1. Introduction

The growing development and penetration of communication technologies and biometric applications in society helped general citizens in their daily jobs, tasks, and time off. At the same line, also criminals make use of these tools for their illicit activities. Technological developments helped perpetrators in carrying out activities of organized crime, financial crime, drug trafficking, kidnapping, child exploitation, terrorism, and so on [

1].

Speaker recognition denotes the ability of discriminating one person from another based on speech via voice recordings. Forensic speaker recognition is speaker recognition adapted to the technical limitations and behavioral influences of real-world forensic conditions and the specific needs of reporting to and interacting with the justice system, namely with courts, prosecutors, and criminal investigators [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The role of the forensic expert is to compare one or several recordings of a questioned speaker with one or several recordings of a suspect, helping the court, prosecution, or law enforcement agencies (LEA) to decide whether the suspect said or not the questioned speech. Three approaches can be distinguished: auditory-phonetic based on the auditory examination of recordings by trained phoneticians or linguists; acoustic-phonetic methods involving the measurement of various acoustic parameters such as fundamental frequency and its variation, formant frequencies, and speech tempo; and automatic and semiautomatic speaker recognition in which the central processing stages (feature extraction, feature modeling, similarity scoring, and likelihood ratio computation) operate fully or partially automatically. [

2,

3,

4,

6,

7].

According to an INTERPOL survey on the use of speaker recognition by LEAs [

8], in 2016, of the 44 LEAs that had the capability to analyze voice recordings, 26 reported the use of Forensic Automatic Speaker Recognition (FASR) systems, representing a high rate of implementation. Gold & French conducted two international surveys to access forensic speaker comparison practices, noting an increase from 17% (2011) to 41.2% (2019) in the use of FASR systems [

9,

10]. Given these observations, it is reasonable to assume that nowadays it will be even higher.

FASR systems have evolved rapidly over the last decade, becoming increasingly capable of performing speaker recognition tasks with lower error rates and better discrimination power. An important feature of voice biometrics systems is their ability to perform identification operations on large amounts of data (speech samples) at high speed. This allows the performance metrics of the applied voice biometrics technology to be analyzed using different types of audios (corpora).

A standard FASR system can be divided into three main sections: feature extraction, which consists in converting the digital speech signal to sets of feature vectors that contain the essential characteristics of the speaker’s voice; modeling, in which speaker models are generated using the features previously extracted; and similarity scoring and likelihood ratio (LR) computation as a result of the comparison of the previously generated models with the unknow sample model for recognition [

2,

3,

6,

11].

A pre-processing stage, where the speech signal is separated from periods of silence, transient noises, and speech of other speakers, is mandatory to ensure that minimum technical requirements are satisfied.

The performance of the system is commonly evaluated using graphic representation, the Tippett plots, and also calculating quantifiable metrics such as equal error rate (EER) and log-likelihood ratio cost (Cllr) [

2,

3,

6,

12,

13].

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a new challenge for forensic speaker recognition given the mandatory use of protection masks in almost every daily situation, as these act as voice barriers or filters. Although it was declared finished, forensic examinations from the COVID-19 period are still arriving at forensic institutes. Also, studying the effect of protection masks contributes to better knowledge of the impact of disguised voice cover techniques in forensic systems.

The work package 7 (WP7) of the “Competency, Education, Research, Testing, Accreditation, and Innovation in Forensic Science” (CERTAIN-FORS) project, funded by the European Union (EU) and coordinated by the European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ENFSI), intended the development of the Forensic Multilingual Voices Database (FMVD) to be shared with the ENFSI Forensic Speech and Audio Analysis Working Group (FSAAWG) members, tackling three main issues:

Contribute to the improvement of proficiency tests and collaborative exercises within the FSAAWG.

Address the lack of suitable reference populations given the variability of languages spoken in Europe.

Evaluate the impact of face masks widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic on forensic speaker recognition.

The present study focuses on the impact of facial masks on FASR systems making use of the Forensic Multilingual Voices Database (FMVD).

2. Related Work

Acoustic research on speech with face masks has obtained attention from the field of phonetics and automatic systems for speaker recognition.

Focusing on the automatic speaker recognition (ASR) approach, Khan

et al. [

14] examine ASR systems performance in the presence of three different types of COVID protection masks: surgical, cloth, and N95. Authors collected samples from 20 persons speaking without a mask, wearing a surgical mask, a cloth mask, and an N95-type mask, indoors and outdoors, using several microphones and smartphones, at three different distances between mouth and recorder: close to mouth, 45 cm, and 90 cm. ASR systems performance was evaluated, and the results were the following:

when confronted with the presence of face masks, the five comparative Machine Learning based, and an additional ensemble-based, ASR classifiers severely misclassified speech samples recorded using cloth masks;

the ASR system's performance is degraded when the distance between mouth and detector increases, either with or without face masks;

the type of microphone can adversely affect the ASR system performance, and when subjects with different types of masks were tested, the equal error rate increased even more.

Al-Karawi [

15] studied face masks effect on ASR system performance in the presence of noise. Voice samples were collected from thirty participants without a mask and wearing a surgical and a cloth mask. Recordings were made in controlled conditions. Cafeteria noise was also collected, ensuring that human voices were not present. Then, the noise was mixed with the original recording for testing. The system's performance diminishes when used with mismatched masks. Results also show that the mask effect on the ASR system is more evident with the increasing noise level.

Concerning FASR, limited research has been done to evaluate the impact of face masks. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Saeidi

et al. [

16] analyzed the effect of four different face coverings: helmet, rubber mask, surgical mask, and hood/scarf, on FASR. The system experienced a small performance degradation, indicating its capability in partially mitigating the face mask mismatch. However, these results were obtained with a dataset of voice samples from only 8 individuals. Later on, Saeidi

et al. [

17] investigated the passive effect of the masks in the speaker’s voice and applied a compensation function, improving the results for the helmet and rubber mask.

Iszatt

et al. [

18] explored the impact of face coverings on speaker recognition using VOCALISE, a commercial FASR software from Oxford Waves Research. Two independent datasets were used, one built with speech samples recorded by 8 participants on their phones, indoors and outdoors, wearing a fabric mask, a surgical mask, and without a face cover. The second data set was a gender-balanced 10-speaker corpus in which samples were collected under a range of face covering conditions: Audio-Visual Face Cover Corpus [

19]. Results suggest that everyday face coverings do not negatively affect speaker recognition performance, and they were consistent for both datasets. The authors also concluded that further research is needed with a larger corpora and more forensically realistic data.

Bogdanel

et al. [

20] explored the impact of the use of different masks on the performance of a forensic automatic speaker recognition system. Voice samples were collected from 30 Spanish speakers reading a text without a mask, wearing a surgical mask, and wearing an FFP2 mask. Results show that face masks affect the performance of the system, and its effect varies with the mask type; in particular, the classification accuracy was higher for FFP2 type masks. This result is probably due to the increase in speech intensity that was found with this type of mask, which is in accordance with Ribeiro

et al. [

21], who concluded that individuals when speaking with face covers have the sensation of less audibility and tend to try to compensate for this effect by increasing speech intensity. The authors also trained the models with speech samples obtained with either two types of masks; in this case, the recognition system improved its accuracy, achieving similar results to the ones obtained when training and testing were performed in the absence of protection masks, which is consistent with the results in publish by Khan

et al. [

14].

To evaluate the effects of a face mask on speech production between Mandarin Chinese and English and its implications for forensic speaker identification, Geng

et al. [

22] performed a cross-linguistic study. Voice samples were collected from thirty volunteers, Mandarin native speakers and fluent in English as a second language. Each participant gave two text-reading samples in Mandarin without a mask, one in Mandarin wearing a surgical mask, one in English without a mask, and one in English wearing a surgical mask. The results show that high variable accuracies were observed in speakers’ identification. The authors concluded that speakers tend to conduct acoustic adjustments to improve their speech intelligibility when wearing surgical masks. However, a cross-linguistic difference indicates that strategies to compensate for intelligibility were not the same for both languages. General performance and accuracy of ASR systems are affected by surgical masks.

3. Materials and Methods

The FMVD was developed with the collaboration of several members of the ENFSI FSAAWG, representing ten countries: Lithuania (LT), Croatia (HR), Romania (RO), Spain (ES), Türkiye (TR), Ukraine (UA), Portugal (PT), Georgia (KA), Hungary (HU), and Armenia (AM). All samples were collected from volunteers who signed an informed consent statement designed for the development and distribution of the FMVD among ENFSI FSAAWG members.

It was asked to the collaborating Institutes to collect voice samples from a minimum of 40 males and 40 females, 10 of each in the following age classes, in years: [18, 30], [31, 40], [41, 50], [51, +∞). Voice sampling was divided into two categories:

Text reading samples where each person was recorded reading a selected text without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing an FFP2 mask (FP) in their native language. Each volunteer was also asked to read the same text, without a mask, in a non-native language(s) that he/she speaks.

Dialogue speech samples collected from the same individuals in their native language and also speaking in non-native language(s), always without face masks. If the individual does not speak proficiently a non-native language(s) this sample(s) could be ignored.

The project provided the masks and the text to be read. All recordings were made in WAV format, mono signal, resolution of 16 bits, indoors.

Table 1 presents the recording device models and the respective sampling rates used by each collaborating institute. To normalize the automatic speaker recognition procedures, audios collected in Georgian and Portuguese were converted to a sampling frequency of 8 kHz.

Not all collaborating institutes managed to collect the minimum number of samples requested. Conversely, other institutes collected significantly more samples. In these cases, only part of the recordings made were used in order to approximate the number of samples available in all the languages studied.

A total of 2552 samples obtained from 638 volunteers spread over eight languages were used.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the subjects by language, sex, and age.

Although it was not possible to guarantee normalized recording conditions between the participating institutes, it is important to note that the collection conditions were uniform per language, i.e., each laboratory controlled the conditions of the voice collections it carried out.

Recordings were pre-processed using a Matlab tool developed for removing silences from voice samples according to a background noise threshold. The same threshold was applied to all the samples from each subset of data per language, resulting in approximately 85 hours of recordings for the study.

