Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

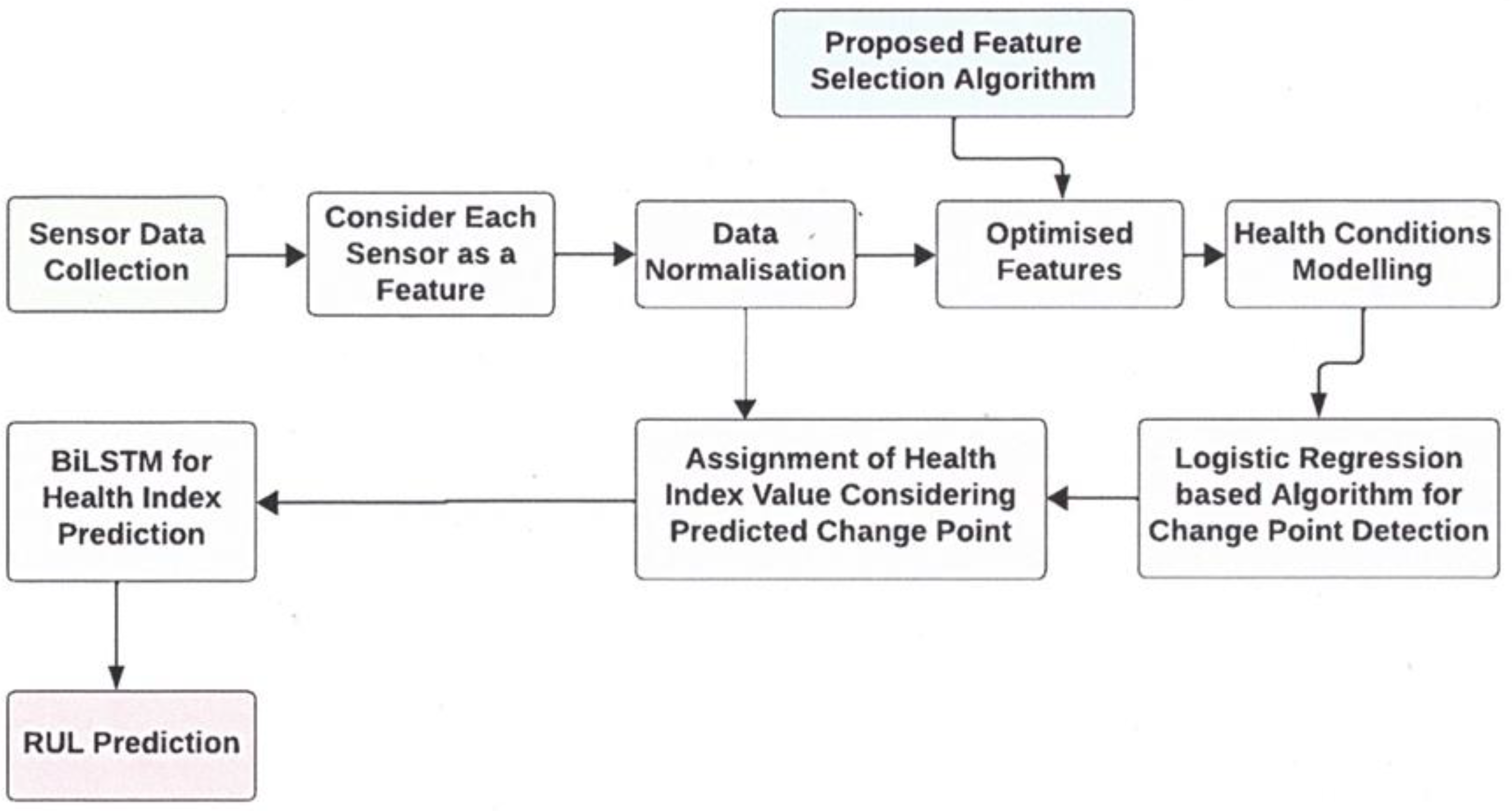

In the era of Internet of Things (IoT), remaining useful life (RUL) prediction of turbofan engines is crucial. Various deep learning (DL) techniques are proposed recently to predict RUL for such systems, have remained silent on the effect of environmental changes on machine reliability. This paper has proposed three-fold aims, (i) to identify the change point in RUL trend and pattern (ii) to select most relevant features, and (iii) to predict RUL with the selected features and identified change point. A two-stage feature selection algorithm was developed, followed by a change point identification mechanism and finally, a Bi-directional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) model has been designed to predict RUL. The study utilizes NASA’s C-MAPSS dataset to check the performance of the proposed methodology. The findings affirm that the proposed method enhances the stability of DL models, resulting in an approximate 30% improvement in RUL prediction compared to popular and cutting-edge DL models.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

