Submitted:

04 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Autoimmune diseases (AIDs) are a group of disorders, in which the immune system attacks the body own tissues leading to chronic inflammation and organ damage. These diseases are difficult to treat due to variability in drug PK among individuals, patient responses to treatment, and the side effects of long-term immunosuppressive therapies. In recent years, pharmacometrics has emerged as a critical tool in Drug Discovery and Development (DDD) and precision medicine. The aim of this review is to explore the diverse roles that pharmacometrics has played in addressing the challenges associated with DDD and personalized therapies in the treatment of AIDs. Methods: The review synthesizes research from past two decades on pharmacometric methodologies, including Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, Pharmaco-kinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, Disease Progression (DisP) modeling, population modeling, and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP). The incorporation of Artificial Intelli-gence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) into pharmacometrics is also discussed. Results: Pharmacometrics has demonstrated significant potential in optimizing dosing regimens, improving drug safety, and predicting patient-specific responses in AIDs. PBPK and PK/PD models have been instrumental in personalizing treatments, while DisP and QSP models provide insights into disease evolution and pathophysiological mechanisms in AIDs. AI/ML implementation has further enhanced precision of these models. Conclusions: Pharmacometrics plays a crucial role in bridging preclinical findings and clinical applications, driving more personalized and effective treatments for AIDs. Its integration into DDD and translational science in combination with AI and ML algorithms holds promise for advancing therapeutic strategies and improving autoimmune patient outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