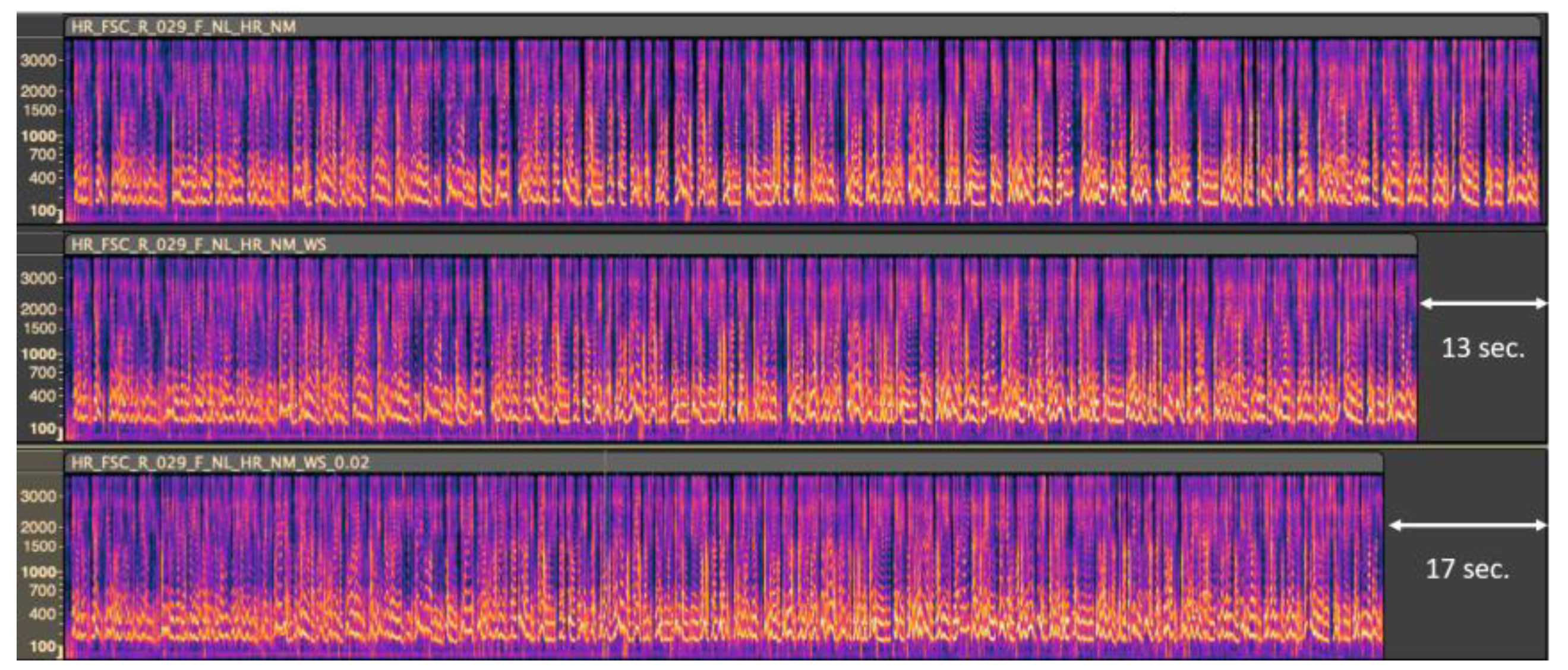

Figure 1 presents an example of the silence removal pre-processing process.

The commercial FASR system VOCALISE (Voice Comparison and Analysis of the Likelihood of Speech Evidence) [

23], from Oxford Waves Research (OWR), was chosen to perform the comparisons, using the software's x-vector technology.

In each case, the first input for the comparisons was a spontaneous speech sample recorded by speakers without a face mask. The second input was a reading sample in the same language, recorded without the use of a mask. Once the scores and LRs results of the VOCALISE had been obtained, the values of the respective EER and Cllr performance metrics were calculated with the Bio-Metrics (OWR) performance metrics software.

The same procedure was carried out to compare the dialog samples with speech samples taken when the subjects were wearing a surgical mask and when the speakers were wearing an FFP2 face mask.

The differences in the EER and Cllr values calculated from the results of the comparisons made with VOCALISE were investigated for each type of speech collection, namely reading without a mask, reading with a surgical mask, and reading with an FFP2 mask. An evaluation of how the direction and magnitude of the observed trends depend on the language in which the speech samples were recorded was also performed.

4. Results

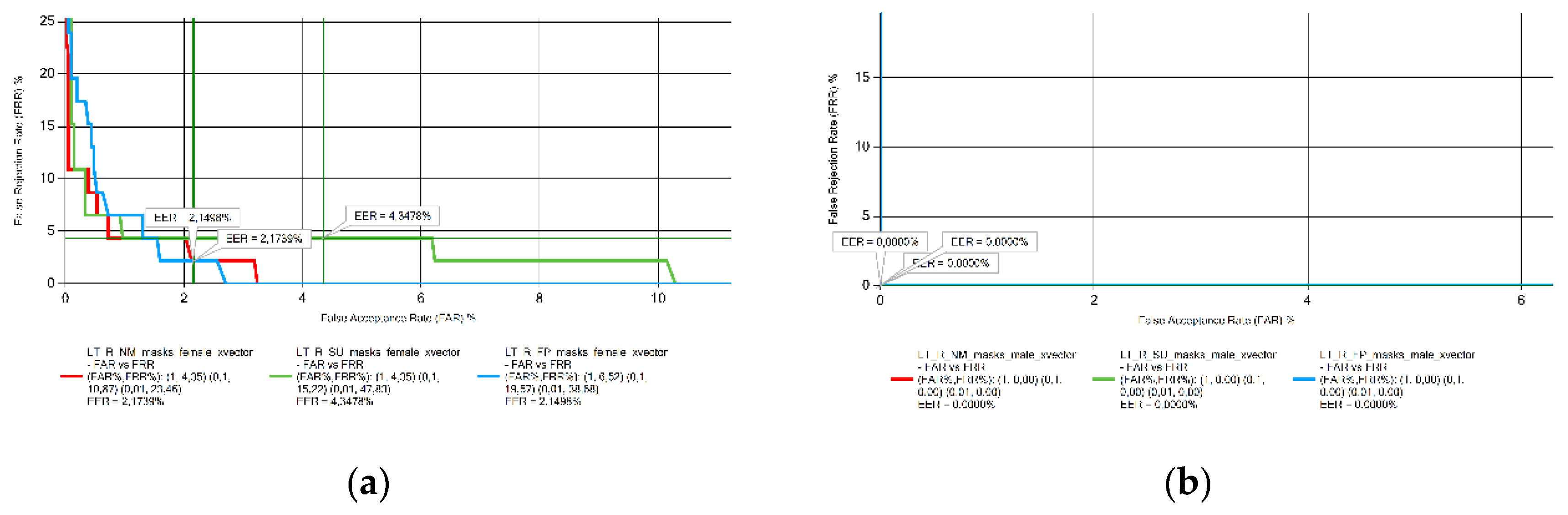

The results were evaluated using the Detection Error Trade-off (DET) curves of the Bio-Metrics performance metrics software. The DET curve plots the false rejection rate (FRR) and false acceptance rate (FAR) and estimates the EER.

The FRR shows the proportion of misclassifies identical speakers by the automatic recognition system based on a given threshold. The FAR represents the proportion of different speakers that the system misidentifies as the same speaker based on a given threshold level. Since the FAR and FRR depend on the value of the specified threshold level and vary at the expense of each other, the full picture is given by the EER, which is the point at which the FAR and FRR are equal.

The identification results were also evaluated by analyzing the Cllr values obtained from the raw scores. Cllr [

24,

25] is a calibration measure that refers to the reliability with which comparison scores can be used by experts to make decisions. For example, a well-calibrated system will generally output positive scores for comparisons with the same speaker and negative scores for comparisons with different speakers. To carry out calibration, a reference population is required, i.e., a separate data set with the same properties, such as sex, language and channel, as the audio material to be compared. In its absence, the cross-validation procedure of the Bio-Metrics software can be used. Since a separate calibration dataset was not available in this study, cross-validation was used.

The cross-validation procedure uses the leave one out method based on logistic regression to, by removing an individual from the dataset, calculate the weighting and deviation of that individual using all the other scores. This method was repeated with all raw scores until all data had been calibrated.

This calibration method doesn’t affect the discrimination power, so the EER doesn’t change; it only improves the calibration performance. The Cllr of a well calibrated system is less than 1 and, in an ideal situation, close to 0.

