1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the second most common cancer in men from industrial countries with over 1.46 million new cases and 396.000 deaths reported annually [

1]. Projections based on demographic changes and increasing life expectancy indicate that annual new PC cases will increase to 2.9 million in 2040 [

2].

Treatment options for localized PC includes active surveillance, watchful waiting, external beam radiation, brachytherapy or radical prostatectomy (RP) [

3]. The prerequisite for a successful treatment is the complete eradication of the tumor. If residual tumor cells persist in the surgical margins the tumor may relapse locally and begin to metastasize. Biochemical relapse affects approximately 20-40% of the patients within ten years after RP [

4]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), either as monotherapy or in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, has become the standard treatment for patients with relapsed castration-sensitive PC [

3]. Unfortunately, the efficacy of ADT is limited. Over time, the tumor becomes hormone refractory and progresses to metastatic castration-resistant PC (mCRPC). The standard treatment for mCRPC involves ADT in combination with chemotherapy and prednisolone. However, this approach is primarily palliative and only marginally prolongs the patient’s overall survival, which is on average 16 to 18 months [

5]. Depending on the treatment and the progression of the disease, patients suffer from a range of symptoms and adverse effects such as incontinence, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, reduction in muscle mass and bone density, edema, and psychosomatic symptoms, which negatively affect their quality of life [

3]. Given to the limitations of current therapeutic strategies, there is an urgent need for the development of novel and innovative therapeutic approaches for PC.

Despite the promising results of conventional and PSMA-targeted therapies, tumor heterogeneity remains a major cause of treatment failure in PC [

6]. Patients with primary PC often harbor multiple distinct tumor foci within the prostate gland, exhibiting high levels of intra-tumoral heterogeneity [

7]. The origin of tumor heterogeneity can be explained by the prostate cancer stem cell (PCSC) hypothesis, which postulates that PCSCs form a small subset of cells within the tumor capable of self-renew and differentiate into various cell types. Moreover, these cells are able to initiate carcinogenesis and drive disease progression [

8]. From a therapeutic point of view, this means that all tumor cells, i.e., PCSCs and differentiated PC cells, have to be eliminated to achieve complete cure. Since PCSCs are characterized by unique tumor antigens, either exclusive to them or shared with differentiated PC cells, they can be targeted using RNA knockdown, inhibitors or antibodies directed against these antigens [

8].

In the present study, we introduce photoimmunotherapy (PIT) as an innovative supportive treatment during RP to target PC cells and PCSCs. PIT employs tumor-specific antibodies conjugated with photoactivatable dyes (photosensitizers) that can be activated by visible light to selectively induce cancer cell death [

9]. In our approach, we used antibodies against the cluster of differentiation 44 antigen (CD44) and the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) to target both PC cells and PCSCs. CD44 is a hyaluronic acid transmembrane receptor, which serves as cell adhesion and signaling molecule. It is associated with self-renewal, proliferation, differentiation, invasion and metastasis of PC. EpCAM is a transmembrane glycoprotein with various cellular functions, contributing to cancer stem cell maintenance, proliferation, invasion, metastasis and therapeutic resistance [

8]. We conjugated the anti-CD44 and anti-EpCAM antibodies to our novel silicon phthalocyanine photosensitizer dye, WB692-CB2, and evaluated these antibody dye conjugates for PIT of PC and PCSC-like cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Dye

The suspension cell line EXPI293F (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) was cultured in serum-free FreeStyle F17 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 8 mM L-glutamine (PAN-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) and 0.1% pluronic F68 (PAN-Biotech). The PC cell line PC3-PSMA was a kind gift from P. Giangrande (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA). The cell line PC3-MM2 was kindly provided by the MD Anderson Cancer Center (Huston, TY, USA). This cell line is marked by some stem cell characteristics and can therefore serve as a PCSC-like line [

10]. Both cell lines were cultivated in RMPI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Pen/Strep, Merck). The control cell line CHO (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was cultivated in Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mixture medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep. All cell lines were propagated under sterile conditions at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. Cell line identities were verified using short tandem repeat (STR) analysis (CLS GmbH, Eppelheim, Germany). For the preparation of cell lysates, cells were lyzed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% SDS, 1% Igepal supplemented with cOmplete

TM Protease Inhibitor Cocktail for 30 min on ice, followed by centrifugation (18000 x g, 30 min, 4°C). Protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by using the Quick Start

TM Bradford Protein Assay according to manufactures instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The phthalocyanine photosensitizer dye WB692-CB2 [

11] was kindly provided by Jonas Storz and Reinhard Brückner, Institute for Organic Chemistry, University of Freiburg, Germany.

