3.1. Experimental Results of CNN Data Point Feature Extraction

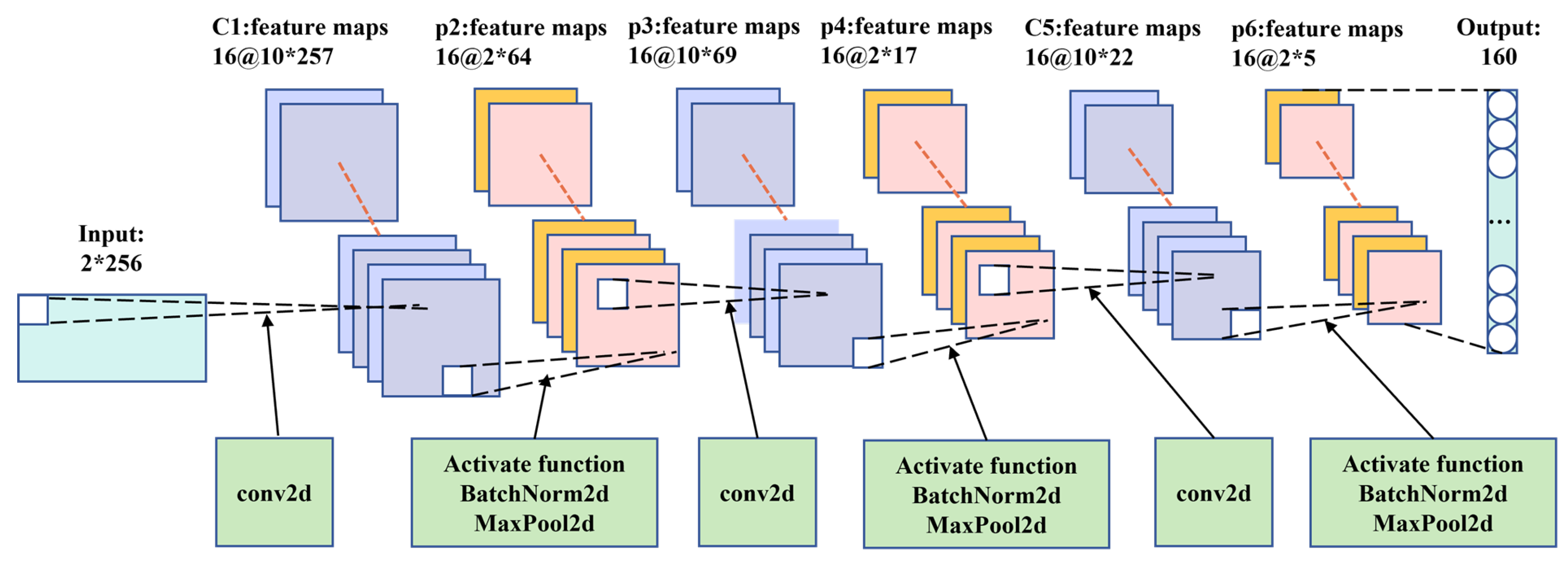

In this paper, according to the multi-layer feature extraction model proposed by [

27], a three-layer CNN model was built to initially extract the deep features of data points to represent a single data point.The model was validated using data sets from the Bearing Data Center at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU)[

28].

Table 3 shows the relevant parameters selected using the grid search method, and the relevant hyperparameters finally determined by the model through the grid search method.The data set is shown in

Table 5.All CWRU data are shown in

Table 4. It can be seen from the table that there are four types of data under the four working conditions: normal, inner ring damage, outer ring damage and ball damage. We represent all damage data as 1 and normal data as 0. At the same time, the data collected on the corresponding bearing in each file is for a period of time, so we take 256 data as one data point to divide all the data into multiple sample points for model training.

