Reactor effluent compositions, for different dual mixtures of one mol of total substrates at three different proportions, were simulated. Cane bagasse was used as the ‘pivot’ waste, because of its high content of water. Two more substrates, pine sawdust and wheat straw, were mixed wit the cane bagasse, in order to see the effect of a dry substrate on the possible product distribution at the gasification reactor outlet.

3.1. Sugar Cane Bagasse and Pine Sawdust

The first mixture to be analysed is sugar cane bagasse and pine sawdust, in three different proportions: {8:2, 7:3, 6:4}. These proportions were selected, because incorporation of more pine sawdust prevents the gasification reactions. The atomic account of the first mixture, proportion 8:2, is given in

Table 2.

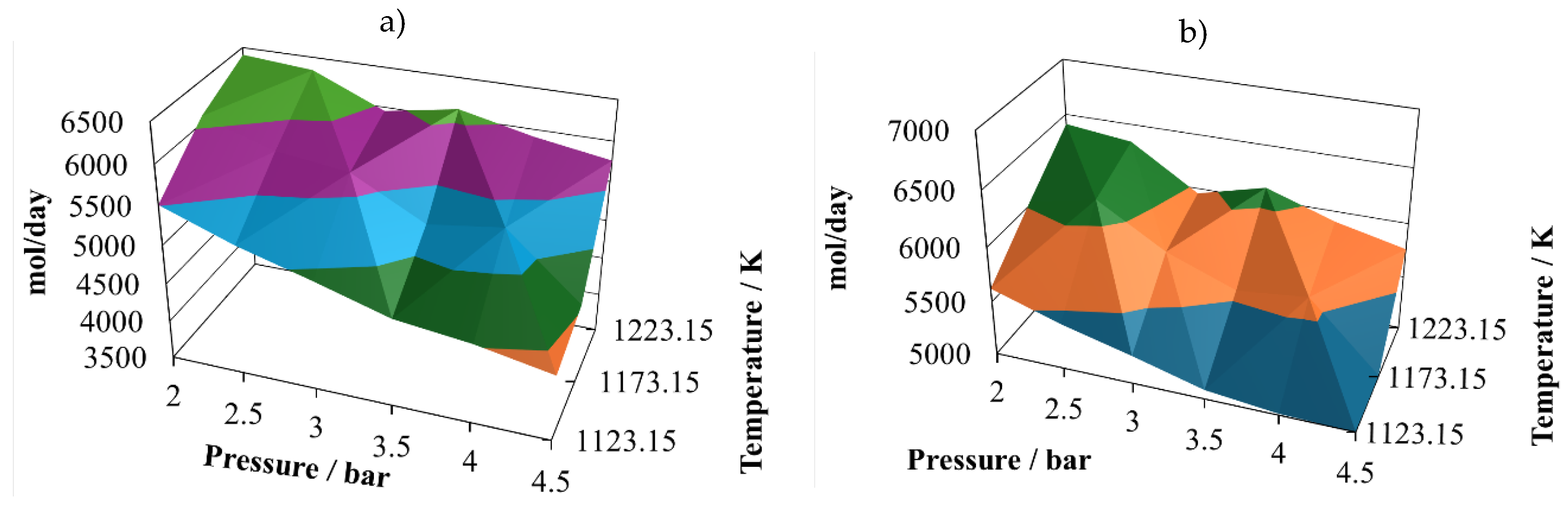

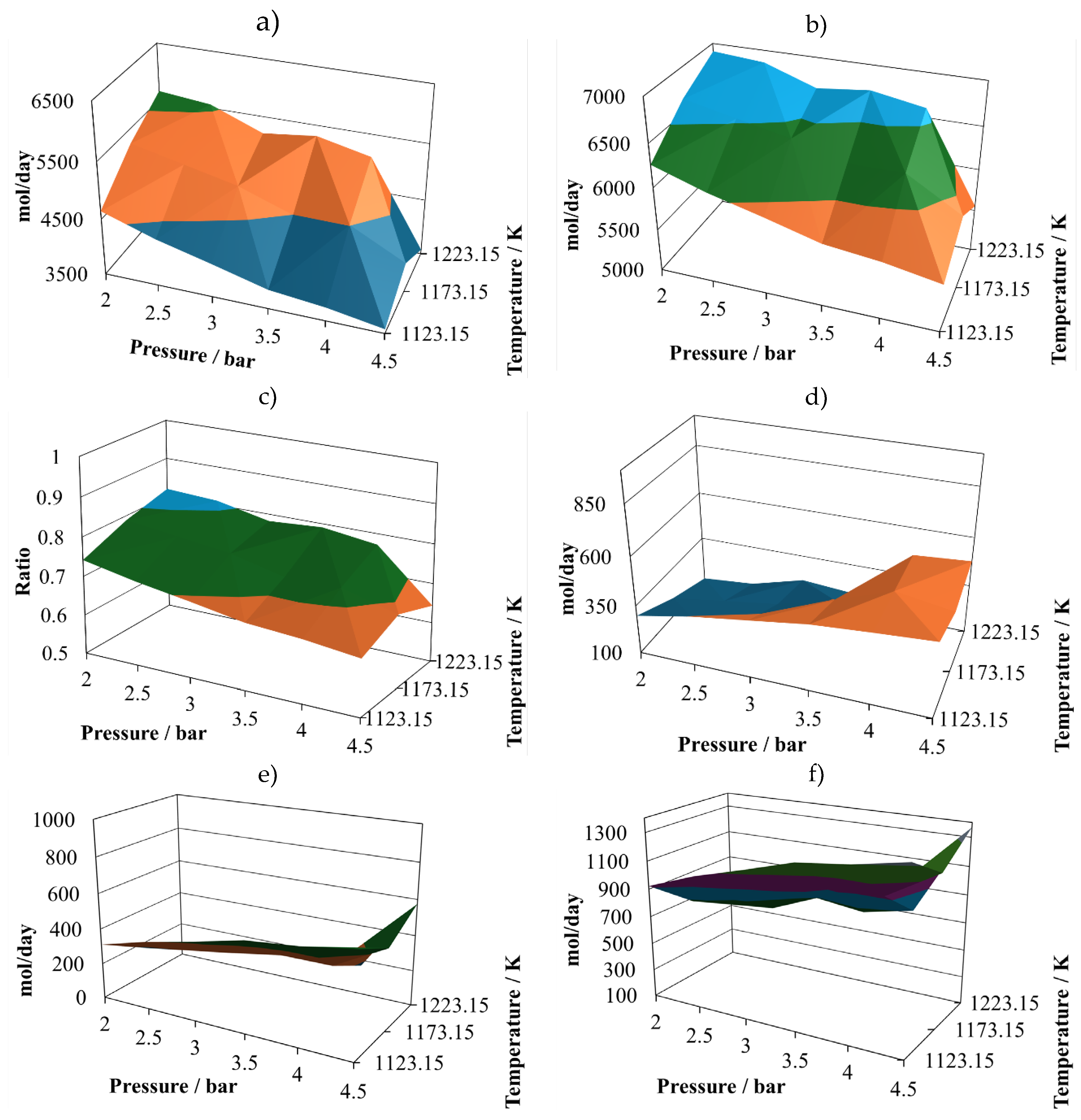

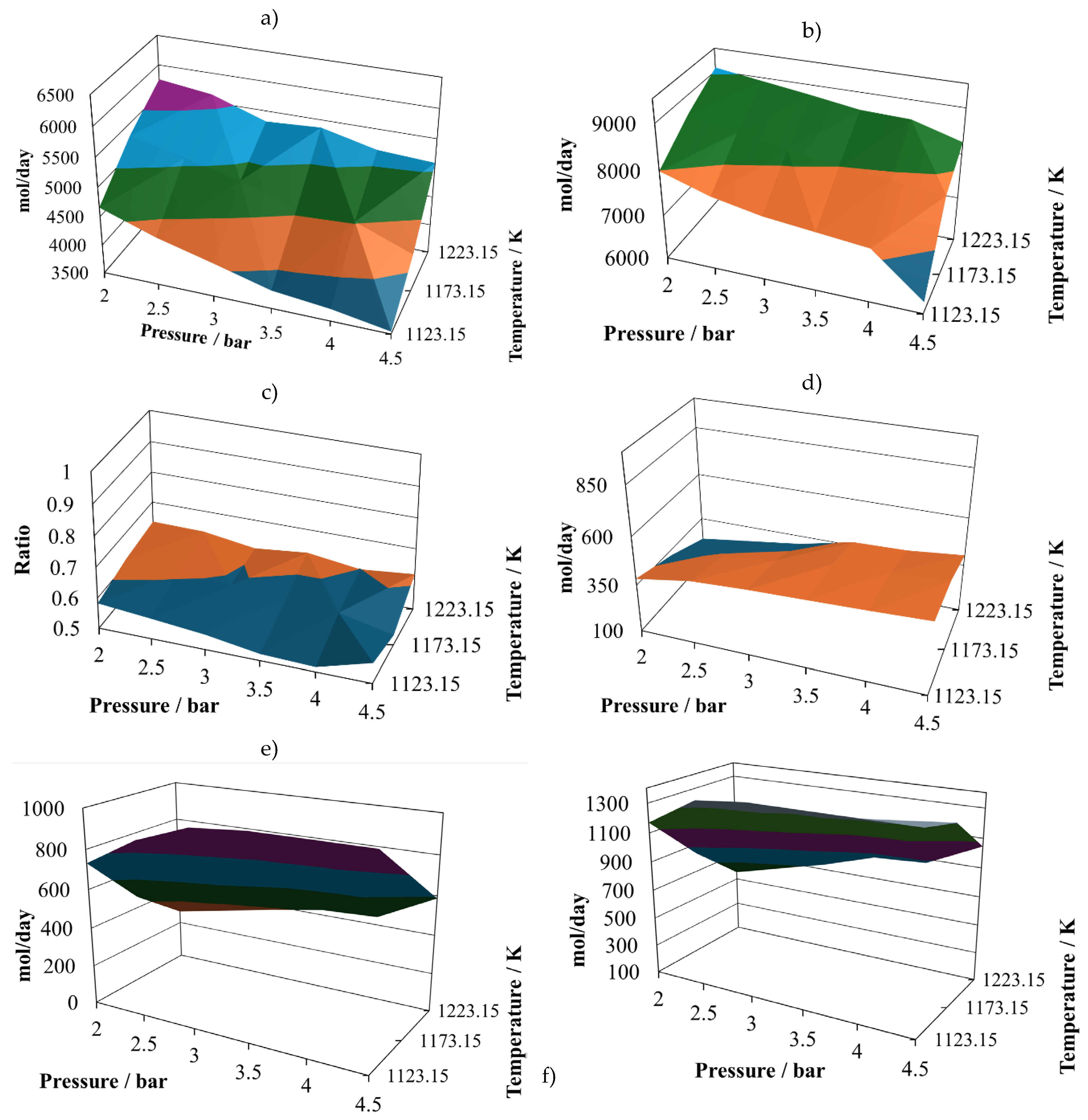

Production of molecular hydrogen at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 2a) exhibits two noticeable maxims, one at 2.5 bar and the other at 3.8 bar, both at 1223.15 K. Therefore, it is possible to infer that there are some points