1. Introduction

Adaptive responses to resistance training include increases in strength, skeletal muscle hypertrophy, and metabolic resilience [

1,

2]. One mechanism by which this can occur is through gene regulation via epigenetic modifications to DNA (i.e., CpG site methylation) and histones [

3,

4]. Histone acetylation is a well-documented post translational and epigenetic modification that occurs with different modalities of exercise training [

5]. More recent in vitro evidence additionally supports that histones can be lactylated in response to cellular stress [

6], and this acts competitively with acetylation given that both forms of post-translational modification occur on lysine residues. Since this discovery, lactylation has been found to be linked with numerous processes in tissues and cells including cardiac regulation, macrophage function, osteoblast cell differentiation, sepsis and cancer, and myogenesis [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

While examining the histone and/or global protein lactylation responses to exercise stimuli may provide fresh perspectives for understanding exercise gene/protein regulation, it has been less thoroughly clarified relative to acetylation. In this regard, histone acetylation has been shown to be altered with acute and chronic resistance training as well as aerobic training [

12,

13]. Moreover, skeletal muscle transcription factors and metabolic enzymes can exhibit altered acetylation states thereby affecting their functions [

14]. Conversely, only one rodent study to date has reported that treadmill exercise transiently increases skeletal muscle protein lactylation [

15]. Contrary to these data are human data from our laboratory indicating that acute resistance exercise, which leads to robust increases in peri-exercise blood lactate levels, did not affect 3- or 6-hour post-exercise skeletal muscle protein lactylation levels and/or the mRNA expression of associated genes [

16]. However, aside from these two studies providing equivocal data (potentially due to species and exercise modality differences), there is a lack of evidence as to whether different exercise modalities can affect skeletal muscle protein lactylation. Likewise, it is unclear as to whether dynamic alterations in post-exercise protein acetylation levels are inversely related to protein lactylation levels as reported by Zhang et al. in vitro [

6].