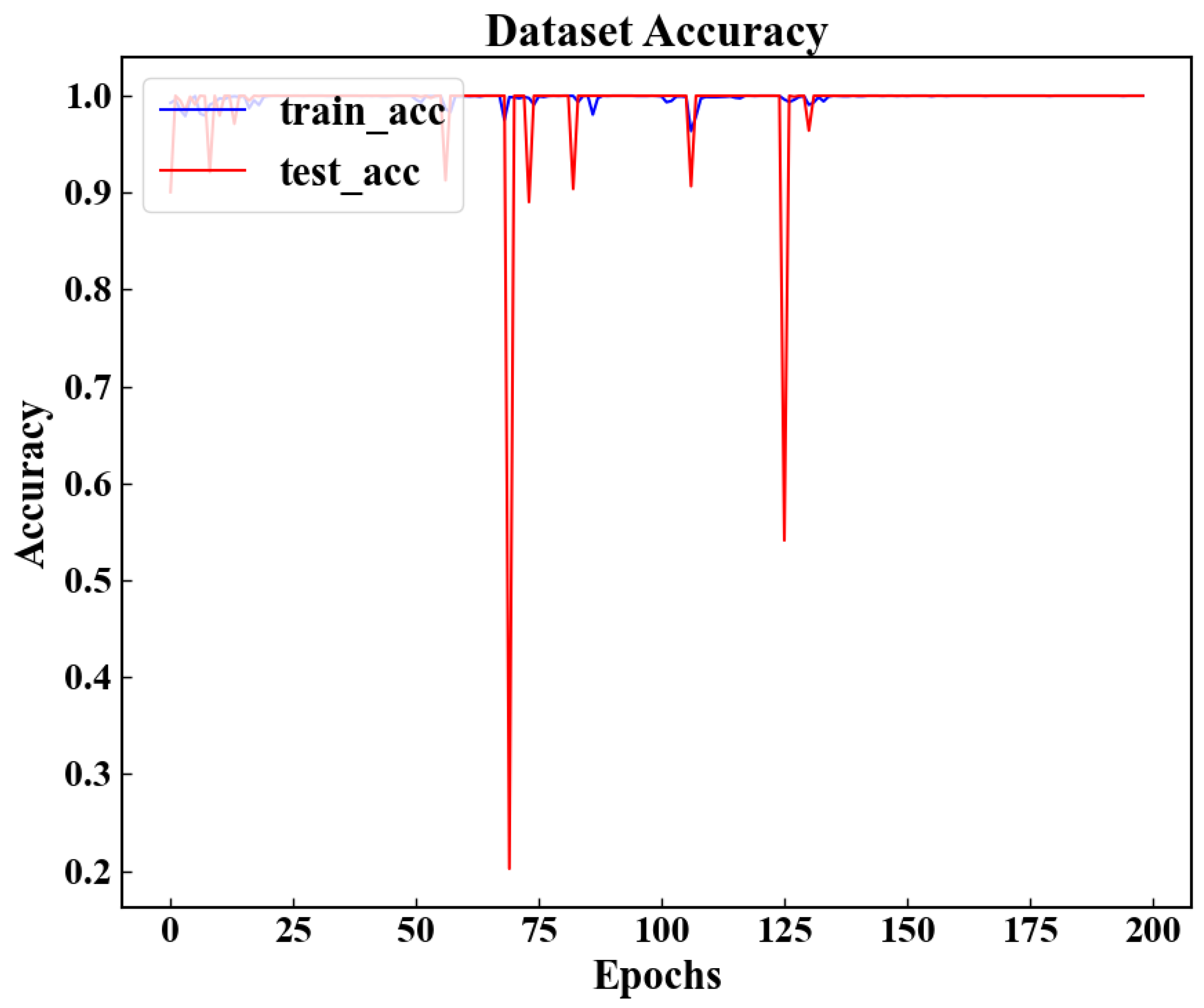

As can be seen from

Table 5, the accuracy of the model on the training set and the test set reaches 100%. To further test the performance of the model, we tested the data sets under conditions 2, 3 and 4 with the model, and recorded the experimental results in Table 5.As can be seen from the table, for data sets under different conditions, the prediction accuracy of the model for fault data reached 100%, and for normal data sets, it also had a high accuracy (due to the small amount of data of normal samples, the prediction accuracy of the model for normal samples under different conditions did not reach 100%). At the same time, it can be seen from

Figure 6 that when the model is trained for about 140 rounds, the model becomes stable and the prediction accuracy of the training set and test set reaches 100%.Combined with

Table 5 and

Figure 6, it can be shown that the model can mine the deep features of a single data point.

To further verify the effectiveness of the model in extracting the deep features of data points, we used the FEMTO-ST bearing dataset to train the above model. The FEMTO-ST bearing data set is a life-cycle data set, and the data itself does not have fault labels, so we label the data according to the bearing fault point (FOT) proposed by [