that should be close to the optimum yield to hydrogen. On the other hand, the minimum vales are reached at the maximum operating pressure, which means that the pressure affects inversely the hydrogen production.

Production of CO at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 2b) follows a similar trend of the one exhibit by molecular hydrogen, showing two possible relative maximum points of production, at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K) and (3.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Both gases are the principal components of the syngas, therefore it is possible to infer that syngas production is favoured at low pressures and the maximum operating temperature.

The (H

2/CO) ratio at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 2c) follows a different pattern, which is important to notice, because of the importance of this ratio in the uses that will be given to this syngas. It is possible to notice that in the simulated cases, this ratio remains mostly unchanged, oscillating between values of 0.85 to the unity. This result is in agreement with experimental observations taken previously [

6,

13].

The water available in the reactor effluent at the proportion 8:2 experiments small changes (

Figure 2d), exhibiting its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 k). Although the water profile is oscillating, it is possible to infer that its content in the reactor effluent is favoured by increasing the pressure.

The production of carbon dioxide at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 2e) exhibits oscillating behaviour with its relative maximum value at (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K), and two relative minimums at (2.0 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Therefore, its production is favoured at high pressure and intermediate temperature and prevented at high pressure and either low or high temperature.

Finally, the production of methane at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 2f) experiments medium oscillations, reaching its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K) and its relative minimum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). It also shows a hill with the relative maximum at the intermediate value.