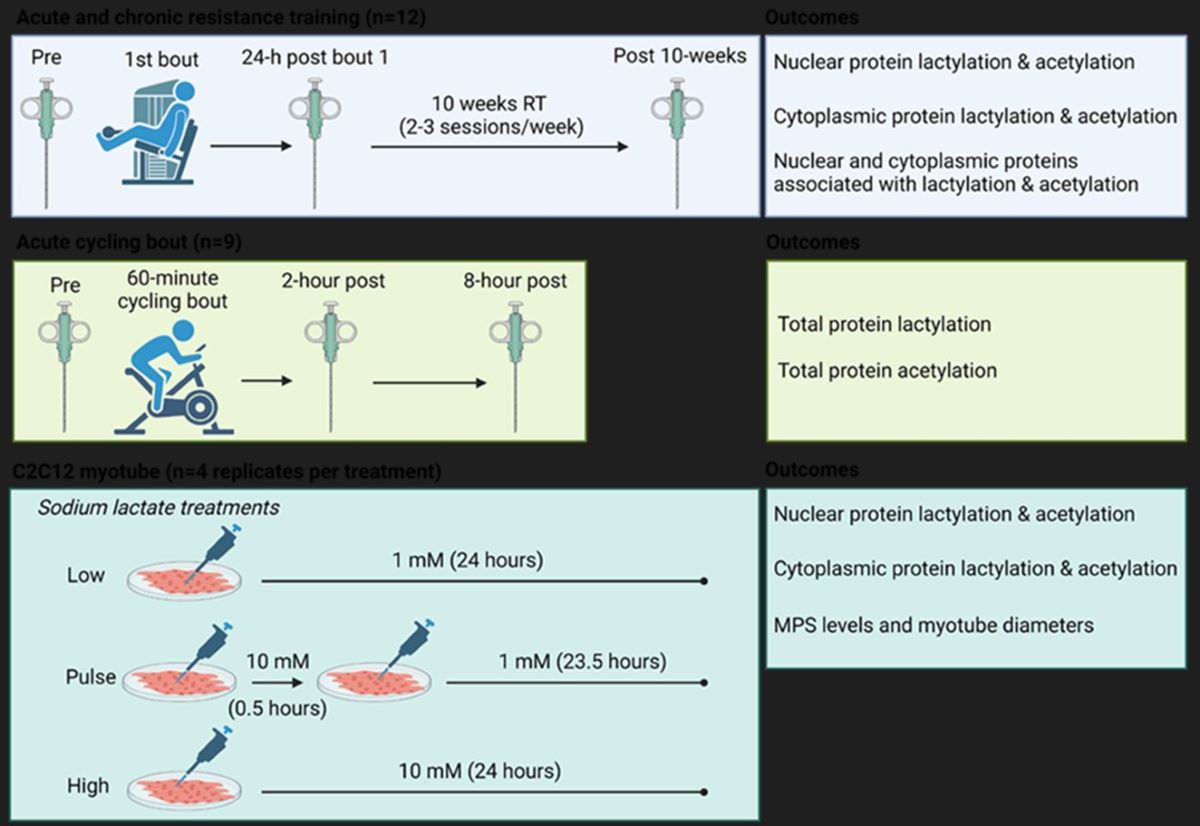

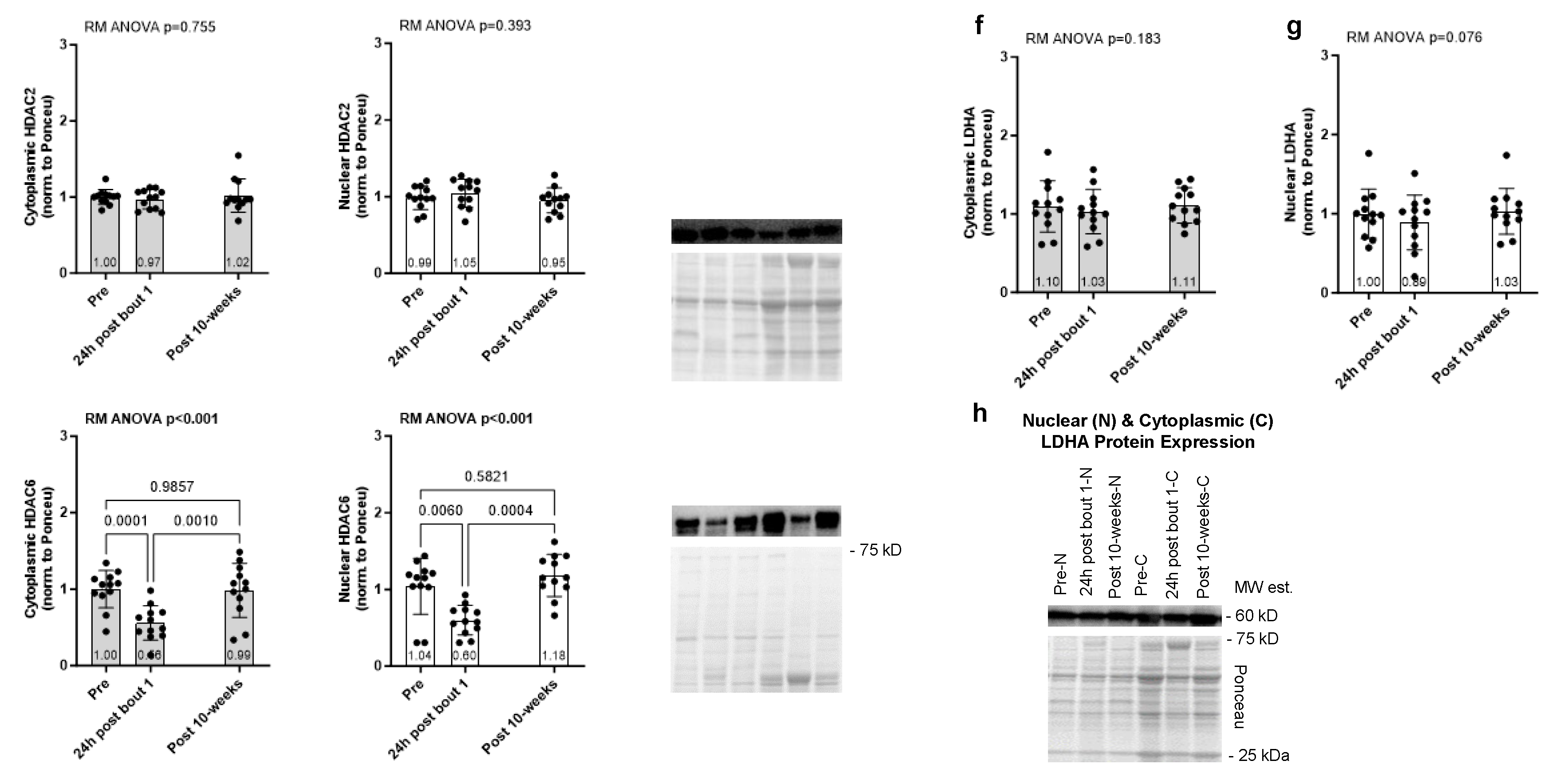

Therefore, one aim of this study was to determine in humans if one bout or chronic resistance training and/or one bout of endurance exercise affected various markers of skeletal muscle protein acetylation and lactylation. Moreover, we sought to determine how either pulse or 24-hour sodium lactate treatments affected similar outcomes in C2C12 myotubes (See

Figure 1 and Materials and Methods section). Due to our previous null findings, we hypothesized that markers associated with protein lactylation would either remain unaltered or decrease in response to different exercise paradigms. Moreover, in line with prior literature, we hypothesized markers associated with protein acetylation would be dynamically altered. Lastly, we hypothesized that lactate administration would not alter markers associated with protein lactylation in vitro.