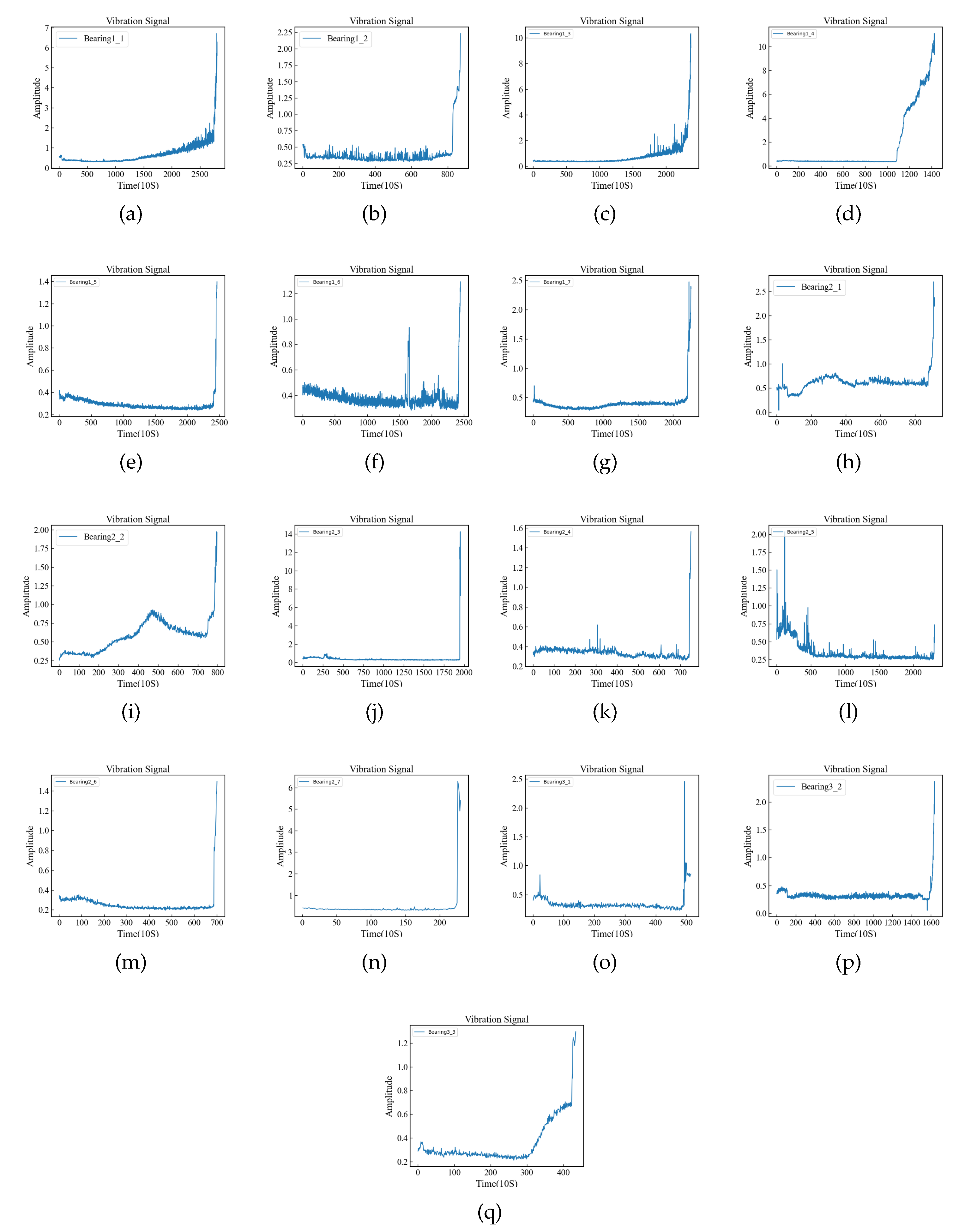

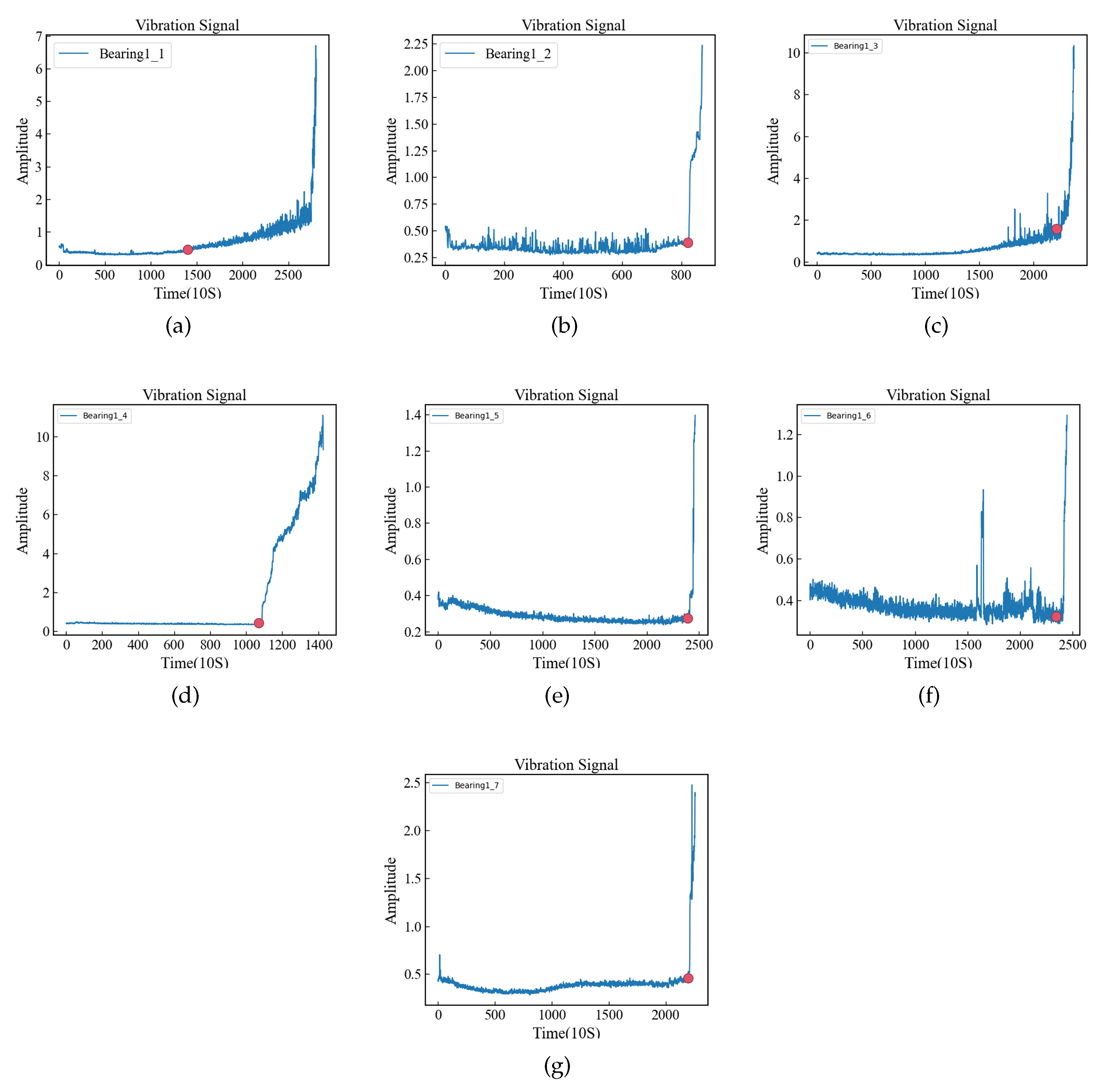

10]. At the same time, the amplitude of the data can better reflect the running state of the bearing, so we select the relevant FOT points according to the amplitude of the data. The amplitude of the data is shown in

Figure 7. Data before the FOT point is a normal sample (assigned 0), while data after the FOT point is a fault sample (assigned 1). The FOT points constructed by the two methods are shown in

Table 6, and the relevant experimental results are recorded in

Table 7.