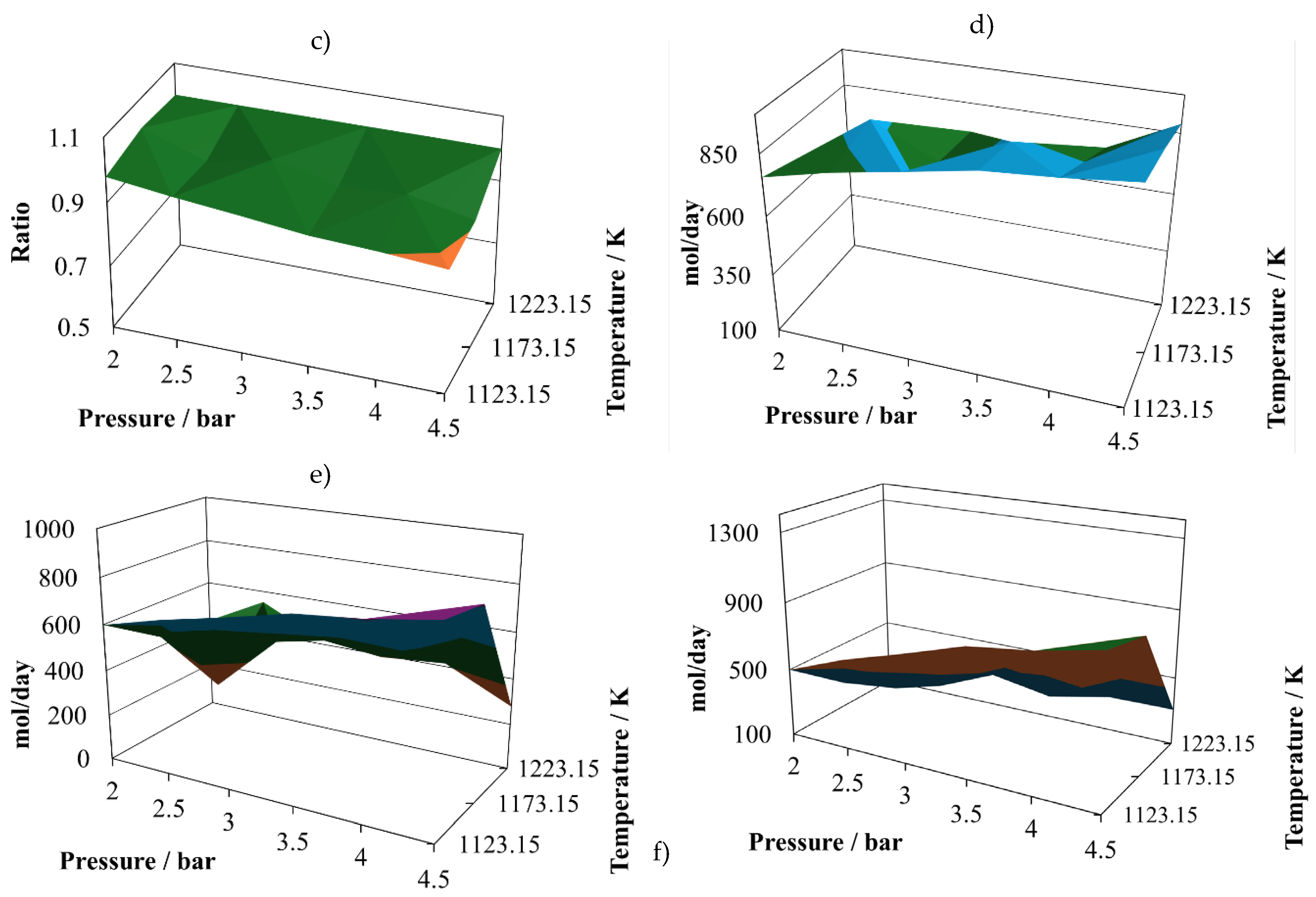

As long as the proportion is changed to 7:3, the global behaviour is very similar, with changes in some variables. The atomic account of the second mixture, proportion 7:3, is given in

Table 3.