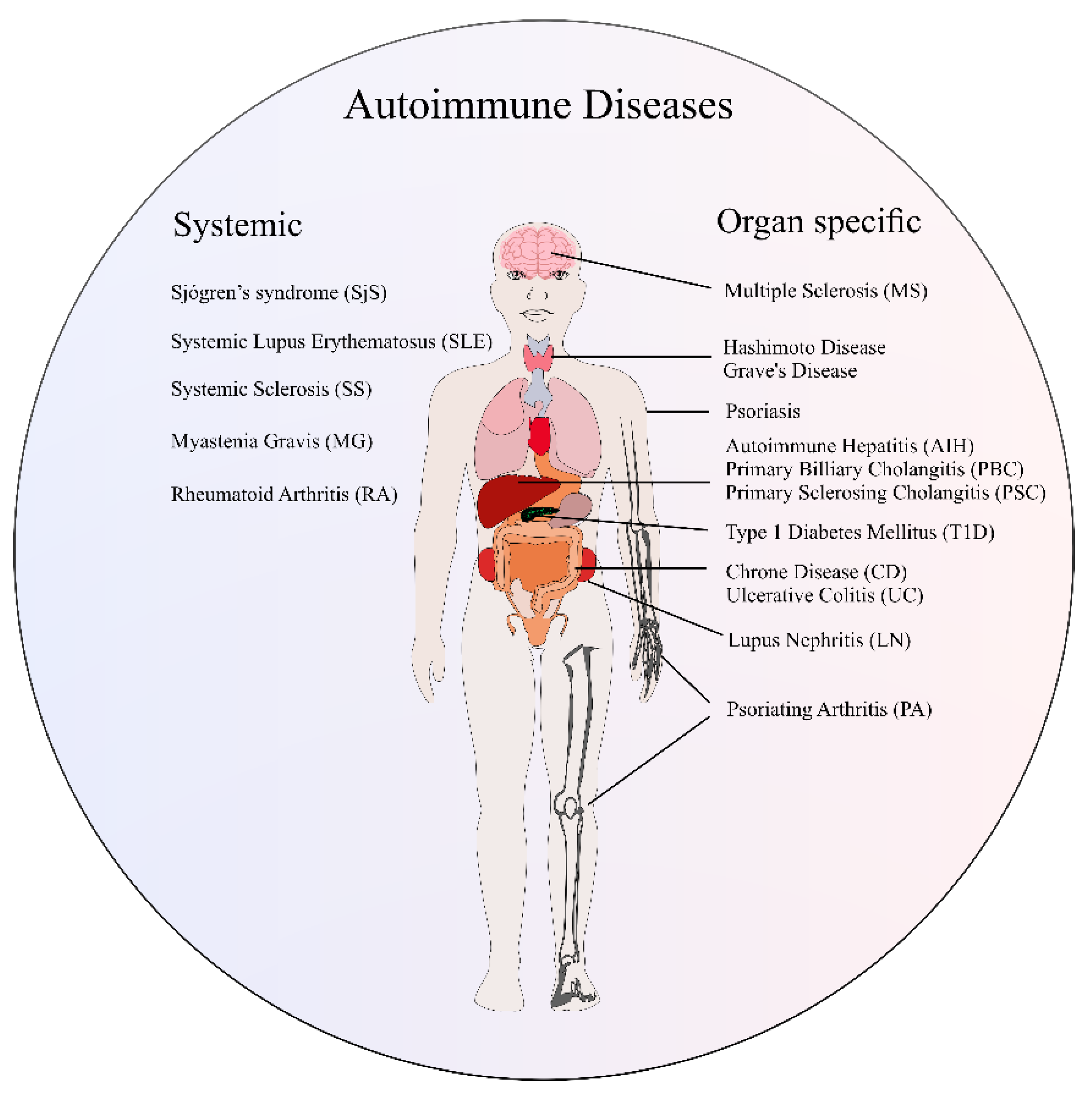

2. Overview of Autoimmune Diseases

3. Biomarkers and Clinical Outcomes in Autoimmune Diseases

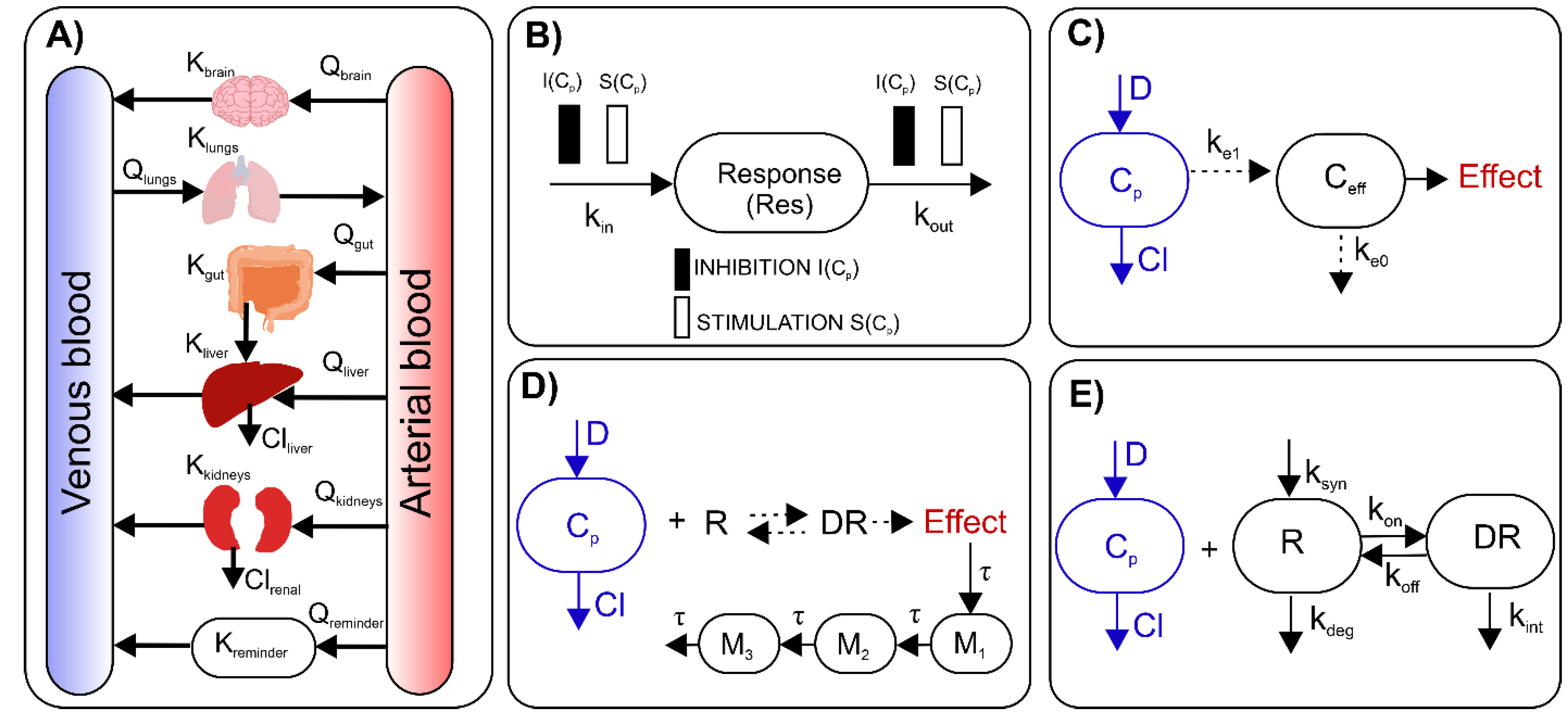

4. A Brief Overview of Basic Pharmacometric Methods

5. Pharmacometrics in Pre-Clinical Studies on Autoimmune Diseases

6. Translational Pharmacometric Approaches in Autoimmune Diseases

7. Population Modeling and Simulation in Clinical Applications for Autoimmune Diseases

8. PBPK Modeling

9. QSP and Boolean Networks Modeling in Autoimmune Diseases

10. Incorporating AI and ML into Pharmacometrics in the Context of Autoimmune Diseases

11. Limitations of Pharmacometric Methods

12. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fugger, L.; Jensen, L.T.; Rossjohn, J. Challenges, Progress, and Prospects of Developing Therapies to Treat Autoimmune Diseases. Cell 2020, 181, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekara, S. The Treatment Strategies of Autoimmune Disease May Need a Different Approach from Conventional Protocol: A Review. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2012, 44, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Liao, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, M.; Zhao, M.; Lu, Q. Epigenetics as Biomarkers in Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 196, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safitri, R.A.; Sayogo, W.; Muflihan, Y.; Maela, N.; Setiawan, Y.W.; Rahma, S.F. Drug Interactions in Autoimmune Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). J. Multidisiplin Madani 2024, 4, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, S.; Segafredo, G.; Piccolis, M.; Das, A.; Das, M.; Loffredi, N.; Larbi, A.; Mwamelo, K.; Villanueva, E.; Nobre, S.; et al. Expanding Access to Biotherapeutics in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries through Public Health Non-Exclusive Voluntary Intellectual Property Licensing: Considerations, Requirements, and Opportunities. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e145–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Zahorska-Markiewicz, E. Małecka-Tendera, M. Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, J. Chudek Patofizjologia kliniczna. Podręcznik. Available online: https://www-1elibrary-1com-1pl-1nc4armv6055a.hanproxy.cm-uj.krakow.pl/pdfreader/patofizjologia-kliniczna-podrcznik (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Juarranz, Y. Molecular and Cellular Basis of Autoimmune Diseases. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; Sattar, N.; McMurray, J.J.V.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Co-Occurrence of Autoimmune Disorders over Time and by Age, Sex, and Socioeconomic Status: A Population-Based Cohort Study of 22 Million Individuals in the UK. The Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.; Kahlenberg, J.M. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; McInnes, I.B. Rheumatoid Arthritis. The Lancet 2016, 388, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Emmi, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Murdaca, G.; Indiveri, F.; Puppo, F. Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Systemic Autoimmune Disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, M.; Ma, N.; Huang, F.; Zhong, R. Epidemiology of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, F.; Böckle, B.C. Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 980–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkmann, E.R.; Andréasson, K.; Smith, V. Systemic Sclerosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2023, 401, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, D.L.; Jialal, I. Hashimoto Thyroiditis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, L.C.; Wood, C.L.; Cheetham, T. Graves’ Disease: Moving Forwards. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMeglio, L.A.; Evans-Molina, C.; Oram, R.A. Type 1 Diabetes. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2018, 391, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, G.D.; James, S.; Dabelea, D.; Pihoker, C.; Svennson, J.; Maniam, J.; Klatman, E.L.; Patterson, C.C. Global Estimates of Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Atlas, 10th Edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haki, M.; AL-Biati, H.A.; Al-Tameemi, Z.S.; Ali, I.S.; Al-hussaniy, H.A. Review of Multiple Sclerosis: Epidemiology, Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis Therapy and Prognosis. Available online: https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2022/april/multiple-sclerosis-diagnosis-therapy-and-prognosis (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van der Mei, I.; et al. Rising Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis Worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, Third Edition. Mult. Scler. Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obarska, I.; Stajszczyk, M. Wycena świadczeń w programach lekowych istotnym elementem budowy strategii zwiększania dostępu do innowacyjnych terapii w chorobach autoimmunizacyjnych.

