Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Food Intake, Body Weight, and Body Composition

2.3. Cytokines, Leptin, and Insulin Levels in Serum

2.4. Microbiome Analysis

2.5. Lipid Content in Feces

3. Results

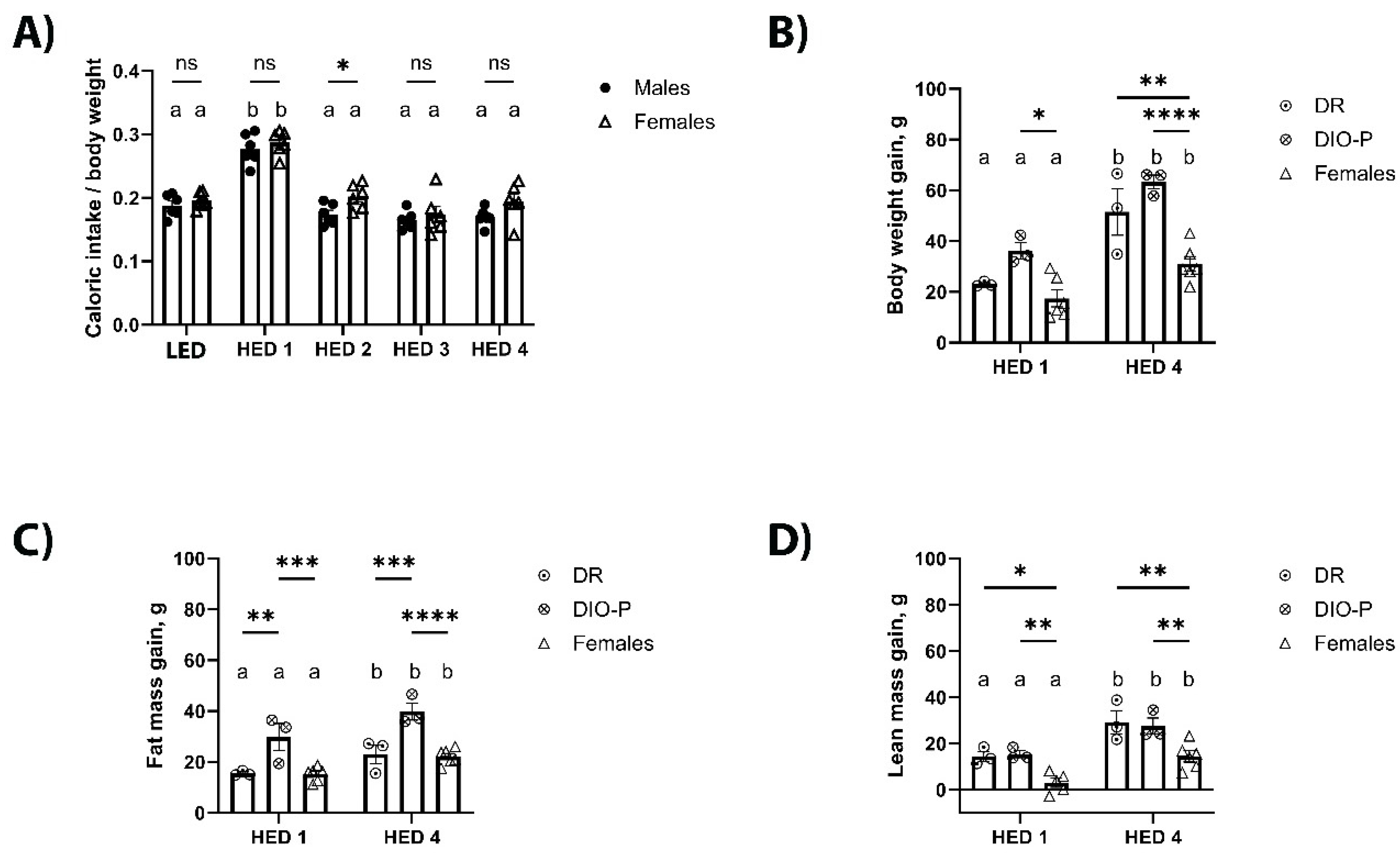

