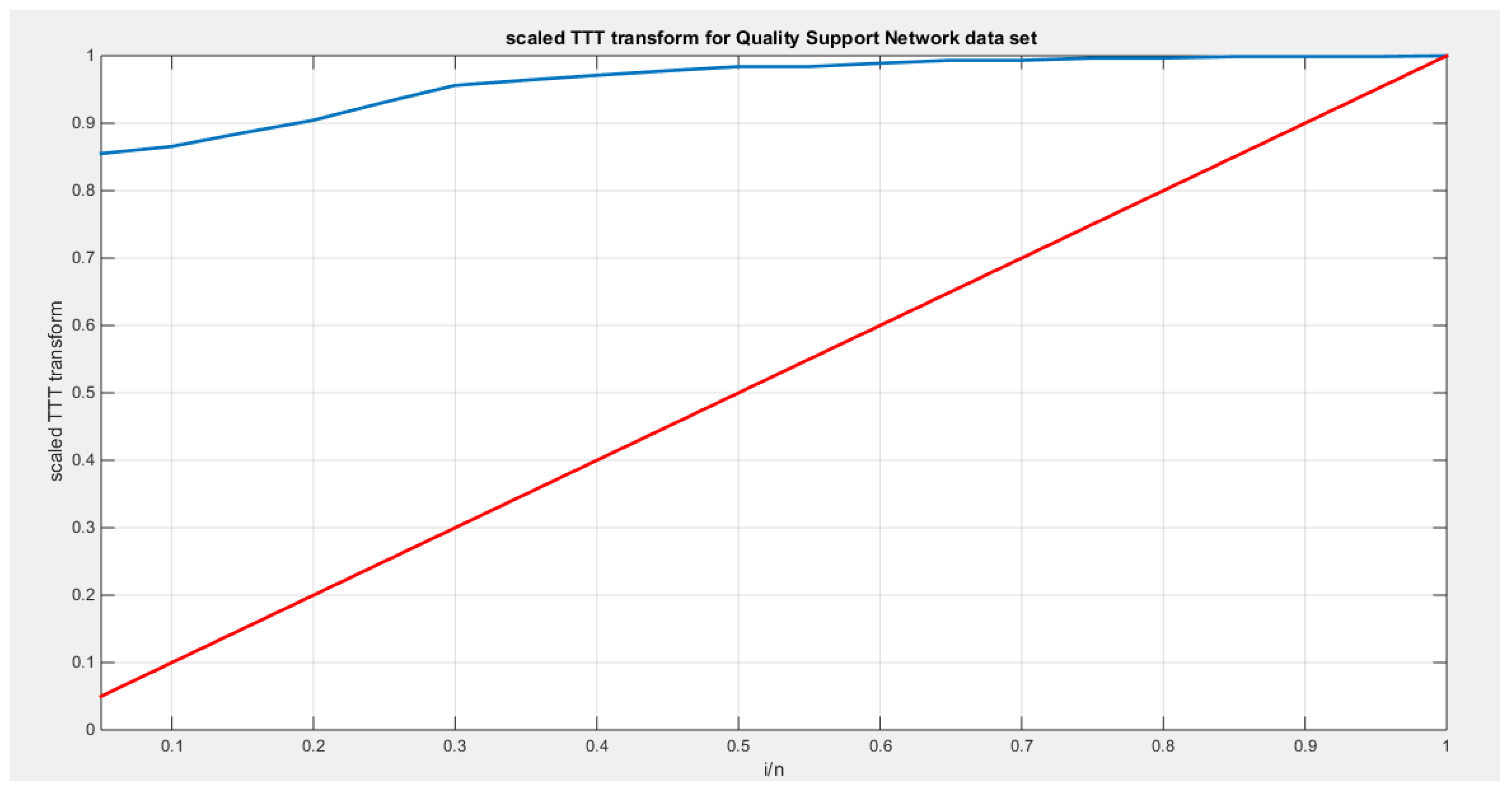

After fitting the MBUR distribution to the data, the scaled TTT plot reveals a concave shape, indicating an increased failure rate. This pattern is evident in the shape of the hazard rate function.

Figure 18 illustrates this concavity through the theoretical scaled TTT plot, which supports the increase in the hazard rate. Similarly,

Figure 21 displays the empirical scaled TTT plot, also confirming this increase in the hazard rate.

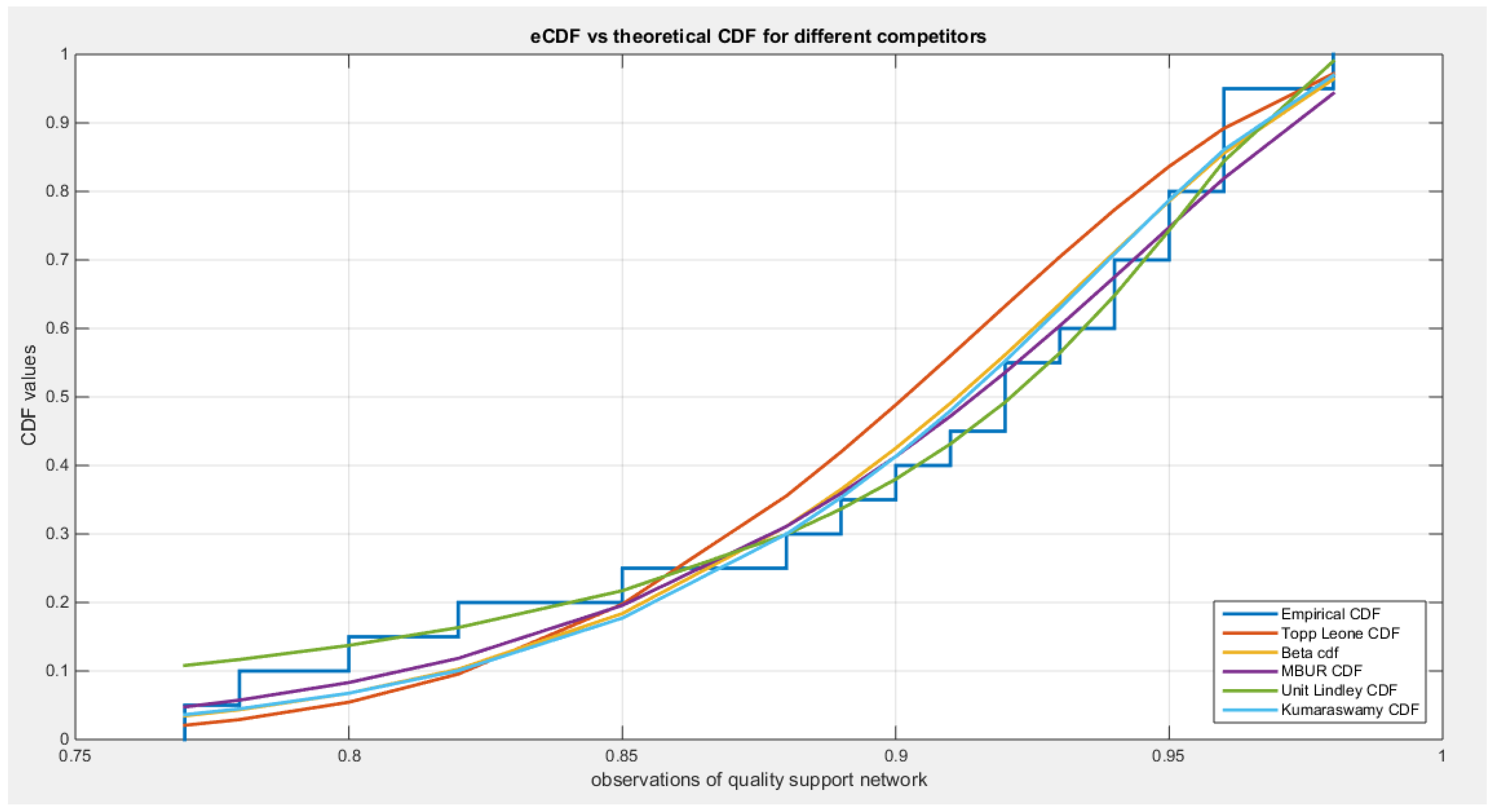

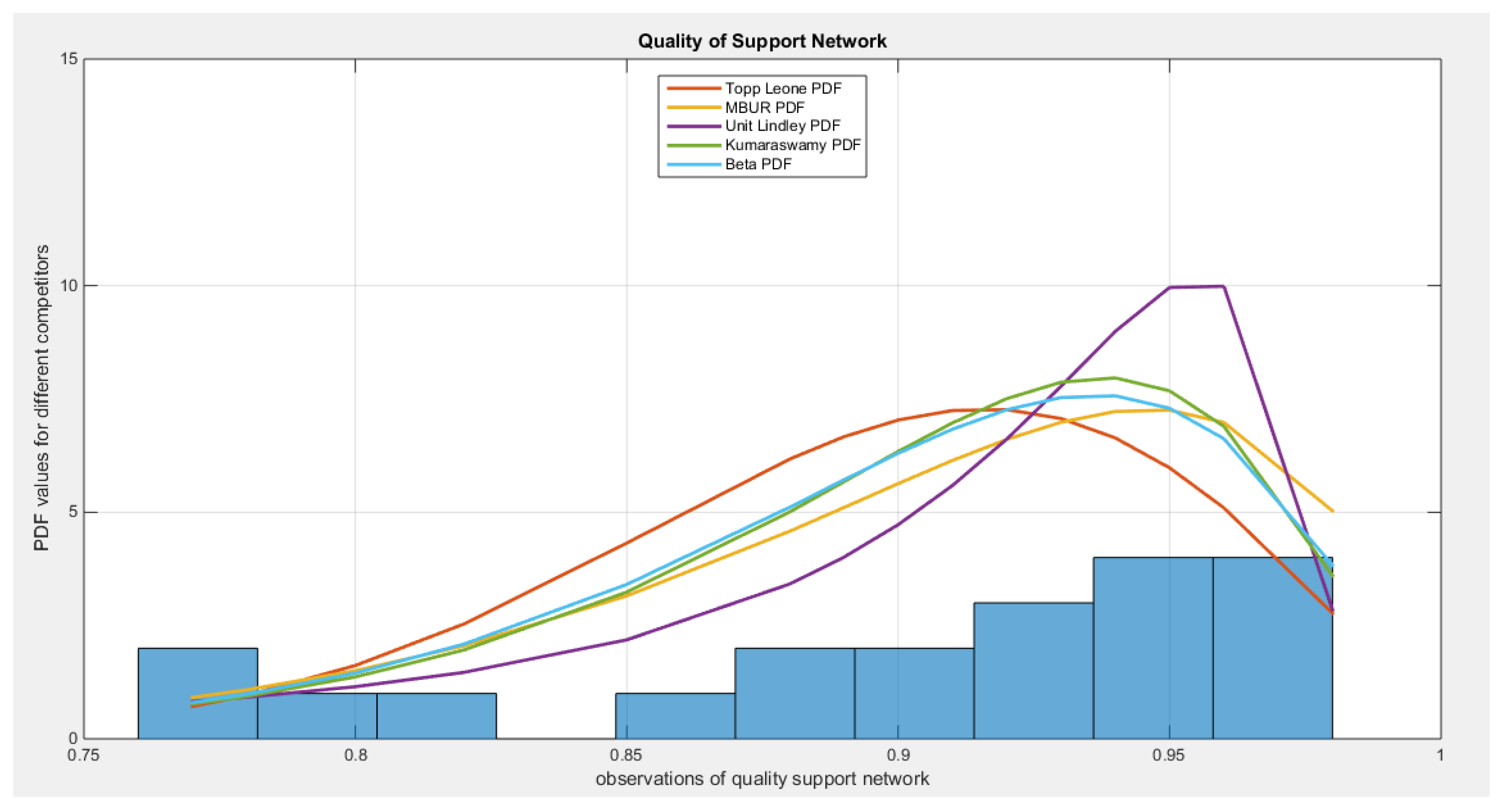

Out of the five distributions analyzed, all successfully fitted the data. However, the MBUR distribution emerged as the most effective model. This was evidenced by its superior validation indices compared to the other distributions, as illustrated in in

Table 13.

The P-values for the estimators of alpha and beta parameters of the Beta distribution and Kumaraswamy distributions are significant .P-values for the estimators of alpha of the MBUR distribution is significant , for the estimators of theta of the Topp-Leone distribution is significant , and for the estimators of theta of the Unit Lindley distribution is significant .

The KS test effectively measures the maximum distance between the empirical cumulative distribution function (eCDF) and the theoretical cumulative distribution function (CDF). Its straightforward nature and broad applicability make it a valuable tool, as it imposes no assumptions on the distribution parameters. However, it is less sensitive to deviations in the tails of the distribution, as it primarily focuses on the center. In contrast, the AD test excels in detecting deviations in the tails and is particularly suited for distributions with extreme values. Despite this advantage, the necessity for calculating critical values for newly emerging distributions can hinder its application. The CVM test takes a different approach by measuring the overall distance between the eCDF and the theoretical CDF, treating all parts of the distribution equally. This means it effectively balances sensitivity to deviations across the tail and the center, making it a compelling choice in many scenarios. Given the complexity of skewed data, it is crucial to utilize more than one test. Each test highlights specific characteristics of the data, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the fitting distribution. When combined with visual aids, such as QQ plots and PP plots, this methodology significantly enhances the analysis, driving more informed decisions. Therefore, when assessing the goodness of fit of a distribution, it is important to consider the results of the three tests mentioned above, along with the information obtained from the QQ plot and PP plot. Key aspects to observe include how closely the points align with the diagonal, the degree of deviation from the diagonal, and the percentage of observations that deviate from it.

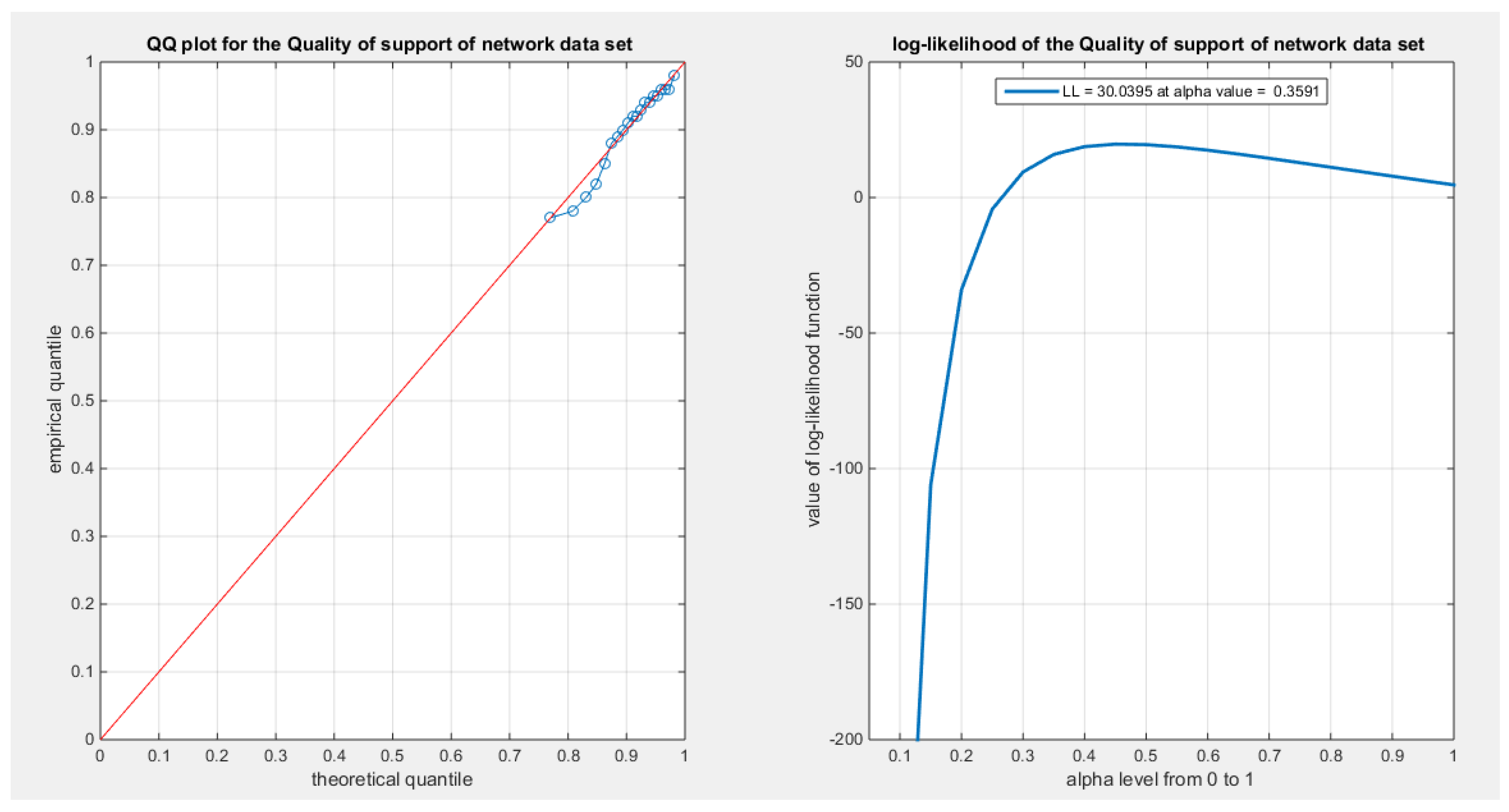

The MBUR model fits the second dataset, as evidenced by its failure to reject the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. The QQ plot shows almost perfect alignment with the diagonal, with only slight deviations at the lower end of the distribution. Since the KS test is less sensitive to deviations in the tail of the distribution, the author also conducted the Anderson-Darling (AD) test and the Crámer-von Mises (CVM) test using Monte Carlo simulations.