2. Results

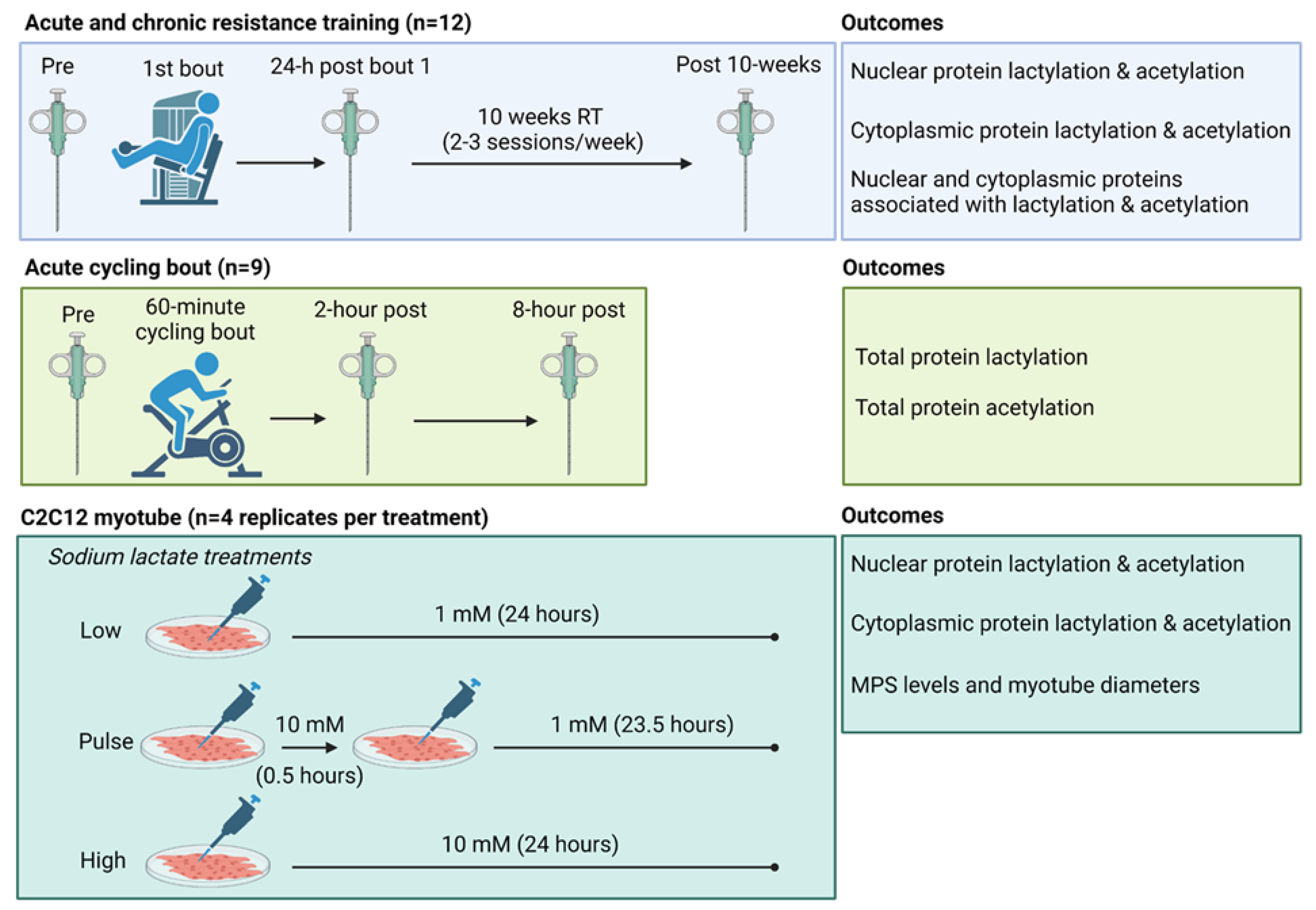

The results for the acute and chronic resistance training effects on muscle protein acetylation and lactylation markers are presented in

Figure 2. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein lactylation showed no significant model effects (

p = 0.879 and

p = 0.154,

Figure 2a/b). Although nuclear protein acetylation showed no significant model effect (

p = 0.109,

Figure 2d), cytoplasmic protein acetylation demonstrated a significant model effect (

p < 0.001,

Figure 2c) and was significantly lower at 24h post bout 1 and post-intervention compared to Pre (

p = 0.002 and

p = 0.006, respectively). Lastly, nuclear H3K9 acetylation showed no significant model effect (p = 0.296,

Figure 2e).

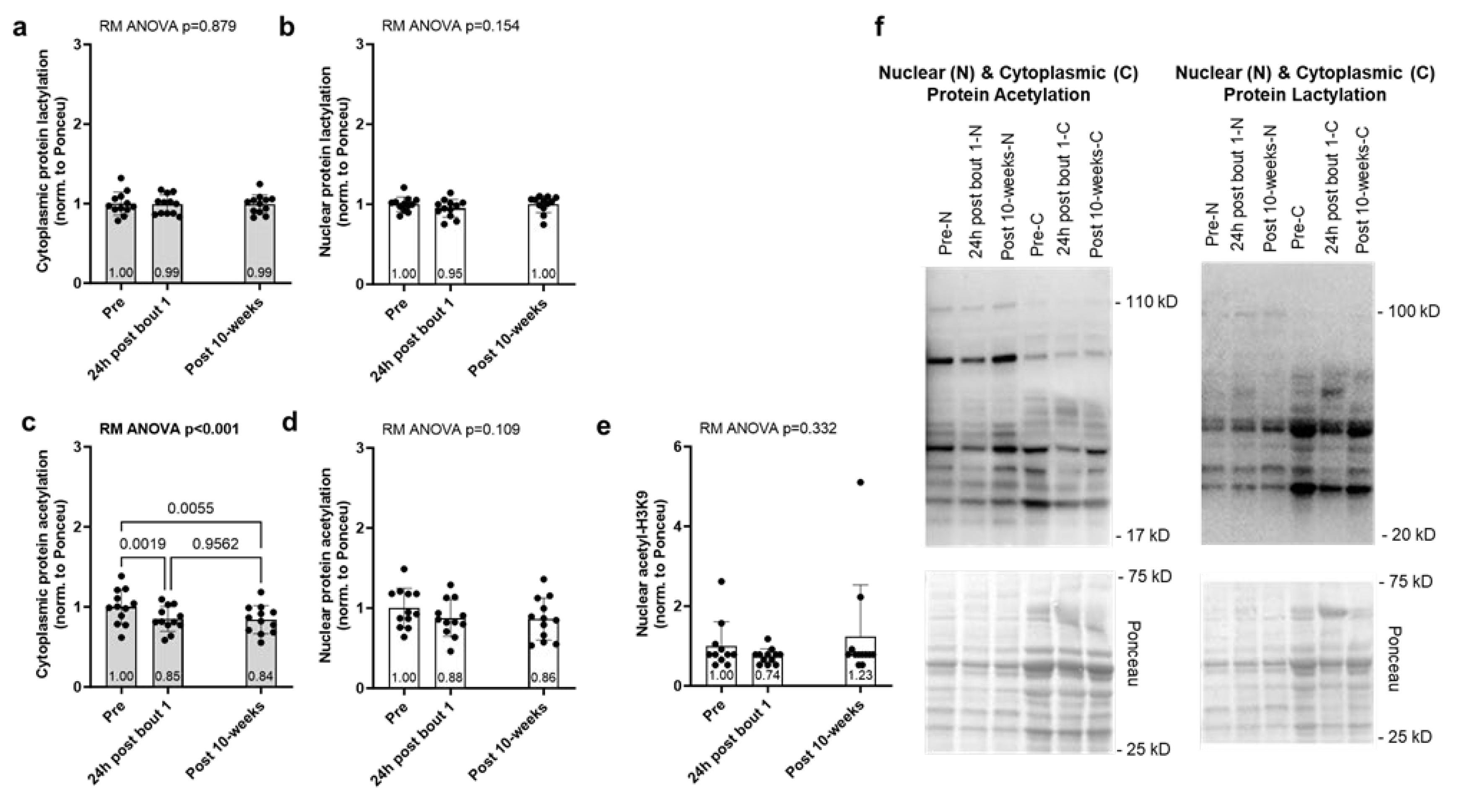

2.1. One Bout of Resistance Exercise, But Not Chronic Training, Significantly Decreases Select Enzymes Involved in Protein Acetylation and Lactylation

The results for the acute and chronic resistance training effects on select enzymes involved with protein acetylation (HDAC2/6) and lactylation (LDHA) are presented in

Figure 3. Cytoplasmic and nuclear HDAC2 protein expression showed no significant model effects (

p = 0.755 and

p = 0.393, respectively,

Figure 3a/b). However, cytoplasmic and nuclear HDAC6 protein expression exhibited significant model effects (

p < 0.001 for each,

Figure 3c/d), and this marker was reduced in both tissue fractions 24 hours following bout 1. Cytoplasmic and nuclear LDHA protein expression showed no significant model effects (

p = 0.183 and

p = 0.076,

Figure 3f/g).