3.1. Consumption of a HED Diet Significantly Increased Body Weight and Fat Mass Accumulation

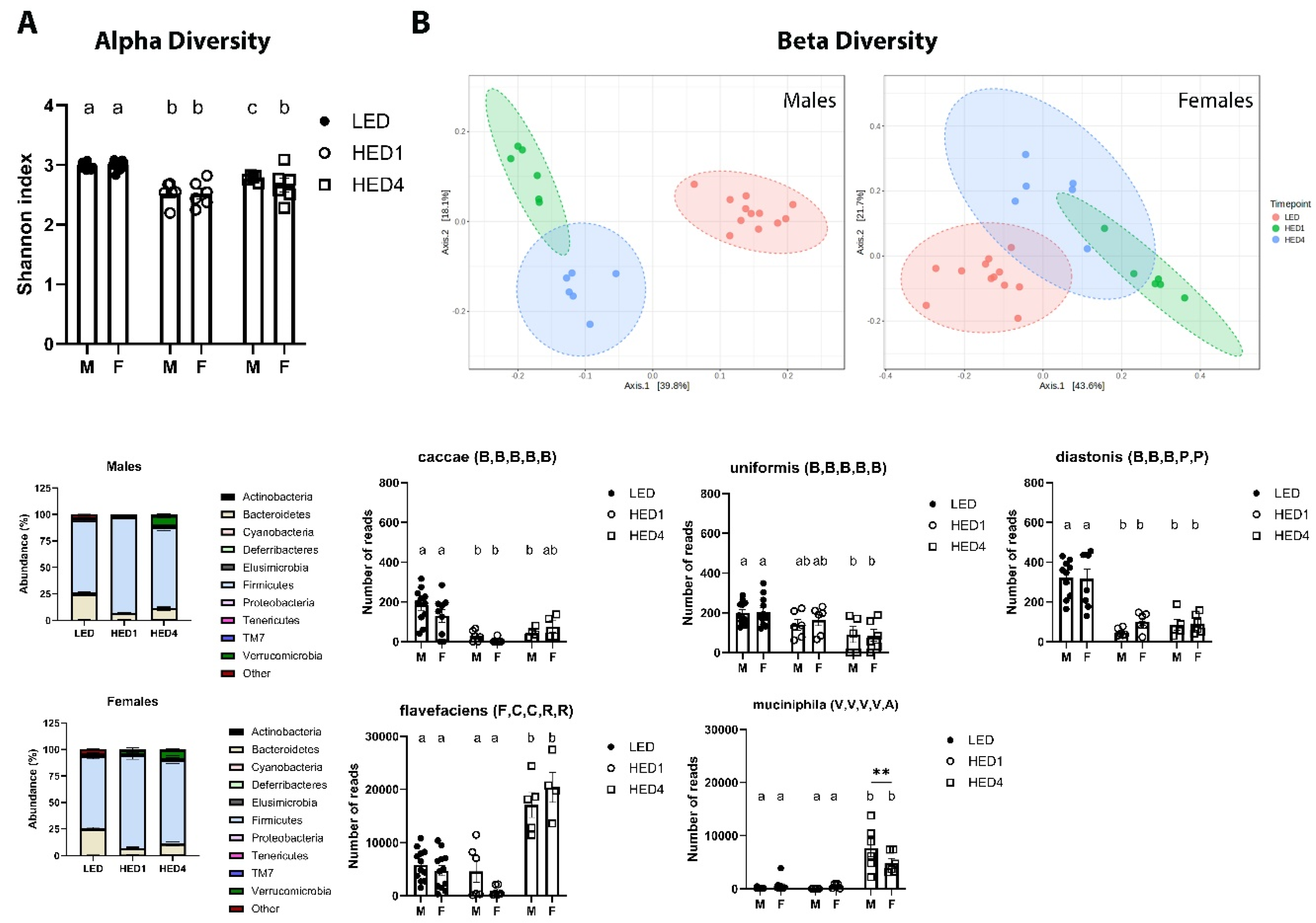

3.2. HED Decreased Microbial Diversity within a Week

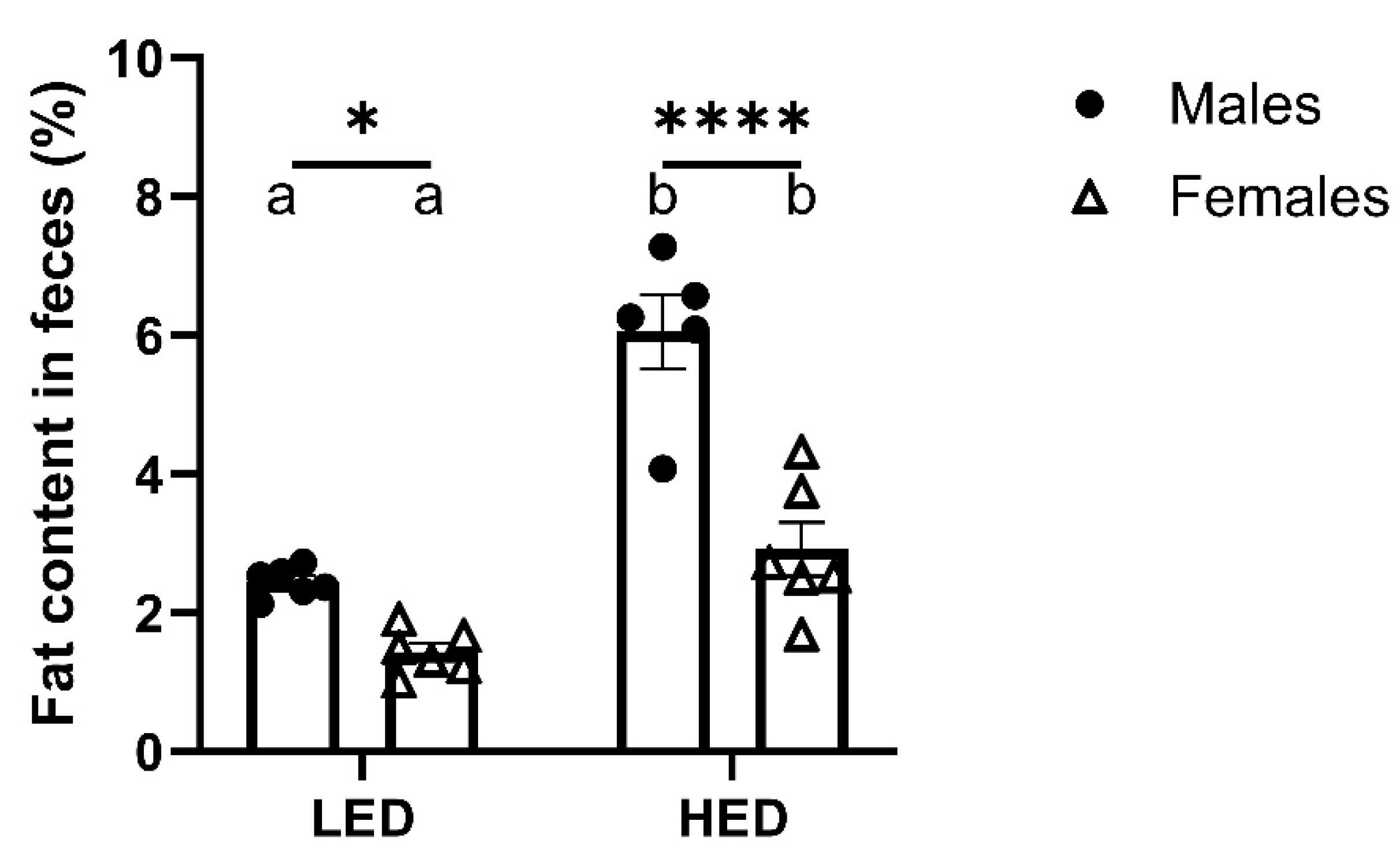

3.3. Male Rats Excrete More Fat in Their Feces Than Female Rats

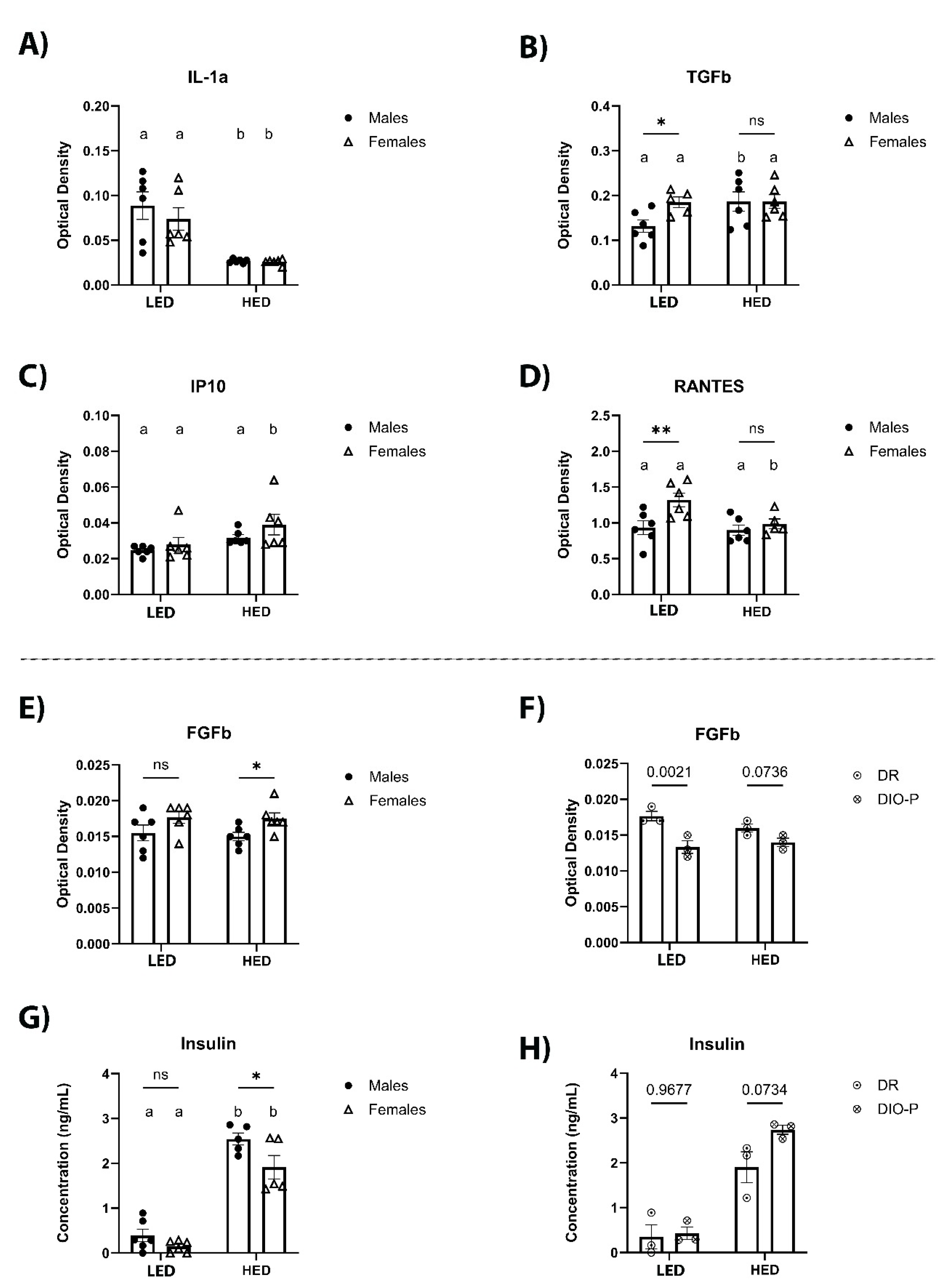

3.4. HED Consumption Affects Cytokine and Chemokine Levels in Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organization, W.H. , Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. 2000.

- Engin, A. , The Definition and Prevalence of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome, in Obesity and Lipotoxicity, A.B. Engin and A. Engin, Editors. 2017, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 1-17.

- Grundy, S.M. , et al., Diagnosis and Management of the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation, 2005. 112(17): p. 2735-2752.

