Submitted:

02 October 2024

Posted:

03 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Gastroscopic Examination

2.3. Oral Cavity Examination

2.4. Owner Questionnaire

2.5. Treatment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sykes, B.W.; Hewetson, M.; Hepburn, R.J.; Luthersson, N.; Tamzali, Y. European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement--Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. J Vet Intern Med 2015, 29, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.; Bernard, W.; Byars, D.; Cohen, N.; Divers, T.; MacAllister, C.; McGladdery, A.; Merritt, A.; Murray, M.; Orsini, J.; et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS): The Equine Gastric Ulcer Council. Equine Veterinary Education 1999, 11, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.K.; Trachsel, D.; Merle, R.; Gehlen, H. Vergleich des Therapieerfolgs zweier Omeprazolpräparate und Übereinstimmung zwischen zwei Untersuchern beim Equinen Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS). Pferdeheilkunde 2022, 38, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewetson, M.; Tallon, R. Equine Squamous Gastric Disease: Prevalence, Impact and Management. Vet Med (Auckl) 2021, 12, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, R.; Hewetson, M. Inter-observer variability of two grading systems for equine glandular gastric disease. Equine Vet J 2021, 53, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vondran, S.; Venner, M.; Vervuert, I. Effects of two alfalfa preparations with different particle sizes on the gastric mucosa in weanlings: alfalfa chaff versus alfalfa pellets. BMC Vet Res 2016, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokes, J.; Lovett, A.; Sykes, B. Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome: An Update on Current Knowledge. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, H.E.; Andrews, F.M. Equine glandular gastric disease: prevalence, impact and management strategies. Vet Med (Auckl) 2019, 10, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, B.W.; Underwood, C.; McGowan, C.M.; Mills, P.C. The effect of feeding on the pharmacokinetic variables of two commercially available formulations of omeprazole. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2015, 38, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, G.; Bowen, I.M.; Habershon-Butcher, J.L.; Nicholls, V.; Hallowell, G.D. Misoprostol is superior to combined omeprazole-sucralfate for the treatment of equine gastric glandular disease. Equine Vet J 2019, 51, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, B.W.; Kathawala, K.; Song, Y.; Garg, S.; Page, S.W.; Underwood, C.; Mills, P.C. Preliminary investigations into a novel, long-acting, injectable, intramuscular formulation of omeprazole in the horse. Equine Vet J 2017, 49, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.; Hallowell, G.; Rendle, D. A study investigating the treatment of equine squamous gastric disease with long-acting injectable or oral omeprazole. Vet Med Sci 2020, 6, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.; Hallowell, G.; Rendle, D. Evaluation of the treatment of equine glandular gastric disease with either long-acting-injectable or oral omeprazole. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendle, D.; Bowen, M.; Brazil, T.; Conwell, R.; Hallowell, G.; Hepburn, R.; Hewetson, M.; Sykes, B. Recommendations for the management of equine glandular gastric disease. UK-Vet Equine 2018, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, F.B., R. Mäßige Therapieerfolge sowohl bei einer hochdosierten Therapie mit Omeprazol-Granulat (Equizol®) als auch bei der Kombinationstherapie aus Omeprazol-Paste (Gastrogard®) und Sucralfat (Sucrabest®) bei Pferden mit Equine Glandular Gastric Disease (EGGD). Pferdeheilkunde 2023, 39, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, H.; Prieß, A.; Doherr, M. Deutschlandweite multizentrische Untersuchung zur Ätiologie von Magenschleimhautläsionen beim Pferd. Pferdeheilkunde 2021, 37, 395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, F.M.; Buchanan, B.R.; Elliot, S.B.; Clariday, N.A.; Edwards, L.H. Gastric ulcers in horses. Journal of Animal Science 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Schusser, G. Measurement of 24-h gastric pH using an indwelling pH electrode in horses unfed, fed and treated with ranitidine. Equine veterinary journal 1993, 25, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, L.; Sanchez, L.C.; Baptiste, K.E.; Olsen, S.N. Effect of a feed/fast protocol on pH in the proximal equine stomach. Equine Vet J 2009, 41, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub-Dargatz, J.; Salman, M.; Voss, J. Medical problems of adult horses, as ranked by equine practitioners. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1991, 198, 1745–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmalt, J.L.; Townsend, H.G.G.; Allen, A.L. Effect of dental floating on the rostrocaudal mobility of the mandible of horses. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2003, 223, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, E.J.; Duncanson, G.R. An equine postmortem dental study: 50 cases. Equine Veterinary Education 2000, 12, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, K.; Maretta, S.; Inoue, O.; Baker, G. Survey of equine dental disease and associated oral pathology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th annual convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, 1994; pp. 119–120.