The observed value of the AD test statistic was 0.3184, while the critical values obtained from the simulations were 2.4433 (95th quantile) and 3.0146 (97.5th quantile). Since the observed AD value is less than the critical values from the simulation, the author fails to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that MBUR could be a generating process for the data. The approximate p-value for this test was 0.929, which is greater than 0.025, further confirming that MBUR fits the second dataset.Additionally, the CVM test from the observed data revealed a value of 0.0407. The CVM test conducted using Monte Carlo simulations yielded critical values of 0.4578 (95th quantile) and 0.5781 (97.5th quantile). Again, since the observed CVM value is less than the critical values, the author fails to reject the null hypothesis that the data was generated by MBUR. The approximate p-value for this test is 0.936, which is also greater than 0.025, supporting the conclusion that MBUR fits the second dataset. Overall, combining various goodness-of-fit statistics with visualizations enhances the results of the analysis. This is shown in the Table13 and

Figure 22,

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25

According to the AIC, AIC corrected, BIC, and Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion (HQIC), the MBUR distribution is the best fit for the data, followed by the Unit Lindley, Topp-Leone, Kumaraswamy, and finally the Beta distribution. This conclusion is based on the MBUR having the lowest values of these indices (or the largest negative values). However, it is worth noting that the MBUR has the second lowest value for the Anderson-Darling (AD) test, Cramer-von Mises (CVM) test, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test, coming in just after the Unit Lindley.

Figure 22 illustrates that the theoretical cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) for the various distributions closely follow the empirical CDF. Meanwhile,

Figure 23 presents the fitted probability density functions (PDFs). An important observation from this analysis is that the metric values for the MBUR distribution are comparable to those of the Topp-Leone and Unit Lindley distributions, indicating that the new MBUR distribution has performed well in fitting the data.

Figure 24 shows the quantile-quantile (QQ) plot for the fitted MBUR distribution, which exhibits nearly perfect alignment along the diagonal, with only slight deviations at the lower tail. The log-likelihood function is maximized at an alpha level of 0.3519. Finally,

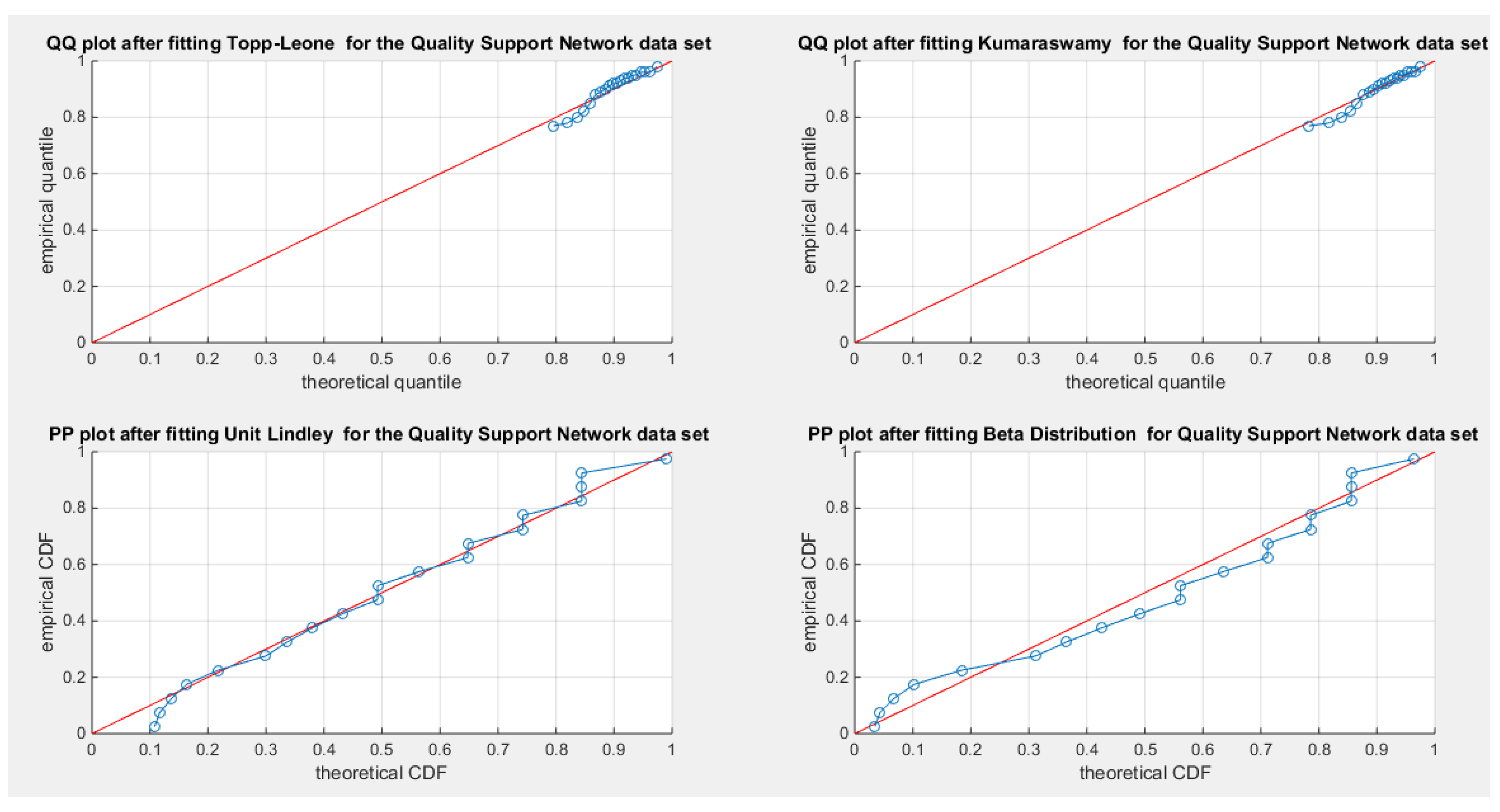

Figure 25 provides the QQ plot and probability-probability (PP) plot for the other distributions, which also demonstrate near-perfect alignment along the diagonal.

4.3. Analysis of the Third Data Set

See supplementary materials (section 3)

4.4. Analysis of the Fourth Data Set

See supplementary materials (section 3)

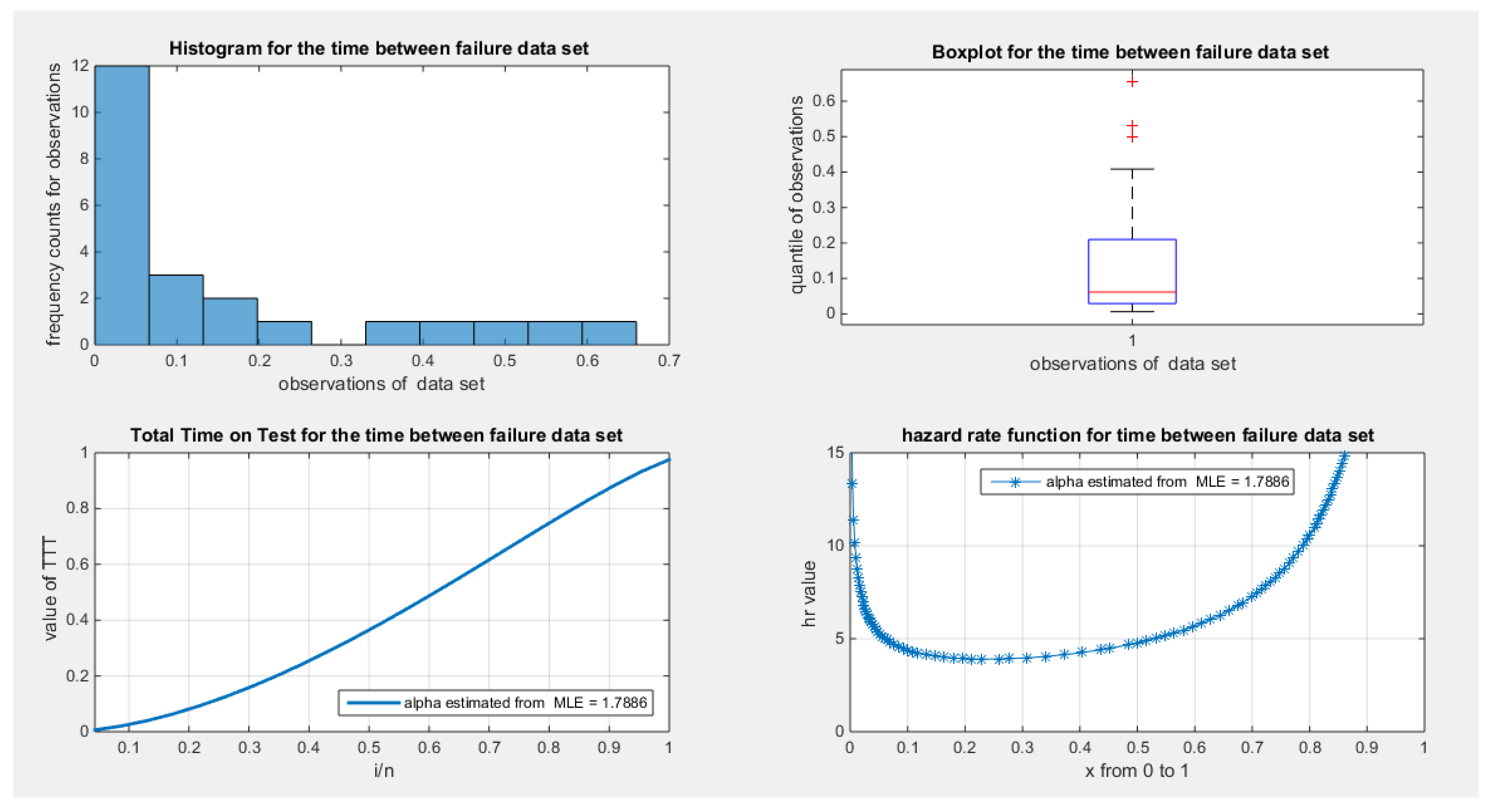

4.5. Analysis of the Fifth Data Set

The data shows a right skewness and a positive excess kurtosis (leptokurtic shape), which is supported by the histogram and box plot in

Figure 26. When plotting the empirical survival function, the author observes a slower decay, indicating heavier tails, as illustrated in

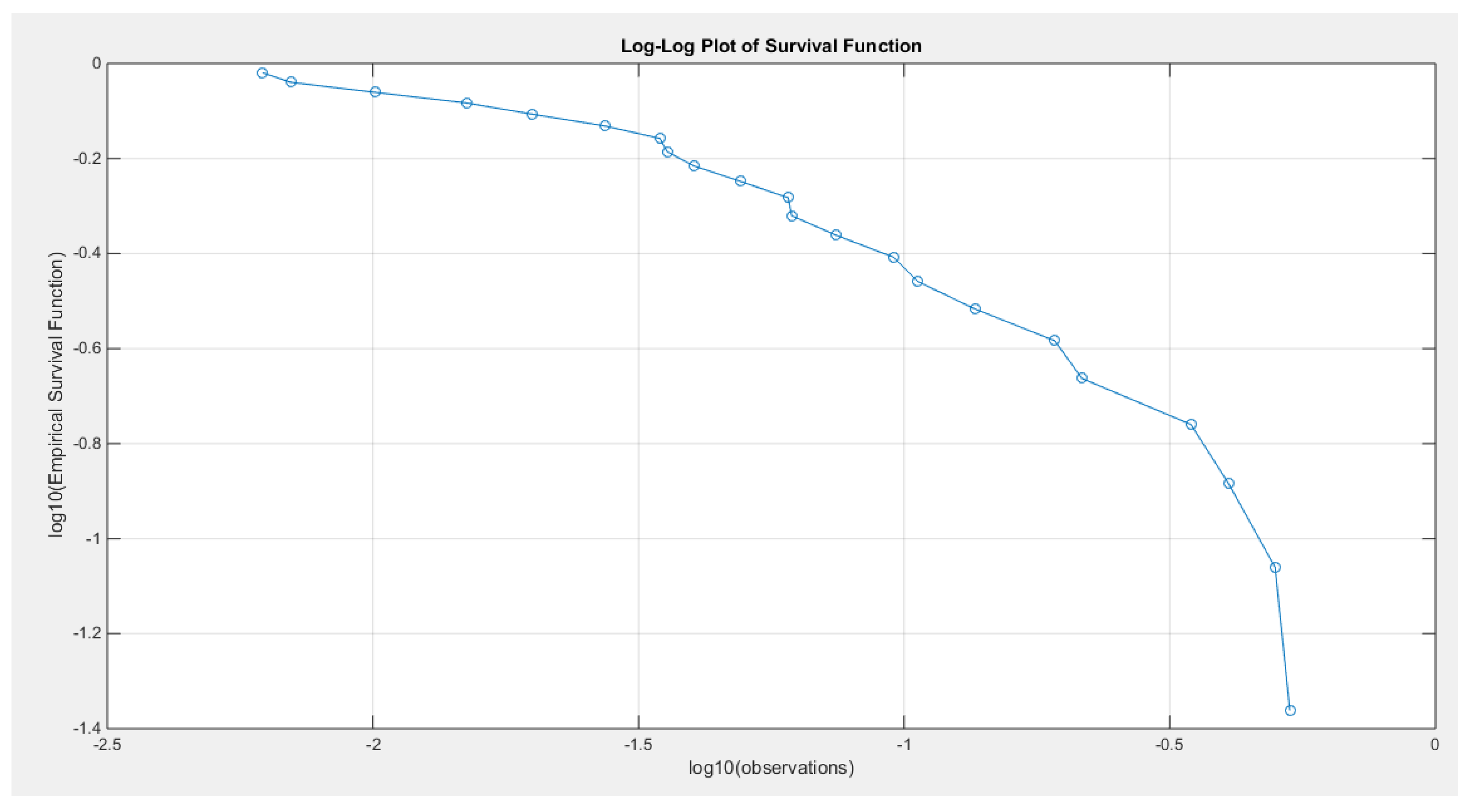

Figure 27. This observation is further supported by the log-log plot in

Figure 28. When the author plots the logarithm of the observations against the logarithm of the empirical survival function, the resulting straight line indicates a slower decay, which is characteristic of heavier tails. In quantile analysis, the author compared the empirical 99th quantile (0.6560) with the 99th theoretical quantile of a standard uniform distribution (0.6494). This comparison reveals that the empirical value is greater than the theoretical one (0.6560 > 0.6494), suggesting a heavier tail. Additionally, when fitting the MBUR model to the data, the author obtained an estimated alpha value of 1.7886, which is greater than 1. This is consistent with the empirical survival function shown in

Figure 27, which is similar to the survival function depicted in

Figure 6, where alpha is also greater than 1.