- Santiago, C.M.O. , et al., Unripe banana flour (Musa cavendishii) promotes increased hypothalamic antioxidant activity, reduced caloric intake, and abdominal fat accumulation in rats on a high-fat diet. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 2022. 46(10): p. e14341.

- Shen, C.-L. , et al., Green tea polyphenols benefits body composition and improves bone quality in long-term high-fat diet–induced obese rats. Nutrition Research, 2012. 32(6): p. 448-457.

- Sen, T. , et al., Diet-driven microbiota dysbiosis is associated with vagal remodeling and obesity. Physiology & Behavior, 2017. 173: p. 305-317.

- Binayi, F. , et al., Long-term high-fat diet disrupts lipid metabolism and causes inflammation in adult male rats: possible intervention of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, 2023. 129(1): p. 204-212.

- Kim, J.S. , et al., Gut microbiota composition modulates inflammation and structure of the vagal afferent pathway. Physiology & Behavior, 2020. 225: p. 113082.

- Kim, J.S. , et al., The gut-brain axis mediates bacterial driven modulation of reward signaling. Molecular Metabolism, 2023. 75: p. 101764.

- Levin, B.E., J. Triscari, and A.C. Sullivan, Relationship between sympathetic activity and diet-induced obesity in two rat strains. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 1983. 245(3): p. R364-R371.

- Nazari, S. and S.M.S. Moosavi, Temporal patterns of alterations in obesity index, lipid profile, renal function and blood pressure during the development of hypertension in male, but not female, rats fed a moderately high-fat diet. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, 2022. 128(4): p. 897-909.

- Jang, I. , et al., Physiological Difference between Dietary Obesity-Susceptible and Obesity-Resistant Sprague Dawley Rats in Response to Moderate High Fat Diet. Experimental Animals, 2003. 52(2): p. 99-107.

- Dobrian, A.D. , et al., Development of Hypertension in a Rat Model of Diet-Induced Obesity. Hypertension, 2000. 35(4): p. 1009-1015.

- Lartigue, G.d. , et al., Diet-induced obesity leads to the development of leptin resistance in vagal afferent neurons. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2011. 301(1): p. E187-E195.

- Paulino, G. , et al., Increased expression of receptors for orexigenic factors in nodose ganglion of diet-induced obese rats. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2009. 296(4): p. E898-E903.

- DeGruttola, A.K. , et al., Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2016. 22(5): p. 1137-50.

- Stojanov, S. Berlec, and B. Štrukelj, The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease. Microorganisms, 2020. 8(11).

- Yang, Y. , et al., Gut Microbiota Perturbation in Early Life Could Influence Pediatric Blood Pressure Regulation in a Sex-Dependent Manner in Juvenile Rats. Nutrients, 2023. 15(12).

- Hildebrandt, M.A. , et al., High-Fat Diet Determines the Composition of the Murine Gut Microbiome Independently of Obesity. Gastroenterology, 2009. 137(5): p. 1716-1724.e2.

- Magne, F. , et al., The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients, 2020. 12(5).

- García-Cabrerizo, R. , et al., Microbiota-gut-brain axis as a regulator of reward processes. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2021. 157(5): p. 1495-1524.

- Hamamah, S. , et al., Role of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Regulating Dopaminergic Signaling. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(2).

- Nakamura, Y. , et al., Fructooligosaccharides suppress high-fat diet-induced fat accumulation in C57BL/6J mice. BioFactors, 2017. 43(2): p. 145-151.

- Sugimoto, K. , et al., Dietary Bamboo Charcoal Decreased Visceral Adipose Tissue Weight by Enhancing Fecal Lipid Excretions in Mice with High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Prev Nutr Food Sci, 2023. 28(3): p. 246-254.

- Oteng, A.B. , et al., Cyp2c-deficiency depletes muricholic acids and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity in male mice but promotes liver damage. Mol Metab, 2021. 53: p. 101326.

- Song, M. , et al., Safety evaluation and lipid-lowering effects of food-grade biopolymer complexes (ε-polylysine-pectin) in mice fed a high-fat diet. Food & Function, 2017. 8(5): p. 1822-1829.