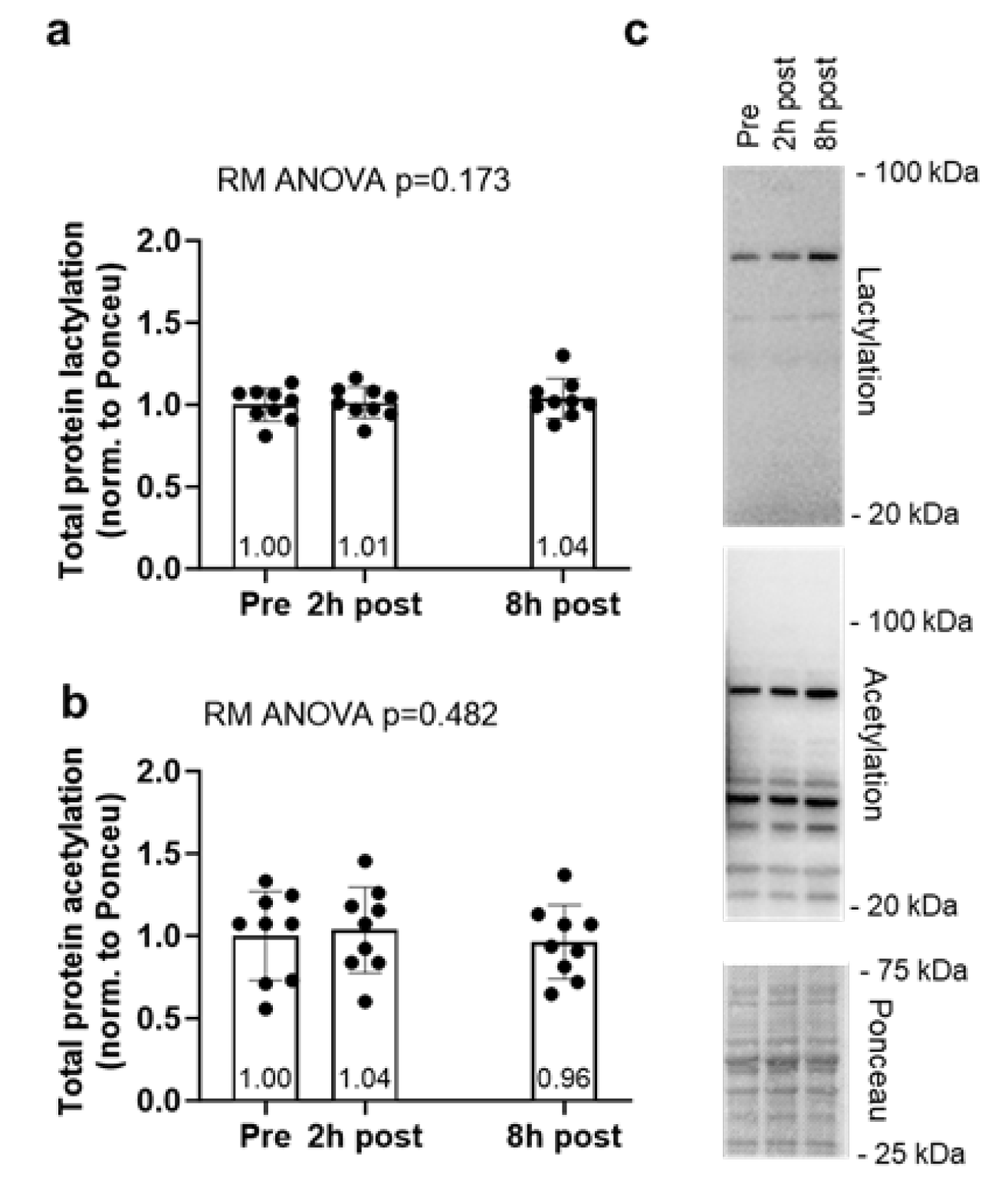

2.2. Global Protein Lactylation and Acetylation Markers Remain Unaltered Following 60 Minutes of Cycling

Global protein lactylation and acetylation data for the acute cycling bout can be found in

Figure 4. Global protein lactylation and global protein acetylation showed no significant model effects (

p = 0.173 and

p = 0.482, respectively,

Figure 4a/b).