2.2. Cloning, Expression and Purification of the Anti-CD44 and Anti-EpCAM Antibodies

The genes encoding the human IgG1 heavy chains of the anti-CD44 antibody [

12] and the anti-EpCAM antibody [

13], each containing the cysteine mutations T120C and D265C (EU numbering) were synthesized (GeneArt, Invitrogen, Regensburg, Germany) and cloned into the expression vector pCSEH1c [

14]. Synthesized variable domains of the light chains (V

L) of both antibodies were cloned into the expression vector pCSL3k, containing a constant domain (CL) of a human IgG1 kappa light chain. After transformation of the vectors into XL1- Blue MRF´ supercompetent E.coli cells (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), the plasmids were purified using the NucleoBond

® Xtra Maxi Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The sequences of the antibody chains were then verified for accuracy through sequencing (Microsynth Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany). Recombinant expression of the antibodies in EXPI293F cells was performed as described [

11]. After purification by protein G affinity chromatography (Cytiva, Marlborough, USA) and dialysis against PBS, concentrations of the antibodies, called CD44

T120C/D265C and EpCAM

T120C/D265C, were determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. Conjugation of the Photosensitizer Dye WB692-CB2

For conjugation of the dye WB692-CB2, the cysteine-modified antibodies CD44

T120C/D265C and EpCAM

T120C/D265C were diluted in PBS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 (PBSE), as described [

11]. In brief, following reduction with Tris-(2-Carboxyethyl)phosphine, Hydrochloride and dialysis against PBSE, the antibodies were re-oxidized with dehydroascorbic acid. For dye conjugation, the antibodies were incubated with WB692-CB2 and the reaction was quenched using N-acetyl-L-cysteine. After dialysis against PBS (pH 7.4), unbound dye was removed by protein G affinity chromatography and the antibody dye conjugates were stored a 4°C protected from light. The dye to antibody ratios of the conjugates were determeined as published [

11].

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western Blots

Cell lysates, antibodies and conjugates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using the NuPAGE® Bis-Tris Electrophoresis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, 3 µg of antibody or conjugate were combined with NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer and NuPAGE® Reducing Agent, followed by incubation for 10 minutes at 70°C. Then, the samples were loaded onto a pre-cast NuPAGE® Novex® Bis-Tris Gel. Electrophoresis was performed at 200 V for 35 minutes using the XCell SureLockTM Mini-Cell system, with NuPAGE® MES Buffer supplemented with NuPAGE® Antioxidant as running buffer. For SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions, the same protocol using Laemmli sample buffer without NuPAGE® Reducing Agent was used. Protein detection was achieved by Coomassie staining or fluorescence-based imaging (λmax = 680 nm, IVIS Spectrum, In Vivo Imaging System, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

For Western blot analysis, the proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane at 30 V for 1 hour in NuPAGE® Transfer Buffer supplemented with 10% methanol and 1% NuPAGE® antioxidant. The membrane was then blocked with 5% non-fat milk in 0.1% Tween-20/PBS (M-PBST) for 1 hour. The membrane was then incubated with mouse anti-human CD44 (#ab82529, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) or mouse anti-human EpCAM (#sc-25308, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) as primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in M-PBST. After washing with 0.1% Tween-20/PBS, the membrane was incubated with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody rabbit anti-mouse Ig/HRP (#P0161, DAKO, Hamburg, Germany) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by another washing step. ß-actin was detected as loading control using the antibody mouse α-human β-actin-HRP (Proteintech Group Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA). Detection of the target proteins was conducted using an enhanced chemiluminescence solution and the INTAS Chemo Star Imager (INTAS Science Imaging Instruments, Göttingen, Germany).

2.5. Flow Cytometry

Specific binding of the antibodies or antibody dye conjugates to the PC cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Cells were seeded at a density of 2x105 cells per well in flow cytometry buffer consisting of PBS , 3% FBS, 0.1% sodium azide. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of antibody or conjugate for one hour on ice. Following this, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated using a goat-anti-human Ig(H+L)-RPE detection antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) for 30 minutes at 4°C, protected from light. After washing, cells were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer supplemented with 1 µg/ml propidium iodide. Mean fluorescence intensities of the stained cells were measured with a FACS Calibur Flow Cytometer and the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Binding affinities of the antibodies or conjugates were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software and dissociation constants (Kd) were defined as the antibody or conjugate concentrations leading to half-maximal specific binding.