- Gómez-Martínez, S. Marcos, and F.P. de Heredia, Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 2012. 71(2): p. 332-338.

- Hildebrandt, X. Ibrahim, and N. Peltzer, Cell death and inflammation during obesity: “Know my methods, WAT(son)”. Cell Death & Differentiation, 2023. 30(2): p. 279-292.

- Kershaw, E.E. and J.S. Flier, Adipose Tissue as an Endocrine Organ. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2004. 89(6): p. 2548-2556.

- Liu, L. , et al., Adipokines, adiposity, and atherosclerosis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2022. 79(5): p. 272.

- Zhang, J.M. and J. An, Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin, 2007. 45(2): p. 27-37.

- Pestel, J. , et al., Adipokines in obesity and metabolic-related-diseases. Biochimie, 2023. 212: p. 48-59.

- Bolyen, E. , et al., Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2 (vol 37, pg 852, 2019). Nature Biotechnology, 2019. 37(9): p. 1091-1091.

- Lu, Y. , et al., MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0: comprehensive statistical, functional and integrative analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Research, 2023. 51(W1): p. W310-W318.

- Tran, M. , et al., Improved Steatocrit Results Obtained by Acidification of Fecal Homogenates Are Due to Improved Fat Extraction. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 1996. 22(2): p. 157-160.

- Minaya, D.M. , et al., Consumption of a high energy density diet triggers microbiota dysbiosis, hepatic lipidosis, and microglia activation in the nucleus of the solitary tract in rats. Nutr Diabetes, 2020. 10(1): p. 20.

- Minaya, D.M. , et al., Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery triggers rapid DNA fragmentation in vagal afferent neurons in rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars), 2019. 79(4): p. 432-444.

- Braga Tibaes, J.R. , et al., Sex Differences Distinctly Impact High-Fat Diet-Induced Immune Dysfunction in Wistar Rats. The Journal of Nutrition, 2022. 152(5): p. 1347-1357.

- Minaya, D.M. L. Robertson, and N.E. Rowland, Circadian and economic factors affect food acquisition in rats restricted to discrete feeding opportunities. Physiology & Behavior, 2017. 181: p. 10-15.

- Taraschenko, O.D. M. Maisonneuve, and S.D. Glick, Sex differences in high fat-induced obesity in rats: Effects of 18-methoxycoronaridine. Physiology & Behavior, 2011. 103(3-4): p. 308-314.

- Huang, K.P. , et al., Sex differences in response to short-term high fat diet in mice. Physiology & Behavior, 2020. 221.

- Hwang, L.L. , et al., Sex Differences in High-fat Diet-induced Obesity, Metabolic Alterations and Learning, and Synaptic Plasticity Deficits in Mice. Obesity, 2010. 18(3): p. 463-469.

- Choi, D.K. , et al., Gender difference in proteome of brown adipose tissues between male and female rats exposed to a high fat diet. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2011. 28(5): p. 933-48.

- Levin, B.E. and A.A. Dunn-Meynell, Defense of body weight depends on dietary composition and palatability in rats with diet-induced obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2002. 282(1): p. R46-R54.

- Li, X., C. -Y. Yeh, and N.T. Bello, High-fat diet attenuates morphine withdrawal effects on sensory-evoked locus coeruleus norepinephrine neural activity in male obese rats. Nutritional Neuroscience, 2022. 25(11): p. 2369-2378.

- Ma, Y. Gao, and D. Liu, Alternating Diet as a Preventive and Therapeutic Intervention for High Fat Diet-induced Metabolic Disorder. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 26325.

- Ross, A.W. , et al., Photoperiod regulates lean mass accretion, but not adiposity, in growing F344 rats fed a high fat diet. PLoS One, 2015. 10(3): p. e0119763.

- Rojas, J.M. L. Printz, and K.D. Niswender, Insulin detemir attenuates food intake, body weight gain and fat mass gain in diet-induced obese Sprague–Dawley rats. Nutrition & Diabetes, 2011. 1(7): p. e10-e10.