4.1. EER Results by Language and Sex

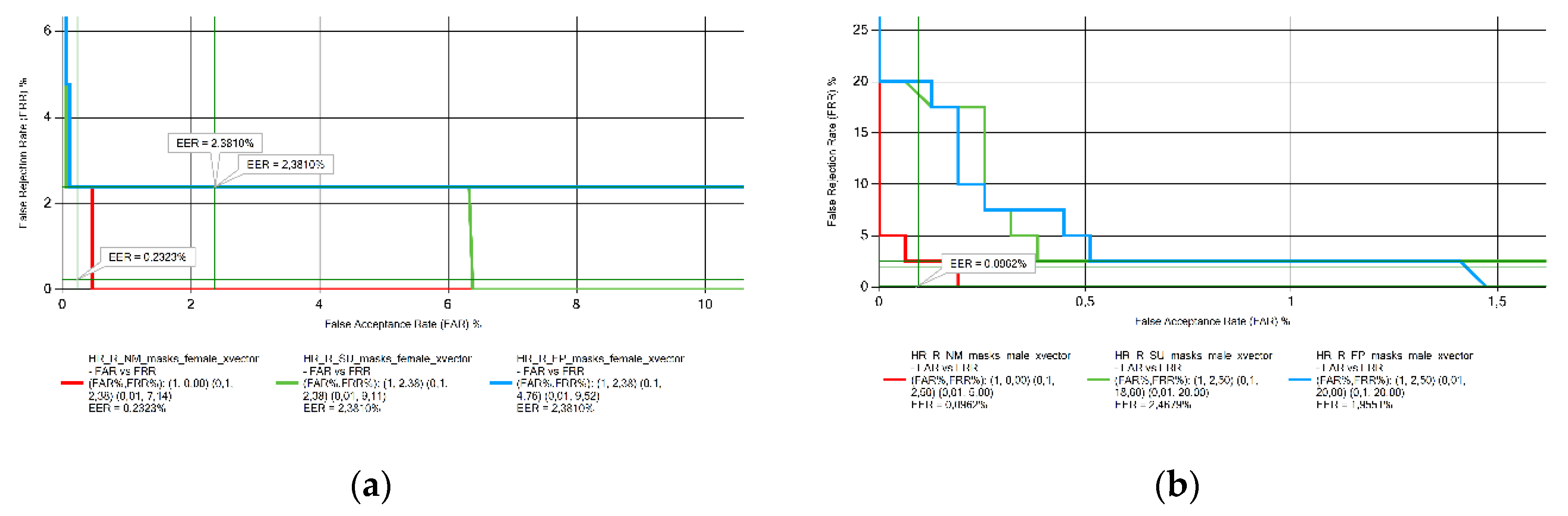

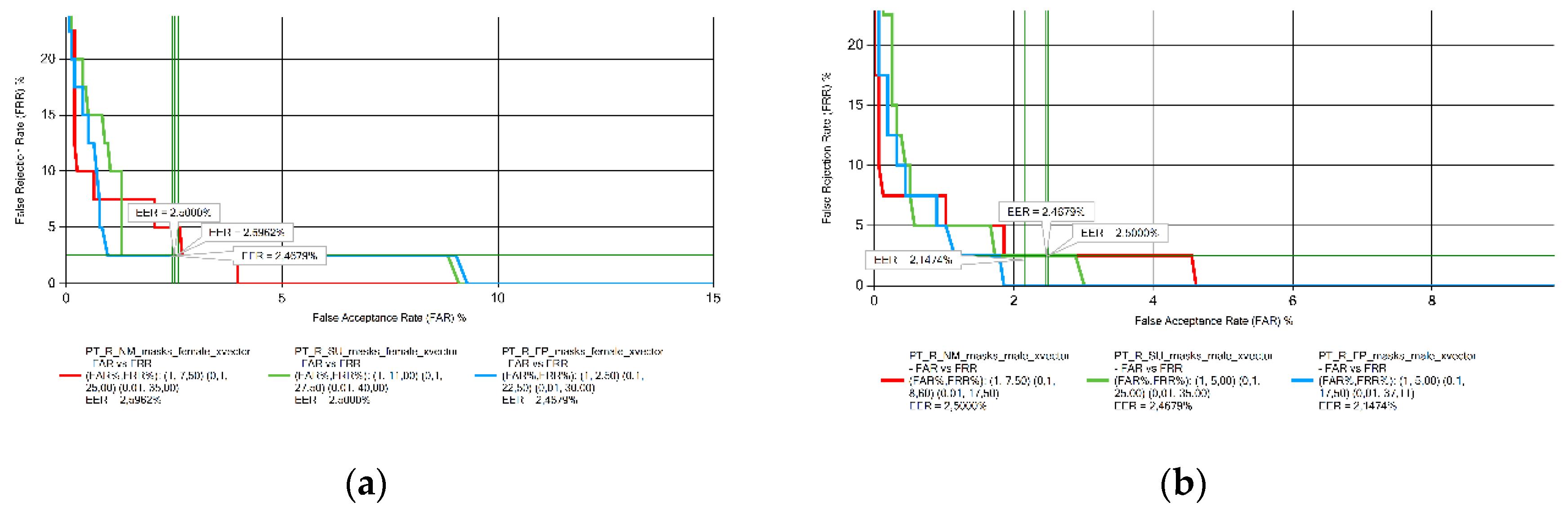

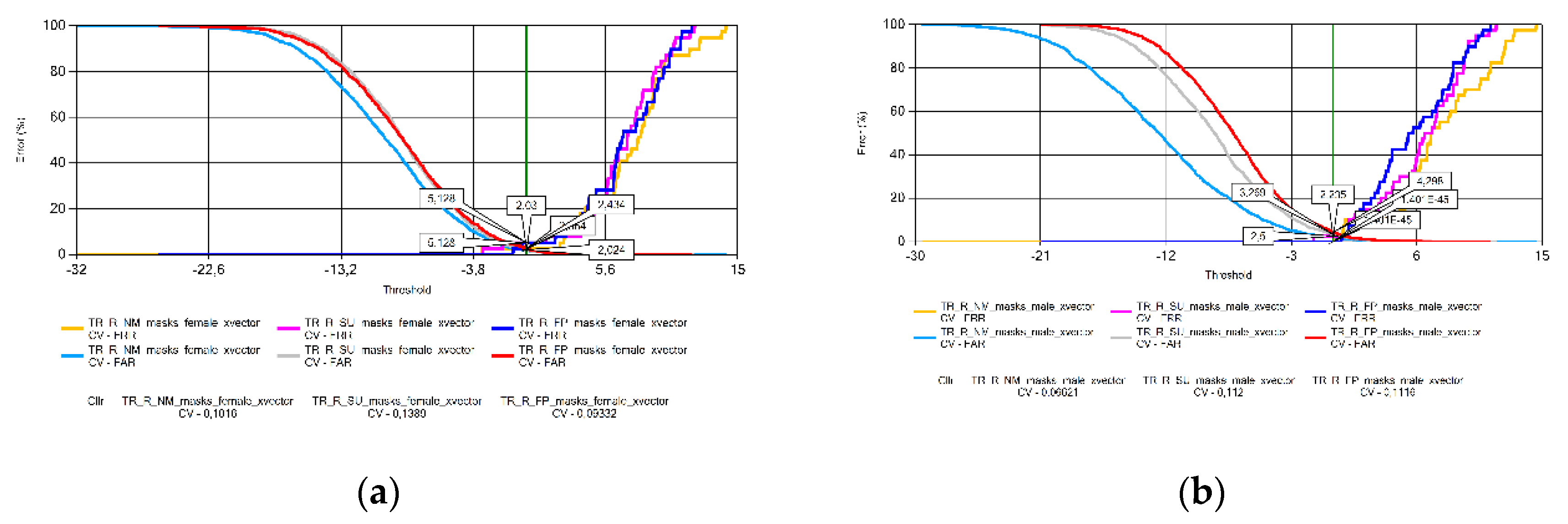

This subsection analyzes the variation in EER values for each language, comparing voice samples recorded without a mask, with a surgical mask, and with an FFP2 mask. For Croatian (

Figure 2), the samples recorded without masks have the lowest EER for both sexes, with no significant differences between the two types of masks.