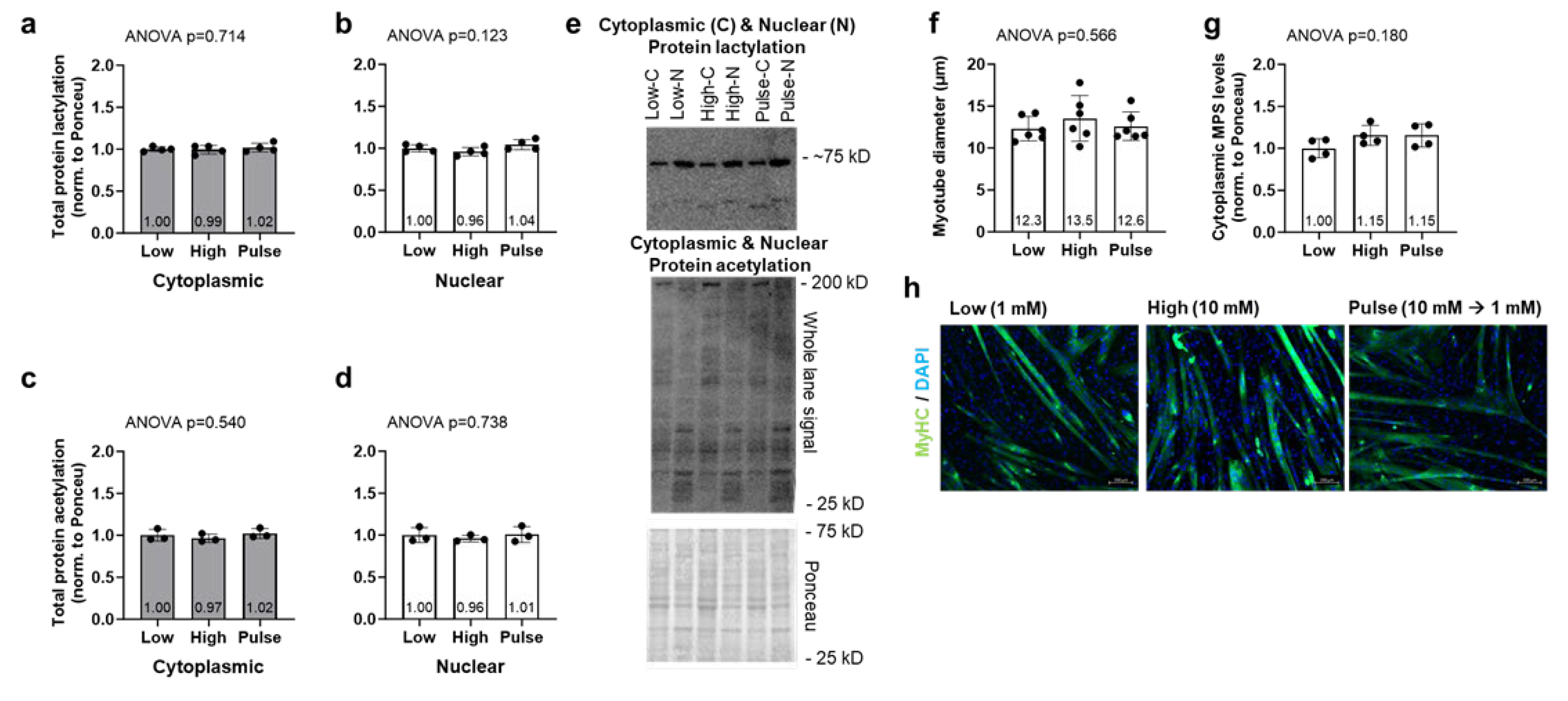

2.3. Lactate Administration Does Not Alter Myotube Diameter, Nuclear, or Cytoplasmic Puromycin-Labeled Proteins in C2C12 Cell Line

C2C12 cell culture experiment data can be found in

Figure 5. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein lactylation levels were not significantly different between treatments (ANOVA

p = 0.714 and

p = 0.123, respectively,

Figure 5a/b). Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein acetylation levels were also not significantly different between treatments (ANOVA

p = 0.540 and

p = 0.732, respectively,

Figure 5c/d). Myotube diameters were not significantly different between treatments (ANOVA

p = 0.566,

Figure 5f), and this is supported by cytoplasmic puromycin-labeled proteins (i.e., muscle protein synthesis levels) not being different between treatments (

p = 0.180,

Figure 5g).

3. Discussion

Given that the current literature is mixed regarding the ability of exercise to affect skeletal muscle protein lactylation, and that acetylation can compete with lactylation as a posttranslational modification, the objective of our study was to investigate how different modalities of exercise (acute resistance exercise, chronic resistance training, and acute endurance training) affected these outcomes. We hypothesized that markers associated with protein lactylation would remain unaltered in response to different exercise paradigms and that markers associated with protein acetylation would be dynamically altered. Additionally, we hypothesized that lactate administration would not alter markers associated with protein lactylation in vitro. The most intriguing finding from our study is the lack of protein lactylation across all experiments. As mentioned prior, some rodent data indicate that treadmill exercise acutely increases protein lactylation [

15]. Additionally, others have reported that lactate administration in C2C12 cells promotes histone lactylation [

11]; note that cells were treated with 15 mM sodium lactate for 3-5 days and their model was likely supraphysiological compared to ours which attempted to emulate lower dose treatments that are observed during exercise. Notwithstanding, in line with our prior human data [

16], the current data add further evidence to suggest that: i) resistance exercise does not acutely or chronically affect nuclear or cytoplasmic protein lactylation, ii) one bout of endurance exercise (via cycling) does not acutely affect skeletal muscle protein lactylation, and iii) treating myotubes with lower, higher, or a high pulsatile “exercise-like” dose of sodium lactate does not affect myotube lactylation.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic HDAC2 and LDHA protein levels were also not acutely or chronically altered with resistance training. Both enzymes have been implicated in catalyzing cellular protein de-lactylation and lactylation by acting as a Kla eraser and writer, respectively [

9,

17,

18]. While not measured in the current study, it is also notable that lactyl-CoA is used as a substrate by Kla writers to lactylate proteins. According to Varner et al. [

19], lactyl-CoA in cardiac tissue is exceedingly low relative to other acyl-CoAs, and this too casts doubt as to whether muscle proteins can be dynamically lactylated in response to exercise stressors. It is notable, however, there is recent evidence in humans to suggest that heightened skeletal muscle protein lactylation is associated with metabolic dysregulation. In this regard, Maschari et al. [

17] reported that obese, insulin-resistant women presented ~20% higher skeletal muscle protein lactylation levels compared to lean, healthy counterparts. In explaining their findings, the researchers identified other studies demonstrating increased post-translational modifications to muscle proteins that accompany metabolic dysfunction (e.g., acetylation and malonylation) and speculated that chronic/low-level lactate accumulation via metabolic dysregulation leads to increases skeletal muscle protein lactylation. With this collective evidence in mind, we posit that skeletal muscle protein lactylation is likely not a post-translational protein modification appreciably involved in the adaptive response to training.

The main motivation for measuring skeletal muscle and myotube protein acetylation levels was to determine if an inverse pattern was evident relative to protein lactylation levels across experiments. Additionally, we opted to assess HDAC2 and HDAC6 protein levels with the resistance training study specimens given that (unlike lactylation states) nuclear and cytoplasmic protein acetylation patterns were altered, the former two proteins act to deacetylate cellular proteins, and the latter marker is a histone acetyltransferase enzyme [

20]. The observed outcomes are interesting in the context of other human exercise studies. For instance, McGee et al. [

5] reported that one bout of cycling acutely reduces nuclear HDAC abundance following exercise. Hostrup et al. [

21] more recently used an acetylomic approach to report that five weeks (15 sessions) of high-intensity cycle interval training increases the acetylation of ~260 sites of mitochondrial TCA cycle proteins.