- Parikh, C.R.; Ponnampalam, J.K.; Seligmann, G.; Coelewij, L.; Pineda-Torra, I.; Jury, E.C.; Ciurtin, C. Impact of Immunogenicity on Clinical Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Biologic Agents Used for Treatment of Inflammatory Arthritis in Children Compared to Adults. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2021, 13, 1759720X211002685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, G.; Arabi, Y.M.; Bartz, R.; Ranzani, O.; Scheibe, F.; Darmon, M.; Helms, J. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Diseases in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Nagafuchi, Y.; Fujio, K. Clinical and Immunological Biomarkers for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis – Laboratory and Clinical Perspectives - PMC. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8161594/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Pignatelli, P.; Ettorre, E.; Menichelli, D.; Pani, A.; Violi, F.; Pastori, D. Seronegative Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Refining the Value of “Non-Criteria” Antibodies for Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Haematologica 2020, 105, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauchais, A.L.; Lambert, M.; Launay, D.; Michon-Pasturel, U.; Queyrel, V.; Nguyen, N.; Hebbar, M.; Hachulla, E.; Devulder, B.; Hatron, P.Y. Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Prevalence and Clinical Significance in a Series of 74 Patients. Lupus 2004, 13, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigun, R.; Goyal, A.; Hariz, A. Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Islet Autoantibodies in Type 1 Diabetes - PMC. Available online: https://www-1ncbi-1nlm-1nih-1gov-1nb5yeidx0f8f.hanproxy.cm-uj.krakow.pl/pmc/articles/PMC10298549/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Kahaly, G.J. Management of Graves Thyroidal and Extrathyroidal Disease: An Update. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczek, A.; Plutecka, H.; Ślusarczyk, M.; Chłoń-Rzepa, G.; Wyska, E. PK/PD Modeling of the PDE7 Inhibitor—GRMS-55 in a Mouse Model of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Oudhia, S.; Lowe, P.; Mager, D. Bridging Clinical Outcomes of Canakinumab Treatment in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis With a Population Model of IL-1β Kinetics. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2012, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, C.; Soy, D.; Ruiz-Esquide, V.; Sanmartí, R.; Huitema, A.D.R. Exposure-Response Modeling of Tocilizumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis Using Continuous Composite Measures and Their Individual Components. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 1710–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earp, J.C.; Dubois, D.C.; Molano, D.S.; Pyszczynski, N.A.; Keller, C.E.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Modeling Corticosteroid Effects in a Rat Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis I: Mechanistic Disease Progression Model for the Time Course of Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Lewis Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 326, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Nolain, P.; Lu, Q.; Paccaly, A.; Iglesias-Rodriguez, M.; John, G.S.; Nivens, C.; Maldonado, R.; Ishii, T.; Choy, E.; et al. Fri0106 Sarilumab and Tocilizumab Receptor Occupancy (Ro), and Effects on C-Reactive Protein (Crp) Levels, in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (Ra). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, K.D.L.; Alves, I.A.; Novoa, D.M.A. PBPK Modeling as an Alternative Method of Interspecies Extrapolation That Reduces the Use of Animals: A Systematic Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 31, 102–126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Merdy, M.; Mullin, J.; Lukacova, V. Development of PBPK Model for Intra-Articular Injection in Human: Methotrexate Solution and Rheumatoid Arthritis Case Study. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2021, 48, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umehara, K.; Huth, F.; Jin, Y.; Schiller, H.; Aslanis, V.; Heimbach, T.; He, H. Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Assessments of Ruxolitinib, a Dual Substrate of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, Using a Verified Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Model to Support Regulatory Submissions. Drug Metab. Pers. Ther. 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mager, D.E.; Wyska, E.; Jusko, W.J. Diversity of Mechanism-Based Pharmacodynamic Models. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, R.; O’Reilly, R.A.; Levy, G. Kinetics of Pharmacologic Effects in Man: The Anticoagulant Action of Warfarin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1969, 10, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayneka, N.L.; Garg, V.; Jusko, W.J. Comparison of Four Basic Models of Indirect Pharmacodynamic Responses. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1993, 21, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhof, M.; de Jongh, J.; De Lange, E.C.M.; Della Pasqua, O.; Ploeger, B.A.; Voskuyl, R.A. Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling: Biophase Distribution, Receptor Theory, and Dynamical Systems Analysis. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 357–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.N.; Jusko, W.J. Transit Compartments versus Gamma Distribution Function to Model Signal Transduction Processes in Pharmacodynamics. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, D.E. Target-Mediated Drug Disposition and Dynamics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyar, V.S.; Jusko, W.J. Transitioning from Basic toward Systems Pharmacodynamic Models: Lessons from Corticosteroids. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 414–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, D.; Upton, R. Basic Concepts in Population Modeling, Simulation, and Model-Based Drug Development. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2012, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Aarons, L.; Coates, P. A Pharmacokinetic Model for Tenidap in Normal Volunteers and Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, N.; Grange, S.; Woodworth, T. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Tocilizumab in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 50, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papasouliotis, O.; Yalkinoglu, Ö.; Golob, M.; Willen, D.; Girard, P. AB0529 Population Pharmacokinetics of Atacicept in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1077–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Biliouris, K.; Naik, H.; Rabah, D.; Stevenson, L.; Shen, C.; Nestorov, I.A.; Lesko, L.J.; Trame, M.N. A Clinical Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model for BIIB059, a Monoclonal Antibody for the Treatment of Systemic and Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2020, 47, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Shoji, S.; Beebe, J. Pharmacokinetics and C-Reactive Protein Modelling of Anti-Interleukin-6 Antibody (PF-04236921) in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Autoimmune Disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2059–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Rahman, M.U.; Davis, H.M.; Zhou, H. Population Approach for Exposure-Response Modeling of Golimumab in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribba, B.; Grimm, H.P.; Agoram, B.; Davies, M.R.; Gadkar, K.; Niederer, S.; van Riel, N.; Timmis, J.; van der Graaf, P.H. Methodologies for Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Models: Design and Estimation. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2017, 6, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliouris, K.; Nestorov, I.; Naik, H.; Dai, D.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Q.; Pellerin, A.; Rabah, D.; Lesko, L.J.; Trame, M.N. A Pre-Clinical Quantitative Model Predicts the Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of an Anti-BDCA2 Monoclonal Antibody in Humans. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2018, 45, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, F.R.; Chaplain, M.A.J.; Eftimie, R. Quantitative Predictive Modelling Approaches to Understanding Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Brief Review. Cells 2020, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cerdá, M.L.; Irurzun-Arana, I.; González-Garcia, I.; Hu, C.; Zhou, H.; Vermeulen, A.; Trocóniz, I.F.; Gómez-Mantilla, J.D. Towards Patient Stratification and Treatment in the Autoimmune Disease Lupus Erythematosus Using a Systems Pharmacology Approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 94, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomingdale, P.; Nguyen, V.A.; Niu, J.; Mager, D.E. Boolean Network Modeling in Systems Pharmacology. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2018, 45, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaberi-Douraki, M.; Liu, S.W. (Shalon); Pietropaolo, M.; Khadra, A. Autoimmune Responses in T1DM: Quantitative Methods to Understand Onset, Progression, and Prevention of Disease. Pediatr. Diabetes 2014, 15, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.F.; Muse, R.; Podichetty, J.T.; Burton, J.; David, S.; Lang, P.; Schmidt, S.; Romero, K.; O’Doherty, I.; Martin, F.; et al. Disease Progression Joint Model Predicts Time to Type 1 Diabetes Onset: Optimizing Future Type 1 Diabetes Prevention Studies. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.; Smith, N.; Ciupe, S.; Zou, W.; Omenn, G.S.; Pietropaolo, M.; Nelson, P.; Smith, N.; Ciupe, S.; Zou, W.; et al. Modeling Dynamic Changes in Type 1 Diabetes Progression: Quantifying $\beta$-Cell Variation after the Appearance of Islet-Specific Autoimmune Responses. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2009, 6, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, D.R. Models for Disease Progression: New Approaches and Uses. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 92, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; DuBois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Modeling Sex Differences in Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Disease Progression Effects of Naproxen in Rats with Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017, 45, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Dubois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Modeling Sex Differences in Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Dexamethasone in Arthritic Rats. [CrossRef]