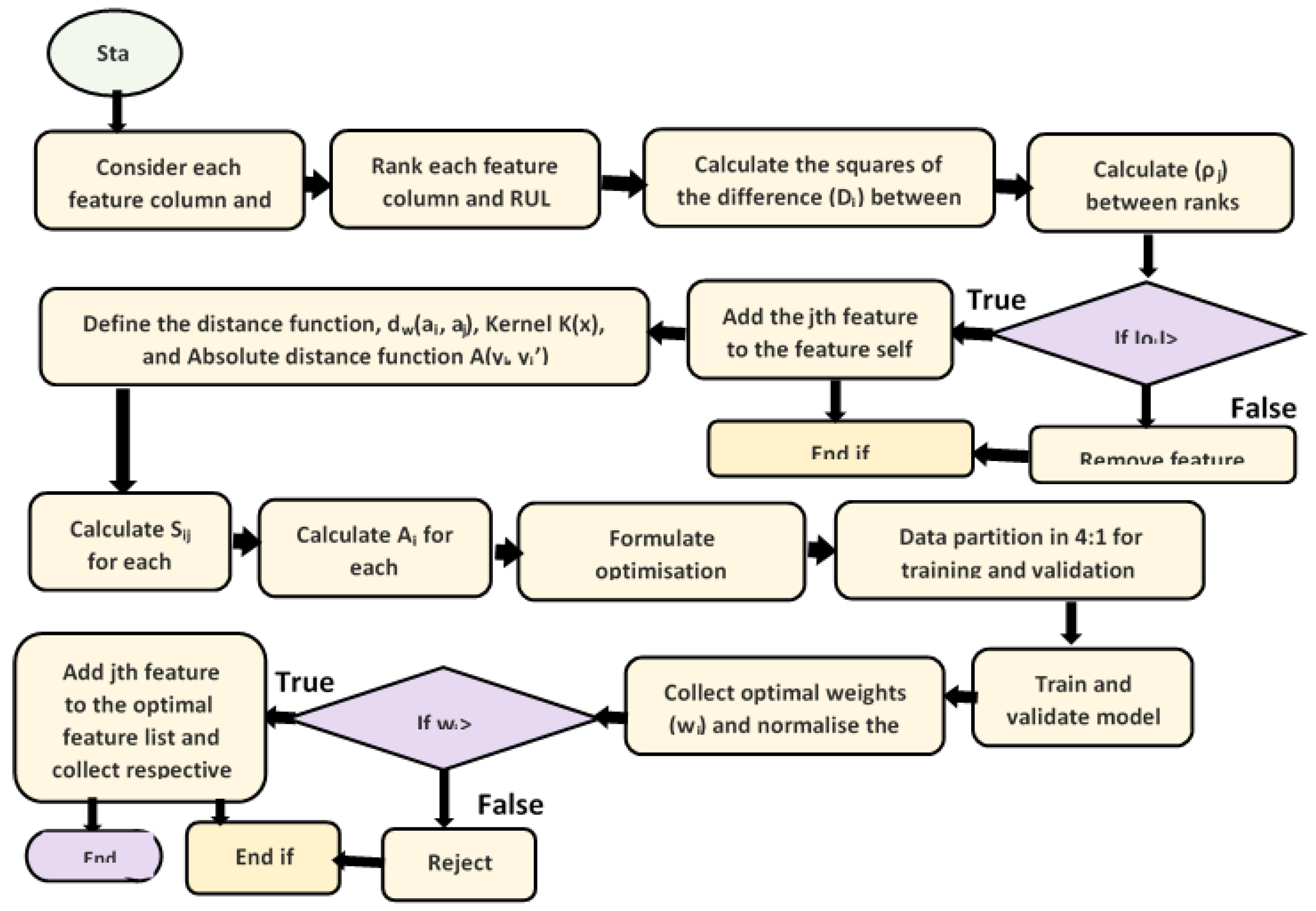

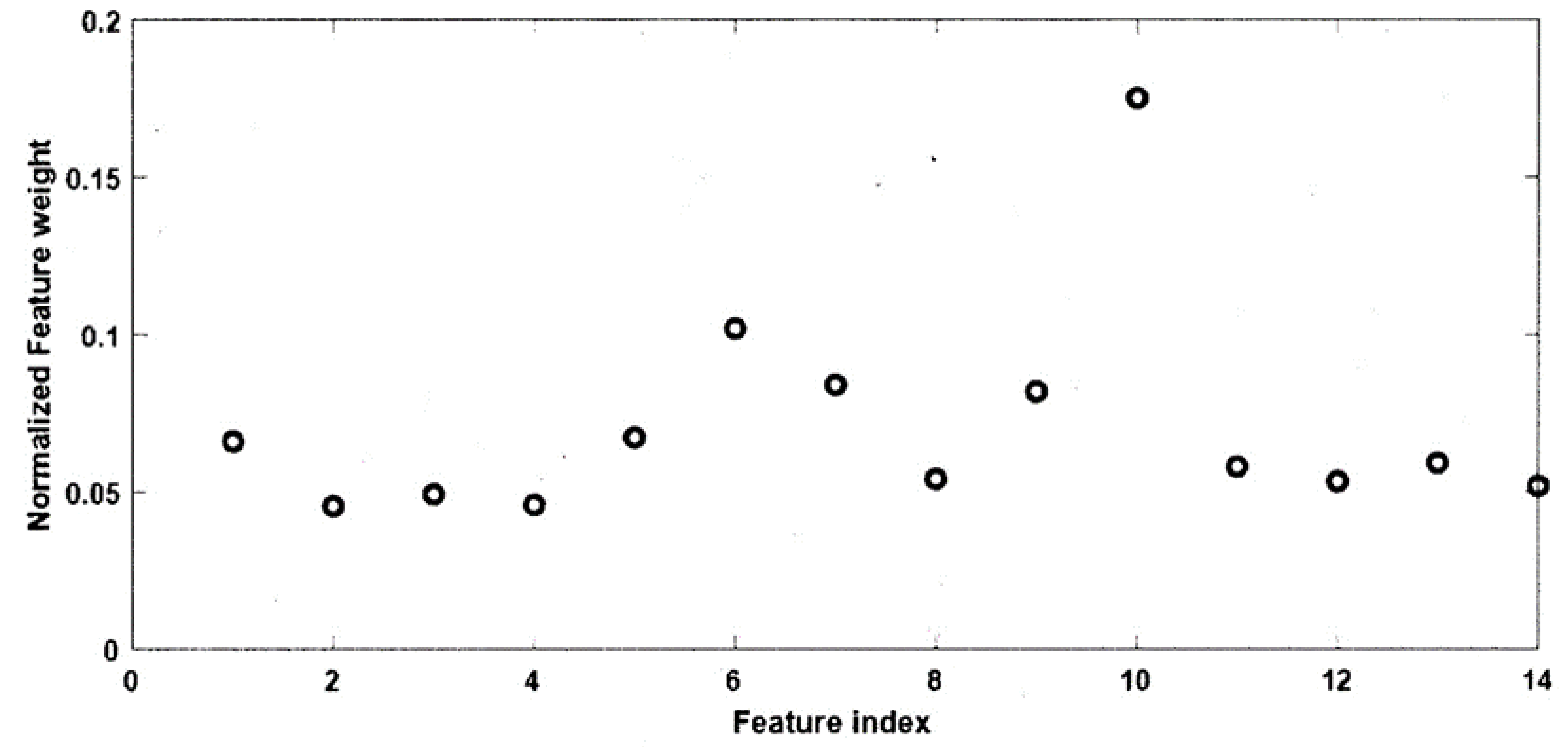

- Proposing a new feature selection algorithm to identify the most important features from all sensor data for RUL prediction. This proposed algorithm also keeps track of the feature weight corresponding to each important feature, which helps to predict the RUL later. The feature selection algorithm is a prerequisite to filter out the unnecessary sensor signals for RUL prediction.