2.6. Photoimmunotherapy

For PIT, 2.5x105 cells were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes and cultivated for 24 h in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). On the next day, cell culture medium was removed. Fresh medium containing the appropriate treatment (medium, free dye, 10 µg/ml antibody, 10 µg/ml conjugate or 10 µg/ml of two conjugates each in the combination experiment) was administered to the cells, followed by incubation for 24 h. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated in fresh medium and irradiated with various mean irradiation light doses (λmax = 690 nm) of a light-emitting diode (LED, L690-66-60, Marubeni America Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). 24 h after irradiation, the cells were trypsinized and stained with the vital dye Erythrosine b, followed by cell viability analysis with a Neubauer Counting Chamber. Cell numbers of living cells were normalized relative to the untreated control establishing a baseline of 100%.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of the Anti-CD44 and Anti-EpCAM Antibody Dye Conjugates

The recombinant cysteine-engineered antibodies, CD44

T120C/D265C and EpCAM

T120C/D265C, were successfully cloned and expressed in EXPI293F cells. Antibody yields were obtained, with 44.6 mg/L supernatant for CD44

T120C/D265C and of 39.4 mg/L supernatant for EpCAM

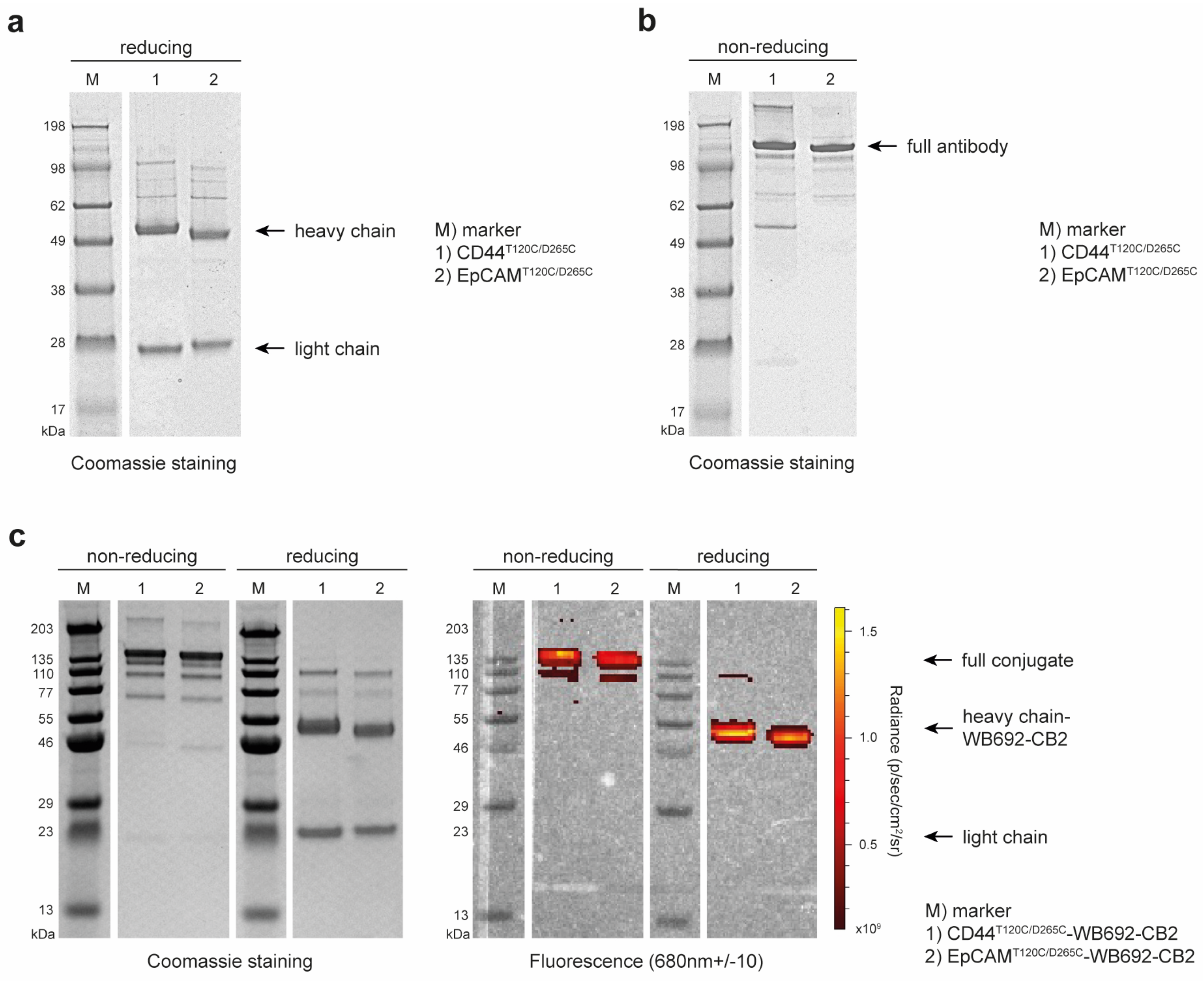

T120C/D265C, in high purity after Protein G affinity chromatography (

Figure 1a). SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions confirmed the successful self-assembly of the antibodies, comprising two heavy and two light chains, forming a whole hIgG1 molecule with a predicted size of ~150 kDa (

Figure 1b).