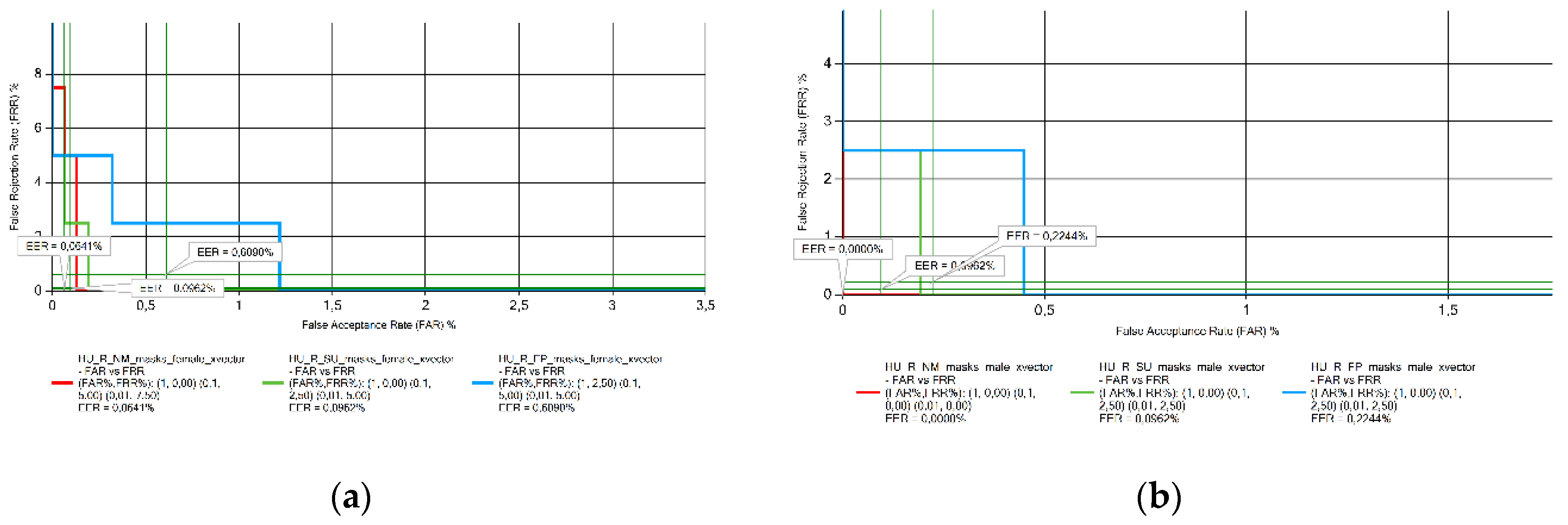

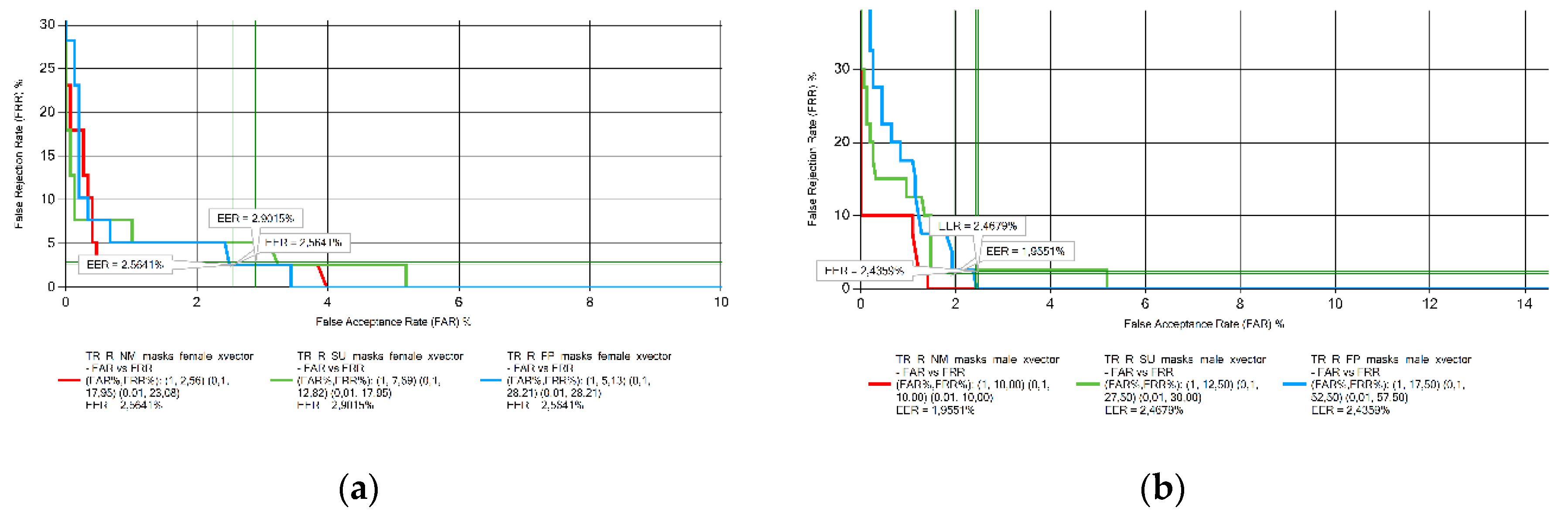

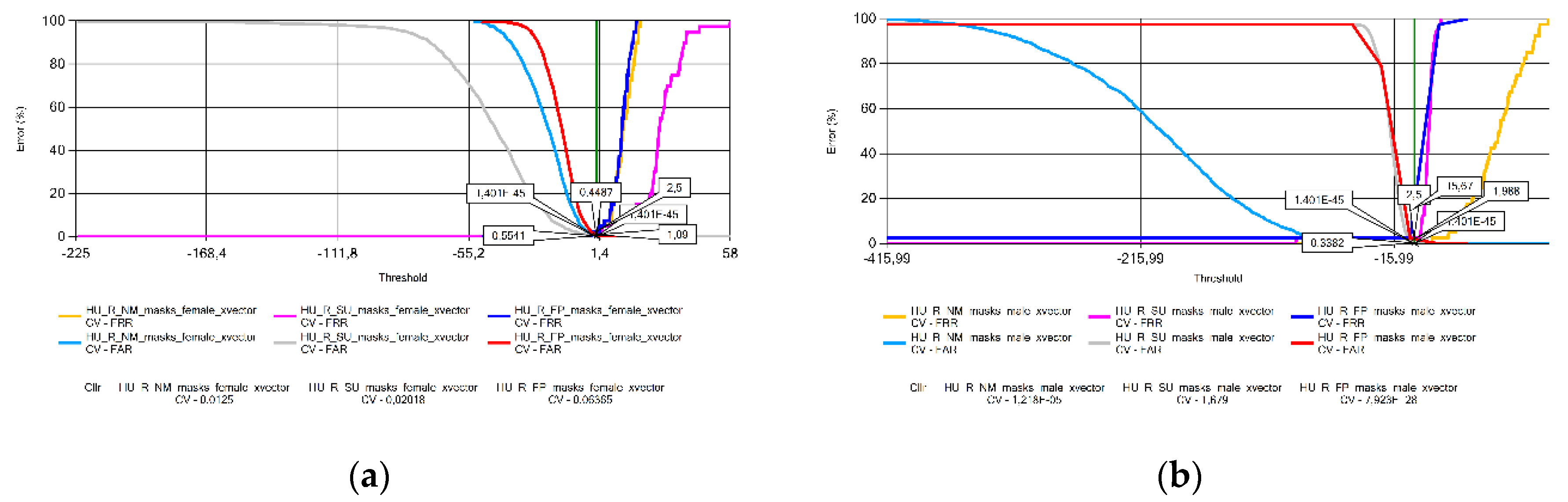

A trend is observed for the Hungarian language voice samples (

Figure 3): the lowest error rate is seen for recordings without a mask, increasing for collections wearing a surgical mask, and the higher value is observed in the presence of an FFP2 mask for both sexes.