Lim et al. [

12] reported that histone 3 acetylation increased three hours following one resistance exercise bout as well as following 10 weeks of resistance training. Interestingly, we observed that nuclear and cytoplasmic HDAC6 and protein acetylation levels decreased following one bout and chronic resistance training. The reduction in nuclear HDAC6 agrees in principle with the aforementioned report by McGee et al. However, reduced muscle protein acetylation with resistance training contrasts with the notion that exercise training generally increases protein acetylation. While this finding is difficult to reconcile, Hain et al. [

22] reported that C2C12 myotube atrophy (induced via serum-conditioned media experiments from a cancerous cell line) coincided with significantly heightened myotube protein acetylation. In explaining their findings, the researchers posited that protein hyperacetylation can reduce protein function and stability and this is a signature of muscle atrophy. Notably, over 80% of contractile proteins in skeletal muscle are subject to acetylation [

23]. Acetylation has also been found to be a master regulator in mitochondrial metabolic pathways with 63% of mitochondrial proteins having been found containing lysine acetylation sites [

24]. Collectively, these results indicate reductions in protein acetylation could be an explicit response to resistance exercise to potentially aid in the adaptive response. However, this is highly speculative and future investigations are needed to determine protein- and site-specific acetylation events along with the functional ramifications of reduced protein acetylation.

Lastly, other secondary cell culture findings are noteworthy due to select in vitro and rodent evidence indicating that lactate may potentiate anabolic signaling in skeletal muscle [

25]. However, as we have pointed out previously [

16], single or multi-day lactate administration paradigms have not been shown to bolster anabolic signaling in rodent or human skeletal muscle [

26,

27], and our data continue to support this notion.

3.1. Experimental Considerations

We aimed to leverage tissue collected from prior studies performed by our laboratories to further explore the potential for exercise stimuli to affect skeletal muscle protein lactylation. As such, the current data are limited in participant number and biopsy sampling time points. Therefore, we cannot completely rule out that resistance or endurance exercise does not affect skeletal muscle protein lactylation and future human studies with more sampling time points are needed. Additionally, although global nuclear/cytoplasmic protein lactylation levels were shown not to be affected across experiments, it remains possible that specific lysine residues across various proteins may exhibit altered lactylation states. Hence, lactylomic-based approaches can serve to further interrogate this potential phenomenon. Finally, given that skeletal muscle protein acetylation was measured to merely examine if an inverse/competitive pattern was present relative to protein lactylation levels, we view our resistance training protein acetylation data as being underdeveloped. Whereas other studies indicate that endurance exercise generally increases skeletal muscle protein acetylation, the observation that resistance training reduced muscle protein acetylation was unexpected and warrants further investigation.

3.2. Conclusions

This is the second human study to date demonstrating that different exercise stimuli do not affect global skeletal muscle protein lactylation, and these data continue to challenge lactate as being a signaling metabolite that affects muscle anabolism. Moreover, the resistance exercise-induced decrement in global skeletal muscle protein acetylation levels is a relatively novel finding, and the significance of this finding requires additional research.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Approval for Human Work

Human vastus lateralis muscle specimens were obtained from apparently healthy, untrained college-aged participants described in two previously published studies by Chaves et al. [

28] (acute and chronic resistance training) and Roberson et al. [

29] (acute cycling). For the resistance training study, experimental procedures were approved by the local ethics committee, the study was conducted in accordance with the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was pre-registered as a clinical trial (Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials – RBR-57v9mrb). The study by Roberson et al. was approved by the Auburn University Institutional Review Board (protocol #18-226) but was not pre-registered as a clinical trial. Inclusion criteria for both studies can be found in the original works.

4.2. Study Designs

A schematic illustrating study designs is depicted in

Figure 1 above, and descriptions for each experiment follow.

4.2.1. Acute and Chronic Resistance Training Study

Muscle specimens were from 12 participants [8M/4F, 25 ± 4 years old, 24.0 ± 3.8 kg/m

2), and training as well as specimen collection was performed at the Federal University of Sao Carlos. The resistance training protocol consisted of four sets of 9–12 maximum repetitions of unilateral leg extension exercises, with a 90-second rest period between sets. The load was adjusted for each set to ensure that concentric muscle failure occurred within the target repetition range. Participants completed 24 training sessions over a period of 10 weeks, with sessions conducted 2 to 3 times per week. Four mid-thigh vastus lateralis (VL) biopsies were obtained during the intervention including the basal state pre-intervention sample (Pre, first biopsy), 24 h after the first training bout (second biopsy), 96 hours after the second to last training bout (basal state post-intervention biopsy, third biopsy), and 24 h after the last training bout (trained state acute response, fourth biopsy). However, due to sample limitations we only analyzed the first three biopsies with the participants reported herein. Tissue was lysed using a commercially available nuclear isolation kit (Abcam; Cambridge, MA, United States; Cat. No. ab113474) as previously described [

16], and nuclear as well as cytoplasmic lysates were prepared for Western blotting as described in the next section.

4.2.2. Acute Endurance Training Study

Nine participants (3M/6F, 23 ± 2 years old, 23.1 ± 2.6 kg/m2) reported to the laboratory during the morning hours under fasted conditions and donated a baseline VL biopsy. Participants then mounted a cycle ergometer (Velotron, RacerMate, Seattle, WA, United States) and performed a 5-minute warm-up at a self-selected pace. Wattage was adjusted thereafter to achieve 70% heart rate reserve and participants cycled for 60 minutes. Post-exercise biopsies were then obtained 2- and 8-hours following the cycling bout. Whole tissue lysates were obtained using a general cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA, United States; Cat. No. 9803) as previously described by Roberson et al. (Roberson et al., 2019) and processed for Western blotting described below.

4.2.3. Cell Culture Experiments

C2C12 myoblasts (passage 2-4) were cultured in 100 mm plates with DMEM (Corning; Corning, NY, United States) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (VWR; Radnor, PA, United States; Cat No. 89510-182), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (VWR; Cat No. 16777-164), and 0.1% gentamicin (VWR; Cat No. 97061-372) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO

2. Upon reaching 90% confluency, myoblasts were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 2% horse serum (Corning; Cat No. 35-030-CV), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.1% gentamicin for 7 days until mature myotube formation. To investigate the influence of lactate on C2C12 myotube protein lactylation and anabolism, myotubes (3-4 replicates per condition) were treated with varying levels of sodium lactate (LOW: 1 mM for 24-hours, PULSE: 10 mM for 30 minutes followed by 1 mM for 23.5-hours, HIGH: 10 mM for 24 hours) (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. L14500). Twenty-three- and one-half hours into treatments cells were pulse-labeled with 1 µM of puromycin hydrochloride (VWR; Cat. No. 97064-280) for the assessment of cytoplasmic muscle protein synthesis levels using the SUnSET method as performed with in vitro studies in our laboratory [

30,

31]. Cells were then lysed using a commercially available nuclear isolation kit (Abcam; Cat. No. ab113474), and nuclear as well as cytoplasmic lysates were prepared for Western blotting as described in the next section.