As can be seen from

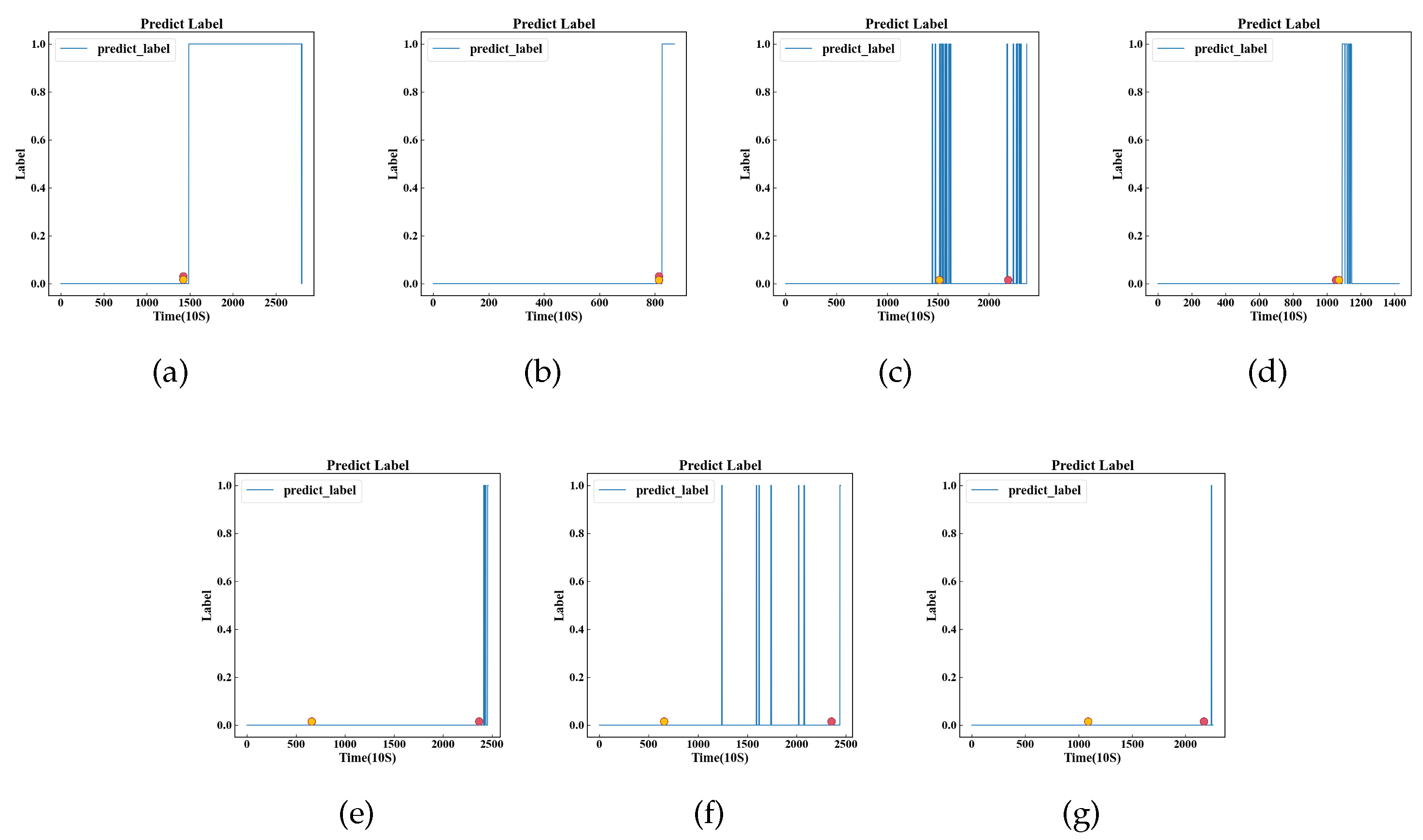

Table 7, the prediction performance of the model is significantly better according to the labels on the FOT points determined by the amplitude. In order to further determine the influence of FOT points, we plotted the predicted values of Bearing1_5, Bearing1_6 and Bearing1_7 models (three datasets with low accuracy) and the FOT points determined by the two methods in

Figure 8. The full amplitude FOT point plot is documented in

Appendices B.As can be seen from

Figure 8, the FOT points determined based on the amplitude are closer to the predicted results of the model.

From the experimental results, the FOT points determined by the amplitude can better reflect the performance of the model. The original data used in this experiment is unprocessed, while the data used by [

10]. is the time-frequency domain data obtained after pre-processing. The different feature distributions of the data lead to certain differences in the results. Through the above experiments, it can be determined that the built model can mine the deep features of a single data point, so that it can better represent the data point.