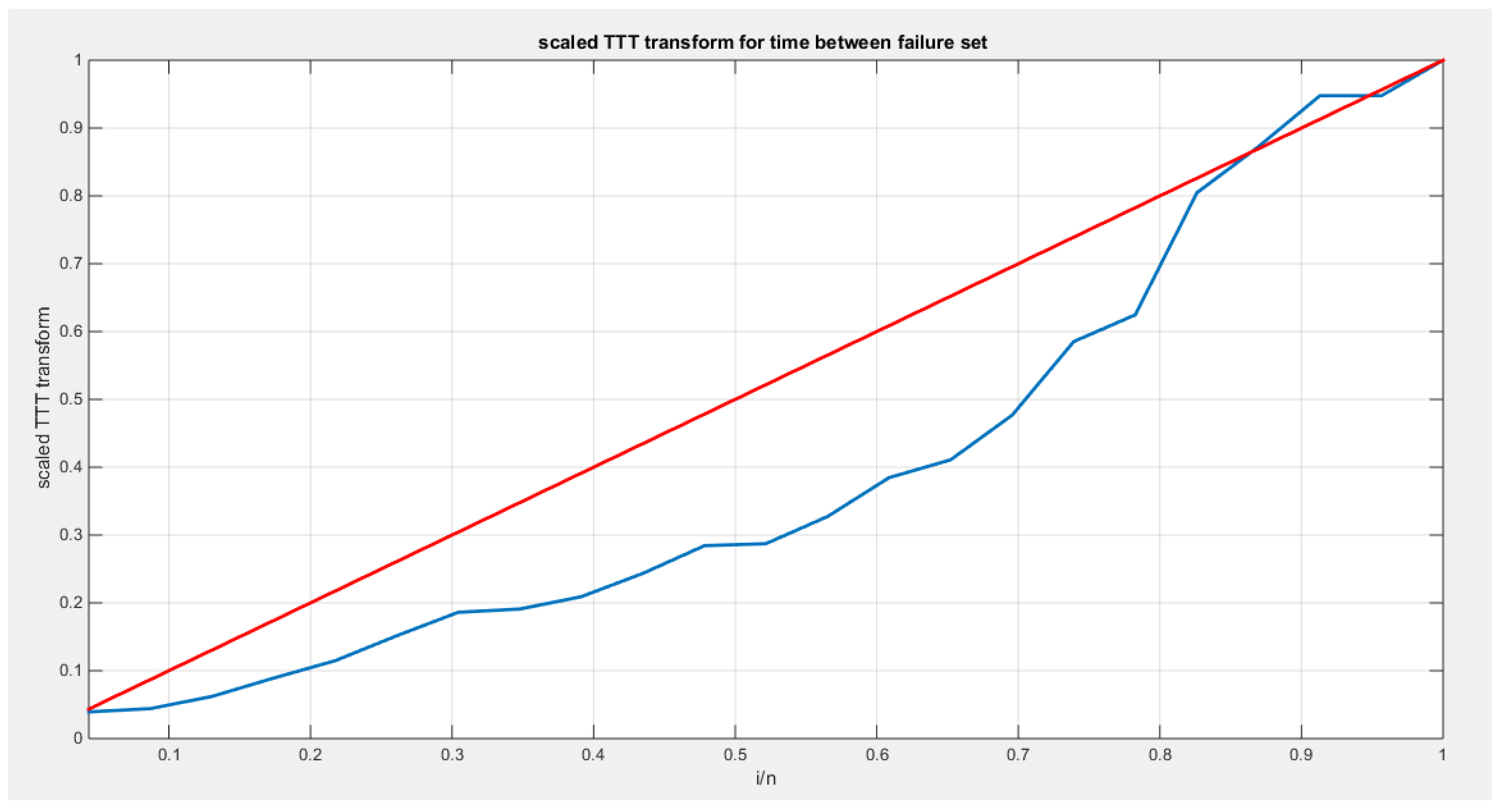

The second approach illustrated in

Figure 26 for calculating and graphing the TTT plot does not exhibit the typical convexity followed by concavity that characterizes the bathtub shape seen in the hazard rate function. In contrast,

Figure 29, which employs the first approach for calculation and graphing, more accurately represents this relationship.

The MBUR distribution is the best fit for the time between failures data among the five distributions evaluated, followed by Kumaraswamy, Beta, and Topp-Leone. The Unit Lindley distribution, however, did not fit the data well. The MBUR has the most significant negative values for AIC, AIC corrected, BIC, and HQIC. Despite this, it is the second distribution to have the smallest values for the AD test and the CVM test.

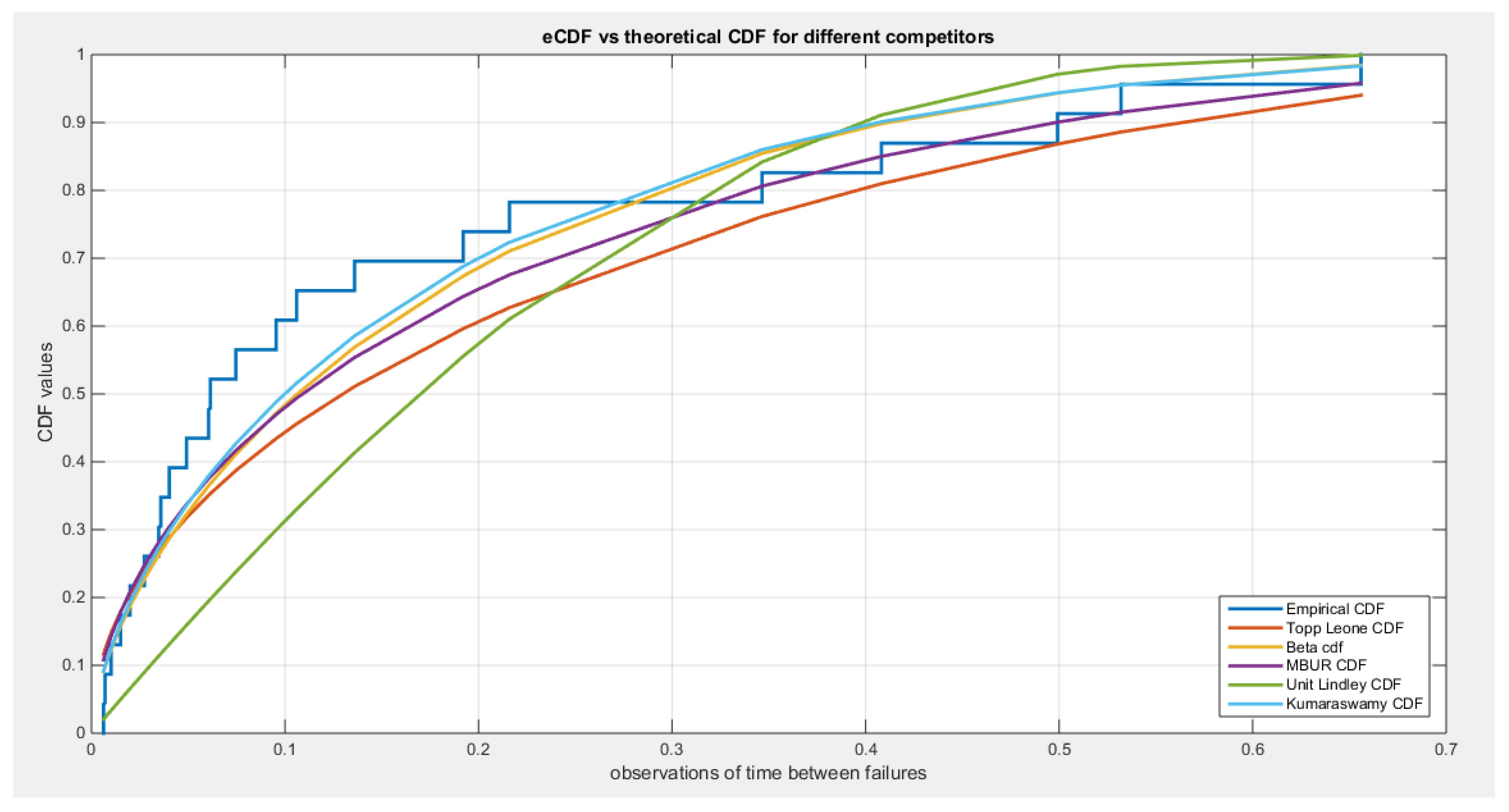

Figure 30 illustrates that the eCDF closely follows the theoretical CDF for the fitted distributions, particularly at the tails, though there is a slight deviation at the center.

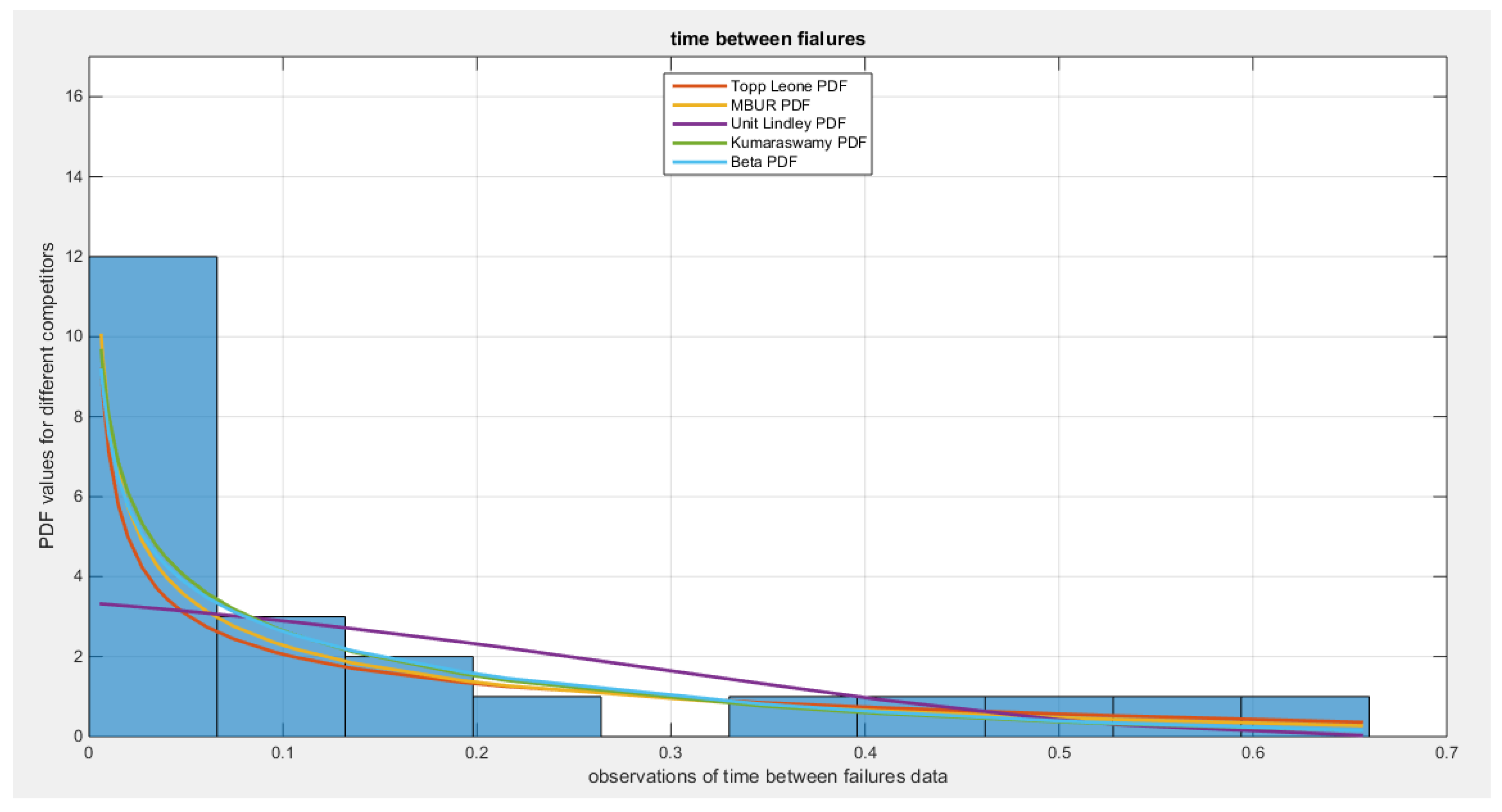

Figure 31 displays the PDFs for the various competing distributions. In

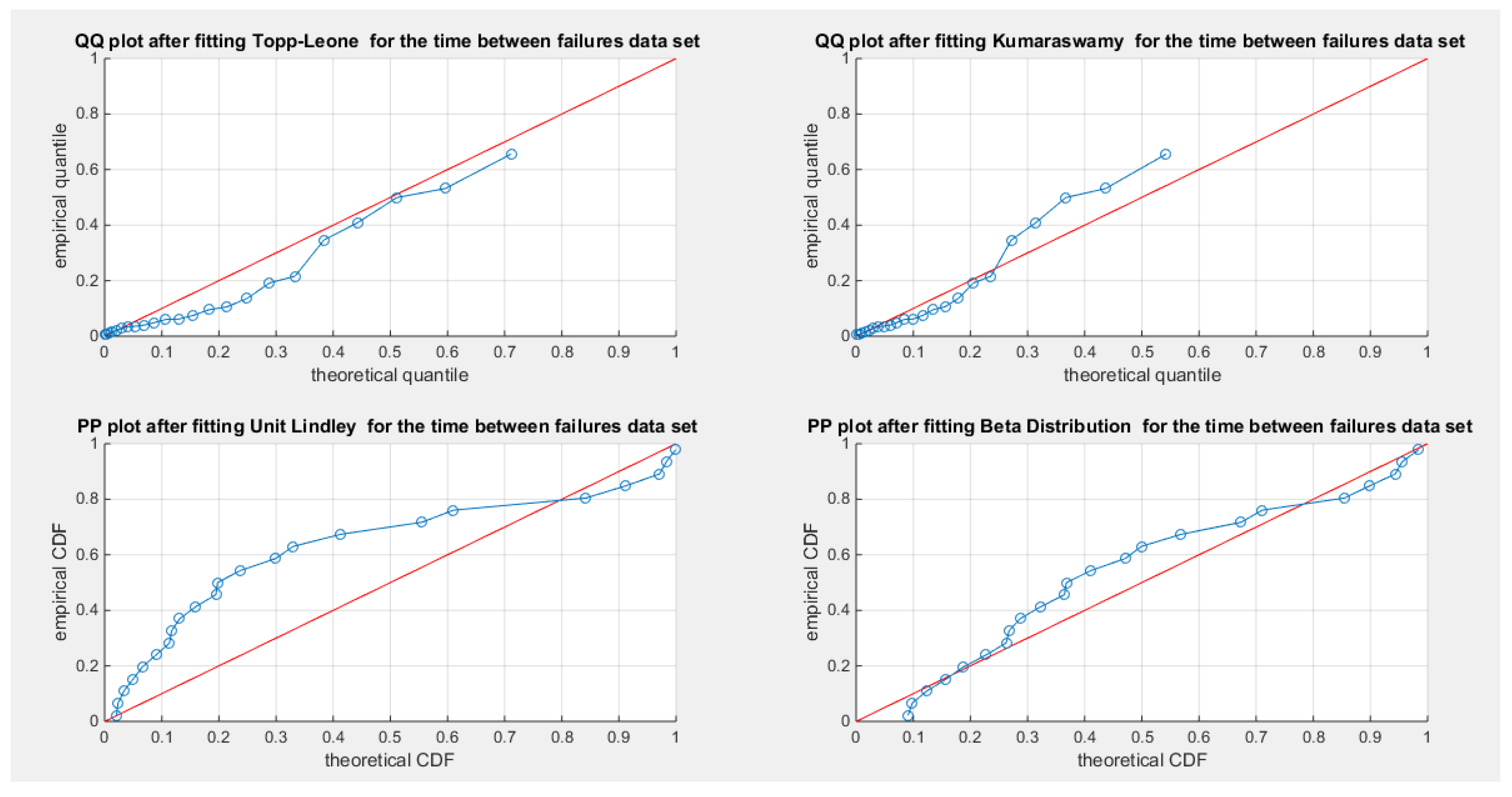

Figure 32, the QQ plot demonstrates good alignment with the diagonal after fitting the MBUR, with the maximum likelihood estimate achieved at an alpha level of 1.7886.

