1. Introduction

Forensic speaker recognition (aka forensic speaker comparison) aims to compare one or several recordings of a questioned speaker with one or several recordings of a suspect, and has been receiving a lot of interest given that it plays a key role in criminal investigations, delivering important conclusions to the Justice System. It differs from regular speaker recognition in several ways, including short utterances, background noises, low voice quality, among others technical aspects. No less important is the approach itself, especially the level of robustness, accuracy and reproducibility given that the conclusions have a direct impact in solving crimes [

1,

2,

3].

Three main approaches can be distinguished: auditory-phonetic based on the auditory examination of recordings by trained phoneticians or linguists; acoustic-phonetic methods involving the measurement of various acoustic parameters such as fundamental frequency and its variation, formant frequencies and speech tempo; automatic and semiautomatic speaker recognition in which the central processing stages (feature extraction, feature modelling, similarity scoring and likelihood ratio computation) operates fully or partial automatically [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in the use of protective face masks, given their mandatory use in almost every daily situation, preventing the virus from spreading. However, the use of face masks has also had an impact on speech processing technologies as they act as voice barriers or filters, affecting not only the acoustic properties of the signal but also the speech patterns, introducing both consequential and adaptative changes in the human voice [

9,

10].

Although the COVID pandemic was declared finished, forensic laboratories continues to receive requests for analysis of investigations relating to the pandemic period once the time of justice always refer to activities that took place previously. For example, contracts made using identity theft with a telecommunications or insurances companies during the pandemic are now being investigated. Also, the number of citizens who have kept the habit of wearing a protective mask, especially if we look at airports, is not negligible. On the other hand, this study contributes to better knowledge of the impact of using masks as disguise voice technique.

The present study focuses on the impact of face masks in seven acoustic parameters used in acoustic-phonetic approach for speaker recognition. A subsequent study on the effect of the presence of protection masks in forensic automatic speaker recognition (FASR) systems is being performed and will be presented in a near future. Both studies make use of the Forensic Multilingual Voices Database (FMVD), developed under the “Competency, Education, Research, Testing, Accreditation, and Innovation in Forensic Science” (CERTAIN-FORS) project, funded by the European Union (EU) and coordinated by European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ENFSI).

2. Related Work

Analyses have been conducted on sustained vowels produced with and without a face mask. Some studies detected no acoustic differences in terms of fundamental frequency (F

0), jitter, shimmer, and harmonics-to-noise ratio (HNR), first and second formants (F

1 and F

2), between samples obtained from individuals not wearing protection masks and wearing surgical masks [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Joshi et al. also did not observe differences between the cloth and KN95 type’s masks [

14]. However, Gojayev et al. found significant differences in HNR and shimmer when FFP3 masks were used [

13]. Lin et al. observed a higher sound pressure level (SPL), a small decrease in jitter and shimmer, and an evident decrease in F

3 when wearing clinical masks [

15]. Georgiou found that F

2 was altered by the effects of both cotton and surgical face masks [

16].

Considering acoustic analysis on continuous speech, Magee et al. [

17] found that power distribution in frequency, measures of timing, and spectral tilt were significantly impacted by wearing an N95-type mask; cepstral and harmonics-to-noise ratios remained unchanged for all masks (surgical, N95, and cloth). Nguyen et al. [

18] found significant attenuation of mean spectral level in the 1–8 kHz region and no significant change at 0–1 kHz when wearing face masks (surgical and KN95). Knowles and Badh [

19] studied the effect of surgical and KN95-type masks in different speech styles (normal, loud, and clear), obtaining results in line with the previous studies and consistent across all three speech styles.

Nguyen et al. [

20] also investigated the impact of face masks on the acoustic features of fricatives, observing significant lower root mean square amplitude and /f/ center of gravity when wearing a N95-type mask compared with non-mask conditions. These results were consistent with previous studies performed by Fecher and Watt [

21] and Saigusa [

22].

It is important to mention that all results from the above-discussed studies were obtained with small datasets.

Latoszek et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of protective face coverings on acoustic markers in voice [

23]. The authors found nine eligible studies, resulting in 422 participants, and the results from the meta-analysis did not show significant differences between the absence and presence of masks.

To evaluate the effects of face masks on speech production between Mandarin Chinese and English and their implications for forensic speaker identification, Geng et al. [

24] performed a cross-linguistic study. Voice samples were collected from thirty volunteers who were Mandarin native speakers and fluent in English as a second language. Each participant gave two text-reading samples: one in Mandarin without a mask, one in Mandarin wearing a surgical mask, one in English without a mask, and one in English wearing a surgical mask. The results of acoustic analysis showed that mask speech exhibited higher F

0, intensity, HNR, and lower jitter and shimmer than no mask speech for Mandarin, whereas higher HNR, lower jitter, and shimmer were observed for English mask speech.

3. Materials and Methods

The FMVD was developed with the collaboration of several Forensic Institutes, members of the ENFSI Forensic Speech and Audio Analysis Working Group (FSAAWG), representing nine countries: Lithuania (LT), Croatia (HR), Romania (RO), Türkiye (TR), Ukraine (UA), Portugal (PT), Georgia (KA), Hungary (HU), and Spain (ES).

All samples were collected from volunteers who signed an informed consent statement designed for the development and distribution of the FMVD among ENFSI FSAAWG members. Each person was recorded reading a selected text without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing an FFP2 mask (FP). A small number of samples in Russian (RU), Polish (PL), and German (DE) languages were also recorded, given the existence of native speakers in the collaborating Forensic Institutes.

Samples from mobile (MB) communications in Lithuanian, Croatian, Portuguese and Spanish, and landline (LL) communications in Lithuanian, Polish and Russian were also collected, however, in some cases in a small number.

The project provided the masks and the text, controlling as possible the sampling process. An excerpt from “The Little Prince,” written by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, was selected, avoiding translation issues once this book is already translated in almost every language. Recording device models used in each of the participating countries and the respective sampling rates of the obtained voice samples are presented in

Table 1. All recordings were made in WAV format, mono signal, resolution of 16 bits, indoors, and approximately 2.5 minutes long. Acoustic conditions could not be normalized once the collection process took place in several audio laboratories from different countries.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the 860 volunteers by language, sex, and recording channel: microphone or recorder, mobile (MB), and landline (LL) communications. Given their reduced size, subsets with less than 10 samples were left out of the presenting study, namely voice samples in German and Polish languages; Spanish, Croatian, and Lithuanian mobile recordings; and landline communications in Russian.

Recordings were pre-processed using a Matlab tool developed for removing silences from voice samples according to a background noise threshold. The same threshold was applied to all the samples from each subset of data per language and recording channel, resulting in over 116 hours of recordings for the study.