- Lon, H.-K.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Q.; DuBois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Disease Progression Model for Effect of Etanercept in Lewis Rats with Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczek, A.; Pociecha, K.; Plutecka, H.; Ślusarczyk, M.; Chłoń-Rzepa, G.; Wyska, E. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of a New Purine-2,6-Dione Derivative in Rodents with Experimental Autoimmune Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, I.-H.; Lee, B.-Y.; Chae, J.-W.; Song, G.Y.; Kang, W.; Kwon, K.-I. Development of a Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic/Disease Progression Model in NC/Nga Mice for Development of Novel Anti-Atopic Dermatitis Drugs. Xenobiotica 2014, 44, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lon, H.-K.; Dubois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J.; Edu, W. Population Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic-Disease Progression Model for Effects of Anakinra in Lewis Rats with Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2011, 38, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earp, J.C.; Pyszczynski, N.A.; Molano, D.S.; Jusko, W.J. Pharmacokinetics of Dexamethasone in a Rat Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2008, 29, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earp, J.C.; DuBois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Quantitative Dynamic Models of Arthritis Progression in the Rat. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; DuBois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Pyszczynski, N.A.; Jusko, W.J. Fifth-Generation Model for Corticosteroid Pharmacodynamics: Application to Steady-State Receptor Down-Regulation and Enzyme Induction Patterns during Seven-Day Continuous Infusion of Methylprednisolone in Rats. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2002, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earp, J.C.; Dubois, D.C.; Molano, D.S.; Pyszczynski, N.A.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Modeling Corticosteroid Effects in a Rat Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis II: Mechanistic Pharmacodynamic Model for Dexamethasone Effects in Lewis Rats with Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 326, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; DuBois, D.C.; Song, D.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J.; Chen, X. Modeling Combined Immunosuppressive and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Dexamethasone and Naproxen in Rats Predicts the Steroid-Sparing Potential of Naproxen. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017, 45, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, X.; Jusko, W.J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W. Minimal Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (mPBPK) Model for a Monoclonal Antibody against Interleukin-6 in Mice with Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2016, 43, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-Y.; Lon, H.-K.; Wang, Y.-L.; DuBois, D.C.; Almon, R.R.; Jusko, W.J. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Toxicities of Methotrexate in Healthy and Collagen-Induced Arthritic Rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2013, 34, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselmayer, P.; Camps, M.; Liu-Bujalski, L.; Morandi, F.; Head, J.; Zimmerli, S.; Bruns, L.; Bender, A.; Schroeder, P.; Grenningloh, R. THU0275 Pharmacodynamic Modeling of BTK Occupancy versus Efficacy in RA and SLE Models Using The Novel Specific BTK Inhibitor M2951. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczek, A.; Pociecha, K.; Ślusarczyk, M.; Chłoń-Rzepa, G.; Baś, S.; Mlynarski, J.; Więckowski, K.; Zadrożna, M.; Nowak, B.; Wyska, E. Comparative Assessment of the New PDE7 Inhibitor – GRMS-55 and Lisofylline in Animal Models of Immune-Related Disorders: A PK/PD Modeling Approach. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczek, A.; Pomierny, B.; Wyska, E.; Jusko, W.J. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Assessment of Selective Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors in a Mouse Model of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2022, 381, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselmayer, P.; Camps, M.; Liu-Bujalski, L.; Nguyen, N.; Morandi, F.; Head, J.; O’Mahony, A.; Zimmerli, S.C.; Bruns, L.; Bender, A.T.; et al. Efficacy and Pharmacodynamic Modeling of the BTK Inhibitor Evobrutinib in Autoimmune Disease Models. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 2888–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Deng, Y.; Wright, M.R.; Hop, C.E.C.A. Exposure-Effect Relationships in Established Rat Adjuvant-Induced and Collagen-Induced Arthritis: A Translational Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Analysis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 369, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowty, M.E.; Jesson, M.I.; Ghosh, S.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.M.; Krishnaswami, S.; Kishore, N. Preclinical to Clinical Translation of Tofacitinib, a Janus Kinase Inhibitor, in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014, 348, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Scheerens, H.; Davis Jr, J.; Deng, R.; Fischer, S.; Woods, C.; Fielder, P.; Stefanich, E. Translational Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of an FcRn-Variant Anti-CD4 Monoclonal Antibody From Preclinical Model to Phase I Study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lledo-Garcia, R.; Dixon, K.; Shock, A.; Oliver, R. Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modelling of the Anti-FcRn Monoclonal Antibody Rozanolixizumab: Translation from Preclinical Stages to the Clinic. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2022, 11, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liric Rajlic, I.; Guglieri-Lopez, B.; Rangoonwala, N.; Ivaturi, V.; Van, L.; Mori, S.; Wipke, B.; Burdette, D.; Attarwala, H. Translational Kinetic-Pharmacodynamics of mRNA-6231, an Investigational mRNA Therapeutic Encoding Mutein Interleukin-2. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudal, S.; Bissantz, C.; Caruso, A.; David-Pierson, P.; Driessen, W.; Koller, E.; Krippendorff, B.-F.; Lechmann, M.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Paehler, A.; et al. Translating Pharmacology Models Effectively to Predict Therapeutic Benefit. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 1604–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Garcia, A.; Baverel, P.; Bottino, D.; Dolton, M.; Feng, Y.; González-García, I.; Kim, J.; Robey, S.; Singh, I.; Turner, D.; et al. A Comprehensive Regulatory and Industry Review of Modeling and Simulation Practices in Oncology Clinical Drug Development. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2023, 50, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Velde, F.; Mouton, J.W.; de Winter, B.C.M.; van Gelder, T.; Koch, B.C.P. Clinical Applications of Population Pharmacokinetic Models of Antibiotics: Challenges and Perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Y.L.; Santiago, L.; Wang, B.; Kuruvilla, D.; Wang, S.; Tummala, R.; Roskos, L. Exposure–Response Analysis for Selection of Optimal Dosage Regimen of Anifrolumab in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5854–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, C.M.T.; Sagcal-Gironella, A.C.P.; Fukuda, T.; Brunner, H.I.; Vinks, A.A. Development of Population PK Model with Enterohepatic Circulation for Mycophenolic Acid in Patients with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almquist, J.; Kuruvilla, D.; Mai, T.; Tummala, R.; White, W.I.; Tang, W.; Roskos, L.; Chia, Y.L. Nonlinear Population Pharmacokinetics of Anifrolumab in Healthy Volunteers and Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 1106–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Sherwin, C.M.; Yu, T.; Yellepeddi, V.K.; Brunner, H.I.; Vinks, A.A. Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Therapies for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 8, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimelow, R.; Gillespie, W.R.; van Maurik, A. Population Model-Based Analysis of the Memory B-Cell Response Following Belimumab Therapy in the Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, C.; Magnusson, M.O.; Vajjah, P.; Oliver, R.; Zamacona, M. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Response for Dapirolizumab Pegol From a Phase 2b Trial in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsiu, M.; Yalkinoglu, Ö.; Farrell, C.; Girard, P.; Vazquez-Mateo, C.; Papasouliotis, O. Population Pharmacokinetics of Atacicept in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Analysis of Three Clinical Trials. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Pharmacokinetics Model and Initial Dose Optimization of Tacrolimus in Children and Adolescents with Lupus Nephritis Based on Real-World Data. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Grange, S.; Frey, N. Exposure-Exposure Relationship of Tocilizumab, an Anti–IL-6 Receptor Monoclonal Antibody, in a Large Population of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 53, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, D.; Zhou, H.; Peck, C.C.; Lee, H. Population Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) Modeling of Etanercept in Patients with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA) Using a Dichotomous Clinical Endpoint. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 77, P92–P92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, J.; Wiese, M.D.; Proudman, S.M.; Foster, D.J.R.; Upton, R.N. A Population Model of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity during Treatment with Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine and Hydroxychloroquine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Su, Y.; Paccaly, A.; Kanamaluru, V. Population Pharmacokinetics of Sarilumab in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xu, C.; Paccaly, A.; Kanamaluru, V. Population Pharmacokinetic–Pharmacodynamic Relationships of Sarilumab Using Disease Activity Score 28-Joint C-Reactive Protein and Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 59, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Eudy-Byrne, R.J.; Mondick, J.; Knebel, W.; Jayadeva, G.; Liesenfeld, K.-H. Population Pharmacokinetics of Adalimumab Biosimilar Adalimumab-Adbm and Reference Product in Healthy Subjects and Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis to Assess Pharmacokinetic Similarity. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 2274–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, J.; Kaibara, A.; Shibata, M.; Kaneko, Y.; Izutsu, H.; Nishimura, T. Exposure–Response Modeling of Peficitinib Efficacy in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yao, Q.; Chen, W.; Yin, J.; Hou, S.; Tian, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Zhou, T.; et al. Population PK/PD Model of Tacrolimus for Exploring the Relationship between Accumulated Exposure and Quantitative Scores in Myasthenia Gravis Patients. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Lee, T.-I.; Zhu, M.; Ma, P. Prediction of Belimumab Pharmacokinetics in Chinese Pediatric Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Drugs RD 2021, 21, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Kimko, H.; Wang, B.; Cimbora, D.; Katz, E.; Rees, W.A. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Inebilizumab in Subjects with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders, Systemic Sclerosis, or Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevic, S.J.; Green, T.P.; Clowse, M.E.B.; Eudy, A.M.; Schanberg, L.E.