Figure 33 shows a generally close alignment with the diagonal line for the other fitted distributions, especially at the tails, with slight deviations at the center, indicating that these distributions capture the characteristics of the data well. The PP plot further illustrates that the Unit Lindley distribution does not align closely with the diagonal. The P-values for the estimators of alpha and beta parameters of the Beta distribution and Kumaraswamy distributions are significant

. P-value for the estimators of alpha of the MBUR distribution is significant

. P-value for the estimators of theta of the Topp-Leone distribution is significant

.

The MBUR model unequivocally fits the fifth dataset, as demonstrated by the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test, which successfully failed to reject the null hypothesis that the data adheres to the MBUR distribution. This conclusion is visually substantiated by the QQ plot, which shows a strong alignment along the diagonal, indicating a robust correspondence between the theoretical distribution and the empirical data, though minor deviations can be observed at the lower end. To address the potential limitations of the KS test—particularly its insensitivity to deviations in the distribution tails—the author conducted additional analyses using the AD test and the CVM test, both of which utilized Monte Carlo simulations for enhanced accuracy. The AD test produced a statistic of 0.6703. The critical values from the simulations for this test were clear: 2.6428 for the 95th quantile and 3.3935 for the 97.5th quantile. The value for 2.5th quantile is 0.2309. The observed AD statistic is significantly less than these critical values, compellingly leading the author to fail to reject the null hypothesis. This strongly indicates that the MBUR model can indeed act as a generating process for the observed data. The p-value corresponding to this test was a definitive 0.594, exceeding the conventional significance threshold of 0.025, thus firmly establishing MBUR as an appropriate fit for the fifth dataset. Likewise, the CVM test reinforced this conclusion with an observed statistic of 0.1253. Critical values derived from Monte Carlo simulations were found to be 0.4858 (95th quantile) and 0.6099 (97.5th quantile). The value for the 2.5th quantile is 0.03. As with the AD test, the observed CVM statistic fell below these critical thresholds, leading to a resolute failure to reject the null hypothesis that the data originated from the MBUR model. The approximate p-value for this test, calculated at 0.485, also exceeds the 0.025 significance level, decisively affirming that MBUR is an excellent fit for the dataset in question.

Integrating various goodness-of-fit statistics with effective visualizations significantly enhances the analysis results, leading to clearer insights and more informed decisions. This is shown in the Table15 and

Figure 30,

Figure 31,

Figure 32 and

Figure 33

When using AIC and BIC to compare distributions that fit specific data, both metrics aim to balance maximizing model fit, reflected in the highest negative values of log-likelihood, with minimizing model complexity, which is represented by the number of parameters in the model. This balance helps avoid overfitting, particularly in cases where a model may be too complex and have too many parameters. Such complex models can capture not only the true underlying structure of the data but also random noise, leading to poor generalization when new data is introduced.

The log-likelihood (LL) measures how well a model fits the data; higher LL values indicate a better fit. However, simply adding more parameters (k) tends to increase LL, even if those additional parameters are not meaningful. Therefore, AIC and BIC serve as trade-offs between model fit and complexity, addressing the challenge of balancing overfitting (too complex a model) and underfitting (too simple a model). To mitigate overfitting, AIC and BIC introduce penalties for complexity that are proportional to the number of parameters (k). The AIC penalty is a linear penalty of 2k, whereas the BIC penalty is k * ln(n), which increases with sample size.

AIC and BIC are used to select the best-fitting distribution among candidates. They depend on LL, meaning that the model which better captures the structure of the data will display more negative values for AIC and BIC. In cases where the data exhibits complex features such as skewness and heavy tails, a model with more parameters may yield more negative AIC and BIC values. Conversely, if the data is simpler (e.g., symmetric with a small sample size), more straightforward models are often preferred.

The more negative the values of AIC and BIC, the better the model. By themselves, these values are meaningless, but they are useful for comparing models. A difference greater than 10 between two models suggests that the model with the more negative value is significantly better. AIC is typically used when the goal is prediction and the dataset is small, while BIC is preferred when identifying the true model is critical and the dataset is large, due to differing penalty structures.

Regarding the datasets discussed in this paper, they exhibit skewness and kurtosis, indicating their complexity. The sizes of these datasets range between 20 and 36, making them small to moderate in size. The new MBUR distribution can effectively fit all the data using just one parameter, resulting in a relatively small penalty from AIC and BIC. This represents an advantage of the MBUR distribution over other distributions, such as the beta and Kumaraswamy distributions, which require multiple parameters.

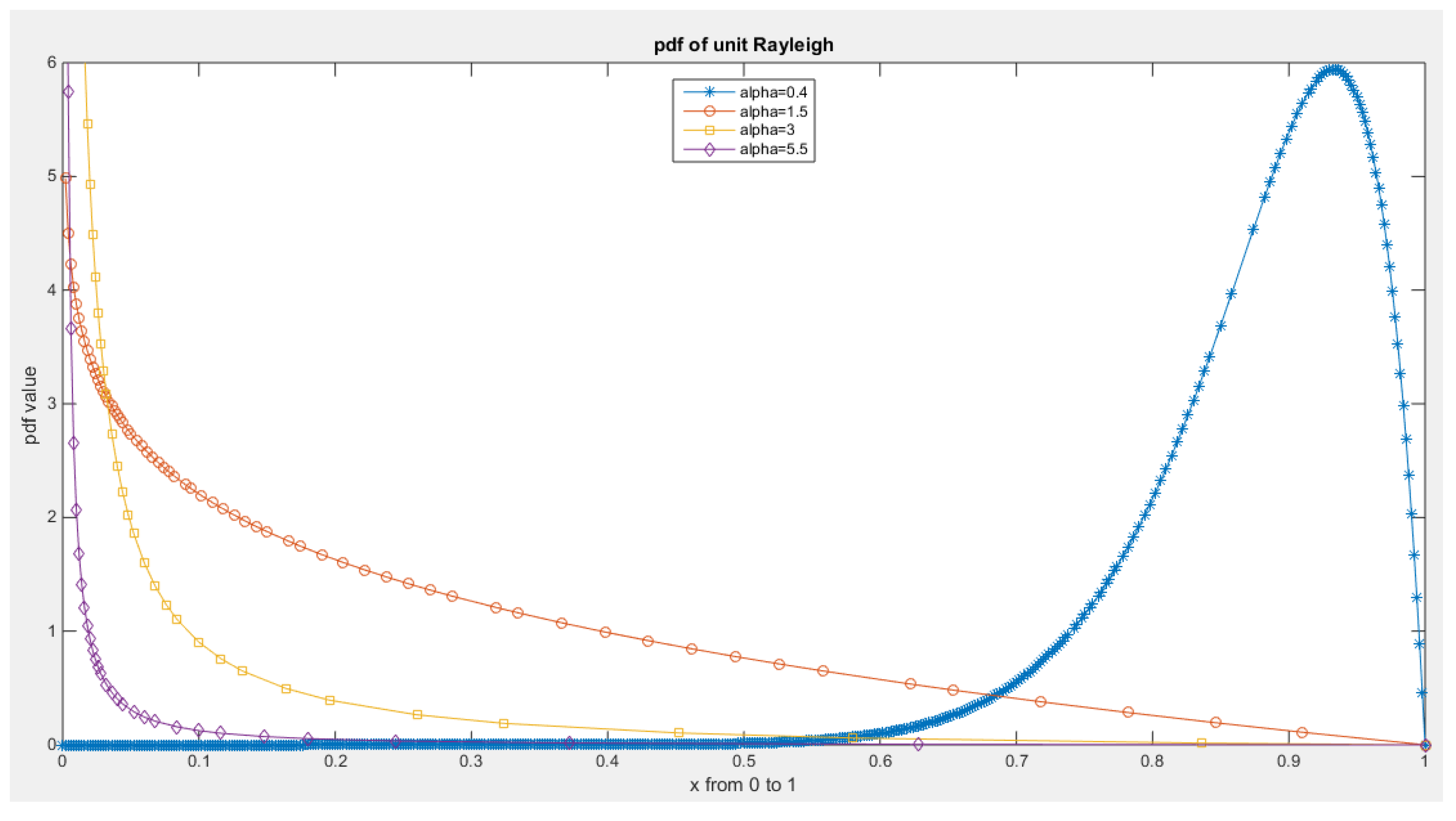

Figure 1.

PDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) distribution.

Figure 1.

PDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) distribution.

Figure 2.

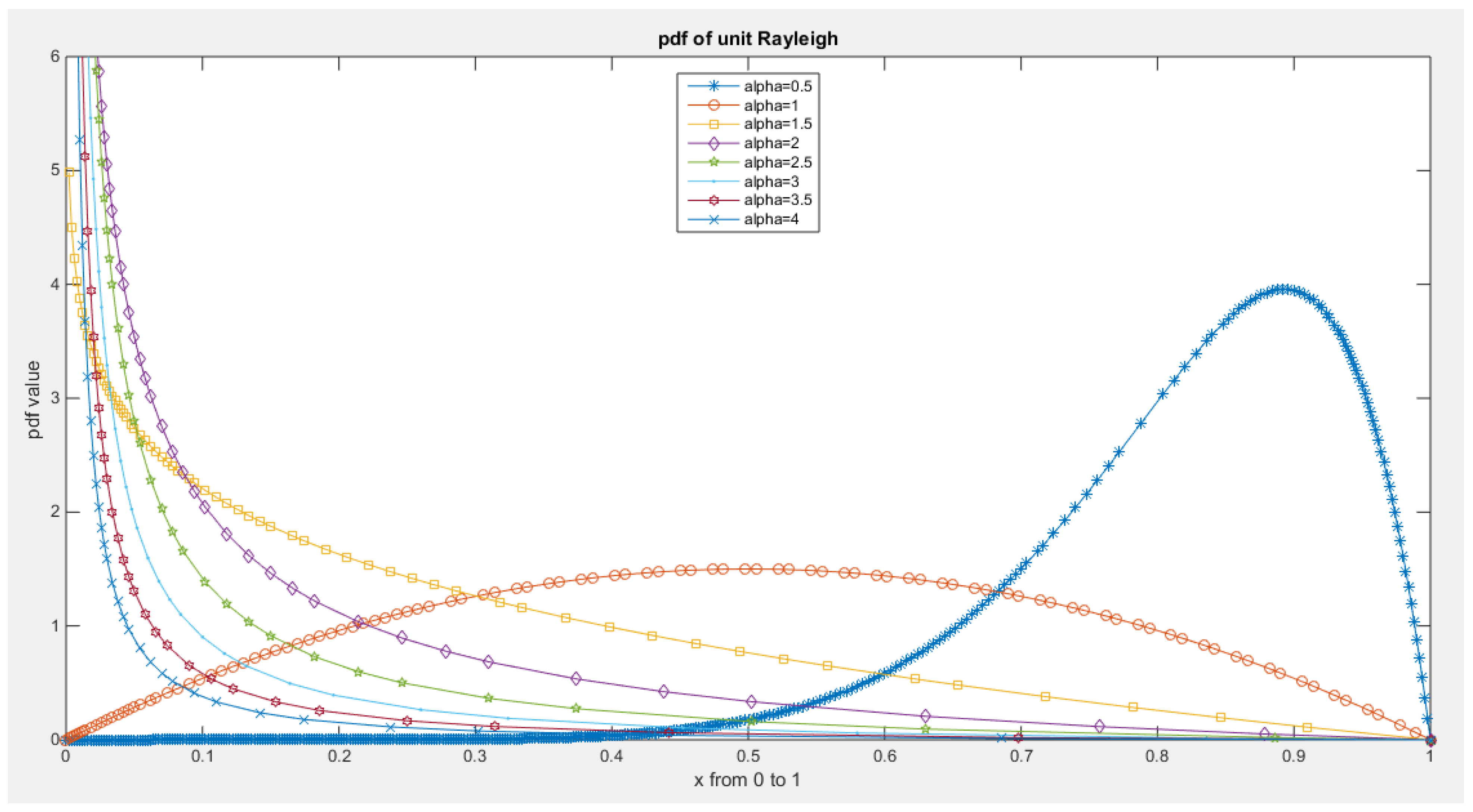

PDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) distribution.

Figure 2.

PDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) distribution.

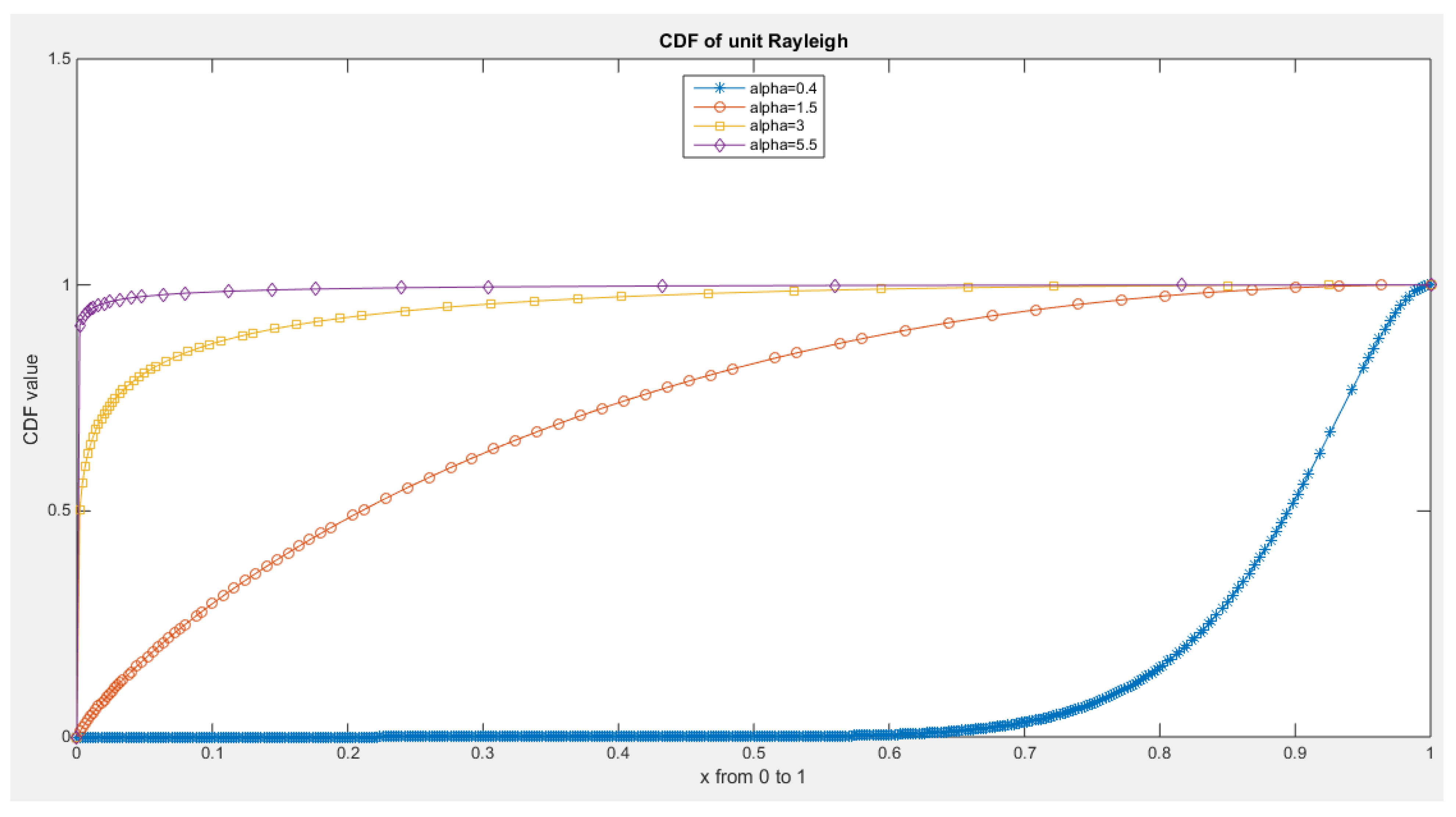

Figure 3.

CDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) Distribution.

Figure 3.

CDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) Distribution.