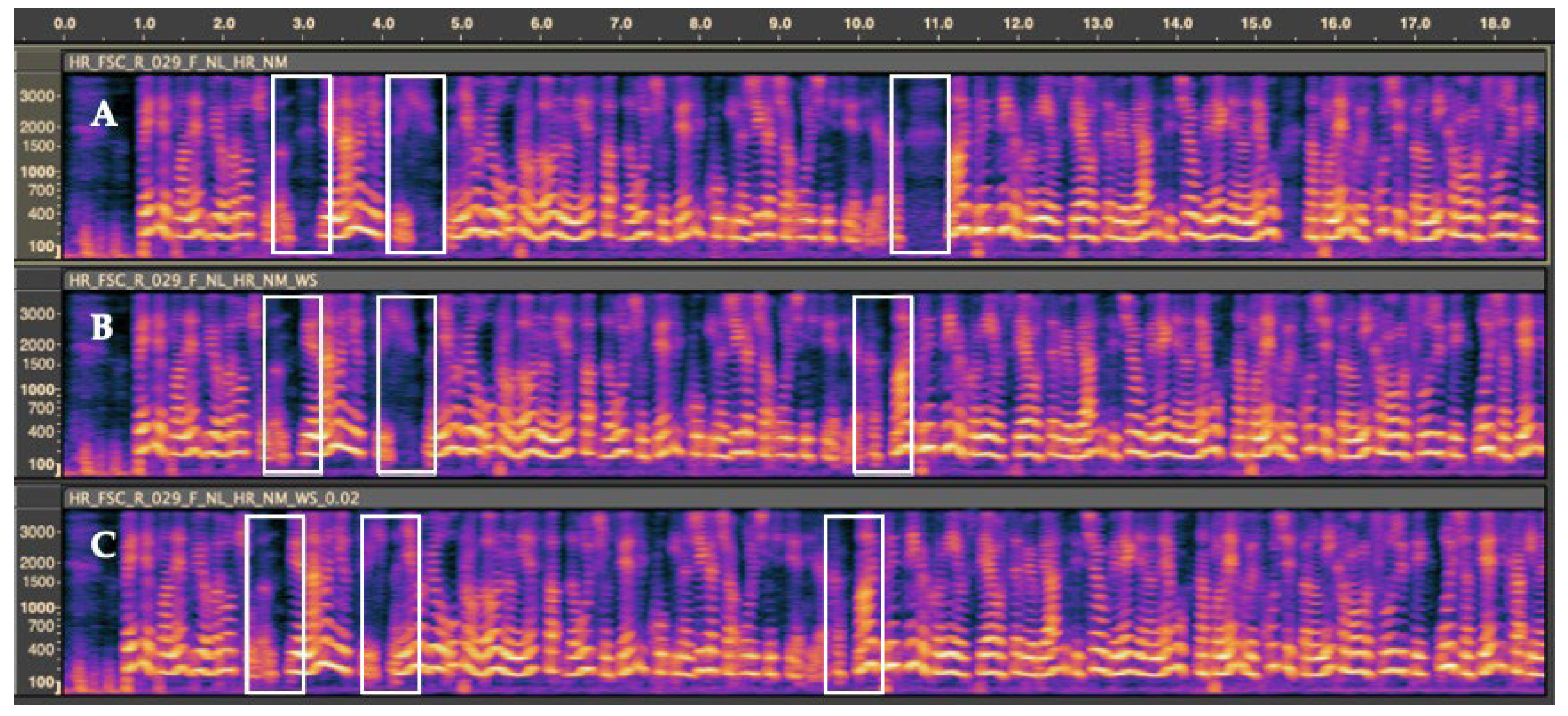

Figure 1 presents an example of the silence removal pre-processing process.

Seven acoustic parameters were chosen to be studied: F

0, difference between 1st and 2nd harmonics (H

1-H

2), intensity, speech rate, HNR, jitter, and shimmer, as they are used in speaker recognition, particularly on the acoustic-phonetic approach [

5,

6,

8,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Their computation was performed using Praat (version 6.3.06).

Statistical analysis was conducted using Minitab Statistical Software (version 21.4.2). Since it was found that the requirements for carrying out an analysis of variance (ANOVA) were not satisfied, namely the normality of the residuals, for each language and sex, a linear mixed effects model was applied to analyse statistical differences on the above parameters between with and without each face mask type, using subjects as a random factor. A similar approach was used by by Geng et al. [

24].

4. Results

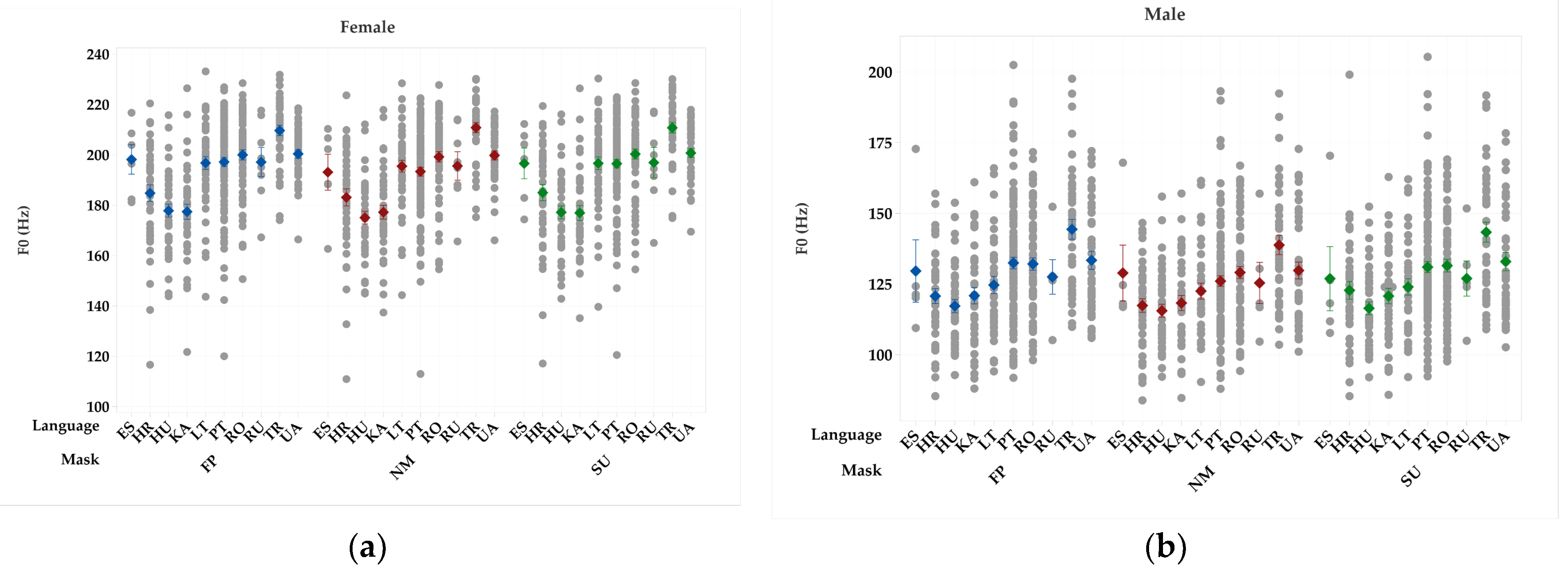

Observation of the spectrograms showed that the face masks work as a low-pass filter at approximately 1 kHz (

Figure 2). This observation is in accordance with previous studies findings [

17,

18,

29].