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M. Pharmacokinetics of Hydroxychloroquine in Pregnancies with Rheumatic Diseases. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano-Aguilar, M.; Reséndiz-Galván, J.E.; Medellín-Garibay, S.E.; Milán-Segovia, R.D.C.; Martínez-Martínez, M.U.; Abud-Mendoza, C.; Romano-Moreno, S. Population Pharmacokinetics of Mycophenolic Acid in Mexican Patients with Lupus Nephritis. Lupus 2020, 29, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, A.; Stodtmann, S.; Friedel, A.; Mohamed, M.-E.F.; Othman, A.A. Pharmacokinetics of Upadacitinib in Healthy Subjects and Subjects With Rheumatoid Arthritis, Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, or Atopic Dermatitis: Population Analyses of Phase 1 and 2 Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 60, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, S.E.; Strik, A.S.; Van Selm, J.C.; Löwenberg, M.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; D’Haens, G.R.; Mathôt, R.A. Explaining Interpatient Variability in Adalimumab Pharmacokinetics in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Ther. Drug Monit. 2018, 40, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Roy, A.; Murthy, B. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Response Relationship of Intravenous and Subcutaneous Abatacept in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 59, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpalu, D.E.; Frederick, B.; Nnane, I.P.; Yao, Z.; Shen, F.; Ort, T.; Fink, D.; Dogmanits, S.; Raible, D.; Sharma, A.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Immunogenicity, Safety, and Tolerability of JNJ-61178104, a Novel Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Interleukin-17A Bispecific Antibody, in Healthy Subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 59, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleiman, A.A.; Minocha, M.; Khatri, A.; Pang, Y.; Othman, A.A. Population Pharmacokinetics of Risankizumab in Healthy Volunteers and Subjects with Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Integrated Analyses of Phase I–III Clinical Trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleiman, A.A.; Khatri, A.; Minocha, M.; Othman, A.A. Population Pharmacokinetics of the Interleukin-23 Inhibitor Risankizumab in Subjects with Psoriasis and Crohn’s Disease: Analyses of Phase I and II Trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheetz, M.H.; Konig, M.F.; Robinson, P.C.; Sparks, J.A.; Kim, A.H.J. A Pharmacokinetics-Informed Approach to Navigating Hydroxychloroquine Shortages in Patients With Rheumatic Disease During the COVID-19 Pandemic. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, J.; S Purohit, V.; Huh, Y.; Banfield, C.; Nicholas, T. Evolution of Ritlecitinib Population Pharmacokinetic Models During Clinical Drug Development. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 62, 1765–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitcollin, A.; Leuret, O.; Tron, C.; Lemaitre, F.; Verdier, M.-C.; Paintaud, G.; Bouguen, G.; Willot, S.; Bellissant, E.; Ternant, D. Modeling Immunization To Infliximab in Children With Crohn’s Disease Using Population Pharmacokinetics: A Pilot Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1745–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, L.; Hang, Y.; Othman, A.A.; Mehta, D.; Amaravadi, L.; Nestorov, I.; Tran, J.Q. Population PK–PD Analyses of CD25 Occupancy, CD56bright NK Cell Expansion, and Regulatory T Cell Reduction by Daclizumab HYP in Subjects with Multiple Sclerosis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klünder, B.; Mittapalli, R.K.; Mohamed, M.-E.F.; Friedel, A.; Noertersheuser, P.; Othman, A.A. Population Pharmacokinetics of Upadacitinib Using the Immediate-Release and Extended-Release Formulations in Healthy Subjects and Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Analyses of Phase I–III Clinical Trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasouliotis, O.; Mitchell, D.; Girard, P.; Dangond, F.; Dyroff, M. Determination of a Clinically Effective Evobrutinib Dose: Exposure–Response Analyses of a Phase II Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis Study. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 2888–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, J.P.R.; Gao, X.; Kleijn, H.J.; Bellanti, F.; Pelto, R. Eculizumab Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in Patients With Generalized Myasthenia Gravis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 696385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, Y.L.; Tummala, R.; Mai, T.H.; Rouse, T.; Streicher, K.; White, W.I.; Morand, E.F.; Furie, R.A. Relationship Between Anifrolumab Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Efficacy in Patients With Moderate to Severe Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Hu, P. A Population Pharmacokinetic Study to Accelerate Early Phase Clinical Development for a Novel Drug, Teriflunomide Sodium, to Treat Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 136, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendt, S.L.; Ranjan, A.; Møller, J.K.; Schmidt, S.; Knudsen, C.B.; Holst, J.J.; Madsbad, S.; Madsen, H.; Nørgaard, K.; Jørgensen, J.B. Cross-Validation of a Glucose-Insulin-Glucagon Pharmacodynamics Model for Simulation Using Data From Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.; Yu, J.; Chinn, L.; Prohn, M.; Huisman, J.; Matzuka, B.; Hanley, W.; Tuckwell, K.; Quartino, A. Population Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy Exposure-Response Analysis, and Model-Based Meta-Analysis of Fenebrutinib in Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, N.; Brstilo, L.; Sancho-Araiz, A.; Molina, M.; Savransky, A.; Roffé, G.; Sanz, M.; Tenembaum, S.; Katsicas, M.M.; Trocóniz, I.F.; et al. Population Pharmacodynamic Modelling of the CD19+ Suppression Effects of Rituximab in Paediatric Patients with Neurological and Autoimmune Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, D.-D.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.-P. Population Pharmacokinetics Model and Initial Dose Optimization of Tacrolimus in Children and Adolescents with Lupus Nephritis Based on Real-World Data. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, J.; Shibata, M.; Kaibara, A.; Kaneko, Y.; Izutsu, H.; Nishimura, T. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Peficitinib in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 2014–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, S.; Dowty, M.E.; Menon, S.; Gupta, P.; Krishnaswami, S. Application of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling to Predict Drug Exposure and Support Dosing Recommendations for Potential Drug-Drug Interactions or in Special Populations: An Example Using Tofacitinib. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 60, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, H. Development of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Predict Disease-Mediated Therapeutic Protein–Drug Interactions: Modulation of Multiple Cytochrome P450 Enzymes by Interleukin-6. AAPS J. 2016, 18, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machavaram, K.K.; Almond, L.M.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Gardner, I.; Jamei, M.; Tay, S.; Wong, S.; Joshi, A.; Kenny, J.R. A Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling Approach to Predict Disease–Drug Interactions: Suppression of CYP3A by IL-6. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 94, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, F.; Asiri, A.M.; Zamir, A.; Rasool, M.F.; Alali, A.S.; Alsanea, S.; Walbi, I.A. Predicting Hydroxychloroquine Clearance in Healthy and Diseased Populations Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Approach. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellepeddi, V.K.; Baker, O.J. Predictive Modeling of Aspirin-triggered Resolvin D1 Pharmacokinetics for the Study of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2019, 6, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coto-Segura, P.; Segú-Vergés, C.; Martorell, A.; Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Jorba, G.; Junet, V.; Guerri, F.; Daura, X.; Oliva, B.; Cara, C.; et al. A Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Model for Certolizumab Pegol Treatment in Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbas-Martinez, V.; Asin-Prieto, E.; Parra-Guillen, Z.P.; Troconiz, I.F. A Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Model for the Key Interleukins Involved in Crohn’s Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 372, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcome to the Population Approach Group in Europe. Available online: https://www.page-meeting.org/default.asp?abstract=10301 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Ghayoor, A.; Kohan, H.G. Revolutionizing Pharmacokinetics: The Dawn of AI-Powered Analysis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 27, 12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, M.; Bies, R.; Ramanathan, M. Machine Learning in Pharmacometrics: Opportunities and Challenges. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 1482–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankevičiūtė, K.; Woillard, J.-B.; Peck, R.W.; Marquet, P.; van der Schaar, M. Bridging the Worlds of Pharmacometrics and Machine Learning. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 62, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Munafo, A.; Ben-Amor, A.-F.; Roy, S.; Girard, P.; Terranova, N. Predicting Disease Activity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Explainable Machine-Learning Approach in the Mavenclad Trials. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2022, 11, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Jia, Y.; Kan, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Shao, S.; Ni, B.; Tang, J. Identification of ADAM23 as a Potential Signature for Psoriasis Using Integrative Machine-Learning and Experimental Verification. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.C.; Augustin, F.; Huard, J.; Friedrich, C.M. Using Machine Learning Surrogate Modeling for Faster QSP VP Cohort Generation. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Androulakis, I.P.; Bonate, P.; Cheng, L.; Helikar, T.; Parikh, J.; Rackauckas, C.; Subramanian, K.; Cho, C.R. ; Working Group Two Heads Are Better than One: Current Landscape of Integrating QSP and Machine Learning : An ISoP QSP SIG White Paper by the Working Group on the Integration of Quantitative Systems Pharmacology and Machine Learning. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2022, 49, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research, C. for D.E. and Division of Pharmacometrics. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cder-offices-and-divisions/division-pharmacometrics (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Ma, L.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.; Yim, S.; Doddapaneni, S.; Sahajwalla, C.G.; Wang, Y.; Ji, P. Clinical Endpoint Sensitivity in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Modeling and Simulation. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2014, 41, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics | European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/research-and-development/scientific-guidelines/clinical-pharmacology-pharmacokinetics (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Modeling of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics with Application to Cancer and Arthritis.