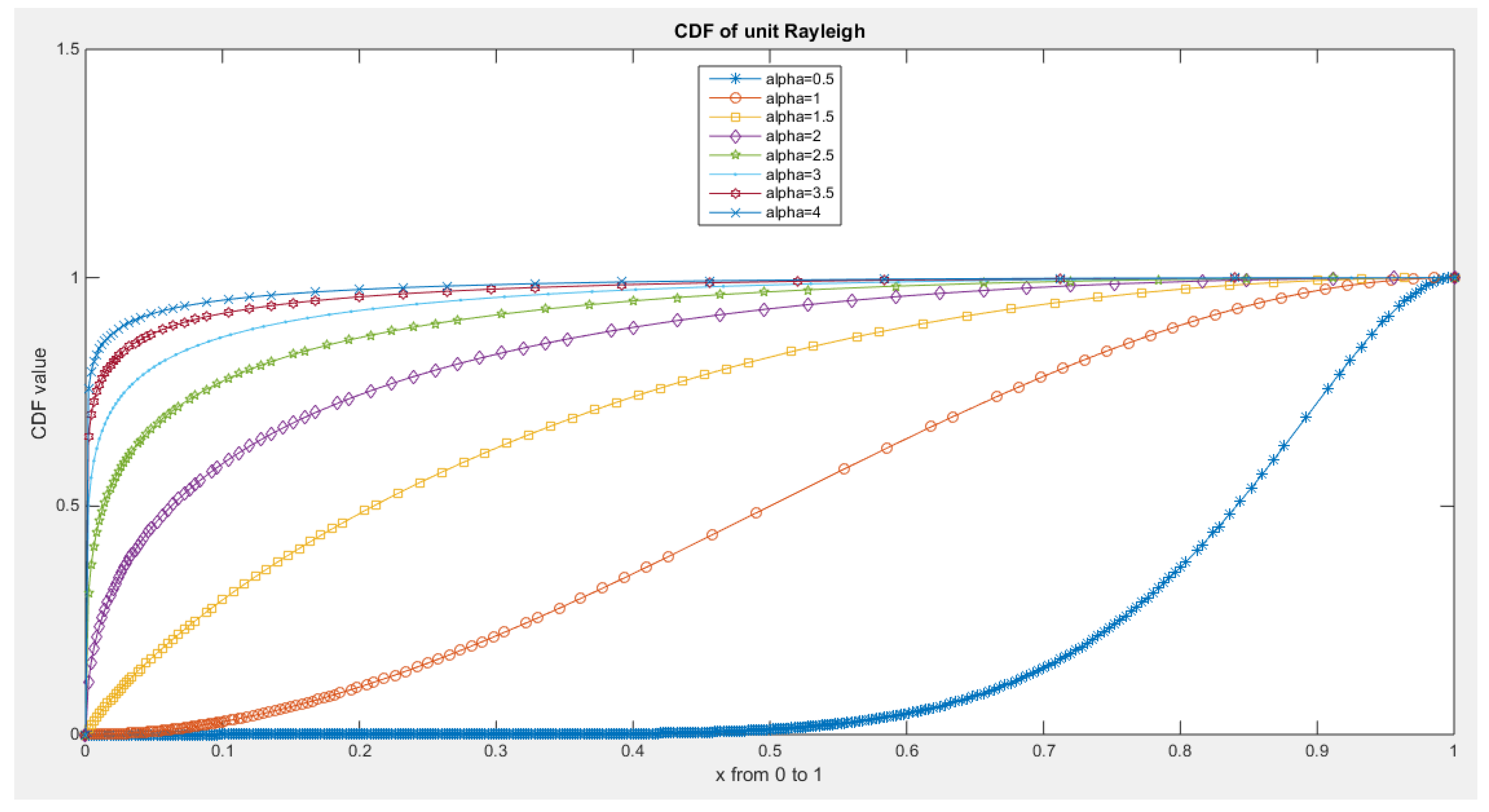

Figure 4.

CDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) Distribution.

Figure 4.

CDF of Median Based Unit Rayleigh (MBUR) Distribution.

Figure 5.

Survival function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 5.

Survival function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 6.

Survival function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 6.

Survival function of MBUR Distribution.

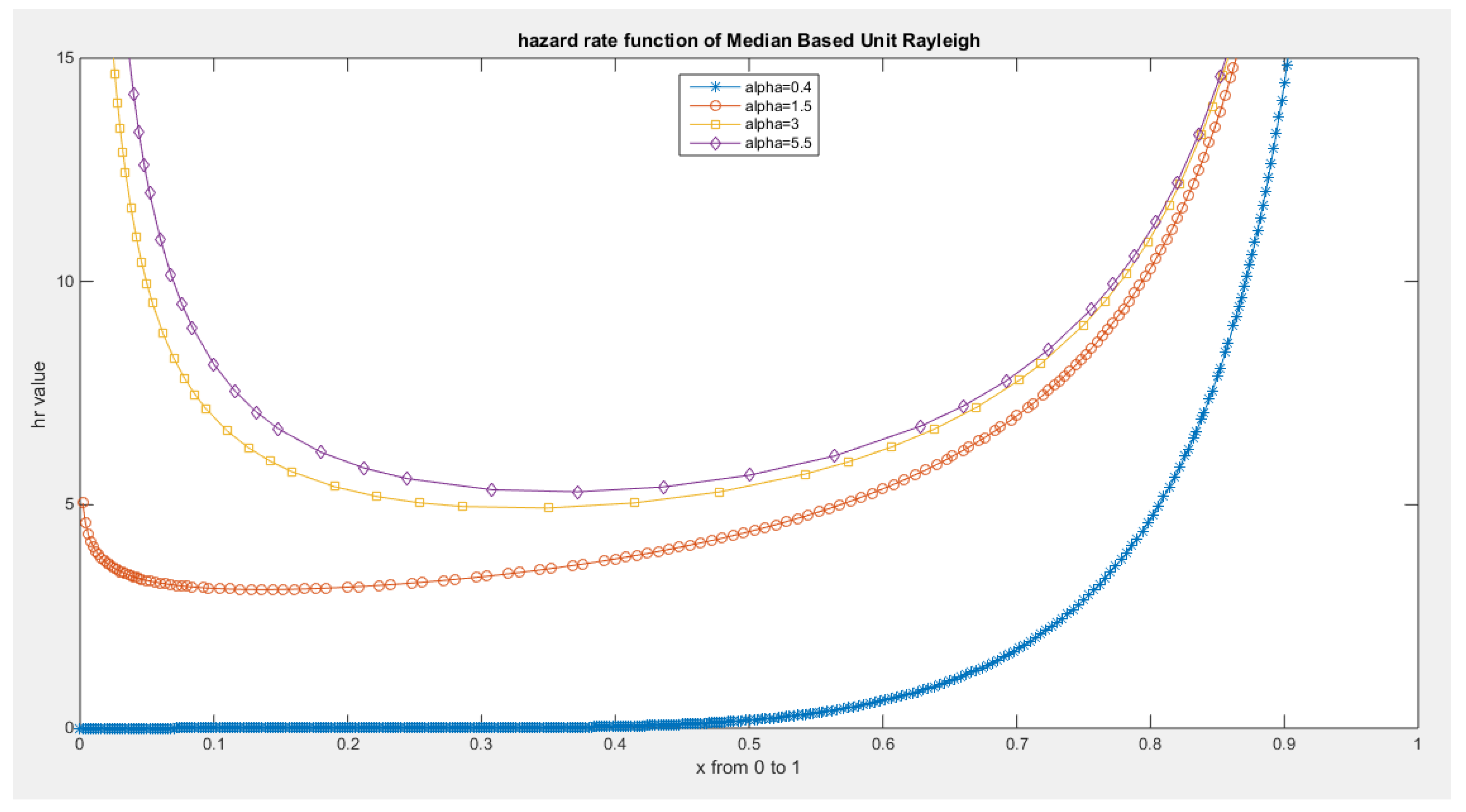

Figure 7.

hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 7.

hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

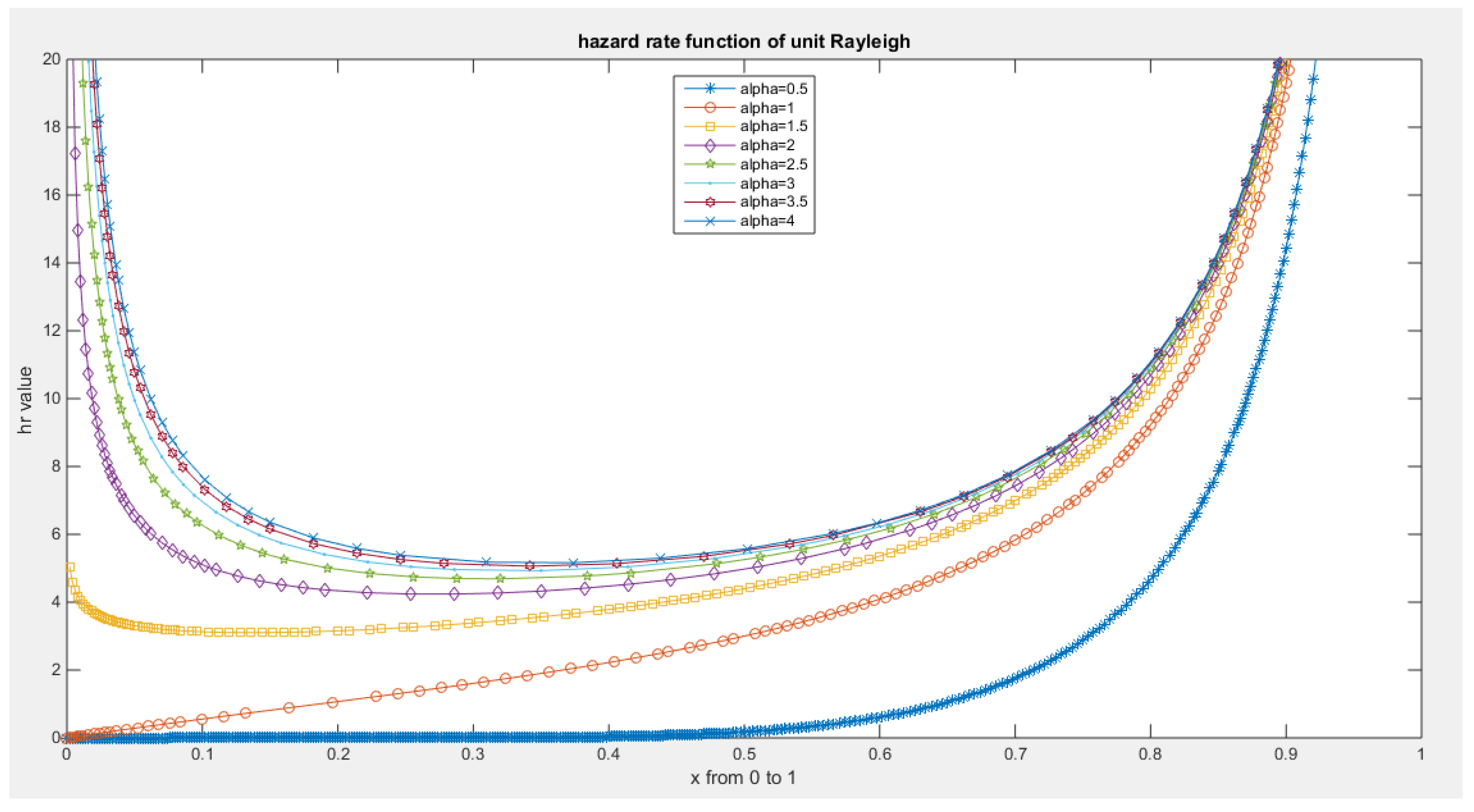

Figure 8.

hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 8.

hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

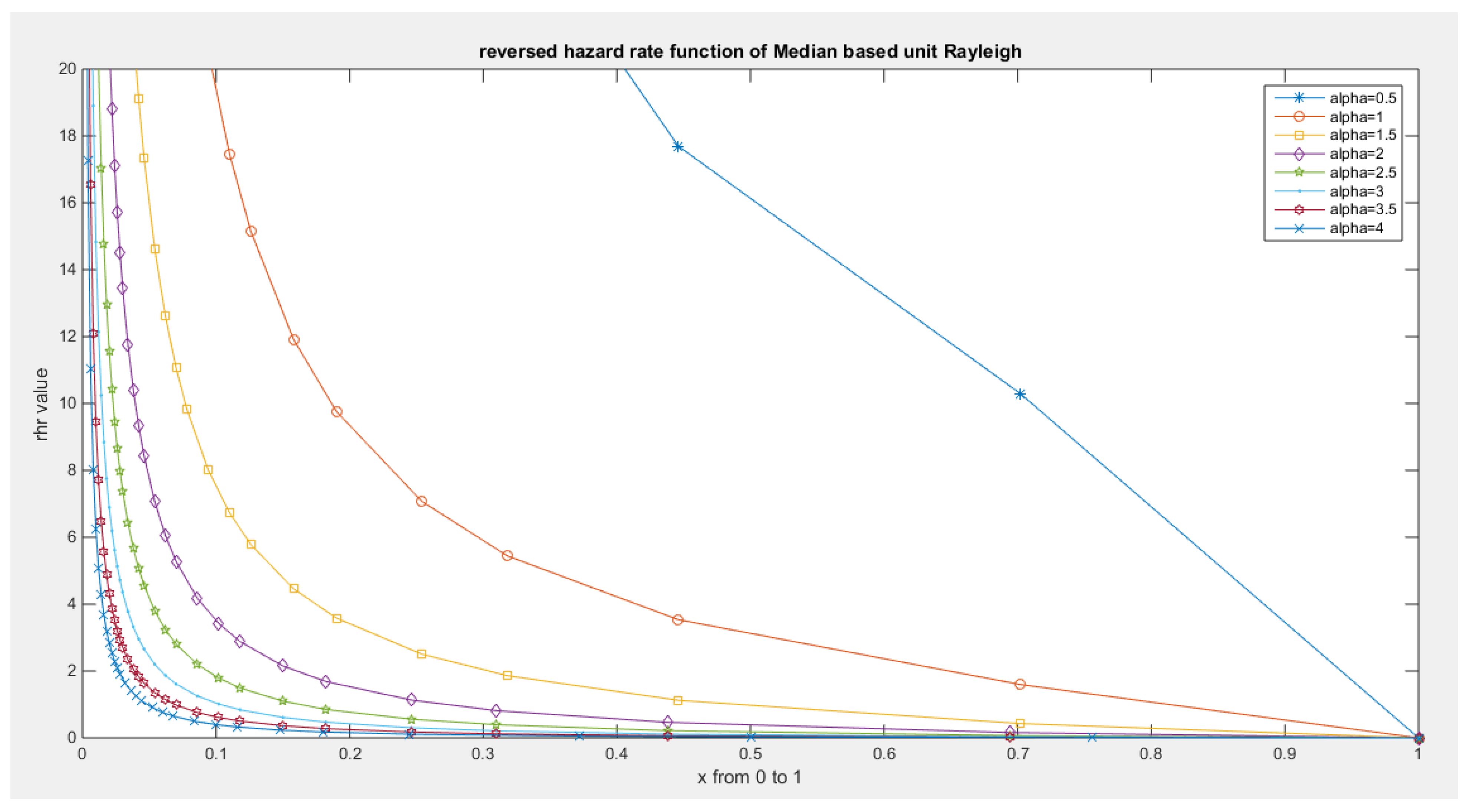

Figure 9.

reversed hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

Figure 9.

reversed hazard rate function of MBUR Distribution.