- Dixon, P.M.; Dacre, I. A review of equine dental disorders. The Veterinary Journal 2005, 169, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, S.L.; Foster, D.L.; Divers, T.; Hintz, H.F. Effect of dental correction on feed digestibility in horses. Equine Veterinary Journal 2001, 33, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, N. Clinical significance of equine cheek teeth infundibular caries. Veterinary Record 2017, 181, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.K.; Cribb, A.E.; Windeyer, M.C.; Read, E.K.; French, D.; Banse, H.E. Risk factors for equine glandular and squamous gastric disease in show jumping Warmbloods. Equine Vet J 2018, 50, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthersson, N.; Nielsen, K.H.; Harris, P.; Parkin, T.D. Risk factors associated with equine gastric ulceration syndrome (EGUS) in 201 horses in Denmark. Equine Vet J 2009, 41, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundra, T.; Kelty, E.; Rendle, D. Five- versus seven-day dosing intervals of extended-release injectable omeprazole in the treatment of equine squamous and glandular gastric disease. Equine Vet J 2024, 56, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, A.M.; Sanchez, L.C.; Burrow, J.A.; Church, M.; Ludzia, S. Effect of GastroGard and three compounded oral omeprazole preparations on 24 h intragastric pH in gastrically cannulated mature horses. Equine Vet J 2003, 35, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, B.W.; Underwood, C.; Mills, P.C. The effects of dose and diet on the pharmacodynamics of esomeprazole in the horse. Equine Vet J 2017, 49, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recknagel, S.; Abraham, G.; Regenthal, R.; Friebel, L.; Schusser, G.F. Intragastrale pH-Metrie während der Omeprazolbehandlung bei nüchternen und gefütterten Pferden. Pferdeheilkunde 2020, 36, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Sykes, B.W.; Brown, H.; Bishop, A.; Penaluna, L.A. A comparison of the prevalence of gastric ulceration in feral and domesticated horses in the UK. Equine Veterinary Education 2015, 27, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.J.; Grodinsky, C.; Anderson, C.W.; Radue, P.F.; Schmidt, G.R. Gastric ulcers in horses: a comparison of endoscopic findings in horses with and without clinical signs. Equine Vet J Suppl 1989, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.J.; Eichorn, E.S.; Jeffrey, S.C. Histological characteristics of induced acute peptic injury in equine gastric squamous epithelium. Equine Vet J 2001, 33, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundra, T.; Gough, S.; Rossi, G.; Kelty, E.; Rendle, D. Comparison of oral esomeprazole and oral omeprazole in the treatment of equine squamous gastric disease. Equine Vet J 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.C.; Blackford, J.T.; Andrews, F.; Frazier, D.L.; Mattsson, H.; Olovsson, S.-G.; Peterson, A. Duration of antisecretory effects of oral omeprazole in horses with chronic gastric cannulae. Equine Veterinary Journal 1992, 24, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, L.C.; van der Poel, S.H.; Warmelink, T.S.; van Doorn, D.A.; van den Boom, R. Changes in Management Lead to Improvement and Healing of Equine Squamous Gastric Disease. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Buchanan, B.R.; Elliott, S.B.; Al Jassim, R.A.; McGowan, C.M.; Saxton, A.M. In vitro effects of hydrochloric and lactic acids on bioelectric properties of equine gastric squamous mucosa. Equine Vet J 2008, 40, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, L.; Sanchez, L.C.; Olsen, S.N.; Baptiste, K.E.; Merritt, A.M. Effect of paddock vs. stall housing on 24 hour gastric pH within the proximal and ventral equine stomach. Equine Vet J 2008, 40, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Squamous Mucosa |

|---|---|

| 0 | Intact epithelium and no appearance of hyperkeratosis |

| 1 | Intact mucosa, but areas of hyperkeratosis |

| 2 | Small, single or multifocal lesions |

| 3 | Large single or extensive superficial lesions |

| 4 | Extensive lesions with areas of apparent deep ulceration |

| Grade | Glandular Mucosa |

|---|---|

| 0 | Intact mucosa |

| 1 | Intact mucosa, patchy or streaky yellowish or reddish lesions |

| 2 | Small, isolated or multifocal lesions |

| 3 | Large single or extensive superficial lesions, possibly bleeding |

| Grade | Oral Cavity |

|---|---|

| 0 (no findings) | No special findings |

| 1 (low findings) | ≤ 2 low-grade abnormalities |

| 2 (medium findings) | Medium-grade abnormalities or ≤ 4 low-grade abnormalities |

| 3 (high findings) | High-grade abnormalities or > 4 low-grade abnormalities |

| Oral cavity Score | No. Horses (%, of 54) |

ESGD Score (0-4) |

No. Horses (%, of 54) |

EGGD Score (0-3) |

No. Horses (%, of 53) |

Gastric pH | No. Horses (%, of 52) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 (1.9) | ||||||