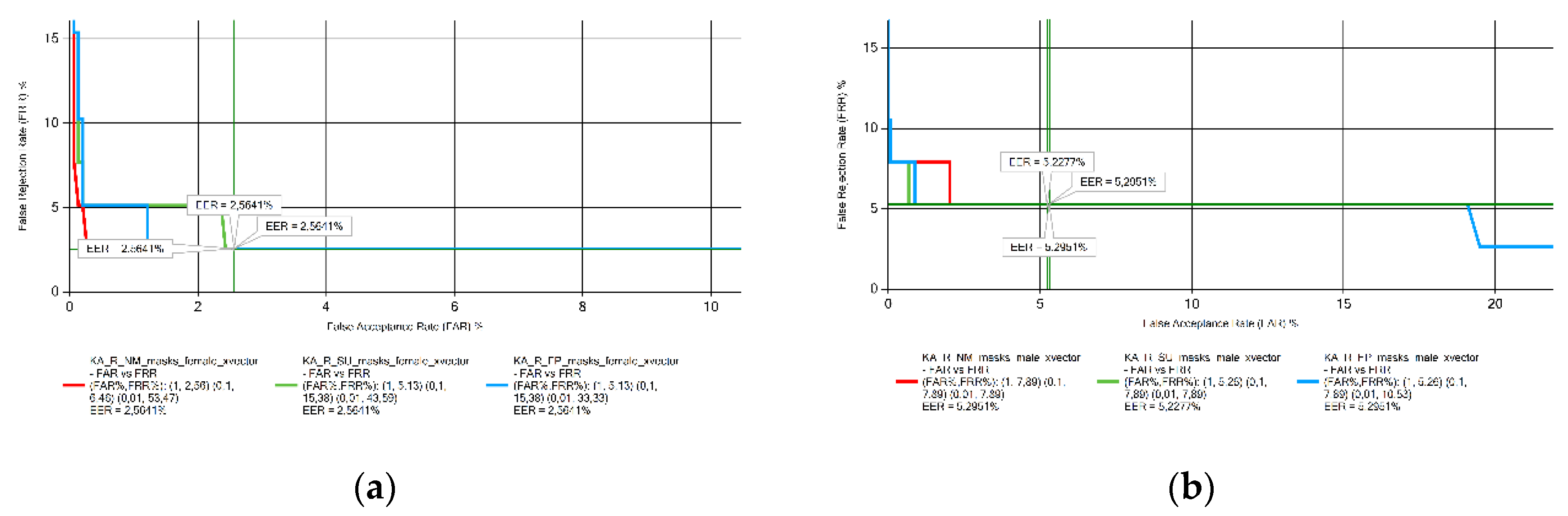

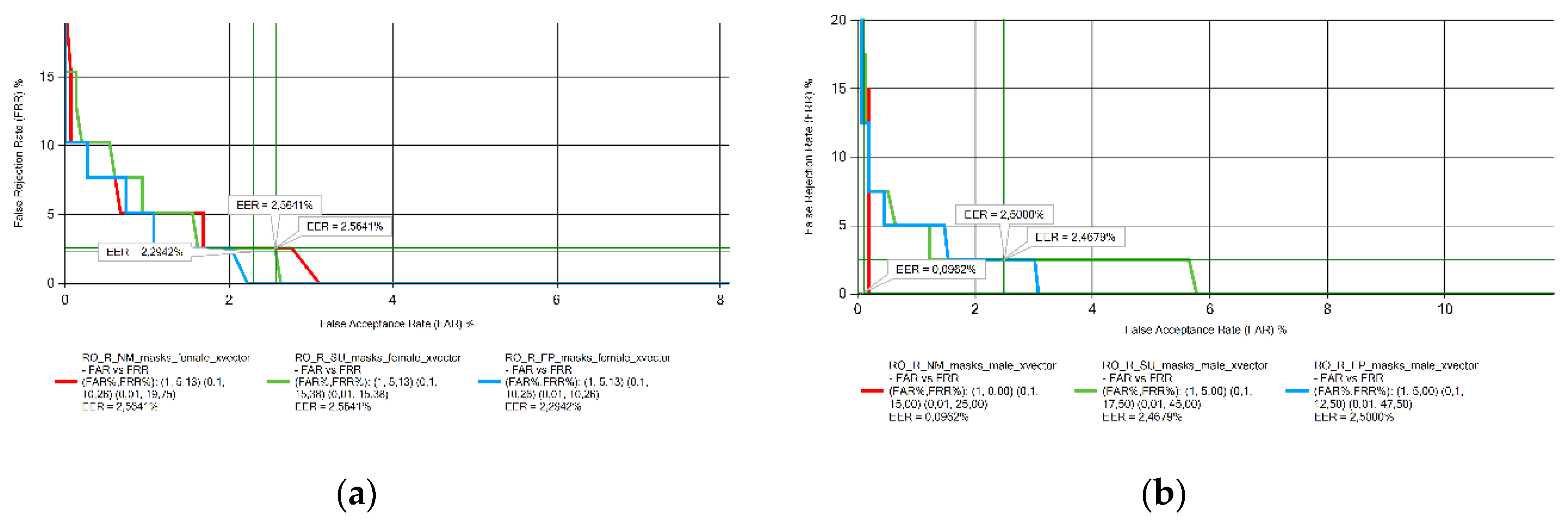

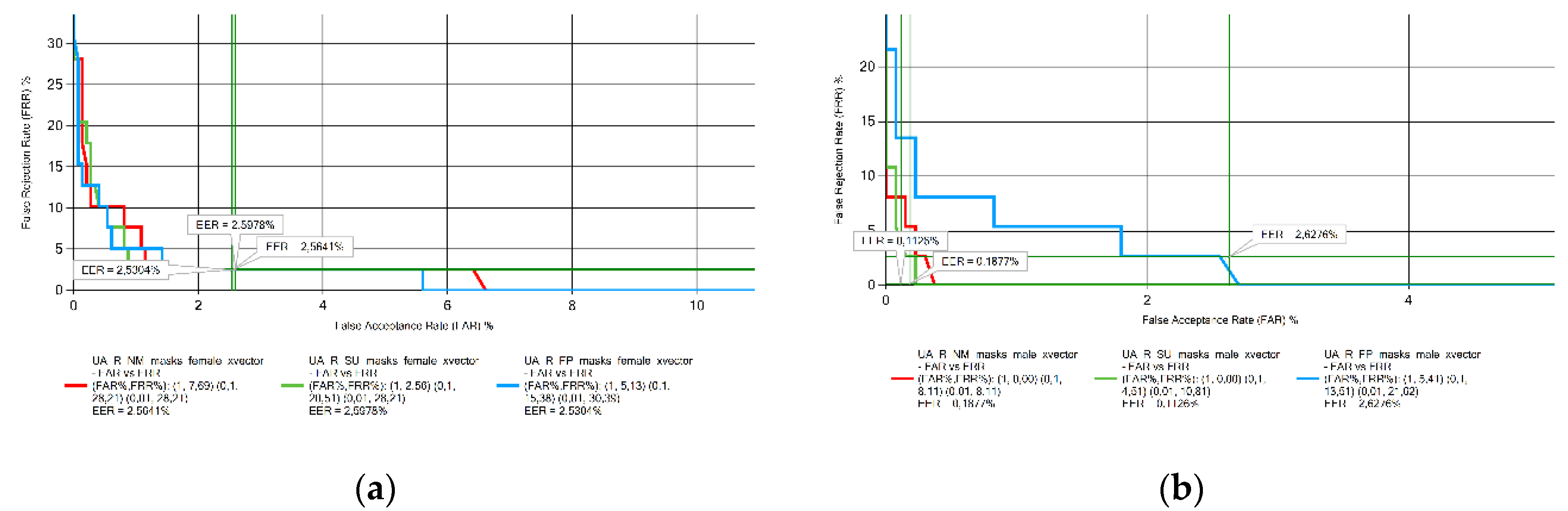

The EER results for the speech samples in Georgian (

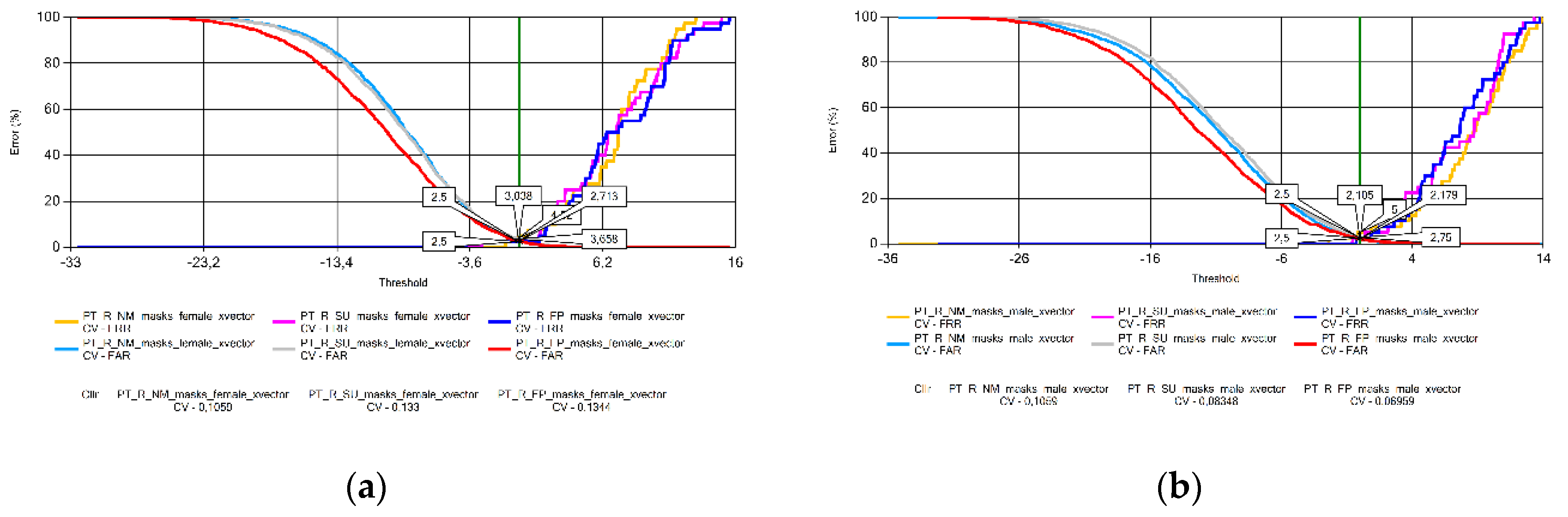

Figure 4), Portuguese (

Figure 5), and Turkish (

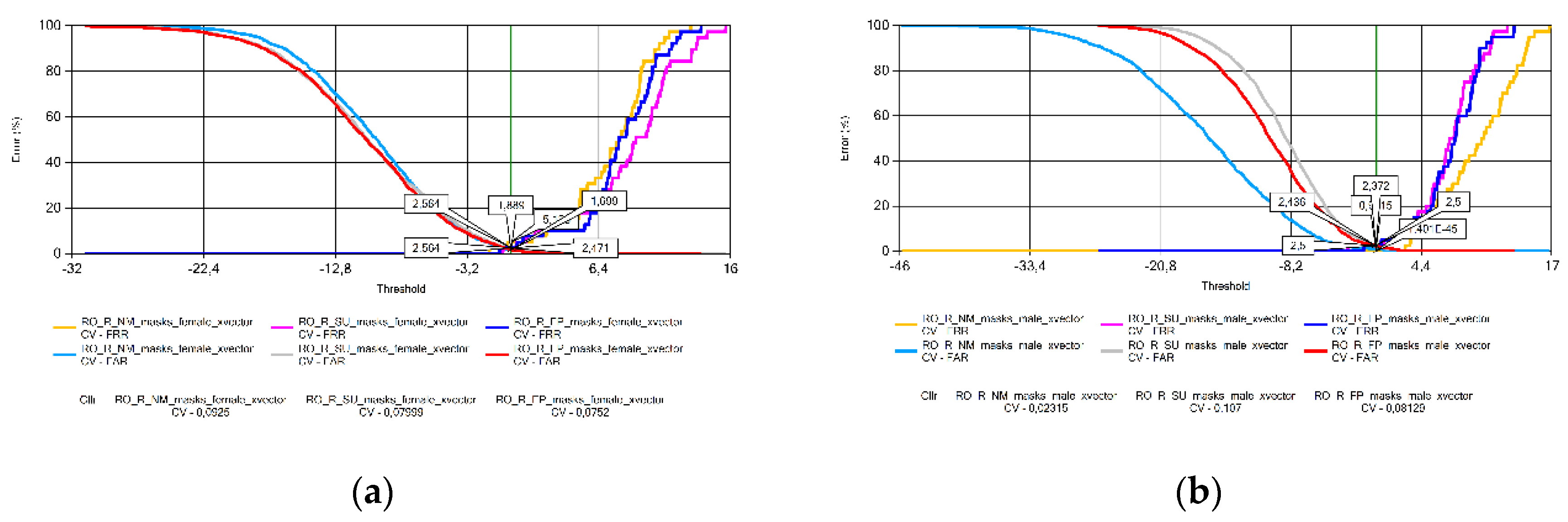

Figure 6) in both genders, and women speaking in Romanian (

Figure 7) did not change significantly with the presence of face masks. On the other hand, the results obtained for Romanian male speakers show an increase in the EER value for both masks.

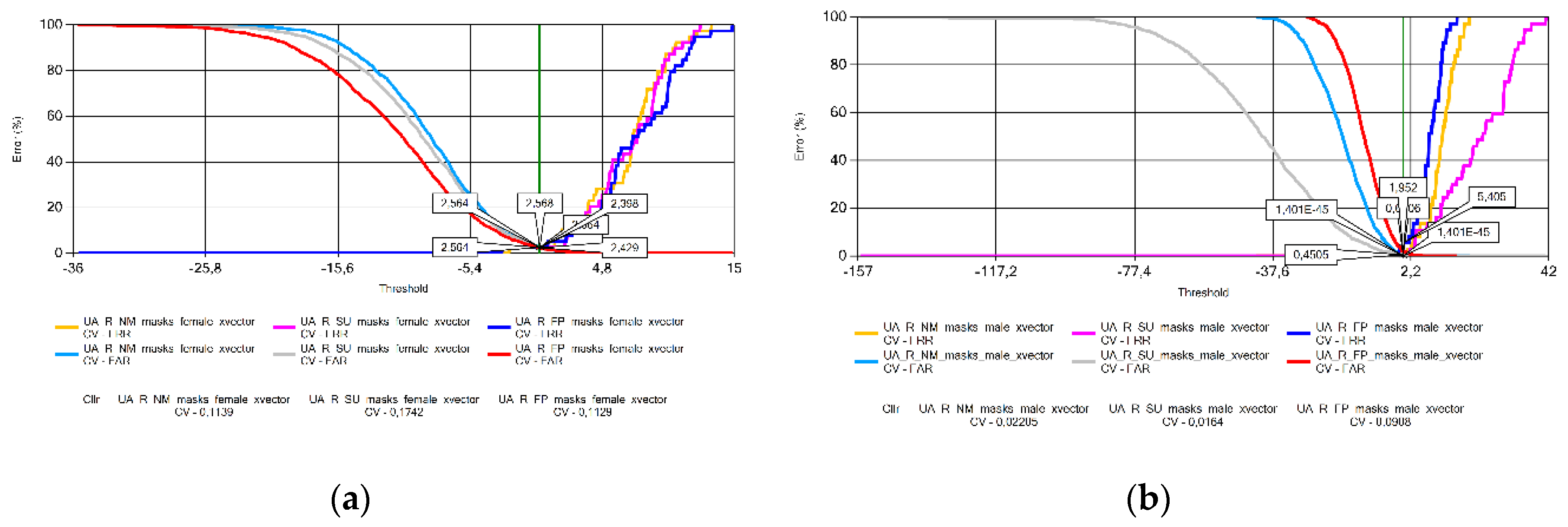

For the Ukrainian (

Figure 8) and Lithuanian (

Figure 9) voice samples, there is no clear trend on the behavior of EER in the presence of face masks. There was no significant variation in the EER value for Ukrainian female and Lithuanian male speakers. EER increased with the presence of the FFP2 mask in male Ukrainian speakers and in female Lithuanian speakers when the surgical mask was used.

