Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Objectives: Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (N/R) is an effective drug for treating COVID-19. However, there is currently a lack of evidence for therapeutic drug monitoring of N/R, which may increase the risk of adverse drug reactions and compromise its efficacy. Methods: In this study, we retrospectively analyzed data from 139 patients in two center who were prescribed N/R. We collected baseline data from all patients and monitored nirmatrelvir and ritonavir concentrations on the third day of medication. We conducted a logistic regression analysis to investigate the relationship between drug concentration and prognosis. We also analyzed the correlations among features and used a random forest model to select significant factors that affect drug exposure. Subsequently, we constructed an XGBoost model to predict drug concentration using the selected features. Results: Our findings indicated that the concentration of N/R could not predict patient outcomes. We also identified potential factors that affect N/R concentration, including estimated glomerular filtration rate, creatine kinase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lymphocytes, and platelet count. Ultimately, the evaluation of the predictive model resulted in a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.717, mean squared error (MSE) of 1.328, root mean squared error (RMSE) of 1.152, and coefficient of determination (R-squared) of 0.779. The prediction model performs well and can provide risk prediction for medication management for N/R, as well as assist in personalized medication. Conclusions: We identified a set of variables that affect the treatment of N/R through therapeutic drug monitoring and established a machine learning model to identify drug risks. This provides a reference for clarifying the significance of therapeutic drug monitoring for N/R treatment and the subsequent development of multivariate prognostic models.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients Enrollment