Following dye conjugation, the antibody dye conjugates CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Examination of the gels under red light (λ

max = 680 nm) confirmed the successful conjugation of the dye to the heavy chains of the antibodies (

Figure 1c). Mean dye to antibody ratios were determined to be 2.82 ± 0.02 for the CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 conjugate and of 3.14 ± 0.17 for the EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 conjugate.

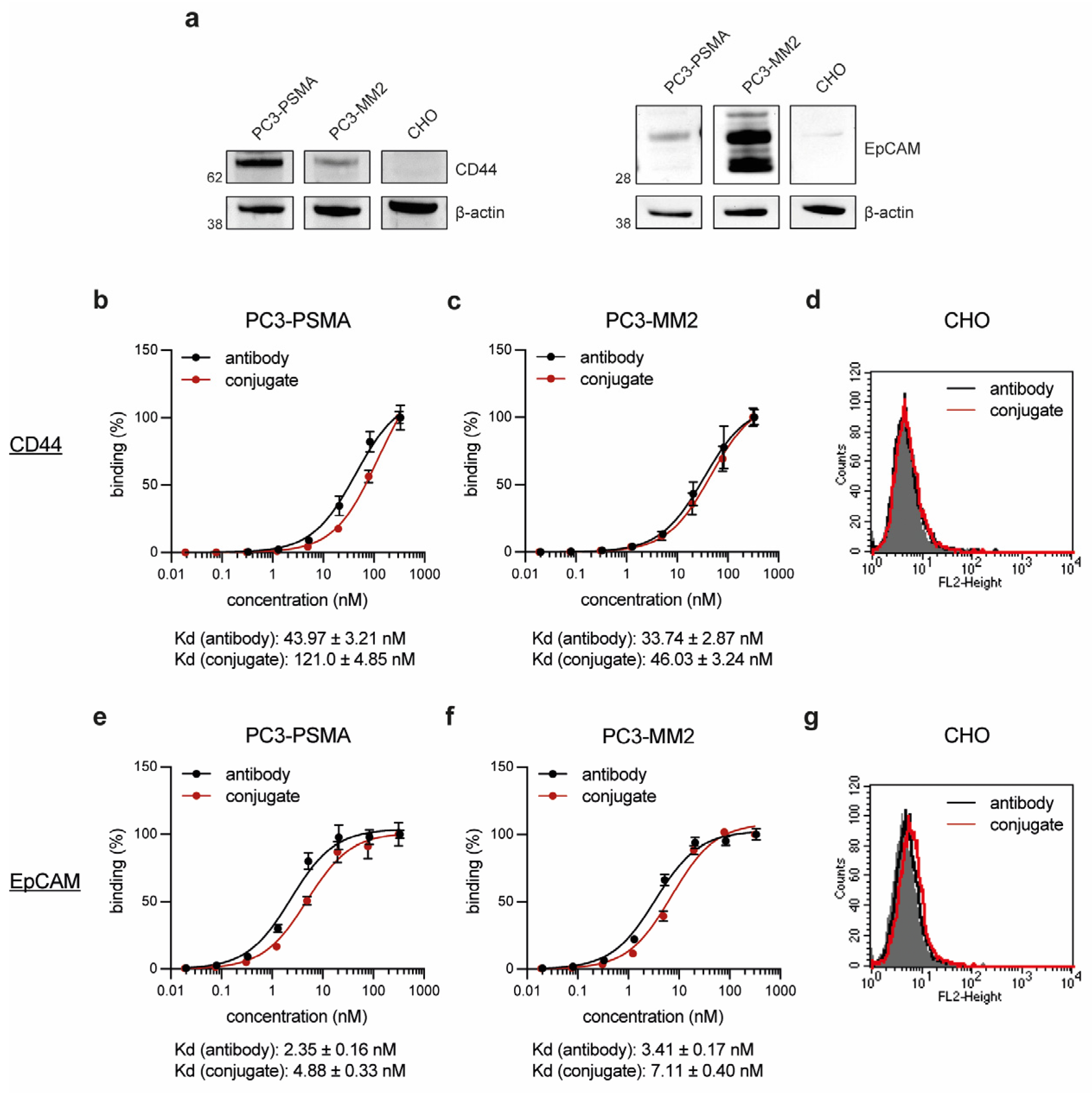

In the next step, the PC cell line PC3-PSMA and the PCSC-like cell line PC3-MM2 were confirmed to express the target proteins CD44 and EpCAM by Western Blot analyses, while the control cell line CHO was found to be negative for both antigens (

Figure 2a). The binding affinity of the conjugates CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 were then evaluated on both cell lines. The conjugates exhibited slightly lower binding affinities (higher Kd values) within the low nanomolar range compared to their uncoupled counterparts, CD44

T120C/D265C and EpCAM

T120C/D265C (

Figure 2b,c,e,f). No binding was detected with both molecules on CD44 and EpCAM-negative CHO cells (

Figure 2d,g). This proved that the dye conjugation did not or only minimally affect the avidity of the antibodies and did not lead to unspecific binding of the conjugates.