| 2 | 11 (21.2) | ||||||

| 0 | 8 (14.8) | 0 | 9 (16.7) | 0 | 22 (41.5) | 3 | 3 (5.8) |

| 1 | 20 (37.0) | 1 | 15 (27.8) | 1 | 22 (41.5) | 4 | 6 (11.5) |

| 2 | 17 (31.5) | 2 | 10 (18.5) | 2 | 8 (15.1) | 5 | 9 (17.3) |

| 3 | 9 (16.7) | 3 | 16 (29.6) | 3 | 1 (1.9) | 6 | 12 (23.1) |

| 4 | 4 (7.4) | 7 | 4 (7.7) | ||||

| 8 | 5 (9.6) | ||||||

| 9 | 1 (1.9) |

| Non specific – mild dental disorders | Moderate – severe dental disorders | p value (Chi² test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

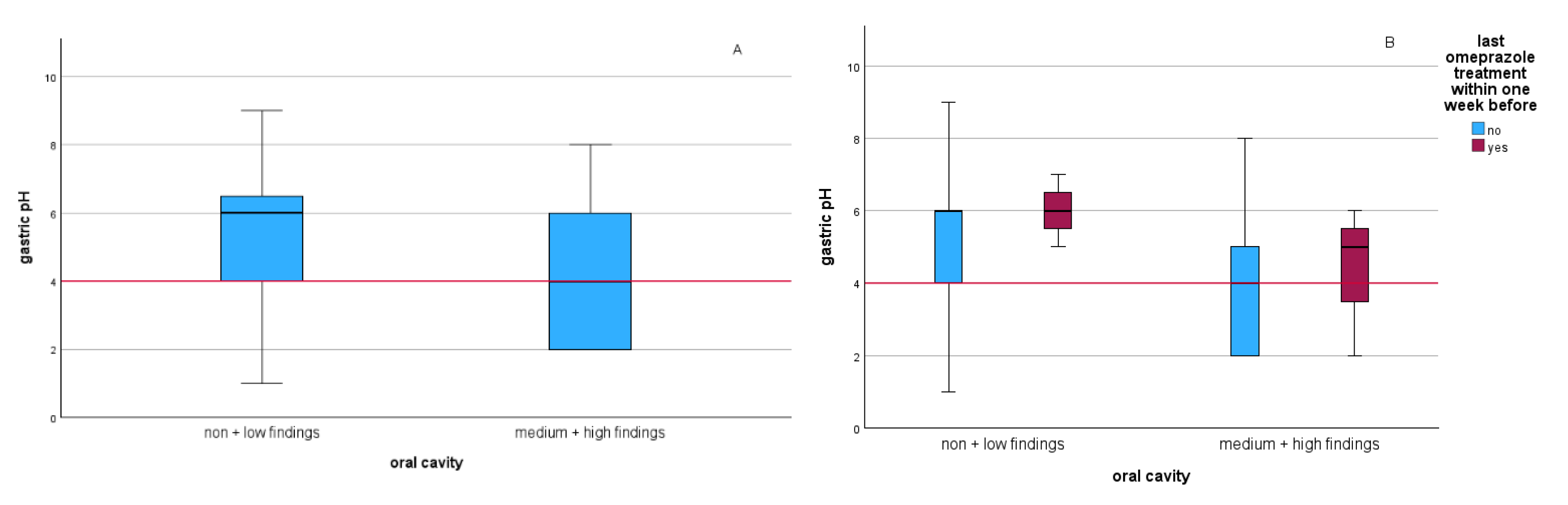

| pH 1-4 | 8/21 (38.1%) | 13/21 (61.9%) | 0.100 |

| pH 5-9 | 19/31 (61.3%) | 12/31 (38.7%) | |

| ESGD ≤ 1/4 | 14/24 (58.3%) | 10/24 (41.7%) | 0.394 |

| ESGD ≥ 2/4 | 14/30 (46.7%) | 16/30 (53.3%) | |

| EGGD ≤ 1/3 | 23/44 (52.3%) | 21/44 (47.7%) | 0.857 |

| EGGD ≥ 2/3 | 5/9 (55.6%) | 4/9 (44.4%) |

| First Examination | Second (Third) Examination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horse ID | ESGD (0-4) | EGGD (0-3) | ESGD (0-4) | EGGD (0-3) |

| 2* g | 4 | 2 | 1** | n.a. |

| 5 g | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1*** |

| 15 g | 3 | 1 | 0** | 0*** |

| 25 e | 3 | 1 | 0** | 1 |

| 32 g | 4 | 0 | 4 (2**) | 0 (0) |

| 34 e | 4 | 1 | 2** | 1 |

| 35* e | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 39 g | 3 | 1 | 0** | 1 |

| 50 e | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).