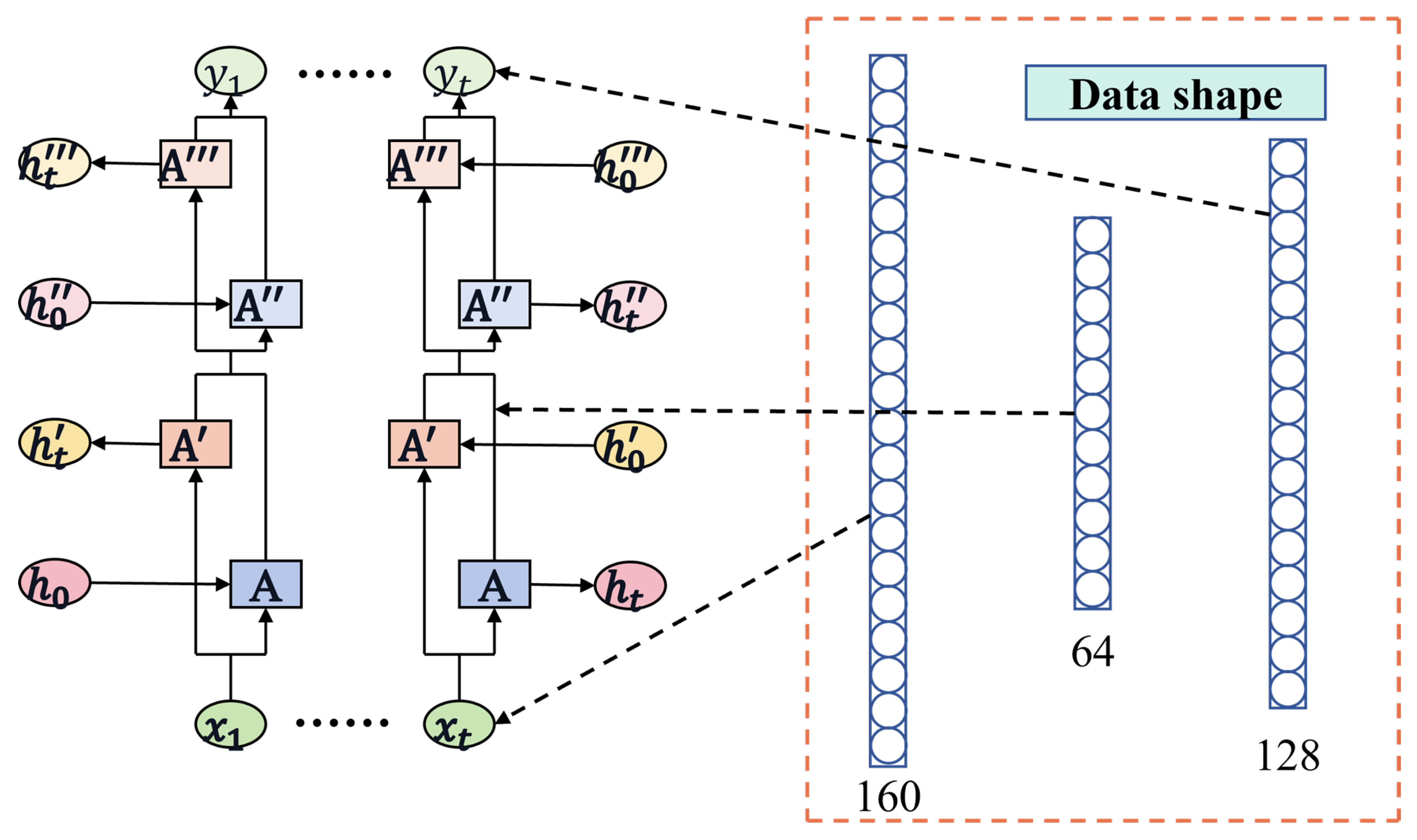

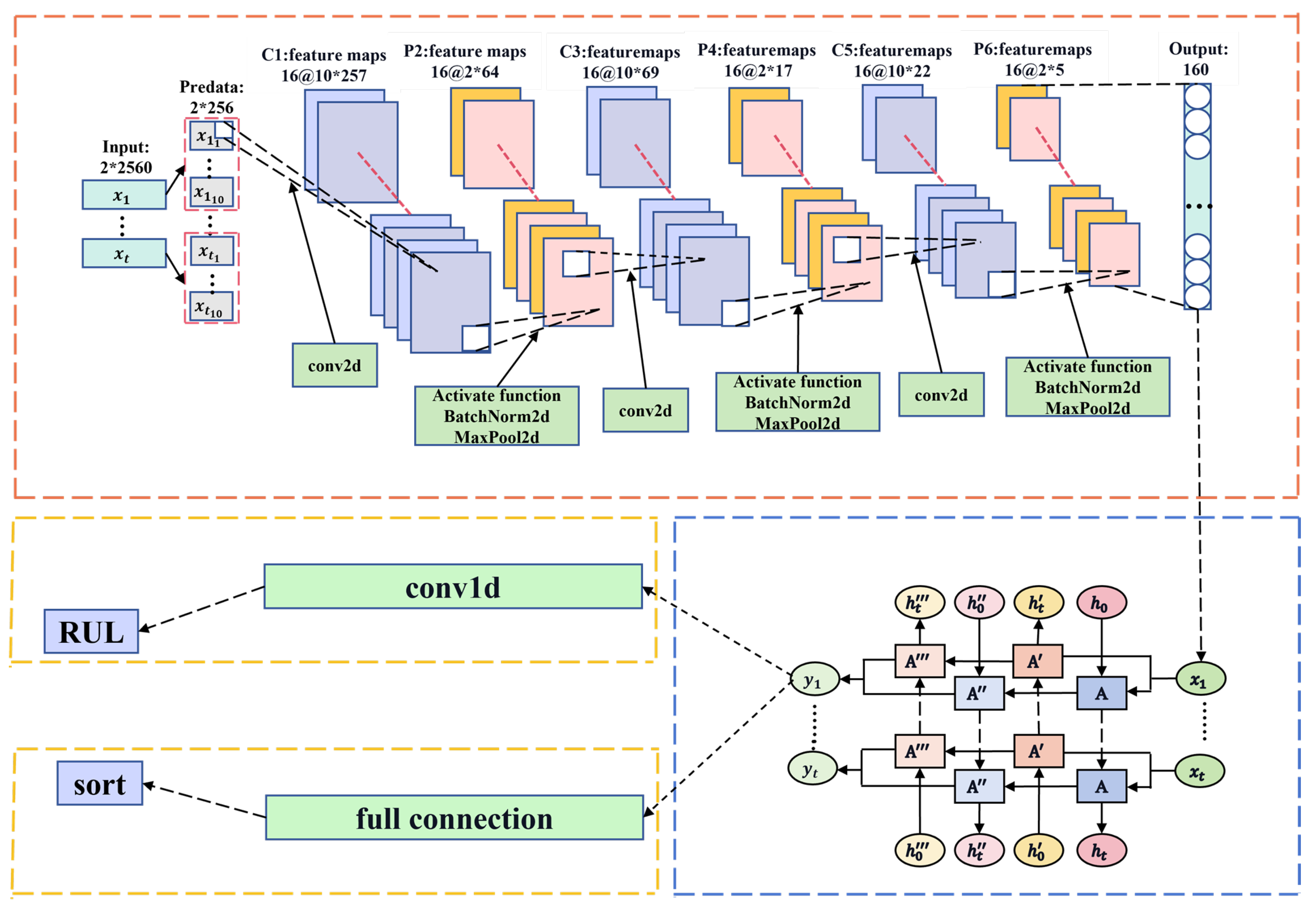

3.2. CNN-Bi-LSTM Model Experimental Results

In this experiment, trials were conducted using a model framework without domain adaptation. The method of using random search parameters was employed, ultimately determining the optimal parameters, which are listed in