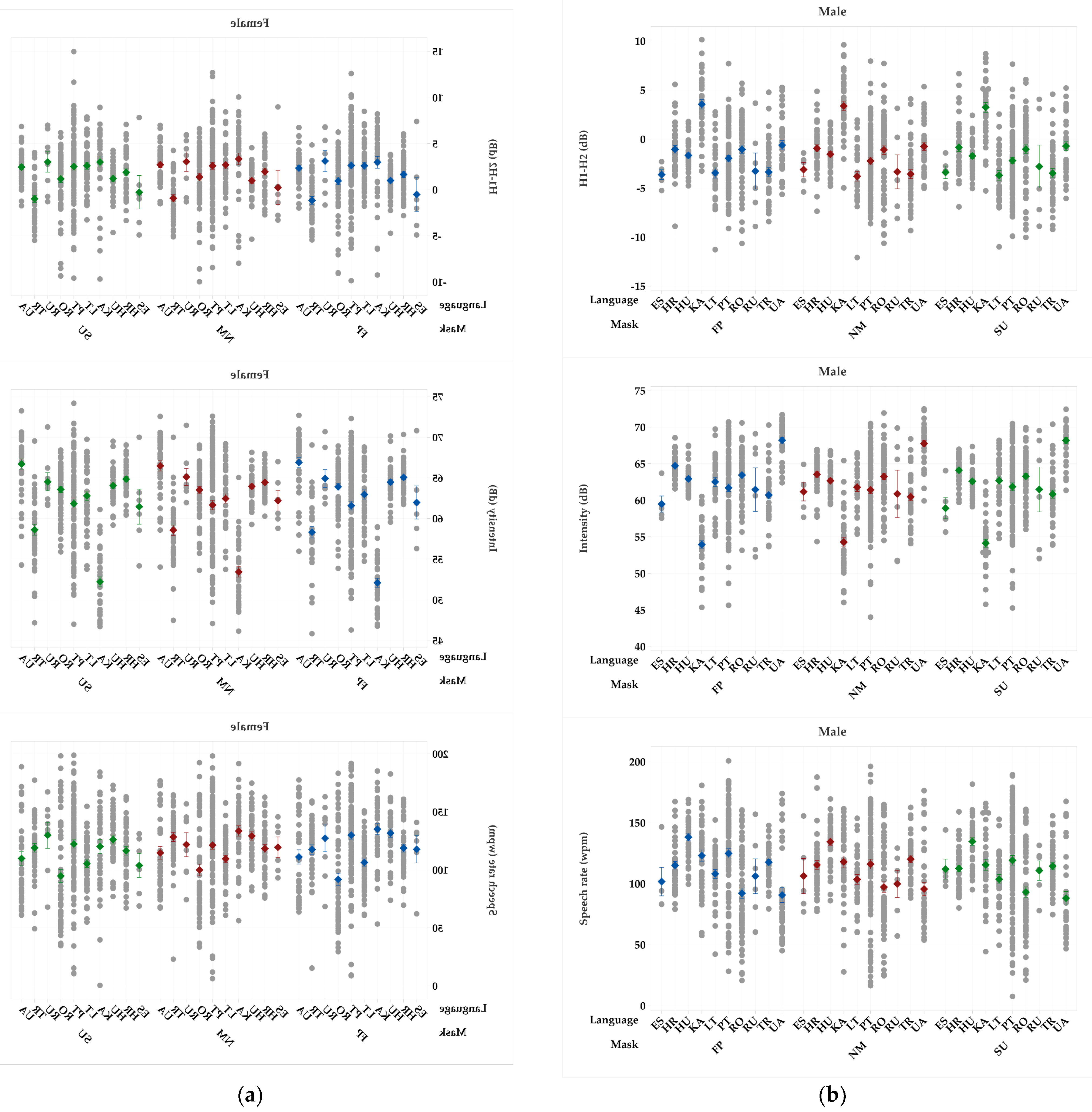

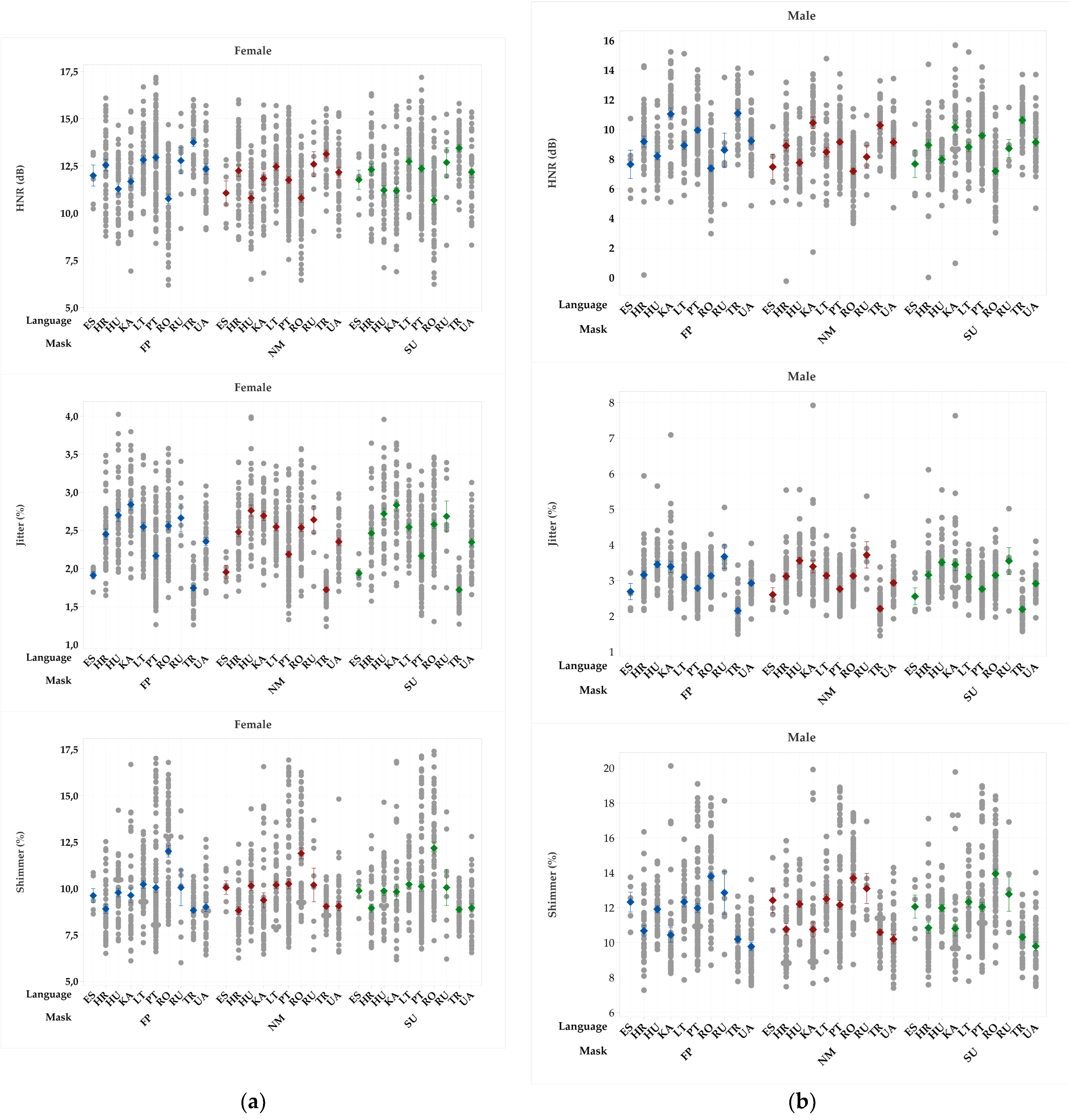

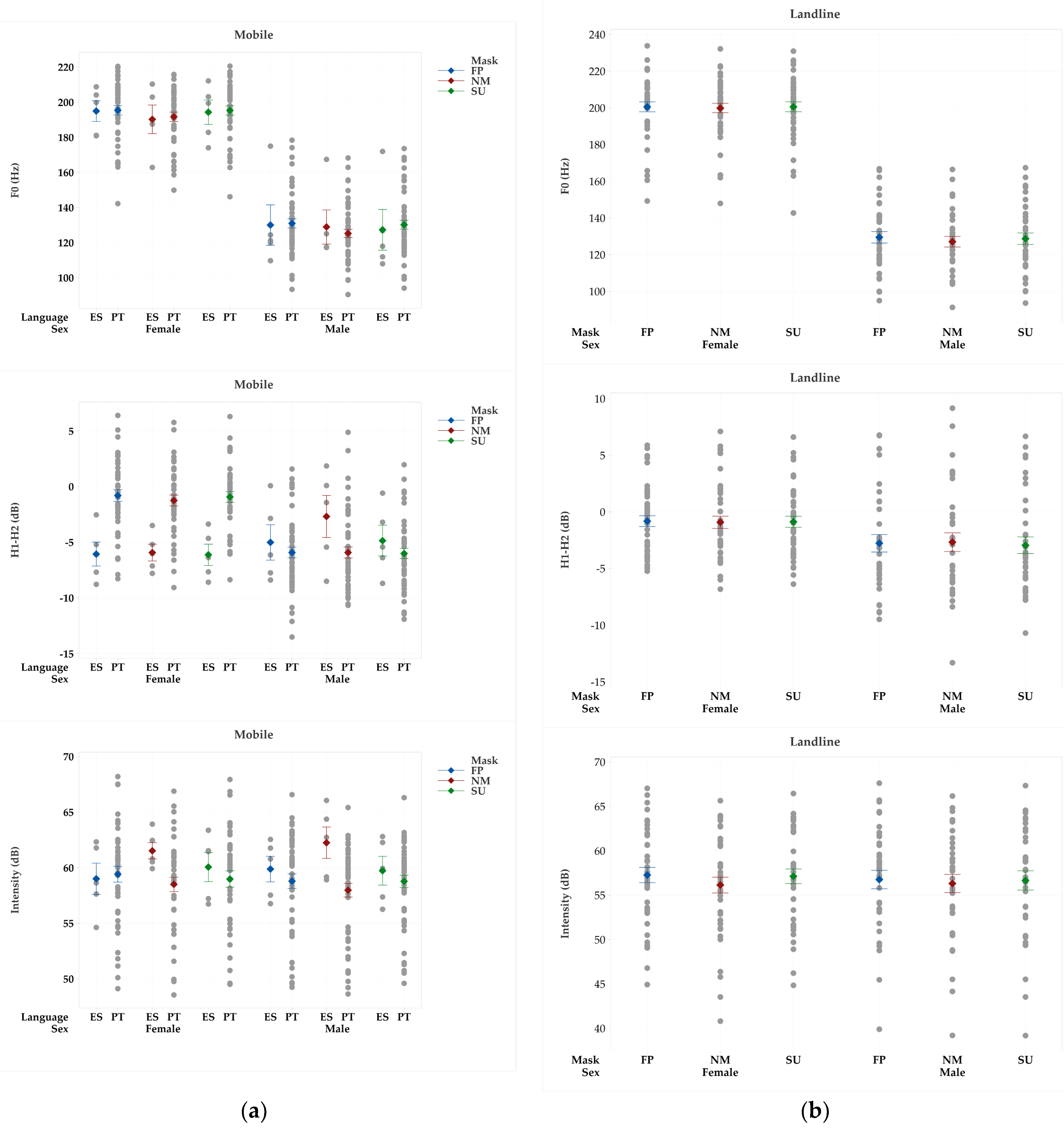

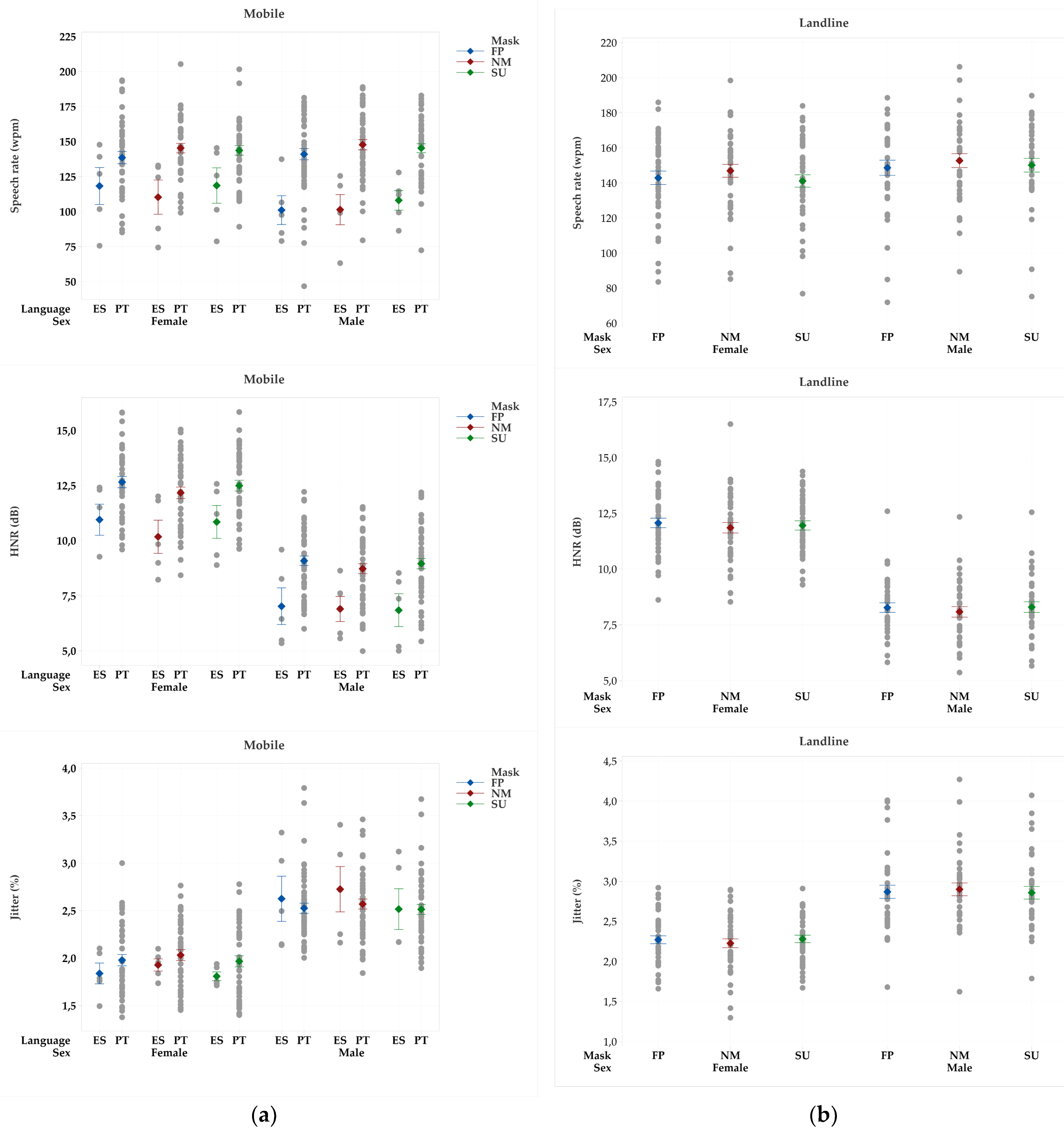

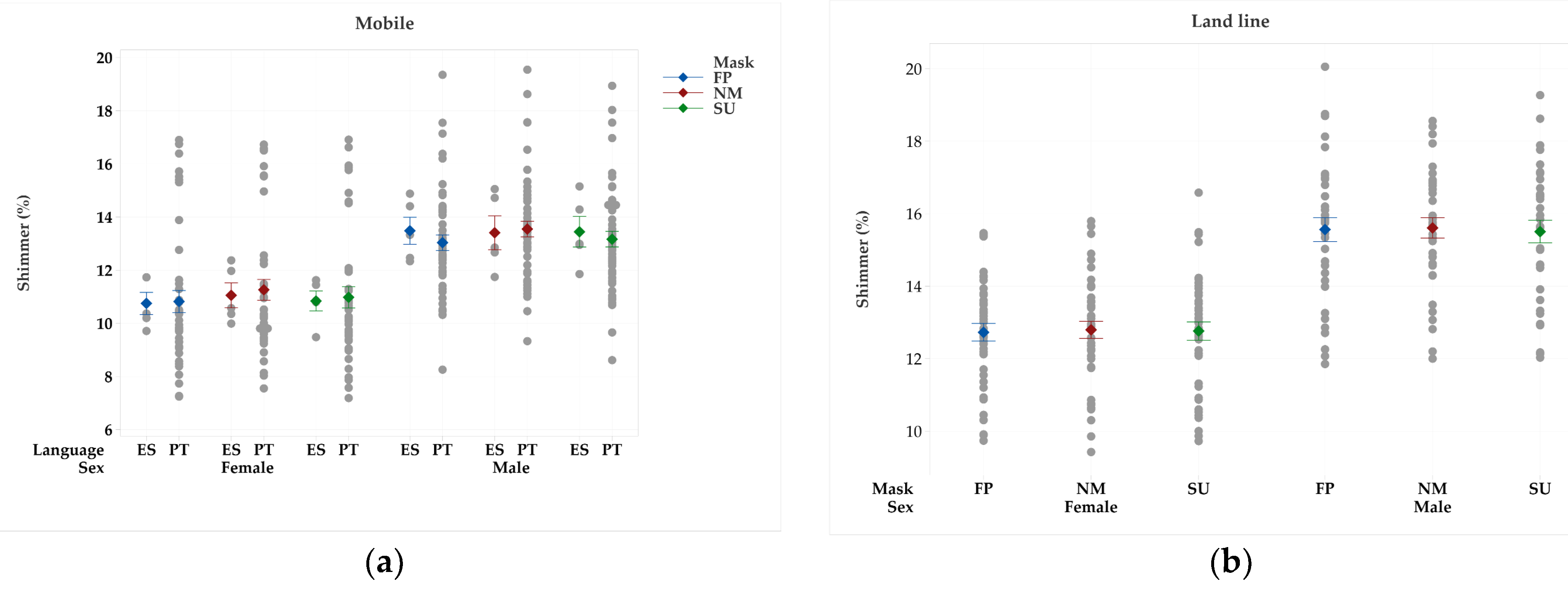

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 shows the average and standard error values of the seven acoustic parameters obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder, by language, sex and mask type. Results for the same quantities obtained from mobile and landline recordings are presented in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the linear mixed effects model on the acoustic parameters, by sex and mask type, for all languages recorded with a microphone or recorder.

For the samples collected with a microphone or recorder, preliminary observations show that the protection masks have almost no effect on the smallest subsets of data, namely RU and ES. Given the overall results for the rest of the dataset, this observation indicates the need to take more samples to better assess the impact of protective masks on acoustic parameters in these languages.

The presence of a face mask was significant for F0 in almost all men, regardless of the spoken language; only HU males wearing SU masks were unaffected. F0 in females wearing SU masks speaking in PT, LT, and HR was significantly affected, as well as in PT and HU females wearing FFP2 masks. The impact of wearing face masks translates into an increase in F0.

Face masks were statistically significant for shimmer in TR, PT, and HU speakers and UA males. SU masks revealed a significant impact on shimmer in both genders speaking RO and females speaking KA.

The overall effect translates to a decrease in shimmer average value with the exception of SU masks in RO speakers in which an increase in shimmer’s value was observed.

HNR was significantly affected by the presence of masks in both genders speaking LT, TR, PT, and HU. FFP2 masks showed a significant impact on HNR in HR speakers of both genders and in RO males. SU masks affected the same parameter in females speaking KA. The presence of face masks caused an increase in the HNR average value except for KA females, for which a decrease in HNR was observed.