2.3. Clinical Data and Definitions

2.4. Quantification of Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir Plasma Concentrations

2.4.1. Chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions

2.4.2. Preparation of Reserve Solution and Working Solution

2.4.3. Preparation of Standard Curve and Quality Control

2.4.4. Sample Pretreatment

2.4.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

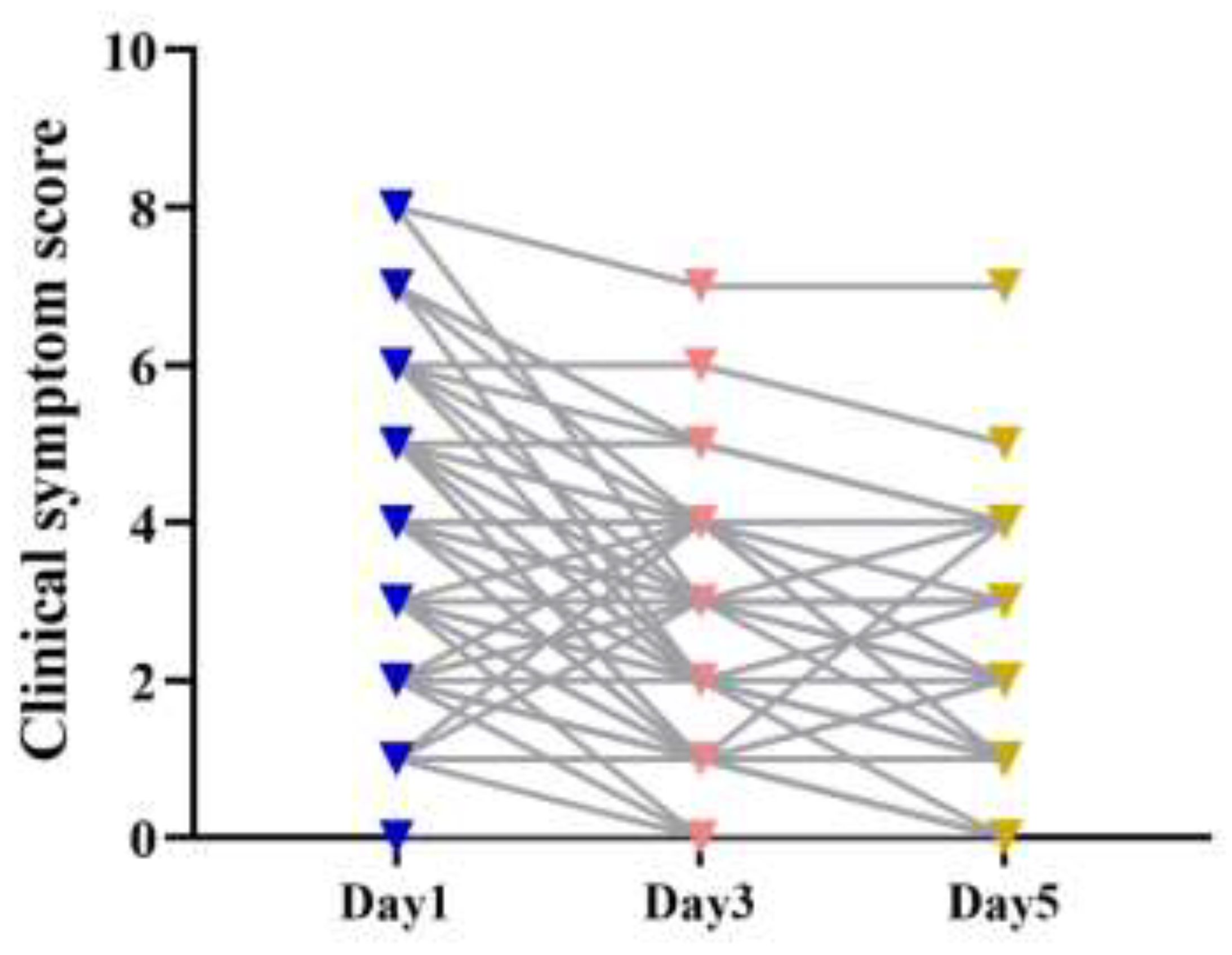

3.2. Changes in Clinical Symptom Score

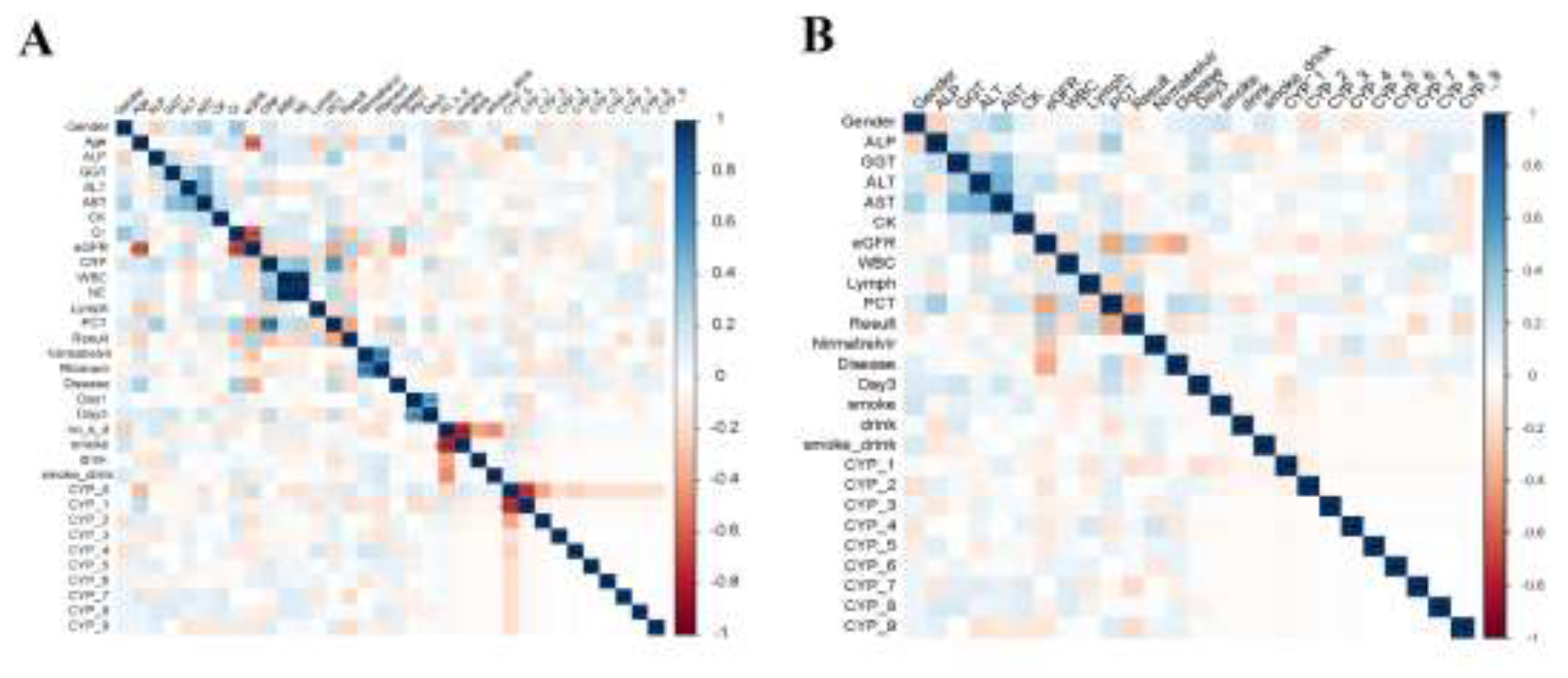

3.3. Feature Correlation Analysis

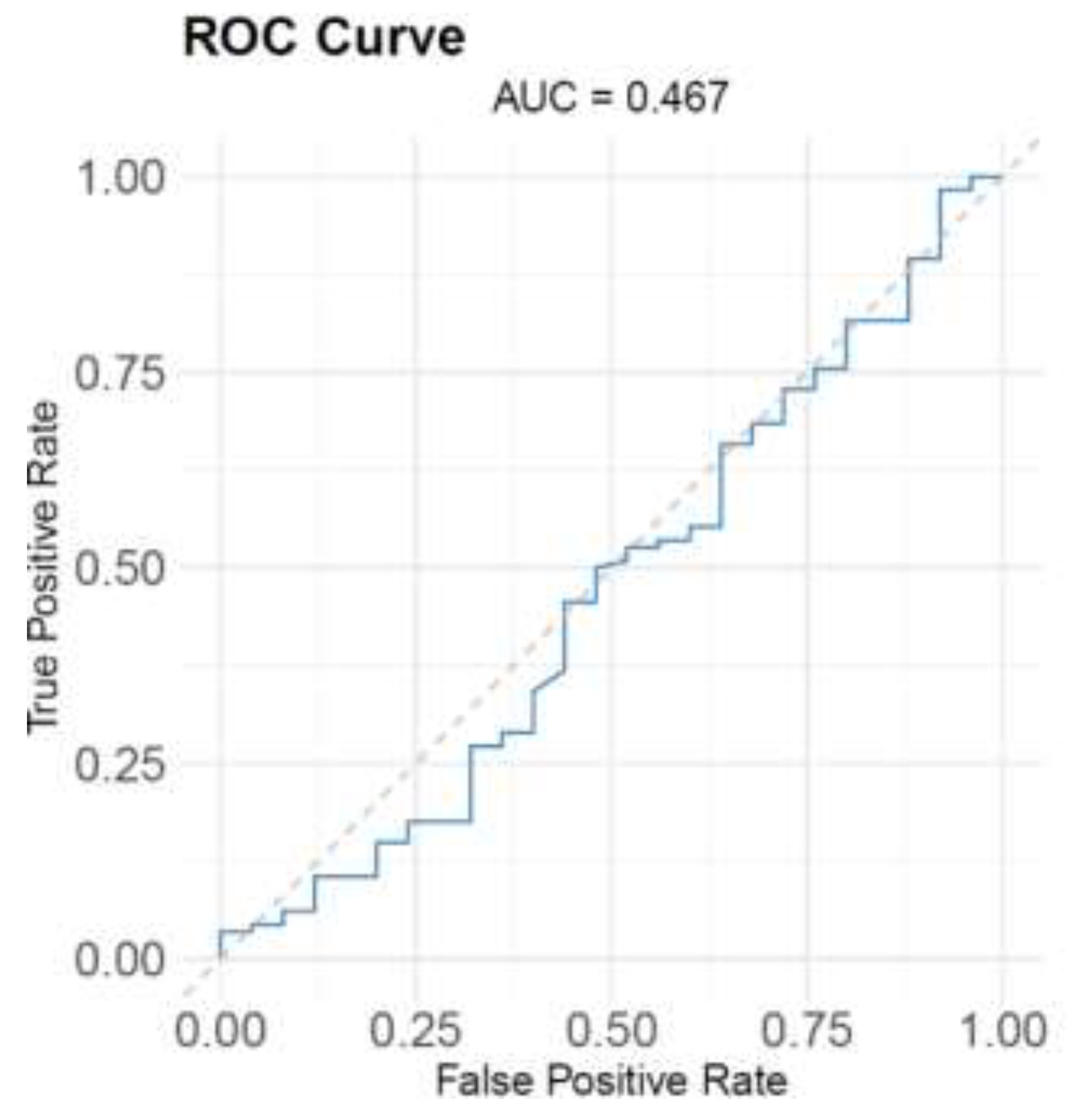

3.4. Nirmatrelvir Blood Concentration Predicts The Prognosis

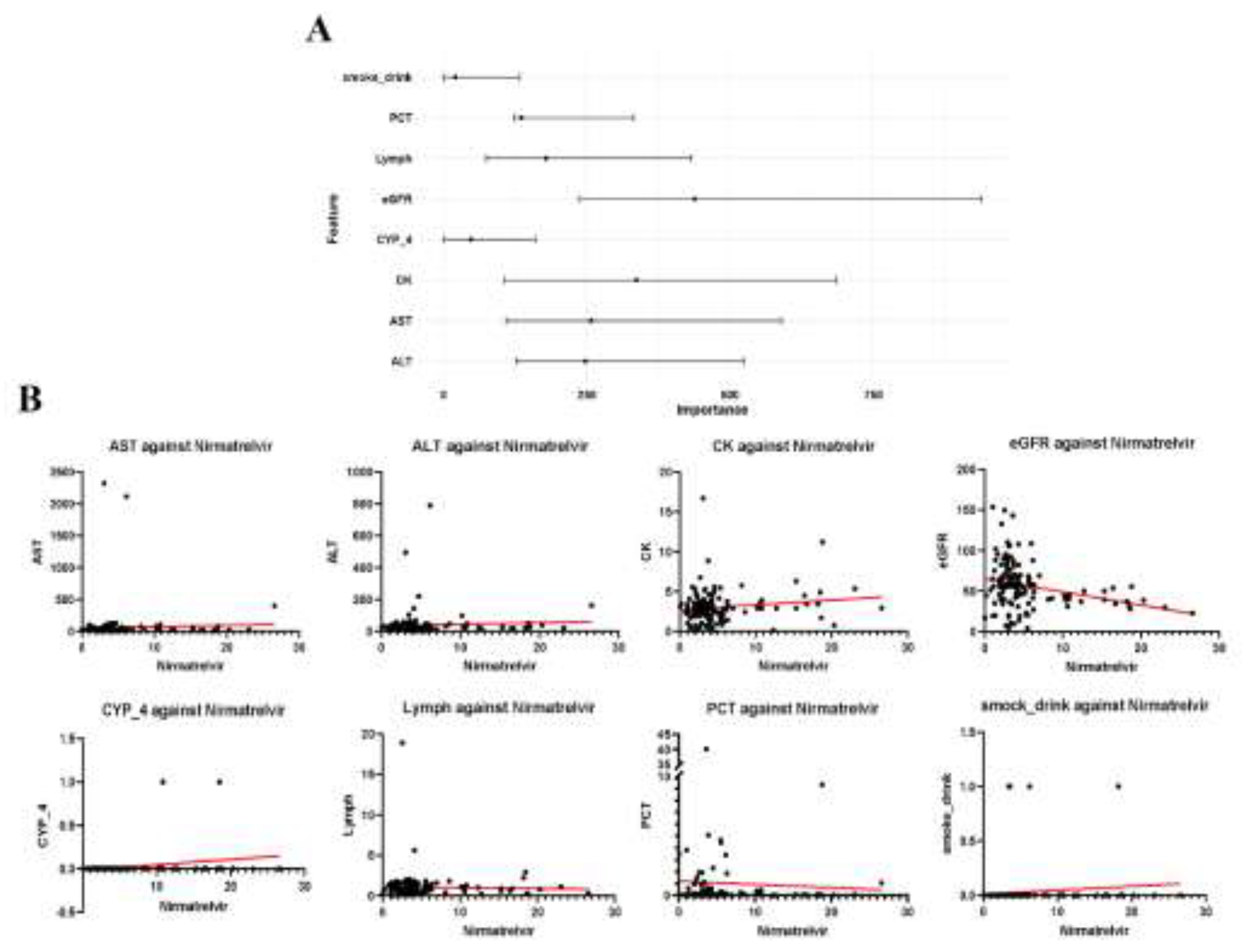

3.5. Feature Selection from Random Forest Model

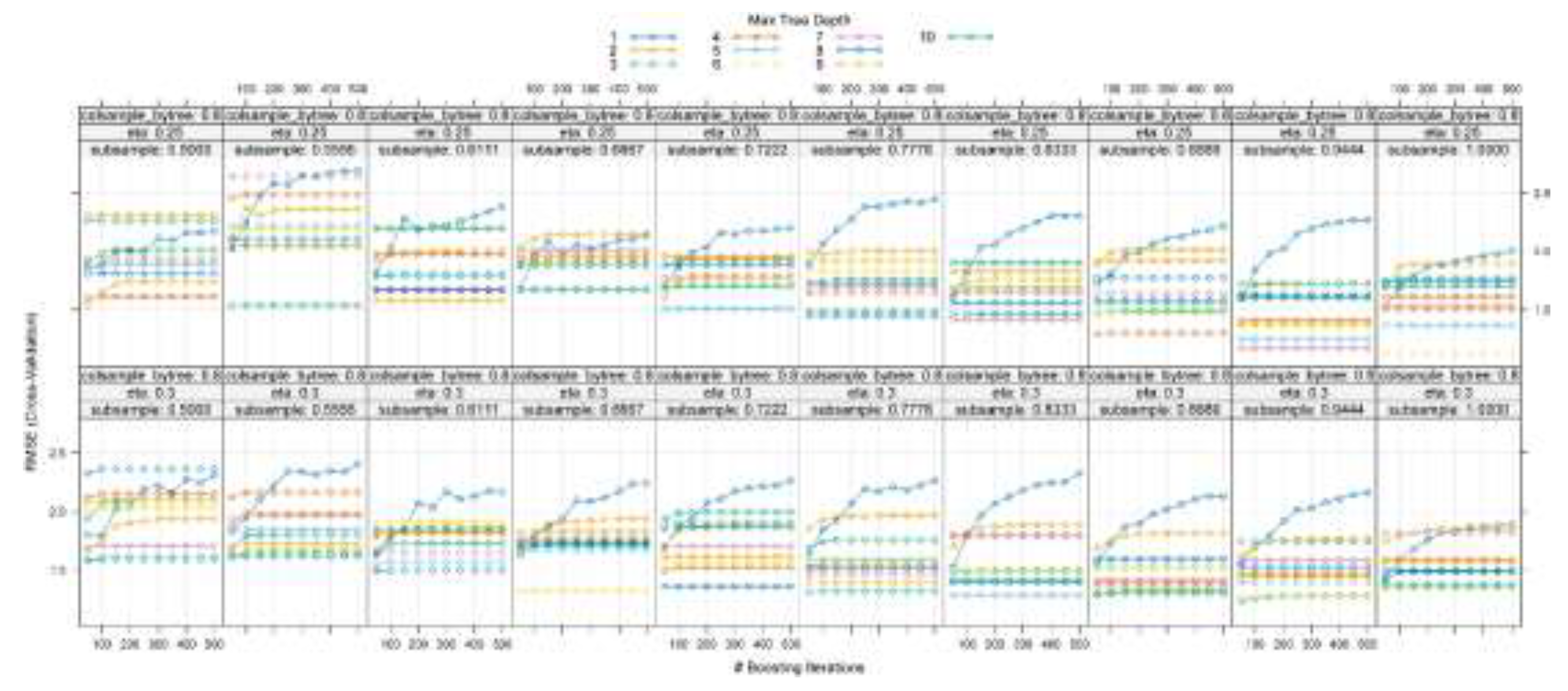

3.6. Learning Curve Analysis for Hyperparameter Optimization

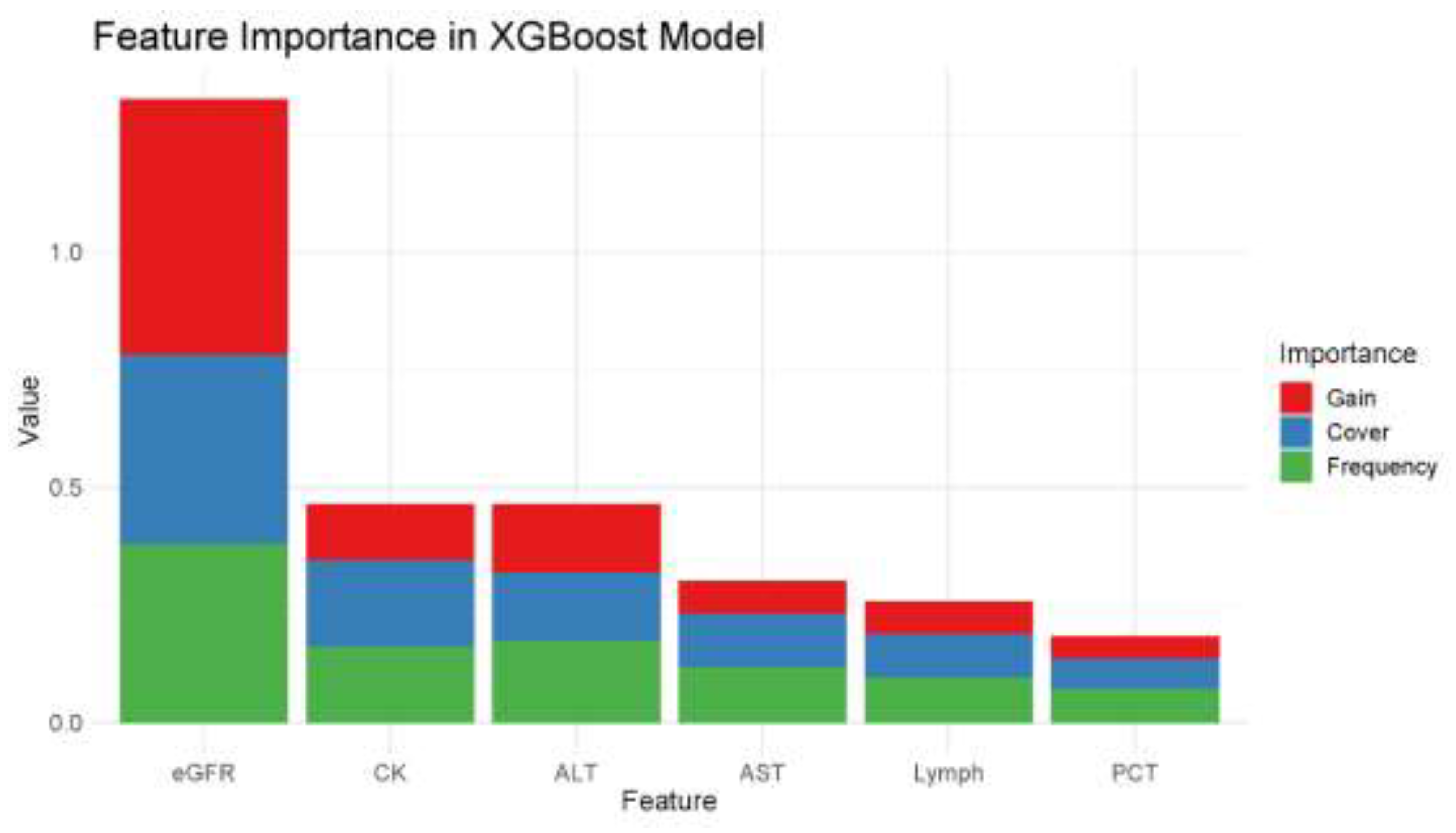

3.7. XGBoost Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elsawah, H.K.; Elsokary, M.A.; Abdallah, M.S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of remdesivir in hospitalized covid-19 patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis including network meta-analysis, Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, B.; Khanijahani, A.; Amani, B.; et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir for covid-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 24, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayk Bernal, A.; Gomes da Silva, M.M.; Musungaie, D.B.; et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burki, T. ; The future of paxlovid for covid-19. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2022, 10, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, B. and Amani, B. Efficacy and safety of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (paxlovid) for covid-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; et al. Effectiveness of paxlovid in reducing severe coronavirus disease 2019 and mortality in high-risk patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Böger, C.R.; Kielstein, J.; et al. Simultaneous quantification of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir by lc-ms/ms in patients treated for covid-19. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 2022, 1212, 123510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, L.J.; Cai, N.F.; et al. Prediction of tacrolimus metabolism and dosage requirements based on cyp3a4 phenotype and cyp3a5(*)3 genotype in chinese renal transplant recipients. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 555–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikis, M. and Cameron, A. Paxlovid (nirmatelvir/ritonavir) and tacrolimus drug-drug interaction in a kidney transplant patient with sars-2-cov infection: A case report. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 1557–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, F.; Budde, K.; Van Gelder, T.; et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring and dosage adjustments of immunosuppressive drugs when combined with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in patients with covid-19. Ther. Drug. Monit. 2023, 45, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.M.R.; Sheida, A.; Taghizadieh, M.; et al. Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir): A new approach to covid-19 therapy? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienvenu, A.L.; Pradat, P.; Plesa, A.; et al. Association between voriconazole exposure and sequential organ failure assessment (sofa) score in critically ill patients. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0260656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Calandra, T.; et al. Intensive care medicine research agenda on invasive fungal infection in critically ill patients. Intensive. Care. Med. 2017, 43, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.S. and Lee, M.H. Overview of therapeutic drug monitoring. Korean. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, K.; Afif, W.; Drobne, D.; et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: Unmet needs and future perspectives. Lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Monitoring Concentration of Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir by Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectormetry Method. Herald of Medicine. 2024, 43, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuchowski, N.A. and Bullen, J.A. Receiver operating characteristic (roc) curves: Review of methods with applications in diagnostic medicine. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 07tr01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, R.; Schiffmann, H.; Hube-Magg, C.; et al. Random forest-based modelling to detect biomarkers for prostate cancer progression. Clin. Epigenetics. 2019, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.C.; Lui, G.C.; Lai, M.S.; et al. Impact of the use of oral antiviral agents on the risk of hospitalization in community coronavirus disease 2019 patients (covid-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e26–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.K.; et al. Effectiveness and adverse events of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir versus molnupiravir for covid-19 in outpatient setting: Multicenter prospective observational study. J. Korean. Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; et al. Overview of therapeutic drug monitoring and clinical practice. Talanta. 2024, 266, 124996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, M.L.; Al-Dabbagh, M.; Groll, A.H.; et al. Utility of voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: A meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1786–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.D.; Ding, M.; Dong, X.; et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill covid-19 patients: A review. Allergy. 2021, 76, 428–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Dong, X.; Liu, G.H.; et al. Risk and protective factors for covid-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clin. Rev. Allergy. Immunol. 2023, 64, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, W.; Bao, H.; et al. Vv116 versus nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for oral treatment of covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Chen, C.; Tang, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and paxlovid) for covid-19:a meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, J. and Iglesias, C. [nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir (paxlovid) a potent sars-cov-2 3clpro protease inhibitor combination]. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2022, 35, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, H.; Dantonio, A.L.; Kadar, E.P.; et al. Disposition of nirmatrelvir, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of sars-cov-2 3c-like protease, across animals and humans. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. Bmj. 2020, 368, m1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Patel, U.; Mehta, D.; et al. Biomarkers and outcomes of covid-19 hospitalisations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. Evid. Based. Med. 2021, 26, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izcovich, A.; Ragusa, M.A.; Tortosa, F.; et al. Correction: Prognostic factors for severity and mortality in patients infected with covid-19: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2022, 17, 0269291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Detected ions | Precursor ion | Product ion | Cone/V | Collision/V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nirmatrelvir | 500.20 | 319.10 | 10 | 20 |