A second set of myotube plates with each sodium lactate treatment were also immuno-stained to assess morphology. Following treatments described above myotubes were fixed with 10% formalin (VWR) for 15 minutes at room temperature then washed 3 x 3 minutes with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS/Triton). Cells were then blocked with PBS/Triton containing 1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with a primary antibody solution containing anti-myosin heavy chain (1:100) (DSHB; Iowa City, IA, United States; Cat. No. A4.1025) in PBS/Triton/BSA for 3 hours at room temperature. Following 3 x 3-minute washes with PBS/Triton, cells were incubated with a secondary antibody solution containing goat anti-mouse IgG2a AF488 (ThermoFisher; Cat. No. A-21131) in PBS/0.2% Triton-X for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were then washed 3 x 3 minutes with PBS/Triton and incubated with DAPI (ThermoFisher; Cat. No. D3571) for 10 minutes. After the last wash, multiple images were obtained by a fluorescent microscope using a 10x objective (Zeiss Axio imager.M2; Ziess). Myotube diameters were then quantified on digital images using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD, United States) like methods we have previously described [

31].

4.3. Western Blotting

Nuclear and cytoplasmic isolates (resistance training and C2C12 experiments) as well as general lysates (acute cycling) were assayed for total protein content using a commercially available BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher; Waltham, MA, United States) and a spectrophotometer (Agilent Biotek Synergy H1 hybrid reader; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Thereafter, protein concentrations were standardized to 0.5-1.0 µg/µL using Laemmli buffer depending upon the protein fraction, and 15 µL of each sample was loaded into 4%-15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, United States). Electrophoresis occurred at 180 V for 50 minutes using 1x SDS-PAGE run buffer (VWR). Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) at 200 mA for 2 hours. Following transfers, membranes were Ponceau stained and imaged using a gel documentation system (ChemiDoc Touch; Bio-Rad) to capture whole-lane images for protein normalization purposes. Membranes were then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% nonfat milk powder mixed in Tris-buffered saline solution containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST; VWR).

For the interrogation of protein lactylation, membranes were incubated for 48 hours at 4°C with a rabbit anti-lactyl lysine antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, United States; Cat. No. PA5116901) at a 1:1000 dilution in TBST solution containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following primary antibody incubations, membranes were washed three times in TBST (15 minutes total) and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:2000; Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 7074) in TBST solution containing 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 hour. After secondary antibody incubations, membranes were washed three times in TBST (15 minutes total) and developed in a gel documentation system (ChemiDoc Touch; Bio-Rad) using a chemiluminescent reagent (Luminata Forte HRP substrate; Millipore Sigma).

Other membranes were incubated overnight at 4ºC with either an anti-acetyl lysine antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 9441), anti-HDAC2 antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 57156), anti-HDAC6 antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 7558), anti-LDHA antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 2012), anti-p300 antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 86377), or anti-acetylated-histone 3 (H3K9) antibody (Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 8173) at 1:1000 dilutions in TBST solution containing 5% BSA. Following primary antibody incubations and three TBST washes, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated an anti-rabbit antibody (1:2000) in TBST solution containing 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 hour before development as described above. Notably, the p300 immoblotting experiments did not yield a signal potentially due to its low level of expression in adult skeletal muscle.

Lastly, our cell culture lysates underwent the same anti-acetyl lysine antibody and anti-lactyl lysine antibody protocols described above, and membranes were also interrogated using an anti-puromycin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States, Cat. No. MABE342) at 1:10,000 dilution in TBST solution with 5% BSA. Following primary antibody incubations and three TBST washes, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated an anti-mouse antibody (1:2000; Cell Signaling; Cat. No. 7072) at a 1:2000 dilution in TBST solution containing 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 hour before development as described above.

Whole lane or band densities from all Western blot experiments were analyzed using ImageLab v6.0.1 (Bio-Rad). Protein target values were corrected for Ponceau densities and normalized to Pre values (exercise studies) or the LOW treatment (C2C12 experiments) to obtain data as fold-change values.

4.4. Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v9.2.0 (San Diego, CA, United States), and the figures were created either using GraphPad Prism or BioRender (

https://biorender.com). For the exercise studies, one-way repeated measures ANOVAs were performed, and Tukey’s post hoc tests were conducted if model significance was obtained. For the cell culture study, ordinary one-way ANOVAs were performed. All data in-text and in figures are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) values and statistical significance was established as

p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

M.L.M. and M.D.R. conceived the study outcomes, and M.C.S., J.G.B. and C.A.L. designed the resistance training intervention. M.L.M., D.A.A., and J.S.G. performed all assays and in vitro experiments. B.A.R., C.B.M., and A.D.F. provided critical feedback on study outcomes. M.L.M. and M.D.R. primarily drafted the manuscript and all authors provided edits.

Funding

C.A.L. was supported by The São Paulo Research Foundation (#2023/04739-2) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (#311387/2021-7). D.A.A. was supported by an Auburn University Presidential Opportunity Fellowship. The School of Kinesiology and College of Nursing (Auburn University) provided additional financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For the resistance training study, experimental procedures were approved by the local ethics committee, the study was conducted in accordance with the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was pre-registered as a clinical trial (Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials – RBR-57v9mrb). The study by Roberson et al. was approved by the Auburn University Institutional Review Board (protocol #18-226).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (mdr0024@auburn.edu) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to report in relation to this work. In the interest of full disclosure, M.D.R. and A.D.F. report current research contracts and gifts from several industry sponsors. M.D.R. and A.D.F act as a consultants for industry entities and healthcare entities, respectively, in accordance with rules established by Auburn University’s Conflict of Interest (COI) Policies.