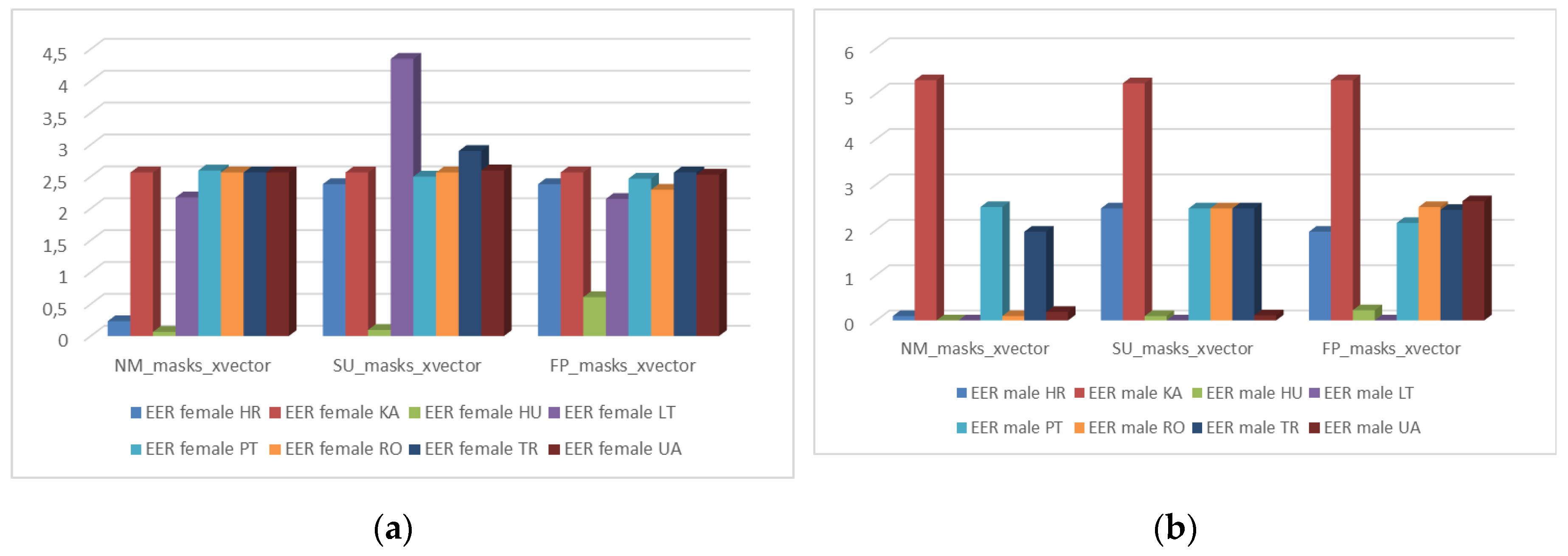

4.2. EER Results between Languages

Generally, the EER values observed for female speakers (

Figure 10a) are between 2-2.5% independently of the presence of a face mask, except for Croatian female speakers recorded without a mask and Hungarian female voice recordings, whose EER value is extremely low when compared to other languages. The result observed for Lithuanian females wearing a surgical mask can be considered an outlier.

For the voice samples recorded by male speakers (

Figure 10b), the results show that EER for Georgian speakers is significantly higher than for all other languages. The EER values obtained from Lithuanian and Hungarian male speakers independently of the mask type, Croatian without mask and Ukrainian with no mask and wearing a surgical mask were very low.