Table 8. As can be seen from

Table 8, we used the Adam optimizer to adjust the learning rate, adjust the momentum, normalize the parameters, and prevent the model from overfitting.According to the characteristics of the label, we use the mean square error (MSE) as the loss function.To ensure a seamless connection between the CNN and LSTM layers, we used the batch size from the CNN as the sequence length for the LSTM network layer. To maintain the continuity of the time series, the batch size was sequentially rather than randomly partitioned.The entire experiment was conducted on a desktop computer equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12500 processor, running at 3.00 GHz, and utilizing the Windows 11 operating system.

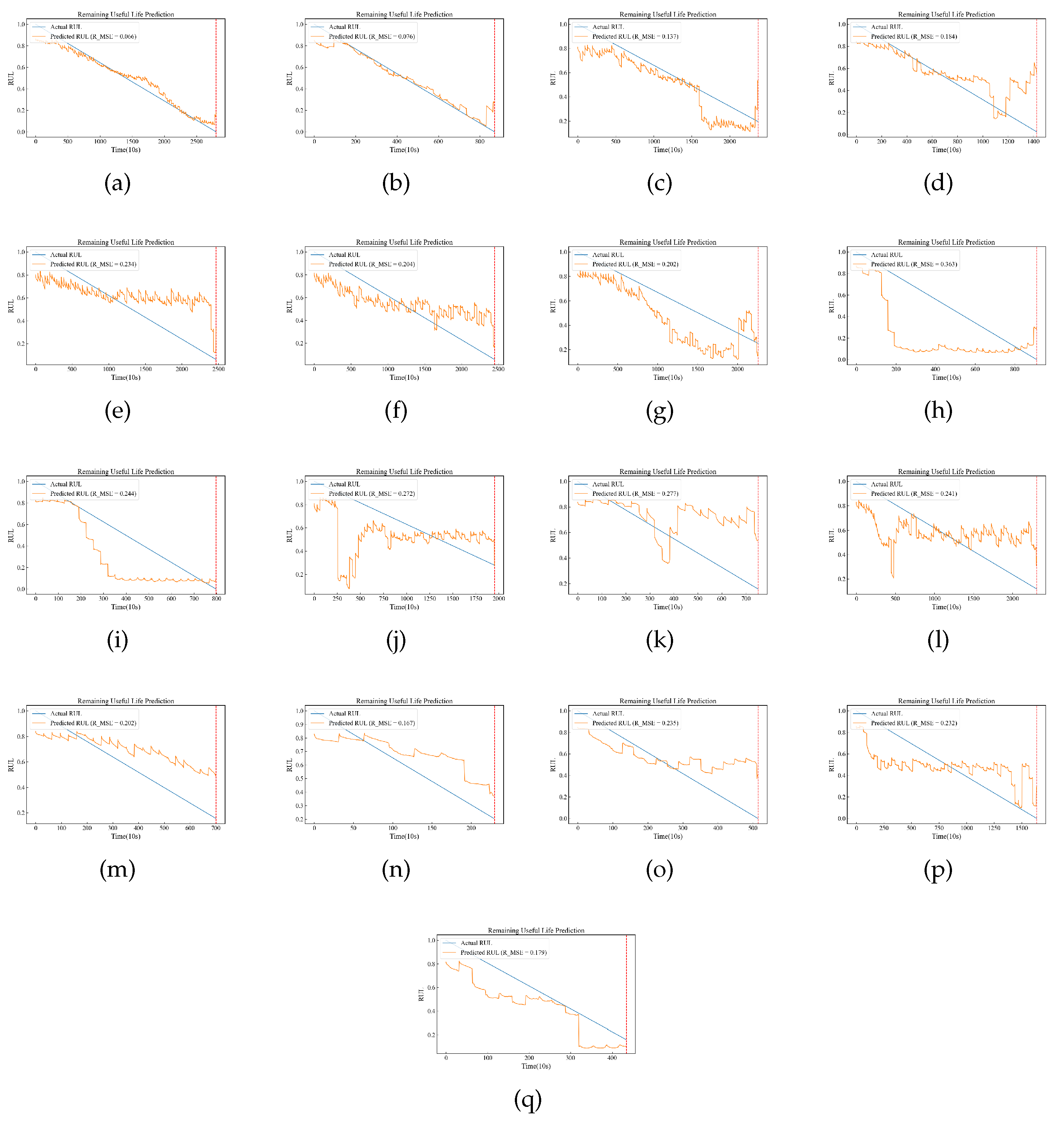

The experimental results are shown in

Figure 9, where a–h represent the RUL for Bearing1_1, Bearing1_2, Bearing1_3, Bearing1_4, Bearing2_1, Bearing2_2, Bearing3_1, and Bearing3_2, respectively.Model predictions for all data sets in the three conditions are recorded in

Appendices C.