| Nirmatrelvir-D9 | 508.59 | 328.10 | 10 | 20 |

| Ritonavir | 721.30 | 426.10 | 20 | 20 |

| 13C,2H3- ritonavir | 725.30 | 426.10 | 20 | 20 |

| Variables | Level | COVID-19 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (114), n (%) / median (IQR) |

Group 0 (25), n (%) / median (IQR) |

|||

| Sex | Male | 60 (52.63%) | 17 (68%) | 0.164 |

| Age | year | 75 (64 - 83) | 81 (73 - 89) | 0.009 |

| History of smoking | Yes | 12(10.53%) | 2 (8%) | 0.989 |

| No | 102 (89.47%) | 23 (92%) | ||

| History of alcoholism | Yes | 6 (5.26%) | 1 (4%) | 1 |

| No | 108 (94.74) | 24 (96%) | ||

| Underlying disease of hypertension | Yes | 49 (42.98%) | 16 (64%) | 0.092 |

| No | 65 (57.02) | 9 (36%) | ||

| Department | ICU | 5 (4.39%) | 13 (52%) | / |

| Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine | 53(46.49%) | 7 (28%) | / | |

| Cardiovascular | 4 (3.51%) | 1 (4%) | / | |

| Oncology and hematology | 6 (5.26%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Neurology | 5 (4.39%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Infectious diseases | 11 (9.65%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Nephrology | 3 (2.63%) | 2 (8%) | / | |

| Gastroenterology | 1 (0.88) | 1 (4%) | / | |

| Urological | 1 (0.88) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Gynecology and obstetrics | 1 (0.88) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 1 (0.88) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Emergency medicine | 3 (2.63%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| Endocrinology | 2 (1.75%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| General medicine | 13 (11.4%) | 1 (4%) | / | |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 2 (1.75%) | 1 (4%) | / | |

| Gerontology | 2 (1.75%) | 0 (0%) | / | |

| ALT | U/L | 23.56 (18.89 - 32.25) | 25.46 (9.2 - 36.18) | 0.884 |

| AST | U/L | 23.96 (16.74 - 34.12) | 30.73 (16.9 - 44.45) | 0.274 |

| eGFR | mL/minute | 55.92 (43.62 - 69.5) | 41.75 (20.33 - 55.92) | <0.001 |

| CRP | mg/L | 31.8 (7.23 - 82.08) | 113.1 (33.7 - 140.8) | 0.001 |

| PCT | ng/mL | 0.06 (0.03 - 0.08) | 0.65 (0.06 - 2.29) | <0.001 |

| ALP | U/L | 65.9 (54 - 79) | 69 (54 - 85) | 0.641 |

| GGT | U/L | 31.30 (19.56 - 49.98) | 40.01 (26.93 - 55) | 0.329 |

| CK | U/L | 2.91 (2.1 - 3.5) | 2.94 (2.59- 3.93) | 0.348 |

| Cr | μmol/L | 81.1 (64.78 - 101.58) | 100.3 (82.2 - 163.3) | 0.003 |

| WBC | ×109/L | 5.56 (4.2 - 8.3) | 7.5 (5 - 11.9) | 0.037 |

| NE | ×109/L | 4.25 (3 - 6.9) | 6.2 (4.4 - 10.2) | 0.013 |

| Lymph | ×109/L | 0.69 (0.5 - 1.28) | 0.6 (0.3 - 0.8) | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).