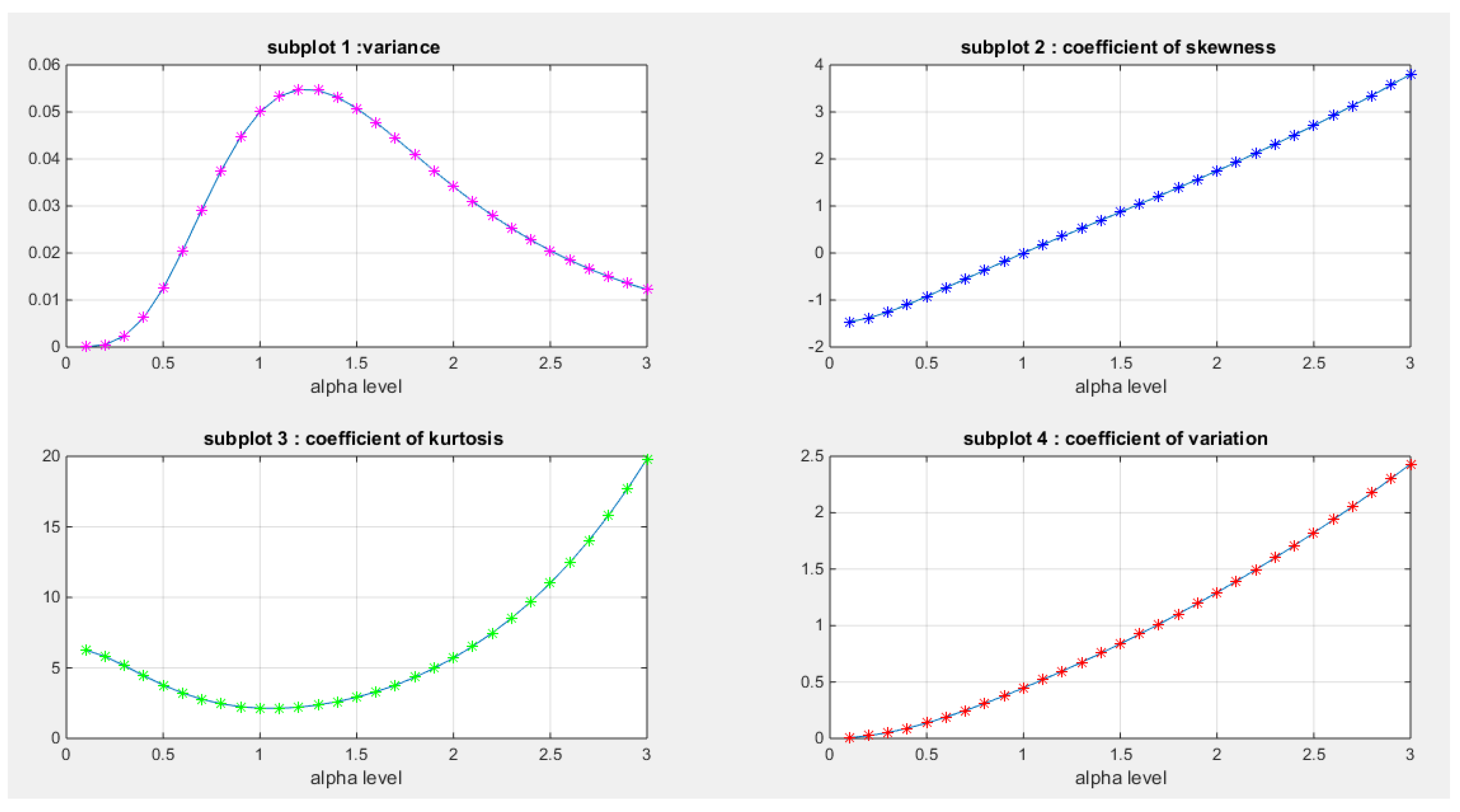

Figure 10.

shows that the maximum value of variance is attained between 0.05 and 0.06 when alpha values are between 1 and 1.5. At alpha level one, the coefficient of skewness is zero, coefficient of kurtosis is around 2 (2.1429) and the variance is 0.05. When alpha level is 0.668 the coefficient of kurtosis equals 2.9. When alpha level is 1.5, the coefficient of kurtosis is 2.9172.

Figure 10.

shows that the maximum value of variance is attained between 0.05 and 0.06 when alpha values are between 1 and 1.5. At alpha level one, the coefficient of skewness is zero, coefficient of kurtosis is around 2 (2.1429) and the variance is 0.05. When alpha level is 0.668 the coefficient of kurtosis equals 2.9. When alpha level is 1.5, the coefficient of kurtosis is 2.9172.

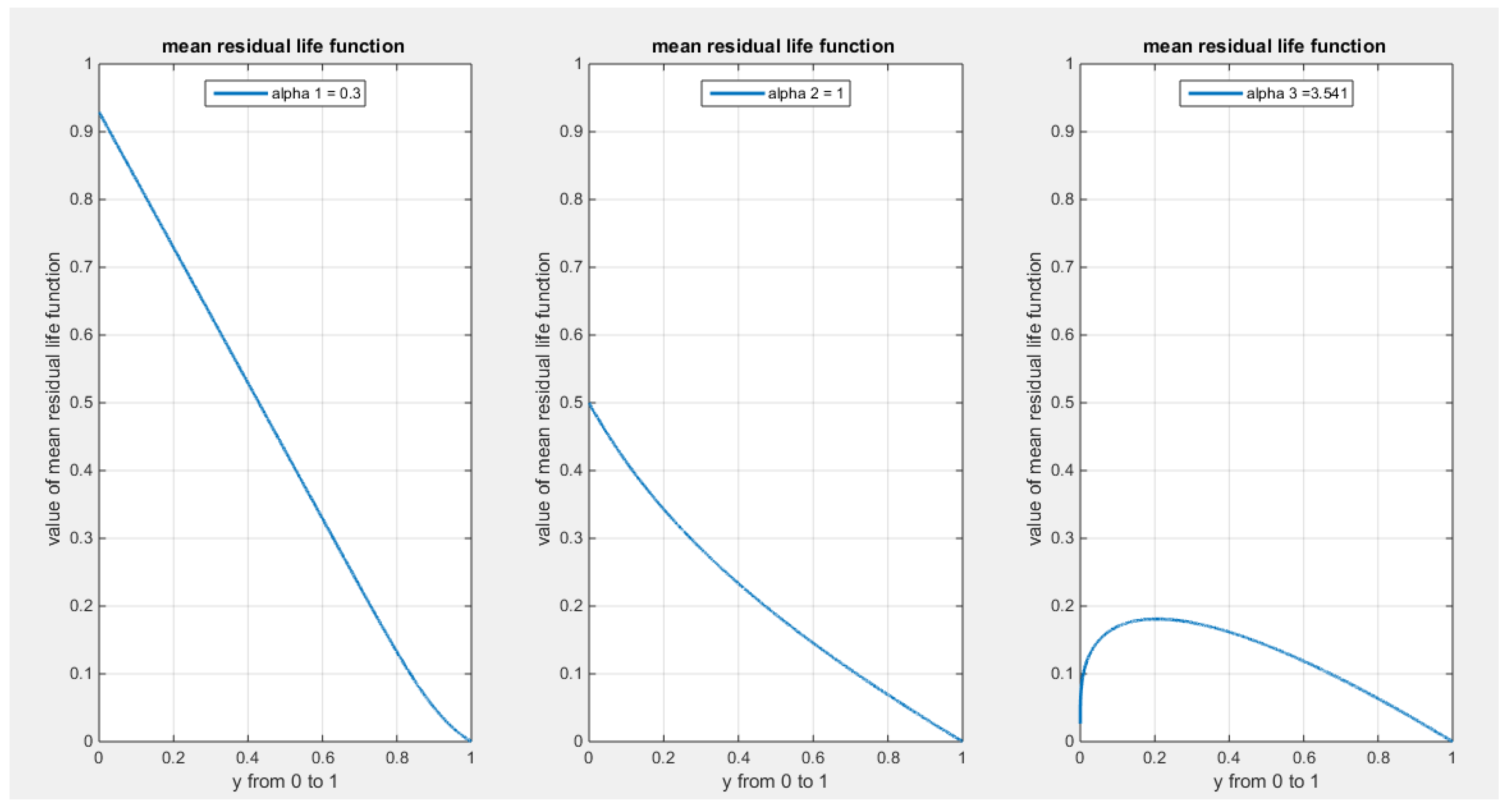

Figure 11.

shows mean residual life function at different levels of alpha.

Figure 11.

shows mean residual life function at different levels of alpha.

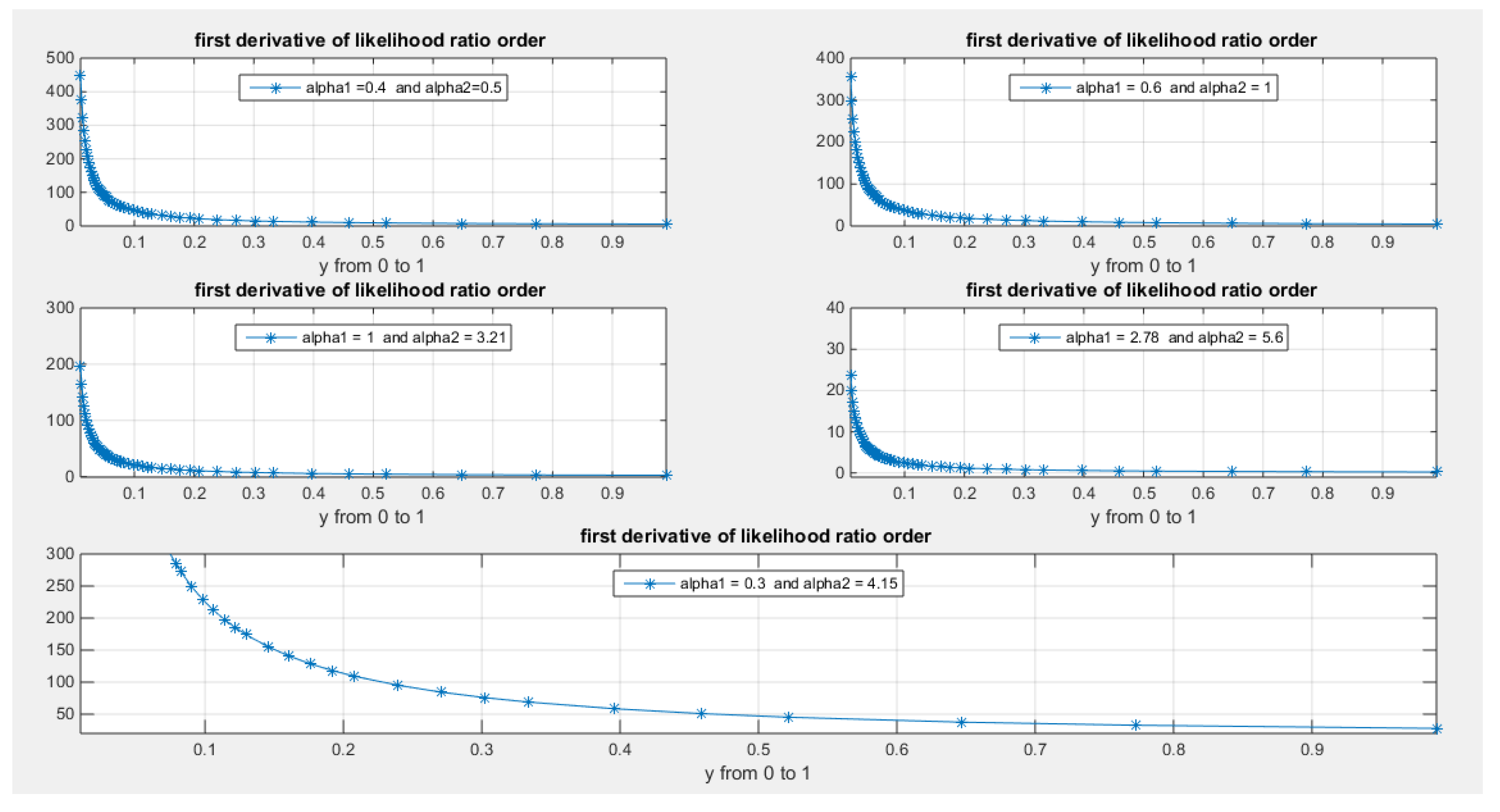

Figure 12.

shows the first derivative of the likelihood ratio order with respect to random variable y for all possible values of the parameter alpha with . It is a decreasing function in y and hence all

elements of stochastic ordering are true.

Figure 12.

shows the first derivative of the likelihood ratio order with respect to random variable y for all possible values of the parameter alpha with . It is a decreasing function in y and hence all

elements of stochastic ordering are true.

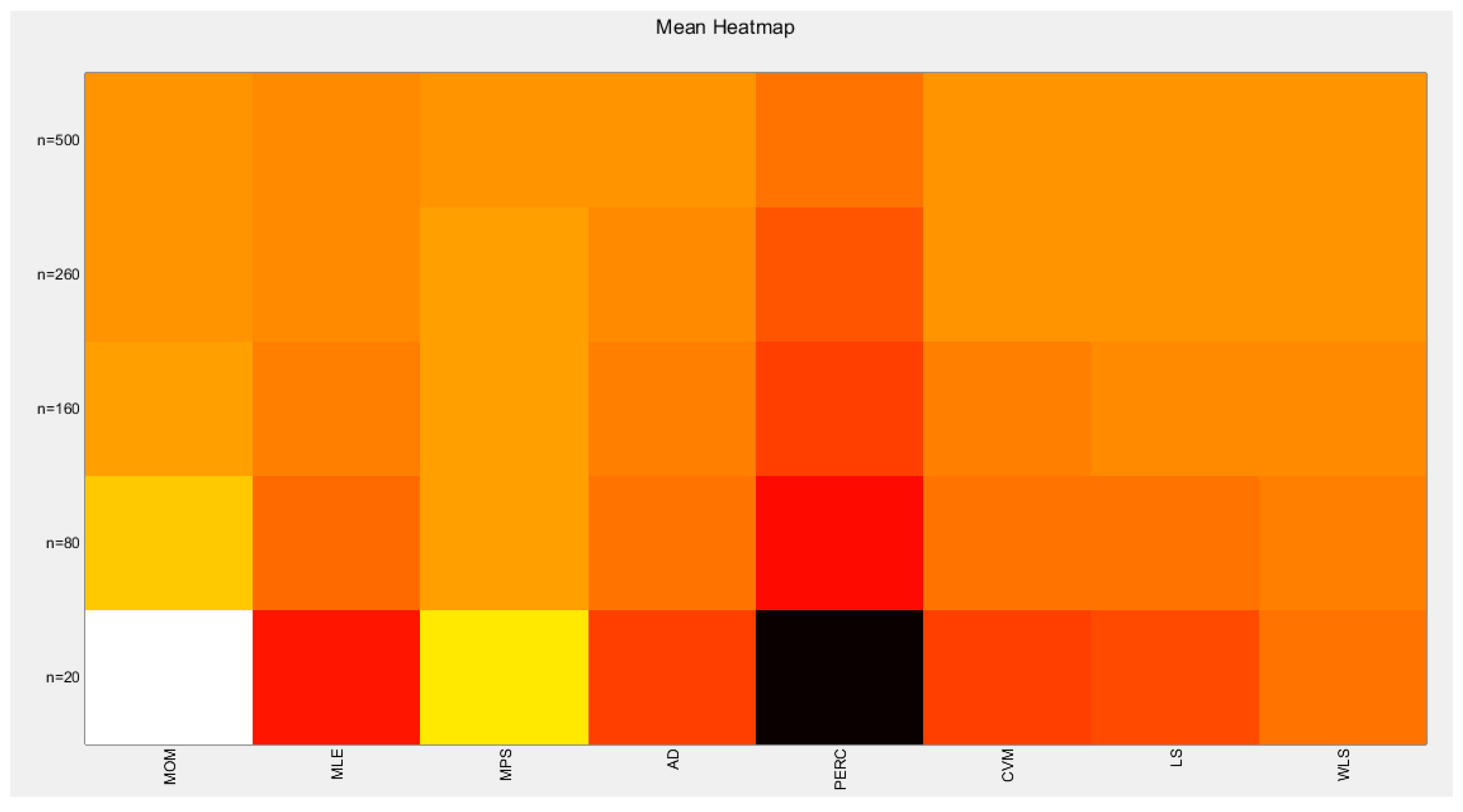

Figure 13.

shows the Heat-map for the mean of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different methods for estimation with alpha value 2.5. As the sample size increases the estimated alpha approaches the true value of the parameter.

Figure 13.

shows the Heat-map for the mean of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different methods for estimation with alpha value 2.5. As the sample size increases the estimated alpha approaches the true value of the parameter.