| Biomarker | AIDs | Application | Specificity | Ref. |

| Rheumatoid factor (RF) | RA | Disease diagnosis | Can be present in other diseases or in healthy individuals | [26] |

| Anti-CCP antibody | RA | Disease classification, prognosis, and staging | High specificity | [26] |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) | SLE | Disease classification, prognosis, and staging | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [25] |

| Anti-ssDNA antibody | SLE | Disease classification, assessment of activity | Less specific than anti-dsDNA antibody | [25] |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody | SLE | Disease classification, disease monitoring, particularly kidney status | Specific to SLE | [25] |

| Anti-Sm antibody | SLE | Disease classification, assessment of lymph node status | Specific to SLE | [25] |

| Anti-C1q antibodies | SLE | Disease monitoring, particularly kidney status | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [25] |

| C3 and C4 | SLE | Disease classification, monitoring of disease activity | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [25] |

| Anti-β2GP1 antibody | APS | Disease diagnosis, risk of thrombotic complications | Low specificity | [27] |

| aCL antibody | APS | Disease diagnosis | Low specificity | [27] |

| Lupus anticoagulant (LA) | APS | Disease diagnosis, risk of thrombotic complications | High specificity | [27] |

| Anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies | SjS | Diagnosis, pregnancy complication prognosis | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [28] |

| Anti-Scl-70 antibody | SS | Assessment of risk for complications | High specificity | [29] |

| Autoantibodies to insulin (IAA) | T1D | Disease diagnosis, pathological analysis | Specific for patients not treated with exogenous insulin | [30] |

| Tyrosine phosphatase-like protein IA-2 (IA-2A) | T1D | Disease diagnosis, pathological analysis | High specificity | [30] |

| Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) | T1D | Disease diagnosis, pathological analysis | May also occur in other autoimmune diseases | [30] |

| Zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8A) | T1D | Disease diagnosis, pathological analysis | High specificity | [30] |

| Anti-TSHR antibodies | GD | Disease classification, monitoring of disease activity | High specificity | [31] |

| Tumour Necrosis factor (TNF)α | RA, AIH | Inflammatory marker | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [32] |

| Interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, Interferon (IFN)γ, IL-17A | RA, AIH | Inflammatory marker | May also occur in other autoimmune inflammatory diseases | [32,33,34,35] |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT), Aspartate transaminase (AST), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) | AIH, PSC, PBC | Liver damage biomarkers | Non-specific, used in various liver diseases | [32,33,34] |

| CRP | RA | Marker of inflammation | Non-specific, used in many inflammatory conditions | [36] |

| ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate) | RA | Marker of inflammation | Non-specific, used in various inflammatory diseases | [34] |

| Abbreviation (Expansion) | Autoimmune diseases in which it is used | Short description |

| Paw Swelling | RA (animal models) | Measures inflammation in pre-clinical models of RA, often used to assess anti-inflammatory drug efficacy |

| BMD (Bone Mineral Density) | RA, SLE | Measures bone strength, used to assess effects of chronic inflammation and treatments on bone health |

| IgG (Immunoglobulin G) | SLE, RA, other AIDs | Measures antibody levels in blood, indicating immune system function and autoantibody presence |

| SRI(4) (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index) | SLE | Composite index assessing improvements in disease activity in SLE patients |

| BICLA (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group-based Composite Lupus Assessment) | SLE | Composite SLE activity measure integrating multiple organ systems |

| DAS28 (Disease Activity Score - 28 joints) | RA | Quantifies disease activity by counting swollen/tender joints and inflammatory markers |

| HAQ (Health Assessment Questionnaire) | RA, SLE | Measures physical function and disability in patients |

| Global Pain Score | RA, SLE, other AIDs | Subjective measure of overall pain intensity |

| SDAI (Simplified Disease Activity Index) | RA | Composite score measuring RA disease activity |

| CDAI (Clinical Disease Activity Index) | RA | Clinical score measuring RA activity based on affected joint counts and other assessments |

| HAQ-DI (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index) | RA | Detailed version of HAQ, measuring disability across multiple functional domains |

| ACR20/50/70 (American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70 criteria) | RA | Criteria representing 20%, 50%, or 70% improvement in RAs symptoms |

| DAS28-CRP (Disease Activity Score (28 joints) with CRP) | RA | Variation of DAS28 using CRP levels instead of ESR |

| 21-IFNGS (21-gene type I interferon gene signature) | SLE | Reflects activity of the type I interferon pathway, used in SLA to measure immune dysregulation |

| Authors, year of publication, Ref. | Medication (mechanism of action) | Disease | Modeling approach | Main conclusions |

| Earp, Dubois, Molano, Pyszczynski, Keller, et al., 2008, [35] | DEX (corticosteroid) | RA | PK/PD, DisP | The model accurately described disease progression and corticosteroid effects, providing insights into optimal dosing strategies for arthritis treatment |

| Earp, Dubois, Molano, Pyszczynski, Almon, et al., 2008, [72] | DEX | RA | PK/PD, DisP | Lower doses of DEX can effectively suppress key cytokines related to bone erosion, suggesting that optimal dosing can mitigate adverse effects on BMD while controlling inflammation |

| Earp, Pyszczynski, et al., 2008, [69] | DEX | RA | NCA, PopPK | The study concluded that although there was a statistically significant difference in clearance between healthy and arthritic rats, the difference was minor and unlikely to affect DEX disposition meaningfully in arthritic rats |

| Earp et al., 2009, [70] | N/A | RA | Population DisP model | The study concludes that Dark Agouti rats may provide a more dynamic range of edema response than Lewis rats, and the onset time of the disease varies significantly among groups, which should be considered in future studies |

| Lon et al., 2011, [65] | Etanercept (TNFα inhibitor) | RA | PK/PD/DisP | Etanercept modestly reduces paw swelling in CIA rats; potential applicability to other anti-cytokine biologic agents for RA |

| D. Liu et al., 2011, [68] | Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) | RA | PK/PD/DisP | Anakinra had modest effects on paw edema in CIA rats with effective modeling of PK and paw swelling data |