A significant effect on speech rate was observed in RO speakers, TR females, and UA males. SU masks affected females speaking in LT, UA, and KA, as well as TR males’ speakers. FFP2 masks showed a significant effect on both males and females’ PT speakers. The effect of face masks is characterized by a decrease in speech rate, apart from PT speakers, where an increase in speech rate was detected.

The presence of protection masks for jitter was statistically significant in KA females, leading to an increase in its value, and in TR and HU male speakers wearing an FFP2 mask, for which a decrease in jitter value was observed.

Intensity was significantly affected by the presence of masks in UA males, KA females, and LT of both genders. FFP2 masks showed an impact on intensity in females speaking RO, UA, and HU, as well as in both males and females’ HK speakers. SU masks revealed an impact on intensity only in PT male speakers. Intensity increased with the presence of protection masks except in KA females’ speakers, which presented a decrease in its value when wearing an FFP2 mask.

A significant effect on H1-H2 was observed in UA females. FFP2 masks affected females speaking in HR and RO, as well as LT and PT males’ speakers. SU masks showed a significant effect on females’ HU speakers. The effect of face masks is characterized by an increase in H1-H2 for male speakers and a decrease in its value for females, apart from HU female speakers, where an increase in H1-H2 was detected.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the linear mixed effects model on the acoustic parameters, by sex and mask type, for Spanish and Portuguese mobile communications samples, and for Lithuanian landline recordings.

The results of the linear mixed effects model applied to the samples obtained via mobile communications (

Table 4) revealed, for PT speakers, a significant effect on F