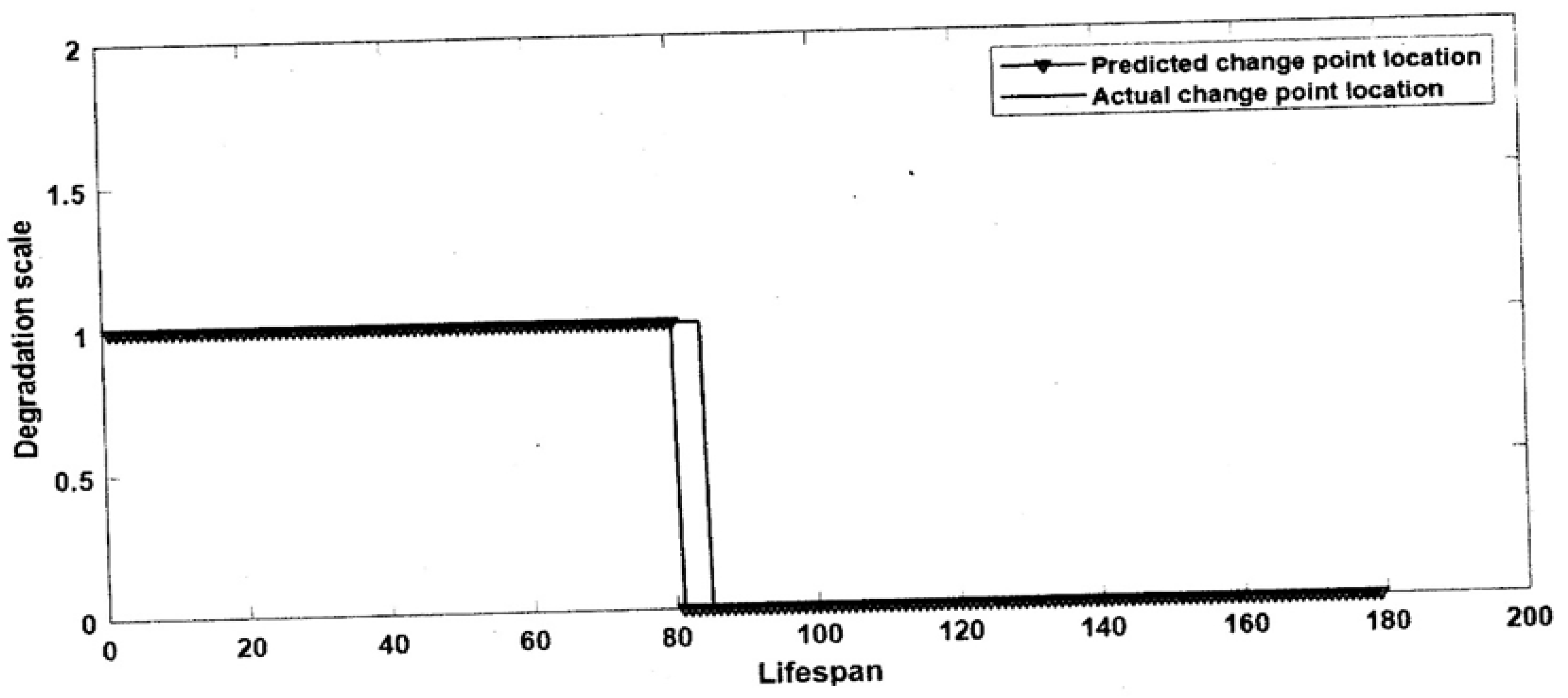

- Introducing a logistic regression-based algorithm for change point detection for each engine on the basis of their respective selected important features.