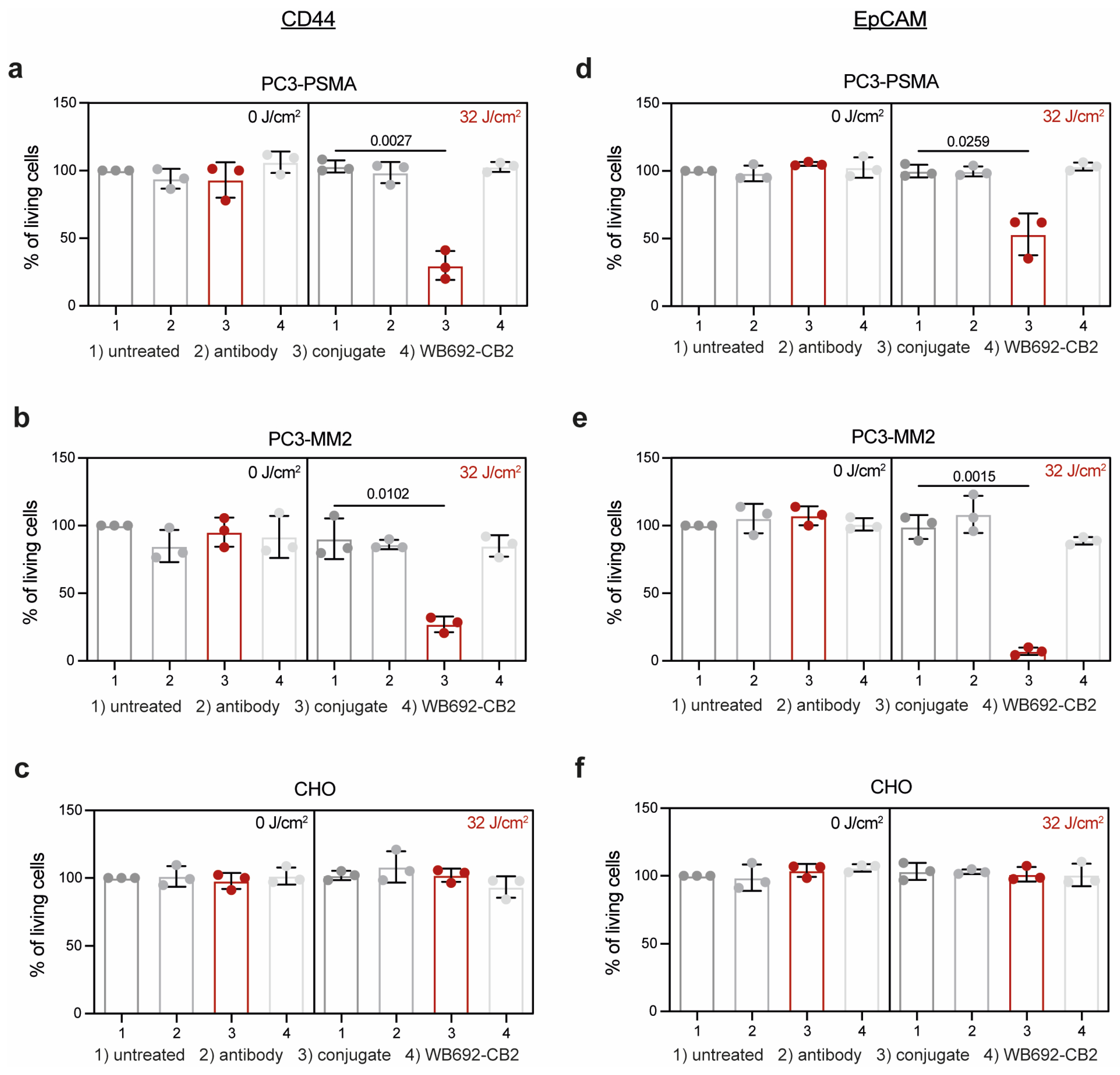

The efficacy of PIT using the conjugates CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 and EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 was evaluated on the target cells 24 h after exposure with a light dose of 32 J/cm². Control cells were either left untreated or were incubated with equimolar concentrations of antibody or free dye. As shown in