0, HHR, and shimmer in both genders, on intensity for males and on H

1-H

2 for females’ speakers. SU masks revealed a significant impact on jitter in both genders. Speech rate was affected in females wearing FFP2. The effects were translated into an increase in F

0, H

1-H

2, intensity, and HNR average values and a decrease in speech rate, jitter, and shimmer.

The analysis performed on mobile recordings collected in ES language showed a significant impact on intensity for male speakers and females wearing FFP2 masks. FFP2 masks significantly affected speech rate, intensity, and shimmer for males and jitter for females. Both mask types revealed an impact on HNR and H1-H2 for female speakers.

Recordings via landline communications were studied only for LT speakers, and the results revealed a significant effect on intensity in female speakers wearing both masks and males wearing a FFP2 mask. F

0 was affected in males (

Table 4). These effects led to an increase in both parameters’ values.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the impact of two types of protection masks on seven acoustic parameters used in the acoustic-phonetic approach for forensic speaker recognition by sex and language.

The results showed that F0, H1-H2, intensity, speech rate, HNR, jitter, and shimmer were affected by the presence of face masks, denoting different behaviours depending on mask type, sex, language and recording channel.

An increase in F0, particularly in males, was observed in the presence of face masks of both types. Also, an overall increase in HNR was detected, as was an increase in intensity, more evident when wearing FFP2 masks. A decrease was denoted in shimmer value, as well as in speech rate, for which females wearing SU masks were more affected. The effect of face masks on H1-H2 was characterize by an increase of its value for males and a decrease for female speakers. Jitter was the less affected parameter, still denoting changes in the presence of FFP2 masks for both genders.