In this experiment, the training set consisted of datasets Bearing1_1 and Bearing1_2 under operating condition one (OC1), while the remaining datasets served as the test set. Due to the varying lifespans of the datasets, direct lifespan values could not be used as training labels. Instead, we utilized a Health Indicator (HI) normalized between 0 and 1 for model training. From Fig.9, it can be observed that the model performed well with the training data set closely fitting the model. However, there were significant errors toward the end of the data due to limitations in the network structure. To ensure proper training, the dataset could not be fully partitioned, resulting in the exclusion of end-data points from the training. Consequently, the prediction performance for these end-data points was suboptimal, although the errors were controlled within an acceptable range. Furthermore, the performance of the test set for OC1 was notably better than those for OC2 and OC3. As shown in Fig.2, there were significant variations in the vibration data between different operating conditions and within similar conditions. The test set for OC1 exhibited satisfactory results, whereas for OC2, the model predicted stable labels during certain periods, indicating consistent degradation trends and minimal vibration fluctuations. Similarly, this pattern was observed for OC3. Overall, the test set predictions under the three operating conditions were satisfactory. The performance of the end-data points was suboptimal, similar to that of the training set, although within an acceptable range.

Table 9 presents the evaluation metrics used to compare our model with a published I-DCNN [

29] model and MCNN [

30] model. It can be observed from the table that our method achieved better results for most of the tested samples.

Time series features play an important role in RUL prediction. Therefore, we use different temporal basic models (such as BI-LSTM, LSTM, RNN, Bi-RNN, GRU, BI-GRU, etc.) to mine temporal features between data for RUL prediction. We only replace the network layer in the model that extracts the temporal features between data, and keep other parameters unchanged to carry out relevant experiments. The experimental results are recorded in

Table 10.At the same time, all data sets under the three working conditions obtained by the model are recorded in

Appendix A.

As can be seen from

Table 10, the data set with the OC1 has the best prediction effect on the Bi-LSTM model, and its NRMSE is 0.1576. At the same time, most of the data sets show good performance in the BI-LSTM model, so we finally use the Bi-LSTM neural network model to mine the timing features between the data.

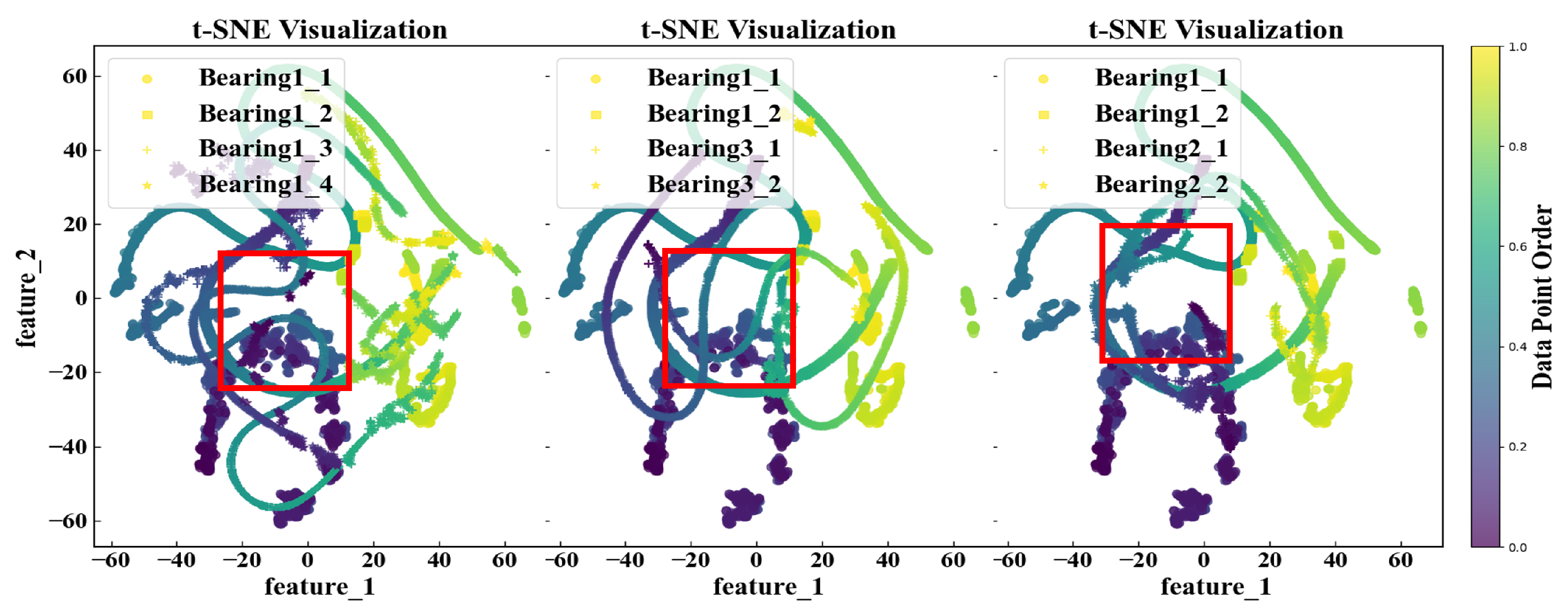

In addition, we observed a significant increase in the test set metrics for OC2 and OC3, indicating a decrease in predictive performance. This highlights the impact of operating conditions on the generalizability of the model. Beyond the training datasets (Bearing1_1 and Bearing1_2), we selected two samples from the test sets for each OC (Bearing1_3, Bearing1_4, Bearing2_1, Bearing2_2, Bearing3_1, and Bearing3_2) and examined the feature distribution using t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) downscaling. The results are displayed in

Figure 10.