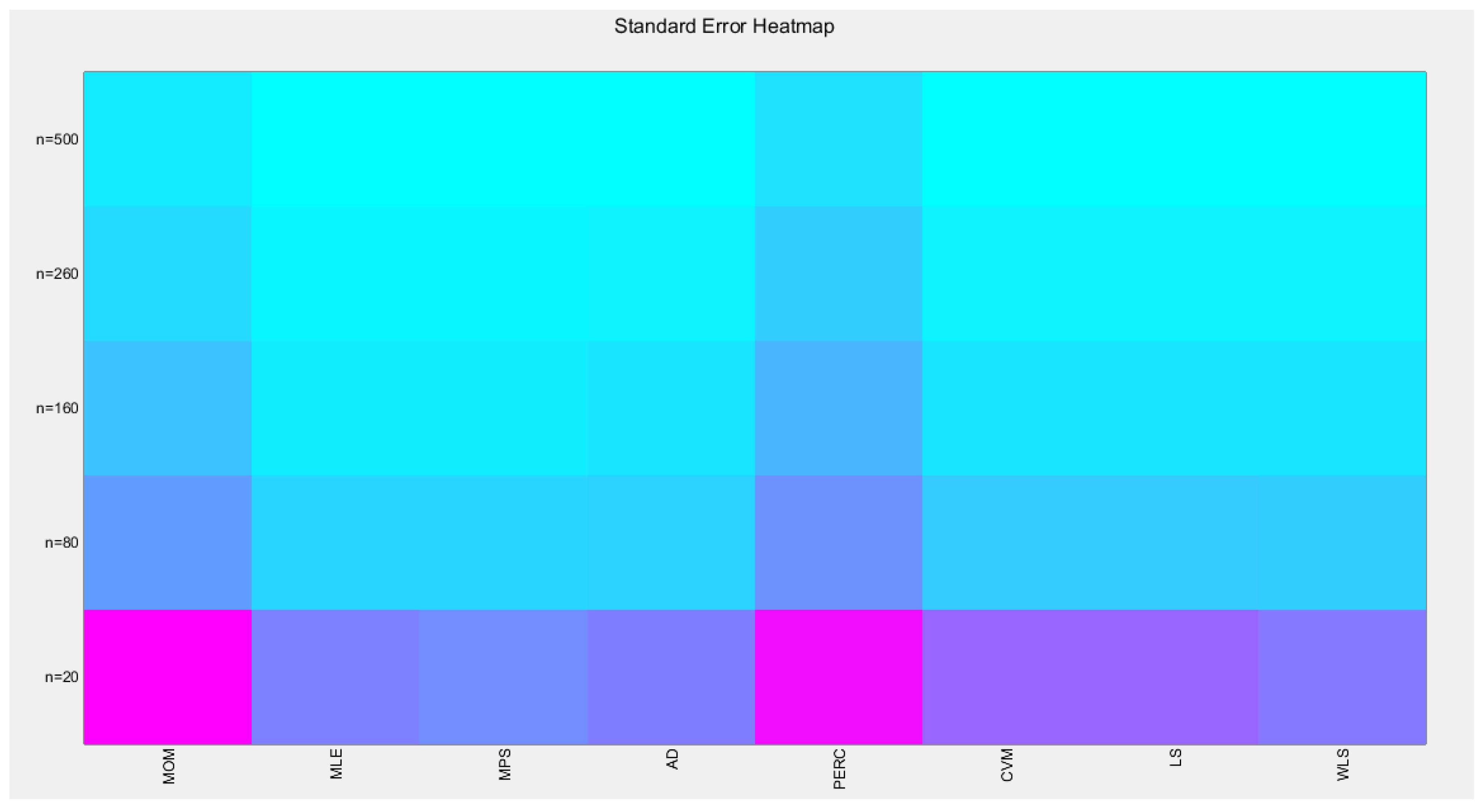

Figure 14.

shows the Heat-map for the standard error (SE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

Figure 14.

shows the Heat-map for the standard error (SE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

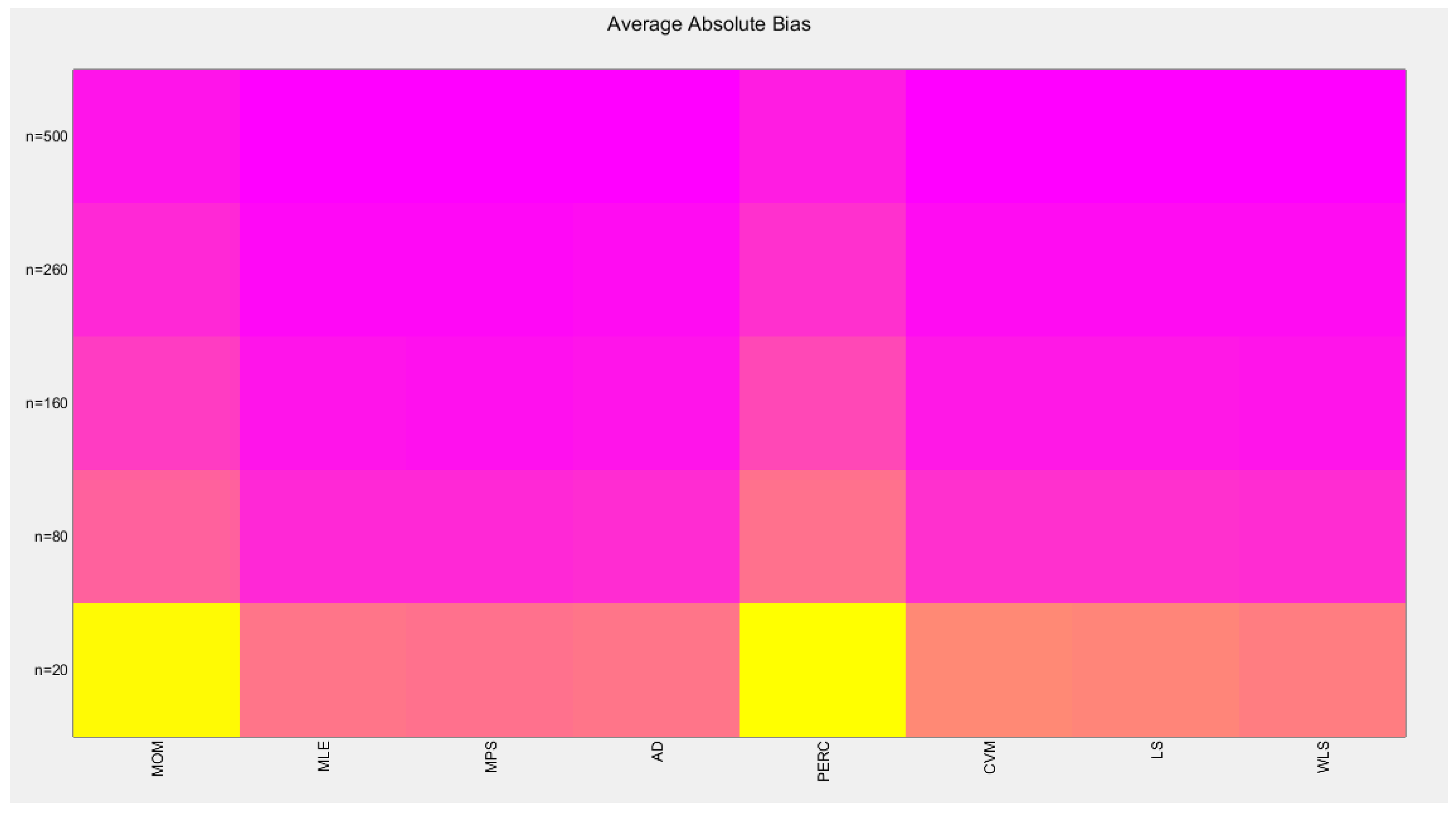

Figure 15.

shows the Heat-map for the average absolute bias (AAB) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

Figure 15.

shows the Heat-map for the average absolute bias (AAB) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

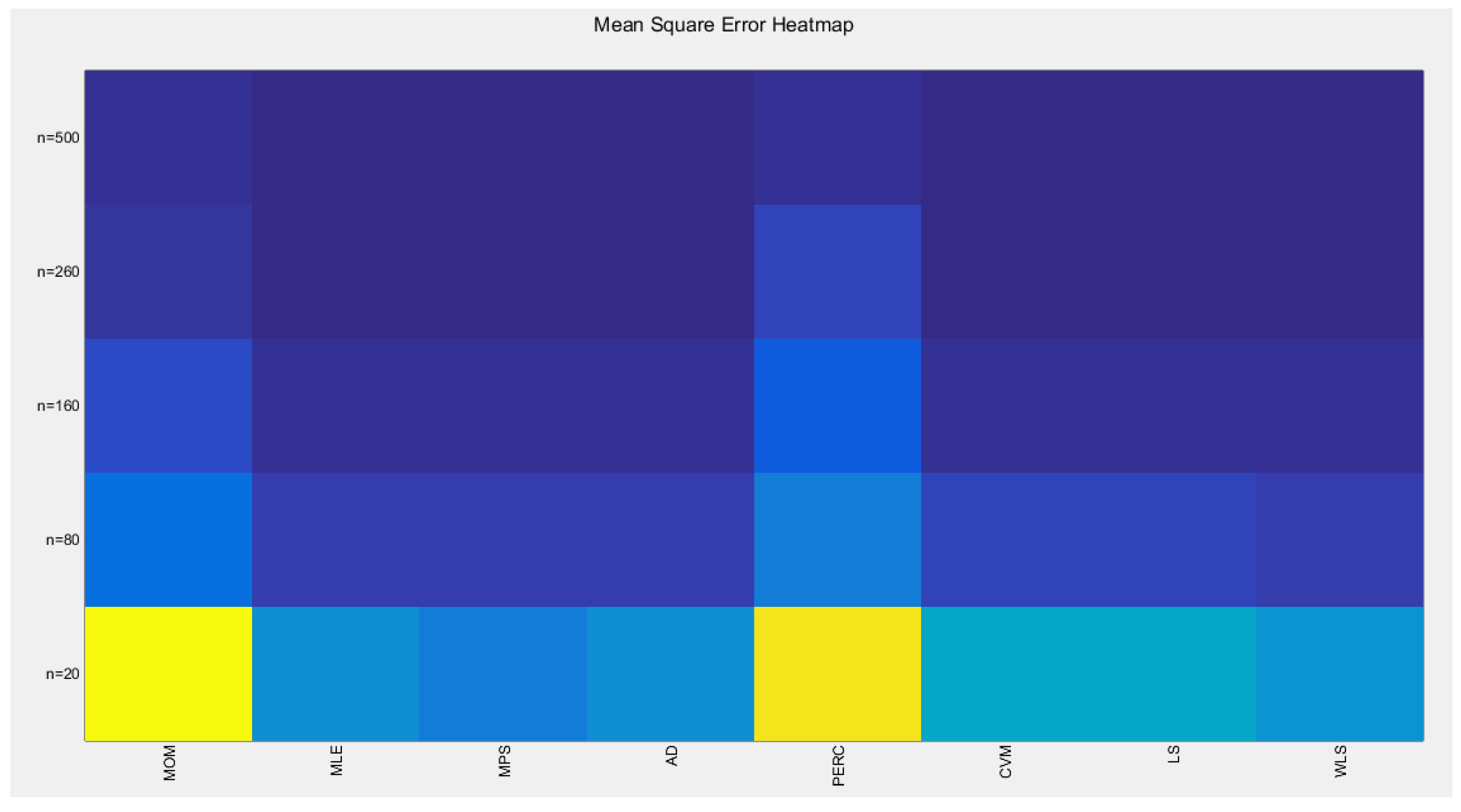

Figure 16.

shows the Heat-map for the mean square error (MSE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

Figure 16.

shows the Heat-map for the mean square error (MSE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

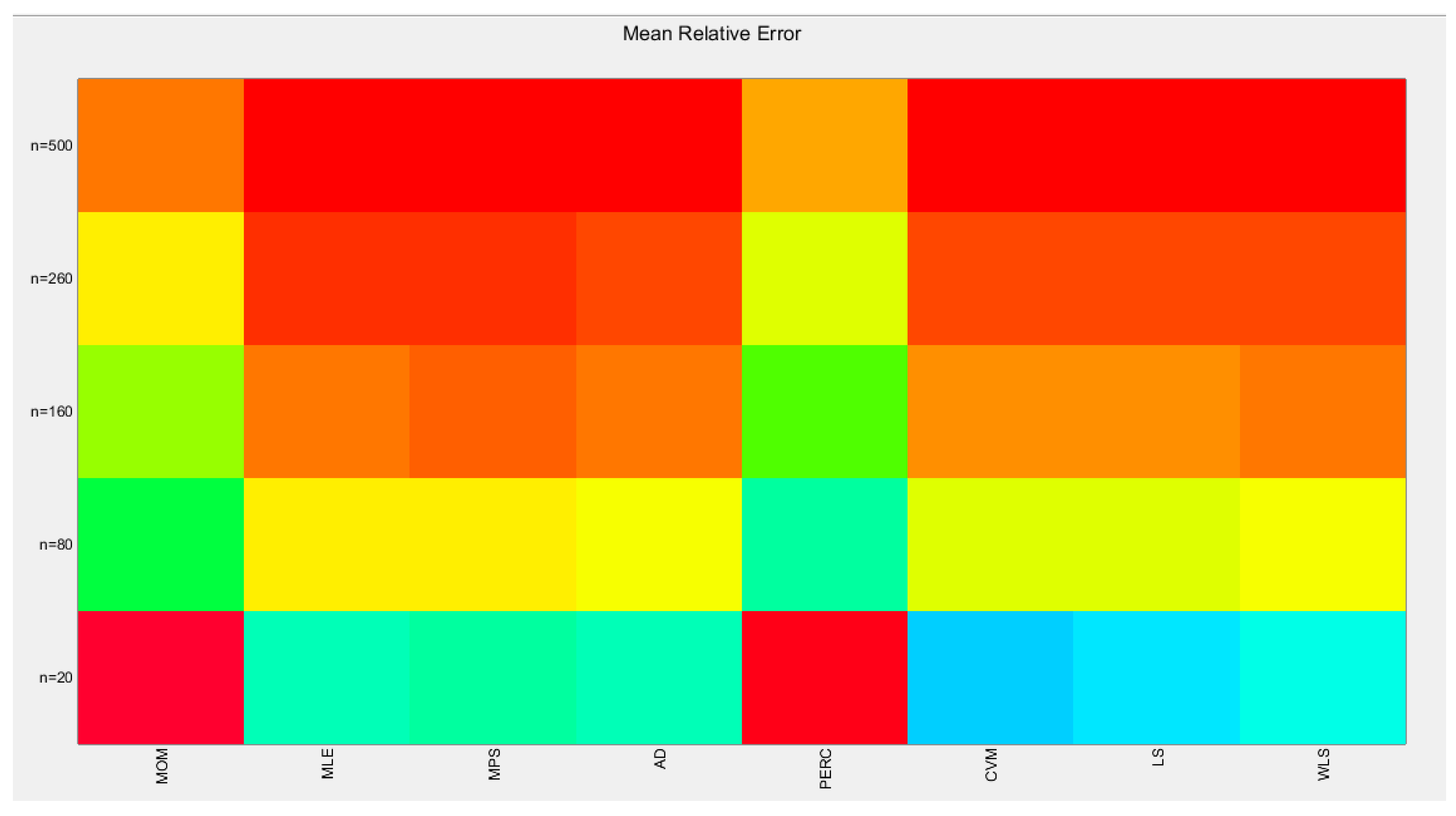

Figure 17.

shows the Heat-map for the mean relative error (MRE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

Figure 17.

shows the Heat-map for the mean relative error (MRE) of the estimated alpha parameter from running the simulation using different estimation methods with alpha value 2.5.

Figure 18.

shows the histogram with left skewness and associated boxplot with no outliers or extreme values. The TTT plot shows concave shape which supports increased failure rate that is obvious in the shape of the hazard function on the right lower graph.

Figure 18.

shows the histogram with left skewness and associated boxplot with no outliers or extreme values. The TTT plot shows concave shape which supports increased failure rate that is obvious in the shape of the hazard function on the right lower graph.

Figure 19.

shows the empirical survival function concave graph curved upward like the one in fig. (6) where the alpha is <1.

Figure 19.

shows the empirical survival function concave graph curved upward like the one in fig. (6) where the alpha is <1.

Figure 20.

shows the log-log plot of the log observations against the log empirical survival function with concave graph denoting fast decay and hence light tail.

Figure 20.

shows the log-log plot of the log observations against the log empirical survival function with concave graph denoting fast decay and hence light tail.

Figure 21.

shows the scaled TTT plot for the Quality support network data set with a concave shape supporting the increased hazard rate as reflected in the shape of the hazard function.

Figure 21.

shows the scaled TTT plot for the Quality support network data set with a concave shape supporting the increased hazard rate as reflected in the shape of the hazard function.