These findings support that, in the presence of face masks, which act as a low pass acoustic filter, speakers tend to perform phonetic and acoustic adjustments to compensate for the filter effect, trying to improve speech intelligibility [

10,

24,

30,

31].

The results for recordings via mobile communications show that F0, HNR, and shimmer were affected in a similar way to the samples collected with a microphone or recorder. On the other hand, intensity was more affected by the presence of masks in mobile recordings; speech rate decreased in mobile communications and increased in microphone recordings; jitter was significantly affected in mobile communications when in microphone recordings a small impact was observed; and the impact on H1-H2 revealed a different behaviour from the one observed in microphone recordings, increasing its value for females and decreasing for male speakers. These comparisons were only possible for ES and PT voice recordings.

When comparing the obtained results for landline and microphone or recorder samples, different responses were also observed. Only F0 and intensity were significantly affected in landline communications, while in samples recorded with a microphone or recorder, only jitter and shimmer showed no significant impact in the presence of protective masks. These comparisons were only possible for LT voice recordings.

Given the observed impact of face masks on the studied acoustic parameters, care must be taken when performing acoustic-phonetic forensic speaker recognition examinations.

7. Future work

Increase the number of samples in languages with smaller datasets.

Collect more samples from mobile and landline communications to assess if the impact of face masks is also language dependent in these channels.

Add more languages to the FMVD.

Study the impact of face masks in more acoustic parameters.

Finish the ongoing study about the impact of face masks on the FASR approach.

Development of a mask detector tool from speech signals

Funding

The CERTAIN-FORS project was funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police (101051099) and coordinated by European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ISFP-2020-AG-IBA-ENFSI). The content of this work represents the views of the authors only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because, according to the CERTAIN-FORS project designed it will only be shared within the ENFSI-FSAAWG members. The informed consent form that each volunteer signed is clear on the distribution and applicability of the collected data.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the CERTAIN-FORS project, funded by the EU and coordinated by ENFSI. We thank the colleagues from FSAAWG members that collaborated in the sampling process, namely Liudmyla Otroshenko from the State Scientific Research Forensic Center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, Cristian Diaconescu from the National Forensic Institute from the General Inspectorate of Romanian Police, Major Muharrem Davulcu from the Gendarmerie Forensics Department in Türkiye, Sunčica Kuzmić from the Forensic Science Centre “Ivan Vučetić” in Croatia, Mariam Navadze from the Georgian National Forensic Bureau, Carlos Delgado from Policía Nacional in Spain, and Vasile Dan-Sas from the National Institute of Forensic Expertise in Romania, the project manager and ENFSI Secretariat.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Waghmare, K.; Gawali, B. Speaker Recognition for forensic application: A Review. JPSP 2022, 6, 984–992. [Google Scholar]

- Hari, V.S.S.S.; Annavarapu, A.K.; Shesamsetti, V.; Nalla, S. Comprehensive Research on Speaker Recognition and its Challenges. Proceedings of 2023 3rd International Conference on Smart Data Intelligence (ICSMDI), Trichy, India, 30-31 March 2023; pp. 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.; Bali, A.S.; Weber, P.; Rosas-Aguilar, C.; Edmond, G.; Martire, K.A.; Morrison, G.S. Speaker identification in courtroom contexts – Part I: Individual listeners compared to forensic voice comparison based on automatic-speaker-recognition technology. Forensic Sci Int, 2022, 341, 111499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drygajlo, A. (École Polytechnique Féderale de Lausanne and School of Forensic Science, Lausanne, Switzerland); Jessen, M. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Gfroerer, S. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Wagner, I. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Vermeulen, J. (Netherlands Forensic Institute, The Hague, Netherlands); Niemiec, D. (Central Forensic Laboratory of the Police, Warsaw, Poland); Niemi, T. (National Bureau of Investigation Forensic Laboratory, Vantaa, Finland) ENFSI Methodological Guidelines for Best Practice in Forensic Semiautomatic and Automatic Speaker Recognition, 2015. (Available: https://enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/guidelines_fasr_and_fsasr_0.pdf).

- Jessen, M. Forensic voice comparison. In Handbook of Communication in the Legal Sphere; Visconti, J., Ed.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G. S.; Enzinger, E. Introduction to forensic voice comparison. In The Routledge Handbook of Phonetics; Katz, W.F., Assmann, P.F., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, England, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J. H. L.; Hasan, T. Speaker recognition by machines and humans: A tutorial review. IEEE Signal Process Mag 2015, 32, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I. (Federal Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Wiesbaden, Germany); Boss, D. (Bavarian State Bureau of Investigation Forensic Science Institute, Munich, Germany); Hughes, V. (Department of Language and Linguistic Science, University of York, York, UK); Svirava, T. (The North-Western Regional Centre of Forensic Science of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation, St. Petersburgh, Russian Federation); Siparov, I. (ACUSTEK, Ltd., St. Petersburg, Russia); Rolfes, M. (Berlin State Criminal Police Office, Forensic Science Institute, Berlin, Germany). ENFSI Best Practice Manual for the Methodology of Forensic Speaker Comparison, 2022. (Available: https://enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/5.-FSA-BPM-003_BPM-for-the-Methodology-1.pdf).

- Gama, R.; Castro, M. E.; Lith-Bijl, J. T. van, Desuter, G. Does the wearing of masks change voice and speech parameters? EuroArch Oto-Ehino-L 2022, 279, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekaraiah, S.; Suresh, K. Effect of Face Mask on Voice Production During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. J. Voice, 2021, 38, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallaro, G.; Nicola, V. Di; Quaranta, N.; Fiorella, M. L. Acoustic voice analysis in the COVID-19 era. Acta Otorhinolaryngo 2021, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorella, M. L.; Cavallaro, G.; Nicola, V. Di; Quaranta, N. Voice Differences When Wearing and Not Wearing a Surgical Mask. J. Voice 2023, 37, e1–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gojayev, E. K.; Büyükatalay, Z. Ç.; Akyüz, T.; Rehan, M.; Dursun, G. The Effect of Masks and Respirators on Acoustic Voice Analysis During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Voice 2024, 38, e1–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Procter, T.; Kulesz, P. A. COVID-19: Acoustic Measures of Voice in Individuals Wearing Different Facemasks. J. Voice 2023, 37, e1–e971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, W. Effects of Medical Masks on Voice Assessment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Voice 2023, 37, e25–e802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, G. P. Acoustic markers of vowels produced with different types of face masks. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 191, 108691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, M.; Lewis, C.; Noffs, G.; Reece, H.; Chan, J.C.S.; Zaga, C.J.; Paynter, C.; Birchall, O.; Azocar, S.R.; Ediriweera, A.; Kenyon, K.; Caverlé, M.W.; Schultz, B.G.; Vogel, A. Effects of face masks on acoustic analysis and speech perception: Implications for peri-pandemic protocols. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 3562–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D. D.; McCabe, P.; Thomas, D.; Purcell, A.; Doble, M.; Novakovic, D.; Chancon, A.; Madill, C. Acoustic voice characteristics with and without wearing a facemask. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, T.; Badh, G. The impact of face masks on spectral acoustics of speech: Effect of clear and loud speech styles. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2022, 151, 3359–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D. D.; Chacon, A.; Payten, C.; Black, R.; Sheth, M.; McCabe, P.; Novakovic, D.; Madill, C. Acoustic characteristics of fricatives, amplitude of formants and clarity of speech produced without and with a medical mask. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2022, 57, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecher, N.; Watt, D. Speaking under cover: The effect of face-concealing garments on spectral properties of fricatives. In Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Hong-Kong, Hong-Kong, 17-21 August 2011, 17–21.