Figure 3a,b, the viability of PC3-PSMA and PC3-MM2 cells treated with the conjugate CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 were significantly reduced to 29.9 ± 10.7% (p=0.0027) and 27.1 ± 5.8% (p=0.0102), respectively. In contrast, no cytotoxic effects were observed in cells treated with the antibody or free dye. Cells from all treatment groups remained unaffected without irradiation. Moreover, CD44-negative CHO cells were completely unaffected by PIT (

Figure 3c). Similar results were obtained with the conjugate EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 in PC3-PSMA and PC3-MM2 cells after PIT. Cell viability was significantly reduced to 53.1 ± 15.4% (p=0.0259;

Figure 3d) and 7.1 ± 2.8% (p=0.0015;

Figure 3e), respectively, while EpCAM-negative CHO cells remained completely unaffected by treatment (

Figure 3f). These findings indicate that PIT using our dye WB692-CB2 is a highly selective and effective therapeutic strategy for targeting PC cells and PCSCs.

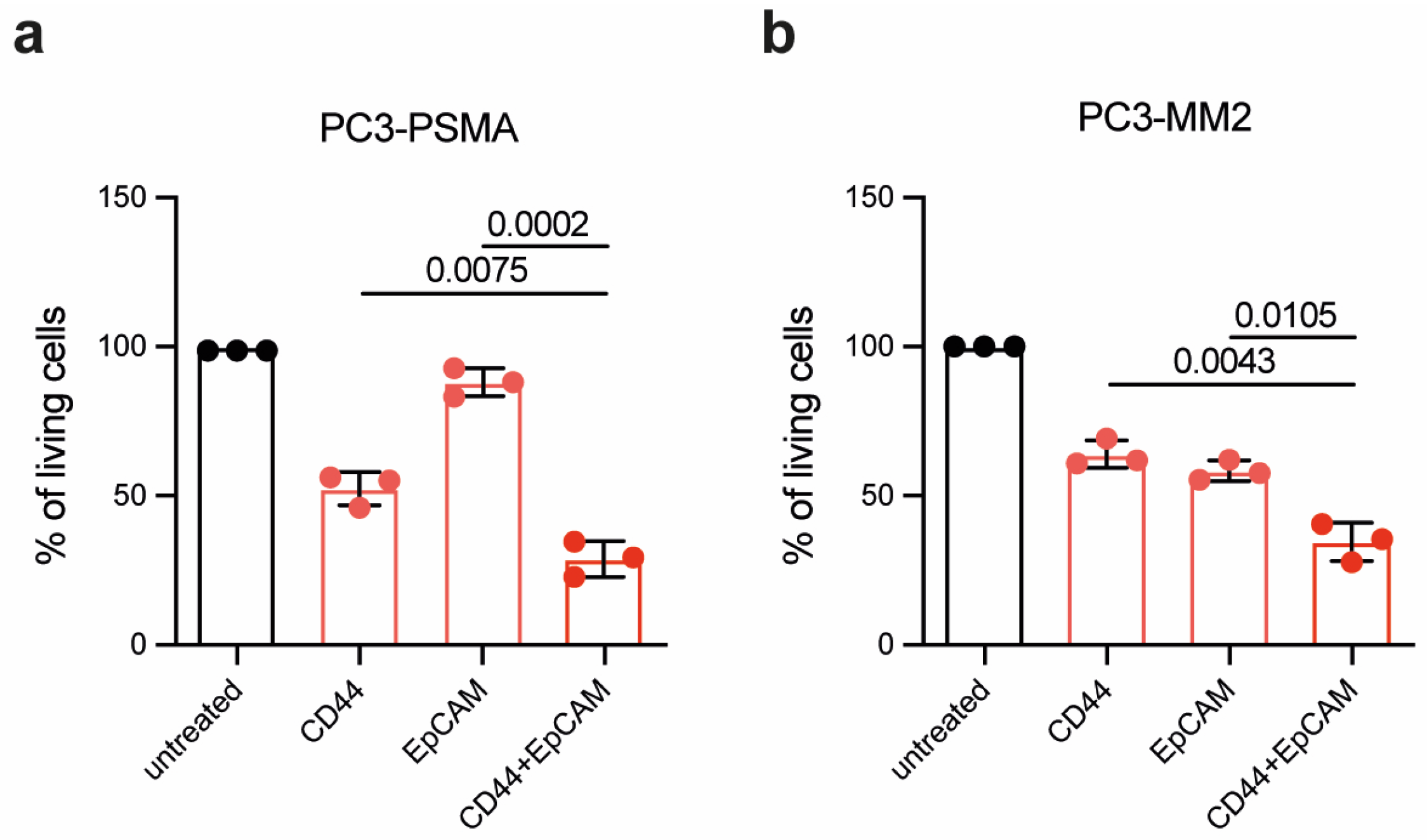

To develop a therapeutic approach against residual PC cells following RP, the efficacy of PIT using CD44