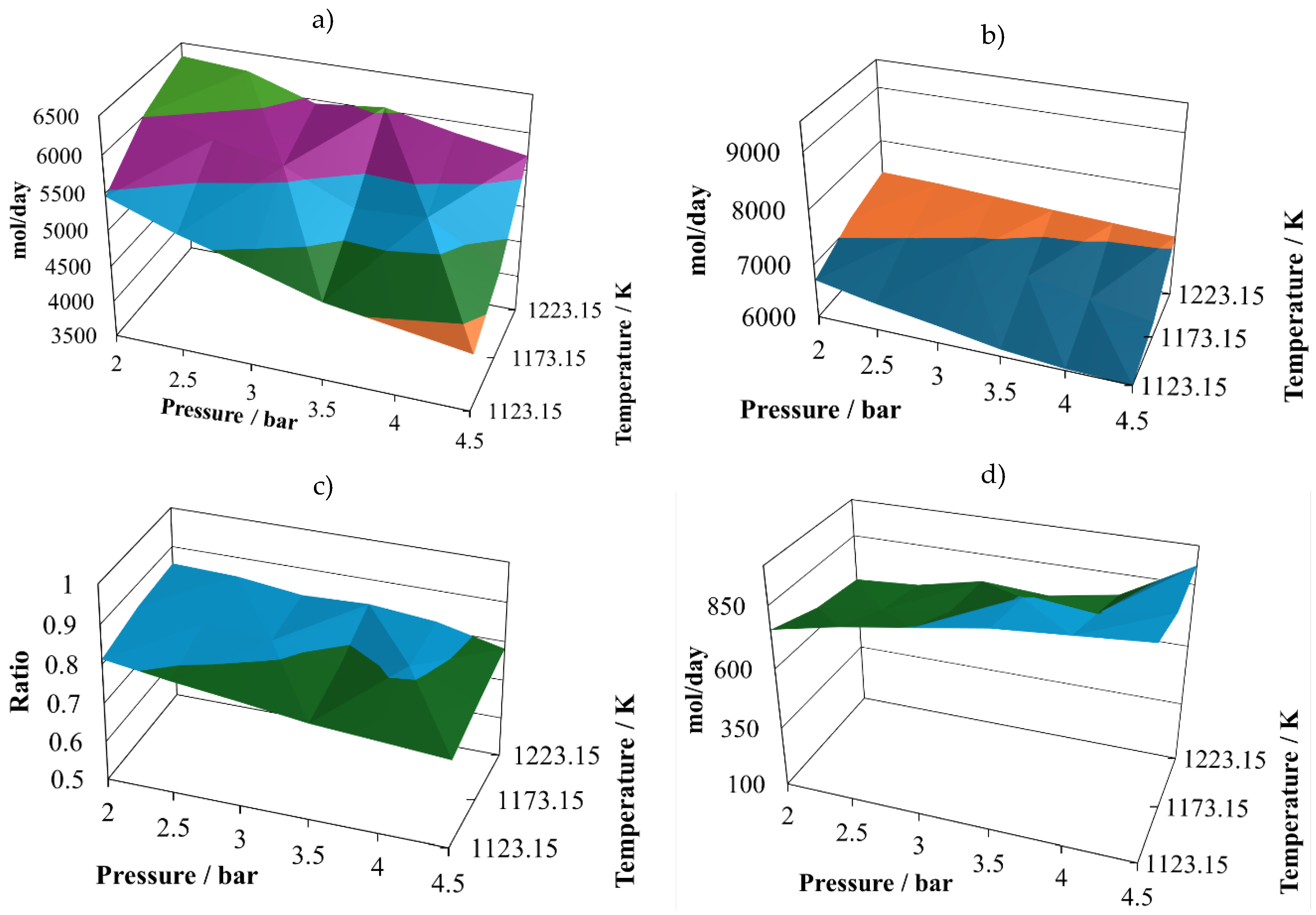

The first change is that the (H2/CO) ratio exhibits some decreasing, reaching a relative maximum close to one at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K), but a smaller minimum value than in the case of the proportion 7:3. However, the productivities of hydrogen and carbon monoxide at the proportion 8:2 are similar to those reached at the proportion 7:3. Hence, the (H2/CO) ratio is not a good quality criteria, as it is mentioned in literature.

In the case of water in the reactor effluent at the proportion 7:3 (

Figure 3d), there is a decrease in all its values, and its relative minimum is observed at intermediate temperatures. This situation changes the shape of the profiles to a hill-like ones.

The production of carbon dioxide remains in similar values for the proportion 7:3 (

Figure 3e) in comparison with those at 8:2 (

Figure 2e); however, the shape of the profile is changing, reaching its relative maximum at (2.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and its relative minimum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K).

The production of methane changes shape at the proportion 7:3 is changing, increasing its content in the reactor effluent, and reaching two relative maximum vales at (2.0 bar, 1173.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K). And in the case of the relative minimums, it is possible to observe oscillatory behaviour, reaching them at (2.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K).

The atomic account of the third mixture, proportion 6:4, is given in

Table 4.

The production of hydrogen decreases with respect to the previous proportions and exhibits oscillating behaviour. Its relative maximum is reached at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K), like the previous two cases, but now there are two relative minimums at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Therefore, the conclusion is that lower pressure favours hydrogen production. The production of CO remains similar to the other two cases and also its relative maximum and relative minimum.

Due to the changes in the shape of hydrogen production, profiles of the (H2/CO) ratio change its shape to a hill-like one, reaching its relative maximum at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K), and two relative minimums, both close to 0.65, at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Again, although the production of hydrogen and CO are similar to the previous cases, this ratio changes significatively, which seems to be a not very good quality parameter to classify the syngas.

By comparison of the mixtures with the three proportions of sugar cane bagasse and pine sawdust, it is noticed that the production of hydrogen and carbon monoxide remained similar in the three cases, however the (H2/CO) ratio changed its behaviour, noticeably. The amount of water in the reactor effluent decreased following the sequence 8:2, 7:3, 6:4; this situation is a consequence of the equilibrium conditions, and difficult to be assigned to any single influence.

3.2. Sugar Cane Bagasse and Wheat Straw

The second mixture to be analysed is sugar cane bagasse and wheat straw, in the same three proportions: {8:2, 7:3, 6:4}. The operating conditions for the gasification reactor are the same of the last case, so it is possible to compare the reactor effluent, directly. The atomic account of the fourth mixture, proportion 8:2, is given in

Table 5.