Figure 22.

shows the eCDF vs. theoretical CDF of the 5 distributions for the 2nd data set (Quality of support network).

Figure 22.

shows the eCDF vs. theoretical CDF of the 5 distributions for the 2nd data set (Quality of support network).

Figure 23.

shows the fitted PDFs for the different competitors.

Figure 23.

shows the fitted PDFs for the different competitors.

Figure 24.

shows the QQ plot for quality of support of network data set, on the left hand side of the graph and the log-likelihood on the right after fitting BMUR distribution.

Figure 24.

shows the QQ plot for quality of support of network data set, on the left hand side of the graph and the log-likelihood on the right after fitting BMUR distribution.

Figure 25.

shows the QQ plot after fitting both Topp-Leone and Kumaraswamy distributions. The PP plot after fitting both Beta and Unit Lindley distributions are also seen.

Figure 25.

shows the QQ plot after fitting both Topp-Leone and Kumaraswamy distributions. The PP plot after fitting both Beta and Unit Lindley distributions are also seen.

Figure 26.

shows the histogram with right skewness and associated boxplot with 3 outliers or extreme values on the upper tail of the distribution. The TTT plot shows convex shape which supports initial decreased failure rate that is obvious in the shape of the hazard function on the right lower graph.

Figure 26.

shows the histogram with right skewness and associated boxplot with 3 outliers or extreme values on the upper tail of the distribution. The TTT plot shows convex shape which supports initial decreased failure rate that is obvious in the shape of the hazard function on the right lower graph.

Figure 27.

shows the empirical survival function convex graph curved downward like the one in Fig. 6 where the alpha is >1.

Figure 27.

shows the empirical survival function convex graph curved downward like the one in Fig. 6 where the alpha is >1.

Figure 28.

shows the log-log plot of the log observations against the log empirical survival function with straight graph at higher values of observations denoting slow decay and hence heavier tail.

Figure 28.

shows the log-log plot of the log observations against the log empirical survival function with straight graph at higher values of observations denoting slow decay and hence heavier tail.

Figure 29.

shows the scaled TTT plot for the time between failure dataset with a convex shape followed by a concave shape more obvious on the upper part of the graph, supporting the decreased hazard rate followed by the increased hazard rate as reflected by the bathtub shape of the hazard function.

Figure 29.

shows the scaled TTT plot for the time between failure dataset with a convex shape followed by a concave shape more obvious on the upper part of the graph, supporting the decreased hazard rate followed by the increased hazard rate as reflected by the bathtub shape of the hazard function.

Figure 30.

shows the eCDF vs. theoretical CDF of the 5 distributions for the 5th data set (Time between failures of Secondary Reactor Pumps).

Figure 30.

shows the eCDF vs. theoretical CDF of the 5 distributions for the 5th data set (Time between failures of Secondary Reactor Pumps).

Figure 31.

shows the fitted PDFs for the different competitors.

Figure 31.

shows the fitted PDFs for the different competitors.

Figure 32.

shows the QQ plot for time between failures data set, on the left hand side of the graph and the log-likelihood on the right, after fitting the MBUR distribution.

Figure 32.

shows the QQ plot for time between failures data set, on the left hand side of the graph and the log-likelihood on the right, after fitting the MBUR distribution.

Figure 33.

shows the QQ plot after fitting both Topp-Leone and Kumaraswamy distributions. The PP plot after fitting both Beta and Unit Lindley distribution are also seen.

Figure 33.

shows the QQ plot after fitting both Topp-Leone and Kumaraswamy distributions. The PP plot after fitting both Beta and Unit Lindley distribution are also seen.

Table 1.

some differences between Beta, Kumaraswamy and the new distribution MBUR:.

Table 1.

some differences between Beta, Kumaraswamy and the new distribution MBUR:.

| |

Beta distribution |

Kumaraswamy distribution |

MBUR distribution |

| Parameters |

Two parameters |

Two parameters |

One parameter |

PDF shapes

(depends on parameters) |

Unimodal, Uni-antimodal (bathtub), Increasing & left skew, J-shape, decreasing & right skew , constant. |

Unimodal, Uni-antimodal (bathtub), Increasing & left skew, J-shape, decreasing & right skew , constant. |

Unimodal, Uni-antimodal (bathtub), Increasing & left skew, J-shape, decreasing & right skew. |

| Mode |

Explicit expression |

Explicit expression |

Explicit expression |

Behavior of

Skewness& kurtosis |

Good behavior as function of parameters |

Good behavior as function of parameters |

Good behavior as function of parameter |

| CDF |

Involves special function. No explicit closed form |

Simple explicit closed formula not involving any special functions |

Simple explicit closed formula not involving any special functions |

| Quantile function |

No explicit closed formula |

Simple closed explicit formula |

Closed explicit formula |

| R.N. generator |

No simple formula |

Simple formula |

Simple formula |

| Moments |

Simple formula |

No simple closed formula |

Simple formula |

| regression |

Mean based regression |

Median-based quantile regression |

Mean and Median-based quantile regression |

| One-parameter subfamily symmetric distribution |

Exist ( if both shape parameters are equal to 2, this gives symmetric distribution around 0.5) |

Not exist ( if both shape parameters are equal to one , this gives uniform distribution) |

Exist ( if alpha parameter equals to one , this gives symmetric distribution around 0.5) |

| Moments of order statistics |

No simple formula |

Simple formula |

Simple formula |

Table 2.

shows the mean from the 1000 replicates for each method.

Table 2.

shows the mean from the 1000 replicates for each method.

| mean |

MOM |

MLE |

MPS |

AD |

PERC |

CVM |

LS |

WLS |

| n=20 |

2.6001 |

2.4561 |

2.5321 |

2.4725 |

2.3617 |

2.4727 |

2.4755 |

2.4905 |

| n=80 |

2.52 |

2.486 |

2.5043 |

2.4896 |

2.4538 |

2.4896 |

2.4908 |

2.4943 |

| n=160 |

2.5069 |

2.4936 |

2.5039 |

2.495 |

2.4711 |

2.4953 |

2.496 |

2.4977 |

| n=260 |

2.5030 |

2.4972 |

2.5042 |

2.4991 |

2.4797 |

2.5004 |

2.5008 |

2.5008 |

| n=500 |

2.5028 |

2.4991 |

2.5032 |

2.4996 |

2.491 |

2.4997 |

2.5002 |

2.5004 |

Table 3.

shows the SE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

Table 3.

shows the SE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

| SE |

MOM |

MLE |

MPS |

AD |

PERC |

CVM |

LS |

WLS |

| n=20 |

0.013 |

0.0071 |

0.0065 |

0.0072 |

0.0123 |

0.0084 |

0.0083 |

0.0074 |

| n=80 |

0.0057 |

0.0033 |

0.0032 |

0.0034 |

0.0063 |

0.0037 |

0.0037 |

0.0035 |

| n=160 |

0.0041 |

0.0022 |

0.0022 |

0.0024 |

0.0046 |

0.0025 |

0.0025 |

0.0024 |

| n=260 |

0.0031 |

0.0018 |

0.0018 |

0.0019 |

0.0036 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

0.0019 |

| n=500 |

0.0023 |

0.0013 |

0.0013 |

0.0014 |

0.0027 |

0.0014 |

0.0014 |

0.0014 |

Table 4.

shows the AAB from the 1000 replicates for each method.

Table 4.

shows the AAB from the 1000 replicates for each method.

| AAB |

MOM |

MLE |

MPS |

AD |

PERC |

CVM |

LS |

WLS |

| n=20 |

0.3221 |

0.1673 |

0.1631 |

0.1706 |

0.3296 |

0.1912 |

0.1902 |

0.1776 |

| n=80 |

0.1444 |

0.0827 |

0.0809 |

0.085 |

0.1649 |

0.0902 |

0.0901 |

0.0854 |

| n=160 |

0.1037 |

0.0561 |

0.0552 |

0.0595 |

0.1195 |

0.0626 |

0.0625 |

0.0596 |

| n=260 |

0.0791 |

0.0457 |

0.0456 |

0.0481 |

0.0917 |

0.0506 |

0.0506 |

0.0481 |

| n=500 |

0.0579 |

0.0328 |

0.0327 |

0.0341 |

0.0667 |

0.0355 |

0.0354 |

0.0341 |

Table 5.

shows the MSE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

Table 5.

shows the MSE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

| MSE |

MOM |

MLE |

MPS |

AD |

PERC |

CVM |

LS |

WLS |

| n=20 |

0.1798 |

0.0519 |

0.0427 |

0.0521 |

0.1701 |

0.0708 |

0.0698 |

0.0553 |

| n=80 |

0.0333 |

0.0119 |

0.0102 |

0.012 |

0.0417 |

0.0137 |

0.0137 |

0.0120 |

| n=160 |

0.0166 |

0.0051 |

0.0048 |

0.0057 |

0.0224 |

0.0063 |

0.0063 |

0.0056 |

| n=260 |

0.0098 |

0.0032 |

0.0032 |

0.0036 |

0.013 |

0.004 |

0.004 |

0.0036 |

| n=500 |

0.0053 |

0.0017 |

0.0017 |

0.0018 |

0.0071 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

0.0018 |

Table 6.

shows the MRE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

Table 6.

shows the MRE from the 1000 replicates for each method.

| MRE |

MOM |

MLE |

MPS |

AD |

PERC |

CVM |

LS |

WLS |

| n=20 |

0.1288 |

0.0669 |

0.0652 |

0.0682 |

0.1318 |

0.0765 |

0.0761 |

0.0710 |

| n=80 |

0.0578 |

0.0331 |

0.0324 |

0.0340 |

0.066 |

0.0361 |

0.0361 |

0.0342 |

| n=160 |

0.0415 |

0.0224 |

0.0221 |

0.0238 |

0.0478 |

0.025 |

0.025 |

0.0238 |

| n=260 |

0.0317 |

0.0183 |

0.0182 |

0.0192 |

0.0367 |

0.0202 |

0.0202 |

0.0192 |

| n=500 |

0.0231 |

0.0131 |

0.0131 |

0.0136 |

0.0267 |

0.0142 |

0.0142 |

0.0137 |

Table 7.

shows Dwelling without Basic facilities data set.

Table 7.

shows Dwelling without Basic facilities data set.

| 0.008 |

0.007 |

0.002 |

0.094 |

0.123 |

0.023 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0.057 |

0.004 |

| 0.005 |

0.001 |

0.004 |

0.035 |

0.002 |

0.006 |

0.064 |

0.025 |

0.112 |

0.118 |

| 0.001 |

0.259 |

0.001 |

0.023 |

0.009 |

0.015 |

0.002 |

0.003 |

0.049 |

0.005 |

| 0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 8.

shows Quality of support Network data set.

Table 8.

shows Quality of support Network data set.

| 0.98 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

0.94 |

0.93 |

0.8 |

0.82 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.89 |

| 0.78 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

0.9 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

0.77 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

Table 9.

shows Educational attainment data set.

Table 9.

shows Educational attainment data set.

| 0.84 |

0.86 |

0.8 |

0.92 |

0.67 |

0.59 |

0.43 |

0.94 |

0.82 |

0.91 |

| 0.91 |

0.81 |

0.86 |

0.76 |

0.86 |

0.76 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.63 |

0.89 |

| 0.89 |

0.94 |

0.74 |

0.42 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

0.93 |

0.55 |

0.92 |

0.9 |

| 0.63 |

0.84 |

0.89 |

0.42 |

0.82 |

0.92 |

|

|

|

|

Table 10.

shows Flood Data set.

Table 10.

shows Flood Data set.

| 0.26 |

0.27 |

0.3 |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.34 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.39 |

0.4 |

| 0.41 |

0.42 |

0.42 |

0.42 |

045 |

0.48 |

0.49 |

0.61 |

0.65 |

0.74 |

Table 11.

shows time between Failures data set.

Table 11.

shows time between Failures data set.

| 0.216 |

0.015 |

0.4082 |

0.0746 |

0.0358 |

0.0199 |

0.0402 |

0.0101 |

0.0605 |

| 0.0954 |

0.1359 |

0.0273 |

0.0491 |

0.3465 |

0.007 |

0.656 |

0.106 |

0.0062 |

| 0.4992 |

0.0614 |

0.532 |

0.0347 |

0.1921 |

|

|

|

|

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics of the second data set.

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics of the second data set.

| min |

mean |

std |

skewness |

kurtosis |

25percentile

|

50perc

|

75perc

|

max |

| 0.77 |

0.9005 |

0.064 |

-0.9147 |

2.6716 |

0.865 |

0.92 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

Table 13.

Estimators and validation indices for the Second data set.

Table 13.

Estimators and validation indices for the Second data set.

| |

Beta |

Kumaraswamy |

MBUR |

Topp-Leone |

Unit-Lindley |

| theta |

|

|

0.3591 |

71.2975 |

0.1334 |

|

|

| Var |

86.461 |

9.0379 |

15.7459 |

3.2005 |

0.000837 |

254.1667 |

0.00045 |

| 9.0379 |

1.0646 |

3.2005 |

1.0347 |

| SE |

2.079 |

0.8873 |

0.0063 |

3.565 |

0.0047 |

| 0.231 |

0.2275 |

| AIC |

-56.5056 |

-56.7274 |

-58.079 |

-56.6796 |

-57.3746 |

| CAIC |

-55.7997 |

-56.0215 |

-57.8567 |

-56.4574 |

-57.1523 |

| BIC |

-54.5141 |

-54.7359 |

-57.0832 |

-55.6839 |

-56.3788 |

| HQIC |

-56.1168 |

-56.3386 |

-57.8846 |

-56.4852 |

-57.1802 |

| LL |

30.2528 |

30.3637 |

30.0395 |

29.3398 |

29.6873 |

| K-S |

0.0974 |

0.0995 |

0.1309 |

0.1327 |

0.1057 |

| H0

|

Fail to reject |

Fail to reject |

Fail to reject |

Fail to reject |

Reject to reject |

| P-value |

0.9416 |

0.9513 |

0.8399 |

0.4627 |

0.954 |

| AD |

0.3828 |

0.3527 |

0.3184 |

0.9751 |

0.2749 |

| CVM |

0.0566 |

0.0498 |

0.0407 |

0.1719 |

0.0261 |

Table 14.

Descriptive statistics of the fifth data set.

Table 14.

Descriptive statistics of the fifth data set.

| min |

mean |

std |

skewness |

kurtosis |

25perc

|

50perc

|

75perc

|

max |

| 0.0062 |

0.1578 |

0.1931 |

1.4614 |

3.9988 |

0.0292 |

0.0614 |

0.21 |

0.656 |

Table 15.

Estimators and validation indices for the Fifth data set.

Table 15.

Estimators and validation indices for the Fifth data set.

| |

Beta |

Kumaraswamy |

MBUR |

Topp-Leone |

Unit-Lindley |

| theta |

|

|

1.7886 |

0.4891 |

4.1495 |

|

|

| Var |

0.071 |

0.2801 |

0.0198 |

0.1033 |

0.018 |

0.0104 |

0.5543 |

| 0.2801 |

1.647 |

0.1033 |

0.9135 |

| SE |

0.0555 |

0.0293 |

0.0279 |

0.0213 |

0.1552 |

| 0.2676 |

0.1993 |

| AIC |

-36.0571 |

-36.6592 |

-37.862 |

-35.5653 |

-27.007 |

| CAIC |

-35.4571 |

-36.0592 |

-37.6712 |

-35.3749 |

-26.8165 |

| BIC |

-33.7861 |

-34.3882 |

-36.7262 |

-34.4298 |

-25.8715 |

| HQIC |

-35.4859 |

-36.0881 |

-37.5764 |

-35.2798 |

-26.7214 |

| LL |

20.0285 |

20.3296 |

19.9310 |

18.7827 |

14.5035 |

| K-S |

0.1541 |

0.1393 |

0.1584 |

0.1962 |

0.3274 |

| H0

|

Fail to reject |

Fail to reject |

Fail to reject |

Fail to Reject |

Reject |

| P-value |

0.5918 |

0.7123 |

0.5575 |

0.2982 |

0.0107 |

| AD |

0.6886 |

0.5755 |

0.6703 |

1.1022 |

4.7907 |

| CVM |

0.1264 |

0.0989 |

0.1253 |

0.2149 |

0.8115 |