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 in combination with EpCAM

T120C/D265C-WB692-CB2 was evaluated using a light irradiation dose of 16 J/cm

2. In the PC cell line PC3-PSMA, combinatorial PIT resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability compared to single treatments. Specifically, cell viability was significalntly reduced from 52.5 ± 5.6 % targeting CD44 and 88.1 ± 4.7 % targeting EpCAM to only 28.9 ± 6.0 % after PIT targeting CD44 in combination with EpCAM (p = 0.0075 and p = 0.0002, respectively;

Figure 4a). Similar results were obtained in the PCSC-like PC3-MM2 cells, where the cell viability was significantly reduced from 64.0 ± 4.5 % targeting CD44 and 58.4 ± 3.4 % tageting EpCAM to 34.6 ± 6.5 % after combinatorial PIT targeting CD44 and EpCAM (p = 0.0043 and p = 0.0105, respectively;

Figure 4b).

Our results demonstrated the enhanced efficacy of combinatorial PIT compared to single PIT, indicating that simultaneously targeting multiple tumor antigens may provide a more effective therapeutic strategy for PC.

4. Discussion

Tumor heterogeneity in PC, driven by PCSCs, remains a major challenge, contributing to therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development of novel and innovative therapeutic approaches for PC. PIT has emerged as a new cornerstone in local cancer treatment with minimal off-target effects. This technique leverages photoactivatable photosensitizers conjugated to antibodies or antibody fragments to induce specific, immunogenic cancer cell death and systemic antitumor immunity [

15]. We have developed the novel silicon phthalocyanine dye, WB692-CB2, which can be directly conjugated to free cysteines in antibodies via a maleimide linker [

11]. Since all naturally occurring cysteines in an antibody molecule are used for the formation of intra- and interchain disulfide bridges, our dye can be specifically conjugated to engineered cysteines, which are not expected to affect the folding and thus the avidity and specificity of the antibody. The cysteine-specific conjugation offers an advantage over the conventional coupling to lysines. A human IgG1 antibody contains approx. 80 to 90 lysines, leading to undefined and heterogeneous conjugate preparations, when coupling occurs at these sites. By specifically targeting engineered cysteines, we can achieve more homogenous antibody dye conjugate preparations. Our conjugation method allowed the attachment of approximately 2.8 to 3.1 dye molecules to the four engineered cysteines of one each anti-CD44 or anti-EpCAM antibody molecule.

Our PIT experiments demonstrated that the anti-CD44 and anti-EpCAM conjugates, with their specific dye loads, effectively induced cell death of both PC and PCSC-like cells within 24 h after irradiation using a light dose of 32 J/cm

2. Moreover, combinatorial PIT using both conjugates significantly enhanced cytotoxicity compared to single treatments. In addition to the combination of different conjugates against different target antigens, it is also possible to achieve better therapeutic effects by increasing the light dose [

11]. Additionally, engineering antibodies to incorporate additional cysteines could increase dye loading in future applications, which could also lead to an increased cytotoxicity.

The un-conjugated dye was found to be non-cytotoxic, which can be attributed to its inherent hydrophilicity for solubility, which prevents diffusion through cellular membranes [

11]. This characteristic is particularly advantageous, as it ensures that the dye exhibits cytotoxic effects only, when it is transported by the antibody into the target cells and is activated by light. This might reduce potential side effects in clinical practice and enhances the specificity of the therapeutic approach. Recently, we found that a main mechanism of PIT-induced cell death with our dye is pyroptosis [

11]. Pyroptosis is a unique form of pro-inflammatory programmed cell death, predominantly mediated by caspase-1 dependent cleavage of gasdermin D. This cleavage leads to the formation of non-selective pores in the plasma membrane, allowing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and influx of water. This is followed by cellular swelling, membrane rupture and release of damage-associated molecular patterns and tumor-associated neoantigens, which initiate an adaptive anti-cancer immune response [

16]. Thus, locally applied PIT could potentially lead to systemic immunological antitumor effects. This means, that in clinical use, intraoperative PIT could also be effective against tumor cells that have already spread or metastasized. To further explore this, future studies can employ syngeneic tumor models in immunocompetent mice to investigate the immunogenic effects of PIT [

17].