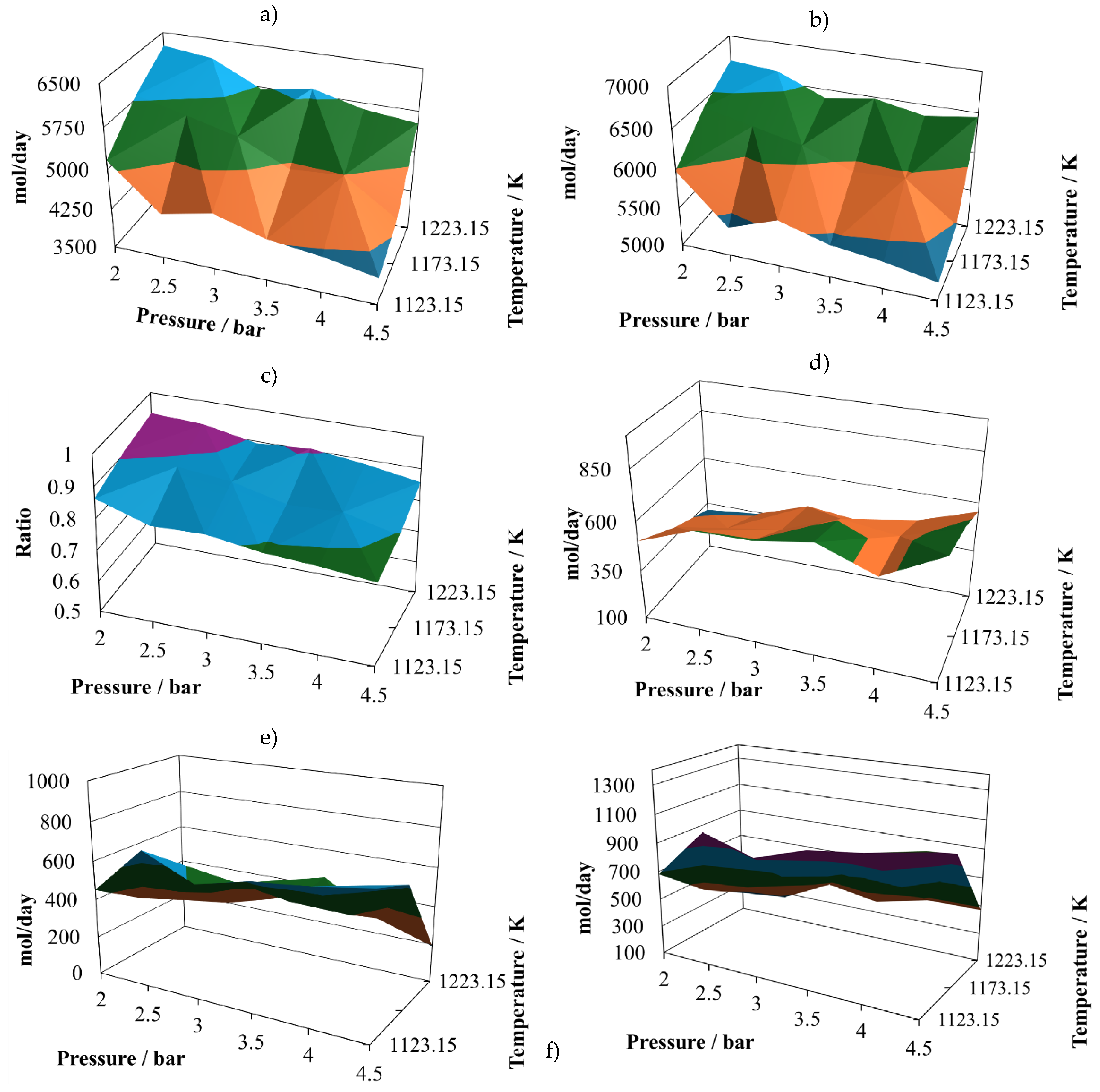

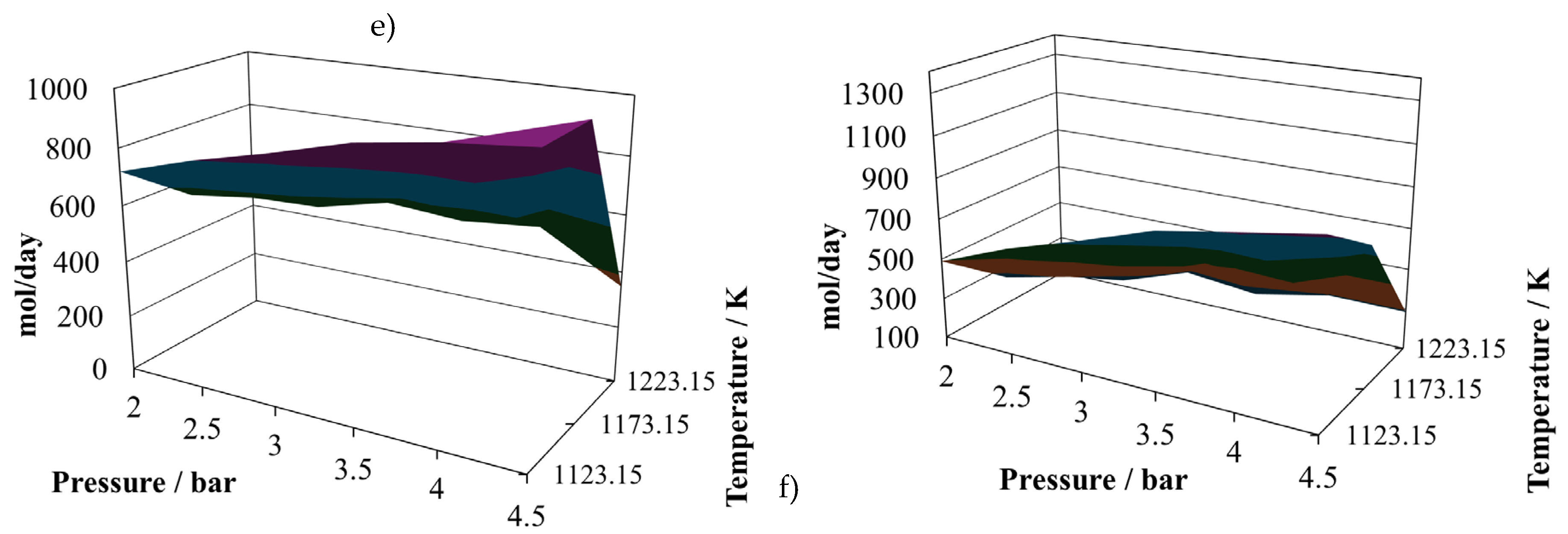

Production of molecular hydrogen at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5a), exhibits two noticeable maxims, one at 2.5 bar and the other at 3.8 bar, both at 1223.15 K. Again, it is possible to infer that there are some points that should be close to the optimum yield to hydrogen. The relative minimum vales are reached at the maximum operating pressure, which means that the pressure affects inversely the hydrogen production. The production of carbon monoxide at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5b), remains with small changes in all the operating region, reaching two relative maximums at (2.0 bar, 1123 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223 K). This production reaches its relative minimum at (4.5 bar, 1123 K). Although the stable values, these are larger than in the cases of the other mixture.

The values exhibited by the (H

2/CO) ratio are small at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5c), reaching two relative maximums of about 0.84 at (2.0 bar, 1223 K) and (4.5 bar, 1173 K). However, for this mixture, the production of hydrogen is similar to the one reached with the mixture of sugar cane bagasse and pine sawdust, but the production of carbon monoxide is higher.

The amount of water in the gasification reactor outlet, at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5d), reaches its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1223 K) and its relative minimum at (2.0 bar, 1223 K). Its shape is hill-like and oscillating, the relative changes are sensitive.

The production of carbon dioxide at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5e) exhibits oscillating behaviour with its relative maximum value at (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K), and its relative minimum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Therefore, its production is favoured at high pressure and intermediate temperature and prevented at high pressure and high temperature.

The production of methane at the proportion 8:2 (