| Song and Jusko, 2011, [64] | DEX (Corticosteroid) | RA | Population PK/PD/DisP | DEX effectively suppressed paw edema in both sexes; comprehensive evaluation of sex differences in PK and PD |

| Haselmayer et al., 2016, [76] | M2951 (BTK inhibitor) | RA, SLE | PK/PD | BTK occupancy of 60% and 80% is associated with RA and SLE progression inhibition |

| X. Li, DuBois, Song, et al., 2017, [73] | DEX and Naproxen (Corticosteroid and NSAID) | RA | PK/PD/DisP | Additive effects when combining DEX and naproxen were observed; the study showed more pronounced beneficial effects in males |

| Świerczek et al., 2020, [77] | Dual PDE4/7 and Lisofylline (PDE4 inhibitor) | RA | PK/PD | Comparative assessment showed potential of a new PDE7 inhibitor in the treatment of AIDs |

| Świerczek et al., 2021, [32] | Dual PDE4/7 inhibitor | AIH | PK/PD | Mechanistic PK/PD models to assess impact of PDE4/7 inhibition on AIH progression were developed confirming the importance of this mechanism for the alleviation of AIH symptoms |

| Świerczek, Pomierny, et al., 2022, [78] | Cilostazole, rolipram, BRL-50481 (selective PDE3, PDE4, PDE7 inhibitors) | AIH | PK/PD | Selective PDE inhibitors were evaluated as potential medications for AIH with rolipram being the most effective |

| Świerczek, Pociecha, et al., 2022, [66] | Dual PDE4/7 inhibitor | MS, RA | DisP | A novel dual PDE4/7 inhibitor showed efficacy in inhibition of MS progression |

| Authors, year of publication, Ref. | Medication (mechanism of action) | Disease | Modeling approach | Main conclusion |

| Zheng et al., 2011, [82] | MTRX1011A (Anti-CD4 mAB, FcRn binding) | RA | PK/PD | N434H mutation did not significantly alter PK/PD relationship; challenges in translating pre-clinical findings to clinical due to variability |

| Dowty et al., 2014, [81] | Tofacitinib (JAK inhibitor) | RA | PK/PD modeling | Efficacy of tofacitinib in RA is driven by its IC50; continuous daily inhibition not required for efficacy |

| Biliouris et al., 2018, [55] | BIIB059 (Anti-BDCA2 mAB) | SLE | PK/PD modeling with allometric scaling | Model predictions matched clinical results; the method aids in selecting safe doses for initial human trials |

| Wong et al., 2019, [80] | Various drugs including indomethacin, methotrexate, etanercept, tofacitinib, and DEX | RA | PK/PD modeling | Improved understanding of dose-efficacy relationships in pre-clinical RA models can enhance translation to clinical settings |

| Lledo-Garcia et al., 2022, [83] | Rozanolixizumab (Anti-FcRn mAB) | Various AIDs | PopPK/PD modeling | Model accurately predicted human responses, aiding in future clinical trial designs |

| Rajlic et al., 2024, [84] | mRNA-6231 (mRNA therapeutic encoding mutein IL-2) | Various AIDs | KPD modeling | Mechanistic KPD model predicted PD response in humans, supporting dose selection for clinical trials |

| Authors, year of publication, Ref. | Drug and mechanism of action | Disease studied | Modeling approach | Conclusion of the study |

| Yim et al., 2005, [97] | Etanercept - TNFα inhibitor | Juvenile RA | PopPK/PD | The popPK model accurately predicted the PK profiles of etanercept in pediatric patients, supporting the feasibility of a once-weekly dosing regimen |

| Frey, Grange, and Wood-worth, 2010, [49] | Tocilizumab - IL-6 receptor antagonist | RA | PopPK | The PK model described the PK characteristics of tocilizumab and identified key covariates, providing insights for optimizing dosing regimens in RA patients |

| Hu et al., 2011, [53] | Golimumab - TNFα inhibitor | RA | PopPK/PD | The model adequately described the PK and PD of golimumab, allowing for broader applications of indirect response models in clinical trials. |

| Sherwin et al., 2012, [89] | Mycophenolate Mofetil (MPM) - Immunosuppressive | SLE | PopPK | The popPK model incorporated complex processes like enterohepatic recycling to aid in individualized dosing for pediatric SLE patients |

| Ait-Oudhia, Lowe, and Mager, 2012, [33] | Canakinumab - IL-1β inhibitor | RA | PopPK/PD | The model linked canakinumab and IL-1β concentrations to clinical outcomes, suggesting that canakinumab improves RA symptoms at 150 mg every 4 weeks |

| Levi, Grange, and Frey, 2013, [96] | Tocilizumab - IL-6 receptor antagonist | RA | PopPK/PD | Tocilizumab effectively reduces DAS28 scores, with a maximum reduction of 5.0 units in males and 4.6 units in females. The presence of neutralizing anti-tocilizumab antibodies did not affect the outcomes |

| Yang et al., 2015, [91] | Multiple drugs - Various immunosuppressants and immunomodulators | SLE | PopPK and PBPK modeling | Individualized and tailored dosing approaches guided by PK algorithms could be safer, more effective, and cost-effective for treating SLE patients |

| Wojciechowski et al., 2015, [98] | Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, HCQ | RA | Population DisP modeling | Population modeling can help identify patients with poor disease trajectories early, potentially leading to more effective personalized treatment strategies |

| Diao et al., 2016, [117] | Daclizumab - IL-2 receptor antagonist | MS | PopPK/PD | The model showed that daclizumab HYP effectively saturates CD25, expands CD56bright NK cells, and reduces Tregs in MS patients, helping optimize treatment strategies. |

| Wendt et al., 2017, [123] | Insulin and glucagon; Regulation of glucose levels | T1D | PopPK/PD | The PD model accurately simulates glucose levels, aiding in diabetes treatment strategy improvement |

| C. Li, Shoji, and Beebe, 2018, [52] | PF-04236921 - Anti-IL-6 mAB | RA, SLE, CD | PopPK and popPK/PD | The integrated popPK and popPK/PD models can simulate PK and PD profiles under various dosing regimens and patient populations, aiding future clinical studies of anti-IL-6 mABs |

| Petitcollin et al., 2018, [116] | Infliximab - TNFα inhibitor | CD | PopPK | The model could detect an increase in infliximab clearance, allowing early detection of immunization to infliximab, potentially improving treatment outcomes in pediatric Crohn’s disease patients |

| Berends et al., 2018, [109] | Adalimumab - TNFα inhibitor | CD | PopPK | The presence of anti-adalimumab antibodies significantly increased the clearance of adalimumab, and the newly developed model provided a better fit for the data compared to existing models. |

| Bastida et al., 2019, [34] | Tocilizumab - IL-6 receptor antagonist | RA | PopPK/PD | The modeling approach confirmed the need for higher serum drug concentrations to normalize clinical variables compared to inflammatory markers |

| Xu et al., 2019, [99] | Sarilumab - IL-6 receptor antagonist | RA | PopPK | The model accurately described the PK of sarilumab, and no dose adjustment is required based on body weight or other demographics. |

| Balevic et al., 2019, [106] | HCQ - Immunomodulatory | Rheumatic Diseases in Pregnancy | PopPK | Pregnancy significantly increases the volume of distribution of HCQ, but does not affect the clearance or the 24-hour area under the concentration-time curve |

| Klünder et al., 2019, [118] | Upadacitinib - JAK1 inhibitor | RA | PopPK | The model was robust and could adequately describe upadacitinib plasma concentration-time profiles, aiding in optimizing dosing regimens for different patient populations |