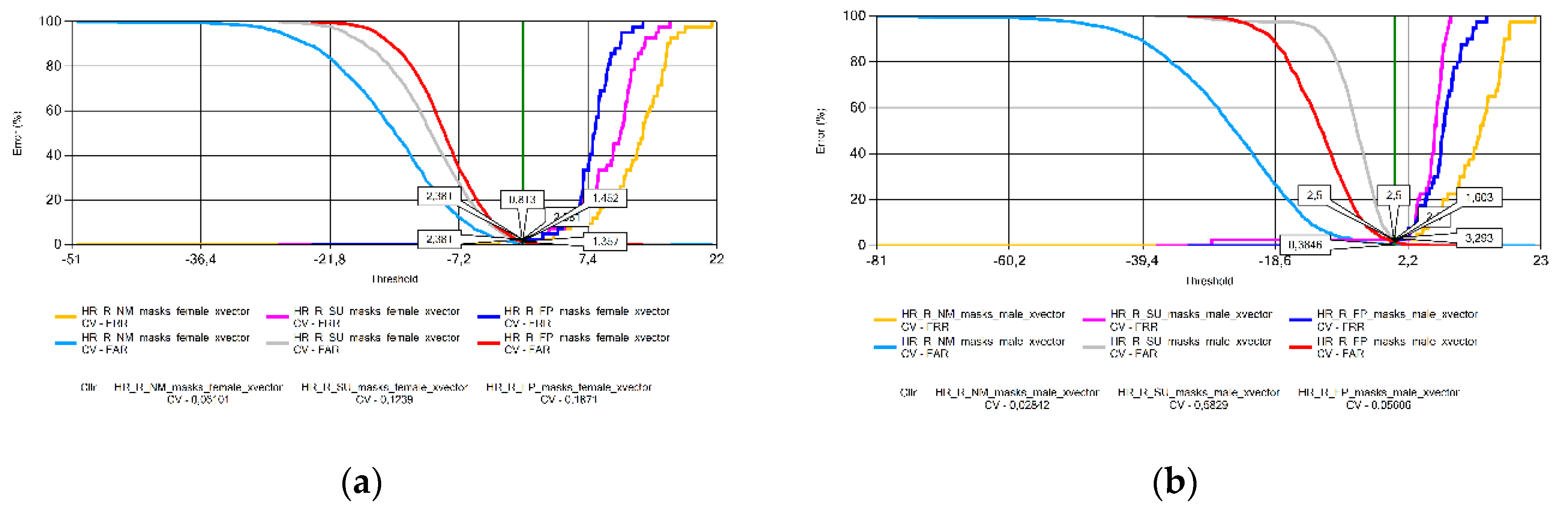

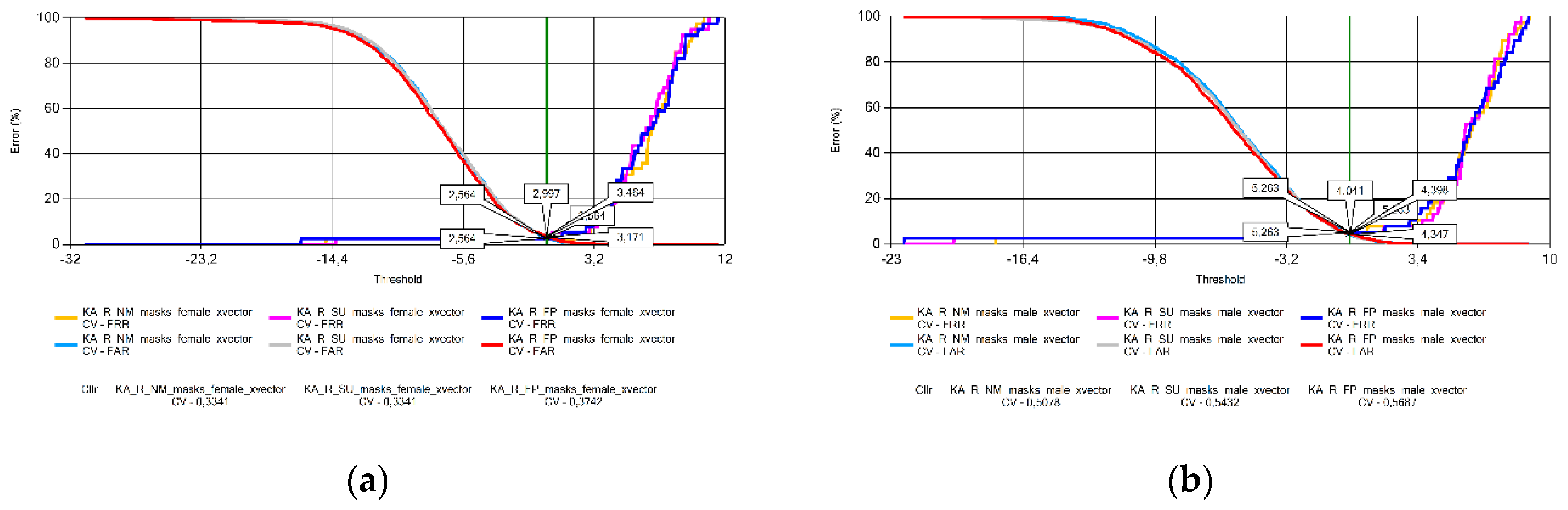

4.3. Cllr Results by Language and Sex

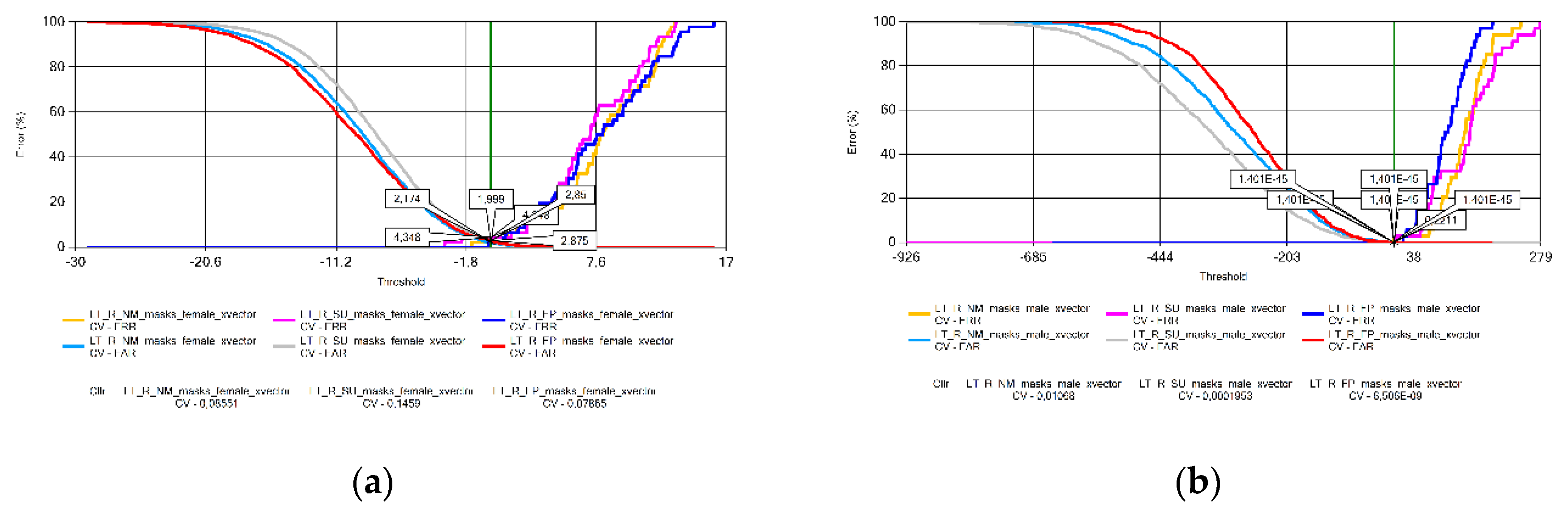

In this subsection, the Cross-Validated Cllr (CV in the figures) results with Equal Error Graphs (EER) are illustrated (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18) and analyzed. A visible problem is that in some cases the CV data are extremely high (Hungarian voice samples,

Figure 13) or small (Lithuanian voice samples,

Figure 14). This problem arises from the logistic regression for EER data close to zero. Without cross-validation, however, the Cllr values calculated from the raw score data would not have shown an objective comparison of system performance across languages and masking conditions.

The analysis of the Cllr (CV) data found an increasing trend in the voice patterns of Croatian (

Figure 11), Hungarian (

Figure 13), and Portuguese female speakers (

Figure 15a). This means that recordings made without wearing a mask have the best calibration value, deteriorating for samples recorded with a surgical mask, and the worst for audios recorded with a FFP2 mask. Samples recorded for male speakers show a ripple effect for most other languages with an overflow effect for Hungarian and Lithuanian samples due to the specificity of logistic regression.

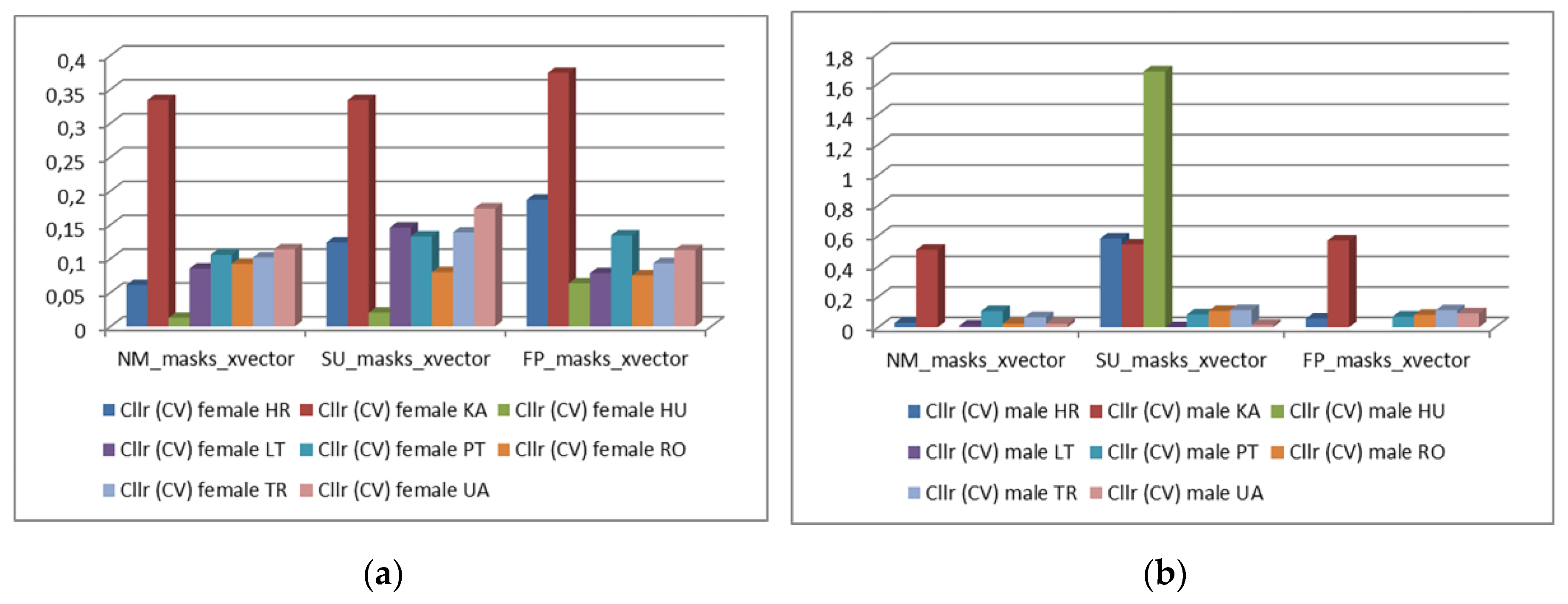

4.4. Cllr (CV) Results between Languages

As illustrated in

Figure 19, no clear trend in the variation of Cllr (CV) results between languages is observed.

There are strong fluctuations in the values obtained for female speakers. For male speakers, Cllr (CV) values in Croatian and Lithuanian when wearing surgical masks are severely high, resulting in potential outliers. Results obtained for Georgian speakers of both sexes showed significantly higher Cllr (CV) values compared to the other languages, both without a mask and in the presence of either of the two types of masks studied.

5. Discussion/Conclusions

Previous studies have reached different conclusions about the effect of protective face masks on the performance of FASR systems. The results presented by Iszatt

et al. [

18] suggest that face masks do not negatively affect speaker recognition performance. Bogdanel

et al. [

20] findings showed that not only do face masks affect the system performance, but this impact depends on the type of mask. The results of Geng

et al. [

22] revealed high variability in the accuracy of the speaker recognition system's performance. Both Bogdanel

et al. [

20] and Geng

et al. [

22] also concluded that speakers tend to make acoustic adjustments to compensate for their speech intelligibility, since the presence of facial masks gives the sensation of less audibility, which is in line with the results of Ribeiro

et al. [

21]. The results of Geng

et al. [

22] add that strategies to compensate for intelligibility can vary depending on the language spoken.

The present study shows that the use of protective masks by speakers has an impact on the performance metrics values obtained from measurements made with the VOCALISE speaker recognition software. The observed effect varies with the spoken language, speaker's sex, and mask type.

This effect was particularly observed in voice samples collected from Hungarian speakers of both sexes, with a significant deterioration in the EER error rate when the samples were recorded without a mask, with a surgical mask, and with the FFP2 mask, in that order. It is assumed that the phonetic characteristics of the Hungarian language make it more sensitive to the effect of masks.

The decrease of the EER value calculated from samples collected not wearing a face mask was also seen in Croatian language in both sexes; however, no difference between surgical masks and FFP2 masks was present.

No significant difference in EER results was observed for Georgian, Portuguese, and Turkish speakers of both sexes, women’s speaking in Ukrainian and Romanian, as well as for Lithuanian male speakers.

EER value decreased with the presence of both masks for male Romanian speakers and male Ukrainian speakers when the FFP2 mask was used. Considering the Lithuanian female voice samples no conclusions could be drawn.

Analysis of the Cllr (CV) data trained with the cross-validation procedure shows that in general the calibration index deteriorates with mask wearing, but here again the results are quite scattered. In addition, potential outliers can be observed for Hungarian and Croatian female speaker samples, which require further research directions.

Furthermore, the measurement data from the present study show that female speakers' values differ more than those of male speakers in several situations. This means that female speech voices are more suppressed by different types of masks. This is presumably due to the phonetic-acoustic characteristics of the female speech voice, but further research is needed to elucidate this phenomenon.

5. Future work

Test if the system performance affected when comparisons are made with samples obtained via mobile and landline communications.

Add more languages to the FMVD.

Development of a mask detector tool from speech signals.