Figure 5f) exhibits medium oscillations, reaching its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K) and its relative minimum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). Therefore, high pressures and intermediate temperatures favour the production of methane.

The fifth mixture, with proportion 7:3 exhibits a very different and oscillating behaviour, the atomic account of this mixture is given in

Table 6.

Productivities of hydrogen (

Figure 6a) and carbon monoxide (

Figure 6b) exhibit hill-like shapes, with their relative maximum showing a plateau between 2.0 bar and 2.5 bar and 1223.15 K. Both of them exhibit two relative minimums at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K). The amounts produced are the highest for both gases analysed in this work. In fact, the profiles of both production curves are very similar.

As consequence of the similarity mentioned above, the (H

2/CO) ratio (

Figure 6c) remains with very small changes in all the operating region, exhibiting values as low as 0.73 at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K) and 0.54 at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K). Again, this ratio is not an illustrative quality index to indicate the availability of hydrogen.

The water amount in the reactor effluent (

Figure 6d) exhibits its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1223.15 K) and its relative minimum at (2.0 bar, 1173 K). Its behaviour remains without great changes in the operating zone, as consequence of the equilibrium reached by the reactions.

The production of carbon dioxide (

Figure 6e) remains without great changes in the operating zone, reaching its relative maximum at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and its relative minimum at (2.0 bar, 1173.15 K).

Finally, production of methane (

Figure 6f) exhibits small changes in the operating region, reaching two relative maximums at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1223 K), reaching its relative minimum at (2.0 bar, 1173.15 K).

The atomic account of the sixth mixture, proportion 6:4, is given in

Table 7.