- Saigusa, J. The Effects of Forensically Relevant Face Coverings on the Acoustic Properties of Fricatives. LS 2017, 3, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoszek, B.B. v.; Jansen, V.; Watts, C. R.; Hetjens, S. The Impact of Protective Face Coverings on Acoustic Markers in Voice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Lu, Q.; Guo, H.; Zeng, J. The effects of face mask on speech production and its implication for forensic speaker identification-A cross-linguistic study. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0283724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A. Phonetic-Oriented Identification of Twin Speakers Using 4-Second Vowel Sounds and a Combination of a Shift-Invariant Phase Feature (NRD), MFCCs, and F0 Information. In Proceedings of the 2019 AES International Conference on Audio Forensics, Porto, Portugal, 18-20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Fernandes, V. Consistency of the F0, Jitter, Shimmer and HNR voice parameters in GSM and VOIP communication. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), London, United Kingdom, 23-25 August 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Freitas, S.; Pestana, P. M.; Almeida, V.; Ferreira, A. Acoustic analysis of voice signal: Comparison of four applications software. Biomed. Signal Process Control 2018, 40, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Ferreira, A. On the Relevance of F0, Jitter, Shimmer and HNR acoustic parameters in forensic voice comparisons using GSM, VOIP and contemporaneous high-quality voice recordings. In Proceedings of the 2017 AES International Conference on Audio Forensics, Arlington, United States of America, 15-17 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Javed, A.; Malik, K.M.; Raza, M.A.; Ryan, J.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Malik, H. Toward Realigning Automatic Speaker Verification in the Era of COVID-19,” Sensors 2022, 22, 2638. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanel, G.; Belghazi-Mohamed, N.; Gómez-Moreno, H.; Lafuente-Arroyo, S. Study on the Effect of Face Masks on Forensic Speaker Recognition. Proceedings of Information and Communications Security: 24th International Conference, ICICS 2022, Canterbury, United Kingdom, 5-8 September 2022; pp. 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V. V.; Dassie-Leite, A. P.; Pereira, E. C.; Santos, A. D. N.; Martins, P.; Irineu, R. de A. Effect of Wearing a Face Mask on Vocal Self-Perception during a Pandemic. J. Voice 2022, 36, e1–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Example of the pre-processing process. A represents the original recording, B and C samples after pre-processing with different thresholds.

Figure 1.

Example of the pre-processing process. A represents the original recording, B and C samples after pre-processing with different thresholds.

Figure 2.

Spectrograms of voice samples recorded from the same subject without wearing a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing an FFP2 mask (FP).

Figure 2.

Spectrograms of voice samples recorded from the same subject without wearing a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing an FFP2 mask (FP).

Figure 3.

Average and standard error values of F0 (kHz) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 3.

Average and standard error values of F0 (kHz) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 4.

Average and standard error values of H1-H2 (dB), intensity (dB), and speech rate (wpm) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 4.

Average and standard error values of H1-H2 (dB), intensity (dB), and speech rate (wpm) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 5.

Average and standard error values of HNR (dB), jitter (%), and shimmer (%) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 5.

Average and standard error values of HNR (dB), jitter (%), and shimmer (%) obtained from the samples collected using a microphone or recorder without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 6.

Average and standard error values of F0 (kHz), H1-H2 (dB) and intensity (dB) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 6.

Average and standard error values of F0 (kHz), H1-H2 (dB) and intensity (dB) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 7.

Average and standard error values of speech rate (wpm), HNR (dB) and jitter (%) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 7.

Average and standard error values of speech rate (wpm), HNR (dB) and jitter (%) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 8.

Average and standard error values of shimmer (%) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Figure 8.

Average and standard error values of shimmer (%) obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications without a mask (NM), wearing a surgical mask (SU), and wearing a FFP2 type mask (FP), by language and sex: (a) female; (b) male.

Table 1.

Models of recording equipment used and respective sampling rates adopted in each of the participating countries.

Table 1.

Models of recording equipment used and respective sampling rates adopted in each of the participating countries.

| Countries |

Recorder device |

Sample rate (kHz) |

| ES - Spain |

Newer NW-800 |

48 |

| HR - Croatia |

Zoom ZDM-1 / Zoom H4n PRO |

8 |

| HU - Hungary |

Audio-Technica AT897 |

8 |

| KA - Georgia |

Stagg MD-1500 / Philips DVT6000 |

44.1 |

| LT - Lithuania |

Marantz PMD660 |

8 |

| PT - Portugal |

Behringer B-1 / Newer NW-800Tascam DR-40X / Tascam DR-40 |

44.1 |

| RO - Romania |

Olympus ME52W / Behringer B-1 |

8 |

| TR - Türkiye |

König K-CM700 / Shure SM48 |

8 |

| UA - Ukraine |

Zoom F1-LP |

8 |

Table 2.

Number of volunteers recorded with microphone or recorder and via mobile (MB) and landline (LL) communications, by language, age and sex.

Table 2.

Number of volunteers recorded with microphone or recorder and via mobile (MB) and landline (LL) communications, by language, age and sex.

| Age classes |

[18 - 30] |

[31 - 40] |

[41 - 50] |

[51–+∞) |

Total |

| Languages |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

| DE - German |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| ES - Spanish |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

11 |

| HR - Croatian |

9 |

10 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

83 |

| HU - Hungarian |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| KA - Georgian |

10 |

10 |

11 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

78 |

| LT - Lithuanian |

15 |

18 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

9 |

6 |

11 |

81 |

| PL - Polish |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

| PT - Portuguese |

25 |

32 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

24 |

25 |

212 |

| RO - Romanian |

13 |

11 |

12 |

16 |

21 |

21 |

24 |

16 |

134 |

| RU - Russian |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

14 |

| TR - Turkish |

5 |

26 |

21 |

11 |

14 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

| UA - Ukrainian |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

80 |

| ES - Spanish MB |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

10 |

| HR - Croatian MB |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| LT - Lithuanian MB |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

| PT - Portuguese MB |

8 |

10 |

16 |

13 |

11 |

11 |

14 |

8 |

91 |

| LT – Lithuanian LL |

17 |

15 |

9 |

8 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

11 |

78 |

| PL – Polish LL |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

| RU – Russian LL |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

9 |

Table 3.

Results of the mixed effect models on the acoustic parameters obtained from the samples collected by microphone or recorder, with no mask (NM) vs. surgical mask (SU) and no mask (NM) vs. FFP2 type mask as independent variables. The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance: * p < 0,05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Table 3.