- Estrany, M.E. , et al., High-fat diet feeding induces sex-dependent changes in inflammatory and insulin sensitivity profiles of rat adipose tissue. Cell Biochemistry and Function, 2013. 31(6): p. 504-510.

- Fourny, N. , et al., Male and Female Rats Have Different Physiological Response to High-Fat High-Sucrose Diet but Similar Myocardial Sensitivity to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Nutrients, 2021. 13(9).

- Levin, B.E. , et al., Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 1997. 273(2): p. R725-R730.

- de Lartigue, G. , et al., Diet-induced obesity leads to the development of leptin resistance in vagal afferent neurons. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011. 301(1): p. E187-95.

- Le Chatelier, E. , et al., Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature, 2013. 500(7464): p. 541-+.

- Ley, R.E. , et al., Microbial ecology - Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature, 2006. 444(7122): p. 1022-1023.

- Ley, R.E. , et al., Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005. 102(31): p. 11070-11075.

- Minaya, D.M. , et al., Consumption of a high energy density diet triggers microbiota dysbiosis, hepatic lipidosis, and microglia activation in the nucleus of the solitary tract in rats. Nutrition & Diabetes, 2020. 10(1).

- Tan, H.Z. X. Zhai, and W. Chen, Investigations of spp. towards next-generation probiotics. Food Research International, 2019. 116: p. 637-644.

- Wang, K. , et al., Alleviates Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunctions via Production of Succinate and Secondary Bile Acids. Cell Reports, 2019. 26(1): p. 222-+.

- Liu, S. P. Qin, and J. Wang, High-Fat Diet Alters the Intestinal Microbiota in Streptozotocin-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Microorganisms, 2019. 7(6).

- Desai, M.S. , et al., A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell, 2016. 167(5): p. 1339-+.

- Iwao, M. , et al., Supplementation of branched-chain amino acids decreases fat accumulation in the liver through intestinal microbiota-mediated production of acetic acid. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1).

- Dao, M.C. , et al., and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut, 2016. 65(3): p. 426-436.

- Jackson, C.D. , et al., Interactions of varying levels of dietary fat, carbohydrate, and fiber on food consumption and utilization, weight gain and fecal fat contents in female sprague-dawley rats. Nutrition Research, 1996. 16(10): p. 1735-1747.

- Shang, W. , et al., Characterization of fecal fat composition and gut derived fecal microbiota in high-fat diet fed rats following intervention with chito-oligosaccharide and resistant starch complexes. Food & Function, 2017. 8(12): p. 4374-4383.

- Jackman, M.R. , et al., Trafficking of dietary fat in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2006. 291(5): p. E1083-E1091.

- Ashley, C.D. L. Kramer, and P. Bishop, Estrogen and Substrate Metabolism. Sports Medicine, 2000. 29(4): p. 221-227.

- Escrich, R. , et al., A high-corn-oil diet strongly stimulates mammary carcinogenesis, while a high-extra-virgin-olive-oil diet has a weak effect, through changes in metabolism, immune system function and proliferation/apoptosis pathways. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2019. 64: p. 218-227.

- Almog, T. , et al., Interleukin-1α deficiency reduces adiposity, glucose intolerance and hepatic de-novo lipogenesis in diet-induced obese mice. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2019. 7(1): p. e000650.

- Kundu, A. , et al., Protective effect of EX-527 against high-fat diet-induced diabetic nephropathy in Zucker rats. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2020. 390: p. 114899.

- Pinhal, C.S. , et al., Time-course morphological and functional disorders of the kidney induced by long-term high-fat diet intake in female rats. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 2013. 28(10): p. 2464-2476.

- Yadav, H. , et al., Protection from obesity and diabetes by blockade of TGF-β/Smad3 signaling. Cell Metab, 2011. 14(1): p. 67-79.

- Tsurutani, Y. , et al., The roles of transforming growth factor-β and Smad3 signaling in adipocyte differentiation and obesity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2011. 407(1): p. 68-73.

- Semeraro, M.D. , et al., The effects of long-term moderate exercise and Western-type diet on oxidative/nitrosative stress, serum lipids and cytokines in female Sprague Dawley rats. European Journal of Nutrition, 2022. 61(1): p. 255-268.