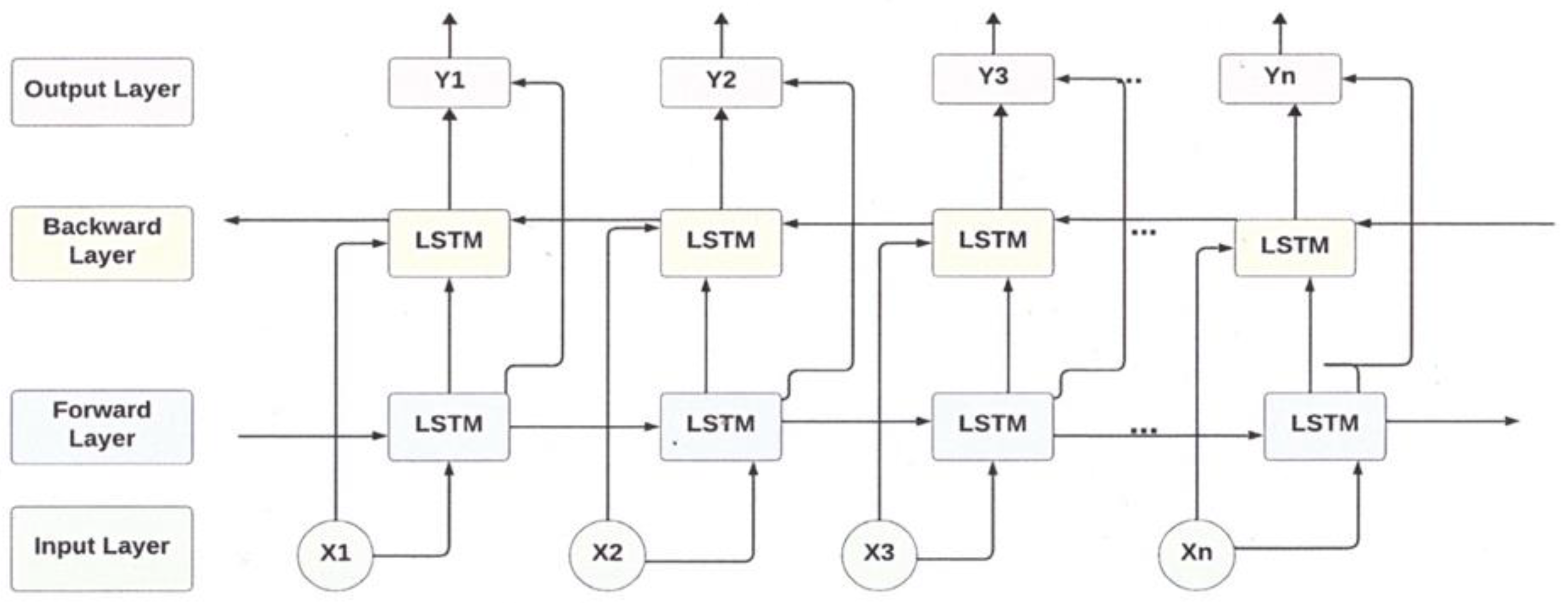

- Designing a BiLSTM network for prediction of RUL with the optimal number of sensors so that both long-term and short-term dependencies within the sensor can be characterized bidirectionally via the BiLSTM network. Therefore, historical information can be preserved as much as possible and used for health index as well as RUL prediction.

- Demonstrating the superior performance of the proposed methodology on the basis of C-MAPSS data and comparing the performances with some existing models.