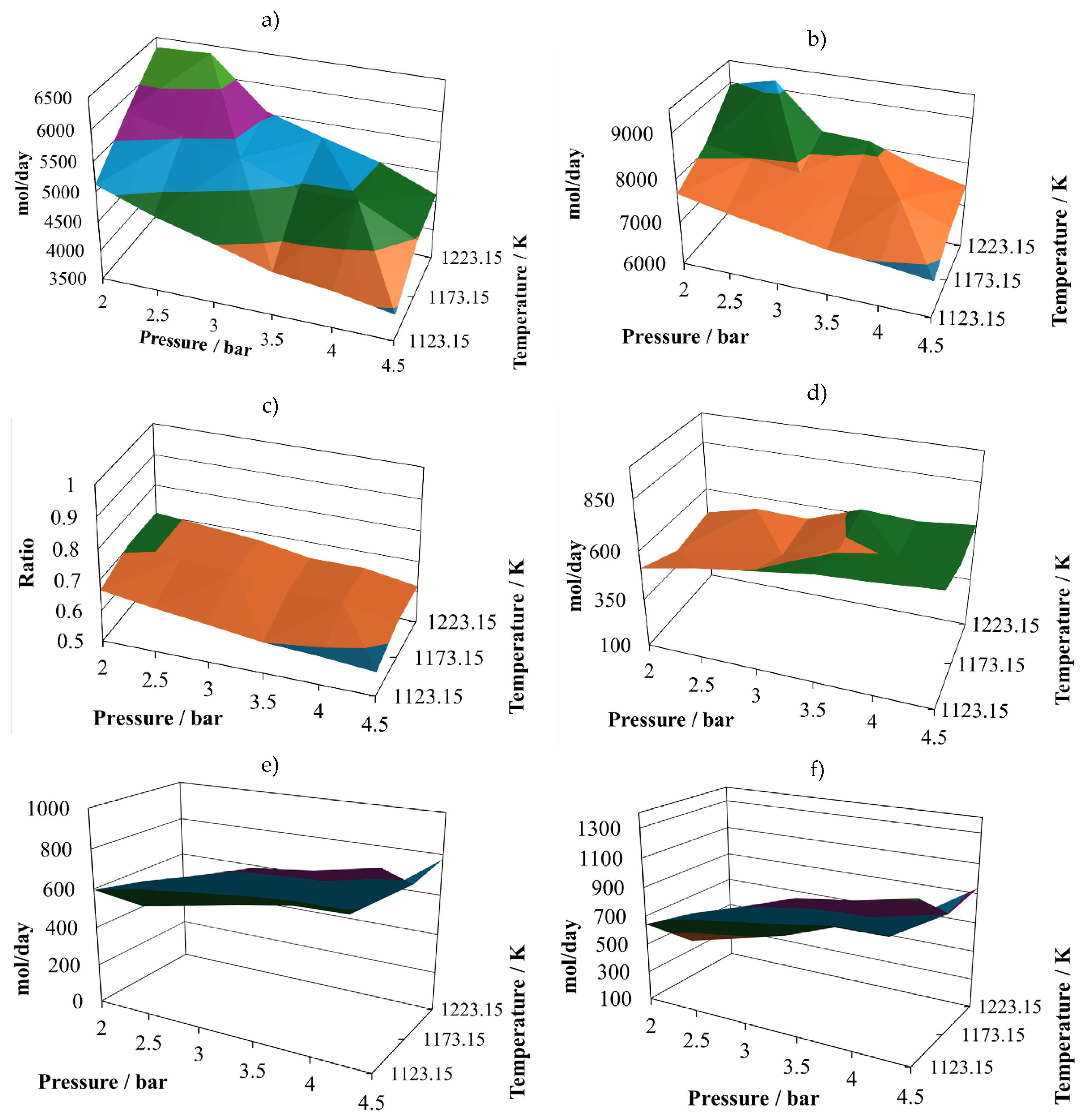

The hydrogen production for this mixture is oscillating (

Figure 7a), reaching three relative maximums at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K), (2.5 bar, 1223.15 K) and (3.5 bar, 1223.15 K). The CO production (

Figure 7b) exhibits small changes in the operating region reaching relative maximums at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K) and (4.0 bar, 1223.15 K). Also, it exhibits sensitive changes at high temperature, reaching its minimum at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K).

The (H

2/CO) ratio (

Figure 7c) exhibits very low values, reaching its maximum of 0.6 at (4.0 bar, 1173.15 K) and its minimum of 0.5 at (4.0 bar, 1173.15 K). Again, these values do not reflect the amount of hydrogen in the reactor effluent.

The water in the reactor effluent (

Figure 7d) exhibits oscillating behaviour, reaching two relative maximums at (4.5 bar, 1123.15 K) and (4.5 bar, 1173.15 K). The production of carbon dioxide (

Figure 7e) is very flat, reaching its maximum at (4.0 bar, 1226.15 K) and its minimum at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K). Finally, the production of methane (

Figure 7f) exhibits very low changes, reaching its relative maximum as a plateau between (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K) and (2.5 bar, 1223 K); its minimum is reached at (2.0 bar, 1223.15 K).

The amounts produced of gases changed according to the proportions of the sugar cane bagasse-wheat straw mixture. Production of hydrogen and carbon monoxide changed sensitively for the mixture in proportion 7:3, exhibiting their maximum values. For the other mixtures, the production of hydrogen was slower for the mixture proportion 6:4 and for the carbon monoxide the smaller production was obtained for the mixture 8:2. In the case of the (H2/CO) ratio, the observed values were decreasing from mixture to mixture, even when the production of the gases was very different, indicating again that this ratio does not reflect the syngas characteristics. The water in the reactor effluent decreased from simulation to simulation, as consequence of the equilibrium reached by the reactions. Production of carbon dioxide exhibits its maximum for the mixture with proportion 8:2, the minimum for the one with proportion 7:3 and an intermediate value for the mixture of proportion 6:4; again, as consequence of the equilibrium. Production of methane increased slowly from the first to the second mixture but increased notoriously for the third mixture.

Comparing the production profiles between the mixtures of pine sawdust with sugar cane bagasse and the wheat straw with sugan cane bagasse, all the values were higher for the mixtures with wheat straw. It was expected, because the higher amount of carbon and hydrogen atoms supplied by each mixture; however, it is not easy to predict the final distribution of these atoms in the products of the gasification reactions. Therefore, this methodology that uses empiric stoichiometry to follow the mass balances in the gasification reactor, constrained by the equilibrium conditions for the chemical reactions, helps in the prediction of production profiles during the gasification of mixtures of lignocellulosic waste, which are closed to experimental results.