- Aloui, F. , et al., Grape seed and skin extract reduces pancreas lipotoxicity, oxidative stress and inflammation in high fat diet fed rats. Biomed Pharmacother, 2016. 84: p. 2020-2028.

- Laurentius, T. , et al., Long-Chain Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Markers Coaccumulate in the Skeletal Muscle of Sarcopenic Old Rats. Disease Markers, 2019. 2019.

- Corvera, S. and O. Gealekman, Adipose tissue angiogenesis: Impact on obesity and type-2 diabetes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 2014. 1842(3): p. 463-472.

- Zhao, L. , et al., Lactobacillus plantarum S9 alleviates lipid profile, insulin resistance, and inflammation in high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome rats. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 15490.

- Dharavath, R.N. , et al., High fat-low protein diet induces metabolic alterations and cognitive dysfunction in female rats. Metabolic Brain Disease, 2019. 34(6): p. 1531-1546.

- Amengual-Cladera, E. , et al., Sex differences in the effect of high-fat diet feeding on rat white adipose tissue mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity. Metabolism, 2012. 61(8): p. 1108-1117.

- Cedernaes, J. , et al., Adipose tissue stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 index is increased and linoleic acid is decreased in obesity-prone rats fed a high-fat diet. Lipids Health Dis, 2013. 12: p. 2.

- Levin, B.E. and A.A. Dunn-Meynell, Differential effects of exercise on body weight gain and adiposity in obesity-prone and -resistant rats. International Journal of Obesity, 2006. 30(4): p. 722-727.

- Obradovic, M. , et al., Leptin and Obesity: Role and Clinical Implication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021. 12: p. 585887.

- Maurya, R. , et al., COVID-19 Severity in Obesity: Leptin and Inflammatory Cytokine Interplay in the Link Between High Morbidity and Mortality. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021. 12.

- Gómez-Crisóstomo, N.P. , et al., Differential effect of high-fat, high-sucrose and combined high-fat/high-sucrose diets consumption on fat accumulation, serum leptin and cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, 2020. 126(3): p. 258-263.

- Zengin, A. , et al., Low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets have sex-specific effects on bone health in rats. European Journal of Nutrition, 2016. 55(7): p. 2307-2320.

- El-Haschimi, K. , et al., Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest, 2000. 105(12): p. 1827-32.

- Buettner, C. , et al., Critical role of STAT3 in leptin’s metabolic actions. Cell Metab, 2006. 4(1): p. 49-60.

| Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | Category | LED | HED | LED | HED |

| IL-6 | Pro- and anti- inflammatory | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 0.027 ± 0.003 | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 0.020 ± 0.002 |

| IL-5 | Proinflammatory | 0.059 ± 0.007 | 0.047 ± 0.003 | 0.053 ± 0.003 | 0.058 ± 0.005 |

| IL-15 | Proinflammatory | 0.051 ± 0.006 | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.047 ± 0.003 | 0.046 ± 0.002 |

| IL-1β | Proinflammatory | 0.070 ± 0.007 | 0.056 ± 0.002 | 0.065 ± 0.003 | 0.062 ± 0.004 |

| Leptin | Proinflammatory | 0.050 ± 0.006 | 0.041 ± 0.002 | 0.046 ± 0.003 | 0.043 ± 0.003 |

| VEGF | Proinflammatory | 0.029 ± 0.003 | 0.027 ± 0.001 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.028 ± 0.003 |

| TNF-α | Proinflammatory | 0.057 ± 0.007 | 0.044 ± 0.004 | 0.053 ± 0.003 | 0.050 ± 0.005 |

| MCP-1 | Proinflammatory | 0.027 ± 0.003 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.028 ± 0.003 | 0.023 ± 0.001 |

| IFN-γ | Proinflammatory | 0.056 ± 0.008 | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 0.047 ± 0.003 |

| MIP-1α | Proinflammatory | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 0.020 ± 0.001 |

| SCF | Stem cell factor | 0.074 ± 0.010 | 0.076 ± 0.016 | 0.067 ± 0.004 | 0.058 ± 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).