2. Prerequisites

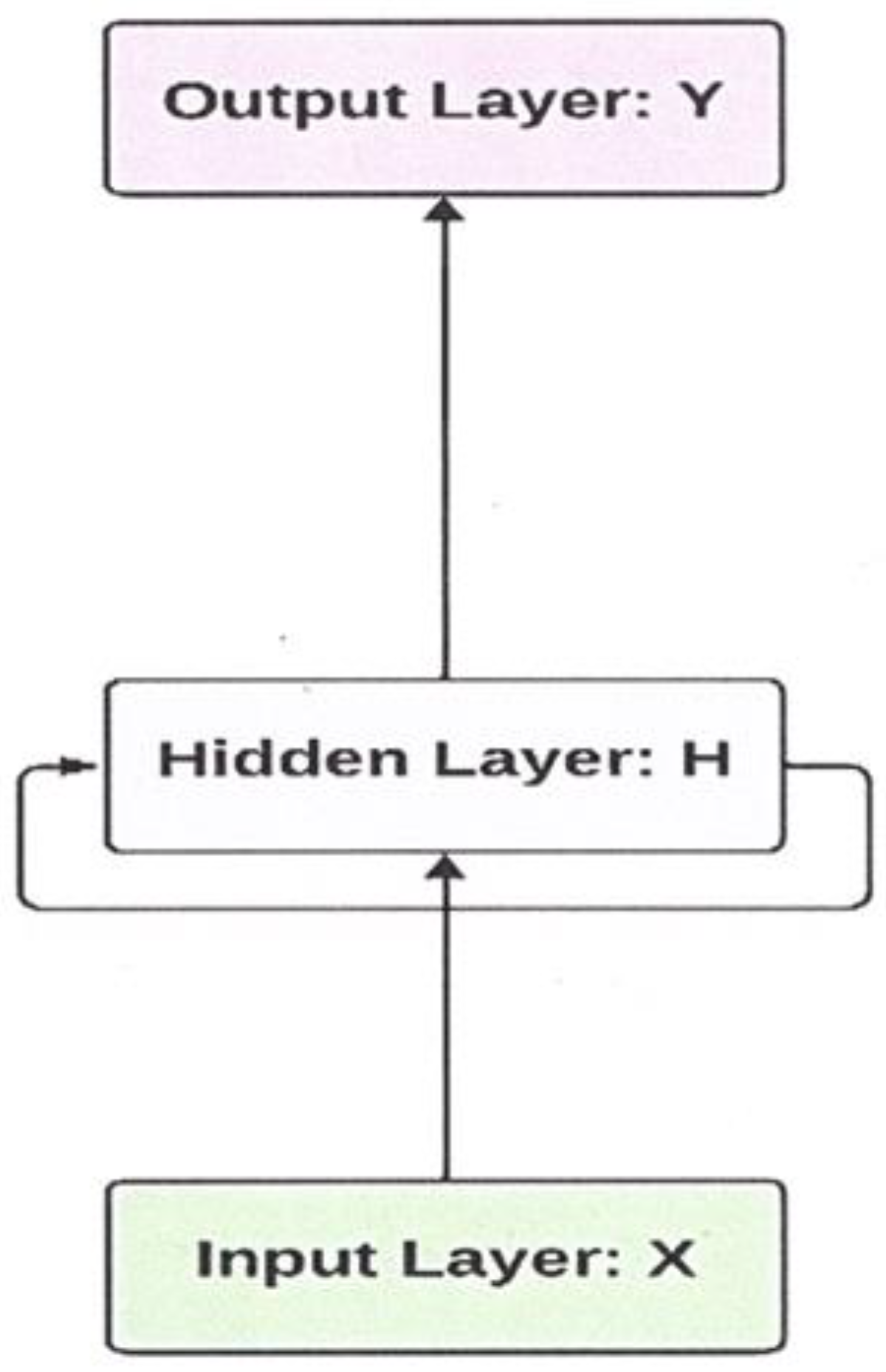

2.1. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

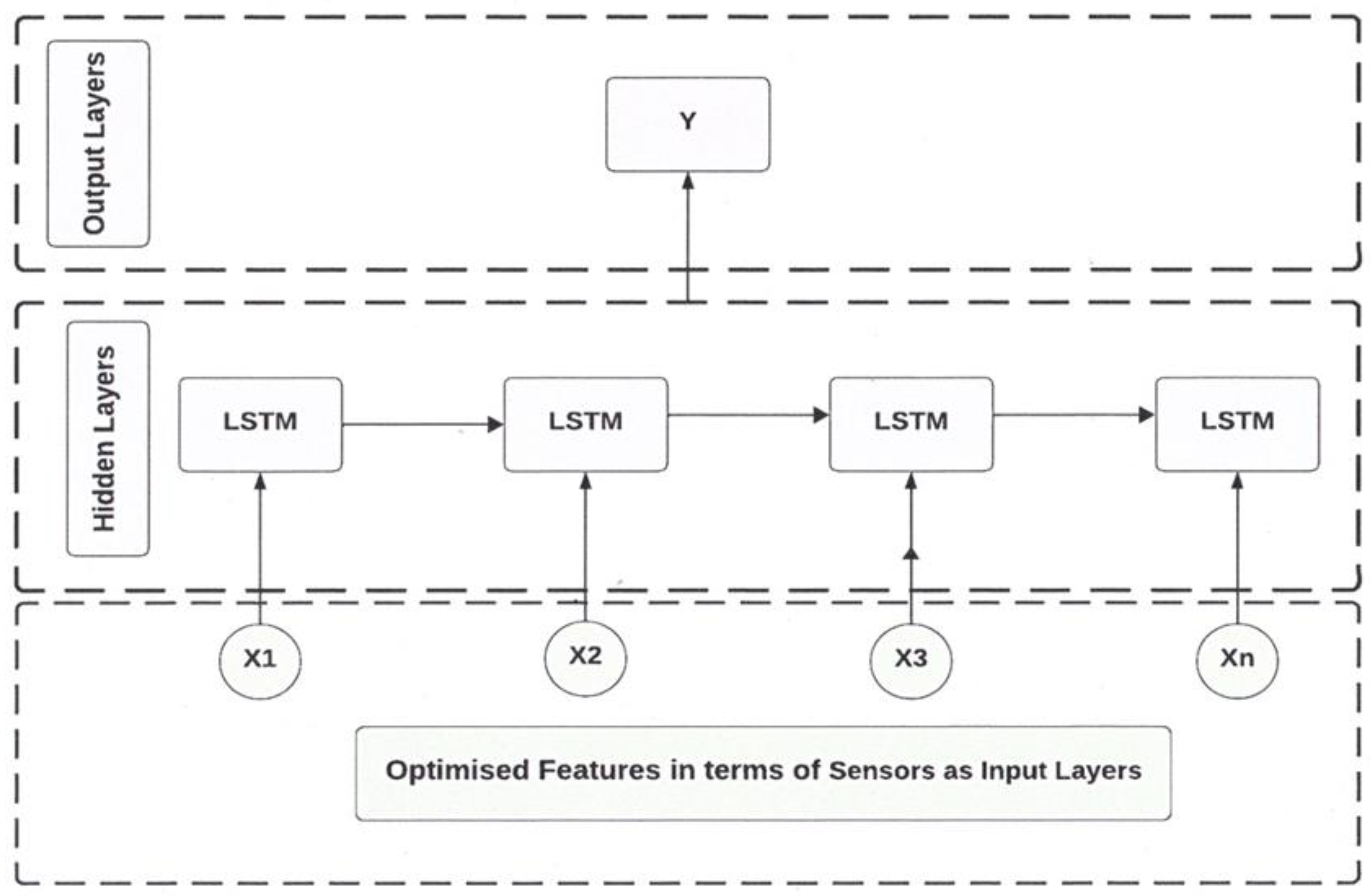

2.2. Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM)

2.2.1. Forget Gate

2.2.2. Input Gate

2.2.3. Output Gate

2.3. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)

3. Proposed Methodology

- normalization of the input features,

- optimal feature selection from all the sensors,

- change point detection for each turbofan engine,

- predict the health index of turbofan engines,

- RUL prediction based on the health index values for each turbofan engine.

3.1. Feature Normalization

3.2. Feature Selection

3.2.1. Proposed Two-Stage Feature Selection Algorithm

3.3. Change Point Detection

3.4. Health Index Value Prediction

3.5. RUL Prediction

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Implementation of Proposed Methodology