Results of the mixed effect models on the acoustic parameters obtained from the samples collected by microphone or recorder, with no mask (NM) vs. surgical mask (SU) and no mask (NM) vs. FFP2 type mask as independent variables. The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance: * p < 0,05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

| Language |

Sex |

Mask type |

Linear mixed-effect models results on the acoustic parameters |

| F0

|

H1-H2

|

Intensity |

Speech rate |

HNR |

Jitter |

Shimmer |

| ES - Spanish |

F |

NM vs SU |

1.87 |

1.94 |

0.35 |

1.82 |

8.76* |

0.06 |

0.41 |

| NM vs FP |

1.97 |

2.26 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

27.22** |

0.17 |

4.27 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

0.33 |

0.29 |

7.33 |

0.5 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

1.26 |

| NM vs FP |

0.05 |

0.94 |

7.09 |

0.29 |

0.48 |

3.17 |

0.12 |

| HR - Croatian |

F |

NM vs SU |

7.89** |

0.31 |

3.11 |

1.29 |

0.35 |

0.49 |

2.15 |

| NM vs FP |

3.96 |

4.53* |

7.95** |

0.06 |

6.99* |

1.87 |

0.85 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

4.20* |

0.23 |

3.06 |

1.53 |

0.10 |

0.99 |

0.17 |

| NM vs FP |

17.34*** |

0.58 |

9.90** |

0.01 |

4.64* |

1.66 |

0.34 |

| HU - Hungarian |

F |

NM vs SU |

8.28** |

4.54* |

0.30 |

1.58 |

20.09*** |

2.40 |

23.25*** |

| NM vs FP |

9.54** |

0.01 |

6.23* |

0.85 |

18.22*** |

2.94 |

37.76*** |

| M |

NM vs SU |

3.49 |

2.51 |

0.28 |

0.01 |

7.92** |

2.84 |

14.89*** |

| NM vs FP |

7.78** |

0.82 |

1.65 |

3.31 |

18.49*** |

5.42* |

9.27** |

| KA - Georgian |

F |

NM vs SU |

0.09 |

3.76 |

15.73*** |

5.77* |

8.34** |

8.96** |

10.50** |

| NM vs FP |

0.02 |

2.47 |

14.35** |

0.11 |

0.48 |

7.86** |

3.26 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

6.64* |

0.65 |

0.12 |

0.20 |

1.09 |

0.56 |

0.06 |

| NM vs FP |

8.06** |

0.54 |

0.52 |

0.75 |

4.13* |

0.00 |

3.67 |

| LT - Lithuanian |

F |

NM vs SU |

4.65* |

0.47 |

4.38* |

6.46* |

11.53** |

0.01 |

0.24 |

| NM vs FP |

2.77 |

0.25 |

5.43* |

2.84 |

9.41** |

0.00 |

0.12 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

6.07* |

0.66 |

7.70** |

0.01 |

5.14* |

0.80 |

2.00 |

| NM vs FP |

5.44* |

5.42* |

5.96* |

3.11 |

8.34** |

1.36 |

1.75 |

| PT - Portuguese |

F |

NM vs SU |

61.00*** |

0.62 |

1.69 |

0.45 |

79.72*** |

2.78 |

10.01** |

| NM vs FP |

52.66*** |

0.11 |

0.17 |

21.3*** |

188.27*** |

1.73 |

11.65** |

| M |

NM vs SU |

103.03*** |

0.16 |

8.15** |

3.80 |

77.54*** |

0.00 |

7.79** |

| NM vs FP |

95.96*** |

5.56* |

2.55 |

22.67*** |

153.01*** |

2.08 |

11.69** |

| RO - Romanian |

F |

NM vs SU |

2.64 |

3.98 |

0.18 |

11.44** |

1.77 |

3.29 |

7.38** |

| NM vs FP |

1.06 |

11.43** |

6.71* |

32.4*** |

0.15 |

0.72 |

1.1 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

18.44*** |

0.21 |

0.01 |

7.78** |

0.04 |

0.99 |

8.71** |

| NM vs FP |

17.89*** |

0.06 |

1.46 |

7.66** |

5.42* |

0.04 |

1.28 |

| RU - Russian |

F |

NM vs SU |

2.43 |

0.03 |

4.71 |

2.20 |

0.14 |

0.84 |

0.33 |

| NM vs FP |

3.62 |

0.06 |

0.21 |

1.71 |

2.04 |

1.45 |

0.56 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

0.13 |

0.02 |

2.93 |

0.74 |

1.72 |

0.74 |

3.94 |

| NM vs FP |

0.06 |

0.19 |

1.56 |

0.85 |

1.75 |

0.08 |

1.62 |

| TR - Turkish |

F |

NM vs SU |

0.01 |

0.16 |

0.05 |

9.4** |

14.46*** |

0.01 |

9.17** |

| NM vs FP |

1.89 |

1.60 |

0.76 |

15.56*** |

21.6*** |

0.60 |

7.15* |

| M |

NM vs SU |

22.92*** |

0.71 |

3.48 |

7.20* |

23.29*** |

0.81 |

20.25*** |

| NM vs FP |

21.12*** |

1.46 |

0.92 |

1.61 |

55.17*** |

5.47* |

27.93*** |

| UA - Ukrainian |

F |

NM vs SU |

2.63 |

5.39* |

2.25 |

10.96** |

0.01 |

0.15 |

0.77 |

| NM vs FP |

0.88 |

5.73* |

6.28* |

3.42 |

4.01 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

28.4*** |

0.17 |

12.73** |

13.87** |

0.00 |

0.47 |

10.62** |

| NM vs FP |

18.16*** |

1.06 |

10.85** |

4.59* |

2.06 |

0.05 |

10.38** |

Table 4.

Results of the mixed effect models on the acoustic parameters obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications, with no mask (NM) vs. surgical mask (SU) and no mask (NM) vs. FFP2 type mask as independent variables. The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance: * p < 0,05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Results of the mixed effect models on the acoustic parameters obtained from the samples collected via mobile and landline communications, with no mask (NM) vs. surgical mask (SU) and no mask (NM) vs. FFP2 type mask as independent variables. The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance: * p < 0,05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

| Language |

Sex |

Mask type |

Linear mixed-effect models results on the acoustic parameters |

| F0

|

H1-H2

|

Intensity |

Speech rate |

HNR |

Jitter |

Shimmer |

| ES – Spanish MB |

F |

NM vs SU |

1.61 |

0.16 |

3.40 |

4.00 |

13.53* |

4.66 |

0.77 |

| NM vs FP |

1.09 |

0.10 |

9.99* |

8.04* |

9.03* |

0.61 |

8.31* |

| M |

NM vs SU |

0.20 |

9.41* |

67.07** |

1.77 |

0.06 |

4.69 |

0.01 |

| NM vs FP |

0.13 |

8.79* |

52.97** |

0.00 |

0.18 |

8.96* |

0.04 |

| PT – Portuguese MB |

F |

NM vs SU |

24.75*** |

4.17* |

2.20 |

0.23 |

7.18* |

5.19* |

21.36*** |

| NM vs FP |

14.91*** |

6.29* |

6.04** |

2.84 |

17.93*** |

3.84 |

32.94*** |

| M |

NM vs SU |

44.39*** |

0.14 |

28.62*** |

1.94 |

13.27** |

10.43** |

40.78*** |

| NM vs FP |

44.48*** |

0.00 |

12.26** |

6.70* |

23.07*** |

3.71 |

37.21*** |

| LT – Lithuanian LL |

F |

NM vs SU |

1.13 |

0.05 |

8.90** |

3.03 |

0.62 |

2.88 |

0.09 |

| NM vs FP |

0.52 |

0.13 |

7.71** |

1.29 |

3.30 |

2.09 |

0.45 |

| M |

NM vs SU |

5.96* |

1.33 |

3.48 |

0.37 |

3.07 |

1.09 |

0.43 |

| NM vs FP |

7.95** |

0.06 |

4.62* |

1.13 |

2.60 |

0.59 |

0.07 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).