Funding

The project CERTAIN-FORS (ISFP-2020-AG-IBA-ENFSI) is funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police. The content of this work represents the views of the authors only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets presented in this article are not readily available because, as they are of biometric origin and in accordance with the design of the CERTAIN-FORS project, they will only be shared among ENFSI-FSAAWG members. The informed consent form that each volunteer signed is clear about the distribution and applicability of the data collected.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the CERTAIN-FORS project, funded by the EU and coordinated by ENFSI. We thank the colleagues from the FSAAWG that collaborated in the sampling process, namely Liudmyla Otroshenko from the State Scientific Research Forensic Center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, Cristian Diaconescu from the National Forensic Institute from the General Inspectorate of Romanian Police, Major Muharrem Davulcu from the Gendarmerie Forensics Department in Türkiye, Sunčica Kuzmić from the Forensic Science Centre “Ivan Vučetić” in Croatia, Mariam Navadze from the Georgian National Forensic Bureau, Carlos Delgado from Policía Nacional in Spain, Vasile Dan-Sas from the National Institute of Forensic Expertise in Romania, and Voskanyan Patvakan from National Bureau of Expertises of the Republic of Armenia. We also thank to the project manager and ENFSI Secretariat.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Waghmare, K.; Gawali, B. Speaker Recognition for forensic application: A Review. JPSP 2022, 6, 984–992. [Google Scholar]

- Drygajlo, A. (École Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne and School of Forensic Science, Lausanne, Switzerland); Jessen, M. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Gfroerer, S. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Wagner, I. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Vermeulen, J. (Netherlands Forensic Institute, The Hague, Netherlands); Niemiec, D. (Central Forensic Laboratory of the Police, Warsaw, Poland); Niemi, T. (National Bureau of Investigation Forensic Laboratory, Vantaa, Finland). ENFSI Methodological Guidelines for Best Practice in Forensic Semiautomatic and Automatic Speaker Recognition, 2015. (Available: https://enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/guidelines_fasr_and_fsasr_0.pdf).

- Jessen, M. Forensic voice comparison. In Handbook of Communication in the Legal Sphere; Visconti, J., Ed.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 219–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Boss, D. (Bavarian State Bureau of Investigation Forensic Science Institute, Munich, Germany); Hughes, V. (Department of Language and Linguistic Science, University of York, York, UK); Svirava, T. (The North-Western Regional Centre of Forensic Science of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation, St. Petersburgh, Russian Federation); Siparov, I. (ACUSTEK, Ltd., St. Petersburg, Russia); Rolfes, M. (Berlin State Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Berlin, Germany). ENFSI Best Practice Manual for the Methodology of Forensic Speaker Comparison, 2022. (Available: https://enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/5.-FSA-BPM-003_BPM-for-the-Methodology-1.pdf).

- Basu, N.; Bali, A.S.; Weber, P.; Rosas-Aguilar, C.; Edmond, G.; Martire, K.A.; Morrison, G.S. Speaker identification in courtroom contexts – Part I: Individual listeners compared to forensic voice comparison based on automatic-speaker-recognition technology. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 341, 111499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, G. S.; Enzinger, E. Introduction to forensic voice comparison. In The Routledge Handbook of Phonetics; Katz, W.F., Assmann, P.F., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 599–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J. H. L.; Hasan, T. Speaker recognition by machines and humans: A tutorial review. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2015, 32, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.S.; Sahito, F.H.; Jardine, G.; Djokic, D.; Clavet, S.; Berghs, S.; Dorny, C.G. INTERPOL survey of the use of speaker identification by law enforcement agencies. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 263, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, E.; French, P. International Practices in Forensic Speaker Comparison. Int. J. Speech Lang. Law 2011, 18, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E.; French, P. International Practices in Forensic Speaker Comparisons: Second Survey. Int. J. Speech Lang. Law 2019, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygajlo, A.; Haraksim, R. Biometric Evidence in Forensic Automatic Speaker Recognition. In Handbook of Biometrics for Forensic Science, Advances in Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Tistarelli, M., Champod, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.S.; Enzinger, E.; Ramos, D.; González-Rodríguez, J.; Lozano-Díez, A. Statistical Models in Forensic Voice Comparison. In Handbook of Forensic Statistics; Banks, D.L., Kafadar, K., Kaye, D.H., Tackett, M., Eds.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, USA, 2020; pp. 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G. S.; Enzinger, E.; Hughes, V.; Jessen, M.; Meuwly, D.; Neumann, C.; Planting, S.; Thompson, W.C.; van der Vloed, D.; Ypma, R.J.F.; Zhang, C. Consensus on validation of forensic voice comparison. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Javed, A.; Malik, K.M.; Raza, M.A.; Ryan, J.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Malik, H. Toward Realigning Automatic Speaker Verification in the Era of COVID-19. Sensors 2022, 22, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karawi, K.A. Face mask effects on speaker verification performance in the presence of noise. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 4811–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidi, R.; Niemi, T.; Karppelin, H.; Pohjalainen, J.; Kinnunen, T.; Alku, P. Speaker Recognition for Speech Under Face Cover. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2015, Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Dresden, Germany, 6-10 September 2015; pp. 1012–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, R.; Huhtakallio, I.; Alku, P. Analysis of face mask effect on speaker recognition. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2016, Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, San Francisco, USA, 8-12 September 2016; pp. 1800–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iszatt, T.; Malkoc, E.; Kelly, F.; Alexander, A. Exploring the impact of face coverings on x-vector speaker recognition using VOCALISE. In Proceedings of the IAFPA 2020/2021, 29th International Association of Forensic Phonetics and Acoustics, 26 July 2021, Marburg, Germany (online).

- Fecher, N. The ‘Audio-Visual Face Cover Corpus’: Investigations into audio-visual speech and speaker recognition when the speaker’s face is occluded by facewear. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2012, Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication, Portland, USA, 9-13 September 2012; pp. 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanel, G.; Belghazi-Mohamed, N.; Gómez-Moreno, H.; Lafuente-Arroyo, S. Study on the Effect of Face Masks on Forensic Speaker Recognition. Proceedings of Information and Communications Security: 24th International Conference, ICICS 2022, Canterbury, UK, 5-8 September 2022; pp. 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V. V.; Dassie-Leite, A. P.; Pereira, E. C.; Santos, A. D. N.; Martins, P.; Irineu, R. de A. Effect of Wearing a Face Mask on Vocal Self-Perception during a Pandemic. J. Voice 2022, 36, 878.e1–878.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, P.; Lu, Q.; Guo, H.; Zeng, J. The effects of face mask on speech production and its implication for forensic speaker identification-A cross-linguistic study. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0283724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, F.; Forth, O.; Kent, S.; Gerlach, L.; Alexander, A. Deep neural network based forensic automatic speaker recognition in VOCALISE using x-vectors. In Proceedings of the AES 2019, International Conference on Audio Forensics, Porto, Portugal, 18-20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, N.; Leeuwen van, D. On calibration of language recognition scores. In Proceedings of the IEEE Odyssey - The Speaker and Language Recognition Workshop, San Juan, PR, USA, 28-30 June 2006; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, R.; Slooten, K. Probability and forensic evidence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Example of the pre-processing process. The upper track is the original recording; the middle and down tracks represent samples obtained after pre-processing with different thresholds and respective amounts of seconds removed.

Figure 1.

Example of the pre-processing process. The upper track is the original recording; the middle and down tracks represent samples obtained after pre-processing with different thresholds and respective amounts of seconds removed.

Figure 2.

EER results obtained from Croatian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 2.

EER results obtained from Croatian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 3.

EER results obtained from Hungarian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 3.

EER results obtained from Hungarian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 4.

EER results obtained from Georgian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 4.

EER results obtained from Georgian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 5.

EER results obtained from Portuguese voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 5.

EER results obtained from Portuguese voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 6.

EER results obtained from Turkish voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 6.

EER results obtained from Turkish voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 7.

EER results obtained from Romanian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 7.

EER results obtained from Romanian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 8.

EER results obtained from Ukrainian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 8.

EER results obtained from Ukrainian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 9.

EER results obtained from Lithuanian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 9.

EER results obtained from Lithuanian voice samples measurements: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 10.

Variation of EER results by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 10.

Variation of EER results by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 11.

Cllr results based on measurements using Croatian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 11.

Cllr results based on measurements using Croatian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 12.

Cllr results based on measurements using Georgian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 12.

Cllr results based on measurements using Georgian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 13.

Cllr results based on measurements using Hungarian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 13.

Cllr results based on measurements using Hungarian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 14.

Cllr results based on measurements using Lithuanian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 14.

Cllr results based on measurements using Lithuanian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 15.

Cllr results based on measurements using Portuguese voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 15.

Cllr results based on measurements using Portuguese voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 16.

Cllr results based on measurements using Romanian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 16.

Cllr results based on measurements using Romanian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 17.

Cllr results based on measurements using Turkish voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 17.

Cllr results based on measurements using Turkish voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 18.

Cllr results based on measurements using Ukrainian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 18.

Cllr results based on measurements using Ukrainian voice samples by sex: (a) females; (b) males.

Figure 19.

Variation of Cllr (CV) results by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 19.

Variation of Cllr (CV) results by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Table 1.

Models of recording equipment used and sampling rates adopted in each forensic institute.

Table 1.

Models of recording equipment used and sampling rates adopted in each forensic institute.

| Countries |

Recorder device(s) |

Sample rate (kHz) |

| Croatia (HR) |

Zoom ZDM-1 / Zoom H4n PRO |

8 |

| Georgia (KA) |

Stagg MD-1500 / Philips DVT6000 |

44.1 |

| Hungary (HU) |

Audio-Technica AT897 / Steinberg U28M |

8 |

| Lithuania (LT) |

Marantz PMD660 |

8 |

| Portugal (PT) |

Behringer B-1 / Newer NW-800

Tascam DR-40X / Tascam DR-40 |

44.1 |

| Romania (RO) |

Olympus ME52W / Behringer B-1 |

8 |

| Türkiye (TR) |

König K-CM700 / Shure SM48 |

8 |

| Ukraine (UA) |

Zoom F1-LP |

8 |

Table 2.

Number of volunteers by language, age, and sex, whose voice samples were used in the present study.

Table 2.

Number of volunteers by language, age, and sex, whose voice samples were used in the present study.

| Age classes |

[18 – 30] |

[31 – 40] |

[41 – 50] |

[51 - +∞) |

Total |

| Languages |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

| Croatian (HR) |

9 |

10 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| Georgian (KA) |

10 |

10 |

11 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

78 |

| Hungarian (HU) |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| Lithuanian (LT) |

15 |

17 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

9 |

6 |

11 |

80 |

| Portuguese (PT) |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| Romanian (RO) |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| Turkish (TR) |

5 |

26 |

21 |

11 |

14 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

| Ukrainian (UA) |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).