4.2. Performance Metrics

3.2.2. Root Means Square Error (RMSE)

3.2.2. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

3.2.1. Relative Percentage Error (RPE)

4.3. Performance Comparison and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, L.; Song, X.; Zhou, Z. Aircraft engine remaining useful life estimation via a double attention-based data-driven architecture. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Shen, J. A Novel Multi-hidden Semi-Markov Model for Degradation State Identification and Remaining Useful Life Estimation. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2012, 29, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, T.; Xia, T.; Chen, Z.; Pan, E. A CM&CP framework with a GIACC method and an ensemble model for remaining useful life prediction. Comput. Ind. 2022, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H. Remaining useful life prediction of aero-engine enabled by fusing knowledge and deep learning models. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Peng, Y. Quantitative selection of sensor data based on improved permutation entropy for system remaining useful life prediction. Microelectron. Reliab. 2017, 75, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, Z.; Salahshoor, K.; Farsi, B.; Eicker, U. A New Hybrid Model for RUL Prediction through Machine Learning. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2021, 21, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zheng, B.; Li, Z.; Gao, H. Optimal maintenance period and maintenance sequence planning under imperfect maintenance. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeardley, A.S.; Ejeh, J.O.; Allen, L.; Brown, S.F.; Cordiner, J. Integrating machine learning techniques into optimal maintenance scheduling. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, O.O.; Cody, R.A.; Hyland-Wood, D.; McAree, P.R. A relative entropy based feature selection framework for asset data in predictive maintenance. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 145, 106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aheleroff, S.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Aristizabal, M.; Velásquez, J.P.; Joa, B.; Valencia, Y. IoT-enabled smart appliances under industry 4.0: A case study. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2020, 43, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, E.; Khorasani, K. Data-driven fault detection, isolation and estimation of aircraft gas turbine engine actuator and sensors. In: Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, C.; Lasheras, F.S.; Roca-Pardiñas, J.; Juez, F.J.d.C. A hybrid ARIMA–SVM model for the study of the remaining useful life of aircraft engines. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 346, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, Y. Convolutional neural network-based hidden Markov models for rolling element bearing fault identification. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2017, 144, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; Liu, D.; Peng, Y. Data-Driven Remaining Useful Life Prediction Considering Sensor Anomaly Detection and Data Recovery. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 58336–58345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Shao, X.; Deng, C.; Liu, C. Multi-sensor information fusion for remaining useful life prediction of machining tools by adaptive network based fuzzy inference system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 68, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Z. Stages prediction of the remaining useful life of rolling bearing based on regularized extreme learning machine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2021, 235, 6599–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, Q.; Sun, J.-Q. Remaining useful life estimation in prognostics using deep convolution neural networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 172, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zio, E. Remaining useful life prediction using multi-scale deep convolutional neural network. Applied Soft Computing Journal 2020, 89, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, D.; Huang, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Aero-engine remaining useful life prediction method with self-adaptive multimodal data fusion and cluster-ensemble transfer regression. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Three-stage feature selection approach for deep learning-based RUL prediction methods. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 1223–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.; Chopra, S.; Lad, B.K. Multiple failure behaviors identification and remaining useful life prediction of ball bearings. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 30, 1795–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchaiah, S.; Shakya, P. Bearing fault diagnosis and prognosis using data fusion based feature extraction and feature selection. Measurement 2021, 188, 110506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sankavaram, C.; Zhou, S. RUL Prediction for Individual Units Based on Condition Monitoring Signals With a Change Point. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2014, 64, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wu, J.; Das, D.; Tseng, T.-L. Degradation modeling and RUL prediction using Wiener process subject to multiple change points and unit heterogeneity. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 176, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chehade, A. A dual-LSTM framework combining change point detection and remaining useful life prediction. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2020, 205, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Zhao, Y., Addepalli, S. Remaining useful life prediction using deep learning approaches: A review. In: Procedia Manufacturing. pp. 81–88. Elsevier B.V. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Djeziri, M.; Benmoussa, S.; Sanchez, R. Hybrid method for remaining useful life prediction in wind turbine systems. Renew. Energy 2018, 116, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, T.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y. Remaining Useful Life Prediction by Fusing Expert Knowledge and Condition Monitoring Information. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2020, 17, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Zheng, P.; Xia, L.; Liu, T. Transformer-based hierarchical latent space VAE for interpretable remaining useful life prediction. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, N.; Jia, F.; Lei, Y.; Lin, J. A recurrent neural network based health indicator for remaining useful life prediction of bearings. Neurocomputing 2017, 240, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Wieczorek, M.; Siłka, J. BiLSTM deep neural network model for imbalanced medical data of IoT systems. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 141, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, G.S.; Panambilly, A.; Schwung, A.; Ding, S.X. Bidirectional deep recurrent neural networks for process fault classification. ISA Trans. 2020, 106, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jing, H.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Q. Gated Recurrent Unit Based Recurrent Neural Network for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Nonlinear Deterioration Process. 2019, 185, 372–382. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S. "Long Short-term Memory." Neural Computation MIT-Press (1997).

- Sayah, M.; Guebli, D.; Noureddine, Z.; Al Masry, Z. Deep LSTM Enhancement for RUL Prediction Using Gaussian Mixture Models. Autom. Control. Comput. Sci. 2021, 55, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Gonçalves, G. Remaining Useful Life prediction and challenges: A literature review on the use of Machine Learning Methods. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensarioğlu, K.; İnkaya, T.; Emel, E. Remaining Useful Life Estimation of Turbofan Engines with Deep Learning Using Change-Point Detection Based Labeling and Feature Engineering. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model name | Number of models | Number of hidden layers with number of neurons | Learning rate | Number of epochs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bidirectional long short-term memory | Single model | 2 and 128 | 0.05 | 60 |

| long short-term memory | Single model | 2 and 128 | 0.05 | 60 |

| Elman neural network | Single model | 2 and 128 | 0.05 | 60 |

| Artificial neural network | Single model | 1 and 128 | 0.05 | 60 |

| Ensemble model | 20 no of decision tree | ------- | ------- | ------- |

| Model name | RMSE | MAE | Percentage error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision tree1 | 97.58 | 81.32 | 52.20 |

| Support vector machine2 | 69.69 | 54.67 | 34.82 |

| Ensembling model3 | 88.65 | 73.52 | 42.98 |

| Artificial neural network4 | 83.69 | 69.95 | 45.68 |

| Elman neural network5 | 79.91 | 65.71 | 39.84 |

| LSTM6 | 64.72 | 51.01 | 17.27 |

| BiLSTM7 | 51.22 | 48.21 | 15.23 |

| Change point based BiLSTM8 | 26.80 | 31.16 | 11.18 |

| Feature selection with BiLSTM9 | 51.1 | 48.32 | 16.12 |

| Proposed model10 | 18.71 | 21.08 | 8.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).