| Akpalu et al., 2019, [111] | JNJ-61178104 - Bispecific antibody targeting TNF-α and IL-17A | Healthy Subjects | PopPK | JNJ-61178104 was well-tolerated with no apparent safety concerns, and the model can be used to predict PK behavior and optimize dosing regimens by considering significant covariates like body weight and ADA status |

| Suleiman, Minocha, et al., 2019, [112] | Risankizumab - IL-23 inhibitor | Psoriasis | PopPK | The model can be used to predict risankizumab exposure in different patient populations and to optimize dosing regimens for better therapeutic outcomes in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis |

| Suleiman, Khatri, et al., 2019, [113] | Risankizumab - IL-23 inhibitor | Psoriasis, CD | PopPK | The PK of risankizumab was consistent across psoriasis and CD populations after accounting for body weight and baseline albumin differences |

| X. Yao et al., 2019, [122] | Teriflunomide sodium; Modulation of immune response | SLE | PopPK | The PopPK model can support phase II clinical trial design for SLE by accurately describing teriflunomide’s pharmacokinetics |

| Xiaohui Li, Roy, and Murthy, 2019, [110] | Abatacept - T-cell costimulation modulator | RA | PopPK and popPK/PD | The study concluded that abatacept’s effectiveness increases with higher steady-state trough concentrations, with a near-maximal response at 10 mg/mL, supporting the optimization of dosing regimens |

| Nader et al., 2020, [108] | Upadacitinib - JAK1 inhibitor | UC, Atopic Dermatitis, RA, CD | PopPK | The model can be used to predict upadacitinib exposure in different patient populations, aiding in dose selection and optimizing treatment regimens for ulcerative colitis and atopic dermatitis |

| Scheetz et al., 2020, [114] | HCQ - Immunomodulatory | SLE | PopPK | The model helped to predict how long blood HCQ levels would stay above a therapeutic threshold, informing dosing strategies during drug shortages to potentially reduce the risk of disease flares in SLE patients |

| Xiao Chen et al., 2020, [126] | Tacrolimus - Immunosuppressive | LN | PopPK | The popPK model can help optimize tacrolimus dosing in children with SLE, ensuring better treatment outcomes and minimizing side effects |

| Kang et al., 2020, [101] | Adalimumab-adbm - TNFα inhibitor | RA | PopPK | Adalimumab-adbm is pharmacokinetically similar to Humira, and switching from Humira to adalimumab-adbm did not significantly impact adalimumab PK |

| Romano-Aguilar et al., 2020, [107] | Mycophenolic Acid (MPA) - Immunosuppressive | LN | PopPK | Prednisone co-administration significantly increases the clearance of MPA, and this factor should be considered when prescribing MPA to optimize treatment for LN patients |

| Chan et al., 2020, [124] | Fenebrutinib - BTK inhibitor | RA | PopPK, E-R analysis, Model-Based Meta-analysis (MBMA) | MIDD approach with the proposed models can guide dose selection and regimen optimization for fenebrutinib |

| Zhou et al., 2021, [104] | Belimumab - B-lymphocyte stimulator inhibitor | SLE | PopPK | The pharmacokinetics of belimumab were adequately described by the final model, supporting its use in predicting drug exposure in Chinese pediatric patients with SLE |

| Toyoshima, Shibata, et al., 2021, [127] | Peficitinib - JAK inhibitor | RA | PopPK/PD | The models effectively described the treatment response over time, with baseline disease severity correlating with the magnitude of the treatment response, suggesting no need for dose adjustment |

| Toyoshima, Kaibara, et al., 2021, [102] | Peficitinib - JAK inhibitor | RA | Population E-R | The effects of covariates were consistent across both presented models, suggesting their potential application in the development of RA treatments |

| Monteleone et al., 2021, [120] | Eculizumab -Complement component C5 inhibitor | MG | PopPK | The model supports the approved dosing regimen for eculizumab in gMG, ensuring effective and safe treatment |

| Chia et al., 2022, [121] | Anifrolumab - Type I interferon receptor antibody | SLE | PopPK/PD | Higher anifrolumab exposure improves pharmacodynamic responses; the model can optimize dosing regimens |

| Yan et al., 2022, [105] | Inebilizumab - CD19-targeting mAB | Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD), SS, Relapsing MS | PopPK | The pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab were well-described by the proposed model, and the model can be used to predict how inebilizumab behaves in different patient populations, helping to optimize dosing regimens and improve treatment outcomes for AIDs |

| Almquist et al., 2022, [90] | Anifrolumab - Anti-IFNAR1 mAB | SLE | PopPK | The model showed that the clearance rate decreased over time, supporting the recommended dosage of 300 mg every 4 weeks for sustained drug levels |

| Orestis Papa-souliotis et al., 2022, [119] | Evobrutinib - BTK inhibitor | MS | PopPK, popPK/PD | The model may be used in the future to simulate alternative dosing regimens and optimize treatment strategies for patients with RMS, ensuring better clinical outcomes |

| Acharya et al., 2023, [93] | Dapirolizumab Pegol - CD40 ligand inhibitor | SLE | PopPK/PD | Dapirolizumab pegol increased the probability of transitioning from “Nonresponder” to “Responder” status, showing a positive exposure-dependent effect |

| Dimelow, Gil-lespie, and van Maurik, 2023, [92] | Belimumab - B-lymphocyte stimulator inhibitor | SLE | PopPK | The study used a combination of Bayesian and maximum likelihood methods to develop and refine models predicting memory B-cell dynamics in patients with SLE |

| Pitsiu et al., 2023 [94] | Atacicept - B-cell stimulating factor and a proliferation-inducing ligand inhibitor | SLE | PopPK | The model accurately described atacicept concentrations and variability, supporting the selection of suitable doses for further clinical development |

| D. Chen et al., 2023, [103] | Tacrolimus - Immunosuppressive | MG | PopPK/PD | The model aids in optimizing tacrolimus dosing regimens and personalizing treatment for different MG patient subpopulations |

| Morales et al., 2023, [60] | Not specified - Disease progression model for T1D | T1D | DisP model | The developed T1D DisP model accurately reflected data from natural history studies and can be used in clinical trial simulations to optimize trial design |

| Wojciechowski et al., 2023, [115] | Ritlecitinib - JAK inhibitor | Multiple autoimmune and inflammatory diseases | PopPK | The model included significant covariates affecting the clearance and absorption parameters of ritlecitinib, and can be used to inform dosing recommendations in clinical drug development |

| Riva et al., 2023, [125] | Rituximab - CD19 B lymphocyte depletion | Neurological AIDs | PopPK/PD | The model can predict CD19 B lymphocyte depletion over time and may be useful for optimizing rituximab treatment in children. |

| Authors, year of publication, Ref. | Drug and its mechanism of action | Disease studied | Main conclusion |

| Machavaram et al., 2013, [130] | Simvastatin and cyclosporine; IL-6 mediated suppression of CYP3A4 | RA | PBPK models can predict drug-drug interactions in RA patients with elevated IL-6 levels |

| Jiang et al., 2016, [129] | Sirukumab; Anti-IL-6 mAB | RA | The PBPK model captured the modulation effect of IL-6 and sirukumab on CYP enzymes, potentially applicable to other cytokine-neutralizing antibodies |

| Yellepeddi and Baker, 2019, [132] | Aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 (AT-RvD1); Anti-inflammatory | SjS | PBPK modeling can improve drug development and clinical trial design by predicting AT-RvD1 pharmacokinetics |

| Tse et al., 2020, [128] | Tofacitinib; Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor | General analysis | PBPK model using Simcyp is reliable for predicting drug interactions and special populations dosing |

| Alqahtani et al., 2023, [131] | HCQ; Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory | RA, SLE | PBPK model predicted HCQ pharmacokinetics and supported dose adjustments in liver and kidney disease patients |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).