5. Conclusions

In the context of PC, WB692-CB2 based PIT can be employed as a focal therapy, preserving the prostate gland, and reducing side effects. It can be utilized during minimally invasive robotic-assisted RP to detect and treat residual tumor cells or lymph node metastases in areas where surgery cannot be continued. The use of multiple conjugates against antigens expressed on differentiated PC cells and PCSC cells, e.g., CD44 and EpCAM, could be an effective method to eradicate the heterogeneous population of residual cancer cells completely. This approach could lead to the prevention of local recurrence after RP and thus to the complete cure of PC patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.W. and P.W.; methodology, I.W., S.S.S., P.W..; formal analysis, I.W.; investigation, I.W., S.S:S. and P.W.; resources, C.G. and P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, I.W. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, I.W., S.S.S., C.G. and P.W.; visualization, I.W. and P.W.; supervision, P.W.; project administration, P.W.; funding acquisition, P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation, grant number WO 2178/3-1 to P.W. and supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Giangrande (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA) for the PC3-PSMA cells and the MD Anderson Cancer Center (Huston, TX, USA) for the PC3-MM2 cells. We acknowledge E. V. Wenzel and S. Dübel (University of Braunschweig) for providing the cloning vectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N’Dow, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: planning for the surge in cases. Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebello, R.J.; Oing, C.; Knudsen, K.E.; Loeb, S.; Johnson, D.C.; Reiter, R.E.; Gillessen, S.; Van der Kwast, T.; Bristow, R.G. Prostate cancer. Nature reviews. Disease primers 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.F.; Moul, J.W. Rising prostate-specific antigen after primary prostate cancer therapy. Nature clinical practice. Urology 2005, 2, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karantanos, T.; Corn, P.G.; Thompson, T.C. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5501–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, R.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L. Tumor microenvironment heterogeneity an important mediator of prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. NPJ precision oncology 2022, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haffner, M.C.; Zwart, W.; Roudier, M.P.; True, L.D.; Nelson, W.G.; Epstein, J.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Nelson, P.S.; Yegnasubramanian, S. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2021, 18, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, I.; Gratzke, C.; Wolf, P. Prostate Cancer Stem Cells: Clinical Aspects and Targeted Therapies. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 935715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin, T.M.; Zhang, C.; Sheng, W.; Al-Rawe, M.; Zeppernick, F.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Hussain, A.F. Near Infrared Photoimmunotherapy: A Review of Recent Progress and Their Target Molecules for Cancer Therapy. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botchkina, G.I.; Zuniga, E.S.; Rowehl, R.H.; Park, R.; Bhalla, R.; Bialkowska, A.B.; Johnson, F.; Golub, L.M.; Zhang, Y.; Ojima, I.; et al. Prostate cancer stem cell-targeted efficacy of a new-generation taxoid, SBT-1214 and novel polyenolic zinc-binding curcuminoid, CMC2.24. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, I.; Storz, J.; Schulze-Seemann, S.; Eßer, P.; Martin, S.; Lauw, S.; Fischer, P.; Peschers, M.; Melchinger, W.; Zeiser, R.; et al. A new silicon phthalocyanine dye induces pyroptosis in prostate cancer cells during photoimmunotherapy. Bioactive Materials 2024, 41, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birzele, F.; Cannarile, M.; Feuerhake, F.; Fischer, T.; Heil, F.; Honold, K.; Nopora, A.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Voss, E.; S., W. Markers for responsiveness to anti-cd44 antibodies. Patent: WO2014198843A1 2014.

- Cizeau, J.; Macdonald, G.; Premsukh, A. Optimized nucleic acid sequences for the expression of vb4-845. Patent: WO2009039630A1, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Steinwand, M.; Droste, P.; Frenzel, A.; Hust, M.; Dübel, S.; Schirrmann, T. The influence of antibody fragment format on phage display based affinity maturation of IgG. mAbs 2014, 6, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.A.; Okamura, S.M.; De Magalhaes Filho, C.D.; Bergeron, D.M.; Rodriguez, A.; West, M.; Yadav, D.; Heim, R.; Fong, J.J.; Garcia-Guzman, M. Cancer-targeted photoimmunotherapy induces antitumor immunity and can be augmented by anti-PD-1 therapy for durable anticancer responses in an immunologically active murine tumor model. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023, 72, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Hsu, J.M.; Hung, M.C. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis in inflammation and antitumor immunity. Molecular cell 2021, 81, 4579–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Okada, R.; Furusawa, A.; Inagaki, F.; Wakiyama, H.; Furumoto, H.; Okuyama, S.; Fukushima, H.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Simultaneously Combined Cancer Cell- and CTLA4-Targeted NIR-PIT Causes a Synergistic Treatment Effect in Syngeneic Mouse Models. Mol Cancer Ther 2021, 20, 2262–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).