References

- Roberts, M.D.; McCarthy, J.J.; Hornberger, T.A.; Phillips, S.M.; Mackey, A.L.; Nader, G.A.; Boppart, M.D.; Kavazis, A.N.; Reidy, P.T.; Ogasawara, R.; et al. Mechanisms of mechanical overload-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy: current understanding and future directions. Physiol Rev 2023, 103, 2679–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; Sharples, A.P. Molecular responses to acute exercise and their relevance for adaptations in skeletal muscle to exercise training. Physiol Rev 2023, 103, 2057–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, I.; Kawano, F. Chronic exercise training activates histone turnover in mouse skeletal muscle fibers. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, S.L.; Hargreaves, M. Histone modifications and exercise adaptations. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011, 110, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, S.L.; Fairlie, E.; Garnham, A.P.; Hargreaves, M. Exercise-induced histone modifications in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2009, 587, 5951–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Ubiquitous protein lactylation in health and diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2024, 29, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Finkel, T. Lactylation regulates cardiac function. Cell Res 2023, 33, 653–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, F.; Qian, Y.; Xu, F.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. LDHA promotes osteoblast differentiation through histone lactylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 615, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tu, F.; Gill, P.S.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wu, G.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q.; Tao, J.; Liu, H.; Shen, M. Lactate promotes myogenesis via activating H3K9 lactylation-dependent up-regulation of Neu2 expression. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 2851–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Shimizu, J.; Kawano, F.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.K. Adaptive responses of histone modifications to resistance exercise in human skeletal muscle. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meireles, L.C.; Bertoldi, K.; Cechinel, L.R.; Schallenberger, B.L.; da Silva, V.K.; Schroder, N.; Siqueira, I.R. Treadmill exercise induces selective changes in hippocampal histone acetylation during the aging process in rats. Neurosci Lett 2016, 634, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Fukushima, A.; Matsumoto, J.; Takada, S.; Kakutani, N.; Nambu, H.; Yamanashi, K.; Furihata, T.; Yokota, T.; Okita, K.; et al. Protein acetylation in skeletal muscle mitochondria is involved in impaired fatty acid oxidation and exercise intolerance in heart failure. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 844–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Su, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Xing, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. High-Intensity Interval Training Induces Protein Lactylation in Different Tissues of Mice with Specificity and Time Dependence. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, M.L.; Ruple, B.A.; Sexton, C.L.; Godwin, J.S.; McIntosh, M.C.; Smith, M.A.; Plotkin, D.L.; Michel, J.M.; Anglin, D.A.; Kontos, N.J.; et al. Resistance training in humans and mechanical overload in rodents do not elevate muscle protein lactylation. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1281702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschari, D.; Saxena, G.; Law, T.D.; Walsh, E.; Campbell, M.C.; Consitt, L.A. Lactate-induced lactylation in skeletal muscle is associated with insulin resistance in humans. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 951390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Yruela, C.; Zhang, D.; Wei, W.; Baek, M.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Dankova, D.; Nielsen, A.L.; Bolding, J.E.; Yang, L.; et al. Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine delactylases. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabi6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varner, E.L.; Trefely, S.; Bartee, D.; von Krusenstiern, E.; Izzo, L.; Bekeova, C.; O’Connor, R.S.; Seifert, E.L.; Wellen, K.E.; Meier, J.L.; et al. Quantification of lactoyl-CoA (lactyl-CoA) by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry in mammalian cells and tissues. Open Biol 2020, 10, 200187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, C.; Kang, X. The epigenetic regulatory effect of histone acetylation and deacetylation on skeletal muscle metabolism-a review. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1267456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Lemminger, A.K.; Stocks, B.; Gonzalez-Franquesa, A.; Larsen, J.K.; Quesada, J.P.; Thomassen, M.; Weinert, B.T.; Bangsbo, J.; Deshmukh, A.S. High-intensity interval training remodels the proteome and acetylome of human skeletal muscle. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, B.A.; Kimball, S.R.; Waning, D.L. Preventing loss of sirt1 lowers mitochondrial oxidative stress and preserves C2C12 myotube diameter in an in vitro model of cancer cachexia. Physiol Rep 2024, 12, e16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, A.; Lage, K.; Weinert, B.T.; Bekker-Jensen, D.B.; Secher, A.; Skovgaard, T.; Kelstrup, C.D.; Dmytriyev, A.; Choudhary, C.; Lundby, C.; et al. Proteomic analysis of lysine acetylation sites in rat tissues reveals organ specificity and subcellular patterns. Cell Rep 2012, 2, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, J.; Smallegan, M.J.; Denu, J.M. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Protein Acetylation in Mitochondria. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.; Vann, C.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Haun, C. Beyond Mechanical Tension: A Review of Resistance Exercise-Induced Lactate Responses & Muscle Hypertrophy. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Kitaoka, Y.; Uemichi, K.; Tokinoya, K.; Takeda, K.; Takemasa, T. Effects of lactate administration on hypertrophy and mTOR signaling activation in mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep 2022, 10, e15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liegnell, R.; Apro, W.; Danielsson, S.; Ekblom, B.; van Hall, G.; Holmberg, H.C.; Moberg, M. Elevated plasma lactate levels via exogenous lactate infusion do not alter resistance exercise-induced signaling or protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2020, 319, E792–E804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, T.S.; Scarpelli, M.C.; Bergamasco, J.G.A.; Silva, D.G.D.; Medalha Junior, R.A.; Dias, N.F.; Bittencourt, D.; Carello Filho, P.C.; Angleri, V.; Nobrega, S.R.; et al. Effects of Resistance Training Overload Progression Protocols on Strength and Muscle Mass. Int J Sports Med 2024, 45, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, P.A.; Romero, M.A.; Osburn, S.C.; Mumford, P.W.; Vann, C.G.; Fox, C.D.; McCullough, D.J.; Brown, M.D.; Roberts, M.D. Skeletal muscle LINE-1 ORF1 mRNA is higher in older humans but decreases with endurance exercise and is negatively associated with higher physical activity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2019, 127, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.B.; Fox, C.D.; Ferguson, B.S.; Amin, R.H.; Dalbo, V.J.; Baier, S.; Rathmacher, J.A.; Wilson, J.M.; Roberts, M.D. L-leucine, beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyric acid (HMB) and creatine monohydrate prevent myostatin-induced Akirin-1/Mighty mRNA down-regulation and myotube atrophy. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.B.; Mumford, P.W.; McCarthy, J.J.; Miller, M.E.; Young, K.C.; Martin, J.S.; Beck, D.T.; Lockwood, C.M.; Roberts, M.D. Whey protein-derived exosomes increase protein synthesis and hypertrophy in C(2-)C(12) myotubes. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).