We can observe from the feature distribution plots that the feature distribution of the test set closely aligns with that of the training set. However, certain datasets show a high concentration of points, suggesting that the bearings were in a stable state during periods with similar vibration data. Consequently, the predictions during these periods yielded similar results, reflecting a stable operational state of bearings. Meanwhile, it can be seen from the figure that some feature regions of Bearing1_1 and Bearing1_2 are similar, but their RUL values are completely different. As a result, the model cannot accurately predict the RUL value on the test set, which reduces the performance of the model.To further quantify the results, we computed the JS divergence to compare the distribution similarity of the different datasets. The results are summarized in

Table 11.

As can be seen from

Table 11, the JS divergence between Bearing1_3 and Bearing1_2 is small and their feature region is similar; the JS divergence between Bearing1_3 and Bearing1_2 is large, and their feature region is similar is low and their prediction performance is good. However, the JS divergence between Bearing2_1 and the two training sets is not large or small, and the prediction result is sub-optimal. At the same time, the similarity of feature regions between Bearing1_1 and Bearing1_2 is high.

Figure 10 further supports the effectiveness of the model in predicting the features of the data set. In addition,

Table 11 confirms significant differences between the source and target domains, which lead to suboptimal experimental results.

To enhance the performance of the base model, reduce the disparities between the source- and target-domain feature distributions, and achieve more accurate predictions, we employed domain-adaptation methods to refine the model and improve its predictive effectiveness.

3.3. Domain-Adaptation Model Experimental Results

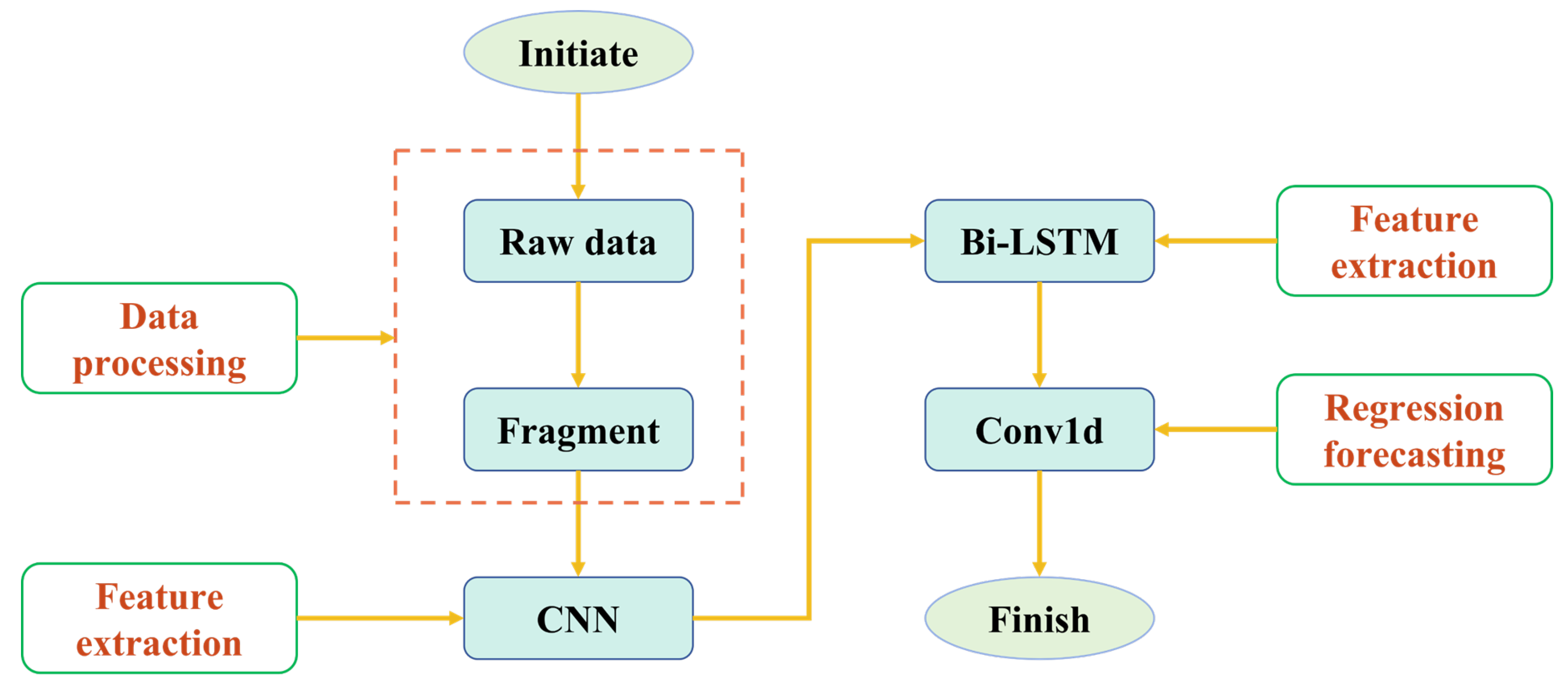

In this experiment, we implemented an adversarial domain-adaptation method based on the aforementioned base model, as depicted in

Figure 5. From the experimental results mentioned earlier, We found that the regression layer was the main factor affecting the prediction result. Therefore, we kept the parameters of the CNN and LSTM layers unchanged while resetting the parameters of the regression prediction network layers for retraining. The basic experimental information is summarized in

Table 12.

The evaluation metrics after domain adaptation are listed on

Table 13. From the table, it can be seen that the indicators for Bearing1_1, Bearing2_1, Bearing3_1 and Bearing3_2 noticeably decreased, while those for Bearing2_2 did not show significant changes. Overall, the model was proven effective in enhancing predictive performance.

Therefore, it can be demonstrated that domain-adaptation techniques can minimize the disparities in feature distributions and improve model performance. Additionally, when a bearing is in a stable state, the collected vibration data is similar, leading to similar RUL values predicted by the model.